A Novel H∞/H2 Pole Placement LFC Controller with Measured Disturbance Feedforward Action for Disturbed Interconnected Power Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Conventional Control Techniques:

- Intelligent Control Methods:

- Optimization-Based Approaches:

- Renewable Energy Integration:

- Multi-Area and Decentralized Control:

- Hybrid and Advanced Control Techniques:

- Cybersecurity in LFC:

- Emerging Technologies and Applications:

1.1. Centralized vs. Decentralized Controllers

1.2. Identifying the Specific Gap

1.3. Novel Contribution

- Robust Stability (H∞): Against uncertainties in turbine, governor, and grid parameters.

- Optimal Energy Minimization (H2): Substantial reductions in actuator energy, fuel consumption, and overall operational cost.

- Superior Transient Performance (Pole Placement): Direct control over settling time and overshoot of the ACE.

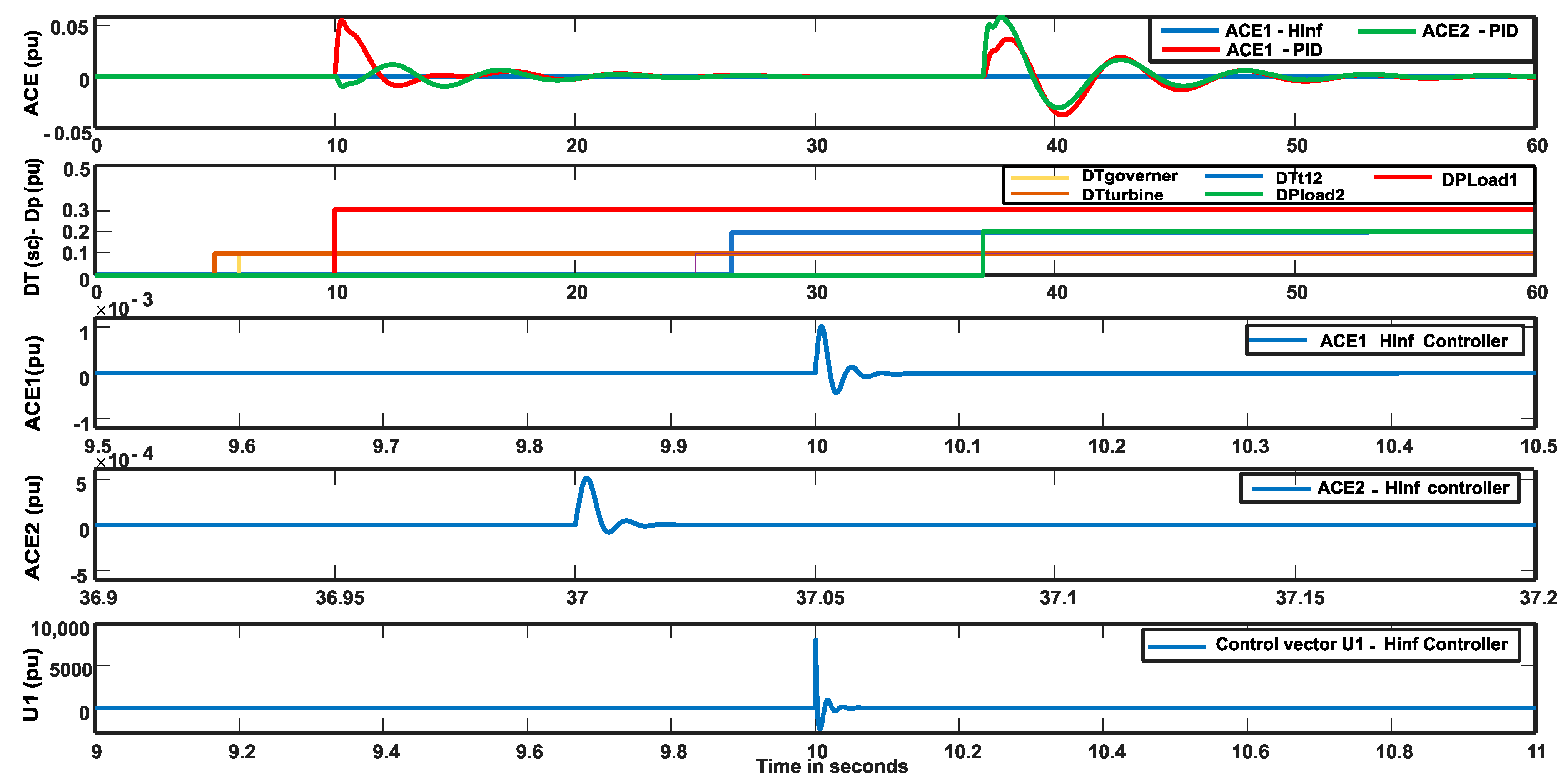

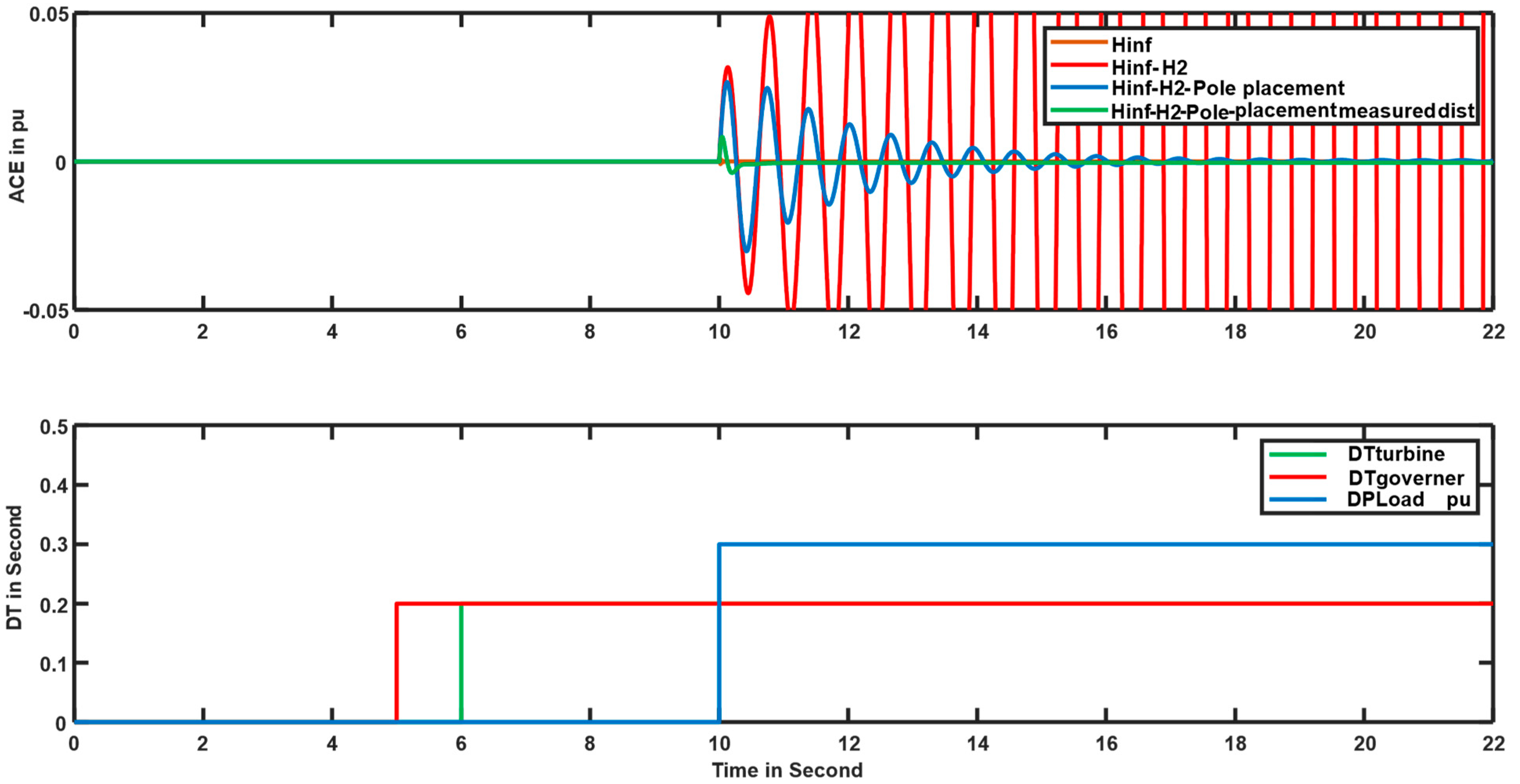

1.4. Validation and Demonstrated Superiority

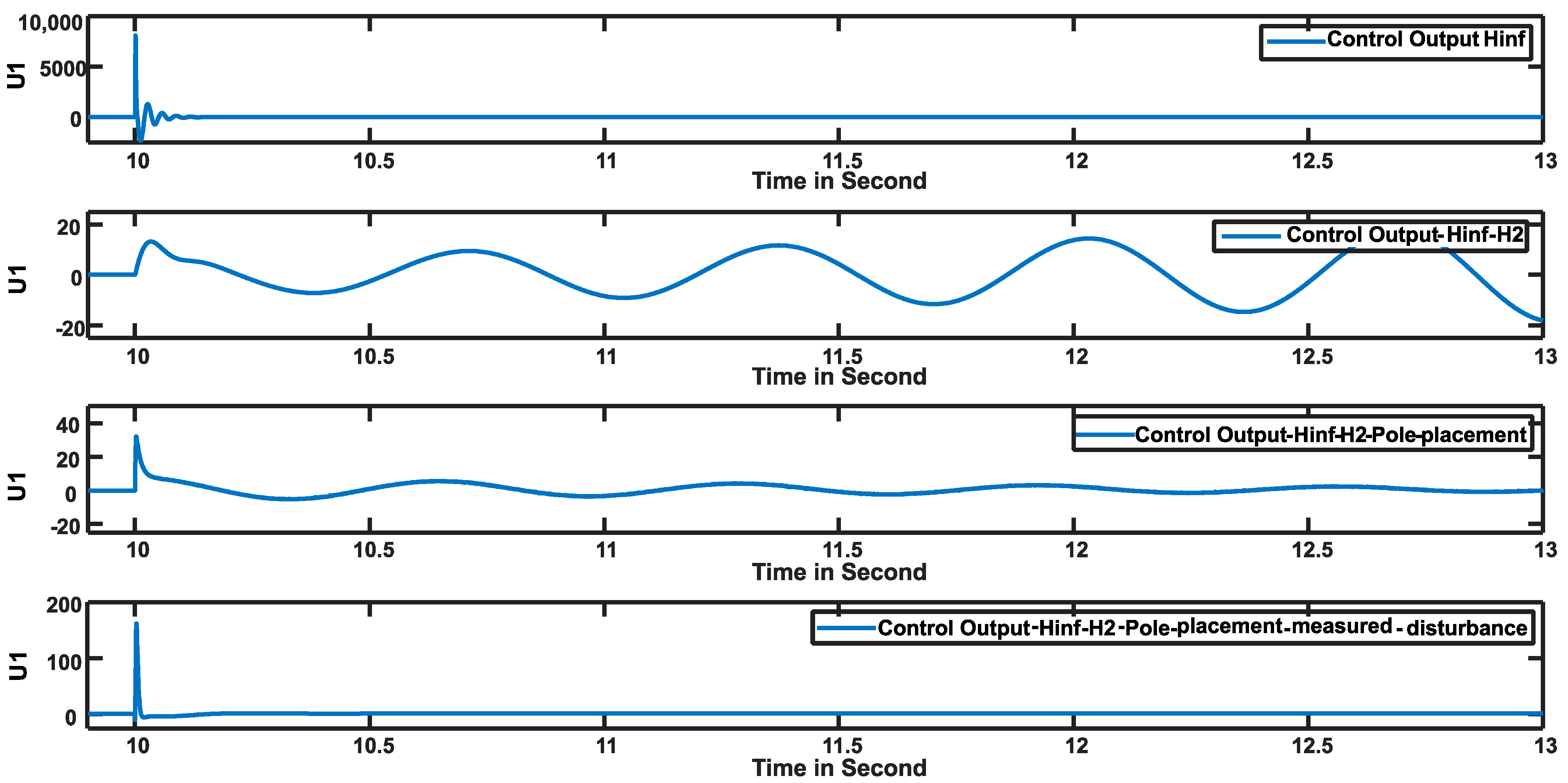

- Standard H∞/H2: Becomes unstable under severe uncertainties.

- H∞/H2/Pole Placement: Remains stable but suffers from a long settling time (~7 s) and high peak values.

- Proposed H∞/H2/Pole Placement with Measured Disturbance: Demonstrates clear superiority.

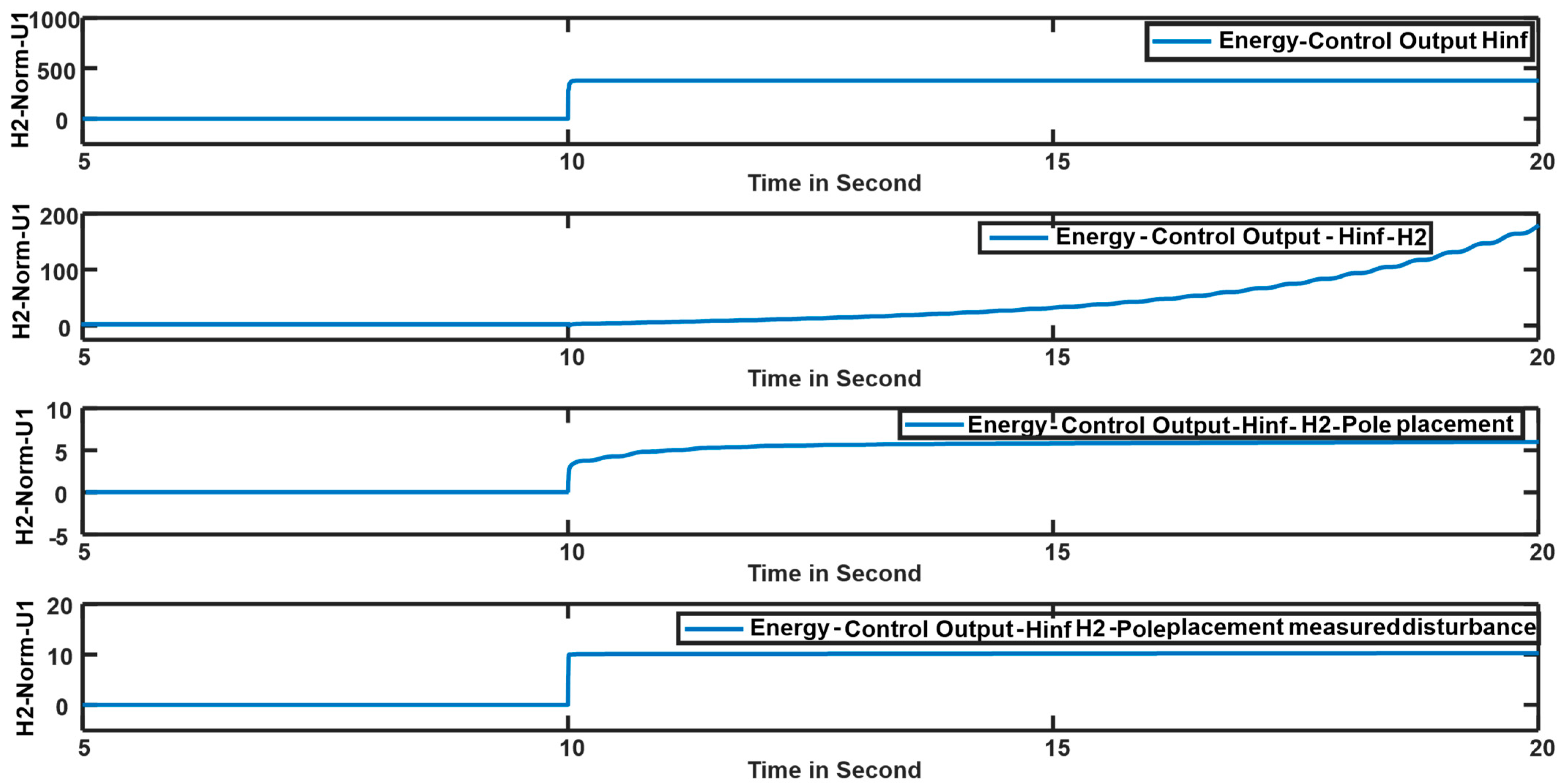

- 98% reduction in actuator energy consumption compared to the standard H∞ controller.

