Abstract

In this study, the influence of nanochitosan and kenaf fibers on the tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength of polylactic acid (PLA)/natural rubber (Standard Malaysian Rubber, grade 20—SMR20) biocomposites was investigated experimentally using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). The independent variables included the weight percentage of nanochitosan (2, 4, and 6 wt%), kenaf fibers (5, 10, and 15 wt%), and SMR20 natural rubber (10, 20, and 30 wt%). Composite samples were prepared by melt mixing in an internal mixer and subsequently fabricated into test samples using hot compression molding in accordance with relevant standards. Tensile tests were conducted to evaluate tensile strength and elastic modulus, while Charpy impact tests were performed to assess impact strength. The results revealed that increasing nanochitosan content up to 4 wt% enhanced tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength by 39%, 22%, and 27%, respectively; however, further addition (6 wt%) led to a decline in these properties due to nanoparticle agglomeration. Increasing kenaf fiber content to 15 wt% improved tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength by 44%, 26%, and 37%, respectively, demonstrating their effective reinforcing role. The incorporation of SMR20 natural rubber significantly increased impact strength by 59% (at 30 wt%), while causing a reduction of 17% in tensile strength and 20% in elastic modulus, consistent with its elastomeric nature. Furthermore, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) was employed to examine the dispersion of nanochitosan and kenaf fibers within the PLA/SMR20 matrix, providing insights into the interfacial adhesion and failure mechanisms. The findings highlight the potential of optimizing natural filler and rubber content to tailor the mechanical performance of sustainable PLA-based biocomposites.

1. Introduction

The environmental persistence of conventional plastics has driven significant interest in bio-based composite alternatives for engineering applications. Among these, polylactic acid (PLA) stands out due to its commercial availability, compostability, and adequate mechanical properties [1]. However, its inherent brittleness, low thermal stability, and relatively high cost limit its wider adoption [2]. A well-established strategy to overcome these limitations is to blend PLA with natural rubber for toughening and reinforce it with natural fibers or nanofillers for enhanced stiffness and strength [3,4]. This approach aligns with the growing demand for sustainable materials in weight-sensitive industries. For instance, PLA-based composites reinforced with natural fibers like flax or hemp are being explored for non-structural automotive interior panels [5], while the use of PLA compounded with nanoclays or cellulose nanofibers has been investigated for cabin interiors in aerospace [6]. These sectors value not only the reduced environmental footprint but also the specific mechanical properties and potential for weight reduction. Key candidates for creating such hybrid biocomposites include Standard Malaysian Rubber (SMR20) as an impact modifier, kenaf fibers as a macro-scale reinforcement, and nanochitosan as a bio-based nanofiller. SMR20, a commercially prevalent grade of natural rubber, can significantly improve the toughness of PLA [7]. Kenaf fibers offer high specific stiffness and low density, making them effective reinforcements [8]. Nanochitosan, derived from chitin, provides a nanoscale reinforcing effect and can impart additional functionalities due to its reactive surface groups [9]. However, integrating these components into a high-performance PLA composite presents specific scientific and practical challenges that form the rationale for this study. The primary challenge is the inherent incompatibility between the non-polar rubber domains and the polar PLA matrix, which often leads to poor interfacial adhesion and suboptimal stress transfer, ultimately limiting the toughness improvement [10]. While previous studies, such as the work by Alias et al. [11], have successfully addressed this by using chemically modified rubbers like epoxidized natural rubber (ENR) along with synthetic co-compatibilizers, there is a need to explore the performance of more commercially standard, non-reactive rubber grades like SMR20. Furthermore, the hydrophilic nature of kenaf fibers can lead to moisture absorption and weak interfacial bonding with hydrophobic PLA, while their tendency to agglomerate during processing can hinder property enhancement [12]. Similarly, the effectiveness of nanochitosan is critically dependent on achieving a uniform dispersion within the polymer melt; otherwise, nanoparticle agglomeration creates defect sites that degrade mechanical properties [13]. Consequently, while the individual potential of these additives is recognized, the complex synergistic or antagonistic interactions within a hybrid four-component system—PLA, SMR20, kenaf, and nanochitosan—are not well understood. Most existing research focuses on ternary blends or employs specific chemical compatibilizers [11]. There is a lack of a comprehensive, quantitative model that can predict and optimize the mechanical performance of this specific system by simultaneously accounting for the individual and interactive effects of all three additives.

Ruz-Cruz et al. [14] investigated the thermal and mechanical properties of PLA-based biocomposites reinforced with cellulose fibers at multiple length scales. Their study systematically examined the effects of incorporating both cellulose nanoparticles (CNPs) and macroscale cellulose fibers on key properties, including tensile strength, elastic modulus, strain at failure, glass transition temperature (Tg), and thermal stability. The results demonstrated that cellulose nanoparticles—owing to their small size and high specific surface area—significantly enhanced tensile strength and elastic modulus. In contrast, the addition of macroscale cellulose fibers improved ductility, as evidenced by increased strain at failure and greater flexibility. The authors also highlighted the critical role of compatibilizers in promoting interfacial adhesion between the hydrophobic PLA matrix and hydrophilic cellulose phases, noting that their absence can compromise mechanical performance.

Pongputthipat et al. [15] investigated the synergistic effects of three primary components—polylactic acid (PLA), natural rubber (NR), and rice straw fibers—on the properties of biocomposite films. They reported that incorporating 20 wt% NR into the PLA matrix enhanced toughness by 60% and flexibility by 45%, while retaining 85% of the original tensile strength. A key innovation of their study was the concurrent use of rice straw fibers as a natural reinforcing agent, which significantly improved mechanical performance. Specifically, the addition of 10 wt% rice straw fibers increased the tensile modulus by 40% and impact strength by 35%, attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonds between hydroxy groups on the fiber surface and the PLA/NR blend matrix. Microscopic analyses further confirmed that the coupling agent promoted phase homogeneity by reducing particle size and ensuring a more uniform dispersion. From a practical standpoint, the developed composites exhibited a 25% reduction in water vapor permeability and achieved 70% biodegradation within eight weeks under composting conditions, highlighting their potential as sustainable packaging materials.

Nanochitosan, a natural biopolymer derived from chitin through controlled deacetylation and hydrolysis, has garnered significant interest in advanced materials research owing to its nanoscale dimensions, biocompatibility, and distinctive functional properties. Its surface is rich in reactive amine and hydroxyl groups, which facilitate strong interfacial interactions with polymer matrices and other nanofillers. In polymer nanocomposites, nanochitosan serves not only as a mechanical reinforcement enhancing tensile strength, elastic modulus, and thermal stability through uniform dispersion but also imparts valuable functionalities such as inherent antibacterial activity. These attributes make it particularly promising for sustainable applications in food packaging and biomedical fields, all while preserving the biodegradability of the composite system [16].

Rodrigues et al. [17] investigated the mechanical, thermal, and antimicrobial properties of chitosan-based nanocomposites. Their findings revealed that the incorporation of nano-chitosan into the matrix enhanced the tensile strength by 35% and increased Young’s modulus by 25%, attributed to the formation of a hydrogen-bonding network between the functional groups of chitosan and the polymer chains. Thermal analysis demonstrated improved thermal stability, with a 40 °C increase in degradation onset temperature compared to neat (control) samples. Furthermore, SEM micrographs confirmed the homogeneous dispersion of chitosan nanoparticles within the matrix, which reduced pore size to approximately 70 nm and contributed to enhanced barrier properties.

Ilyas et al. [18] investigated chitosan-based and chemically modified chitosan nanocomposites reinforced with natural fibers such as kenaf, bamboo, and coconut. Their findings demonstrated that the integration of these natural fibers into the chitosan matrix yields advanced hybrid materials with significantly enhanced performance. Specifically, the resulting nanocomposites exhibited a 30–40% increase in mechanical strength and a 35–50% improvement in thermal stability compared to neat chitosan. The study further emphasized the broad applicability of these biocomposites in emerging fields, including smart food packaging, tissue engineering, water purification, and energy storage. Notably, the authors highlighted their exceptional potential for developing active, antimicrobial, and fully biodegradable packaging solutions, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional plastics and contributing to the mitigation of plastic pollution.

Kenaf fibers, among the most prominent natural cellulosic fibers, have gained significant attention in the development of green composites owing to their exceptional combination of high tensile strength, low density, and full biodegradability. Derived from the bast of the Cannabis sativa plant, these fibers exhibit a microfibrillar structure composed of 70–80% cellulose, along with hemicellulose and lignin, which collectively contribute to their favorable mechanical performance and thermal stability [19].

In polymer nanocomposites, kenaf fibers serve as effective natural reinforcements, enhancing both tensile strength and impact resistance by forming a robust percolating network within the polymer matrix. A key advantage of kenaf fibers is their potential for strong interfacial adhesion with polymers like PLA after appropriate surface treatment. In this study, alkaline (NaOH) treatment was employed to remove surface impurities and enhance the fiber’s compatibility with the hydrophobic PLA matrix, thereby facilitating more efficient stress transfer [20,21]. Asyraf et al. [22] investigated the dynamic–mechanical behavior of biocomposites reinforced with kenaf cellulose fibers subjected to various chemical treatments. Their findings demonstrated that chemical modification of the kenaf fibers significantly enhances key dynamic–mechanical properties, namely, the storage modulus (increased by up to 45%), the loss modulus (improved by up to 30%), and the glass transition temperature (shifted by approximately 10–15 °C). Additionally, Kumar et al. [23] investigated the mechanical performance, modification techniques, and key challenges associated with kenaf fiber–reinforced biocomposites. Their findings demonstrated that, through optimization of fabrication parameters, these biocomposites can attain tensile strengths ranging from 58 to 110 MPa and elastic moduli between 8 and 12 GPa, comparable to those of conventional synthetic composites and positioning them as viable sustainable alternatives.

