Abstract

Τhe trophic ecology of Pterois miles in the Mediterranean Sea was performed by integrating data from stomach contents (SCA) and stable isotopes analyses (SIA), based on samples caught off the Greek island of Rhodes, SE, Aegean Sea, for the first time. This combined approach provides information on ingested (SCA) and assimilated (SIA) food and thus allows for the depiction of predator–prey relationships. Specimens of devil firefish, including both juveniles and adults (total length of analyzed specimens spanned from 11.40 to 31.50 cm), were collected from different sites around Rhodes. Their diet consisted of bony fish, cephalopods, crustaceans, and gastropods. The δ13C and δ15N values ranged from −18.0 ‰ to −14.4 ‰ and from 7.2 ‰ to 9.2 ‰, respectively. SIA data allowed for the estimation of the trophic position of devil firefish from Rhodes Island, which showed a mean value of 3.1 ± 0.6 and confirms that the species primarily relies on a benthic baseline. Further, our isotopic values approach those obtained in North Carolina and Bermuda, confirming its role as a mesopredator in the Mediterranean benthic food webs. Although preliminary, such results can provide an important baseline for future investigations on the species and the potential impact on the Mediterranean food webs.

1. Introduction

Within an invaded area, alien species are considered one of the major threats to global biodiversity, having the potential to directly consume or outcompete native species, alter habitats, and affect ecosystem structure and function [1,2,3,4]. Many alien species that were introduced into the Eastern Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal are thermophilic [5]. The devil firefish Pterois miles (Bennett, 1828) was first recorded in 1991 off the Israeli coasts [6], and two decades later it rapidly invaded the Eastern Mediterranean and spread as far as Tunisia and southern Italy (Sicily) in the central Mediterranean [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Currently, in the Southern Aegean waters, P. miles, the species, was frequently found in fishing nets, and sightings in shallow waters exponentially increased [13].

The biological and ecological traits of P. miles in the Mediterranean Sea are the focus of an increasing scientific interest ranging from surveys to field and laboratory experiments on population structure [14,15,16], local knowledge and awareness [17,18], distribution [7], and distribution modeling [11,19]. Among these traits, information on the trophic habits of this species is of relevance to ecological impact quantification and management support. Preliminary data suggested that the devil firefish in the new Mediterranean environment maintain the feeding habits consistent with those documented in their native range and in their established populations in the western Atlantic [20,21].

Outside the Mediterranean, the diet of the invasive P. miles and its congeneric Pterois volitans (Linnaeus, 1758) has been studied mainly in the invaded temperate and tropical western Atlantic. The stomach content analysis (SCA) suggested a generalist carnivorous diet [22]. Moreover, stable isotope analyses (SIA) were used to investigate the diet of the congeneric invasive P. volitans in the Southeast US Atlantic Ocean [23], the Colombian Caribbean regions [24], and the Bahamas [25,26]. The results offered additional information on its trophic status [27], corroborating the feeding behavior of a generalist carnivore, with a preference for bony fish [23].

The use of both conventional dietary analysis and SIA methods allows having a comprehensive view of a species’ diet. While SCA provides only a short-term picture of the diet in a precise moment [28], SIA gives integrated information over a long period of time. Further, a main drawback of the SCA is that the recovered prey items are often partially digested and therefore difficult to identify, whereas high frequencies of empty stomachs may necessitate large sample sizes [29]. Such methodological issues can be potentially resolved by using SIA [30]. Numerous studies demonstrate how effective SIA has been applied to disentangling the food web structure in an environment and in providing information on assumed food vs. ingested, as for SCA [23,26,27,31].

The estimation of trophic position (TP) can also be measured by SIA and simulate the capture of complex trophic interactions through the reticulate pathways of ecological communities [32], therefore contributing to food-chain theory [33]. SIA has been used to assess the effects of biological invasion on the native food web structure [34], also in the Mediterranean Sea [31,35], and to estimate the trophic position of a species with difficulties in diet quantification [36].

Information on the biology and ecology of non-indigenous species is required to interpret the mechanisms by which introduced species become established and invasive [37]. Discovering strategies of such invasions comprises a crucial step for mitigating their impacts [37]. In this context, the main aim of this study was to provide new information on the trophic habits of P. miles in the Eastern Mediterranean basin based on both stomach contents (ingested food) and SIA (assimilated food), and to provide preliminary data on the structure of the predator–prey relationship.

2. Materials and Methods

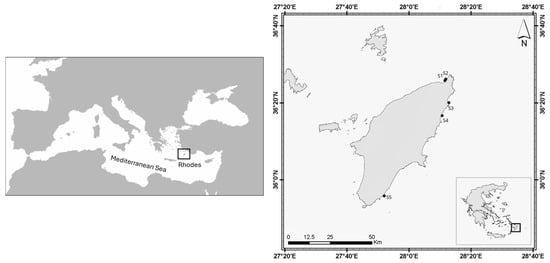

A total of 26 individuals of P. miles were collected from five different locations along the coasts of Rhodes Island, Greece (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of sampling sites around the island of Rhodes in Greece. The five sampling sites are depicted with black dots (S1: Kritika; S2: Kritika; S3: Faliraki; S4: Afandou; S5: Plimmiri).

