Abstract

The Russo–Ukrainian conflict (RUC) escalated on 24 February 2022 with Russia’s large-scale military operation in Ukraine. Our review aims to present the impact of the RUC on Ukrainian water resources and infrastructure. Its primary objective was to analyze 61 relevant papers, selected and screened according to the PRISMA methodology, concerning changes in inland and marine water quality, employing diverse scientific and analytical methods, and technical tools. Key recurring themes included “Ukraine”, “Russian-Ukrainian War”, and “Ecocide”. Beyond assessing the environmental consequences of destroyed treatment plants, supply systems, and sewerage units, as the secondary objective, the review introduces the concept of “aquacide”—the deliberate or incidental destruction and contamination of water infrastructures and resources during military operations. The most severe cases were documented in southern and eastern Ukraine, with the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam standing out as the most widely reported “aquacide”. Finally, the review highlights the critical role of satellite imagery and remote sensing as the most effective tools in monitoring water quality and infrastructures under wartime conditions, when in situ observations and measurements are often impossible.

Keywords:

Ukraine; Russia; war; conflict; water quality and pollution; water infrastructure; ecocide; aquacide 1. Introduction and Background

Environmental pollution has intensified in recent decades, driven by urbanization, industrial activity, population growth, and unsustainable agriculture, with serious impacts on ecosystems and public health [1,2,3,4]. Among its forms, water pollution is particularly critical, affecting aquatic systems, human health, and economic activities [5,6,7,8]. Waterborne pollutants can generally be classified and assessed into three broad categories: chemical (both organic and inorganic), physical, and biological agents [9,10].

Environmental degradation linked to military conflicts is not new; it dates back to antiquity, with impacts on biodiversity, soil erosion, and pollution of water and soil continuing into the present. A lesser-known dimension is water contamination, as damage to hydrotechnical infrastructure has compromised both quality and availability [11,12,13]. Recent examples include the Yemen Civil War, which caused famine and a humanitarian crisis; the Iraq Wars that degraded water quality; the Gulf War in Kuwait, which generated marine oil spills and aquifer damage; the Syrian Civil War that harmed agriculture through irrational irrigation; and the Gaza conflict, which destroyed wastewater treatment plants [11,14,15,16,17]. Heavy weaponry, chemical arms, and modern military technologies have further degraded ecosystems [18,19]. Hydrological infrastructure has often been damaged, disrupting water supply systems and displacing populations [20,21,22]. The destruction of dams, sewage networks, storage tanks, and treatment plants has reduced access to clean water and undermined sustainable development prospects [23,24,25]. In the Balkans, landmines from past wars continue to affect biodiversity, ecosystem functions, wildlife migration, and habitat rehabilitation [26].

These effects fall under the broader concept of ecocide, defined as actions undertaken with conscious awareness of causing severe, widespread, or long-term environmental harm [26,27,28,29,30]. Although increasingly recognized in environmental debates, including within some countries and the European Union, ecocide is not yet universally acknowledged as a legal instrument. The term dates back to 1970, during the Vietnam War, when it described deliberate ecological destruction intended to devastate entire ecosystems, with lethal consequences for human and biodiversity [31,32,33]. More recently, the Russo–Ukrainian conflict (RUC) has brought the term into prominence across media channels, despite the absence of an international legal framework [34,35,36]. In this context, we propose the concept of “aquacide” as an analytical tool to denote acts during armed conflict that destroy or contaminate water infrastructures and resources, whether directly or as collateral damage. This distinction highlights water as a critical element of environmental security.

The armed conflict in Ukraine escalated on 24 February 2022 with Russia’s large-scale military operation, following the 2014 annexation of Crimea [37,38,39,40]. Ukraine holds a pivotal geopolitical position as a transitional zone between East and West and a strategic area for Western alliances [41,42,43]. Beyond its agricultural sector, the country’s mineral reserves (coal, iron ore, natural gas, etc.) are vital for industrial and economic development [44,45], yet much of this production has been disrupted by the war, with the food sector most severely affected [46,47,48,49,50].

Ukraine also possesses extensive water resources, including over 63,000 rivers and 1137 reservoirs, essential for navigation, agriculture, and public supply [51,52]. However, the country ranks 32nd out of 40 in Europe for potable water access. Vulnerability stems from reliance on surface waters—about 75% of supply comes from rivers—and dependence on external sources from neighboring territories [53,54]. Many of these resources are already polluted, a condition further worsened by the ongoing conflict [55,56,57,58].

