Abstract

Spiral finned tube heat exchangers are extensively used in petrochemical, power electronics, and metallurgical industries due to their high efficiency and compact design. However, fouling accumulation during operation significantly reduces heat transfer efficiency and increases pressure loss. This study develops a hybrid approach integrating discrete element method (DEM), finite element analysis (FEA), and HTRI Xchanger Suite 7 software to correlate fouling thickness with thermal performance and establish a prediction model for tube-side outlet temperature under varying conditions. DEM simulations analyze dust deposition patterns and determine equivalent fouling thickness distribution. A fouling-integrated FE model then evaluates how fouling thickness affects both heat transfer and flow resistance coefficients. Through orthogonal experimental design considering fouling thickness, ambient temperature, and inlet air velocity, thermal resistance values calculated from FEA are imported into HTRI to predict outlet temperature. A random forest algorithm is subsequently employed to develop a multivariable prediction model. Validation conducted on a spiral finned tube heat exchanger at Chongqing Xiangguosi Underground Gas Storage Co., Ltd. (Chongqing, China) confirmed close agreement between simulated and actual fouling patterns. The maximum relative error of the predicted outlet temperatures on the testing dataset was 0.1869%, demonstrating the proposed method’s potential to support performance evaluation and operational optimization of fouled heat exchangers.

1. Introduction

Heat exchangers serve as critical equipment for heat transfer in industrial applications, and are widely used in fields such as petroleum, natural gas, and electronic devices [1,2]. With prolonged system operation, airborne dust particles continuously deposit on the heat exchanger surface, leading to the phenomenon known as “fouling”. Such fouling not only significantly increases the thermal resistance of the heat exchanger and reduces heat transfer efficiency, but may also cause blockage of flow channels, increase pressure drop, and further impair system stability and energy efficiency [3,4]. Therefore, in-depth research on the fouling formation mechanism and distribution characteristics of heat exchangers, along with the development of accurate and reliable simulation models and parameter evaluation systems, holds important theoretical significance and engineering application value for improving heat transfer performance, optimizing energy consumption, and extending equipment service life.

It has been reported that more than 90% of heat exchange (HE) systems suffer from varying degrees of fouling [5]. The associated economic losses are considerable, accounting for approximately 0.25% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in highly industrialized countries [6]. In the United States alone, the annual cost of fouling is estimated at 0.1–1.2 billion USD, accompanied by an additional emission of about 2.2 million tons of CO2 each year [7]. Experimental investigations on seawater fouling in thermal recovery systems of power plants have further demonstrated that, compared with a clean plate heat exchanger, fouling-induced thermal resistance can reduce the overall heat transfer coefficient by 21.3% [8]. These findings indicate that, although fouling may not always cause an immediate and drastic loss of thermal efficiency, its long-term cumulative effects and associated maintenance costs remain significant and cannot be neglected.

In existing research, there has been growing attention among scholars toward fouling on the air side of heat exchangers. Regarding the analysis of fouling effects, some researchers have adopted experimental testing methods to conduct investigations. Bell et al. [9] investigated the performance of plate-fin and microchannel heat exchangers under different dust conditions. They found that ASHRAE standard dust significantly increased the air-side pressure drop in microchannel heat exchangers, while Arizona dust primarily reduced their heat transfer efficiency. Lebele-Alawa et al. [10] experimentally evaluated the impact of fouling on three heat exchanger units in a polyethylene production facility. The results indicated that the overall heat transfer coefficient of the exchangers decreased by 51.60% compared to the design value, and the primary heat exchanger experienced a severe reduction in performance, with its heat load and heat transfer coefficient declining significantly by 86.39% and 80.71%, respectively. In a study by Xu et al. [11], fouling experiments were conducted on air conditioning systems equipped with louvered-fin and wavy-fin microchannel heat exchangers. After three months of operation in a factory environment, the cooling capacity decreased by 23% and 17.2%, and the coefficient of performance (COP) declined by 49.5% and 35.6%, respectively.

However, physical experiments are often associated with high costs, extended durations, and significant consumption of human and material resources. Moreover, it is often impractical to conduct shutdown tests in large-scale heat exchange stations. These limitations have prompted researchers to turn to numerical simulation methods. Välikangas et al. [12] employed a LES-DEM soft-sphere model to numerically analyze the volumetric fouling rate in two types of heat exchangers under varying Reynolds numbers, particle sizes, and adhesive particle types. They found that the collection efficiency for highly adhesive particles increased monotonically with the Stokes number and Reynolds number, whereas that for particles with low adhesiveness exhibited a non-monotonic trend. Sun et al. [13] took into account changes in tube structure caused by particle adhesion-deposition and intermittent shear re-suspension. By employing a fluid–structure interaction approach based on dynamic mesh technology, they systematically investigated particle-wall interactions and the consequent influence on thermal resistance. Hu et al. [14] applied a discrete particle model combined with a deposition model to predict the movement and deposition behavior of graphite dust. This study indicated that in a staggered arrangement of heat exchanger tube bundles, the Nusselt number increased by 27.90–29.17%, while the deposition rate decreased by 1.52–3.15%, compared to an in-line arrangement.

Furthermore, to predict the performance degradation of heat exchangers caused by dust accumulation, researchers have employed machine learning methods to develop rapid prediction models based on experimental or simulated data. He et al. [15] proposed a surrogate model for fouling prediction in industrial heat exchangers by combining machine learning with computational fluid dynamics (CFD). Three-dimensional numerical simulations were conducted under various fouling levels to train four neural networks: backpropagation neural network (BPNN), particle swarm optimization-enhanced BPNN (PSO-BPNN), convolutional neural network (CNN), and radial basis function neural network (RBFNN). All models achieved a root mean square error (RMSE) of less than 10−7 K/W. Hou et al. [16] simulated fouling on the cold side of a plate heat exchanger using a MATLAB R2024a-based program to alter its outlet temperature. Based on these simulated data, a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network was employed to monitor the health status of the heat exchanger. Strzelczyk et al. [17] introduced a synthetic image dataset simulating the accumulation of dust and particulate matter on heat exchanger surfaces, which was used to train CNNs, including UNet, UNet++, and CGNet, achieving an optimal balance between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency.

The impact of fouling on heat exchanger performance has been the subject of considerable academic interest. Extensive investigations have been conducted through experimental measurements, numerical simulations, and data-driven approaches to explore the formation mechanisms, characteristics, and impacts of fouling on thermal performance. However, current research has predominantly focused on variations in cold-side heat transfer characteristics, while the complex coupling mechanisms between internal thermal-flow behavior and dust deposition within heat exchangers remain inadequately explored. In practical operation, fouling not only reduces the heat transfer efficiency on the cold side, but may also alter the airflow distribution, temperature profile, and heat transfer pathways, thereby further compromising the overall thermal performance and energy consumption characteristics of the heat exchanger. Consequently, a thorough understanding of the interactions between fouling and the internal thermal-flow field is crucial for enhancing the long-term operational stability and energy efficiency of heat exchangers.

