Abstract

Background: This retrospective cohort study developed an artificial intelligence (AI) model to predict incident dementia and evaluated its predictive performance using a validation cohort. The study participants were 7384 older adults (age ≥ 75 years) who underwent regional dental checkup in Gifu Prefecture, Japan, in 2018 and 2020. Methods: The National Database of Health Insurance of Japan (NDB) was integrated with dental checkup data, and the participants were randomly divided into two datasets: training (n = 5169) and validation (n = 2215). A data analytics tool was utilized to create the AI model with training data in 2018 and data on the presence or absence of dementia development in 2020. Results: The AI model trained solely on NDB data showed a sensitivity of 0.73 and specificity of 0.91 in predicting the presence or absence of dementia development after 2 years. By contrast, the AI model trained on NDB and dental checkup data showed a sensitivity of 0.75 and specificity of 0.95, indicating improvement in both metrics. Conclusions: Combining different sets of data, such as NDB and dental checkup data, for training may be useful for improving the accuracy of AI models to predict dementia development.

1. Introduction

Dementia is a condition characterized by irreversible decline in intellectual and cognitive abilities resulting from acquired organic brain damage [1]. In the early stages, it is often confused with age-related forgetfulness, but memory impairment, disorientation, and cognitive dysfunction become more pronounced as symptoms progress [2,3]. In Japan, approximately 20% of older adults (age ≥ 75 years) had dementia in 2020, with the proportion increasing annually, making it a major aging-associated physical and mental disorder [4]. Dementia progresses irreversibly [5], and a fundamental cure has yet to be developed [6]. Therefore, countermeasures should focus on predicting when dementia will develop and rapidly seeking preventive strategies rather than interventions after development.

In recent years, various artificial intelligence (AI) models have been developed with the aim of predicting disease development [7,8]. In the field of dementia, techniques that analyze patients’ speech patterns to diagnose early symptoms of dementia have been reported [9,10], as have practical applications of AI models that diagnose dementia from imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and positron emission tomography [11]. However, these models focus on how early a diagnosis can be made for patients who have already developed dementia; how useful AI models can be for preventive measures before dementia develops remains unclear.

Previous reports have indicated that dementia is associated with various diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia [12,13,14], as well as oral health conditions such as tooth loss and periodontal disease [15,16,17]. Therefore, an individual’s medical and oral health conditions may be useful for predicting future dementia development.

Against this background, Sony Network Communications (Tokyo, Japan) released Prediction One® Version 1.3 (SONY 2021), a software program that automatically creates AI models using existing data [18,19,20]. In Japan, the National Health Insurance Database (NDB) provides information on people with dementia or other medical conditions [21,22,23]. In addition, regional dental checkup (GIFU SAWAYAKA Oral Checkup) are conducted once a year for older adults in Gifu Prefecture [21,22], with the results also stored in a database. Because existing data such as those from the NDB and dental checkup can be utilized, an AI model using Prediction One® may be able to predict dementia development. Therefore, in the present study, we developed and evaluated accuracy of an AI model using Prediction One® to predict dementia development after 2 years based on NDB or dental checkup data in Japanese older adults who had undergone regional dental checkup in Gifu.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective cohort study targeted older adults residing in Gifu Prefecture. Using NDB and dental checkup data acquired in fiscal year (FY) 2018 (April 2018 to March 2019) as the baseline, we tracked the occurrence of dementia through FY 2020 (April 2020 to March 2021) to construct and validate an AI prediction model.

