Abstract

Background: This study evaluated the influence of various decontamination protocols after salivary contamination on the micro-shear bond strength (µSBS) between monolithic high-translucency zirconia and resin cement. Methods: A total of 81 multilayer (ML) monolithic–translucent zirconia discs of 10 mm diameter and 2 mm thickness (DD cubeX2 ML, Dental Direkt) were fabricated, sintered, and polished using silicon–carbide papers. The bonding surfaces were treated with 50-μm Al2O3 using a Renfert sandblaster at 0.3 MPa for 20 s. Fifty samples were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 10). A control group consisted of clean, uncontaminated samples, while the other four groups were contaminated and cleaned using water, sodium hypochlorite, phosphoric acid + ethanol, or Ivoclean, respectively. Resin cement cylinders (Panavia V5, Kuraray Noritake) were bonded onto the zirconia surfaces. The µSBS was evaluated after simulated ageing using a universal testing machine. Failure modes were analysed by light microscopy. Surface morphology was evaluated using a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM), and the chemical surface was assessed with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy. Surface wettability was assessed through contact angle measurements. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD was used to compare µSBS between groups. Results: Among the tested groups, the control group exhibited the highest µSBS value (59.5 ± 4.2 MPa), followed by Ivoclean (56.7 ± 4.8 MPa), phosphoric acid + ethanol (46.8 ± 4.7 MPa), and sodium hypochlorite (41.1 ± 5.7 MPa), with the lowest value observed with water (33.5 ± 6.3 MPa). All groups exhibited adhesive failure, with no sign of cohesive or mixed failures. SEM analysis showed no effect on zirconia crystallinity or sandblasting, while Ivoclean left residual zirconium oxide particles. Furthermore, XPS and FTIR analysis revealed favourable chemical changes after Ivoclean treatment, correlating with improved bonding performance. Contact angle measurements confirmed greater surface wettability in the Ivoclean group, resulting in strong bond strength. Conclusions: Ivoclean significantly increased the resin–zirconia bond strength after saliva contamination, showing more reliable results compared to others. Phosphoric acid + ethanol showed the second-highest mean strength, while water showed the least effectiveness.

1. Introduction

High-translucency zirconia (5Y-TZP) is a recent generation of materials designed for highly aesthetic fixed dental restorations. Due to its higher yttria content, 5Y-TZP exhibits an increased fraction of the cubic phase and therefore greater optical translucency, better mimicking natural dentition, particularly in the anterior region [1]. This improvement in appearance, however, is accompanied by reduced transformation toughening and a moderate decrease in flexural strength compared with conventional 3Y-TZP. As a result, long-term clinical performance becomes more dependent on reliable bonding to resin cement, rather than solely on bulk fracture resistance.

Despite this, high-translucency zirconia still exhibits clinically acceptable mechanical behaviour, with reported flexural strength values in the range of approximately 800–1200 MPa, along with favourable fracture toughness. In addition, 5Y-TZP maintains key advantages associated with zirconia ceramics, including high biocompatibility, chemical stability, and resistance to intraoral degradation [2].

The longevity and long-term success of fixed ceramic dental restorations—crowns, bridges, and veneers—depend directly on the cementation procedure. Adhesion varies by substrate [3]; resin cements bond to enamel and dentin through micro-mechanical retention and chemical interaction [4].

Adhesion to high-strength zirconia presents another challenge. Unlike lithium disilicate, zirconia lacks a glassy phase matrix and is thus insensitive to conventional hydrofluoric acid etching [5]. Surface treatments like sandblasting, phosphate monomer-based primers [e.g., methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (10-MDP)], and dual-cure or self-adhesive resin cements are used to improve bonding by enhancing chemical and mechanical retention at the ceramic–cement interface [6]. As a result, cementation is not only a mechanical procedure but also a crucial chemical and structural interface that greatly affects the prosthesis’s initial fixation and long-term functionality [7].

One of the main causes of impaired bond quality, among clinical variables, is contamination, which takes place during try-in procedures. Residual organic material from try-in pastes, blood, or saliva hinders micromechanical adaptation and obstructs the chemical affinity of primers [8]. Saliva is a complicated contaminant, as it contains proteins, phospholipids, enzymes, and phosphate groups that can adhere firmly to zirconia surfaces. These components can establish stable, protein-rich films on the surface through ionic and other physicochemical interactions. Zirconia has a strong affinity for molecules that contain phosphate, which makes decontamination especially difficult. Effective decontamination of the zirconia surface is essential to ensure optimal bonding because resin–zirconia bonds are weaker than those of dentin or enamel. [9]. Several studies have demonstrated that Ivoclean effectively eliminates organic contaminants without compromising zirconia properties [10]. However, its high cost and limited availability in dental clinics restrict its routine use. This creates a need to find more affordable and accessible alternatives that can achieve comparable or satisfactory resin–zirconia bond strength.