In this study, a hybrid simulation framework integrating the Discrete Element Method (DEM), Finite Element Analysis (FEA), and HTRI software was developed to systematically investigate the effects of dust accumulation on the heat transfer performance of heat exchangers. The proposed DEM-FEA-HTRI hybrid framework achieves multi-physics coupling, enabling simultaneous consideration of particle motion, deposition morphology, thermal resistance variation, and flow-heat transfer interactions. This study first employs the discrete element method (DEM) to investigate the distribution patterns of dust particles in a spiral finned-tube heat exchanger bundle. Subsequently, finite element (FE) simulations are conducted to analyze the influence of equivalent fouling thickness on the overall thermal-hydraulic performance of the heat exchanger. To mitigate the high computational cost and time consumption associated with direct FE simulations of large-scale tube bundles, a hybrid approach integrating numerical simulation and data-driven modeling is proposed. Specifically, the fouling thermal resistance coefficient derived from FE simulations is incorporated into HTRI software to calculate the fluid outlet temperature of the tube bundle. Furthermore, a random forest-based surrogate model is developed to predict the outlet fluid temperature using input features including the fouling thickness, ambient temperature, and inlet air velocity. The proposed methodology offers an efficient and accurate alternative for predicting the performance of heat exchangers under various fouling conditions.

2. Fouling Deposition Analysis in a Spiral Finned-Tube Heat Exchanger Using the DEM

This study investigates the primary cooling system of a natural gas compression system at the Chongqing Xiangguosi Underground Gas Storage Co., Ltd. The cooled medium is methane, which enters the heat exchanger after compression under typical operating conditions with an inlet temperature of 85 °C and an inlet pressure of 15 MPa. The heat exchanger features a tube-bundle structure, with a single heat exchange tube having an effective axial length of 15 m. The tube arrangement consists of three rows, totaling 46 heat exchange tubes. The mass flow rate per tube is 0.21 kg/s.

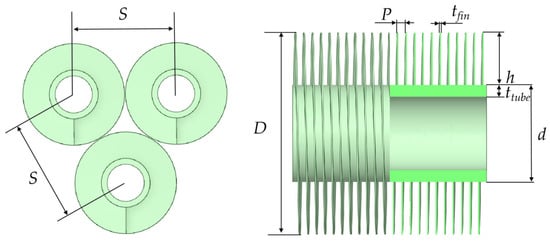

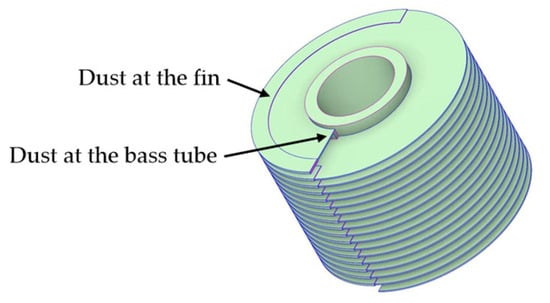

The spiral finned-tube heat exchanger bundle features a staggered tube arrangement. A schematic diagram of its three-dimensional configuration is presented in Figure 1, while detailed geometrical parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional model of the spiral finned-tube heat exchanger.

Table 1.

Geometrical parameters of the spiral finned-tube heat exchanger (unit: mm).

2.1. Theoretical Background of EDEM-Based Fouling Deposition Simulation

EDEM 2022 is a high-performance simulation software for granular materials based on the DEM. It enables the investigation of macroscopic behaviors of particulate systems under specific conditions by simulating interactions between large numbers of discrete particles, such as collisions, friction, and cohesion. This software is widely applied across various fields including mining, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, chemical engineering, and heavy machinery design.

This study utilizes the Johnson–Kendall–Roberts (JKR) contact model implemented in EDEM software to numerically simulate dust adhesion behavior in a spiral finned-tube heat exchanger. The Hertz–Mindlin with JKR cohesive contact model incorporates attractive forces between particles to characterize adhesion effects, making it suitable for simulating cohesive and adhesive interactions among both identical and distinct discrete elements [18]. Founded on the JKR theory, the model’s physical principles and numerical implementation have been further elaborated by Oleh Baran et al. [19]. Research confirms that the JKR contact model effectively represents interactions among cohesive particles. Within this framework, the normal elastic contact force is determined by the normal overlap, surface energy, and interactive properties between particles. The Hertz–Mindlin with JKR model employs the JKR normal elastic contact force FJKR, which is expressed in Equation (1), to quantify the interparticle cohesion:

where γ denotes the surface energy, E* represents the equivalent elastic modulus, a is the contact radius between two material particles, R* is the equivalent contact radius. The tangential overlap α is related to the nominal overlap δ as shown in Equation (2).

The expressions for E* and R* are defined as follows:

where E1 and E2 denote the elastic moduli of the two contacting material particles, ν1 and ν2 represent their respective Poisson’s ratios, and R1 and R2 correspond to the contact radii during the interaction.

When γ = 0, the normal elastic contact force FJKR is equivalent to the Hertz–Mindlin normal force and expressed in Equation (5).

In the JKR model, attractive (cohesive) forces can still manifest between particles even in the absence of direct physical contact. The model incorporates a maximum interparticle separation distance up to which non-zero cohesion exists. Under such conditions, the theoretical overlap between particles is negative, indicating no direct contact. This critical separation distance can be expressed as:

where δc denotes the maximum normal gap between a body surface and a particle in the presence of non-zero cohesion, while ac represents the maximum normal gap between particles under non-zero cohesive forces. When δ is less than δc (i.e., the interparticle distance is sufficiently large), the normal force is zero. When δ lies between δc and 0, a maximum cohesive force Fcmax described in Equation (7) occurs.

2.2. Analysis of Flouring Distribution Characteristics Based on EDEM Simulation

2.2.1. Configuration of Boundary Conditions in EDEM Simulations

To effectively simulate dust deposition characteristics while maintaining computational efficiency, a simplified model consisting of ten spiral-finned tubes was employed in this study, as illustrated in Figure 2. Each tube has a total length of 104 mm, with a 100-mm finned section and a 2-mm bare tube extension at each end. This extension was implemented to create a smooth transition zone at the fluid domain boundary, thereby preventing the generation of degenerate mesh elements, ensuring computational accuracy and stability, and effectively eliminating boundary effects. This configuration accurately represents the three-row tube arrangement of actual heat exchangers, significantly reduces computational expense while preserving the model’s representativeness and enhancing simulation efficiency. The computational domain covers the entire geometric model of the heat exchanger. Dust particles that move beyond this domain are considered to have escaped from the system and are thus excluded from further deposition and interaction calculations. In accordance with actual operating conditions, gravity was set to act vertically downward. To explicitly investigate the effect of gravity on particle motion and deposition behavior, particles were injected vertically upward. The injection velocity was set to 2 m/s, a representative average value within the simulated airflow range (1–4 m/s), to present a balanced case study where the interplay between inertial, drag, and gravitational forces is pronounced.