Specimens were captured by seining and static fishing nets used by local registered fishing vessels, at 2–50 m of depth from October 2019 to January 2020. All individuals were stored in the freezer (−20 °C) till further analysis. For the identification of P. miles, the method outlined by [38] was followed. In brief, the following parameters were determined for each individual: total (TL) and standard (SL) lengths with an electronic vernier (accuracy ± 0.01 cm), sex (unsexed, females, and males), total wet weight (TW), and net weight (NW) after devil firefish internal organ removal (accuracy ± 0.01 g).

Each stomach, including its contents (SW), and the net stomach weight (NSW) after emptying the contents into a Petri dish, were determined with an accuracy of ±0.01 g. Based on [39], the difference between SW and NSW provides the food weight (FW): FW (g) = SW (g) − NSW (g). The fullness index (FI) was expressed as a percentage of the ratio of the total fish weight (W) and ingested food weight (FW): FI = FW/W × 100 [40]. The feeding intensity of devil firefish was determined by the vacuity index (VI) expressed as VI = total number of empty stomachs observed/total number of the stomachs examined × 100 [41].

The contents of the gastrointestinal tracts were preserved in 70% ethanol. Prey items were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible using a Leica S6D stereoscope, following the methods of [42,43]. When prey items were highly digested, and thus unidentified (in the case of fishes), the presence of otoliths permitted the assignment of unidentified remains to a fish species, according to the AFORO database (Anàlisi de Formes d’Otòlits) database (i.e., http://aforo.cmima.csic.es/, accessed on 10 March 2020; [44]).

Prey items found in the stomach content were counted, measured, and weighed with an accuracy of ±0.01 cm and ±0.01 g, respectively. The frequency of occurrence (% F) of the various prey items found in one or more gastrointestinal tracts (F) is expressed as a percent of the total number of devil firefish stomachs used for the diet analysis [29]. Additionally, the percentage of numerical abundance (% N) (i.e., percentage of prey in relation to the total number of prey items counted in all the stomachs containing food), the percentage of gravimetric composition (% W) (i.e., percentage of the prey weight in relation to the total weight of prey items counted in all the stomachs containing food) were calculated, and the index of relative importance (IRI) was determined as IRI = (% N + % W) × % F.

For SIA, a portion of white muscle close to the dorsal fin from each specimen was extracted and oven-dried at 60 °C for 24–48 h and then stored in the freezer at −20 °C until further processing. Subsequently, the defrosted samples were ground into a homogenous fine powder using an agate mortar and pestle. Approximately 1 mg was weighed with a Mettler Toledo balance (accuracy to 0.001 mg) and put into tin capsules. The same process was followed by all identified prey taxa from the SCA. The δ13C and δ15N ratios in the samples were determined using a Delta V Plus Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), coupled in a continuous flow to a Thermo Flash EA 1112 elemental analyser (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA), for the determination of total carbon and nitrogen at the Laboratory of Stable Isotope Ecology of the University of Palermo (Italy).

Stable isotope ratio was expressed, in relation to reference international standards (atmospheric N2 and Vienna PeeDee Belemnite for δ15N and δ13C, respectively), as

where R is the 13C/12C or 15N/14N, respectively. Analytical precision based on standard deviations of internal standards (International Atomic Energy Agency IAEA-CH-6; IAEA-NO-3; IAEA-N-2) ranged from 0.10 to 0.19‰ for δ13C and 0.02 to 0.08‰ for δ15N. Since lipids were not extracted from the samples prior to SIA, a relationship was used between C/N ratios and δ13C ratios to evaluate the effect of lipids on the isotopic value. The bulk δ13C values were normalized for lipid concentration according to the model proposed by [32] when C/N was >3.0. The δ13C lipid-free values obtained were compared afterwards with the δ13C bulk with a paired t-test. Correlation analysis was then performed between δ15N and δ13C vs. the total length of the fish to assess if any changes in the isotopic signatures with size occur. The differences in terms of the isotopic values between sexes were determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test in R.