Mechanical cleaning methods (e.g., with water) and chemical agents, such as 5.25% sodium hypochlorite or 37% phosphoric acid with 96% ethanol, were selected due to their availability, practicality, and established use for disinfecting prosthetic restorations [11]. A combination of 37% phosphoric acid and 96% ethanol has been suggested to enhance surface decontamination. Furthermore, few studies have directly compared Ivoclean with these alternatives in terms of their effect on bond strength. Although short-term bond strength improvement has been reported, the long-term durability of zirconia–resin bonds remains unclear.

The Objective

This research investigated the impact of various cleaning techniques—distilled water, sodium hypochlorite, phosphoric acid, ethanol, and Ivoclean—on the micro-shear bond strength (μSBS) between resin cement and high-translucency zirconia after salivary contamination. The study had six primary goals:

- (1)

- To determine the effect of these decontamination procedures on μSBS using a universal testing machine

- (2)

- To evaluate failure modes of all experimental groups after bond testing with light microscopy

- (3)

- To analyse the surface topography of zirconia before and after contamination, and after each cleaning protocol, using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM)

- (4)

- To identify the chemical state and decontamination efficiency of zirconia through X-ray photoelectron spectroscope (XPS) and Fourier–transform infrared spectroscope (FTIR)

- (5)

- To evaluate the surface wettability of zirconia before and after cleaning by measuring the contact angle, to assess its impact on bond strength to resin cement.

The null hypotheses are: (H01) there is no statistically significant difference in μSBS between the cleaning methods tested after salivary contamination; and (H02) the failure mode distribution is not significantly different between experimental groups after μSBS testing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Description

Monolithic high-translucency zirconia material (DD cubeX2 ML, 5Y-TZP, Dental Direct, Spenge, Germany) was used to create disc-shaped specimens. Each disc measured 10 mm in diameter and 2 mm in thickness. The discs were milled from pre-sintered blanks using a 5-axis milling machine (Imes-Icore DWX-52Di, Kyoto, Japan), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Following milling, all specimens were sintered in a high-temperature furnace, undergoing approximately 20% shrinkage, achieving full densification and the final dimensions [12].

After sintering, the disc surfaces were sequentially polished using waterproof silicon carbide abrasive papers of 600, 800, and 1200 grit to standardise surface smoothness. Subsequently, surface roughness was increased by airborne-particle abrasion with 50-µm aluminium oxide (Al2O3) particles applied with a Renfert sandblaster (Renfert GmbH, Hilzingen, Germany)at 0.3 MPa for 20 s [13]. Earlier to any surface treatment, all samples were cleaned using an ultrasonic cleaner (Sunshine, Guangzhou, China) in distilled water for 3 min to eliminate any residual contaminants [14].

2.2. Saliva Contamination

Unstimulated human saliva from two healthy adults was collected to simulate clinical contamination during dental try-in procedures (REC:REC196). The saliva was used fresh, without any processing, and applied directly onto the zirconia discs for 60 s at 37 °C to reflect intraoral conditions. To ensure consistent contamination across all samples, the application was performed simultaneously under controlled conditions for all groups except the control group [15].

2.3. Cleansing Protocols

To assess the effectiveness of different surface decontamination methods on the μSBS between resin cement and saliva-contaminated zirconia, four different cleaning protocols were tested. A total of 50 zirconia specimens were divided randomly into five groups (n = 10 per group). The first group served as an uncontaminated control, while the remaining groups were contaminated with saliva and cleaned using different protocols. The experimental groups are summarised below.

- Control group: specimens were not contaminated and did not undergo any cleaning.

- Distilled Water: contaminated specimens were rinsed with distilled water for 30 s and air-dried for 10 s.

- Sodium Hypochlorite (5.25%): After air-drying, contaminated specimens were treated with 5.25% NaOCl (Promida, Istanbul, Turkey) for 30 s using gentle agitation, then rinsed with tap water and air-dried [16].

