Abstract

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological condition characterized by endometrium-like tissue outside the uterus. In clinical practice, diagnosis and anatomical mapping rely heavily on imaging, yet performance remains operator- and modality-dependent. Artificial intelligence (AI) has been increasingly applied to endometriosis imaging. We conducted a PRISMA-ScR-guided scoping review of primary machine learning and deep learning studies using endometriosis-related imaging. Five databases (MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar) were searched from 2015 to 2025. Of 413 records, 32 studies met inclusion and most were single-center, retrospective investigations in reproductive-age cohorts. Ultrasound predominated (50%), followed by laparoscopic imaging (25%) and MRI (22%); ovarian endometrioma and deep infiltrating endometriosis were the most commonly modeled phenotypes. Classification was the dominant AI task (78%), typically using convolutional neural networks (often ResNet-based), whereas segmentation (31%) and object detection (3%) were less explored. Nearly all studies relied on internal validation (97%), most frequently simple hold-out splits with heterogeneous, accuracy-focused performance reporting. The minimal AI-method quality appraisal identified frequent methodological gaps across key domains, including limited reporting of patient-level separation, leakage safeguards, calibration, and data and code availability. Overall, AI-enabled endometriosis imaging is rapidly evolving but remains early-stage; multi-center and prospective validation, standardized reporting, and clinically actionable detection–segmentation pipelines are needed before routine clinical integration.

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory gynecological disease characterized by endometrium-like tissue located outside the uterus, most commonly on pelvic peritoneum, ovaries, and rectovaginal septum [1]. It affects an estimated 10% of women during their reproductive years, and approximately 190 million females worldwide [1,2,3]. Beyond debilitating dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis is associated with subfertility, gastrointestinal and urinary symptoms, reduced quality of life, and substantial economic and societal cost [4,5,6].

Despite its burden, endometriosis remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Symptoms are heterogeneous and overlap with other gynecologic, urologic, and gastrointestinal conditions [4,6]. Historically, laparoscopic visualization with histopathological confirmation has been considered the diagnostic gold standard, limiting diagnosis to those who undergo surgery [7]. Multiple contemporary studies report average diagnostic delays of 4–11 years from symptom onset, a figure that has changed little over decades and which is longer in adolescents and marginalized populations [8,9].

Imaging plays a central role in addressing these diagnostic challenges [10]. Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the recommended first-line modality for suspected pelvic and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE), enabling real-time assessment of endometriomas, rectosigmoid lesions, and pouch of Douglas obliteration [11]. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a complementary second-line tool for mapping deep disease, assessing extra-pelvic sites, and supporting preoperative planning [12]. Laparoscopic and hysteroscopic imaging provide intraoperative guidance and histopathology confirms diagnosis. However, performance remains highly operator- and center-dependent, superficial and atypical lesions may be missed, acquisition and reporting lack standardization, and access to expert readers is uneven, leading to variable diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning [10,13].

Artificial intelligence (AI), encompassing machine learning and deep learning, has emerged as a promising approach to augment endometriosis imaging. AI-enabled computer vision models can learn complex spatial and textural patterns from ultrasound, MRI, and endoscopic images, supporting automated detection, segmentation, and phenotyping of endometriotic lesions [14,15]. Convolutional neural networks and transformer-based architectures have achieved high performance in analogous tasks across radiology and surgical video analysis, and early studies in endometriosis suggest potential for improved lesion detection, standardized disease mapping and intraoperative guidance [16,17]. In principle, such systems could reduce operator dependence, extend expert-level interpretation to low-resource settings, and ultimately shorten the time to accurate diagnosis.

Several reviews have explored the evolving AI literature in endometriosis. These studies have summarized AI applications across heterogeneous data sources, including electronic health records, questionnaires, omics, and imaging, to support early diagnosis, risk prediction, and management [14,15,16,17,18]. A recent narrative review specifically highlighted emerging AI applications in endometriosis imaging, focusing on selected ultrasound and MRI studies and conceptual opportunities for computer vision [16]. Other work has examined AI for minimally invasive surgery or digital health tools more broadly, with imaging discussed only as one component of a wider ecosystem [15,18]. However, to date there has been no systematic, PRISMA-aligned scoping review dedicated to clinical applications of AI in endometriosis imaging that comprehensively maps imaging modalities, clinical indications, endometriosis phenotypes, AI tasks, model architectures, and evaluation strategies.

The objective of this scoping review is therefore to map the current landscape of AI-enabled endometriosis imaging. Specifically, we aim to (1) explore the clinical contexts and endometriosis phenotypes targeted by AI models across different imaging modalities; (2) characterize imaging datasets, labeling references, and multimodal inputs used along with imaging for model development and validation; (3) summarize the AI tasks, architectures, and evaluation strategies; and (4) identify methodological gaps, translational barriers, and priority directions for future research. By consolidating this evidence, we seek to inform clinicians, researchers, and technology developers about the readiness of AI for real-world deployment in endometriosis imaging and highlight opportunities to design clinically meaningful and generalizable AI tools.

2. Methods

We conducted this scoping review in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidance [19].

2.1. Study Eligibility Criteria

We applied prespecified eligibility criteria using the Population–Concept–Context (PCC) framework to determine study inclusion.

Inclusion Criteria:

- Population/Problem: Human studies involving individuals with suspected or confirmed endometriosis; adolescents through peri/post-menopausal populations were eligible.

- Concept (AI and Imaging): Application of artificial intelligence to imaging data, including radiology (e.g., ultrasound, MRI, and CT where applicable) and endoscopic/intraoperative video (laparoscopy and hysteroscopy). Eligible AI methods included classical machine learning on image-derived features, deep learning architectures (e.g., CNNs and vision transformers), models for classification, detection, or segmentation, as well as foundation and multimodal models. We operationally defined “AI” as data-driven learning algorithms (supervised or unsupervised) applied to raw images/video or quantitative image-derived features (e.g., radiomics/texture features combined with classical ML classifiers/regressors). Studies limited to conventional descriptive/inferential statistics or rule-based image processing without model training were considered non-AI and excluded.

- Context: Any healthcare or research setting (diagnostic imaging, preoperative planning, and intraoperative guidance/video analysis).

- Study Types, Language, and Dates: Empirical primary studies (retrospective/prospective; observational/interventional; method/benchmark papers), conference proceedings, and theses/dissertations that clearly describe methods and results; English language; published between 2015 and 2025.

Exclusion Criteria:

- Population/Problem: Non-human/animal studies; adenomyosis-only studies unless endometriosis is jointly analyzed with separable results.

- Concept (AI and Imaging): Studies without imaging data (e.g., EHR/NLP/wearables/apps-only) or without imaging-derived features (e.g., prediction models using only clinical/demographic variables), or those using conventional statistics or rule-based image processing without ML/computer vision.

- Publication Types: Commentaries, editorials, and patents.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We searched five databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar. Full database-specific search strings, filters, and yields are provided in Table 1 to enable reproducibility. Overall, the database queries combined three concepts: Endometriosis AND Imaging modality AND AI.

Table 1.

Search strategies.

- Endometriosis terms: endometriosis, endometriotic, deep infiltrating endometriosis, deep endometriosis, DIE, ovarian endometrioma, superficial peritoneal endometriosis, pelvic endometriosis, rectovaginal endometriosis, rectosigmoid endometriosis.

- Imaging terms: ultrasound, sonography, MRI (e.g., T2-weighted, diffusion), laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, endoscopic/surgical video.

- AI/Computer Vision terms: artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, convolutional neural network, transformer, U-Net, computer vision, segmentation, detection, classification, foundation model.

The search window was limited to the period from 1 January 2015 to 4 November 2025. The initial search was conducted on 5 October 2025, and an auto-alert was configured to capture new records for four weeks thereafter. Across databases, we applied English language limits and a 2015–2025 publication window (and human-only limits where supported). All retrieved records were exported to EndNote for deduplication prior to screening. No backward or forward citation chasing was performed.

2.3. Study Selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text assessment against the prespecified criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion; a third reviewer adjudicated when needed. Inter-rater agreement was quantified using Cohen’s kappa (κ) for both screening stages: title/abstract screening (κ = 0.80) and full-text screening (κ = 0.85).

2.4. Data Extraction

Two reviewers dual-charted 10% of studies for calibration; the remaining records were single-extracted with second-reviewer verification, with dual extraction performed when warranted. Data extraction form is provided in Supplementary Material S1.

2.5. Data Synthesis

We synthesized the extracted data narratively, presenting findings through text, tables, and figures. Synthesis was organized across four domains:

(1) Study metadata, design, and population (author, year, publication type, country, research design, number of sites, sample size, and age group).