2.1. Participants

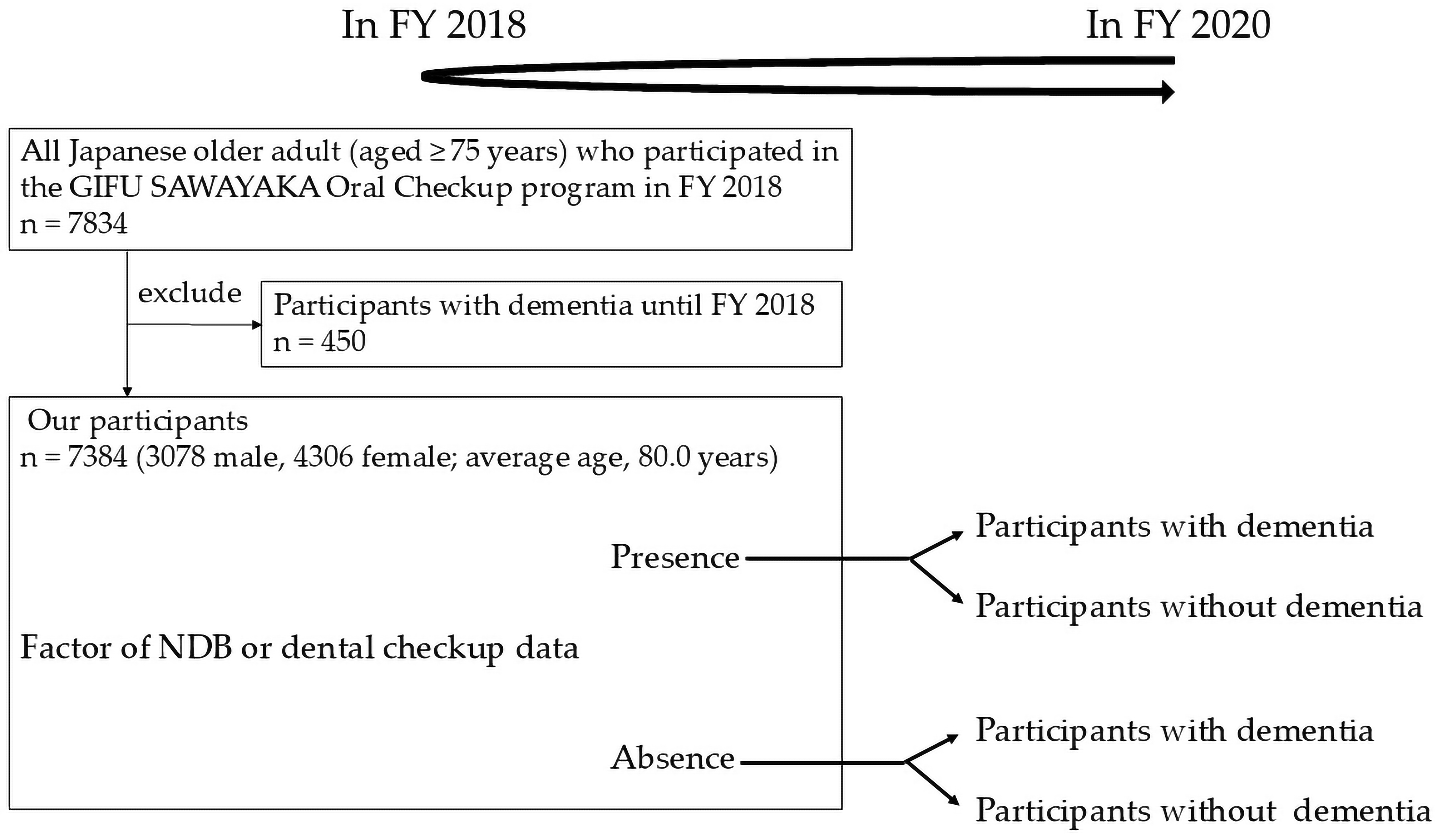

A total of 7834 Japanese older participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) older adult (aged ≥ 75 years) who participated in the GIFU SAWAYAKA Oral Checkup program in FY 2018, (2) individuals for whom NDB data from FY 2018 were obtainable, and (3) individuals for whom dementia development could be tracked in the NDB in FY 2020. Among these individuals, 450 already diagnosed with dementia by FY 2018 were excluded. As a result, 7384 participants (3078 male, 4306 female; average age, 80.0 years) were included in the analysis. This study employed a census survey method, registering all eligible individuals in the target area, and no prior sample size calculation was performed. In addition, follow-up was possible for all subjects using the 2020 NDB data; therefore, no subjects were lost to follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of our study.

2.2. Development of the AI Model

The primary outcome measure in the present study was whether participants received a new diagnosis of dementia between FY 2018 and FY 2020. Dementia diagnoses were extracted from medical facility visit data recorded in the NDB and defined based on the presence or absence of corresponding codes for dementia from the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Next, NDB and dental checkup data were integrated and individual data were randomly assigned to a training dataset (n = 5169) and a validation dataset (n = 2215) using the systematic sampling method. An AI model was created from the training group using Prediction One® (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) based on 2018 NDB data and 2018 dental checkup data, in addition to data from participants newly diagnosed with dementia before 2020.

2.3. Survey Items in the NDB

We obtained information on gender, age, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, musculoskeletal disease, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), support/care-need certification, and medication history from the NDB [21,24].

2.4. Assessment of Body Composition

A nurse measured the participants’ height and weight. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2) [25].

2.5. Assessment of Serum Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Levels

Serum HbA1c in venous blood collected after an overnight fast was measured using high-performance liquid chromatography [26].

2.6. Smoking Habit, Exercise Habit, Weight Loss, Going out, and Oral Items

Data on smoking habits, exercise habits, weight loss, going out habits, and oral items were obtained as follows: presence or absence of regular dental checkup, brushing frequency ≥ twice/day, presence or absence of using of interdental brushes/dental floss, presence or absence of difficulty in biting hard food, presence or absence of choking on tea and water, presence or absence of dry mouth, presence or absence of ≥20 teeth, presence or absence of decayed teeth, presence or absence of periodontal pocket depth ≥ 4 mm, presence or absence of ill-fitting dentures, presence or absence of tongue coating, presence or absence of halitosis, poor or good tongue and lip function, poor or good swallowing function, and poor or good oral hygiene. The oral items were provided by Gifu Dental Association, Japan.

Presence of smoking habits was defined as smoking at least one cigarette per day [27]. Presence of exercise habits was defined as engaging in light exercise (≥30 min) more than twice/week for ≥1 year [28]. Presence of weight loss was defined as having lost ≥2–3 kg/6 months [29]. Presence of going out was defined as going out at least once a week [28,29]. Presence of regular dental checkup was defined as having visited a dental clinic at least once/6 months [30]. The participants were asked to select “yes” or “no” for the following items on a self-administered questionnaire: “Difficulty in biting hard food”, “Choking on tea and water”, and “Dry mouth” [22]. Number of present teeth, decayed teeth, periodontal pocket depth, ill-fitting dentures, tongue coating, halitosis, tongue and lip function, swallowing function, and oral hygiene were documented by dentists. For the assessment of a periodontal pocket ≥ 4 mm, the coded values of the Community Periodontal Index were used, with periodontal pocket codes 1 and 2 evaluated as a periodontal pocket depth ≥ 4 mm [31]. Participants were classified in regard to fitting dentures (good, poor, fracture), tongue coating (minimal, moderate, heavy), and halitosis (minimal, moderate, heavy). Participants indicating poor or fracture were classified as having ill-fitting dentures, those indicating moderate or heavy were classified as presence of tongue coating, and those indicating moderate or heavy were classified as presence of halitosis. Tongue and lip function were assessed using the oral diadochokinesis test, with poor tongue and lip function defined as producing fewer than 30 syllables (“pa,” “ta,” or “ka”) within 5 s [32]. Swallowing function was assessed using the repeated saliva swallowing test, with poor swallowing function defined as swallowing fewer than three times within 30 s [33]. Participants were also classified in regard to dental plaque (minimal, moderate, heavy). Those indicating moderate or heavy were classified as having poor oral hygiene [34].