Figure 2.

Simplified computational model in EDEM software.

To accurately describe the contact interactions between dust particles and the finned-tube surfaces, JKR contact model was applied. This model accounts for both elastic deformation and adhesive effects during particle–wall and particle–particle collisions. When the adhesive force exceeded the particle’s inertia, the particle was assumed to deposit on the surface without rebound, effectively reproducing the adhesion and accumulation behavior of fine dust under realistic air–solid interaction conditions.

In most industrial environments, dust represents a predominant airborne contaminant primarily composed of fine solid particles, which far outnumber other types of fouling. The remaining fouling substances account for a relatively small proportion in practice and have limited impact on overall heat exchanger performance. Accordingly, spherical particles with a radius of 0.1 mm are selected to simulate dust particles in this study. This particle size is commonly used to investigate the deposition behavior of fine particles in airflow, corresponding to the typical size range of industrial dust and effectively representing fouling characteristics under realistic operating conditions [20]. Regarding the material selection, silicon dioxide (SiO2) was chosen as the representative dust component since it is one of the most prevalent constituents of industrial particulate matter. In the simulation, SiO2 microsphere agglomerates with a packing fraction of 0.7 were used to represent the dust particles, while the heat exchanger material was 304 stainless steel. The material properties of both the particles and stainless steel are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Material Property Settings.

To accurately simulate the interactions between the particles and the heat exchanger surface, the corresponding contact mechanical properties are defined in this study. The specific parameters are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameter settings for different contact pairs.

2.2.2. Analysis and Validation of Simulation Results for Dust Deposition Process

Figure 3a presents the numerical simulation result of dust deposition distribution on a spiral finned heat exchanger obtained using EDEM software. It can be observed that dust primarily accumulates on the tube surface, with particularly significant deposition on the windward side of the first-row spiral finned tubes. The actual fouling condition of the heat exchanger from the operational site, shown in Figure 3b, indicates that contaminants mainly adhere to the fin surfaces in the form of aggregated particles, while minimal fouling is observed in interstitial regions such as leaf or insect residues. Comparative analysis demonstrates a high consistency between the simulated dust deposition patterns and the actual observed distribution, validating the effectiveness of the DEM model. Furthermore, the dust distribution characteristics captured by the simulation reflect the airflow behavior under practical operating conditions, align with general principles of dust deposition, and further confirm the reliability and engineering applicability of the numerical model.

Figure 3.

Comparison between simulated and experimental results of dust deposition: (a) Simulated dust deposition pattern; (b) Experimental fouling distribution.

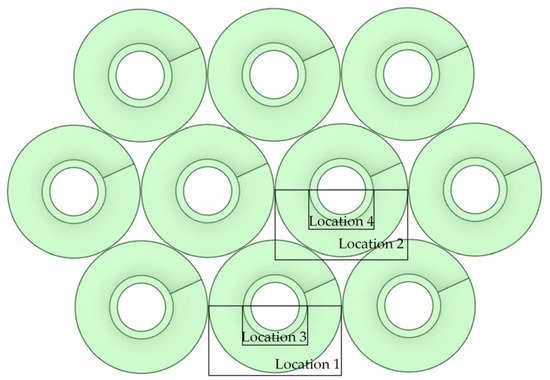

To accurately quantify dust deposition distribution across different structural parts of the heat exchanger, the model is divided into four representative regions based on its geometric configuration, as shown in Figure 4. These regions encompass the fin and base-tube areas of both the first and second layers. Specifically, Locations 1 and 2 indicate the dust deposition zones at the fin ends of the first and second layers, respectively, while Locations 3 and 4 represent the deposition zones at the base-tube ends of the first and second layers, respectively. A systematic statistical analysis of dust accumulation in each region was conducted, with particular emphasis on comparing the deposition patterns between the fin and base-tube regions across both layers.

Figure 4.

Regions for quantitative analysis of dust deposition.

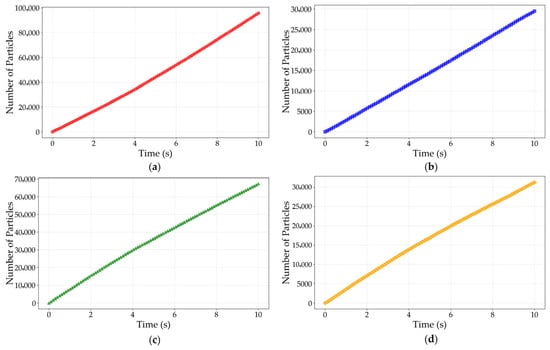

As illustrated in Figure 5, the results demonstrate an approximately linear increase in dust accumulation across all regions over time. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to an inherent characteristic of its structural design: the densely arranged fin configuration, which is intended to maximize the heat transfer area, enhances thermal performance but simultaneously acts as a physical barrier to the passage of particulate matter. As airflow organizes through the fin channels, dust particles are readily captured via mechanisms such as interception, inertial impaction, and surface adhesion. Consequently, with accumulated operation time, the continuous passage of air over the heat transfer surface causes the initially formed thin dust layer to progressively thicken and expand. Furthermore, the statistical results indicate that the dust deposition on both the fins and base tubes of the first layer is significantly higher than that of the second layer. This discrepancy can be attributed to the direct exposure of the first-layer structures to the primary airflow path, leading to enhanced particle capture and consequently more substantial dust accumulation.

Figure 5.

Temporal distribution of dust accumulation across different regions. (a) Location 1; (b) Location 2; (c) Location 3; (d) Location 4.

3. Performance Analysis of Finned-Tube Heat Exchanger Under Fouling Conditions

3.1. Numerical Modeling of Finned-Tube Heat Exchanger

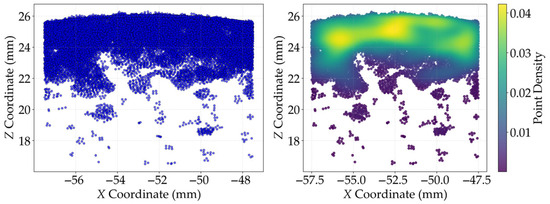

To analyze the effect of fouling on the thermal performance of the finned-tube heat exchanger using the finite element method, a rational representation of the dust distribution obtained from EDEM simulations is required. First, a statistical analysis of the spatial distribution characteristics of dust particles in the region of the bottom-layer fin tips was conducted. The specific approach involved projecting the dust particles onto the XZ cross-section, as illustrated in Figure 1, and calculating the number density of particles within discrete intervals along the Z direction. As shown in Figure 6, the statistical results indicate that with the center of the heat transfer tube as the origin, the particles are distributed relatively uniformly along the Z-axis within the interval of 22–26 mm, with only minor fluctuations in number density observed in this region. In contrast, within the 18–22 mm interval, the number density decreases significantly to a negligible level. Based on this distribution characteristic, the dust accumulation on the fin tips within the height range of 22–26 mm can be equivalently modeled as a layer of uniform thickness, while the dust deposition on the remaining fin surface is considered negligible and thus set to zero. This equivalent approach not only accurately reflects the spatial distribution characteristics of the actual dust deposition, but also provides a reasonable simplification for subsequent performance analysis.

