Abstract

Air-to-ground visual target persistent tracking technology for swarm drones, as a crucial interdisciplinary research area integrating computer vision, autonomous systems, and swarm collaboration, has gained increasing prominence in anti-terrorism operations, disaster relief, and other emergency response applications. While recent advancements have predominantly concentrated on improving long-term visual tracking through image algorithmic optimizations, insufficient exploration has been conducted on developing system-level persistent tracking architectures, leading to a high target loss rate and limited tracking endurance in complex scenarios. This paper designs an asynchronous multi-task parallel architecture for drone-based long-term tracking in air-to-ground scenarios, and improves the persistent tracking capability from three levels. At the image algorithm level, a long-term tracking system is constructed by integrating existing object detection YOLOv10, multi-object tracking DeepSort, and single-object tracking ECO algorithms. By leveraging their complementary strengths, the system enhances the performance of the detection and multi-object tracking while mitigating model drift in single-object tracking. At the drone system level, ground target absolute localization and geolocation-based drone spiral tracking strategies are conducted to improve target reacquisition rates after tracking loss. At the swarm collaboration level, an autonomous task allocation algorithm and relay tracking handover protocol are proposed, further enhancing the long-term tracking capability of swarm drones while boosting their autonomy. Finally, a practical swarm drone system for persistent air-to-ground visual tracking is developed and validated through extensive flight experiments under diverse scenarios. Results demonstrate the feasibility and robustness of the proposed persistent tracking framework and its adaptability to wild real-world applications.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancements of drone technology, computer vision, and swarm collaboration technology, drone-based air-to-ground target tracking has emerged as a research hotspot in intelligent perception, with research focus progressively shifting from individual intelligence to swarm intelligence. As a cutting-edge direction in intelligent perception and collaborative control, long-term air-to-ground visual target tracking using swarm drones demonstrates growing prominence in anti-terrorism operations and disaster relief. Compared to traditional short-term tracking systems, long-term tracking requires maintaining stable and consistent target monitoring in intricate dynamic environments. For example, within anti-terrorism scenarios, sustained tracking of terrorists in challenging terrains or urban environments is imperative; in search and rescue missions, continuous tracking of trapped individuals is crucial for guiding rescue operations. Any failure to track may potentially lead to mission interruption, data loss, or even pose safety hazards. Therefore, long-term tracking capability directly determines the reliability and intelligence level of drone systems.

However, long-term robust air-to-ground visual target tracking for swarm drones still faces numerous technical challenges and engineering difficulties. At the target level, the ground environment may contain a large number of similar objects (e.g., vehicles, pedestrians), demanding the tracking algorithm with exceptional discriminative capabilities; ground targets may undergo drastic changes in appearance due to factors such as illumination variations, weather disturbances, camouflage, or active jamming, necessitating the tracking algorithm to have strong adaptability; the uncertainty of target motion exacerbates the difficulty of tracking, especially in dense obstacle environments (e.g., cities, canyons, and forests), where targets may frequently experience scale mutations, shape distortions, and occlusions, requiring the tracking system to possess powerful target re-detection capabilities rather than only relying on short-term appearance features. At the drone level, issues such as motion blur, camera jitter, drastic viewpoint changes, and rapid background switching during flight, further increase the uncertainty in target tracking and placing higher demands on the system’s tracking capabilities; drones are usually equipped with lightweight hardware and must simultaneously manage multiple tasks (e.g., flight control, target detection, target tracking, task allocation, and link communication) under limited power consumption, making it difficult to support real-time computation of complex deep learning models. Therefore, how to achieve reliable long-term tracking under limited computational resources is one of the key bottlenecks in engineering implementation.

In addition, at the swarm level, research on cooperative drone operations [1,2,3] has achieved substantial progress in areas such as path planning, task allocation, and high-precision operations. However, it continues to face numerous challenges in communication reliability, real-time and accurate intelligent decision-making, adaptability to complex environments, and large-scale swarm cooperative control. In terms of communication, issues such as communication latency and data packet loss within the swarm can significantly degrade control performance, especially in dense formations. Additionally, limitations in spectrum resources and secure communication pose serious challenges. For cooperative decision-making and path planning, task allocation in drone swarms is an NP-hard problem with high computational complexity. In distributed decision-making scenarios, multiple drones are prone to command conflicts and path collisions. Moreover, dynamic and uncertain environments impose stricter requirements for real-time path planning and obstacle avoidance. Regarding environmental adaptability, drones operating in complex settings such as urban canyons and underground spaces encounter weak GPS signals and limited sensing capabilities, which challenge situational awareness and autonomous navigation technologies. In the domain of swarm cooperative control, the current capability for formation coordination remains limited. Achieving efficient swarm cooperation under constrained conditions—such as limited communication bandwidth and incomplete sensory data—remains a significant technical challenge.

In recent years, scholars worldwide have conducted extensive research on air-to-ground visual target tracking for drones [4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, existing methods exhibit limitations when deployed in swarm drone systems. On one hand, current studies predominantly focus on theoretical verification in static environments, with insufficient research on the robustness of real-world high-dynamic air-to-ground scenarios for drones. On the other hand, existing approaches primarily enhance long-term tracking capabilities through visual algorithm design, while systemic-level investigations of persistent tracking remain scarce. Furthermore, these methods neither fully leverage drone system resources nor swarm collaboration potentials, resulting in inadequate target recovery capabilities during long-term tracking missions.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes an air-to-ground visual target persistent tracking framework for swarm drone systems. By integrating detection-tracking complementarity, geolocation-based drone spiral tracking, and relay tracking mechanisms, the framework significantly enhances the long-term tracking performance of swarm drones in high-dynamic complex scenarios. In conclusion, this paper makes the following contributions:

- We designed a multi-task asynchronous parallel long-term tracking architecture for drones by systematically balancing the computational resource constraints of drones with the real-time requirements of multiple tasks.

- We proposed a geolocation-based drone spiral tracking strategy to improve target reacquisition rates after tracking loss while breaking through the limitations of the camera field-of-view.

- We developed an autonomous task allocation algorithm and a relay tracking strategy for swarm drones to address the issue of insufficient endurance for individual drones.

- A practical swarm drone system for persistent air-to-ground visual tracking is introduced, which establishes a technical framework for deploying drone swarm systems in mission-critical applications.

