1. Introduction

Industrial batch processes in food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, and wastewater treatment depend critically on Clean-in-Place (CIP) operations and similar multi-stage procedures to guarantee hygiene, product quality, and regulatory compliance [

1,

2]. These cycles typically execute multi-stage programs—for example, pre-rinse, alkaline wash, intermediate rinse, acid wash, sanitizing and final rinse—under tight constraints on temperature, flow, conductivity and contact time [

2,

3]. In current practice, such sequences are orchestrated by programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and supervised through SCADA systems, where operators monitor trends, acknowledge alarms and manually interpret complex process conditions. While this architecture is robust and widely adopted, it offers limited support for proactive decision-making, root-cause analysis or flexible what-if exploration over historical and real-time data—limitations that become increasingly problematic as plants grow in complexity and product portfolios diversify [

3,

4].

To address the need for flexibility and scalability, recent Industry 4.0 frameworks advocate modular, component-based and microservice-oriented architectures for industrial automation [

5,

6]. These approaches promote loose coupling between control, monitoring, data management and higher-level applications, enabling incremental deployment and technology heterogeneity. Previous work on component-based microservices for bioprocess automation has shown that containerised services and publish/subscribe communication can decouple control and supervision across heterogeneous equipment, including bioreactors and CIP systems while meeting industrial real-time and robustness requirements [

6]. Complementary contributions in bioprocess monitoring and control have proposed advanced observers, model predictive controllers and fault-detection schemes, but typically focus on algorithmic performance rather than on how human operators interact with increasingly complex automation stacks in day-to-day operation [

1].

In parallel, large language models (LLMs) and conversational agents have emerged as powerful tools for making complex data and models more accessible to domain experts, enabling natural-language querying, explanation and guidance [

7,

8]. Early studies in industrial settings indicate that LLM-based assistants can help operators explore process histories, retrieve relevant documentation and reason about abnormal situations using free-form queries [

8]. However, integrating LLMs into safety-critical environments remains challenging: LLM outputs are non-deterministic, may hallucinate and must coexist with hard safety constraints, deterministic interlocks and real-time requirements [

7,

8]. Existing architectures rarely combine deterministic rule-based supervision, continuous analytics and LLM-based conversational interfaces in a way that preserves safety while providing meaningful assistance for CIP operations and other multi-stage cleaning or batch processes.

1.1. From Reactive Alarms to Diagnostic Intelligence

Modern food and beverage facilities equipped with advanced control strategies—including model-based flow optimization and automated parameter regulation—have achieved significant process stability. In such environments, catastrophic process failures are rare, and traditional alarm systems designed to detect imminent faults often generate excessive nuisance alerts that operators learn to ignore or dismiss [

9]. The supervisory challenge has consequently evolved from

detecting failures to

interpreting operational signals: distinguishing between acceptable process variability and subtle patterns indicating emerging maintenance needs before they impact production [

10,

11].

Consider a CIP execution where flow rates are 10% below optimal but still within regulatory acceptance bounds. A traditional threshold-based alarm system remains silent, yet this pattern—if consistent across multiple cycles—may signal gradual pump wear requiring scheduled maintenance. Similarly, slight temperature deviations that do not compromise product safety may indicate boiler efficiency degradation, and conductivity variations within specification may reflect dosing pump calibration drift. In all cases, individual executions complete successfully by specification, but trend analysis across execution cycles reveals actionable maintenance opportunities that can prevent unplanned downtime and extend equipment lifespan [

11].

Extracting these diagnostic insights currently depends on expert operator knowledge and time-intensive manual log analysis—a process that scales poorly as facilities expand and product portfolios diversify. Moreover, the high dimensionality of sensor data (dozens of variables sampled at sub-second intervals) makes it difficult for operators to recognize subtle patterns amid normal process variability [

9].

In well-optimized plants where CIP executions routinely meet specifications, failures are rare but emerging equipment degradation must be identified through longitudinal trend analysis rather than catastrophic fault detection. A system that monitors 100 consecutive successful CIP runs provides no evidence of diagnostic capability; conversely, analyzing executions that span the operational spectrum—from nominal baseline to preventive warning patterns to diagnostic alert regimes—demonstrates the architecture’s ability to distinguish acceptable process variability from systematic equipment drift requiring maintenance intervention before operational impact occurs.

1.2. Proposed Architecture and Evaluation Approach

This paper proposes a generic, process-agnostic multi-agent architecture for AI-assisted monitoring and decision support in industrial batch processes. The architecture is instantiated and evaluated following a case study design in the Clean-in-Place (CIP) system of an industrial beverage plant, aimed at demonstrating architectural feasibility and diagnostic capabilities under realistic operating conditions rather than statistical generalization across populations of plants. While tailored here to CIP, the architectural components—process-aware context management, hybrid deterministic/LLM supervision, and incremental agent deployment—are designed to be transferable to other multi-stage batch operations (fermentation, distillation, pasteurisation) by reconfiguring process-specific rules and ontologies, though empirical validation in these contexts remains future work [

6,

12].

Unlike existing LLM-based assistants that typically operate as generic chatbots over manuals, historical databases or SCADA tags, the proposed architecture treats CIP executions as first-class contexts. A set of CIP-aware agents load their context on demand according to the active programme and stage, subscribe to enriched data streams and produce supervisory states, alerts and explanations that are aligned with the lifecycle of real CIP runs. This process-centric view of context enables new decision-support agents (LLM-based or otherwise) to be added incrementally, without modifying the underlying CIP programmes. This process-centric abstraction—treating batch executions as first-class contexts—constitutes the main architectural innovation, enabling heterogeneous AI components to operate over a shared process lifecycle without coupling to specific control logic.

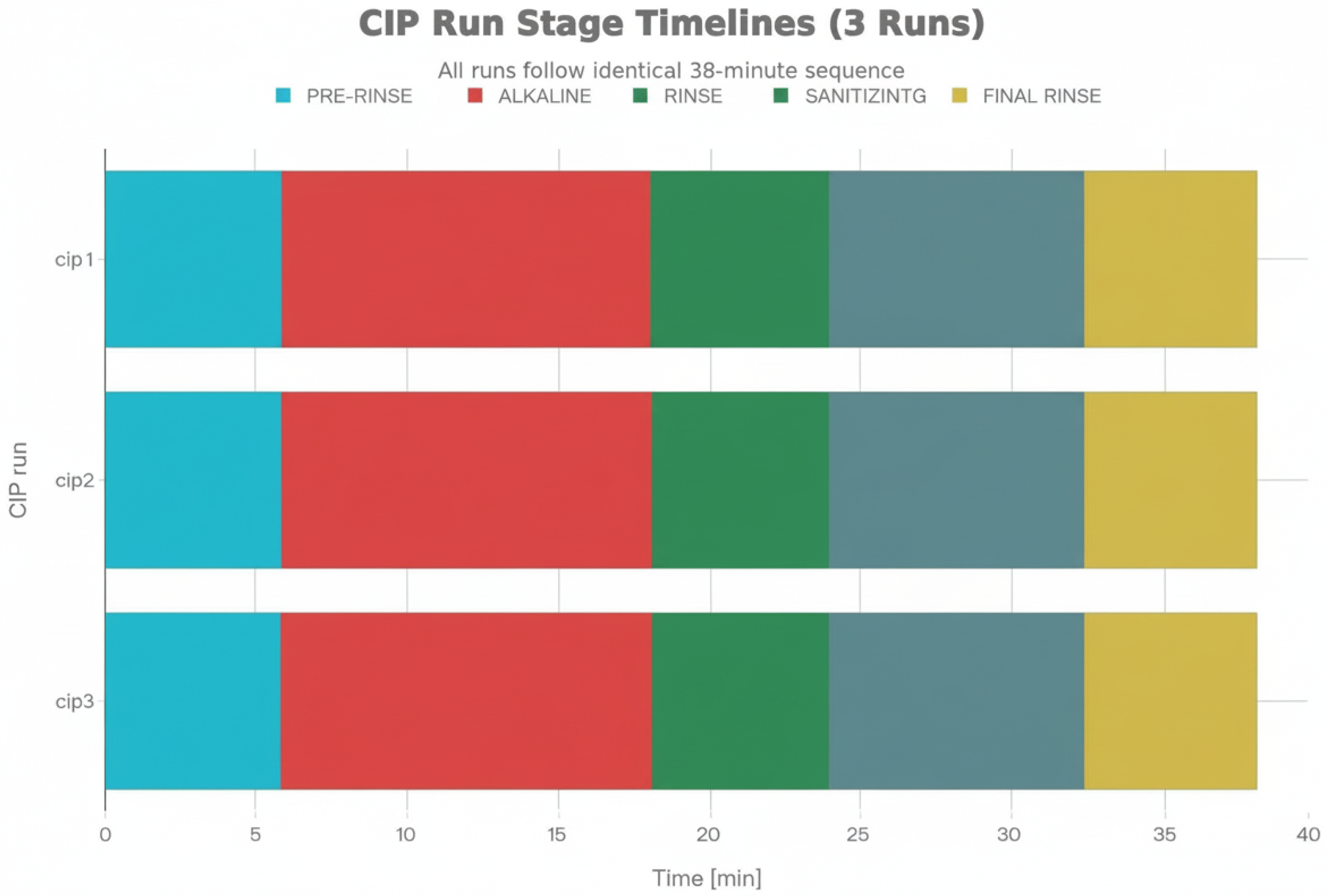

The architecture is instantiated and evaluated on real CIP cycles executed in an industrial beverage plant over a six-month deployment period. From 24 complete executions monitored during this period, 3 representative cases are purposively selected to provide architectural and operational validation evidence across the diagnostic spectrum observed during deployment: (i) a nominal baseline execution demonstrating routine equipment health, (ii) a preventive-warning case exhibiting subtle operational signals (flow reduction, temperature drift) that do not violate safety thresholds but indicate emerging equipment degradation requiring scheduled maintenance, and (iii) a diagnostic-alert regime capturing multiple concurrent deviations (pump wear, boiler efficiency loss, dosing drift) requiring prioritised maintenance review.

Rather than pursuing large-scale statistical generalization—which would be infeasible given the operational frequency of CIP cycles (1–3 executions per day) and the stable baseline achieved through prior control optimization—this case study evaluation demonstrates how the decision-support layer interprets operational signals, issues contextualized alerts, and generates natural-language diagnostic summaries that inform preventive maintenance decisions while preserving the determinism required for safety-critical alarm handling. The focus is on proving architectural feasibility and showing that the diagnostic patterns identified by the system align with maintenance needs confirmed by plant operators and maintenance logs.