Figure 6.

Distribution of dust particles on the bottom fin-tips projected along the XZ plane.

Moreover, since the dust accumulation is most pronounced at the tip of the first-layer fin (designated as Location 1), this study considers it as a critical region and defines a range of dust thickness values at this location for detailed analysis. To determine the number of dust particles corresponding to a given thickness at Location 1 and to further estimate the distribution characteristics and equivalent thicknesses at the other three designated orientations, a mathematical relationship is first established between the deposited dust volume and the equivalent thickness at each orientation. Based on the volume of a single dust particle and the statistically obtained number of particles at Location 1, the dust thickness at this location was inversely derived. Furthermore, by fitting trend curves to the dust distribution profiles across the four representative orientations, the number of particles corresponding to the other three orientations was extrapolated, and their respective equivalent thicknesses are subsequently determined. The detailed computational procedure is outlined as follows.

Step 1: Considering the mesh size and the fact that the inter-fin spacing is only 0.5 mm, the dust thickness range at Location 1 was set to 0.15 mm, 0.18 mm, 0.21 mm, and 0.24 mm. Using the equivalent dust volume V(1) corresponding to a given dust thickness at Location 1 and the volume of a single particle Vp, the corresponding number of dust particles N(1) was calculated. This relationship can be expressed as:

Step 2: Based on the number of dust particles at Location 1 and the fitted time–particle number curve f(1) shown in Figure 5a, the corresponding simulation time t* is determined using Equation (9). This time value is then used to calculate the number of dust particles at the remaining Locations as described in Equation (10).

Step 3: Establish the functional relationship φ for calculating the equivalent dust volume and thickness at other locations. The equivalent dust volume V(n) is derived based on the number of dust particles, which is then substituted into the corresponding Equation (11) to determine the equivalent dust thickness th(n).

Based on the specified dust layer thickness at Location 1, the corresponding dust thickness values calculated for other locations are summarized in Table 4. A helical finned-tube heat exchanger model with simulated dust deposition is subsequently developed, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Table 4.

Equivalent dust thickness at different locations (unit: mm).

Figure 7.

Numerical model of a helical finned-tube heat exchanger with simulated dust deposition.

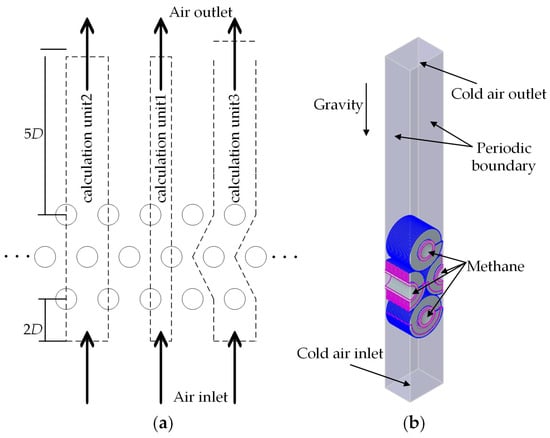

3.2. Boundary Conditions for Finite Element Simulation

To optimize the computational domain setup for reduced computational resource consumption while maintaining accuracy, three different computational unit configurations are considered in this study. Figure 8 illustrates the computational units and their corresponding domain schematics for the integral helical finned tube, with Figure 8a showing the arrangements of the staggered finned-tube bundle. Given that the finned tube contains multiple repeating units along the transverse direction and assuming that the incoming cold air is uniformly distributed transversely at the inlet, three types of simplified computational domains are commonly employed in existing studies, including calculation unit 1 [23], calculation unit 2 [24,25], and calculation unit 3 [26]. These approaches significantly reduce computational cost without compromising simulation accuracy.

Figure 8.

Descriptions about the calculation domains and the boundary conditions. (a) The fin and tube bundle arrangements for different calculation units; (b) Boundary conditions of the selected calculation unit.

In selecting a suitable computational unit, calculation unit 2 is deemed inapplicable to this study due to its nonconformity with periodic boundary conditions in the topologically structured transverse boundary surfaces. Calculation unit 3 is also excluded because the extremely small transverse and longitudinal spacings considered in this study resulted in geometric conflicts between the fluid domain and the fins. Therefore, calculation unit 1 is ultimately adopted for simulation analysis. To ensure uniform airflow distribution at the inlet, the length of the air inlet section is set to twice the fin outer diameter of the helical finned tube. Meanwhile, the outlet section length is set to five times the fin outer diameter to minimize backflow effects at the outlet. This design contributes to optimized fluid dynamic behavior and thermal exchange performance.

In this study, the heat exchanger is configured as follows: to reproduce the continuous arrangement of finned tubes in practical applications, the side surfaces of the computational domain were set as periodic boundary conditions. In this way, the model only needs to simulate a single representative unit to accurately infer the overall thermal–flow behavior under similar operating conditions. Methane was selected as the working fluid inside the tube. The inlet boundary was set as a mass flow inlet with a total mass flow rate of 0.21 kg/s. Considering the existence of periodic boundaries, there are two inlets corresponding to half of the total inlet area, so their mass flow rate was set to 0.105 kg/s. The inlet temperature of methane was 85 °C, and the outlet boundary was set as a pressure outlet with a gauge pressure of 0 Pa to simulate the pressure relief condition during actual operation. For the external air domain, air was used as the cooling medium. The inlet was set as a velocity inlet, and the outlet was set as a pressure outlet. All walls were defined as no-slip stationary walls to ensure that the interaction between airflow and solid surfaces conforms to the real convective heat transfer process.

To determine the appropriate turbulence model for this study, the flow regime of the external air was first evaluated by calculating the Reynolds number (Re) based on the characteristic velocity and fin outer diameter of the finned-tube bundle, as expressed by Equation (13):

where ρ is the density, u is the velocity and D is the characteristic length. Considering the minimum inlet velocity of 1 m/s, substituting the parameters into the equation yields a Reynolds number exceeding the critical threshold of 2300, indicating that the airflow around the fins is in a turbulent regime. Given the distinctly turbulent nature of the airflow entering the heat exchanger tube bundle, the SST k–omega turbulence model is employed in the simulation [27]. The main structure of the heat exchanger is constructed from 304 stainless steel. Table 5 provides the relevant material properties. To represent the continuous arrangement of finned tubes in practical applications, the side boundaries of the computational domain are set as periodic conditions. This configuration allows the model to simulate the performance of a single unit while effectively extrapolating the heat transfer and flow behavior of the overall structure under similar operating conditions.

Table 5.

Material properties employed in the simulation.