The subsequent arrangement of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the related works; Section 3 first designs an multi-task asynchronous parallel long-term tracking architecture for drones, then introduces specific design details from the perspective of image algorithms, and proposes a target reacquisition strategy through geolocation-based drone spiral tracking; Section 4 proposes a relay tracking autonomous task allocation mechanism and handover strategy to further boost the long-term tracking capability from the swarm collaboration level; Section 5 develops a long-term air-to-ground tracking experimental system based on quad-rotor drones, and conducts extensive flights in diverse scenarios; Section 6 summarizes the full paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Visual Object Detection

The purpose of visual object detection is to identify and locate the objects in images. The YOLO series of object detection algorithms, which strike a balance between detection performance and computational time, are widely used in intelligent products with limited computational resources, such as mobile phones and drones. Recently, YOLOv10 [10] introduced a non-NMS training strategy that eliminates redundant predictions through dual label assignment, significantly reducing computational overhead while simultaneously enhancing detection accuracy. NFZ-YOLOv10 [11] incorporated a StarNet for lightweight feature extraction, a slim-neck structure with GSConv and VOVGSCSP modules for multi-scale feature fusion, and NWD loss to improve small target detection in infrared scenarios. YOLOv12 [12] proposed an attention-centric framework, which achieved high accuracy with competitive speed. In addition, DETR [13] proposed an end-to-end object detection by utilizing a transformer encoder–decoder architecture, which establishes the relations between the objects and the global image context and directly outputs the final predictions. DETR++ [14] investigated the methods to incorporate multi-scale features with DETR [13], and proposed a Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network, which improves the detection performance in small object detection.

2.2. Visual Object Tracking

Visual object tracking is one of the most important tasks in the field of computer vision, which aims to locate the objects within image sequences. ECO [15] introduced a factorized convolution operator, a compact generative model and a conservative model update strategy, which significantly reduced the computational complexity of proposed tracking algorithm. SiamRPN++ [16] proposed a spatial aware sampling strategy to break the spatial invariance restriction and successfully trained a Siamese tracker by ResNet architecture. STARK [17] and MixFormer [18] improved tracking performance by introducing transformer modules into the tracking network and utilizing self-attention mechanism to fuse spatiotemporal features. DeepSORT [19] introduced a ReID model to extract appearance features, combined with Kalman filtering and Hungarian algorithm to reduce the ID switching rate in multi-target tracking. ByteTrack [20] presented a generic association method by associating almost every detection box and utilized tracklet similarities of low score boxes to recover targets and filter out the false-alarms, which achieves consistent improvement especially for objects with low detection scores. Graph transformers were integrated into TransMOT [21] to model the spatial and temporal interactions, which improve the tracking speed and accuracy. MeMOTR [22] designed a customized memory-attention layer to augment long-term temporal information. SAMURAI [23] and MASA [24] were built on SAM [25] and achieved stable tracking of single and multiple targets, respectively. Refs. [26,27] are works about long-time tracking; Valmadre et al. [26] introduced the OxUvA dataset to evaluate visual long-term tracking algorithms, with an average length greater than two minutes and frequent target absences. GlobalTrack [27] was developed based on two-stage object detectors, and is capable of multi-scale and full-image search for tracking targets.

2.3. Aerial Image Object Tracking

In terms of aerial image object tracking, refs. [4,5] constructed datasets for object detection and tracking in different scenarios from a drone’s perspective, covering challenges such as changes in object size, illumination variations, object occlusion, and objects leaving the field of view, which facilitated the practical verification of tracking algorithms. Specifically, ref. [4] presented a benchmark named VisDrone2018, which consists of 263 video clips and 10,209 images with rich annotations, including object bounding boxes, object categories, occlusion, truncation ratios, etc. Ref. [5] constructed another benchmark under complex UAV which consists of about 80,000 frames and up to 14 kinds of attributes.

Ref. [6] developed a temporal embedding structure to improve the performance of object detection and multi-object tracking tasks. Ref. [7] proposed a multi-UAV cooperative system and a reinforcement learning based algorithm to improve the abilities of target tracking. Additionally, ref. [8] achieved drone collision avoidance and target tracking by a swarm-based cooperative algorithm, simultaneously. Ref. [9] proposed a decentralized multi-agent deep reinforcement learning method to improve the UAVs’ cooperation, which reshapes each UAV’s reward with a regularization term and captures the dependence between UAVs by a Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI) neural network. Ref. [1] developed a Multi-objective Multi-population Self-adaptive Ant Lion Optimizer (MMSALO) to address the limitations of single-objective optimization and insufficient constraint handling in UAV swarm task allocation.

Distinct from the existing methodologies, we place greater emphasis on algorithmic practicality. Our work systematically balances the drone computational resource constraints with real-time multi-task processing requirements and explores ways to enhance the long-term tracking capability of swarm drones for ground targets by a tri-level optimization framework: the image algorithm level, the drone system level, and the swarm collaboration level.

3. Design of Persistent Tracking System for Drones

This section presents the design of a multitask asynchronous parallel architecture that achieves efficient coordination among tasks such as detection, tracking, and control through dynamic allocation of GPU/CPU resources, effectively alleviating the contradiction between limited onboard computing resources and real-time requirements for multitasking. At the image algorithm level, a complementary detection-tracking algorithm framework is constructed, which enhances the algorithm’s long-term tracking capability by integrating the advantages of YOLOv10’s high detection rate, DeepSort’s multi-object association capability, and ECO’s real-time tracking. At the drone system level, a geolocation-based spiral tracking strategy is designed by comprehensively utilizing the drone’s state information and maneuverability, breaking through the limitations of the camera field-of-view and providing system-level support for sustained tracking missions.

3.1. Multitask Asynchronous Parallel Long-Term Tracking Architecture

Modern unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) systems must simultaneously handle multiple tasks including flight control, communication link management, target detection and tracking, navigation and path planning, as well as sensor fusion, imposing higher requirements on the real-time performance, efficiency, reliability, and scalability of onboard processors. However, constrained by factors such as payload capacity, energy consumption, and physical installation space of drones, current onboard processors generally exhibit inferior computing capabilities compared to ground-based servers. Taking into account the requirements of long-term visual target tracking missions and the constraints of on-board computational resources, this paper designs a multi-task asynchronous parallel long-term tracking architecture for drones as shown in Figure 1. The multi-task heterogeneous parallel architecture enables more efficient utilization of onboard computing resources (CPU/GPU), avoiding situations where computational resources are idle caused by task waiting dependencies. Furthermore, multi-task asynchronous parallelism not only enhances the reliability and fault tolerance of drone systems but also ensures real-time performance for critical operations such as flight control and pod control.