- 98% reduction in the peak value of the control signal.

- 70% reduction in overshoot and a drastically shortened settling time from 7 s to 0.2 s.

1.5. Scope of Work and Assumptions

1.6. Paper Organization

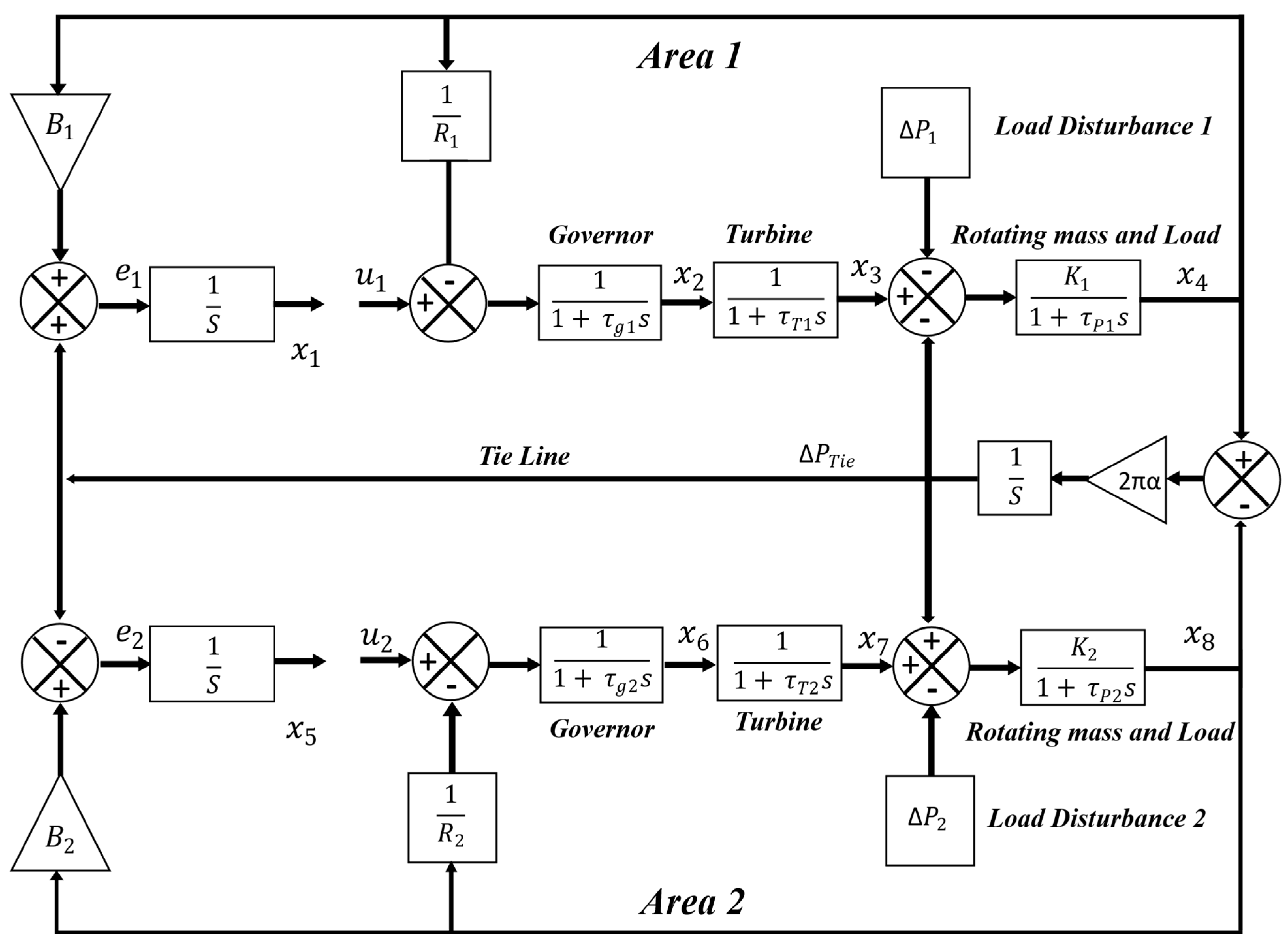

2. LFC System Model

2.1. Power System Dynamic Modeling

- : Frequency deviation from nominal value

- : Mechanical power output deviation

- : Governor valve position deviation

- : Tie-line power exchange deviation

2.2. State-Space Representation

2.3. Augmented Multi-Area System

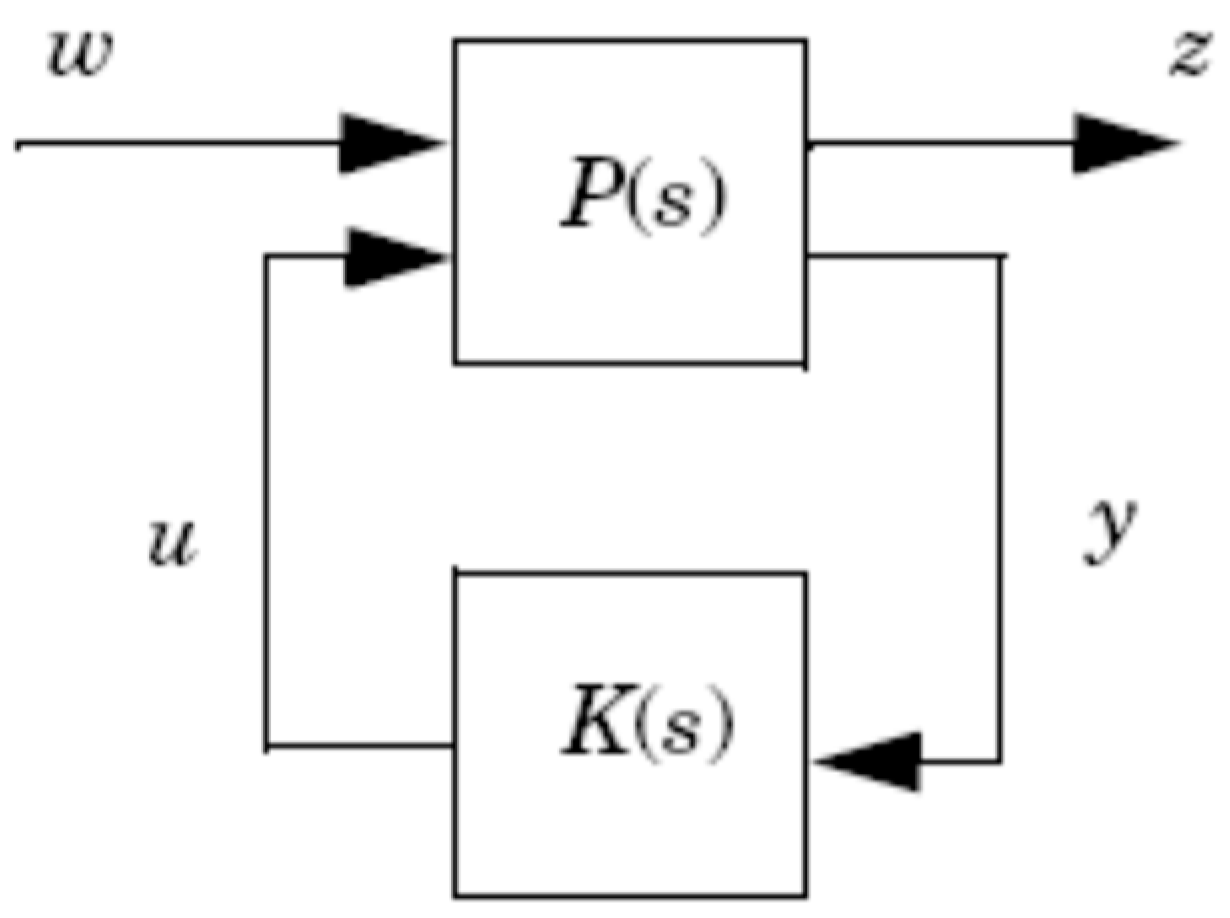

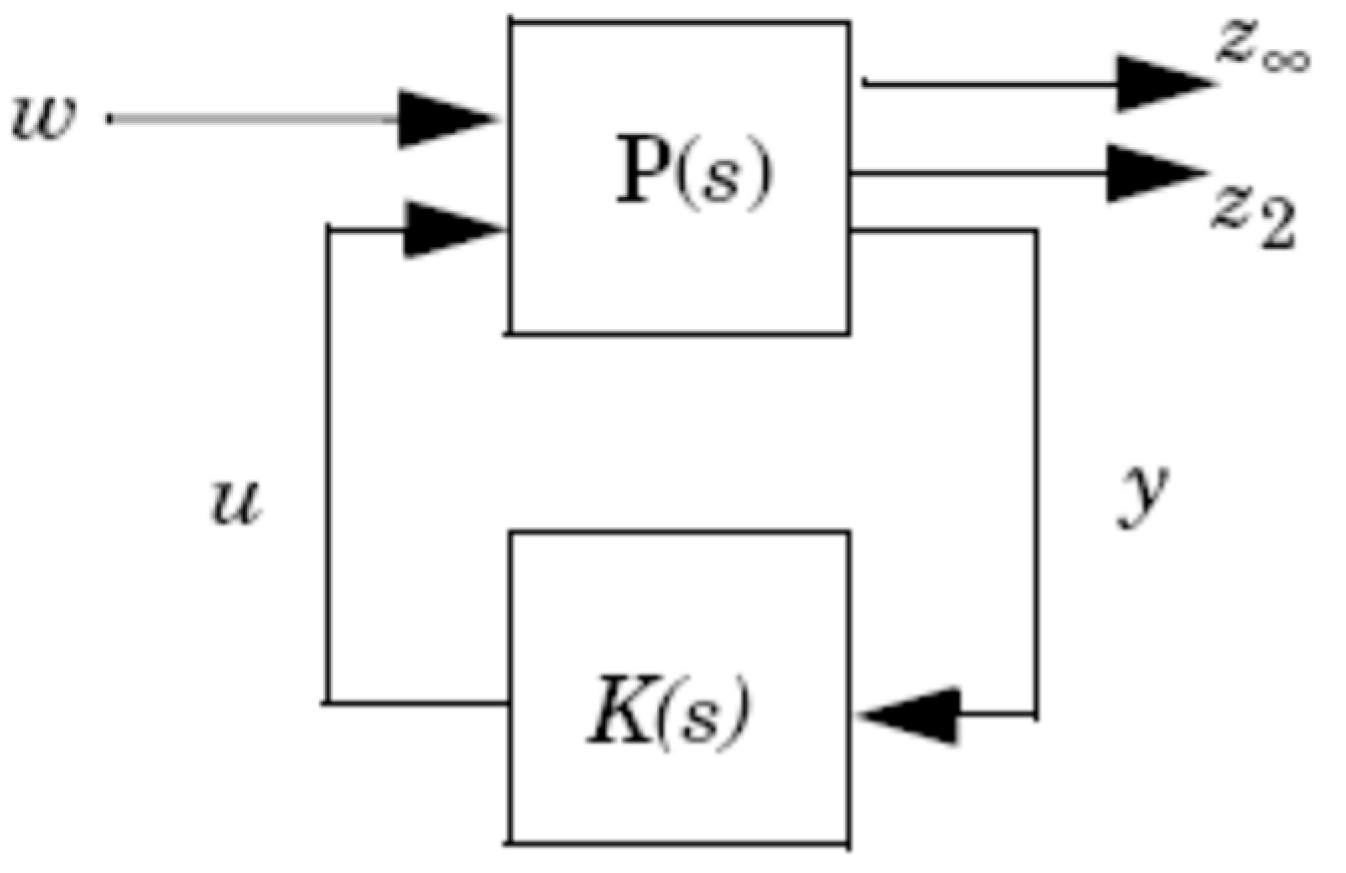

3. Robust Control Framework

3.1. H∞ Performance Criterion

- ▪

- Exogenous inputs (w): Disturbances, noise, and reference commands.

- ▪

- Control signals (u): The commands computed by the controller.

- ▪

- Performance outputs (z): The signals we wish to keep small, representing tracking errors, control efforts, etc.

- ▪

- Measured outputs (y): The sensor signals available to the controller.

3.2. LMI Formulations for Robust Control Synthesis

3.2.1. Mathematical Foundations

- The H∞ norm satisfies with the matrix exhibiting asymptotic stability (all eigenvalues possessing negative real parts)

- There exists a symmetric positive definite matrix satisfying the linear matrix inequality [66]:

3.2.2. Controller Parameterization

3.2.3. Evolution of H∞ Synthesis Methods

3.2.4. Convex Optimization Formulation

3.2.5. Application to Power System Control

- Fluctuations in load demand and generation patterns

- Parametric uncertainties arising from modeling inaccuracies

- Environmental variations affecting system dynamics (temperature, pressure, humidity)