The main objective of this study is to employ Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with a Box–Behnken design to systematically model, analyze, and optimize the tensile and impact properties of PLA/SMR20 biocomposites reinforced with kenaf fibers and nanochitosan. This approach allows us to quantitatively determine the optimal balance between these components and identify the significant interactions governing the mechanical performance, providing actionable design guidelines that are currently absent in the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In this study, a hybrid biocomposite was developed using four primary components: polylactic acid (PLA) as the matrix, SMR20 natural rubber as a flexibility-enhancing modifier, nanochitosan as a nanoscale reinforcing agent, and kenaf fibers as macroscale reinforcement. The raw materials were carefully selected to achieve an optimal balance among mechanical performance, production cost, and environmental compatibility. PLA granule, 4042D grade used in this study was supplied by NatureWorks LLC, Tokyo, Japan. The material exhibits a Young’s modulus of approximately 3.5 GPa, a tensile strength of around 53 MPa, and an elongation at break of about 3%. Additionally, it has a glass transition temperature (Tg) of approximately 58 °C, which renders it suitable for a wide range of applications. Natural rubber (SMR20) was supplied by the Malaysian Rubber Board, exhibiting a polyisoprene content exceeding 92% and impurity levels below 0.8%. Nano-chitosan, with a deacetylation degree of 85–90% and an average particle size of 50–100 nm, was procured from Primex (Siglufjordur, Iceland). Kenaf fibers were sourced from Kenaf (The Netherlands), with a length of 5–10 mm and a diameter ranging from 15 to 25 μm.

2.2. Preparation of Samples

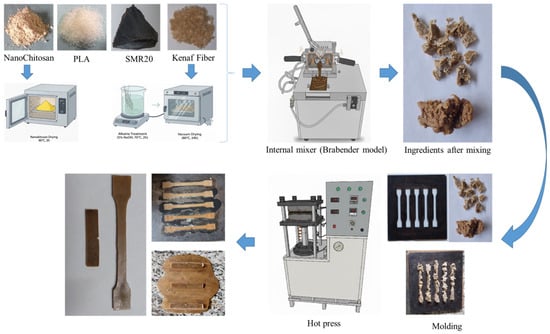

To prepare the bio-based composite samples, polylactic acid (PLA), natural rubber (SMR20), nanochitosan, and kenaf fibers were used as raw materials. All materials were processed immediately after preparation to maintain their purity and ensure consistent quality. Prior to compounding, PLA pellets were dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C for at least 6 h to minimize hydrolytic degradation during processing. Nanochitosan was similarly dried in a convection oven at 90 °C for 2 h to eliminate residual moisture. This drying step was essential to prevent the formation of voids or air bubbles within the PLA/SMR20 matrix during processing and to enhance the overall homogeneity and mechanical integrity of the final nanocomposite. Kenaf fibers were initially treated with a 5 wt% NaOH (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) solution at 70 °C for 2 h to remove surface impurities and non-cellulosic components. Following alkaline treatment, the fibers were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water until a neutral pH was achieved. They were then dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C for 24 h to ensure complete moisture removal. Subsequently, the biocomposite samples were prepared via the melt blending method. For this purpose, an internal mixer (Brabender W 50 EHT, Brabender GmbH and Co. KG, Duisburg, Germany) available at the Iran Polymer and Petrochemical Institute was employed, operating at a rotor speed of 60 rpm and a temperature of 180 °C. Initially, polylactic acid (PLA) was melt-blended as the base polymer in an internal mixer. Subsequently, natural rubber (SMR20) was incorporated into the PLA matrix at three different weight loadings 10, 20, and 30 wt% to formulate the hybrid PLA matrix. In the following stage, nanochitosan was introduced at concentrations of 2, 4, and 6 wt%, while kenaf fibers were added at 5, 10, and 20 wt%, respectively, to develop the final biocomposite formulations. The materials were accurately weighed and gradually incorporated into the polymer mixture to ensure homogeneous dispersion within the matrix. All samples were mixed for a consistent duration of 10 min. The samples were fabricated using a hot press (Carver Auto Series, Carver, Inc., Wabash, USA) at 180 °C and 2.5 MPa pressure in custom molds, in accordance with ISO 527-1 (tensile testing) and ISO 179 (impact testing) standards. The sample preparation procedure for the nanocomposite is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process steps for preparing tensile and impact test specimens.

To ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the results, five standard samples were fabricated for each material composition and tested for each mechanical property. All samples were prepared under identical processing conditions to enable a precise and reliable assessment of the effects of the varying parameters on the mechanical performance of the composites.

2.3. Design of Experiments (DOE)

To efficiently model, analyze, and optimize the mechanical properties of the biocomposites as a function of the three key formulation variables, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with a Box–Behnken Design (BBD) was employed. RSM has been successfully employed to model and optimize various properties in polymer composites, including wear performance [24,25]. This approach allows for the development of predictive models using a minimal number of experimental runs while capturing potential interaction effects between factors. The independent variables and their investigated levels were the weight percentages of: nanochitosan (2, 4, 6 wt%), kenaf fibers (5, 10, 15 wt%), and SMR20 natural rubber (10, 20, 30 wt%), as defined in Table 1. For a system with three factors, a standard BBD generated an experimental matrix of 15 runs, including three center points for estimating experimental error. The complete design, listing the exact composition for each run (including the calculated PLA content to sum to 100 wt%), is presented in Table 2. The tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength were defined as the response variables. A quadratic polynomial model (Equation (1)) was fitted to the experimental data for each response to establish the quantitative relationship between the independent variables and the mechanical properties.

where y is the predicted response, β0 is the constant coefficient, βi, βᵢii, and βi are the coefficients for linear, quadratic, and interaction terms, respectively, xi and x are the coded independent variables, and ε is the random error.

Table 1.

Levels of the variables in Box–Behnken experimental design.

Table 2.

The Box–Behnken experimental design.

Polylactic acid (PLA) served as the base matrix in all compositions. The PLA content for each experimental run was determined as the balance to achieve a total of 100 wt%, calculated using the following formula:

PLA (wt%) = 100 − (Nanochitosan (wt%) + Kenaf Fibers (wt%) + SMR20 (wt%))

Subsequently, based on the experimental design generated using Design-Expert® software (version 13), 15 distinct formulation combinations were established for the tested samples, as summarized in Table 2.

2.4. Characterization

Tensile properties were determined using a universal testing machine (Zwick Roell Z100, Ulm, Germany) according to ISO 527-1. Tests were performed at a crosshead speed of 5 mm/min and at a controlled room temperature of 26 ± 1 °C until specimen failure. Tensile strength and elastic modulus were derived from the stress–strain curves. Charpy impact strength was measured using a pendulum impact tester following ISO 179. Unnotched specimens with dimensions of 80 × 10 × 4 mm3 were tested under the same ambient conditions (26 ± 1 °C). A minimum of five specimens were tested for each composite formulation to ensure statistical reliability. The fracture surfaces of selected impact-tested samples were examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, model VEGA, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic). Prior to imaging, the samples were sputter-coated with a thin conductive layer of gold using a sputter coater (Quorum Q150R S, Quorum Technologies, East Susse, UK). The coating process was carried out for 60 s at a current of 20–25 mA under an argon atmosphere, resulting in an estimated coating thickness of approximately 10 nm. FESEM observations were performed under high vacuum conditions at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. A working distance of 10–15 mm was maintained, and images were captured using the secondary electron (SE) detector to reveal topographical contrast. The spot size was adjusted for optimal resolution during imaging.

3. Results and Discussion

In this study, the combined incorporation of SMR20, kenaf fibers, and nanochitosan into a polylactic acid (PLA) matrix was investigated. Following tensile and impact testing, the average values of tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength for each composite formulation are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Tensile and impact test results.

3.1. Morphological Analysis of Fracture Surfaces via FESEM

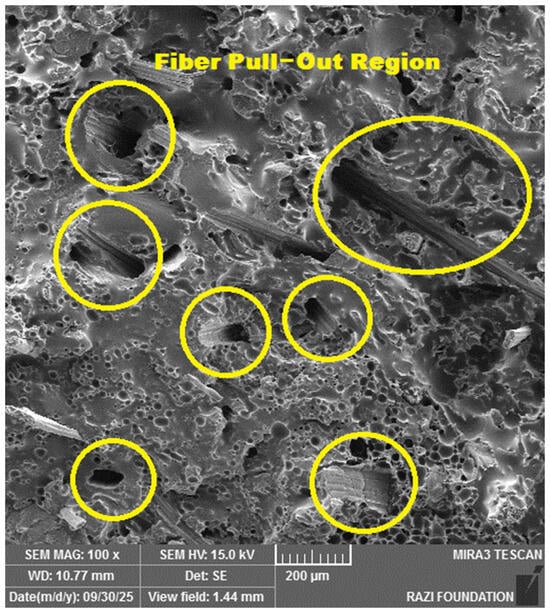

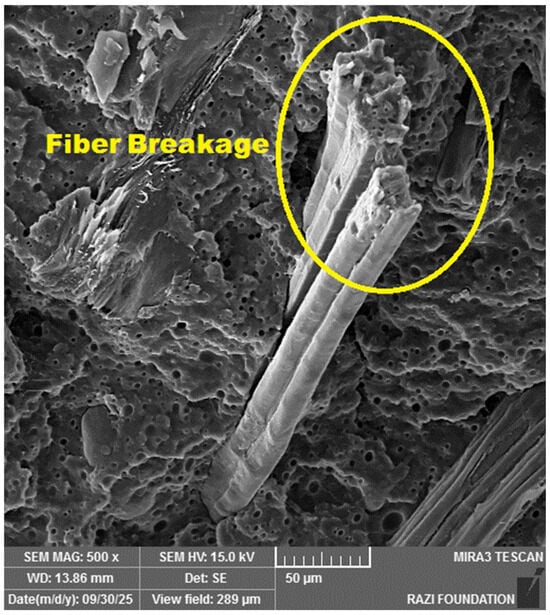

To gain deeper insight into the mechanical behavior of the fabricated biocomposites and to assess the interfacial adhesion between their constituent phases, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) was employed to examine the fracture surfaces of impact-tested samples fractured in liquid nitrogen. Cryogenic fracture (achieved via liquid nitrogen immersion) suppresses polymer chain mobility, resulting in a brittle fracture mode that yields a clean and well-defined surface. This facilitates clear visualization of key microstructural features, including reinforcement dispersion, fiber matrix interfacial bonding, fracture morphology, and failure mechanisms such as debonding or pull-out. FESEM micrographs of the various formulations are presented in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, and their correlation with the measured mechanical properties is analyzed in the following section. To directly visualize the effect of nanochitosan content on the fiber-matrix interface, FESEM analysis was conducted on representative samples along this compositional gradient:

Figure 2.