1.3. Contributions and Scope

This work addresses the practical integration and deployment of existing AI techniques—large language models, fuzzy logic, statistical process control, and anomaly detection—into safety-critical industrial environments with legacy PLC/SCADA infrastructure and real-time constraints. The contribution lies in demonstrating how to bridge the gap between AI theory and industrial practice through system architecture, data transformation pipelines, and integration patterns that enable reliable AI-enhanced decision support in production environments. This aligns with the objectives of applied industrial AI research: integrating AI into legacy systems, addressing technical challenges such as data sparsity and model robustness, and demonstrating tangible improvements in industrial performance [

5,

6].

Four AI-specific deployment challenges are addressed: (i) temporal domain separation to preserve real-time safety guarantees despite non-deterministic LLM behavior, (ii) signal enrichment pipelines to bridge the semantic gap between numerical sensor data and natural language LLM inputs, (iii) retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to prevent hallucination in safety-critical contexts, and (iv) resource-efficient deployment under edge computing constraints. These integration challenges, while critical for industrial AI adoption, are distinct from algorithmic contributions proposing novel machine learning methods or model architectures. The focus is on making existing AI techniques operationally viable in industrial contexts where data sovereignty, resource limitations, timing guarantees, and fail-safe behavior are non-negotiable requirements.

The main contributions of this paper are:

A batch-process-aware, multi-agent decision-support architecture that treats batch executions (such as CIP cycles) as first-class contexts. Agents load their context on demand according to the active programme and stage, subscribe to enriched data streams and produce supervisory states, alerts and explanations aligned with the lifecycle of real batch runs. The architecture addresses AI-specific integration challenges, including (i) temporal domain separation to preserve real-time safety guarantees despite non-deterministic LLM components, (ii) signal enrichment pipelines to bridge the semantic gap between numerical sensor data and natural language LLM inputs, (iii) retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to prevent hallucination in safety-critical contexts, and (iv) resource-efficient deployment under edge computing constraints (

Section 3.6).

A process-centric context management approach that allows heterogeneous AI components (rule-based agents, fuzzy logic, neural networks, LLM-based assistants) to be added incrementally. New agents can reuse the same process context and message bus without modifying the underlying control programmes or restarting the supervision layer.

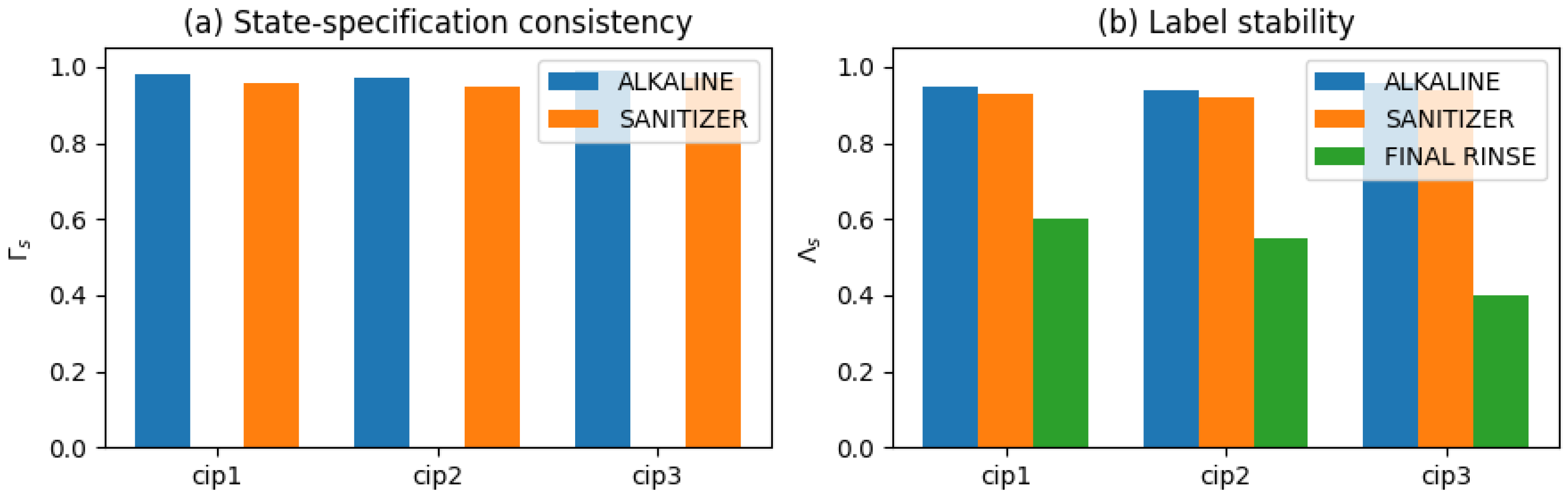

A set of process-level evaluation metrics that quantify the behavior of the decision-support layer over real executions, including compliance with stage specifications, consistency with state specifications, and stability of state labeling, complemented by spot checks of the numerical consistency between language-based summaries and enriched logs.

An experimental study on three complete CIP runs that instantiates the architecture in a real Cleani-in-Place application, demonstrating its ability to maintain high specification compliance across nominal, preventive and diagnostic scenarios, provide coherent and stable supervisory states, and generate data-grounded natural-language explanations in real time without altering the existing CIP control logic. The case studies collectively illustrate how diagnostic interpretation of alert patterns across execution cycles can inform preventive maintenance scheduling—addressing pump wear, boiler degradation and dosing system calibration—before operational impact occurs. These contributions are validated within the CIP deployment context; transferability to other batch processes (fermentation, distillation) is demonstrated conceptually through the generic architectural design (

Table 1) but requires empirical validation in future work.

Collectively, these contributions advance the state of knowledge by demonstrating—through a real industrial deployment—that hybrid deterministic/LLM architectures can be integrated into safety-critical batch supervision to support maintenance-oriented decision-making and by providing a reproducible architectural pattern and evaluation methodology that can guide future implementations in other batch process domains.

The architecture is implemented and deployed in a real industrial environment, supporting CIP operations at the VivaWild Beverages plant over a six-month validation period, which provides the basis for the experimental evaluation reported in this paper.

1.4. Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on bioprocess monitoring, Industry 4.0 architectures, LLMs in industrial settings, and task planning.

Section 3 presents the generic batch process supervision architecture, including the rationale for a layered, agent-based design, AI-specific integration challenges and solutions (

Section 3.6), and the process-agnostic instantiation pattern.

Section 4 details real-time data management and LLM integration strategies.

Section 5 describes the experimental methodology, including the industrial deployment, selection rationale for representative execution cases, data collection procedures and evaluation metrics.

Section 6 presents results from three representative CIP executions, quantifying compliance, state consistency, stability and LLM fidelity.

Section 7 discusses the findings, positions the work relative to existing approaches, addresses limitations and outlines directions for future longitudinal analysis.

Section 8 concludes the paper.

3. Generic Batch Process Supervision Architecture

3.1. Architectural Evolution from Prior Work

Existing industrial automation systems require component-based architectures to achieve scalability, interoperability, and reliability in complex manufacturing environments. Recent work [

6] demonstrated that component-based microservices architecture effectively addresses these requirements in batch bioprocess automation, establishing a proven foundation for flexible system composition, real-time coordination and cross-facility scalability.

This work extends that well-established architectural foundation to address a novel integration challenge: incorporating large language models (LLMs) into safety-critical industrial batch process supervision. Rather than proposing a fundamentally different architecture, this approach applies explicit temporal domain separation to the proven component-based microservices pattern: maintaining the microservices scalability, integration capability and reliability properties demonstrated in prior work while introducing LLM-based analytics in a non-deterministic layer carefully isolated from real-time safety-critical control.

The key architectural innovation is not the overall structure (which inherits principles from prior work) but rather the explicit separation of temporal domains—deterministic supervision (occupying the safety-critical layer) and non-deterministic analytics (occupying the LLM reasoning layer)—which enables safe integration of non-deterministic AI into systems requiring bounded real-time guarantees, a challenge not previously addressed in industrial batch process supervision.

Process-Agnostic Design: While the architecture is instantiated and evaluated here in the context of Clean-in-Place (CIP) operations in a beverage plant, its design is process-agnostic: the same component-based pattern applies to fermentation, distillation, pasteurisation, chemical synthesis, and other multi-stage batch procedures by reconfiguring process-specific rules, ontologies, and enrichment logic. This composability—the ability to adapt component-based architectures to new contexts through parameter configuration rather than architectural redesign—is inherited directly from prior work and preserved in this extension.

Presentation Structure: The architecture is presented through two complementary perspectives that build on this foundational understanding:

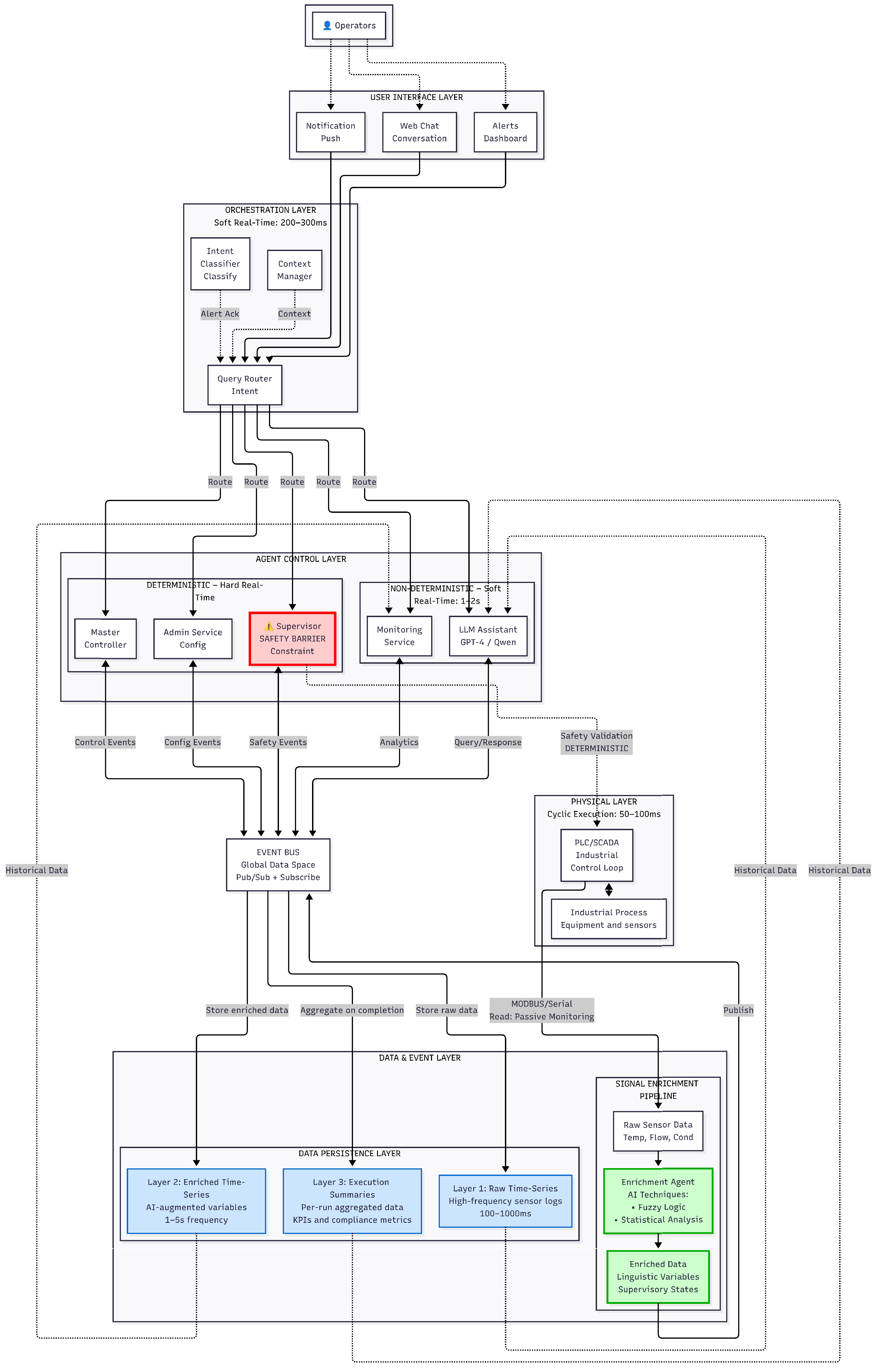

Conceptual Layered View (

Figure 1): Illustrates how temporal domain separation is achieved by decomposing the supervision problem into layers with distinct temporal constraints—deterministic safety-critical supervision (<100 ms), soft real-time coordination (200–500 ms), non-deterministic analytics (1–2 s), and asynchronous persistence. This view shows the separation between cyber (software) and physical (PLC/SCADA) domains, event-driven communication patterns inherited from the microservices foundation, and the role of the orchestration layer in routing operator intents to specialized agents while maintaining safety barriers.

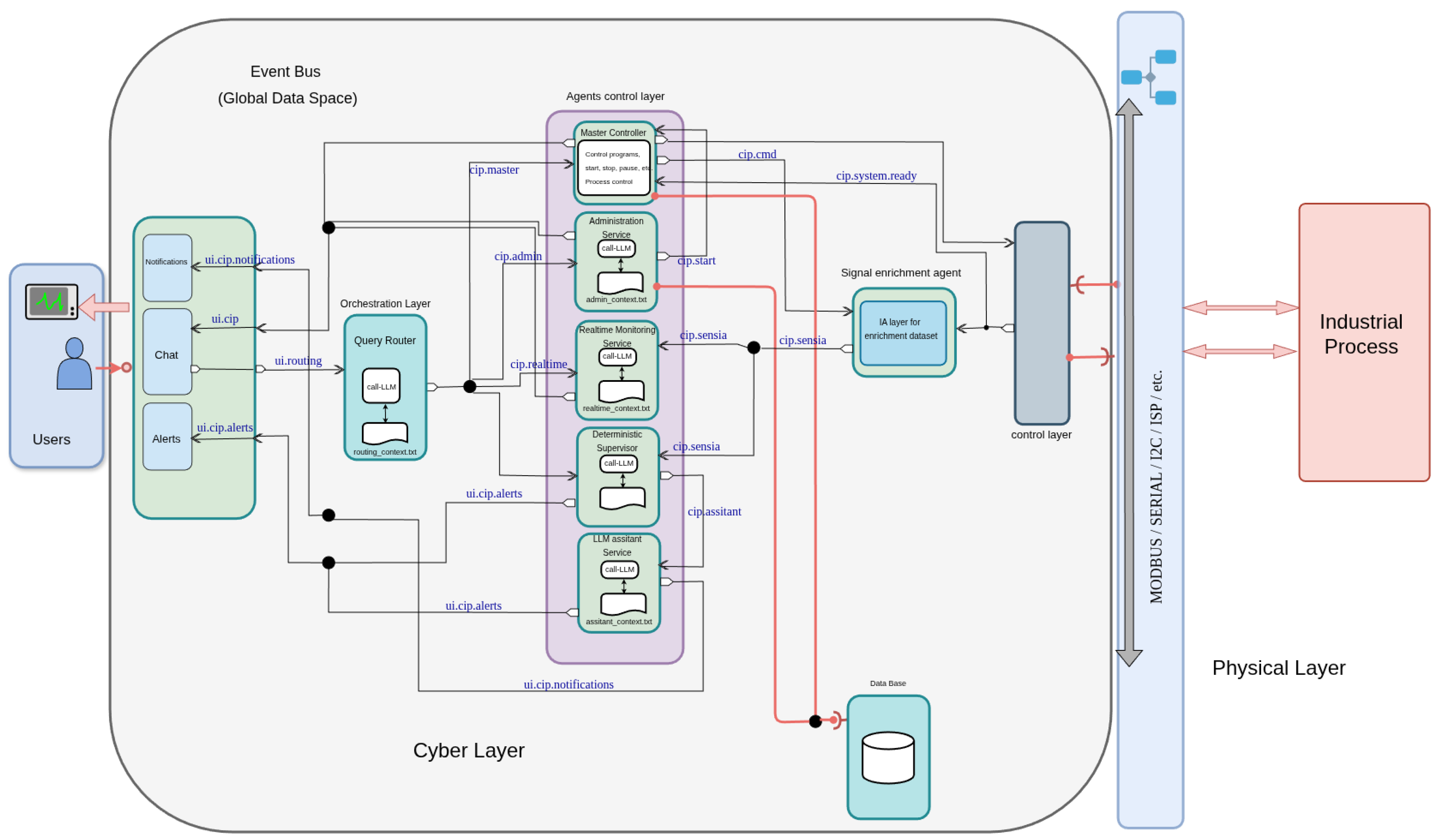

Detailed Component View (

Figure 2): Emphasizes the technical depth required for production deployment by specifying real-time constraints for each layer, data transformation pipelines implementing semantic bridging from industrial signals to natural language, temporal domain separation between deterministic and non-deterministic processing, and the three-tier data persistence strategy that scales from high-frequency raw sensor buffers to long-term execution summaries. This view demonstrates how the generic component-based approach is instantiated with concrete technologies and performance characteristics.

Together, these views provide both a high-level understanding of the architectural pattern inherited from prior work and the technical depth required for production deployment in safety-critical industrial environments.

3.2. Conceptual Architecture: Extending Microservices with Temporal Domain Separation

Building on the component-based microservices foundation established by [

6] this architecture extends those principles to address AI integration by introducing explicit temporal domain separation. The original microservices approach demonstrated scalability and integration through loosely coupled, independently deployable components. This work applies the same separation-of-concerns principle to time-domain constraints: creating distinct layers optimized for different temporal requirements—from sub-100 ms deterministic safety-critical supervision to 1–2 s non-deterministic LLM analytics—while preserving the composability and flexibility that made the original microservices pattern valuable.

Figure 1 illustrates this extension as a layered, event-driven architecture spanning from operator-facing interfaces down to physical process equipment. At its core, an Event Bus exposes a global data space where agents, user interfaces and the control layer exchange events and enriched data streams, while an intermediate orchestration layer routes operator requests to specialised agents according to user intention and process context. Critically, the temporal domain separation shown in this figure—with separate paths for deterministic supervision (<100 ms) and non-deterministic analytics (1–2 s)—represents the key architectural innovation extending the microservices foundation to safely integrate AI into safety-critical industrial environments.

The main architectural layers visible in this conceptual view are:

User Interaction Layer: Operators interact through a web interface providing natural-language chat, structured alarm panels and visual summaries of process status. Operators can ask questions in free text (e.g., about current batch progress, recent anomalies or historical comparisons), request specific functions (e.g., remaining time for a stage, list of active batch executions) or issue management actions (e.g., creating or starting batch requests). The interface normalizes these inputs and forwards them to the orchestration layer as high-level events containing the user query, role and context. This interface design follows the principle established in prior work: separating operator concerns (intent expression) from system concerns (intent fulfillment).

Orchestration Layer: Acts as a mediator between user intents and the underlying agents, a key component-based microservices pattern from prior work. It receives normalized requests from the interaction layer and classifies them into intent categories such as control (start/stop batch, interact with the master process), configuration (programmes, equipment, permissions), deterministic analysis (current state, diagnostics, time estimates), real-time free analysis (ad hoc queries over the live buffer) andoffline analysis (post-run reports over stored data). Critically, the orchestrator routes safety-critical requests to the Deterministic Supervisor (enforcing <100 ms response time) and advisory requests to the LLM Assistant (permitting 1–2 s soft real time). Based on this intent and the user role, the orchestrator dispatches the request to the appropriate agent via the data and event hub and later aggregates or reformats the response into a coherent message for the operator interface. This routing decision—the core of temporal domain separation—enables the system to leverage LLM capabilities for diagnostics while guaranteeing deterministic safety properties.

Agent Control Layer: Implements specialized microservices for process supervision, configuration management, and decision support, directly inheriting the loosely coupled component philosophy of prior work. Agents include:

Primary Controller: Coordinates batch execution lifecycles at the physical layer, implementing deterministic state machines proven reliable in industrial environments.

Administration Service: Manages configuration and governance (recipes, equipment definitions, permissions), enabling the flexibility through parameterization demonstrated as critical in prior work.