δ13C or δ15N = (Rsample/Rstandard) × 1000

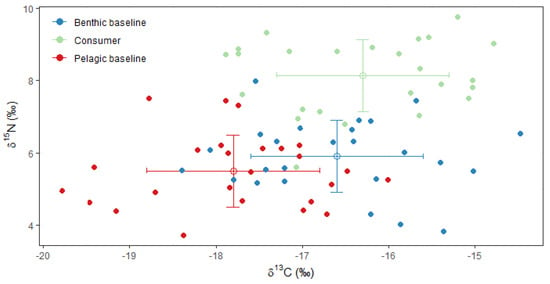

A dual Bayesian approach that included a stable isotope mixing model was used for the calculation of the trophic position (TP) of the devil firefish. Specifically, the package tRophicPosition in R (version 0.7.7.) was used for the estimation of TP for P. miles based on δ13C and δ15N values. The model applies Markov Chain Monte Carlo Simulations for stable isotope data to estimate TP [45]. The full baseline model that incorporates the factor α [32] was selected, and the stomach content findings were used as baseline organisms. For the pelagic baseline, the isotopic values of Apogon sp., Spicara smaris, Chromis chromis, Serranus hepatus, and those from an unidentified pelagic Actinopterygii were selected to represent the pelagic resource. The benthic resources represented the second baseline, and these included Gobius sp., Scorpaena sp., the gastropod Turritella sp., the isopod Nerocila orbignyi, and the cephalopod Sepia officinalis. For the trophic enrichment factor (TEF) a standard values of 0.5‰ ± 0.85‰ for δ13C and 3.39‰ ± 0.98‰ for δ15N were applied from the inbuilt bibliography in tRophicPosition [32,45,46]. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations were run through 20,000 iterations and a burn-in of 20,000 with four chains.

To discriminate between two distinct sources of C and N for pelagic vs. benthic, two equations were used:

where δ15Nc is the nitrogen isotopic ratio of the predator (devil firefish), δ15N b1 is the nitrogen isotopic ratio of the first baseline (pelagic), and δ15N b2 is the nitrogen isotopic ratio of the second baseline (benthic). The trophic enrichment factor (TEF) is ΔΝ for nitrogen, TP is the trophic position of the P. miles, and λ is the trophic position of the baseline [47] for the first equation. Furthermore, for the second equation the model uses a secondary mixing model to calculate α, which accounts for the fraction in δ13C and estimates the relative contribution of each source to the devil firefish trophic position, where additional variables δ15N b1, δ13C b1, δ15N b2, and δ13C b2 refer to the δ15N and δ13C values of baselines one and two, respectively, and α is the proportion of N derived from baseline one [32,34,45]. The full model is based on Equation (1); however, α includes the trophic discrimination factor (TDF) for carbon based on Equation (3):

where the additional variables δ13Cc is the δ13C value of the devil firefish, and ΔC is the TDF for C [45] modified from [32]. The Bayesian approach allows the equations, which both include TP and α, to be solved iteratively, with δ13C and δ15N values and TEFs for predators and baselines modeled as random variables with vague prior normal distributions of their means [dnorm(0,τ), τ = 1 × SD2(−1)] and vague prior uniform distributions of their standard deviations [dunif(1,100)]. The C and N observations of P. miles, baselines, and TDFs are randomly modeled variables, and TP and α are also treated as random parameters [45].

δ15N_c = ΔΝ(TP + λ) + α (δ15N_b1+ δ15N_b2) − δ15N_b2

δ13C_c = δ13C_b1+ δ13C _b2 (1 − a)

a = (((δ13C_b2 − (δ13C_c + ΔC))/((δ13C_b2 + δ13C_b1)))

Based on [48], the selection for the most appropriate TEFs for the predator (devil firefish) was simulated by a Monte Carlo simulation of stable isotope mixing polygons, with 1000 iterations for the Stable Isotope Mixing Model. Furthermore, any samples that fall within the polygon in <5% of iterations should be excluded from the mixing model [48].

Finally, the R package 0.5.1.217. simmr [49] was used to correlate the dietary proportions of devil firefish samples with various food resources, as elucidated by the qualitative SCA, using the estimated stable isotope values from the species tissue samples. Calculation included the dual stable-isotope data (δ13C and δ15N) of the tissues of P. miles specimens and the sources (Gobius sp., Turritella sp., Sepia officinalis, and Spicara smaris). For TEF measurements, the Δ13C = 0.01‰ ± 1.01 and Δ15N = 3.4‰ ± 0.99 were calculated based on the available bibliography [32,45,46].

3. Results

Out of the 26 specimens of P. miles, 7 were females, 11 males, and 8 juveniles. The total length varied from 11.40 cm to 31.50 cm (mean ± SD: 22.38 ± 6.38 cm), and the total weight ranged from 9.3 g to 625.4 g (mean ± SD: 191.2 g ± 154.99 g).

The fullness index (FI) for the total number of P. miles was 1.29%, and the vacuity index (VI) was 46.15%. According to IRI, the three most important fish families in the devil firefish diet were Gobiidae, Centracanthidae, and Pomacentridae. A high proportion of empty stomachs was observed (12 stomachs, 46%).

The majority of the 36 individual prey items were bony fish (26 items, 72%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of the taxa identified in Pterois miles stomach contents, in terms of % N, % W, % F, and % IRI.