Figure 1.

Multitask asynchronous parallel long time tracking architecture for drones.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the entire long-term tracking system consists of six asynchronously parallel threads: Target Detection, Multi-Object Tracking, Single-Object Tracking, Flight Control, Integration, and RTSP Streaming. Specifically, the Target Detection Thread primarily executes object detection by using the GPU resources of the onboard processor and provides initial detection results to subsequent multi-object tracking pipelines. The Multi-Object Tracking Thread implements multi-object association based on the detection results and transfers the tracking results to the single-object tracking pipelines. The Single-Object Tracking Thread mainly consists of three modules: Tracking Module, Matching Module, and Decision Module. The Tracking Module is chiefly responsible for tracker initialization, state updates, and template maintenance; the Matching Module associates the single-object tracking results with multi-object tracking results; the Decision Module mainly responds to control commands from the integration thread, determines whether the tracked target is lost, and whether reinitialization is necessary. The Flight Control Thread is primarily responsible for collecting data from the equipped sensors and implementing closed-loop control based on the sensor information. The RTSP Streaming Thread predominantly encodes the processed video frames exploiting H.265 protocol and performs real-time streaming transmission. The Integration Thread principally coordinates communications between the onboard processor and other onboard hardware devices including the pod, flight controller, and communication link. Additionally, this thread needs to manage comprehensive information processing on the collected data, perform autonomous task allocation and target localization calculation, and conduct gimbal closed-loop control for persistent tracking.

3.2. Detection-Tracking Complementarity Driven Long-Term Visual Target Tracking

As shown in Figure 1, we propose an asynchronous parallel long-term tracking architecture integrating target detection, multi-object tracking, and single-object tracking. This section aims to establish a long-term object tracking framework from the perspective of image algorithms and delve into its specific implementation details. Building upon the existing YOLOv10 object detection, DeepSort multi-object tracking (MOT), and ECO single-object tracking (SOT), we have constructed a long-term tracking system by harnessing the strengths of each algorithm and complementing their deficiencies. Additionally, we have designed an adaptive initialization strategy for the single-object tracker.

3.2.1. Long-Term Image Target Tracking System

Firstly, let us analyze the respective advantages and disadvantages of YOLOv10, DeepSort, and ECO: (a) YOLO primarily utilizes GPUs for computation, achieving high target recognition accuracy, frame-wise independence, and absence of cumulative errors. However, it exhibits elevated false positive rates. (b) DeepSort requires the use of GPUs to extract deep features and uses CPUs for frame matching and filtering. Its advantages lie in integrating appearance features with kinematic models, which can be used to filter false alarms from the detector and provide reliable initial states for downstream single-object trackers. However, it relies on detection results. (c) ECO exploits CPUs for computation, offering advantages in computational efficiency and suitability for real-time closed-loop control. However, it has poor adaptability to target shape variations, suffers from cumulative error, and may experience template drift during long-term tracking.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, this study employs the YOLOv10 object detection algorithm as the front-end module and enhances detection potentiality by empirically lowering the confidence threshold to mitigate missed detections. The detection outputs are then served as inputs to the DeepSort algorithm, where its appearance feature and kinematic modeling synergistically filter false positives and unstable detections, thereby compensating for the potential impacts induced by lowering the confidence threshold while preserving detection capability. The ECO algorithm, serving as a single-object tracker, is initialized with multi-object tracking results to facilitate real-time closed-loop tracking of the target. Additionally, a rule-based correction protocol dynamically integrates multi-object tracking feedback to recalibrate the ECO tracker, effectively counteracting model drift for shape variants and occlusions. Notably, the enhanced detection performance reciprocally improves multi-object tracking accuracy through reinforced trajectory consistency and reduced ID switches.

Specifically, for object detection, we employed the M-scale YOLOv10 model and retrained it based on the officially released pre-trained model. The training dataset was collected and annotated from drone aerial-to-ground scenarios, containing five object categories: person, two-wheeler, car, truck, and tent. The input image resolution was set to 640 × 480. During onboard deployment, the model was accelerated using TensorRT. For the DeepSort multi-object tracker, we accelerated the feature extraction module with TensorRT and implemented the algorithm in C++. As for the ECO single-object tracker, we deployed a C++ version optimized with instruction set acceleration and modified the target search range to twice the target size. Other parameters were kept consistent with the official implementation.

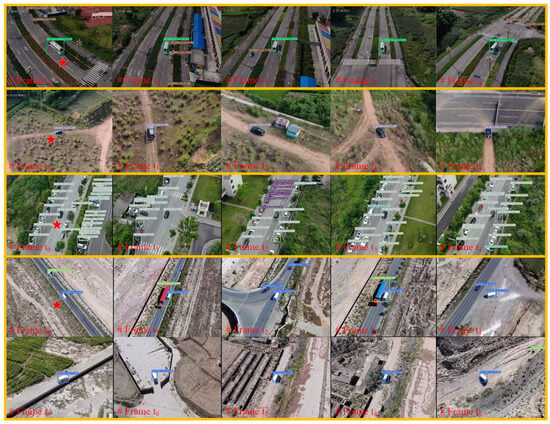

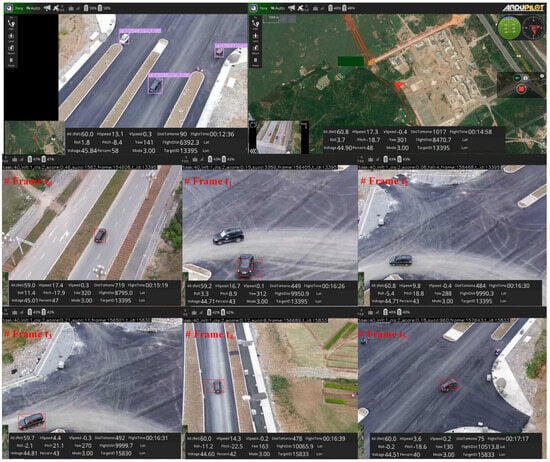

Figure 2 presents the closed-loop tracking results of drones for ground targets in diverse scenarios. The figure demonstrates the outcomes of the image processing system during four long-term tracking missions. The notation “#Frame tn” denotes the image frame number, and the red pentagram marks the mission-specific target. The results demonstrate that the proposed long-term tracking system achieves robust MOT ID consistency while performing closed-loop tracking of specific targets, and it exhibits high performance in both urban road and wilderness scenarios. Additionally, it is capable of handling challenging conditions including scale variations, target rotations, dense targets, and distractors, without observable degradation in tracking precision or stability.

