The Effect of ‘Roughness’ on Upwelling North of Cape Town in Austral Summer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Analysis

3. Results

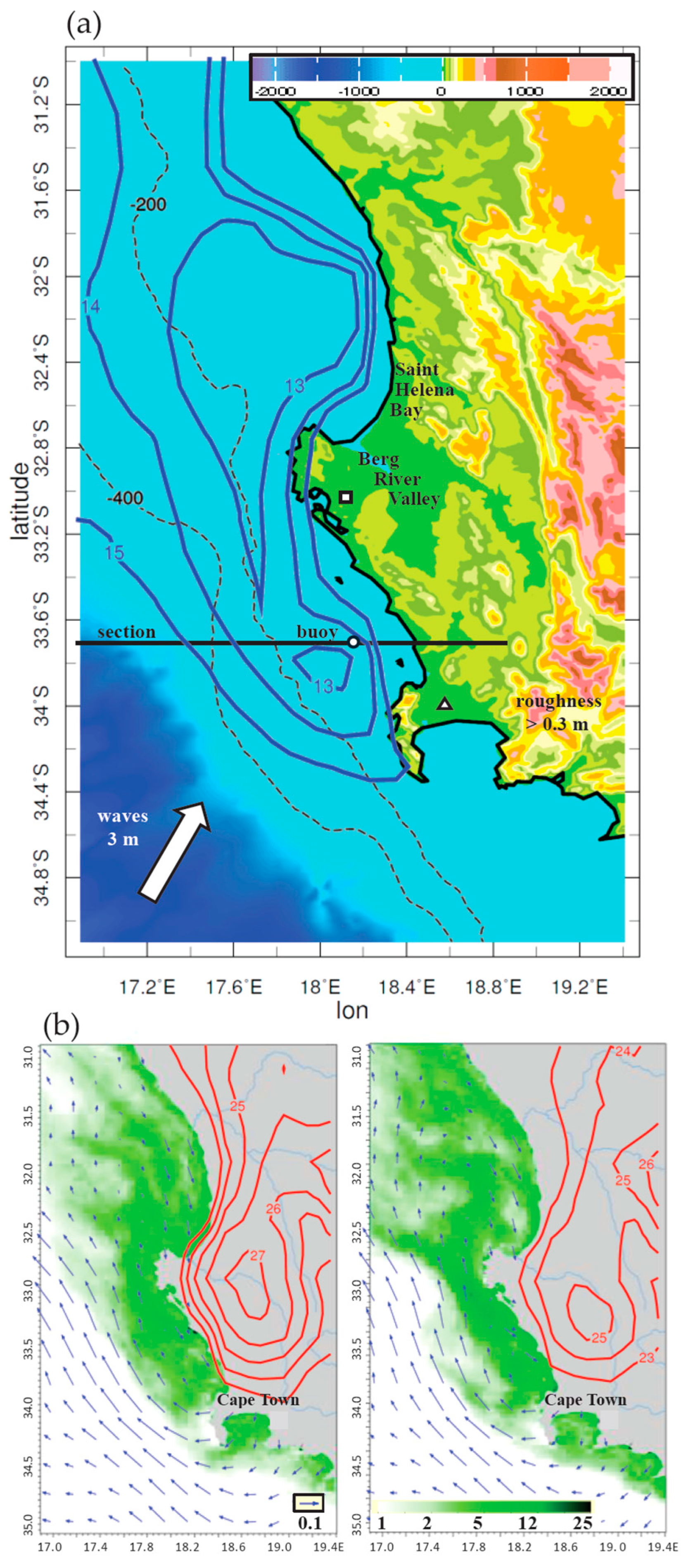

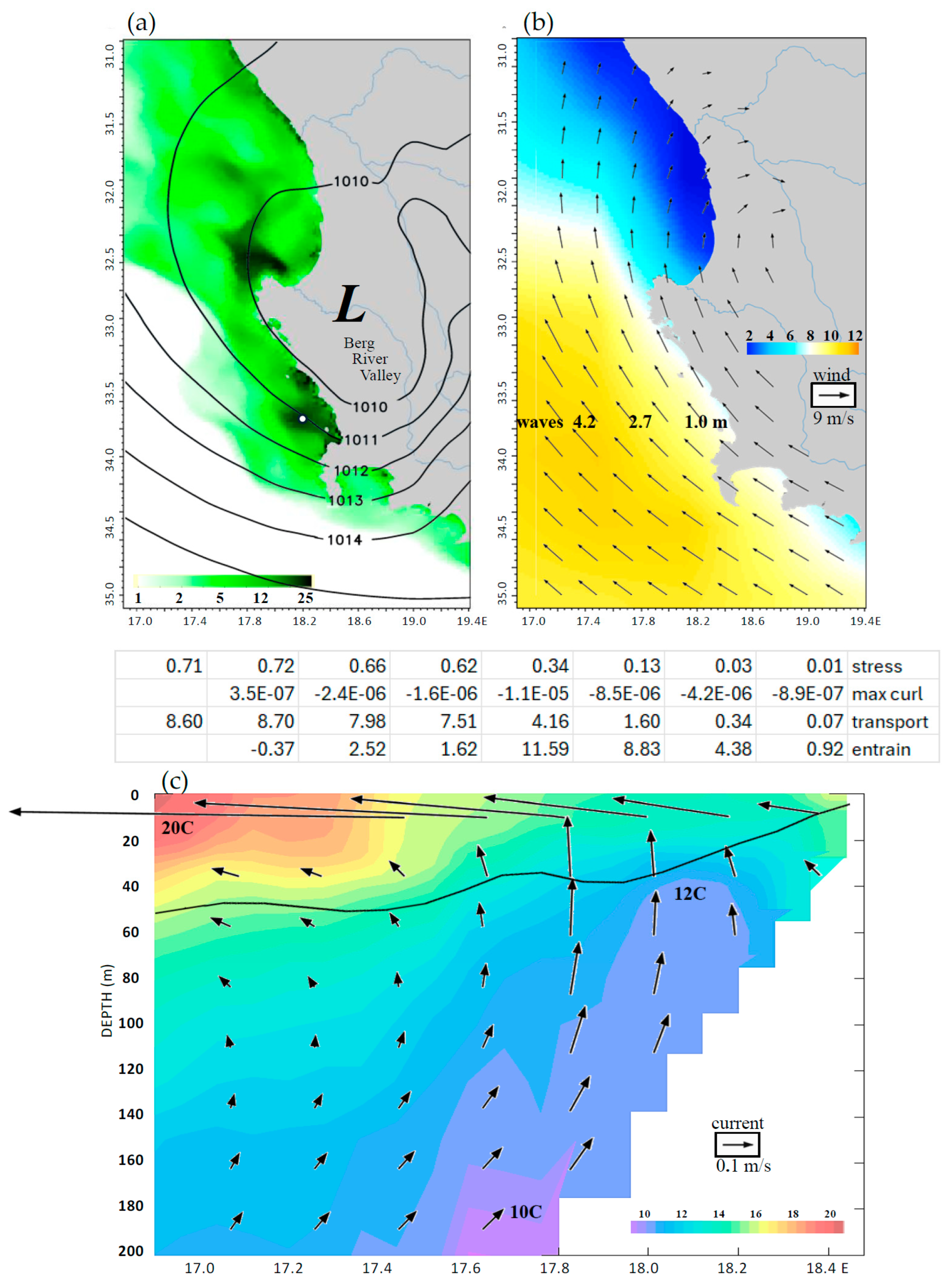

3.1. Summer Averages

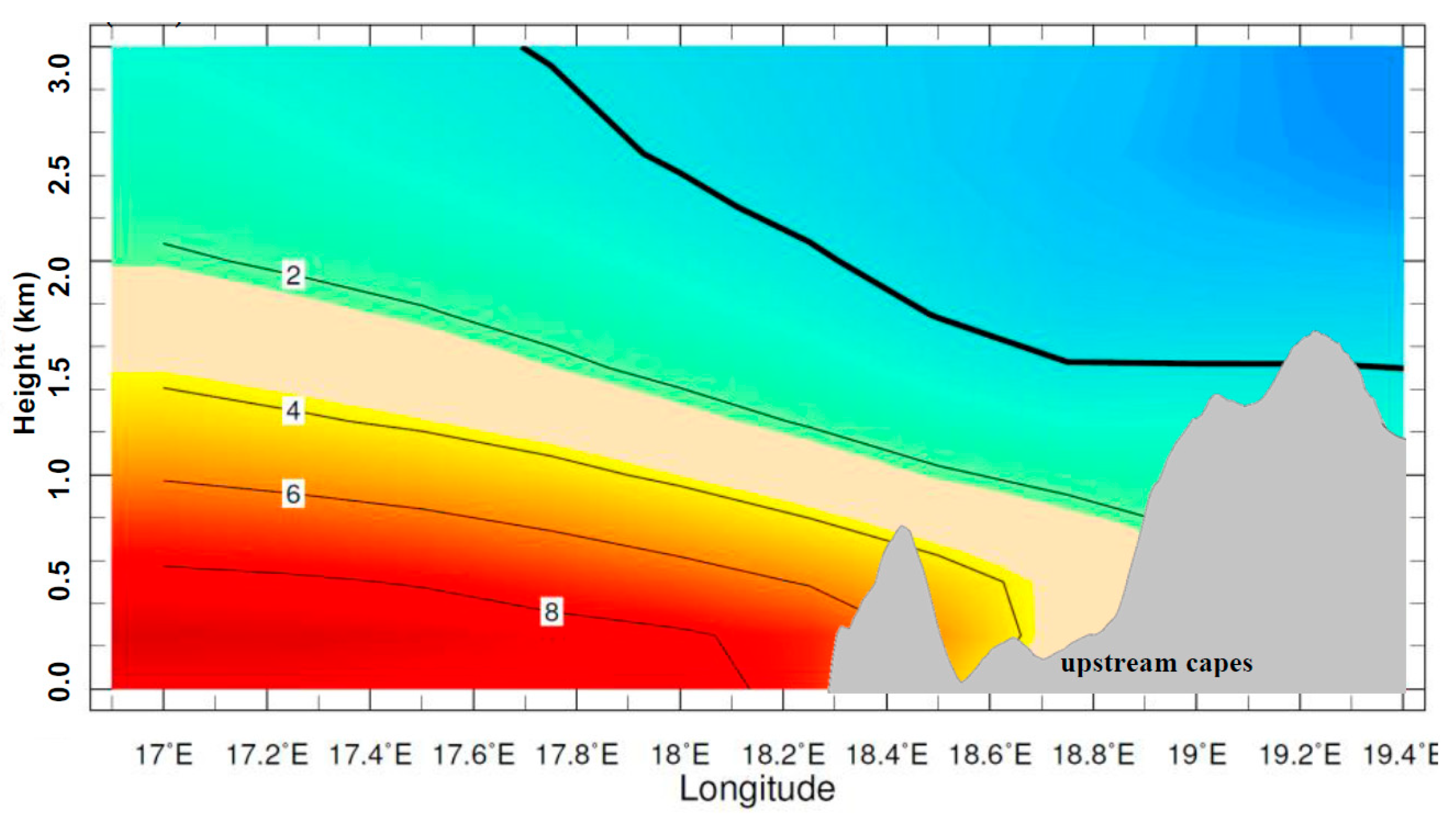

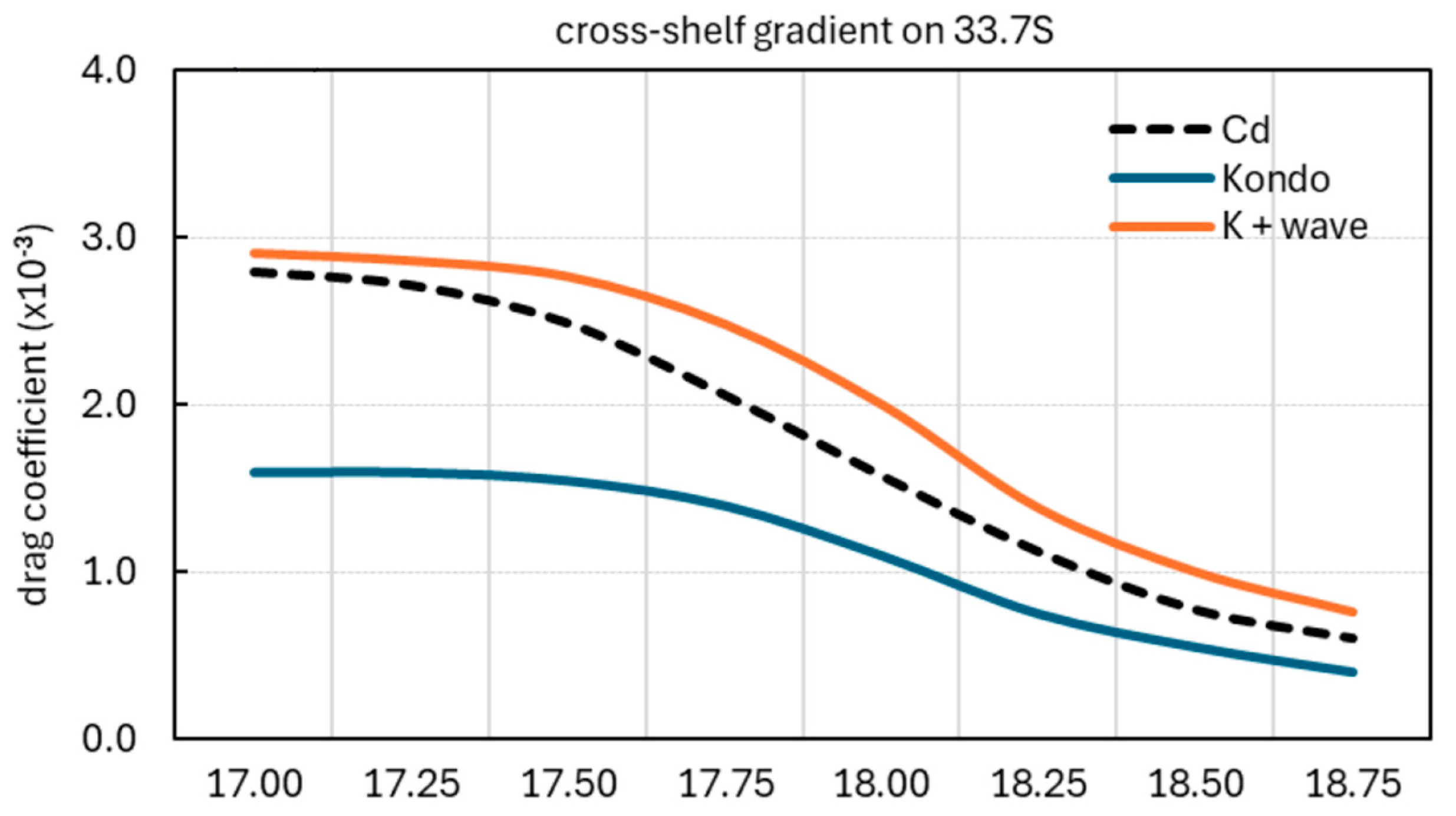

3.2. Cross-Shore Gradients

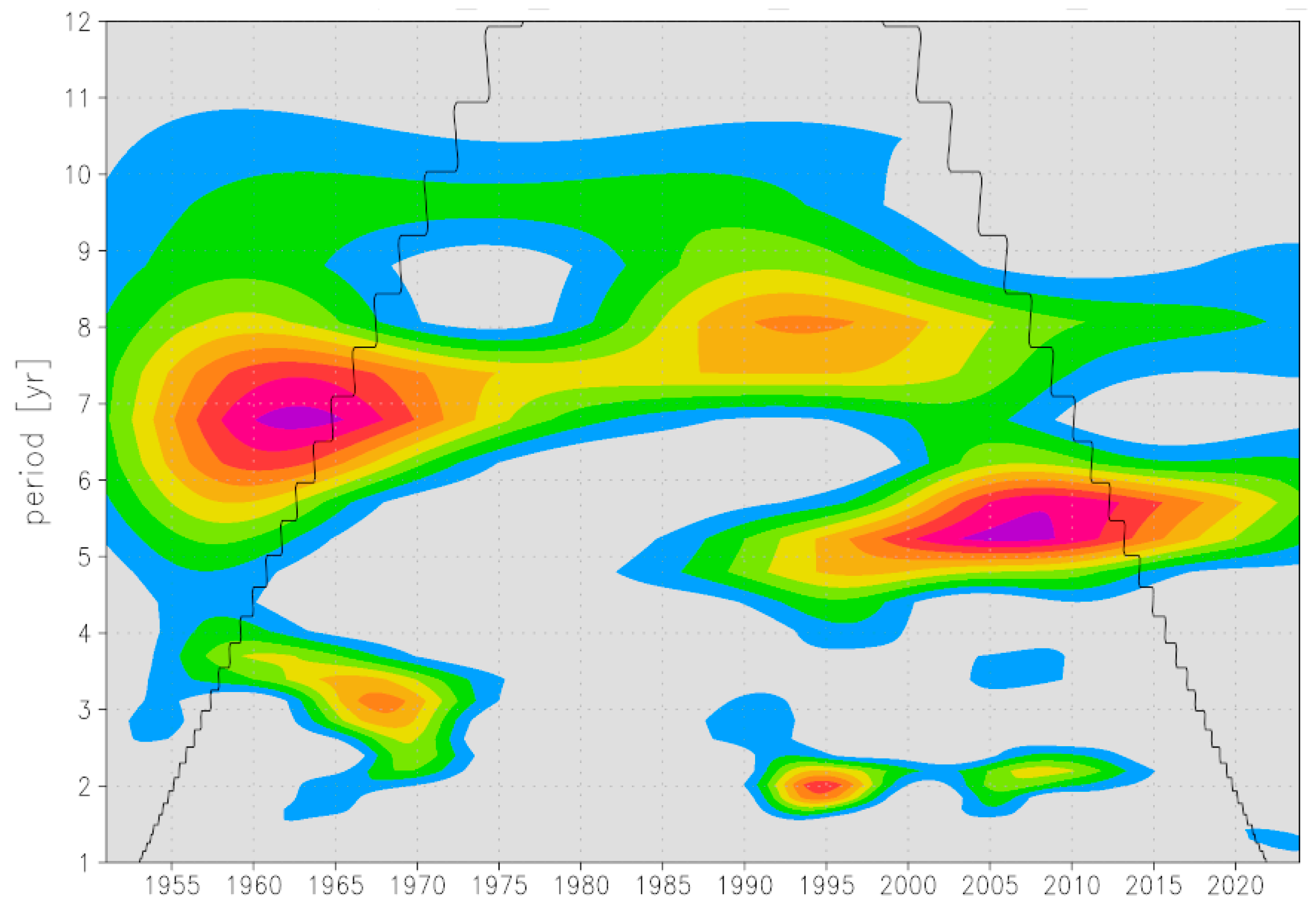

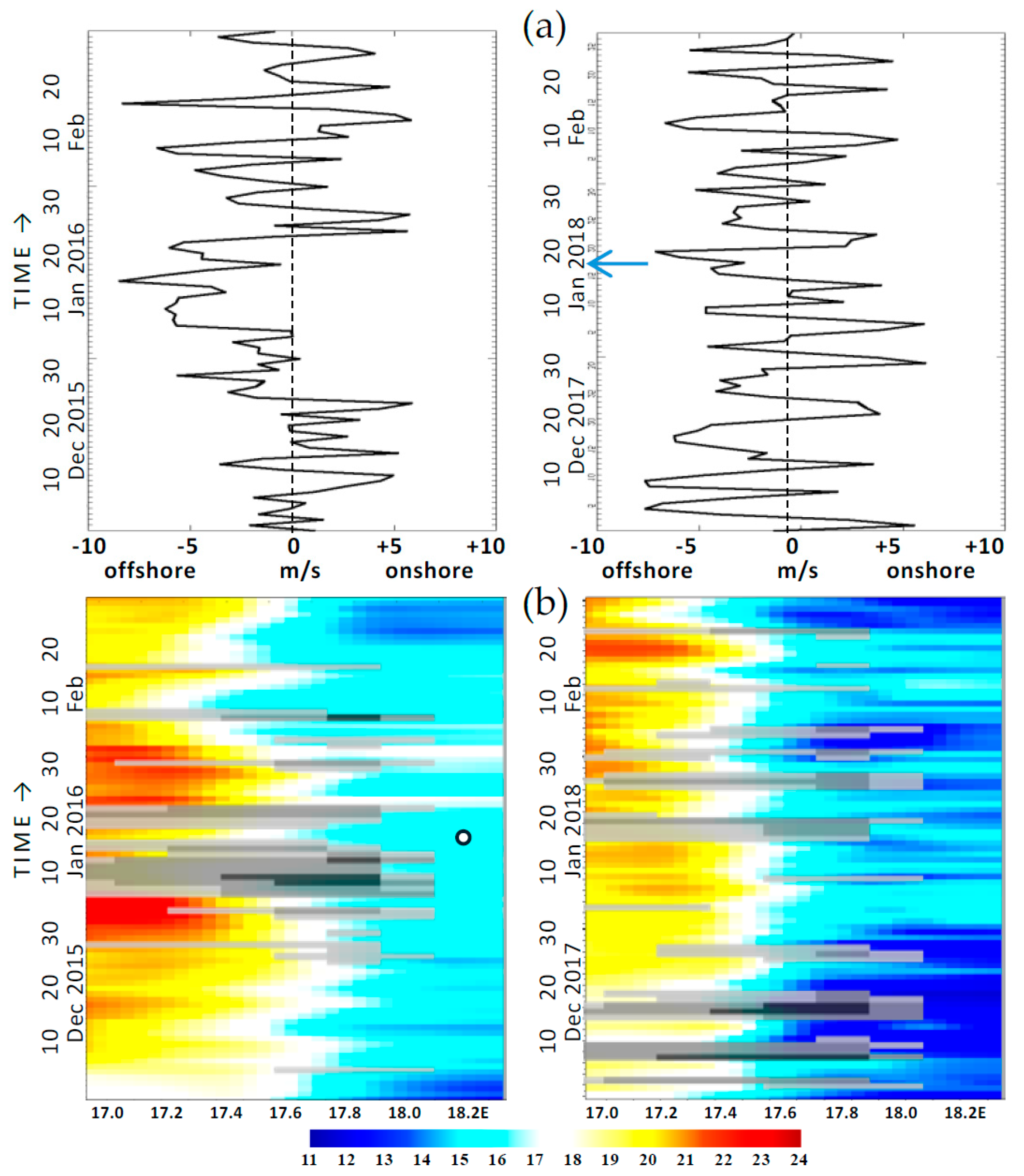

3.3. Temporal Characteristics