3.3. Mesh Independence Verification

During the meshing process of the heat exchanger model in Fluent Meshing, the poly-hexcore meshing method was adopted. This type of mesh is particularly suitable for simulating thin-walled finned-tube structures, as it effectively captures steep gradients near solid surfaces and minimizes numerical diffusion. Since stronger temperature and velocity gradients occur near the forced-convection heat transfer walls, a denser mesh was applied around the fluid–solid coupling regions to improve the simulation accuracy. Accordingly, boundary layer meshes were generated in these regions to accurately resolve near-wall flow behavior.

To ensure the accuracy and efficiency of the numerical simulations, a mesh independence verification was performed. Three mesh configurations with total element counts of 9.77 × 106, 10.86 × 106, and 12.19 × 106 were compared. The key output parameters, namely the air outlet temperature and the pressure drop between the inlet and outlet, are listed in Table 6. The results indicate that when the number of mesh elements exceeds 10.86 × 106, the variations in both air outlet temperature and pressure drop are less than 1%, demonstrating satisfactory grid independence. Therefore, the medium-density mesh (10.86 × 106 elements) was selected for subsequent simulations to balance computational cost and accuracy.

Table 6.

Mesh independence verification table.

3.4. Effect of Dust in Different Positions on Heat Exchange

To quantify the sensitivity of heat exchanger performance to non-uniform dust deposition, three scenarios were considered: (i) both locations—dust present at the fin tip and the fin root; (ii) fin-tip only; and (iii) fin-root only. For all cases, an equivalent dust model with a thickness of 0.15 mm (corresponding to Location 1) was adopted. The simulations were conducted under an air inlet velocity of 1 m/s and an ambient temperature of 10 °C, representing typical operating conditions in industrial environments.

The influence of dust accumulation at different positions was evaluated by analyzing the air-side outlet temperature, which reflects the variation in overall heat transfer efficiency under each deposition scenario. The corresponding air outlet temperatures for the three cases were 55.75 °C (both locations), 56.27 °C (fin-tip only), and 55.79 °C (fin-root only), as summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

The outlet temperatures for the three cases.

Taking the case i as the reference, the fin-tip only case increases by 0.52 °C, whereas the fin-root only case increases it by only 0.04 °C. The observed differences in outlet temperature indicate that dust deposition at different locations exerts distinct influences on heat transfer performance. Specifically, the fin tip region plays a dominant role in heat dissipation due to its large effective surface area and high local heat transfer coefficient. Once dust accumulates in this area, the effective heat transfer surface is rapidly covered, and the additional thermal resistance significantly suppresses local convection efficiency. In contrast, dust at the fin root region has a relatively minor impact because this area inherently contributes less to the overall heat transfer process and experiences weaker flow intensity. Consequently, non-uniform dust deposition—particularly concentrated at the fin tips—results in a more pronounced deterioration of the overall heat exchange performance.

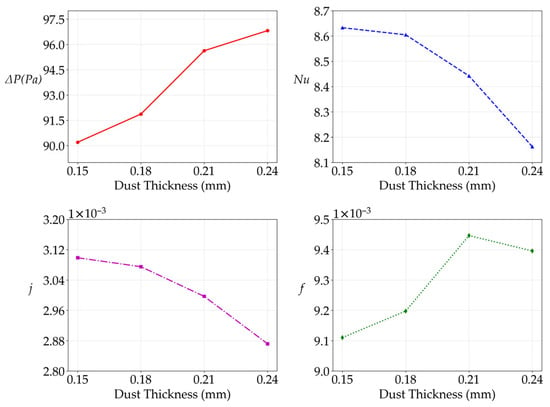

3.5. Effect of Fouling Layer Thickness on a Spiral Finned Tube Heat Exchanger Performance

To investigate the effect of dust deposition thickness on the performance of a spiral finned-tube heat exchanger, experiments were conducted at Location 1 with four different dust thicknesses: 0.15 mm, 0.18 mm, 0.21 mm, and 0.24 mm. The velocity and temperature of the cooling air were maintained at 3 m/s and 30 °C, respectively. The pressure drop ΔP between the inlet and outlet, Nusselt number (Nu), heat transfer factor (j-factor), and resistance factor (f-factor) were systematically analyzed under different dust deposition conditions [29]. Figure 9 presents the evaluated performance metrics of the heat exchanger across varying thickness conditions.

Figure 9.

Variations in performance metrics with different dust deposition thicknesses.

As the dust thickness increased, the pressure drop ΔP across the heat exchanger gradually rises, indicating that dust accumulation reduces the flow passage area and increases surface roughness, thereby enhancing flow resistance. In contrast, the Nusselt number and heat transfer factor decrease significantly with increasing dust thickness, suggesting that the dust layer introduce additional thermal resistance on the heat transfer surface and alter the flow boundary layer structure around the fins, consequently impairing convective heat transfer capacity.

4. Analysis and Prediction of Finned Heat Exchanger Outlet Temperature Under Multi-Variable Conditions via HTRI

4.1. Consistency Validation Between Finite Element Simulation and HTRI

Directly simulating the heat transfer performance of large-scale tube bundles using the finite element method presents significant challenges. These primarily arise from the substantial geometric scale and complex multi-physics coupling inherent in such FE models, which lead to an exponential increase in computational load and exceptionally high demands on both computational resources and time costs. Therefore, this study employs the industry-validated HTRI Xchanger Suite 7 (abbreviated as HTRI) for efficient computation of the tube bundle fluid outlet temperature under fouling conditions. HTRI is a powerful software package for the design and thermal calculation of heat exchangers. Its primary advantage lies in the use of extensive experimental data derived from industrial-scale heat transfer equipment for thermal performance computations, which significantly enhances the reliability and accuracy of the computed results. The software incorporates multiple modularized functions, enabling comprehensive design and optimization of heat exchangers. The resulting outputs are closely aligned with practical engineering requirements, making HTRI one of the prevailing tools in the field of heat exchanger design [30,31].

Based on the structural configuration of a shell-and-tube heat exchanger, the Air Cooler module of the HTRI software is utilized to perform the computation. Methane is defined as the hot-side gaseous fluid, while air is set as the cold-side gaseous coolant. The relevant parameters in HTRI, including geometry, fin specifications, tube layout, and operating conditions, are configured according to the heat exchanger parameters provided in Table 1.

Calculating the outlet fluid temperature of a tube bundle under fouling conditions using HTRI software requires prior knowledge of the thermal resistance corresponding to the specific deposit thickness. Therefore, this study proposes to first compute the thermal resistance coefficient based on FE simulation results, which is subsequently incorporated into HTRI software as an input parameter. Prior to implementing this methodology, consistency between the FE method and HTRI software must be verified under clean conditions to ensure the reliability of the cross-platform simulation approach.