Figure 2.

Visualization of long-term tracking results in different scenarios.

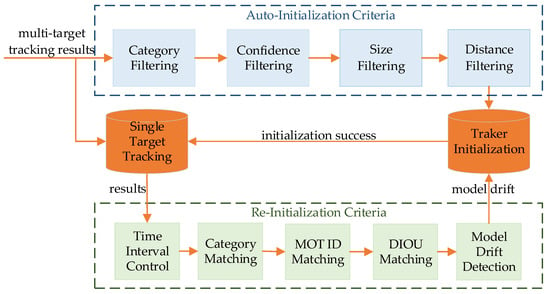

3.2.2. Adaptive Initialization Strategy for Single-Object Tracker

To fully leverage the complementary strengths of detection, multi-object tracking, and single-object tracking algorithms, we have devised an automatic initialization and reinitialization strategy for the single-object tracker, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of adaptive initialization strategy.

Firstly, the long-term tracking system utilizes the multi-target tracking results as candidate targets. An automatic selection criterion for mission-specific targets can be devised based on factors such as detection confidence, target size, object category, and distance from the image center. During actual flights, the drone system can autonomously select targets for closed-loop tracking according to the predefined criteria. Secondly, a Matching Module is incorporated into the Single-Object Tracking Thread. This module sequentially verifies MOT results against SOT outputs through three hierarchical matching steps: Category matching, MOT ID matching, and DIOU matching, ultimately yielding reliable results. Additionally, reinitialization of the tracker is triggered only when the following three conditions are simultaneously satisfied:

- Time threshold: The predefined time interval has elapsed since the last initialization.

- MOT-SOT consistency: Successful matching between the current MOT outputs and the tracked SOT target.

- Drift detection: Significant tracking drift has been identified based on the matching outcome (e.g., DIOU below 0.7).

These hierarchical strategies mitigate error propagation induced by appearance changes while ensuring stable long-term tracking. Moreover, due to the asynchronous execution of SOT and MOT threads, temporal asynchrony between the two processes must be explicitly addressed for DIOU matching and tracking drift assessment. Specifically, for DIOU matching, the DIOU distance threshold should be relaxed to accommodate minor positional deviations between bounding boxes (BBs) from temporally misaligned frames. In addition, after successful MOT-SOT target matching, centroid displacement between BBs should be excluded from tracking drift assessment, focusing solely on changes in the target’s pose and area. The drift is quantified by first aligning the centroids of the matched BBs and then calculating the IOU between them.

The proposed framework synergizes the complementary strengths of detection, MOT, and SOT algorithms, which can not only improve target detection and multi-target tracking performances but also prevent model drift in SOT, thereby achieving long-term target tracking at the image algorithm level.

3.3. Geolocation-Based Spiral Tracking for Target Reacquisition

During drone air-to-ground target tracking, complex ground environments and target behaviors may lead to challenging scenarios such as target occlusion or concealment. In such cases, existing long-term target tracking algorithms still struggle to effectively handle them, particularly for prolonged occlusion situations. To address these challenges, this paper proposes systematic approaches to enhance target reacquisition probability after tracking loss through ground target absolute localization and geolocation-based drone spiral tracking strategies.

3.3.1. Ground Target Absolute Localization

The unit line-of-sight (LOS) direction vector of the target in the camera frame can be derived from image tracking results. Denote the spatial transformation from camera frame to body frame at the current moment as ; specific values can be determined through pod servo mechanism angles and its installation parameters with the body frame. Similarly, the spatial transformation from the body frame to the ground reference frame is represented by , and its specific values can be calculated using the drone’s position and attitude parameters. If the pod incorporates a laser rangefinder and measures target distance . Then, the absolute position of the target in the ground reference frame can be represented as

However, for systems without laser rangefinders, it can be assumed that the target is located on a flat ground with a height of zero. An approximate position of the target can be estimated by using trigonometric relationships. Specifically, the coordinate representation of the target’s LOS direction in the ground reference frame can be obtained through transformation as . The absolute position of the target in the ground reference frame is then calculated as

where represents height of the drone height and denotes the vertical component of vector along the z-axis. Furthermore, in the absence of a rangefinder and the terrain is not flat, the monocular ranging methods [28,29] can be employed for target localization.

3.3.2. Geolocation-Based Drone Spiral Tracking

Based on the spatiotemporal continuity principle of physical events, when a target disappears from the image due to occlusion, its absolute position in three-dimensional space remains near the last-known location and is likely to reappear nearby, despite being temporarily unobservable from the current viewpoint. Therefore, upon detecting target occlusion or tracking failure, the line-of-sight direction of the target relative to the drone can be derived in real time based on the absolute position of both the drone and the target. This LOS direction is further converted into yaw and pitch angles relative to the electro-optical pod. Based on these angles, the pod servo is controlled to align the camera’s optical axis with the target’s absolute position, thus achieving continuous locked tracking of the target’s geographical location, waiting for the target to reappear in the image.

Additionally, the drone is systematically guided to perform spiral maneuvers around the target’s absolute location, thereby providing multiple observational perspectives and increasing the probability of finding the target. The drone’s spiral tracking trajectory is calculated in real-time based on the target’s absolute position and the drone’s flight status parameters. The spiral tracking radius is set equal to the flight altitude, and the primary control objective is to maintain the horizontal distance between the drone and the target equal to this radius, thereby enabling the drone to spiral track the target position at a predefined speed. During our flight experiments, the drone’s flight altitude was held constant, resulting in a fixed spiral tracking trajectory when tracking stationary targets. In cases where the target disappears from the field of view, the flight altitude or spiral tracking radius can be adjusted to provide observations of the target’s last known position from different perspectives. Once the target reappears, the image detection and tracking algorithms can rapidly reacquire it, thus ensuring persistent long-term tracking.

The proposed geolocation-based drone spiral tracking strategy enhances tracking robustness by integrating spatial reasoning with drone maneuver optimization, enabling the tracking system to reacquire the target from alternative angles, particularly effective in prolonged occlusion scenarios.

