Dynamic Tuning of PLC-Based Built-In PID Controller Using PSO-MANFIS Hybrid Algorithm via OPC Server

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Contributions

- Hybrid PSO–MANFIS Tuning Framework: A novel hybrid algorithm that combines the global optimization capability of PSO with the adaptive learning of MANFIS is proposed to tune PLC-based built-in PID parameters dynamically in real time.

- Real-Time MATLAB–PLC Integration: Unlike previous studies that rely solely on simulation environments, this study achieves practical real-time tuning through OPC-based communication between MATLAB and Siemens PLC hardware.

- Dynamic Industrial Implementation: The proposed method is experimentally validated using a real industrial setup (Siemens S7-300 PLC, VFD, and asynchronous motor), demonstrating improved rise time, settling time, and overshoot compared to both MATLAB-tuned and MPC-based controllers.

- Enhanced Adaptability and Robustness: The hybrid controller effectively handles nonlinear and time-varying process dynamics, achieving better adaptability and transient performance than traditional PID and predictive control approaches.

1.2. Paper Organization

2. System Design and Implementation

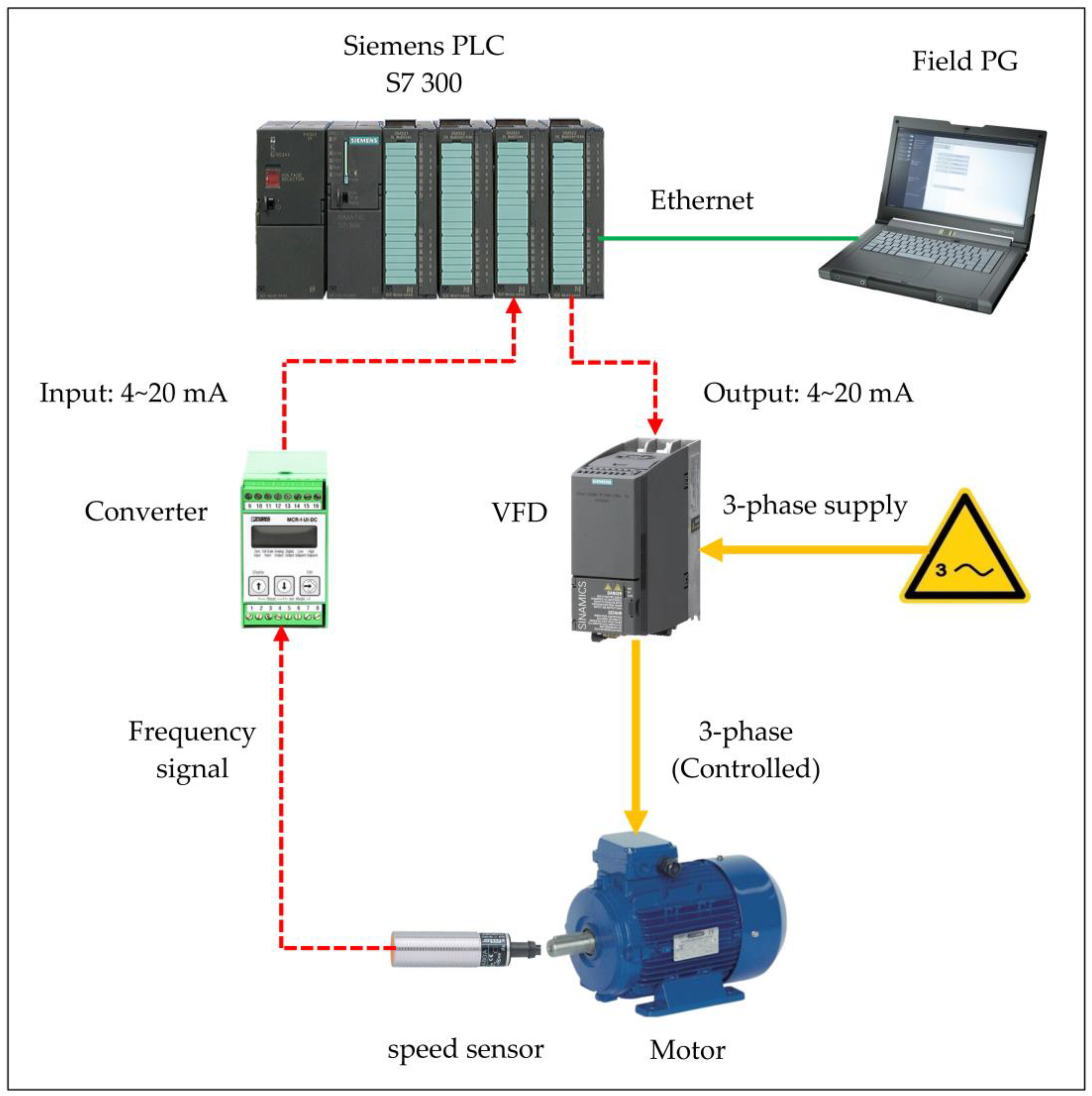

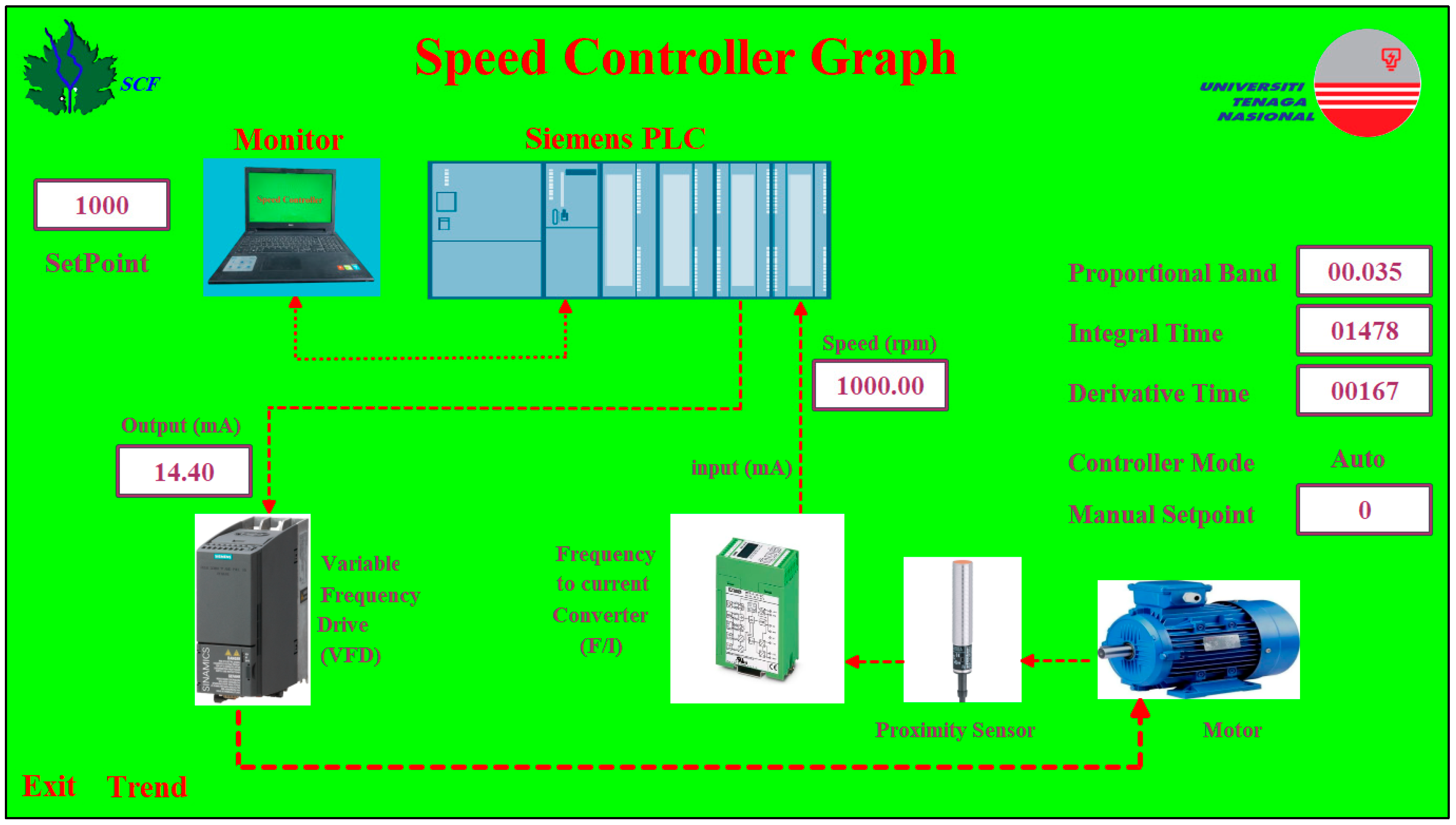

2.1. Hardware Configuration and Data Acquisition

2.1.1. Speed Controller Components

- Control panel

- 2.

- Sensor

- 3.

- Converter

- 4.

- Variable Frequency Drive (VFD)

- 5.

- Motor

- 6.

- Monitor

2.1.2. Methodology

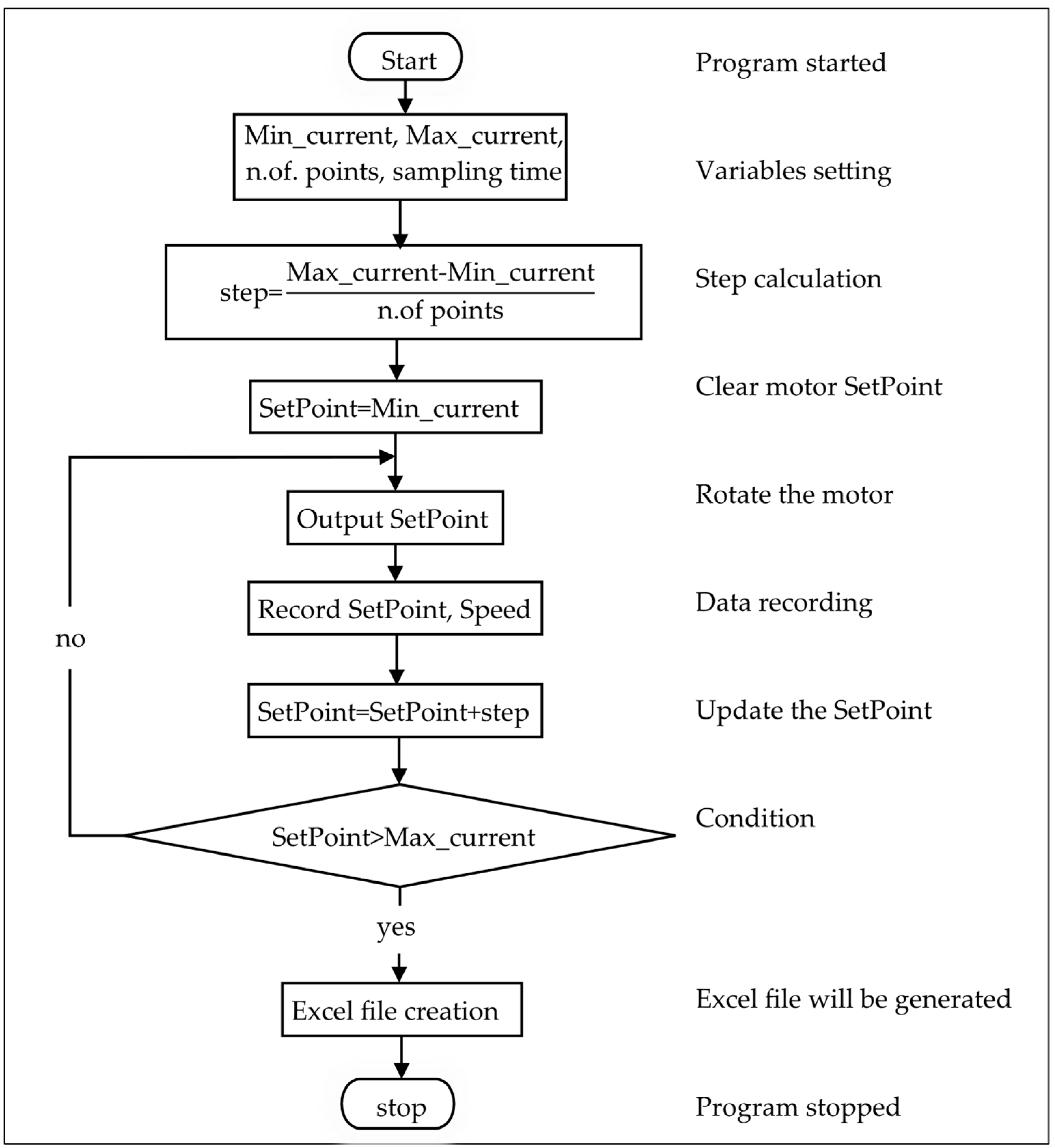

- Open-Loop Data Recording.

- System Modeling and Process Identification.

- Initial PID Controller Design.

- Design of Siemens Speed Controller in TIA Portal V18.

- Development of the PSO-MANFIS Hybrid Tuner.

- MATLAB-PLC Integration via OPC Server.

- Performance Evaluation.