Deterministic Supervisor: Performs rule-based supervision with hard safety alerts operating within <100 ms constraints. This layer preserves all traditional supervision logic, ensuring that AI integration does not compromise safety guarantees established through decades of PLC/SCADA programming.

Real-time Monitoring Service: Provides flexible operator-driven analysis over live process data using LLM-backed analytics. This new agent (not present in prior work) bridges the gap between deterministic supervision and LLM-based reasoning by consuming enriched semantic representations rather than raw sensor streams.

Offline Analysis Service: Generates post-run reports and comparative analyses over historical data, operating asynchronously without impacting real-time constraints.

The independence of these agents—each handling distinct concerns—reflects the scalability and composability principles demonstrated in [

6].

Event Bus (Global Data Space): Underpins communication between all agents and the physical layer, implementing the inter-component communication pattern proven essential in microservices environments. The Event Bus is realized using Redis 7.2 with:

- –

Publish/subscribe channels for real-time events enabling decoupled agent-to-agent communication;

- –

Redis Streams for time-series storage of per-batch sensor trajectories, optimized for append-heavy industrial workloads with latency;

- –

Hash structures for configuration and resource status, enabling efficient lookups for context management.

This hub interface decouples producers (PLCs, sensors) from consumers (agents, UI), supporting multiple concurrent batch processes and allowing analytical capabilities to be extended without changes to control hardware—preserving the non-invasive integration pattern central to industrial safety. The choice of Redis (rather than traditional message brokers like RabbitMQ or Kafka) reflects the single-node, brownfield deployment scenario typical of industrial plants: Redis provides stream data optimization and sub-millisecond append latency without the distributed consensus overhead inappropriate for on-premise industrial computing.

Physical Layer: Encompasses PLC/SCADA systems executing deterministic control loops (50–100 ms cyclic execution) and industrial process equipment (reactors, pumps, valves, sensors, actuators). The architecture integrates non-invasively through passive monitoring (read-only sensor access via MODBUS/Serial) and safety-validated command injection (Deterministic Supervisor issues emergency stops after constraint validation). This non-invasive approach—proven in prior work—remains unchanged, ensuring that existing PLC programs and certifications are unaffected by the addition of LLM-based decision support.

A key advantage of adopting an orchestrator-based, service-oriented architecture—established as essential in prior work—is that new decision-support agents can be added incrementally, without modifying the underlying batch programmes or restarting the supervision layer. Each agent subscribes to the same enriched data streams and loads its context according to the active batch execution and stage, producing additional supervisory states, diagnostics, preventive maintenance recommendations or trend analyses. This design makes it possible to combine heterogeneous AI techniques (for example, rule-based agents, fuzzy logic, neural networks, LLM-based assistants) within a common framework and to evolve the decision-support and diagnostic capabilities over time as new agents are deployed. The temporal domain separation introduced here enables this heterogeneity while maintaining safety: deterministic agents always retain veto power over LLM-generated recommendations.

The architecture does not assume a single monolithic AI component, but rather a distributed set of process-aware agents coordinated by an orchestrator—precisely the pattern proven scalable in industrial bioprocess automation [

6]. The evaluation presented in this work focuses on one such configuration, where rule-based supervision (Deterministic Supervisor) and a language model assistant (Real-time Monitoring Service and LLM Assistant) share the same batch context for CIP operations, with the Deterministic Supervisor maintaining ultimate control through command validation. However, the same pattern can be used to integrate further agents (for example, predictive models for equipment degradation, optimization modules for chemical consumption, yield forecasting models) without disrupting existing services or batch control programmes. This extensibility through agent addition (rather than architectural redesign) exemplifies the flexibility that made the original microservices approach valuable for industrial environments.

The temporal domain separation visible in

Figure 1 represents this work’s core extension of the microservices foundation. Whereas traditional microservices focus on separating concerns through function specialization (Master Controller vs. Administration Service), this architecture adds temporal separation: routing requests bound by real-time constraints to the Deterministic Supervisor (enforcing <100 ms worst-case response time) and advisory requests to the LLM Assistant (permitting 1–2 s soft real time). This separation enables the system to leverage non-deterministic AI for operator decision support without compromising the deterministic safety guarantees that industrial plants depend on. The orchestrator implements this routing decision transparently—operators request information or diagnostics through natural language, but the system automatically routes safety-critical information through determinism-preserving paths and advisory information through LLM-capable paths.

Technology Stack Justification and Design Principles

The specific technologies selected for implementation express the architectural principles inherited from prior work. Rather than arbitrary choices, each technology implements a principle proven in component-based microservices for industrial systems.

Table 1 provides the mapping from architectural principles to technological instantiation:

Redis Streams are selected for the Event Bus specifically because it implements the inter-component communication pattern proven essential in microservices environments. Key design rationale:

Microservices efficiency without distributed complexity: Traditional message brokers (RabbitMQ, Kafka) optimize for fault tolerance across distributed clusters through consensus protocols and persistent replication—appropriate for cloud-scale systems but introducing unnecessary latency in single-node industrial deployments. Redis Streams provide efficient time-series append operations (O(1) latency) without distributed coordination overhead.

Stream data optimization: Industrial systems generate continuous time-series data (10–1000 Hz sensor sampling, 10,000–100,000 measurements per batch cycle). Redis Streams’ representation optimizes for append-heavy workloads typical of sensor data, providing memory-efficient ring buffers and sub-millisecond append latency critical for real-time agent communication.

Single-node brownfield deployment: Most existing industrial facilities operate on-premise with dedicated server hardware (not cloud infrastructure). Redis eliminates distributed consensus overhead, aligning with prior work’s emphasis on operational simplicity—a single Redis instance runs locally, operators understand local-running processes, data sovereignty regulations are satisfied.

Preserves component composability: Each microservice component (Orchestration Agent, Deterministic Supervisor, Enrichment Pipeline) communicates through Redis, maintaining the loose coupling and independent deployability demonstrated as essential in prior work.

Qwen 2.5 is selected for embedded LLM inference recognizing that edge deployment represents a fundamental constraint in industrial environments—a principle demonstrated throughout prior work on bioprocess automation. Key selection criteria:

Code generation capability for downstream task automation: Unlike base language models (LLaMA 2, Mistral) designed primarily for fine-tuning, Qwen 2.5 includes instruction-tuning optimized for task-specific code generation. This enables integration with downstream analytics tools (e.g., PandasAI for exploratory analysis of enriched time-series) and operator procedure synthesis from natural language requests—capabilities beyond pure conversational reasoning.

Instruction-tuned for industrial domain tasks: Mistral and LLaMA 2 represent base models optimized for general-purpose language understanding. Qwen 2.5’s instruction-tuning targets task-specific reasoning—exactly the diagnostic and predictive analytics required in batch process supervision—improving reliability without requiring domain-specific fine-tuning data often unavailable in brownfield facilities.

Embedded deployment optimization: Memory footprint (7B parameters require ∼14 GB VRAM) and inference latency (<2 s on consumer-grade NVIDIA RTX GPUs typical in industrial settings) compatible with edge hardware constraints. This eliminates dependency on cloud API calls that prior work identified as problematic due to data sovereignty regulations (particularly strict in pharmaceutical manufacturing), network reliability constraints (industrial plants often operate on low-bandwidth networks), and latency requirements for real-time operator decision support.

Multilingual reasoning capability: Global beverage and pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities operate with operators across Spanish, English, and German linguistic communities. Qwen 2.5’s multilingual training ensures diagnostic reasoning remains consistent across operator language preferences—important for international production networks.

Data enrichment pipeline implements semantic bridging—the core transformation enabling LLMs to reason about industrial numerical signals. Fuzzy logic chosen as exemplifying this transformation:

Semantic representation over numerical classification: The enrichment goal is not classification accuracy (is this alarm state HIGH or MEDIUM?) but semantic representation converting temperature = 67.3 °C into Temperature: Optimal suitable for natural language LLM reasoning. Fuzzy logic and other interpretable enrichment methods provide this semantic transformation through linguistic variable assignment.

Interpretability critical in safety-sensitive decision support: Industrial decision support requires human oversight and override capability. Unlike black-box methods (SVM, neural networks), fuzzy logic produces explicit linguistic outputs (High, Rising, Concerning) operators can validate, understand, and override when necessary—essential for maintaining operator trust in LLM-assisted supervision where errors have economic (unplanned downtime: USD 10k–USD 100k/hour) and safety implications.

Compatibility with limited historical data: Brownfield facilities rarely maintain extensive historical sensor datasets suitable for neural network training. Fuzzy logic and comparable interpretable methods (rule-based statistical process control, isolation forest anomaly detection) require minimal historical tuning, making them appropriate for facilities where machine learning approaches cannot be trained due to data availability constraints.

Flexibility of enrichment approach: While fuzzy logic exemplifies the semantic enrichment concept, alternative methods providing comparable interpretability and data efficiency (symbolic rule-based classifiers, Bayesian networks for uncertainty quantification, one-class SVM for equipment degradation detection) could provide equivalent enrichment. The specific technology choice is less critical than the semantic bridging principle—converting sensor streams into natural language representations suitable for LLM reasoning.

3.3. Detailed Component Architecture: Real-Time Constraints and Data Flow

While

Figure 1 presents the conceptual organization as layered cyber-physical separation,

Figure 2 provides a complementary component-level perspective that emphasizes real-time constraints, data transformation pipelines, and the explicit separation between deterministic and non-deterministic processing domains. This view is essential for understanding how the architecture maintains safety guarantees while integrating LLM-based analytics, and for supporting production deployment in environments with bounded computational resources and hard real-time supervision requirements.

3.3.1. Orchestration Layer: Timing and Intent Classification

The Orchestration Layer operates under soft real-time constraints (200–500 ms), implementing three core components:

Context Manager: Maintains process-aware execution state, loading and unloading batch-specific configurations (programmes, equipment mappings, stage definitions) dynamically as executions start and complete. Ensures that each agent operates within the correct process context (CIP cycle, fermentation batch, distillation run) without requiring global state synchronization.

Intent Classifier: Analyzes incoming operator queries and UI events using pattern matching and lightweight natural language understanding (Alert Ack for alarm acknowledgments, user query text for conversational requests) to determine intent categories: control commands, configuration requests, safety queries, diagnostic analysis, or conversational analytics.

Query Router: Dispatches classified intents to specialized agents via named routing channels over the Event Bus (cip.cmd, cip.admin, cip.sensia, cip.Real-time, cip.assistant), ensuring that safety-critical commands bypass non-deterministic components and reach the Deterministic Supervisor directly.