2.7. Internal AUC Reported by the Software and Variable Contribution

During model creation, Prediction One® automatically outputs an internal area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and a measure of each variable’s contribution to prediction [18]. This internally reported AUC is provided by the software as a reference indicator during model development and is distinct from the outcome-based performance metrics evaluated using the independent validation dataset. Variable contribution level is quantified by the reduction in the software-reported AUC when a given variable is removed from the model; larger decreases indicate greater contribution within the dataset used [18,35]. In our study, software versions were managed using a centralized version control system, with all versions stored in a central repository on a server. For missing values, the software automatically assigns “missing” rather than imputing “0” when creating the model. Data preprocessing and model development were performed using an automated machine-learning workflow. Hyperparameter optimization was performed automatically using built-in procedures, including grid search, random search, and Bayesian optimization.

2.8. Evaluation of AI Model Accuracy Using Validation Data

We used the AI model to predict dementia development after 2 years based on verification data from 2018 and evaluated its relationship with actual measurements. Specifically, we calculated the sensitivity (number of individuals predicted to develop dementia by the AI model/number of individuals who actually developed dementia) and specificity (number of individuals predicted not to develop dementia by the AI model/number of individuals who actually did not develop dementia) regarding dementia development after 2 years. We also evaluated positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy, balanced accuracy, F1-score, matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), and validation prevalence. Additionally, to illustrate a representative operating point, we identified the probability threshold corresponding to the maximum Youden’s J statistic (sensitivity + specificity − 1) on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. This threshold was used solely to report binary performance metrics for transparency, while overall model performance was primarily evaluated using threshold-independent measures.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data normality was assessed using the Lilliefors test. Because all continuous variables were not normally distributed, the data were expressed as the median (first and third quartiles). We divided the participants into two data groups: training and validation. For the between-group comparisons of each factor, we used the chi-square test and the Mann–Whitney U test. All data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics (Version 27; IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). p-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

2.10. Research Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Asahi University (No. 33006) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Brazil 2013). As the data from the NDB and dental checkup were anonymous, informed consent was not considered necessary.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants in the training and validation data groups. No significant differences in any of the factors set in our study were observed between the two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants in the training and validation data groups.

