Acute Effects of Whole-Body Electromyostimulation Versus High-Intensity Resistance Training on Markers of Bone Turnover in Young Females—A Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

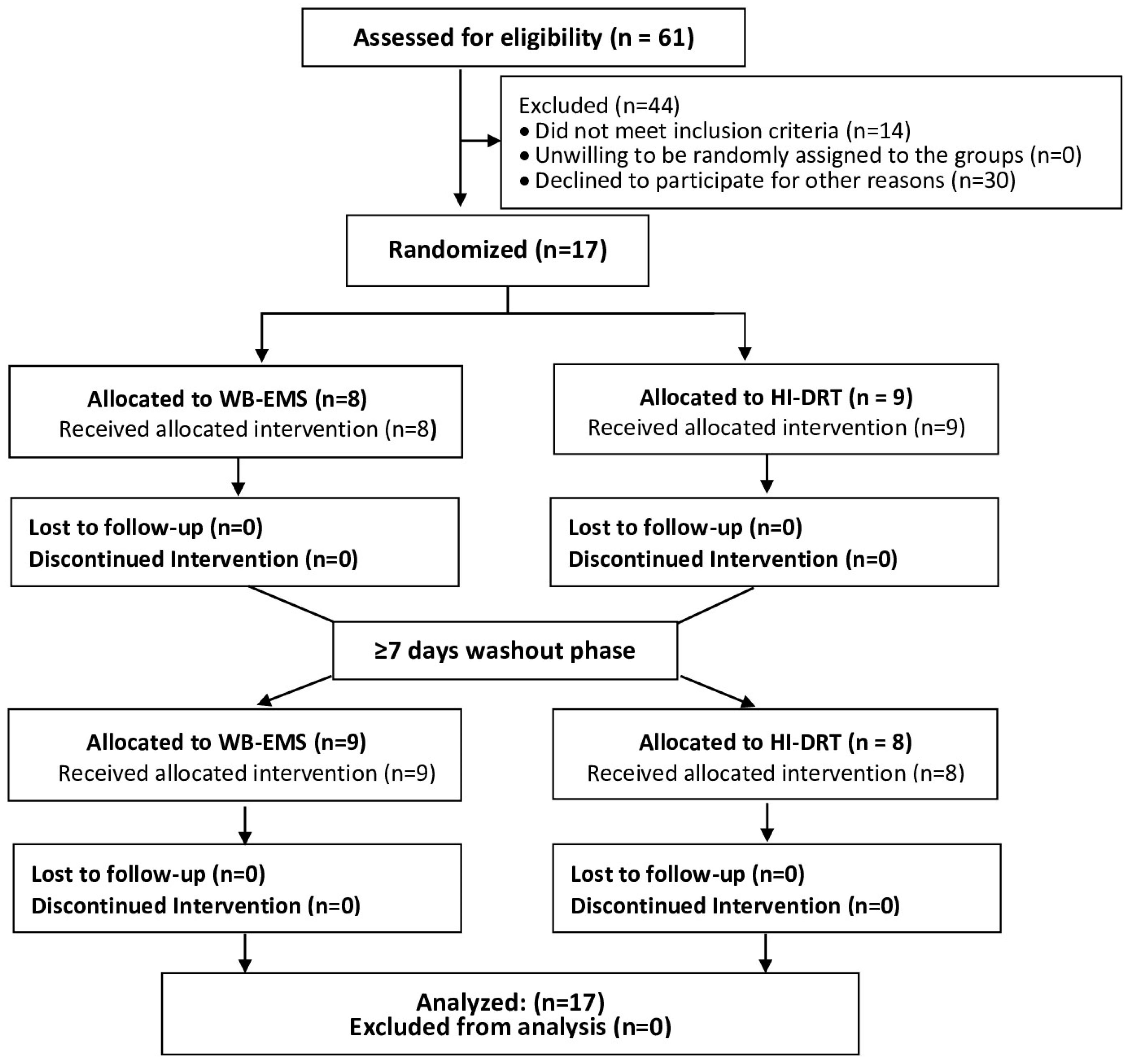