4. Collaborative Relay Tracking for Swarm Drones

Due to the limited flight duration of drones, an individual drone cannot achieve uninterrupted long-term tracking of ground targets. To address this issue, this section proposes a relay tracking framework from the perspective of multiple drones, further enhancing the long-term tracking capability of ground targets through swarm-level collaboration. We will discuss in detail two aspects: autonomous task allocation mechanism and relay tracking handover protocol.

4.1. Autonomous Task Allocation Mechanism

Swarm drones dynamically exchange critical state parameters through dedicated communication channels, including their respective positions , remaining battery level , mission mode , target absolute position , target category , relay tracking identifier , and task identifier . Here, the subscript denotes the drone’s serial number. The mission mode indicates the type of mission that the drone is engaged in, with 0 indicating idle, 3 indicating closed-loop tracking, and 5 indicating tracking of a specific geographic location. The relay tracking identifier defaults to 0, while 1 represents the publishing of a relay tracking task. The task identifier marks the drone’s task; if , it signifies that the current task originates from drone .

The relationship between the drone’s flight distance and power consumption can be modeled by a monotonic function . During target pursuit operations, each drone autonomously verifies whether the energy sufficiency condition is satisfied based on its current position relative to the takeoff point, by

where represents the position parameter of the drone’s takeoff point, which by default serves as the return point of drone. The threshold is set to 3 in this paper. Specifically, a relay tracking task is published when the remaining battery level of the drone falls below 3 times the power required to return to the origin. This criterion comprehensively considers three critical power consumption factors: (1) the power needed for the relay drone to fly from its current position to the target location, (2) power consumption during the relay tracking process, and (3) the power required for drone k to return. If Formula (3) is satisfied, the relay tracking identifier Rk is set to 1, thereby triggering the publishing of a relay tracking task.

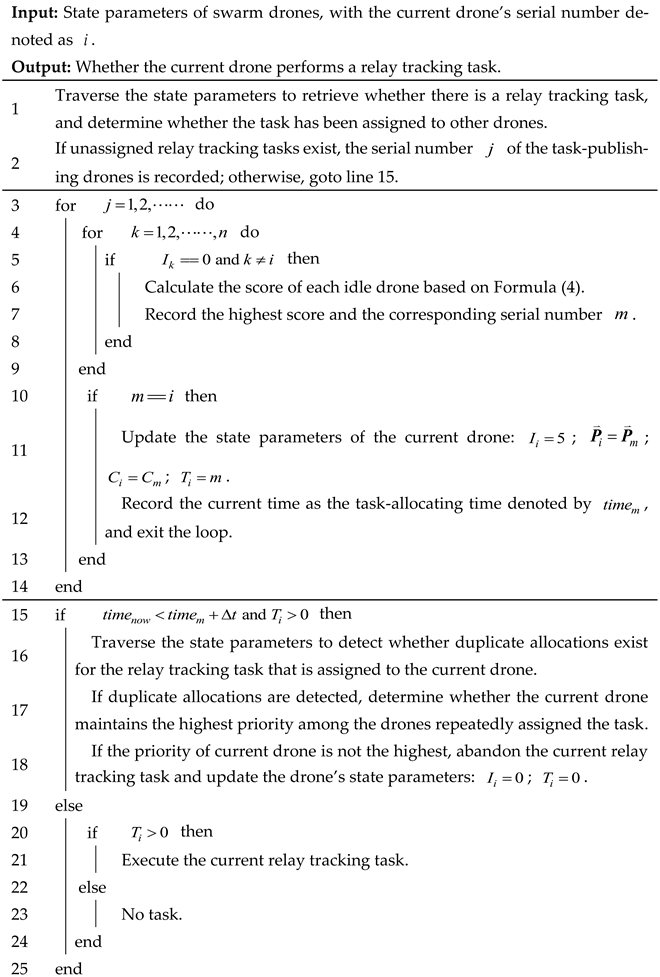

Since any drone in the cluster maintains real-time awareness of all members’ status information, enabling the swarm drones to autonomously determine whether to accept the relay tracking tasks published by other drones, in a decentralized decision-making pattern. This process is implemented within the integration thread, and the complete autonomous task allocation algorithm, along with specific details, is outlined in Algorithm 1. The workflow comprises three sequential steps: task retrieval (lines 1~2), allocation (lines 3~14), and confirmation (lines 15~25).

The allocation protocol adheres to two principles: (1) Each UAV exclusively performs task allocation for itself; (2) For each relay task, drones are ranked via a scoring metric which is calculated by incorporating their current location, battery level, and the location of the task target, and the drone with the highest score secures the task. Specifically, the scoring metric primarily considers the drone’s potential continuous tracking duration after successfully relaying. The score for drone competing for relay task is formulated as

In addition, drones involved in task allocation must possess sufficient battery reserves. Hence, the task allocation can be conceptualized as a constrained optimization problem

The constraints primarily ensure that participating drones must (1) operate in idle states and (2) exclude scenarios where a drone immediately publishes a relay task after completing a handover.

| Algorithm 1. Pseudo-code of autonomous task allocation. |

|

The third step addresses duplicate task allocations caused by communication latency, which predominantly occurs when multiple drones achieve comparable scores for the same task. The optimal resolution for such latency-induced conflicts lies in addressing them within the time domain. Specifically, following task allocation, the task allocation algorithm will continue to repeatedly confirm the assigned tasks within the subsequent duration. If duplicate allocation occurs, priority-based arbitration determines task ownership, where the drone with higher priority retains the relay tracking task. The drone’s priority can be either preset or determined solely by the drone’s serial number.

4.2. Relay Tracking Handover Protocol

Once the drone is assigned a relay tracking task, the subsequent challenge lies in how to effectively accomplish the tracking handover. This paper adopts a “handover-response” strategy inspired by relay races, achieving tracking task handover through dual operational layers. At the flight control layer, the drone first engages in real-time pursuit of target position through the flight control thread. Upon catching up the target, it transitions to a spiral tracking mode around the target’s real-time position, thereby maintaining a persistent positional lock. At the pod control layer, the integration thread governs the pod to persistently track the target’s real-time position, ensuring that the target detection thread, multi-target tracking thread, and single-target tracking thread can rapidly acquire the mission-specific target during the drone’s pursuit. To minimize the likelihood of handover errors, multi-object tracking outputs are maintained as candidates during target pursuit. The system calculates the absolute positions of each candidate and verifies candidate’s identity congruence with the published relay tracking objective. Specifically, successful matching is confirmed when the categories of the candidate and mission target are aligned, and their spatial distance remains below a predetermined threshold.