3.4. Case Study of January 2018

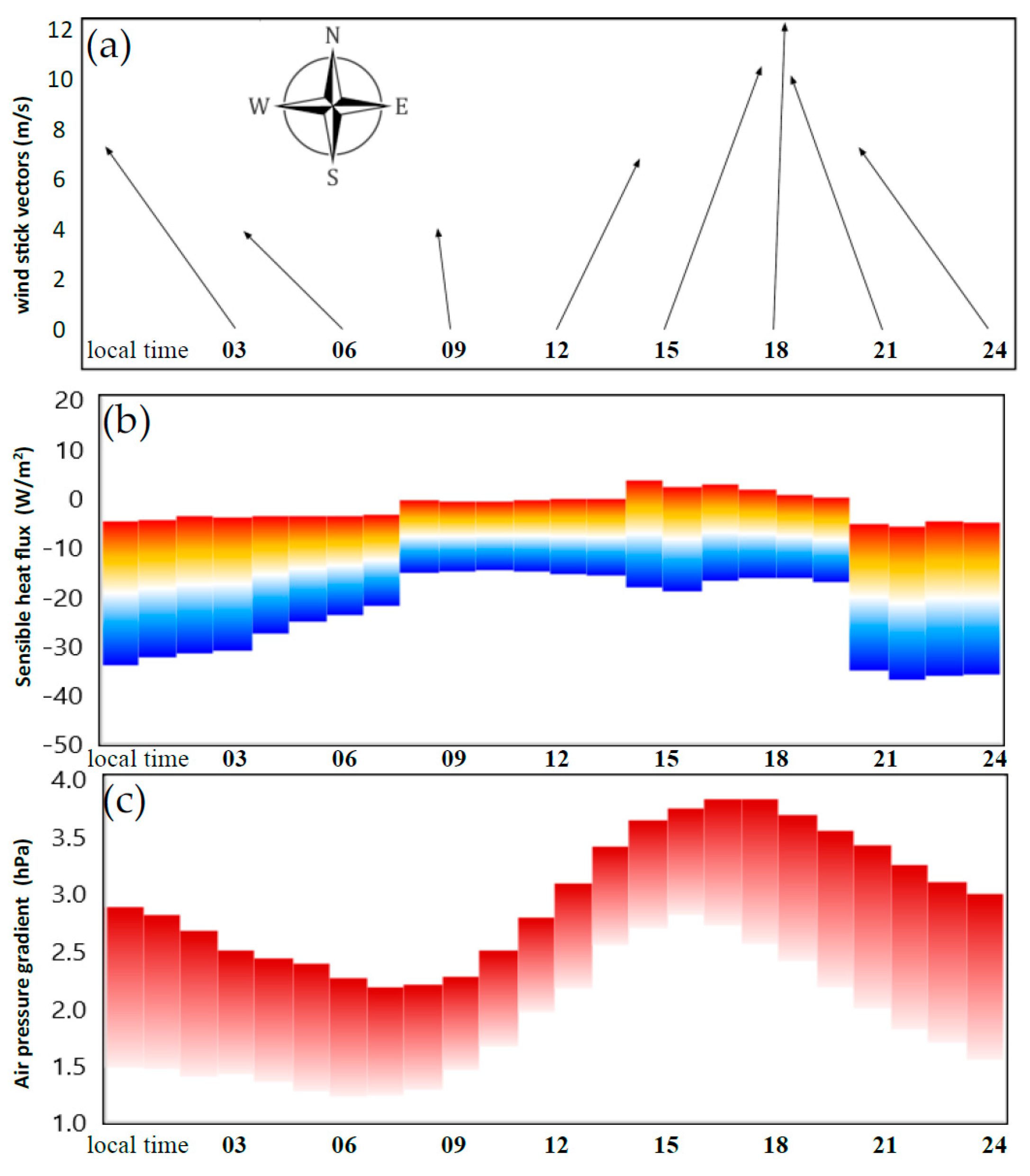

3.5. Variability and Diurnal Cycle

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Jury, M.R. The spatial distribution of wind driven upwelling off the west coast of Africa, 29–34S. Cont. Shelf Res. 1988, 8, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, L.V.; Nelson, G. The Benguela: Large scale features and processes and system variability. In The South Atlantic: Present and Past