(2) Endometriosis phenotype and clinical context. (Phenotypes studied; clinical application categories—diagnosis, lesion/organ detection–segmentation–phenotyping, staging, preoperative planning, screening/triage, intraoperative guidance; outcomes such as presence/absence of endometriosis, differential diagnosis, lesion/organ segmentation, histopathology classification, and symptom/clinical outcomes; and reference standard. For studied outcomes (targets), we applied concise operational definitions to ensure consistent coding across heterogeneous endometriosis AI studies. “Endometriosis presence vs. absence” referred to case-level diagnosis without lesion localization. “Lesion detection/segmentation” referred to image-level lesion identification with spatial output (localization and/or pixel-wise masks.) “Differential diagnosis” referred to distinguishing endometriosis from alternative pelvic/ovarian pathology rather than a generic “no disease” label. “POD obliteration/sliding sign” captured prediction of cul-de-sac obliteration and/or sliding sign status, typically on ultrasound. “Severity/stage/phenotype” referred to grading or subtype/phenotype classification (e.g., stage or DIE/OMA/SPE phenotypes). “Organ/structure segmentation” referred to delineation of relevant anatomy (e.g., uterus/ovaries/bowel) rather than lesions. “Histopathology classification” referred to prediction on microscopy/staining images. “Symptom/clinical outcome prediction” referred to modeling patient-level symptoms or clinical endpoints using imaging with or without additional data. For reference standard, we additionally coded studies as using a hard standard (surgery and/or histopathology confirmation, including surgery+histopathology, histopathology-only, or surgical visual diagnosis) versus a soft standard (expert imaging assessment without surgical/histopathology confirmation).

(3) Imaging data characteristics: data source, number of images, imaging modality, and additional modalities used along with imaging. To clarify model input representation, we categorized “type of imaging features” into four operationally defined groups: (i) Image (still images only), (ii) Video (videos only), (iii) Image + Video (both), and (iv) Tabular imaging features only. “Image” refers to models trained on static images or single frames (e.g., 2D ultrasound snapshots, individual MRI slices, and still laparoscopic frames). “Video” refers to models trained on temporally ordered sequences (e.g., laparoscopic/hysteroscopic videos or ultrasound cine clips) where temporal information was explicitly preserved/used; if a study extracted frames from videos and modeled them as independent still images without temporal modeling, it was coded as “Image.” “Image + Video” refers to studies that used both still images and videos as inputs (either in separate models or within a combined pipeline). “Tabular imaging features only” refers to studies that did not use raw images/videos for model input and instead trained models exclusively on quantitative imaging-derived features (e.g., radiomics/hand-crafted texture, intensity, morphologic, or measurement features) represented in tabular form.

(4) AI model characteristics: AI task; model architectures; outcome type; validation type and technique; performance metrics used; and whether a confusion matrix was provided. To improve reproducibility of task labeling in this heterogeneous AI literature, we applied operational definitions for AI task categories. “Classification” referred to case-level prediction (e.g., endometriosis presence vs. absence or differential diagnosis) without a requirement to localize lesions. “Detection/localization” required an explicit spatial localization output (e.g., bounding box, keypoint, region proposal, or comparable localization map) identifying where a lesion/structure is present. “Segmentation” required pixel-wise (or voxel-wise) delineation of a lesion or organ as a mask. Task categories were not mutually exclusive, and a single study could contribute to more than one category when multiple outputs were modeled.

2.6. Minimal AI Method Quality Appraisal

Because methodological quality and reporting rigor vary substantially in imaging AI studies, we conducted a minimal, non-exclusionary methodological appraisal to contextualize the maturity of the evidence base. This appraisal was used to summarize key quality indicators and identify common gaps; it was not used to exclude studies. For each included study, we extracted and coded (Yes/No/Unclear, as applicable) the following items: (1) split unit reported (patient/exam vs. image/frame/clip); (2) patient-level separation used (all images/videos from a given patient contained within a single split); (3) leakage prevention described (e.g., steps to prevent overlap/near-duplicates/temporal leakage across splits); (4) external validation (evaluation on a separate institution/geography); (5) calibration reported (e.g., calibration plot, Brier score, and calibration intercept/slope); (6) handling of class imbalance (e.g., class weights, oversampling, and thresholding); (7) uncertainty and statistical precision reporting (e.g., confidence/uncertainty estimates and/or confidence intervals for key metrics); (8) data availability; and (9) code availability. Detailed criteria and decision rules for coding each domain are provided in Supplementary Material S2. The resulting appraisal was used to support evidence-based discussion of methodological gaps and translational readiness.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

