Abstract

Examinations are typically used by educational institutions to assess students’ strengths and weaknesses. Unfortunately, exam malpractices like cheating and other forms of academic integrity violations continue to present a serious challenge to the evaluation framework because it seeks to provide a trustworthy assessment. Existing methods involving human invigilators have limitations, as they must be physically present in examination settings and cannot monitor all students who take an exam while successfully ensuring integrity. With the developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision, we now have novel possibilities to develop methods for detecting students who engage in cheating. This paper presents a practical, real-time detection system based on computer vision techniques for detecting cheating in examination halls. The system utilizes two primary methods: The first method is YOLOv8, a top-of-the-line object detection model, where the model is used to detect students in video footage in real time. After detecting the students, the second aspect of the detection process is to apply pose estimation to extract key points of the detected students. For the first time, this paper proposes to measure angles from the geometry of the key points of detected students by constructing two triangles using the distance from the tip of the nose to both eyes, and the distance from the tip of the nose to both ears; one triangle is sized from the distance to the eyes, and the other triangle contains the measurements to their ears. By continually calculating these angles, it is possible to derive each student’s facial pose. A dynamic threshold is calculated and updated for each frame to better represent the body position in real time. When the left or right angle pass that threshold, it is flagged as suspicious behavior indicating cheating. All detected cheating instances, including duration, timestamps, and captured images, are logged automatically in an Excel file stored on Google Drive. The proposed study presents a computationally cheap approach that does not utilize a GPU or additional computational aspects in any capacity. This implementation is affordable and has higher accuracy than all of those mentioned in prior studies. Analyzing data from exam halls indicated that the proposed system reached 96.18% accuracy and 96.2% precision.

1. Introduction

Maintaining academic integrity during examinations has long been a major concern for educational institutions. Studies indicate that academic dishonesty is widespread, with plagiarism prevalence, cheating, and other forms of misconduct reported to be as high as 80% among high school and post-secondary students [1]. Copying from peers is among the most common cheating methods [2], and research by the Ad Council and Educational Testing Service revealed that approximately 95% of students who cheat are not detected by invigilators [3]. These are some facts that demonstrate how serious the problem is and what effective solutions are needed.

Methods of invigilation that are traditional and use human supervisors have several limitations. Invigilators may become fatigued, distracted, or biased, particularly when working through long or multiple test periods, making monitoring less consistent and effective. Subtle or technologically aided methods of cheating, including smartphones, coded communications, or hidden earpieces, are becoming very hard to detect by the human eye. Moreover, the absence of tangible evidence often hampers the enforcement of academic-integrity policies within institutions. This limitation is further exacerbated by the high costs of hiring, training, and administering invigilators, as well as the weak deterrent effect that they provide. These restrictions show the importance of more reliable, scalable, and cost-effective mechanisms to supervise the examination.

Recent breakthroughs in AI and computer vision offer new opportunities to address these challenges. Monitoring systems based on AI can provide continuous, objective, evidence-based surveillance without depending on human supervision. Machine learning and computer vision have already proved useful in several areas, such as retail sales prediction [4], and reading medical prescriptions [5]. Researchers have used AI and vision-based technology in the learning field to improve academic honesty. As an example, YOLOv4 was applied to classroom engagement detection [6], machine learning was applied to detect AI-generated content [7], YOLO-based models were applied to online examination surveillance [8], and face-recognition and eye-tracking systems were studied to identify identity and track behavior [9,10]. These studies show the promise of AI as an educational application but also show significant shortcomings in terms of scalability, computational cost, and real-time adaptability.

While progress has been made, there are still research gaps present. Previous research studies are mostly designed for online examinations or use cases where resources and implemented technology are not an issue, and there is little attention on physical exam hall settings, where it is practical to monitor large populations on a real-time scale. The computational power required, the use of complex, costly, and inconvenient to set up 3D pose estimation models that do not rely on duration for tracking potential suspicious behaviors, and not allowing the model to be deployed on low-throughput computing power, limits its practicality. Further, very few systems are designed to collect data to automatically log the behavior or act as a form of evidence to be used for administration, including that can be used for potential academic dishonesty.

The limitations of these past studies are addressed within this research design by creating a feasible model for real-time cheating detection in physical examinations. The model is primarily based around the built-in YOLOv8 pose estimation model, to provide anchor-free detection capable of increasing detection accuracy and efficiency. Distances and angles between key points are used as metrics to measure abnormal head movements, and a dynamic threshold range is used to detect suspicious behavior. The system is designed to be deployed on low-power computing devices such as a Raspberry Pi 5 and the model can feasibly run in real-time with an overall low computational load. In addition to detection, the framework logs the time of the suspicious behavior, gathers a form of evidence, and is capable of storing data in real-time for review by administration, which is an important consideration in the application of academic integrity.

This work distinguishes itself from prior literature. The key contributions are as follows:

- Novel Dual-Triangle Pose Estimation Approach: Introduced a unique method to estimate head pose using two geometric triangles (nose-eyes and nose-ears), allowing accurate detection of suspicious head movements during exams.

- GPU Free Real-Time Operation: Developed an efficient system that runs on low-power hardware like Raspberry Pi 5 without requiring GPU acceleration, making it accessible and cost-effective for institutions.

- Dynamic Angle Thresholding: Designed a dynamic thresholding mechanism (centered around 60°) that adjusts per student and scene context, significantly reducing false positives and negatives in pose-based cheating detection.

- Integration with YOLOv8 for Accurate Student and Key point Detection: Leveraged YOLOv8 for high-precision detection and tracking of students and key facial landmarks, achieving over 96% accuracy and real-time performance (6 FPS).

- Automated Logging and Cloud-Based Reporting: Incorporated a fully automated logging system that records cheating instances with time, duration, and screenshots in an Excel sheet saved directly to Google Drive.

