Abstract

This study presents a simulation-based framework for PID controller design in strongly nonlinear dynamical systems. The proposed approach avoids system linearization by directly minimizing a performance index using metaheuristic optimization. Three strategies—Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), and their hybrid combination (PSO-GWO)—were evaluated on benchmark systems including pendulum-like, Duffing-type, and nonlinear damping dynamics. The chaotic Duffing oscillator was used as a stringent test for robustness and adaptability. Results indicate that all methods successfully stabilize the systems, while the hybrid PSO-GWO achieves the fastest convergence and requires the fewest cost function evaluations, often less than 10% of standalone methods. Faster convergence may induce aggressive transients, which can be moderated by tuning the ISO (Integral of Squared Overshoot) weighting. Overall, swarm-based PID tuning proves effective and computationally efficient for nonlinear control, offering a robust trade-off between convergence speed, control performance, and algorithmic simplicity.

1. Introduction

The Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controller remains one of the most fundamental and widely adopted strategies in industrial automation, process control, and mechatronic systems. Its enduring popularity is attributed to its conceptual simplicity, robustness, and ease of implementation across diverse application domains. Despite its ubiquity, achieving optimal performance through appropriate tuning of the PID gains continues to be a challenging and active area of research. This challenge becomes particularly pronounced in nonlinear or time-varying systems, where conventional tuning rules derived from linearized models—such as the Ziegler–Nichols or Cohen–Coon methods—often result in degraded transient behavior, excessive overshoot, or even closed-loop instability. In safety-critical or high-precision applications, such responses are often unacceptable, motivating the need for more advanced and adaptive tuning methodologies.

Classical and modern treatments of PID control, including those by Åström and Hägglund [1], Nise [2], and Ogata [3], provide extensive foundations for PID design across linear and nonlinear systems. A recent and comprehensive review of modern approaches—including nonlinear extensions, soft-computing techniques, and adaptive strategies—is provided in [4].

In parallel with these advancements, recent research in robotics and biomechatronics demonstrates a strong shift toward nonlinear, optimization-driven, and bio-inspired control methods. Examples include bioinspired vibration-isolation control in active suspended backpacks [5], disturbance–observer-based compensation for tendon–sheath actuated humanoid robot hands [6], neuro-fuzzy musculoskeletal model-driven assist-as-needed control for rehabilitation robots [7], and human-in-the-loop optimized exoskeleton assistance for improving running energetics [8]. These studies highlight the growing relevance of intelligent and optimization-enhanced control strategies in complex nonlinear systems, reinforcing the motivation for developing robust metaheuristic PID-tuning frameworks such as those examined in this work.

In recent decades, metaheuristic optimization techniques have emerged as powerful and flexible alternatives to traditional analytical tuning methods. These algorithms are particularly effective for highly nonlinear, nonconvex, and multimodal optimization landscapes, including those encountered in nonlinear control. A broad overview of nature-inspired metaheuristics is given in [9]. Among these methods, the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm [10,11,12] and the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) [13] have shown remarkable success due to their complementary strengths in exploitation and exploration.

Hybrid PSO-GWO strategies combine these advantages and have been successfully applied across diverse engineering problems. For instance, Lu et al. [14] developed a GWOPSO-PID controller for pump–motor servo systems, demonstrating significantly improved rise time, noise immunity, and robustness under varying load conditions. Similarly, Portillo et al. [15] used PSO to optimally tune robust nonlinear trajectory controllers for single-rotor UAVs, showing substantial performance gains in the presence of wind disturbances.

Beyond control applications, PSO-GWO hybridization has been studied more fundamentally. Vargas et al. [16] analyzed the shared mechanisms of exploration and attraction underlying PSO and GWO, proposing REAB-based variants that outperform classical formulations on controller tuning benchmarks. These results support the growing view that hybrid swarm intelligence algorithms provide more reliable convergence and improved exploration–exploitation balance.

Metaheuristic PID optimization has also been applied to various domain-specific nonlinear control problems. Zambou et al. [17] proposed a nonlinear PID-based MPPT strategy for photovoltaic systems, where PSO-optimized gains improve robustness under fluctuating environmental conditions. Similarly, Said Solaiman et al. [18] introduced a hybrid Newton–Sperm Swarm Optimization algorithm for solving nonlinear equation systems, showing that hybridization can significantly accelerate convergence and reduce sensitivity to local minima. In the context of precision agriculture, Yang et al. [19] developed a PSO-enhanced fuzzy PID controller for electrical conductivity regulation in integrated water–fertilizer irrigation systems, achieving substantially reduced overshoot and settling time compared to conventional and fuzzy PID controllers, while maintaining high field-level accuracy under varying environmental conditions.

Despite these advances, existing studies predominantly address linear or weakly nonlinear systems, transfer-function-based formulations, or constrained benchmark problems. None of the aforementioned works have examined metaheuristic-based PID tuning for fully nonlinear dynamical systems with state-dependent nonlinearities, such as pendulum-type or Duffing-type oscillators exhibiting strong coupling, multi-scale dynamics, or even chaotic behavior. This gap is particularly significant, as nonlinear systems often invalidate assumptions underlying linear PID tuning or frequency-domain optimization.

Motivation for the PSO-GWO Hybrid Approach

A wide range of metaheuristic optimization methods has been proposed in the literature, including Genetic Algorithms (GAs), the Firefly Algorithm (FA), neural-network-based optimization, and numerous variants of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). Although these approaches are often effective for complex search problems, each exhibits characteristic limitations that can be particularly restrictive when tuning PID controllers for nonlinear dynamical systems. PSO, for instance, provides rapid local refinement due to its velocity–position update mechanism and its direct use of personal and global best information. This strong exploitation capability, however, is accompanied by an inherent tendency to lose population diversity, which may lead to premature convergence in multimodal or highly irregular optimization landscapes.

Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), on the other hand, maintains diversity and performs robust global search through its hierarchical leadership structure (, , ) and encircling behavior. These mechanisms encourage multiple candidate solutions to explore the search space broadly and collaboratively. While this improves global exploration and reduces the risk of stagnation, the algorithm generally converges more slowly during the final stages of optimization, where fine-grained parameter adjustment is required.

The proposed PSO-GWO hybrid algorithm leverages the complementary strengths of both paradigms. GWO contributes strong global exploration and preserves population diversity during the early and intermediate phases of the search, preventing premature convergence and allowing the algorithm to identify promising regions of the parameter space. Once such regions are discovered, PSO provides fast and accurate exploitation, accelerating fine-tuning and improving convergence precision. This coordinated combination directly addresses common drawbacks of standalone metaheuristics—such as imbalanced exploration–exploitation behavior, stagnation, and sensitivity to initialization—and results in a more robust and efficient optimization framework for PID tuning in nonlinear systems.

To investigate the effectiveness of this hybrid strategy, the present work systematically evaluates three metaheuristic-based PID tuning approaches for nonlinear control systems:

- PSO-based PID tuning, which relies on swarm intelligence and velocity-guided refinement for efficient local exploitation;

- GWO-based PID tuning, which employs hierarchical search mechanisms to maintain diversity and enhance global exploration;

- Hybrid PSO-GWO tuning, which integrates both mechanisms to balance exploration and exploitation and to improve convergence performance under strong nonlinearities.

The proposed optimization framework is applied to representative second-order nonlinear benchmark systems, including pendulum-type, Duffing-type, and nonlinear damping models. The optimization objective combines integral-based performance indices—specifically the Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE) and the Integral of Squared Overshoot (ISO)—to capture both transient accuracy and overshoot suppression. Special attention is given to the influence of the ISO weighting coefficient , which provides an additional degree of freedom for regulating the trade-off between convergence speed and control smoothness across different nonlinear systems.

Simulation results demonstrate that all three optimization methods effectively stabilize the considered nonlinear systems. While the hybrid PSO-GWO consistently achieves the lowest number of cost function evaluations, it may exhibit more aggressive transient dynamics, which can be mitigated by the appropriate tuning of . These findings highlight the potential of metaheuristic-based PID tuning—especially in hybrid form—as a powerful and computationally efficient tool for nonlinear control system design.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the mathematical formulation of the nonlinear systems and the associated control structure. Section 3 describes the proposed optimization framework for PID tuning. Section 4 introduces the benchmark nonlinear systems and evaluates the performance of the proposed approaches. Section 5 provides a comparative discussion, including a robustness evaluation on a chaotic Duffing oscillator. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the key findings and outlines directions for future research.