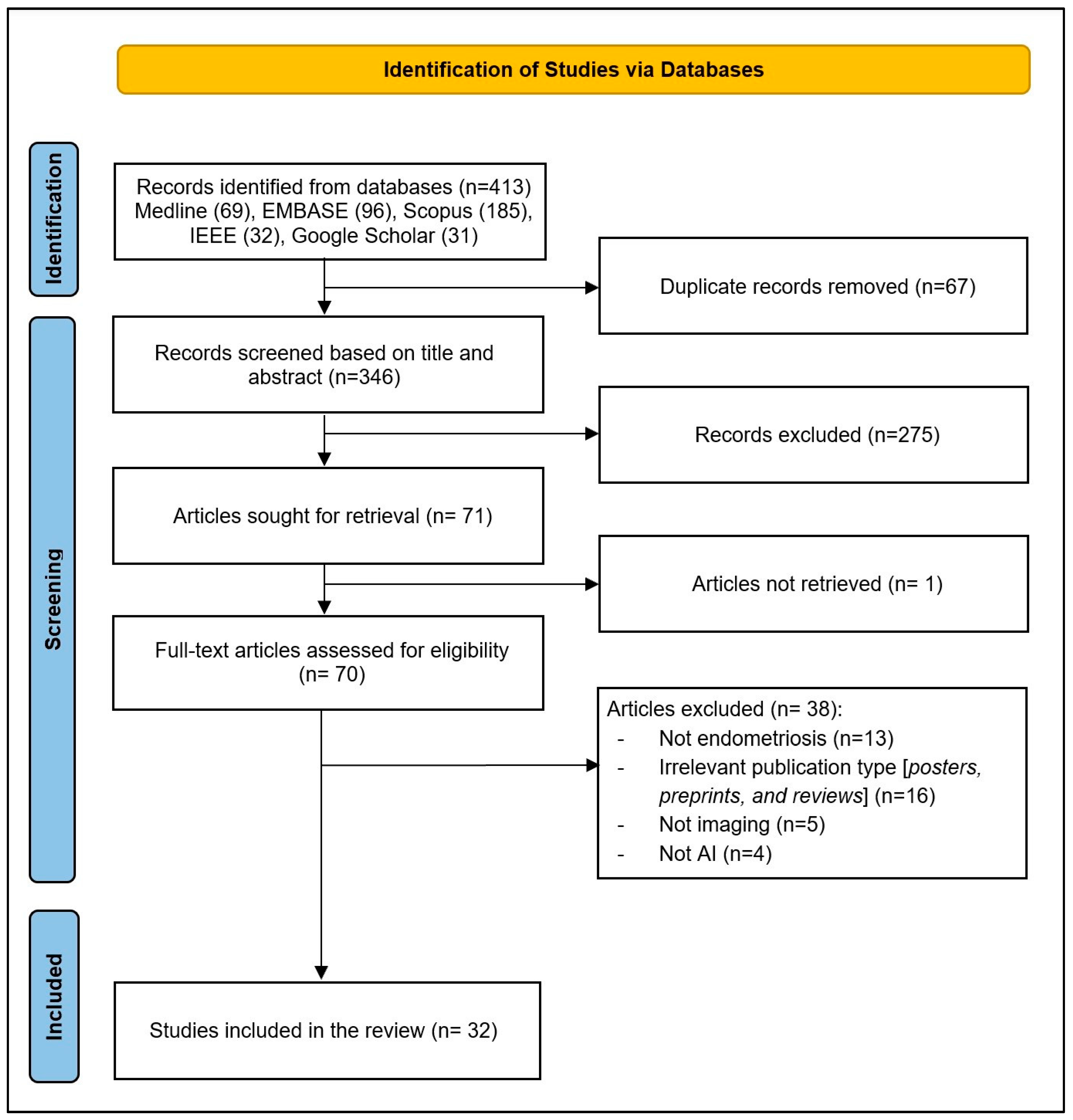

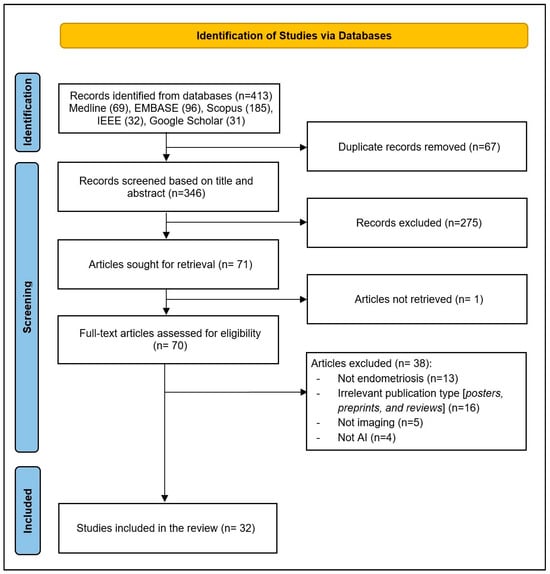

As illustrated in Figure 1, a total of 413 records were identified through database searches. After removing 67 duplicates, 346 records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 275 records were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The full texts of 71 articles were sought for retrieval; 1 article could not be retrieved. In total, 70 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 38 were excluded for the following reasons: not endometriosis (n = 13), irrelevant publication type (posters, preprints, and reviews; n = 13), not imaging (n = 5), and not AI (n = 4). Finally, 32 studies were included in the final review [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Most included studies are recent, with the bulk published in 2023–2025. Notably, although the search window spanned 2015–2025, no eligible studies were published before 2018. Most studies were journal articles (27; 84%), with conference proceedings accounting for 5 (16%). Studies originated from 15 countries, led by China (8; 24%), Australia (4; 12%), and the United States (3; 9%). Methodologically, study designs were predominantly retrospective (28/32; 88%), with only four prospective investigations. Most studies were single-site (25/32; 78%), and four were multi-site. Among studies reporting a sample size (n = 25), the mean cohort size was 416.4 (SD 864.8) females, spanning a range of 26–4448 participants. With respect to population, most studies targeted reproductive-age cohorts (26/32; 81%), and one study included peri/post-menopausal participants (Table 2). Detailed per-study characteristics are available in Supplementary Material S3.

Table 2.

Study metadata, design, and population characteristics.

3.3. Endometriosis Phenotyping, and Clinical Applications

Phenotypically, ovarian endometrioma was most frequently studied (14/32; 44%), followed by deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) (11/32; 34%); superficial peritoneal disease appeared rarely (2/32; 6%). Notably, phenotype/location was not specified in one-third of studies (10/32; 31%), highlighting variability in phenotypic reporting.

Regarding outcomes, the leading target was endometriosis presence vs. absence (9/32; 28%), followed by lesion segmentation/detection (8/32; 25%) and differential diagnosis vs. other pelvic/ovarian pathology (5/32; 15%). Fewer studies addressed POD obliteration/sliding sign, disease severity/staging, and organ/structure segmentation.

In terms of clinical applications, most models targeted diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis and related adnexal pathology (25/32; 78%). Smaller subsets focused on lesion/organ segmentation and phenotyping (10/32; 31%), and preoperative surgical planning/risk stratification (5/32; 16%).

For labeling, the predominant reference standard was expert imaging assessment (18/32; 56%), with fewer studies using histopathology only (5/32; 16%) or the surgical–histopathology gold standard (4/32; 13%). A minority relied on surgical visual diagnosis (2/32; 6%) or clinical records/biomarkers (2/32; 6%). When stratified, 11/32 studies (34%) used a hard reference standard (surgery and/or histopathology confirmation), whereas 18/32 (56%) relied on a soft imaging-only expert assessment; the remaining 3/32 (9%) used clinical records/biomarkers or did not report the label source. Overall disease representation and clinical applications are summarized in Table 3. Detailed per-study phenotyping and clinical applications are available in Supplementary Material S4.

Table 3.

Endometriosis phenotyping and clinical applications.

3.4. Imaging Data Characteristics

As shown in Table 4, ultrasound was the predominant imaging modality (16/32; 50%), reflecting its central role in contemporary endometriosis assessment. Laparoscopic imaging was the second most common modality (8/32; 25%), followed by MRI (7/32; 22%), demonstrating that AI research in endometriosis imaging remains heavily anchored in sonographic and surgical video data.

Table 4.

Imaging data characteristics.

Most studies used still images as the primary input (24/32; 75%), while fewer used video-only datasets (3/32; 9%) or combined image–video inputs (1/32; 3%). A small subset relied solely on tabular imaging-derived features (4/32; 13%), typically extracted from ultrasound or MRI examinations. Regarding multimodal integration, three-quarters of studies used imaging alone without additional data (24/32; 75%). The remaining studies incorporated clinical variables (6/32; 19%), laboratory data (3/32; 9%), or demographics (3/32; 9%), indicating early but growing interest in multimodal AI pipelines.

Most datasets were private and institution-specific (24/32; 75%), with public datasets used in roughly one-quarter of studies (8/32; 25%). Among publicly available resources, GLENDA/GLENDA-VIS were most frequently used (6/32; 19%), followed by ENID/ENIDDS (3/32; 6%). Across studies that reported dataset size (28/32; 88%), imaging volumes varied widely, with a mean of 5071 examinations/images/videos/clips/slices (SD 9625.5), underscoring substantial heterogeneity in dataset scale. Detailed per-study imaging data characteristics are available in Supplementary Material S5.