- Validated in Real-World Exam Settings: Tested the model over six consecutive examination days and in controlled experiments, achieving 96.18% accuracy and 96.2% precision in detecting various forms of cheating.

- Benchmarking and Outperformance of State-of-the-Art: Demonstrated superior performance compared to existing cheating detection systems in terms of both accuracy and computational efficiency, setting a new standard for low-resource exam monitoring.

2. Literature Review

According to a study conducted by Josephson Institute of Ethics (2010), about 59% of high school students admitted that they cheated in test or exam in the last year [11]. Additionally, research conducted by University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) indicates that about 70% of students have engaged in some form of academic dishonesty [12]. The National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) reports that 60% of students had used unauthorized materials or devices during an exam [13]. Furthermore, a study published in the journal “Academic Medicine” (2017) found that 34% of medical students admitted to using unauthorized aids during exams [14]. This is therefore a major problem that raises questions about the integrity of exams, institutions, and the role of invigilators. This work presents an optimized model using computer vision that does not require an invigilator. Computer-vision techniques enable efficient and resource-aware cheating detection.

To mitigate cheating, various computer vision-based models have been explored. Padhiyar et al. [15] utilized the CIFAR-100 dataset for human pose detection, the LIRIS dataset for movement analysis, and a custom dataset with recordings of misconduct. Their model, implemented with Cascade and YOLO algorithms, demonstrated that YOLO significantly outperformed Cascade, achieving 87.20% accuracy versus 60.46%. Mahmood et al. [2] developed a dataset categorized into four behavioral types and employed Faster R-CNN and MTCNN for face recognition and cheating classification. The system achieved 98.5% classification accuracy and a face recognition accuracy of 95% using an invigilation-specific dataset. Radwan et al. [16] adopted single-stage detectors such as SSD and YOLO, reporting an accuracy of 97.8%. Similarly, Wan et al. [17] combined YOLOv3 for object detection with OpenPose for pose estimation on a dataset of 5000 images, achieving 96.2% accuracy in live video testing. An extension of this work by [18] introduced a modified YOLOv3 with GIoU and ShuffleNet to improve bounding box localization, resulting in an 88.03% accuracy.

Machine learning approaches have also been implemented. Alsabhan [19] proposed a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network with dropout, dense layers, and the Adam optimizer to detect cheating based on behavioral and academic data. This model improved accuracy by 90% over previous methods. The publicly available CUI-Exam dataset, containing 4000 annotated images and 100 videos across six behavior classes, was utilized in [20]. Techniques such as PCA and Ant Colony Optimization were applied alongside CNNs and SVMs, yielding up to 92.99% accuracy. Evaluation was also performed on the CIFAR-100 dataset. Other research [21] incorporated AI techniques to detect hand, head, and eye movements using Viola-Jones for face detection, Gabor filters for feature extraction, PCA for dimensionality reduction, and Backpropagation Neural Networks for classification.

Recent literature has also explored 3D pose estimation in diverse domains. Menanno et al. (2024) [22] proposed an ergonomic risk assessment system using 3D pose estimation and a collaborative robot to reduce musculoskeletal strain in industrial environments. Meanwhile, Salisu et al. (2025) [23] provided a comprehensive review of deep learning-based 3D human pose estimation techniques, highlighting advancements, benchmarks, and common challenges such as occlusions and real-time inference. However, neither study addressed real-time, GPU-free pose-based behavior detection for academic integrity in classroom settings, which remains the central focus and innovation of this paper.

From the literature, it is evident that most research has focused on online exams or high-resource models, with limited attention given to scalable, real-time cheating detection systems for physical classrooms. Existing approaches often suffer from high computational demands, limited scalability, and lack of real-time data integration. The absence of duration tracking and minimal support for low-power deployment further highlight the research gap.

Our proposed system addresses all the discussed research gaps by deploying an optimized system that enhances the reliability of cheating detection in diverse academic settings. It is compatible with low-power devices, such as Raspberry Pi 5. This paper incorporated the dynamic thresholding mechanism, which adapts to different academic configurations, thereby overcoming the limitations of room layouts. Our system detects not only cheating behaviors but also the duration of such activities, providing a more comprehensive analysis than an invigilator, as it also takes multiple pictures when students engage in cheating for a long period of time. Furthermore, our system provides real-time data logging by capturing and saving images on Google Drive while also preparing an Excel sheet that records the student’s type of cheating behavior and its duration.

3. Methodology

The proposed methodology addresses certain requirements to ensure effective cheating detection in examination halls. In order to guarantee real-time surveillance, the model is capable of running at the lowest possible rate of three frames per second (FPS), a rate that offers reasonable temporal resolution to allow continuous surveillance and successful detection [24]. Both human detection and pose estimation must be accurate because accurate localization and analysis of student movements are key to detecting abnormal behavior linked to cheating. In addition to the power of detection, the system also incorporates other aspects of estimating the number of cheating cases, capturing information, and providing communication solutions to aid in the decision-making process by the administrators. Another basic consideration is processing efficiency. The model is optimized to run computationally intensive tasks on low-power hardware and, therefore, can be deployed in resource-constrained environments without necessarily relying on high-performance hardware. In addition to efficiency, the methodology focuses on innovation since it incorporates a new pose estimation strategy that sets a new performance benchmark.

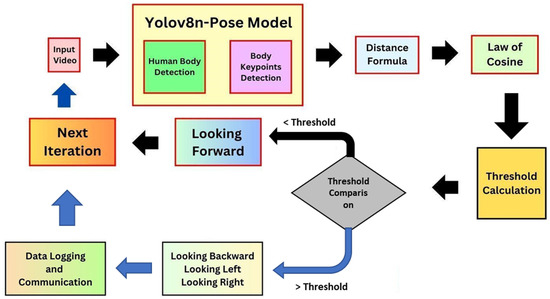

According to these requirements, the given framework, depicted in Figure 1, combines detection, pose estimation, and behavior analysis in one stream of optimized functions. The subsections below describe in detail the system components and justify the design decisions.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the proposed model illustrating the sequential process of student detection, pose estimation, abnormal movement identification, cheating duration tracking, and real-time data logging for examination hall monitoring.