- Phosphoric Acid (37%) + Ethanol (96%): Contaminated surfaces were cleaned with 37% phosphoric acid (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) for 30 s, rinsed thoroughly, air-dried, then immersed in 96% ethanol (Aljoud, Baghdad, Iraq) for 2 min, before final air-drying.

- Ivoclean: Contaminated specimens were treated with Ivoclean (Ivoclar Vivadent, Liechtenstein) for 20 s, rinsed with tap water, and air-dried.

2.4. Surface Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the cleansing protocols, 31 zirconia specimens were characterised by their elemental composition and surface morphology using advanced analytical techniques. Analysis was performed on samples from the following conditions: control, saliva-contaminated without cleaning, cleaned with phosphoric acid only, and the four different cleaning protocols.

The following methods were employed for surface characterisation:

- Field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

The surface characteristics of selected zirconia specimens were analysed using a FESEM (Tescan Mira3, Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic). The samples were coated with a thin layer of gold using a sputter coater to enhance electrical conductivity. Images were made at a magnification of 5000× [17].

- 2.

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS analysis was conducted to analyse the elemental composition and chemical states on the zirconia surface. A K-ALPHA spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with monochromatic Al Ka radiation was used under a vacuum pressure of approximately 10−9 mbar, with a 400 μm spot size and a pass energy of 200 eV for survey scans and 50 eV for high-resolution spectra, at a 45° emission angle [18]. The analysis focused on the elements carbon (C), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and zirconium (Zr), and elemental ratios (C:O, O:Zr, C:Zr, and N:Zr) were calculated to assess surface composition [19].

- 3.

- Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

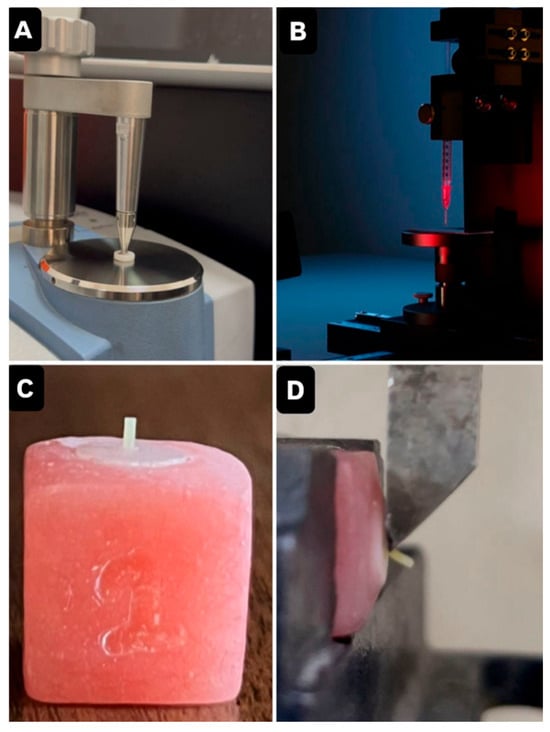

FTIR was carried out using a Bruker Tensor II spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, Germany) to detect chemical changes on zirconia surfaces. The analysis focused on the 1000–1200 cm−1 range, where phosphate-related bands indicate salivary residues that may interfere with resin bonding. This technique helped compare cleaning protocols in terms of their effectiveness in removing such contaminants [20] (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) FTIR Device. (B) Contact angle measurement. (C) Final zirconia-resin cement samples. (D) Load applied to the resin/zirconia surface interface.

- 4.

- Contact angle

The contact angle was measured to evaluate zirconia surface wettability, using a goniometer (CAM110P, Creating Nano Tech, Taiwan). A liquid droplet was placed on each specimen surface, and high-resolution imaging software was used to determine the contact angles on both sides of the droplet. The mean value was calculated. A contact angle greater than 90° indicates a hydrophobic surface with reduced adhesion potential, whereas a contact angle below 90° reflects hydrophilic behaviour [20] (Figure 1B).

2.5. Bonding Procedure

Prior to cementation, 10-MDP-containing primer (Clearfil Ceramic Primer Plus, Kuraray Noritake, Okayama, Japan) was applied to the zirconia surface for 1 min and air-dried. Resin cement (Panavia V5, Kuraray Noritake, Okayama, Japan) was injected into polyethene tubes (3 mm height, 1.0 mm inner diameter) placed on each specimen using an auto-mix tip to avoid air entrapment. The cement was then light cured for 40 s using an LED unit (Eighteeth, Changzhou Sifary Medical Technology Co. Ltd., Changzhou, China; 1100 mW/cm2). Excess cement was removed, and after 10 min, the tubes were sectioned with a no. 11 blade [21] (Figure 1C). Before thermocycling, all samples were immersed in distilled water at 37 °C for 24 h [22].