3.5. AI Model Characteristics

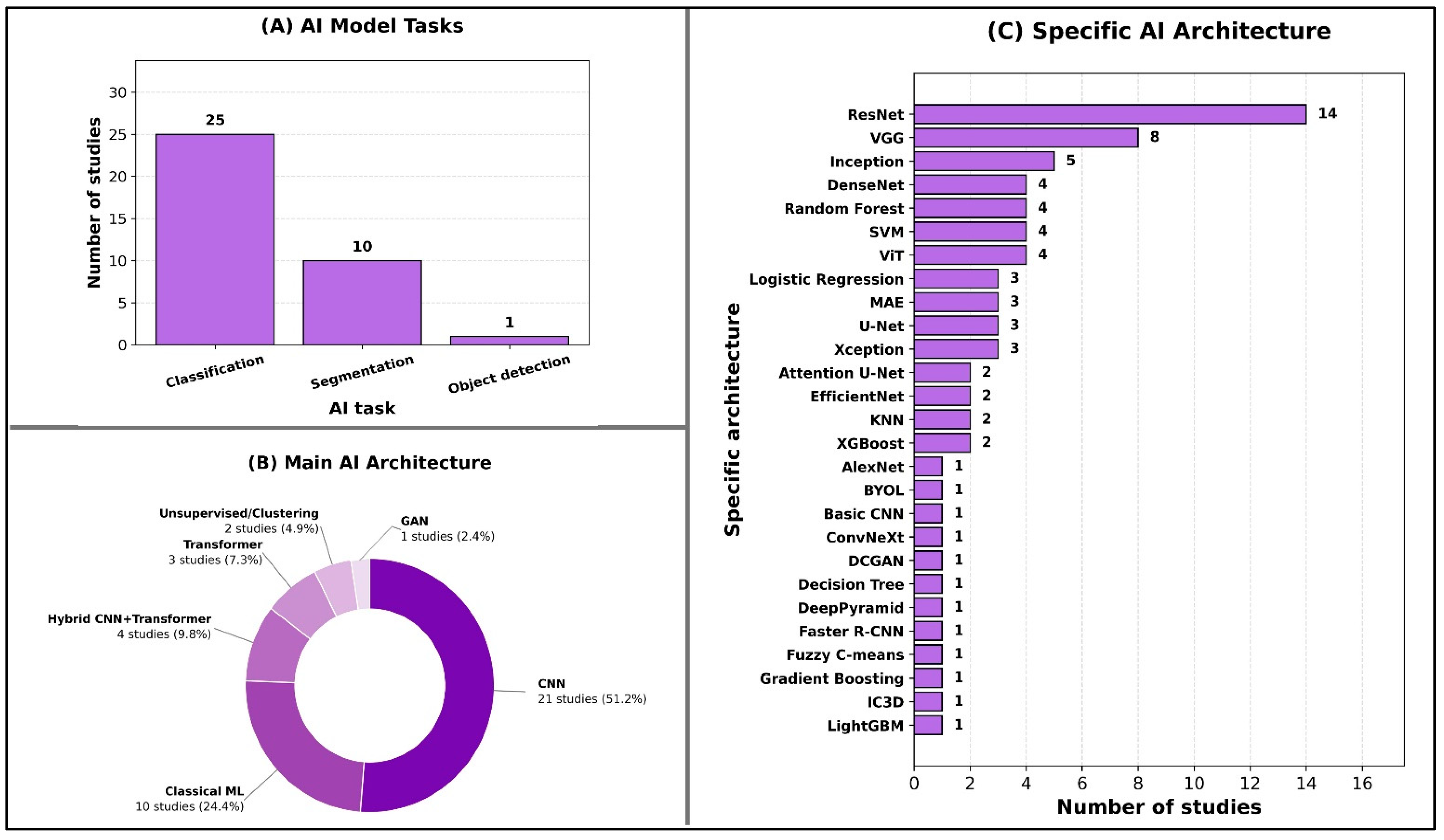

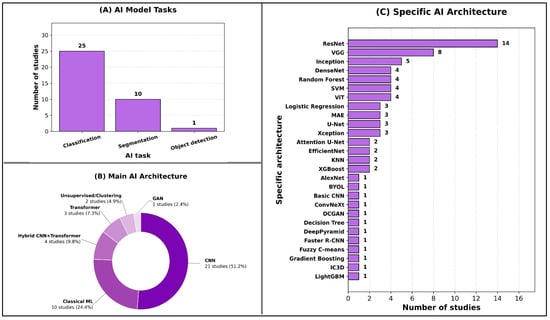

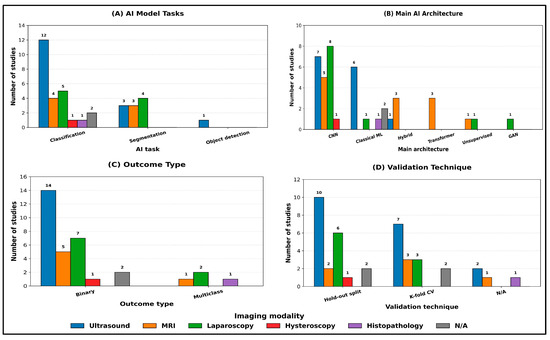

The predominant AI task was classification, reported in 25 out of 32 studies (78%), reflecting the field’s current emphasis on diagnostic discrimination. Here, “classification” denotes case-level diagnostic prediction (e.g., presence vs. absence or differential diagnosis) without requiring lesion localization, whereas “object detection” denotes lesion/structure localization (e.g., bounding boxes/region proposals) and “segmentation” denotes pixel-wise lesion/organ delineation. Segmentation tasks were the next most frequent (10/32; 31%), largely focused on lesion or organ delineation, while object detection was explored in only one study (3%), underscoring early adoption of detection-specific pipelines in this domain (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Overview of AI model tasks and architectures.

In terms of main AI architectures, most studies employed convolutional neural networks (CNNs) (21/32; 66%), with fewer using classical machine learning methods (10/32; 31%) or hybrid CNN–transformer architectures (4/32; 13%). Transformer-only models appeared in three studies (9%), and unsupervised or clustering approaches in two studies (6%), indicating selective but emerging interest in alternative deep learning paradigms. Only one study (3%) used a generative adversarial network (GAN) (Figure 2B).

At the specific architecture level, ResNet dominated (14/32; 44%), followed by VGG (8/32; 25%) and Inception variants (5/32; 16%). Several classical algorithms—such as Random Forest, SVM, and Logistic Regression—were each used in multiple studies, while a broad range of other architectures appeared less frequently, demonstrating methodological heterogeneity across the field (Figure 2C).

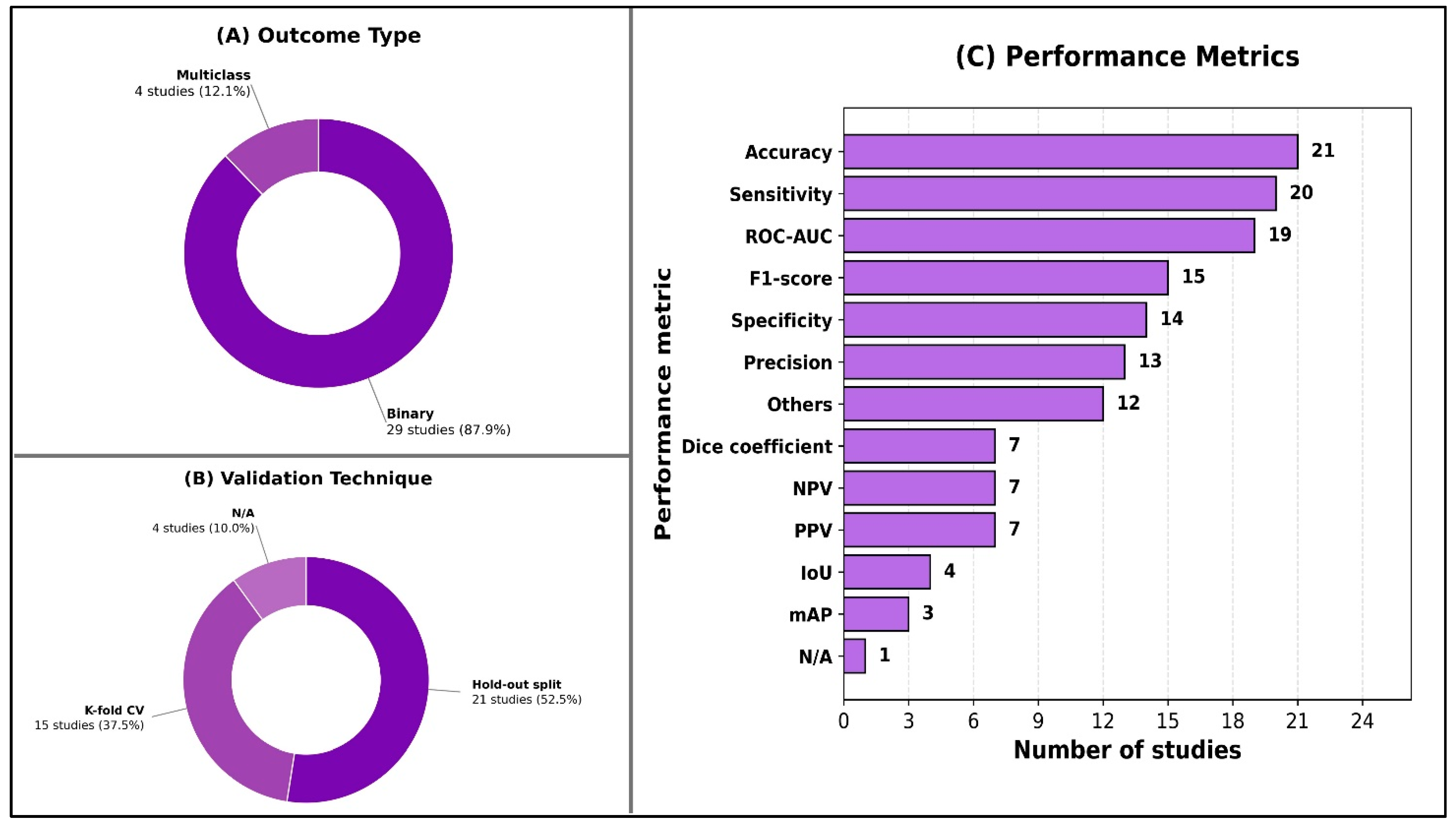

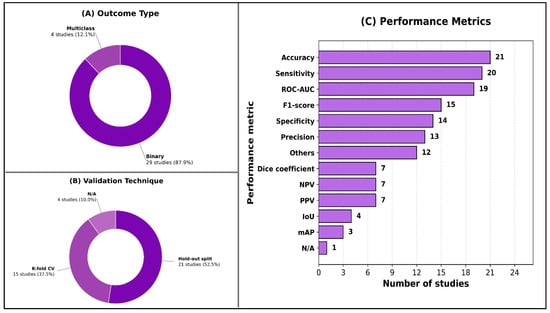

As shown in Figure 3, nearly all studies framed their prediction problems as binary classification (29/32; 91%), with multiclass outputs examined in only four studies (13%). Internal validation predominated across included studies (31/32; 97%); only one study performed external validation. Most studies used a hold-out split (21/32; 66%), and many incorporated k-fold cross-validation (15/32; 47%). Performance reporting varied, but accuracy was the most commonly reported metric (21/32; 66%), followed by sensitivity/recall (20/32; 63%) and ROC-AUC (19/32; 59%). F1-score appeared in nearly half of studies (15/32; 47%), while segmentation-focused metrics such as the Dice coefficient (7/32; 22%) and IoU (4/32; 13%) were less frequent. Detailed per-study AI model characteristics are available in Supplementary Material S6.

Figure 3.

Overview of model evaluation characteristics.