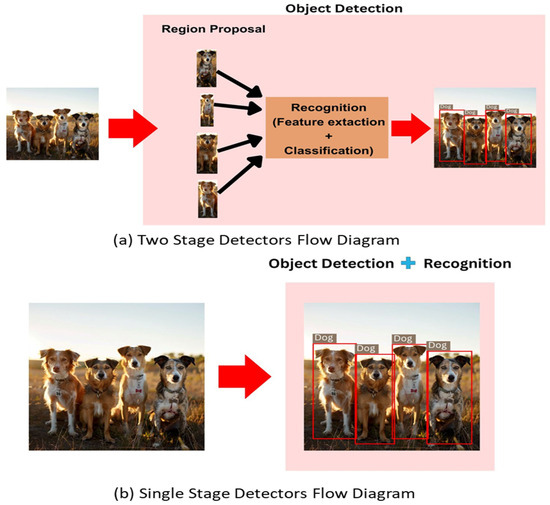

The first stage of the system uses an object detector that can reliably identify all students in the examination hall. Object detection models fall into two categories: single-stage and two-stage detectors. Their characteristics and performance are summarized in Table 1. Additionally, their operational mechanisms are shown in Figure 2 for clarity.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of single-stage and two-stage object detectors in terms of speed, accuracy, and suitability for real-time examination hall surveillance.

Figure 2.

(a) Flow diagram of two-stage detectors, showing the sequential process of region proposal followed by object recognition. (b) Flow diagram of single-stage detectors, presenting the integrated approach where detection and recognition occur in one stage.

Given the strict needs of real-time surveillance, the proposed method uses a single-stage detector. This choice is based on two main reasons: the need to efficiently detect large objects, like human figures, and the need for fast processing to ensure continuous monitoring in exam settings. Single-stage detectors can perform object detection in a single computational pass, making them especially suitable for this task. They offer both the accuracy and speed needed for effective surveillance in the exam hall.

We choose to use the YOLOv8-pose model in this work for both object detection and pose estimation because it is highly accurate and fast. The YOLO architecture, first proposed in 2016 [25], created a shift in the object detection field by framing detection by combining region proposal and object classification into a single architecture. Subsequent versions of YOLO have followed suit, steadily increasing the detection accuracy, speed of detection, and overall performance while retaining the simple architecture of YOLO.

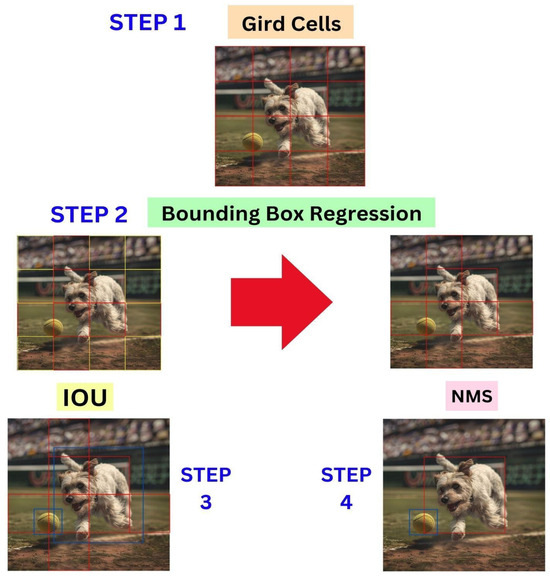

YOLOv8 achieves the object detection portion of its processing in four different ways, which are shown in Figure 3. The first of these four methods is to break the input image into a grid of N × N pixels, where each cell is responsible for predicting and classifying all objects present within its boundaries. The grid format allows for local and distributed detection across the size of the input image, so instead of detecting a single object in a single frame, YOLO is able to detect many objects in a single image.

Figure 3.

YOLO Object Detection Algorithm process diagram illustrating image splitting into grid cells, bounding box regression, Intersection over Union calculation (IoU), and Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) to ultimately determine the location of the object.

In YOLO, a specific detection algorithm is used on each grid cell that produces a bounding box for any identified object, classes with each probability, and confidence. The output of this process is as follows:

In this definition, is the object score, which is the probability of an object being present in the predicted bounding box. The notations are the class probabilities and represent the probability of the detected object being in each of the C pre-defined categories. The notations are the coordinates of the center of the bounding box, while are the bounding box width and height.

When several bounding boxes overlap for a single object, Intersection over Union (IoU) is applied to find the most accurate boxes. IoU is calculated as:

Only bounding boxes with an IoU greater than a predefined threshold are retained, while others are discarded to reduce redundancy.

Even after applying IoU filtering, there may still be several bounding boxes with high IoU scores for the same object. To reduce redundancy, we apply Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS). NMS selects the bounding box with the highest confidence score while systematically suppressing all bounding boxes that overlap with it and have lower scores. This results in finding the single most reliable bounding box to represent each object in the output, allowing for clearer and more accurate detection results.

Given the defined optimization requirements, the YOLO framework was identified as the most appropriate object detection algorithm for the proposed system. A comparative evaluation of established detection models, including Faster R-CNN, SSD, and RetinaNet, was undertaken to determine the most effective choice. As reported in [26], “Of all the popular object recognition machine learning models such as Faster R-CNN, SSD, and RetinaNet, YOLO is the most popular in terms of accuracy, speed, and efficiency.” This evaluation aligns well with the objectives of achieving real-time detection with high accuracy under limited computational resources.