Fracture surface morphology of Sample 1 (PLA-based biocomposite containing 2 wt% nanochitosan, 5 wt% kenaf fiber, and 20 wt% SMR20) after impact testing at liquid nitrogen temperature, as observed by FESEM.

Figure 3.

FESEM micrograph of the fracture surface of Sample 13 (4 wt% nanochitosan, 10 wt% kenaf fiber, 20 wt% SMR20).

Figure 4.

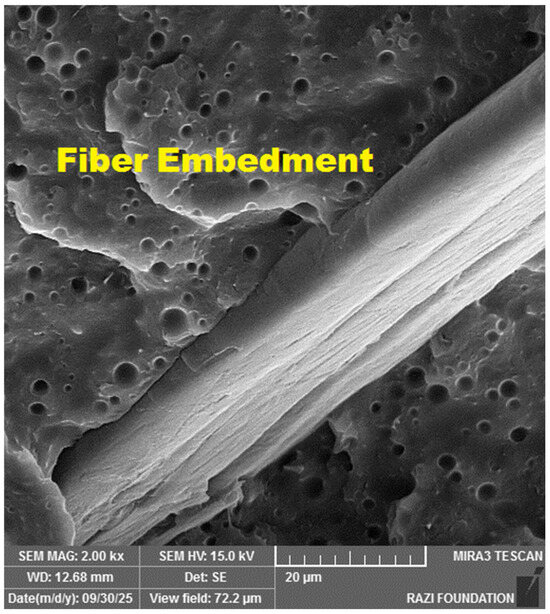

FESEM micrograph of the fracture surface of Sample 12 (4 wt% nanochitosan, 15 wt% kenaf fiber, 30 wt% SMR20).

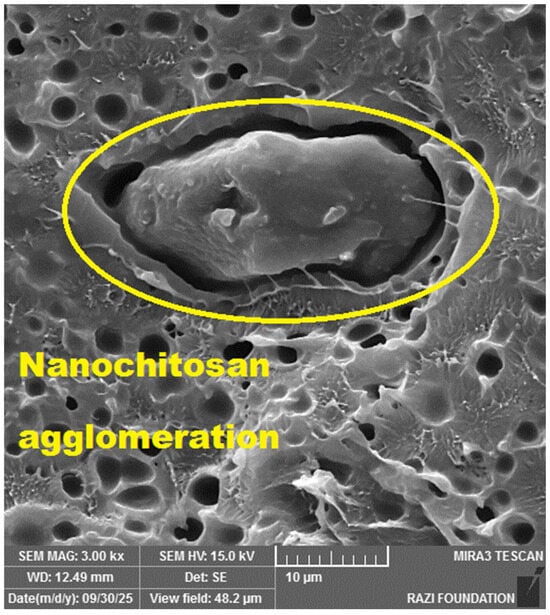

Figure 5.

FESEM micrograph revealing macro-scale agglomeration in Sample 8 (6 wt% nanochitosan, 10 wt% kenaf, 30 wt% SMR20), The yellow circle highlights a ~20 µm agglomerate of nanochitosan particles.

- -

- Figure 2 shows the fracture surface of a composite with a low nanochitosan content (2 wt%), where insufficient interfacial modification leads to prominent fiber pull-out and debonding.

- -

- -

- Figure 5 illustrates the microstructure at a high nanochitosan content (6 wt%), where particle agglomeration is observed, creating defects that can compromise mechanical performance.

The morphological analysis provides a clear rationale for the complex, non-linear trends in the mechanical properties established by the RSM models. The system’s inability to maintain a perfectly uniform morphology at all compositions—evident from interfacial gaps and filler agglomeration—necessarily leads to property variations that are non-monotonic and dependent on the balance between reinforcement and defect formation.

Figure 2 presents the FESEM micrograph of the cryogenically fractured surface of Sample 1, composed of 2 wt% nanochitosan, 5 wt% kenaf fibers, and 20 wt% SMR20 in a PLA matrix. The sample was impact-tested at liquid nitrogen temperature to induce brittle fracture, thereby producing a sharp and well-defined surface suitable for detailed morphological analysis. The micrograph reveals clear evidence of weak interfacial adhesion between the kenaf fibers and the PLA/SMR20 matrix. Notably, numerous fibers are fully pulled out of the matrix, leaving behind distinct longitudinal voids or debonded channels. This pull-out behavior is characteristic of poor fiber matrix bonding, wherein interfacial debonding occurs preferentially over fiber fracture under applied stress. Consequently, the fibers fail to effectively transfer load or dissipate energy, leading to reduced impact resistance, a finding consistent with the relatively low mechanical performance observed for this formulation. A similar observation has been reported by Nouri et al. [26], which shows a good agreement.

The limited amount of nanochitosan (2 wt%) in this formulation is identified as a key contributor to the poor interfacial adhesion observed between the kenaf fibers and the PLA/SMR20 matrix. Nanochitosan possesses abundant active functional groups, particularly amine (–NH2) and hydroxyl (–OH), that can act as compatibilizing agents by forming hydrogen bonds or polar interactions with both the hydroxyl-rich surface of kenaf fibers and the polar ester groups in the PLA/SMR20 matrix. However, at such a low concentration (2 wt%), nanochitosan particles are insufficiently distributed at the fiber–matrix interface and fail to form a continuous, cohesive interphase layer. Consequently, the interfacial region remains weak and prone to debonding under applied stress, leading to premature fiber pull-out and reduced load transfer efficiency.

Figure 3 presents an FESEM micrograph of the fracture surface of Sample 13 (4 wt% nanochitosan, 10 wt% kenaf, 20 wt% SMR20) following impact testing. In comparison to Sample 1 (Figure 2), the fracture morphology suggests enhanced interfacial compatibility. The micrograph shows a notable reduction in clean fiber pull-out cavities. Instead, fibers appear well-embedded within the matrix, and some exhibit resin residues or fractures within the fiber body itself. These features are commonly associated with improved interfacial stress transfer [27]. This improved interfacial compatibility is primarily attributed to the increase in nanochitosan content from 2 to 4 wt%. Nanochitosan contains abundant functional groups (–NH2, –OH) that can form hydrogen bonds and polar interactions with both kenaf fibers and PLA chains. At 4 wt%, nanochitosan particles are adequately dispersed, potentially forming an effective compatibilizing interphase that promotes stronger fiber-matrix interaction, as inferred from the mechanical property enhancement.

Figure 4 presents the FESEM micrograph of Sample 12, formulated with 4 wt% nanochitosan, 15 wt% kenaf fibers, and 30 wt% SMR20. The image reveals a significant improvement in interfacial performance: under impact loading, the fibers undergo fracture rather than premature debonding and pull-out. This behavior is attributed to the optimal concentration of nanochitosan, which enhances fiber–matrix adhesion and enables efficient stress transfer from the matrix to the reinforcing fibers. Unlike fiber pull-out, which dissipates minimal energy, fiber fracture is an energy-intensive failure mechanism that substantially increases the composite’s capacity to absorb impact energy. The FESEM image clearly shows broken fiber ends embedded in the matrix, confirming strong interfacial bonding. Such microstructural features are indicative of a more ductile and damage-tolerant failure mode, reflecting the system’s enhanced ability to dissipate energy and resist catastrophic fracture. These morphological observations are in excellent agreement with findings reported by other researchers [28,29]. Specifically, Sample 13 demonstrates superior mechanical performance, exhibiting higher tensile strength, elastic modulus, and notably enhanced impact strength compared to formulations containing lower nanochitosan loadings. The FESEM micrographs in Figure 3 and Figure 4 not only corroborate the improved fiber–matrix interfacial adhesion but also clearly elucidate the underlying microstructural mechanisms responsible for the enhanced mechanical properties. Collectively, these results underscore the critical role of nanochitosan as an effective compatibilizer in optimizing the overall performance of PLA/SMR20-based biocomposites.

Figure 5 presents the FESEM micrograph of the cryogenically fractured surface of Sample 8, composed of 6 wt% nanochitosan, 10 wt% kenaf fibers, and 30 wt% SMR20 in a PLA matrix. The sample was impact-tested at liquid nitrogen temperature to suppress plastic deformation and reveal a clear, brittle fracture surface suitable for detailed morphological analysis. The micrograph reveals a distinct nanoscale agglomerate of nanochitosan particles localized within the PLA/SMR20 matrix. This clustering is a common phenomenon at elevated nanoparticle loadings and reflects both heterogeneous dispersion and limited interfacial compatibility between nanochitosan and the PLA/SMR20 matrix.

The presence of such nanochitosan agglomerates in the composite microstructure can significantly degrade mechanical performance. These clusters act as structural defects and serve as stress concentration sites. Under mechanical loading, particularly during impact, the localized stress around these agglomerates intensifies, creating favorable conditions for crack nucleation and subsequent propagation.