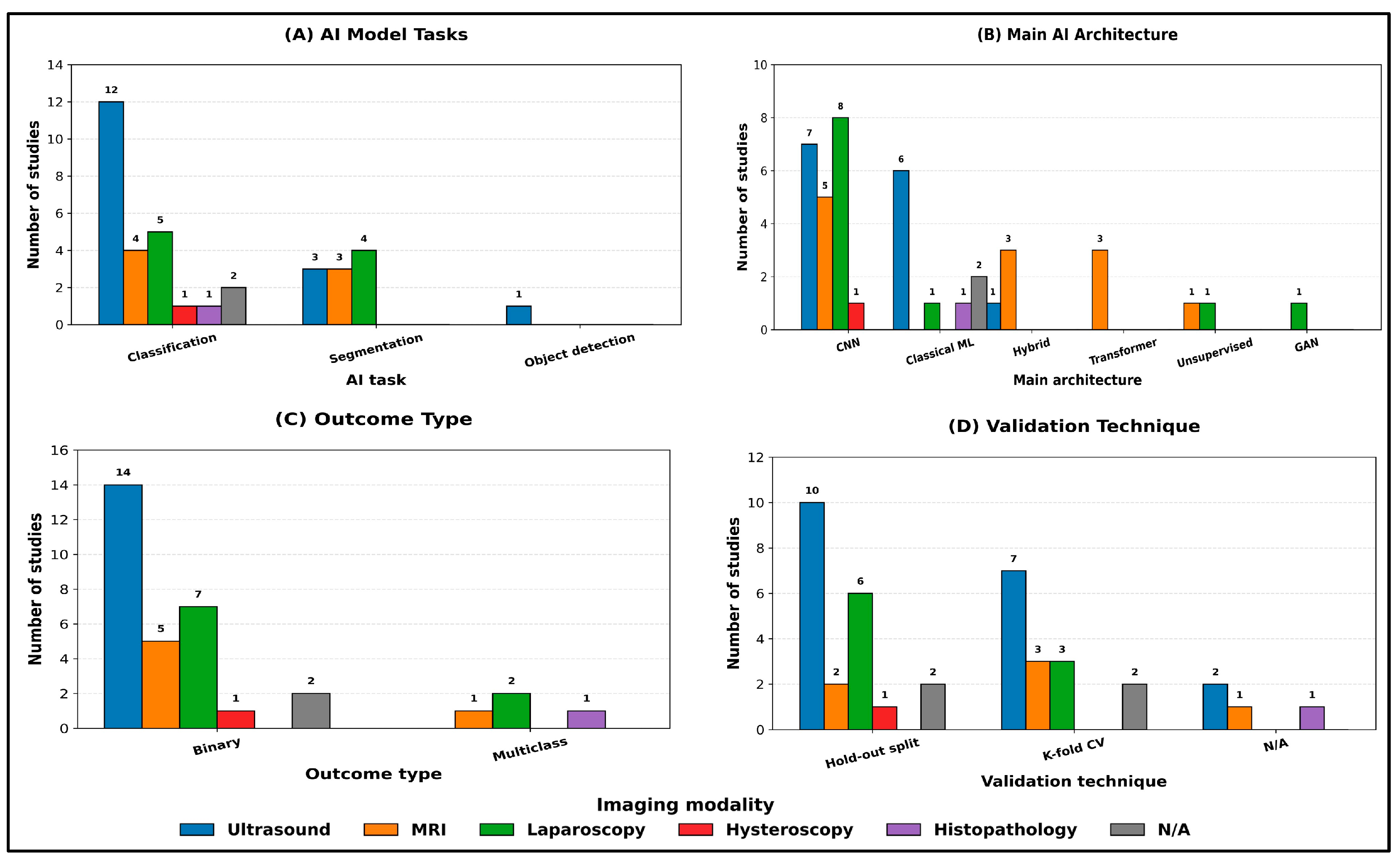

When the same analysis was stratified by imaging modality (Figure 4A–D), classification remained the dominant task across all modalities. Ultrasound studies (n = 14) were primarily classification-focused (12/14; 86%), with fewer segmentation tasks (3/14; 21%), and they were the only modality to include object detection (1/14; 7%) (Figure 4A). MRI studies (n = 6) showed a more balanced distribution between classification (4/6; 67%) and segmentation (3/6; 50%), while laparoscopy studies (n = 8) similarly included both classification (5/8; 63%) and segmentation (4/8; 50%), reflecting the parallel use of discriminative and delineation-oriented pipelines in these modalities (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Main AI model characteristics stratified by imaging modality. Counts are reported as the number of studies per category within each modality. Where a study reported multiple categories within a given field, it was counted once in each applicable category.

Across modalities, CNN-based approaches remained predominant, but the architecture mix varied substantially (Figure 4B). Laparoscopy relied exclusively on CNNs (8/8; 100%) and was the only modality incorporating GANs (1/8; 13%), whereas MRI demonstrated the greatest uptake of transformer components, including transformer-only models (3/6; 50%) and hybrid CNN–transformer architectures (3/6; 50%). In contrast, classical machine learning methods were more frequently observed in ultrasound (6/14; 43%) and in studies with non-specified modalities (2/2; 100%), with limited adoption in laparoscopy (1/8; 13%) and exclusive use in histopathology (1/1; 100%). Unsupervised/clustering approaches were uncommon and appeared only in MRI (1/6; 17%) and laparoscopy (1/8; 13%) (Figure 4B).

Outcome formulation was predominantly binary within each imaging modality (ultrasound: 14/14; 100%; MRI: 5/6; 83%; laparoscopy: 7/8; 88%), while multiclass outcomes were comparatively rare and confined to laparoscopy (2/8; 25%), MRI (1/6; 17%), and histopathology (1/1; 100%) (Figure 4C). Validation remained predominantly internal across modalities, with hold-out split used most commonly in ultrasound (10/14; 71%) and laparoscopy (6/8; 75%), while k-fold cross-validation was frequently used in ultrasound (7/14; 50%) and MRI (3/6; 50%) (Figure 4D). Studies reporting no explicit validation strategy (N/A) were infrequent and observed mainly in ultrasound (2/14; 14%), MRI (1/6; 17%), and histopathology (1/1; 100%) (Figure 4D).

3.6. Reported Model Performance (Descriptive Summary)

Given the heterogeneity in imaging modalities, classification tasks, reference standards, and validation designs, we summarize reported model performance descriptively within the scope of this scoping review (as ranges of commonly reported metrics) rather than pooling estimates.

Across the included studies, reported performance was highly task- and evaluation-dependent. For diagnostic/differential classification, AUROC values commonly clustered around ~0.80–0.99, with examples ranging from ~0.65 (an MRI 3D ViT baseline [50]) up to 0.986–0.987 (CNN/radiomics/nomogram models [35]), and several studies reporting ~0.90 (e.g., DenseNet test sets, TVUS models, and multimodal/cross-validated settings). Accuracy in classification likewise ranged broadly from ~0.72 to 0.99, with multiple studies reporting ~0.88 to 0.97 on test/hold-out sets; however, specificity and PPV/NPV showed substantial tradeoffs when reported (e.g., one XGBoost model with high sensitivity (~0.96) but very low specificity (~0.11) [41]; threshold-dependent shifts where specificity ranged from ~0.65 to 0.90 with corresponding PPV/NPV changes). For segmentation, reported overlap metrics varied widely: Dice ranged from ~0.29 (ovary segmentation [34]) to ~0.82–0.96 (e.g., Dice value of 0.818 in a DenseNet121–U-Net ensemble [39]; Dice value of 0.957 in a U-Net variant [27]), with several lesion-focused results in the ~0.65–0.93 range (e.g., TransUNet Dice improving from 0.516 to 0.654 [24], and IoU/Dice up to 54.04%/67.63% on ENID [25]). For detection/instance segmentation, performance was typically reported using mAP, with representative values around mAP@0.50 ≈ 0.64 (and mAP@[0.50:0.95] ≈ 0.32) in lesion/implant settings, while one YOLOv8 study showed mAP50 ≈ 0.978 [45].

3.7. Minimal AI Method Quality Appraisal Results

Most studies reported a train/validation/test partitioning scheme and/or cross-validation, with the split unit explicitly stated in 23/32 studies (72%). However, only 12/32 studies (38%) explicitly confirmed patient-level separation (i.e., grouping all samples from the same patient within a single split), while this was unclear in over half of studies (53%). Explicit descriptions of leakage safeguards (e.g., duplicate/near-duplicate removal, temporal separation, or explicit statements of avoiding overlap across splits) were uncommon (6/32; 19%) and were not discussed in most studies (72%).