2.6. Thermal Ageing Technique

To stimulate intraoral ageing, the specimens were subjected to 5000 thermocycles between 5 ± 2 °C and 55 ± 2 °C, with a dwell time of 30 s in each bath, using an automatic thermocycling machine (Thermocycler THE-1100 machine; SD Mechatronik Feldkirchen, Westerham, Germany).

2.7. Micro-Shear Bond Strength (uSBS)

µSBS was measured using a universal testing machine (Tinius Olsen H50KT, Redhill, UK). Shear force was applied to the zirconia–resin interface at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. Bond strength was calculated by dividing the load at failure by the bonded area and expressed in MPa [23] (Figure 1D).

2.8. Failure Mode

After the μSBS test, fractured samples were examined under a digital microscope (10× magnification). Failure modes were classified as: adhesive (no resin on zirconia), cohesive (surface fully covered with resin), or mixed (partial remnants of resin and zirconia) [24].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS Statistics, version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) with a significance level set at 0.05. Normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD was used to compare bond strength between groups, while Fisher’s Exact Test was used to assess the difference in failure mode distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

A total of 50 µSBS values were recorded from the five groups with different surface decontamination protocols. The minimum, maximum, standard deviation, and mean of each group are given in Table 1. The group treated with water demonstrated the lowest mean µSBS (33.5 ± 6.3 MPa). The control group demonstrated the highest bond (59.5 ± 4.2 MPa), followed by Ivoclean (56.7 ± 4.8 MPa). Normality testing confirmed a normal distribution for all groups (p > 0.05). One-way ANOVA indicated significant differences in µSBS between the five groups (p < 0.009), as presented in Table 2. Post hoc Tukey’s HSD test, presented in Table 3, revealed significant differences among most group pairs, except between control and Ivoclean, and NaOCl and H3PO4 + ethanol (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of µSBS (MPa).

Table 2.

One-way ANOVA results between groups.

Table 3.

Tukey HSD Test Results Among Different Groups.

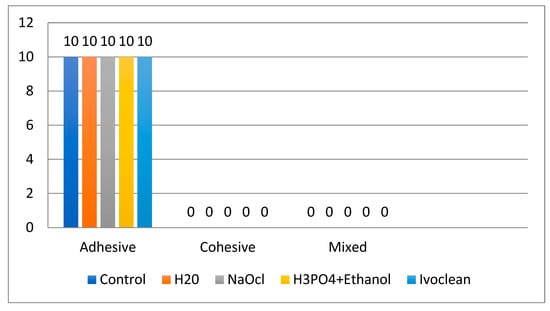

3.2. Failure Mode Analysis

Failure analysis showed 100% adhesive failure in all groups without any cohesive or mixed failures. This suggests consistent failure at the zirconia–resin interface in all treatments (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bar chart illustrating mode of failure among groups.