2. Problem Formulation

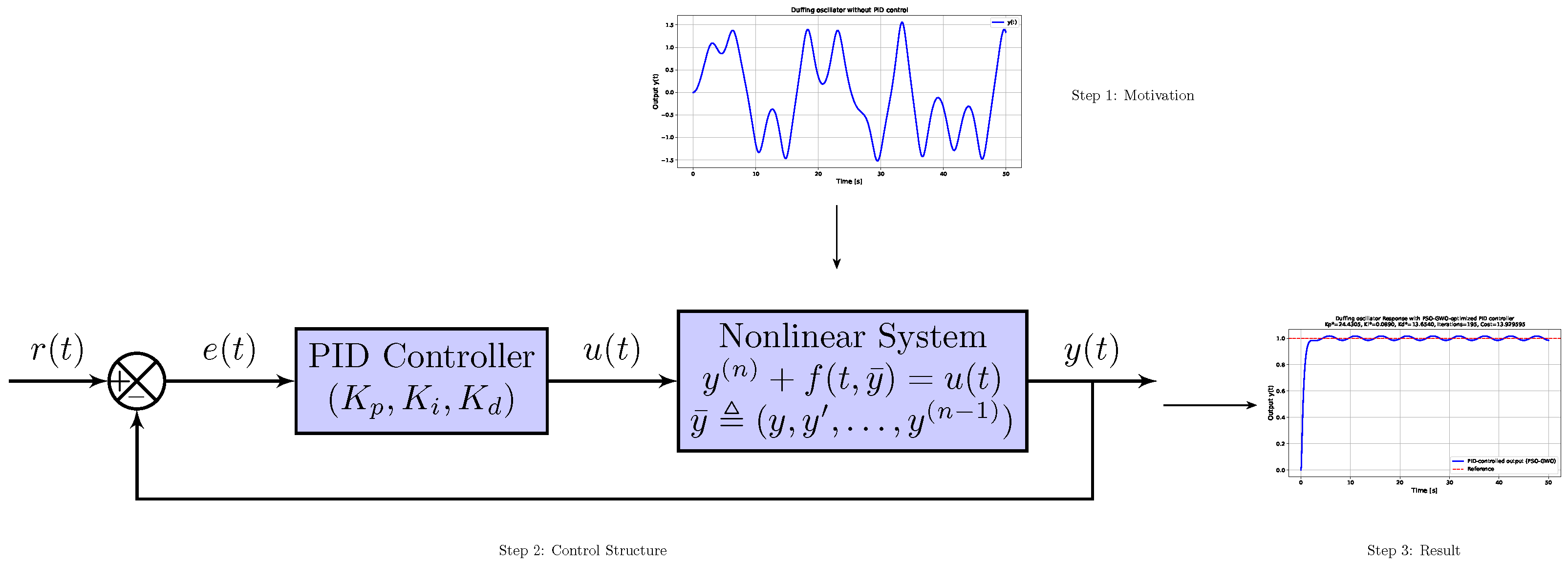

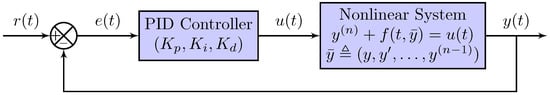

Consider a general nth-order nonlinear dynamic system defined as

over the interval , with zero initial conditions

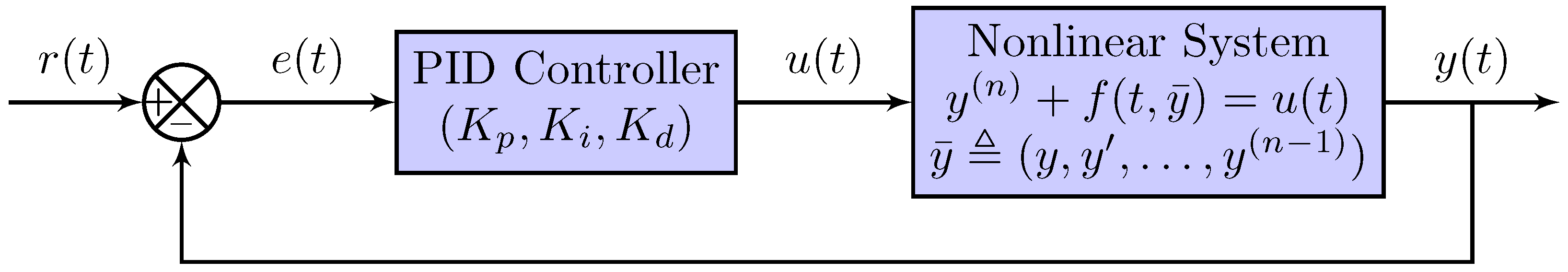

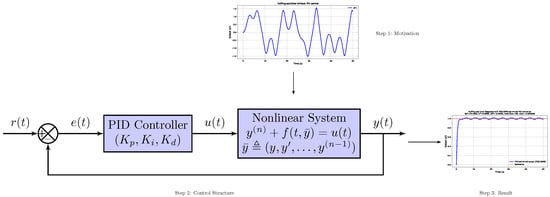

In the feedback control configuration shown in Figure 1, represents the control signal generated by the PID controller and applied to the system input, while denotes the process (or output) variable whose behavior is being regulated. Both and are assumed to be scalar functions defined on the interval and to possess the required degree of continuous differentiability on this interval.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the feedback control loop with reference input , controlled output , and control signal generated by a PID controller.

The PID controller is expressed as

where is the tracking error between the reference input and the system output .

By analyzing the closed-loop signal flow in Figure 1, the dynamics of the nth-order nonlinear system under PID control can be written as

For numerical implementation and analysis, the system can be equivalently represented in an augmented first-order state–space form using the state vector

In this study, we focus exclusively on second-order systems () with a unit-step reference input, defined as

where denotes the desired reference trajectory that the system output is expected to track.

Second-order systems exhibit more complex transient behavior than first-order systems, including overshoot, oscillations, and slower settling times, providing a richer testbed for evaluating the effectiveness of different PID tuning strategies. The simulation setup examines the system’s transient response when the input undergoes a step change from zero to unity, allowing the direct comparison of various optimization-based tuning methods under realistic nonlinear dynamics.

3. Optimization Framework

The objective of PID tuning is to determine the optimal controller gains , , and such that the closed-loop system achieves the desired transient performance while maintaining stability and minimizing overshoot. In essence, the PID controller continuously adjusts its control action to keep the actual process output as close as possible to the reference signal . In this paper, the reference input is defined as a unit-step function. The unit-step signal is commonly employed in control system analysis and simulation because it effectively excites the system dynamics and provides a clear characterization of transient and steady-state behavior. Its simplicity allows for straightforward evaluation of key performance indicators such as rise time, settling time, and overshoot, which are critical for assessing control quality. Consequently, the step response serves as a standard benchmark for tuning and comparing PID control strategies across both linear and nonlinear systems.

To quantify this objective, we adopt a composite performance index that accounts for both the speed of response and the magnitude of undesirable deviations:

where is the tracking error between the reference input and system output .

The first term, , represents the Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error. It penalizes errors that persist over longer time intervals, thereby promoting fast settling, short transient duration, and small steady-state deviations.

The second term, , corresponds to the Integral of Squared Overshoot. This one-sided penalty activates only when the system output exceeds the reference value (i.e., when ), selectively penalizing overshoot and undesirable oscillatory behavior without affecting undershoot or slow responses.

Although both components depend on the tracking error , they capture fundamentally different aspects of the closed-loop dynamics: ITAE focuses on long-duration error, while ISO specifically targets amplitude-related transients such as overshoot.

The weighting factor provides a tunable mechanism for balancing these two objectives. Because the magnitudes of the ITAE and ISO terms can differ substantially across nonlinear systems, is intentionally not normalized; instead, it serves as a regularization parameter that allows the designer to emphasize either fast convergence (ITAE) or overshoot suppression (ISO). This flexibility enables the performance index to adapt to a wide class of nonlinear dynamics while preventing any single term from dominating the optimization process. Moreover, parameter combinations that produce large overshoot or unstable behavior naturally yield high ISO values, ensuring that such solutions are strongly penalized and avoided during optimization.

The finite time horizon T is selected to sufficiently capture both transient dynamics and steady-state behavior, ensuring that the resulting PID parameters yield a balance between rapid response, overshoot control, and long-term stability.

By employing this performance index as the objective function, metaheuristic optimization algorithms such as PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO-GWO can systematically search the multidimensional space of , , and to identify near-optimal solutions without requiring explicit linearization or analytical design formulas. This approach enables robust PID tuning for nonlinear systems, accommodating complex dynamical behaviors that are challenging to handle using classical methods.

3.1. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

In the context of PID controller optimization, the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm treats each particle in the swarm as a potential solution defined by a triplet of controller gains . During the optimization process, particles iteratively adjust their positions in the search space based on both their individual best experiences and the collective knowledge of the swarm. The objective is to minimize the predefined performance index , typically expressed as a weighted combination of integral error measures such as the ITAE and ISO criteria defined in Equation (9). Due to its velocity-based update mechanism, PSO exhibits strong local search capability (exploitation), enabling fast convergence toward promising regions of the cost landscape. However, this characteristic also increases the risk of premature convergence in multimodal or highly nonlinear problems, where sufficient exploration of alternative regions is required [13].

