Abstract

Background: Despite advances in myoelectric control of hand prostheses, their dropout rate remains high. Methods: We analyzed 37 features extracted from surface electromyography (sEMG) recordings from 15 participants, distributed into three groups: non-impaired individuals, impaired individuals with limb loss due to trauma, and impaired individuals with limb loss due to electrical burn. Feature relationships were examined with correlation heatmaps and two feature-selection methods (ReliefF and Minimal Redundancy Maximum Relevance), and classification performance was evaluated using machine-learning models to characterize sEMG behavior across groups. Results: Individuals with electrical-burn injury exhibited increased forearm co-contraction on the affected side across normalized isometric contractions, indicating altered motor coordination and likely higher energetic cost for prosthetic control. Feature selection and model results revealed etiology-dependent differences in the most informative sEMG features, underscoring the need for personalized, etiology-aware myoelectric control strategies. Conclusions: These findings inform the design of adaptive prosthetic controllers and targeted rehabilitation protocols that account for injury-specific motor control adaptations.

1. Introduction

Amputation is the loss of a limb, which involves the loss of both motor and sensory functions and directly affects people’s ability to perform their work, social life, and even their Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), such as eating or dressing [1,2,3]. It is estimated that each year, there is an approximate increase of 150,000 to 200,000 people who suffer from an amputation in the world, of which 30% correspond to amputations of the upper limb [4].

Transradial amputation arises from diverse causes, including vascular disease, trauma, cancer, and electrical burns. Electrical burns are an important and distinct cause of upper-limb amputation because current preferentially traverses low-resistance tissues (nerves, vessels, muscles), producing severe structural and physiological damage that can alter residual muscle architecture, innervation, and limb size [3,5,6].

People who suffer from an upper limb transradial amputation rely on the use of hand prosthetics since, in many cases, they improve their ability to perform ADLs [7]. One of the most advanced solutions in research and development today is the myoelectric prosthesis, which translates residual muscle activity into intuitive device control.

Key to these myoelectric systems is surface electromyography (sEMG), a non-invasive method for assessing and studying the electrical activity of skeletal muscles using electrodes placed on the skin’s surface [1,6]. Its clinical and research capabilities were significantly enhanced following the SENIAM project in the late 1990s, which established standardized protocols for electrode placement and signal processing [8]. Currently, sEMG serves as the foundation for real-time biofeedback in physiotherapy and rehabilitation [9], assesses pelvic-floor functionality to inform treatments for urinary incontinence [10], evaluates the coordination of masticatory and temporomandibular muscles in dentistry and orthodontics [11], and, as mentioned afore, when used with human–machine interface algorithms, sEMG can be used to decipher user intention in prosthetics or assistive robotics [12].

Most current clinical myoelectric systems, particularly in real-life prosthesis fittings, use a relatively simple dual-site configuration, typically placing electrodes over available wrist flexor and extensor muscles to capture opposing activation patterns for binary control (hand open/close). However, some authors, such as Leone et al. [13], noted that myoelectric prostheses with a dual-site configuration are unnatural to control and unintuitive due to the use of an agonist-antagonist muscle pair, such as flexion–extension of the wrist, and are therefore abandoned.

Research efforts have pushed the other end of the spectrum toward multi-channel or high-density sEMG to increase spatial and information content for pattern recognition and proportional control.

Some researchers, such as Daley et al. [14], compared high-density sEMG data for different hand and wrist movements, specifically for the classification of normally limbed and people with transradial amputation for multifunction prosthetic control. It was determined that high-rate classification (85–98%) was achieved over 13 movements for healthy participants. In contrast, only four movements were classified in people with amputation.

In 2019, Campbell et al. [15], using the data analysis method based on the Mapper topology, compared the time and frequency features of the sEMG signals of healthy and people with amputation, where it was observed that the informative content of the sEMG features of people with amputation differed from those of non-people with amputation in three aspects: (1) the loss of nonlinear complexity and frequency information, (2) the loss of time series modeling information, and (3) the segmentation of unique information. Other findings from Campbell et al. indicate that the performance of people with amputation was proportional to residual limb size, suggesting that an anthropomorphic model could be beneficial.

However, despite efforts to advance myoelectric control of hand prostheses, Sturma et al. [6] point out that myoelectric prosthetic hands exhibit a high dropout rate of around 52.18%, which remains substantial, suggesting a mismatch between laboratory-optimized systems and the heterogeneity of patient physiology and needs.

Although few efforts have been made to integrate databases [16] and research [15,17,18] that consider people with transradial amputation patients, most of these studies focus on traumatic etiology, followed by cancer etiology, but none are due to electrical burns to the author’s knowledge. As Campbell et al. [15] and Chuan [18] emphasize, sEMG signals vary significantly across people with amputation populations. In electrical-burn survivors, this variability may be even more pronounced due to the extent and nature of tissue damage—potentially affecting key features such as residual limb size, time-series dynamics, and frequency-domain features, which may be significantly disrupted, and are considered essential for reliable pattern recognition. It is also worth mentioning that previous research in sEMG-based analysis has significantly advanced our understanding of muscle coordination and its relevance. For instance, the Co-Contraction Index (CCI) serves as a quantitative measure of the concurrent activation of agonist and antagonist muscles, proving invaluable in uncovering altered neuromuscular strategies. A recent study conducted by Bandini et al. [19] illustrated that Frost’s CCI effectively monitored enhancements in upper limb function during post-stroke rehabilitation, thereby establishing a clinically viable outcome measure.

On that account, some questions arise for the authors: Do people with amputation due to electrical burns exhibit different characteristics compared to those who have amputation due to trauma (accident)? If so, could myoelectric prostheses that rely on sensing two muscle pairs be affected? This article hypothesizes that individuals with transradial amputations resulting from electrical burns exhibit distinct sEMG features when compared to those with traumatic etiologies, which may significantly influence the control performance and functional efficacy of the myoelectric prosthetic devices.

Hence, to answer the hypothesis, we have used the CCI, a feature that expresses the simultaneous contraction between agonist and antagonist muscles [3,13,20]. To observe changes in sEMG features, along with the CCI, 18 other sEMG features from the time, frequency, and time-frequency domains used for pattern recognition were calculated across 15 test participants, divided into three groups: non-impaired participants and impaired participants who underwent a transradial amputation due to trauma or an electrical burn. The changes, as mentioned earlier, were observed using feature selection methodologies such as ReliefF and Minimal Redundancy Maximum Relevance (MRMR). ReliefF, which is based on a nearest-neighbor estimator, ranks features according to their capacity to differentiate between similar instances across distinct classes. Meanwhile, MRMR selects features that maintain maximal relevance to the target variable while exhibiting minimal redundancy among themselves [21].