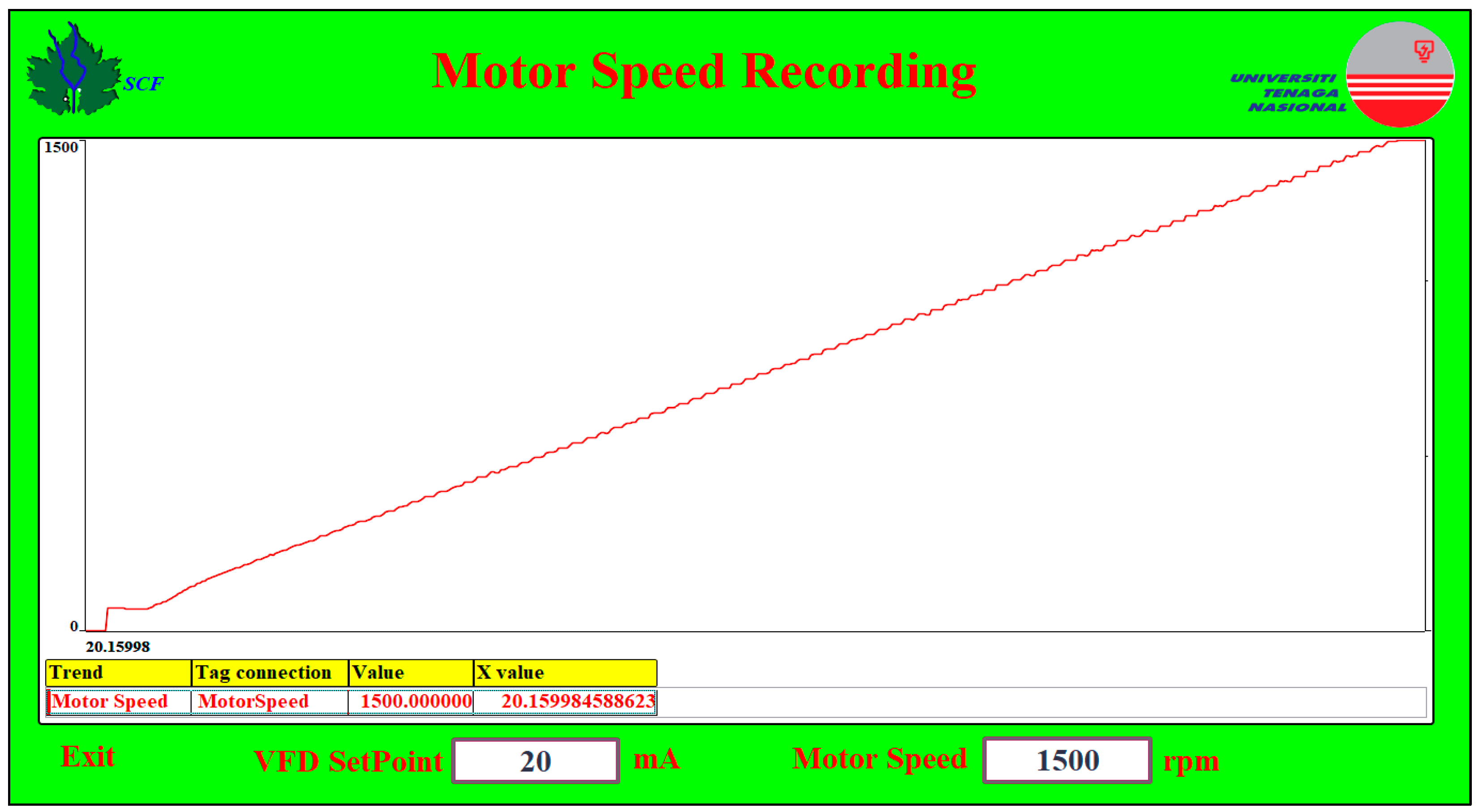

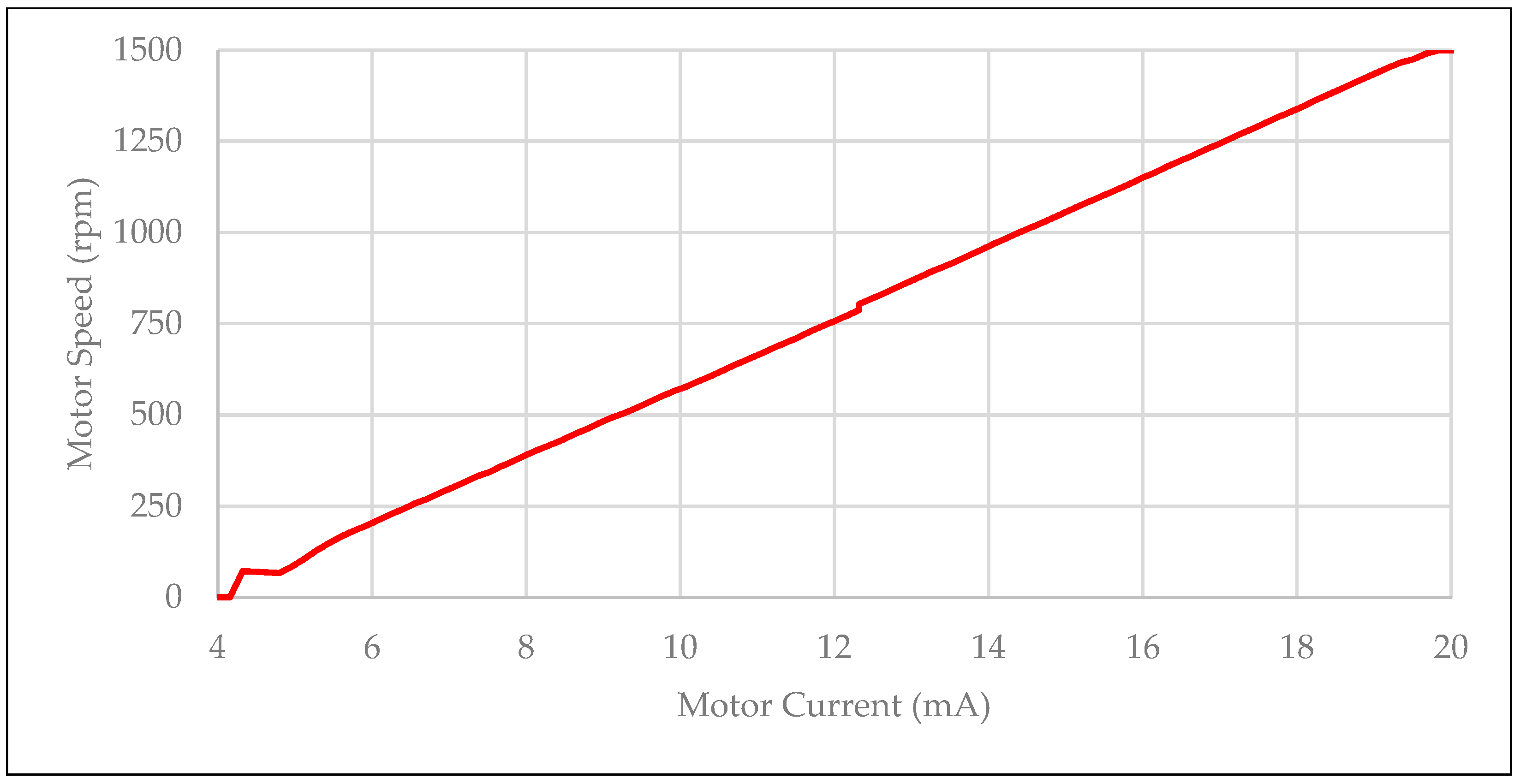

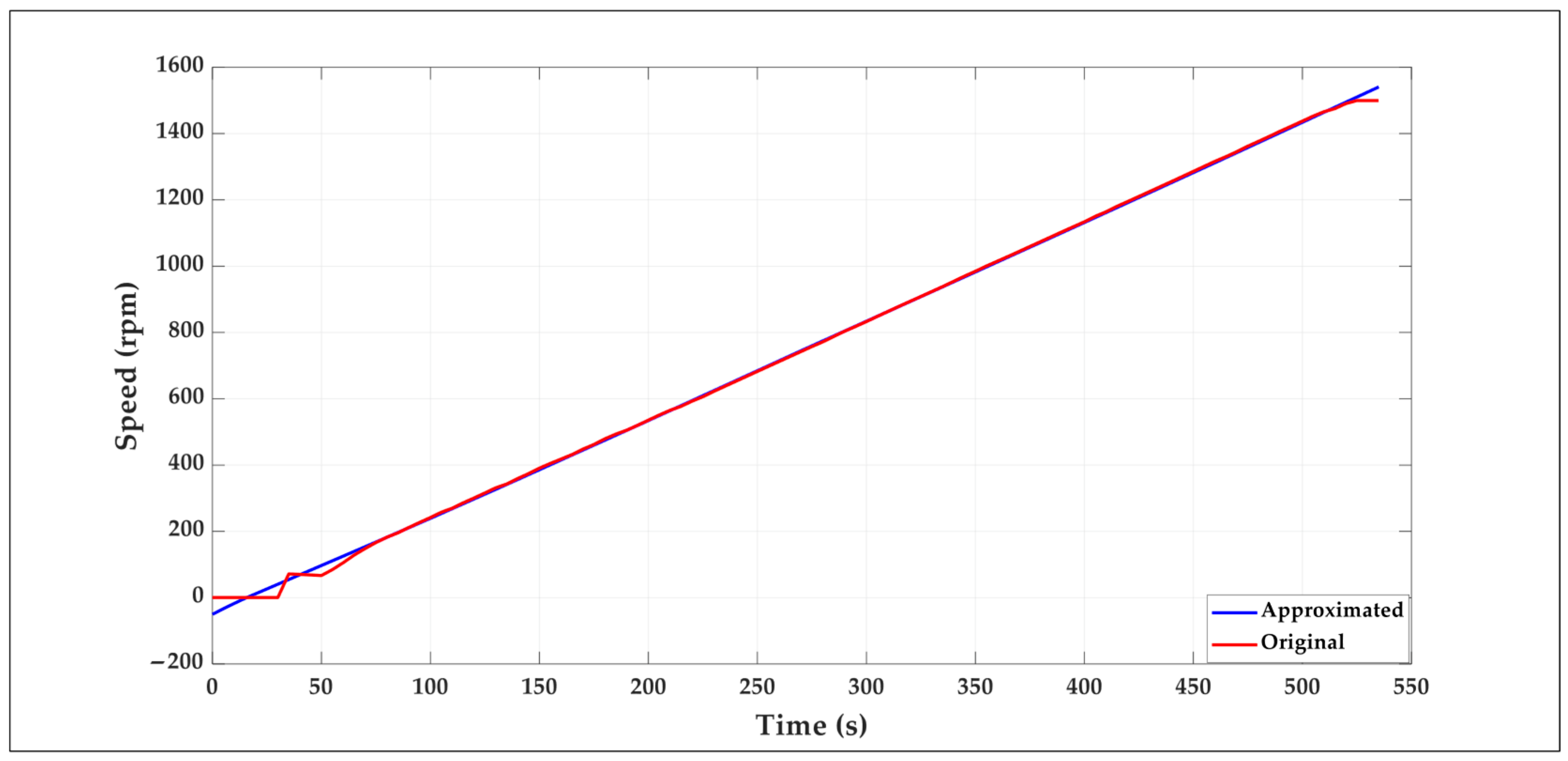

2.1.3. Data Recording and System Modeling

- Real-time open-loop data recording.

- 2.

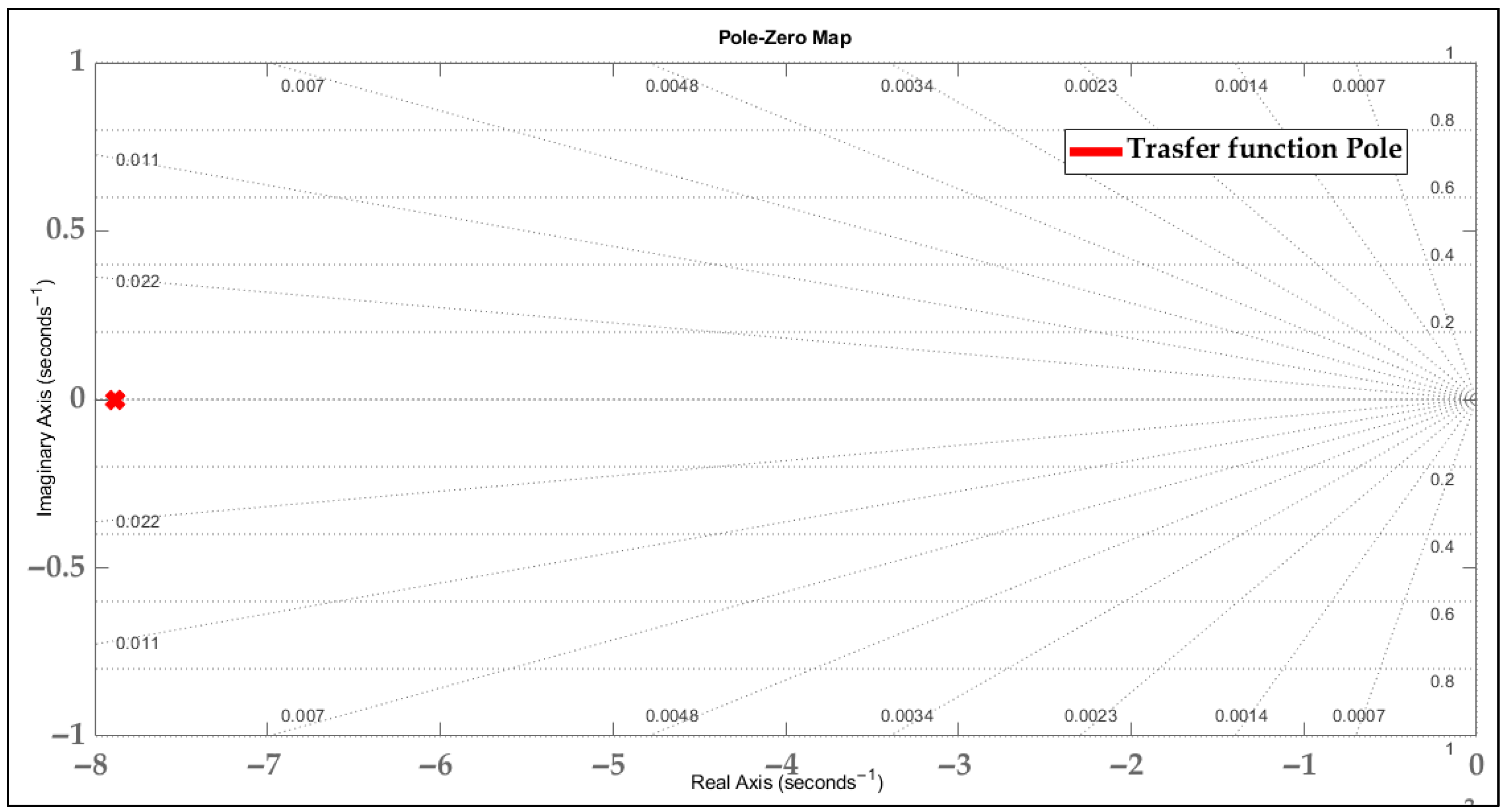

- System model (transfer function) finding.