- Equipment aging and performance degradation over time

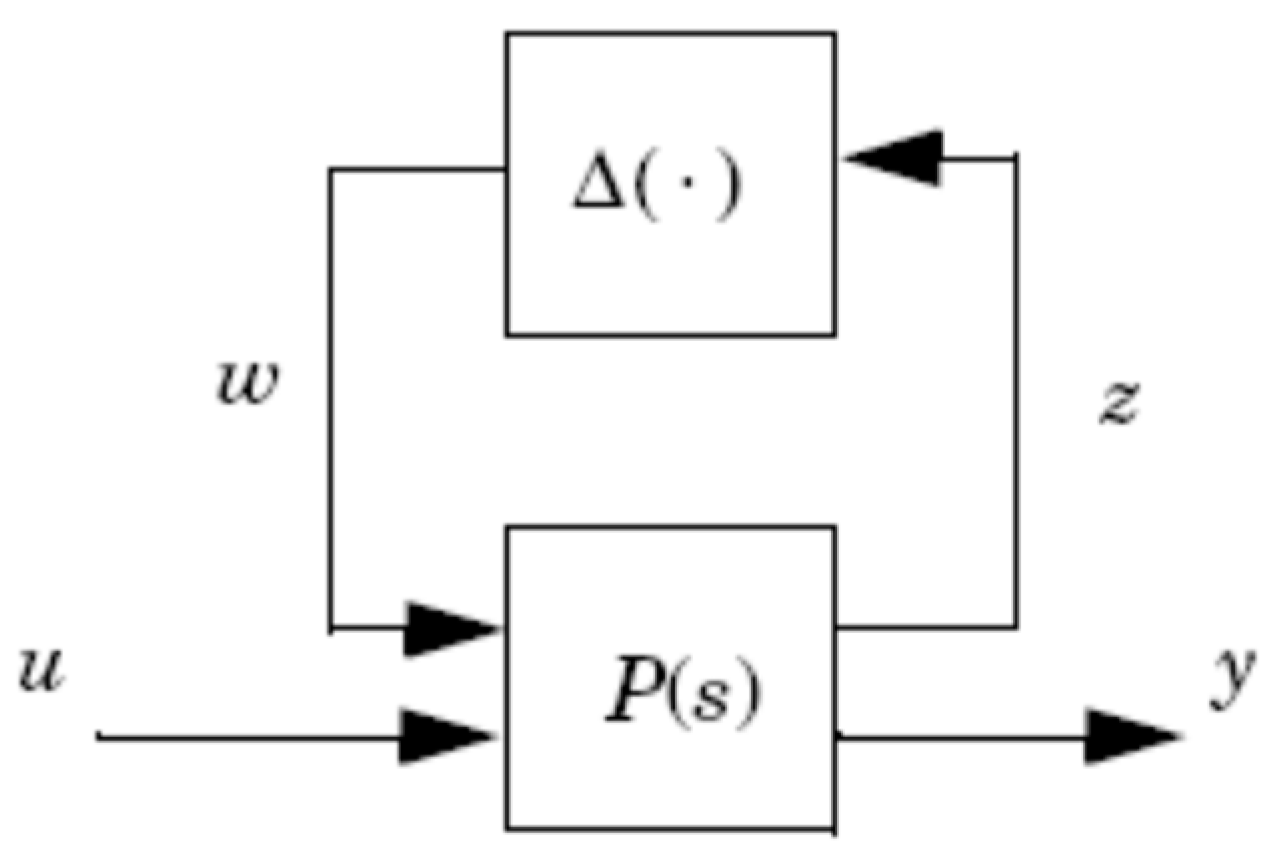

3.3. Synthesis of a Robust H∞ Controller for Interconnected Systems with Parametric Uncertainties

3.4. Performance Evaluation of the H∞ Controller and Motivation for H∞/H2 Synthesis

4. Hybrid H∞/H2 Control Architecture

4.1. Inherent Constraints of H∞ Control Formulations

4.2. Integrated H∞/H2 Control Synthesis

4.2.1. Dual-Channel Output Formulation

- : H∞ performance channel for worst-case disturbance attenuation

- : H2 performance channel for stochastic noise suppression and control effort optimization

4.2.2. Control Energy Optimization

4.2.3. Controller Dynamics Formulation

4.2.4. Multi-Objective Design Specifications

- 1.

- Internal Stability: The controller must ensure exponential stability of the closed-loop system.

- 2.

- H∞ Performance Bound: The H∞ norm from to must satisfy .

- 3.

- H2 Performance Optimization: Among all controllers satisfying conditions 1 and 2, minimize the H2 norm .

4.2.5. LMI Conditions for H2 Performance

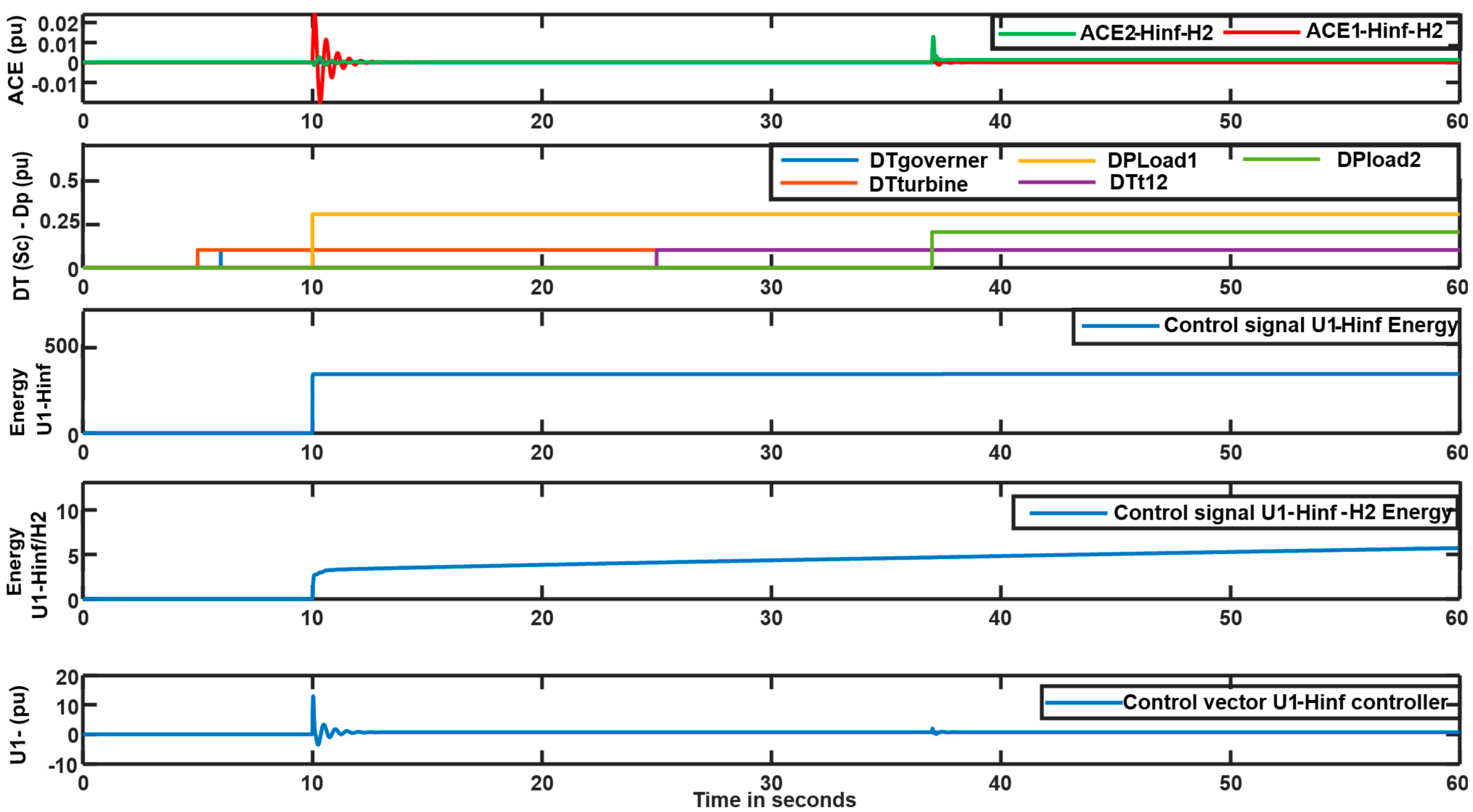

4.3. Performance Evaluation of the Mixed H∞/H2 Controller

- Control Effort (Actuator Force): The peak amplitude of the control signal u was reduced by three orders of magnitude, from an impractical 10,000 pu to a feasible 10 pu.

- Control Energy: The energy of the control signal, which is directly associated with mechanical wear and fuel consumption, was reduced from 400 units to just 5 units.

- Low Overshoot: The overshoot remains as low as 0.02 pu.

- Fast Settling Time: The transient response settles within 1 s.

4.4. Identification of a Stability Limit

5. Enhancing Robustness via Pole Placement Constraints

- Robust Performance (H∞): Worst-case disturbance rejection.

- Control Effort (H2): Minimization of actuator energy and stress.

- Transient Response (Pole Placement): Direct shaping of the dynamic response to ensure adequate damping and settling time, even under severe uncertainties.