This study provides systematic evidence that people with transradial amputation from electrical burns can differ from people with transradial amputation from trauma in sEMG signal quality and patterning, and shows that the CCI is a robust, interpretable marker that improves group discrimination and enhances classifier performance

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We studied 15 participants, split into three groups of five: the first group consisted of non-impaired participants. Impaired participants formed the second group due to traumatic transradial amputation. And finally, the third group was formed by Impaired participants due to electrical-burn transradial amputation. The limited availability of individuals with electrical burn amputations influenced the sample size. Torres and Herrán (2014) [22] conducted a review of electronic medical records for patients with electrical burns at a referral hospital in Mexico City, which has over 600 inpatient beds. Their findings revealed that only eight out of 21 patients treated for electrical burns at the Centro Médico Nacional “20 de Noviembre” between 2009 and 2013 were amputated. Similar limitations in participant availability have been documented in other studies targeting the people with amputation population [23,24,25]. Despite the modest size of this study, it provides a first insight into a rarely represented group.

We recruited the participants for this study based on the following criteria: age 18 years or older and able to give informed consent; for those in the people with amputation groups, there should be a transradial amputation resulting from traumatic or electrical burns, with adequate residual limb functionality to conduct isometric wrist and elbow contractions; for the non-impaired group, participants must have no history of limb loss or any neuromuscular or orthopedic issues impacting the upper limbs, regardless of gender. The participants were informed of the study’s objectives, risks, and benefits both verbally and in writing. Informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, was obtained. The proposed research was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute of Rehabilitation with approval number INR02/18 AC. All data are available in the repository at https://github.com/canibulin/sEMGAmputeeTraumaElectricalBurn (accessed on 12 August 2025), ensuring participant anonymity and adherence to ethical research standards.

2.2. Clinical Assessment

We collected clinical evaluation data from impaired participants in groups 2 (trauma-related causes) and 3 (caused by electrical burns). Through a focused physical examination of the upper limbs, we examined the laterality, shape, consistency, and length of the residual limb. We recorded measurements of arm length, forearm dimensions, the thickness of the soft-tissue cushion, and the biceps perimeter at rest and during muscle contraction. We also evaluated muscle strength using the Medical Research Council scale [26], focusing on wrist flexor muscles (flexor radialis, carpal extensor, carpal ulnar flexor, and palmaris longus) and wrist extensors (radial carpal extensor longus and short, and ulnar carpal extensor), as available. Furthermore, we assessed the strength of the biceps and triceps brachii muscles to gain a thorough insight into upper limb functionality in our participants.

2.3. sEMG Electrode Positioning

Before placing the electrodes, the area of skin to be measured was prepared by gently shaving the region and subsequently cleaning it with 70% isopropyl alcohol to remove skin impurities. Then, disposable Ag-AgCl electrodes (10 mm in diameter, sensing area) with conductive hydrogel and adhesive electrodes were placed on the wrist flexor and extensor muscles, or on the biceps and triceps brachii muscles, depending on the experiment to be conducted. All surface electrodes (of the first group of healthy participants) were placed following the recommendations of the SENIAM project (Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles) [27,28]. However, in the case of people with amputation, the conventional SENIAM electrode placement guidelines proved impractical due to the inherent anatomical changes, specifically, the limited residual limb length and structural alterations following amputation. Electrode placement for participants with amputation was performed by a single experienced clinician using auscultation to locate the muscle belly. While the participant produced wrist flexion/extension-like contractions of the residual limb, the clinician palpated for the highest muscular prominence. All trials for each participant were collected in a single session, with electrodes left in place for the entire session and not repositioned between contractions. No ultrasound or imaging was used for mapping.

2.4. Data Acquisition

We acquired sEMG signals using a Shimmer 3 (Shimmer, Dublin, Ireland) sEMG sensor. The Shimmer 3 sensor was chosen because of its high DC input impedance (>100 MΩ), which minimizes skin–electrode loading and preserves both low- and high-frequency signal fidelity [29,30]. The sEMG signals were acquired at a sampling rate of 512 Hz, as per [29,30], which considers a sampling frequency of 512 Hz acceptable for acquiring sEMG signals, thereby avoiding data loss when simultaneously acquiring two-channel sEMG signals in real-time via Bluetooth streaming. To remove motion artifacts and baseline drift, a fourth-order Butterworth-type high-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 5 Hz (), was applied to the raw and processed sEMG signals [31]. Additionally, no notch filter was used, as the Shimmer 3 is battery-powered, and no interference was observed during acquisition. The acquisition and preprocessing methodology followed the recommendations outlined in the Shimmer3 sEMG User Guide (published by Shimmer Sensing), which provides practical guidance on the recommended acquisition setup [32].

Wrist and elbow flexion–extension movement trials performed by the participants were collected. For non-impaired participants, movements consisted of active wrist/hand flexion–extension or elbow flexion–extension. Impaired participants with transradial amputation performed voluntary isometric contractions of the residual limb, attempting to reproduce the targeted wrist/hand movement. This mixed protocol yielded repeatable, labelable windows of graded agonist–antagonist activation that map directly onto the common myoelectric open/close control dimension used in dual-site and pattern-recognition evaluations [15,20,21].

To assess maximum muscle strength, the sEMG signal envelope from each trial was first computed and normalized to its peak value during a maximal voluntary contraction. Once normalized, a 5-s square reference signal was generated as a calibration benchmark. This procedure allowed subsequent contractions to be expressed as a percentage of the participant’s maximal activation. In our protocol, each participant then performed at least five muscle contractions at 80%, 60%, 40%, and 20% of the maximum value [33], resulting in at least 1 min of continuous sEMG data recording.

This stepwise assessment not only accommodates inter-participant variability but also provides a detailed profile of muscle activation across different intensity levels.

2.5. Signal Processing and Data Analysis

We obtained the sEMG signal envelope by rectifying the sEMG raw signal and calculating the Root Mean Square (RMS) value, as defined in Equation (1). This was applied over 150 ms squared windows.

First, we labeled all the sEMG collected data using Python Label Studio (version 1.21.0, Python package) [34], indicating the normalized isometric contraction sections at 80%, 60%, 40%, and 20% of the testing participants’ maximum voluntary contraction. Then, after data labeling was completed, we created 300 ms with 50% overlapping squared window segments from which we calculated over 18 sEMG signal features, including time, frequency, and time-frequency domain features. The selected features were calculated based on various literature pattern recognition articles [35,36,37,38]. The calculated features from the time domain were: RMS (1), Variance of sEMG (VAR) (2), Integrated sEMG (IEMG) (3), Mean Absolute Value (MAV) (4), Log Detector (LOG) (5), Waveform Length (WL) (6), Average Amplitude Change (AAC) (7), Difference absolute standard deviation value (DASDV) (8), Zero-Crossing (ZC) (9), Willison amplitude (WAMP) (11), and, Myopulse percentage rate (MYOP) (13). The frequency domain sEMG signals features calculated were: Frequency Ratio(FR) (15), Mean Frequency (MNF) (16), Median frequency (MDF) (17), and Peak Frequency (PKF) (18).

where sgn(.), is the sign function (10)

where is defined in (12)

where is defined in (14)

where is the sEMG signal in a segment. is the total length of the sEMG signal. is the power spectrum at a frequency . Finally, is the spectrum frequency at frequency . n and j are the and respectively.