2.2. Reference PID Tuning Using MATLAB

2.2.1. Introduction

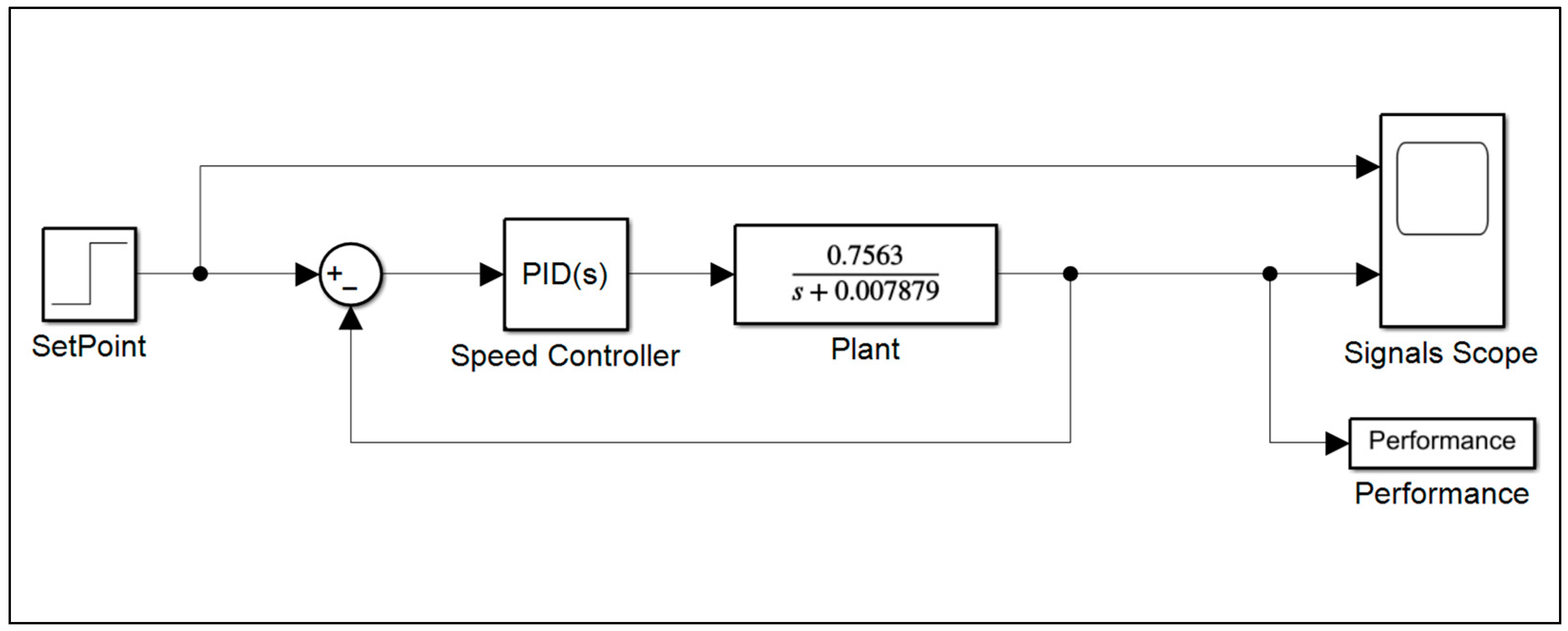

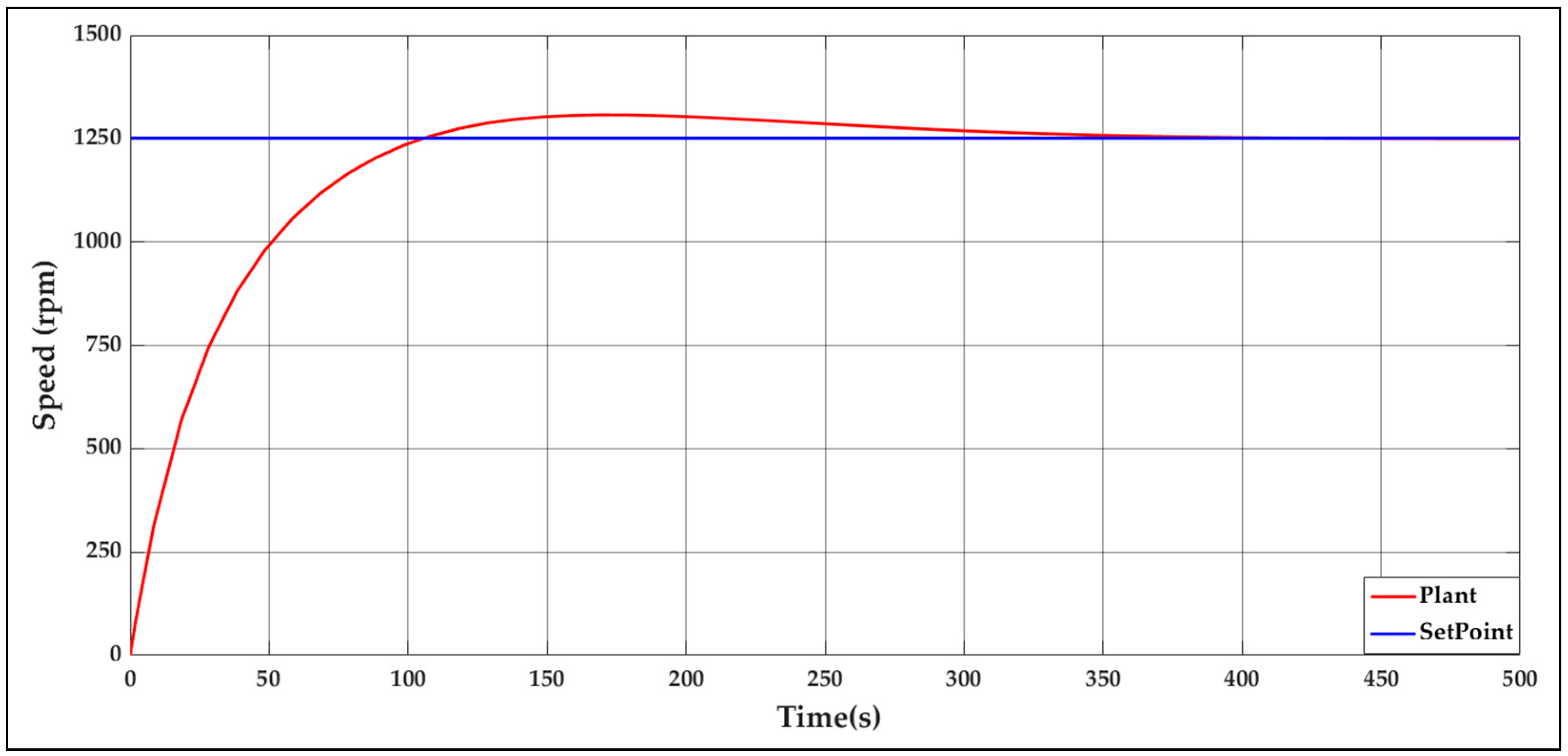

2.2.2. MATLAB Tuner

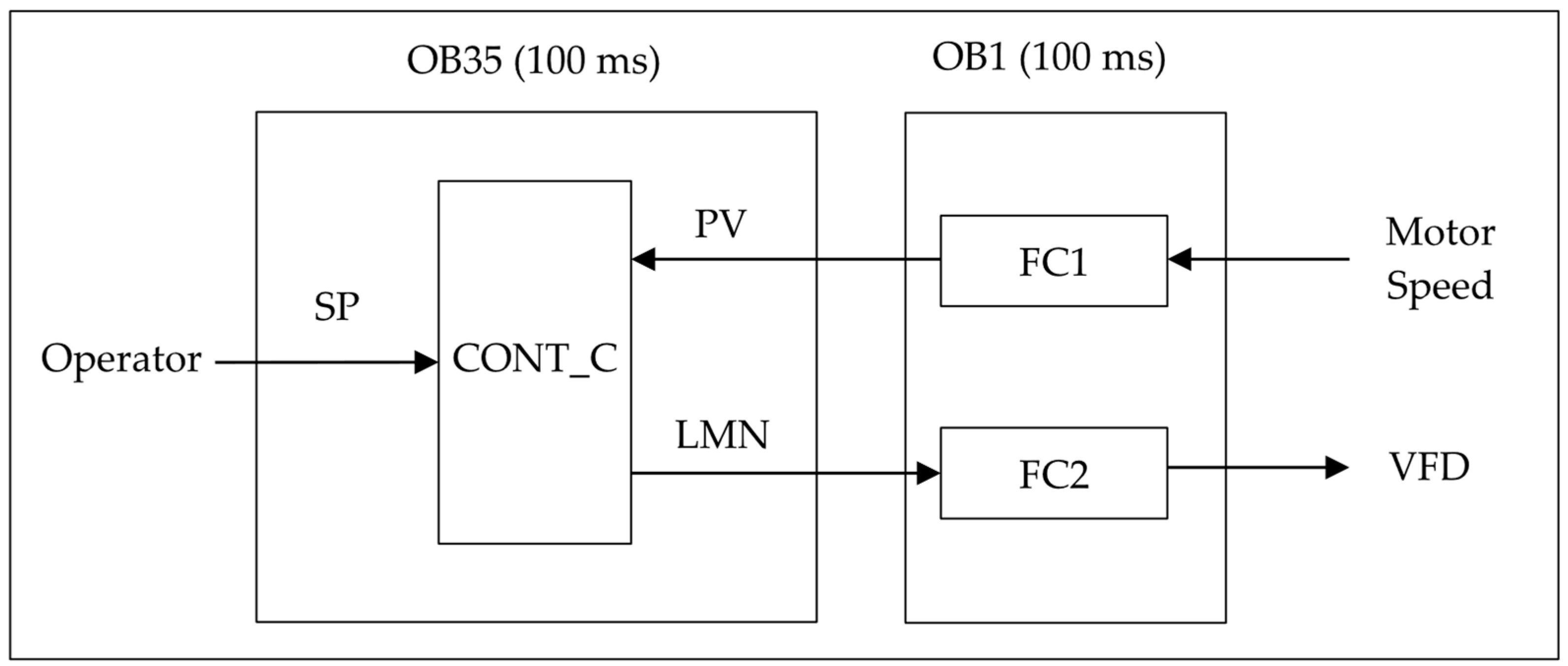

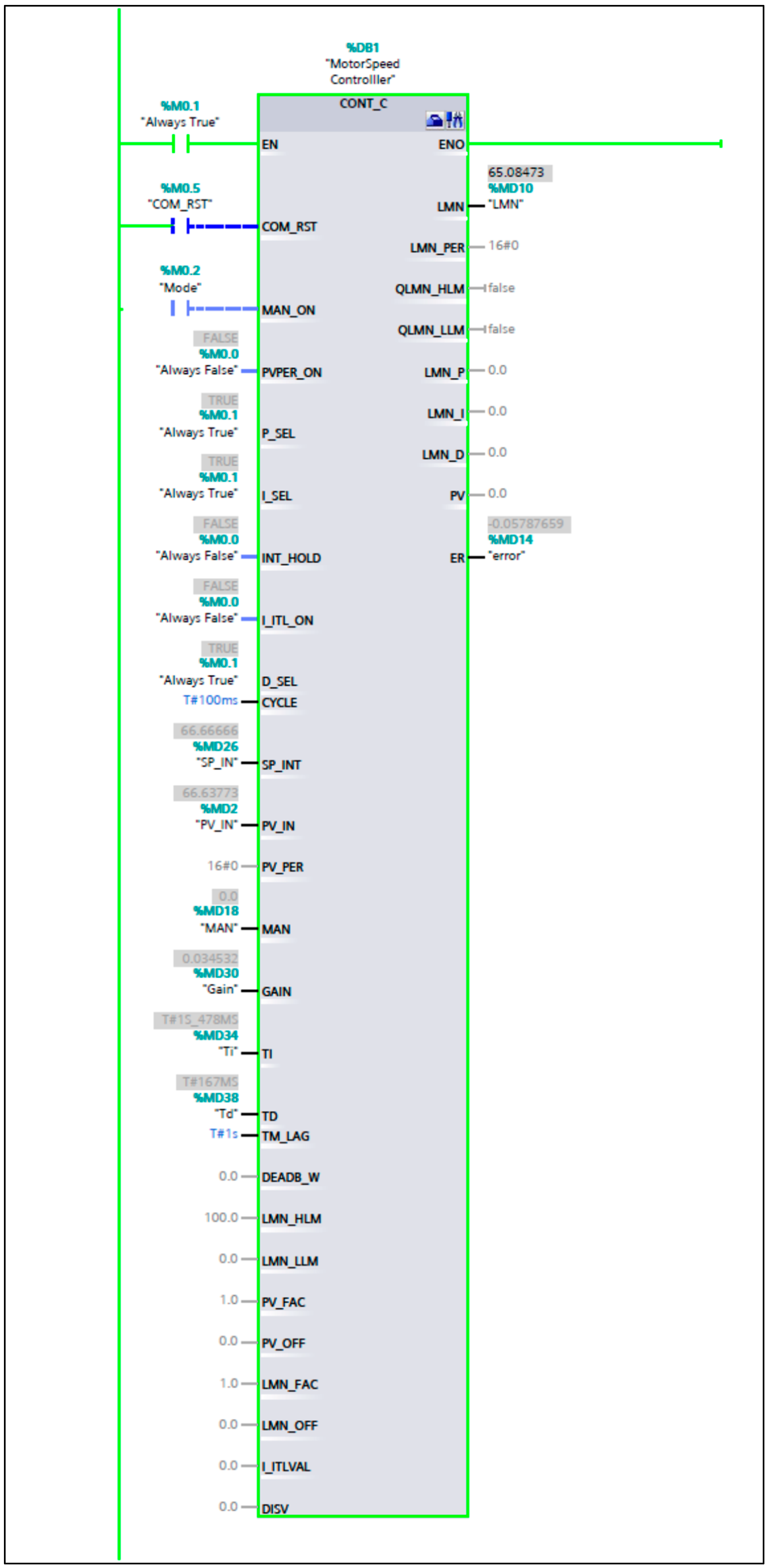

2.3. PLC Conversion and Implementation

2.3.1. Industrial Controller Selection

2.3.2. Controller Parameters Conversion

2.3.3. Speed Controller Implementation

2.3.4. CONT_C Parameters Adjustments