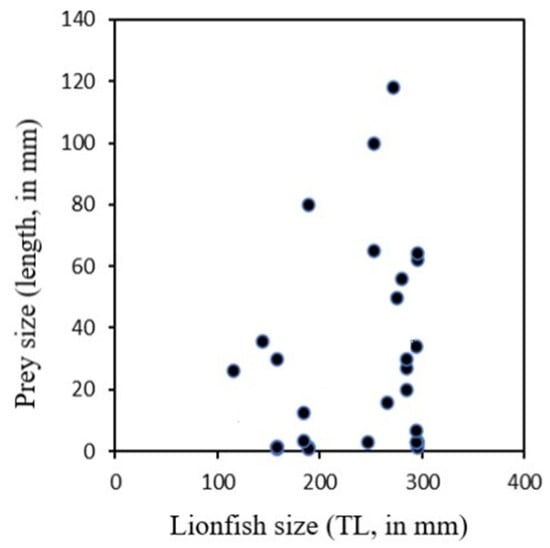

For Actinopterygii, the Gobiidae family contributed the most by number and by weight (% N = 22.2, % W = 37.0); the rest of the Actinopterygii families had 33.3% N and 22.5% W. Other prey items included mollusks (six items, 17% N) and crustaceans (three items, 11% N) (Table 1). Devil firefish of different sizes fed on a wide range of prey sizes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prey size in respective length of the consumers (Pterois miles) from Rhodes Island, Greece.

Otolith identification allowed the classification of Serranus hepatus and Gobius niger as prey.

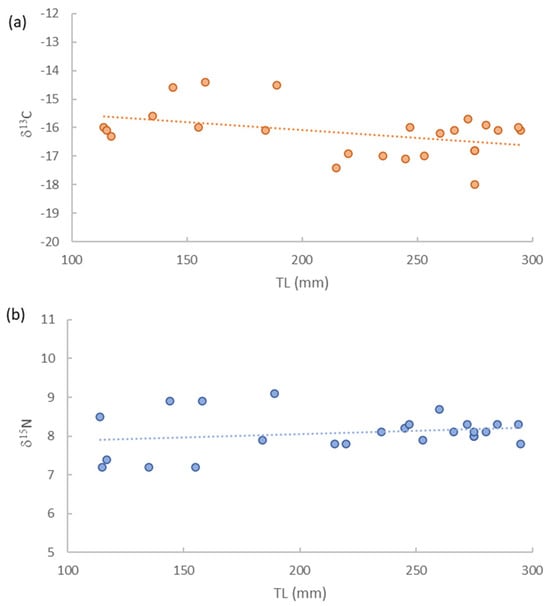

The δ13C and δ15N values for the total devil firefish samples varied from −18.0‰ to −14.4‰ and from 7.2‰ to 9.2‰, respectively. For juveniles, the isotopic value of δ13C ranged from −16.4‰ to −14.4‰ and for δ15N from 7.2‰ to 9.2‰. Female devil firefish isotopic values δ13C varied from −18.3‰ to −15.8‰, and for δ15N from 7.9‰ to 8.4‰. For male specimens, the δ13C isotopic values had a range from −17.6‰ to −15.8‰, and for δ15N from 7.8‰ to 8.7‰. The correlation analysis showed a significant increase of δ15N with increasing size TL (Pearson R = 0.44, p < 0.001), while δ13C significantly decreased with increasing TL (R = −0.43, p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Isotopic values δ15N (a) and δ13C (b) vs. total length (TL) for Pterois miles.

The δ13C values revealed a significant difference between the unsexed vs. the females and males (ANOVA test, p < 0.05). However, the δ13C value did not show a significant difference between males and females (p > 0.05). For the δ15Ν, no significant differences were detected between sexes. Prey taxa δ13C values ranged from −18.8‰ (Gobius sp.) to −12.8‰ (Turritella sp.). Prey taxa δ15N varied from 4.7‰ (Gobius sp.) to 7.7‰ (G. niger). The Actinopterygii class tended to have higher δ15N values than crustaceans and mollusks.