Upon successful matching, the single-object tracking thread and the pod transition to closed-loop locking mode, and the drones initiate a “handover-response” conversation by adjusting their state parameters. Specifically, the relay drone first updates its mission mode to 3, signaling “handover success” to the task-publishing drone. Upon receiving this signal, the task-publishing drone responds by resetting the relay tracking identifier to 0, indicating “task closed”. Once the relay drone detects this “task closed” status, it resets the task identifier to 0, thereby completing the handover process. This automated handshake mechanism ensures uninterrupted long-term tracking continuity while preventing redundant tracking conflicts.

5. Experiments

To demonstrate the feasibility and robustness of the proposed tri-level optimization framework, a long-term tracking system for air-to-ground visual targets using a swarm of quad-rotor drones was established, and flight tests were conducted under various scenarios.

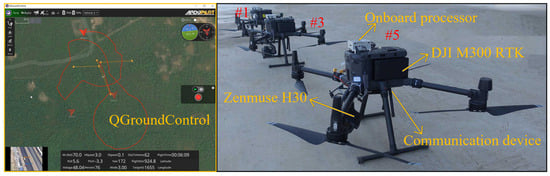

5.1. Swarm Drones Experimental System Design

This paper presents a quad-rotor drone-based air-to-ground visual target persistent tracking system developed through DJI M300 RTK (manufactured by DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and QGroundControl (https://github.com/mavlink/qgroundcontrol (accessed on 10 August 2025)) integration. As illustrated in Figure 4, the architecture comprises five core subsystems: (1) flight platform, (2) electro-optical pod, (3) communication datalink, (4) onboard processor, and (5) ground control software, with triplicate drone systems employed to validate the swarm autonomous task allocation algorithms and the relay tracking handover protocol.

Figure 4.

Quad−rotor drone−based air−to−ground visual target persistent tracking system.

Specifically, DJI M300 RTK serves as the flight platform, enabling secondary development for drones, encompassing the acquisition of drone state parameters and drone control. We implemented custom flight autonomy through secondary development, achieving autonomous takeoff, waypoint navigation, dynamic target pursuit, geolocation-based spiral tracking, and low-battery return protocols. Zenmuse H30 (manufactured by DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) functions as the onboard electro-optical pod. It was reprogrammed for real-time image acquisition with adaptive focal length control. Additionally, closed-loop locking of the mission target was achieved through servo mechanism control. HQ010-BY (manufactured by Huoqilin Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) is employed as the communication datalink, facilitating communication with the onboard processor through the network port and enabling the reception of messages transmitted by other HQ010-BYs within the network. QGroundControl is utilized as the drone ground control software, enabling operations such as automatic trajectory planning, swarm control, parameter uploading, and image data streaming. The iCrest onboard processor, tailored for DJI drones, incorporates an NVIDIA JETSON Xavier NX (manufactured by NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA) as the GPU module, boasting a computing power of up to 21 TOPS, within which we implement the six asynchronously parallel threads as detailed in Figure 1.

Additionally, to ensure the real-time performance of the mission, we accelerated the target detection and multi-object tracking algorithms exploiting the TensorRT during deployment, and improved the single-object tracking speed by reducing the search region to twice the target size. The onboard image processing results were hardware-encoded via the NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX and then streamed to the RTSP server. The ground station subsequently retrieved these processed images through RTSP streaming. With the above optimizations, our system finally achieves a detection rate of about 20 fps and a tracking rate of about 25 fps. For communication, the MAVLink communication protocol was employed for the QGroundControl and drones to transmit and receive ground control commands and status information of individual drones through the UDP network protocol.

5.2. Results and Discussion

Based on the aforementioned drone system, we conducted extensive flight experiments under various scenarios. The following results demonstrate the improvements of the proposed methodologies and strategies on prolonged ground target tracking missions through three dimensions: image processing algorithms, drone system strategies, and swarm collaboration mechanisms.

5.2.1. Long-Term Tracking Results of Image Targets

As the object detection task, multi-object tracking task, single-object tracking task, and drone control task operate within asynchronous parallel threads; the drone system can simultaneously acquire the outcomes from these tasks, as illustrated in Figure 5. The top-left panel demonstrates the multi-object tracking IDs (denoted as “id”), detected object categories (e.g., “car”), and the numerical values following the category represents the target detection confidence scores (range: [0, 1]). The top-right panel presents a screenshot of the QGroundControl interface during target pursuit operations, displaying the real-time drone states including geospatial position, attitude angles, velocity, battery level, flight duration, and the currently tracked target ID. The lower two panels in Figure 5 show the results of the single-object tracking algorithm during drone tracking missions. The red bounding box indicates the ECO tracker’s output, accompanied by detailed state parameters: initialization status, target category, tracking confidence score, continuous successful tracking frames, frame ID, and corresponding multi-object tracking ID.

Figure 5.

Visualization of detection and multi−object tracking (top left panel), drone control (top right panel) and the processes of single−object long−term tracking (from #Frame t0 to #Frame t5).

As illustrated in Figure 5, during the tracking process, a sharp turn induces significant appearance variations in the target (#Frame t1). However, the ECO tracker fails to adapt to these changes, resulting in a gradual drift in the tracking results and ultimately leading to tracking failure (#Frame t2). Once the target is lost, the target matching module retrieves it based on its previous state and the multi-object tracking results (#Frame t3), and reinitializes the ECO tracker using the retrieval results. When tracking drift is detected by Matching Module and Decision Module (#Frame t4), the single-object tracking thread corrects the ECO tracker based on the matching results (#Frame t5). Furthermore, Figure 2 demonstrates the drone system’s long-term tracking results across diverse air-to-ground scenarios.

The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed detection-tracking complementary long-term tracking framework can effectively handle challenging scenarios including size variations, target rotations, and target loss reacquisition, and exhibits strong robustness in high-dynamic and complex air-to-ground scenarios for drones.

5.2.2. Geolocation-Based Spiral Tracking Results

Figure 6 illustrates the tracking results during drone spiral pursuit operations against the ground target. During the tracking process, the single-object tracking thread continuously locates the targets in image sequences and transmits the tracking results to the integration thread. The integration thread then calculates the geographical location of the target based on the states of the drone and pod, using Formulas (1) or (2), and sends the corresponding position to the flight control thread, while controlling the pod to lock onto the mission target. Upon receiving the tracking mission and the real-time geographical location of the target, the flight control thread governs the drone to track the geographical location of the target and performs spiral tracking with a 50 m (approximating the flight altitude) radius once it catches up with the target.