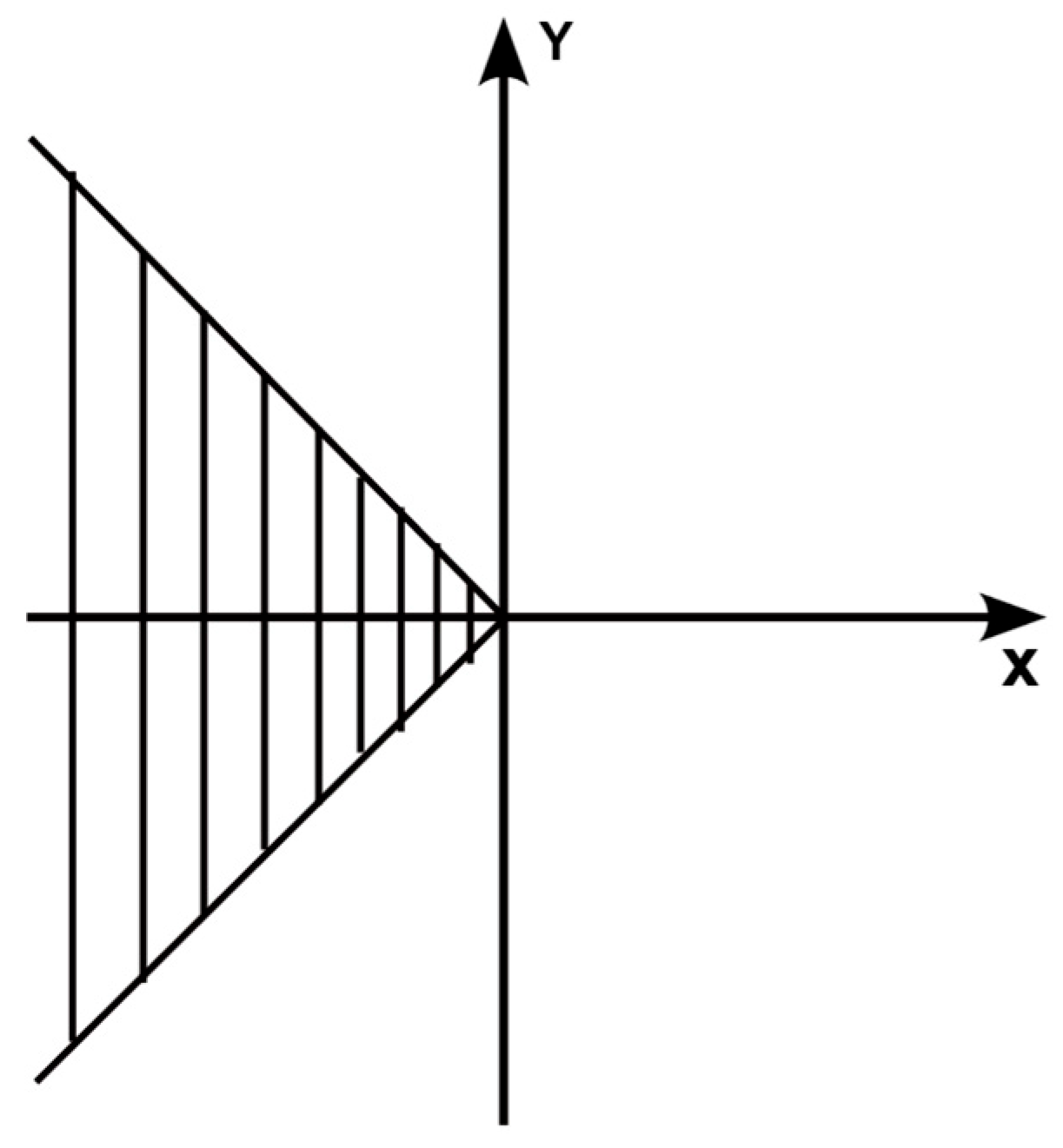

5.1. Robustness Enhancement Through Pole Region Constraints

5.1.1. LMI Region Characterization

5.1.2. Pole Placement LMI Condition

5.1.3. Controller Variable Transformation

5.2. Multi-Objective LMI Formulation

5.3. Performance Bounds

- H∞ norm constraint ensuring that it remains below 0.01,

- A minimum H2 norm for the control vector u, and

- Pole placement within the cone, ensuring stability and improved transient response.

5.4. Performance of the Enhanced Controller

- Stability: The system remains stable under extreme parametric uncertainty.

- Fast Convergence: ACE is driven to zero within a short settling time.

- Acceptable Transients: The response exhibits well-damped, acceptable transient behavior.

- Low Effort: It maintains the low control effort and energy consumption achieved by the mixed H∞/H2 synthesis.

6. Performance Enhancement via Measured Disturbance Compensation

6.1. Controller Synthesis via the LMI Framework for Non-Standard Plants

- Assumption 1. The pair (A, B2) is stabilizable, and the pair (A, C2) is detectable.

- Assumption 2. The direct feedthrough matrix D22 = 0.

- Assumption 3. D12 has full column rank and D21 has full row rank.

- Assumption 4. The subsystems P12(s) and P21(s) have no invariant zeros on the imaginary axis.

- As detailed in the plant formulation (Equations (36) and (37)), our system explicitly violates assumption 3:

- D12 = 0 (does not have full column rank).

- D21 is non-zero but does not have full row rank.

6.2. Synthesis of a Low-Order H∞ Controller via Structured LMIs

6.3. Cyber-Physical Resilience Analysis

- -

- Anomaly Detection via Forecasting:

- -

- Resilience to System-Wide Cyber-Attacks:

- The robust controller provides a stable foundation, preventing catastrophic failure even if it receives manipulated data.

- Detecting coordinated, multi-sensor attacks requires a dedicated security layer. Graph-theory-based methods can detect physically inconsistent measurement patterns across the network [74,75], identifying violations of grid physical laws invisible to a controller examining a single measurement channel.

6.4. Incorporation of Renewable Forecasting Errors into the Disturbance Vector

- -

- Effect on the bound:

- -

- Critical Flexibility in Weighting Function Design: The separation of disturbances into dis tinct channels enables the application of tailored weighting functions for each disturbance type in the generalized plant framework. The net load disturbance , can be weighted to emphasize low-frequency attenuation, while the forecast error () can be weighted according to its specific stochastic spectrum. This is a decisive advantage over the conventional approach of using a single, compromise weighting function for a combined, unknown disturbance, which inevitably leads to conservative performance.

- -

- Practical Performance Optimization: While the theoretical γ bound represents the worst-case gain, the actual output performance depends on the product γ·‖ω’‖. Since ‖‖ ≪ , the actual impact on system performance remains small:

6.5. Comparative Performance Analysis and Discussion

- Standard H∞ Controller

- Mixed H∞/H2 Controller

- Mixed H∞/H2 Controller with Pole Placement

- Proposed Controller: Mixed H∞/H2 with Pole Placement and Measured Disturbance (ΔPd) Compensation.

- The pure H∞ controller generates an impractically high control effort (10,000 pu amplitude, 400 units of energy), rendering it unsuitable for real-world application due to excessive actuator stress and energy consumption.

- The H∞/H2 controller fails to maintain stability under the tested severe parametric variations, becoming unstable.

- The H∞/H2 controller with Pole Placement successfully stabilizes the system but does not fully exploit the available information for optimal performance.

- The Proposed Controller not only guarantees robust stability but also achieves a dramatic 98% reduction in both control energy and peak control amplitude relative to the standard H∞ design.

- Minimized Mechanical Stress: Drastically reduced peak turbine torque and valve actuation extends the operational lifespan of turbine components and governors.

- Improved Fuel Efficiency: Lower control energy consumption is directly linked to reduced fuel usage during regulation.

- Enhanced Practical Viability: The controller operates within the practical limits of real actuators, moving from a theoretical solution to an implementable control law.

- A dramatic 98% reduction in the peak control signal and 97.5% reduction in control energy compared to the standard H∞ controller, indicating significantly reduced actuator stress and energy consumption.

- Maintained robust stability under severe turbine-governor time constant variations, where the basic H∞/H2 controller fails.

- Consistent high performance across various load disturbance magnitudes (– pu), maintaining 97–98% energy reduction.

- Excellent transient response with fast settling time (0.2 s) and minimal overshoot (0.83%), outperforming the H∞/H2/Pole Placement controller without measured disturbance.