3.2. Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)

The Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) is a nature-inspired metaheuristic based on the cooperative hunting behavior and hierarchical leadership structure observed in grey wolf packs. Within the context of PID controller tuning, each wolf represents a candidate set of controller gains , while the search process is guided by three leading wolves—, , and —representing the best solutions found so far. The remaining wolves update their positions by mimicking the encircling and hunting behavior of the leaders, gradually refining their estimates toward the global optimum. In contrast to PSO, GWO exhibits stronger exploratory behavior, preserving population diversity and systematically scanning the search space through adaptive encircling and shrinking mechanisms [13]. By effectively balancing exploration and exploitation through this hierarchical mechanism, GWO achieves stable convergence and robustness in complex, nonconvex optimization landscapes.

3.3. Hybrid Strategy: PSO-GWO

The hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm combines the exploitation strength of PSO with the exploration capability of GWO. In this hybrid framework, the PSO component provides rapid local refinement by updating particle velocities and positions, ensuring efficient convergence in promising regions. Conversely, the GWO mechanism maintains global diversity and exploration by emulating the social hierarchy and cooperative hunting strategy of grey wolves. This complementary interaction allows the hybrid algorithm to dynamically balance global exploration and local exploitation throughout the optimization process [13]. When applied to PID tuning, the PSO-GWO hybrid typically achieves faster convergence, higher solution accuracy, and improved robustness against the multimodal and nonconvex nature of the cost landscape that characterizes strongly nonlinear control problems.

In practical implementation, the population is divided into two cooperative sub-swarms:

- The first sub-swarm updates positions using PSO velocity and position rules, enabling efficient local exploitation.

- The second sub-swarm evolves according to GWO’s hierarchical encircling and hunting behavior, ensuring effective global exploration.

- At each iteration, elite and global best information is exchanged between the sub-swarms to preserve diversity and guide convergence toward the global optimum.

This cooperative structure enhances the robustness and efficiency of the hybrid optimizer, making it particularly suitable for nonlinear and dynamically complex PID controller tuning tasks.

3.4. Complementarity of PSO and GWO

The effectiveness of the hybrid PSO-GWO approach arises from the complementary search behaviors of the two algorithms. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) updates solution candidates through velocity-based dynamics driven by personal and global best information. This mechanism enables rapid exploitation and fine-grained refinement in the neighborhood of promising regions; however, it can lead to loss of population diversity and premature convergence, particularly in highly multimodal or irregular cost landscapes.

Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), in contrast, maintains diversity throughout the search by relying on its hierarchical leadership structure (, , ) and encircling strategy. These mechanisms encourage simultaneous exploration of multiple regions of the search space, providing strong global search capability and reducing the risk of stagnation. Nevertheless, GWO typically converges more slowly during the final phases of the search, where fine-tuning of solutions is required.

By integrating these mechanisms, the hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm assigns the role of global exploration primarily to GWO during the early stages of optimization, while PSO progressively contributes efficient local exploitation as the search narrows toward high-quality regions of the parameter space. This coordinated interaction preserves diversity, prevents premature convergence, and maintains a balanced exploration–exploitation trade-off. As a result, the hybrid approach achieves improved robustness and convergence efficiency when tuning PID controllers for nonlinear dynamical systems.

3.5. Expected Benefits of the Hybrid PSO-GWO Approach

- Complementary Search Dynamics: GWO promotes broad global exploration, while PSO provides rapid and precise local refinement in smooth or well-structured regions of the cost landscape.

- Robustness Against Local Minima: The hybrid structure mitigates premature convergence by combining the memory-driven exploitation of PSO with the stochastic encircling and leadership mechanisms of GWO.

- Enhanced Population Diversity: Exchange of elite and global-best information between the sub-swarms helps maintain diversity and prevents stagnation throughout the optimization process.

- Improved Convergence Efficiency: Hybridization accelerates convergence by allowing PSO to intensify the search around promising areas identified through exploratory behavior of GWO.

- Flexibility for Multi-Objective Tuning: The framework can be readily extended to handle multiple conflicting objectives, such as simultaneously minimizing ITAE and overshoot, without modifying the underlying hybrid structure.

Overall, the PSO-GWO hybrid algorithm capitalizes on the strengths of both metaheuristics, providing faster, more reliable, and globally effective PID tuning for strongly nonlinear control systems. The following section presents its implementation and performance evaluation on representative nonlinear benchmark models.

3.6. General Procedure

The overall PID tuning framework is implemented in Python 3.12, leveraging widely used scientific computing and metaheuristic optimization libraries.

The general procedure for both PSO and GWO consists of the following steps:

- Initialization: Define the search space for PID parameters , generate the initial population (particles or wolves) randomly within these bounds, and initialize historical records for tracking cost evaluations.

- Simulation: For each candidate solution, simulate the second-order nonlinear system using the augmented first-order form of the dynamics, integrating the ODEs with a Runge–Kutta solver (RK45) over the simulation horizon.

- Cost Evaluation: Compute the performance index as the sum of ITAE and ISO terms, storing each evaluation for convergence analysis.

- Position Update:

- In PSO, update particle velocities and positions according to the standard PSO rules, taking into account the inertia, cognitive, and social components.

- In GWO, update the wolf positions using the encircling, hunting, and attacking strategies defined by the leader hierarchy.

- Global Best Update: Identify the best-performing solution across the population (global best) and update personal or elite records as needed.

- Iteration and Convergence Check: Repeat the simulation, evaluation, and update steps for the specified number of generations or until an early stopping criterion is satisfied (e.g., cost improvement below a threshold ).

- Output: The optimal PID parameters , the associated cost , and the total number of cost function evaluations are reported to quantify the performance and computational effort of each optimization strategy.

The hybrid PSO-GWO procedure combines the strengths of both algorithms, exploiting the local refinement capabilities of PSO and the global exploration of GWO through hierarchical hunting. The general workflow is as follows:

- Initialization: Define the search space for PID parameters . Initialize the PSO swarm and GWO population randomly within these bounds. Set personal bests for PSO particles and the leader hierarchy for GWO (). Initialize historical records for cost evaluations.

- Simulation: For each candidate solution (particle or wolf), simulate the second-order nonlinear system in augmented first-order form. Integrate the ODEs over the simulation horizon using a Runge–Kutta solver (RK45) to obtain the system response .

- Cost Evaluation: Compute the performance index as the sum of ITAE and ISO terms. Store each evaluation in a history log for convergence analysis and potential CSV export.

- PSO Update: Update particle velocities and positions using the PSO formulaHere, w is the inertia weight, and are the cognitive and social coefficients, and are independent random numbers uniformly distributed in , and x denotes the current particle position in the search space. Clip positions to remain within bounds. Update personal and global bests as necessary.

- GWO Iteration: Execute a single iteration of GWO for the current population. Evaluate costs, update positions based on encircling and hunting mechanisms guided by leaders , and identify the best GWO solution.

- Hybrid Global Best Update: Compare the global best solution from PSO and the best solution from GWO. Update the PSO global best if the GWO solution is superior.

- Iteration and Convergence Check: Repeat PSO and GWO update steps for the specified number of epochs or until the early stopping criterion is satisfied (e.g., improvement below ).

- Output: Report the optimal PID parameters , the associated cost , the total number of cost function evaluations, and the convergence history.

In practice, the PSO and GWO procedures share the same simulation and cost evaluation structure, differing only in the respective update rules. This uniformity facilitates hybrid strategies, in which subsets of the population are evolved using PSO rules while others follow GWO dynamics, enabling the exchange of global best solutions and complementary search behavior.

The pseudocodes for the PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO-GWO PID tuning procedures are provided in Appendix A, Appendix B, and Appendix C, respectively.

4. Benchmark Nonlinear Systems and Simulation Results

4.1. Benchmark Nonlinear Systems

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed PID tuning strategies, we consider three representative second-order nonlinear systems. Each system is expressed in the standard form

where is the system output, is the control input, and encodes the system-specific nonlinear dynamics. The three benchmark systems considered in this study are as follows:

- System 1: Pendulum-like nonlinear systemwith parameters , . This system exhibits moderate nonlinearity and resembles the dynamics of a simple pendulum with damping (for ). It is suitable for testing the convergence and robustness of PID tuning algorithms.

- System 2: Duffing oscillatorwith parameters , , . This system is commonly used to test control strategies for stiff and highly nonlinear systems due to the cubic stiffness term, which can produce multiple equilibria and nonlinear oscillatory behavior.

- System 3: Nonlinear damping systemwith parameters , , . This system introduces a velocity-dependent nonlinear damping term , creating asymmetric transient responses and testing the adaptability of metaheuristic PID tuning.

These three benchmark systems collectively cover a range of nonlinear behaviors, including oscillatory, stiff, and asymmetric dynamics. They provide a meaningful testbed for comparing the performance of PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO-GWO-based PID tuning strategies. The selection of additional systems may be performed in subsequent studies to further explore algorithmic robustness and generalizability.