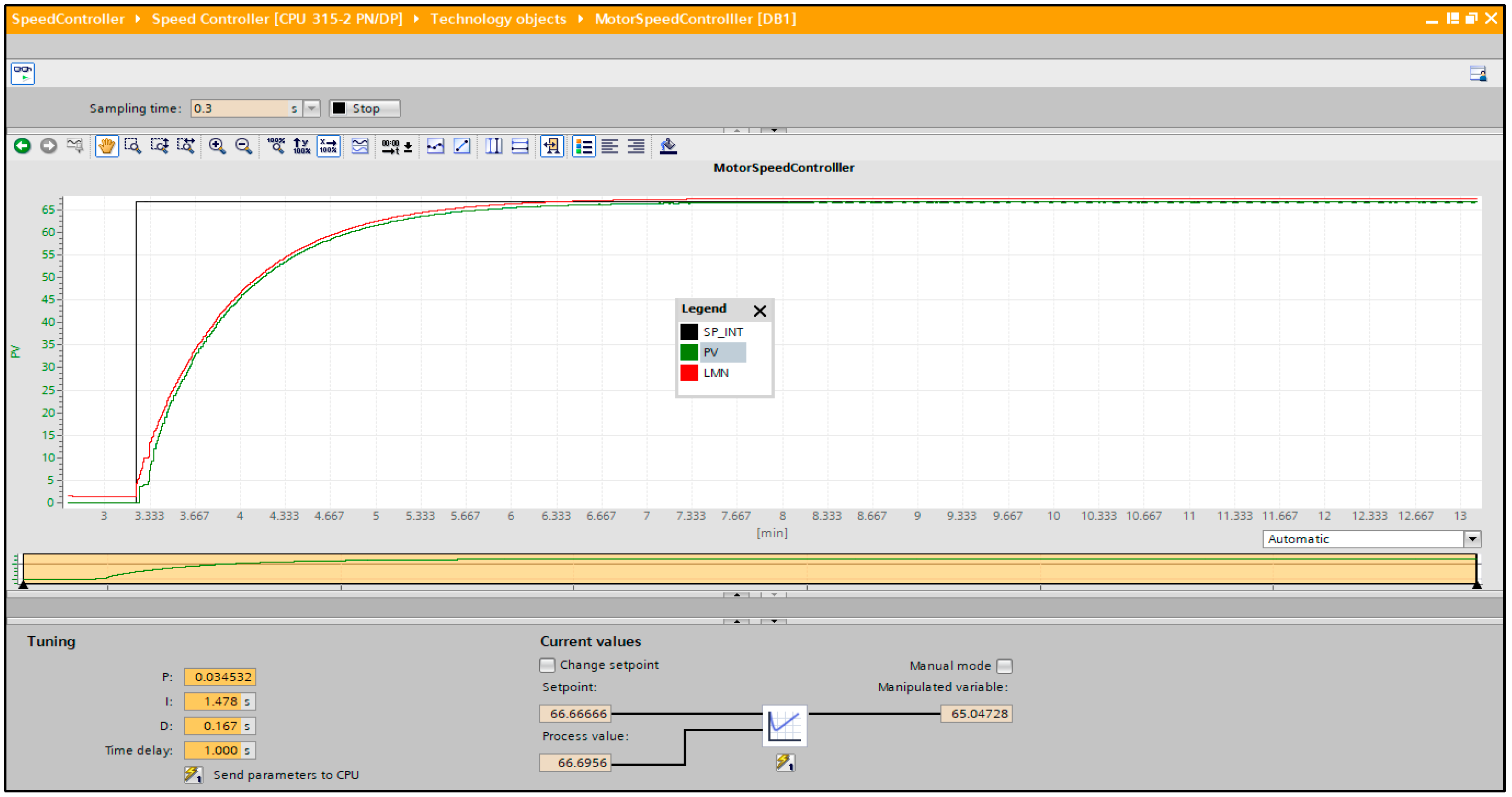

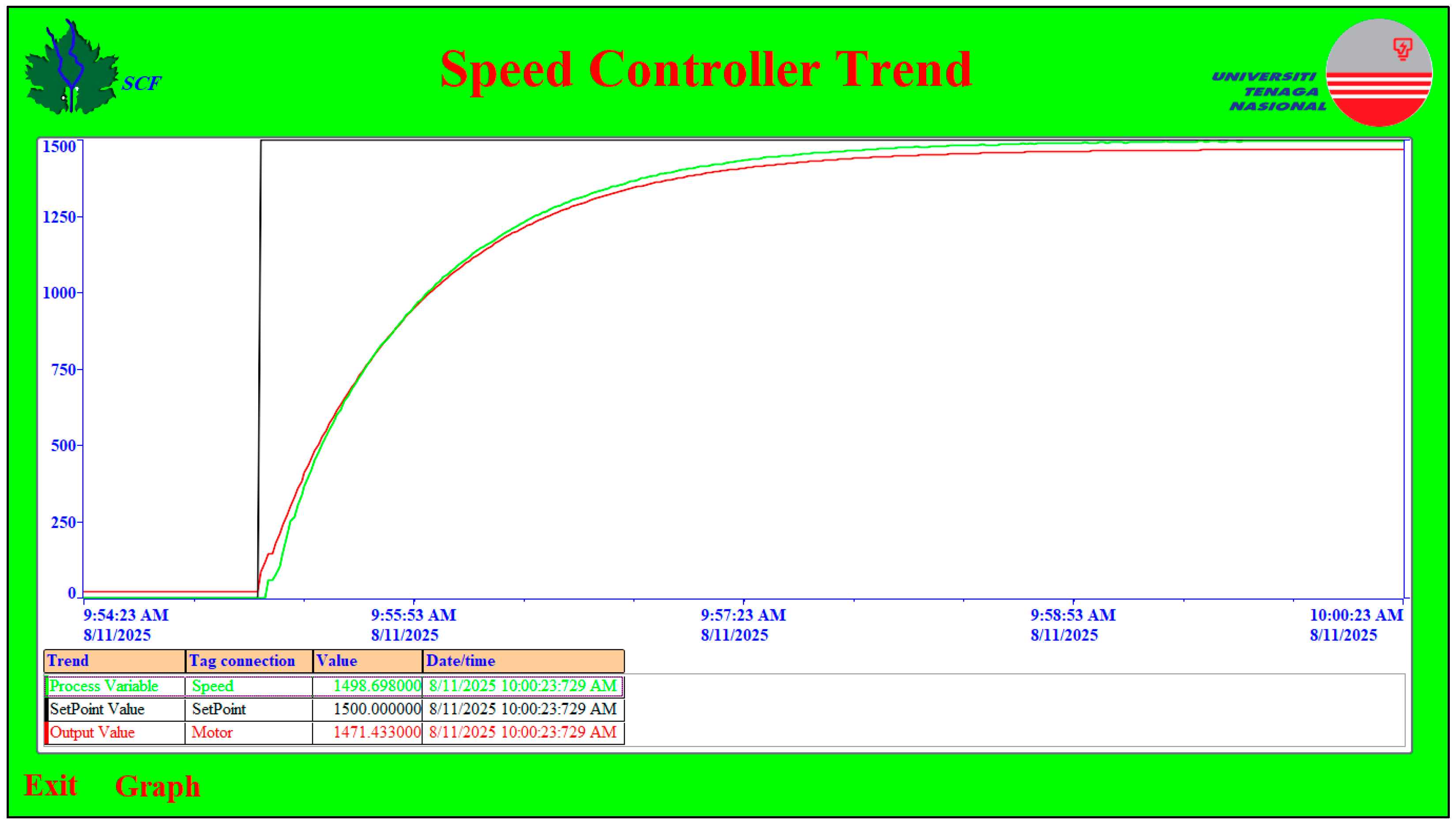

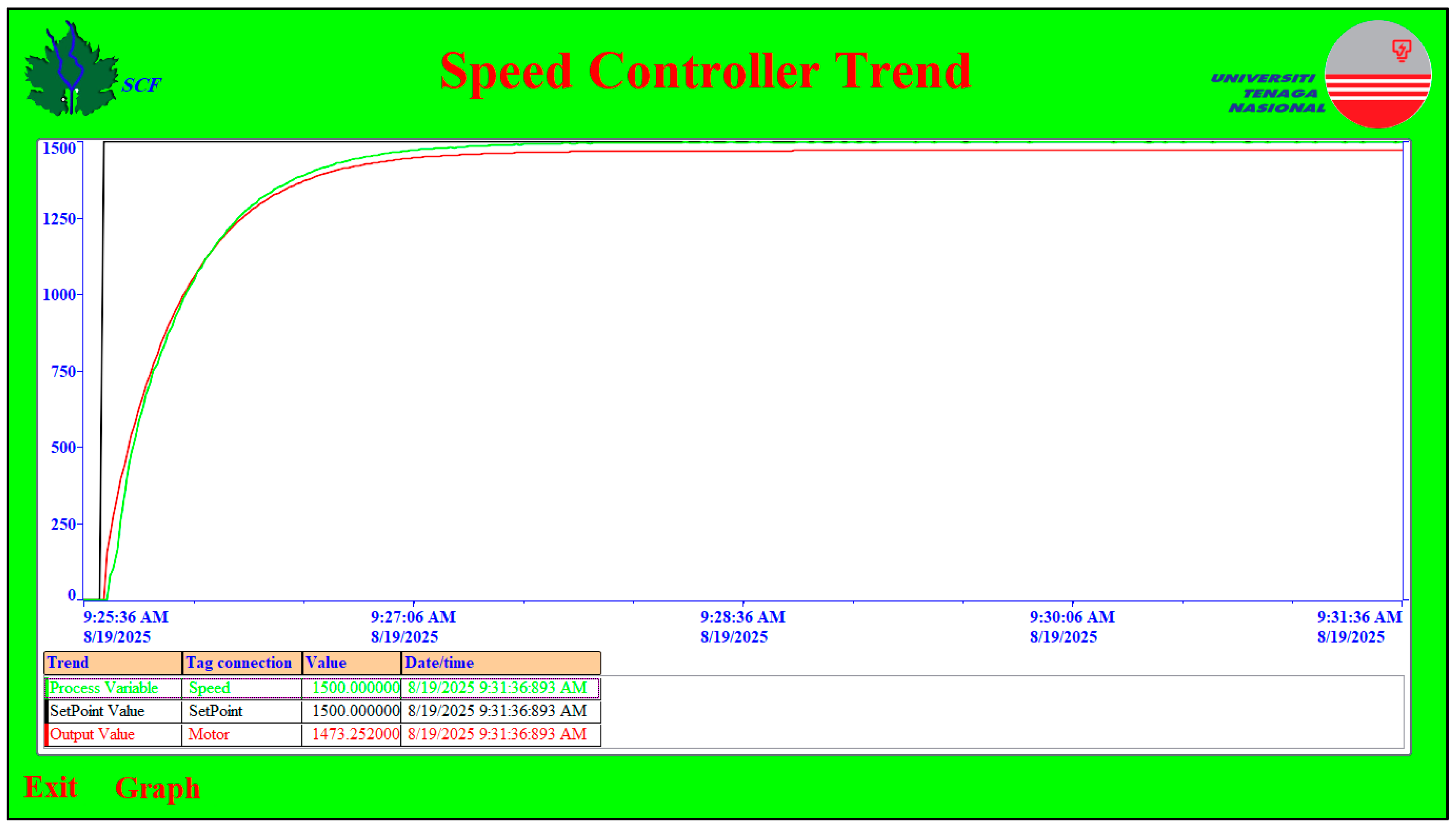

2.3.5. Speed Controller Operation

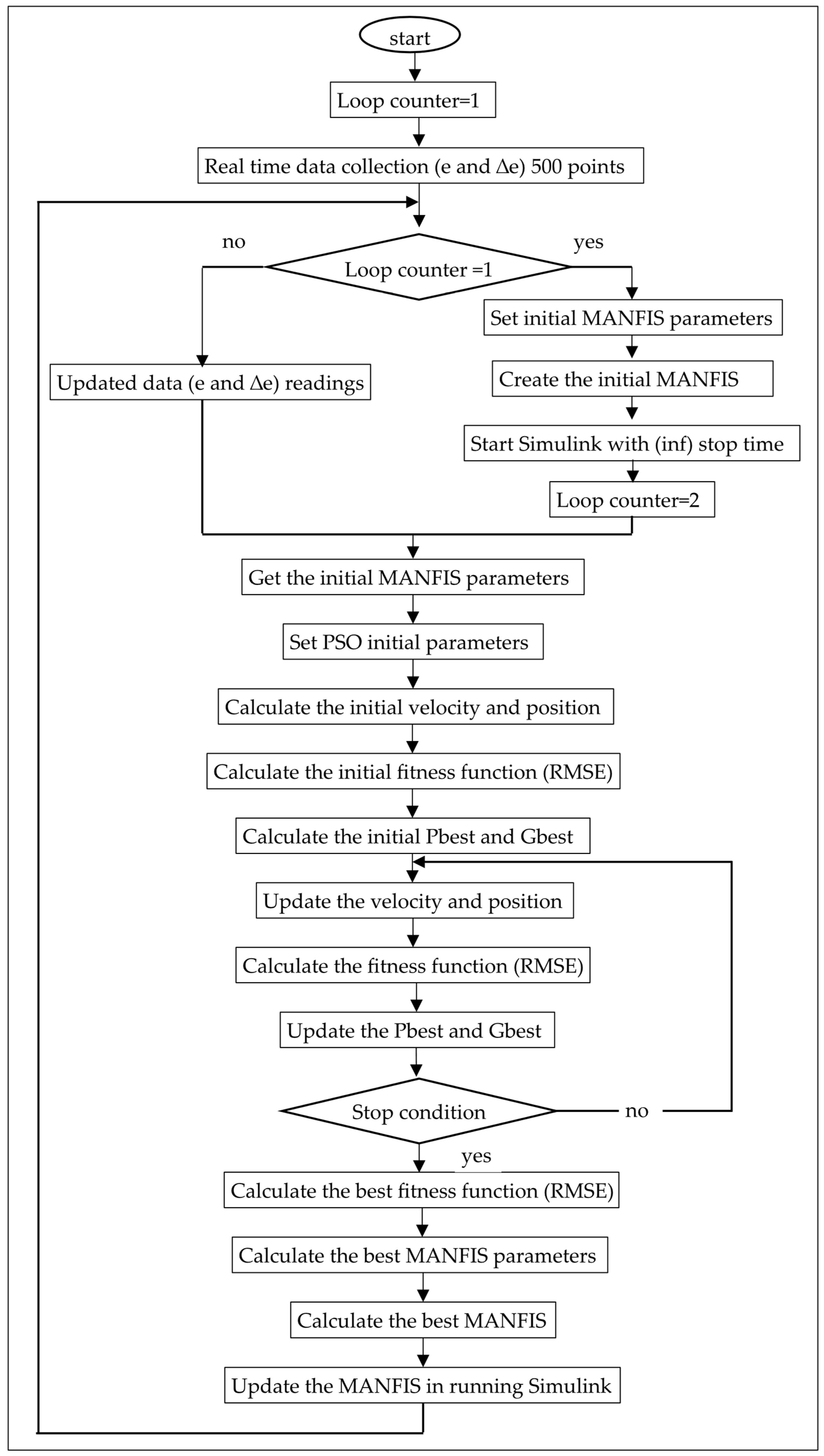

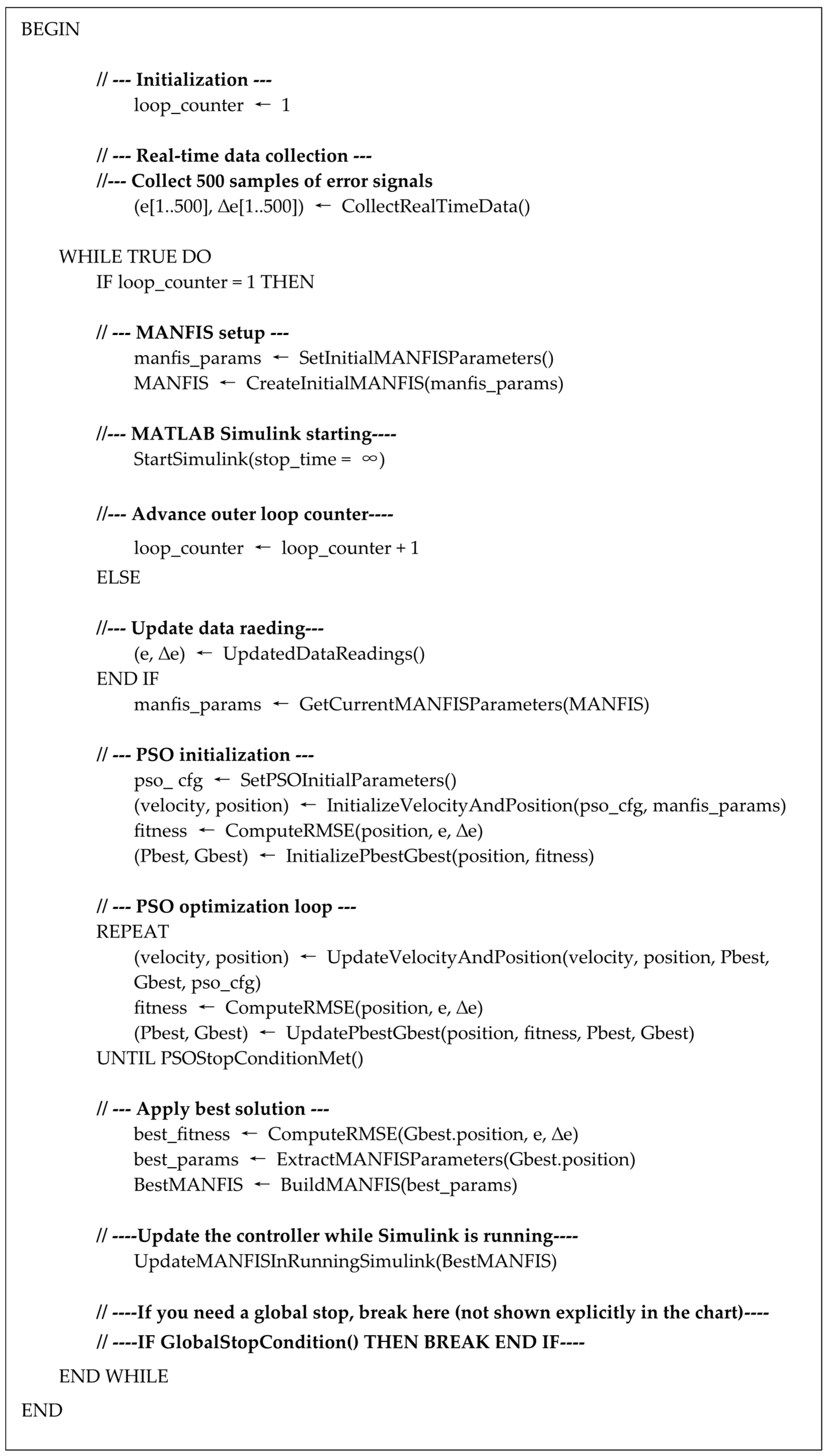

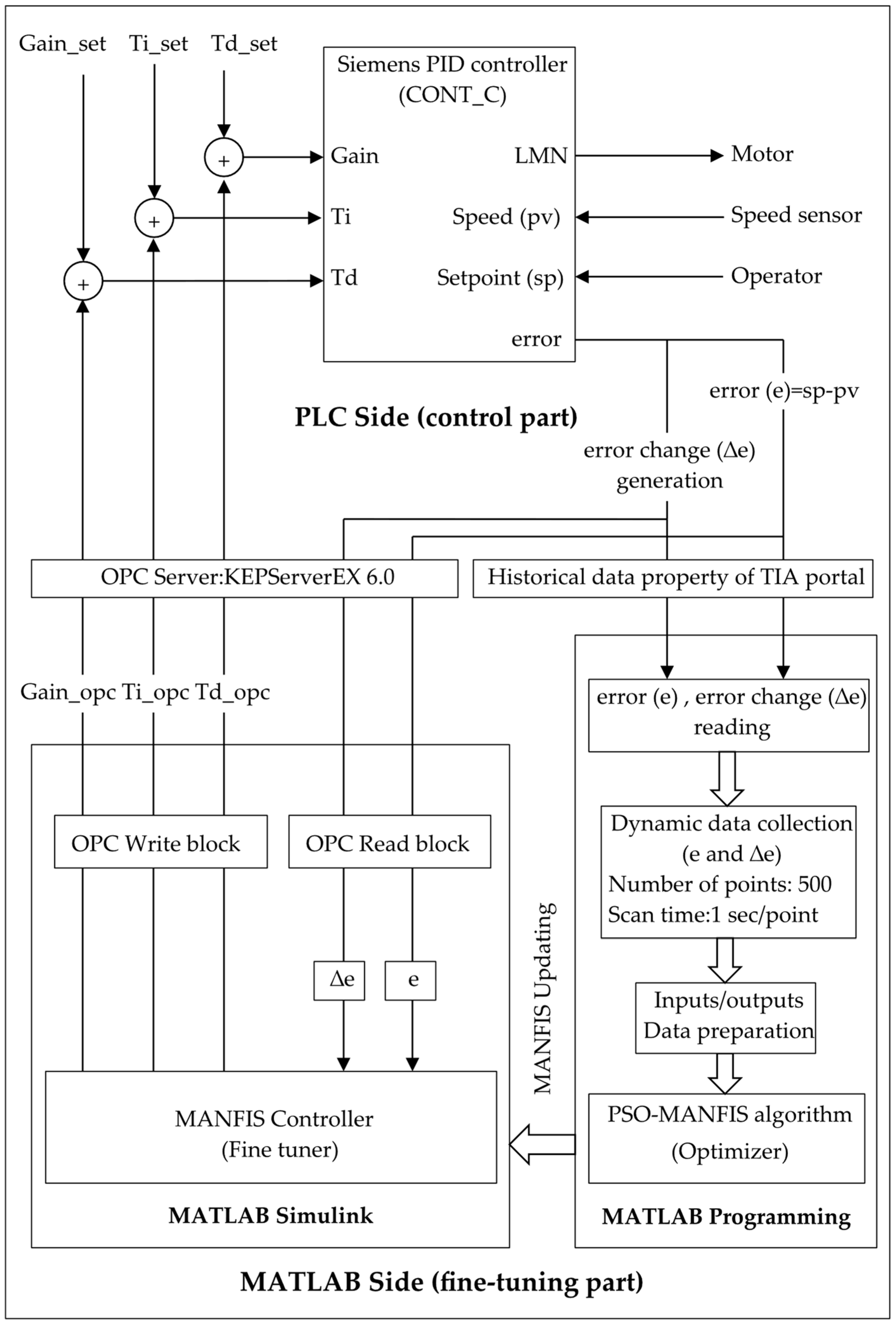

2.4. PSO-MANFIS Dynamic Optimization

2.4.1. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Algorithm

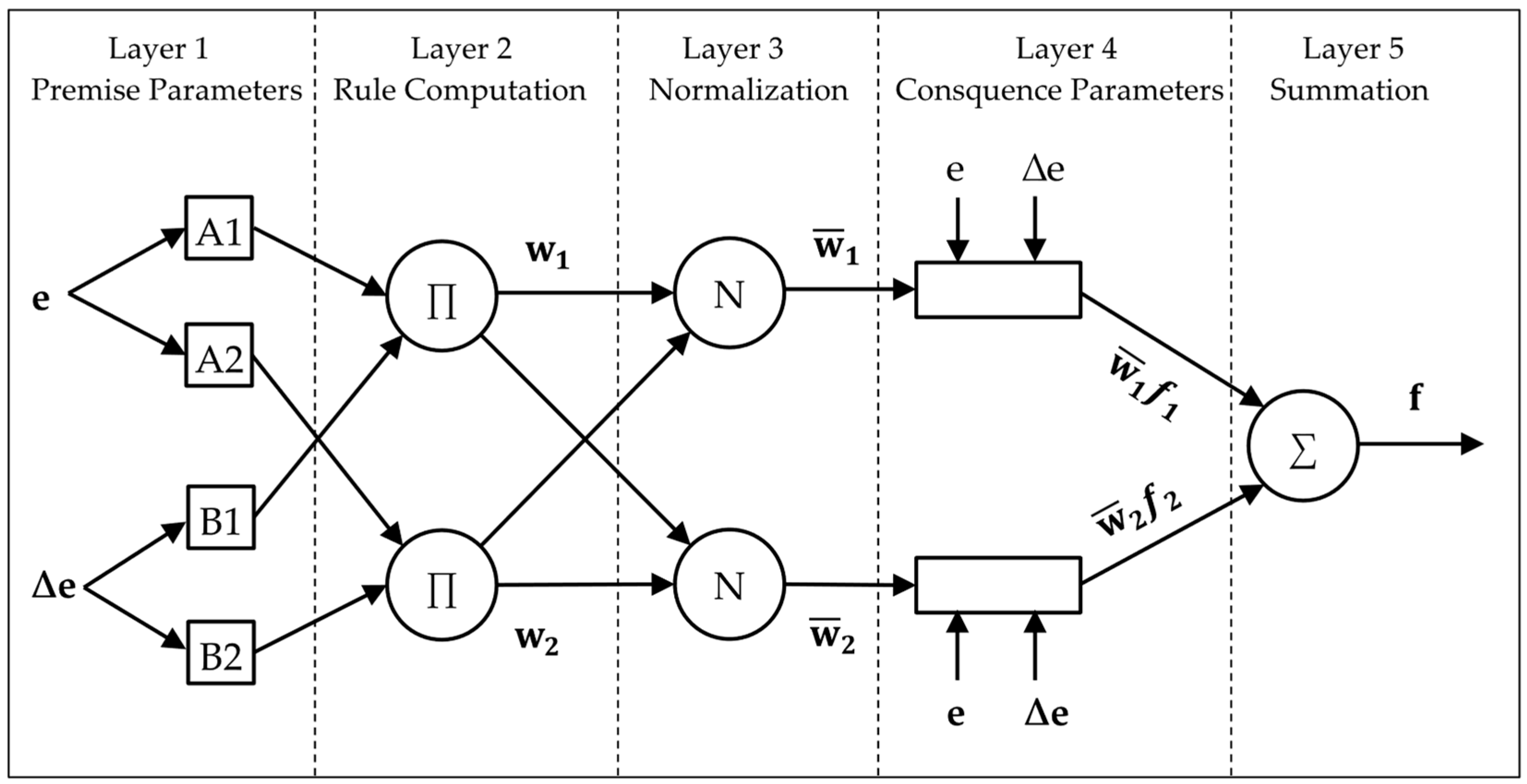