Moreover, nanochitosan agglomeration significantly reduces the effective interfacial contact area between the nanoparticles and the PLA/SMR20 matrix. At optimal loadings such as 4 wt%, nanochitosan particles are uniformly dispersed at the fiber–matrix interface, where they enhance interfacial adhesion through polar interactions and hydrogen bonding with both the kenaf fibers and the PLA/SMR20 matrix. In contrast, at higher concentrations (e.g., 6 wt%), the strong self-association tendency of nanochitosan driven by intermolecular hydrogen bonding between adjacent particles promotes the formation of larger agglomerates. These clusters not only lose their effectiveness as compatibilizing agents but also act as structural defects that compromise matrix integrity and serve as potential sites for stress concentration and crack initiation.

These morphological observations are fully consistent with mechanical trends reported in the literature [30,31]. Specifically, Sample 8 exhibits reduced tensile strength, elastic modulus, and most notably impact strength compared to formulations containing 4 wt% nanochitosan, such as Sample 12.

3.2. Effects of Nanochitosan, Kenaf Fiber, and SMR20 Content on Tensile Strength

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) results for the tensile strength quadratic model are presented in Table 4. The model is highly significant (F-value = 117.95, p < 0.0001), explaining over 99% of the data variability (R2 = 0.9935, Adjusted R2 = 0.9869). The high predictive R2 (0.9266) confirms robust generalizability.

Table 4.

ANOVA for Quadratic model of Tensile Strength.

The key significant factors (p < 0.05) are:

Linear Effects: All three components—Nanochitosan (A), Kenaf fiber (B), and SMR20 (C).

Quadratic Effects: Nanochitosan (A2) and Kenaf fiber (B2).

Interaction Effect: Kenaf fiber × SMR20 (BC).

This significance profile quantitatively confirms that tensile strength depends non-linearly on nanochitosan and kenaf content (evident from the quadratic terms) and is influenced by a synergistic interaction between the fiber and the elastomer. The insignificant lack-of-fit (p > 0.05) validates the model adequacy.

The coefficients of the second-order polynomial equation were estimated using multiple regression analysis based on the ANOVA results. After removing statistically insignificant terms, the resulting quadratic model expressed in terms of coded variables is as follows:

Tensile Strength = 83.83 − 5.95X_1 + 13.66X_2 − 8.38X_3 − 34.68X_1^2 − 4.91X_3^2 + 8.74X_2 X_3

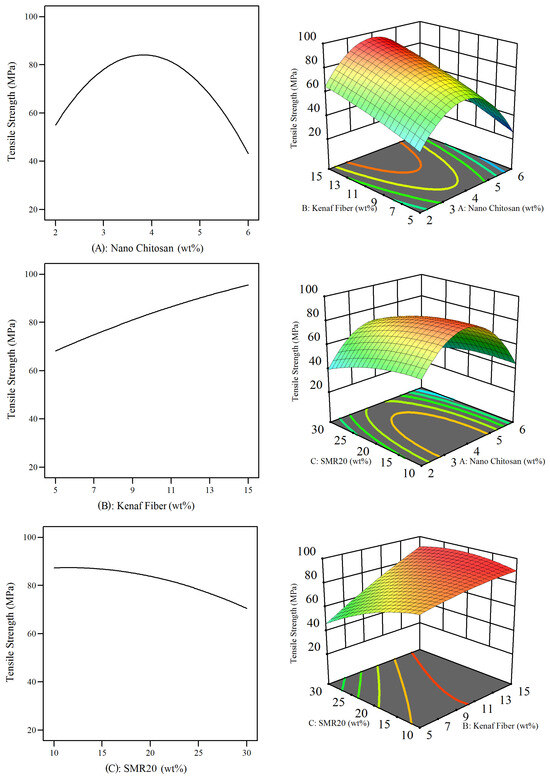

Figure 6 presents the main effects and response surface plots showing the influence of each material on tensile strength. As shown, increasing the nanochitosan content to 4 wt% significantly enhanced the tensile strength of the nanocomposites. However, further increasing the nanochitosan loading to 6 wt% not only halted this improvement but also resulted in a reduction in tensile strength falling below even that of the neat PLA sample. The observed increase in tensile strength within the 1–4 wt% nanochitosan loading range can be attributed primarily to three key mechanisms. First, chitosan nanoparticles, owing to their high specific surface area and abundant surface functional groups (notably amine and hydroxyl groups), form strong hydrogen bonds with the PLA matrix, facilitating efficient stress transfer across the interfacial region. Second, at these low concentrations, the nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed throughout the matrix, establishing a percolating network that effectively hinders crack initiation and propagation. Third, electron microscopy analyses reveal that nanochitosan in this concentration range enhances interfacial adhesion by filling microvoids and interfacial gaps between the kenaf fibers and the PLA/SMR20 matrix, thereby improving load-bearing efficiency.

Figure 6.

Main effects and response surface plots for the influence of each material on Tensile Strength.

The decline in tensile strength at nanochitosan contents exceeding 4 wt% can be attributed to multiple interrelated mechanisms. The dominant factor is the agglomeration of chitosan nanoparticles at elevated loadings, resulting in the formation of nanoscale clusters. These agglomerates act as stress concentration sites, facilitating crack initiation and propagation. Moreover, excessive nanochitosan disrupts the recrystallization of PLA chains by introducing physical barriers that impede molecular reorganization, thereby further reducing tensile strength [32].

Further analysis reveals that at the optimal loading of 4 wt%, nanochitosan promotes a more integrated composite structure by forming molecular bridges between the polar functional groups of natural rubber and kenaf fibers. However, at higher concentrations, nanochitosan nanoparticles tend to adsorb onto the surface of kenaf fibers, thereby inhibiting direct interfacial bonding between the fibers and the PLA/SMR20 matrix. These findings are significant in two respects: first, they underscore that precise optimization of nanochitosan content is critical in the design of high-performance bio-based composites; second, they demonstrate that excessive nanoparticle loading can exert detrimental effects on interfacial adhesion and, consequently, on mechanical properties [33].

As shown in Figure 6, the incorporation of kenaf fibers at loadings between 5 and 15 wt% into PLA/SMR20-based nanocomposites leads to a continuous and significant enhancement in tensile strength. Kenaf fibers serve as highly effective natural reinforcements owing to their unique lignocellulosic structure. The hydroxyl groups on their surface form hydrogen bonds with the PLA matrix, promoting strong interfacial adhesion. Moreover, the alignment of fibers within the matrix facilitates efficient load transfer, while the three-dimensional network they form helps distribute stress more uniformly and mitigates localized stress concentrations. Notably, a synergistic interaction between kenaf fibers and nanochitosan further enhances the overall mechanical performance of the biocomposite [34,35].

Nanochitosan further enhances interfacial adhesion by filling the voids and micro-pores at the interface between the fibers and the PLA/SMR20 matrix. While increasing the kenaf fiber content up to 15 wt% results in a progressive improvement in tensile strength, this trend is expected to reverse beyond a certain threshold. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that fiber loadings exceeding 20–25 wt% typically lead to a decline in tensile strength, primarily due to fiber agglomeration and reduced dispersion uniformity. Moreover, excessive fiber content can compromise the composite’s flexibility and processability [36].

It is also observed that the incorporation of SMR20 natural rubber reduces the tensile strength of the composite. This reduction primarily stems from the inherent incompatibility between the two components and their weak interfacial interactions. Polylactic acid (PLA), as a semi-crystalline polymer, possesses a regular molecular structure and relatively high tensile strength, whereas SMR20 is a natural elastomer with an amorphous, flexible chain architecture and significantly lower tensile strength. Upon blending SMR20 into the PLA matrix, multiple mechanisms concurrently contribute to strength degradation. First, SMR20 domains act as soft inclusions within the rigid PLA matrix, undergoing pronounced deformation under tensile loading. This localized strain induces stress concentration around the rubber particles, promoting crack initiation. Second, the presence of SMR20 diminishes the density of effective intermolecular load-bearing interactions, as the elastomeric chains of SMR20 are less capable of participating in stress transfer compared to the stiffer PLA chains.

3.3. Effects of Nanochitosan, Kenaf Fiber, and SMR20 Content on Elastic Modulus

As shown in Table 5, the quadratic model for elastic modulus is statistically highly significant (F-value = 55.22, p = 0.0002), with excellent explanatory power (R2 = 0.9900, Adjusted R2 = 0.9721). The close match between Adjusted and Predicted R2 (R2Pred = 0.0555) indicates no overfitting.

Table 5.

ANOVA for Quadratic model of Elastic Modulus.

Statistical analysis identifies the following significant terms (p < 0.05):

Linear Effects: Kenaf fiber (B) and SMR20 (C).

Quadratic Effects: Nanochitosan (A2) and Kenaf fiber (B2).

Interaction Effects: Nanochitosan × Kenaf fiber (AB) and Nanochitosan × SMR20 (AC).

Notably, the linear effect of nanochitosan (A) is not significant, but its quadratic effect (A2) and interactions (AB, AC) are. This indicates that nanochitosan’s influence on stiffness is not a simple linear reinforcement but is governed by optimal dispersion (quadratic term) and its coupled effect with other components (interaction terms).