While YOLO was originally introduced for object detection, pose estimation functionality was later incorporated from YOLOv8 onwards. Among the existing 2D pose estimation algorithms, the YOLOv8-Pose model demonstrates superior performance in terms of speed and accuracy [27]. According to [26], “Unlike top-down approaches, multiple forward passes are done away, as all persons are localized along with their pose in a single inference. YOLO-Pose achieves new state-of-the-art results on COCO validation (90.2% AP50) and test-dev set (90.3% AP50), surpassing all existing bottom-up approaches in a single forward pass without flip test, multi-scale testing, or any other test time augmentation” [28]. Following the adoption of YOLOv8-Pose as the detection and estimation framework, it was necessary to identify the most suitable version for the proposed application. Table 2 presents a comparison of different YOLOv8-Pose variants, as reported by the original developers [29].

Table 2.

Comparative performance metrics of different YOLOv8-Pose model variants, including model size, mean Average Precision (mAP), inference speed, parameter count, and floating-point operations per second (FLOPs) [29].

Multiple YOLO versions exist, each differing in pose estimation capability, accuracy, speed, and hardware requirements. For this study, YOLOv8 was selected as it provides an effective balance between speed and accuracy under CPU constraints. While YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 focus primarily on object detection without integrated pose estimation, YOLOv11 includes this feature but at a higher computational cost. According to the official documentation [30], YOLOv8-Pose achieves comparable accuracy to YOLOv11-Pose while delivering faster CPU performance. The YOLOv8n-Pose variant was particularly suitable for examination halls with short viewing distances, offering sufficient FPS with low computational demand. Moreover, its built-in tracking support ensures a unified and optimized framework for both detection and pose estimation.

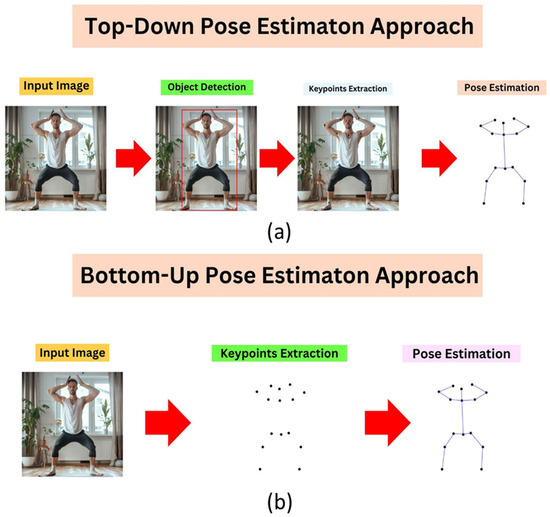

After object detection, the next step is “pose estimation”. 2D and 3D pose estimation approaches exist in the field of machine learning. They differ from each other in terms of accuracy, cost, and computing power. Table 3 illustrates the main difference between 2D and 3D Pose Estimation Algorithms. The 2D pose estimation algorithm was chosen for its real-time performance and lower computational demands. Unlike 3D estimation, it does not require depth information, which is unnecessary when most body key points lie in a similar depth plane. Two main approaches exist: top-down (detect individuals first, then estimate poses) and bottom-up (detect all key points first, then group them). As shown in Table 4 and illustrated in Figure 4, the top-down method was preferred due to its robustness in crowded or occluded environments, making it well-suited for examination halls where accurate per-student tracking is required to detect suspicious behavior.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of 2D and 3D pose estimation algorithms in terms of methodology, accuracy, computational complexity, and application scope.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Pose Estimation approaches.

Figure 4.

Flow diagrams of pose estimation approaches: (a) Top-Down method, where individuals are first detected and poses are then estimated for each person, and (b) Bottom-Up method, where all key points are detected first and subsequently grouped into individual poses.

Although the Bottom-Up approach offers higher speed (Table 4), the Top-Down approach was adopted to meet accuracy requirements in the examination hall scenario. Students seated in overlapping rows created frequent occlusions, where Bottom-Up methods often misgrouped keypoints. In contrast, the Top-Down approach provided more reliable pose estimation under such conditions.

Besides YOLOv8, we also examined various other frameworks: OpenPose, HRNet, and MediaPipe. OpenPose provides respectable pose accuracy, but it requires GPU compatibility and is not suitable for embedded use. HRNet is also computationally expensive and utilizing high resolution features will make it perform poorly on low power devices. MediaPipe is lightweight, but not very robust in crowded or occluded classroom contexts. In summary, YOLOv8 gives the best overall trade-off of accuracy, speed and resource performance for our intended use in a real-time processing, GPU-free, deployment configuration.

In addition, when discussing contemporary, state-of-the-art methodologies, several transformer-based pose estimation models like HRFormer and ViTPose have recently been shown to have outstanding accuracy thanks to global attention-based mechanisms. However, both transformer architectures are computationally demanding, with significant parameter sizes and inference times that require dedicated GPUs to run in real-time. These considerations make such solutions prohibitive for deployment on low power or embedded-based systems. Conversely, YOLOv8 provides a single-stage bottom-up framework that can efficiently perform both object and key point detection even on CPU-only based hardware. This efficiency is in line with the aim of our work—to create a lightweight, GPU-free framework, which can still provide reliable pose estimation and cheating detection performance in real-life classroom environments.

To identify the x and y coordinates for 17 body key points, the YOLOv8 tracking model was applied; those are the nose, the eyes, the ears, the shoulders, the elbows, the wrists, the hips, the knees, and the ankles. For our purposes of analysis of pose estimation, we focused on five points on the face; those are the nose, both eyes, and the ears. We calculated distances from the nose to selected key points, using the Euclidean distance, to formulate two triangles: a triangle based on the nose and both eyes and a second triangle based on the nose and both ears. We then calculated four angle measures based on the angles of the nose-left eye; nose-right eye; nose-left ear; nose-right ear, using the law of cosines.