This timing specification ensures that operator interactions receive responses within human perception thresholds (500 ms for interactive applications) while maintaining sufficient decoupling to prevent user interface load from affecting deterministic supervision performance.

3.3.2. Agent Control Layer: Temporal Domain Separation

The Agent Control Layer enforces strict separation between deterministic and non-deterministic processing domains to maintain safety guarantees while supporting flexible AI-enhanced analytics.

Deterministic Domain (Hard Real Time: <100 ms)

Safety-critical agents execute in bounded deterministic time under hard real-time constraints:

Master Controller: Orchestrates batch execution lifecycles, issuing start, stop, pause, and abort commands to the PLC/SCADA layer (cip.cmd channel). Enforces programme sequencing and stage transitions according to predefined recipes and interlock conditions, publishing lifecycle events (batch.start, stage.transition, batch.complete) that other agents subscribe to for context synchronization.

Administration Service: Manages configuration persistence and retrieval (cip.admin channel), including batch programmes, equipment definitions, sensor mappings, and alarm rule specifications. Provides versioning and audit trails for regulatory compliance (FDA 21 CFR Part 11, ISO standards), ensuring traceability of all configuration changes with timestamps, operator identity, and approval workflows.

Deterministic Supervisor (Safety Barrier): Implements the critical safety validation layer that separates non-deterministic AI components from physical equipment control (cip.sensia channel). This agent:

- –

Monitors enriched process variables against hard safety limits defined in the batch recipe (e.g., maximum temperature thresholds, minimum flow rate requirements, conductivity envelopes for sanitization stages).

- –

Computes discrete supervisory states (NORMAL/WARNING/CRITICAL) using rule-based logic executing in time per evaluation cycle.

- –

Issues emergency stop commands directly to the PLC/SCADA layer when safety thresholds are violated, bypassing all other agents to ensure fail-safe behavior.

- –

Logs all safety events (threshold violations, emergency stops, interlock triggers) to the Data Persistence Layer for post-execution forensic analysis.

This component enforces the safety barrier principle: LLM-generated recommendations and diagnostic insights produced by non-deterministic agents can inform operator decisions and trigger alerts, but cannot directly command actuators or override safety interlocks. All control actions must pass through deterministic validation (

Safety Validation DETERMINISTIC path in

Figure 2) before reaching the Physical Layer.

Non-Deterministic Domain (Soft Real-Time: 1–2 s)

Analytical agents operate under relaxed timing constraints, enabling more computationally intensive AI processing:

Real-time Monitoring Service: Maintains a rolling window of enriched process data in a context buffer suitable for ad hoc queries (cip.Real-time channel). Answers operator queries requiring correlations, aggregate statistics, and trend analysis during the run without strict real-time constraints. Implements deterministic data frame operations (Pandas, Polars) for numerical queries and provides diagnostic pattern summaries for the LLM Assistant.

LLM Assistant Service: Provides conversational analytics over live process buffers and historical execution logs using locally deployed large language models (Qwen 2.5 via Ollama, cip.assistant channel). Operates in a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) architecture:

- –

Maintains enriched process data (linguistic variables, supervisory states, trend indicators) in a context buffer.

- –

Answers free-form operator queries (“Why is flow lower than usual?”, “Is this temperature profile normal for Stage 3?”) by grounding responses in enriched time-series data and execution summaries, minimizing hallucination.

- –

Operates in read-only mode: cannot issue control commands or modify batch parameters, serving purely as a conversational analytics interface.

This separation ensures that LLM inference latency (typically 1–2 s for 7B parameter models on NVIDIA GPU infrastructure) cannot affect deterministic supervision or safety-critical decision paths.

All agents communicate exclusively through the Event Bus using publish–subscribe channels, enabling horizontal scalability and independent lifecycle management (agents can be started, stopped, or upgraded without disrupting other services or batch executions).

3.3.3. Signal Enrichment Pipeline

The Signal Enrichment Pipeline (visible in the right side of

Figure 2) transforms raw sensor streams into semantically meaningful process representations suitable for both deterministic supervision and LLM-based reasoning. This pipeline operates between the Physical Layer and the Event Bus, implementing a three-stage transformation.

Stage 1: Raw Sensor Data Acquisition

High-frequency measurements (temperature, flow, conductivity, pressure, level) are sampled at 100–1000 ms intervals from PLC/SCADA systems via industrial protocols (MODBUS/TCP, Serial RS-232/RS-485, TTY) [

40]. The Physical Layer publishes raw sensor readings (“Raw Sensor Data: Temp, Flow, Cond” in

Figure 2) to the Event Bus, providing a decoupled interface that isolates the enrichment pipeline from specific PLC vendors or communication protocols.

Stage 2: AI-Driven Enrichment Processing

The Enrichment Agent (green box in

Figure 2) applies multiple AI techniques in parallel:

Fuzzy Logic Systems: Transform numerical sensor readings into linguistic variables using trapezoidal membership functions (e.g., temperature ∈ {TooLow, Optimal, SlightlyHigh, Critical}). These linguistic assessments provide intuitive process state descriptions that operators can interpret directly and LLMs can reason over without requiring domain-specific fine-tuning.

Statistical Analysis: Compute rolling statistics (mean, standard deviation, rate of change) over sliding time windows (30 s, 5 min, 15 min) to detect process trends, oscillations, and drift patterns. Generate trend indicators (Stable, Increasing, Decreasing, Oscillating) and deviation scores (normalized distance from expected trajectory based on historical execution profiles).

These enrichment techniques execute in soft real time (processing latency typically 200–500 ms per sensor update), balancing computational cost with diagnostic value.

Stage 3: Enriched Data Publication

Enriched variables (“Enriched Data Streams: Linguistic Variables, Supervisory States” in

Figure 2) are published to the Event Bus at 1–5 s intervals via the

Publish channel, providing decision-support agents with high-level process representations. The enrichment frequency is deliberately lower than raw sensor sampling to reduce message throughput while still supporting real-time supervision.

This pipeline architecture enables LLM-based agents to reason over semantically meaningful process concepts (“Temperature is slightly high and increasing”) without requiring domain-specific model fine-tuning on raw numerical signals.

3.3.4. Data Persistence Layer: Three-Tier Storage Strategy

The Data Persistence Layer (bottom of

Figure 2) implements a hierarchical storage architecture optimized for distinct query patterns, retention policies, and performance requirements.

Layer 1: Raw Time-Series (High-Frequency Operational Buffer)

Storage: Redis Streams with bounded in-memory circular buffers ( records per active batch, ∼5 MB).

Retention: Expired immediately upon batch completion.

Frequency: 100–1000 ms (native sensor sampling).

Usage: Real-time anomaly detection, sub-second diagnostic queries, Deterministic Supervisor lookback windows.

Performance: memory growth, time-range queries, deterministic worst-case latency.

Layer 2: Enriched Time-Series (Medium-Term Trend Analysis)

Storage: Redis Streams with configurable retention policies (AOF persistence for warm data recovery).

Retention: Configurable based on real-time window definitions (activity-based: batch completion + TTL, time-based: rolling window with MAXLEN auto-eviction, event-based: context window around alarms).

Frequency: 1–5 s (AI-augmented variables: fuzzy states, trend indicators, anomaly scores).

Usage: Cross-cycle correlation queries (Monitoring Service), historical context queries (LLM Assistant), equipment health dashboards.

Performance: append (XADD), time-range queries (XRANGE), bounded memory footprint via MAXLEN and TTL policies.

Layer 3: Execution Summaries (Long-Term KPI and Compliance Records)

Storage: Redis Hashes (per-batch summaries) and Sorted Sets (time-indexed batch archive), persisted via AOF/RDB snapshots.

Retention: Configurable TTL policies (30–365 days typical, indefinite for regulatory compliance via selective key persistence).

Data: Batch metadata (programme, circuit, timestamps), stage-level KPIs (duration, compliance metrics, set-point tracking error), diagnostic summary (alarm counts, supervisory state distribution), maintenance flags linked to equipment assets.

Usage: Longitudinal trend analysis (6–12 months), equipment lifecycle assessment (1000+ cycles), regulatory audit trails.

Performance: hash field access (HGETALL), batch range queries (ZRANGEBYSCORE), efficient aggregations over time ranges without requiring relational joins.

This three-tier persistence strategy (visible as three blue boxes in

Figure 2, connected via “Store raw data”, “Store enriched data”, and “Aggregate on completion” paths from the Event Bus) addresses a fundamental tension in industrial AI deployment: real-time supervision requires low-latency access to recent high-resolution data, while long-term analytics and compliance require efficient storage and querying of aggregated historical records.

