Abstract

Feature extraction (FE) is an important step in electroencephalogram (EEG)-based classification for brain–computer interface (BCI) systems and neurocognitive monitoring. However, the dynamic and low-signal-to-noise nature of EEG data makes achieving robust FE challenging. Recent deep learning (DL) advances have offered alternatives to traditional manual feature engineering by enabling end-to-end learning from raw signals. In this paper, we present a comparative review of 88 DL models published over the last decade, focusing on EEG FE. We examine convolutional neural networks (CNNs), Transformer-based mechanisms, recurrent architectures including recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM), and hybrid models. Our analysis focuses on architectural adaptations, computational efficiency, and classification performance across EEG tasks. Our findings reveal that efficient EEG FE depends more on architectural design than model depth. Compact CNNs offer the best efficiency–performance trade-offs in data-limited settings, while Transformers and hybrid models improve long-range temporal representation at a higher computational cost. Thus, the field is shifting toward lightweight hybrid designs that balance local FE with global temporal modeling. This review aims to guide BCI developers and future neurotechnology research toward efficient, scalable, and interpretable EEG-based classification frameworks.

1. Introduction

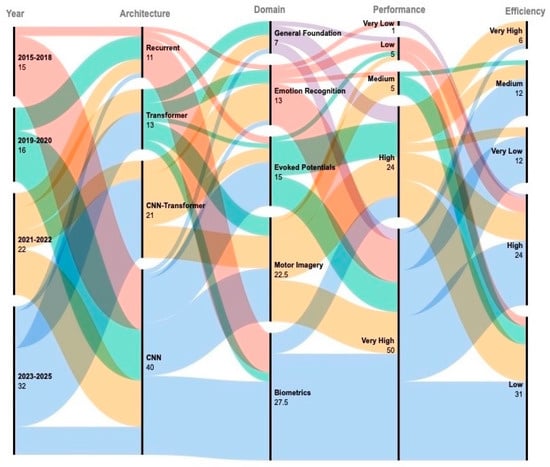

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive and affordable technique for studying brain activity across clinical, cognitive, engineering, and security domains [1]. The classification of different brain states or conditions, such as motor imagery (MI), emotional responses, seizure detection, or cognitive workload, is a major focus in EEG research [2]. EEG is also utilized for biometric authentication and identification, treating neural signals as unique signatures to verify or differentiate individuals [3,4]. Success in these tasks depends on FE to transform raw, noisy, and variable EEG signals into informative and robust representations for machine learning (ML) algorithms [5]. Traditional EEG FE combined common spatial patterns (CSP), wavelet transforms (WTs), and spectral power analysis (SPA) techniques with shallow ML methods like support vector machines (SVMs) for classification. While effective in controlled settings, they are sensitive to noise, intrasubject variability, and the high-dimensional nature of EEG signals [6,7,8]. These approaches require domain expertise and extensive preprocessing. In contrast, modern DL models offer the advantage of learning features directly from raw or minimally processed EEG data. DL models have been applied in classification tasks and user authentication [9,10,11]. Although promising, they face large computational requirements, limited training data, and difficulties in generalizing across subjects and sessions. Many studies have recently focused on designing DL architectures that balance representational power with efficiency. Researchers have adapted CNNs, recurrent networks, Transformer-based models, and hybrid designs to capture temporal, spatial, and frequency features and reduce the computational complexity for EEG signals [12,13]. Efficient FE is key to improve the classification accuracy (Acc.) and enable practical implementation in BCIs and mobile neurotechnology systems [14]. In this review, we survey and compare DL models developed for efficient FE in EEG-based classification between 2015 and 2025. We examine their design principles, computational trade-offs, and reported performance across various EEG applications. The contributions of this paper are as follows:

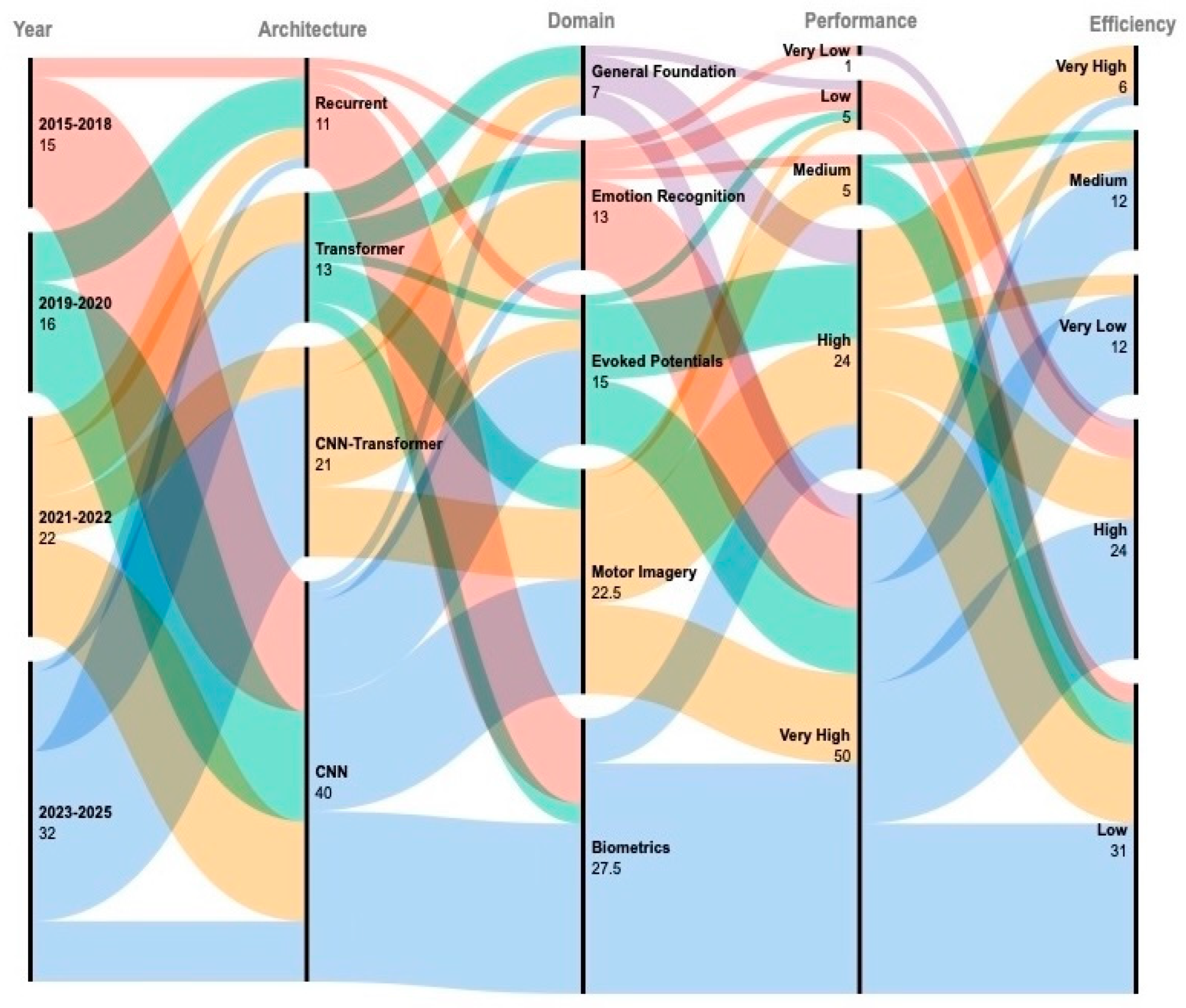

- A comprehensive review of 114 DL-based EEG classification papers, including systematic reviews, CNN-based models, Transformer-based models, CNN–Transformer hybrids, and other recurrent-based hybrids.

- An evaluation and discussion of 88 DL-based EEG models, covering the most common network architectures, along with an analysis of efficiency and performance challenges.

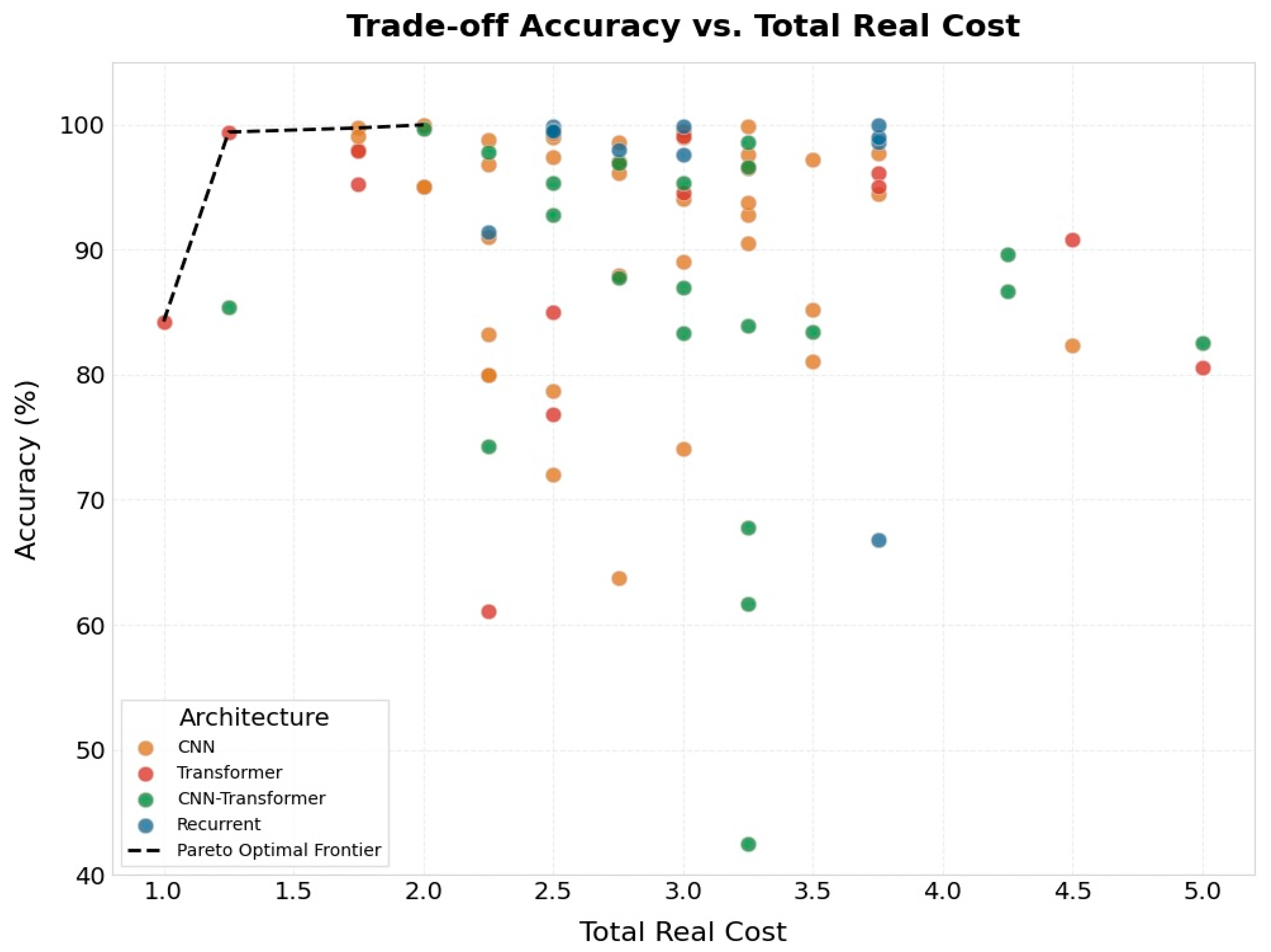

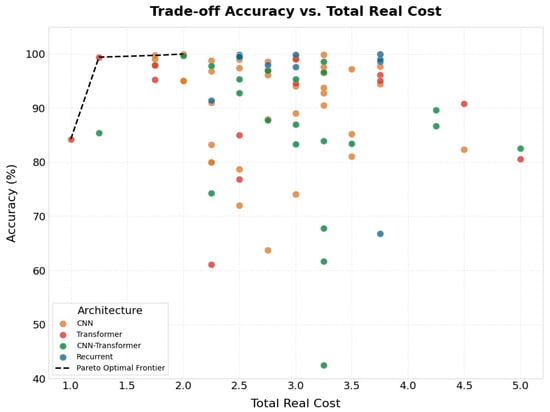

- An in-depth trade-off analysis using different approaches of evaluation to cover a wider spectrum of possible trade-offs.