4.2. PSO Parameters

The PSO algorithm is implemented using the pyswarm package with a swarm of particles, each representing a candidate set of PID parameters . Particle velocities are updated using an inertia weight and cognitive and social acceleration coefficients . The maximum number of iterations is set to 50 to ensure sufficient exploration while keeping the computational cost reasonable as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

PSO parameters used in simulations.

4.3. GWO Parameters

For GWO, we use the OriginalGWO class from mealpy-3.0.3 with a population of wolves representing candidate PID parameters . The algorithm follows the standard hunting and encircling strategies, keeping the alpha, beta, and delta leadership weights at their default values (). The maximum number of epochs is set to 50 to ensure convergence while maintaining a computational cost comparable to PSO as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

GWO parameters used in simulations.

4.4. Hybrid PSO-GWO Parameters

For the hybrid PSO-GWO strategy, the same population size and algorithmic parameters are used as in the standalone PSO and GWO cases. However, the population is explicitly divided into two equal sub-swarms: 15 particles evolve according to PSO update rules, while the other 15, acting as wolves, follow the GWO dynamics. At each iteration, global best information and elite solutions are exchanged between the sub-swarms to exploit complementary search behaviors. This setup allows the hybrid approach to leverage both the exploration capability of GWO and the fast convergence of PSO, while maintaining the same total computational budget as the standalone algorithms.

For all simulations, unless stated otherwise, the cost function in (9) employs a weighting factor , assigning equal importance to the ITAE and ISO components. During each optimization run, we record and visualize the following outputs: the time-domain response of the controlled system , the evolution of the cost function values corresponding to candidate PID parameter sets , the minimal achieved cost function value, and the total number of cost function evaluations required to reach the optimum. Additionally, an early stopping criterion is enforced: if two consecutive cost function values differ by less than , the optimization is terminated to prevent unnecessary computations while ensuring convergence.

4.5. Closed-Loop Response Under PSO, GWO, and Hybrid PSO-GWO PID Control

In this section, we present the results of the closed-loop simulations for the three benchmark nonlinear systems introduced in Section 4.1. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO-GWO PID tuning strategies in regulating second-order nonlinear systems. For each system, we provide graphical illustrations of the system output under the optimized PID parameters, the evolution of the cost function during optimization, and the trajectories of the PID gains as they converge to their optimal values. The achieved minimum of the cost function and the total number of function evaluations required to reach this optimum are reported, along with any early stopping criteria that were triggered. Early stopping is applied when the absolute difference between two consecutive cost function evaluations falls below . This ensures computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy in identifying the optimal PID parameters.

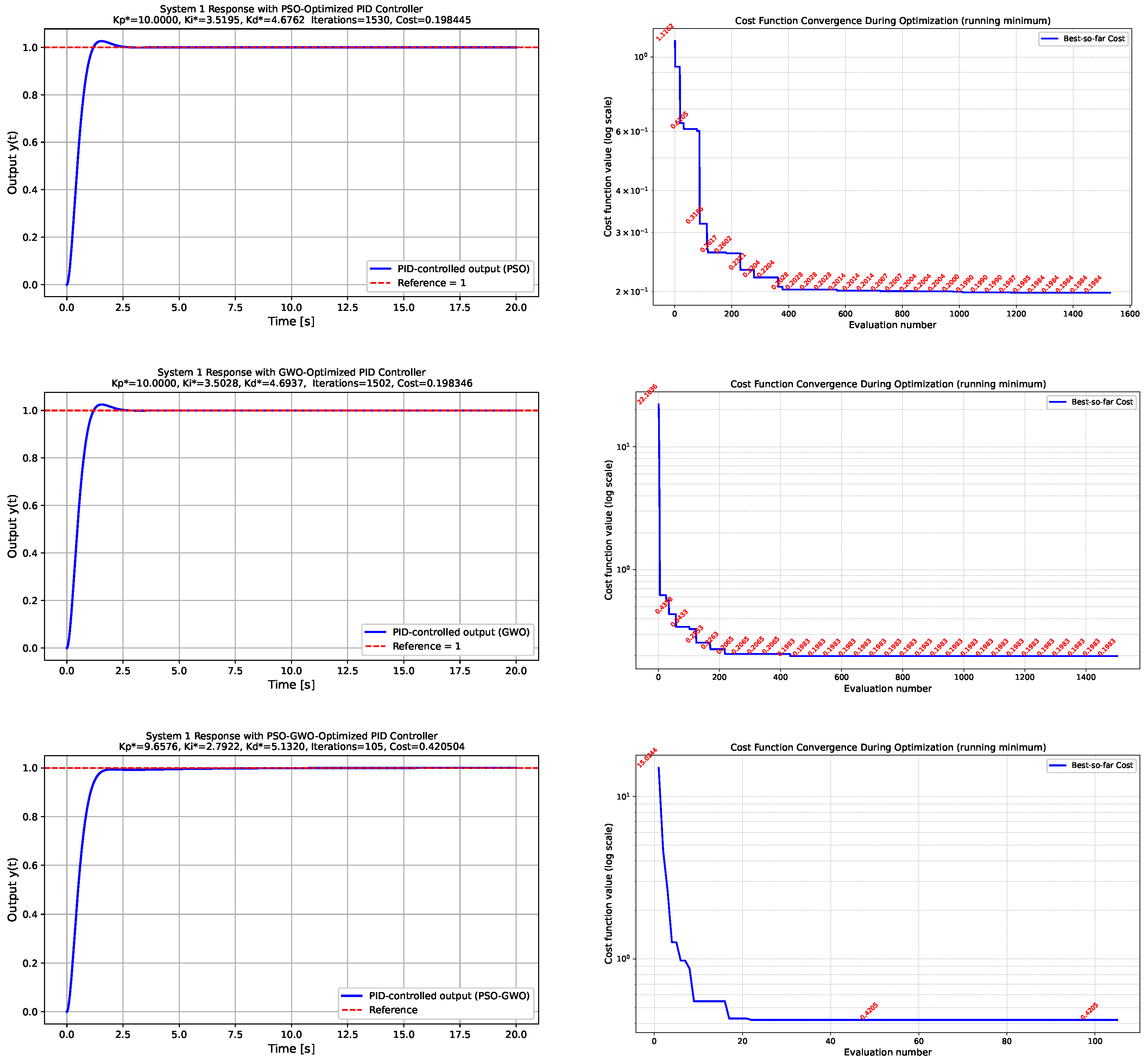

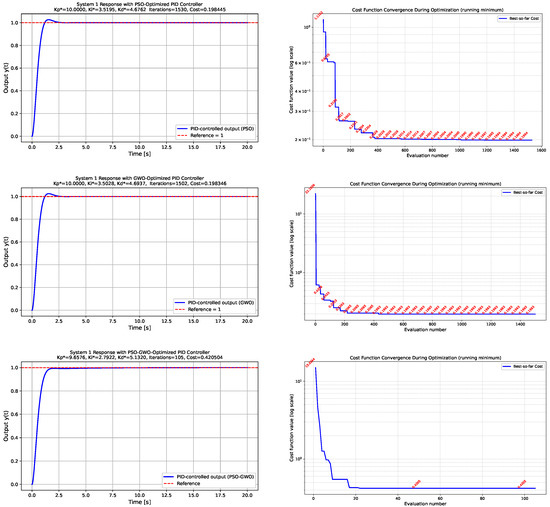

- System 1: Pendulum-like nonlinear systemFigure 2 presents the simulation results obtained for the pendulum-like nonlinear system. The figure is organized into three rows and two columns. The left column illustrates the closed-loop time responses to a unit-step reference input under the PID gains optimized by the PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO–GWO algorithms, respectively. All three metaheuristic methods successfully stabilize the nonlinear system, while the hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm demonstrates faster convergence and a reduced overshoot compared to the individual approaches. The right column of Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of the cost function over successive evaluations, providing insight into the convergence behavior of each optimization strategy. For each case, the achieved minimum cost and the number of evaluations required to reach it are depicted graphically.

Figure 2. System 1—Pendulum-like nonlinear system. Comparison of the system responses and convergence profiles for different optimization algorithms. The left column shows the closed-loop responses of the pendulum-like nonlinear system under PSO-, GWO-, and hybrid PSO-GWO-optimized PID gains, while the right column depicts the evolution of the cost function during the optimization process. Minimum cost values and the corresponding number of evaluations are indicated.

Figure 2. System 1—Pendulum-like nonlinear system. Comparison of the system responses and convergence profiles for different optimization algorithms. The left column shows the closed-loop responses of the pendulum-like nonlinear system under PSO-, GWO-, and hybrid PSO-GWO-optimized PID gains, while the right column depicts the evolution of the cost function during the optimization process. Minimum cost values and the corresponding number of evaluations are indicated.