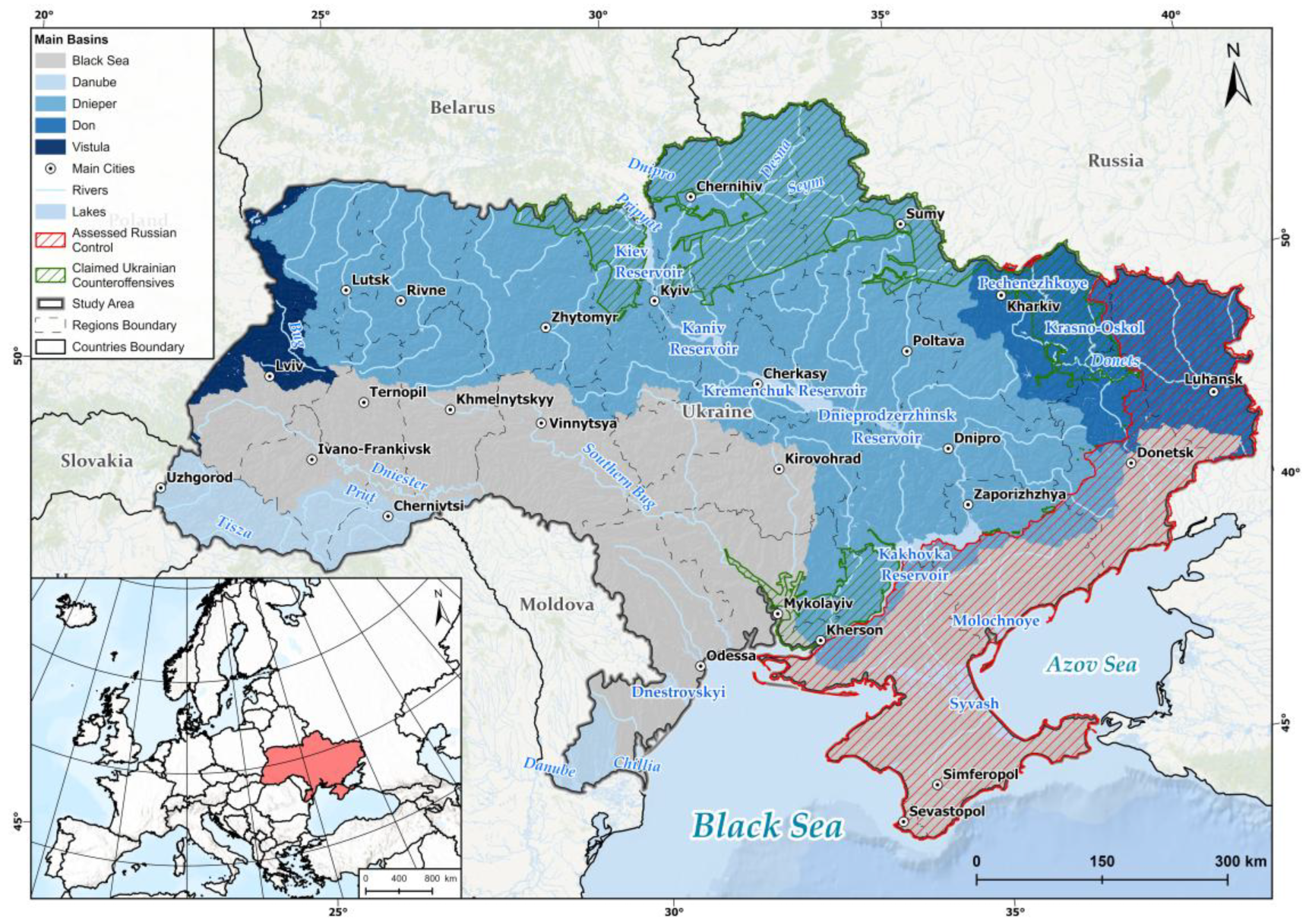

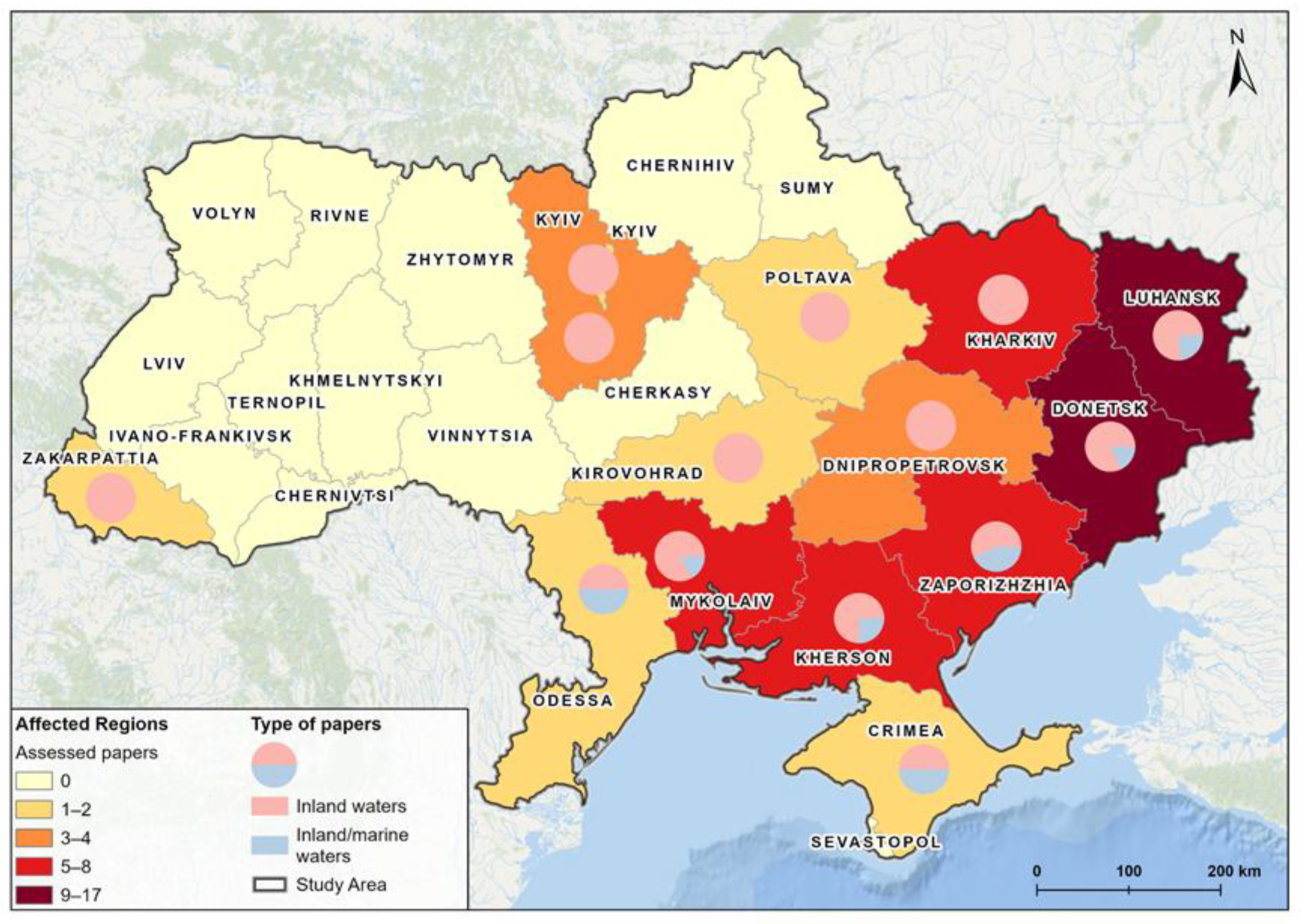

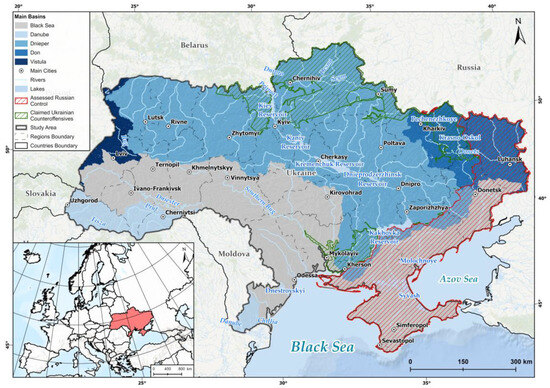

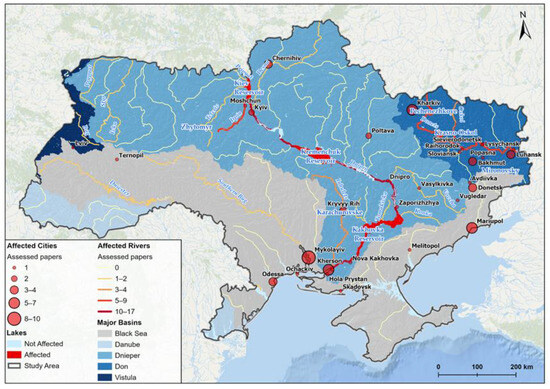

As of July 2025, approximately 19% of Ukraine’s territory (≈114,000 km2), including Crimea and parts of Donetsk, Kharkiv, Kherson, Luhansk, Mykolaiv, and Zaporizhzhia, were under Russian control, mainly in the east and south (Figure 1). The most affected basins are the Dnieper/Dnipro—Ukraine’s largest watershed [59]—and the Don in the east. Smaller rivers draining into the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, such as the Southern Bug, have also been impacted, especially near Kherson and Mykolaiv [60,61]. Armed conflict has further damaged marine environments through the disposal of chemical and biological weapons [62,63]. In both the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, the RUC has triggered severe disruptions, including chemical contamination, oil spills, coastal habitat degradation, and biodiversity loss [64].

Figure 1.

The regional setting of the Russo–Ukrainian conflict (RUC), July 2025. Data sources: Natural Earth “https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/ (accessed on 30 September 2025)” and Institute for the Study of War-ISW, hosted on ArcGIS StoryMaps, “https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/36a7f6a6f5a9448496de641cf64bd375 (accessed on 30 September 2025)”.

Given this context, our study aims to examine the impact of the RUC on water resources quality and pollution. The primary objective is to analyze a curated database of relevant scientific publications addressing contamination and quality changes in both inland (freshwater) and marine environments. Secondary goals include assessing the environmental consequences of damaged water infrastructure and introducing the concept of “aquacide” into academic discourse. A third objective is to identify the tools used to evaluate these impacts, including geomatics techniques, field observation, and water monitoring, sampling and analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

To conduct this study, we examined research on the impact of the RUC on water quality and pollution. Literature was retrieved from Web of Science, Nature Journals, ScienceDirect Freedom Collection, Scopus and Elsevier, and Google Scholar, covering publications up to December 2024 (without a start temporal option). Keywords included water pollution, water quality, war, Ukraine, and Russia, without Boolean operators to avoid narrowing or broadening the search. The final search was dated 25 July 2025, with the most significant surveys published in 2022–2024.

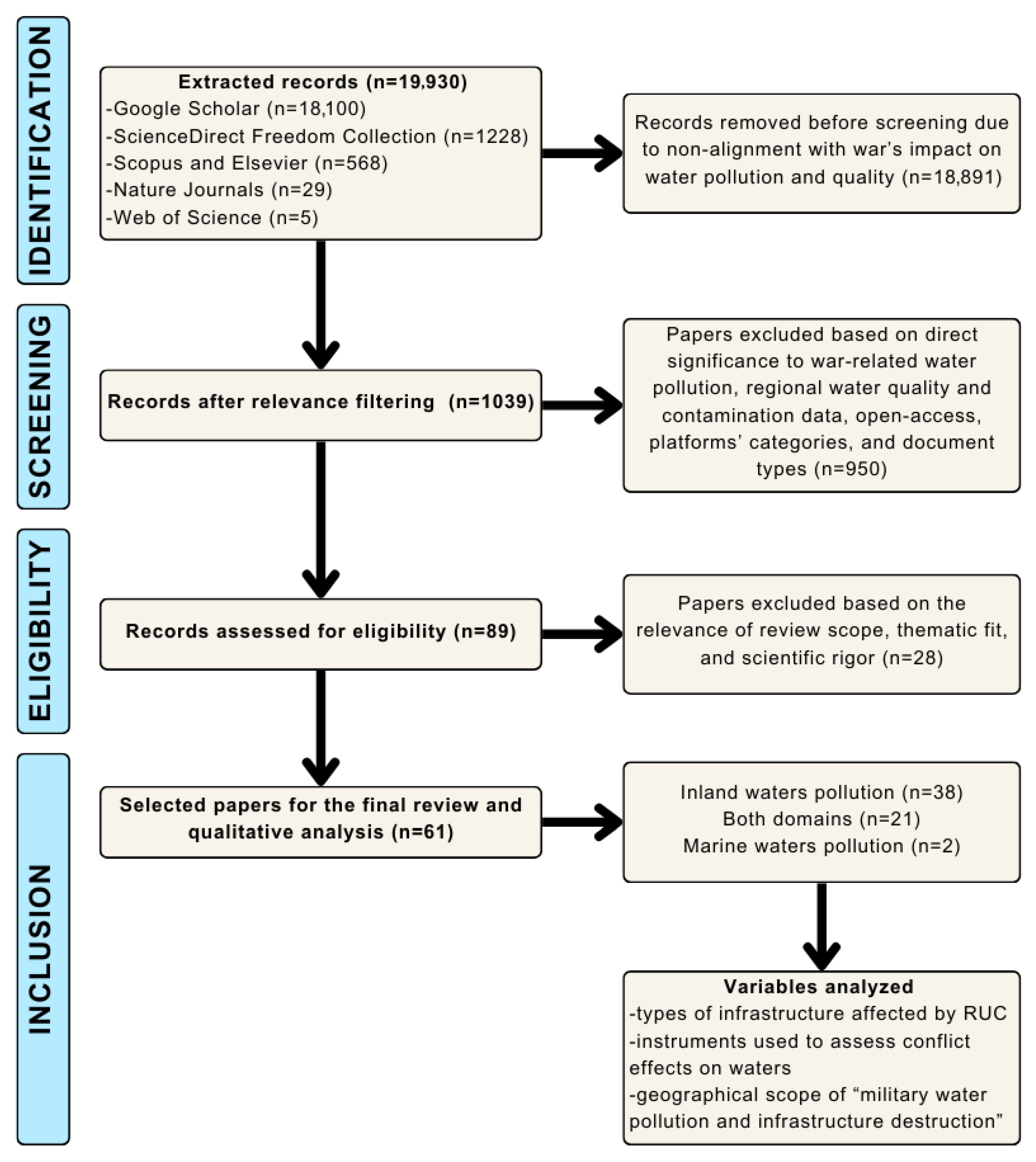

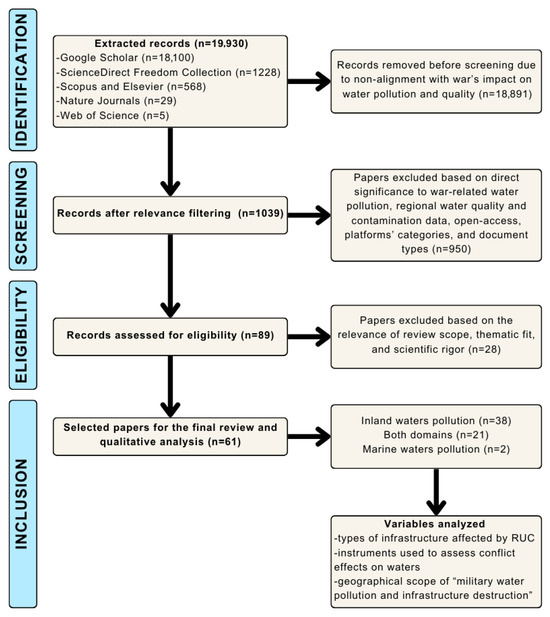

The initial search yielded 19,930 results (Google Scholar—18,100; ScienceDirect Freedom Collection—1228; Scopus and Elsevier—568; Nature Journals—29; Web of Science—5). These were reduced to 1039 publications based on relevance to war-related water pollution and quality. A second screening, applying filters for regional data, open access, categories, and document types, narrowed the selection to 89 works containing data on regional water quality and contamination. A final protocol-based review (relevance, thematic fit, and scientific rigor) resulted in 61 studies: 38 on inland water pollution, two on marine water pollution, and 21 covering both domains. The main variables analyzed were the types of infrastructure affected, the instruments used to assess impacts (geomatics, field observation, monitoring, sampling, analysis), and the geographical scope of what we termed “the military water pollution and infrastructure destruction”. The workflow (PRISMA methodology) is shown in Figure 2, and classification by water domain in Table 1. Although interconnected through river systems, inland and marine waters differ markedly in their characteristics, pollution sources, ecological dynamics, and management needs. Inland waters are primarily freshwater systems affected by agricultural runoff, sewage, and industrial discharges, with direct consequences for drinking water, irrigation, and local biodiversity. Marine waters, by contrast, are saltwater systems shaped by currents and tides, receiving both land-based inputs and direct sources such as shipping, offshore activities, and atmospheric deposition, with impacts on fisheries, climate regulation, and transboundary ecosystems. Importantly, under wartime conditions these pollution sources, pathways, and ecological characteristics are altered, intensifying pressures on both inland and marine environments and necessitating distinct yet interconnected management approaches.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the analysis (PRISMA methodology).

Table 1.

The final bank of reviewed studies classified according to the analyzed water categories.