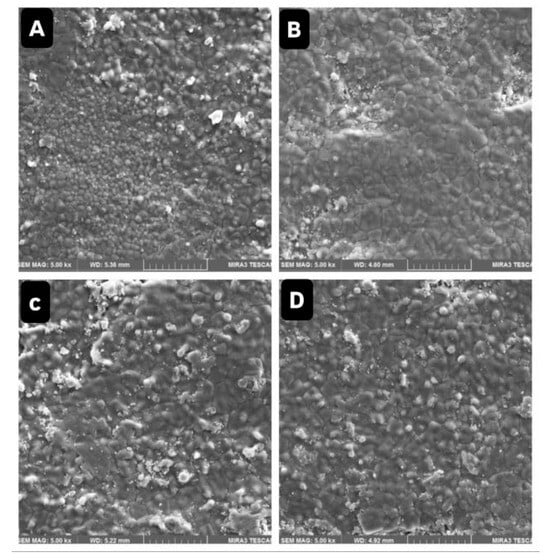

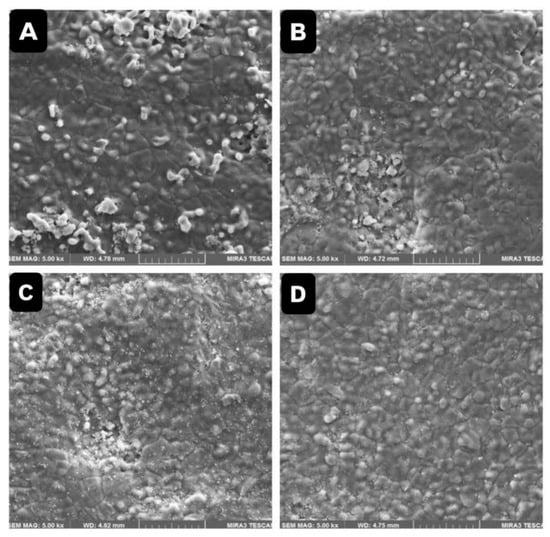

3.3. Surface Morphology by FESEM

FESEM analysis revealed no surface cracks or structural degradation visible following cleaning. However, a roughened surface texture from airborne-particle abrasion was consistently present (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Non-uniform zirconium oxide (ZrO2) particle deposits were detected in Ivoclean-treated samples (Figure 4C,D), potentially compromising surface homogeneity.

Figure 3.

The FESEM showed surface morphology of various zirconia samples at 5000× magnification. (A) Clean zirconia without contamination. (B) Zirconia contaminated with saliva without cleaning. (C) Zirconia contaminated with saliva and cleaned with water. (D) Zirconia contaminated with saliva and cleaned with NaOCl.

Figure 4.

The FESEM showed surface morphology of various zirconia samples at 5000× magnification. (A) Contaminated zirconia with saliva and cleaned with (H3PO4) + ethanol. (B) Contaminated zirconia with saliva and cleaned (H3PO4) only. (C,D) Contaminated zirconia with saliva and cleaned with Ivoclean.

3.4. FTIR Spectroscopy

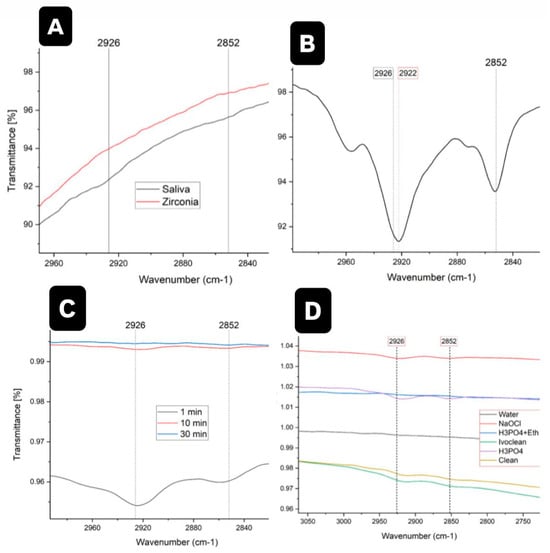

FTIR was used to detect phospholipids in saliva, focusing on the absorption bands at 2852 cm−1 and 2926 cm−1, corresponding to lipid acyl CH2 groups. Tests on the first volunteer showed no detectable phospholipids (Figure 5A), prompting the use of saliva from the second volunteer, in which the presence of phospholipids was confirmed (Figure 5B). Zirconia samples were contaminated with saliva for varying durations (1, 10, and 30 min). Phospholipids were detected in all samples, with the highest concentration found in the 1 min contamination (Figure 5C). After contamination, cleaning with water and phosphoric acid + ethanol removed phospholipids, while cleaning with sodium hypochlorite and Ivoclean left residues. FTIR spectra (Figure 5D) confirmed complete removal by water and phosphoric acid + ethanol.

Figure 5.

(A) FTIR for saliva sample (initial testing) from the first volunteer. (B) FTIR for Saliva samples collected from the second volunteer. (C) FTIR for zirconia samples contaminated with saliva for 1, 10, and 30 Minutes. (D) FTIR for zirconia samples contaminated with saliva and cleaned using various cleaning agents.

3.5. XPS

XPS findings indicated that saliva and subsequent cleaning altered the zirconia surface composition. In the control specimens, nitrogen (N1s) was not detected, suggesting a clean surface. After saliva exposure, carbon and oxygen increased, and zirconium (Zr3d) decreased to 52.37%, confirming the presence of organic residues and proteins. Water rinsing achieved minimal decontamination. In contrast, the combined application of 37% phosphoric acid and 96% ethanol yielded the best results, with zirconium increasing to 10.59% and carbon decreasing to 42.16%. Other cleaning protocols exhibited moderate efficacy (Table 4).