The selected CCI, which is also used as an sEMG feature, is expressed in [20] and defined in Equation (19).

where t1 and t2 represent the instants of the beginning and end of the signals entering the Equation, being important that both signals possess the same length (both and , respectively). On the other hand, identifies the minimum value between both sEMG signals, corresponding to the muscle’s activation level working as an antagonist.

Once all the sEMG features described above were calculated, we created two matrices corresponding to the Elbow flexion–extension and Wrist Flexion–Extension Muscles. Each created matrix included all the features calculated from the two sEMG channels recorded, making 37 features in each matrix for all the tested participants. Additionally, each data matrix was accompanied by labels indicating the normalized force contraction levels, movement, and the group to which each data point belonged.

After creating the data matrices, we generated correlation heatmaps for each force-level segment of the sEMG signals to analyze relationships and pattern clusters among the sEMG features. Then, we continued performing two feature reduction analyses to see the relevance of sEMG features, considering the proposed groups (healthy participants or people with amputation due to trauma or electrical burn). The first chosen algorithm was MRMR, a feature selection technique that selects a subset of features that are minimally redundant with one another and highly relevant to the target variable. The MRMR algorithm has selected the most valuable and informative feature set for hand gesture detection based on EMG [39]. The second feature-reduction analysis was performed using the ReliefF algorithm. This feature weighting algorithm assigns higher weights to all features that are highly correlated with the target category, which is the proposed group. We ran the proposed feature reduction analysis in MATLAB 2024.

Finally, we conducted three experiments using machine learning algorithms to evaluate the classification results based on the previous analysis. The selected machine learning-trained models were SVM (Fine Gaussian Kernel), KNN (Cosine KNN kernel), and Ensemble (Bagged trees kernel). The three distinct tests we conducted aimed to evaluate the impact of the CCI index and feature reduction techniques on classifier performance.

Each classifier was trained to predict the participant group (three classes: non-impaired participants, impaired participants by amputation due to trauma, and impaired participants due to electrical burn). The present study does not map features to device commands (open-, close-, neutral); that mapping is proposed as future work.

The first test consisted of running the machine learning algorithm considering all features except CCI. The Second test consisted of running all features, including the CCI. The third test consisted of running a reduced set of features selected based on a prior test of feature relevance. The primary aim of the first two tests was to determine whether including the CCI index improved the classifiers’ accuracy. On the other hand, the third test was designed to assess whether accuracy could be maintained with a reduced feature set, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of the feature reduction process.

To evaluate the classification performance, confidence intervals, and effect sizes of the proposed and evaluated models, we employed a repeated k-fold cross-validation procedure in MATLAB [40]. As [40] notes, we used a 5-fold cross-validation, repeating the entire process 10 times to capture variability arising from random data splits. During each repetition and fold, we partitioned the data into training and testing sets. We accumulated the balanced accuracy scores across all repetitions and folds. Finally, we computed a 95% confidence interval for each classifier’s balanced accuracy, beginning with the calculation of mean accuracy and its standard error from the distribution of accuracy scores. The confidence interval was then derived using Equation (20):

where:

CI (Confidence Interval): The range that likely contains the true mean classification accuracy with 95% confidence.

Mean: The average accuracy across all cross-validation folds and repetitions.

1.96: The z-score is associated with a 95% confidence level under a normal distribution.

SE (Standard Error): The standard deviation of the accuracy scores divided by the square root of the number of observations; it reflects the uncertainty of the mean.

We evaluated classifier performance using balanced accuracy (defined in Equations (21) and (22)) as the primary feature. Balanced accuracy was computed per fold as the average of per-class recall (sensitivity) and then aggregated across folds and repeats; this choice prevents dominant classes from disproportionately inflating performance on our imbalanced dataset. Model evaluation used repeated stratified k-fold cross-validation with 5 folds and 10 repeats to preserve class proportions in each fold and to capture variability from random splits. A fixed random seed (rng(1)) was used for partitioning to ensure reproducibility of the reported results. Stratified folds were created with MATLAB’s cvpartition, and balanced accuracy for each test fold was computed as the mean recall across classes present in that fold; we report the mean balanced accuracy across all folds and repeats with 95% confidence intervals calculated from the distribution of per-fold balanced accuracies (mean ± 1.96·SE).

where:

C: number of classes (here 3: healthy, trauma, electrical burn).

: true positives for class c (samples of class c correctly predicted).

: false negatives for class c (samples of class c predicted as another class).

: sensitivity for class c.

We have used balanced accuracy, which averages per-class recall to prevent high nominal accuracy from being driven by dominant classes. It is appropriate for imbalanced multiclass datasets and gives equal weight to each class’s detection performance.

This methodology facilitated a systematic comparison of classifier performance under varied conditions while ensuring statistical reliability through repeated cross-validation and comprehensive confidence interval estimations.

Finally, to compare differences in sEMG features across stump etiologies, we used MATLAB to perform group-wise statistical analysis of key sEMG features, including the CCI and features from the time, frequency, and time-frequency domains. Each feature was tested for normality using the Lilliefors test and for homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test. When both assumptions were met (p > 0.05), a one-way ANOVA was applied; otherwise, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Features showing significant group effects (p < 0.05) underwent post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Tukey–Kramer (for ANOVA) or Dunn–Sidak (for Kruskal–Wallis) to identify specific inter-group differences.

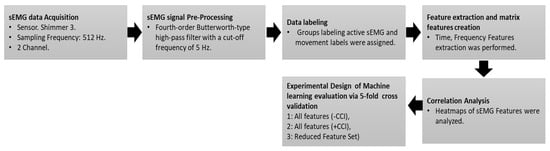

The sEMG signal processing and classification performance code is available at https://github.com/canibulin/sEMGAmputeeTraumaElectricalBurn (accessed on 12 August 2025). Figure 1 illustrates a diagram summarizing the methodology.

Figure 1.

Summary of Methodology workflow: sEMG data acquisition and preprocessing, data labeling, feature extraction (including CCI), correlation analysis, and machine learning evaluation (SVM, KNN, Ensemble) via repeated k-fold cross-validation.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Data and Clinical Assessment Data Description

The first group, the control group, consisted of 2 women and 3 men aged 27 to 58 years; all participants had no limb loss.