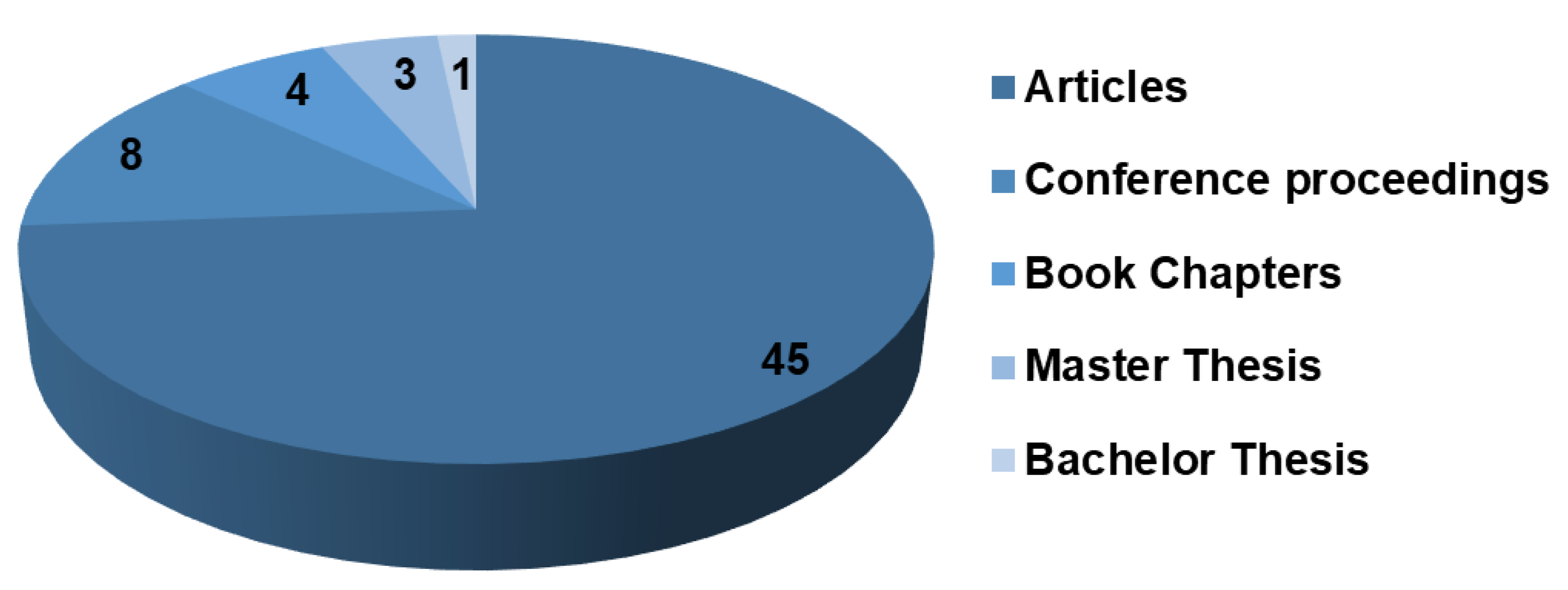

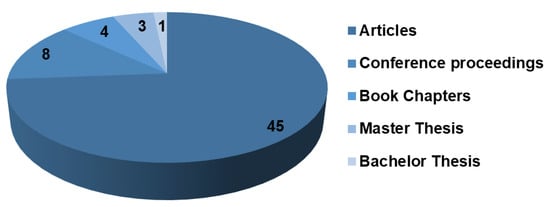

As shown in Figure 3, most sources were peer-reviewed journal articles (45), followed by conference proceedings (8). The selection also included four master’s thesis, three book chapters, and one bachelor’s thesis, all providing relevant data. These works were analyzed after assessing their scientific rigor and quality, including methodology, transparency and replicability, coherence, logic, accurate reporting, sound argumentation, and rationale conclusions.

Figure 3.

Types of selected scientific papers.

To analyze the 61 works, we applied several methods to ensure objective and rigorous research: (i) general scientific methods: literature review (analysis and synthesis of academic works), descriptive and systematic approaches, and identification of cause-and-effect relationships; (ii) specific scientific methods: cartographic techniques (maps, satellite imagery, original cartographic materials) and bibliometric analysis (keywords, publication types, and author affiliations); (iii) empirical and theoretical generalization, supported by technical tools for data processing and structuring, such as word clouds, maps, and GIS, to integrate extracted information into the study’s analytical framework.

Special emphasis was placed on maps created with ArcGIS Pro, used in the following chapter to identify the number of papers per Ukrainian region affected by the war, along with the cities and contaminated water bodies mentioned in the selected studies.

3. Results and Discussions

Following Russia’s full-scale military operation in Ukraine on 24 February 2022, scientists have expressed growing concern over its environmental consequences.

This review examines the conflict’s impacts on water quality, pollution, and infrastructure in Ukraine. In some cases, effects have been catastrophic, directly damaging aquatic habitats and the biosphere, prompting us to propose the conceptual term “aquacide”, by analogy with “ecocide”.

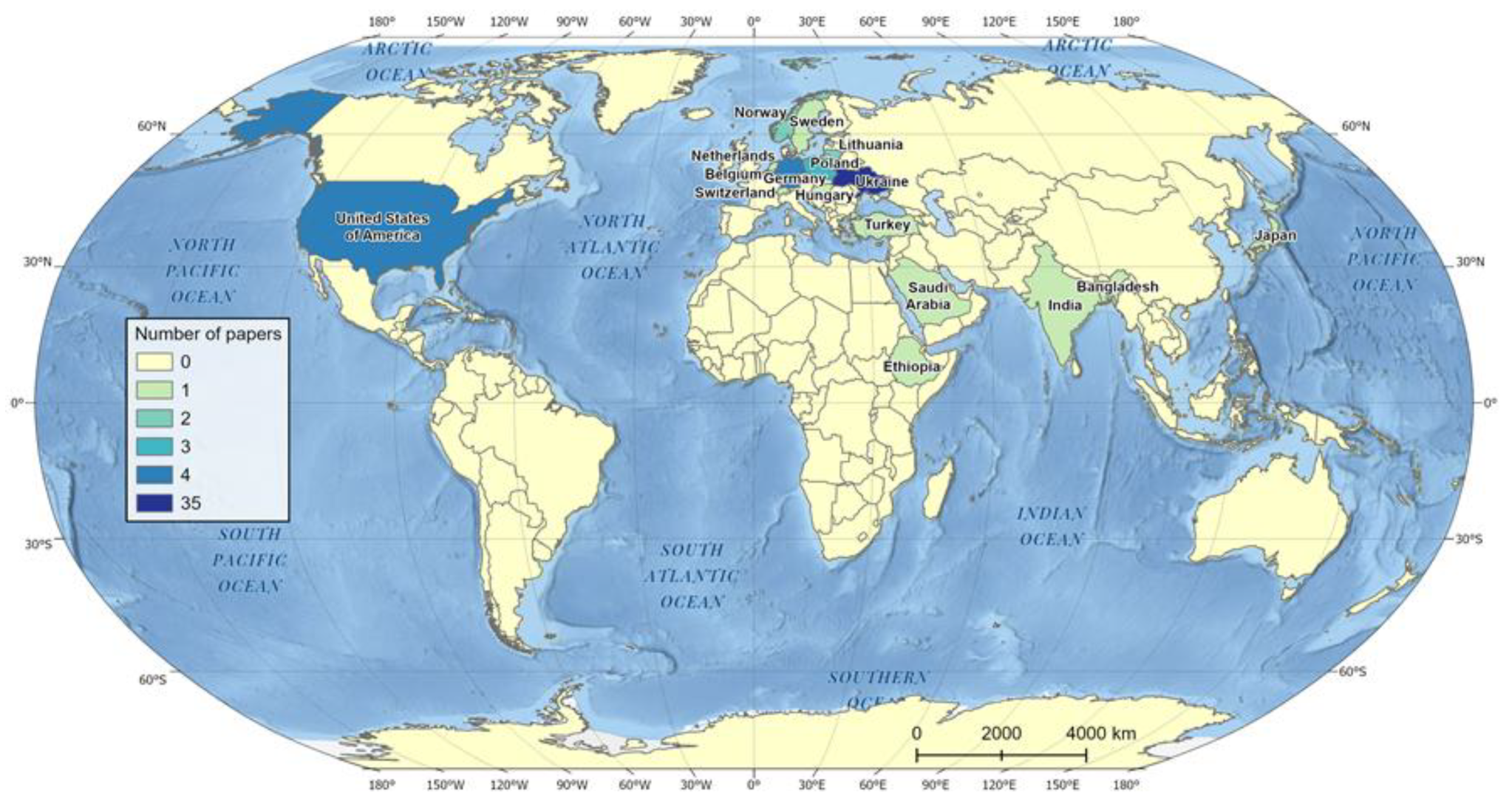

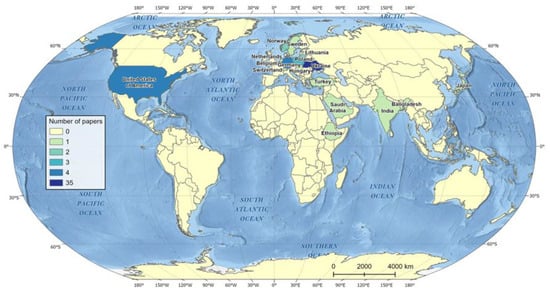

Figure 4 shows the geographical distribution of first authors’ affiliations of 61 works. Most (35) are based in Ukraine, reflecting strong local concern over the RUC’s environmental effects. Other contributions came from the United States and Germany (four each), Poland (three), Lithuania and Norway (two each), and single papers from Turkey, India, Bangladesh, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Belgium, Hungary, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Ethiopia. This spread underscores the issue’s international relevance, demonstrating that the environmental degradation and pollution caused by the RUC have drawn global scholarly attention.

Figure 4.

Geographical distribution of the first authors’ countries.

To explore recurring themes, a Word Cloud (Figure 5) was generated via https://www.wordclouds.com/, based on keywords from 59 of the 61 reviewed papers (291 terms total). The most frequent were Ukraine (10 mentions) and Russian Ukrainian War (10), reflecting the study’s context. War and Ecocide appeared six times each, while Environment was cited five times. Terms such as Black Sea, Kakhovka dam, Ecosystem services, Damages, Water resources and Pollution occurred four times. Environmental impacts, Ecology, Water supply, Military operations and Water infrastructures were each referenced three times. Other terms, including Russia, Reservoirs, Water pollution, Rivers and Water security, appeared twice.

Figure 5.

Word Cloud of the main keywords in the selected papers.

3.1. Analyses of Inland Waters Affected by RUC

Although 38 relevant articles address continental waters in Ukraine (Table 2), this remains a relatively limited body of literature. The scarcity reflects the difficulty of identifying war-related impacts on aquatic pollution and quality during active conflict. In situ monitoring is extremely challenging, and many consequences are inferred from scientific practice and experience or assessed using alternative tools.

Table 2.

Keywords and key findings in the 38 articles analyzing the impact of the Russo–Ukrainian conflict (RUC) on inland waters.

To highlight the catastrophic destruction and contamination of freshwater resources and infrastructure—phenomena we term “aquacides”—authors employed a range of scientific tools. To provide a concise overview of the objectives addressed by the 38 studies, as well as our own analysis, we compiled a summary of crucial keywords and findings (Table 2).

Our review shows that 30 articles examined damage to water supply infrastructure, seven focused on sewerage systems, three on water treatment and wastewater facilities, nine on industrial infrastructure, five on flooded coal mines without pumping systems, and one on irrigation infrastructures, all posing pollution risks to various water bodies. Accessing conflict zones to collect direct data remains extremely difficult, so information is often gathered indirectly.

The destruction of water infrastructure has severe consequences, disabling water supply to the population and forcing displacement or appeals for assistance. The regions most affected include southern oblasts—Donetsk and Luhansk (Donbas), Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa—as well as eastern Kharkiv and central-southern or southeastern oblasts such as Dnipropetrovsk and Poltava. The most severely impacted rivers—both qualitatively and quantitatively, as well as morphologically—are the Dnieper (entire basin) and Siverskyi Donets.

Eleven studies investigated ecocides committed by the RUC in Ukraine, referred to as aquacides when water bodies are the primary targets. Twelve focused on the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam (Kherson oblast), one of the most publicized and scientifically examined catastrophes. Fatal consequences included the collapse of aquatic biocoenoses in inland waters, particularly benthic fauna, mollusks and fish.

Scientific tools used to assess impacts were limited. Standard water quality monitoring—sampling and laboratory analysis—was possible only in specific cases: drinking water bodies, centralized water supply systems in bombed cities (primarily in southern and eastern Ukraine), decentralized sources used by local populations in the same regions, and targeted studies of aquacides such as Kakhovka (Kherson oblast). These analyses were documented in 11 scientific studies.