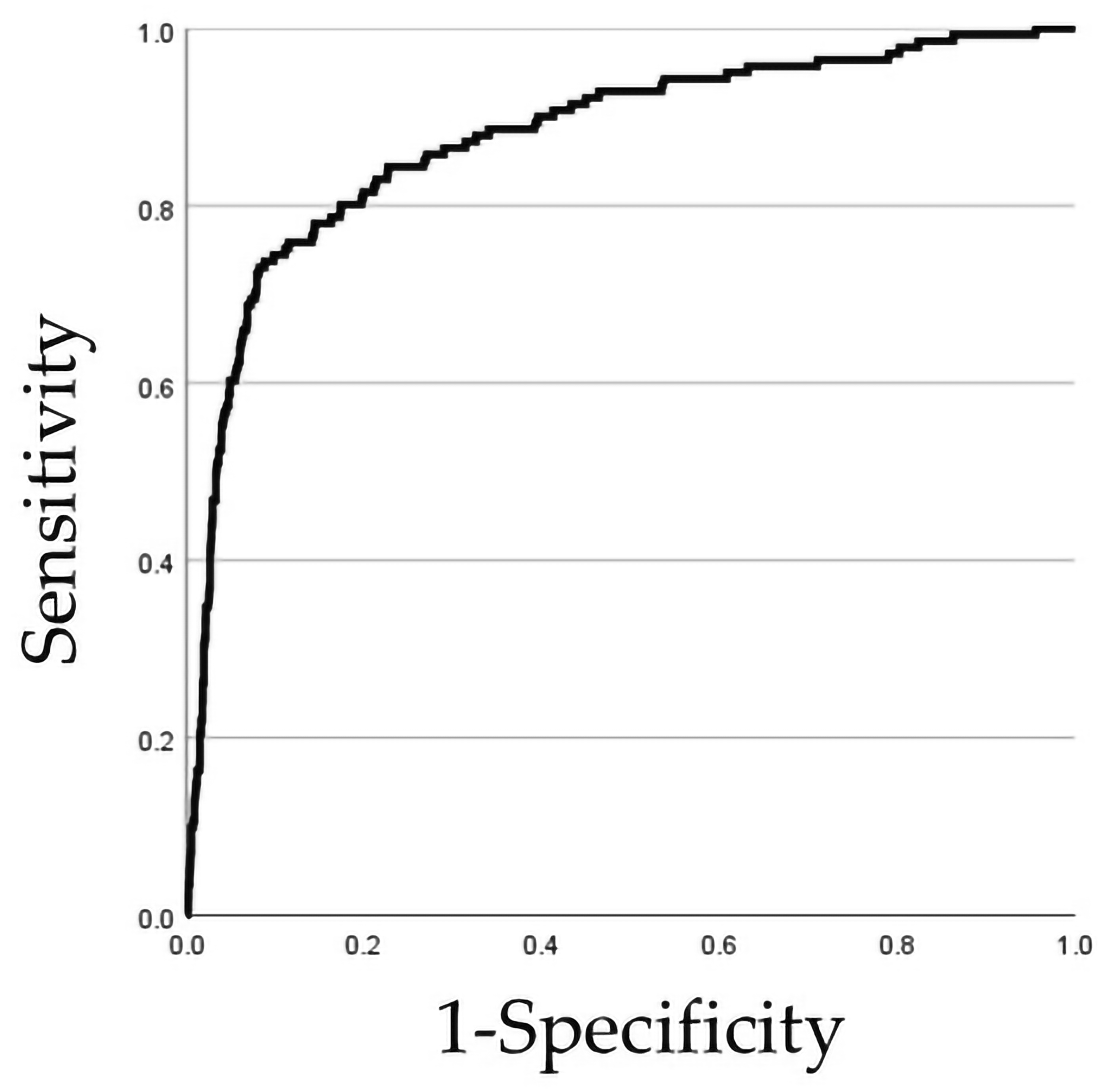

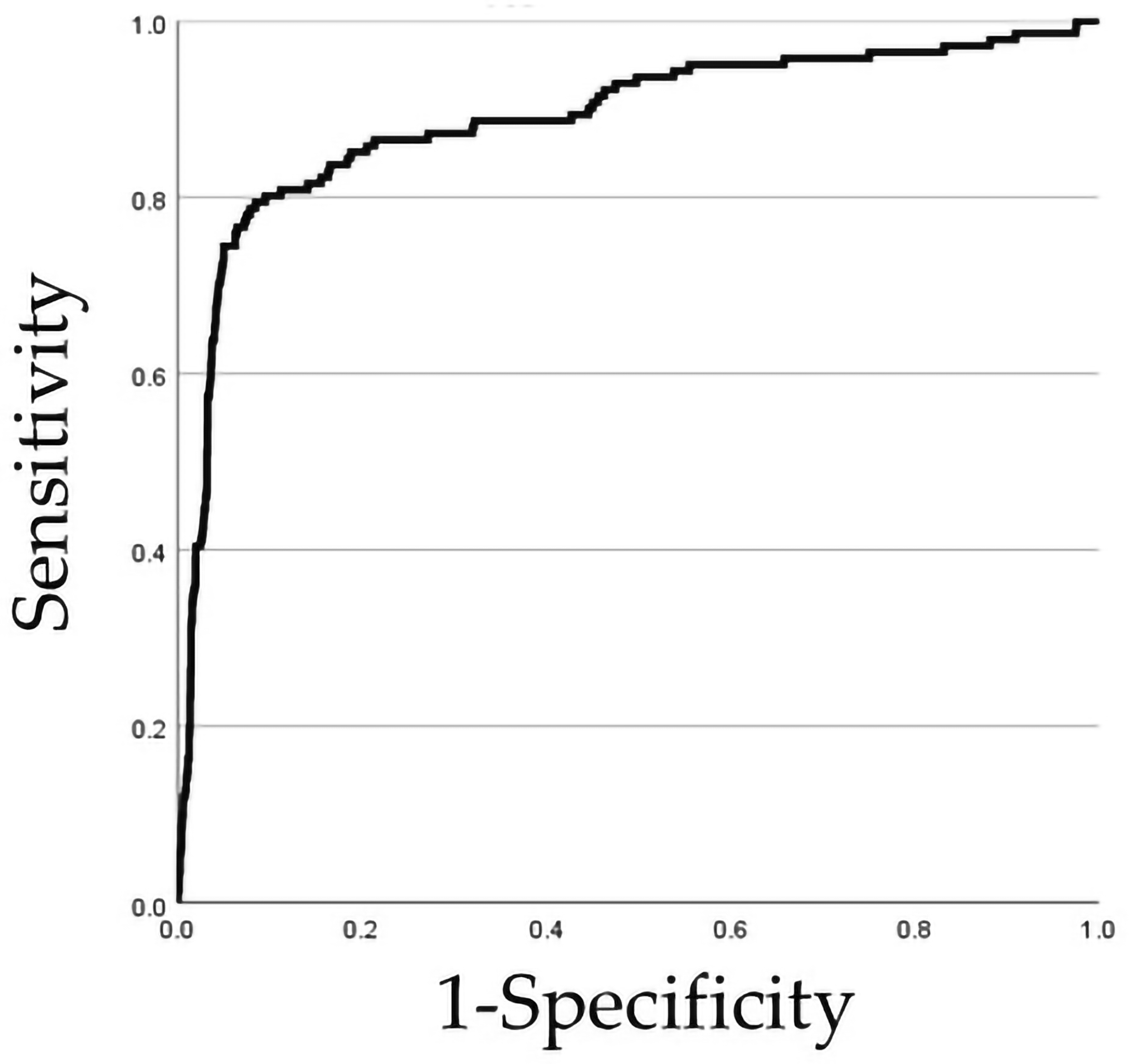

Table 2 and Table 3, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the relationships between the prediction and actual occurrence of dementia development in the AI model. In total, 141 participants (6%) were newly diagnosed with dementia after 2 years.

Table 2.

Relationship between the prediction of the presence or absence of dementia development in AI models trained solely on NDB data and the actual occurrence of the presence or absence of dementia development (n = 2215).

Table 3.

Relationship between the prediction of the presence or absence of dementia development in the AI model trained using NDB and dental checkup data, and the actual occurrence of the presence or absence of dementia development (n = 2215).

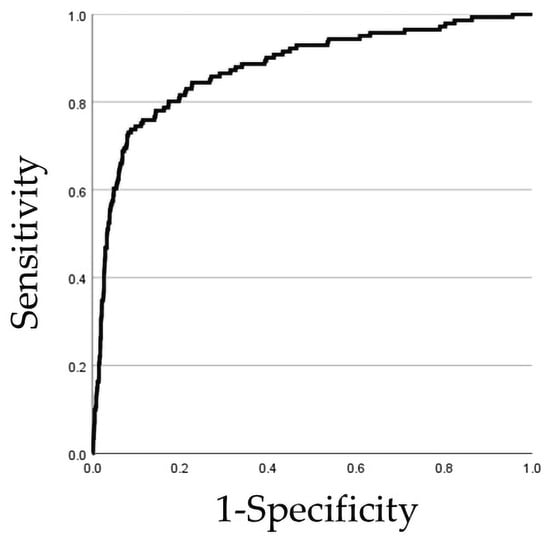

Figure 2.

ROC curve in AI models trained solely using NDB data.

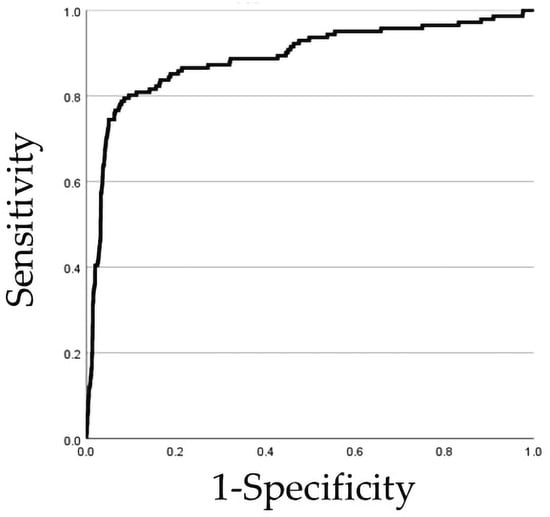

Figure 3.