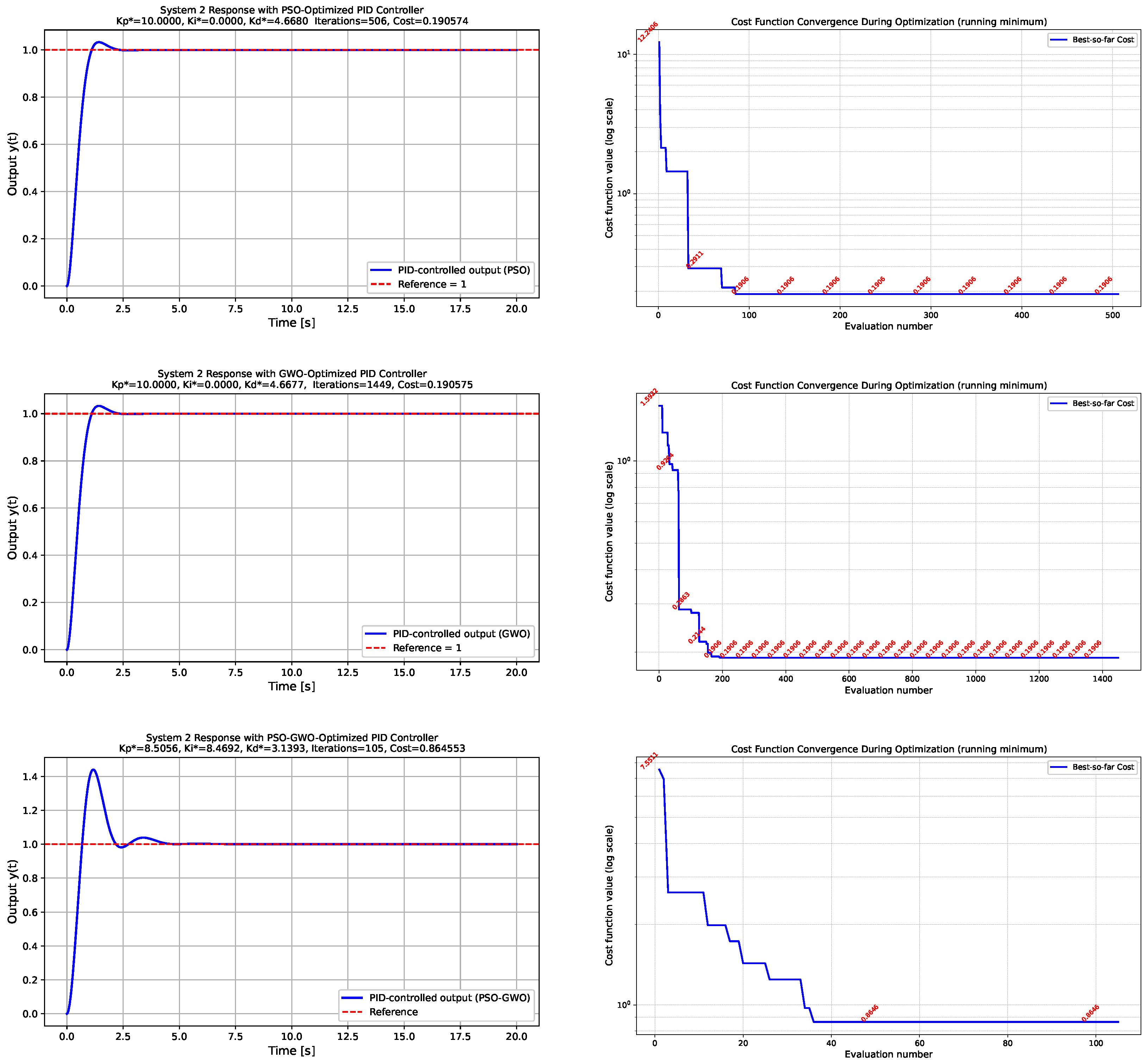

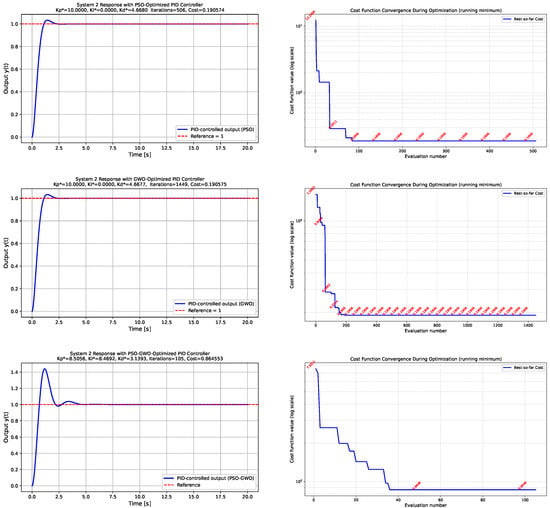

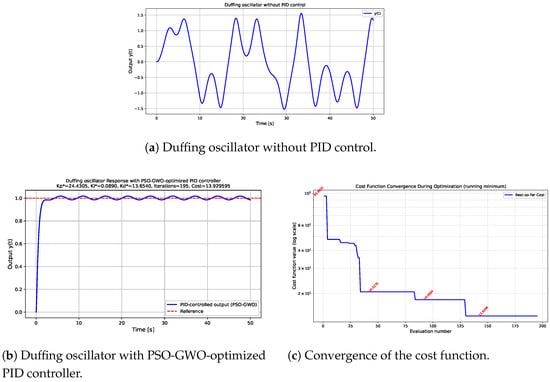

- System 2: Duffing oscillatorThe response of the Duffing oscillator is presented in Figure 3. Due to the presence of the cubic stiffness term, the system exhibits pronounced nonlinear and potentially oscillatory behavior. The left column of Figure 3 displays the time-domain responses of obtained using PID gains optimized by the PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO-GWO algorithms. All three controllers are able to regulate the system effectively; however, the hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm produces a noticeably higher overshoot compared to PSO and GWO. This behavior can be mitigated by increasing the weight of the ISO term in the performance function. For instance, when , a significant suppression of overshoot is observed as illustrated in the first row of Figure 4. The right column of Figure 3 provides insights into the convergence of the cost function across iterations.

Figure 3. System 2—Duffing oscillator. Comparison of the Duffing oscillator responses and optimization progress for different metaheuristic strategies. The left column illustrates the closed-loop behavior of the nonlinear oscillator, whereas the right column presents the evolution of the cost function, highlighting convergence differences among PSO, GWO, and the hybrid PSO-GWO approach. Minimum cost and evaluation count are annotated in the plots.

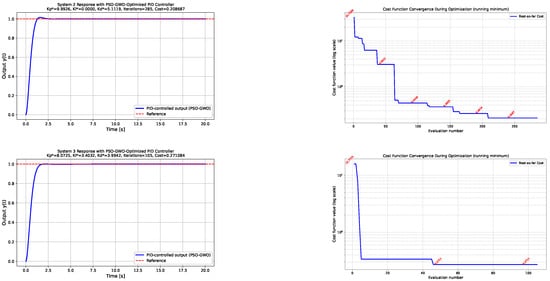

Figure 3. System 2—Duffing oscillator. Comparison of the Duffing oscillator responses and optimization progress for different metaheuristic strategies. The left column illustrates the closed-loop behavior of the nonlinear oscillator, whereas the right column presents the evolution of the cost function, highlighting convergence differences among PSO, GWO, and the hybrid PSO-GWO approach. Minimum cost and evaluation count are annotated in the plots. Figure 4. Hybrid PSO-GWO simulations for the Duffing and nonlinear damping systems with . The plots demonstrate the effect of increasing the weighting coefficient in the ISO term of the performance index. Compared to the previous simulations with , a substantial reduction in overshoot is observed, indicating improved damping and smoother transient behavior. This adjustment effectively mitigates the excessive aggressiveness of the hybrid optimizer observed in earlier cases.

Figure 4. Hybrid PSO-GWO simulations for the Duffing and nonlinear damping systems with . The plots demonstrate the effect of increasing the weighting coefficient in the ISO term of the performance index. Compared to the previous simulations with , a substantial reduction in overshoot is observed, indicating improved damping and smoother transient behavior. This adjustment effectively mitigates the excessive aggressiveness of the hybrid optimizer observed in earlier cases.