External validation was rare: only 1/32 studies (3%) evaluated performance on an external cohort, whereas the remaining 31/32 studies (97%) relied on internal validation only. Calibration reporting was similarly limited, reported in 2/32 studies (6%) and absent/unclear in the remainder. Class imbalance handling was explicitly described in 5/32 studies (16%) and was typically not reported (81%). Reporting of uncertainty or statistical precision (e.g., confidence intervals and variability across folds) was more frequent but still inconsistent, present in 14/32 studies (44%). Data availability statements were present in 13/32 studies (41%), while code availability was reported in only 4/32 (12%), indicating limited transparency and reproducibility reporting overall. These aggregate findings are based on the per-study appraisal presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Minimal AI method quality appraisal items (coded as Yes/No/Unclear) across included. Key: (1) Split unit reported; (2) Patient-level separation used; (3) Leakage prevention described; (4) External validation; (5) Calibration reported; (6) Class imbalance handling; (7) Uncertainty and/or statistical precision reporting; (8) Data availability; (9) Code availability.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

This review maps a rapidly expanding yet early-phase field of AI-enabled endometriosis imaging. Across 32 primary studies published predominantly within the last three years, the literature is characterized by single-center, retrospective designs and notable geographic clustering in China. To synthesize findings in a clinically meaningful way, we summarize study contributions under two organizing lenses: (A) clinical application along the care pathway and (B) modality-specific development considerations.

4.1.1. Clinical Applications Across the Endometriosis Care Pathway

Diagnosis and triage support: Most studies positioned AI as a diagnostic discriminator, commonly predicting endometriosis presence versus absence [20,23,24,26,41,43,46,47,48]. Within this application, ovarian endometrioma and deep infiltrating endometriosis were the most frequently modeled phenotypes [22,28,29,32,33,34,35,37,38,46], whereas superficial peritoneal disease and extra-pelvic sites were rarely addressed [32,37]. Clinically, case-level diagnostic models may reduce operator dependence and support more consistent triage and referral, particularly when imaging appearances are subtle or heterogeneous and where subspecialty expertise is limited. However, this application is inherently constrained by phenotype coverage: tools optimized for endometrioma or DIE may not generalize to the broader and clinically important spectrum of superficial or extra-pelvic disease, limiting their utility as comprehensive diagnostic aids.

Differential diagnosis and adnexal pathology classification: Several ultrasound-focused studies extended beyond “endo vs. no endo” to address clinically common diagnostic ambiguities, including differentiation of endometrioma from other ovarian/adnexal conditions [28,33,35,38,42]. This line of work is clinically relevant because it targets high-frequency real-world dilemmas (e.g., hemorrhagic cysts, inflammatory pathology, and benign tumors) that directly influence referral, follow-up imaging, and surgical planning. The translational value of these tools depends on whether cohorts reflect real-world prevalence and whether performance is reported in clinically interpretable terms (e.g., threshold-based sensitivity/specificity) rather than accuracy-dominant summaries.

Lesion mapping, detection, and segmentation: Spatial modeling (detection/segmentation) was also a common target [25,29,30,31,32,39,40,45] and is arguably more aligned with actionable care. By producing localization or masks, these approaches shift assessment from “is disease present?” to “where and how extensive,” enabling standardized lesion mapping, quantitative burden estimation, and potentially reducing time and variability associated with manual delineation. This application is especially relevant for preoperative planning and multidisciplinary coordination because it can operationalize site-specific disease extent and organ involvement.

Staging and adhesion assessment: A smaller set of studies addressed staging and related constructs [21,36,49,50], including POD obliteration/sliding sign modeling [21,36,49,50]. These targets are clinically meaningful because they encode severity and adhesions into standardized outputs that can influence counseling, choice of surgical setting, and need for multidisciplinary involvement. Because these endpoints are operator-dependent and dynamic by nature, they also represent a key area where AI could improve consistency—provided that model development and evaluation incorporate realistic dynamic inputs and clinically grounded thresholds.

Phenotyping and surgical planning: Phenotyping and planning-oriented models [22,23,24,38] align AI outputs with decisions that change care, such as anticipating DIE extent, organ involvement, and operative complexity. In principle, this application offers higher translational value than binary diagnosis because it connects prediction to workflow planning, risk communication, and resource allocation. However, it also demands more rigorous evaluation, including lesion site coverage, robustness across protocols, and validation against surgical reference standards when claims relate to operative findings.

Outcomes prediction: Finally, clinical outcome prediction [51] represents an early step toward linking imaging-derived signals to patient-centered outcomes. While potentially valuable for personalized counseling and management, this area remains nascent and requires broader validation and careful confounding control before it can inform treatment pathways beyond diagnosis.

4.1.2. Modality-Specific Evidence and Development Considerations

Ultrasound: Ultrasound dominated the evidence base and was used for both diagnosis and differential diagnosis tasks, including adnexal classification against other pelvic/ovarian pathology [28,33,35,38,42]. Ultrasound’s operator dependence and variability in acquisition highlight why AI could add value as a standardization tool, but also explain why generalizability is challenging: models may learn site-specific acquisition patterns or reader conventions unless validated across centers and expertise levels.

Endoscopic video (laparoscopy/hysteroscopy): Endoscopic video pipelines were explored for lesion/organ identification and, in a subset, intraoperative guidance workflows [27,30,32]. This modality is uniquely positioned for intraoperative decision support because it provides real-time visual access to lesion appearance; however, it also introduces temporal correlation and strong within-case redundancy that can inflate performance if evaluation is not carefully partitioned. As a result, evidence maturity for video applications depends heavily on patient-/video-level evaluation and explicit leakage safeguards.

MRI: A smaller subset applied AI to pelvic MRI for endometriosis assessment [21,24,29,34], including DIE-focused cohorts [21,24]. MRI offers richer anatomical context and is relevant for deep disease mapping and surgical planning, but heterogeneity in sequences and protocols across scanners can strongly affect model behavior. This strengthens the case for multi-center evaluation and calibration assessment when MRI-derived probabilities are intended for decision support.

Taken together, these findings indicate that AI for endometriosis imaging is advancing across multiple points in the care pathway, but development is uneven: diagnosis-oriented classification dominates, while spatial mapping and clinically integrated planning/intraoperative support remain less mature. Modality-specific constraints further emphasize the need for tailored validation standards and benchmarks before routine clinical implementation.

4.2. Methodological Gaps and Translational Barriers

Although the field is growing rapidly, several recurring methodological limitations constrain interpretability, generalizability, and clinical translation. First, data structure and partitioning practices represent a central threat to validity in imaging AI. Endometriosis imaging frequently involves multiple correlated samples per patient (multiple ultrasound images, MRI slices/series, or video frames). If partitions are performed at the image/frame level rather than the patient level, visually similar content from the same patient can leak across training and evaluation sets, inflating headline performance. This issue is particularly salient for laparoscopic video and multi-slice MRI, where temporal and spatial correlation is strong. Our minimal AI method quality appraisal (Table 5) shows that explicit confirmation of patient-level separation and explicit leakage safeguards were not consistently reported across studies, meaning that, for a substantial subset of the literature, the degree of protection against leakage cannot be verified. Consequently, even when reported accuracy or AUC appears high, these results may represent upper-bound estimates rather than robust performance likely to generalize across settings.

Second, reference standards and labeling practices were heterogeneous and often misaligned with the translational claims made. Nearly 60% of studies relied on expert imaging assessment as the reference standard, meaning soft labels based on radiologist or sonographer interpretation and imaging reports, while only a minority incorporated hard labels anchored in operative confirmation and or histopathology. Imaging only soft labels may be appropriate for triage-oriented tools that aim to emulate routine imaging interpretation, but they risk circularity when models are trained to reproduce the judgments that generated the labels, particularly when labeling is derived from routine reports rather than structured expert rereads, when blinding is not described, or when adjudication procedures are absent. In such settings, models may learn local reading conventions and acquisition habits rather than disease status, limiting transportability to centers with different protocols, expertise distributions, or reporting templates. The limited reporting of inter-rater agreement, label quality control procedures (e.g., double reading, adjudication, and consensus), and explicit handling of label uncertainty further reduces confidence in ground-truth reliability and makes it difficult to interpret discordant findings across studies.

Third, evaluation practices were often misaligned with clinical decision making. Internal validation typically relied on simple hold-out splits or k-fold cross-validation, while temporal, geographic, or fully external validation was rarely reported (Table 5). Moreover, performance reporting was frequently dominated by accuracy, sensitivity, and ROC-AUC, which are insufficient to establish clinical utility. For triage applications, clinically meaningful evaluation requires operating points that prioritize sensitivity and quantify downstream implications (e.g., referral volume and false-positive burden), whereas surgical planning and mapping require spatial fidelity, phenotype- and site-specific performance, and failure characterization under real-world artifacts (motion, bowel gas, smoke, and bleeding). Calibration reporting, which is essential when probability estimates guide referral urgency, counseling, or risk communication, was uncommon (Table 5), and uncertainty and precision reporting such as confidence intervals or variability across folds was inconsistently provided.