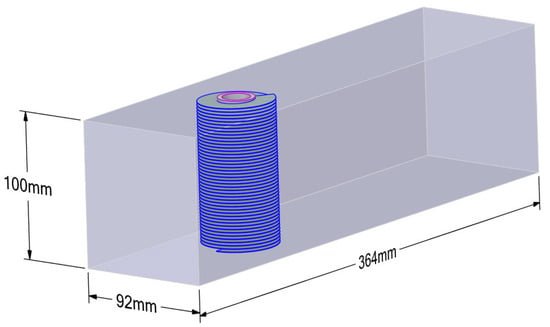

Given the limitations of computational resources in finite element simulations and the inability of the HTRI software to accurately predict the outlet temperature of short-tube heat exchangers, this study employs a FE approach to simulate a single heat exchange tube under dust-free conditions. A computational length of 100 mm is selected, and the three-dimensional model is illustrated in Figure 10. Subsequently, the outlet fluid temperature of a single tube with an effective length of 1 m is calculated using HTRI software, while the heat transfer process within the computational domain is monitored via the Tube side Monitor function. By applying a fitting curve, the outlet temperature for a 100 mm-long helical finned-tube heat exchanger is extrapolated. Finally, a comparative analysis is conducted to validate the consistency between the finite element simulation and the HTRI computational results.

Figure 10.

Computational model of a single heat exchanger tube channel with fluid domain.

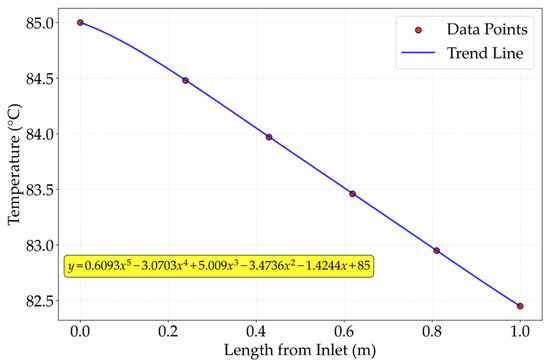

The lengths of both the inlet and outlet sections were set to twice and five times the fin outer diameter of the helical finned tube, respectively. The cold air velocity and inlet temperature were specified as 1 m/s and 10 °C. The methane outlet temperature obtained from the finite element simulation was 84.8207 °C. The HTRI calculation results are presented in Figure 11. By applying a fitting curve, the outlet temperature of a single helical finned-tube heat exchanger with a length of 100 mm was extrapolated as 84.8195 °C. This corresponds to an absolute error of 0.0012 °C and a relative error of 0.0014% compared to the finite element result, indicating a high level of consistency between the two methods.

Figure 11.

Outlet temperature and fitting curve of a single heat exchanger based on HTRI calculation.

To validate the effectiveness of the HTRI-based equivalent computation under dust-fouling conditions, dust layers with thicknesses of 0.15 mm and 0.997 mm were applied to the fin end and the base tube end, respectively, of the model illustrated in Figure 10. The FE simulation yielded a methane outlet temperature of 84.8322 °C. The fouling thermal resistance, Rf, was subsequently calculated using the thermal resistance formula from Ref. [32]:

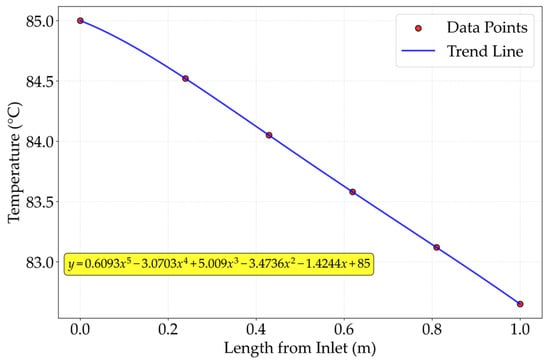

where Uf and Uclean denote the overall heat transfer coefficients with and without fouling, respectively. This calculated Rf value was then input into the HTRI software to establish a fitted correlation for the methane outlet temperature under fouled conditions, as presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Fitting curve of methane outlet temperature under fouling conditions based on HTRI.

By applying the fitting curve, the outlet temperature for a 100 mm-long helical finned-tube heat exchanger under fouling conditions was determined to be 84.8275 °C. Compared with the FE result 84.8322 °C, the absolute error is 0.0047 °C and the relative error is 0.0055%, confirming excellent consistency between the FE simulation and the HTRI method in the presence of fouling.

4.2. Impact of Fouling Thickness on Outlet Temperature in Long Heat Exchanger Tubes

This study investigates the effects of fouling thickness, air velocity, and ambient temperature on the outlet temperature of a heat exchanger. Based on the variation ranges of the working condition parameters provided in Table 8 and the orthogonal experimental design shown in Table 9, a total of 16 numerical simulations with different parameter combinations were carried out. Following the methodology described in Section 4.1, the thermal resistance coefficient for each case was obtained, and the methane outlet temperature was subsequently calculated using HTRI for a heat exchanger length of 15 m. The configuration of the HTRI model is illustrated in Figure 13, which consists of three tube rows: the odd-numbered rows each contain 15 heat transfer tubes, while the even-numbered rows each contain 16 tubes. The mean value of outlet temperatures across 46 tubes for each case is provided in Table 9.

Table 8.

The value range of working condition parameters.

Table 9.

Orthogonal experimental design.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of the heat exchanger tube bundle configuration in HTRI.

Range analysis was applied to assess the effects of dust thickness, ambient temperature, and air velocity on the performance of a finned-tube heat exchanger bundle. The mean values of the performance responses and the corresponding range for each parameter at different levels were calculated to identify the most significant factors influencing heat transfer performance and to determine their optimal levels. As summarized in Table 10, K denotes the sum of experimental results for each factor at each level, Kavg represents the average value of K, and R indicates the range, defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum Kavg values for each factor. The results demonstrate that ambient temperature is the dominant factor affecting the methane outlet temperature. The highest methane outlet temperature is achieved under the condition of a dust thickness of 0.24 mm, an ambient temperature of 40 °C, and an air velocity of 1 m/s, indicating the poorest heat transfer efficiency under this operational scenario.

Table 10.

Results of range analysis for the average outlet temperature.

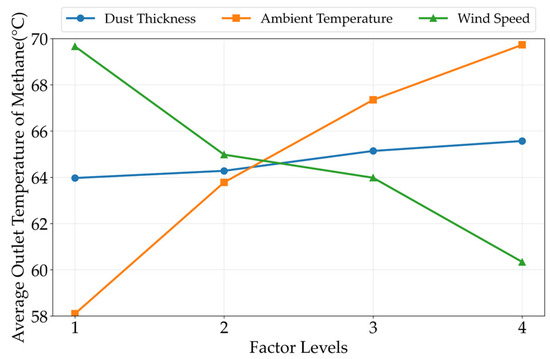

To evaluate the effects of different factor levels on heat transfer performance, the average values of the experimental responses for each factor at each level were calculated, as shown in Figure 14. The analysis reveals that the average methane outlet temperature increases with rising dust thickness and ambient temperature, but decreases with increasing air velocity. This trend can be attributed to the following mechanisms: an increase in dust layer thickness raises the thermal resistance at the heat transfer surface, thereby impeding the overall heat transfer process; higher ambient temperature reduces the mean temperature difference between the cold and hot fluids, resulting in an elevated outlet temperature; whereas increased air velocity enhances the intensity of convective heat transfer, accelerating the heat dissipation from the hot-side fluid to the cold side, thus leading to a reduction in the outlet temperature.