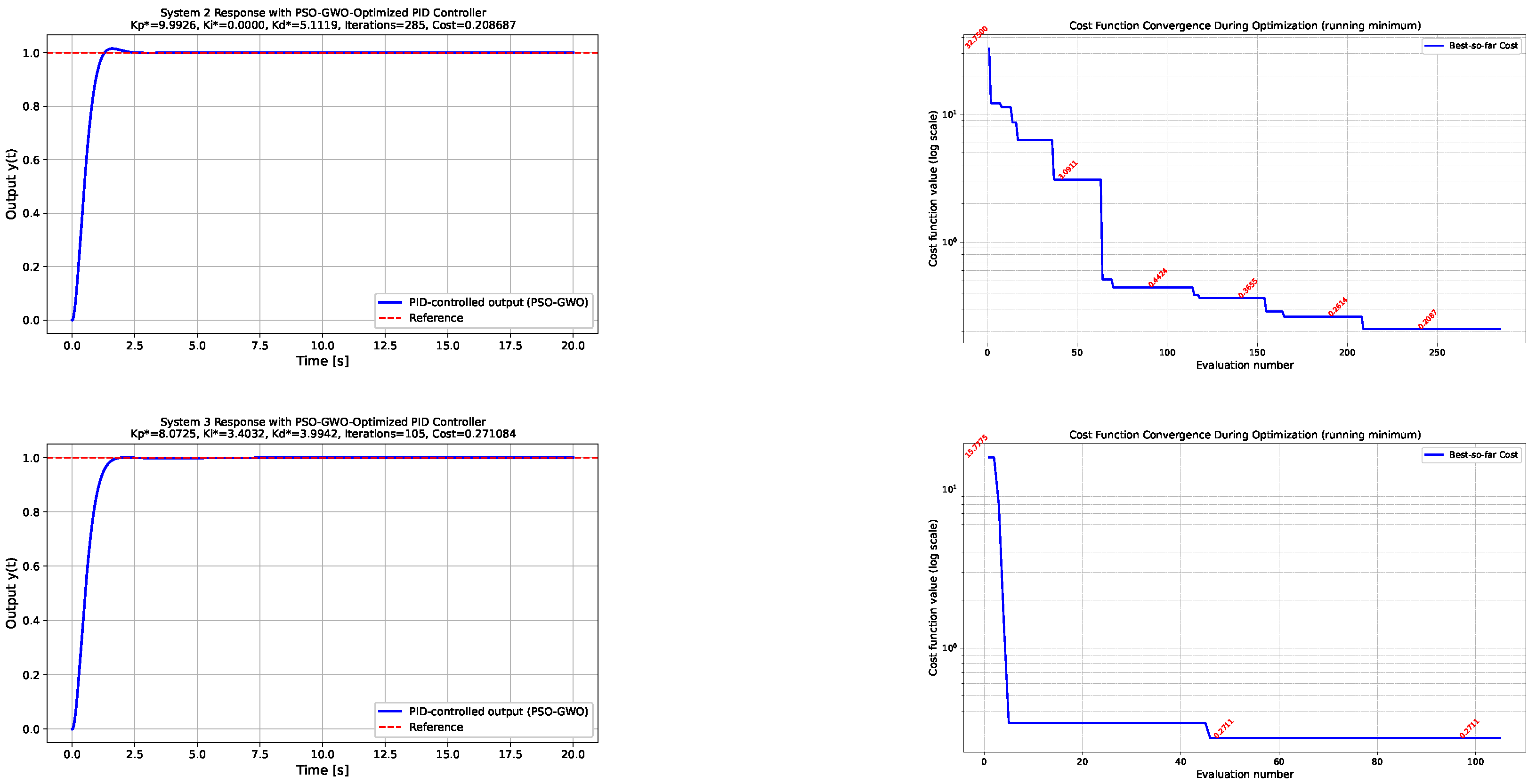

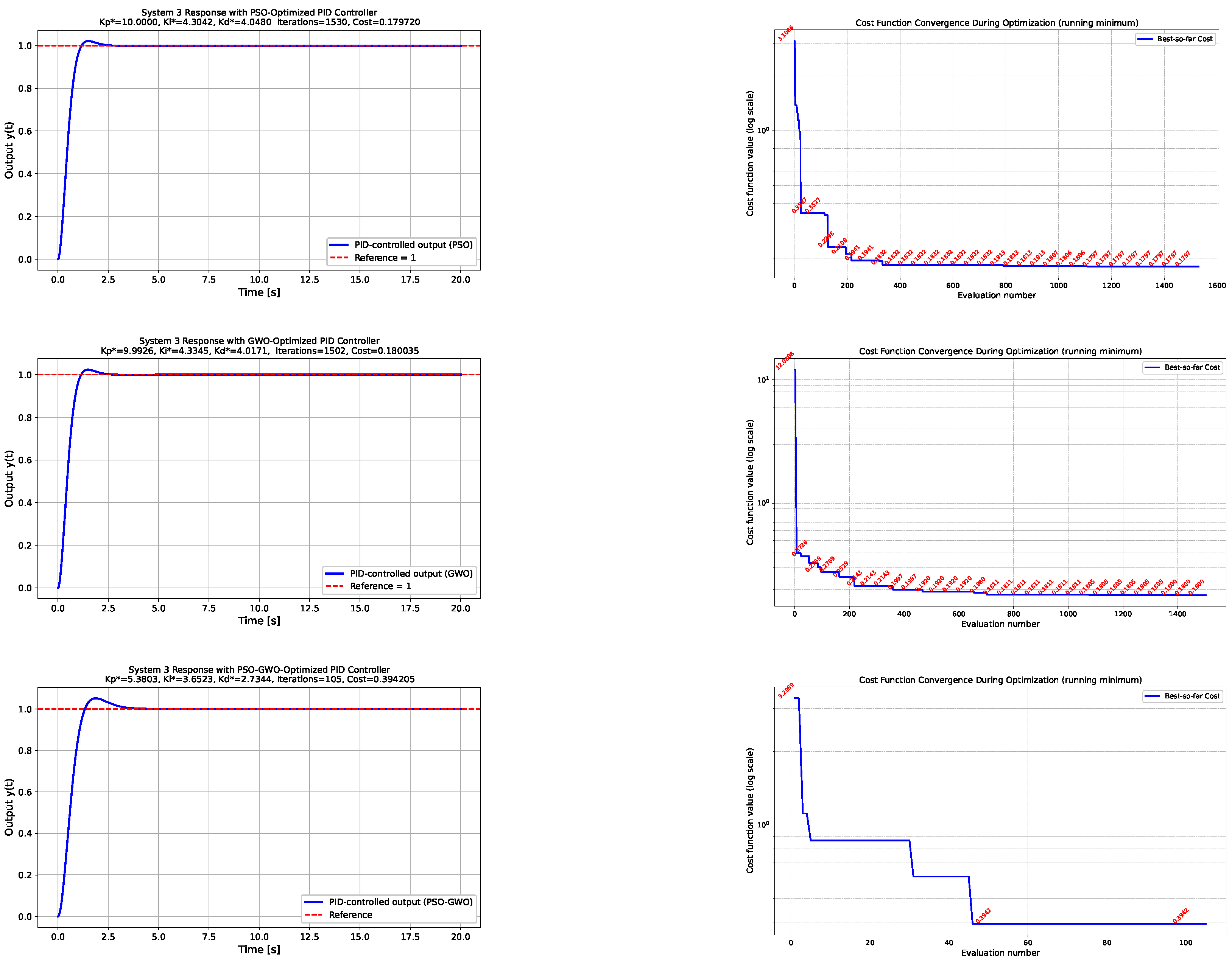

- System 3: Nonlinear damping systemFigure 5 illustrates the closed-loop behavior of the nonlinear damping system for the PID controllers optimized by PSO, GWO, and the hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm. The left column shows the system responses to a unit-step input. The presence of the velocity-dependent damping term introduces asymmetric transient dynamics and nonlinear dissipation effects. All optimized PID controllers are capable of stabilizing the system; however, the hybrid PSO-GWO approach again exhibits a relatively higher overshoot compared to the standalone PSO and GWO methods. Nevertheless, this increased transient excitation occurs at a substantially lower number of cost function evaluations, indicating a more efficient search process. As in the case of the Duffing oscillator, this overshoot can be mitigated by appropriately increasing the weighting coefficient of the ISO component in the performance index as can be observed in the second row of Figure 4, thereby emphasizing steady-state accuracy. The right column of Figure 5 depicts the evolution of the cost function during the optimization process, further highlighting the convergence characteristics and trade-offs in exploration and exploitation among the three algorithms.

Figure 5. System 3—Nonlinear damping system. Comparison of the nonlinear damping system responses and cost evolution across optimization algorithms. The left column displays the system output trajectories obtained using PID parameters tuned via PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO-GWO, while the right column shows the convergence of the cost function. It should be noted that although the hybrid PSO-GWO requires significantly fewer cost evaluations, its resulting PID gains may produce a more conservative transient response, leading to a slightly longer settling time. This behavior reflects the balance enforced by the performance index rather than computational speed, and can be modified by increasing the ISO weighting factor .

Figure 5. System 3—Nonlinear damping system. Comparison of the nonlinear damping system responses and cost evolution across optimization algorithms. The left column displays the system output trajectories obtained using PID parameters tuned via PSO, GWO, and hybrid PSO-GWO, while the right column shows the convergence of the cost function. It should be noted that although the hybrid PSO-GWO requires significantly fewer cost evaluations, its resulting PID gains may produce a more conservative transient response, leading to a slightly longer settling time. This behavior reflects the balance enforced by the performance index rather than computational speed, and can be modified by increasing the ISO weighting factor .

It should be noted that the convergence graph of the cost function for the PSO-based PID tuning of System 1 (as well as for some other systems and algorithms) exhibits extreme values during the initial evaluations. These large cost values result from the transient numerical instabilities caused by certain initial combinations of PID parameters that produce high initial errors.