Table 4.

XPS-Atomic Percentages of Elements on Zirconia Surfaces Before and After Cleaning Treatments.

3.6. Contact Angle Measurement

Contact angle measurements indicate saliva contamination reduces surface wettability in (36.00° vs. 27.27° in the control). Cleaning with Ivoclean provided the greatest enhancement (75.60°), followed by H3PO4 + ethanol (77.73°) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Contact Angle Measurements of Zirconia Samples.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effect of different cleaning protocols on saliva-contaminated zirconia to identify which provides the most effective durable bond strength after simulated ageing. The cleaning method had a significant influence on bond strength, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis that zirconia cleaning procedures would not affect its bonding to resin cement.

The results of this study indicate that a clean, non-contaminated zirconia surface has the highest µSBS, consistent with its surface characteristics. Elemental analysis showed that this surface was dominated by zirconium and exhibited only minor carbon and oxygen signals, indicating minimal organic deposition. XPS further supported this observation: no nitrogen (N1s) was detected on the clean surface, consistent with the absence of adsorbed salivary protein. In addition, the clean zirconia showed the lowest contact angle value among all groups, reflecting a more wettable surface. Together, these findings indicate that an uncontaminated zirconia surface remains chemically available for interaction with functional phosphate monomers, which is essential for durable bonding to resin cement. These observations are consistent with previous reports that emphasise preserving a clean zirconia surface as critical for achieving predictable adhesion in restorative dentistry [25,26]. After contamination, water rinsing alone was insufficient for removing salivary contaminants from zirconia surfaces, resulting in the lowest µSBS. FTIR after water rinsing showed a flat spectrum, indicating partial phospholipid removal due to physicochemical interactions between the hydrophilic zirconia surface and polar water molecules [27]. However, FTIR’s limited sensitivity to thin organic layers means residual contaminants may persist. XPS analysis revealed increased carbon and nitrogen levels, along with reduced zirconium signal, consistent with persistent salivary proteins and phospholipids. Meanwhile, contact-angle measurements further confirmed increased hydrophobicity and reduced wettability, additional signs of hindered resin infiltration.

These findings align with previous studies reporting that water is inadequate for effective decontamination [28,29]. Although some conflicting reports exist, such discrepancies may stem from variations in contamination protocols [30].

Sodium hypochlorite application significantly enhanced µSBS compared to water rinsing. FESEM and XPS analyses confirmed reduced surface residues and increased zirconium exposure, while contact angle showed improved wettability. However, FTIR showed incomplete phospholipid removal, suggesting that insufficient contact time may limit NaOCl’s effectiveness [31]. Its cleaning action is attributed to its strong oxidative action, phospholipid degradation, ester bond hydrolysis, protein denaturation, and enhanced surface-bonding capacity.

These findings agree with a previous study that reported improved surface energy and cleaning performance with NaOCl [32]. However, other studies failed to find significant differences in bond strength compared to water rinsing at lower concentrations or shorter application times [33], indicating that effectiveness depends on concentration, exposure time, and contamination type.

Phosphoric acid alone did not significantly improve resin–zirconia bond strength. XPS analysis showed high carbon levels and reduced zirconium exposure, while FTIR and contact angle measurements confirmed minimal phospholipid removal and moderate wettability. Together, these indicate insufficient decontamination [34]. These findings are consistent with prior studies demonstrating the limited cleaning capacity of phosphoric acid alone [28], largely due to its etching effect, which lowers surface energy and impairs bonding [20,35]. Residual phosphate groups can also block bonding sites critical for 10-MDP adhesion [29,32].

To overcome the limitations of current cleaning agents, a combination of 37% phosphoric acid gel and 96% ethanol was examined. Phosphoric acid facilitates surface etching and partial removal of inorganic and organic contaminants, while ethanol enhances cleaning through dehydration and dissolving hydrophobic salivary residues. The synergistic action improves surface energy and reactivity, promoting stronger and more durable resin–zirconia bonding. Ethanol likely plays the primary role in complete decontamination, as phosphoric acid alone is insufficient [36].

FTIR analysis of the phosphoric acid and ethanol combination showed complete phospholipid removal, while XPS indicated maximum zirconium exposure, and contact angle results demonstrated increased hydrophobicity. These results all indicate improved resin bonding, although with less reactivity than NaOCl. However, some in vitro studies have reported inconsistent results; for instance, Lümkemann et al. [36] observed no significant bond strength advantage with the combined treatment versus individual agents. Future studies should investigate whether increasing the application time of phosphoric acid in combination with ethanol yields improved decontamination results and enhances resin–zirconia bond strength.