The coefficients of the second-order polynomial equation were estimated using multiple regression analysis based on the ANOVA results. After removing statistically insignificant terms, the resulting quadratic model expressed in terms of coded variables is as follows:

Elastic Modulus = 5.66 + 0.512X_2 − 0.525X_3 − 0.92X_1^2 + 0.279X_2^2 − 0.225X_1 X_2 − 0.25X_1 X_3

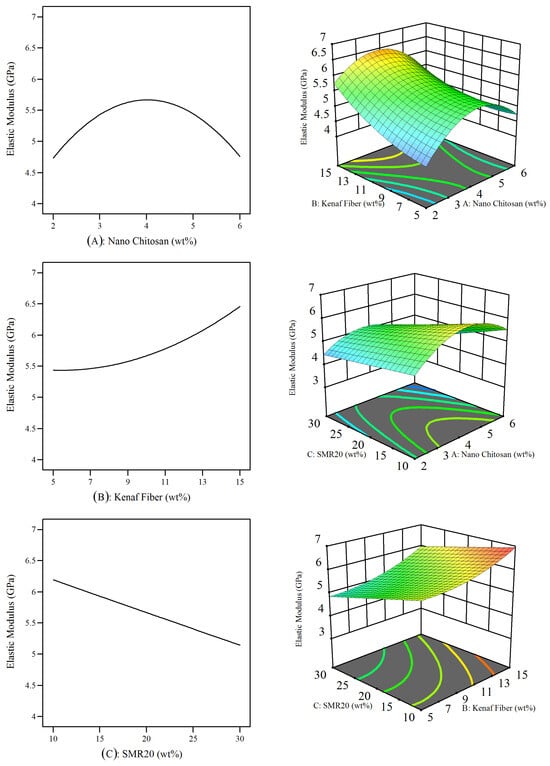

The influence of each constituent material on the elastic modulus is illustrated by the main effects and response surface plots presented in Figure 7. As shown, the elastic modulus of PLA/SMR20 biocomposites exhibits a nonlinear dependence on nanochitosan content. Response surface methodology (RSM) plots reveal that increasing nanochitosan from 2 to 4 wt% leads to a significant enhancement in elastic modulus. However, further addition of nanochitosan beyond 4 wt% up to 6 wt% results in a decline in modulus. This non-monotonic behavior can be attributed to two competing mechanisms at the microstructural level: at optimal loadings, well-dispersed nanochitosan nanoparticles act as effective reinforcing agents, whereas at higher concentrations, particle agglomeration occurs, creating stress concentration sites that compromise mechanical performance [37].

Figure 7.

Main effects and response surface plots for the influence of each material on Elastic Modulus.

Within the loading range of 2 to 4 wt%, nanochitosan is uniformly dispersed throughout the PLA matrix, providing a large interfacial contact area with the polymer phase. The nanoscale dimensions, inherent rigidity, and abundant surface functional groups, particularly hydroxyl (–OH) and amine (–NH2) groups of nanochitosan, facilitate strong physical and chemical interactions with PLA chains. These interactions restrict segmental mobility of the polymer chains and enhance the overall stiffness of the composite, thereby increasing the elastic modulus. Furthermore, nanochitosan acts as an effective nucleating agent, promoting PLA crystallization. The resulting increase in crystallinity further contributes to the enhancement of stiffness and elastic modulus.

However, at higher loadings (e.g., 6 wt%), the tendency of nanochitosan particles to agglomerate and form heterogeneous clusters within the PLA/SMR20 matrix increases significantly. These agglomerates not only reduce the effective interfacial contact area between the nanoparticles and the matrix but also act as microscopic defects and stress concentration sites, thereby compromising structural homogeneity. Under such conditions, stress transfer from the matrix to the reinforcing phase becomes inefficient, leading to deterioration in the composite’s mechanical performance. This effect is particularly pronounced in multiphase systems like PLA/SMR20, which inherently face challenges related to phase compatibility. Although SMR20 rubber enhances toughness, its presence combined with high nanochitosan concentrations can introduce complex three-phase interactions that further hinder the uniform dispersion of nanoparticles and exacerbate agglomeration.

Consequently, the nonlinear relationship between elastic modulus and nanochitosan content underscores the critical need to identify an optimal nanoparticle concentration in the design of nanobiocomposites. These findings align with previous studies in the field, which consistently report a decline in mechanical properties when nanoparticle loading exceeds a critical threshold, typically due to agglomeration and poor interfacial adhesion. Therefore, to maximize the elastic modulus in the PLA/SMR20/kenaf fiber system, nanochitosan content in the range of 2–4 wt% is recommended as the optimal formulation. It was also observed that the incorporation of kenaf fibers into the PLA/SMR20 matrix up to 15 wt% led to a continuous and significant increase in the elastic modulus of the resulting composites. Specifically, as the kenaf fiber content increased from 5 to 10 and then to 15 wt%, the elastic modulus exhibited a consistent upward trend. This enhancement can be primarily attributed to the inherently high stiffness of kenaf fibers relative to both the PLA matrix and the elastomeric SMR20 phase. As a natural reinforcement with a high modulus, kenaf fibers effectively restrict matrix deformation under load, thereby substantially improving the overall rigidity of the composite system [38].

In the composite structure, kenaf fibers function as a reinforcing phase by effectively transferring and absorbing the applied load from the softer PLA/SMR20 matrix, thereby limiting excessive deformation. As the fiber content increases, the number of stress transfer sites rises, and a percolating fiber network gradually develops throughout the matrix, enhancing the composite’s resistance to elastic deformation. This effect is particularly pronounced in the 10–15 wt% range, where kenaf fibers are present in sufficient concentration to form a continuous and mechanically efficient network—without inducing severe issues such as fiber agglomeration or compromised interfacial adhesion [39].

In addition, the surface of kenaf fibers is rich in hydroxyl groups, which can promote substantial physical interactions with the PLA/SMR20 matrix. Although compatibility with hydrophobic matrices such as PLA remains a challenge, the presence of the SMR20 phase combined with optimized processing conditions (e.g., internal mixing and controlled hot-press temperature) enhances interfacial adhesion. While these interactions are primarily physical and relatively weak from a chemical standpoint, they are sufficient to enable effective stress transfer from the matrix to the fibers, provided that the fibers are uniformly dispersed and free from agglomeration. This is further corroborated by the response surface plots, which consistently show that, at all fixed levels of nanochitosan and SMR20, increasing the kenaf fiber content leads to a monotonic increase in elastic modulus. This trend underscores the dominant and beneficial role of kenaf fibers in enhancing the stiffness of the composite system. Overall, kenaf fibers serve as an effective and stable reinforcement in PLA/SMR20 biocomposites, significantly enhancing the stiffness and elastic modulus of the material up to a loading of 15 wt%. This finding holds considerable relevance for industrial applications, as the incorporation of natural fibers not only improves mechanical performance but also enhances the biocompatibility and biodegradability of the final product, aligning with the growing demand for sustainable and eco-friendly composite materials [40].

As shown in Figure 7, the incorporation of SMR20 natural rubber into the PLA matrix at loadings ranging from 10 to 30 wt% led to a continuous and significant reduction in the elastic modulus of the resulting composites. This trend is fully consistent with the inherent mechanical characteristics of elastomeric polymers: SMR20 exhibits a very low modulus and highly flexible, soft behavior, which stands in stark contrast to the relatively rigid and glassy nature of PLA. Consequently, the addition of this low-stiffness rubber phase effectively lowers the overall stiffness of the composite system [41].

In composite systems, the incorporation of an elastomeric phase such as SMR20 introduces a flexible, low-modulus component that reduces the overall stiffness of the material. This soft phase increases the mobility of the polymer chains in the matrix, rendering the structure more susceptible to deformation under tensile loading and diminishing its resistance to elastic strain. Consequently, as the SMR20 content increases, the volume fraction of the elastomeric phase rises, amplifying its influence on the composite’s global mechanical response. Since the elastic modulus is a direct measure of a material’s stiffness and resistance to elastic deformation, it is inherently sensitive to this shift in phase composition and decreases accordingly.

Moreover, poly(lactic acid) (PLA) is an inherently brittle polymer with relatively high crystallinity and a strong propensity for brittle fracture. The primary role of SMR20 in PLA-based composites is therefore to enhance toughness and impact resistance, not to improve stiffness. The observed reduction in elastic modulus can thus be regarded as a trade-off for achieving superior energy absorption capacity. By forming dispersed soft domains within the rigid PLA matrix, SMR20 promotes toughening mechanisms such as crazing, microvoid formation, interfacial debonding, and stress redistribution. While these mechanisms significantly improve impact strength, they concurrently lower the composite’s overall rigidity.

From a microstructural standpoint, blends containing high loadings of SMR20 (particularly 20–30 wt%) may promote the formation of more continuous rubbery phases or larger dispersed particles within the PLA matrix. Such morphological features can compromise blend homogeneity and reduce interfacial stress transfer efficiency. Although a relatively uniform dispersion of SMR20 was achieved in this study through melt blending in an internal mixer followed by hot pressing, the inherently soft and low-modulus nature of the SMR20 phase alone is sufficient to significantly diminish the composite’s elastic modulus.

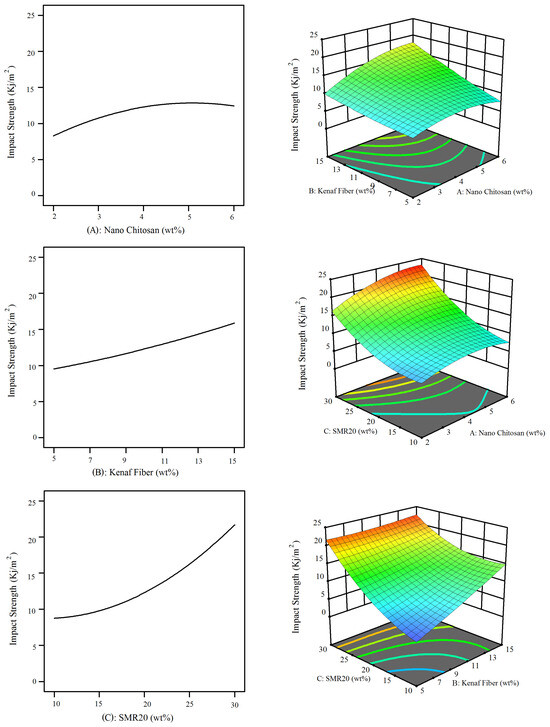

3.4. Effects of Nanochitosan, Kenaf Fiber, and SMR20 Content on Impact Strength

The ANOVA for the impact strength model (Table 6) reveals exceptional significance (F-value = 119.10, p < 0.0001). The model accounts for 99.5% of the variability (R2 = 0.9954) and shows strong predictive ability (Predicted R2 = 0.9267).