- The identification of current challenges in DL-based EEG classification and potential directions to inform future research.

The remainder of this review is organized as follows. We first describe the methodology and paper collection process. Next, we provide a brief background for EEG-based classification and existing surveys. We then survey DL models for efficient FE, grouped by architectural family—namely convolutional, Transformer-based, recurrent-based, and hybrid networks. Comparative trade-off insights across these models are highlighted, followed by a discussion of emerging trends, future directions, and recommendations.

2. Methods

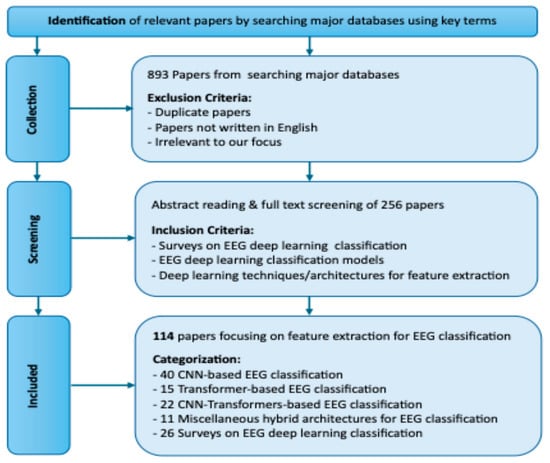

To ensure transparency in conducting our comparative review, we followed a procedure inspired by the PRISMA reporting principles (Figure 1), without claiming a formal systematic review. For a comprehensive review, we collected a total of 114 papers about DL-based EEG classification. The initial screening was based on titles and abstracts. Then, we removed duplicate and irrelevant studies. The remaining papers were reviewed in full to assess their methodologies, FE techniques, DL architectures, and performance metrics. We categorized key information from each study to structurally compare FE strategies.

2.1. Identification

In the selection process used to identify relevant studies, we implemented a title and abstract-based strategy to search major academic research databases, namely IEEE Xplore, Scopus, ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Google Scholar. These databases were chosen to cover engineering, biomedical, ML, and interdisciplinary venues where EEG-based DL studies are published. The IEEE Xplore database consists of articles in engineering and interdisciplinary fields. The Scopus and ScienceDirect databases consist of articles in engineering, computing, and scientific-related research. PubMed comprises bioengineering and neuroscience articles. Google Scholar indexes papers across multiple disciplines and publishers, including engineering, computer science, neuroscience, and biomedicine. For EEG-based DL classification, which spans these domains, Google Scholar helps to capture studies that may not be indexed in a single database. We only considered papers published between 2015 and 2025 to ensure the inclusion of recent and rapid advancements in DL architectures. Using relevant keywords including “EEG”, “feature extraction”, “deep learning”, “classification”, and their combinations, an initial pool of 893 papers was retrieved. The keywords were selected based on common usage in the literature. The acronym “EEG” was used because it is a widely adopted form in paper titles and abstracts across relevant fields, which made it effective for identification during the search phase. The full term “deep learning” was used instead of its acronym to avoid ambiguity, as certain acronyms have different meanings across disciplines. The full term is also commonly used in article titles, which improved the search accuracy.

2.2. Screening

The collected papers were subjected to a multistage screening process. First, titles and abstracts were examined to identify studies relevant to DL-based EEG classification. We removed duplicate records, non-English publications, and studies unrelated to our scope. A total of 256 papers were retained for abstract and full-text examination. Studies were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) surveys on EEG-based classification, (2) employed EEG-based deep learning classification models, and (3) included DL-based design strategies to improve feature extraction. Surveys and studies lacking methodological detail were excluded at this stage.

Figure 1.

Workflow model of our methodology.

Figure 1.

Workflow model of our methodology.

2.3. Inclusion

The full-text assessment resulted in 114 papers that we kept for an in-depth analysis. Instead of applying inclusion/exclusion rules typical of systematic reviews, we organized the studies based on their methodological focus. The papers were categorized as follows: (1) 40 papers on CNN-based EEG classification, (2) 15 papers on Transformer-based EEG classification, (3) 22 papers on CNN–Transformer hybrid architectures, (4) 11 papers using miscellaneous deep learning approaches, and (5) 26 surveys on EEG-based classification.

2.4. Analysis

For each study, input representations, feature extraction techniques, network architectures, and reported performance and efficiency metrics were extracted and compared to identify trends, strengths, and challenges in the field. This structured grouping allowed us to perform a fair comparison of DL strategies without imposing the constraints of a formal systematic review protocol.

3. Related Work

3.1. Background

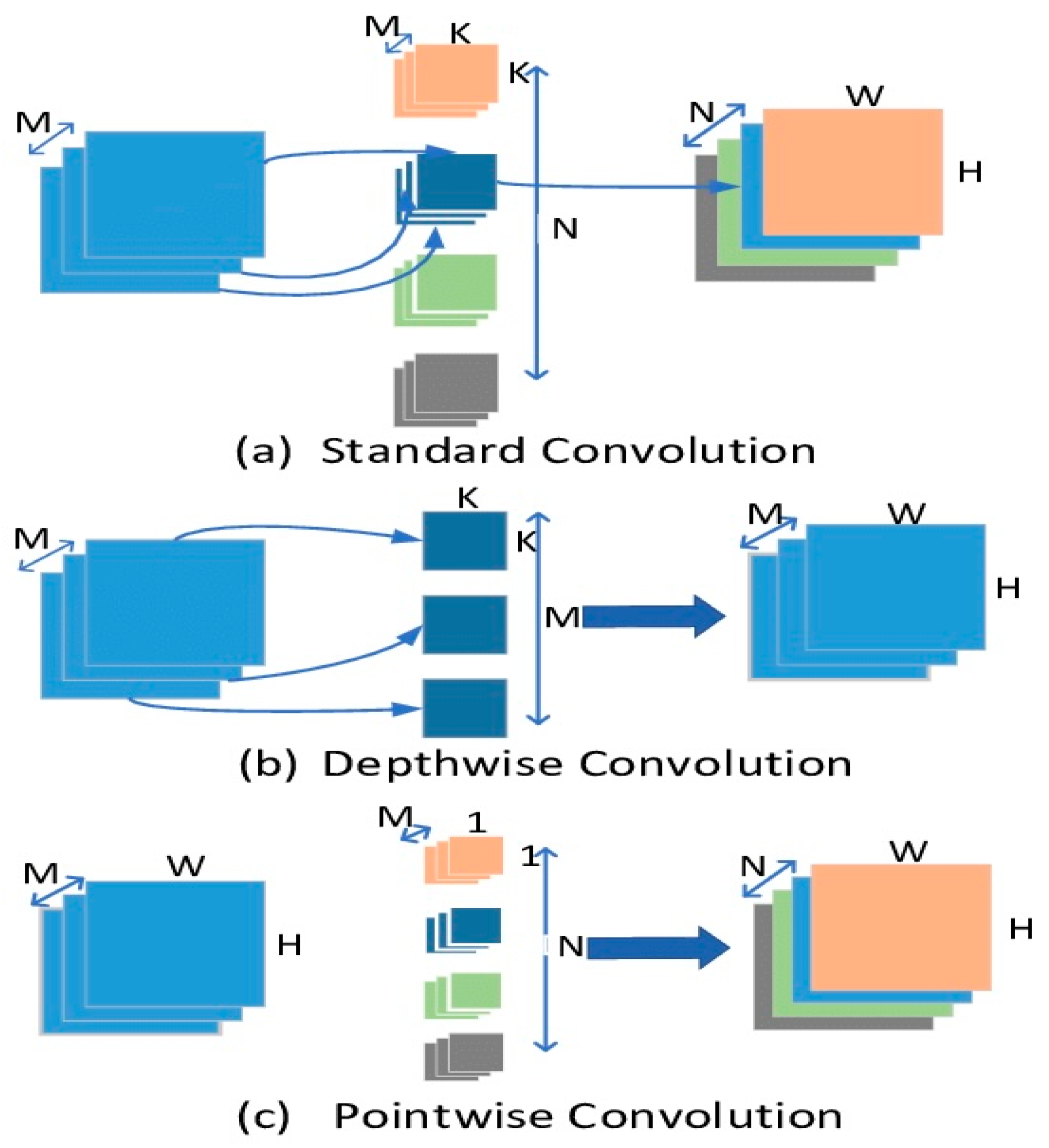

CNNs are DL models that can automatically extract patterns from grid-structured data. The core convolution in CNNs relies on shared weights across an image [15]. Many concepts have been developed to enhance FE, and many important CNN models have emerged: VGGNet, emphasizing a simple but deep design for hierarchical feature learning [16]; Inception networks, with parallel modules capturing multiscale features [17]; ResNet, enabling deeper networks through residual connections [18]; DenseNet, improving the learning efficiency by connecting all layers [19]; MobileNet, creating lightweight networks for mobile devices [20]; EfficientNet, balancing Acc. and efficiency through smart scaling [21]; RegNet, focusing on scalable network design [22]; and ConvNeXt, modernizing CNNs with Transformer updates while keeping them suitable for resource-limited applications [23].