Ivoclean exhibited the highest µSBS compared to other groups, confirming its superior decontamination and bonding efficacy after saliva contamination. FTIR of the Ivoclean-treated specimens still showed some detectable organic signal, indicating that traces of salivary residue were not completely eliminated. Taken alone, this finding could suggest incomplete decontamination. However, complementary surface analyses clarify how this group nevertheless achieved the highest bond strength values. XPS revealed a reduction in surface carbon and re-exposure of zirconium, while FESEM showed agglomerated ZrO2 particles remaining on the surface after treatment. These ZrO2-rich particles originate from the alkaline zirconia-based suspension and act as a scavenger layer: they preferentially bind salivary phosphate- and lipid-containing contaminants and, at the same time, re-deposit zirconia-like material on the restoration surface [29]. In practical terms, this process re-establishes chemically active zirconia/oxide sites that can interact with phosphate MDP groups in the primer and resin cement, even if small amounts of organic residue are still present [8]. In addition, ZrO2 deposits increase the local surface texture and provide micromechanical retention sites.

The combination of restored chemical affinity for MDP and enhanced micromechanical interlocking is consistent with the high µSBS measured for the Ivoclean group, outperforming the other cleaning protocols. It should also be noted that effective decontamination with this type of cleaner depends on adequate particle contact and subsequent rinsing [37]. Multiple studies support Ivoclean’s ability to reduce organic and saliva contaminants, improve wettability, and enhance micromechanical interlocking to strengthen bonds [10,31].

Despite these factors, other studies have reported that residual ZrO2 particles may reduce bond strength after thermal ageing [19,35]. One such study noted inconsistent cleaning efficacy, possibly due to incomplete particle contact [38].

In conclusion, Ivoclean improves initial bond strength by reducing organic contamination through ZrO2 particle adsorption but may affect long-term durability, highlighting the need to optimise application and rinsing protocols.

While the Mode of Failure, all specimens exhibited 100% adhesive failure after µSBS testing, indicating inadequate surface decontamination at the zirconia–resin interface. The failure mode distribution was not significantly different between the experimental groups. The persistence of salivary protein- and lipid-rich film, sandblasting-induced surface irregularities that trap contaminants and create uneven stress distribution, and surface energy changes all likely contributed to compromised bonding [39,40]. These findings align with studies reporting the predominance of adhesive failures after Ivoclean use [41,42], although cohesive or mixed failures have been observed under more controlled cleaning protocols [21], underscoring the need for standardised decontamination methods.

Limitations of the Study

- Saliva was the only contaminant used, excluding clinical sources such as blood or silicone.

- Only four of the numerous possible cleaning regimens were tested, without other promising strategies.

- Fixed protocol times were used; variable times could change efficacy.

- Only one resin cement (Panavia V5) was tested alone, limiting generalisability.

- Thermocycling was limited to 5000 cycles, which may not be representative of long-term ageing.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that cleansing protocols distinctly influence µSBS between resin cement and high-translucency zirconia after saliva contamination, with Ivoclean providing the greatest improvement. Saliva contamination significantly reduced adhesion, emphasising the need for thorough surface cleansing in clinical practice. Ivoclean facilitated superior bonding by effectively removing residues, restoring integrity, enhancing chemical interaction with MDP-containing cement, and improving wettability. However, all groups demonstrated adhesive failure at the resin zirconia interface. This underscores the importance of optimised cleansing protocols to achieve a durable and reliable bond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.Z.A. and M.K.G.; methodology, R.Z.A.; software, R.Z.A.; validation, R.Z.A.; formal analysis, R.Z.A.; investigation, R.Z.A.; resources, R.Z.A.; data curation, R.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.A.; writing—review and editing, R.Z.A.; visualisation, R.Z.A.; supervision, M.K.G.; project administration, R.Z.A., M.K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee at Mustansiriyah University, College of Dentistry (Protocol Ref No: REC196, obtained on 1 November 2024). The study was carried out in the Conservative Dentistry Department of Mustansiriyah University, College of Dentistry.