2.2. Randomization and Blinding

2.3. Main Outcomes

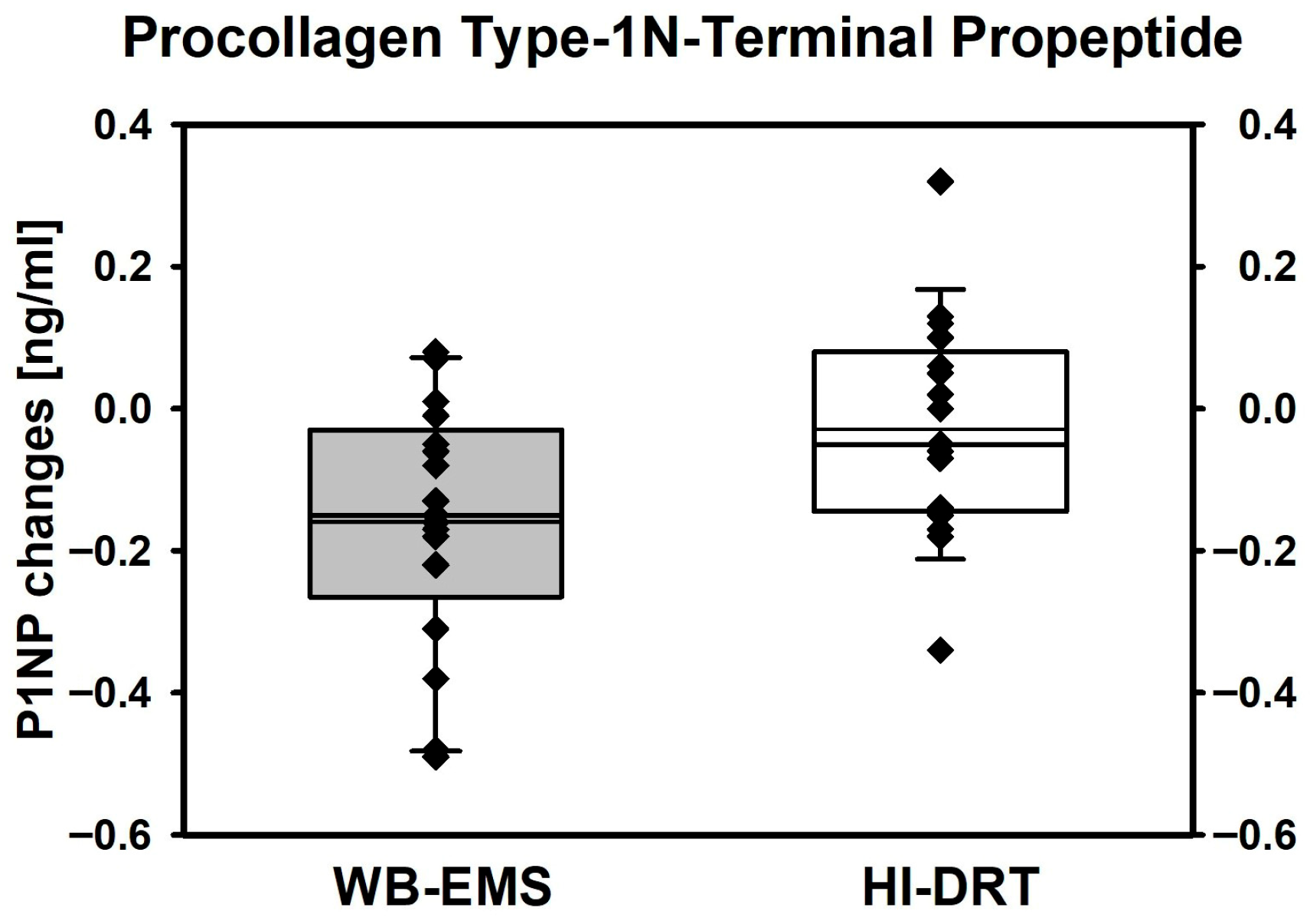

- Differences in acute changes in total P1NP from baseline to 15 min post exercise between HI-DRT and WB-EMS.