Table 6.

ANOVA for Quadratic model of Impact Strength.

All linear terms and nearly all interaction/quadratic terms are significant (p < 0.05):

Linear Effects: Nanochitosan (A), Kenaf fiber (B), and SMR20 (C)—with SMR20 showing the strongest individual influence (highest F-value).

Quadratic Effects: Nanochitosan (A2) and SMR20 (C2).

Interaction Effects: All two-way interactions (AB, AC, BC).

This comprehensive significance underscores the complex, synergistic toughening mechanism in the hybrid composite. The dominant linear effect of SMR20 confirms its primary role as an impact modifier, while the significance of all interactions highlights how the combined presence of nanochitosan, fiber, and elastomer jointly dictates the toughness.

The coefficients of the second-order polynomial equation were estimated using multiple regression analysis based on the ANOVA results. After removing statistically insignificant terms, the resulting quadratic model expressed in terms of coded variables is as follows:

Impact Strength = 12.273 + 2.076X_1 + 3.171X_2 + 6.470X_3 − 1.928X_1^2 + 2.935X_3^2 + 1.843X_1 X_2 + 1.305X_1 X_3 − 2.680X_2 X_3

The influence of each constituent material on impact strength is illustrated in the main effects and response surface plots presented in Figure 8. As shown, increasing the nanochitosan content up to 4 wt% leads to a significant improvement in impact strength. However, further addition beyond this threshold, specifically at 6 wt%, results in a noticeable decline in this mechanical property. This non-monotonic behavior can be attributed to a combination of physical, chemical, and morphological factors, including nanoparticle dispersion quality, interfacial adhesion, and the formation of stress-concentrating agglomerates at higher loadings [42].

Figure 8.

Main effects and response surface plots for the influence of each material on Impact Strength.

At low to moderate loadings (up to 4 wt%), nanochitosan is uniformly dispersed within the PLA/SMR20 matrix and significantly enhances interfacial adhesion between the filler and the matrix phases. This improvement stems from the abundance of reactive functional groups in chitosan—particularly amino (–NH2) and hydroxyl (–OH) groups, which facilitate the formation of strong hydrogen bonds and potential covalent interactions with the PLA/SMR20 matrix. These interfacial bonds promote efficient stress transfer and suppress the initiation and propagation of microcracks. Moreover, well-dispersed nanochitosan particles act as effective crack arresters: under impact loading, energy is dissipated through multiple toughening mechanisms, including crack deflection, nanoparticle debonding and pull-out, and the formation of localized plastic deformation (yield) zones around the nanoparticles, leading to enhanced energy absorption.

However, when the nanochitosan content exceeds 4 wt% and reaches 6 wt%, the previously observed improvement in impact strength reverses, leading to a notable decline. This reduction is primarily attributed to the poor dispersion of nanoparticles and the formation of agglomerates within the PLA/SMR20 matrix. At higher loadings, nanochitosan particles tend to aggregate due to strong intermolecular van der Waals forces. These agglomerates act as stress concentration sites, introducing structural weaknesses in the composite. Under impact loading, rather than hindering crack propagation, these clusters promote the early initiation and accelerated growth of microcracks, thereby diminishing the overall toughness of the material [43].

It was also observed that increasing the weight percentage of kenaf fibers in the PLA/SMR20 matrix of the nanocomposite enhanced the impact strength. This improvement can be attributed to the effective reinforcing role of natural kenaf fibers within the composite structure. Kenaf fibers possess high tensile strength, low density, and excellent energy absorption capacity characteristics that make them particularly well-suited for enhancing the mechanical performance, especially impact resistance, of polymeric composites.

When embedded in a PLA/SMR20 matrix, kenaf fibers effectively facilitate the transfer of applied impact loads throughout the composite. This efficient stress transfer is primarily attributed to the strong interfacial adhesion between the fiber surface and the matrix, which is enhanced by the presence of polar functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH) and carboxyl (–COOH) in the cellulose and lignin components of kenaf fibers. These groups promote robust fiber matrix bonding through hydrogen bonding and other physicochemical interactions, thereby minimizing interfacial debonding and fiber pull-out under impact loading [44].

Kenaf fibers act as effective agents for arresting crack propagation. Under impact loading, microcracks initiated in the PLA/SMR20 matrix are deflected, pinned, or halted upon encountering kenaf fibers, a mechanism known as crack deflection. This process increases the tortuosity and overall length of the crack propagation path, thereby dissipating more energy before catastrophic failure. Additionally, energy absorption is further enhanced through mechanisms such as fiber pull-out and fiber fracture, both of which require significant work to debond fibers from the matrix or break them, respectively. These toughening mechanisms collectively contribute to the improved impact strength of the composite.

The three-dimensional network formed by kenaf fibers within the PLA/SMR20 matrix promotes a more uniform distribution of impact-induced stresses throughout the composite volume, thereby mitigating stress concentration and delaying crack initiation. This characteristic is especially critical under dynamic and impact loading conditions, where a rapid and homogeneous structural response is essential for energy absorption and damage resistance [45].

In general, increasing the kenaf fiber content up to an optimal level enhances multiple energy absorption mechanisms such as efficient stress transfer, crack deflection, fiber elongation and fracture, and stress dispersion, thereby significantly improving the impact strength of the nanocomposite. However, this beneficial effect is typically limited to a certain threshold; beyond the optimal fiber loading, impact performance may decline due to poor fiber dispersion, agglomeration, or a reduction in matrix toughness. In the present study, however, the incorporation of kenaf fibers within the investigated range (up to 15 wt%) did not induce severe heterogeneity or agglomeration, and consequently, a continuous increase in impact strength was observed with increasing fiber content.

It was also observed that increasing the content of SMR20 natural rubber in the nanocomposite matrix led to a significant enhancement in impact strength. This favorable response is primarily attributed to the elastomeric character of natural rubber and its capacity to absorb and dissipate energy under dynamic loading conditions. SMR20 (Standard Malaysian Rubber 20), composed of long, flexible polyisoprene chains with a highly elastic molecular architecture, undergoes substantial elastic and plastic deformation upon impact. This energy-dissipating mechanism effectively delays crack propagation and prevents catastrophic, brittle failure of the composite [46].

The incorporation of natural rubber into the PLA matrix enhances the toughness of the composite through several well-established energy-dissipating mechanisms. First, natural rubber acts as an elastomeric dispersed phase that promotes the formation of localized plastic deformation zones around the rubber particles during impact, thereby dissipating a significant amount of energy. Second, the presence of rubber particles induces microcracking in the surrounding matrix. The initiation and propagation of these microcracks absorb additional energy, contributing to increased overall fracture resistance prior to catastrophic failure. Third, rubber particles impede crack propagation through mechanisms such as crack pinning and crack deflection. When a propagating crack encounters a rubber particle, it is either temporarily arrested (pinned) or forced to change direction (deflected), resulting in a longer and more tortuous crack path. This increased path length further enhances energy absorption during fracture.

In this study, the incorporation of natural rubber (SMR20) contributed to a significant enhancement in impact strength, as shown in Table 3. While SMR20 lacks the reactive epoxy groups of its modified counterparts (e.g., ENR), the observed mechanical improvement and the FESEM micrographs (Figure 3 and Figure 4), which show a coherent polymer blend morphology without gross phase separation, suggest that an adequate level of interfacial adhesion was achieved under the employed melt-blending conditions. This indicates that standard SMR20 can be an effective toughening agent for PLA when processed appropriately. This effective bonding facilitates efficient stress transfer from the matrix to the rubber phase and helps prevent premature debonding during mechanical loading. In some cases, however, controlled interfacial debonding or micro-delamination at the rubber–matrix interface can act as an additional energy-dissipating mechanism, further enhancing toughness. Beyond interfacial effects, SMR20 imparts flexibility to the composite system by mitigating the inherent brittleness of the PLA matrix. While the incorporation of rigid reinforcements—such as nanoparticles or natural fibers—often improves stiffness and strength, it can simultaneously reduce impact resistance. In this context, SMR20 functions as an effective toughening agent, striking an optimal balance between strength and ductility, which is critical for withstanding impact loads.

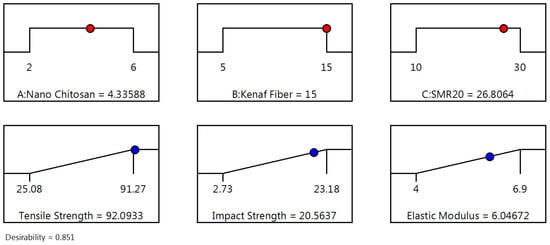

3.5. Optimization of Mechanical Properties of Bio-Based Composites Using Response Surface Methodology

To optimize the overall mechanical performance of the biocomposite, tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength must be maximized simultaneously. This multi-response optimization problem was addressed using the desirability (utility) function approach, a widely accepted method for balancing competing responses. In this framework, each response is individually transformed into a dimensionless desirability value d ranging from 0 to 1, where d = 0 represents an unacceptable response and d = 1 corresponds to the ideal (target) performance. Since all three mechanical properties tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength are of the “larger-the-better” type, their individual desirability functions were defined accordingly. The general form of the desirability function used in this study is given by Equation (2) [23]:

d = {█(0 y < L@((y − L)/(T − L))^r L ≤ y ≤ T@1 y > T)}

In the desirability function approach, y represents the predicted response, T is the target (or desired) value, L is the lower acceptable limit, and r is a shape parameter (weighting exponent) that reflects the relative importance of approaching the target. When r = 1, the desirability function is linear. Values of r > 1 place greater emphasis on responses close to the target, whereas 0 < r < 1 indicate reduced sensitivity to deviations from the target, resulting in a flatter desirability curve near T. In general, the utility function is expressed as Equation (3) [47]:

where n represents the number of responses considered in the optimization. The overall desirability function D is defined as the geometric mean of the individual desirability values corresponding to the three key mechanical responses:

where D ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a more favorable combination of factor settings (e.g., nanochitosan, kenaf fiber, and SMR20 contents, denoted collectively as x). Each individual desirability function di transforms the predicted response value into a dimensionless scale between 0 and 1: di = 0 signifies an unacceptable performance (below the lower limit), while di = 1 represents a response at or above the target value. Since all three properties tensile strength, elastic modulus, and impact strength are of the “larger-the-better” type, their desirability functions are constructed to increase monotonically with the response. The cubic root (i.e., exponent 1/3) reflects the geometric averaging of three responses, ensuring that a poor performance in any single property significantly reduces the overall desirability. This approach, based on the Derringer–Suich methodology, effectively balances competing mechanical requirements and enables the identification of optimal formulation conditions that simultaneously maximize strength, stiffness, and toughness.