2.4.2. Multiple Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (MANFIS) Model

2.4.3. Dynamic PSO-MANFIS Hybrid Algorithm Developing

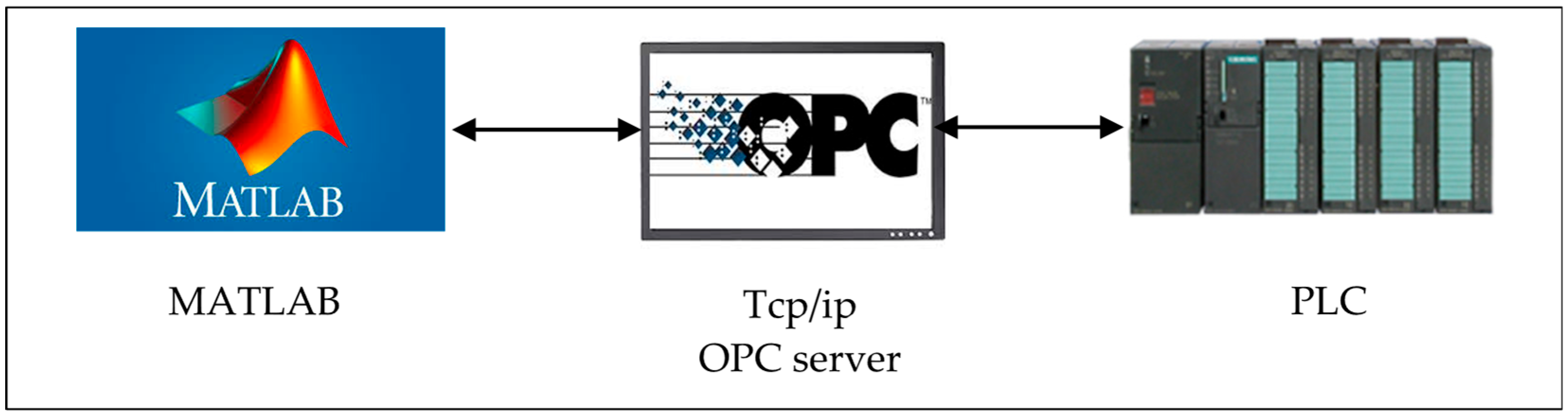

2.5. PLC-MATLAB Communication

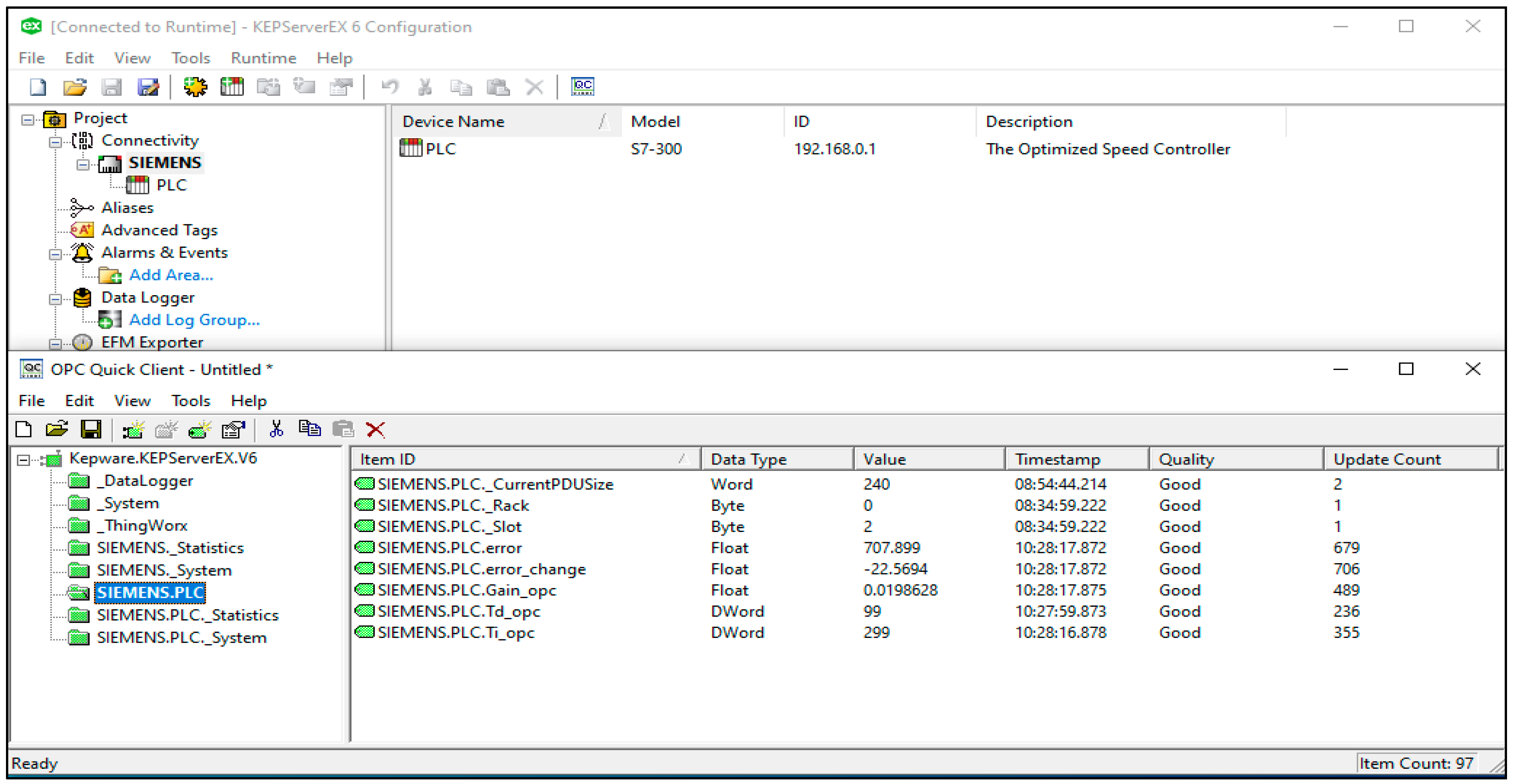

2.5.1. KEPServerEX6.0

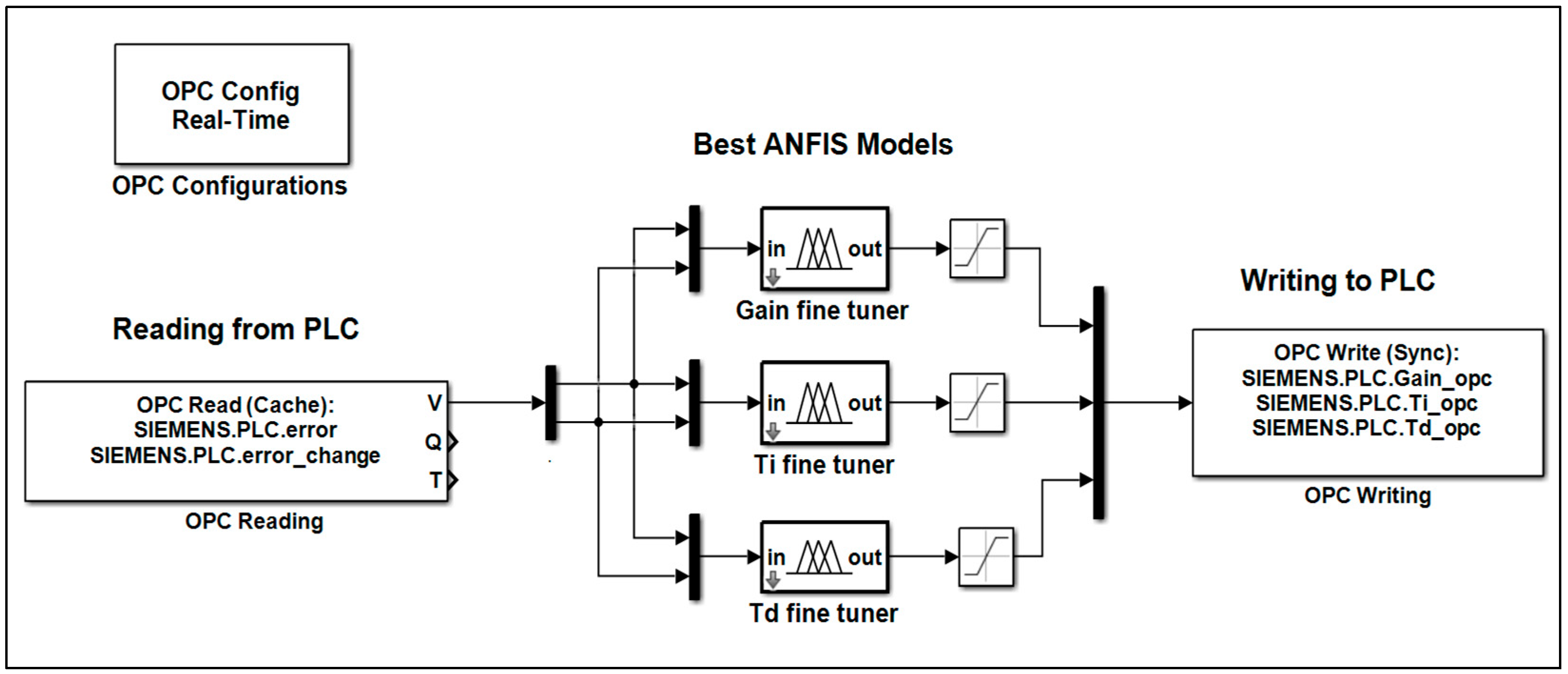

2.5.2. MATLAB OPC Toolbox

- The OPC Configuration block within the OPC Toolbox is primarily responsible for establishing and managing communication between Simulink and the OPC server.