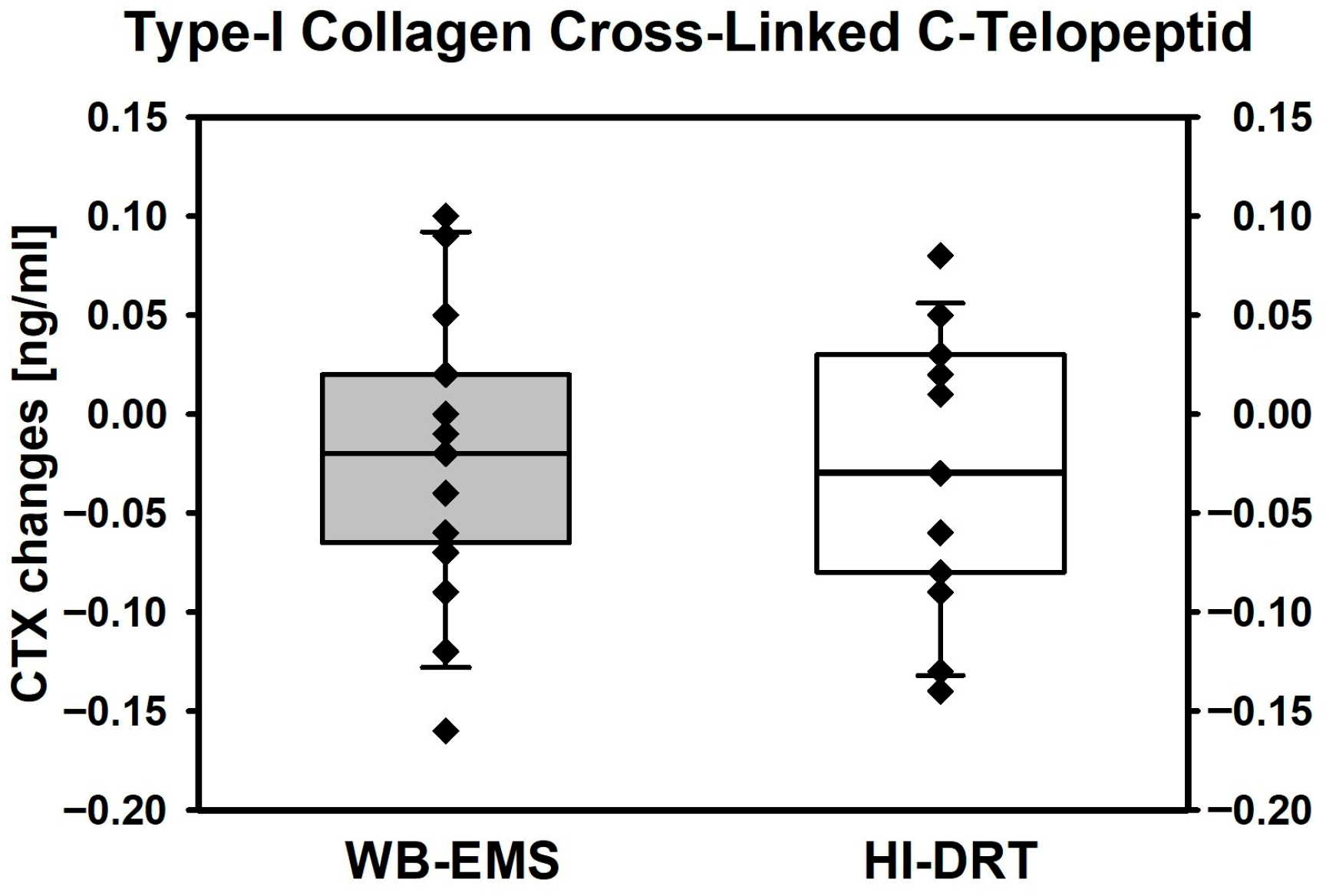

- Differences in acute changes in CTX from baseline to 15 min post exercise between HI-DRT and WB-EMS.