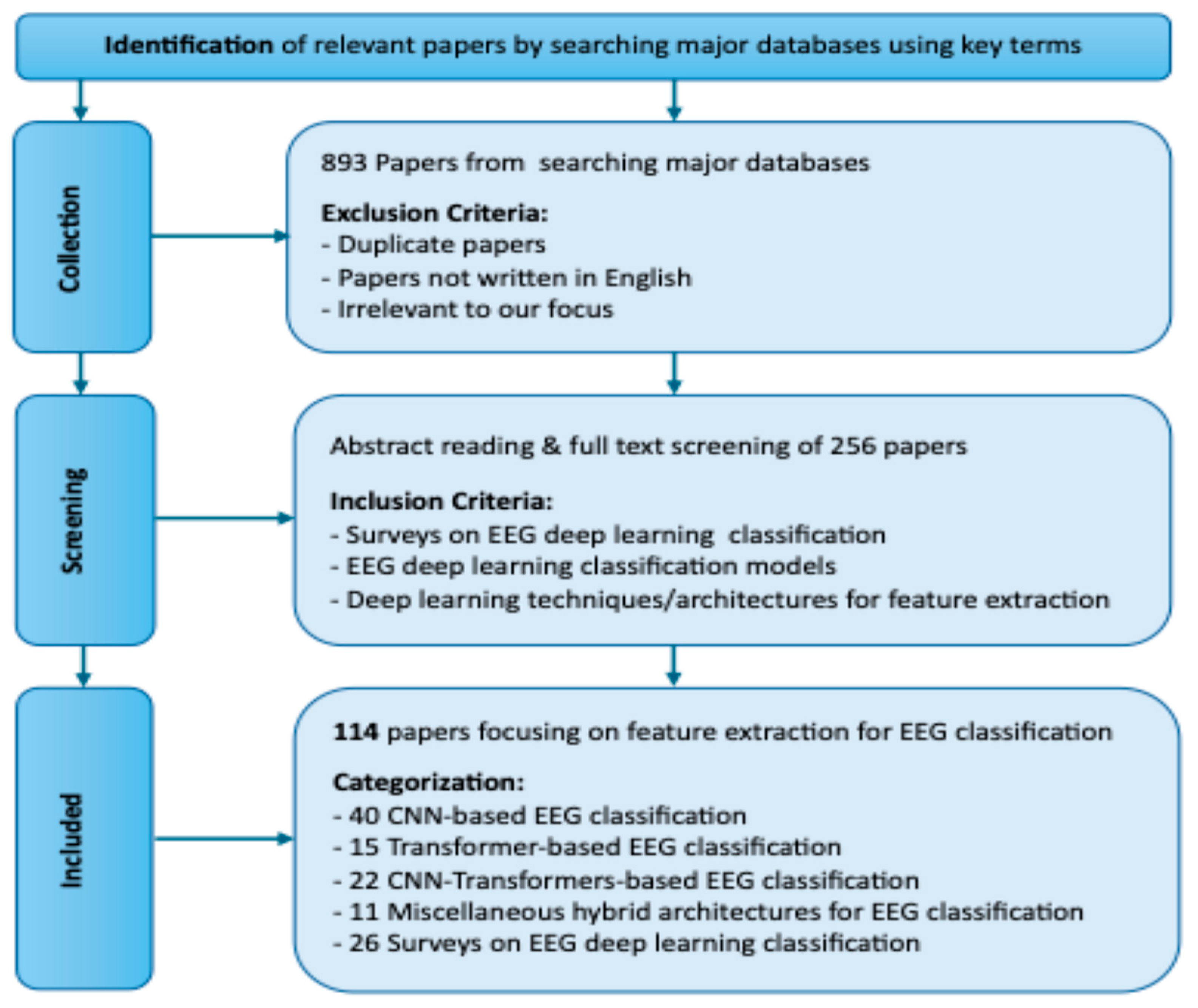

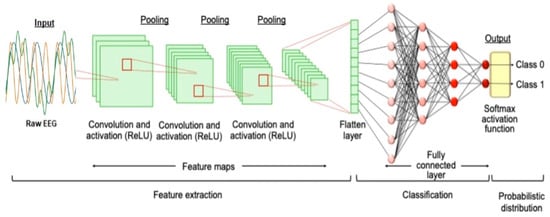

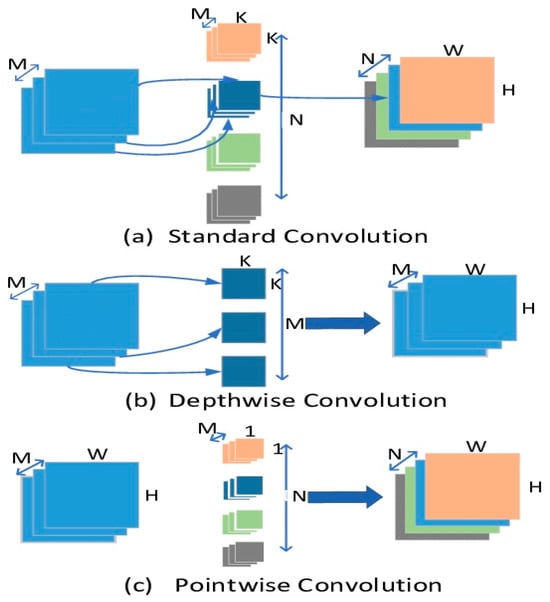

CNNs have been used for EEG classification tasks due to their built-in spatial biases, which allow them to learn from proximity and locality relationships (Figure 2). They learn features from raw data, forming complex representations layer by layer [15]. This makes them suitable when EEG signals are converted into image-like formats such as spectrograms or scalograms (Figure 3). Common 2D array formats are [channels × time], [channels × frequency], or [frequency/scales × time]. Initial layers learn basic waveforms or frequency bands and deeper layers extract intricate spatiotemporal relationships across channels and time steps [24].

Figure 2.

EEG analysis using a fundamental CNN structure. Adapted from Takahashi et al., 2024. Comparison of Vision Transformers and Convolutional Neural Networks in Medical Image Analysis: A Systematic Review, J Med Syst, 48 (1), 84 [9], licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0). The original figure was modified by replacing the MRI input image with an EEG input representation; all other elements remain unchanged.

Figure 3.

Different image-like input representations for EEG data.

CNNs efficiently recognize spatial patterns across EEG electrodes, where nearby signals reflect related brain activity [21]. They also offer translation invariance, detecting features that appear at slightly different times or forms [25]. This allows them to generalize across trials and subjects despite signal variability [25,26]. Their low computational overhead also makes them practical for real-time systems with limited processing power, like wearable EEG headsets or embedded systems [26]. CNNs still have limitations for EEG despite these strengths. The use of fixed convolutional filters limits CNNs’ flexibility in modeling event-related potential (ERP) signals, which vary in length or timing [27]—for instance, late ERP components like P600, which occurs hundreds of milliseconds after a stimulus [27]. Thus, CNNs’ limited temporal receptive fields mean that they may struggle to model the global temporal context that describes how brain activity evolves over long periods [28].

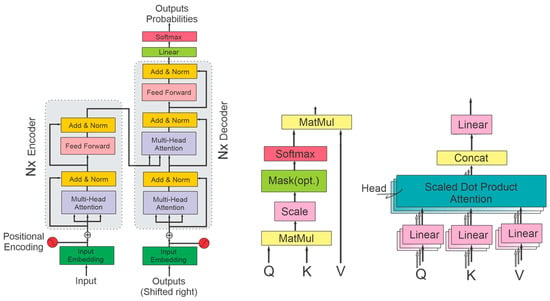

The Transformer architecture (Figure 4) was initially proposed for natural language processing (NLP). It replaces recurrence in traditional RNNs and LSTM with self-attention (SA) to improve the scalability. It is a seq2seq model with an encoder and a decoder composed of identical layers. Encoder layers consist of multihead SA and feedforward networks with residual connections, followed by normalization. Decoder layers add a cross-attention module between the SA and feedforward blocks and modify SA to prevent access to future positions [13,29,30]. In 2018, GPT showed that Transformers could extract features for coherent text generation [31]. In 2019, BERT introduced bidirectional attention to improve language understanding [32]. In 2020, T5 reframed NLP tasks under a text-to-text setup to unify FE [33]. In 2021, Vision Transformer (ViT) surpassed CNNs by extending FE to images [34]. In 2022, PaLM scaled FE for stronger reasoning and generalization [35]. In 2023, LLaMA optimized FE for smaller models [36]. In 2024, DeepMind’s Gemini integrated vision and language features in a single model [37]. Today, Transformers continue to advance FE across language, vision, audio, and multiagent reasoning.

Figure 4.

Transformer architecture: from left to right, encoder–decoder, attention mechanism, multihead attention [13,29,30]. Reproduced from Vafaei and Hosseini, 2025. Transformers in EEG Analysis: A Review of Architectures and Applications in Motor Imagery, Seizure, and Emotion Classification, Sensors, 25 (5), 1293 [13], licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0).

Transformers have been adopted in EEG applications due to their ability to model long-term dependencies in data via SA mechanisms [34,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. The SA mechanism computes pairwise attention between all input positions. Unlike CNNs, which focus on local patterns, Transformers detect relationships across long time periods or between distant brain regions [13]. This is critical in EEG tasks like identifying late ERPs that appear seconds from earlier signals but are semantically correlated. Transformers offer several benefits for EEG analysis. First, their global temporal modeling allows them to track complex EEG/ERP components spanning long periods [39,42,45]. This ability makes them suitable for cognitive or emotional states where brain activity is less time-locked. Their attention weights indicate relevant signal segments for better interpretability [45,46]. In addition, their dynamic receptive fields allow them to adapt to variable timing across users or trials without relying on fixed filters, like CNNs [45,46]. Despite their potential, Transformers face challenges in EEG. They lack built-in spatial or temporal biases, so they must learn these relationships from data, which is difficult with small or noisy datasets [39,42,45]. Their quadratic time and memory complexity also makes them computationally expensive for long recordings [42,44]. Lastly, Transformers need careful regularization since they are prone to overfitting on limited or highly variable EEG data [42,45].

3.2. Recent Reviews

Many surveys have focused on broad and comparative reviews by systematically assessing ML and DL methods for EEG classification across diverse domains. Roy et al. [8] reviewed 154 DL studies published during 2010–2018 about epilepsy, sleep, BCIs, and cognitive research. They reported CNNs as the most common architectures, with a 5.4% Acc. improvement over traditional methods. This was followed by about half of the studies focusing on RNNs, which used raw or preprocessed EEG time series. They pointed out reproducibility issues caused by limited access to open datasets and code, and they recommended standards for experimental reporting. Craik et al. [2] also surveyed 90 DL studies on emotion recognition (ER), MI, seizure detection, mental workload, sleep stage scoring, and ERP detection. They found that CNNs, RNNs, and deep belief networks (DBNs) repeatedly outperformed conventional shallow classifiers. A workflow diagram to guide input selection and hyperparameter tuning was provided. Saeidi et al. [47] expanded on this and mapped preprocessing, FE, and classification pipelines across supervised ML and DL methods. Their work emphasized the rapid adoption of DL methods, while classic ML methods remain relevant. They created a catalog for common feature choices and listed the persistent standardization and reproducibility gaps. Li et al. [48] framed EEG classification in broader psychological and physiological contexts, clarifying conceptual pathways for research. Prabowo et al. [49] and Vempati and Sharma [50] summarized recent DL models, covering theoretical foundations and technical methods. They pointed out improvements in performance across EEG tasks. More recent studies, including those of Mohammed et al. [51] and Gatfan [52], provide comparative analyses across EEG applications. Mohammed et al. [51] presented an overview of CNNs, RNNs, Transformers, and hybrid approaches. The dominance of hybrid and DL alongside classical ML pipelines as a result of the transformative efficacy of both domains was noted. Gatfan [52] compared ML and DL methods for disease diagnosis and brain behavior analysis. They showed that DL (especially CNNs) outperformed traditional ML, which often requires combining multiple algorithms to achieve similar Acc.. These surveys point out the continuing need for methodological rigor and reproducibility.

Other authors have focused on application-specific reviews. EEG-based ER has been a prominent application area. Suhaimi et al. [53] reviewed studies from 2016 to 2019. They examined how emotions were evoked, the sample sizes used, and the EEG hardware and ML techniques. Their review pointed out virtual reality (VR) as an emerging method to deliver emotional stimuli. Rahman et al. [54] combined theoretical foundations with practical EEG-based ER techniques, detailing common emotion theories, FE methods, and classification strategies. Khare et al. [55] analyzed 142 multimodal studies that combined EEG with ECG, GSR, eye tracking, speech, and facial cues. Emotion models, datasets, and key challenges like variable signal lengths, a lack of trust in model outputs, and limited real-time support were reviewed. Jafari et al. [56] focused on real-time DL applications and their feasibility. They discussed hardware-focused solutions like system-on-chip (SoC), field-programmable gate array (FPGA), and application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) implementations and provided a comprehensive examination of technical advances. Ma et al. [57] distinguished subject-dependent and subject-independent DL models, clarifying pathways for personalized and large-scale ER. Using a PRISMA review of 64 DL studies, Gkintoni et al. [58] reported that multimodal approaches can achieve Acc. above 90% and emphasized dataset variety. They recommended adaptive models and standardized protocols. MI EEG and BCIs have also been the focus of many researchers. Al-Saegh et al. [59] reviewed DL approaches and their input representations. They summarized preprocessing and architectural strategies that yield strong MI BCI performance. Ko et al. [60] surveyed techniques to reduce the BCI calibration time, pointing out generative data augmentation and explicit transfer learning as promising avenues. Pawan et al. [61] compiled over 220 ML-based BCI studies, offering practical guidance from acquisition to classification. Saibene et al. [62] emphasized benchmarking and wearable technology integration. Recent contributions have also addressed clinical translation. Moreno-Castelblanco et al. [63] reviewed lower-limb MI in neurorehabilitation, underlining multimodal fusion, minimal channels, and portable BCI designs to improve accessibility and usability. Wang et al. [64] compared 13 DL models, offering practical ablation-based architectural design recommendations. They showed that multistream CNNs with LSTM and spatial features enhance performance, while fully connected layers increase the complexity (Complex.) without improving Acc. Cognitive workload and neuropsychology are other areas of focus. Hassan et al. [65] conducted a PRISMA review of cognitive workload estimation. SVMs and DL models were reported as the most dominant techniques. They suggested that, to translate lab findings into deployable systems, multimodal dataset integration, standard testing protocols, and real-world validation are a necessity. Bardeci et al. [66] assessed CNNs and LSTM in psychiatric EEG, stressing the weak reporting of clinical features, flawed validation, and non-independent test data. They provided recommendations to improve the methodological rigor. Others have surveyed specific contexts. Nwagu et al. [67] reviewed EEG in immersive environments by analyzing BCIs in virtual and augmented reality (AR). They focused on techniques like steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP) with AR for control and MI with VR for rehabilitation. Discomfort and low information transfer rates were noted as challenges. Dadebayev et al. [68] compared consumer-grade EEG devices to research-grade equipment. They revealed limitations in data quality and classification performance when using commercial headsets as practical challenges in applied research.

Other reviews have examined DL architectures for EEG. Klepl et al. [69] surveyed graph neural networks (GNNs) for ER, MI, and neurological diagnosis tasks. They cataloged design patterns, including graph construction and node and edge features. Spectral graph convolutions were found to be more prevalent than spatial ones. The review suggested transfer learning and cross-frequency modeling as future directions. Vafaei and Hosseini [13] reviewed Transformer-based EEG models. They categorized them into time-series (TS), vision, graph attention, and hybrid Transformers and discussed augmentation and transfer learning as solutions for data scarcity.