D = [(d_1 d_2…d_n)]^(1⁄n)

D = [(d_1 (tensile strength(x)) × d_2 (elastic modulus(x) × d_3 (impact strength(x))))]^(1/3)

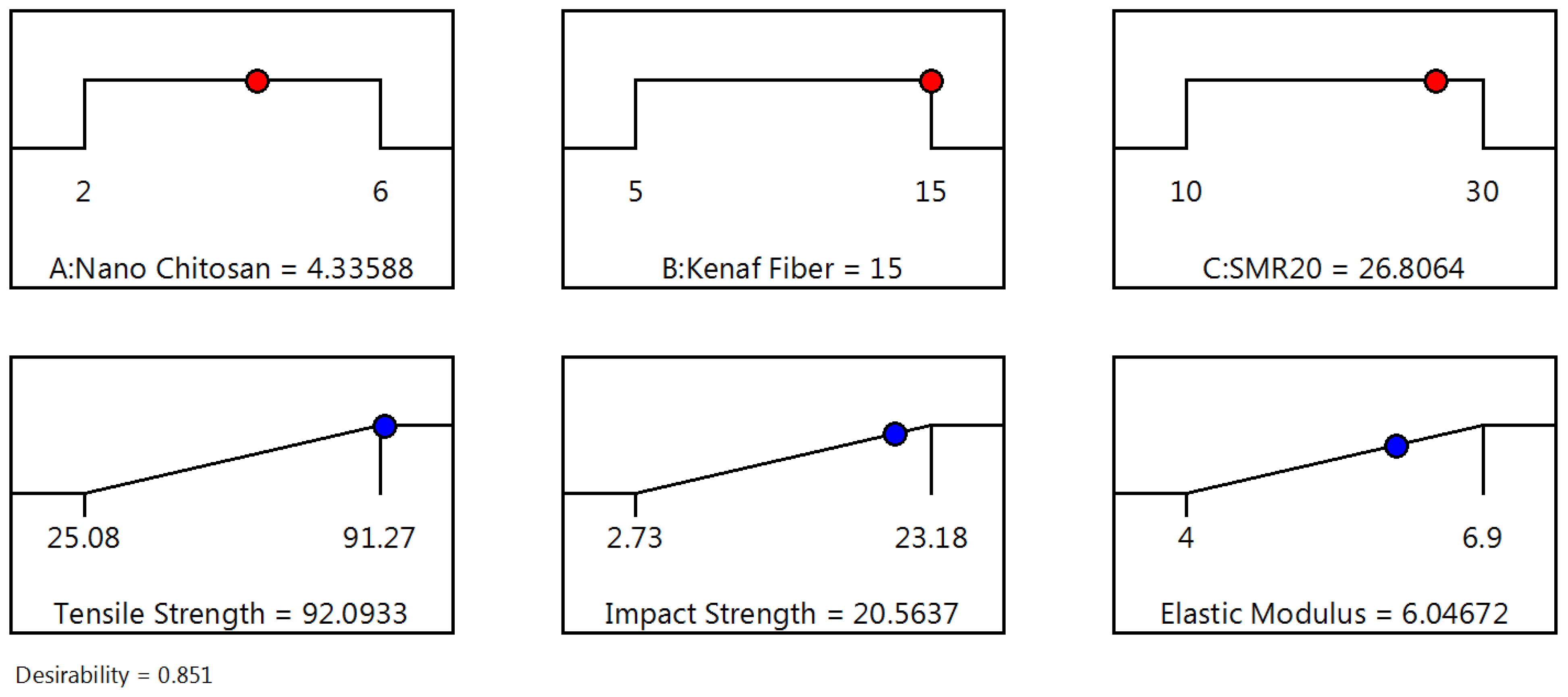

Figure 9 presents the results of the desirability function analysis for simultaneous optimization of the mechanical properties. The optimization analysis pinpointed a unique optimal composition within the design space: 4.33 wt% nanochitosan, 15 wt% kenaf fiber, and 26.80 wt% SMR20, achieving a maximum overall desirability of D = 0.851. This point does not correspond exactly to any of the originally tested runs but lies between them (notably, between Samples 10 and 12 in terms of SMR20 content), demonstrating the model’s power to interpolate and refine the optimum beyond the initial experimental grid. The predicted mechanical properties at this optimum were: tensile strength of 92.09 MPa, elastic modulus of 6.04 GPa, and impact strength of 20.56 kJ/m2.

Figure 9.

Desirability plot for simultaneous optimization of process parameters.

A confirmation experiment at the predicted optimum yielded excellent agreement with the model (Table 7), validating its predictive accuracy. To address the interesting observation regarding similar performance across different compositions, a direct comparison is insightful. The predicted optimum (26.8% SMR20) and Sample 12 (30% SMR20) exhibit comparable high levels of impact strength, attributable to their high elastomer content. However, Sample 10 (10% SMR20), while having significantly less rubber, also approaches the optimal performance. This is due to a compensating reinforcement effect: the high kenaf fiber content (15% in all three cases) in Sample 10 provides substantial stiffness and strength, partially offsetting the lower toughness imparted by SMR20. The optimization model successfully captures these trade-offs, identifying the precise SMR20 level (~26.8%) that synergizes with the fixed high kenaf content to maximize the overall desirability, without the excessive loss of stiffness that very high rubber content might cause. Therefore, the optimization provides critical insight: while acceptable performance can be achieved with different SMR20/PLA ratios (as in Samples 10 and 12), the true optimum represents a calculated balance that the desirability function quantifies, which would not be evident from examining individual experimental runs alone.

Table 7.

Predicted versus experimental mechanical properties under optimal conditions from the confirmation experiment.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the mechanical properties of natural nanocomposites based on a PLA/SMR20 matrix reinforced with nanochitosan and kenaf fibers were experimentally investigated using the Response Surface Methodology (RSM). The key findings are summarized as follows:

- The addition of nanochitosan up to 4 wt% to the PLA/SMR20 matrix resulted in a 39% increase in tensile strength. However, further increasing the nanochitosan content beyond this threshold led to a 24% reduction in tensile strength, attributed to nanoparticle agglomeration and poor interfacial adhesion. Increasing kenaf fiber content to 15 wt% enhanced the tensile strength by 44%, demonstrating its effective reinforcing role. In contrast, the incorporation of SMR20 natural rubber caused a 17% decrease in tensile strength due to its elastomeric nature, which reduces stiffness.

- The elastic modulus increased by 22% with the addition of up to 4 wt% nanochitosan, owing to the rigid structure and high surface interaction of the nanoparticles. However, increasing the nanochitosan content to 6 wt% led to a 14% reduction in elastic modulus, primarily due to particle aggregation and the formation of stress concentration sites. Incorporating 15 wt% kenaf fibers significantly improved the elastic modulus by 26%, confirming their reinforcing efficiency. Conversely, the addition of SMR20 natural rubber reduced the elastic modulus by 20%, consistent with its soft and flexible characteristics.

- Impact strength was enhanced by 27% when nanochitosan was added up to 4 wt%, benefiting from improved energy dissipation mechanisms such as crack deflection and interfacial bonding. Further increasing nanochitosan to 6 wt% slightly reduced impact strength by 3%, likely due to agglomeration-induced brittleness. The inclusion of kenaf fibers (up to 15 wt%) increased impact strength by 37%, while the addition of SMR20 natural rubber (up to 30 wt%) significantly improved impact resistance by 59%, highlighting its excellent toughening effect through plastic deformation and energy absorption.

- Through multi-objective optimization, the optimal composition was determined as 4.33 wt% nanochitosan, 15 wt% kenaf fiber, and 26.80 wt% SMR20. At this formulation, the predicted mechanical properties were tensile strength = 92.09 MPa, elastic modulus = 6.04 GPa, and impact strength = 20.56 kJ/m2. The experimental results closely matched these optimized values, validating the accuracy and reliability of the RSM model.