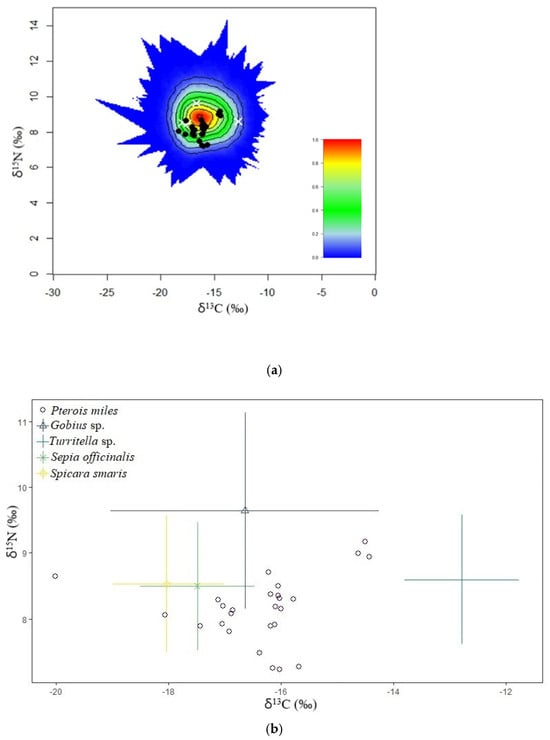

According to the mixing polygon (Figure 4a), all the specimens were within the 95% mixing region (the outermost contour). Conversely, the lowest δ13C isotopic value (−18.3‰) belonged to a female devil firefish (TL = 275 mm and TW = 269 g), whereas the highest δ13C value (−14.4‰) belonged to an unsexed devil firefish (TL = 158 mm and TW = 33.61 g). For the δ15N isotopic value, the lowest (7.2‰) belonged to an unsexed devil firefish (TL = 155 mm and TW = 32.7 g). The highest δ15N value (9.2‰) was also detected on an unsexed devil firefish (TL = 189 mm and TW = 73.9 g). The simmr confirmed P. miles relies mostly on teleosts rather than invertebrates (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) The simulated mixing region for the biplot shown in (b), the positions of the devil firefish (black dots) and the average source signatures (white crosses) are shown. Black dots represent individual predator values, and white crosses indicate mean source signatures. (b) A biplot of stable isotopic signatures for the predator Pterois miles and resources (Gobius sp., Sepia officinalis, Turritella sp., Spicara smaris). This biplot was created using the Bayesian mixing model simmr. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals and incorporate errors in the source isotopic signatures and in trophic enrichment factors.

Devil firefish occupied an extended position in the marine food web (Figure 5). Additionally, it is 2.1‰ above the benthic resource and 2.6‰ above the pelagic ones in terms of δ15N. The results from the two-baseline full model revealed a mean TP of 3.1, with a minimum of 2.6 and a maximum of 3.8. An alpha value of 0.06 occurred for the full baseline model, which means that each baseline provides 6% of the energy inputs to the P. miles.

Figure 5.

Trophic position of devil firefish (consumer) vs. the benthic and pelagic baselines.

4. Discussion

The current study offers an insight into the feeding ecology and the trophic position for the Lessepsian invader P. miles in the Eastern Mediterranean, based on stable isotope analysis integrated with stomach content data. Although few specimens were analyzed for stomach contents, most of the P. miles were found to feed on fish, followed by mollusks and crustaceans, as observed in [21,50]. On the contrary, the number of specimens analyzed for SIA fully adhered to the work carried out by [35]. The isotopic composition of P. miles, with a mean δ13C of −16.3‰ and a mean δ15N of 8.1‰, notwithstanding differences due to spatial variations (i.e., depth, longitude, latitude), was consistent with the isotopic values obtained for Pterois spp. in North Carolina [23] and Bermuda [51]. A natural geospatial tag potentially can be provided by stable-isotope ratios for fish migration [52] and invasion into new marine environments. Additionally, these values overlap for piscivore (−16.3‰ to −17.6‰) and opportunistic generalist fishes (−15.8‰ to −18.0‰) [53], providing additional support that lionfish are generalist predators [23].

Ontogenetic shifts in devil firefish diet were confirmed by the significant increase of δ15N vs. total length, while δ13C significantly decreased with increasing size. High site fidelity has been recorded in small Pterois spp. [54], while larger individuals are able to migrate from their shelter to surrounding habitats [55]. This could suggest that larger-sized specimens fed mainly on higher trophic level species (i.e., medium-sized fish or large crustaceans), while the smaller-sized specimens possibly prey on a lower trophic level, such as foraging fishes. Additionally, the TP of devil firefish from this study is consistent with findings from other areas (i.e., Bermuda [22,51]).

Lionfish are considered opportunistic generalist carnivores with a broad dietary niche that includes fish and invertebrates in the western Atlantic [22,56]. This can also be highlighted by similar studies using SIA, providing additional support that lionfish indeed act as a generalist predator [22,23,51,57].

Additional studies conducted in the Eastern Mediterranean have shown that in Cyprus, P. miles consume a range of teleost and crustacean prey, including S. smaris and Sparisoma cretense [58]. These are highly economically valuable fish and may be substantially impacted by the feeding habits of P. miles [58]. Moreover, observations from other areas of the Mediterranean—such as the Ionian and the southern Adriatic—indicate that local fishers frequently report declines in small coastal fish that overlap with lionfish diet preferences (authors’ unpubl. data). Although these trends may also be influenced by additional stressors (e.g., overfishing, habitat degradation, climate-driven changes), the expanding diet of P. miles suggests a potential cumulative impact on a wider suite of commercially important species, including small pelagics, juvenile sparids, and labrids. Such predation pressure could reduce the abundance of key target species at local scales, potentially altering catch composition and affecting artisanal fisheries that rely heavily on nearshore fish communities. Further research is therefore needed to quantify predation rates, assess spatial variability in impacts, and understand how lionfish expansion may interact with other anthropogenic drivers to influence regional fishery yields. This agrees with the lionfish behavior observed in the Bahamas, where a reduction of 79% towards the native fish caused by the broad diet of this invasive predator was observed [59]. In Cyprus, the main target of the species is the damselfish C. chromis, which acts as a foraging fish for the native (e.g., Thalassoma pavo and Apogon imberbis) and non-indigenous mesopredators (e.g., Parupeneus forsskali) [20,58]. Off the coast of Turkey, devil firefish prey on Mullus surmuletus, another economically important species [15]. Outside of the Mediterranean Sea, lionfish (P. miles and P. volitans) fed mainly on Gobiidae, Pomacentridae, Mullidae, Labridae, amongst other teleost families [60], while in Bermuda, both crustaceans and teleosts make a substantial contribution to the lionfish diet than elsewhere in the world [57]. The SCA described in the present work was comparable to the feeding habits observed both within their native and invaded ranges (see [21]). Indigenous fish in the Eastern Mediterranean will have to compete with the invasive P. miles for prey items, such as Gobiidae and Pomacentridae, and the dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus will have to compete with the devil firefish as both predators share the same resources [58,61].