Several studies have emphasized methodological shortcomings in EEG research. Bardeci et al. [66] highlighted weak clinical rigor in psychiatric DL EEG studies, calling for stronger reporting and validation. Roy et al. [8] also flagged reproducibility issues due to unavailable data and code. Dadebayev et al. [68] noted reliability concerns with consumer-grade EEG for ER. Wang et al. [64] provided ablation-based evaluations to show which architectural design choices affect performance. They also offered practical recommendations. Table 1 sums up these reviews and their contributions.

Table 1.

Recent surveys on EEG-based classification.

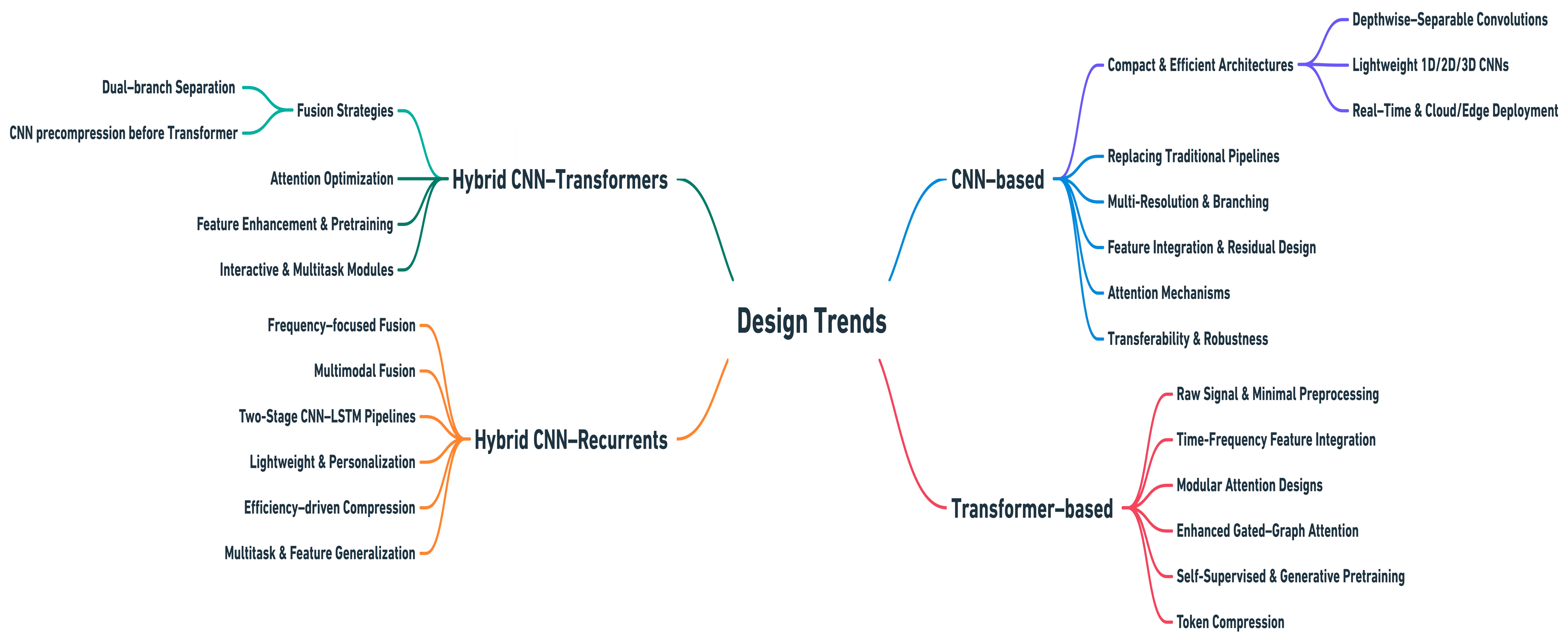

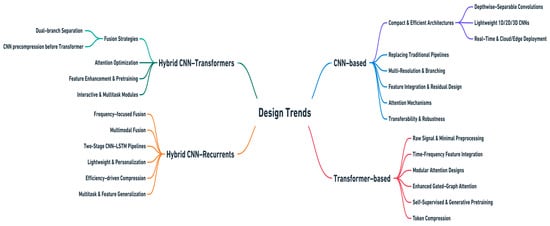

3.3. Study Scope

It is important to note that our analysis of prior surveys is limited to their thematic scopes and findings to identify gaps within the literature. We did not perform a formal methodological quality or risk-of-bias assessment of the review papers, as our objective was the comparative evaluation of EEG-based DL models. Despite the growth of DL in EEG-based classification, most reviews focus on either broad architectural comparisons [8,13,51,69] or pipelines for specific applications, mainly ER, MI, and cognitive workload [53,59,65]. While these surveys examine Acc. trends and design choices, they do not explain the role of FE and its effects on both performance and efficiency. Only a few studies [54,59,61] have compared FE strategies across models or tasks, leaving gaps for researchers seeking efficient and generalizable pipelines. In this review, we address this gap by providing a comparative analysis of FE methods for EEG-based classification across CNNs, RNNs, Transformers, and hybrid architectures. Different from earlier reviews, this work examines the most recent studies in the field, with particular attention to their network architectures, FE strategies, computational efficiency, and performance outcomes. The studies were categorized by model type to identify common architectural patterns and variations in FE approaches. Special focus was placed on how design choices, such as feature fusion, input representation, and regularization methods, influence classification performance and system efficiency. This efficiency-driven comparative review shifts the focus from performance comparisons to deployment evaluations, which have not been addressed in prior EEG DL surveys. The aim is to draw out practical insights that can guide both researchers and applied system developers.

4. Feature Extraction for EEG-Based Classification

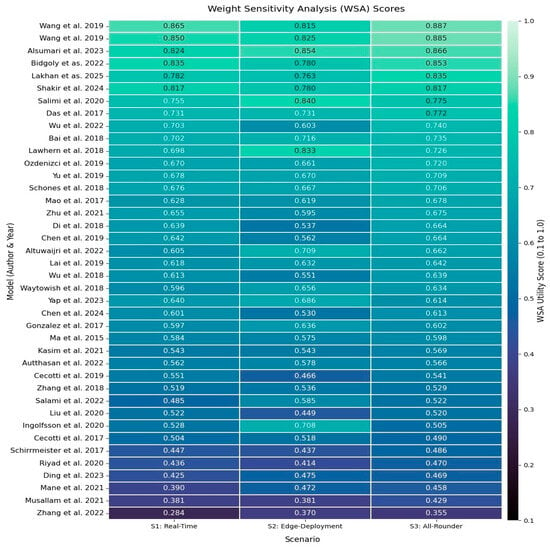

4.1. Efficiency in CNN-Based Models

Efficient FE aims to boost the classification performance (Acc., robustness) while reducing the overall cost (fewer parameters, fast inference, simple models). Over the past decade, many studies (Table 2) have proposed CNN architectures to improve the efficiency of EEG FE. In this section, we analyze a selection of studies to show how each approach enhances FE and impacts both performance and efficiency. Most works focus on EEG-based biometric mechanisms to address traditional challenges. For clarity, we group the studies by their main methodological focus, although overlap across categories exists.

4.1.1. Applications to Raw EEG

Initial studies of CNNs showed that temporal and spatial features could be directly extracted from minimally preprocessed signals, eliminating the need for manually engineered features. The work by Ma et al. [70] showed that CNNs could automatically extract useful patterns from raw resting-state EEG signals and create reliable “brain fingerprints” to identify individuals. Their end-to-end pipeline was jointly optimized using gradient descent. It uses two convolutional layers to extract invariant temporal patterns, followed by two average pooling layers to reduce the dimensionality and computational cost (Comp. Cost), and ends with a fully connected layer for classification. This approach achieved 88% Acc. in a 10-class identification task and maintained strong results with very low-frequency bands (0–2 Hz) and short temporal segments (<200 ms), reaching 76% Acc. with only 62.5 ms of data. Following this direction, Mao et al. [71] used a CNN to learn discriminative EEG features for person identification. Their pipeline processed raw EEG signals from a large-scale driving fatigue experiment. The CNN architecture utilized three convolutional layers with ReLU and max pooling modules after each, followed by two fully connected layers and a softmax output for classification. This method achieved 97% Acc. from 14,000 testing epochs and was trained in only 0.3 h for over 100 K epochs, outperforming traditional shallow classifiers. Schirrmeister et al. [13] proposed shallow and deep ConvNets for raw EEG decoding. The shallow network, inspired by Filter Bank Common Spatial Patterns (FBCSP), combined temporal convolutions, spatial filtering, squaring nonlinearity, mean pooling, and logarithmic activation to extract band power features. The deep network captured hierarchical spatiotemporal modulations, splitting the first block into temporal and spatial layers for regularization. Cropped training with sliding windows augmented the dataset and reduced overfitting. Although training was slower than for FBCSP, the predictions were efficient. Batch normalization and ELU activation improved its performance. Visualizations revealed meaningful frequency modulation, demonstrating robust decoding and interpretable feature learning. This approach outperformed FBCSP pipelines, achieving higher mean Acc. of 84.0%, compared to 82.1%. Similarly, Schöns et al. [72] presented a deep CNN-based biometric system trained on raw EEG. Recordings were segmented into 12 s overlapping windows to expand the training data. The network, composed of convolution, ReLU activation, pooling, and normalization layers, processed the signals, and classification layers were later discarded. CNN outputs served as compact feature vectors for verification. The system achieved an equal error rate (EER) of 0.19%, with the gamma band providing the most discriminative signal. Sliding-window augmentation and the shallow CNN enabled both scalability and near-perfect identification Acc. Di et al. [73] also proposed a CNN-based EEG biometric identification system. EEG signals were preprocessed and segmented before being input into the network. Temporal convolutions captured frequency patterns, while spatial convolutions modeled correlations across electrodes. Deeper layers extracted subject-specific representations to distinguish individual participants. Zhang et al. [74] designed HDNN and CNN4EEG for EEG-based event classification. HDNN divides EEG epochs into sub-epochs processed by child DNNs with shared weights, boosting the training speed and cutting the memory usage, while improving the Acc. over standard DNNs. CNN4EEG uses custom convolutional filters adapted to EEG’s spatial and temporal structure to effectively capture its spatiotemporal patterns. CNN4EEG outperformed all baselines, achieving 13% higher Acc. than shallow methods, 9% higher than that of a canonical CNN, and 6% higher than that of a DNN. These works demonstrate feasibility, but the systems’ performance depends on large models and extensive training data.

4.1.2. Frequency- and Spectral-Domain Approaches

Further applications have transformed EEG signals into compact representations to highlight spectral discriminants. To adapt CNNs to consumer-grade EEG, González et al. [75] proposed a 1D CNN operating on power spectral density (PSD) estimates computed from 6 s EEG windows with Welch’s method. The PSD inputs offered compact frequency-domain representations, reducing the dimensionality while retaining discriminative information. Convolution and max pooling layers operated like wavelet decomposition by extracting coarse spectral features; combined with downsampling, subsequent layers captured finer temporal–spectral patterns. An inception block further enabled multiscale feature learning. This approach achieved 94% Acc., surpassing SVM baselines and showing that PSD-based CNNs can efficiently extract subject-specific features from low-cost hardware. For SSVEP classification, Waytowich et al. [76] compared traditional FE methods such as canonical correlation analysis (CCA) with the compact EEGNet [12]. The compact CNN extracted frequency, phase, and amplitude features directly from raw EEG. It contrasted CCA, which requires prior knowledge of the stimulus signals and performs well in synchronous paradigms but fails in asynchronous ones. Using temporal convolutions as bandpass filters and depthwise spatial convolutions for spatial filtering, its compact design reduces the parameters and supports training on small datasets. It achieved 80% cross-subject Acc., outperforming traditional methods and demonstrating robust, calibration-free performance for BCI applications. Expanding this line of work, Yu et al. [77] focused on low-frequency SSVEP components (<20 Hz) as discriminative features for user authentication. These signals were marked by high intersubject and low intrasubject variability. They were isolated using a Chebyshev low-pass filter to suppress less informative high-frequency oscillations. For classification, the authors extended Schirrmeister’s shallow ConvNet [13] to a multiclass variant (M-Shallow) by introducing parallel temporal filters and additional layers to improve the scalability without increasing Complexity. Despite its lightweight design of 30 k parameters, it preserved fast training and inference and delivered high Acc. across multiple tasks. This integration yielded 97% cross-day authentication Acc. on eight subjects and shows that shallow architectures can be adapted to complex EEG biometrics with high efficiency. Compared with raw-signal CNNs, frequency-domain CNNs balance interpretability and efficiency by focusing on known neural rhythms. They draw on neuroscience principles to simplify models and enhance their robustness. These models show that embedding spectral knowledge into the network is more effective than increasing its depth.