The 10 transradial participants with impaired function were divided into two groups based on the amputation’s etiology. The first group of impaired participants consisted of 1 woman and 4 men, whose amputations were secondary to electrical burns. Their ages ranged from 18 to 67 years (mean ± SD: 39.4 ± 16.39 years). Four patients had a right stump, and three had left stumps. The stumps were all cylindrical, with 3 being flaccid and 2 firm. The stump length ranged from 7 to 14 cm (mean ± SD: 10.43 ± 2.57 cm), and the amputation evolution time ranged from 1 to 13 years (mean ± SD: 5.03 ± 5.09 years). Only 2 patients were former users of mechanical prostheses, with usage times ranging from 4 to 13 h per day (mean ± SD: 8.5 ± 4.5 h). The second impaired group was formed by 2 women and 3 men, whose amputations were secondary to trauma. The patient’s age ranged from 26 to 64 years (mean ± SD: 44 ± 14.59 years). Four right stumps and one left stump were evaluated. Three of the stumps had a cylindrical shape, and two had a conical shape. Four stumps were of flaccid consistency, while one was firm. The stump lengths ranged from 7.5 to 14.5 cm (11.8 ± 3.33 cm), and the amputation evolution time ranged from 1 to 7 years (2.40 ± 2.21 years). Four patients had previous experience with mechanical prostheses, using them for 3 to 12 h daily (8.75 ± 3.54 h). Table 1 shows the clinical evaluation data for these participants.

Table 1.

Participants data obtained from the clinical assessment.

All participants were assessed for wrist and elbow flexion and extension muscle strength using Daniels and Worthingham’s Muscle Grading Scale [41], with Group 1 graded 5. Groups 2 and 3 between 3 and 4, meaning they could complete a full range of motion against gravity and hold the end position against mild resistance and strong resistance without breaking the test position.

3.2. Data Analysis

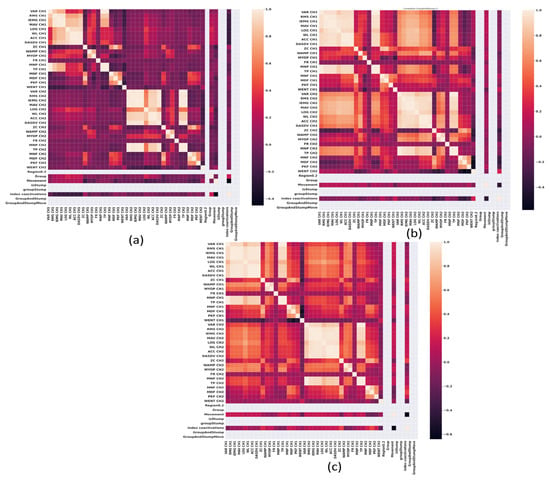

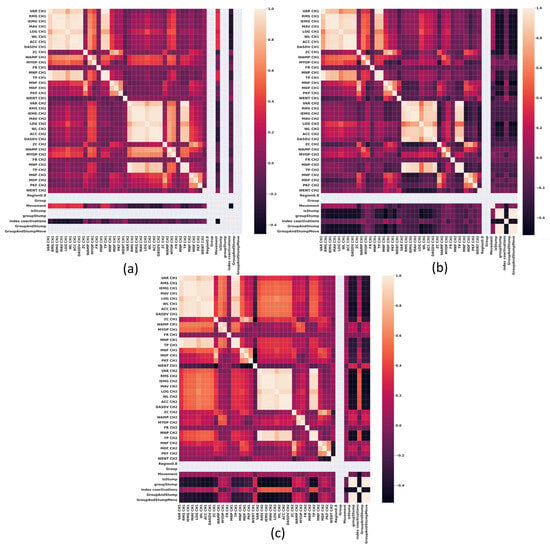

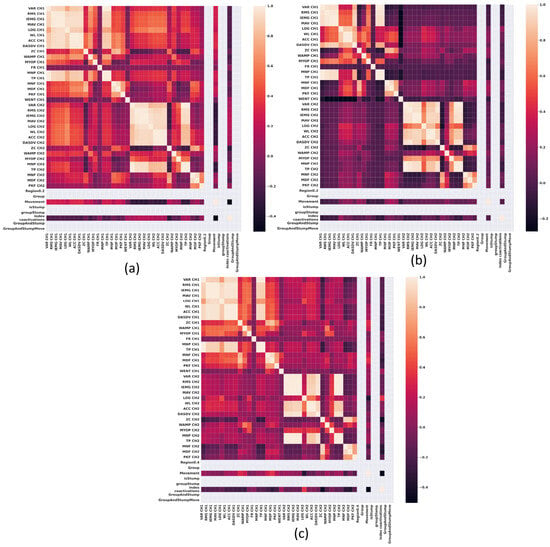

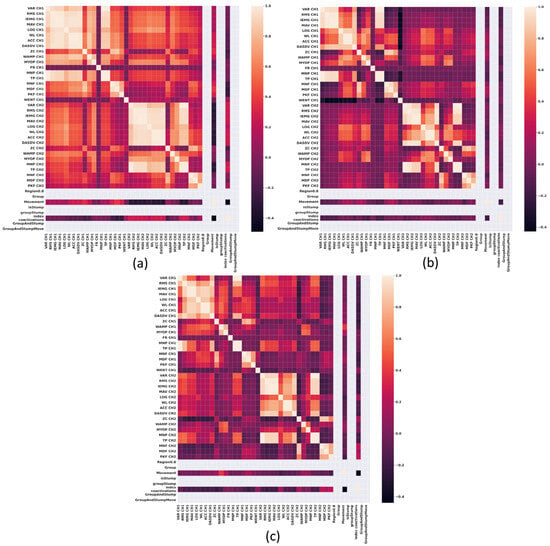

In Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, the correlation heat maps obtained from the sEMG signal extracted features of the wrist flexor-extensor and elbow muscle groups are presented. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the correlation between the sEMG signal features of the wrist flexor and extensor muscles at 20% and 80% of maximal normalized contraction, respectively. Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the correlation between the sEMG signal features of the elbow flexor and extensor muscles at 20% and 80%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Correlation heat maps obtained from the features of sEMG signals of the wrist Flexor-Extensor muscles at 20% of a normalized maximum contraction. (a) Group 1, non-impaired participants, (b) impaired participants due to trauma, and (c) impaired participants due to electrical burn.

Figure 3.

Correlation heat maps obtained from the features of sEMG signals of the wrist Flexor-Extensor muscles at 80% of a normalized maximum contraction. (a) Group 1, non-impaired participants, (b) impaired participants due to trauma, and (c) impaired participants due to electrical burn.

Figure 4.

Correlation heat maps obtained from the features of sEMG signals of the elbow Flexor-Extensor muscles at 20% of a normalized maximum contraction. (a) Group 1, non-impaired participants, (b) impaired participants due to trauma, and (c) impaired participants due to electrical burn.

Figure 5.

Correlation heat maps obtained from the features of sEMG signals of the elbow Flexor-Extensor muscles at 80% of a normalized maximum contraction. (a) Group 1, non-impaired participants, (b) impaired participants due to trauma, and (c) impaired participants due to electrical burn.