Circulation; Wefer, G., Berger, W.H., Siedler, G., Webb, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 163–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberth, R.; Nelson, G. Field and analytical drogue studies applicable to the St Helena Bay area off South Africa’s west coast. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 1987, 5, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jury, M.R.; MacArthur, C.; Reason, C. Observations of trapped waves in the atmosphere and ocean along the coast of southern Africa. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 1990, 72, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S.E. A low-level jet along the Benguela coast, an integral part of the Benguela current ecosystem. Clim. Change 2010, 99, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Penven, P.; Shillington, F.A. Modeling equilibrium dynamics of the Benguela Current system. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2010, 40, 1942–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jury, M.R. Representation of coastal upwelling in the southern Benguela by satellite era reanalysis. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2013, 3, 267–277. [Google Scholar]

- Small, R.J.; Curchitser, E.; Hedstrom, K.; Kauffman, B.; Large, W.G. The Benguela upwelling system: Quantifying the sensitivity to resolution and coastal wind representation in a global climate model. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 9409–9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.C. Spatial and seasonal variation in chlorophyll distribution in the upper 30 m of the photic zone in the southern Benguela/Agulhas ecosystem. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 1992, 12, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, G.C.; Brown, P.C.; Mitchell-Innes, B.B. Spatio-temporal variability of phytoplankton in the southern Benguela upwelling system. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 1992, 12, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, M.J.; Hutchings, L. Zooplankton diversity and community structure around southern Africa, with special attention to the Benguela upwelling system. S. Afr. J. Sci. 1996, 92, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, L.V.; Lutjeharms, J.R.E.; Nelson, G. Causative mechanisms for intra-annual and interannual variability in the marine environment around southern Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 1990, 86, 356–373. [Google Scholar]