7. Conclusions

- -

- Variable Communication Delays:

- -

- Decentralized Architectures:

- -

- Integration with Renewables:

- -

- Cyber-Physical Resilience:

- -

- Gain-Scheduled Extension:

- -

- Controller Order Reduction:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shafiee, M.; Sajadinia, M.; Zamani, A.-A.; Jafari, M. Enhancing the Transient Stability of Interconnected Power Systems by Designing an Adaptive Fuzzy-Based Fractional Order PID Controller. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hote, Y.V.; Jain, S. PID controller design for load frequency control: Past, present and future challenges. IFAC Pap. OnLine 2018, 51, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabahi, K.; Tavan, M. T2FPID Load Frequency Control for a two-area Power System Considering Input Delay. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Tabriz, Iran, 4–6 August 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çam, E.; Kocaarslan, I. Load Frequency Control in Two Area Power Systems Using Fuzzy Logic Controller. Energy Convers. Manag. 2005, 46, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Olvera, R.; Beltran-Carbajal, F.; Valderrabano-Gonzalez, A. Adaptive Neural Trajectory Tracking Control for Synchronous Generators in Interconnected Power Systems. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, F.; Ayaz, M.; Baig, D.-E.; Rizvi, S.M.H. Intelligent Control Algorithms for Enhanced Frequency Stability in Single and Interconnected Power Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, H.A. Adaptive fuzzy logic load frequency control of multi-area power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2015, 68, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, D.V.; Nguyen, K.; Thai, Q.V. Load-Frequency Control of Three-Area Interconnected Power Systems with Renewable Energy Sources Using Novel PSO~PID-Like Fuzzy Logic Controllers. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2022, 12, 8597–8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedabbasi, A.; Kiani, F. Sand Cat Swarm Optimization: A Nature-Inspired Algorithm to Solve Global Optimization Problems. Eng. Comput. 2022, 39, 2627–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, W.; Yameen, M.Z.; Tayab, A.; Qamar, H.G.M.; Ghith, E.; Tlija, M. Enhancing Load Frequency Control of Interconnected Power System Using Hybrid PSO-AHA Optimizer. Energies 2024, 17, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.A.; Hossain, M.J.; Pota, H.R. Nonlinear observer design for interconnected power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2012, 27, 831–840. [Google Scholar]

- Zapanta, J.M.; Santiago, R.M.; Abundo, M.L. Load Frequency Control of Interconnected Power System Using Particle Swarm Optimization Based Disturbance Observer-Enhanced PI Controller. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 10008353. [Google Scholar]

- Orka, N.A.; Muhaimin, S.S.; Shahi, N.S.; Ahmed, A. An enhanced gradient based optimized controller for load frequency control of a two area automatic generation control system. In Engineering Applications of Modern Metaheuristics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf, S.; Yousuf, V.; Gupta, N.; Alharbi, T.; Alrumayh, O. Enhanced Control Designs to Abate Frequency Oscillations in Compensated Power System. Energies 2023, 16, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.-Q.; Xie, X.-Q.; Chen, M.-R. An Adaptive Model Predictive Load Frequency Control Method for Multi-Area Interconnected Power Systems with Photovoltaic Generations. Energies 2017, 10, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, V.V.; Minh, B.L.N.; Amaefule, E.N.; Tran, A.-T.; Tran, P.T. Highly robust observer sliding mode based frequency control for multi area power systems with renewable power plants. Electronics 2021, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdphol, T.; Rahman, F.S.; Mitani, Y. Virtual Inertia Control Application to Enhance Frequency Stability of Interconnected Power Systems with High Renewable Energy Penetration. Energies 2018, 11, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Mishra, S. Non-linear disturbance observer-based improved frequency and tie-line power control of modern interconnected power systems. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2019, 13, 3564–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhbaibi, S.; Tlili, A.S.; Elloumi, S.; Braiek, N.B. H∞ Decentralized Observation and Control Interconnected Systems. ISA Trans. 2009, 48, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Z. A Distributed Model Predictive Control Based Load Frequency Control Scheme for Multi-Area Interconnected Power System Using Discrete-Time Laguerre Functions. ISA Trans. 2017, 68, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, G.I.Y.; Masum, M.; Siam, M. A new model-free control for load frequency control of interconnected power systems based on nonlinear disturbance observer. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 4998–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, V.V.; Vo, H.-D.; Minh, B.L.N.; Nguyen, T.M.; Tai, Y.W. Observer output feedback load frequency control for a two-area interconnected power system. J. Adv. Eng. Comput. 2018, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondalapati, S.; Dey, R.; Barna, C.; Balas, V.E. H∞-static output feedback based load frequency control of an interconnected power system with regional pole placement. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, V.V.; Tran, P.T.; Tran, T.A.; Tuan, D.H.; Phan, V.-D. Extended state observer-based load frequency controller for three-area interconnected power system. TELKOMNIKA (Telecommun. Comput. Electron. Control) 2021, 19, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, T.; Emami, K.; Yu, S.; Iu, H.; Wong, K.P. A novel quasi-decentralized functional observer approach to LFC of interconnected power systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Boston, MA, USA, 17–21 July 2016; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Sheng, L.; Xu, D.; Yang, W.; Liu, Q. H∞ Robust Load Frequency Control for Multi-Area Interconnected Power System with Hybrid Energy Storage System. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H. Decentralized robust control system design for large-scale uncertain systems. Int. J. Control 1988, 47, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.S.; Braiek, N.B. Decentralized Observer-Based Guaranteed Cost Control for Nonlinear Interconnected Systems. Int. J. Control Autom. 2009, 2, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Alhelou, H.H.; Golshan, M.E.H.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Deterministic Dynamic State Estimation-Based Optimal LFC for Interconnected Power Systems Using Unknown Input Observer. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 11, 1582–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.-T.; Minh, B.L.N.; Huynh, V.V.; Tran, P.T.; Amaefule, E.N.; Phan, V.-D.; Nguyen, T.M. Load Frequency Regulator in Interconnected Power System Using Second-Order Sliding Mode Control Combined with State Estimator. Energies 2021, 14, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, M.V.; Vijayan, V. Model-predictive control-based hybrid optimized load frequency control of multi-area power systems. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, V.V.; Pham, V.-T.; Tran, P.T.; Nguyen, T.M.; Phan, V.-D. Advanced Sliding Mode Observer Design for Load Frequency Control of Multiarea Multisource Power Systems. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2022, 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, P. Decentralized sliding mode load frequency control for multi area power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 4301–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. A novel hybrid LFC scheme for multi-area interconnected power systems considering coupling attenuation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Wang, F. Data-Driven Load Frequency Control for Multi-Area Power System Based on Switching Method under Cyber Attacks. Algorithms 2024, 17, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Jaiswal, S.; Latif, A.; Das, D.C.; Sinha, N.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Ustun, T.S. Isolated and interconnected multi-area hybrid power systems: A review on control strategies. Energies 2021, 14, 8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Shayeghi, H.; Nejad, H.M.; Younesi, A. Reinforcement learning based PID controller design for LFC in a microgrid. COMPEL Int. J. Comput. Math. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2017, 36, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Liu, X.; Xiao, G.; Ge, S.S. Observer-Based Sliding Mode Load Frequency Control of Power Systems under Deception Attack. Complexity 2021, 2021, 8092206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, F.R.; Nayem, Z.; Sarker, S.K.; Datta, D.; Fahim, S.R.; Muyeen, S.M.; Sheikh, R.I.; Das, S.K. A novel intrusion mitigation unit for interconnected power systems in frequency regulation to enhance cybersecurity. Energies 2021, 14, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Sun, Q. Distributed state estimation of interconnected power systems with time-varying disturbances and random communication link failures. Energy Convers. Econ. 2024, 5, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, B.; Jena, N.K.; Sahu, B.K.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L. Frequency stability improvement in EV-integrated power systems using optimized fuzzy-sliding mode control and real-time validation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sousy, F.F.M.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Aljumah, A.S.; Aly, M.; Almutairi, S.Z.; Mohamed, E.A. Design optimization of improved fractional-order cascaded frequency controllers for electric vehicles and electrical power grids utilizing renewable energy sources. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M.; Mohamed, E.A.; Elmelegi, A.; Aly, M.; Elbaksawi, O. Optimum modified fractional order controller for future electric vehicles and renewable energy-based interconnected power systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 29993–30010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Southern Power Grid Company. Annual Report April 2021. Available online: https://www.csg.cn (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Malik, T.H.; Bak, C. Challenges in detecting wind turbine power loss: The effects of blade erosion, turbulence, and time averaging. Wind. Energy Sci. 2025, 10, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobev, P.; Greenwood, D.M.; Bell, J.H.; Bialek, J.W.; Taylor, P.C.; Turitsyn, K. Deadbands, droop, and inertia impact on power system frequency distribution. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 3098–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Y.C.; Muttaqi, K.; Negnevitsky, M. Modelling of hydraulic governor-turbine for control stabilization. ANZIAM J. 2008, 49, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C.; Nicolet, C.; Comes, J.; Avellan, F. Methodology to Determine the Parameters of the Hydraulic Turbine Governor for Primary Control. RENOVHydro Project, Tech. Rep., 2015. Available online: https://www.hdynamics.ch/Profile/Publications/pdf/HYDRO_2019_2_Landry.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zhou, X.; Dou, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, C.; Xu, D. Distributed sliding mode fault-tolerant LFC for multiarea interconnected power systems under sensor fault. Complexity 2022, 2022, 6271232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Yang, G.; Wang, P. Active fault-tolerant load frequency control for multi-area power systems with electric vehicles under deception attacks. IET Control. Theory Appl. 2024, 18, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; Fouad, A.A. Power System Control and Stability, 2nd ed.; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nohra, C.; Ghandour, R.; Khaled, M.; Outbib, R. Robust FDI for turbine-governor and network parameters in interconnected power systems via mixed H∞/pole placement observers. Results Control Optim. 2025, 21, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, W.; Niculescu, S.-I. Stability, Control, and Computation for Time-Delay Systems: An Eigenvalue-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H.; Dong, C. The Small Signal Stability Region of Power Systems with Time Delay; School of Electrical and Information Engineering, Tianjin University: Tianjin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Qi, T.; Ma, D.; Chen, J. Limits of Stability and Stabilization of Time-Delay Systems: A Small Gain Approach; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q.; Karimi, H.R. Stability, Control and Application of Time-Delay Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, S.M.; Syed, M.H.; Roscoe, A.J.; Burt, G.M.; Braun, J.-P. Measurement and analysis of PMU reporting latency for smart grid protection and control applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48689–48698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std C37.118.1-2011; IEEE Standard for Synchrophasor Measurements for Power Systems. IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011.