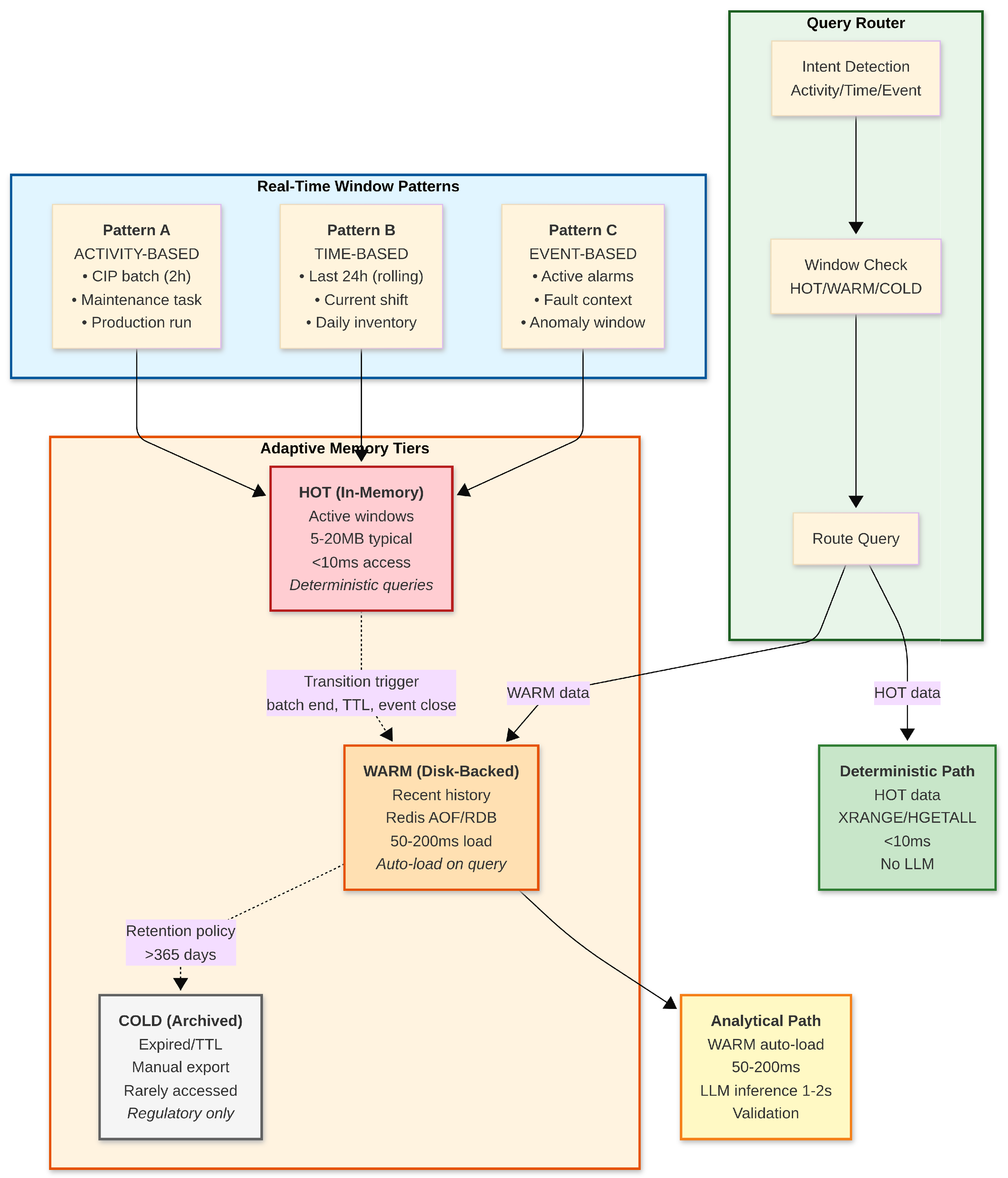

3.3.5. Configurable Real-Time Windows: Application-Dependent Memory Management

The three-layer persistence strategy implements a more general principle:

configurable real-time windows that define what data must reside in memory for fast deterministic decisions versus what can be loaded on-demand from disk-backed persistence. Unlike fixed temporal aggregation schemes (minute/hour/day hierarchies), the architecture allows window definitions to be configured based on process semantics, supporting three complementary patterns (

Figure 3):

Pattern A: Activity-Based Windows

For batch processes with discrete execution lifecycles (CIP cleaning cycles, fermentation batches, maintenance tasks), the real-time window corresponds to the active activity duration:

Window Definition: Data during active batch execution (e.g., CIP cycle: ∼2 h, 1 Hz sampling, 7200 samples).

Memory Residency: HOT (in-memory Redis Streams, 5–7 MB per batch).

Transition Trigger: Batch completion event.

Post-Transition: Compute batch summary (HSET to Hash), expire raw stream (TTL 24 h), archive summary to Sorted Set (ZADD with completion timestamp as score).

Query Behavior: Active batch queries use deterministic path (XRANGE, <10 ms). Historical batch queries load summaries from Hashes (HGETALL, <10 ms if cached) or warm data from AOF/RDB (50–200 ms if evicted).

Pattern B: Time-Based Windows

For continuous monitoring applications (cold chain temperature tracking, inventory levels, ambient conditions), the real-time window is a rolling time duration:

Window Definition: Fixed rolling window (e.g., last 24 h, 1 min sampling, 1440 samples).

Memory Residency: HOT (in-memory Redis Stream with MAXLEN 1440, auto-evicting oldest entries, ∼500 KB per sensor).

Transition Trigger: Time-based eviction (oldest sample > 24 h old).

Post-Transition: Compute daily summary (min/max/avg), persist to Hash, expire raw data.

Query Behavior: Queries within 24 h use deterministic path (XRANGE, <10 ms). Queries beyond 24 h load daily/monthly summaries from Hashes or warm data from persistence.

Pattern C: Event-Based Windows

For alarm systems and fault detection (equipment failures, safety events, anomaly tracking), the real-time window is defined by active event context:

Window Definition: Context buffer around active alarms (e.g., last 100 critical events and ±15 min of sensor data).

Memory Residency: HOT (in-memory Redis Stream with MAXLEN 100 events, ∼200 KB).

Transition Trigger: Alarm resolution and cooldown period.

Post-Transition: Persist alarm summary with context snippet, expire full context data.

Query Behavior: Active alarm queries use deterministic path. Forensic analysis of resolved alarms loads context from warm storage.

Hybrid Multi-Pattern Operation

A single application can maintain multiple window patterns simultaneously. For example, the CIP deployment uses:

Activity windows: Active batch monitoring (5 MB per batch, transitions on batch completion).

Time windows: Equipment health trends (500 KB for last 24 h, rolling eviction).

Event windows: Critical alarm tracking (200 KB for last 100 events, eviction on resolution).

Total real-time memory footprint: ∼5.7 MB for concurrent supervision of activity, time, and event patterns, yet supporting multi-year historical queries through transparent warm data loading from Redis AOF/RDB persistence (50–200 ms latency).

Adaptive Memory Tiering

Data residency transitions through three tiers based on window membership, as illustrated in

Figure 3:

HOT (In-Memory): Data within active real-time windows, accessed via Redis Streams/Hashes in <10 ms, supports deterministic queries without LLM overhead (e.g., “current batch temperature” → direct XRANGE query).

WARM (Disk-Backed, Auto-Load): Recently transitioned data (e.g., yesterday’s batches, previous week’s equipment health), persisted via Redis AOF (1 s durability) and RDB snapshots (5 min intervals), loaded on-demand in 50–200 ms and cached for subsequent queries.

COLD (Archived): Data beyond retention policy (e.g., >365 days), expired via TTL, manual export for regulatory purposes only.

The query router automatically detects whether a query targets HOT data (deterministic path, <10 ms, no LLM) or WARM data (analytical path, auto-load + LLM, 1–2 s total latency). Application code is unaware of this distinction; the system transparently handles data loading based on window membership checks.

Figure 3 illustrates the complete configurable window architecture, showing the three window patterns (activity-based, time-based, and event-based), the three data residency tiers (HOT, WARM, COLD), and the query routing mechanism that automatically selects between deterministic and analytical paths based on data location.

This configurable window architecture addresses a fundamental design challenge: what constitutes real-time is application-dependent. CIP batches require second-by-second monitoring during active execution, while inventory tracking may only need hourly snapshots. By decoupling window definitions from storage implementation, the architecture supports diverse industrial use cases (batch processing, continuous monitoring, alarm management) within a unified Redis-native persistence framework, achieving bounded memory consumption (5–20 MB typical) regardless of operational history depth while maintaining queryability over multi-year time ranges through automatic warm data loading.

Table 2 summarizes the window pattern configurations for different industrial applications.

3.3.6. Physical Layer Integration

The Physical Layer (bottom-right of

Figure 2) encompasses:

PLC/SCADA Systems (Cyclic Execution: 50–100 ms): Execute deterministic control loops governing valve actuation, pump operation, heating/cooling regulation, and safety interlocks. Maintain real-time control authority over physical equipment according to existing plant standards.

Industrial Process Equipment: Physical assets including reactors, heat exchangers, pumps, valves, sensors, and actuators. In the CIP deployment, this comprises cleaning circuits, chemical dosing systems, and sanitization equipment.

The architecture integrates non-invasively through:

Critically, no PLC firmware modifications or control logic rewriting are required for deployment, enabling AI-enhanced supervision in brownfield plants without triggering regulatory recertification or production downtime.

3.4. Process-Agnostic Design and Instantiation Examples

Table 3 illustrates how the same architectural components map to different batch process types, with process-specific parameters configured at deployment. The CIP case study discussed in this paper corresponds to the first instantiation column; analogous deployments for fermentation or distillation would reuse the same components with different recipes, variables and rules.

This abstraction enables the same codebase and agent logic to supervise multiple process types, with only rules, ontologies and variable mappings reconfigured per application. The CIP evaluation in

Section 6 demonstrates this pattern in production; fermentation and distillation deployments would follow the same architecture with domain-specific enrichment and diagnostic rules.

3.5. Rationale for a Layered, Agent-Based Design

Instead of deploying a single, monolithic large language model (LLM) with access to all plant data and control interfaces, the proposed architecture adopts a layered, agent-based design. This choice is motivated by several considerations:

Context management and efficiency: Industrial environments produce high-volume, heterogeneous data across multiple batch lines and equipment. Concentrating all information into a single LLM context would be inefficient and difficult to control. By separating operator interaction, orchestration and specialized agents, each component only handles the subset of data and functions relevant to its role, enabling smaller, faster contexts and more predictable behavior.

Safety and decentralization of intelligence: Safety-critical logic (e.g., interlocks, sequence enforcement, hard alarms) remains in deterministic agents and PLC/SCADA systems, while LLM-based components are confined to explanatory and analytical roles. This decentralization avoids granting a single LLM direct authority over control actions and supports explicit validation paths for any recommendation before it affects the process.

Flexibility and evolution: Food, beverage and chemical plants often operate under maquila-like conditions, with frequent product changes, contract manufacturing and evolving cleaning or processing requirements. A layered architecture with loosely coupled agents and a generic data hub allows new analysis functions, additional lines or updated recipes to be introduced without redesigning the entire system, supporting continuous adaptation and incremental deployment.

Scalability across services and sites: As production scales to multiple lines, services or sites, the same pattern can be replicated: interaction and orchestration remain similar, while additional agent instances are deployed per line or plant. This aligns with microservice and Industry 4.0 principles, enabling horizontal scale-out and reuse of components across different customers and service contracts.

In summary, the layered architecture decentralizes intelligence across specialized agents optimized for specific intentions (control, configuration, deterministic supervision, real-time analytics and offline analysis), reduces the need for large, global LLM contexts, and preserves safety and scalability in settings where processes, products and cleaning or conversion requirements evolve continuously.