We argue that satellite imagery represents the most effective tool for evidencing the RUC’s impact on Ukrainian water bodies, including aquacides. It has proven vital for ecological situational awareness, notably in documenting events such as the Kakhovka Dam destruction. Satellite sensors provide data on water quality parameters (e.g., turbidity, chlorophyll concentration, and temperature), enabling pollutant detection and rapid response. Remote sensing also facilitates the tracking of oil spills, chemical discharges, and sediment transport, thereby supporting ongoing monitoring of pollution sources. At the same time, broader limitations must be acknowledged: vulnerability to jamming, coverage gaps in rural areas or under dense cloud cover (in the absence of SAR), and operational security risks associated with public sharing. These constraints underscore the importance of integrated, multi-source approaches to water monitoring.

GIS complements these tools by creating detailed maps of contaminated areas and supporting remediation efforts. Combined with satellite data, GIS allows analysis of temporal changes in water quality and resource distribution, informing decisions for water management.

Integrating remote sensing, GIS, and in situ monitoring facilitates accurate identification of contaminated zones and pollution sources, contributing to efficient remediation strategies in Ukraine. These technologies are essential for monitoring and managing water quality under war conditions, mitigating environmental impacts, and safeguarding public health.

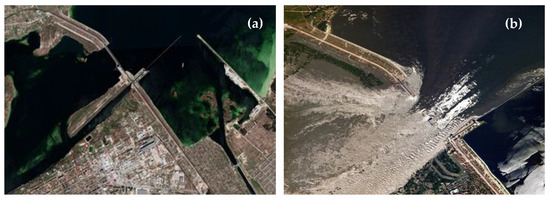

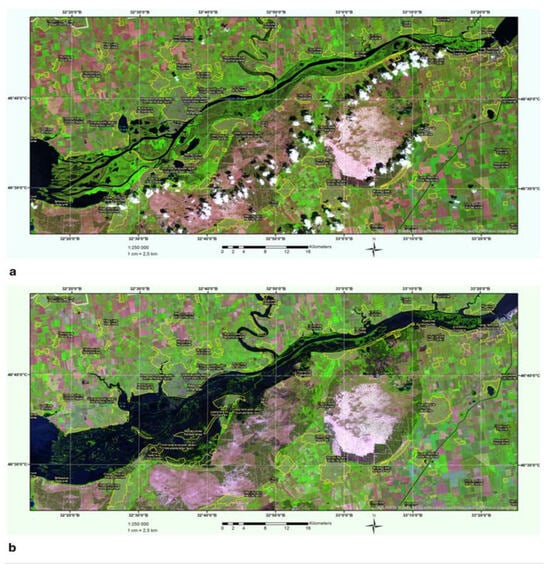

In our review, 16 studies directly used satellite imagery to document water bodies, while three emphasized remote sensing, for a total of 19 articles. Most images highlighted the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam (Kherson oblast; Figure 6 and Figure 7), Irpin Dam (Kyiv oblast; Figure 8), and Oskil Dam (Kharkiv oblast).

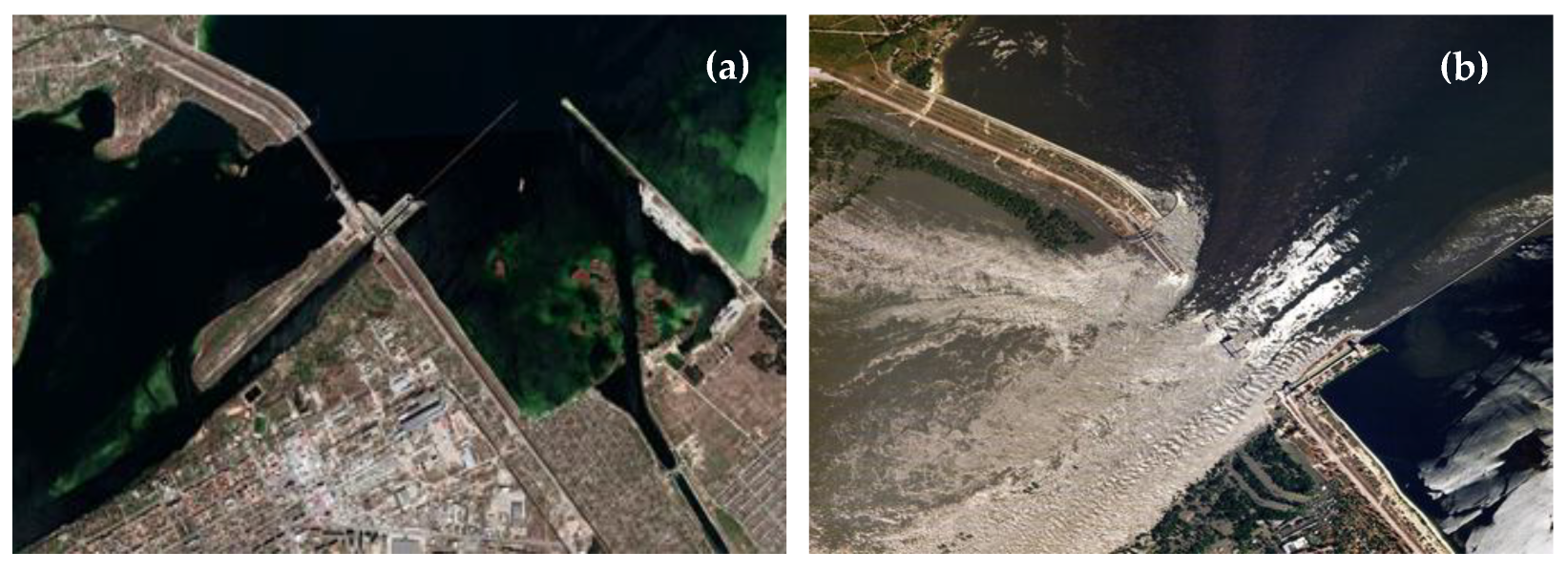

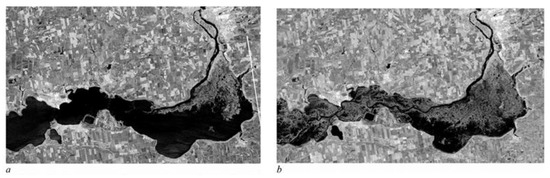

Figure 6.

Satellite image of the Kakhovka Dam: (a) prior to its destruction (20 October 2020); (b) hours after its destruction (6 June 2023). Source of satellite image: Gleick et al., 2023 [73].

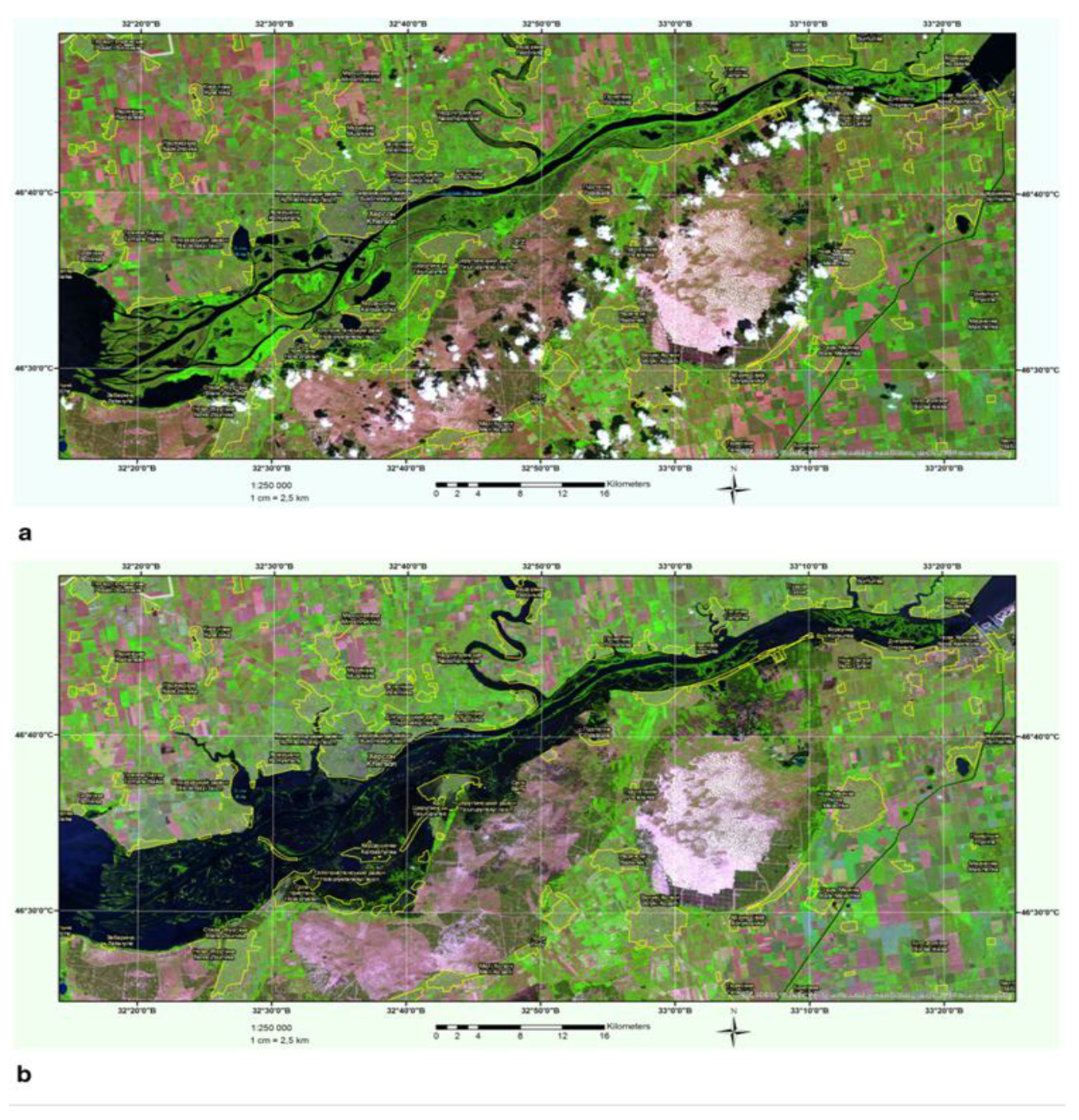

Figure 7.

The floodplain of the lower Dnieper River: (a) before the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, on 3 June 2023 (Sentinel-2 satellite image, spatial resolution of 10 m); (b) after the destruction of the dam, on 9 June 2023 (Landsat 9 satellite image, spatial resolution of 30 m). Images reproduced from Gleick et al., 2023 [73].

Figure 8.

Flooding in the floodplain of the Irpin River on 11 March 2022 (left image) and 18 March 2022 (right image). Source of Sentinel-2 satellite images (spatial resolution of 10 m): Gleick et al., 2023 [73].

For this discussion, we selected satellite images from Gleick et al. (2023) [73], among the clearest and most illustrative examples in the reviewed literature. We consider satellite imagery indispensable for detecting and monitoring aquacides, assessing impacts, and guiding future restoration efforts.

3.2. Analyses of Inland and Marine Waters Affected by the RUC

In total, 21 scientific studies examined the consequences of the RUC on both continental and marine waters. We reviewed these contributions separately, to present their findings and discuss them accordingly. To provide clarity, a summary of essential keywords and findings was compiled (Table 3).

Table 3.

Keywords and key findings in the 21 articles analyzing the impact of the RUC on inland and marine waters.