ROC curve in AI models trained using NDB and dental checkup data.

In Table 2 and Figure 2, we used an AI model trained solely on data from the NDB. This AI model predicted that 73.0% (95% confidence intervals [CIs], 64.9–80.2) of the participants with the presence of actual occurrence of dementia development after 2 years would develop dementia (sensitivity, 0.730; 103/141). Furthermore, it predicted that 91.4% (95% CIs, 90.1–92.6) of the participants with the absence of actual occurrence of dementia development after 2 years would not develop dementia (specificity, 0.914; 1896/2074). In addition, the AI model trained solely on NDB had PPV of 36.7% (95% CIs, 31.0–42.6), NPV of 98.0% (95% CIs, 97.3–98.6), accuracy of 90.2% (95% CIs, 88.9–91.5), balanced accuracy of 82.2%; F1-score of 0.488, MCC of 0.473, validation prevalence of 6.4%, and false positives of 178 participants. Furthermore, Prediction One® calculated the prediction AUC of the AI model to be 77.3%. Furthermore, based on the ROC curve results when using this AI model, area under the curve (AUC) was calculated as 0.878 (95% CIs, 0.844–0.911), and the illustrative operating threshold (corresponding to the maximum Youden’s J on the ROC curve) was set to 0.11910800.

In Table 3 and Figure 3, we used an AI model trained using NDB and dental checkup data. This AI model predicted that 74.5% (95% CIs, 66.4–81.4) of the participants with the presence of actual occurrence of dementia development after 2 years would develop dementia (sensitivity, 0.745; 105/141). Furthermore, it predicted that 94.9% (95% CIs, 93.9–95.8) of the participants with the absence of actual occurrence of dementia development after 2 years would not develop dementia (specificity, 0.949; 1968/2074). In addition, the AI model trained using NDB and dental checkup data PPV of 49.8% (95% CIs, 42.8–56.7), NPV of 98.2% (95% CIs, 97.5–98.7), accuracy of 93.6% (95% CIs, 92.5–94.6), balanced accuracy of 84.7%; F1-score of 0.597, MCC of 0.577, validation prevalence of 6.4%, and false positives of 106 participants. Furthermore, Prediction One® calculated the prediction AUC of this AI model to be 79.0%. Furthermore, based on the ROC curve results when using this AI model, the AUC was calculated as 0.889 (95% CIs, 0.854–0.924), and the illustrative operating thresholds (corresponding to the maximum Youden’s J on the ROC curve) were 0.09290100 or 0.09523750.

Table 4 and Table 5 show the top 10 factors among the learned factors that contributed to the AUC growth in the AI model’s prediction of dementia development after 2 years, along with the impact of including or excluding each item on sensitivity, 1-specificity, and AUC. In the AI model trained solely on NDB, the factors contributing to the prediction of dementia development after 2 years, listed in order of decreasing AUC growth value (contribution rank), were as follows: support/care-need certification (support-need certification ≥ 2; AUC growth value, 0.0742), HbA1c level (%) (≥8.0; AUC growth value, 0.0202), musculoskeletal disease (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0137), pneumonia (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0122), hypertension (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0115), BMI (kg/m2) (≤20.0; AUC growth value, 0.0114), age (years) (≥86; AUC growth value, 0.0109), COPD (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0106), gender (female; AUC growth value, 0.00080), and diabetes (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0068) (Table 4). In the AI model trained using NDB and dental checkup data, the factors contributing to the prediction of dementia development after 2 years, listed in order of decreasing AUC growth value, were as follows: support/care-need certification (support-need certification ≥ 2; AUC growth value, 0.0547), pneumonia (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0213), use of interdental brushes/dental floss (absence; AUC growth value, 0.0149), HbA1c level (%) (≥8.0; AUC growth value, 0.0130), regular dental checkup (absence; contribution levels, 0.0119), swallowing function (poor; AUC growth value, 0.0111), choking on tea and water (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0100), musculoskeletal diseases (presence; AUC growth value, 0.0097), gender (female; AUC growth value, 0.0088), and age (years) (≥86; AUC growth value, 0.0087) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Top 10 factors contributing to the AUC growth in the prediction of dementia development in the AI model trained solely on NDB data, along with the impact of including or excluding each item on sensitivity, 1-specificity, and AUC.

Table 5.

Top 10 factors contributing to the AUC growth in the prediction of dementia development in the AI model trained using NDB and dental checkup data, along with the impact of including or excluding each item on sensitivity, 1-specificity, and AUC.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate accuracy of an AI model to predict dementia development using dental checkup data in Japanese older adults aged ≥ 75 years. The results show that the AI model trained solely on NDB data predicted participants who actually developed dementia after 2 years with a sensitivity of 73.0% (95% CIs, 64.9–80.2) and predicted participants who did not develop dementia after 2 years with a specificity of 91.4% (95% CIs, 90.1–92.6). Furthermore, the PPV of the AI model trained solely on NDB was 36.7% (95% CIs: 31.0–42.6), the NPV was 98.0% (95% CIs: 97.3–98.6), the F-score was 0.488, and AUC was 0.878 (95% CIs, 0.844–0.911). Moreover, the AI model trained using NDB and dental examination data predicted participants who actually developed dementia after 2 years with a sensitivity of 74.5% (95% CIs: 66.4–81.4) and predicted participants who did not actually develop dementia after 2 years with a specificity of 94.9% (95% CIs: 93.9–95.8). Furthermore, the AI model trained using NDB and dental checkup data showed a PPV of 49.8% (95% CIs: 42.8–56.7), a NPV of 98.2% (95% CIs: 97.5–98.7), the F-score of 0.597, and AUC was 0.889 (95% CIs, 0.854–0.924). In other words, incorporating dental information alongside NDB data when creating the AI model improved the model’s sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, F-score, AUC, and overall accuracy. Furthermore, adding dental examination data reduced false positives (NDB alone: 178 cases, NDB + dental checkup data: 106 cases). These findings suggest that incorporating dental information into AI models is effective for more accurately predicting dementia development.