3.6. Process-Aware Context Management

The decision-support layer is implemented as a set of loosely coupled agents coordinated by an orchestrator. Each agent is process-aware: upon receiving a request or detecting a new batch execution (for example, a CIP cycle, fermentation batch or distillation run), it loads the corresponding context (programme, equipment configuration, current stage, enriched variables and rule-based specifications) and subscribes to the relevant data streams. Within this context, the agent produces supervisory states, notifications, reports or language-based explanations that are specific to the active batch run.

In the CIP deployment, the context includes cleaning circuit, tank, programme, stage and key variables such as temperature, flow and conductivity. In a fermentation deployment, it would instead comprise vessel, recipe, inoculum, growth phase and variables such as pH, dissolved oxygen and biomass proxies. In distillation, it would include column configuration, feed composition and reflux schedule. This process-centric abstraction enables agents to be added or updated incrementally: new agents—whether based on rules, fuzzy logic, neural networks or large language models—can subscribe to the same process contexts and publish their outputs to the common message bus, without requiring changes to the underlying control logic or to other agents.

3.7. AI-Specific Technical Challenges and Solutions

The integration of LLM-based analytics into industrial batch supervision requires addressing several technical challenges that are specific to AI deployment in safety-critical, real-time operational environments with legacy infrastructure. This section explicitly identifies these challenges and presents the architectural solutions implemented in the proposed system to enable reliable AI-enhanced decision support in production environments.

3.7.1. Challenge 1: Non-Deterministic AI in Real-Time Safety-Critical Contexts

Problem

Large language models exhibit non-deterministic behavior due to temperature-based sampling, context-dependent inference latency (1–5 s), and potential for hallucination. Industrial batch processes require deterministic supervision with bounded response times (<100 ms for safety-critical state evaluation) and guaranteed fail-safe behavior. This timing incompatibility prevents direct integration of LLMs into control loops, as variable inference latency would violate real-time guarantees required by industrial safety standards.

Solution

The architecture enforces strict temporal domain separation (

Section 3.3) to isolate safety-critical functions from non-deterministic AI processing:

Deterministic Domain (<100 ms): Safety-critical agents (Master Controller, Deterministic Supervisor) execute rule-based logic with worst-case complexity, maintaining real-time guarantees independent of LLM availability.

Non-Deterministic Domain (1–2 s): LLM Assistant and Monitoring Service operate under relaxed timing constraints, providing advisory analytics without affecting control loops.

Safety Barrier: The Deterministic Supervisor validates all commands before actuator execution, ensuring that LLM-generated recommendations cannot trigger unsafe operations even in the event of model misbehavior or inference failure.

This architectural pattern enables LLM-based decision support to coexist with safety-critical control without compromising real-time guarantees or requiring modifications to existing PLC/SCADA logic, addressing a key deployment barrier for AI in brownfield industrial facilities.

3.7.2. Challenge 2: Bounded Context Windows for Industrial Time-Series

Problem

Industrial batch processes generate high-frequency time-series data (100–1000 ms sensor sampling) over extended execution periods (30–120 min per cycle). A typical CIP execution produces – raw data points, far exceeding the context window limits of current LLMs (4k–128k tokens). Direct consumption of raw sensor streams is computationally infeasible and semantically inappropriate: LLMs trained on natural language lack domain-specific understanding of numerical process signals (e.g., distinguishing a 2 °C temperature spike from normal thermal inertia, interpreting flow oscillations as pump cavitation vs. control valve hunting).

Solution

The Signal Enrichment Pipeline (

Section 3.3) transforms raw sensor data into semantically meaningful representations suitable for LLM reasoning:

Fuzzy Logic Transformation: Converts numerical readings into linguistic variables (“Temperature: Optimal”, “Flow: Slightly Low”) that align with natural language semantics.

Statistical Aggregation: Computes trend indicators (Stable/Increasing/Decreasing) and deviation scores over sliding windows, reducing data dimensionality by 10–100× while preserving diagnostic information.

Supervisory State Abstraction: Rule-based agents pre-compute discrete process states (NORMAL/WARNING/CRITICAL) that provide high-level context summaries, enabling LLMs to reason over process trajectories without accessing raw sensor buffers.

This enrichment strategy addresses the fundamental mismatch between industrial data formats (high-frequency numerical time-series) and LLM input representations (tokenized natural language text), enabling conversational analytics without requiring domain-specific model fine-tuning or expensive retraining on plant-specific sensor data.

3.7.3. Challenge 3: Hallucination Prevention in Safety-Critical Environments

Problem

LLMs are prone to generating plausible-sounding but factually incorrect responses when queried beyond their training distribution or when context is insufficient. In industrial settings, hallucinated diagnostic recommendations (e.g., false equipment failure predictions, incorrect procedural advice) can erode operator trust, trigger unnecessary maintenance interventions, or delay appropriate responses to genuine anomalies. Unlike consumer applications where hallucination is an inconvenience, operational decision support requires factual accuracy: incorrect diagnostics have economic consequences (unplanned downtime costs of USD 10k–USD 100k per hour in beverage/pharma plants) and safety implications.

Solution

The architecture implements a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pattern with deterministic grounding:

Context Grounding: All LLM queries are augmented with retrieved execution data (enriched time-series, supervisory states, KPI summaries) from the Data Persistence Layer, ensuring that responses reference actual process observations rather than model priors.

Deterministic Fallback: For structured queries (remaining time, stage progress, alarm counts), the Real-time Monitoring Service provides deterministic numerical answers computed via database queries, bypassing the LLM entirely when factual precision is required.

Source Attribution: LLM responses include explicit references to data sources (timestamp ranges, variable names, threshold values), enabling operators to validate claims against raw data and reject unsupported recommendations.

This grounding mechanism enables the architecture to deploy generative AI in operational contexts while mitigating the risk of confabulation in diagnostic workflows. The spot-check evaluation (

Section 6) demonstrates median absolute error below 3% between LLM-reported values and ground-truth logs, validating the effectiveness of this approach in practice.

3.7.4. Challenge 4: Resource Constraints in Edge Deployment

Problem

Industrial plants require on-premise AI deployment on edge computing infrastructure (on-premise servers, industrial PCs) with constrained computational resources (16–64 GB RAM, consumer-grade GPUs) due to data sovereignty requirements, network reliability concerns, and regulatory restrictions that preclude cloud API access. Large-scale LLMs (70B+ parameters) requiring distributed inference or cloud API access are incompatible with these constraints. This contrasts with academic AI research and commercial applications that typically assume access to high-performance computing clusters or cloud-hosted inference services.

Solution

The architecture targets locally deployable, resource-efficient LLMs:

Model Selection: Qwen 2.5 (7 billion parameters) running via Ollama provides sub-2 s inference on NVIDIA RTX GPUs while maintaining sufficient reasoning capability for diagnostic analytics.

Bounded Memory Footprint: The three-layer data persistence strategy (

Section 3.3) ensures

memory consumption per active batch (∼5 MB raw buffer + 2–10 MB enriched context), enabling concurrent supervision of multiple lines on shared infrastructure.

Asynchronous Inference: LLM queries execute in parallel with deterministic supervision, allowing model inference latency to be absorbed during operator wait times without affecting real-time control performance.

This resource-aware design demonstrates that effective LLM-based decision support does not require frontier model scale, enabling deployment in resource-constrained industrial environments typical of brownfield facilities.

3.7.5. Summary: AI-Specific Contributions

The proposed architecture addresses four fundamental technical challenges that arise specifically from the integration of non-deterministic, context-limited, hallucination-prone generative AI into safety-critical, real-time, resource-constrained industrial environments:

Temporal domain separation to preserve real-time safety guarantees despite non-deterministic AI components.

Signal enrichment pipelines to bridge the semantic gap between numerical process data and natural language LLM inputs.

RAG-based grounding to prevent hallucination and ensure factual accuracy in diagnostic recommendations.

Resource-efficient deployment to enable local inference under edge computing constraints.

These solutions constitute contributions to the intersection of industrial automation and AI, demonstrating how LLM-based decision support can be deployed in production environments with legacy infrastructure, safety requirements, and resource constraints that distinguish industrial contexts from the controlled laboratory or cloud-based settings typical of AI research.

4. Real-Time Data Management and LLM Integration

The proposed architecture explicitly balances memory usage, query latency and quality of assistance by combining compact, enriched data buffers with decentralized analysis agents that support both immediate supervisory decisions and longitudinal trend analysis for preventive maintenance.

4.1. Bounded In-Memory Buffers and Latency

Each active CIP instance maintains an in-memory buffer with a configurable maximum number of records (MAXLEN policy), corresponding to a few hours of operation at the given sampling rate, instead of persisting the entire plant history in the LLM context. This rolling dataset is exposed through multiple logical windows: a short horizon (e.g., last 2 min) for real-time state estimation, a medium horizon (e.g., last 5–10 min) for periodic diagnostics and preventive warning detection, and a full-cycle view for exploratory real-time queries, cross-cycle trend analysis and offline post-run analysis. By keeping buffer size bounded, deterministic statistics and LLM prompts can be computed with near-constant time and memory, even as the plant scales to more CIP circuits or higher sampling frequencies.

4.2. Enriched, Decentralized Data Views

Incoming sensor records are enriched in real time with additional attributes such as CIP program and stage labels, elapsed and remaining time, progression percentage, fuzzy quality indices and short textual descriptors of detected issues, recommended actions and maintenance implications. These enriched records are partitioned per CIP instance and per agent, so that each agent only receives the subset of variables needed for its function (e.g., deterministic supervision windows for immediate alerts, real-time analytics buffers for diagnostic interpretation, offline archives for longitudinal trend correlation with maintenance records), avoiding a single centralized, monolithic dataset. This decentralization reduces contention and enables real-time support for diagnostics, preventive warning generation and maintenance-oriented decisions at the agent level, while still allowing higher-level aggregation when required for cross-cycle trend analysis.

4.3. Compact LLM Contexts and Efficient Queries

To avoid high latency and cost, the LLM never receives raw, unfiltered streams; instead, the real-time analytics agent constructs compact prompts that combine aggregate statistics over the relevant window, a small set of representative samples (e.g., most recent records or identified outliers) and contextual metadata such as program, stage, circuit and recent alert patterns. This strategy keeps context size small and stable while preserving the information required for meaningful explanations, diagnostic pattern recognition and preventive maintenance recommendations, making it feasible to answer natural-language queries with response times compatible with operator workflows in real plants. The integration layer treats the LLM as a pluggable component accessed through a uniform API, so different on-premise or cloud models can be used without changing the surrounding data management strategy.