Of the 21 articles, 20 analyzed damage to water infrastructure (supply, treatment, and wastewater), 12 investigated damage to industrial infrastructure, two explored the effects of military objects deposited in continental or marine waters, and one examined flooded coal mines with contamination risks. Collecting accurate information on damaged infrastructure during active conflict remains extremely difficult. These studies indicate that the highest concentration of damage occurred in southern oblasts of Ukraine—Donetsk and Luhansk (Donbas), Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa—as well as eastern Kharkiv, reflecting the intensity of combat in these regions.

The most severely affected water bodies were the Dnieper River (including its basin and the Dnieper-Bug estuary), the Siverskyi Donets River, and the coastal zones of the Black Sea and Sea of Azov.

11 studies investigated water-related ecocide (aquacide), particularly the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam (Kherson region), a widely publicized disaster extensively analyzed by scientists. All 21 articles also addressed marine coastal zones, noting severe repercussions for dolphins, migratory birds and microorganisms.

Regarding dolphin mortality, there is clear evidence of a sharp increase linked to naval noise, mines, pollution, and explosions. However, precise numbers remain difficult to establish due to restricted access to Ukrainian Black Sea and Azov Sea waters. Scientists rely on stranding data, modeling, and indirect reports, which suggest losses in the thousands but fall short of universally agreed-upon totals. The available data strongly indicate increased mortality associated with the war, but exact figures remain uncertain and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

In summary, in the context of the RUC, inland waters have suffered severe damage from infrastructure destruction (e.g., the Kakhovka Dam), industrial spills, and sewage contamination. Marine systems such as the Black Sea and Azov Sea have been exposed to widespread pollution plumes, altered salinity, biodiversity loss, and chemical contamination from petroleum products, sunken vessels, sea mines, munitions, projectiles, explosives, and submarines.

Assessing the instruments used to profile these impacts reveals the difficulty of establishing reliable and continuous water quality monitoring frameworks for both continental and marine environments under wartime conditions.

Seven of the 21 reviewed studies analyzed water samples from the most affected aquatic bodies—the Dnieper, Siverskyi Donets, and Sukhyi Torets Rivers—as well as marine coastal areas, including the heavily polluted port of Odesa on the Black Sea, and the Sea of Azov. All samples exceeded monitored water quality parameters.

Satellite imagery remains the most effective tool for documenting and evidencing the RUC’s impacts on Ukrainian waters and related aquacides. Four studies directly employed satellite data, and seven acknowledged its relevance.

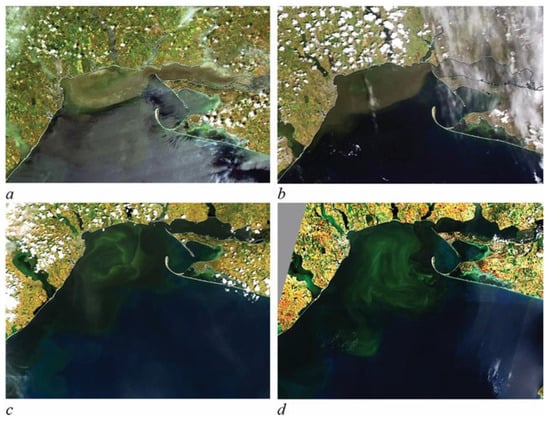

Most satellite images illustrated the Kakhovka Dam disaster (Figure 9) and subsequent pollution of the Dnieper River, its Dnieper-Bug estuary, and the northwestern Black Sea (Figure 10).

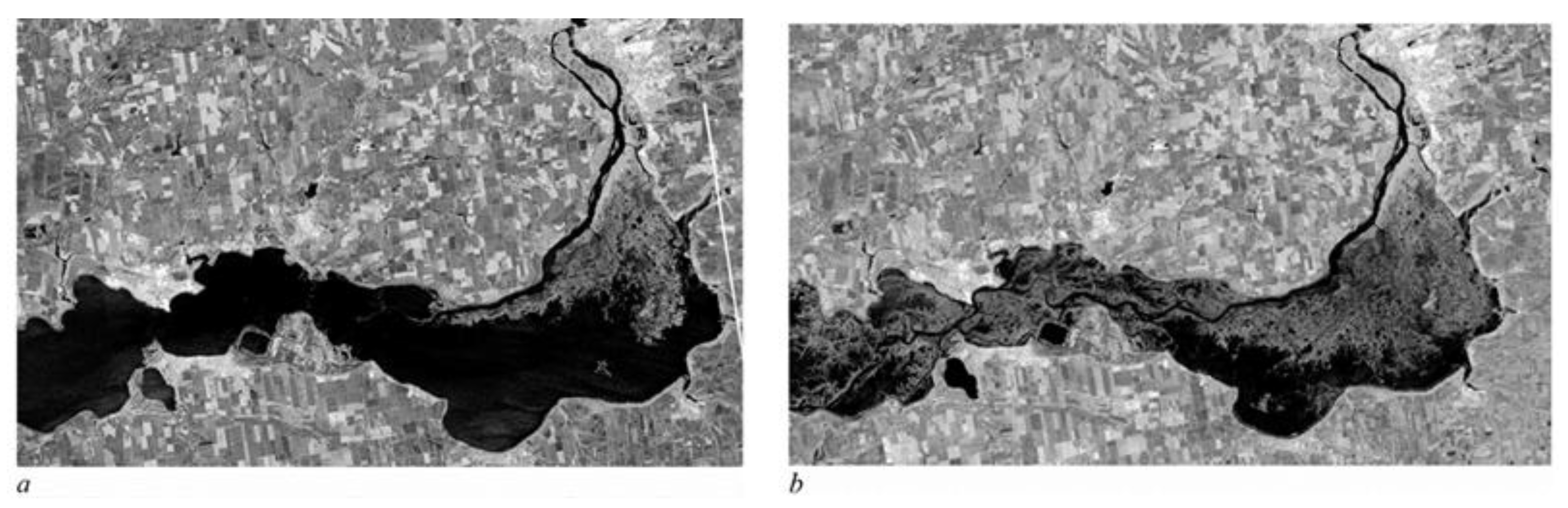

Figure 9.

Kakhovka Reservoir on (a) 9 June 2023 and (b) 16 June 2023. The desiccation of the reservoir is clearly visible following the destruction of the dam. Sentinel-1 satellite images (spatial resolution of 10 m), retrieved from Vyshnevskyi et al., 2023 [122].

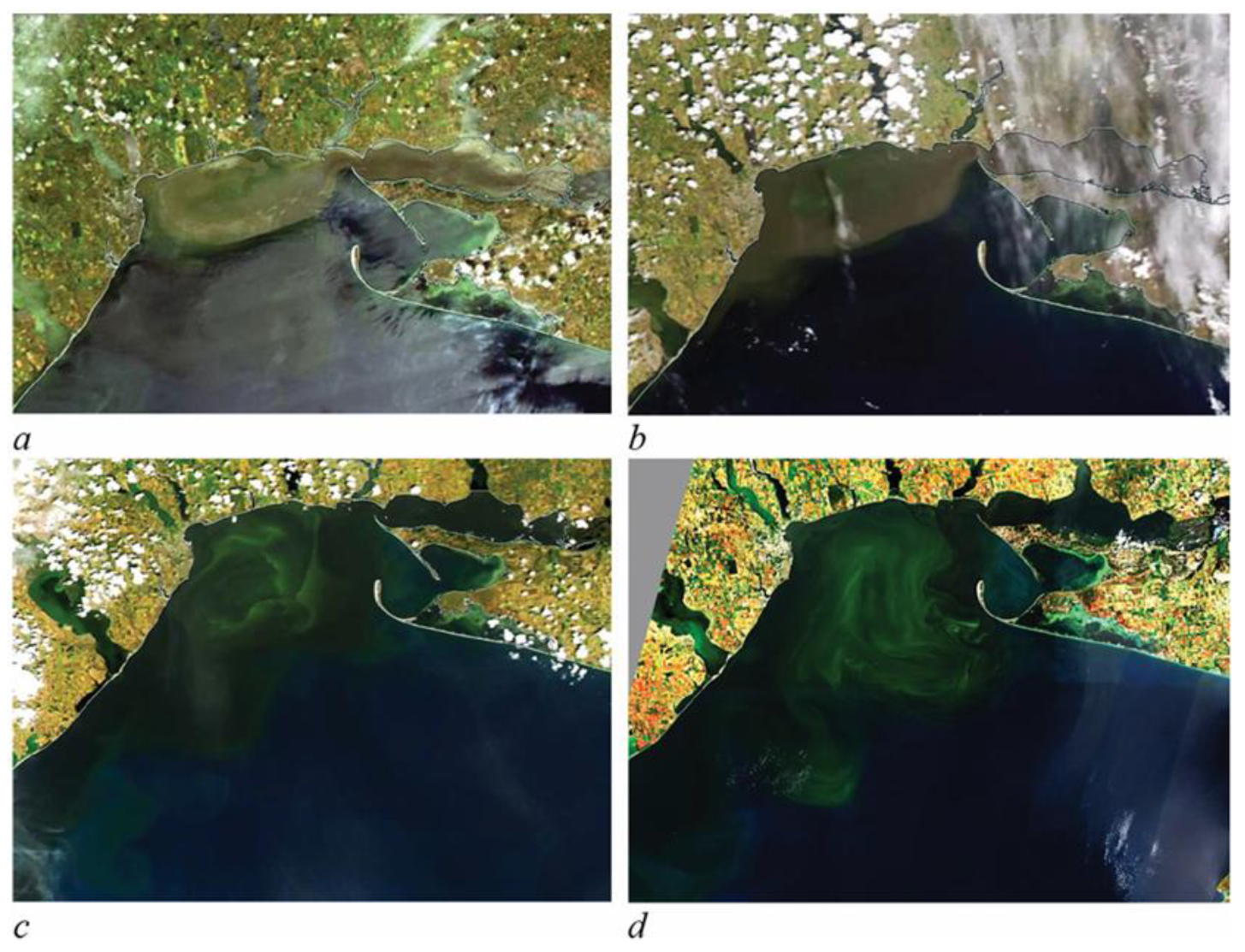

Figure 10.

Pollution of the northwestern coastal area of the Black Sea, resulting from the movement of the post-Kakhovka pollution wave through the Dnieper River and the Dnieper–Bug Estuary. Satellite imagery sourced from Vyshnevskyi et al., 2023 [122], based on data from https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov (accessed on 30 September 2025). (a,b) and https://scihub.copernicus.eu (accessed on 30 September 2025) (c,d).

For this subsection, we selected satellite images from Vyshnevskyi et al. (2023) [122], noted for their clarity. Satellite imagery is vital in wartime contexts, where field access is limited or dangerous, and also serves as a guiding tool for future aquatic restoration.

3.3. Analyses of Marine Waters Affected by the RUC

Only two studies specifically addressed war-related pollution in marine environments (Table 4), yet they provide indispensable insights into Black Sea and Sea of Azov biodiversity. Both focused on cetaceans, particularly dolphins, whose populations have sharply declined due to habitat destruction from chemical pollution and ongoing military operations. To mitigate extinction risks, medium- and long-term measures are essential, including habitat conservation, remediation of polluted waters, and strengthened international scientific cooperation to safeguard dolphins and other species in the Black Sea.

Table 4.

Keywords and key findings in the two articles analyzing the impact of the RUC on marine waters.