On the other hand, while incorporating dental checkup data into the NDB training dataset improved the accuracy of the AI model, the sensitivity remained <80%. This suggests that the model should not be interpreted as a diagnostic or screening tool. Rather, it may be more appropriately positioned as a risk stratification or risk prioritization tool to inform downstream attention or triage, while further refinement and external validation are needed. Furthermore, in our study, the threshold for our AI model derived from the ROC curve was determined to be 0.119108 when trained solely on NDB, and 0.09290100 and 0.09523750 when trained on NDB and dental examination data. In practice, the choice of threshold should be prespecified according to the intended use case (e.g., prioritizing sensitivity for rule-out vs. prioritizing PPV to reduce unnecessary follow-up). In this study, thresholds are reported to transparently illustrate performance at a representative operating point, rather than to propose a prespecified clinical decision rule. Furthermore, Prediction One® can create more accurate AI models by training based on a larger number of participants and disease-related factors [36,37]. It has been reported that dementia development is associated with factors beyond those discussed in the present study, including hyperthyroidism [38], mental disorders [38], alcohol dependence status [39], and socioeconomic indicators such as income and education levels [40]. Future efforts will aim to build more accurate AI models by incorporating these factors into the training dataset. In this way, in our study, we demonstrated that adding dental information to AI model during training not only improved sensitivity, specificity, and AUC but also yielded clinically meaningful results by reducing false positives. Furthermore, AI model developed in our study created of the linked data resource that can be further refined in the future. These aspects collectively highlight the novelty of our study.

In our study, the prediction AUC automatically calculated by Prediction One® showed a value of 77.3% when trained solely using NDB data. Furthermore, when trained using NDB and dental checkup data, it showed a value of 79.0%, indicating improved prediction AUC. Sony Network Communications, the distributor of Prediction One®, provides the following prediction AUC level benchmarks for AI model: a = AUC level benchmarks, “a < 63%: Low accuracy,” “63% ≤ a < 74%: Standard accuracy” and “74% ≤ a: High accuracy” [41]. This indicates that the AI model developed in the present study has high prediction AUC. Furthermore, combining NDB and dental checkup data for training suggests that AI models with higher AUC can be created.

In this study, 70% of the total data was allocated as training data. In a previous study that created an AI model to predict subarachnoid hemorrhage outcomes using Prediction One®, 67% of the total data was allocated as training data [18]. Furthermore, a study that created an AI model to predict blood urea nitrogen levels after dialysis using Shapley Additive Explanations utilized 70% of the total data for training data [36]. Thus, the allocation of training and validation data in our study was performed in accordance with previous studies.

In the AI model developed in the present study, when trained solely on NDB data as the factor contributing to the AUC growth in predicting dementia development, the order of contribution magnitude was as follows: support/care-need certification (support-need certification ≥ 2), HbA1c level (%) (≥8.0), musculoskeletal disease (presence), pneumonia (presence), hypertension (presence), BMI (kg/m2) (≤20.0), age (years) (≥86), COPD (presence), gender (female), and diabetes (presence). Furthermore, when trained on both NDB and dental checkup data, dental factors such as the use of an interdental brush/dental floss (absence), regular dental checkup (absence), swallowing function (poor), and choking on tea and water (presence) were among the top 10 factors contributing to AUC. A previous study has reported that higher rates of dental floss use and dental visits are associated with a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, and that oral self-care behaviors are linked to cognitive decline [42]. The risk of dementia development has also been associated with poor swallowing function [43] and choking [44]. Cognitive decline is associated with impaired swallowing function through its links to motor impairments such as muscle weakness and apraxia, as well as reduced appetite and food avoidance [43]. Furthermore, dementia may impair feeding behavior functions and interfere with the anticipatory and oral preparation phases of chewing and swallowing, potentially contributing to choking and swallowing dysfunction [44]. Therefore, the predictive results of this study support prior research. However, the top-ranked predictors (such as support-need certification, pneumonia, musculoskeletal disease, swallowing function, and choking may represent frailty, functional decline, or preclinical neurocognitive changes rather than direct mechanisms related to oral health. Dental-related variables may also contribute as indicators of systemic frailty and other common risk pathways through oral function. Furthermore, the contribution ranking of the AUC growth in predictive variables indicates predictive utility within this dataset and should not be interpreted as causation. Consequently, these factors should be interpreted as important predictors or associated factors rather than definitive causal determinants of dementia development.

The social contribution of our study lies in constructing AI model for predicting dementia development by linking administrative medical databases for older adults (age ≥ 75 years) with community dental checkup data, and verifying its accuracy. Furthermore, it demonstrated that incorporating dental factors assessed during dental checkup into the model contributed to improved accuracy in predicting dementia development after 2 years. In Japan, as of 2022, the proportion of older adults with dementia is 23.6% among those aged 75–79 years, 39.2% among those aged 80–85 years, and 60.3% among those aged 86–90 years [45]. Furthermore, according to the Annual Report on the Ageing Society in 2024, the number (proportion) of older adults with dementia in Japan is expected to increase to approximately 10.35 million (28.3%) in 2025, 11.16 million (30.2%) in 2030, and 11.73 million (31.1%) in 2035 [46]. This indicates that the incidence of dementia is expected to continue rising across all age groups of older adults aged ≥ 75 years. Conducting “future dementia development prediction” for participants who undergo regular dental checkup and raising awareness could be effective in helping to prevent the increase in dementia development among older adults. Furthermore, based on the results of the present study, using an AI model as a tool for predicting future dementia development is considered effective.

In our study, AI-integrated biomedical system is positioned as follows for creating an AI model to predict dementia development. As optimization within the AI-integrated biomedical system, incorporating dental information into the factors trained by AI achieved optimization of the false positive rate. This enables optimization of the medical workflow (triage) following dental checkup. Furthermore, as system-level modeling, treating the AI model and medical processes as an integrated whole ensures safety during health guidance provided to participants after screening. Additionally, our study targets a different use case: predicting population-level risk based on NDB and dental checkup data, rather than simulations based on physical laws.