4.4. Lowering the Expertise Barrier for Real-Time Decisions and Maintenance Planning

Because diagnostic windows and enriched attributes are computed deterministically and exposed in structured form, operators receive interpretable summaries (e.g., state class, quality grade, main issues, suggested actions and maintenance implications) without having to interpret raw trends or write complex analytical queries. The LLM layer then builds on these structured diagnostics to provide natural-language explanations, cross-cycle trend comparisons and preventive maintenance recommendations, allowing less specialized staff to understand CIP performance, identify emerging equipment degradation patterns and take timely decisions without requiring deep training in control theory, statistical analysis or maintenance planning. This combination of bounded, enriched buffers and layered LLM integration directly supports real-time analysis, diagnostic interpretation and maintenance-oriented decision support in complex industrial environments while keeping computational and training costs under control.

4.5. Illustrative Data Views and Query Profiles

Table 4 summarizes the main data windows maintained per CIP instance and their intended use while

Table 5 illustrates typical query types, underlying sources and expected response times.

4.6. Fuzzy Enrichment of Real-Time CIP Data

Raw CIP sensor readings alone (e.g., temperature, flow, conductivity, volume) are often difficult to interpret directly in the control room, especially when multiple variables must be considered simultaneously or when subtle degradation patterns must be distinguished from normal process variability. To provide operators and downstream agents with more actionable information, the system applies a fuzzy evaluation layer in real time, which maps continuous variables and their deviations from nominal profiles into linguistic assessments, quality indices and maintenance-oriented diagnostic labels.

For each time-stamped record, the enrichment pipeline:

normalizes the raw measurements with respect to the target CIP program and current stage (e.g., expected temperature, flow and conductivity ranges for an alkaline wash);

evaluates a set of fuzzy rules that capture expert knowledge, such as “temperature slightly low but within tolerance” or “flow persistently below minimum, suggesting pump wear”, combining multiple variables and short-term trends; and

outputs a discrete state label (e.g., NORMAL, WARNING, CRITICAL), a continuous quality grade in , and short textual descriptors summarizing the main issues, recommended actions and maintenance implications.

The resulting enriched record contains, in addition to the raw sensor values and timestamps, fields such as

stage,

progress_percent,

remaining_time,

state,

quality_grade,

motives and

actions, as well as equipment and circuit identifiers and auxiliary counters (e.g., number of recent warnings or critical samples).

Table 6 shows a simplified example of such a record.

From a resource perspective, the bounded-buffer design keeps the memory footprint per CIP instance relatively small: for example, a buffer of – records with a dozen numeric and categorical fields typically remains in the order of a few megabytes in memory, even when multiple CIP lines are monitored concurrently. This is modest compared to the memory requirements of the LLM itself and allows deterministic statistics and prompt construction to execute with predictable latency. At the same time, the enriched representation and pre-computed diagnostics provide enough information for operators to take online decisions directly from the generated summaries and explanations, including identification of preventive maintenance opportunities and equipment health trends, without resorting to external tools or manual data export. In practice, this combination of low in-memory cost and high decision support value—spanning immediate supervisory needs and longer-term diagnostic interpretation—is essential for deploying AI-assisted supervision in industrial environments where hardware resources and real-time constraints are non-negotiable.

4.7. Computational Resource Profile

Table 7 summarizes the computational footprint of the main system components in the deployed configuration. The memory requirements per CIP instance remain modest (order of a few megabytes for the enriched buffer), while the LLM service (Qwen 2.5 7B via Ollama) operates as a shared resource across all active CIP lines, with inference latencies compatible with interactive operator workflows and real-time diagnostic queries.

Because the LLM runs locally on NVIDIA GPU infrastructure, query latencies remain predictable and do not depend on external cloud API availability or network conditions. This edge deployment strategy addresses the computational and energy constraints inherent in cloud-based LLM architectures for IIoT environments [

41] while maintaining data sovereignty and reducing communication overhead. Recent work on edge-cloud collaboration for LLM task offloading in industrial settings has demonstrated that local inference can reduce latency by 60–80% compared to cloud-based alternatives [

41], supporting the architectural decision to deploy Qwen 2.5:7B on dedicated GPU infrastructure rather than relying on external API services.

5. Evaluation Methodology

5.1. Evaluation Objectives

This study evaluates the architectural feasibility and operational capability of the proposed hybrid AI framework in a real industrial environment, rather than pursuing large-scale statistical validation of process performance improvements.

Accordingly, the evaluation focuses on how the decision-support layer behaves when exposed to authentic CIP executions, and whether it fulfils its intended role as a real-time, operator-oriented supervisory layer that supports diagnostic interpretation and preventive maintenance planning. The study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: Can the architecture maintain coherent supervisory states across diverse CIP conditions?

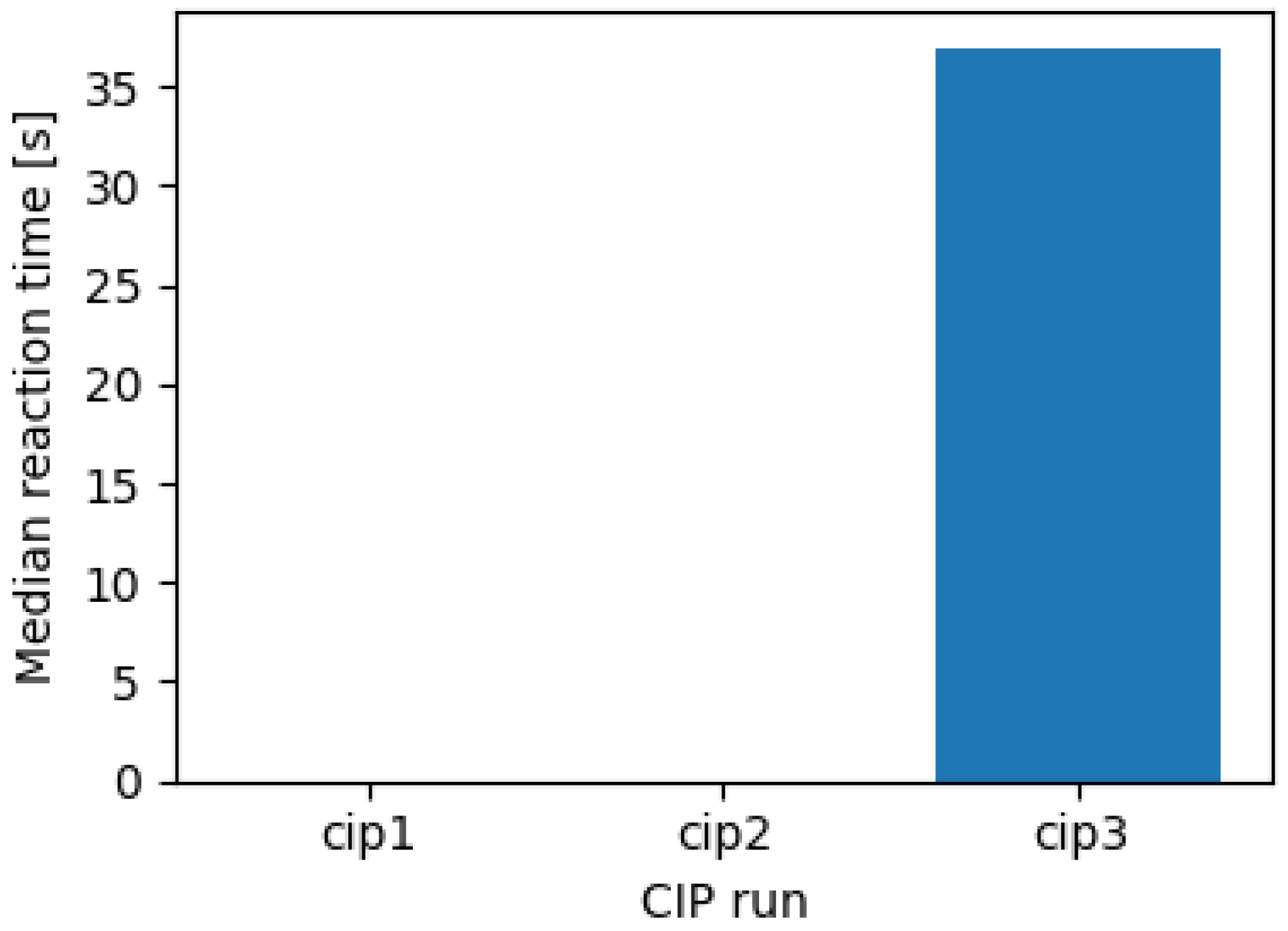

RQ2: Do the agents respond within application-level real-time constraints during production operation?

RQ3: Does the LLM-based analytics layer provide grounded, numerically consistent explanations over enriched process data?

RQ4: Is the system deployable and operable in an actual CIP installation without disrupting existing PLC/SCADA programmes?

RQ5: Can the architecture differentiate nominal, preventive and diagnostic alert patterns in a way that is meaningful for maintenance decision-making?

The primary goal is thus to demonstrate that the architecture can be instantiated, operated and queried in a working plant, and that its supervisory outputs remain coherent, stable, data-grounded and diagnostically useful over complete CIP executions.

5.2. Case Selection Rationale

Rather than sampling a large number of nearly identical cycles, the evaluation adopts a case study approach using three representative CIP executions drawn from ongoing production at the VivaWild Beverages plant. These executions were selected to span the typical operational envelope observed in day-to-day operation and to illustrate complementary diagnostic scenarios: (a) a fully nominal baseline, (b) executions with preventive warnings that do not compromise stage success, and (c) executions with more pronounced deviations that generate diagnostic alerts under operational stress.

These three executions were purposively selected from 24 complete CIP runs monitored by the system during a six-month deployment period at the VivaWild Beverages plant. The selection criterion was to span the diagnostic spectrum observed during deployment: nominal baseline, preventive warning patterns, and diagnostic alert conditions that remain operationally successful but provide evidence of the architecture’s ability to differentiate equipment health states meaningful for maintenance planning.

Table 8 summarizes the three selected cases and their respective diagnostic rationales.

These cases are representative of normal plant operation. The CIP process at VivaWild is governed by standard operating procedures, automated recipe management and regulatory constraints, and exhibits high repeatability across executions in terms of temperature, flow and conductivity profiles.