3.4. Mapping the Scientific Interest on Ukraine’s Regions, Rivers and Cities

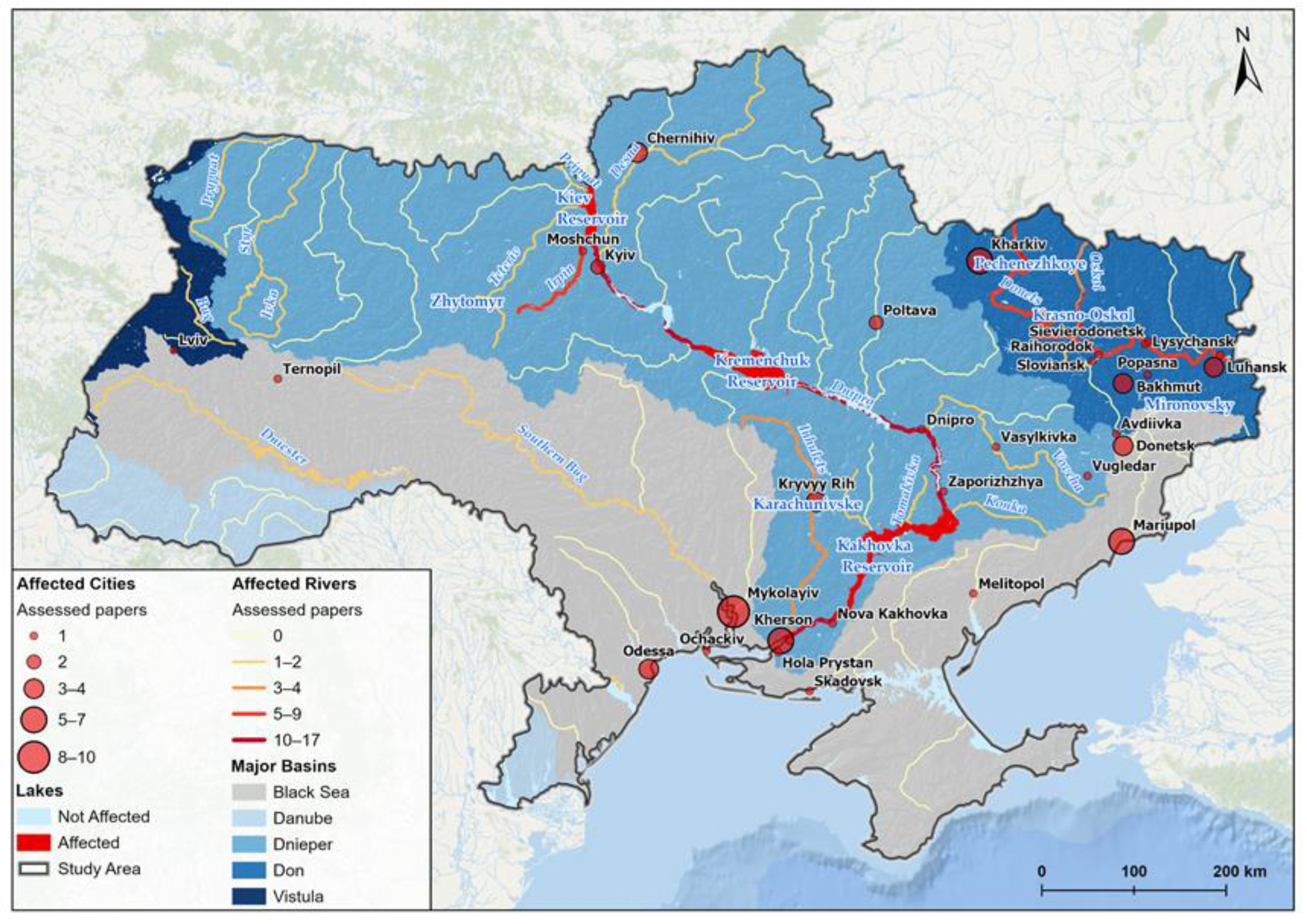

To highlight the spatial impact of the war in Ukraine, several cartographic representations were created, depicting the main regions, rivers, and cities in relation to the number of analyzed articles that focused on each location. Accordingly, Figure 11 illustrates the regions of Ukraine in relation to the number of papers evaluated for the review.

Figure 11.

Assessed papers for regions of Ukraine.

At the regional scale, most studies concentrated on the eastern oblasts, situated east of the Dniester River and close to the front line. Donetsk (17 studies: 14 on inland waters and three on both inland and marine domains) and Luhansk (13 studies: 10 inland, three both domains) stand out as the most frequently examined. Southern coastal regions also attracted considerable attention: Kherson (eight papers, including two covering both domains), Zaporizhzhia (seven papers, three both domains), and Mykolaiv (six papers, one both domains). Kharkiv was the most studied region solely for inland waters (six papers), followed by Kyiv Oblast (four) and Dnipropetrovsk (three). Additional studies addressing both inland and marine domains were found for Odesa and Crimea (two papers each), while Poltava and Kyiv City were represented only by inland water studies. In contrast, Transcarpathia and Kirovohrad appeared only once, and most western regions—Chernivtsi, Ternopil, Lviv, and Rivne—were scarcely addressed, typically through localized case studies rather than regional analyses. This distribution reflects both the geography of military operations and the visibility of aquatic disasters in the east and south.

At the river scale, shown in Figure 12, the Dnipro River dominates the scientific attention, appearing in 17 papers. Its reservoirs were frequently discussed, especially the Kakhovka Reservoir, which alone was covered in 24 articles. By comparison, the Kremenchuk and Kiev Reservoirs were each mentioned only once. The Irpin River was the second most studied (nine papers), followed by the Siverskyi Donets (eight papers), with its Pechenezhkoye Reservoir cited twice. Other rivers received more modest coverage: the Inhulets (four papers, including its Karachunivske Reservoir), the Oskil (three papers, with its reservoir), and the Teteriv (two papers). Several rivers—Ivka, Styr, Southern Bug, Bug, Pripyat, Dniester, Desna, and Vovcha—appeared only once, most of them located in western Ukraine where fewer military operations occurred. This uneven distribution underscores how conflict intensity shapes scientific focus.

Figure 12.

Assessed papers for major rivers and cities of Ukraine.

At the city scale, Mykolaiv emerged as the most frequently addressed, appearing in 10 studies (seven inland, two both domains, one marine). Mariupol followed with seven studies (four inland, two both, one marine). Kherson and Kharkiv were each covered in six papers, while Odesa and Kryvyi Rih appeared in four studies each. Chernihiv, Luhansk, and Donetsk were each mentioned three times, all in inland waters, while Bakhmut was discussed in three papers (two inland, one both). Poltava and Kyiv were cited in two studies, and several other cities—Ternopil, Lysychansk, Melitopol, Lviv, Zaporizhzhia, and Dnipro—were each addressed in a single paper. These figures highlight the prominence of southern and eastern urban centers as focal points of aquatic degradation, while western cities remain marginal in the scientific record.

4. Conclusions

This review has demonstrated the profound consequences of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict (RUC) on Ukraine’s inland and marine water systems. Drawing from 61 peer-reviewed studies, we examined the destruction of water-related infrastructure, the degradation of aquatic ecosystems, and the tools available to assess these impacts, while introducing the concept of aquacide—a targeted environmental catastrophe affecting aquatic life and water resources.

Infrastructure destruction was the most frequently reported impact, with the majority of studies documenting damage to water supply, treatment, and purification systems, alongside industrial facilities and flooded coal mines. These disruptions have severely compromised water quality and access, particularly in southern and eastern oblasts such as Odesa, Mykolaiv, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kharkiv. Aquatic pollution and biodiversity loss were equally alarming, with the Dnipro River, Siverskyi Donets, and the coastal zones of the Black Sea and Sea of Azov most affected, and particularly harming species of dolphins, mollusks, fish and migratory birds. The destruction of the Kakhovka Dam—analyzed in nearly forty percent of the reviewed studies—stands as a defining example of aquacide, with cascading effects on water quality, morphology, and species survival.

Monitoring under wartime conditions remains challenging, yet studies conducted in retaken or temporarily calm zones revealed exceedances across all measured indicators. Satellite imagery, though underutilized, proved to be a vital tool for documenting destruction, guiding restoration, modeling pollutant dispersion, and assessing public health risks. Future research should prioritize the validation of satellite-derived information with on-site sampling, the integration of hydrological and water-quality models, and the establishments of standardized monitoring frameworks.

Despite limitations in data access (publicly available reports) and reliance on secondary sources (with their heterogeneity, time gaps, and potential biases), this review fulfills its objectives: it maps the scale of aquatic destruction, identifies key regions and pollutants, and highlights the tools available for assessment. More importantly, it reveals that water has become both a victim and a weapon of war.