This study has several limitations. First, because this study used NDB data, the presence of diseases not included in the database is unknown. Second, while Prediction One® calculates the magnitude of each factor’s contribution, it does not establish a benchmark for this magnitude. Setting a benchmark for the magnitude of contribution is useful in examining the impact on disease development. Therefore, the validity of the magnitude of the contribution of each factor needs to be verified in the future. Third, our study uses data solely from Gifu, and does not consider results from other prefectures or years. Therefore, consideration of external validity is necessary. Fourth, since external validation using an independent cohort has not been conducted and a dedicated AutoML tool was utilized, additional research using other external tools will be necessary in the future to confirm the robustness and generalizability of AI model. A past study is reported that structured validation and the use of standard evaluation metrics as an example of AI-enabled biomedical systems [47], and we plan to consider these evaluations in the future. Fifth, our study should be considered with caution regarding the setting the appropriate threshold is important, not just sensitivity and specificity, as the proportion of newly diagnosed dementia development (6%) is small relative to our participants. Given the low event rate and the observed performance characteristics, the model should not be interpreted as a diagnostic or screening tool. Rather, it is more appropriately positioned as a risk stratification or risk prioritization tool to inform downstream attention or triage. Finally, in our study, presence or absence of support/care-need certification was identified as one factor contributing to predicting dementia development, but support/care-need certification may reflect early cognitive/functional decline not yet diagnosed as dementia. On the other hand, a major strength of the present study is the sample size of over 7300 Japanese older adults aged ≥ 75 years. This sample size is sufficient to demonstrate the creation of an AI model for predicting future dementia development and to evaluate its accuracy, and may also help in creating an accurate AI model for predicting dementia development by inferring associated factors.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study indicated that our AI model created using a combination of NDB and dental checkup data modestly improved accuracy of dementia development prediction compared with models trained on NDB data alone. Several dental-related variables were identified as important predictors statistically associated with future dementia development in our AI model, suggesting that obtaining dental information through medical–dental collaboration may be useful for creating AI models for the prediction of disease development. These findings support the potential role of integrating routinely collected medical and dental data into AI-based risk stratification tools for older adults. However, further refinement, external validation, and causal investigations are needed before their clinical implementation. In addition, the operating thresholds reported in this study were derived to illustrate model behavior at a specific operating point and were not prespecified decision rules. Future studies should evaluate prespecified thresholds and assess calibration and precision–recall characteristics in independent external cohorts.

Author Contributions

Methodology, K.I., T.A. and T.T.; validation, K.I. and T.T.; formal analysis, K.I., T.A. and T.T.; investigation, T.A., T.Y., Y.S., K.T., I.S., S.N. and Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.I.; writing—review and editing, K.I.; supervision, T.T.; project administration, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Asahi University (No. 33006; approved 29 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

As the data from the NDB and dental checkup were anonymous, informed consent was not considered necessary.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This study was self-funded by the authors and their institution. The authors are grateful to the Gifu National Health Insurance Federation and the Wide-Area Federation of Medical Care for Late-Stage Older People for providing us with the data. The authors are also grateful to Sony Network Communications for providing advice about the AI model.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| NDB | National Health Insurance Database |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| MCC | Matthews correlation coefficient |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| CIs | Confidence intervals |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