4.1.3. EEG Representation and Topology Strategies

Other EEG strategies focus on how signals are structured before entering CNNs. They range from spatial electrode mappings to graph-based connectivity encodings to exploit the spatial organization and network properties of brain activity. Lai et al. [78] examined how EEG input representation affects CNN-based biometrics. The matrix of amplitude vs. time presents raw EEG amplitude values in their default channel order. It preserves spatial patterns, minimizes the preparation time, and achieves high identification Acc. Converting data into images introduces slight information loss but reduces storage, proving an acceptable trade-off for handling large datasets. Normalizing energy in an image of energy vs. time stabilizes large power values, simplifies CNN calculations, and improves FE. Rearranging channels by correlation degrades performance by disrupting the 2D spatial patterns that are essential for CNN feature learning. The study shows that CNN performance depends on input data structuring. Wang et al. [79] represented EEG signals as functional connectivity (FC) graphs generated using the phase locking value (PLV) in the beta and gamma bands, producing fused representations. Applying graph CNNs (GCNNs) to these graphs resulted in higher correct recognition rates (CRRs), robust generalization, reduced training time, and efficient transfer learning. In a related approach, 1D EEG data were converted into 2D layouts and processed with 3D CNNs for the simultaneous extraction of spatial and temporal features. This 3D method outperformed 2D CNNs, reduced the input dimensionality, and captured complex spatiotemporal patterns in ERP classification. Graph-based connectivity methods [80] and 3D convolutional representations [81] extended this further, capturing interchannel relationships and depth. Wang et al. [80] evaluated three EEG biometric methods—RHO + CNN, UniFeatures + CNN, and Raw + CNN—in terms of efficiency and performance. Firstly, RHO + CNN integrates FC with a CNN. The FC module calculates beta-band synchronization using the RHO index to generate 2D maps, which the CNN processes for FE and classification. Training converges in about 10 epochs, and the model achieves a CRR of 99.94% with low equal error rates (EERs). Its success comes from stable identity information in FC. Secondly, UniFeatures + CNN extracts univariate features such as autoregressive (AR) coefficients, fuzzy entropy (FuzzyEn), and PSD. While efficient, it yields lower CRRs and higher EERs in cross-state authentication, due to the state dependence of these features. Lastly, Raw + CNN directly processes raw EEG, requiring around 25 epochs for training and producing the lowest CRRs and highest EERs. It is highly sensitive to mental states, noise, and artifacts, resulting in poor generalization. Overall, RHO + CNN is the fastest, most accurate, and robust method, effectively handling mental state variabilities. Zhang et al. [81] applied 3D convolution to high-density EEG by modeling the electrode layout as a 2D grid with time as a third dimension to jointly learn scalp topology-aware spatial filters and temporal dynamics. The model’s computation was optimized through kernel and dimensionality choices. It outperformed 2D CNNs in tasks using spatial patterns like frontal–occipital activity and achieved strong results in ER and seizure detection. These representation strategies emphasize spatial locality and generalize better across cognitive tasks in comparison with frequency-based models.

4.1.4. ERP- and VEP-Based CNN Models

In contrast to continuous EEG, discrete approaches leverage stimulus-locked potentials as discriminative signatures, embedding spatial and temporal filtering directly into CNN architectures. Das et al. [82] investigated visual evoked potentials (VEPs) as stable biometric signatures. Data from 40 subjects across two sessions underwent preprocessing, including common average referencing (CAR), bandpass filtering, downsampling, z-score normalization, and detrending, before generating averaged VEP templates. Template averaging enhanced the signal-to-noise ratio and reduced the input dimensionality for efficient training. These inputs were processed by stacked convolutional and max pooling layers to extract spatiotemporal features and improve the robustness to subject variability. The system achieved 98.8% rank-1 identification Acc. and strong temporal stability across sessions performed a week apart. Cecotti et al. [83] conducted a systematic evaluation of CNN architectures of varying depth for single-trial ERP detection. They showed that well-designed CNNs can efficiently extract discriminative ERP features with minimal preprocessing. Integrating convolutional spatial filtering and shift-invariant temporal convolution achieved an average area under the curve (AUC) of 0.905 across subjects, while weight sharing reduced the parameters and accelerated training. Training multisubject classifiers eliminated subject-specific calibration and enhanced the efficiency and practicality of ERP-based BCI systems. Although the initial training was computationally intensive, the resulting models offered robustness and scalability beyond traditional linear methods. Extending this work, Cecotti et al. [84] evaluated 1D, 2D, and 3D CNNs for single-trial ERP detection. They introduced a volumetric representation by remapping 64 EEG sensors into a 2D scalp layout and adding time as a third dimension. These multidimensional convolutions simultaneously captured robust spatiotemporal features, improved generalization, and reduced the sensitivity to subject variability. The best 3D CNN required fewer inputs and achieved a mean AUC of 0.928, demonstrating superior efficiency and scalability. Chen et al. [85] proposed the Global Spatial and Local Temporal Filter CNN (GSLT-CNN). It integrates global spatial convolutions, which capture interchannel dependencies, with local temporal convolutions that extract fine dynamics. Trained directly on raw EEG signals, it achieved 96% Acc. across 157 subjects and up to 99% in rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP)-based cross-session tasks. The model was trained with 279,000 epochs in under 30 m, while remaining lightweight, robust, and highly adaptable. This demonstrates strong potential for EEG biometrics and broader BCI applications. These studies show how CNNs can be adapted to task-specific temporal alignments, in contrast to generic time–frequency approaches.

4.1.5. Multiscale and Temporal Modeling Strategies

Other strategies have expanded the receptive fields and decomposed EEG into finer sub-bands. This allows CNNs to capture both short- and long-range dynamics efficiently. Salami et al. [86] introduced EEG-ITNet, an Inception-based temporal CNN, for efficient MI classification in BCI systems. FE was performed through inception modules and causal convolutions with dilation. These modules separated multichannel EEG into informative sub-bands using parallel convolutional layers with different kernel sizes. Depthwise convolutions combined electrode information. The temporal convolution block employed dilated causal convolutions in residual layers to increase the receptive field. This hierarchical design efficiently integrated spectral, spatial, and temporal information with fewer parameters and enhanced interpretability comparable to other architectures. EEG-ITNet achieved 76.74% mean Acc. in within-subject and 78.74% in cross-subject scenarios and also generalized well on the OpenBMI dataset. Bai et al. [87] leveraged temporal convolutional networks (TCNs), which apply causal and dilated convolutions to efficiently capture long-range temporal features from sequential EEG data. Dilated convolutions enabled exponentially expanding receptive fields that could model dependencies far into the past, while residual connections stabilized the training and architecture depth. TCNs processed sequences in parallel to avoid the bottlenecks of recurrent networks, reduce memory usage during training, and allow faster inference. Compared to LSTM and generative recurrent units (GRUs), TCNs delivered superior performance across tasks. They improved FE and the predictive Acc., making TCNs a scalable and powerful alternative for EEG sequence modeling. For MI decoding in BCIs, Riyad et al. [88] introduced Incep-EEGNet, a deep ConvNet architecture. The pipeline processed raw EEG signals through bandpass filtering and trial segmentation before end-to-end FE and classification. Incep-EEGNet applied filters similar to EEGNet [12], followed by an Inception block. This block integrated parallel branches with varying convolutional kernels, pointwise convolution, and average pooling to extract richer temporal features. Depthwise convolution reduced the Comp. Cost, while pointwise convolution served as a residual connection. The model achieved 74.07% Acc. and a kappa of 0.654, outperforming traditional methods. Liu et al. [89] also proposed a parallel spatiotemporal self-attention CNN for four-class MI classification. The spatial module assigns higher weights to motor-relevant channels and reduces artifacts. The temporal module emphasizes MI-relevant sampling points and encodes continuous temporal changes. The model achieved 78.51% Acc. for intrasubject and 74.07% for intersubject classification. This lightweight design supports real-time BCI applications and outperformed both traditional and DL models. Multiscale strategies were further refined by Zhu et al. [90] in RAMST-CNN, a residual and multiscale spatiotemporal convolutional network for EEG-based personal identification. The model combined residual connections, multiscale grouping convolutions, global average pooling, and batch normalization. Parallel convolutions extracted both coarse and fine temporal patterns, while residual links facilitated gradient flow. Despite being lightweight, RAMST-CNN achieved 99.96% Acc. Similarly, Lakhan et al. [91] introduced a broadband network. It processes multiple EEG frequency bands in parallel through convolution branches tailored to distinct ranges. By integrating multiband FE into a single model, it achieved higher Acc. than single-band approaches. It maintained lower parameter counts than training separate models for each band. Ding et al. [92] introduced Tsception, a multiscale CNN for ER from raw EEG. It consisted of three layers: a dynamic temporal layer, an asymmetric spatial layer, and a high-level fusion layer. The temporal layer used 1D kernels of varying lengths scaled to the EEG sampling rate to capture both long-term low-frequency and short-term high-frequency dynamics. The spatial layer used global and hemisphere-specific kernels to exploit EEG asymmetry and model interhemispheric relationships. Features were then integrated by the fusion layer for classification. Tsception achieved higher Acc. and F1 scores than other methods while remaining compact with fewer parameters, supporting online BCI use. These approaches trade off efficiency for robustness. They capture dynamic EEG patterns beyond fixed time windows, situating them between raw CNNs and sequential models.

4.1.6. Compact and Lightweight Architectures

Further CNN approaches prioritize efficiency by reducing the parameter counts to improve their distinctive power. A key milestone was given by Lawhern et al. [12], who introduced EEGNet, a compact CNN for general-purpose BCI applications. The network processed raw EEG trials directly, using temporal convolutions for frequency filters, depthwise convolutions for spatial patterns, and a separable convolution to summarize temporal dynamics. This design performed well with limited data and no augmentation. EEGNet’s efficiency and interpretable features made it robust and practical for both ERP- and oscillatory-based BCIs. Subsequent variants [93,94] optimized EEGNet [12]. Salimi et al. [93] applied EEGNet [12] to extract cognitive signatures for biometric identification. They combined the N-back task cognitive protocol with an optimized EEGNet model to elicit and capture robust EEG patterns. This approach reduced the recording time and Comp. Cost. Using single EEG segments of only 1.1 s, the lightweight network achieved up to 99% identification Acc. Ingolfsson et al. [94] also developed an EEGNet [12] and TCN-based [87] model optimized for edge devices. EEG-TCNet used temporal convolutions with depthwise separable filters and dilation to capture EEG dynamics. It had only 4272 parameters and 6.8 M multiply–accumulate operations (MACs) per inference, but it achieved 83.8% Acc. on four-class MI, matching larger networks. Its low memory and compute footprint supports real-time on-device BCI processing, indicating that high Acc. is achievable with very few parameters. The model also generalized well across 12 datasets, surpassing prior results on the MOABB benchmark. Similarly, Kasim et al. [95] showed that even simple 1D CNNs could achieve competitive performance with minimal parameter counts. Their model extracted temporal features from each EEG channel using small convolution kernels, fused them efficiently, and avoided 2D operations, resulting in a lightweight network with only 10 K parameters. It matched the Acc. of more complex models in ER and MI tasks while being faster and easier to train. Lightweight convolutional strategies continued with Wu et al. [96]. They introduced MixConv CNNs by embedding varying convolution kernels within each layer to emulate an FBCSP approach. Different kernel lengths targeted frequency bands from delta to gamma to allow simultaneous temporal filtering. Mixed-FBCNet used 0.45 M parameters and only 10 EEG channels yet achieved high Acc. and low EERs. Building on this compactness, Altuwaijri et al. [97] developed a multibranch CNN for MI. EEG signals were split into three branches, processed by EEGNet [12] modules, and recombined using squeeze and excitation (SE) attention blocks, which reweighted features to improve the discriminability and efficiency. This compact architecture achieved 70% Acc. on challenging four-class MI tasks, outperforming the single-branch EEGNet [12]. Autthasan et al. [98] proposed MIN2Net, a multitask learning model for subject-independent MI EEG classification, to eliminate calibration for new users. EEG signals were bandpass-filtered and encoded into latent vectors by a multitask autoencoder. Deep metric learning (DML) with triplet loss refined these embeddings by clustering same-class samples and separating different-class samples, and a supervised classifier performed the final prediction. This design reduced preprocessing and kept the model small. MIN2Net improved the F1 score by 6.7% on SMR-BCI and 2.2% on OpenBMI, with ablation studies confirming the contribution of the DML module. Latent feature visualizations showed clearer feature clustering than baselines, and its consistent performance across binary and multiclass tasks demonstrates its suitability for calibration-free online BCI applications. Bidgoly et al. [99] used Siamese and triplet CNNs for EEG biometrics. Their model learned compact embeddings of EEG segments for subject matching, rather than multiclass classification. This approach avoided large output layers, ensuring scalability as the number of subjects increased, and achieved a 98.04% CRR with a 1.96% error rate on 105 subjects from the PhysioNet EEG dataset. Alsumari et al. [100] also studied EEG-based identification under controlled recording conditions as a matching task between distinct brain states (open vs. closed eyes). Using a CNN to differentiate individuals, their approach achieved a 99.05% CRR with only a 0.187% error rate on PhysioNet. As in the work of Bidgoly et al. [99], the model was compact, with small output layers. The results indicated robust FE for efficient and reliable identification. These studies emphasize deployment and robustness in resource-limited environments. Networks like EEGNet [12] and its variants [93,94] show that, for EEG tasks, efficiency and inductive biases matter more than large architectures. Unlike computer vision, where depth means richer features, EEG’s low SNR and small datasets make shallow models more effective. This is why EEGNet [12] has become a baseline for research and applied settings.