- Hojabri, M.; Dersch, U.; Papaemmanouil, A.; Bosshart, P. A comprehensive survey on phasor measurement unit applications in distribution systems. Energies 2019, 12, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, C.; Sahu, B.K.; Mishra, M.; Rout, P.K. Real-time grid monitoring and protection: A comprehensive survey on the advantages of phasor measurement units. Energies 2023, 16, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Das, S.; Piran, J.; Han, Z. A survey on physical layer security of ultra/hyper reliable low latency communication in 5G and 6G networks: Recent advancements, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 112320–112353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P. Power System Stability and Control; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Åström, K.J.; Murray, R.M. Feedback Systems; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liu, C.; Tao, J.; Liu, S.; Gao, W. Hybrid traffic scheduling in 5G and time-sensitive networking integrated networks for communications of virtual power plants. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyizere, D.; Letting, L.K.; Munyazikwiye, B.B. Effects of communication signal delay on the power grid: A review. Electronics 2022, 11, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apkarian, P.; Gahinet, P. A linear matrix inequality approach to H∞ control. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 1994, 4, 421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J.C.; Glover, K.; Khargonekar, P.; Francis, B. State-space solutions to standard H2 and H∞ control problems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1989, 34, 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahinet, P. A Convex Parametrization of H∞ Suboptimal Controllers. In Proceedings of the Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Tuscon, AZ, USA, 16–18 December 1992; pp. 937–942. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Doyle, J.C.; Glover, K. Robust and Optimal Control; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chilali, M.; Gahinet, P.M. H∞ design with pole placement constraints: An LMI approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1996, 41, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, C.; Chilali, M.; Gahinet, P. Multiobjective Output-Feedback Control via LMI Optimization. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1997, 42, 896–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, G.; Murao, S.; Koyama, N.; Yoshida, M. Low Order H∞ Controller Design: An LMI Approach. In Proceedings of the 7th European Control Conference (ECC), Cambridge, UK, 31 August–3 September 2003; pp. 3070–3075. [Google Scholar]

- Nehme, B.; Hajj, E.; Nohra, C. Energy consumption predictions using a neural network. Energy Inform. 2025, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doostmohammadian, M.; Zarrabi, H.; Charalambous, T. Sensor fault detection and isolation via networked estimation: Rank-deficient dynamical systems. Int. J. Control 2023, 96, 2853–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doostmohammadiany, M.; Charalambous, T.; Shafie-Khah, M.; Meskin, N.; Khan, U.A. Simultaneous distributed estimation and attack detection/isolation in social networks: Structural observability, Kronecker-product network, and Chi-square detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Systems (ICAS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–13 August 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apkarian, P.; Noll, D.; Pellanda, P.C. Nonsmooth H∞ Synthesis. ONERA-CERT, Centre d’Etudes et de Recherche de Toulouse, Control System Department, Toulouse, France, and IME, Electrical Engineering Department, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Available online: http://pierre.apkarian.free.fr/papers/frequency.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

| Performance Metric | Standard H∞ | H∞/H2 | H∞/H2/Pole Placement | Proposed Controller (Measured Disturbance) | Improvement vs. Standard H∞ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Control Signal (pu) | 8000 | - | 33 | 165 | 98% reduction |

| Control Energy (H2 norm) | 400 | - | 5.2 | 10 | 97.5% reduction |

| Settling Time (s) | 0.011 | - | 7.0 | 0.2 | - |

| Overshoot (%) | 0.15% | - | 2.6% | 0.83% | - |

| Stability (Large Turbine/Gov. Variation) | Stable | Unstable | Stable | Stable | Superior robustness |

| Control Energy | Standard H∞ | Proposed Controller (Measured Disturbance) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control Energy (ΔP = 0.1 pu) | 128 | 3.7 | 97% reduction |

| Control Energy (ΔP = 0.4 pu) | 510 | 15 | 97% reduction |

| Peak Control (ΔP = 0.1 pu) | 2700 | 54 | 98% reduction |

| Peak Control (ΔP = 0.4 pu) | 10,800 | 216 | 98% reduction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nohra, C.; Ghandour, R.; Khaled, M.; Outbib, R. A Novel H∞/H2 Pole Placement LFC Controller with Measured Disturbance Feedforward Action for Disturbed Interconnected Power Systems. Automation 2025, 6, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040090

Nohra C, Ghandour R, Khaled M, Outbib R. A Novel H∞/H2 Pole Placement LFC Controller with Measured Disturbance Feedforward Action for Disturbed Interconnected Power Systems. Automation. 2025; 6(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleNohra, Chadi, Raymond Ghandour, Mahmoud Khaled, and Rachid Outbib. 2025. "A Novel H∞/H2 Pole Placement LFC Controller with Measured Disturbance Feedforward Action for Disturbed Interconnected Power Systems" Automation 6, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040090

APA StyleNohra, C., Ghandour, R., Khaled, M., & Outbib, R. (2025). A Novel H∞/H2 Pole Placement LFC Controller with Measured Disturbance Feedforward Action for Disturbed Interconnected Power Systems. Automation, 6(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040090