Since the behaviors of the sEMG features are better contrasted at the levels shown, the correlation maps of sEMG signals at 40% and 60% of normalized maximal contraction were omitted.

The participant group’s data was clustered. Then, as can be appreciated in Figure 2, and it is repeated in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, where: (a) Group 1, non-impaired participants, (b) impaired participants due to trauma, and (c) impaired participants due to electrical burn. It can be observed that in the upper-left and lower-right central regions, two high-correlation clusters correspond to correlations within the same sEMG signal features, as expected in a correlation map. In Figure 2b,c, corresponding to the impaired participant groups, there are clusters with high correlation in the lower left and, symmetrically, in the upper right. These clusters, which can be visualized, relate flexor muscle variables to extensor muscle variables, indicating co-contraction between antagonistic muscle groups.

It is worth noting that this specific cluster is not present in the group of non-impaired participants shown in Figure 2a. The comparison between the cluster behavior observed in Figure 2a,c, and that in Figure 3a,c, is maintained, but in Figure 3b, the cluster indicating co-contraction is absent. From these observations, it can be concluded that in the impaired participant group due to electrical burn, the remaining wrist muscles require co-contraction from their muscle groups, even at low contraction levels, compared with normalized maximal contraction. In this case, the visible difference between the impaired group due to trauma and the impaired group due to amputation from electrical burns is that in the latter, the co-contraction phenomenon persists at high levels. This is particularly counterproductive when using a myoelectric prosthesis, as prolonged co-contraction can cause users to lose control, leading to greater energy expenditure.

Figure 4 illustrates a heat map of correlations among sEMG features at 20% of normalized maximal contraction in the flexor and extensor muscles at the elbow. A significant cluster of strong correlations exists among antagonistic muscle groups in the non-impaired participants group (Figure 4a). In contrast, this type of clustering is absent in impaired groups (Figure 4b,c).

By examining Figure 4 and Figure 5, we can see that in non-impaired participants (Figure 4a and Figure 5a), the bond between antagonistic muscle groups grows stronger. However, in the trauma-related impaired group (Figure 5b), while correlations between features exist, they remain weak and less defined compared to those seen at the wrist. On the other hand, Figure 5c, depicting the impaired group due to electrical burn injuries, shows a moderate correlation between opposing muscle groups.

These results suggest that the co-contraction observed in the elbow muscles of the non-impaired group may be due to the need to support the weight of the forearm, thereby requiring muscular co-contraction during greater force exertion. On the other hand, the impaired group due to trauma, who are missing part of the forearm, may exhibit improved control of the muscle group that remains. In the case of the impaired group due to electrical burn, a moderate correlation indicating co-contraction was observed, which could be attributed to tissue damage, and is a hypothesis that requires further exploration.

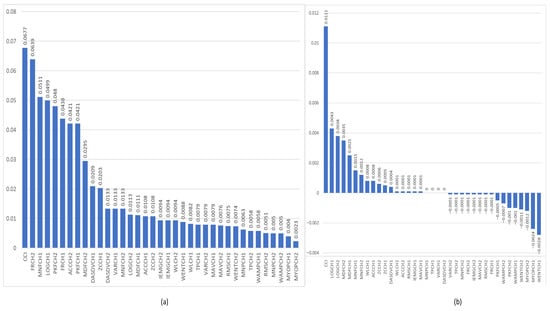

Figure 6a,b present the feature relevance rankings obtained from the MRMR and ReliefF algorithms, applied to sEMG signals recorded from wrist muscles. In both cases, the Co-Contraction Index (CCI) emerged as the most discriminative feature across the studied groups, followed by a mix of time-domain and frequency-domain features. Notably, several of these high-ranking features exhibit strong inter-feature correlations, as previously illustrated in the correlation heatmaps (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), and reflect combined activity from both flexor and extensor muscle groups.

Figure 6.

Graphs show the relevance of the features of the sEMG signals corresponding to the flexion–extension muscles of the wrist to identify the group of non-impaired participants and impaired participants. (a) shows the feature relevance obtained by the MRMR algorithm, and (b) shows the feature relevance obtained by the ReliefF algorithm.

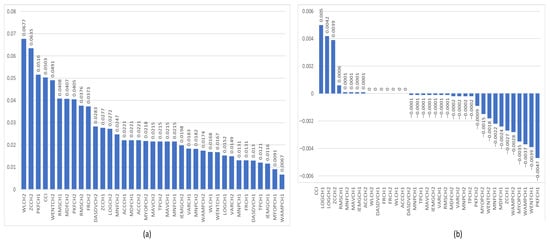

Figure 7a,b show the feature relevance results obtained using the MRMR and ReliefF algorithms for sEMG signals from the elbow muscles. In this case, we can observe that, in the context of the MRMR algorithm, the CCI is no longer the most important sEMG feature; instead, the sEMG WL feature takes precedence. However, the CCI remains the most relevant feature of the ReliefF algorithm.

Figure 7.

Graphs show the relevance of sEMG signal features from the flexion–extension muscles of the elbow for distinguishing between non-impaired and impaired participants. (a) shows the feature relevance obtained by the MRMR algorithm, and (b) shows the feature relevance obtained by the ReliefF algorithm.

Table 2 shows the balanced accuracy results from the three experiments designed to assess the contribution of the correlation coefficient in identifying non-impaired participants, participants with trauma-induced impairment, or participants with electrical burn. The first experiment, or Run 1, tested 36 features of the sEMG signals. The second experiment, Run 2, involves classifying 37 sEMG features, including the proposed CCI metric. Finally, the third experiment, or Run 3, corresponded to testing a set of reduced characteristics obtained from the sEMG signal features relevance algorithms. The reduced feature set consisted of 11 sEMG features: LOGCH1; ACCCH1; FRCH1; PKFCH1; LOGCH2; FRCH2; MNFCH2; MDFCH2; PKFCH2; CCI; ACCCH2.

Table 2.

Window-wise balanced accuracy (mean [%]) and 95% confidence interval for wrist flexor–extensor classification across three experimental runs (Run 1: all features except CCI; Run 2: all features including CCI; Run 3: reduced 11-feature set). Each cell shows mean balanced accuracy [%] [95% CI lower, 95% CI upper]. The 11-feature set (Run 3) contains: LOGCH1; ACCCH1; FRCH1; PKFCH1; LOGCH2; FRCH2; MNFCH2; MDFCH2; PKFCH2; CCI; ACCCH2.