References

- Krinsky-McHale, J.S.; Silverman, W. Dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults with intellectual disability: Issues of diagnosis. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2013, 18, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, C.R.; Weintraub, S.; Sabbagh, M.; Karlawish, J.; Adler, H.C.; Dilworth-Anderson, P.; Frank, L.; Hummel, H.C.; Taylor, A. A New Framework for Dementia Nomenclature. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quail, Z.; Carter, M.M.; Wei, A.; Li, X. Management of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease using a non-pharmacological intervention program: A case report. Medicine 2020, 99, e20128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Patient Survey in 2020. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/kanja/20/index.html (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Devadhasan, P.J.; Kim, S.; An, J. Fish-on-a-chip: A sensitive detection microfluidic system for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisher, A.; Salardini, A. A comprehensive update on treatment of dementia. Semin. Neurol. 2019, 39, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsala, A.; Tsalikidis, C.; Pitiakoudis, M.; Simopoulos, C.; Tsaroucha, K.A. Artificial Intelligence in Colorectal Cancer Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 8, 1581–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.; Shan, H.; Dahoun, T.; Vogel, H.; Yuan, S. Advancing Drug Discovery via Artificial Intelligence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, U.; Baker, S.; Korhonen, A. A systematic literature review of automatic Alzheimer’s disease detection from speech and language. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1784–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Ding, X.; Xu, F.; Ling, Z. Deep learning-based speech analysis for Alzheimer’s disease detection: A literature review. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, M.; Wankhede, N.; Pawar, R.; Ballal, S.; Kumawat, R.; Goswami, M.; Khalid, M.; Taksande, B.; Upaganlawar, A.; Umekar, M.; et al. AI-driven innovations in Alzheimer’s disease: Integrating early diagnosis, personalized treatment, and prognostic modelling. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Hoshide, S.; Kario, K. Hypertension and dementia. Am. J. Hypertens. 2010, 23, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed Husain, K.; Sarhan, F.S.; AlKhalifa, H.; Buhasan, A.; Moin, A.; Butler, E.A. Dementia in Diabetes: The Role of Hypoglycemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, D.; Li, C.; Xie, W.; Zheng, F. Association between Age at Diagnosis of Hyperlipidemia and Subsequent Risk of Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Zou, K.; Shibuya, Y.; Michikawa, M. Oral dysfunctions and cognitive impairment/dementia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureda, A.; Daglia, M.; Castilla, A.S.; Sanadgol, N.; Nabavi, F.S.; Khan, H.; Belwal, T.; Jeandet, P.; Marchese, A.; Pistollato, F.; et al. Oral microbiota and Alzeimer’s disease: Do all roads lead to rome? Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, S.; Stephen, R.; Mäntylä, P.; Suominen, L.A.; Solomon, A. Periodontal health, cognitive decline, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 2695–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuki, M.; Kakizawa, Y.; Nishikawa, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Uchiyama, T. Postsurgical functional outcome prediction model using deep learning framework (Prediction One, Sony Network Communications Inc.) for hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2021, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuki, M.; Kakizawa, Y.; Nishikawa, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Uchiyama, T. Easily created prediction model using deep learning software (Prediction One, Sony Network Communications Inc.) for subarachnoid hemorrhage outcomes from small dataset at admission. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2020, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, O.; Narita, N.; Katsuki, M.; Ishida, N.; Cai, S.; Otomo, H.; Yokota, K. Prediction Model of Deep Learning for Ambulance Transports in Kesennuma City by Meteorological Data. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2021, 13, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, K.; Azuma, T.; Yonenaga, T.; Nomura, T.; Sugiura, I.; Inagawa, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nakashima, S.; Abe, Y.; Tomofuji, T. Relationship between Oral Function and Support/Care-Need Certification in Japanese Older People Aged ≥75 Years: A Three-Year Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, K.; Azuma, T.; Yonenaga, T.; Sasai, Y.; Komatsu, Y.; Tabata, K.; Nomura, T.; Sugiura, I.; Inagawa, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; et al. Predictive Factors Associated with Future Decline in Swallowing Function among Japanese Older People Aged ≥ 75 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Nishida, T.; Sakakibara, H. Factors associated with low albumin in community-dwelling older adults aged 75 years and above. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, S.; Ishii, S.; Hamasaki, T.; Okimoto, N. Incidence of fractures among patients receiving medications for type 2 diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and glucocorticoid users according to the National Claims Database in Japan. Arch. Osteoporos. 2021, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, K.; Azuma, T.; Yonenaga, T.; Ekuni, D.; Watanabe, K.; Obora, A.; Deguchi, F.; Kojima, T.; Morita, M.; Tomofuji, T. Association between Self-Reported Chewing Status and Glycemic Control in Japanese Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Imawatari, R.; Kawahara, C.; Inazu, T.; Suzuki, G. Incidence of type 2 diabetes in pre-diabetic Japanese individuals categorized by HbA1c levels: A historical cohort study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, Q.; Shereen, A.; Estabraq, M.; Jood, S.; Abdelfattah, A.T.; Adil, A. Electronic cigarette among health science students in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2019, 14, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, S.; Kai, Y.; Yamaguchi, D.; Tsuji, T.; Watanabe, R.; Kondo, K. Correlates of walking time by exercise stage of change in older adults in Japan: The 2019 JAGES cross-sectional study. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2022, 69, 861–873. [Google Scholar]

- Satake, S. Basic Checklist and Frailty. GGI 2018, 55, 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, F.; Philip, R.; Helen, W.; Janet, C.; Dwayne, B.; Paul, B. Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 14, 10. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys Basic Methods, 5th ed.; World Health Organization Publishers: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Satake, A.; Kobayashi, W.; Tamura, Y.; Oyama, T.; Fukuta, H.; Inui, A.; Sawada, K.; Ihara, K.; Noguchi, T.; Murashita, K.; et al. Effects of oral environment on frailty: Particular relevance of tongue pressure. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 12, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, F.; Mizukami, M.; Ayano, R.; Mukai, Y. Analysis of feeding function and jaw stability in bedridden elderly. Dysphagia 2002, 17, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.; Kantawalla, F.R.; Dickie, S.; Suarez-Durall, P.; Enciso, R.; Mulligan, R. Association of Oral Health and Mini Nutritional Assessment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review with Meta-analyses. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2022, 66, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Eida, S.; Katayama, I.; Takagi, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Sumi, M.; Ariji, Y. A radiomics model combining machine learning and neural networks for high-accuracy prediction of cervical lymph node metastasis on ultrasound of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2025, 139, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, D.; Aoki, K.; Shojima, C.; Takayama, D.; Taniguchi, M.; Yoshitake, R.; Shinkai, Y.; Kurawaki, S.; Miyazaki, M.; Nakamura, S.; et al. Post-dialysis blood urea nitrogen value prediction using machine learning. RRT 2023, 56, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SONY, Prediction One®. To improve Prediction Accuracy Level. Available online: https://predictionone.sony.biz/cloud_manual/tips/result/improve_model/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Gale, A.S.; Acar, D.; Daffner, R.K. Dementia. Am. J. Med. 2018, 131, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Huang, C.; Tsai, C.; Chou, P.; Lin, C.; Chang, C. Alcohol-Related Dementia: A Systemic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Psychosomatics 2017, 58, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraets, F.A.; Leist, K.A. Sex/gender and socioeconomic differences in modifiable risk factors for dementia. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SONY, Prediction One®. Prediction Accuracy Level. Available online: https://predictionone.sony.biz/cloud_manual/terminology/model_level/#: (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Zou, M.; Yu, H.; Zhou, R.; Lu, Y.; Underwood, R.; Tseng, T.; Luo, S. Association between dental floss use, dental visits, and a five-year Alzheimer’s disease risk prediction score among United States adults aged 65 years and older. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 108, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sura, L.; Madhavan, A.; Carnaby, G.; Crary, A.M. Dysphagia in the elderly: Management and nutritional considerations. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Marin, M.S.; Mansur, L.L.; Oliveira, F.F.; Marin, F.L.; Wajman, R.J.; Bahia, S.V.; Ferreira-Bertolucci, H.P. Swallowing in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2021, 79, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Survey on Prevalence of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment and Future Projections. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001279920.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Cabinet Office. Annual Report on the Ageing Society in 2024. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2024/zenbun/pdf/1s2s_02.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Pratticò, D.; Carlo, D.; Silipo, G.; Laganà, F. Hybrid FEM-AI approach for thermographic monitoring of biomedical electronic devices. Computers 2025, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.