- The OPC Read block in Simulink acquires real-time data from an OPC Data Access (DA) server during simulation. It establishes a connection with the server defined in the OPC Configuration block. It retrieves the current values of designated OPC items (tags), such as sensor measurements, device statuses, or process variables.

- The OPC Write block transmits data from Simulink to an OPC Data Access (DA) server during simulation. This block allows Simulink to write control signals—such as setpoints, commands, or actuator values—to industrial devices through the OPC server interface.

2.5.3. Speed Controller Optimization

3. Results and Discussion

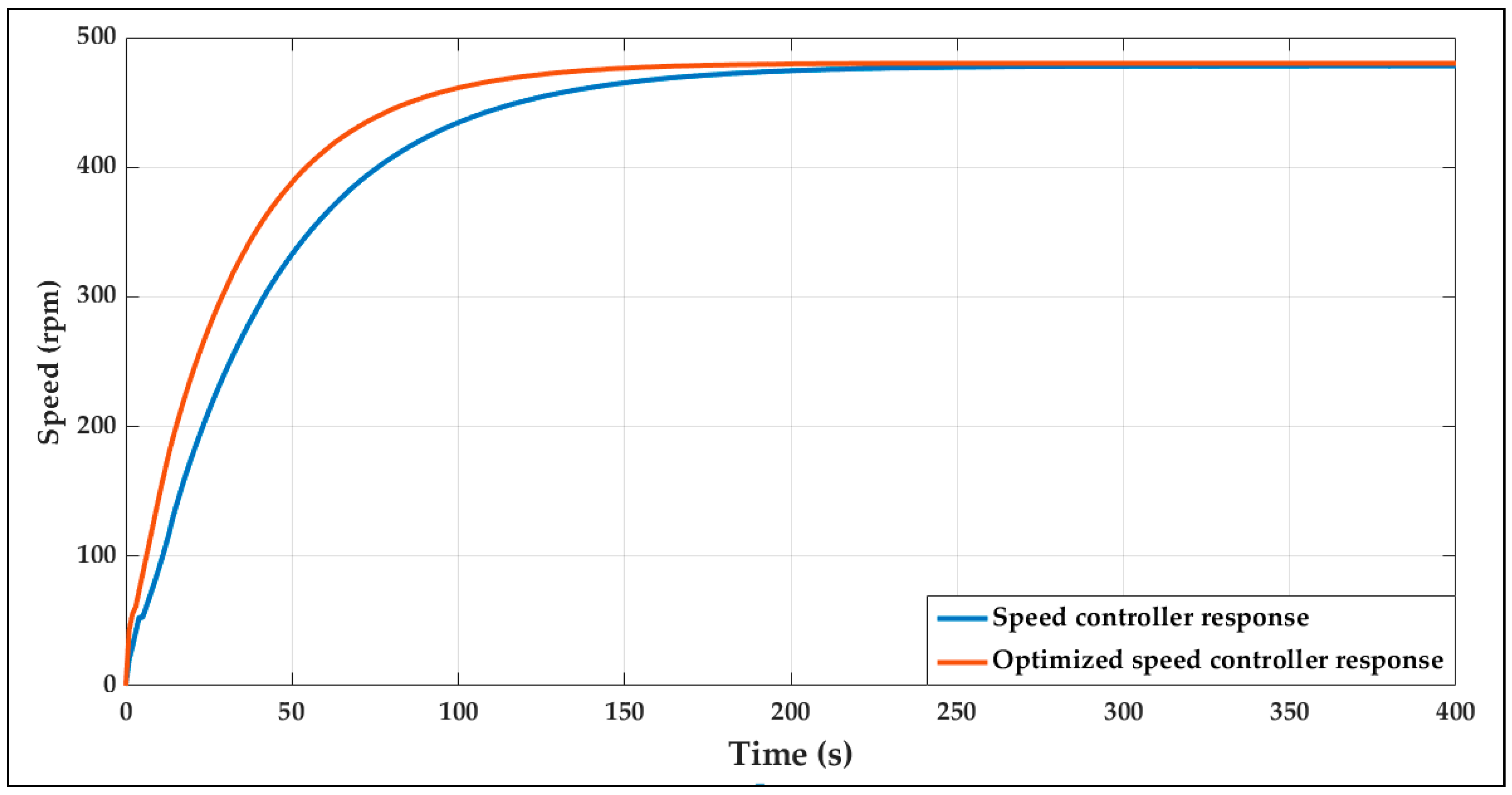

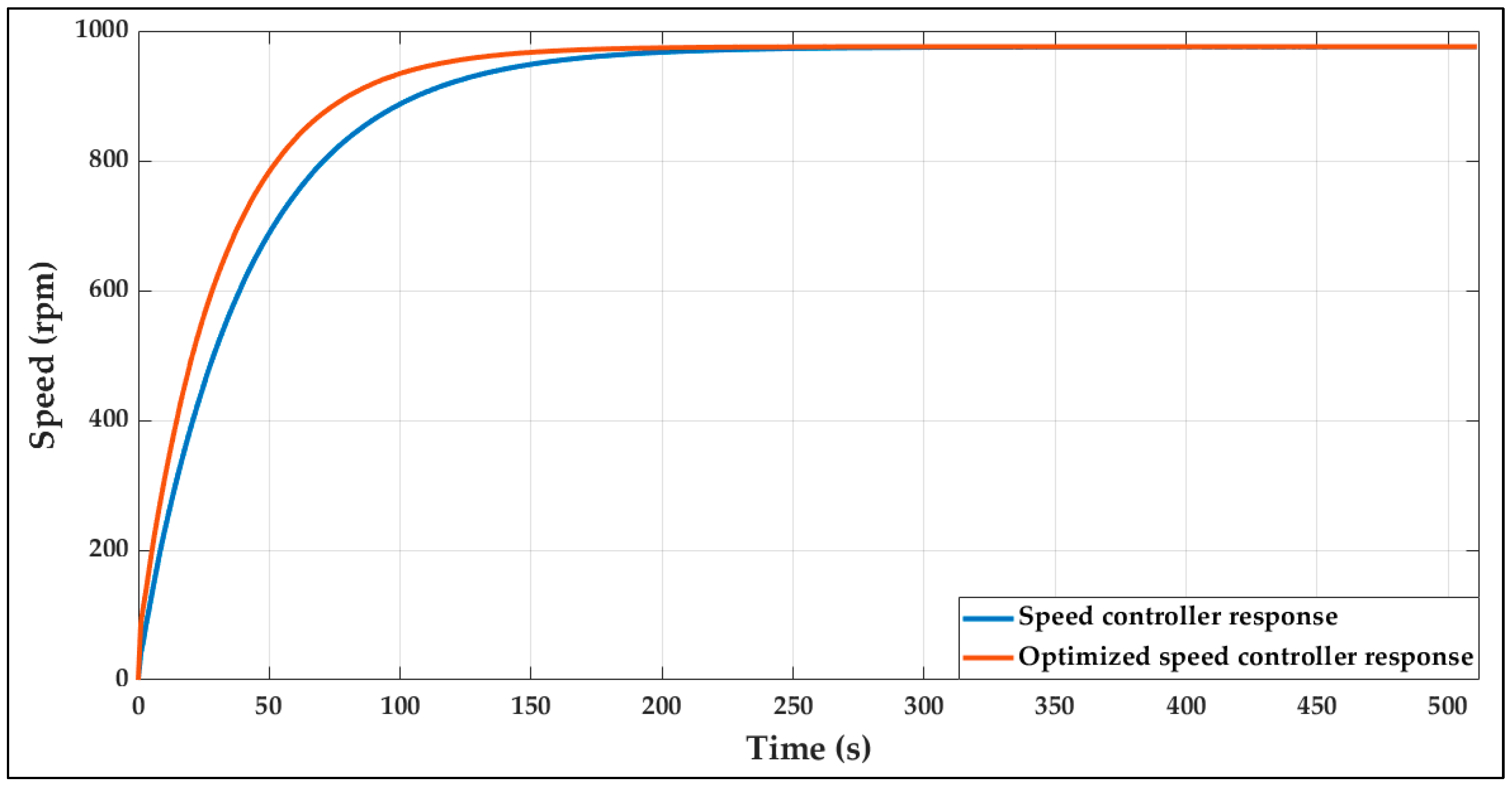

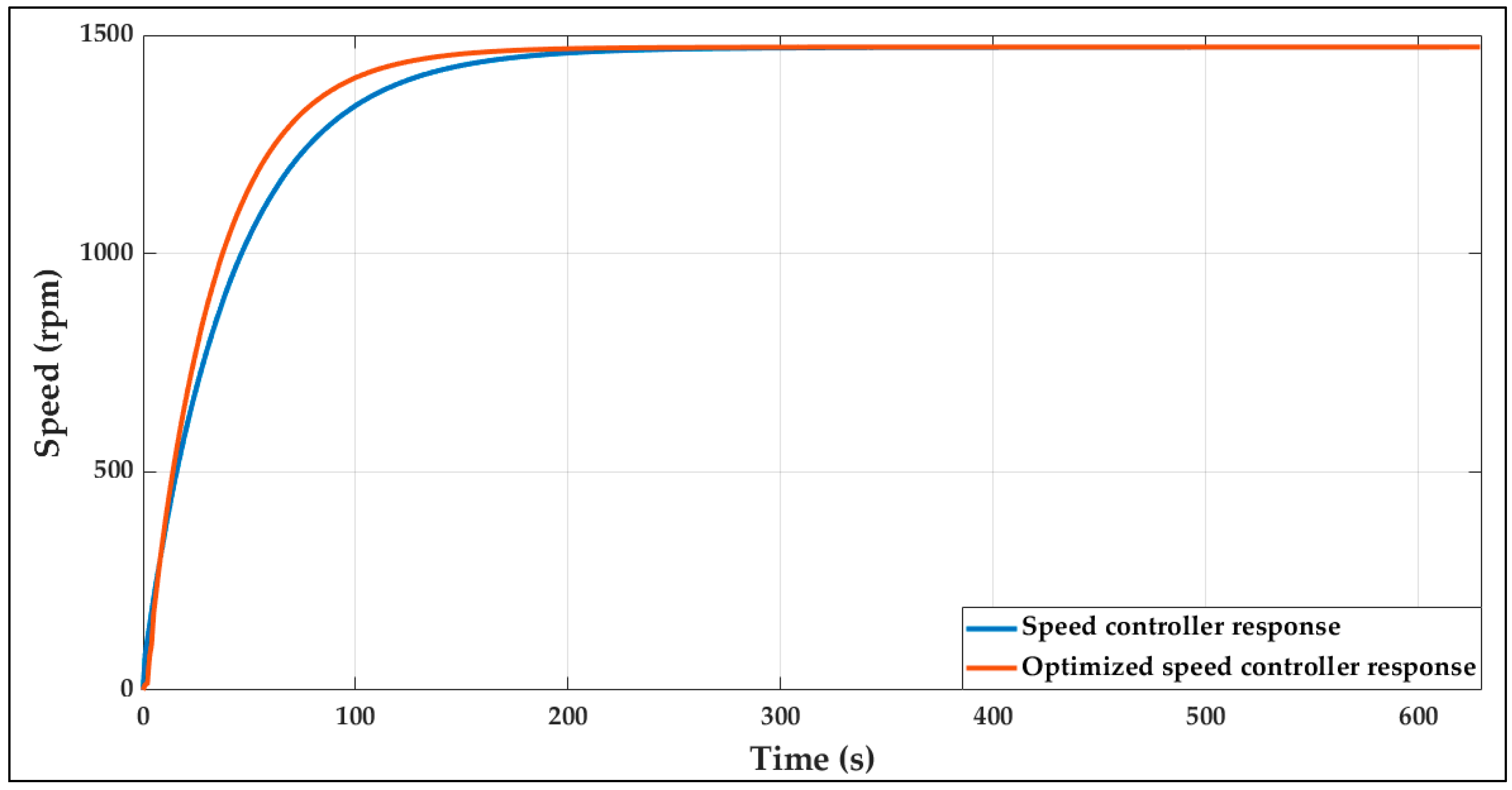

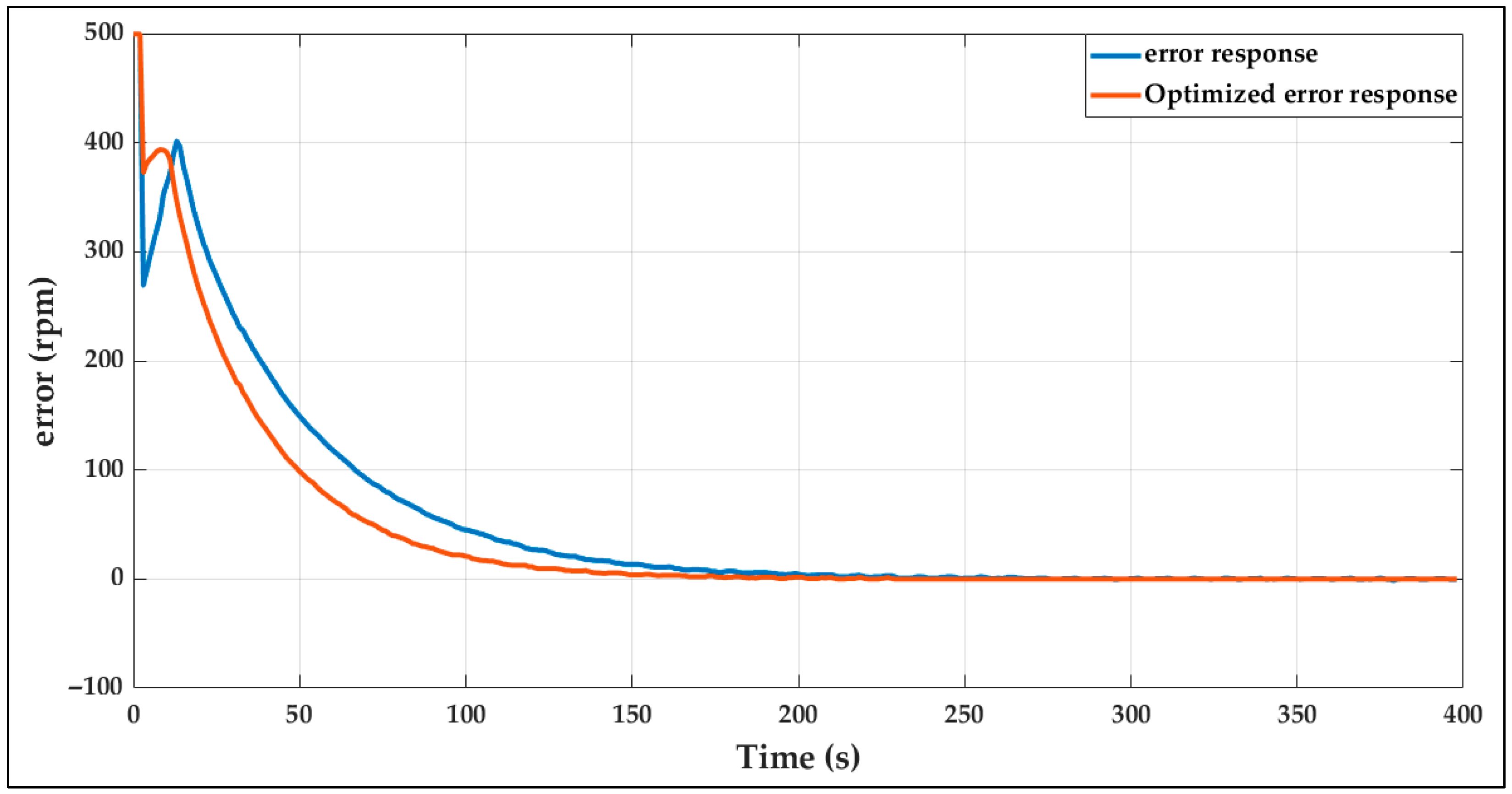

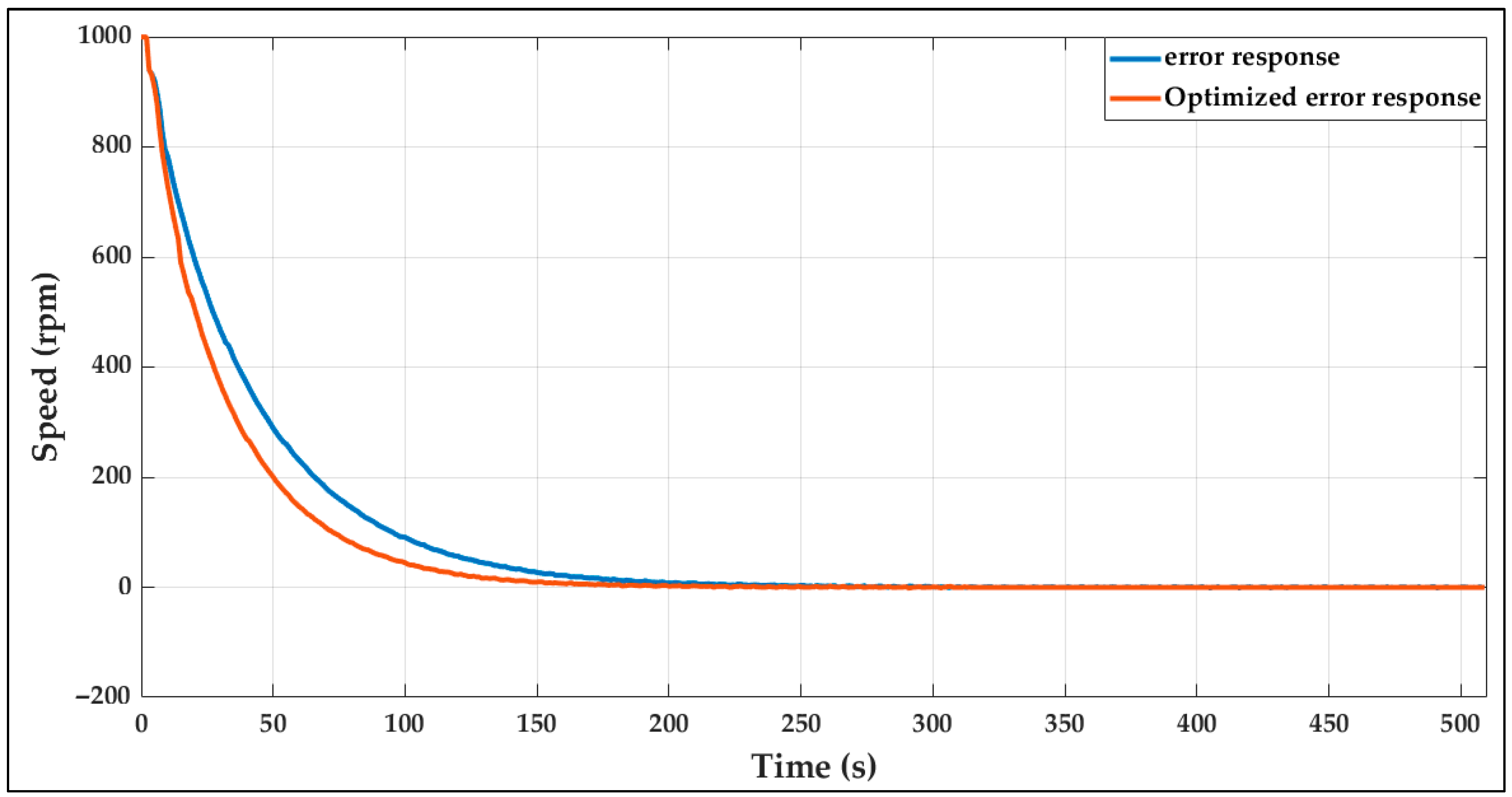

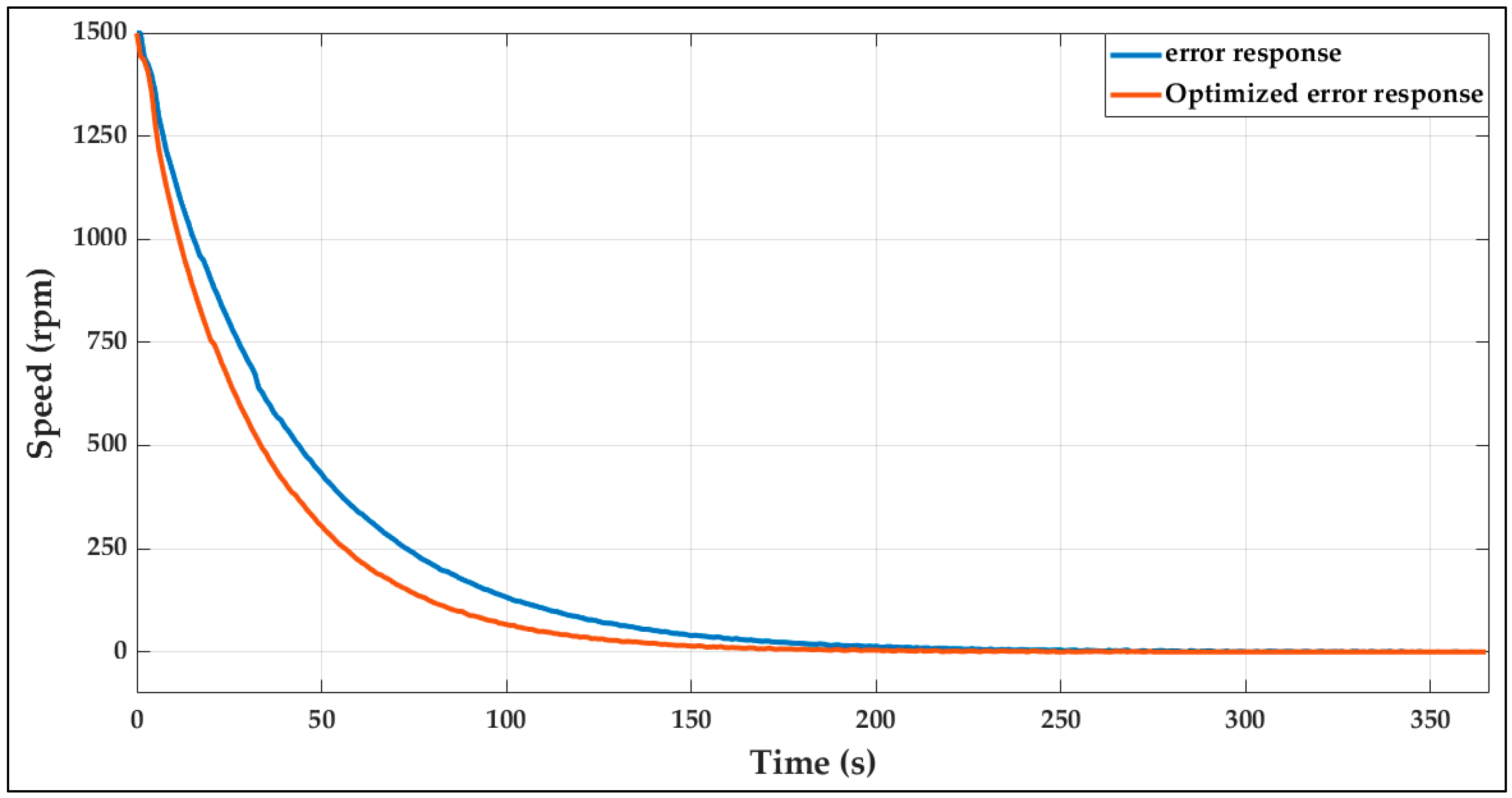

3.1. Discussion of the Results

3.2. Statistical Validation and Repeatability Analysis

- Across all runs, the standard deviations remained below 2% of the mean values, confirming high repeatability.

- The average reduction in rise time and settling time remained within ±1.8% deviation across repetitions, indicating stable optimization performance.

- Overshoot variability was negligible, confirming that the PSO-MANFIS maintained consistent damping across trials.

- These findings demonstrate that the observed improvements are statistically robust and reproducible, with low experimental variance

3.3. Discussion on Scalability, Limitations and Practical Considerations

- Hardware Generalizability:

- Applicability to Other Process Variables:

- Latency and Cycle-Time Constraints:

- Security and Safety Considerations:

- Future Scalability Enhancements:

3.4. Comparative Summary of Hybrid and Intelligent PID Tuning Approaches

3.5. Performance Improvement and Structural Contribution

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soori, M.; Dastres, R.; Arezoo, B.; Jough, F.K.G. Intelligent robotic systems in Industry 4.0: A review. J. Adv. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 2024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiga, D.; Okeleke, P.A.; Folorunsho, S.O.; Ezeigweneme, C. The role of software automation in improving industrial operations and efficiency. Int. J. Eng. Res. Updates 2024, 7, 022–035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, V.S.; Gugnani, A.; Meena, Y.R.; Marathe, V.; Vijay, S.A.A.; Nanda, S. The Impact of Industrial Automation on the Manufacturing Industry in the Era of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies, ICCCNT, Kamand, India, 24–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, E.; Özcan, M.; Hakli, H. Building and Cost Analysis of an Industrial Automation System using Industrial Robots and PLC Integration. Eur. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, W. Programmable Logic Controllers, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Burlington, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sartika, E.M.; Sarjono, T.R.; Saputra, D.D. Saputra. Prediction of PID control model on PLC. Telecommun. Comput. Electron. Control. 2019, 17, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.Z.; Hussain, M.; Kumar, D.; Memon, F.A.; Rustam, B.; Baro, E.N. Design and implementation of PID based flow rate control using PLC. Mehran Univ. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 42, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Jabbar, K.A.; Fezaa, L.H. Enhancing Industrial Automation: A Comprehensive Study on Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and their Impact on Manufacturing Efficiency. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences, ICTACS, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 1–3 November 2023; pp. 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrokhi, M.; Zomorrodi, A. Comparison of PID Controller Tuning Methods. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Comparison-of-PID-Controller-Tuning-Methods-Shahrokhi-Zomorrodi/b4ca1b81247f71593d3e60f4169f9307baa361d4 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Joseph, E. Cohen-Coon PID Tuning Method: A Better Option to Ziegler Nichols-Pid Tuning Method. 2018. Available online: www.iiste.org (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Bharat, S.; Ganguly, A.; Chatterjee, R.; Basak, B.; Sheet, D.; Ganguly, A. A Review on Tuning Methods for PID Controller. Asian J. Converg. Technol. 2024, 10, 3. Available online: www.asianssr.org (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall/Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, D.; Ahmed, A.; Kumar, S.; Roy, D. Fuzzy-PID and interpolation: A novel synergetic approach to process control. Int. J. Optim. Control. Theor. Appl. 2024, 14, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.K.; Tran, V.K.; Pham, H.; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, C.N. Design and Implementation of Fuzzy-based Fine-tuning PID Controller for Programmable Logic Controller. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2024, 16, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, A.; Basri, M.A.M. Self-Tuning PID Controller for Quadcopter using Fuzzy Logic. Int. J. Robot. Control. Syst. 2023, 3, 728–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazha, H.M.; Youssef, A.M.; Darwich, M.A.; Ibrahim, T.A.; Homsieh, H.E. A Comparative Study on Fuzzy Logic-Based Liquid Level Control Systems with Integrated Industrial Communication Technology. Computation 2025, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, M.A.; Elnady, A.O.; Ibrahim, S.O. Optimum PID Controller with Fuzzy Self-Tuning for DC Servo Motor. J. Robot. Control. 2023, 4, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheioon, I.A.; Al-Sabur, R.; Sharkawy, A.-N. Design and Modeling of an Intelligent Robotic Gripper Using a Cam Mechanism with Position and Force Control Using an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Computing Technique. Automation 2025, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, C.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, T. Nonlinear Adaptive Generalized Predictive Control for PH Model of Nutrient Solution in Plant Factory Based on ANFIS. Processes 2023, 11, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N.R.; Sai, S.S.; Kumar, U.; Chenchireddy, K.; Kumar, K.T.; Naveen, M. Optimized Speed Control of BLDC Motor Control by using PID and ANFIS. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Communication Networks and Application, ICSCNA, Theni, India, 15–17 November 2023; pp. 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.K.; Kanagasabai, N. Performance Analysis of ANFIS-PID Controller based Speed Regulation and Harmonic Reduction in BLDC Motor Application. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Res. 2024, 12, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE. 2019 2nd International Conference on Power Energy Environment and Intelligent Control (PEEIC-2019): 18–19 October 2019, Department of Electrical & Electronics Engineering, G.L. Bajaj Institute of Technology and Management, Greater Noida, India; IEEE: Denvers, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, I.A.; Mustafa, K. A review of adaptive tuning of PID-controller: Optimization techniques and applications. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2024, 15, 2008–6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najari, B.; Hen, C.K.; Paw, J.K.S.; Marhoon, A.F. Design and Implementation of PID Controller for the Cooling Tower’s pH Regulation Based on Particle Swarm Optimization PSO Algorithm. Iraqi J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 20, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-C.; Zhuang, Q.-Y.; Liu, L.-Y.; Su, T.-J. PID Control Design Based on Particle Swarm Algorithm and Fuzzy Algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Intelligent Signal Processing and Communication Systems, ISPACS, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 10–13 December 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, J.K.; Tirole, R.; Bhaskar, A. Optimization of PID Controllers for Cascade Control Loops Using Particle Swarm Optimization Techniques. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud), I-SMAC, Kirtipur, Nepal, 3–5 October 2024; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, J.C.Z.; Alemán, M.A.C. Intelligent tuning of PID controllers: Comprehensive approach based on modified Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm. In Proceedings of the IECON 2024-50th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhawat, M.; Altınkaya, H. Frequency Regulation of Stand-Alone Synchronous Generator via Induction Motor Speed Control Using a PSO-Fuzzy PID Controller. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z. Efficiency Assessment of ANN, ANFIS, and PSO-ANFIS for Predicting University Residence Energy Usage. In Proceedings of the PMAPS 2024—18th International Conference on Probabilistic Methods Applied to Power Systems, Auckland, New Zealand, 24–26 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, N.; Venkatesan, S.; Kannan, R.; Kannan, S.; Bhuvanesh, A.; Kamaraja, A. Sensorless speed and position control of permanent magnet BLDC motor using particle swarm optimization and ANFIS. Meas. Sens. 2023, 31, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirik, M.; Gül, M. Dynamic Optimal ANFIS Parameters Tuning with Particle Swarm Optimization. Eur. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 28, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najari, B.M.A.; Wali, W.A. Optimization of pH Controller Performance for Industrial Cooling Towers via the PSO–MANFIS Hybrid Algorithm. Energies 2025, 18, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najari, B. Design and implementation of control Cabinet Based Siemens S7-300 Programmable Logic Controller PLC. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Multi-Disciplinary Conference Theme: Integrated Sciences and Technologies, IMDC-IST 2021, Sakarya, Turkey, 7–9 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ifm.com/de/en/product/IG5397#documents (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.phoenixcontact.com/en-us/products/frequency-transducer-mcr-f-ui-dc-2814605?type=pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Available online: https://mall.industry.siemens.com/mall/en/ww/Catalog/Product/?mlfb=6SL3210-1KE15-8UF2 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.bernardimotorielettrici.it/upload/documenti/motori-elettrici/01.01-motori-elettrici-standard.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Peng, C.-C.; Cheng, Y.-H. Data Driven based Modeling and Fault Detection for the MATLAB/Simulink Turbofan Engine: An ARX Model Approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications, CCTA 2022, Trieste, Italy, 23–25 August 2022; pp. 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gao, F.; Ren, W. Speed Control of PMSM Based on Data-Driven Method. In Proceedings of the 2022 11th International Conference of Information and Communication Technology, ICTech, Wuhan, China, 4–6 February 2022; pp. 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, S.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X. Application of optimizing PID Parameters based on PSO in the Temperature Control System of Haematococcus Pluvialis. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 9th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC), Chongqing, China, 11–13 December 2020; pp. 1850–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.K.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Dash, S.S. Gravitational Search Algorithm for Optimal Tunning of controller parameters in AVR system. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Smart Power System and Sustainable Energy (CISPSSE), Keonjhar, India, 29–31 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rooholahi, B.; Reddy, P.L. Concept and application of PID control and implementation of continuous PID controller in Siemens PLCs. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.fer.unizg.hr/_download/repository/S7pidcob.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Van Nghiep, D.; Son, L.H. Implementation of Digital PID Controller in Siemens PLC S7-300. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2018, 5, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgenc, B.; Ayas, M.S.; Altas, I.H. A Hybrid Optimization Approach to Design Optimally Tuned PID Controller for an AVR System. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA), Ankara, Turkey, 26–28 June 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oladipo, S.; Sun, Y.; Amole, A.O. Investigating the influence of clustering techniques and parameters on a hybrid PSO-driven ANFIS model for electricity prediction. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadianfar, I.; Shirvani-Hosseini, S.; He, J.; Samadi-Koucheksaraee, A.; Yaseen, Z.M. An improved adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system model using conjoined metaheuristic algorithms for electrical conductivity prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian, A.; Styles, P.; Zomorrodian, H. Depth Estimation of Cavities from Microgravity Data Through Multi Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Interference System. In Proceedings of the Near Surface 2011—17th EAGE European Meeting of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, Leicester, UK, 12–14 September 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, U.; Reddy, K.S.; Kaliyaperumal, D.; Sailaja, V.; Bhargavi, P.; Likhith, S. A MIMO–ANFIS-Controlled Solar-Fuel-Cell-Based Switched Capacitor Z-Source Converter for an Off-Board EV Charger. Energies 2023, 16, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, M.; Ganchev, I.; Taneva, A. Fuzzy PID control of nonlinear plants. In Proceedings of the 2002 1st International IEEE Symposium, Varna, Bulgaria, 10–12 September 2002; pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klir, E.; Sun, J.R.; Mizutami, C.T. Neuro Fuzzy and Soft Computing; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, M.N.M.; Talpur, N.; Talpur, K.H. A Modified Neuro-Fuzzy System Using Metaheuristic Approaches for Data Classification. In Artificial Intelligence—Emerging Trends and Applications; InTech: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, M.N.M.; Hussain, K. A Review of Training Methods of ANFIS for Applications in Business and Economics. Int. J. u- e- Serv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonar, A.; Yonar, H. Modeling air pollution by integrating ANFIS and metaheuristic algorithms. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2023, 9, 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghomsheh, V.S.; Shoorehdeli, M.A.; Teshnehlab, M. Training ANFIS Structure with Modified PSO Algorithm. In Proceedings of the MED’07, Mediterranean Conference on Control & Automation, Athens, Greece, 27–29 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Altınkaya, H.; Ekmekci, D. Tuning of PID Controller in PLC-Based Automatic Voltage Regulator System Using Adaptive Artificial Bee Colony–Fuzzy Logic Algorithm. Electronics 2024, 13, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal, K.; Kadu, C.; Parvat, B.; Vikhe, P. PLC Based Real Time Process Control Using SCADA and MATLAB. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Computing, Communication Control and Automation, ICCUBEA, Pune, India, 16–18 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, J.; Yue, X. RBF Neural Network-based Cooperative Electromagnetic Takeover Control for Large-scale Failed Spacecraft. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | Representative Reference | Real-Time Capability | Typical Hardware/Platform | Reported Performance Improvements | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuzzy PID/Fuzzy fine-tuning | [13,14,15,16,17] | Mixed: several simulation studies; at least one PLC deployment (e.g., S7-1200) | MATLAB/Simulink; some Siemens PLC use cases | Reduced overshoot and settling time; e.g., up to 21% overshoot reduction and 83% settling-time decrease reported in level/thermal applications | Rule design can be subjective; MF tuning needs domain expertise; scalability across operating regimes can be limited |