To present the tuning process more clearly, only the running minimum of the cost function (the “best-so-far” value) is plotted, which effectively illustrates the progressive improvement of the PID parameters over successive evaluations. Selected cost values are annotated at specific intervals to provide quantitative insight while avoiding visual clutter in the figure.

This approach ensures that the graphical representation accurately reflects the optimization dynamics without being distorted by transiently unstable simulations.

5. Discussion

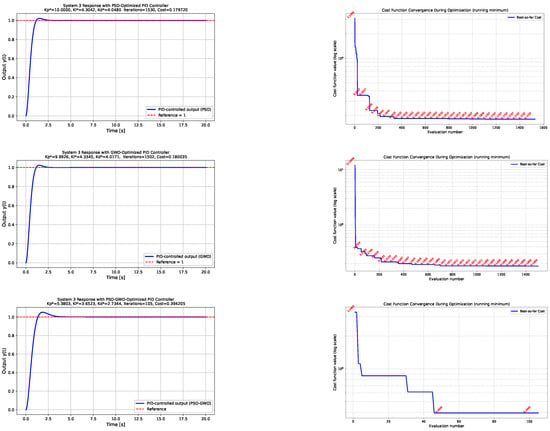

For a better comparison and quantitative evaluation of the obtained results, the key performance metrics and optimal PID parameters are summarized in Table 3. This table consolidates the outcomes for all three nonlinear benchmark systems and provides insights into the convergence efficiency and stability characteristics of the tested optimization methods.

Table 3.

Summary of optimal PID parameters and performance metrics for Systems 1–3.

- Computational efficiency: The hybrid PSO-GWO algorithm achieves the target cost values with a substantially smaller number of cost function evaluations—approximately 10% of those required by standalone PSO or GWO. This remarkable reduction can be attributed to the synergy between the exploration capability of GWO and the exploitation behavior of PSO, which enables faster convergence toward promising regions of the search space. The hybrid structure effectively combines global and local search mechanisms, resulting in a rapid decrease in the cost function even in highly nonlinear conditions.

- System performance and overshoot behavior: Although the hybrid PSO-GWO demonstrates excellent convergence speed, its time-domain responses for Systems 2 and 3 exhibit pronounced overshoot and oscillations during the transient phase. This behavior suggests that the algorithm tends to generate aggressive control actions due to a strong emphasis on the integral and derivative gains during the optimization process. The observed overshoot can be mitigated by increasing the weighting factor in the ISO term of the performance function. Numerical experiments show that setting effectively suppresses overshoot without significantly affecting the total number of cost function evaluations, indicating a favorable trade-off between control smoothness and optimization efficiency.

- Comparison of PSO and GWO: Both standalone PSO and GWO algorithms achieve stable control performance with low cost values, though at the expense of considerably higher computational effort. GWO, in particular, exhibits consistent but slower convergence, reflecting its exploratory nature. PSO maintains fast convergence and strong exploitation of promising regions but requires more evaluations to achieve comparable performance to the hybrid approach.

- Sensitivity to the performance index parameters: The results further confirm that the design of the performance function, particularly the weighting of its integral and overshoot (ISO) components, plays a critical role in shaping controller behavior. For the hybrid PSO-GWO, an insufficiently penalized overshoot term (small ) leads to aggressive transient responses, whereas larger values produce smoother trajectories without degrading the convergence rate. Hence, the parameterization of the performance function directly governs the trade-off between control aggressiveness and robustness.

In summary, the hybrid PSO–GWO framework demonstrates notable computational efficiency while maintaining satisfactory control accuracy across the considered nonlinear systems. However, the observed overshoot behavior indicates that careful tuning of the ISO weight is necessary to balance convergence speed with acceptable transient performance. These findings suggest that hybrid swarm-based metaheuristics offer a practical approach for real-time PID tuning, provided that the cost function formulation appropriately reflects the desired control objectives.

5.1. Practical Considerations and Mitigation of Common Risks in Metaheuristic PID Tuning

Metaheuristic PID tuning methods are known to exhibit several practical limitations, including potentially long optimization time, sensitivity to random initialization, and the possibility of generating unsafe or destabilizing controller parameters during the search process. In the present study, several measures were incorporated to mitigate these risks.

First, the search space for the PID gains is explicitly bounded to a compact and physically meaningful region, preventing the optimizer from exploring extreme values of that could destabilize the closed loop. Any candidate solution that produces divergent or numerically unstable trajectories is automatically assigned a large penalty value in the cost function, ensuring that unstable behavior is avoided.

Second, the hybrid PSO-GWO method substantially reduces the number of cost function evaluations—typically to less than 10% of the evaluations required by standalone PSO or GWO—thus alleviating concerns about the long optimization time. This improvement results from the complementary interaction between the exploitation capability of PSO and the population diversity and global exploration of GWO.

Third, both PSO and GWO require only a small number of intuitive hyperparameters, which helps limit algorithmic complexity. Sensitivity to initialization is further mitigated by maintaining population diversity (through GWO mechanisms) and by employing an early stopping criterion that rejects stagnating or unproductive search trajectories.

Overall, the adopted hybrid strategy improves robustness, reduces sensitivity to random initialization, and ensures safe exploration of the parameter space, making it suitable for nonlinear PID tuning tasks.

5.2. Remark on Stochastic Variability of Optimization Results

During the simulation campaign, repeated runs of the same optimization algorithm—PSO, GWO, or the hybrid PSO-GWO—often converge to slightly different sets of controller parameters, even under identical initialization and stopping criteria (maximum iteration count and tolerance of ). This variability arises from the stochastic nature of metaheuristic search, where random initialization and probabilistic update rules inherently influence the optimization trajectory.

In complex, nonlinear, and multimodal cost landscapes—such as those from chaotic dynamical systems—numerous local minima of comparable depth may exist. As a result, different runs can converge to distinct, yet nearly equivalent, optima that yield similar performance indices while corresponding to different PID parameter combinations. Such differences do not indicate algorithmic instability but rather reflect the multiplicity of acceptable solutions in a rugged landscape. For presentation, representative responses from the most frequently observed convergence patterns were selected.

This phenomenon is common in stochastic metaheuristics. Due to their inherent randomness, independent runs may converge to different local or quasi-global minima even under identical stopping criteria. The stochastic variability of these algorithms is well-documented [20,21], highlighting the importance of multiple independent runs and reporting statistical performance metrics to ensure fair and reproducible comparisons.

In the following subsection, the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed PSO-GWO-based PID tuning framework are rigorously evaluated on one of the most challenging nonlinear dynamic benchmarks—the chaotic Duffing oscillator.