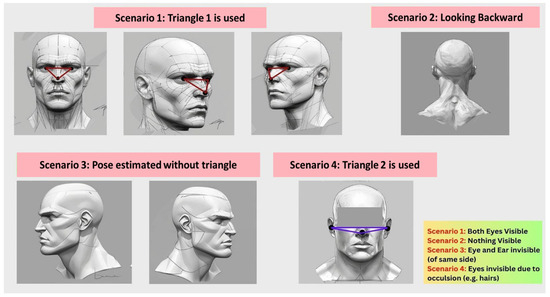

These angles were used to infer head orientation for pose estimation. An initial static threshold of 60° was effective in controlled conditions, as illustrated in Figure 5, but it exhibited limitations in real examination settings where students occupied varying orientations relative to the camera. In such cases, a fixed threshold fails to account for seating arrangements and row alignment, often leading to misclassification of head movements. To deal with this problem, a dynamic thresholding scheme was proposed. By adjusting the base threshold at 60°, in this approach, the relative orientation of the individual students to the camera was taken into account, making the individual threshold unique to each student position in the examination hall. This readjustment occurred on a per-frame basis, enabling immediate adaptation to postural and orientation changes. This kind of adaptive mechanism greatly increased the detection accuracy by matching the pose estimation to the room space configuration and different locations of the students.

Figure 5.

The figure illustrating head pose estimation: (1) estimation using Triangle 1 formed by the nose and both eyes when both eyes are visible, (2) failure of estimation when the head is turned backward and facial landmarks are obscured, (3) partial estimation without a complete triangle when one eye and ear are occluded, and (4) estimation using Triangle 2 formed by the nose and both ears when the eyes are obstructed (e.g., by hair).

Estimation of poses was based on comparisons between calculated angles and the established threshold; a threshold of more than the established threshold was considered as indicative of cheating behavior. All identified events were recorded on Google Drive, including the type of behavior, duration, time, and image of the event. It was implemented on Raspberry Pi 5 and Google Colab to test the performance of the system in various computing stack conditions. The system operates effectively on low-power hardware such as Raspberry Pi 5, and a cloud-based variant is implemented in Google Colab, and the usefulness and utility of them are demonstrated in practice in the real-time application that is being implemented in the schools.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the system distinguishes between four head orientation scenarios corresponding to typical exam-room behaviors. The forward-facing pose is considered normal behavior, representing reading or writing activities. In contrast, significant head deviations toward the left, right, or backward directions are classified as potential cheating behaviors, as they indicate attempts to view other students’ work or communicate non-verbally. To minimize false detections caused by natural movements or partial occlusions, the framework dynamically switches between two geometric references: the nose–eye triangle and the nose–ear triangle. When one or both eyes are occluded—such as by hair, hand movement, or head rotation—the system automatically relies on ear-based angle estimation, as illustrated in Figure 5. This adaptive strategy effectively prevents transient false alarms from natural behaviors such as scratching or yawning. During validation, only rare cases of short-term misclassification were observed, which are mentioned in results and discussions section. The proposed system was implemented using Python 3.10 with the Ultralytics YOLOv8 and OpenCV libraries. All experiments were conducted on a Raspberry Pi 5 (8 GB RAM) equipped with a Full HD camera (30 FPS). The entire detection and analysis pipeline operated locally on the device without GPU acceleration, which demonstrates the framework’s real-time performance on low-power hardware.

4. Results and Discussion

After the development of the proposed model, a deployment process was conducted in the educational department during the examination week to test the accuracy and performance. The system ran over several days where data were gathered to determine its efficiency. We also conducted controlled tests, in which students were asked to demonstrate cheating behaviors, allowing a direct assessment of the model’s accuracy. Deployment-based performance measures were then analysed, as explained below in relation to each principal feature of the system. Accuracy is a very important performance measure in terms of student detection because it is important to detect all the students in the examination hall. The performance results of student detection in the examination and the controlled test are shown in Table 5. At the examination stage, the model obtained a detection and precision of 96.50% and 96.08%, respectively. Detection accuracy and precision were 99.75% each under controlled testing conditions. After detecting students, we focused on detecting five facial key points that are necessary in poses. The model recognized these important points in all students with 96.29% percent accuracy. Four angles were obtained using the detected points and the law of cosine and distance formula: two angles between the nose and each eye, and two angles between the nose and each ear. Moreover, the relative angle of each student was calculated according to the sitting position, which allows more precise threshold adjustment. Table 6 shows the results of this analysis, which showed a significant increase in the accuracy and efficiency of the model

Table 5.

Performance metrics for student detection during departmental examination and dedicated testing phases.

Table 6.

Detection of facial key points and pose estimation, showing the precision of the five key points choice (eyes, ears and nose) and the angle-based calculations performed to refine threshold determination.

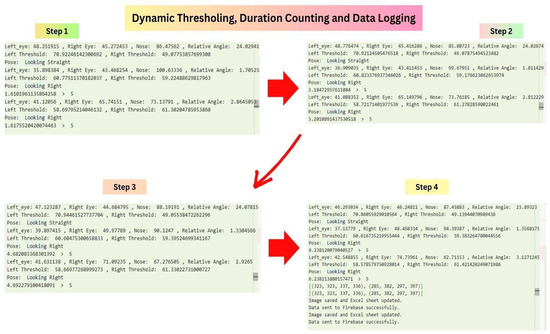

The identification of cheating behavior was done using a dynamically set threshold, as shown in Figure 6. The first thresholds were developed by testing several pose samples and later modified to support directional movements like head turns. To allow changes in position and pose, the thresholds were also refined in real time using relative angle changes. The algorithm then contrasted head orientation and gaze direction with these adaptive thresholds and declared anything more than the limit to be suspicious. The time-duration tracking mechanism was added to enhance the true detection accuracy and stability of the system and to differentiate between emergency motions and intentional activity.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the dynamic thresholding, duration tracking, and data logging pipeline for cheating detection.