| ANFIS-based PID tuning | [18,19,20,21,22] | Mostly offline/simulation | MATLAB/Simulink; motor drives benches | Better speed accuracy and transient response; lower THD in motor drives; improved steady-state error, rise time and settling time | May converge to local minima; sensitive to initialization; limited industrial PLC integration in prior works |

| PSO-tuned PID (single stage) | [23,24,25,26,27] | Primarily offline batch tuning; some lab/plant trials (e.g., pH control) | MATLAB/Simulink; lab plants; occasional industrial case | Faster response, reduced overshoot, improved stability vs. classical tuning; good global search of Kp-Ki-Kd | One-shot tuning (not adaptive); can be slow for large search spaces; limited on-line adaptation under time-varying dynamics |

| Hybrid PSO–ANFIS | [28,29,30,31] | Mostly simulation or non-PLC domains (prediction/control) | MATLAB/Simulink; generator/motor benches | Combines ANFIS adaptability with PSO exploration; lower overshoot and shorter settling time than PID/Fuzzy alone | Often non-real-time; limited direct deployment on PLC hardware; focus not on industrial built-in PID |

| PSO–MANFIS (prior art) | [32] | Algorithmic optimization demonstrated with plant data; not PLC-embedded | MATLAB + plant data (cooling towers) | Significant gains reported for industrial pH regulation vs. classical tuning | No direct closed-loop fine-tuning of PLC built-in PID; lacks OPC-based, real-time parameter update on controller hardware |

| This work: PSO-MANFIS + PLC built-in PID controller | Current study | Yes—continuous on-line tuning via OPC during operation | Siemens S7-300 (CONT_C) + MATLAB/Simulink + KEPServerEX OPC, VFD-driven motor | live fine-tuning of Gain, Ti, Td improves transient response | A third-party software, such as the KEPServerEX OPC Server interface, is required for the MATLAB-PLC connection to enable data exchange for dynamic tuning. |

| Industrial Process Element | Prefix | Industrial PID Controller Name |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure | PIC | Pressure indicating controller |

| Level | LIC | Level indicating controller |

| Flow | FIC | Flow indicating controller |

| Temperature | TIC | Temperature indicating controller |

| Speed | SIC | Speed indicating controller |

| Chemical | AIC | Analyzing indicating controller |

| Parameter | Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kp | Proportional gain | 0.034532 | unitless |

| Ki | Integral gain | 0.00046726 | s |

| Kd | Derivative gain | 0.28913 | s |

| N | Filter | 0.041405 | unitless |

| Performance Metric Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Rise time | 66.6567 | s |

| Settling time | 281.5768 | s |

| Overshoot | 4.6426 | % |

| Set point | 1250 | rpm |

| Peak | 1307.3 | rpm |

| Peak time | 168.4399 | s |

| Parameter | Description | MATLAB | PLC | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kp | Proportional gain | 0.034532 | 0.034532 | unitless |

| Ki | Integral gain | 0.00046726 | 73.9 | s |

| Kd | Derivative gain | 0.28913 | 8.37 | s |

| Block | Block Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| OB1 | Main program | Run FC1 and FC2 |

| OB35 | Cyclic interrupt | Run the CONT_C block every 100 milliseconds |

| FC1 | Function block | Reading and scaling of the motor speed |

| FC2 | function block | Scales the output signal directed to VFD |

| Terminal | Description | Address | Signal Name | Setting | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN | Enable | M0.1 | Always_True | True | unitless |

| COM_RST | Complete restart | M0.5 | COM_RST | False\True | unitless |

| MAN_ON | Manual on | M0.2 | mode | False\True | unitless |

| P_SET | Proportional action on | M0.1 | Always_True | True | unitless |

| I_SET | Integral action on | M0.1 | Always_True | True | unitless |

| D_SET | Derivative action on | M0.1 | Always_True | True | s |

| CYCLE | Sampling time | direct | ---------------- | 100 | ms |

| SP_INT | Internal set point | MD26 | SP_IN | 0–100 | % |

| PV_IN | Process variable in | MD2 | PV_IN | 0–100 | % |

| MAN | Manual | MD18 | MAN | 0–100 | % |

| Gain | Proportional gain | MD30 | Gain | 0.034532 | unitless |

| Ti | Integral time | MD34 | Ti | 73.9 | s |

| Td | Derivative time | MD38 | Td | 8.37 | s |

| TM_LAG | Time lag | direct | -------------- | 1 | s |

| LMN | Manipulated value | MD10 | LMN | 0–100 | % |

| ER | Error | MD14 | ER | (SP-PV) | % |

| Parameter | Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gain | Proportional gain | 0.034532 | unitless |

| Ti | Integral time | 1.478 | s |

| Td | Derivative time | 0.167 | s |

| Prefix | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| m | Number of variables (MANFIS parameters) | 117 |

| n | Population size | 30 |

| Wmax | Maximum iteration weight | 0.9 |

| Wmin | Minimum iteration weight | 0.4 |

| c1 and c2 | Acceleration factors c1 and c2 | 1 and 2 |

| r1 and r2 | Uniformly distribute random factors r1 and r2 | 1 |

| LB | Variables low bound | −10 |

| UB | Variables high bound | 10 |

| Maxiter | Maximum number of iterations | 100 |

| Parameter Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Partition type | Grid Partition |

| Membership Function type | gaussmf |

| Number of membership functions per input | 3 |

| Number of input parameters per ANFIS | 12 |

| Number of output parameters per ANFIS | 27 |

| Output type of ANFIS | linear |

| Number of total parameters per ANFIS | 39 |

| Number of total parameters of MANFIS | 117 |

| Number of MANFIS inputs (error (e) and change of error (∆e)) | 2 |

| Number of MANFIS outputs (∆Kp, ∆Ki, and ∆Kd) | 3 |

| MANFS Outputs | Description | Output Range | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | |||

| ∆Gain | Delta gain | 0 | 0.02 | unitless |

| ∆Ti | Delta integral time | 0 | 300 | millisecond |

| ∆Td | Delta derivative time | 0 | 100 | millisecond |

| Controller Response | Performance Metrics | Set Point (rpm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1000 | 1500 | ||

| Without Dynamic tuning | Rise time (s) | 92.6940 | 91.9866 | 93.0124 |

| Settling time (s) | 162.5888 | 162.9375 | 165.2766 | |

| Overshot (%) | 0.0075 | 0.0036 | 0.0012 | |

| Peak (rpm) | 478.2085 | 975.2075 | 1472.7 | |

| Peak time (s) | 376 | 491 | 620 | |

| With Dynamic tuning | Rise time (s) | 69.1531 | 70.8270 | 70.9758 |

| Settling time (s) | 121.2942 | 124.4630 | 128.8376 | |

| Overshot (%) | 0.0021 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peak (rpm) | 480.1349 | 975.8206 | 1472.8 | |

| Peak time (s) | 228 | 307 | 357 | |

| Tuner | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set Point = 500 rpm | Set Point = 1000 rpm | Set Point = 1500 rpm | ||||

| MANFIS | PSO-MANFIS | MANFIS | PSO-MANFIS | MANFIS | PSO-MANFIS | |

| ∆Gain | 0.003193 | 0.001365 | 0.00328164 | 0.001237 | 0.003277 | 0.00088 |

| ∆Ti | 0.048519 | 0.0210946 | 0.0498292 | 0.0185033 | 0.049777 | 0.0138208 |

| ∆Td | 0.015457 | 0.00641789 | 0.0158784 | 0.0055555 | 0.01588 | 0.00406703 |

| MANFIS | 0.067168 | 0.02887749 | 0.06898924 | 0.0252958 | 0.068934 | 0.01876783 |

| Metric | Condition | 500 rpm | 1000 rpm | 1500 rpm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rise time (s) | Conventional | 92.7 ± 1.4 (CV = 1.5%) | 92.0 ± 1.1 (CV = 1.2%) | 93.0 ± 1.6 (CV = 1.7%) |

| PSO-MANFIS | 69.2 ± 0.9 (CV = 1.3%) | 70.8 ± 1.0 (CV = 1.4%) | 71.0 ± 1.2 (CV = 1.7%) | |

| Settling time (s) | Conventional | 162.6 ± 2.5 (CV = 1.5%) | 162.9 ± 2.0 (CV = 1.2%) | 165.3 ± 2.3 (CV = 1.4%) |

| PSO-MANFIS | 121.3 ± 1.8 (CV = 1.5%) | 124.5 ± 1.7 (CV = 1.4%) | 128.8 ± 2.1 (CV = 1.6%) | |

| Overshoot (%) | Conventional | 0.0075 ± 0.0004 | 0.0036 ± 0.0002 | 0.0012 ± 0.0001 |

| PSO-MANFIS | 0.0021 ± 0.0002 | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 |

| Ref. | Rise Time (s) | Settling Time (s) | Overshoot (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | Imp. | From | To | Imp. | From | To | Imp. | |

| [13] | 0.5 | 1.7 | −240% | 5 | 2 | 60% | 60 | 0.8 | 98% |

| [14] | 54 | 58 | −7% | 113 | 118 | −4% | 0.94 | 0.79 | 16% |

| [15] | 6.6795 | 6.6668 | 0% | 179.4489 | 179.4476 | 0% | 33.0258 | 33.1441 | 0% |

| [16] | x | x | 192 | 35 | 81% | 23 | 0 | 100% | |

| [17] | 0.3208 | 0.2503 | 21% | 10.7258 | 10.4824 | 2% | 3.4393 | 2.5079 | 27% |

| [18] | 156.93 | 76 | 51% | x | x | no | 10 | 0 | 100% |

| [19] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [20] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [21] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [22] | 0.2495 | 0.0789 | 68% | 1.4306 | 0.1338 | 90% | 18.4705 | 0.9418 | 94% |

| [23] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [24] | 10.7 | 0.881 | 91% | 206 | 1.7 | 99% | 24.3 | 0.103 | 99% |

| [25] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [26] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [27] | x | x | no | 1.35 | 2.95 | −118% | 45.6 | 1.5 | 96% |

| [28] | x | x | no | 20 | 6 | 70% | 3.8 | 1.66 | 56% |

| [29] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [30] | x | x | no | 1.7 | 1.62 | 2% | 160.3 | 157.25 | 5% |

| [31] | x | x | no | x | x | no | x | x | no |

| [32] | 7.4786 | 5.1719 | 30% | 3.5006 | 1.1200 | 68% | 0.5465 | 0.2582 | 52% |

| [cs] | 93.0124 | 70.9758 | 23% | 165.2766 | 128.8376 | 22% | 0.0012 | 0 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Najari, B.; Hen, C.K.; Siaw Paw, J.K.; Marhoon, A.F. Dynamic Tuning of PLC-Based Built-In PID Controller Using PSO-MANFIS Hybrid Algorithm via OPC Server. Automation 2025, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040083

Al-Najari B, Hen CK, Siaw Paw JK, Marhoon AF. Dynamic Tuning of PLC-Based Built-In PID Controller Using PSO-MANFIS Hybrid Algorithm via OPC Server. Automation. 2025; 6(4):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040083

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Najari, Basim, Chong Kok Hen, Johnny Koh Siaw Paw, and Ali Fadhil Marhoon. 2025. "Dynamic Tuning of PLC-Based Built-In PID Controller Using PSO-MANFIS Hybrid Algorithm via OPC Server" Automation 6, no. 4: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040083

APA StyleAl-Najari, B., Hen, C. K., Siaw Paw, J. K., & Marhoon, A. F. (2025). Dynamic Tuning of PLC-Based Built-In PID Controller Using PSO-MANFIS Hybrid Algorithm via OPC Server. Automation, 6(4), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040083