2.4. Assessments

2.4.1. Participant Characteristics

2.4.2. Bone Turnover Markers

2.5. Study Intervention

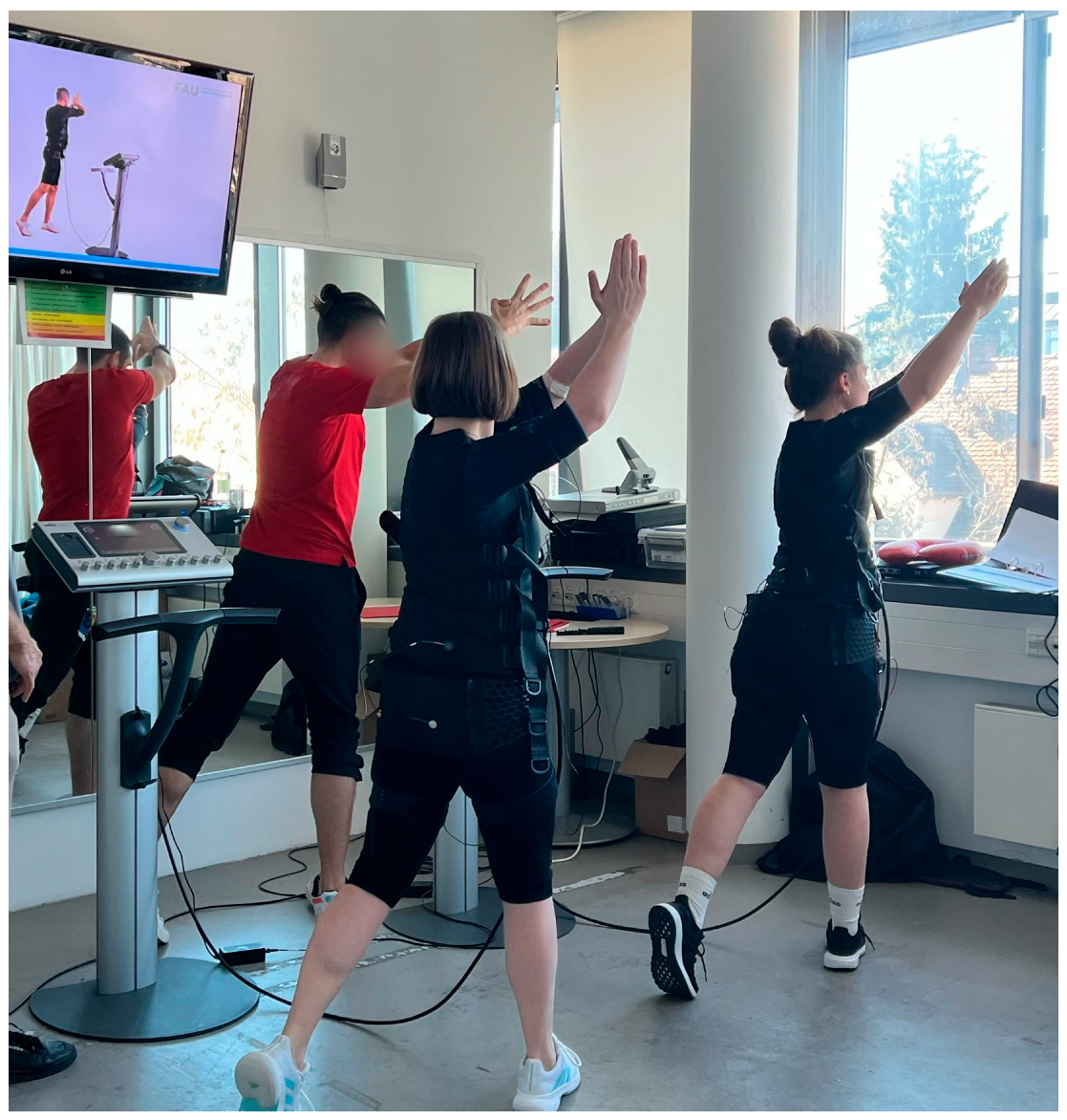

2.5.1. Whole-Body Electromyostimulation

2.5.2. High-Intensity Resistance Exercise

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Intervention Characteristics