The dataset used for evaluation in this study was collected from a single exam room at our site. The YOLOv8-Pose model was used in this study as-is without re-training or fine-tuning. The pre-trained model was obtained from Ultralytics and was originally trained on the COCO key points dataset, which contains extensive human poses under various settings, body shapes, and lighting conditions. Therefore, the pose estimation component has demonstrated strong generalization in our testing environment. The dataset was collected in six exam sessions that occurred at different times of day and provided a range of natural lighting. Our data observed consistent person-operations which indicate that the framework is robust to moderate changes in illumination and layout. While the dataset was collected in a single classroom, the modularity of the system supports scalable use to other environments. That is, simple changes to the operational parameters (such as recalibrating the camera angle, normalizing brightness, or fine tuning the dynamic threshold for head-turn detection) will allow the framework to use previously collected model. Future work will be to validate across multi-room datasets to test generalization between environments.

- Comparison of Static and Dynamic Thresholds

Preliminary analyses pointed towards shortcomings of fixed thresholds, which caused false positives and false negatives in the estimation of head pose. Whereas they worked well with students in the front rows, static thresholds failed for students in side rows due to differences in seating angle with respect to the camera. To solve this problem, a dynamic thresholding mechanism was applied, whereby individualised thresholds were computed and determined by the location of a student in the examination hall. This real-time correction significantly reduced misclassifications and enhanced accuracy and reliability through evaluating head motions relative to row orientation as opposed to evaluating head motions relative to the camera alone.

- B.

- Real-Time Performance

The algorithm proved to have a steady real-time performance on different platforms. Written in Python and VS Code 1.96.0 on Raspberry Pi 5, it was capable of decoding live camera video feed, and a version in the cloud on Google Colab was able to use built-in video streams. The dual-platform implementation validated the system’s generalizability and relevance to real-time examinations.

The figure shows the calculation and control of critical angles (eye-based angles and relative head orientation angle). Dynamic thresholds are used to recognize directional movement like left or right looking. Duration tracking is also added to distinguish between short, unintentional motions and deliberate ones, and a logging system logs instances of suspicious behavior longer than a predetermined time limit.

- C.

- Data Logging and Communication

The system incorporated seamless data logging and communication pipelines. Detection results were transmitted to Google Colab in real time, ensuring efficient synchronisation between the graphical interface and algorithms. Data were continuously updated on Google Drive, enabling authorised users to access results through secure email authentication. This integration improved accessibility and operational efficiency.

- D.

- Cheating Behavior Classification and Accuracy

The validation took place during the electrical department’s examination week and in a controlled testing environment. In this controlled environment, volunteer students acted out predefined cheating behaviors, which enabled thoughtful and even systematic observation of the algorithm’s performance. This dual-phase testing resulted in a strong determination of the model’s accuracy for classification.

The data in Table 7 demonstrate the algorithm’s solid performance, with an accuracy of 96.18% for detecting cheating behaviors. The performance conformed to the study’s purposes, and it demonstrated the study’s innovation for monitoring exams in real-time.

Table 7.

Performance metrics for cheating behavior detection during departmental examination and dedicated testing phases.

Frame-rate requirements vary significantly across computer vision applications. Applications such as autonomous driving, gesture tracking, or sports analytics may require high frame rates, often exceeding 30 fps in order to capture fast, continuous motion. Conversely, monitoring tasks examining slow, or deliberate human actions (e.g., surveillance, tracking students’ attendance, or monitoring student behavior in classroom settings) require much lower frame-rate and temporal resolution. In particular, prior work [24] showed that monitoring students’ head movements and identifying behavior related to cheating was possible at a frame-rate of 3 FPS. Likewise, Leon et al. [25] and Zhang et al. [26] both reported real-time embedded AI systems operating between 5 and 10 FPS on an edge device (e.g., Jetson Nano or Myriad X). Both tested real-time inference in monitoring tasks with low-quality video and low frame rates because they provided faster inference and more efficiency, and, moreover, demonstrated that low frame rates were sufficient to monitor most tasks previously studied with high-quality video. For example, our system operates at a frame-rate of 6 FPS (≈166.7 ms latency per frame) on a Raspberry Pi 5 (8 GB), with an inference model that processes and updates with new analysis frame approximately every 166.7 milliseconds. This frame-rate provided for smooth and continuous detection of posture and gaze changes throughout a single analysis period without any buffering latency, while reducing the overall computational costs and limiting power consumption.

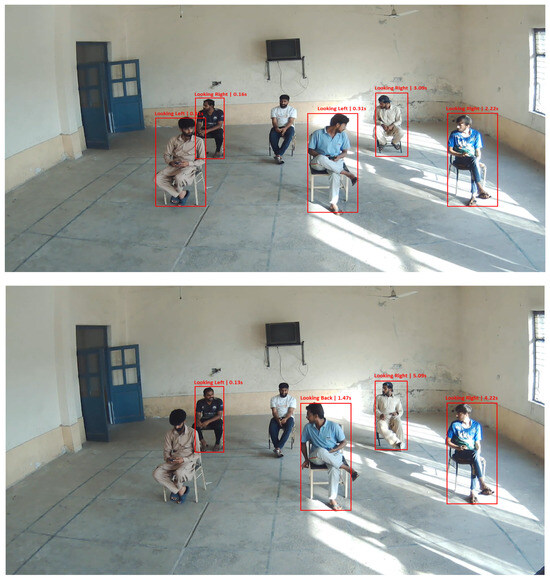

As noted in Table 8, the proposed system shows excellent inter-class discrimination, achieving an accuracy of over 95% in all categories of cheating behavior. The most prominent discriminatory errors are right versus left glances, which can be attributed to a slight head movement at the dynamic threshold near the boundary of the two regulatory states. Backward and normal poses also had few misclassifications, indicating consistent performance under common classroom conditions. Table 9 compares the accuracy and efficiency of recent models, showing that our approach achieves higher accuracy with significantly lower resource usage, validating its suitability for low-power, cost-effective real-time deployment. Figure 7 further illustrates its real-time detection capability in a deployed setting.