Fourth, translational and implementation considerations were rarely addressed. Most studies relied on private, institution-specific datasets and were concentrated in a small number of countries, increasing concerns about algorithmic bias and limited applicability to other populations, scanners, and care pathways. Almost all work stopped at retrospective evaluation; prospective trials, real-world impact studies, and cost-effectiveness analyses were absent, leaving major evidence gaps regarding effects on diagnostic delay, surgical planning accuracy, operative efficiency, complications, patient-reported outcomes, and resource utilization. Issues central to adoption and regulation, including user-centered design, explainability aligned with clinician needs, inference time, monitoring for distribution shift, and data governance, were seldom described. Without these components, even technically promising models remain difficult to assess for feasibility, safety, and regulatory readiness.

Finally, modality-specific implications require explicit consideration. The nature of methodological risk differs by modality and should guide both reporting expectations and benchmark design. In ultrasound and laparoscopic video, repeated views and temporal correlation heighten leakage risk; accordingly, patient- and video-level partitioning and explicit safeguards against overlap are essential. In MRI, protocol heterogeneity across scanners, sequences, and institutions can dominate model behavior, increasing the need for external/temporal validation, calibration assessment, and subgroup analyses by acquisition characteristics. These modality-specific constraints argue against a “one-size-fits-all” validation approach and motivate modality-tailored reporting standards and external validation strategies.

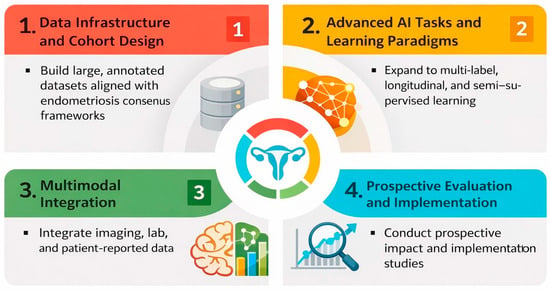

4.3. Future Directions in AI for Endometriosis Imaging

Future research should prioritize prospective, multi-center collaborations that assemble large, diverse imaging cohorts spanning the full spectrum of endometriosis phenotypes, life stages, and care settings. Harmonized reporting of lesion location, disease stage, and reference standards, ideally aligned with existing endometriosis classification and imaging consensus frameworks, will be critical to enable meaningful comparison, benchmarking, and meta-research. Publicly accessible, well-annotated datasets would accelerate reproducibility and reduce fragmentation, while transparent documentation of acquisition protocols and labeling pipelines would improve interpretability across sites.

Methodologically, there is clear scope to move beyond narrow binary classification toward richer tasks that better mirror clinical decision making: multi-label phenotyping, combined detection–segmentation pipelines for lesion mapping, longitudinal response assessment, and prediction of operative complexity or symptom trajectories. Vision transformer and hybrid CNN–transformer architectures, along with self-supervised and semi-supervised learning, may help leverage large volumes of unlabeled ultrasound and laparoscopic video generated in routine care. Vision–language models that link images with radiology/sonography reports and histopathology could support explainable lesion descriptions, automatic structured reporting, and cross-modal retrieval. Multimodal models that integrate imaging with clinical, laboratory, biomarker, and patient-reported data may further enable individualized risk stratification and treatment selection.

To strengthen clinical translation, we propose a staged research agenda. Near-term priorities include consistent reporting of split unit, explicit patient-level separation, leakage safeguards, uncertainty/precision (including confidence intervals), and calibration when probabilities are used; evaluation should increasingly emphasize clinically relevant thresholds, decision curve analysis, and systematic failure analyses. Mid-term priorities include external and temporal validation across diverse scanners and protocols, with prespecified subgroup analyses by phenotype, lesion location, imaging quality, and reference standard (imaging-only vs. surgery/histopathology confirmation). Long-term priorities include prospective impact studies with human–AI interaction components and health–economic evaluation to determine whether AI reduces diagnostic delay, improves mapping and surgical planning, optimizes operative workflows, and benefits patient-centered outcomes equitably across settings. Long-term priorities also include advancing multimodal models that integrate imaging with clinical variables, laboratory biomarkers, patient-reported outcomes, and omics data to enable biologically informed phenotyping, risk stratification, and personalized treatment selection. Figure 5 summarizes future directions in AI for endometriosis imaging.

Figure 5.

Future research directions for AI in endometriosis imaging.

Finally, future evidence syntheses should move beyond landscape mapping toward comparative evaluation where feasible. Reference-standard–stratified assessment is a priority direction for follow-up systematic reviews and meta-analyses, in which improved homogeneity and harmonized endpoints may support clinically meaningful subgroup comparisons (e.g., surgery/histopathology confirmation versus imaging-only expert assessment) and more robust translational conclusions.

4.4. Review Limitations

This scoping review has a few limitations. We restricted inclusion to English-language publications and to studies indexed in selected databases up to November 2025; relevant work in other languages, preprints, or gray literature may have been missed. As a scoping rather than systematic review, we did not perform formal risk-of-bias assessment or quantitative meta-analysis; the pronounced heterogeneity in imaging modalities, endometriosis phenotypes, outcomes, and performance metrics would, in any case, limit statistical pooling.

5. Conclusions

The clinical application of AI in endometriosis imaging is rapidly evolving yet remains at an early stage of development. Existing studies demonstrate proof-of-concept models for diagnosing pelvic endometriosis, segmenting lesions, and supporting surgical planning, predominantly using ultrasound and laparoscopic imaging with CNN-based architectures. However, most work relies on retrospective, single-center datasets, internal validation only, and heterogeneous reporting, limiting generalizability and real-world readiness. To move beyond promising prototypes, future research must prioritize larger, diverse and well-annotated cohorts, robust external and prospective validation, and multimodal, clinically integrated models.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ai7020043/s1, Supplementary Material S1: Data Extraction Form. Supplementary Material S2: Appraisal Items and Decision Rules. Supplementary Material S3: Characteristics of the Included Studies. Supplementary Material S4: Endometriosis Context and Phenotype. Supplementary Material S5: Imaging Data Characteristics. Supplementary Material S6: AI Model Characteristics.

Author Contributions

Study Design: R.A., R.T., T.F. and S.A.; Database Search: R.A.; Study Screening: R.A. and A.E.; Data Extraction: R.A. and A.E.; Data Synthesis: R.A. and R.T.; Manuscript Writing: R.A. Manuscript Review: R.T., T.F. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Code availability: This study did not involve the utilization of any custom code or mathematical algorithm.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ROC-AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DIE | Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis |

| HER | Electronic Health Record |

| F1-score | Harmonic Mean of Precision and Recall |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GLENDA | Gynecologic Laparoscopy ENdometriosis DAtaset |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| N/A | Not Applicable |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PCC | Population–Concept–Context |

| POD | Pouch of Douglas |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TVUS | Transvaginal Ultrasound |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