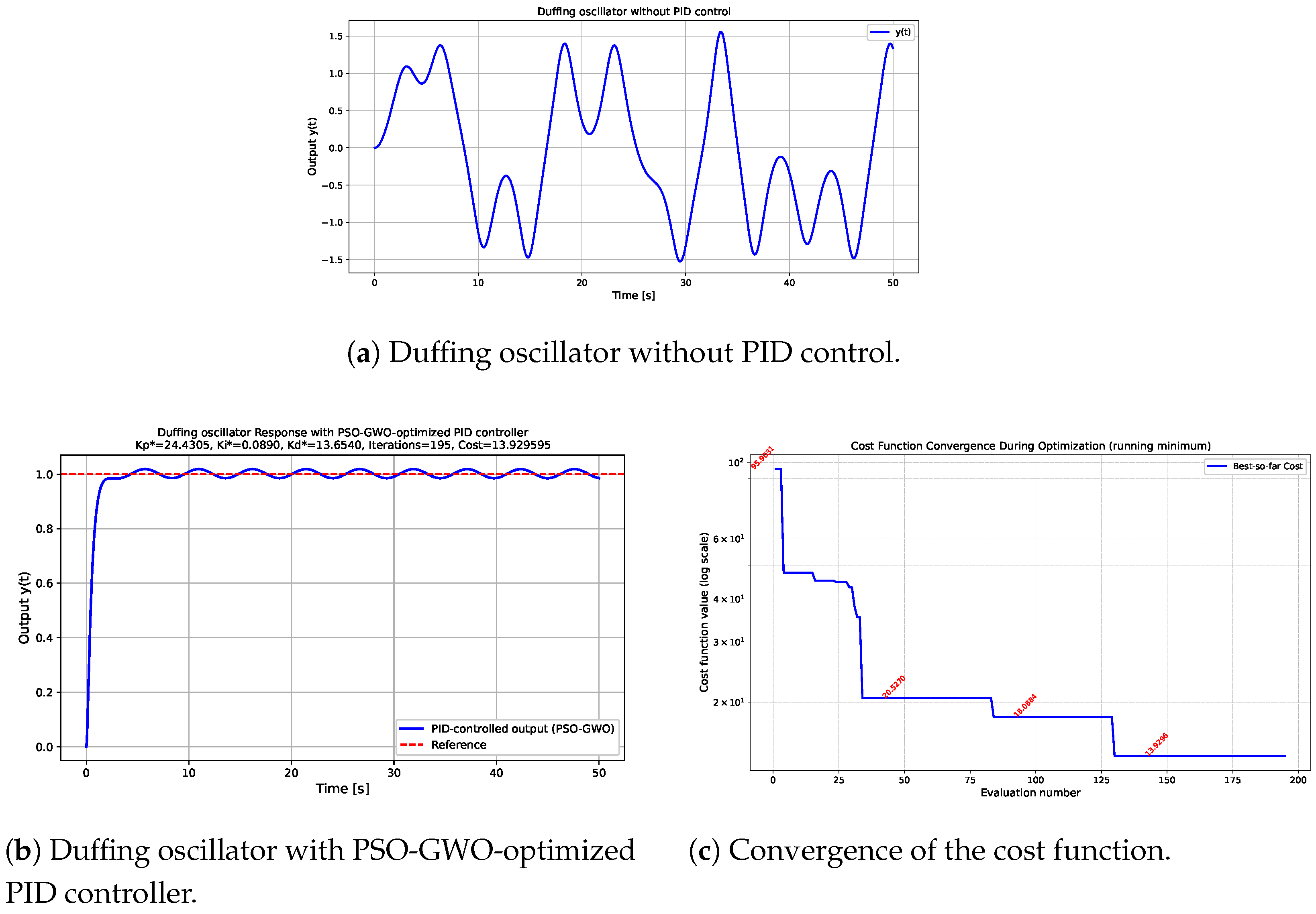

5.3. Robustness Test on the Chaotic Duffing Oscillator

The Duffing oscillator represents one of the most challenging nonlinear dynamical systems to control due to its strong nonlinearity, sensitivity to initial conditions, and the presence of chaotic behavior under certain parameter regimes. Its dynamics can be described by the nonlinear second-order differential equation:

where denotes the damping coefficient, and are the linear and nonlinear stiffness parameters, represents the amplitude of the external forcing, is its excitation frequency, and is the control input generated by the PID controller.

For the selected parameter set , , , , and , the uncontrolled system () exhibits aperiodic oscillations and extreme sensitivity to small perturbations—hallmarks of chaotic behavior. Such characteristics render conventional linear control strategies largely ineffective, as even minor variations in the control signal or in the system state may lead to significantly different trajectories. Consequently, the chaotic Duffing oscillator is frequently employed as a benchmark for evaluating the robustness, adaptability, and convergence properties of advanced control and optimization algorithms, particularly in the context of nonlinear and chaotic dynamics.

Figure 6 illustrates the contrasting responses of the Duffing oscillator without and with PID control, assuming zero initial conditions for the oscillator, and . In the absence of control, the system exhibits irregular, chaotic oscillations that fail to settle to any equilibrium, demonstrating its highly unstable and unpredictable nature. In contrast, when the PID controller is tuned using the proposed hybrid PSO-GWO optimization method, the chaotic oscillations are effectively suppressed, and the system exhibits smooth, near-periodic behavior. Although small oscillations remain due to the periodic excitation term , the overall motion is significantly stabilized and follows the desired reference trajectory. This demonstrates the hybrid algorithm’s ability to handle strong nonlinearities and nonstationary dynamics, confirming both its robustness and adaptability in one of the most demanding nonlinear control scenarios.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the Duffing oscillator time responses: uncontrolled chaotic behavior (a) versus stabilized dynamics achieved by the proposed PSO-GWO-based PID tuning (b). The hybrid controller effectively suppresses chaotic oscillations and enforces smoother convergence toward the reference trajectory. For the PID tuning, the search space for the controller parameters is , and the weighting coefficient in the cost function (9) is set to .

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a hybrid PSO–GWO framework for optimal PID tuning in nonlinear dynamical systems. The method combines the exploitative capabilities of Particle Swarm Optimization with the strong exploratory behavior of the grey wolf optimizer, resulting in a balanced search strategy capable of handling nonconvex and multimodal cost landscapes.

The proposed algorithm was evaluated on three distinct nonlinear benchmark systems, demonstrating consistent improvements in transient behavior, reduced cost function values, and efficient convergence compared with standalone PSO and GWO approaches. In particular, the hybrid optimizer yielded more accurate parameter estimates with significantly fewer cost function evaluations, highlighting its suitability for computationally demanding or real-time tuning scenarios.

To provide a concise visual summary of the main ideas and outcomes, Figure 7 presents an integrated illustration of the motivation, control structure, and performance improvement achieved by the PSO-GWO-optimized PID controller. This summary figure highlights the progression from uncontrolled nonlinear dynamics to stabilized behavior under optimized feedback control.

Figure 7.

Summary illustration of the proposed hybrid PSO-GWO framework for optimal PID tuning in nonlinear dynamical systems. The diagram highlights the motivation, the control architecture, and the resulting improvement from uncontrolled to stabilized Duffing oscillator dynamics. The reference signal is a unit-step input used for evaluating the closed-loop performance.

Overall, the results confirm that hybrid metaheuristic tuning represents a powerful and flexible approach for nonlinear PID design, offering improved robustness, reliable convergence, and strong performance across diverse nonlinear vibration suppression tasks. Future work will focus on extending the method to adaptive and model-based predictive control architectures, as well as validating the algorithm experimentally on physical test platforms.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 1/0318/25).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive comments, which significantly contributed to improving the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. PID Tuning of Second-Order Nonlinear Systems Using PSO

| Algorithm A1 PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using PSO. |

|

Appendix B. PID Tuning of Second-Order Nonlinear Systems Using GWO

| Algorithm A2 PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using GWO. |

|

Appendix C. PID Tuning of Second-ORDER Nonlinear Systems Using Hybrid PSO-GWO

| Algorithm A3 PID tuning of second-order nonlinear systems using Hybrid PSO-GWO. |

|

References

- Åström, K.J.; Hägglund, T. Advanced PID Control; ISA—The Instrumentation, Systems, and Automation Society: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nise, N.S. Control Systems Engineering, 6th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering, 5th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, D.; Khosravi, N.; Khan, M.A.; Waseem, M.; Ahmed, H. Advancements in nonlinear PID controllers: A comprehensive review. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2026, 129, 110775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Huang, J.; Mohammed, S. Load-Transfer Suspended Backpack With Bioinspired Vibration Isolation for Shoulder Pressure Reduction Across Diverse Terrains. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 3059–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Wang, H.; Shang, D.; Li, M.; Xu, T. Disturbance Compensation Control for Humanoid Robot Hand Driven by Tendon–Sheath Based on Disturbance Observer. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 13387–13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.-Q. Neuro-Fuzzy Musculoskeletal Model-Driven Assist-as-Needed Control via Impedance Regulation for Rehabilitation Robots. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 33, 4277–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.A.; Fiers, P.; Sheets-Singer, A.L.; Collins, S.H. Improving the Energy Economy of Human Running With Powered and Unpowered Ankle Exoskeleton Assistance. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eaay9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prity, F.S. Nature-inspired optimization algorithms for enhanced load balancing in cloud computing: A comprehensive review with taxonomy, comparative analysis, and future trends. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 97, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, R.C.; Kennedy, J. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R.C. A discrete binary version of the particle swarm algorithm. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–15 October 1997; Volume 5, pp. 4104–4108. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R.C. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–9 May 1998; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, G. Grey Wolf Particle Swarm Optimized Pump–Motor Servo System Constant Speed Control Strategy. Machines 2023, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, P.; Garza-Castañón, L.E.; Minchala-Avila, L.I.; Vargas-Martínez, A.; Puig Cayuela, V.; Payeur, P. Robust Nonlinear Trajectory Controllers for a Single-Rotor UAV with Particle Swarm Optimization Tuning. Machines 2023, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.; Cortes, D.; Ramirez-Salinas, M.A.; Villa-Vargas, L.A.; Lopez, A. Random Exploration and Attraction of the Best in Swarm Intelligence Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambou, M.C.Z.; Kammogne, A.S.T.; Siewe, M.S.; Azar, A.T.; Ahmed, S.; Hameed, I.A. Optimized Nonlinear PID Control for Maximum Power Point Tracking in PV Systems Using Particle Swarm Optimization. Math. Comput. Appl. 2024, 29, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Solaiman, O.S.; Sihwail, R.; Shehadeh, H.; Hashim, I.; Alieyan, K. Hybrid Newton–Sperm Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Nonlinear Systems. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, L. Particle Swarm Optimization-Enhanced Fuzzy Control for Electrical Conductivity Regulation in Integrated Water–Fertilizer Irrigation Systems. Automation 2025, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillen, W.; Lombaert, G.; Schevenels, M. Performance assessment of metaheuristic algorithms for structural optimization taking into account the influence of algorithmic control parameters. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 618851. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, A.A.; Keenan, P.; Martí, R.; McGarraghy, S.; Panadero, J.; Carro, P.; Oliva, D. A review of the role of heuristics in stochastic optimisation: From metaheuristics to learnheuristics. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 320, 831–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).