The results in Table 2, which present classification across the three experimental runs on wrist flexor–extensor windows, show consistent trends across classifiers. In Run 1 (all features except CCI), the Ensemble (Bagged trees) achieved 85.40% mean balanced accuracy [85.29, 85.52], outperforming SVM (Fine Gaussian) at 79.64% [79.52, 79.75] and KNN (Cosine) at 39.40% [39.32, 39.49]. In Run 2 (all features including CCI), all classifiers improved: Ensemble reached 89.39% [89.28, 89.50], SVM 84.54% [84.44, 84.64], and KNN 40.94% [40.85, 41.04], indicating that adding CCI increased discriminative power across models. In Run 3 (reduced 11-feature set), performance decreased for all classifiers relative to Run 2, with Ensemble at 81.60% [81.50, 81.69], SVM 75.31% [75.17, 75.44], and KNN 43.04% [42.95, 43.13], showing that aggressive feature reduction altered the feature space and reduced peak accuracy. These results confirm the importance of CCI for improving window-wise discrimination and indicate that the Ensemble classifier is the most robust to feature configuration in our wrist dataset.

To complement the machine-learning results, we conducted a Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test on the wrist Co-Contraction Index (CCI), which revealed a highly significant effect of stump etiology on agonist–antagonist coactivation at the wrists (Kruskal–Wallis p ≈ 1.6 × 10−23). Follow-up Dunn–Sidak tests revealed that:

- non-impaired group (Group 1) demonstrated significantly lower CCI values compared to the impaired group due to trauma (Group 2; p < 0.001)

- non-impaired group (Group 1) also exhibited lower CCI than the impaired group due to people with amputation from electrical burns (Group 3; p < 0.001)

- The impaired group due to electrical burn displayed higher CCI than people with amputation from trauma (p < 0.001)

These results indicate a progressive rise in muscle coactivation from non-impaired individuals to impaired groups due to trauma and then to electrical burn. In myoelectric prosthesis control, heightened coactivation may obscure the distinction between flexor and extensor signals, potentially impairing classifier performance. Including CCI not only enhances the distinction among user groups but also underscores the necessity for etiology-specific signal processing and training methods to refine intuitive and reliable prosthetic control.

For the elbow, the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test revealed widespread between-group differences across the evaluated sEMG features. The majority of features produced highly significant Kruskal–Wallis results (p < 0.05), and post-hoc pairwise tests showed consistent contrasts among Groups 1, 2, and 3 for those features. A subset of amplitude and energy features—RMS, IEMG, MAV, and VAR—displayed the largest and most reliable separations, with pairwise differences significant for all tested groups. Frequency and complexity measures (MDF, PKF, WENT, FR, ZC, and WAMP) also differed across groups, indicating systematic alterations in signal spectral content and motor-unit behavior. These results suggest that elbow sEMG in electrical-burn and trauma impaired participants exhibits both altered magnitude and distinct temporal–spectral structure compared with non-impaired participants.

To determine whether the existing dataset had sufficient statistical power to detect differences in CCI between groups, a nonparametric power analysis was performed. Participants’ signal samples were divided into three categories based on stump etiology: healthy controls (n = 18,129), people with amputation from trauma (n = 2063), and people with amputation from electrical burns (n = 14,579). Given the disparities in group sizes and the characteristics of the sEMG data, the Kruskal–Wallis test was chosen to assess differences in CCI across groups. The resulting test statistic facilitated the calculation of effect size (η2), which was subsequently transformed into Cohen’s f to estimate the required sample sizes using a one-way ANOVA framework. With an α level of 0.05 and a target power of 0.8, the minimum sample size per group was calculated to be 1567. Each group in the dataset surpassed this minimum requirement, demonstrating that the study was adequately powered to identify significant differences in CCI across stump etiology categories.

4. Discussion

Our point is to present some trends; however, it is crucial to clarify that this study remains preclinical and exploratory. The limited sample size and the variability in sEMG signals among people with amputation, especially those with electrical burn injuries, constrain the generalizability of our conclusions. Instead of presenting definitive claims, our results highlight emerging patterns that warrant further examination in larger, longitudinal studies.

One of the main difficulties in assessing sEMG signals in impaired participants—whether from trauma or electrical burns—is the precise placement of electrodes, as expressed in this work. Changes in anatomy, such as differences in the shape of the residual limb and modifications in muscle structure, make the standard SENIAM guidelines unsuitable for these individuals. Although following SENIAM ensured uniformity among non-impaired participants, the necessary changes for participants with amputation inevitably introduced biases in spatial sampling. Indeed, research shows that even a 10 mm shift can alter sEMG characteristics (like RMS and mean frequency), thereby disproportionately enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio in these participants. This poses a significant issue for control systems that rely on gesture recognition via sEMG, as improper electrode placement reduces system reliability and overall effectiveness of human–machine interfaces.

To overcome this challenge, our proposed methodology employs an auscultation method during voluntary wrist flexion and extension to accurately pinpoint the muscle belly—the area of greatest muscle prominence. By positioning electrodes directly on the muscle belly, our method aims to obtain a more representative sEMG signal and minimize spatial sampling bias. Future research will need to evaluate the accuracy and dependability of this muscle belly–based placement technique compared to traditional SENIAM-based methods, as outlined in and further developed by the process suggested in [42]. Such comparative studies will inform the development of standardized protocols that accommodate the specific anatomical features of populations of people with amputation, ultimately improving the efficacy of sEMG-based gesture recognition systems.

Beyond the technical challenges, we observed that groups of people with amputation from electrical burns exhibit higher CCI scores, which correlate with increased energy expenditure that may be due to stump reshaping during surgery or to the amputation’s etiology. The clinical implications of our findings underscore the urgent need for further research in conventional prosthetic control paradigms, raising concerns about the viability of traditional two-site myoelectric controllers. Fatigue-driven abandonment rates exceed 50% in this population [43], underscoring the imperative for adaptive control mechanisms. The statistical analysis conducted reveals significant differences that support these findings. Emerging solutions, such as dual-stage classifiers with real-time gain adjustments and inertial measurement fusion for recalibrating thresholds in deep learning high-density sEMG control schemes, have demonstrated high accuracy in identifying users’ intentions for controlling prostheses [14,25,44].

At the heart of these functional impairments lies the neuromuscular complexity of the CCI. Feature-selection algorithms—ReliefF and MRMR—consistently highlight CCI as a primary differentiator between healthy individuals and individuals with amputations. Biomechanically, electrical burns can cause widespread damage to nerves and muscle fibers, leading to aberrant reinnervation patterns and altered motor unit recruitment. This maladaptive process manifests as heightened coactivation of antagonists, a compensatory mechanism for limb stabilization [23]. In contrast, people with amputation due to trauma tend to retain more structured neuromuscular structures [5].

Across wrist experiments, the Ensemble (bagged trees) yielded the highest mean balanced accuracy and the tightest confidence intervals, showing consistent robustness to changes in the feature set. Adding the Co-Contraction Index (CCI) in Run 2 produced measurable gains for all classifiers, supporting CCI’s role as a discriminative biomarker for stump etiology. Aggressive reduction of the 11-feature set in Run 3 lowered peak accuracies across all models, revealing a clear trade-off between model compactness and predictive performance and underscoring the need for rigorous feature-selection validation when targeting lightweight, real-time systems.