4.1.7. Benchmarking and Next-Generation CNN Designs

Comparative benchmarks highlight trade-offs across CNN families. Recently, Yap et al. [101] benchmarked CNN architectures such as GoogLeNet, InceptionV3, ResNet50/101, DenseNet201, and EfficientNet-B0 for EEG-based classification. EEG signals were converted to time–frequency images as input to these networks. They found that these CNNs could achieve high Acc. on EEG tasks, although trade-offs exist between model complexity and speed. EfficientNet-B0 matched the Acc. of deeper models while using fewer parameters, making it faster. ResNet101 and DenseNet201 offered only slight Acc. gains at the cost of a higher Comp. Cost and memory. The study concluded that balancing performance with computational efficiency is crucial and highlighted the potential of lightweight transfer learning for EEG. Chen et al. [102] introduced EEGNeX, a novel CNN that leverages the latest DL advances. The model combines expanded receptive fields, attention mechanisms, depthwise convolutions, bottleneck layers, residual connections, and optimized convolutional blocks to enhance spatiotemporal FE in EEG signals. As with EEGNet [12] and prior lightweight models, this model achieved high Acc. across multiple EEG classification tasks. Shakir et al. [103] proposed a CNN-based EEG authentication system with three convolutional layers, max pooling, two ReLU-activated dense layers, dropout, and a softmax output optimized using root mean square propagation (RMSprop). Feature selection used Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization (GSO) to identify three key channels (Oz, T7, Cz). For FE, the CNN was a “fingerprint model”, with the penultimate layer’s vectors compared against stored templates using cosine similarity (CS). Supporting both single-task and multitask FE, the system’s Acc. improved from 71% to 95% after optimizing the final dense layer to 30 neurons. This makes it a robust approach for practical EEG authentication. These works illustrate that simplified vision architectures can be adapted for EEG. This reinforces that EEG benefits from shallow designs rather than from scaled ones.

4.1.8. Fusion and Hybrid Feature Extraction Strategies

Beyond unimodal pipelines, fusion strategies integrate complementary FE pathways, like spatial, temporal, spectral, or multimodal information, for improved robustness and efficiency. Wu et al. [104] fused EEG with blinking features for multitask authentication. Using an RSVP paradigm, the system evoked stable EEG and electrooculography (EOG) signals. Hierarchical EEG features were extracted by selecting discriminative channels and time intervals via pointwise biserial correlation, averaging, and forming spatiotemporal maps for a CNN. Blinking signals were processed into time-domain morphological features through a backpropagation network. The two modalities were fused at the decision level using least squares, achieving 97.6% Acc. Subsampling and weight sharing ensured computational efficiency. Özdenizci et al. [105] incorporated adversarial training into CNN FE by adding an auxiliary domain discriminator to enforce subject-invariant EEG features. This approach reduced the need for calibration and improved cross-subject generalization, with only minor computational overhead. Musallam et al. [106] advanced hybrid feature fusion by introducing TCNet-Fusion, an enhanced version of EEG-TCNet [94] with a fusion layer combining features from multiple depths. Shallow outputs from an initial EEGNet [12] module were concatenated with a TCN [87] deep temporal features. This multilevel fusion improved the MI classification Acc. compared to the base EEG-TCNet [94] while adding a negligible Comp. Cost. The model was small due to the efficiency of EEGNet [12] and the TCN [87]. Mane et al. [107] introduced FBCNet, a CNN designed to handle limited training data, noise, and multivariate EEG for MI classification in BCIs. The network processed raw EEG through multiview spectral filtering and isolated MI-relevant frequency bands. The spatial convolution block captured discriminative spatial patterns for each band. The variance layer extracted temporal features by computing the variance in non-overlapping windows, emphasizing ERD/ERS-related activity. These strategies simplified the processing of complex EEG, enhanced the robustness, and reduced overfitting. The compact FBCNet performed well across diverse MI datasets, including stroke patients. These implementations show CNNs’ flexibility, transitioning from standalone classifiers to modular components in multimodal or sequential pipelines. They function as efficient feature extractors when paired with TCNs or RNNs or integrated into adversarial/fusion strategies.

4.1.9. Cross-Integration Overlaps

Compact CNNs [12,93] also process raw EEG inputs (Section 4.1.1); we classify them as compact designs (Section 4.1.6) to emphasize their efficiency contributions rather than input modalities. Other compact CNNs [94,95,96] also adopt spectral representations (Section 4.1.2). We also categorize these as compact designs (Section 4.1.6), since architectural parsimony is their primary focus. Some methods [78,79] combine frequency decomposition (Section 4.1.2) with topological electrode mapping. We discuss them in Section 4.1.3, since spatial encoding is their focus. Temporal CNNs [88,90,92] are also hybrid architectures that incorporate sequential models. We include them in Section 4.1.5 to emphasize their CNN-specific contributions, while broader hybridization is covered in Section 4.1.8. Benchmark studies [101,102] include compact and deeper architectures. We discuss them under benchmarking Section 4.1.7 to highlight comparative findings, rather than compactness (Section 4.1.6). Table 2 below presents a chronological overview of the studies.

Table 2.

CNN-based architectures for EEG classification.

Table 2.

CNN-based architectures for EEG classification.

| Ref. | Author/Year | Model | Protocol | Samples | Channels | Inspiration Basis | Acc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [70] | Ma et al. 2015 | CNN-based | Resting | 10 | 64 | CNN | 88.00 |

| [71] | Mao et al. 2017 | CNN-based | VAT | 100 | 64 | CNN | 97.00 |

| [75] | Gonzalez et al. 2017 | ES1D | AVEPs | 23 | 16 | 1D CNN [Inception] | 94.01 |

| [82] | Das et al. 2017 | CNN-based | MI, VEPs | 40 | 17 | CNN | 98.80 |

| [83] | Cecotti et al. 2017 | CNN1-6 | RSVP | 16 | 64 | CNN | 83.10–90.50 |

| [11] | Schirrmeister et al. 2017 | ConvNets | MI | 9/54 | 22/54/3 | ResNet, Deep/Shallow ConvNet | 81.00–85.20 |

| [87] | Bai et al. 2018 | TCN | CNN | 97.20–99.00 | |||

| [12] | Lawhern et al. 2018 | EEGNet | ERPs, ERN, SMR, MRCP | 15/26/13/9 | 64/56/22 | CNN | 0.91 [AUC] |

| [104] | Wu et al. 2018 | CNN-based | RSVP | 10/15 | 16 | CNN | 97.60 |

| [72] | Schons et al. 2018 | CNN-based | Resting | 109 | 64 | CNN | 99.00 |

| [73] | Di et al. 2018 | CNN-based | ERPs | 33 | 64 | CNN | 99.30–99.90 |

| [74] | Zhang et al. 2018 | HDNN/CNN4EEG | RSVP | 15 | 64 | CNN | 89.00 |

| [76] | Waytowich et al. 2018 | Compact EEGNet | SSVEP | 10 | 8 | EEGNet | 80.00 |

| [78] | Lai et al. 2019 | CNN-based | Resting | 10 | 64 | CNN | 83.21/79.08 |

| [85] | Chen et al. 2019 | GSLT-CNN | ERPs, RSVP | 10/32/157 | 28/64 | CNN | 97.06 |

| [79] | Wang et al. 2019 | CNN-based | SSVEP | 10 | 8 | CNN | 99.73 |

| [77] | Yu et al. 2019 | M-Shallow ConvNet | SSVEP | 8 | 9 | CNN | 96.78 |

| [84] | Cecotti et al. 2019 | 1/2/3D CNN | RSVP | 16 | 64 | CNN | 92.80 |

| [80] | Wang et al. 2019 | CNN-based | Resting | 109/59 | 64/46 | Graph CNN | 99.98/98.96 |

| [105] | Özdenizci et al. 2019 | Adversarial CNN | RSVP | 3/10 | 16 | CNN [Adversarial] | 98.60 |

| [93] | Salimi et al. 2020 | N-Back-EEGNet | N-back | 26 | 28 | EEGNet | 95.00 |

| [94] | Ingolfsson et al. 2020 | EEG-TCNet | MI | 9 | 22 | EEGNet-TCN | 77.35–97.44 |

| [88] | Riyad et al. 2020 | Incep-EEGNet | MI | 9 | 22 | Inception-EEGNet | 74.08 |

| [89] | Liu et al. 2020 | PSTSA-CNN | MI | 9/14 | 22/44 | CNN-S Attention | 74.07–97.68 |

| [95] | Kasim et al. 2021 | 1DCNN | Photic stimuli | 16 | 16 | CNN | 97.17 |

| [90] | Zhu et al. 2021 | RAMST-CNN | MI | 109 | 64 | CNN [ResNet] | 96.49 |

| [106] | Musallam et al., 2021 | TCNet-Fusion | MI | 9/14 | 22/44 | EEG-TCNet | 83.73–94.41 |

| [107] | Mane et al. 2021 | FBCNet | MI | 9/54/37/34 | 22/20/27 | CNN | 74.70–81.11 |

| [86] | Salami et al. 2022 | EEG-ITNet | MI | 54/9 | 20/22 | Inception-TCN | 76.19/78.74 |

| [81] | Zhang et al. 2022 | 3D CNN | VEPs | 70 | 16 | CNN | 82.33 |

| [99] | Bidgoly et al. 2022 | CNN-based | Resting | 109 | 64/32/3 | CNN | 98.04 |

| [96] | Wu et al. 2022 | Mixed-FBCNet | MI | 109/9/10 | 64/22/10 | FBCNet | 98.89–99.48 |

| [97] | Altuwaijri et al. 2022 | MBEEG-SE | MI | 9 | 22 | EEGNet-S Attention | 82.87–96.15 |

| [98] | Autthasan et al. 2022 | MIN2Net | MI | 9/14/54 | 20/15 | AE [CNN] | 72.03/68.81 |

| [92] | Ding et al. 2023 | TSception | EMO | 32/27 | 32/32 | GoogleNet | 61.27/63.75 |

| [100] | Alsumari et al. 2023 | CNN-based | Resting | 109 | 3 | CNN | 99.05 |

| [101] | Yap et al. 2023 | GoogleNet, ResNet, EfficientNet, DenseNet, Inception | ERPs | 30 | 14 | CNN | 80:00 |

| [102] | Chen et al. 2024 | EEGNeX | ERPs, MI, SMR, ERN | 1/54/6/26 | 14/20/22/56 | EEGNet | 78.81–93.81 |

| [103] | Shakir et al. 2024 | STFE/MTFE-R-CNN | MI | 109 | 64 | CNN | 89.00/95.00 |

| [91] | Lakhan et al. 2025 | EEG-BBNet | MI, ERPs, SSVEP | 54 | 62/14/8 | CNN–Graph CNN | 99.26 |

Acc.: Accuracy, AE: Autoencoder, Adversarial: Adversarial CNN, AVEP: Auditory Visual Evoked Potential, Deep/Shallow ConvNet: Deep/Shallow Convolutional Network, EMO: Emotion Protocol, ERN: Error-Related Negativity, ERP: Event-Related Potential, Inception: Inception Variant, MI: Motor Imagery, MRCP: Movement-Related Cortical Potential, MHA: Multihead Attention, N-Back Memory: N-Back Memory Task, Photic Stimuli: Light Stimulation Protocol, ResNet: Residual Neural Network, Resting: Resting State Protocol, RSVP: Rapid Serial Visual Presentation, S Attention: Self-Attention, SMR: Sensory Motor Rhythm, SSVEP: Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential, TN: Tensor Network, T Encoder: Transformer Encoder, VAT: Visual Attention Task, VEPs: Visual Evoked Potential, Y [X]: Indicates that model Y has components from model X.