Figure 6.

Geolocation-Based drone spiral tracking (left panel) and single-object tracking results during the drone chasing the geographic location of the target (from #Frame t0 to #Frame t3).

The QGroundControl interface snapshot in the left panel of Figure 6 shows the drone performs a spiral tracking mode around a stationary target. While the four panels on the right show the image tracking results during the drone’s spiral tracking. As can be seen from the images, the mission target is parked close to a bus, and the drone spiral tracking provides multi-perspective observation, enhancing the adaptability of tracking. Furthermore, this strategy can also be employed in scenarios where tracking fails due to occlusions. By spiral tracking the geographical location of the target, it breaks through the limitations of the camera field-of-view and increases the target reacquisition rate for tracking failures.

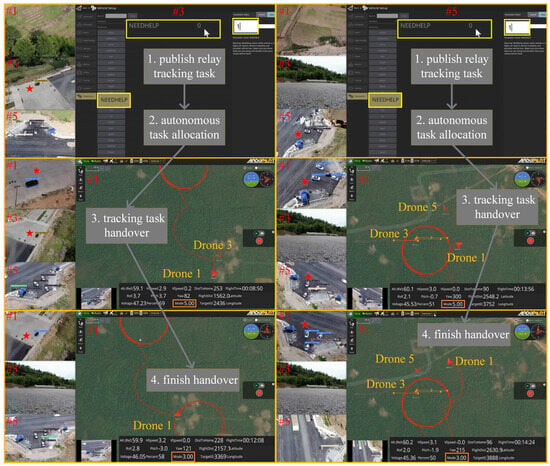

5.2.3. Collaborative Relay Tracking Results

Figure 7 demonstrates two complete cycles of autonomous task allocation and tracking handover executed sequentially by 3 quad-rotor drones within a single mission. Specifically, the swarm collaborative relay tracking process comprises four operational stages: (1) publish relay tracking task; (2) autonomous task allocation; (3) tracking task handover; (4) finish handover. Identifiers #1, #3, and #5 represent the serial numbers of the drones, and the red pentagrams indicate the mission targets. The left column panels in Figure 7 show the process where drone #3 publishes a relay task to track a black car, while drone #1 is assigned the relay tracking task and completes the tracking task handover with drone #3. Similarly, the right column panels in Figure 7 demonstrate the process where drone #5 publishes a relay task to track a white car, while drone #1 is assigned the relay tracking task again and finishes the tracking task handover with drone #5.

Figure 7.

Autonomous task allocation and static tracking task handover results of three quad-rotor drones. The left column panels illustrate the handover workflow between drone #3 and drone #1, and the handover workflow between drone #5 and drone #1 is depicted in the right column panels subsequently.

To facilitate the validation of autonomous task allocation Algorithm 1, we implemented a human-in-the-loop verification mode in QGroundControl, where manual relay tracking task triggering is achieved by modifying the drone’s “NEEDHELP” state parameter from 0 to 1, as shown in Figure 7. This design enables drones to freely publish the current tracking mission as a relay tracking task without considering formula (3). As shown in the top-left panel, both drone #3 and drone #5 are tracking the corresponding mission targets, whereas drone #1 remains idle. Consequently, upon drone #3 publishing a relay task, drone #1 is promptly assigned the relay tracking task. After being assigned the relay tracking task, drone #1 updates its mission mode to 5, simultaneously controlling the drone to chase the geographical location of the target, steering the pod towards the target’s geographical location, and adaptively adjusting the camera focal length based on the relative distance between the drone and target, as illustrated in the middle-left panel. Upon completing the task handover, drone #1 resets its mission mode to 3 and continues tracking the target, whereas drone #3 returns to the takeoff point due to low battery power, as depicted in the bottom-left panel. Moreover, in the top-right panel of Figure 7, drone #1 and drone #3 are idle, but drone #3 is in a low battery state, while drone #5 is actively tracking the target. Similarly, when the QGroundControl software triggers drone #5 to publish a relay tracking task, drone #1 assigns the task and ultimately completes the task handover with #drone 5, as shown in the middle-right and bottom-right panels.

The experimental results presented in Figure 7 validate the feasibility of the autonomous task allocation algorithm and handover strategy. However, both relay tracking tasks were accomplished when the targets remained stationary. Compared to dynamic handover scenarios, stationary target tracking task handover proves more tractable due to two critical operational advantages: (1) The precision of the target’s geographical location is enhanced after low-pass filtering when the target is stationary; (2) A stationary target can mitigate the impacts of processing latency and communication delay.

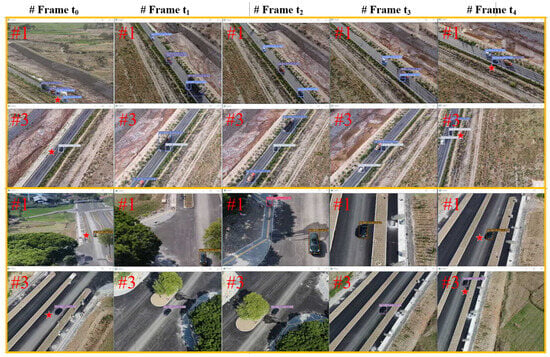

Figure 8 illustrates the complete relay tracking processes of moving targets by drone #1 and drone #3 under two distinct scenarios. Markers #1 and #3 represent the drone serial numbers, and #Frame t0~#Frame t4 denote the frame numbers of corresponding images. As shown in the figure, the target for both tracking missions is a black car, indicated by red pentagrams. Drone #3 publishes the relay tracking task while drone #1 is assigned this task. Once assigned the relay tracking task, drone #1 chases the target’s geographical location in real-time, and controls the pod to point towards the location. As can be seen from the figure, during the first half of the task handover (#Frame t0~#Frame t2), the target is not in the center of the image in drone #1’s view. This is due to the inaccurate calculation of the target’s geographical location and time delay, as well as drone #1 being relatively far from the target. However, as the distance between drone #1 and the target continues to decrease, the target gradually approaches the center of the image (#Frame t3), and finally, drone #3 completes the handover of the tracking task (#Frame t4).

Figure 8.