Table 8.

Confusion matrix for head orientation classification showing prediction accuracy across four behavioral categories.

Table 9.

Comparison of existing cheating detection models with the proposed approach, highlighting computational requirements, accuracy, and key features.

Figure 7.

Detection of students exhibiting cheating behaviors beyond a defined duration, model identifies and labels gaze directions (e.g., Looking Left, Looking Right, Looking Back) with corresponding duration values, demonstrating the model’s ability to accurately track and classify head orientations in real time.

Future Work and Limitations:

The system is effective both in terms of speed and accuracy across a wide variety of academic settings and exams. It deploys dynamic thresholding with an efficient deep learning model to precisely estimate poses and distinguish between factors contributing to cheating tendencies. However, it has several limitations. The positioning of students on the floor of the classroom, their seating distances, and a poor camera quality may disrupt threshold calibration and key-point detection, thereby causing misclassification. Other students, furniture, and/or seating position may occlude parts of the student in front of the camera and cause undetected cheating based on occlusion conditions (since behavior is typically monitored within a whole class environment). False positives may also arise from natural behavior, including yawning, glancing away, or acceptable interaction with classmates; though, the dynamic thresholding technique reduces most of these mistakes. Future enhancements might involve the incorporation of multiple cameras or depth sensors to better estimate and identify pose factors and occlusion factors, micro-expression analysis for students’ identification and/or selection of cheating behavior, and hand-tracking analysis to differentiate between voluntary and naturally occurring gestures.

Potential future improvements could include the use of multiple cameras or depth sensors to further refine and detect pose estimation and occlusion factors, micro-expression analysis to understand students’ identities and/or choices on cheating behavior, and hand-tracking analysis to discern intentional movements from naturally occurring movements. Furthermore, adaptive learning strategies could be incorporated to individualize all student learning and threshold adjustments. Despite the current limitations, the system offers a potentially scalable, non-intrusive, real-time AI solution for examination monitoring.

Future work may go beyond head-pose estimation to include other cheating variables, like using mobile devices, sharing notes, or passing material in class. The inclusion of multimodal data, including audio signals, gaze tracking, or biometric data, could further enhance system performance and help contextualize student behavior within the system’s understanding of the classroom. In addition, pose estimation could use mathematically based approaches to improve pose estimation accuracy with relative position and geometric relationships among students to mitigate some issues caused by seating arrangement and camera angles.