Figure 14.

Average outlet temperature values across different factor levels.

4.3. Outlet Temperature Prediction of Finned-Tube Bundles with Surrogate Modeling

The calculation of the outlet temperature for the fouled heat exchanger tube bundle, following the methodology presented in Section 4.1, requires initial identification of the fouling resistance coefficient via FE simulation, subsequently enabling the determination of the outlet temperature using HTRI software. To improve the efficiency and convenience of predicting the outlet temperature under varying operating conditions, a surrogate modeling approach is introduced in this study to establish a prediction model capable of estimating tube bundle outlet temperatures across diverse operational scenarios.

The dataset was divided into a training set and a testing set at a ratio of 8:2. The training set consisted of 16 groups of orthogonal experimental data from Section 4.2, which were used to train the random forest model and establish the nonlinear mapping relationships among inlet air velocity, dust thickness, and ambient temperature as input variables, and the corresponding methane outlet temperature as the output variable. The testing set comprised 4 groups of numerical simulation data from Section 3.5, as shown in Table 11, and was employed to independently verify the predictive accuracy and generalization capability of the model. The root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and coefficient of determination (R2) described in Equation (15) are introduced to evaluate the prediction model’s performance.

where n is the sample size, is the true value and is the predicted value.

Table 11.

Detailed operating conditions of the testing dataset.

To address the small-sample modeling problem involved in this study, the random forest (RF) regression model [33] was initially employed. As a Bagging-based ensemble learning method, RF constructs multiple regression decision trees through bootstrap sampling. During node splitting, it selects the optimal split point only from a randomly chosen subset of features. The final prediction is obtained by averaging the outputs of all individual trees, thereby reducing variance and enhancing generalization performance [34]. This method requires no feature scaling, captures nonlinear relationships effectively, exhibits robustness to outliers and missing data, and provides feature importance evaluation. Key hyperparameters include the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum depth (max_depth), minimum samples for node splitting, minimum samples at leaf nodes, and the maximum number of features for each tree (max_features). The prediction process of the model can be expressed as:

where ŷ is the predicted value, B is the number of decision trees, and fb(x) denotes the prediction of the bth tree for input x. For comparative purposes, AdaBoost regression [35] and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) regression [36] models were also trained. The hyperparameters of the three methods are summarized in Table 12.

Table 12.

Model parameters of three surrogate models.

The testing dataset was input into the three trained prediction models, and the RMSE, MAPE, and R2 were calculated as shown in Table 13. All three prediction models exhibit well-fitting performance on the testing dataset, with R2 values exceeding 0.9 and MAPE values below 0.4%. Among them, the RF regression model significantly outperforms the other two models, achieving an RMSE of 0.0719 and a MAPE of 0.0942%, which are considerably lower than those of the AdaBoost and KNN regression models. Moreover, its R2 reaches 0.9951, demonstrating a clear advantage over the other methods. In conclusion, the RF model performs best in terms of error control and goodness-of-fit.

Table 13.

Evaluation metrics of three prediction models on testing data.

Furthermore, Table 14 presents the predicted average outlet temperatures of four testing samples using the RF model. It can be observed that the predicted values show good agreement with the actual values obtained from HTRI calculations. The maximum relative error, observed in the second testing sample, is only 0.1869%, corresponding to an absolute deviation of 0.12 °C. These results further confirm the feasibility of employing the RF model in this study.

Table 14.

Comparison between actual data and predicted data generated by the RF model.

5. Conclusions

During long-term operation of air-cooled heat exchange equipment, fouling tends to accumulate on heat transfer surfaces, significantly impairing thermal and hydrodynamic performance. Therefore, investigating heat transfer characteristics under fouling conditions is crucial for improving energy efficiency and ensuring operational reliability. This study focuses on the performance degradation of spiral finned-tube heat exchangers caused by fouling deposition and proposes an integrated prediction methodology combining discrete element method, finite element analysis, and surrogate modeling. The deposition behavior of dust particles within the tube bundle is first simulated using the DEM to characterize the spatial distribution of fouling and determine equivalent thickness values in different orientations. Subsequently, FE simulation is employed to analyze the influence of ash layer thickness on the thermal-hydraulic performance of the heat exchanger. To address the high computational cost associated with finite element methods and their limited applicability to large-scale tube assemblies, the fouling resistance obtained from FE simulations is incorporated as an input parameter into HTRI software for efficient computation of the outlet temperatures in long-distance heat exchanger configurations. Furthermore, a surrogate model is developed with fouling thickness, ambient temperature, and inlet air velocity as input variables, and the average outlet temperature of the fluid as the response variable. The proposed approach enables rapid prediction of heat exchanger performance under multiple operating conditions, thereby enhancing computational efficiency and meeting the demands of engineering analysis.

A case study was conducted on the spiral finned-tube heat exchanger assembly at the Chongqing Xiangguosi Underground Gas Storage Co., Ltd. By integrating DEM and FE simulation, it is found that increasing dust deposition thickness leads to elevated flow resistance, resulting in a rise in the pressure difference between the inlet and outlet as well as an increase in the resistance factor. In contrast, the Nusselt number and heat transfer factor decrease with greater dust thickness due to the thermal insulation effect of fouling, which reduces heat exchange efficiency. After validating the consistency between the FE simulation and HTRI software results, a 16-group orthogonal experimental design was constructed based on fouling thickness, ambient temperature, and inlet air velocity. The combined use of FE simulation and HTRI software enabled the calculation of methane temperatures at the outlet of a 15-m-long tube assembly. On the basis, an RF prediction model was trained, which achieved a MAPE of 0.0942% and a maximum error of 0.1869% on the testing dataset, demonstrating high prediction accuracy and reliability. This study not only provides an effective tool for fouling state assessment and operational optimization of heat exchangers at the Chongqing Xiangguosi Underground Gas Storage Co., Ltd., but also offers valuable insights into performance prediction and maintenance strategy formulation for heat exchange equipment in similar industrial contexts.