3.2.1. Compliance and Safety Aspects

3.2.2. Perceived Exertion, Exercise Intensity

3.3. Study Outcomes

3.4. Confounders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1RM | One Repetition Maximum |

| 95%-CI | 95% Confidence Interval |

| BMD | Bone Mineral Density |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CR-10 scale | Category Ratio Scale 10 |

| CTX | Type-I Collagen Cross-Linked C-Telopeptide |

| DSM-BIA | Direct Segmental Multi-Frequent Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| EDTA | Ethylenediamine Tetra-acetic Acid |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| HI-DRT | High-Intensity Dynamic Resistance Exercise Training |

| MV | Mean Value |

| P1NP | Procollagen Type-1 N-Terminal Propeptide |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RM | Repetition Maximum |

| RPE | Rate of Perceived Exertion |

| RTF | Repetitions to Fatigue |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| WB-EMS | Whole-Body Electromyostimulation |

References

- Kemmler, W.; Bebenek, M.; von Stengel, S.; Bauer, J. Peak-bone-mass development in young adults: Effects of study program related levels of occupational and leisure time physical activity and exercise. A prospective 5-year study. Osteoporos. Int. 2015, 26, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Lyle, R.M.; Weaver, C.M.; McCabe, L.D.; McCabe, G.P.; Johnston, C.C.; Teegarden, D. Peak spine and femoral neck bone mass in young women. Bone 2003, 32, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, C.; Goltzman, D.; Langsetmo, L.; Joseph, L.; Jackson, S.; Kreiger, N.; Tenenhouse, A.; Davison, K.S.; Josse, R.G.; Prior, J.C.; et al. Peak bone mass from longitudinal data: Implications for the prevalence, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hereford, T.; Kellish, A.; Samora, J.B.; Reid Nichols, L. Understanding the importance of peak bone mass. J. Pediatr. Soc. N. Am. 2024, 7, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gießing, J. HIT-Hochintensitätstraining; Novagenics-Verlag: Arnsberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmler, W.; Teschler, M.; Weissenfels, A.; Bebenek, M.; Frohlich, M.; Kohl, M.; von Stengel, S. Effects of Whole-Body Electromyostimulation versus High-Intensity Resistance Exercise on Body Composition and Strength: A Randomized Controlled Study. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2016, 2016, 9236809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stengel, S.; Bebenek, M.; Engelke, K.; Kemmler, W. Whole-Body Electromyostimulation to Fight Osteopenia in Elderly Females: The Randomized Controlled Training and Electrostimulation Trial (TEST-III). J. Osteoporos. 2015, 2015, 643520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.X.; Lam, H.; Ferreri, S.; Rubin, C. Dynamic skeletal muscle stimulation and its potential in bone adaptation. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2010, 10, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, B.R.; Daly, R.M.; Singh, M.A.; Taaffe, D.R. Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2016, 20, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmler, W.; Kohl, M.; Jakob, F.; Engelke, K.; von Stengel, S. Effects of High Intensity Dynamic Resistance Exercise and Whey Protein Supplements on Osteosarcopenia in Older Men with Low Bone and Muscle Mass. Final Results of the Randomized Controlled FrOST Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmler, W.; von Stengel, S.; Kohl, M. Exercise frequency and bone mineral density development in exercising postmenopausal osteopenic women. Is there a critical dose of exercise for affecting bone? Results of the Erlangen Fitness and Osteoporosis Prevention Study. Bone 2016, 89, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitzmann, A.L.; Shojaa, M.; Kast, S.; Kohl, M.; von Stengel, S.; Borucki, D.; Gosch, M.; Jakob, F.; Kerschan-Schindl, K.; Kladny, B.; et al. The effect of different training frequency on bone mineral density in older adults. A comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone 2022, 154, 116230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, E.F. Cellular mechanisms of bone remodeling. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2010, 11, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, E.; Dumas, A.; Keane, K.M.; Bestetti, G.; Freitas, L.H.M.; Gualano, B.; Kohrt, W.M.; Kelley, G.A.; Pereira, R.M.R.; Sale, C.; et al. The Bone Biomarker Response to an Acute Bout of Exercise: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 2889–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Tacey, A.; Mesinovic, J.; Scott, D.; Lin, X.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Lewis, J.R.; Duque, G.; Levinger, I. The effects of acute exercise on bone turnover markers in middle-aged and older adults: A systematic review. Bone 2021, 143, 115766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovárová, J.; Hamar, D.; Sedliak, M.; Cvecka, J.; Schickhofer, P.; Bohmerova, L. Acute response of bone metabolism to various resistance exercises in women. Acta Fac. Educ. Phys. Univ. Comen. 