This study reveals clear ecological patterns in the trophic behavior of the devil firefish in the Eastern Mediterranean, including an ontogenetic dietary shift that reflects changes in habitat use and predatory impact across life stages. These findings provide important insights into how this invasive predator integrates into local food webs and the potential pressures it may exert on native communities. The trophic baseline generated here offers a valuable foundation for future research aimed at assessing long-term ecological impacts and informing management strategies in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E.B. and E.F.; methodology, E.F. and K.Z.; formal analysis, E.F., E.A., and K.Z.; investigation, K.Z., G.K., M.C.-F., C.G., and E.K.; resources, G.K., M.C.-F., C.G., E.K., and E.F.; data curation, K.Z., E.A., and E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z., E.A., and E.F.; writing—review and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Chrysoula Gubili and Ioannis E. Batjakas were supported by the Operational Programme for Fisheries and Maritime 2014–2020 project “INVASION” (MIS 5049543), funded by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF). Emanuela Fanelli was supported by the Polytechnic University of Marche Research Grant 2019 through the ALIMED project (Impacts of ALIen species on MEDiterranean food webs).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Kassandra Zannaki would like to thank Andreas Sioulas, Ex-director of the Hydrobiological Station of Rhodes (HSR) of the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, for his assistance and the opportunity to work in the laboratory of HSR for her thesis. We are extremely thankful to Manolis Perrakis and the professional fishermen from Rhodes Island, who provided the devil firefish specimens that were used in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Chiantore, M.; Montefalcone, M.; Parravicini, V.; Rovere, A. Mediterranean Sea biodiversity between the legacy from the past and a future of change. In Life in the Mediterranean Sea: A Look at Habitat Changes; Stambler, N., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Lasram, F.B.R.; Aguzzi, J.; Ballesteros, E.; Bianchi, C.N.; Corbera, J.; Dailianis, T.; et al. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, M.J.; Coll, M.; Danovaro, R.; Halpin, P.; Ojaveer, H.; Miloslavich, P. A census of marine biodiversity knowledge, resources, and future challenges. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar, J.L.; Gamboa, R.L.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M.D. Assessing the global threat of invasive species to marine biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2008, 6, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Ben Rais Lasram, F.; Zenetos, A.; Cardoso, A.C. Invading the Mediterranean Sea: Biodiversity patterns shaped by human activities. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 1, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golani, D.; Sonin, O. New records of the Red Sea fishes, Pterois miles (Scorpaenidae) and Pteragogus pelycus (Labridae) from the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Jpn. J. Ichthyol. 1992, 39, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzurro, E.; Stancanelli, B.; Di Martino, V.; Bariche, M. Range expansion of the common lionfish Pterois miles (Bennett, 1828) in the Mediterranean Sea: An unwanted new guest for Italian waters. Bioinvasions Rec. 2017, 6, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariche, M.; Torres, M.; Azzurro, E. The presence of the invasive Lionfish Pterois miles in the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2013, 14, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetta, F.; Agius, D.; Balistreri, P.; Bariche, M.; Bayhan, Y.K.; Çakir, M.; Ciriaco, S.; Corsini-Foka, M.; Deidun, A.; El Zrelli, R.; et al. New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (October 2015). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2015, 16, 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailianis, T.; Akyol, O.; Babali, N.; Bariche, M.; Crocetta, F.; Gerovasileiou, V.; Chanem, R.; Gökoğlu, M.; Hasiotis, T.; Izquierdo-Muñoz, A.; et al. New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (July 2016). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2016, 17, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, C.; Galanidi, M.; Zenetos, A.; Corsini-Foka, M.; Giovos, I.; Karachle, P.K.; Fournari-Konstantinidoy, I.; Kytinou, E.; Issaris, Y.; Azzurro, E.; et al. Updating the occurrences of Pterois miles in the Mediterranean Sea, with considerations on thermal boundaries and future range expansion. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2020, 21, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletou, D.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Kleitou, P. A lionfish (Pterois miles) invasion has begun in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 2016, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Corsini-Foka, M.; Crocetta, F.; Gerovasileiou, V.; Karachle, P.; Simboura, N.; Tsiamis, K.; Pancucci-Papadopoulou, M.A. Deep cleaning of alien and cryptogenic species records in the Greek Seas (2018 update). Manag. Biol. Invasions 2018, 9, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, A.C.; Chartosia, N.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Kleitou, P.; Jimenez, C.; Antoniou, C.; Hadjioannou, L.; Kletou, D.; Sfenthourakis, S. Genetic Data Suggest Multiple Introductions of the Lionfish (Pterois miles) into the Mediterranean Sea. Diversity 2019, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, E.Ö.; Mavruk, S.; Saygu, İ.; Öztürk, B. Lionfish distribution in the eastern Mediterranean coast of Turkey. J. Black Sea/Medit. Environ. 2017, 23, 1–16. Available online: https://blackmeditjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/1.231-2017-EOzgurOzbek.