The processes of dynamic tracking task handover in two scenarios. First, drone #3 publishes a relay tracking task; then, drone #1 assigns this task and completes task handover (from #Frame t0 to #Frame t4).

Summarizing the experimental results above, this paper established a long-term tracking test system for air-to-ground visual targets utilizing triplicate drones and conducted extensive flight tests. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed detection-tracking complementary long-term tracking framework, geolocation-based drone spiral tracking strategy, and relay tracking mechanism enhance the long-term tracking capability of mission targets from the perspectives of algorithms, individual drones, and swarm drones, respectively.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the air-to-ground visual target persistent tracking challenge in drone swarms. By systematically balancing the computational resource constraints of drones with the real-time requirements of multiple tasks, a multi-task asynchronous parallel long-term tracking architecture for drones is designed. This architecture effectively enhances the image target tracking capability in drone scenarios while ensuring the real-time performance of each task. Additionally, A geolocation-based drone spiral tracking strategy is proposed to improve target reacquisition rates after tracking loss while breaking through the limitations of the camera field-of-view. Furthermore, an autonomous task allocation algorithm and a relay tracking strategy for swarm drones are designed to address the issue of insufficient endurance for individual drones. Finally, a practical swarm drone system for persistent air-to-ground visual tracking is developed, which achieves a detection rate of about 20 fps and a tracking rate of about 25 fps. Through comprehensive scenario testing, our framework demonstrates robust persistent tracking capabilities in heterogeneous environments, establishing both a theoretical foundation and a technical framework for deploying drone swarm systems in mission-critical applications including counter-terrorism operations, disaster relief, and other emergency response operations.

Nevertheless, this study has not yet fully addressed issues such as online learning of new targets, real time multi-target tracking of dense targets, sensor data alignment for swarm drones, fusion of multi-modal perception information, multi-drone collaborative localization, and inter-drone target re-identification. Future work will focus on these aspects to further improve the intelligent collaborative capabilities of drone swarms in complex environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and H.Y.; methodology, Y.X.; software, Y.X.; validation, H.Y., A.W. and H.S.; formal analysis, Y.X. and A.W.; investigation, Y.M.; resources, S.G.; data curation, H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, T.Y.; visualization, T.Y.; supervision, Y.M.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Science and Technology Innovation 2030 Major Project, grant number 2020AAA0104801.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| SOT | Single Object Tracking |

| MOT | Multi-Object Tracking |

| LOS | Line Of Sight |

| IOU | Intersection Over Union |

| DIOU | Distance-Intersection Over Union |

References

- Li, C.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Yang, G.; Liu, K.; Diao, X. Cooperative Task Allocation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Swarm Using Multi-Objective Multi-Population Self-Adaptive Ant Lion Optimizer. Drones 2025, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W.; Chen, C.; Amoon, M. Variable Grid-Based Path-Planning Approach for UAVs in Air-Ground Integrated Network. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2025, 36, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanay, K.; Raktim, B. Robust Attitude Control of Nonlinear Multi-Rotor Dynamics with LFT Models and H∞ Performance. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.00208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Ling, H.; Hu, Q. VisDrone-DET2018: The Vision Meets Drone Object Detection in Image Challenge Results. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2018 Workshops; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Qi, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, Y.; Duan, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. The Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Benchmark: Object Detection and Tracking. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Gao, W.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. Multiple Object Tracking of Drone Videos by a Temporal-Association Network with Separated-Tasks Structure. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Du, J.; Jiang, C.; Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, G. Multi-UAV Cooperative Target Tracking Based on Swarm Intelligence. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–23 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Leng, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Q. Intelligent UAV Swarm Cooperation for Multiple Targets Tracking. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Shen, L. Improving multi-target cooperative tracking guidance for UAV swarms using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 38th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, A.; Peng, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, W.; Feng, X.; Ren, D. NFZ-YOLOv10: Infrared Target Detection Algorithm for Airport Control Zones. Infrared Technol. 2025, 47, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; David, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, C.; Francisco, M.; Gabriel, S.; Nicolas, U.; Alexander, K.; Sergey, Z. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Zang, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, H.; Song, X.; Chen, J. DETR++: Taming Your Multi-Scale Detection Transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.02977. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Bhat, G.; Khan, F.S.; Felsberg, M. ECO: Efficient Convolution Operators for Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE CVPR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6931–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, F.; Xing, J.; Yan, J. SiamRPN++: Evolution of Siamese Visual Tracking With Very Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF CVPR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 4277–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Peng, H.; Fu, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, H. Learning Spatio-Temporal Transformer for Visual Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF ICCV, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10428–10437. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, L.; Wu, G. MixFormer: End-to-End Tracking with Iterative Mixed Attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF CVPR, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13598–13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICIP, Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3645–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. ByteTrack: Multi-object Tracking by Associating Every Detection Box. In Proceedings of the ECCV; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Volume 13682. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, P.; Wang, J.; You, Q.; Ling, H.; Liu, Z. TransMOT: Spatial-Temporal Graph Transformer for Multiple Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF WACV, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023; pp. 4859–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Wang, L. MeMOTR: Long-Term Memory-Augmented Transformer for Multi-Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF ICCV, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 9867–9876. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Huang, H.; Chai, W.; Jiang, Z.; Hwang, J. SAMURAI: Adapting Segment Anything Model for Zero-Shot Visual Tracking with Motion-Aware Memory. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.11922. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ke, L.; Martin, D.; Luigi, P.; Mattia, S.; Luc, V.; Fisher, Y. Matching Anything by Segmenting Anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.; Eric, M.; Nikhila, R.; Mao, H.; Chloe, R.; Laura, G.; Xiao, T.; Spencer, W.; Alexander, C.; Wan, Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, V.; Luca, B.; João, F.; Ran, T.; Andrea, V.; Arnold, S.; Philip, T.; Efstratios, G. Long-term Tracking in the Wild: A Benchmark. In Proceedings of the ECCV, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 692–707. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, X.; Huang, K. GlobalTrack: A Simple and Strong Baseline for Long-term Tracking. In Proceedings of the National Conference on AAAI, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yang, S. Videometrics: Principles and Researches; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2009; pp. 22–77. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Mao, Z.; Yao, T.; Yan, H.; Ma, Y.; Song, H.; Huang, H. PCA-based monocular vision target state estimation in UAV air-to-ground scenarios. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Image Processing and Intelligent Control (IPIC 2025), Qingdao, China, 9–11 May 2025; p. 1378209. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).