5. Conclusions

In this research, a new, low-computation, computer vision-based, and robust invigilation system is proposed, using pose estimation methods to identify cheating activity in exam centers. By applying YOLOv8 for student detection and pose estimation to track head and neck movements, the system successfully detects abnormal behaviors that signify cheating. The methodology demonstrated remarkable accuracy, obtaining a 96.18% success rate in real-time detection of cheating in an actual classroom scenario. The findings confirm that the suggested model performs better than classical procedures and other current solutions in terms of accuracy, reliability, computational cost, and hardware complexity. The automated system has a unique advantage over manual invigilators, who are prone to fatigue, distraction, or mistakes. In addition, the system records in-depth cheating activity logs, including the duration and timestamp, and saves them in a central repository, like Google Drive, in an open and uniform manner. Future development will focus on extending the model to identify more types of cheating, including sheet swapping and whispering, as well as gestures. The suggested system offers a promising step towards enhancing exam integrity by means of sophisticated AI-based supervision, opening the door to broader, real-time solutions in academic environments.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception, experimentation, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by partial funding from Department of EETE, UET Faisalabad Campus.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors of this article declare that this manuscript is a unique research project, and it is not concurrently under consideration for publication, nor has it been published. All of the authors contributed significantly to the work and approved the contents of the manuscript. The research adheres to the guidelines of a relevant institutional and/or national committee on human or animal research ethics. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards and regulations of the University of Engineering and Technology (UET), Lahore. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of UET Lahore, Faisalabad Campus. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants adhered to institutional, national, and international research ethics guidelines. The study involved only non-invasive visual data collection for pose estimation in a controlled examination setting. No biometric, medical, or personally identifiable information was recorded. All participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study and voluntarily provided written informed consent for participation and for the publication of anonymized images included in this article.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Each participant was briefed about the purpose of the study, the non-invasive nature of the video recording for pose estimation, and their right to withdraw at any time. Written consent was collected for participation and for the publication of anonymized images included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guerrero-Dib, J.G.; Portales, L.; Heredia-Escorza, Y.; Prieto, I.M.; García, S.P.G.; León, N. Impact of academic integrity on workplace ethical behaviour. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2020, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Arshad, J.; Ben Othman, M.T.; Hayat, M.F.; Bhatti, N.; Jaffery, M.H.; Rehman, A.U.; Hamam, H. Implementation of an intelligent exam supervision system using deep learning algorithms. Sensors 2022, 22, 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogelberg, K. Educational Principles and Practice in Veterinary Medicine; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; p. 568. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Educational_Principles_and_Practice_in_V.html?id=CnnsEAAAQBAJ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Zubair, M.; Waleed, A.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, F.; Islam, M.; Javed, S. Machine Learning Insights into Retail Sales Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 Horizons of Information Technology and Engineering (HITE), Lahore, Pakistan, 15–16 October 2024; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10777132/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Zubair, M.; Waleed, A.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, F.; Islam, M.; Javed, S. Next-Generation Healthcare: Design and Implementation of a Smart Medicine Vending System. In Proceedings of the 2024 Horizons of Information Technology and Engineering (HITE), Lahore, Pakistan, 15–16 October 2024; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10777201/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Xu, Q.; Wei, Y.; Gao, J.; Yao, H.; Liu, Q. ICAPD framework and simAM-YOLOv8n for student cognitive engagement detection in classroom. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 136063–136076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhatat, A.M.; Elsaid, K.; Almeer, S. Evaluating the efficacy of AI content detection tools in differentiating between human and AI-generated text. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2023, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Nair, R.R.; Babu, T.; Duraisamy, P. Enhancing academic integrity in online assessments: Introducing an effective online exam proctoring model using yolo. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 235, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hou, L.; Hong, J.C.; Yang, X.; Zhang, M. Impact of Face-Recognition-Based Access Control System on College Students’ Sense of School Identity and Belonging During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 808189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Liu, R.; Sokolikj, Z.; Dahlstrom-Hakki, I. Using eye-tracking in education: Review of empirical research and technology. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 1383–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethics of American Youth: 2010|Office of Justice Programs. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/ethics-american-youth-2010 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Hamlin, A.; Barczyk, C.; Powell, G.; Frost, J. A comparison of university efforts to contain academic dishonesty. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Isses 2013, 16, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Southerland, J. Engagement of Adult Undergraduates: Insights from the National Survey of Student Engagement. 2010. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/885020f967747052f313f5d6d8732c34/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- der Vossen, M.M.-V.; van Mook, W.; van der Burgt, S.; Kors, J.; Ket, J.C.F.; Croiset, G.; Kusurkar, R. Descriptors for unprofessional behaviours of medical students: A systematic review and categorisation. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhiyar, P.; Parmar, K.; Parmar, N.; Degadwala, S. Visual Distance Fraudulent Detection in Exam Hall using YOLO Detector. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Lalitpur, Nepal, 26–28 April 2023; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10134271/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Radwan, T.M.; Alabachi, S.; Al-Araji, A.S. In-class exams auto proctoring by using deep learning on students’ behaviors. J. Optoelectron. Laser 2022, 41, 969–980. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Li, X.; Xia, B.; Luo, Z. Recognition of Cheating Behavior in Examination Room Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA), Kunming, China, 25–27 June 2021; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9581122/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Malhotra, M.; Chhabra, I. Automatic invigilation using computer vision. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Integrated Intelligent Computing Communication & Security (ICIIC 2021), Bangalore, India, 4–5 June 2021; Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/iciic-21/125960815 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Alsabhan, W. Student Cheating Detection in Higher Education by Implementing Machine Learning and LSTM Techniques. Sensors 2023, 23, 4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genemo, M.D. Suspicious activity recognition for monitoring cheating in exams. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 2022, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa’a, M.; Aljazaery, I.A.; Alaidi, A.H.M. Automated cheating detection based on video surveillance in the examination classes. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2022, 16, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Menanno, M.; Riccio, C.; Benedetto, V.; Gissi, F.; Savino, M.M.; Troiano, L. An Ergonomic Risk Assessment System Based on 3D Human Pose Estimation and Collaborative Robot. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, S.; Danyaro, K.U.; Nasser, M.; Hayder, I.M.; Younis, H.A. Review of models for estimating 3D human pose using deep learning. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. Available online: https://www.academis.eu/machine_learning/_downloads/51a67e9194f116abefff5192f683e3d8/yolo.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Annannaidu, P.; Gayatri, M.; Sreeja, P.; Kumar, V.R.; Tharun, P.S.; Divakar, B. Computer Vision–Based Malpractice Detection System. In Proceedings of the Accelerating Discoveries in Data Science and Artificial Intelligence II, Vizianagaram, India, 24–25 April 2024; pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkentar, S.M.; Alsahwa, B.; Assalem, A.; Karakolla, D. Practical comparation of the accuracy and speed of YOLO, SSD and Faster RCNN for drone detection. J. Eng. 2021, 27, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, D.; Nagori, S.; Mathew, M.; Poddar, D. Yolo-pose: Enhancing yolo for multi person pose estimation using object keypoint similarity loss. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 8–24 June 2022; Available online: http://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2022W/ECV/html/Maji_YOLO-Pose_Enhancing_YOLO_for_Multi_Person_Pose_Estimation_Using_Object_CVPRW_2022_paper.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Pose-Ultralytics YOLO Docs. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/tasks/pose/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Ultralytics YOLO11-Ultralytics YOLO Docs. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo11/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Explore Ultralytics YOLOv8-Ultralytics YOLO Docs. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 5686–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarevsky, V.; Grishchenko, I.; Raveendran, K.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, F.; Grundmann, M. BlazePose: On-Device Real-Time Body Pose Tracking. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2006.10204 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Yuan, Y.; Fu, R.; Huang, L.; Lin, W.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. HRFormer: High-Resolution Transformer for Dense Prediction. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 9, 7281–7293. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, J.M.; Fernandez, F.; Ortiz, M. Real-time embedded human pose estimation using Intel Myriad X VPU on low-power platforms. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 45792–45805. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N.; Nguyen, M.; Le, T.; Huynh, T.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, T. Exploring the potential of skeleton and machine learning in classroom cheating detection. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2023, 32, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkalbani, A. Cheating Detection in Online Exams Based on Captured Video Using Deep Learning. Master’s Thesis, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, 2023. Available online: https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/all_theses/1060 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Hossain, M.N.; Long, Z.A.; Seid, N. Emotion Detection Through Facial Expressions for Determining Students’ Concentration Level in E-Learning Platform. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Information and Communication Technology, London, UK, 19–22 February 2024; Volume 1012, pp. 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, J.; Xu, J.; Bai, X.; Kaur, R.; Xia, F. Multiple Instance Learning for Cheating Detection and Localization in Online Examinations. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2024, 16, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Zhu, X. An Ensemble Learning Approach Based on TabNet and Machine Learning Models for Cheating Detection in Educational Tests. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2024, 84, 780–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).