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Stern, N.; Jimenez, C.; Huseyinoglu, M.F.; Andreou, V.; Hadjioannou, L.; Petrou, A.; Öztürk, B.; Golani, D.; Rothman, S.B. Constructing the genetic population demography of the invasive lionfish Pterois miles in the Levant Basin, Eastern Mediterranean. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2019, 30, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzurro, E.; Bariche, M. Local knowledge and awareness on the incipient lionfish invasion in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2017, 68, 1950–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kleitou, P.; Savva, I.; Kletou, D.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Antoniou, C.; Christodoulides, Y.; Chartosia, N.; Hadjioannou, L.; Dimitriou, A.C.; Jimenez, C.; et al. Invasive lionfish in the Mediterranean: Low public awareness yet high stakeholder concerns. Mar. Policy 2019, 104, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amen, M.; Azzurro, E. Lessepsian fish invasion in Mediterranean marine protected areas: A risk assessment under climate change scenarios. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2020, 77, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, D.; Jimenez, C.; Reader, T.; Hadjioannou, L.; Heyworth, S. Behavioural traits and feeding ecology of Mediterranean lionfish and native species naiveté to lionfish predation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2020, 638, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannaki, K.; Corsini-Foka, M.; Kampouris, T.E.; Batjakas, I.E. First results on the diet of the invasive Pterois miles (Actinopterygii: Scorpaeniformes: Scorpaenidae) in the Hellenic waters. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 2019, 49, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.; Bogdanoff, A.K.; Layman, C.A.; Castillo, B.; Reale-Munroe, K.; Chapman, J.; Dahl, K.; Patterson, W.F., III; Eddy, C.; Ellis, R.D.; et al. Feeding ecology of invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans and Pterois miles) in the temperate and tropical western Atlantic. Biol. Invasions 2018, 20, 2567–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.C.; Currin, C.A.; Whitfield, P.E. Diet of invasive lionfish on hard bottom reefs of the Southeast USA: Insights from stomach contents and stable isotopes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 432, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, P.A.; Bustos-Montes, D.; Pabón, P.; Polo-Silva, C.J.; Muñoz, A.S. Feeding Habits of Pterois volitans: A Real Threat to Caribbean Coral Reef Biodiversity. In Impacts of Invasive Species on Coastal Environments. Coastal Research Library; Makowski, C., Finkl, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 29, pp. 269–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, C.A.; Allgeier, J.E. Characterizing trophic ecology of generalist consumers: A case study of the invasive lionfish in the Bahamas. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 448, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell, S.; Bearhop, S.; McGill, R.A.R.; Dahlgren, C.P.; Brumbaugh, D.R.; Mumby, P.J. Habitat and body size effects on the isotopic niche space of invasive lionfish and endangered Nassau grouper. Ecosphere 2014, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocheret de la Morinière, E.; Pollux, B.J.A.; Nagelkerken, I.; Hemminga, M.A.; Huiskes, A.H.L.; van der Velde, G. Ontogenetic dietary changes of coral reef fishes in the mangrove-seagrass-reef continuum: Stable isotopes and gut-content analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003, 246, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearhop, S.; Thompson, D.R.; Waldron, S.; Russell, I.C.; Alexander, G.; Furness, R.W. Stable isotopes indicate the extent of freshwater feeding by cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo shot at inland fisheries in England. J. Appl. Ecol. 1999, 36, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyslop, E.J. Stomach contents analysis—A review of methods and their application. J. Fish Biol. 1980, 17, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucherousset, J.; Bouletreau, S.; Martino, A.; Roussel, J.M.; Santoul, F. Using stable isotope analyses to determine the ecological effects of non-native fishes. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2012, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, R.J.; Chimimba, C.T.; Zengeya, T.A. Niche complementarity between an alien predator and native omnivorous fish in the Wilge River, South Africa. Hydrobiologia 2018, 817, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 2002, 83, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M.; Pace, M.L.; Hairston, N.G. Ecosystem size determines food-chain length in lakes. Nature 2000, 405, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Zanden, M.J.; Casselman, J.M.; Rasmussen, J.B. Stable isotope evidence for the food web consequences of species invasions in lakes. Nature 1999, 401, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, E.; Azzurro, E.; Bariche, M.; Cartes, J.E.; Maynou, F. Depicting the novel Eastern Mediterranean food web: A stable isotopes study following Lessepsian fish invasion. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 2163–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, G.W.; Fry, B.; O’Brien, W.J. Stable isotopes and planktonic trophic structure in arctic lakes. Ecology 1992, 73, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallien, L.; Carboni, M. The community ecology of invasive species: Where are we and what’s next? Ecography 2017, 40, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, E.T. Pterois volitans and Pterois miles: Two valid species. Copeia 1986, 1986, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagwade, P.V. The food and feeding habits of the Indian oil sardine Sardinella longiceps Valenciennes. Indian J. Fish. 1964, 11, 345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hureau, J.C. Biologie comparée de quelques poissons antarctiques (Nototheniidae). Bull. Inst. Oceanogr. Monaco 1970, 68, 244. [Google Scholar]