- Jury, M.R.; Courtney, S. A transition in weather over the Agulhas Current. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 1991, 10, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Rautenbach, C.; Hermes, J.; Reason, C. The Cape Point wave record, extreme events and the role of large-scale modes of climate variability. J. Mar. Syst. 2019, 198, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar, M.H.; Mohrholz, V.; Schmidt, M. The relation of wind-driven coastal and offshore upwelling in the Benguela upwelling system. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2021, 51, 3117–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, C.J.; Jury, M.R. On the generation and propagation of the southern African coastal low. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1990, 496, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jury, M.R.; Brundrit, G.B. Temporal organization of upwelling in the southern Benguela ecosystem by resonant coastal trapped waves in the ocean and atmosphere. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 1992, 12, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.E.; Hickey, B.M.; Shillington, F.A.; Strub, P.T.; Brink, K.H.; Barton, E.D.; Thomas, A.C. Eastern ocean boundaries. In The Sea, The Global Coastal Ocean, Regional Studies and Syntheses; Robinson, A.R., Brink, K.H., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 11, pp. 29–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shillington, F.A.; Reason, C.; Duncombe-Rae, C.M.; Florenchie, P.; Penven, P. Large scale physical variability of the Benguela Current large marine ecosystem. Large Mar. Ecosyst. 2006, 14, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Demarcq, H. Trends in primary production, sea surface temperature and wind in upwelling systems (1998–2007). Prog. Oceanogr. 2009, 83, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freon, P.; Barange, M.; Arıstegui, J. Eastern boundary upwelling ecosystems: Integrative and comparative approaches, an introduction. Prog. Oceanogr. 2009, 83, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jury, M.R. Wind vorticity and upwelling on the coast of South Africa. Coasts 2024, 4, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, J.R. Review of drag coefficients over oceans and continents. Mon. Weather Rev. 1977, 105, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edson, J.B.; Jampana, V.; Weller, R.A.; Bigorre, S.P.; Plueddemann, A.J.; Fairall, C.W.; Miller, S.D.; Mahrt, L.; Vickers, D.; Hersbach, H. On the exchange of momentum over the open ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2013, 43, 1589–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, W.; Wang, D.; Wu, Z.; Chen, D. Effects of swell waves on atmospheric boundary layer turbulence and surface wind stress. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2019, 124, 6516–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, D.; Mahrt, L.; Andreas, E.L. Formulation of the sea surface friction velocity in terms of the mean wind and bulk stability. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2015, 54, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, J. Air-sea bulk transfer coefficients in diabatic conditions. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 1975, 9, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, J. Comparison of Kondo’s bulk transfer coefficient with recently made direct observations of fluxes on the sea surface. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 1977, 55, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, N. Modification of Kondo’s formulas on bulk transfer coefficients of turbulent fluxes over the ocean. Geophys. J. Jpn. 1981, 28, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, A.B.; Wallcraft, A.J.; Metzger, E.J.; Hurlburt, H.E.; Fairall, C.W. Wind stress drag coefficient over the global ocean. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 5856–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.B.; Hurlburt, H.E.; Murtugudde, R. A comparison of models for coastal wind stress and its impact on upwelling. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2007, 37, 1065–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Chassignet, E.P.; Hurlburt, H.E.; Metzger, E.J.; Smedstad, O.M.; Cummings, J.A.; Halliwell, G.R.; Bleck, R.; Baraille, R.; Wallcraft, A.J.; Lozano, C.; et al. Global ocean prediction with the Hybrid coordinate ocean model (Hycom). Oceanography 2009, 22, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Long, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hamouda, M.A.; Mohamed, M.M. A global daily gap-filled chlorophyll-a dataset in open oceans 2001–2021 from multi-source information using convolutional neural networks. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 5281–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, H.L.; Banner, M.L.; Kaihatu, J.M. The NOAA operational wave model improvement project. Ocean. Model. 2013, 70, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Zhao, D.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.A.; Huang, J. Observation-based parameterization of air-sea fluxes in terms of wind speed and atmospheric stability under low-to-moderate wind conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2017, 122, 4123–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, S.J.; Barlow, R.; Roy, C.; Shillington, F.A. Remotely sensed variability of temperature and chlorophyll in the southern Benguela: Upwelling frequency and phytoplankton response. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2006, 28, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, L.V.; Pillar, S.C. The Benguela Ecosystem, Part 3: Plankton. In Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review; Barnes, M., Ed.; Aberdeen University Press: Aberdeen, UK, 1986; Volume 24, pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Rykaczewski, R.R.; Checkley, D.M. Influence of ocean winds on the pelagic ecosystem in upwelling regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1965–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennel, K.; Neuman, M. Physical and biological drivers of coastal upwelling: Dynamics and implications for productivity. Deep.-Sea Res. II 2016, 122, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.S.; Newberger, P.A.; Beardsley, R.C. Seasonal variability of upwelling off the coast of South Africa and its effect on chlorophyll and primary productivity. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2006, 111, C12006. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, R.T.; Pohlmann, T.; Heywood, K.J. Atmospheric forcing and upwelling dynamics in the Benguela Current system: A review. Prog. Oceanogr. 2012, 103, 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G.; Samelson, R.M. Summertime coupling between sea surface temperature and wind stress in the California Current system. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2007, 37, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonino, G.; Iovino, D.; Brodeau, L.; Masina, S. The bulk parameterizations of turbulent air–sea fluxes in NEMO4: The origin of sea surface temperature differences in a global model study. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 6873–6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelao, R.M. Sea surface temperature and wind stress curl variability near a Cape. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2012, 42, 2073–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jury, M.R. The Effect of ‘Roughness’ on Upwelling North of Cape Town in Austral Summer. Oceans 2025, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040083

Jury MR. The Effect of ‘Roughness’ on Upwelling North of Cape Town in Austral Summer. Oceans. 2025; 6(4):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040083

Chicago/Turabian StyleJury, Mark R. 2025. "The Effect of ‘Roughness’ on Upwelling North of Cape Town in Austral Summer" Oceans 6, no. 4: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040083

APA StyleJury, M. R. (2025). The Effect of ‘Roughness’ on Upwelling North of Cape Town in Austral Summer. Oceans, 6(4), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040083