Restoring Ukraine’s water systems will require coordinated international efforts, combining technical expertise, scientific innovation, and policy action. Until then, halting aquacides, protecting infrastructure, and preserving water resources must remain urgent priorities, not only for Ukraine, but for the global community committed to environmental justice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.-M.M., M.-S.C. and M.-A.N.; methodology, V.-M.M., M.-S.C. and M.-A.N.; software, V.-M.M., M.-S.C. and M.-A.N.; investigation, V.-M.M., M.-S.C. and M.-A.N.; data curation, V.-M.M., M.-S.C. and M.-A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.-M.M.; writing—review and editing, V.-M.M., M.-S.C. and M.-A.N.; visualization, V.-M.M., M.-S.C. and M.-A.N.; supervision, V.-M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Awewomom, J.; Dzeble, F.; Takyi, Y.D.; Ashie, W.B.; Ettey, E.N.Y.O.; Afua, P.E.; Sackey, L.N.A.; Opoku, F.; Akoto, O. Addressing global environmental pollution using environmental control techniques: A focus on environmental policy and preventive environmental management. Discov. Environ. 2024, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaim, S.; Laarabi, B.; Chamali, H.; Dahrouch, A.; Arbaoui, A.; Rahmani, K.; Barhdadi, A.; Tlemçani, M. Optical monitoring of particulate matter: Calibration approach, seasonal and diurnal dependency, and impact of meteorological vectors. Environments 2025, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhunieti, Y.; Lasasmeh, M.; Sharif, M.A. International responsibility arising from environmental pollution. In Intelligence-Driven Circular Economy; Hannoon, A., Mahmood, A., Eds.; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, B.J.; Ray, S.; Biswas, A.K.; Dutta, S.; Roy, S.; Bhattacharjee, K.; Kotal, A. A predictive AI framework for proactive pollution control and environmental protection. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadarka, M.; Vaghela, D.; Bamaniya, K.; Sikotariya, H.; Kharadi, N.; Bamaniya, M.; Makwana, K.; Verma, P. Water Pollution: Impacts on Environment, Sustainable Aquaculture: A Step Towards a Green Future in Fish Farming; Satish Serial Publishing House: New Delhi, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Babuji, P.; Thirumalaisamy, S.; Duraisamy, K.; Periyasamy, G. Human health risks due to exposure to water pollution: A review. Water 2023, 15, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Du, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, L.; Zhu, B.; Kitaguchi, T.; Huang, C. A review on the application of biosensors for monitoring emerging contaminants in the water environment. Sensors 2025, 25, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren-Vega, W.M.; Campos-Rodríguez, A.; Zárate-Guzmán, A.I.; Romero-Cano, L.A. A current review of water pollutants in American continent: Trends and perspectives in detection, health risks, and treatment technologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochynska, S.; Duszewska, A.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M.; Wrona, M.; Szeliga, A.; Budzik, M.; Szczesnowicz, A.; Bala, G.; Trzcinski, M.; Meczekalski, B.; et al. The impact of water pollution on the health of older people. Maturitas 2024, 185, 107981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misman, N.A.; Sharif, M.F.; Chowdhury, A.J.K.; Azizan, N.H. Water pollution and the assessment of water quality parameters: A review. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 294, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsis, K. The impact of war on the environment. Eur. J. Ecol. Biol. Agric. 2024, 1, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, P.D.; Gama, M. Reviewing water wars and water weaponisation literatures: Is there an unnoticed link? Water 2025, 17, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H. Water as a weapon and casualty of armed conflict: A review of recent water-related violence in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, T.S. The Intersections of Environmental Insecurities and Civil War in Yemen. Naval Postgraduate School. September 2021. Available online: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Literathy, P. Environmental consequences of the Gulf War in Kuwait: Impact on water resources. Water Sci. Technol. 1992, 26, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.F.; Yoon, J.; Gorelick, S.M.; Avisse, N.; Tilmant, A. Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Land Use and Transboundary Freshwater Resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14932–14937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M.; Zeitoun, M.; El Sheikh, R. Conflict and Social Vulnerability to Climate Change: Lessons from Gaza. Clim. Dev. 2011, 3, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaza, H.; Ghebreyohannes, T.; Nyssen, J.; Tesfamariam, Z.; Demissie, B.; Poesen, J.; Gebrehiwot, M.; Weldemichel, T.G.; Deckers, S.; Gidey, D.G.; et al. Managing the Environmental Impacts of War: What Can Be Learned from Conflict-Vulnerable Communities? Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 171974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.J.; Stemberger, H.L.J.; Zolderdo, A.J.; Struthers, D.P.; Cooke, S.J. The Effects of Modern War and Military Activities on Biodiversity and the Environment. Environ. Rev. 2015, 23, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamidehkordi, E.; Karimi, V.; Singh, G.; Naderi, L. Water Conflicts and Sustainable Development: Concepts, Impacts, and Management Approaches. In Current Directions in Water Scarcity Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 8, pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naufal, G.; Malcolm, M.; Diwakar, V. Armed Conflict and Household Water Sources. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2024, 53, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaing, T.; Nguyen, T.P.L. An Assessment of Water Supply Governance in Armed Conflict Areas of Rakhine State, Myanmar. Water 2022, 14, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, J.; Ozerol, G.; Güven, Ş.; Heldeweg, M. Water in War: Understanding the Impacts of Armed Conflict on Water Resources and Their Management. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A.; Árias-Arévalo, P.A.; Martínez-Mera, E. Environmental Sustainability in Post-Conflict Countries: Insights for Rural Colombia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özerol, G.; Schillinger, J. Water Management and Armed Conflict. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Water Policy, Economics and Management; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, W.Y.; Umer, A. Impact of War on the Environment: Ecocide. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1539520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, R.; Masyhar, A.; Wulandari, C.; Kusuma, B.H.; Wijayanto, I.; Rasdi; Fikri, S. Ecocide as the Serious Crime: A Discourse on Global Environmental Protection. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1355, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killean, R. Ecocide’s Evolving Relationship with War. Environ. Secur. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. International Environmental Crimes and Ecocide. In Research Handbook on Environmental Crimes and Criminal Enforcement; Smith, S., Sahramaki, I., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, S. Ecocide: A Threat to Biological Tissue and Ecological Safety. Veredas Direito 2023, 20, e202416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterio, M. Crimes against the Environment, Ecocide, and the International Criminal Court. Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 2024, 56, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R. Ecocide as the Fifth International Crime: Is the Rome Statute Compatible with Ecocide? Völkerrechtsblog 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killean, R.; Short, D. A Critical Defence of the Crime of Ecocide. Environ. Politics 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duiunova, T.; Voznyk, M.; Koretskyi, S.; Chernetska, O.; Shylinhov, V. International Humanitarian Law and Ecocide: The War in Ukraine as a Case Study. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 14, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltsova, V.; Volodina, O.; Hordieiev, V.; Samoshchenko, I.; Orobets, K. Analysis of Criminal Law on Ecocide: A Case Study of War in Ukraine. Rev. Kawsaypacha Soc. Y Medio Ambiente 2024, 14, D-013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, G. Ecocide in War and Peace: From the Air Pollution Consequences of the War in Ukraine to Japan’s Disposal of Fukushima Water into the Ocean. Case W. Res. J. Int’l L 2024, 56, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Geneuss, J.; Jeßberger, F. Russian Aggression and the War in Ukraine: An Introduction. J. Int. Crim. Justice 2022, 20, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierała, T.; Pawlicz, A. War beyond National Borders: Impact of the Russian–Ukrainian War on Hotel Performances in Neighbouring Countries. Tour. Manag. 2025, 111, 105235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, R.; Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Blanco-Herrero, D. Beyond Information Warfare: Exploring Fact-Checking Research About the Russia–Ukraine War. J. Media 2025, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidmar, J. The Annexation of Crimea and the Boundaries of the Will of the People. Ger. Law J. 2015, 16, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M. The Russia–Ukraine War as a Battle for a Bordered Land, Not Borderland. Political Geogr. 2023, 101, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dück, E.; Stahl, B. Introduction: The Russia–Ukraine War as a Formative Event in Global Security Policy? Polit. Vierteljahresschr. 2025, 66, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börzel, T.A. European Integration and the War in Ukraine: Just another Crisis? J. Common Mark. Stud. 2023, 61, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liventseva, H. The Mineral Resources of Ukraine. Tierra Y Tecnologia 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujala, P. The Spoils of Nature: Armed Civil Conflict and Rebel Access to Natural Resources. J. Peace Res. 2010, 47, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solokha, M.; Demyanyuk, O.; Symochko, L.; Mazur, S.; Vynokurova, N.; Sementsova, K.; Mariychuk, R. Soil Degradation and Contamination Due to Armed Conflict in Ukraine. Land 2024, 13, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulich, M.P.; Kharchenko, O.O.; Yemchenko, N.L.; Olshevska, O.D.; Lyubarska, L.S. War in Ukraine: Agricultural Soil Degradation and Pollution and Its Consequences. Hyg. Popul. Places 2024, 74, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Yo, S.; Wang, S. Russia–Ukraine War Perspective of Natural Resources Extraction: A Conflict with Impact on Sustainable Development. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H. Impacts of the Russia–Ukraine War on Global Food Security: Towards More Sustainable and Resilient Food Systems? Foods 2022, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Fedoruk, M.; Paulino Pires Eustachio, J.H.; Barbir, J.; Lisovska, T.; Lingos, A.; Baars, C. How the War in Ukraine Affects Food Security. Foods 2023, 12, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khilchevskyi, V.; Grebin, V.V.; Dubniak, S.S.; Zabokrytska, M.; Pushkar, H. Large and Small Reservoirs of Ukraine. J. Water Land Dev. 2022, 52, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safranov, T.; Berlinskyi, N.; Volkov, A. Water Resources of Ukraine: Usage, Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment (with Detailed Description of Odessa Region). Environ. Probl. 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- WAREG. Protection of Water Resources of Ukraine: From Crisis to Recovery. 2023. Available online: https://www.wareg.org/articles/protection-of-water-resources-of-ukraine-from-crisis-to-recovery/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Khilchevskyi, V.K. Characteristics of Water Resources of Ukraine Based on the Database of the Global Information System FAO Aquastat. Hydrol. Hydrochem. Hydroecol. 2021, 1, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokal, V. Transboundary Rivers of Ukraine: Perspectives for Sustainable Development and Clean Water. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2021, 18, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralampiev, M.; Panayotova, M. The War in Ukraine from 2022 and Its Impact on the Environment. Bulg. J. Int. Econ. Politics 2022, 2, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanoshenko, O.; Halaktionov, M.; Huber-Humer, M. Exploratory Study on the Impact of Military Actions on the Environment and Infrastructure in the Current Ukraine War with a Specific Focus on Waste Management. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 43, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vet, F. A Polluting War: Risk, Experts, and the Politics of Monitoring Wartime Environmental Harm in Eastern Ukraine. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2024, 42, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichura, V.; Potravka, L.; Skrypchuk, P.; Stratichuk, N. Anthropogenic and Climatic Causality of Changes in the Hydrological Regime of the Dnieper River. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terebukh, A.; Pankiv, N.; Roik, O. Integral Assessment of the Impact on Ukraine’s Environment of Military Actions in the Conditions of Russian Aggression. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2023, 24, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorali, H.; Zaki, Y.; Campana, M.; Taheri, A. Hydropolitics of Russian–Ukrainian War: Analyzing Water Governance Conflicts in the Dnieper River Basin through Remote Sensing Techniques. GeoJournal 2025, 90, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, J.; Sobota, M.; Świąder, M.; Borowski, P.; Moryl, A.; Stodolak, R.; Kucharczak, E.; Zięba, Z.; Kazak, J.K. Marine Waste—Sources, Fate, Risks, Challenges and Research Needs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urios, L. Metallic Shipwrecks and Bacteria: A Love–Hate Relationship. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvach, Y.; Stepien, C.A.; Minicheva, G.G.; Tkachenko, P. Biodiversity Effects of the Russia–Ukraine War and the Kakhovka Dam Destruction: Ecological Consequences and Predictions for Marine, Estuarine, and Freshwater Communities in the Northern Black Sea. Ecol. Process. 2025, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpatova, O.; Maksymenko, I.; Patseva, I.; Khomiak, I.; Gandziura, V. Hydrochemical State of the Post-Military Operations Water Ecosystems of the Moschun, Kyiv Region. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference Monitoring of Geological Processes and Ecological Condition of the Environment, Kyiv, Ukraine, 15–18 November 2022; Volume 2022, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.H.; Soleman, S.R.; Ang, J.S.M.; Trzcinski, A.P. Conflict-Related Environmental Damages on Health: Lessons Learned from the Past Wars and Ongoing Russian Invasion of Ukraine. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2022, 27, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, P.; Bašić, F.; Bogunovic, I.; Barceló, D. Russian-Ukrainian War Impacts the Total Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 837, 155865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawtani, D.; Gupta, G.; Khatri, N.; Rao, P.K.; Hussain, C.M. Environmental Damages Due to War in Ukraine: A Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorina, O.V.; Ivanko, O.M.; Danilenko, O.M.; Skapa, T.V.; Mavrykin, Y.O.; Polishchuk, O.S. Scientific Substantiation of Conceptual Approaches to the Development of a Regulatory Document on the Quality of Drinking Water under Condition of Martial Law. Ukr. J. Mil. Med. 2022, 3, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanasyev, S. Impact of War on Hydroecosystems of Ukraine: Conclusion of the First Year of the Full-Scale Invasion of Russia (a Review). Hydrobiol. J. 2023, 59, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.; Yushchuk, O. The War in Ukraine and Its Impact on Regional Security. In State of the Region Report 2023; Wesslau, F., Ed.; Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023; pp. 206–212. ISBN 978-91-89315-83-5. [Google Scholar]