Beyond the specific case of spiral finned-tube heat exchangers, the proposed DEM–FEA–HTRI–RF hybrid framework exhibits strong adaptability to other types of heat exchange equipment, such as plate-fin, shell-and-tube, and air–gas heat exchangers. By adjusting the geometric parameters and boundary conditions in the DEM and FEA modules, the same methodology can be extended to model different fouling behaviors and evaluate their thermal–hydraulic impacts under diverse industrial conditions. This flexibility highlights the framework’s potential as a universal tool for fouling analysis, performance prediction, and optimization across a wide range of heat exchanger configurations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y., T.J. and D.T.; methodology, Y.Y. and C.D.; software, H.T. and J.M.; validation, J.L., Y.Y. and D.T.; formal analysis, T.J.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, J.L.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and H.T.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and C.D.; visualization, Y.Y. and H.T.; supervision, J.M.; project administration, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, T.J., J.M. and C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Southwest Oil and Gas Field Innovation Fund Project, grant number 2024D7-19, and the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, grant number KJZD-K202300611 and KJQN202300640.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Berce, J.; Zupančič, M.; Može, M.; Golobič, I. A Review of Crystallization Fouling in Heat Exchangers. Processes 2021, 9, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, F.; Zhuang, D.; Ding, G.; Ju, P.; Tang, J. Influence of Wet-Particle Deposition on Air-Side Heat Transfer and Pressure Drop of Fin-and-Tube Heat Exchangers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 124, 1230–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, C.; Suárez, E.; Concheiro, M.; Porteiro, J. Experimental Study of Soot Particle Fouling on Ribbed Plates: Applicability of the Critical Local Wall Shear Stress Criterion. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2013, 44, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M. Impact of Airside Fouling on Microchannel Heat Exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 128, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhagen, R.; Müller-Steinhagen, H.; Maani, K. Problems and costs due to heat exchanger fouling in New Zealand industries. Heat Transf. Eng. 1993, 14, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, S.J.; Hewitt, G.F.; Müller-Steinhagen, H. Fouling during the use of fresh water as coolant the development of a user guide. Heat Transf. Eng. 2009, 30, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyama, E.M.; Pugh, S.J.; Zettler, H.U. Economic and environmental implications of fouling in crude preheat trains. Heat Transf. Eng. 2024, 45, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, W.; Yun, R.; Heo, J. Experimental study of the seawater fouling on a plate-frame heat exchanger for utilization of waste heat from powerplant. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 5025–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, I.H.; Groll, E.A.; König, H. Experimental Analysis of the Effects of Particulate Fouling on Heat Exchanger Heat Transfer and Air-Side Pressure Drop for a Hybrid Dry Cooler. Heat Transf. Eng. 2011, 32, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebele-Alawa, B.; Ohia, I.O. Influence of Fouling on Heat Exchanger Effectiveness in a Polyethylene Plant. Energy Power 2014, 4, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, F.; Li, D. Experimental Study of Fouling Performance of Air Conditioning System with Microchannel Heat Exchanger; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Välikangas, T.; Hærvig, J.; Kuuluvainen, H.; Dal Maso, M.; Peltonen, P.; Vuorinen, V. Deposition of Dry Particles on a Fin-and-Tube Heat Exchanger by a Coupled Soft-Sphere DEM and CFD. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 149, 119046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Peng, W.; Shi, L. Fluid-Structure Coupling for Particle Deposition-Resuspension Predictions in Tube Bundle Heat Exchangers Based on Dynamic Mesh Method. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 297, 120313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Peng, W. Numerical Study of Thermal-Hydraulic and Dust-Deposition of Tube Bundles in an Intermediate Heat Exchanger. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 27187–27198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Ye, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Tian, W.; Qiu, S.; Su, G. A Machine Learning and CFD Based Approach for Fouling Rapid Prediction in Shell-and-Tube Heat Exchanger. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2025, 432, 113759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Zhang, D.; Yan, Q.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Jiang, M. Application of Machine Learning Algorithms in Real-Time Fouling Monitoring of Plate Heat Exchangers. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 164, 108809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelczyk, N.; Gomez-Rosero, S.; Capretz, M.A. Predictive Maintenance Using Fouling Detection on Heat Exchangers. In Proceedings of the 2024 34th International Conference on Collaborative Advances in Software and COmputiNg (CASCON), Toronto, ON, Canada, 11–13 November 2024; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.L.; Kendall, K.; Roberts, A. Surface Energy and the Contact of Elastic Solids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1971, 324, 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, O.; DeGennaro, A.; Rame, E.; Wilkinson, A. DEM Simulation of a Schulze Ring Shear Tester. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Golden, CO, USA, 18 June 2009; American Institute of Physics: Melville, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 1145, pp. 409–412. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, J.; Carey, V.P. Fouling of HVAC Fin and Tube Heat Exchangers; Fouling of HVAC Fin and Tube Heat Exchangers: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Yue, S.; Lu, L.; Li, J. Study on Dust Deposition Mechanics on Solar Mirrors in a Solar Power Plant. Energies 2019, 12, 4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, D.; Woschny, N.; Schmidt, E.; Kruggel-Emden, H. Modelling of the Detachment of Adhesive Dust Particles during Bulk Solid Particle Impact to Enhance Dust Detachment Functions. Powder Technol. 2022, 400, 117238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, P.; Jiang, J.; Luo, X. Thermal Performance of Elliptical Fin-and-Tube Heat Exchangers with Vortex Generator under Various Inclination Angles. J. Therm. Sci. 2021, 30, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, D. Parametric Investigation and Correlation Development for Thermal-Hydraulic Characteristics of Honeycomb 4H-Type Finned Tube Heat Exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 199, 117542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välikangas, T.; Folkersma, M.; Dal Maso, M.; Keskitalo, T.; Peltonen, P.; Vuorinen, V. Parametric CFD Study for Finding the Optimal Tube Arrangement of a Fin-and-Tube Heat Exchanger with Plain Fins in a Marine Environment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 200, 117642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Xin, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J.; Fu, T. Airside Thermal-Hydraulic and Fouling Performances of Economizers with Integrally-Molded Spiral Finned Tubes for Residual Heat Recovery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 211, 118365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X. Impact of Changing Inlet Modes in Ski Face Masks on Adolescent Skiing: A Finite Element Analysis Based on Head Models. Modelling 2024, 5, 936–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.; Blum, J.; Skorov, Y.V.; Trieloff, M. Thermal conductivity measurements of porous dust aggregates: I. Technique, model and first results. Icarus 2011, 214, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kays, W.M.; London, A.L. Compact Heat Exchangers; Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sakhti, S.; Karunakaran, S.; Esakkimuthu, J.; Mariya, A.; Mohamed, N.; Vinoth, S. Design of Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Using HTRI Suite Software and Validation of Results Using Manual Calculation. Int. J. Petrochem. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Heat Transfer Research, Inc. HTRI Xchanger Suite [Computer Software]; Heat Transfer Research, Inc.: Navasota, TX, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.htri.net/htri-xchanger-suite (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Guðmundsson, O. Detection of Fouling in Heat Exchangers Using Model Comparison. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Iacob, I.E. Manuscripts Character Recognition Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Modelling 2023, 4, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A Decision-Theoretic Generalization of on-Line Learning and an Application to Boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.J. Consistent Nonparametric Regression. Ann. Stat. 1977, 5, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).