- Euzen, O. Food habits and diet composition of some fish of Kuwait. Kuwait Bull. Mar. Sci. 1987, 9, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, W.; Bauchot, M.L.; Schneider, M. Fiches FAO D’identification des Espèces Pour les Besoins de la Pêche (Révision 1); Méditerranée et mer Noire. Zone de pêche 37. vol. 2 (Vertébrés); FAO: Rome, Italy, 1987; Volume 2, 769p. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, K.E. (Ed.) The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Atlantic; FAO Species Guide for Fishery Purposes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; Volume 2, 773p. [Google Scholar]

- Lombarte, A.; Chic, Ò.; Parisi-Baradad, V.; Olivella, R.; Piera, J.; García-Ladona, E. A web-based environment for shape analysis of fish otoliths. The AFORO database. Sci. Mar. 2006, 70, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Romegialli, C.; Jackson, A.L.; Hayden, B.; Kahilainen, K.K.; Lopes, C.; Harrod, C. tRophicPosition, an r package for the Bayesian estimation of trophic position from consumer stable isotope ratios. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 1592–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchan, J.H.; Lewis, W.M., Jr.; Kendall, C.; McGrath, C.C. Variation in trophic shift for stable isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. Oikos 2003, 102, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compson, Z.G.; Monk, W.A.; Hayden, B.; Bush, A.; O’Malley, Z.; Hajibabaei, M.; Porter, T.M.; Wright, M.T.; Baker, C.J.; Al Manir, M.S.; et al. Network-Based Biomonitoring: Exploring Freshwater Food Webs with Stable Isotope Analysis and DNA Metabarcoding. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Mazumder, D.; Suthers, I.M.; Taylor, M.D. To fit or not to fit: Evaluating stable isotope mixing models using simulated mixing polygons. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, A.C.; Inger, R. Stable Isotope Mixing Models in R with SIMMR: A Stable Isotope Mixing Model. (Version 0.4.1). SIMMR. 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/simmr/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Skarvelis, K.; Mouriki, D.; Lazarakis, G.; Peristeraki, P. Preliminary analysis results of lionfish (Pterois miles/volitans) stomach contents on the coasts of Crete. In Proceedings of the 17th Ichthyologists Symposium, Herakleion, Greece, 31 October–3 November 2019; HCMR: Crete, Greece, 2019; pp. 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, C.; Pitt, J.M.; Larkum, J.; Altabet, M.A.; Bernal, D. Stable Isotope Ecology of Invasive Lionfish (Pterois volitans and P. miles) in Bermuda. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 7, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueman, C.N.; MacKenzie, K.M.; Palmer, M.R. Identifying migrations in marine fishes through stable-isotope analysis. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 81, 826–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, B. Food web structure on Georges Bank from stable C, N, and S isotopic compositions. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1988, 33, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jud, Z.R.; Layman, C.A. Site fidelity and movement patterns of invasive lionfish, Pterois spp., in a Florida estuary. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2012, 414–415, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkwitt, C.E. Invasive lionfish increase activity and foraging movements at greater local densities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2016, 558, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, I.M.; Maljković, A. Predation rates of Indo-Pacific lionfish on Bahamian coral reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 404, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, C.; Pitt, J.; Morris, J.A., Jr.; Smith, S.; Goodbody-Gringley, G.; Bernal, D. Diet of invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans and P. miles) in Bermuda. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2016, 558, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, I.; Chartosia, N.; Antoniou, C.; Kleitou, P.; Georgiou, A.; Stern, N.; Hadjioannou, L.; Jimenez, C.; Andreou, V.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; et al. They are here to stay: The biology and ecology of lionfish (Pterois miles) in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albins, M.A.; Hixon, M.A. Invasive Indo-Pacific lionfish Pterois volitans reduce recruitment of Atlantic coral-reef fishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 367, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, D.C.; Monteagudo, P.C.; Schmitter-Soto, J.J.; Wong, R.I.C.; Torres, H.S.; Sansón, E.C.; Rodríguez, A.G.; Osorio, A.F.; Pantoja, L.E.; Guerra, D.C.; et al. Density, size, biomass, and diet of lionfish in Guanahacabibes National Park, Western Cuba. Aquat Biol 2016, 24, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.; Mittermayer, F.; Pihl, L.; Wennhage, H. Feeding ecology of indigenous and non-indigenous fish species within the family Sphyraenidae. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 80, 2528–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).