2015, 55, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltun, K.J.; Sterczala, A.J.; Sekel, N.M.; Krajewski, K.T.; Martin, B.J.; Lovalekar, M.; Connaboy, C.; Flanagan, S.D.; Wardle, S.L.; O’Leary, T.J.; et al. Effect of acute resistance exercise on bone turnover in young adults before and after concurrent resistance and interval training. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e15906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, E.; Kaijser, L. A comparison between three rating scales for perceived exertion and two different work tests. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2006, 16, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, J.; Fisher, J.; Giessing, J.; Gentil, P. Clarity in Reporting Terminology and Definitions of Set End Points in Resistance Training. Muscle Nerve 2017, 10, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R_Development_Core_Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dwan, K.; Li, T.; Altman, D.G.; Elbourne, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised crossover trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. The Borg CR Scales® Folder; Perception, B., Ed.; Hasselby: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsuda, Y.; Wada, T.; Noma, H.; Osaki, M.; Hagino, H. Impact of high-load resistance training on bone mineral density in osteoporosis and osteopenia: A meta-analysis. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2021, 39, 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn-St. James, M.; Caroll, S. High intensity resistance training and postmenopausal bone loss: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, R.M.; Dalla Via, J.; Duckham, R.L.; Fraser, S.F.; Helge, E.W. Exercise for the prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: An evidence-based guide to the optimal prescription. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 23, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prawiradilaga, R.S.; Madsen, A.O.; Jorgensen, N.R.; Helge, E.W. Acute response of biochemical bone turnover markers and the associated ground reaction forces to high-impact exercise in postmenopausal women. Biol. Sport. 2020, 37, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombos, G.C.; Bajsz, V.; Pek, E.; Schmidt, B.; Sio, E.; Molics, B.; Betlehem, J. Direct effects of physical training on markers of bone metabolism and serum sclerostin concentrations in older adults with low bone mass. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erben, R.G. Hypothesis: Coupling between Resorption and Formation in Cancellous bone Remodeling is a Mechanically Controlled Event. Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robling, A.G.; Turner, C.H. Mechanical signaling for bone modeling and remodeling. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2009, 19, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherk, V.D.; Wherry, S.J.; Barry, D.W.; Shea, K.L.; Wolfe, P.; Kohrt, W.M. Calcium Supplementation Attenuates Disruptions in Calcium Homeostasis during Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1437–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohrt, W.M.; Wolfe, P.; Sherk, V.D.; Wherry, S.J.; Wellington, T.; Melanson, E.L.; Swanson, C.M.; Weaver, C.M.; Boxer, R.S. Dermal Calcium Loss Is Not the Primary Determinant of Parathyroid Hormone Secretion during Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemant, J.; Accarie, C.; Peres, G.; Guillemant, S. Acute effects of an oral calcium load on markers of bone metabolism during endurance cycling exercise in male athletes. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2004, 74, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, K.B.; Brooks, M.A. A Systematic Review of Bone Health in Cyclists. Sports Health 2011, 3, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedillas, H.; Gonzalez-Aguero, A.; Moreno, L.A.; Casajus, J.A.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G. Cycling and bone health: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, E. Bone modeling and remodeling. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2009, 19, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.; Naylor, K.; Hoyle, N.R.; Eastell, R.; Leary, E.T.; National Bone Health Alliance Bone Turnover Marker Project. Use of CTX-I and PINP as bone turnover markers: National Bone Health Alliance recommendations to standardize sample handling and patient preparation to reduce pre-analytical variability. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 2541–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schini, M.; Vilaca, T.; Gossiel, F.; Salam, S.; Eastell, R. Bone Turnover Markers: Basic Biology to Clinical Applications. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 417–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Taljaard, M.; Van den Heuvel, E.R.; Levine, M.A.; Cook, D.J.; Wells, G.A.; Devereaux, P.J.; Thabane, L. An introduction to multiplicity issues in clinical trials: The what, why, when and how. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perneger, T.V. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ 1998, 316, 1236–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | MV ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age [years] 1 | 26.5 ± 4.0 | 21–34 |