Ensemble superiority is expected from theory and EMG applications: bagging reduces variance from noisy, nonstationary windows, while decision-tree splits naturally model nonlinear, mixed-scale interactions (including cross-dependencies involving CCI) that single-margin SVMs and distance-based KNNs represent less effectively on imbalanced, heterogeneous sEMG data. KNN’s sensitivity to intra-class dispersion and SVM’s dependence on a well-balanced, informative feature space explain their lower and more variable window-wise performance [45]. This robustness improves control reliability by reducing spurious command switches, but increases inference latency, memory footprint, and energy use on embedded prosthesis hardware.

We note two important methodological caveats that do not overturn our observed trends but require targeted follow-up. First, the reported large “n” counts for CCI reflect windowed signal segments rather than independent participants; therefore, statistical power computed across windows does not translate to participant-level inference. Third, we performed multiple tests across many features and post hoc comparisons without an explicit family-wise error or false discovery rate correction, which increases the risk of Type I errors. In this exploratory pilot, we prioritized sensitivity to detect candidate biomarkers (CCI), but plan confirmatory analyses that apply appropriate multiplicity control (for example, FDR or hierarchical testing), subject-level aggregation, and mixed-model inference to produce definitive, generalizable conclusions.

By addressing the nuances of electrode placement bias, recalibrating adaptive control strategies, contextualizing CCI within neuromuscular pathology, and optimizing prosthetic paradigms, our study reinforces the translational relevance of sEMG-based prosthetic applications. Future research must advance these methodologies to ensure that prosthetic systems are not only biologically informed but also pragmatically optimized for real-world use.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study reveals preliminary differences in how wrist and elbow muscles activate between healthy individuals and people with transradial amputation, particularly those affected by traumatic injuries and electrical burns. People with amputation from electrical burn-related injuries showed stronger positive correlations in wrist flexion–extension muscles, suggesting a tendency toward increased co-contraction as an adaptive mechanism. These observations were illustrated through correlation heatmaps and supported by analyses that identified the CCI as a significant sEMG feature distinguishing the different causes of amputation. Including the Co-Contraction Index (CCI) improved window-wise balanced accuracy across classifiers on the wrist dataset (for example, Ensemble enhanced from 85.40% to 89.39% between Run 1 and Run 2). Overall, Ensemble produced the highest mean accuracies across runs, and CCI emerged as an informative biomarker for distinguishing stump etiologies. Aggressive feature reduction reduced peak performance (Run 3), highlighting the trade-off between model compactness and accuracy for real-time prosthetic control.

The heightened co-contraction observed in people with amputation from electrical burns may indicate they exert greater muscular effort when using myoelectric prosthetics, raising important questions about the effectiveness of traditional control methods that rely on straightforward agonist-antagonist pairing. Although these findings are not conclusive, they suggest the need for more tailored or adaptable control strategies that align with the user’s unique motor characteristics and the type of injury. This is a first approach to analyze the viability of sEMG and CCI control of myoelectrical prosthesis for people with amputation from electrical burns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.-M., I.Q.-U., I.G.E.J., G.R.-R.; Methodology, A.G.-M., A.A.-M., I.G.E.J., G.R.-R., L.N.-C.; Software, A.G.-M.; Formal analysis, A.G.-M., G.R.-R.; Investigation, A.G.-M., A.A.-M.; Resources, I.G.E.J.; Writing—original draft preparation, G.R.-R., L.N.-C.; Writing—review and editing, A.G.-M., I.Q.-U., A.A.-M., G.R.-R., L.N.-C.; Supervision, I.Q.-U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of The National Institute of Rehabilitation, Mexico (protocol code 02/18 AC and date of approval 24 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://github.com/canibulin/sEMGAmputeeTraumaElectricalBurn, 12 August 2025.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Marco Antonio De la Torre Larios for his invaluable assistance in recruiting study participants and for conducting the medical evaluations of the patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAC | Average Amplitude Change |

| ADLs | Activities of Daily Living |

| CCI | Co-Contraction Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DASDV | Difference Absolute Standard Deviation Value |

| FR | Frequency Ratio |

| Hz | Hertz |

| IEMG | Integrated sEMG |

| INR | National Institute of Rehabilitation |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LOG | Log Detector |

| MAV | Mean Absolute Value |

| MDF | Median Frequency |

| MNF | Mean Frequency |

| MRMR | Minimal Redundancy Maximum Relevance |

| MYOP | Myopulse Percentage Rate |

| PKF | Peak Frequency |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SENIAM | Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles |

| sEMG | Surface Electromyography |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| VAR | Variance |