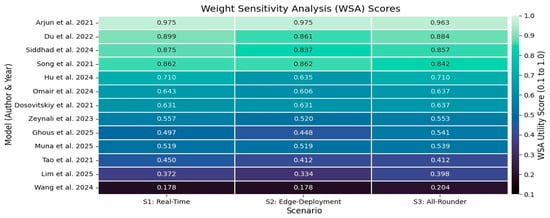

4.2. Efficiency in Transformer-Based Models

Transformers provide a flexible and scalable framework for EEG FE (Table 3). By leveraging SA, they capture complex temporal dynamics, cross-channel spatial relationships, and long-range dependencies. Innovations such as generative pretraining, modular designs, and ensemble strategies enhance their robustness, discriminative power, and computational efficiency. Their ability to process raw signals, integrate multiple feature domains, and adapt across tasks has established them as a versatile tool in EEG analysis.

4.2.1. Applications to Raw EEG

Several studies have focused on Transformers that directly process raw EEG to eliminate manual feature engineering while achieving high Acc. and efficiency. Arjun et al. [38] adapted Vision Transformer (ViT) [34] for EEG ER, comparing CWT-based scalograms with raw multichannel signals. The model used multihead self-attention (MHSA), with the raw-input ViT treating each time window as a patch to capture transient emotional patterns. The raw model outperformed the CWT version, achieving 99% Acc. on DEAP. Shorter windows (6 s) boosted the performance by emphasizing local dynamics and increasing the sample size. A design with six layers, 512-D embeddings, and eight heads made the ViT two to three times smaller than its NLP counterparts. The study showed that end-to-end attention-based learning can surpass CNN/LSTM baselines for applied use. Siddhad et al. [41] applied a pure Transformer model with four stacked Transformer encoders and MHSA. Positional encoding integrated temporal order and channel information to enable the joint learning of spatiotemporal patterns. The model size was tuned per dataset to reduce overfitting and the Comp. Cost, simplify preprocessing, and improve efficiency. This approach removed the need for features like PSD or entropy. It achieved >95% Acc. for mental workload and >87% for age/gender classification, matching state-of-the-art results.

4.2.2. Generative and Self-Supervised Foundation Models

Transformers have also been used as foundational models by using self-supervised or generative learning to extract robust representations, synthesize EEG signals, and support cross-task generalization. Dosovitskiy et al. [34] introduced ViT. It replaces convolutional feature extractors by dividing images into fixed-size patches, embedding them, and applying MHSA. This design removes CNNs’ inductive biases and enables flexible and generalizable feature learning. ViT models (Base, Large, Huge) were pretrained on large datasets like ImageNet-21k and JFT-300M. MHA encodes diverse interactions in parallel, and pretrained representations allow high Acc. on smaller datasets. ViT proves that trained Transformers can match or surpass CNNs in FE while offering faster, more adaptable performance. This approach inspired EEG-specific Transformers like EEGPT [46]. Omair et al. [44] developed the Generative EEG Transformer (GET), a GPT-style [31] model that learns long-range EEG features through self-supervised signal generation. By predicting future EEG samples, GET forces attention layers to extract oscillations and distant dependencies. Pretraining on diverse EEG datasets rendered GET a foundational model. This improved subsequent tasks like epilepsy detection and BCI control while generating robust synthetic EEG for data augmentation, surpassing generative adversarial network (GAN) methods. Once pretrained, GET reduces the reliance on manual preprocessing and customized design. Lim et al. [45] proposed EEGTrans, a two-stage generative Transformer that integrates a vector-quantized autoencoder (VQ-VAE) with a Transformer decoder for EEG synthesis. The VQ-VAE compresses EEG into discrete latent tokens while filtering noise. The Transformer decoder models these tokens autoregressively, reconstructing realistic EEG with preserved spectral characteristics. This efficient separation of local and global modeling reduces the sequence length and allows a focus on informative features. EEGTrans resulted in realistic data augmentation, surpassing GAN-based methods. It also demonstrated strong cross-dataset generalization and robust unsupervised pretraining. Wang et al. [46] introduced EEGPT, a Transformer pretrained with masked self-supervised learning. EEG signals were segmented along time and channels with large and masked portions (50% time, 80% channels). Then, an encoder was trained to reconstruct missing data while aligning latent embeddings via a momentum encoder. This strategy forced EEGPT to learn spatiotemporal dependencies to produce robust representations. With 10 M parameters and minimal fine tuning, EEGPT achieved high performance across diverse EEG tasks. The masking strategy doubled data augmentation and improved generalization while avoiding task-specific model design. These models provide scalable, reusable EEG representations that reduce the fine tuning costs.

4.2.3. Modular and Dual-Branch Spatiotemporal Transformers

Some approaches model spatial and temporal EEG features using attention to improve the interpretability, discriminative power, and efficiency for tasks like ER and MI. Song et al. [39] proposed S3T, a two-branch Transformer for EEG MI that separates spatial and temporal FE. A spatial filtering module (CSP) improves the signal quality, followed by an encoder to capture dependencies between brain regions via SA. A Transformer then focuses on sequential time steps to extract evoked patterns. With only three MHA layers, this modular design directs each encoder to a specific signal aspect to improve efficiency and reduce overfitting. Trained end-to-end on BCI Competition IV-2a, S3T achieved 82–84% Acc. Its shallow design and integrated spatial filtering enhanced its generalization without large datasets. Du et al. [42] proposed ETST, a dual-encoder Transformer that separately models EEG features for person identification. The Temporal Transformer Encoder (TTE) treats each time point as a token to capture correlations, rhythms, and ERPs, while the Spatial Transformer Encoder (STE) treats each channel as a token to model connectivity. Preprocessing with bandpass filtering, artifact removal, and z-score normalization reduced noise. Trained without pretraining or augmentation, ETST achieved high Acc. It was also shown that modular attention aligned with the EEG structure in a compact model resulted in rich discriminative representations. Hu et al. [108] presented HASTF, a hybrid spatiotemporal attention network for EEG-based ER. EEG was filtered into five frequency bands using differential entropy (DE) features extracted from 1 s windows. These features were arranged into 3D patches to reflect the scalp topology. Spatial features were extracted by the Spatial Attention Feature Extractor (SAFE), which combines a U-shaped convolutional fusion module, skip connections, and parameter-free spatial attention. The Temporal Attention Feature Extractor (TAFE) applied positional embeddings and SA to model temporal dynamics. HASTF achieved high Acc. > 99%. Ablation studies showed temporal attention as the most impactful component. Muna et al. [109] introduced SSTAF, or the Spatial–Spectral–Temporal Attention Fusion Transformer, for upper-limb MI classification. EEG undergoes bandpass (8–30 Hz) and notch filtering, common average referencing, segmentation, and normalization. A Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) produces 4D time–frequency features. These rhythms were processed by spectral and spatial attention modules and an encoder to model temporal and channel interactions. SSTAF achieved 76.83% on EEGMMIDB and 68.30% on BCI Competition IV-2a, outperforming prior CNN and Transformer models. Ablation studies highlighted the role of the encoder in capturing temporal dynamics and attention modules in improving the Acc. Wei et al. [110] further refined dual-encoder modeling for EEG ER by separating temporal and spatial dependencies. A time step attention encoder extracted sequence-level features per channel, while a channel attention encoder captured interchannel relationships. A weighted fusion module combined these representations to improve the discriminative power and eliminate redundant computation. The approach achieved 95.73% intrasubject and 87.38% intersubject Acc.

4.2.4. Ensemble and Multidomain Transformers

Ensembles and specialized Transformers capture spectral and temporal patterns to enhance robustness and overall performance. Zeynali et al. [43] proposed a Transformer ensemble for EEG classification, where each model focuses on a different feature domain. A temporal Transformer captures waveform dynamics and short-term dependencies from raw EEG. A spectral Transformer processes PSD inputs to extract frequency-domain features and cross-frequency relationships. Their combination produced rich representations that led to strong results (F1 98.9% for cognitive workload). PSD preprocessing and targeted attention reduced noise and emphasized discriminative patterns. This fusion increased the computation, but the lightweight models mitigated overfitting, sped up convergence, and generalized across tasks without heavy pretraining. Ghous et al. [111] proposed a Transformer-based model for ER. Training proceeded in two stages: attention-enhanced base model development (AE-BMD) on SEED-IV and cross-dataset fine-tuning adaptation (CD-FTA) on SEED-V and MPED for generalization. Preprocessing was performed using Kalman and Savitzky–Golay (SG) filtering. FE included mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), gammatone frequency cepstral coefficients (GFCCs), PSD, DE, Hjorth parameters, band power, and entropy measures. Class imbalance was addressed using the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE). Spectral and temporal attention, positional encoding, MHA, and RNN/MLP-RNN layers captured precise patterns. The model achieved Acc. of 84% (SEED-IV), 90% (SEED-V), and 79% (MPED).

4.2.5. Specialized Attention Mechanisms and Dual Architectures

Mechanisms like gating, capsules, or regularization stabilize training, capture long-term dependencies, and refine EEG feature representations. Tao et al. [40] proposed a gated Transformer (GT) for EEG decoding. They integrated GRU/LSTM-inspired gating mechanisms into SA blocks to preserve the relevant EEG context, suppress noise, and stabilize FE over long sequences. The gating provides implicit regularization that improves convergence and maintains session stability. Trained from scratch without pretraining or augmentation, the model efficiently learns discriminative features for tasks such as continuous EEG decoding or ERP analysis. Wei et al. [112] introduced TC-Net, a Transformer capsule network, for EEG-based ER. They segmented EEG signals into non-overlapping windows and then processed them via a temporal Transformer module. A novel EEG PatchMerging strategy was used to balance global and local representations. Features were refined using an emotion capsule module that captured interchannel relationships before classification. TC-Net achieved strong performance on the DEAP and DREAMER datasets. It combines global context modeling, localized feature merging, and capsule refinement to improve the discriminative power, reduce redundancy, and enable efficient, robust recognition.

4.2.6. Cross-Integration Overlaps

Transformer-based EEG models have conceptual overlaps, where raw, generative, modular, ensemble, and hybrid approaches aim to improve efficiency, generalization, and scalability. All models [34,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,108,109,110,111,112] use SA mechanisms for FE. However, they differ in how they exploit it for efficiency. We classify the system in [46] under foundation models (Section 4.2.2) since its primary focus is masked self-supervised pretraining, despite combining it with spatiotemporal decomposition principles (Section 4.2.3) through time-channel segmentation. EEGTrans [45] incorporates a generative reconstruction mechanism within a two-stage architecture like modular Transformers (Section 4.2.3), but we place it under generative models (Section 4.2.2) since unsupervised representation learning is its central innovation. Models like those in [39,42] share parallel attention modules (Section 4.2.4) and dual-encoder hierarchies (Section 4.2.5). However, we place them under modular spatiotemporal designs (Section 4.2.3) to demonstrate their efficient decomposition, rather than dual fusion. Moreover, Refs. [43,111] utilize spectral and temporal attention (Section 4.2.3) within ensemble frameworks, but we group these models into multidomain ensembles (Section 4.2.4) because they focus on cross-domain integration. The works in [40,112] employ gating and capsule mechanisms, which can be considered as extensions of modular (Section 4.2.2) or generative Transformers (Section 4.2.3), but we classify them as specialized and hybrid attention mechanisms (Section 4.2.5) to highlight their focus on efficiency and model stability, rather than representational design.

Table 3.

Transformer-based architectures for EEG classification.

Table 3.