References

- World Health Organization. Endometriosis—Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Sun, X.; He, L.; Wang, S. Knowledge and awareness of endometriosis among women in Southwest China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y. Global and regional trends in the burden of surgically confirmed endometriosis from 1990 to 2021. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2025, 23, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, U.B.; Bank-Mikkelsen, A.S.; Rytter, D.; Hartwell, D.; Marschall, H.; Nyegaard, M.; Seyer-Hansen, M.; Hansen, K.E. Understanding endometriosis underfunding and its detrimental impact on awareness and research. npj Women’s Health 2024, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, F.; Schwander, A.; Vaineau, C.; Knabben, L.; Nirgianakis, K.; Imboden, S.; Mueller, M.D. True Prevalence of Diaphragmatic Endometriosis and Its Association with Severe Endometriosis: A Call for Awareness and Investigation. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, M.; Moghadam, M.N.; Safari, M.; Chaichian, S.; Kashi, A.M.; Afshari, M.; Sadegi, K. The impact of early diagnosis of endometriosis on quality of life. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025, 311, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Feng, H.; Ye, Q. Factors contributing to the delayed diagnosis of endometriosis-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1576490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Corte, P.; Klinghardt, M.; von Stockum, S.; Heinemann, K. Time to Diagnose Endometriosis: Current Status, Challenges and Regional Characteristics—A Systematic Literature Review. BJOG 2025, 132, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beloshevski, B.; Shimshy-Kramer, M.; Yekutiel, M.; Levinsohn-Tavor, O.; Eisenberg, N.; Smorgick, N. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of adolescents and young women with suspected endometriosis. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 53, 102737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, J.; Harma, K.; Reid, S.; Rao, T.; Lo, G.; Yang, N.; Karia, S.; Lee, E.; Borok, N. Endometriosis: A multimodal imaging review. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 158, 110610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.W.; Jha, P.; Chamie, L.; Rodgers, S.; Kho, R.M.; Horrow, M.M.; Glanc, P.; Feldman, M.; Groszmann, Y.; Khan, Z.; et al. Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus on Routine Pelvic US for Endometriosis. Radiology 2024, 311, e232191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, F.; Battaglia, C.; Bruno, I.; Ammendola, M.; Navarra, G.; Currò, G.; Laganà, D. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Planning of Surgical Treatment of Deep Pelvic Endometriosis. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 944399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausic, A.I.G.; Matasariu, D.R.; Manu, A.; Bratila, E. Transvaginal Ultrasound vs. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: What Is the Optimal Imaging Modality for the Diagnosis of Endometriosis? Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, P.; Shrestha, B.; Sherestha, J.; Chen, J. Current Status and Future Potential of Machine Learning in Diagnostic Imaging of Endometriosis: A Literature Review. J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2025, 63, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yi, X. Recent advancements of artificial intelligence in minimally invasive surgery for endometriosis. Intell. Surg. 2025, 8, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Tong, A.; Young, S.; Jha, P. Artificial intelligence applications in endometriosis imaging. Abdom. Radiol. 2025, 50, 4901–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivajohan, B.; Elgendi, M.; Menon, C.; Allaire, C.; Yong, P.; Bedaiwy, M.A. Clinical use of artificial intelligence in endometriosis: A scoping review. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungate, B.; Tucker, D.R.; Goodwin, E.; Yong, P.J. Assessing the Utility of artificial intelligence in endometriosis: Promises and pitfalls. Womens Health 2024, 20, 17455057241248121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balica, A.; Dai, J.; Piiwaa, K.; Qi, X.; Green, A.N.; Phillips, N.; Egan, S.; Hacihaliloglu, I. Augmenting endometriosis analysis from ultrasound data using deep learning. In Medical Imaging 2023: Ultrasonic Imaging and Tomography; SPIE: Bellingham, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; To, M.-S.; Condous, G.; Leonardi, M.; Knox, S.; Avery, J.; Hull, M.L.; Carneiro, G. The effectiveness of self-supervised pre-training for multi-modal endometriosis classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Ji, Z.; Liu, Y. Identification and validation of a novel machine learning model for predicting severe pelvic endometriosis: A retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysa, N.; Lamprini, C.; Maria-Konstantina, C.; Constantinos, K. Deep Learning Improves Accuracy of Laparoscopic Imaging Classification for Endometriosis Diagnosis. J. Clin. Med. Surg. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, W.K.R.; Silva, A.C.; de Paiva, A.C.; Diniz, J.O.B.; Brandão, A.; Oliveira, M.A.P. Automatic segmentation of deep endometriosis in the rectosigmoid using deep learning. Image Vis. Comput. 2024, 151, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamsarian, N.; Wolf, S.; Zinkernagel, M.; Schoeffmann, K.; Sznitman, R. Deeppyramid+: Medical image segmentation using pyramid view fusion and deformable pyramid reception. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2024, 19, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, S.; Pascual, M.; Ajossa, S.; Neri, M.; Musa, E.; Graupera, B.; Rodriguez, I.; Alcazar, J.L. Artificial intelligence (AI) in the detection of rectosigmoid deep endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 261, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.; de Zulueta, P.R.; Spagnolo, E.; Soguero, C.; Cristobal, I.; Pascual, I.; López, A.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Deep learning to measure the intensity of indocyanine green in endometriosis surgeries with intestinal resection. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, K. Ultrasound image-based deep learning to differentiate tubal-ovarian abscess from ovarian endometriosis cyst. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Xie, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Yin, Y. Diagnosis and nursing intervention of gynecological ovarian endometriosis with magnetic resonance imaging under artificial intelligence algorithm. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 3123310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaya, K.; Yasuo, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Morita, Y.; Hamazaki, A.; Murayama, S.; Mihara, T.; Mihara, M. Construction of deep learning-based convolutional neural network model for automatic detection of fluid hysteroscopic endometrial micropolyps in infertile women with chronic endometritis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 297, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibetseder, A.; Schoeffmann, K.; Keckstein, J.; Keckstein, S. Post-surgical Endometriosis Segmentation in Laparoscopic Videos. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Content-Based Multimedia Indexing (CBMI), Lille, France, 28–30 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leibetseder, A.; Schoeffmann, K.; Keckstein, J.; Keckstein, S. Endometriosis detection and localization in laparoscopic gynecology. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 6191–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wen, L.; Huang, R.; Ni, D. Multi-purposed diagnostic system for ovarian endometrioma using CNN and transformer networks in ultrasound. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2024, 91, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Alpuing Radilla, L.A.; Khalaj, K.; Dawoodally, H.; Mokashi, C.; Guan, X.; Roberts, K.E.; Sheth, S.A.; Tammisetti, V.S.; Giancardo, L. A Multi-Modal Pelvic MRI Dataset for Deep Learning-Based Pelvic Organ Segmentation in Endometriosis. Scientific Data 2025, 12, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cai, W.; Zhou, C.; Tian, H.; Wu, B.; Zhang, J.; Yue, G.; Hao, Y. Ultrasound radiomics-based artificial intelligence model to assist in the differential diagnosis of ovarian endometrioma and ovarian dermoid cyst. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1362588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maicas, G.; Leonardi, M.; Avery, J.; Panuccio, C.; Carneiro, G.; Hull, M.L.; Condous, G. Deep learning to diagnose pouch of Douglas obliteration with ultrasound sliding sign. Reprod. Fertil. 2021, 2, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, B.D.; Nirgianakis, K.; Ma, L.; Wotzkow, C.A.; Steiner, S.; Blank, F.; Mueller, M.D. Computer-aided histopathological characterisation of endometriosis lesions. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, N.; Dong, X. Discriminative diagnosis of ovarian endometriosis cysts and benign mucinous cystadenomas based on the ConvNeXt algorithm. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 298, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podda, A.S.; Balia, R.; Barra, S.; Carta, S.; Neri, M.; Guerriero, S.; Piano, L. Multi-scale deep learning ensemble for segmentation of endometriotic lesions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 14895–14908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahrim, M.; Abdul Aziz, A.N.; Wan Ismail, W.Z.; Ismail, I.; Jamaludin, J.; Rao Balakrishnan, S. Automatic feature description of Endometrioma in Ultrasonic images of the ovary. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, D.L.; Sidhom, S.; Chatham, C.E.; Tillotson, S.G.; Zapata, R.D.; Modave, F.; Solly, M.; Quevedo, A.; Moawad, N.S. Utilizing Artificial Intelligence: Machine Learning Algorithms to Develop a Preoperative Endometriosis Prediction Model. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2025, 32, 784–792.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, R.-A.; Ștefan, P.-A.; Mihu, C.M.; Csutak, C.; Melincovici, C.S.; Crivii, C.B.; Maluțan, A.M.; Hîțu, L.; Lebovici, A. Ultrasonography in the differentiation of endometriomas from hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: The role of texture analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visalaxi, S.; Muthu, T.S. Automated prediction of endometriosis using deep learning. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2021, 12, 2403–2416. [Google Scholar]

- Visalaxi, S.; Sudalaimuthu, T.; Sowmya, V.J. Endometriosis Labelling using Machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Communication, Computing and Industry 6.0 (C216), Bangalore, India, 15–16 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, A.; Zheng, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhang, X. Development and Validation an AI Model to Improve the Diagnosis of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis for Junior Sonologists. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2025, 51, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; He, S.; Lin, Y. Diagnostic efficacy of ultrasound combined with magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis of deep pelvic endometriosis under deep learning. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 7598–7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.A.; Chouvatut, V.; Phongnarisorn, C. Endometriosis Lesion Classification Using Deep Transfer Learning Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2025, 16, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.A.; Chouvatut, V.; Phongnarisorn, C.; Praserttitipong, D. Deep learning based detection of endometriosis lesions in laparoscopic images with 5-fold cross-validation. Intell.-Based Med. 2025, 11, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Butler, D.; Smart, B.; Xie, Y.; To, M.-S.; Knox, S.; Condous, G.; Leonardi, M.; Avery, J.C. Unpaired multi-modal training and single-modal testing for detecting signs of endometriosis. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2025, 124, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Butler, D.; To, M.-S.; Avery, J.; Hull, M.L.; Carneiro, G. Distilling missing modality knowledge from ultrasound for endometriosis diagnosis with magnetic resonance images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 18–21 April 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zorlu, U.; Yılmazer-Zorlu, S.N.; Halilzade, İ.; Turgay, B.; Ünsal, M. Shear wave elastography values in endometrioma: Clinical findings and machine learning-based prediction models. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025, 171, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.