| WAMP | Willison Amplitude |

| WENT | Wavelet Energy |

| WL | Waveform Length |

References

- Grushko, S.; Spurný, T.; Černý, M. Control Methods for Transradial Prostheses Based on Remnant Muscle Activity and Its Relationship with Proprioceptive Feedback. Sensors 2020, 20, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, F.; Mereu, F.; Gentile, C.; Cordella, F.; Gruppioni, E.; Zollo, L. Hierarchical Strategy for SEMG Classification of the Hand/Wrist Gestures and Forces of Transradial Amputees. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17, 1092006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarinia, F.; Maleki, A. Automated Estimation of Clinical Parameters by Recurrence Quantification Analysis of Surface EMG for Agonist/Antagonist Muscles in Amputees. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Reyes, A.; Canul, M.; Gurza, O.; Cruzado, S.; Díaz, J.; Brieva, J.; Moya-Albor, E.; Ponce, H. SCOMA Hand Prosthetic. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Mechatronics, Electronics and Automotive Engineering (ICMEAE), Cuernavaca, Mexico, 22–26 November 2021; pp. 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Wan, B.; Solis-Beach, K.J.; Kowalske, K. Outcomes of Patients with Amputation Following Electrical Burn Injuries. Eur. Burn. J. 2023, 4, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturma, A.; Salminger, S.; Gstoettner, C.; Aszmann, O.C. Modern Myoprostheses in Electric Burn Injuries of the Upper Extremity. In Handbook of Burns; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hargrove, L.; Bao, X.; Kamavuako, E.N. Surface EMG Statistical and Performance Analysis of Targeted-Muscle-Reinnervated (TMR) Transhumeral Prosthesis Users in Home and Laboratory Settings. Sensors 2022, 22, 9849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, J.R. The History of Surface Electromyography. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2003, 28, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portero, P.; Dogadov, A.A.; Servière, C.; Quaine, F. Surface Electromyography in Physiotherapist Educational Program in France: Enhancing Learning SEMG in Stretching Practice. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 584304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Ting, S.W.H.; Hsiao, S.M.; Huang, C.M.; Wu, W.Y. Efficacy of Bio-Assisted Pelvic Floor Muscle Training in Women with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 251, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Gawda, P. Surface Electromyography in Dentistry—Past, Present and Future. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.; Alam, N. Comprehensive Comparative Analysis of Lower Limb Exoskeleton Research: Control, Design, and Application. Actuators 2025, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, F.; Gentile, C.; Ciancio, A.L.; Gruppioni, E.; Davalli, A.; Sacchetti, R.; Guglielmelli, E.; Zollo, L. Simultaneous SEMG Classification of Hand/Wrist Gestures and Forces. Front. Neurorobot. 2019, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, H.; Englehart, K.; Hargrove, L.; Kuruganti, U. High Density Electromyography Data of Normally Limbed and Transradial Amputee Subjects for Multifunction Prosthetic Control. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2012, 22, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Phinyomark, A.; Al-Timemy, A.H.; Khushaba, R.N.; Petri, G.; Scheme, E. Differences in EMG Feature Space between Able-Bodied and Amputee Subjects for Myoelectric Control. In Proceedings of the International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering, NER 2019, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 March 2019; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, M.; Gijsberts, A.; Castellini, C.; Caputo, B.; Hager, A.-G.M.; Elsig, S.; Giatsidis, G.; Bassetto, F.; Müller, H. Electromyography Data for Non-Invasive Naturally-Controlled Robotic Hand Prostheses. Sci. Data 2014, 1, 140053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, M.C.; Fenn, S.L.; Black, L.D. 3rd Applications of Cardiac Extracellular Matrix in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1098, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Niu, X.; Zhang, J.; Fu, X. Improving Motion Intention Recognition for Trans-Radial Amputees Based on SEMG and Transfer Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, V.; Carpinella, I.; Marzegan, A.; Jonsdottir, J.; Frigo, C.A.; Avanzino, L.; Pelosin, E.; Ferrarin, M.; Lencioni, T. Surface-Electromyography-Based Co-Contraction Index for Monitoring Upper Limb Improvements in Post-Stroke Rehabilitation: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Secondary Analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Sierra, P.; Feijoó Rodriguez, C.; Sánchez López de Pablo, C.; Urendes Jiménez, E.J.; Raya López, R. Estudio Del Coeficiente de Coactivación Muscular En Flexo-Extensión de Codo En Distintas Condiciones de Peso Con El Uso de EMG. Jorn. De Automática 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Li, T. Gene Selection Algorithm by Combining ReliefF and MRMR. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.T.P.y.; Motta, F.S.H. Incidence of Amputation of Extremities Secondary to Electrical Burn in the Burn Unit of the National Medical Center «20 de Noviembre» ISSSTE. Cirugía Plástica 2014, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedali, M.; Czerniecki, J.M.; Morgenroth, D.C.; Hahn, M.E. Co-Contraction Patterns of Trans-Tibial Amputee Ankle and Knee Musculature during Gait. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sîmpetru, R.C.; Braun, D.I.; Simon, A.U.; März, M.; Cnejevici, V.; de Oliveira, D.S.; Weber, N.; Walter, J.; Franke, J.; Höglinger, D.; et al. MyoGestic: EMG Interfacing Framework for Decoding Multiple Spared Motor Dimensions in Individuals with Neural Lesions. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads9150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.E.; Allen, J.M.; Elbasiouny, S.M. Adaptive Neural Decoder for Prosthetic Hand Control. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 590775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, U.; Sherman, A.L. Muscle Strength Grading. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436008/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Stegeman, D.; Hermens, H. Standards for Suface Electromyography: The European Project Surface EMG for Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles (SENIAM). 2007. Volume 1. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hermie-Hermens/publication/228486725_Standards_for_suface_electromyography_The_European_project_Surface_EMG_for_non-invasive_assessment_of_muscles_SENIAM/links/09e41508ec1dbd8a6d000000/Standards-for-suface-electromyography-The-European-project-Surface-EMG-for-non-invasive-assessment-of-muscles-SENIAM.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Rose, W. Standards for Reporting EMG Data. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2018, 38, I–II. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Data—Shimmer Wearable Sensor Technology. Available online: https://www.shimmersensing.com/support/sample-data/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- ADS129x. Available online: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/ads1292r.pdf?ts=1753147195119&ref_url=https%253A%252F%252Fwww.mouser.it%252F (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Boyer, M.; Bouyer, L.; Roy, J.S.; Campeau-Lecours, A. Reducing Noise, Artifacts and Interference in Single-Channel EMG Signals: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- User EMG User Guide Revision 1.12. Available online: https://shimmersensing.com/wp-content/docs/support/documentation/ECG_User_Guide_Rev1.12.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Fuentes del Toro, S.; Aranda-Ruiz, J. The Impact of Normalization Procedures on Surface Electromyography (SEMG) Data Integrity: A Study of Bicep and Tricep Muscle Signal Analysis. Sensors 2025, 25, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Source Data Labeling | Label Studio. Available online: https://labelstud.io/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Gallón, V.M.; Vélez, S.M.; Ramírez, J.; Bolaños, F. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms and Feature Extraction Techniques for the Automatic Detection of Surface EMG Activation Timing. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 94, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Perez, D.C.; Aviles, M.; Gomez-Loenzo, R.A.; Rodriguez-Resendiz, J. Feature Set to SEMG Classification Obtained with Fisher Score. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 13962–13970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles, M.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J.; Ibrahimi, D. Optimizing EMG Classification through Metaheuristic Algorithms. Technologies 2023, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moctar, S.M.S.; Rida, I.; Boudaoud, S. Time-Domain Features for SEMG Signal Classification: A Brief Survey. JETSAN 2023, 2023, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanghieri, M. SEMG-Based Hand Gesture Recognition with Deep Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.10954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firuzi, R.; Ahmadyani, H.; Abdi, M.F.; Naderi, D.; Hassan, J.; Bokani, A. Decoding Neural Signals with Computational Models: A Systematic Review of Invasive BMI. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.03324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Marybeth, B. Daniels & Worthingham’s Muscle Testing. In Techniques of Manual Examination & Performance Testing, 10th ed.; Saunders: Riverside, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 9780323569149. [Google Scholar]

- Rostamjoud, F.; Orkelsdóttir, F.B.; Sverrisson, A.Ö.; Brynjólfsson, S.; Briem, K. Improving Electromyography Electrode Placement Accuracy in Transtibial Amputees: A Comparative Study of Ultrasound and Palpation Methods. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 33, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.R.; Olivier, J.; Pagel, A.; Bleuler, H.; Bouri, M.; Lambercy, O.; Del Millán, J.R.; Riener, R.; Vallery, H.; Gassert, R. Control Strategies for Active Lower Extremity Prosthetics and Orthotics: A Review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2015, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Bi, S.; Zhang, G.; Cao, G. High-Density Surface EMG-Based Gesture Recognition Using a 3D Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2020, 20, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietterich, T.G. Ensemble Methods in Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), Corvallis, OR, USA, 1 January 2000; Volume 1857. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).