Transformer-based architectures for EEG classification.

| Ref. | Author/Year | Model | Protocol | Samples | Channels | Inspiration Basis | Acc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [38] | Arjun et al. 2021 | ViT-CWT, ViT-Raw EEG | EMO-VAT | 32 | 32 | T Encoder (ViT) | 97.00/95.75 99.40/99.10 |

| [34] | Dosovitskiy et al. 2021 | ViT (Base/Large/Huge) | T Encoder (ViT) | 77.63–94.55 | |||

| [39] | Song et al. 2021 | S3T | MI | 9/9 | 22/3 | T Encoder [CNN] | 82.59/84.26 |

| [40] | Tao et al. 2021 | Gated Transformer | MI, VAT | 109/6 | 64/128 | T Encoder [GRU] | 61.11/55.4 |

| [42] | Du et al. 2022 | ETST | Resting | 109 | 64 | T Encoder | 97.29–97.90 |

| [43] | Zeynali et al. 2023 | Ensemble Transformer | VEPs | 8 | 64 | T Encoder | 96.10 |

| [112] | Wei et al. 2023 | TC-Net | EMO, AVP | 32/23 | 48/15 | T Encoder [CapsNet, ViT] | 98.59–98.82 |

| [41] | Siddhad et al. 2024 | Transformer-based | Resting | 60/48 | 14 | T Encoder | 95.28 |

| [44] | Omair et al. 2024 | GET | MI/Alpha EEGs | 9/20 | 3/16 | Transformer | 85.00 |

| [46] | Wang et al. 2024 | EEGPT | ERPs, MI, SSVEP, EMO | 9-2383 | 58/3-128 | Transformer [BERT, ViT] | 58.46–80.59 |

| [108] | Hu et al. 2024 | HASTF | EMO | 32/15 | 32/62 | Transformer [BERT] | 98.93/99.12 |

| [110] | Wei et al. 2025 | Fusion Transformer | EMO | 62 | T Encoder | 87.38/95.73 | |

| [45] | Lim et al. 2025 | EEGTrans | MI | 1/7/9/14 | 3/22/59/128 | Transformer | 80.69–90.84 |

| [111] | Ghous et al. 2025 | AE-BMD, CD-FTA | EMO | 15/20/23 | 62 | T Encoder [RNN, MLP] | 79.00–95.00 |

| [109] | Muna et al. 2025 | SSTAF | MI | 103/9 | 64/22 | Transformer | 68.30/76.83 |

Acc.: Accuracy, AVP: Audiovisual Evoked Potential, BERT: Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, CapsNet: Capsule Network, EMO: Emotion Protocol, EMO-VAT: Emotion with Visual Attention Task, ERP: Event-Related Potential, GRU: Gated Recurrent Unit, MI: Motor Imagery, MI/Alpha EEG: Motor Imagery with Alpha EEG, MLP: Multilayer Perceptron, Resting: Resting Protocol, RNN: Recurrent Neural Network, SSVEP: Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential, T Encoder: Transformer Encoder, Transformer: Transformer Model, VAT: Visual Attention Task, ViT: Vision Transformer, VEP: Visual Evoked Potential.

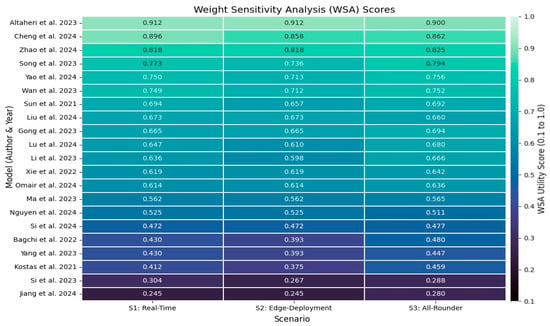

4.3. Efficiency in CNN–Transformer-Based Hybrids

Recent advances in EEG decoding have combined Transformer-based architectures with CNNs or TCNs to capture local and global features efficiently (Table 4). Key ideas have included hybrid CNN–Transformer designs, multibranch networks for parallel FE, temporal convolution modules, and self-supervised pretraining for richer feature maps. Many models have also used spatiotemporal attention and hierarchical encoding like patching or multistage FE to improve the Acc. and efficiency. The following sections review these models.

4.3.1. Sequential Pipelines

Sequential pipelines apply CNNs first to extract localized spatiotemporal representations. These features are then fed into Transformer encoders, which extract long-range relationships. These designs preserve the hierarchical nature of EEG while improving efficiency through convolutional prefiltering. Sun et al. [113] combined CNN-based spectral and temporal filtering with Transformer attention. Although detailed architectural specifications were not disclosed, the hybrid model demonstrated significant Acc. gains over CNN or RNN baselines. Omair et al. [114] proposed ConTraNet, a hybrid CNN–Transformer architecture for both EEG and electromyography (EMG). CNN layers extracted local patterns, and the Transformer modeled long-range dependencies. Designed to generalize across modalities and tasks, ConTraNet achieved top performance on 2–10-class datasets. With limited data, CNN filtering improved efficiency by reducing overfitting and helping the Transformer to focus on key global patterns. Wan et al. [115] developed EEGFormer. They employed a depthwise 1D CNN frontend to extract channel-wise features before feeding them into a Transformer encoder for spatial and temporal SA. The depthwise CNN reduced the parameters, allowing end-to-end training on raw EEG. EEGFormer achieved high performance across multiple tasks (emotion, depression, SSVEP). Ma et al. [116] proposed a hybrid CNN–Transformer for MI classification. Preprocessing included 4–40 Hz bandpass filtering, z-score normalization, and one versus rest (OVR)-CSP. A two-layer CNN extracted local spatiotemporal features, complemented by MHA across channels and frequency bands. The model achieved 83.91% Acc. on BCI-IV 2a. It outperformed CNN-only (58.10%) and Transformer-only (46.68%) baselines, showing efficient joint local–global FE. Zhao et al. [117] introduced CTNet, a CNN–Transformer hybrid for MI EEG. CNN layers extracted spatial and temporal features, followed by Transformer attention across channels and time. CTNet showed improvements of 2–3% over prior hybrids (82.5% BCI-IV 2a, 88.5% BCI-IV 2b). Liu et al. [118] developed ERTNet, an interpretable CNN–Transformer framework for emotion EEG. Temporal convolutions isolated important frequency bands, spatial depthwise convolutions captured the channel topology, and a Transformer fused abstract spatiotemporal features. Achieving 74% on DEAP and 67% on SEED-V, the model provided attention-based interpretability and reduced feature dimensionality. These models reduce overfitting and memory use and perform well in MI and ER.

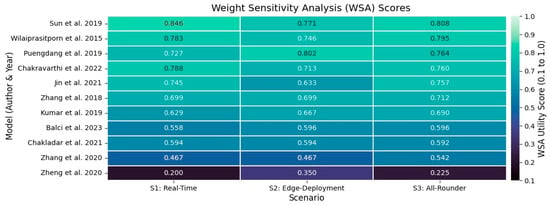

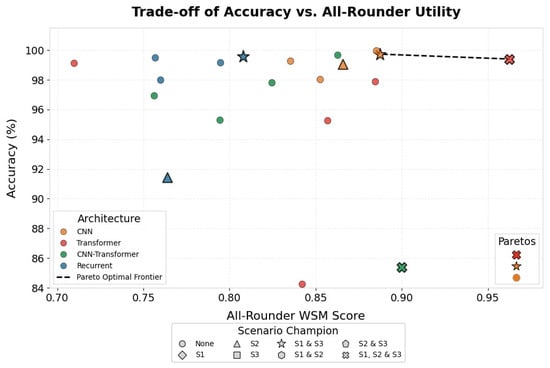

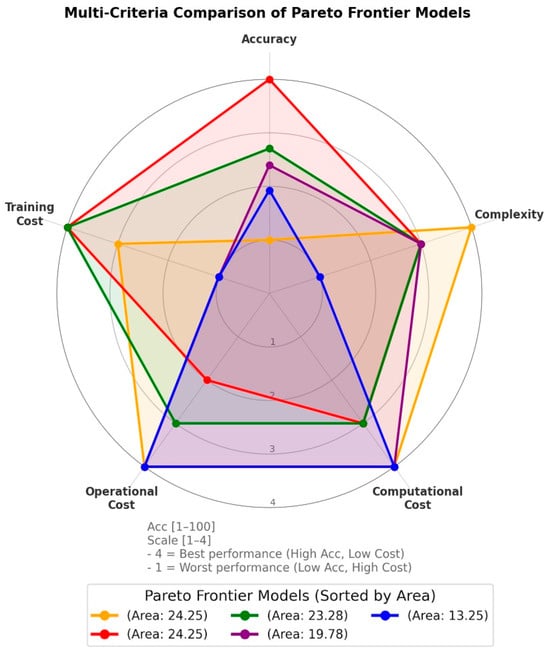

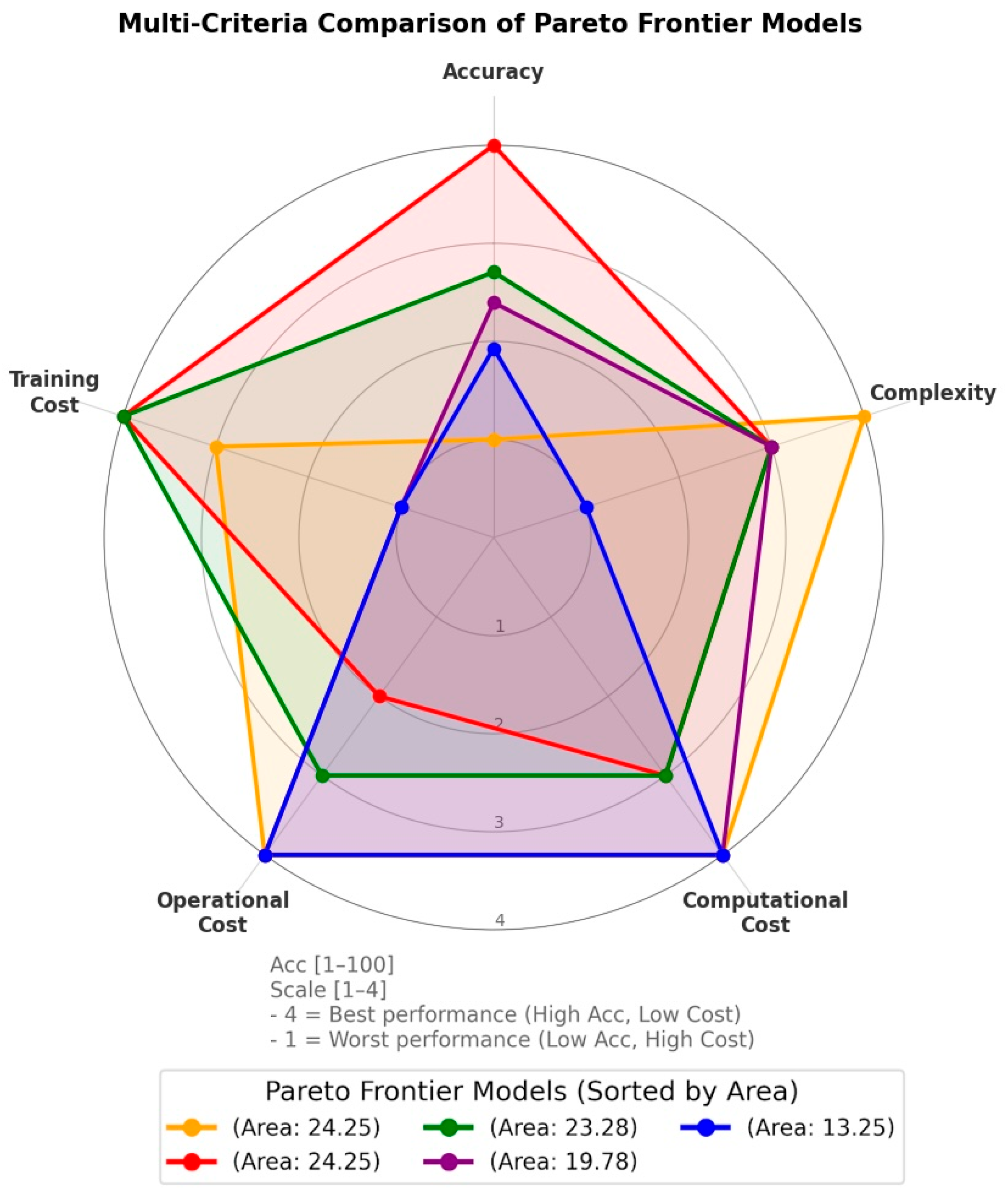

4.3.2. Parallel and Multibranch Blocks