| Age of menarche [years] 1 | 12.8 ± 1.0 | 12–15 |

| Body height [cm] | 169 ± 3 | 160–173 |

| Body mass [kg] 2 | 61.3 ± 6.6 | 50.7–70.7 |

| Lean body mass [kg] 2 | 47.7 ± 2.8 | 39.1–51.4 |

| Total body fat [%] 2 | 24.9 ± 6.7 | 13.2–36.6 |

| 1RM leg press [kg] 3 | 130 ± 29 | 95–192 |

| 1RM latissimus pulleys [kg] 3 | 37.4 ± 5.1 | 30.0–47.5 |

| Exercise participation [n] 1 | 15 | ------------ |

| Endurance type exercise [n] 1 | 8 | ------------ |

| Resistance type exercise [n] 1 | 4 | ------------ |

| Exercise frequency [sessions/w] 1 | 1.5 ± 1.4 | 0–4 |

| Diseases [n] 1 | 0 | ------------ |

| Medication [n] 1 | 0 | ------------ |

| Smokers [n] 1 | 1 | ------------ |

| HI-DRT MV ± SD | WB-EMS MV ± SD | Adjusted Difference MV (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type-I Collagen Cross-Linked C-Telopeptide (CTX) [ng/mL] | ||||

| Baseline | 0.264 ± 0.094 | 0.281 ± 0.103 | ------------ | ------ |

| Changes | −0.029 ± 0.066 0.091 | −0.020 ± 0.068 0.244 | 0.014 (−0.029, 0.057) | 0.509 |

| Procollagen Type-1 N-Terminal Propeptide (P1NP) [ng/mL] | ||||

| Baseline | 6.55 ± 0.77 | 6.60 ± 0.82 | ------------ | ------ |

| Changes | −0.003 ± 0.15 0.446 | −0.16 ± 0.17 0.002 | −0.13 (−0.230, −0.024) | 0.019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stimpfig, S.; Kob, R.; Kohl, M.; von Stengel, S.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Uder, M.; Kemmler, W. Acute Effects of Whole-Body Electromyostimulation Versus High-Intensity Resistance Training on Markers of Bone Turnover in Young Females—A Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Trial. Osteology 2025, 5, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040033

Stimpfig S, Kob R, Kohl M, von Stengel S, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Uder M, Kemmler W. Acute Effects of Whole-Body Electromyostimulation Versus High-Intensity Resistance Training on Markers of Bone Turnover in Young Females—A Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Trial. Osteology. 2025; 5(4):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040033

Chicago/Turabian StyleStimpfig, Sarah, Robert Kob, Matthias Kohl, Simon von Stengel, Barbara Obermayer-Pietsch, Michael Uder, and Wolfgang Kemmler. 2025. "Acute Effects of Whole-Body Electromyostimulation Versus High-Intensity Resistance Training on Markers of Bone Turnover in Young Females—A Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Trial" Osteology 5, no. 4: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040033

APA StyleStimpfig, S., Kob, R., Kohl, M., von Stengel, S., Obermayer-Pietsch, B., Uder, M., & Kemmler, W. (2025). Acute Effects of Whole-Body Electromyostimulation Versus High-Intensity Resistance Training on Markers of Bone Turnover in Young Females—A Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Trial. Osteology, 5(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040033