- Didyk, V.I.; Homanyuk, M.A. Ecocide on the Territory of Kherson Region in 2022–2023. In Ecology Is a Priority: All-Ukrainian Student English-Speaking Conference, April 19, 2023; Maksymenko, N.V., Ed.; V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University: Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2023; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, P.; Vyshnevskyi, V.; Shevchuk, S. Rivers and Water Systems as Weapons and Casualties of the Russia-Ukraine War. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2023EF003910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitowski, I.; Sujak, A.; Drygaś, M. The Water Dimensions of Russian–Ukrainian Conflict. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2023, 23, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahats, N. Principles of Water Infrastructure Management in Ensuring Sustainable Water Use in Ukraine. Agora Int. J. Econ. Sci. 2023, 17, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matviichuk, O.; Yeromenko, R.; Lytvynova, O.; Dolzhykova, O.; Matviichuk, A.; Karabut, L.; Lytvynenko, H.; Gladchenko, O.; Lytvynenko, N. Hygienic Assessment of Potential Health Risks for the Population of Ukraine and the Kharkiv Region as a Result of the Deterioration of Drinking Water Supply in the Conditions of War. Sci. Rise Med. Sci. 2023, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padányi, J.; Földi, L. The Effects of Armed Conflicts on the Environment. Contemp. Mil. Chall. 2023, 25, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schevchuk, S. Ecological Consequences of Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine: Accountability, Compensation, and Sustainable Recovery. In Designed in Brussels, Made in Ukraine: Future of EU–Ukraine Relations; Alesina, M., Ed.; European Liberal Forum: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; pp. 69–76. ISBN 978-2-39067-055-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, A.C. The Environmental Implications of War: Analysis of the Spectacular and Slow Environmental Violence Inflicted through Russia’s Deliberate Targeting and Weaponization of Ukrainian Environments. Bachelor’s Thesis, Bates College, Lewiston, ME, USA, 2023; p. 309. Available online: https://scarab.bates.edu/envr_studies_theses/309 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Solokha, M.; Pereira, P.; Symochko, L.; Vynokurova, N.; Demyanyuk, O.; Sementsova, K.; Inacio, M.; Barceló, D. Russian-Ukrainian War Impacts on the Environment: Evidence from the Field on Soil Properties and Remote Sensing. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmakh, V.; Melniichuk, M.; Melnyk, O.; Tokarchuk, I. Hydro-Ecological State of Ukrainian Water Bodies under the Influence of Military Actions. Rocz. Ochr. Środowiska 2023, 25, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokal, V.; Kurovska, A.; Strokal, M. More River Pollution from Untreated Urban Waste Due to the Russian-Ukrainian War: A Perspective View. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2023, 20, 2281920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasova, O.; Shevchenko, A.; Shevchenko, I.; Kozytsky, O. Monitoring of Water Bodies and Reclaimed Lands Affected by Warfare Using Satellite Data. Land Reclam. Water Manag. 2023, 2, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. The Unprecedented Ramsar Resolution: Ukrainian Wetlands Protection in Armed Conflict. Neth. Int. Law Rev. 2023, 70, 323–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blahopoluchna, A.; Dzhoha, O.; Parakhnenko, V.; Liakhovska, N. Impact of the Consequences of the War in Ukraine on the Environmental Condition of Drinking Water. Sci. Eur. 2024, 136, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cherniavska, T.; Tanklevska, N.; Cherniavskyi, B. A Decision-Making System for Managing the Remediation of Water Resources in the Kherson Region: Agent-Oriented Modeling in the Context of Post-War Economic Recovery. In Transformations of National Economies under Conditions of Instability; Cherniavska, T., Ed.; Scientific Route OÜ: Tallinn, Republic of Estonia, 2024; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Fedoruk, M.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Splodytel, A.; Smaliychuk, A.; Szynkowska-Jóźwik, M.I. The Environment as the First Victim: The Impacts of the War on the Preservation Areas in Ukraine. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Fedoruk, M.; Lisovska, T. War in Ukraine: An Overview of Environmental Impacts and Consequences for Human Health. Front. Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapich, H.; Novitskyi, R.; Onopriienko, D.; Dent, D.; Roubik, H. Water Security Consequences of the Russia-Ukraine War and the Post-War Outlook. Water Secur. 2024, 21, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapich, H.; Novitskyi, R.; Onopriienko, D.; Dubov, T. Water on Fire: Losses and the Post-War Future of Ecosystem Services from Water Resources of Ukraine. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herasymchuk, L.; Patseva, I.M.; Valerko, R.; Ustymenko, V. Military Actions in Ukraine as Ecocide and Challenge to Formulas of Peace. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 18, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litynska, M.I.; Pelekhata, O.B. The Influence of the War on the Content of Some Components in the Rivers of Ukraine. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1415, 012094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkivskyi, M.; Taras, T. Pollution of the Atmosphere, Soil and Water Resources as a Result of the Russian-Ukrainian War. Ecol. Saf. Balanced Use Resour. 2024, 15, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezbrytska, I.; Bilous, O.; Sereda, T.; Ivanova, N.; Pohorielova, M.; Shevchenko, T.; Dubniak, S.; Lietytska, O.; Zhezherya, V.; Polishchuk, O.; et al. Effects of War-Related Human Activities on Microalgae and Macrophytes in Freshwater Ecosystems: A Case Study of the Irpin River Basin, Ukraine. Water 2024, 16, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitskyi, R.; Hapich, H.; Maksymenko, M.; Kutishchev, P.; Gasso, V. Losses in Fishery Ecosystem Services of the Dnipro River Delta and the Kakhovske Reservoir Area Caused by Military Actions in Ukraine. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K. Environmental Impact of Kakhovka Dam Breach and Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Explosion on Dnieper River Landscape. Open J. Soil Sci. 2024, 14, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergieieva, K.; Kavats, O.; Vasyliev, V.; Kavats, Y.; Kovrov, O. Machine Learning-Based Monitoring of War-Damaged Water Bodies in Ukraine Using Satellite Images. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference Information Control Systems & Technologies (ICST 2024), Odesa, Ukraine, 23–25 September 2024; CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Volume 3790, pp. 422–434. [Google Scholar]

- Shkurashivska, S.; Nechytailo, L.; Ersteniuk, A. Assessment of the Impact of Military Actions on the Environment of Ukraine. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference Teaching, Learning, Medical and Psychological Support as Challenges of 21st Century Education, Warsaw, Poland, 25 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snizhko, S.; Didovets, I.; Shevchenko, O.; Yatsiuk, M.; Hattermann, F.F.; Bronstert, A. Southern Bug River: Water Security and Climate Changes Perspectives for Post-War City of Mykolaiv, Ukraine. Front. Water 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snizhko, S.; Didovets, I.; Bronstert, A. Ukraine’s Water Security under Pressure: Climate Change and Wartime. Water Secur. 2024, 23, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Koeckritz, F.C. A Method to Determine Ecocide from a Landscape Perspective: The Nova Kakhovka Dam Case in the Russia-Ukraine War. Master’s Thesis, Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Institute of Urbanism and Landscape, Oslo, Norway, 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/chrisfvk_three-months-since-completing-my-masters-activity-7245782400226447360-1xPc/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Albakjaji, M. The Responsibility for Environmental Damages During Armed Conflicts: The Case of the War between Russia and Ukraine. Access Justice East. Eur. 2022, 4, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Zhao, W.; Symochko, L.; Inacio, M.; Bogunovic, I.; Barcelo, D. The Russian-Ukrainian Armed Conflict Will Push Back the Sustainable Development Goals. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algan, N.; Aydoğan, G.K. Russian Federation–Ukraine War as an Environmental Security Issue on the Black Sea. J. Black Sea/Medit. Environ. 2023, 29, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kharchenko, V. The Impact of a Full-Scale War on the Black Sea Ecosystems of Ukraine and the Entire Sea in General. In Proceedings of the European Dimensions of the Sustainable Development and Academic–Business Forum: Let’s Revive Ukraine Together; Selected Papers of the V International Conference, Kyiv, Ukraine, 1–2 June 2023; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Khrushch, O.; Moskalets, V.; Fedyk, O.; Karpiuk, Y.; Hasiuk, M.; Ivantsev, N.; Ivantsev, L.; Arjjumend, H. Environmental and Psychological Effects of Russian War in Ukraine. Grassroots J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 6, 37–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, I. Crime of Ecocide in Ukraine—Environmental Consequences of Russian Military Aggression. Studia Prawnicze KUL 2024, 4, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, J. When the Environment Becomes a Victim of Armed Conflict—The Rhetoric, the Blame Game, and the Pursuit of Justice. Master’s Thesis, Stockholm University, Department of Economic History and International Relations, Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. Available online: https://su.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1797894 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Serbov, M.; Kramarenko, I.; Irtyshcheva, I.; Stehnei, M.; Boiko, Y.; Hryshyna, N.; Khaustova, K. The Efficiency of Water Resources Management in the Black Sea Region (Ukraine) in the Context of Sustainable Development under the Conditions of Military Operations. Stud. Reg. Loc. 2023, 93, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumilova, O.; Tockner, K.; Sukhodolov, A.; Khilchevskyi, V.; De Meester, L.; Stepanenko, S.; Trokhymenko, G.; Hernández-Agüero, J.A. Impact of the Russia–Ukraine Armed Conflict on Water Resources and Water Infrastructure. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmid, A.; Khanam, S.; Rashid, M.M.; Ibnat, F. Reviewing the Impact of Military Activities on Marine Biodiversity and Conservation: A Study of the Ukraine-Russia Conflict within the Framework of International Law. Grassroots J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 6, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyshnevskyi, V.; Shevchuk, S.; Komorin, V.; Oleynik, Y.; Gleick, P. The Destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and Its Consequences. Water Int. 2023, 48, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopchak, I.; Zhuk, V. Impact of War Actions on Water Resources of Ukraine. In Circular Economy in Ukraine—A Chance for Transformation in Industry and Services; Antoniuk, N., Bochko, O., Kulczycka, J., Eds.; MEERI PAS: Krakow, Poland, 2024; Chapter II; pp. 79–90. ISBN 978-83-67606-39-4, e-ISBN 978-83-67606-40-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hryhorczuk, D.; Levy, B.S.; Prodanchuk, M.; Kravchuk, O.; Bubalo, N.; Hryhorczuk, A.; Erickson, T.B. The Environmental Health Impacts of Russia’s War on Ukraine. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2024, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharytonov, S.O.; Orlovskyi, R.; Us, O.; Iashchenko, A.; Maslova, O. Criminal Responsibility for Ecocide Resulting from the Military Aggression of Russia. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 14, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovska, M.; Prekrasna-Kviatkovska, Y.; Dykyi, E. Bacteriological Pollution in the Black Sea Coastal Waters after the Destruction of Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant Dam. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichura, V.; Potravka, L.; Dudiak, N. Natural and Climatic Transformation of the Kakhovka Reservoir after the Destruction of the Dam. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichura, V.; Potravka, L.; Dudiak, N.; Hyrlya, L. The Impact of the Russian Armed Aggression on the Condition of the Water Area of the Dnipro-Buh Estuary System. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2024, 25, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, O.; Horiacheva, K. Ecological Component of the Russian-Ukrainian War. In Proceedings of the International Conference Knowledge-Based Organization, Sibiu, Romania, 13–15 June 2024; Volume 30, pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakhova, N.; Oliinyk, I.; Karuk, N.; Kazmirchuk, N. Environmental Problems of Ukraine during the War Period: Ways of Them Overcoming. ETR 2024, 1, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokal, V.; Berezhniak, Y.; Naumovska, O.; Vahaliuk, L.; Ladyka, M.; Pavliuk, S.; Palamarchuk, S.; Serbeniuk, H. Natural Resources of Ukraine: Consequences and Risks of Russian Aggression. Biol. Syst. Theory Innov. 2024, 15, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyshnevskyi, V.; Shevchuk, S. The Destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and the Future of the Kakhovske Reservoir. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 81, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzhun, K. Observation of Cetaceans’ Population Dynamic in the Black Sea. Master’s Thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2023. Available online: https://bora.uib.no/bora-xmlui/handle/11250/3071235 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Kyrii, S.; Litynska, M.; Misevych, A. The War Impact on Ukraine’s Marine Environment. Water Water Purif. Technol. Sci. Technol. News 2024, 38, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.