- The Response Surface Methodology (RSM) successfully identified an optimal composition for balancing tensile and impact properties in this study. Looking forward, the same statistical framework presents a powerful tool for the next stage of development. Future work could employ a similar DoE approach to optimize key processing parameters—such as melt-blending temperature, mixing speed and time, hot-pressing conditions, and the concentration of any additional compatibilizers—for the best-performing formulation identified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R.; Methodology, M.N.N.; Software, N.R.; Validation, N.R.; Formal analysis, H.S., N.R. and M.N.N.; Investigation, M.N.N.; Resources, H.S. and M.N.N.; Data curation, H.S.; Writing—original draft, M.N.N.; Writing—review & editing, N.R.; Project administration, N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, Z.A.; Abid, S.; Banat, I.M. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Characteristics, production, recent developments and applications. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 126, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averous, L.; Pollet, E. Environmental Silicate Nano-Biocomposites; Springer: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications-A comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakeng, R.; Jawaid, M.; Ariffin, H.; Sapuan, S.M.; Asim, M.; Saba, N. Natural fiber reinforced polylactic acid composites: A review. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, O.T.; Adeyomoye, O.; Adetunji, C.O.; Oloruntoba, A. Biocomposites for aerospace engineering applications. In Advances in Biocomposites and Their Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2024; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Farhan, M.; Mastura, M.T.; Ansari, S.P.; Muaz, M.; Azeem, M.; Sapuan, S.M. Advanced potential hybrid biocomposites in aerospace applications: A comprehensive review. Adv. Compos. Aerosp. Eng. Appl. 2022, 21, 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Koronis, G.; Silva, A. (Eds.) Green Composites for Automotive Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, K.; Sarkar, P.; Cerqueira, M. (Eds.) Advances in Biopolymers for Food Science and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wardhono, E.Y.; Kanani, N. Development of polylactic acid (PLA) bio-composite films reinforced with bacterial cellulose nanocrystals (BCNC) without any surface modification. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, N.F.; Ismail, H.; Ishak, K.K. Tailoring Properties of polylactic acid/rubber/kenaf biocomposites: Effects of type of rubber and kenaf loading. BioResources 2020, 15, 5679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E.; Elbi, P.A.; Deepa, B.; Jyotishkumar, P.; Pothen, L.A.; Narine, S.S.; Thomas, S. X-ray diffraction and biodegradation analysis of green composites of natural rubber/nanocellulose. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 2378–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, A.; Tajima, N.; Iwamoto, S.; Morimoto, T.; Nagatani, A.; Okazaki, T.; Endo, T. Properties of natural rubber reinforced with cellulose nanofibers based on fiber diameter distribution as estimated by differential centrifugal sedimentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruz-Cruz, M.A.; Herrera-Franco, P.J.; Flores-Johnson, E.A.; Moreno-Chulim, M.V.; Galera-Manzano, L.M.; Valadez-González, A. Thermal and mechanical properties of PLA-based multiscale cellulosic biocomposites. J. Mater Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongputthipat, W.; Ruksakulpiwat, Y.; Chumsamrong, P. Development of biodegradable biocomposite films from poly (lactic acid), natural rubber and rice straw. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 10289–10307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.K.; Ray, S.S. Chitosan-Based Nanocomposites. In Natural Polymers; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, C.; De Mello, J.M.; Dalcanton, F.; Macuvele, D.L.; Padoin, N.; Fiori, M.A.; Soares, C.; Riella, H.G. Mechanical, thermal and antimicrobial properties of chitosan-based-nanocomposite with potential applications for food packaging. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 1216–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, R.A.; Aisyah, H.A.; Nordin, A.H.; Ngadi, N.; Zuhri, M.Y.; Asyraf, M.R.; Sapuan, S.M.; Zainudin, E.S.; Sharma, S.; Abral, H.; et al. Natural-fiber-reinforced chitosan, chitosan blends and their nanocomposites for various advanced applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, S.; Kandasamy, J.; Venkatesan, S.; Murugan, R.; Lakshmi Narayanan, V.; Sultan, M.T.; Shahar, F.S.; Shah, A.U.; Khan, T.; Sebaey, T.A. A review on the effect of fabric reinforcement on strength enhancement of natural fiber composites. Materials 2022, 15, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Devnani, G.L. Natural Fiber Composites: Processing, Characterization, Applications, and Advancements; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Thapliyal, D.; Verma, S.; Sen, P.; Kumar, R.; Thakur, A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Singh, D.; Verros, G.D.; Arya, R.K. Natural fibers composites: Origin, importance, consumption pattern, and challenges. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyraf, M.R.; Rafidah, M.; Azrina, A.; Razman, M.R. Dynamic mechanical behaviour of kenaf cellulosic fibre biocomposites: A comprehensive review on chemical treatments. Cellulose 2021, 28, 2675–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Karki, B.S.; Gope, P.C. Kenaf Fiber-Reinforced Biocomposites: A Review of Mechanical Performance, Treatments, and Challenges. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2025, 16, 1092. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, B.P.; Akil, H.M.; Affendy, M.G.; Khan, A.; Nasir, R.B. Comparative study of wear performance of particulate and fiber-reinforced nano-ZnO/ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene hybrid composites using response surface methodology. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.P.; Akil, H.M.; Nasir, R.B.; Khan, A. Optimization on wear performance of UHMWPE composites using response surface methodology. Tribol. Int. 2015, 88, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshpayeh, S.; Tarighat, A.; Ghasemi, F.A.; Bagheri, M.S. A fuzzy logic model for prediction of tensile properties of epoxy/glass fiber/silica nanocomposites. J. Elastomers Plast. 2018, 50, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.A.; Niyaraki, M.N.; Ghasemi, I.; Daneshpayeh, S. Predicting the tensile strength and elongation at break of PP/graphene/glass fiber/EPDM nanocomposites using response surface methodology. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2021, 28, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.Z.; Sapuan, S.M.; Roslan, S.A.; Aziz, S.A.; Sarip, S. Optimization of tensile behavior of banana pseudo-stem (Musa acuminate) fiber reinforced epoxy composites using response surface methodology. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 3517–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Varma, H.S.; Varma, I.K. Polyolefin blends: Effect of EPDM rubber on crystallization, morphology and mechanical properties of polypropylene/EPDM blends. 1. Polymer 1991, 32, 2534–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongchom, C.; Refahati, N.; Roodgar Saffari, P.; Roudgar Saffari, P.; Niyaraki, M.N.; Sirimontree, S.; Keawsawasvong, S. An experimental study on the effect of nanomaterials and fibers on the mechanical properties of polymer composites. Buildings 2021, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongchom, C.; Jearsiripongkul, T.; Refahati, N.; Roodgar Saffari, P.; Roodgar Saffari, P.; Niyaraki, M.N.; Hu, L.; Keawsawasvong, S. Optimization of the mechanical behavior of polymer composites reinforced with fibers, nanoparticles, and rubbers. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abifarin, J.K.; Prakash, C.; Singh, S. Optimization and significance of fabrication parameters on the mechanical properties of 3D printed chitosan/PLA scaffold. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 2018–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latos-Brozio, M.; Rułka, K.; Masek, A. Review of Bio-Fillers Dedicated to Polymer Compositions. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 15, e202500406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Arumugam, A.B.; Agrawal, A.P.; Ntumba, Z.N. Development of Hemp Fiber Reinforced PLA Composites for Sustainable 3D Printing: Mechanical and Microstructural Properties. J. Nat. Fibers 2025, 22, 2558214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucpinar, B.; Sivrikaya, T.; Aytac, A. Sustainable hemp fiber reinforced polylactic acid/poly (butylene succinate) biocomposites: Assessing the effectiveness of MAH-g-PLA as a compatibilizer. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 9438–9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Oleiwi, J.K.; Mohammed, A.M.; Jawad, A.J.; Osman, A.F.; Adam, T.; Betar, B.O.; Gopinath, S.C. A Review on the Advancement of Renewable Natural Fiber Hybrid Composites: Prospects, Challenges, and Industrial Applications. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 1237–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundhar, A.; Jayakrishna, K. Investigations on mechanical and morphological characterization of chitosan reinforced polymer nanocomposites. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 075301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dang, R.; Manna, A.; Sharma, S.; Dwivedi, S.P.; Kumar, A.; Li, C.; Abbas, M. Effect of chemically treated kenaf fiber on the mechanical, morphological, and microstructural characteristics of PLA-based sustainable bio-composites fabricated via direct injection molding route. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 31383–31399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyraf, M.R.; Sheng, D.D.; Mas’ood, N.N.; Khoo, P.S. Thermoplastic composites reinforced chemically modified kenaf fibre: Current progress on mechanical and dynamic mechanical properties. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 6629–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharazi, I.; Sulong, A.B.; Omar, R.C.; Muhamad, N. Mechanical durability and degradation characteristics of long kenaf-reinforced PLA composites fabricated using an eco-friendly method. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 57, 101820. [Google Scholar]

- Injorhor, P.; Inphonlek, S.; Ruksakulpiwat, Y.; Ruksakulpiwat, C. Effect of modified natural rubber on the mechanical and thermal properties of poly (Lactic Acid) and its composites with nanoparticles from biowaste. Polymers 2024, 16, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramamurthy, M.; Vasanthkumar, N.P.; Perumal, G.; Senthilkumar, N. Formulation and Features of Chitosan and Natural Fiber Blended Bio-composite towards Environmental Sustainability. J. Environ. Nanotechnol. 2025, 14, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Singh, A. Development and Characterization of Polylactic Acid/Chitosan Based Polymeric Bio-Nanocomposites Reinforced with Hydroxyapatite and Aluminum Oxide Bifiller for Biomedical Application. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 5805–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, M.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Yusoff, M.Z.; Zainudin, E.S. Mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of woven kenaf fiber reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) composites. Fibers Polym. 2022, 23, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamadi, A.H.; Razali, N.; Petru, M.; Taha, M.M.; Muhammad, N.; Ilyas, R.A. Effect of chemically treated kenaf fibre on mechanical and thermal properties of PLA composites prepared through fused deposition modeling (FDM). Polymers 2021, 13, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.F.; Ali, F.; Jami, M.S.; Azmi, A.S.; Ahmad, F.; Marzuki, M.Z.; Muniyandi, S.K.; Zainudin, Z.; Kim, M.P. A Comprehensive Review of Natural Rubber Composites: Properties, Compounding Aspects, and Renewable Practices with Natural Fibre Reinforcement. J. Renew. Mater. 2025, 13, 499–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idumah, C.I.; Hassan, A. Characterization and preparation of conductive exfoliated graphene nanoplatelets kenaf fibre hybrid polypropylene composites. J. Synth. Met. 2016, 212, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.