Informed Consent Statement

Saliva was collected from two healthy adult volunteers after obtaining their informed consent. No personal data were used.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy constraints, the data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Emad A. Dashir for his valuable assistance, which contributed to the accuracy of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ban, S.; Yasuoka, Y.; Sugiyama, T.; Matsuura, Y. Translucent and highly toughened zirconia suitable for dental restorations. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavriqi, L.; Traini, T. Mechanical properties of translucent zirconia: An in vitro study. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szawioła-Kirejczyk, M.; Chmura, K.; Gronkiewicz, K.; Gala, A.; Loster, J.E.; Ryniewicz, W. Adhesive cementation of zirconia based ceramics-surface modification methods literature review. Coatings 2022, 12, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.; Hickel, R.; Ilie, N. Adverse effects of salivary contamination for adhesives in restorative dentistry: A literature review. Am. J. Dent. 2017, 30, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alajrash, M.; Kassim, M.; Gholam, M. Effect of different resin luting materials on the marginal fit of lithium disilicate CAD/CAM crowns (a comparative study). Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2020, 14, 1110–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Ebeid, K.; Wille, S.; Salah, T.; Wahsh, M.; Zohdy, M.; Kern, M. Evaluation of the effect of different surface treatments on the bond strength of resin cement to zirconia ceramic. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2018, 62, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kui, A.; Manziuc, M.; Petruțiu, A.; Buduru, S.; Labuneț, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Chisnoiu, A. Translucent Zirconia in Fixed Prosthodontics—An Integrative Overview. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammajaruk, P.; Guazzato, M.; Naorungroj, S. Cleaning methods of contaminated zirconia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, S.; Kondas, V.V.; Dhanasekaran, S.V.; Elavarasu, P.K. Comparative evaluation of shear bond strength of zirconia restorations cleansed with various cleansing protocols bonded with two different resin cements: An in vitro study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2017, 28, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, N.R.; de Araújo, G.M.; Vila-Nova, T.E.L.; Bezerra, M.G.P.G.; dos Santos Calderon, P.; Özcan, M.; de Assunção e Souza, R.O. Which zirconia surface-cleaning strategy improves adhesion of resin composite cement after saliva contamination? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adhes. Dent. 2022, 24, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, H.; Yanikoglu, N.; Sagsöz, N. Effect of MDP-based silane and different surface conditioner methods on bonding of resin cements to zirconium framework. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noori, S.T.; Gholam, M.K. Evaluation of the marginal discrepancy of cobalt chromium metal copings fabricated with additive and subtractive techniques. J. Int. Oral Health 2021, 13, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qaraghuli, A.M.; Gholam, M. The influence of different types of surface treatment on the surface roughness and bond strength of zirconia (an in vitro study). Front. Biomed. Technol. 2025, 37, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.H.; Gholam, M.K. The influence of cement spacer thickness on retentive strength of monolithic zirconia crowns cemented with different luting agents (a comparative in-vitro study). Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2021, 15, 2246–2252. [Google Scholar]

- Feitosa, S.A.; Patel, D.; Borges, A.L.S.; Özcan, M. Effect of cleansing methods on saliva-contaminated zirconia: An XPS and shear bond strength analysis. J. Adhes. Dent. 2014, 16, 427–434. [Google Scholar]

- Phark, J.; Duarte, S.; Blatz, M. Effect of saliva contamination on bond strength of self-adhesive cements to zirconia. Oper. Dent. 2009, 34, 703–710. [Google Scholar]

- Sadid-Zadeh, R.; Strazzella, A.; Li, R.; Makwoka, S. Effect of zirconia etching solution on the shear bond strength between zirconia and resin cement. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lange-Jansen, H.C.; Scharnberg, M.; Wolfart, S.; Ludwig, K.; Adelung, R.; Kern, M. Influence of saliva contamination on zirconia ceramic bonding. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K. Influence of cleaning methods on resin bonding to saliva-contaminated zirconia. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, S.A.; Patel, D.; Borges, A.L.S.; Alshehri, A.; Bottino, M.A.; Özcan, M. Effect of cleansing methods on salivary contamination and bonding to zirconia. Oper. Dent. 2015, 40, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Raja, K.K.; Anniyappan, B.; Soosairaj, C.D.R.; Jayaseelan, J.D.; Srinivasan, M.K. Comparing the effects of different cleansing agents on the shear bond strength of resin cements on surface-contaminated zirconia: An in vitro study. Cureus 2025, 17, e78795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Isshi, K.; Kakura, K.; Ikeda, H.; Shimizu, H.; Kido, H.; Kawaguchi, T. Effects of ytterbium laser surface treatment on the bonding of two resin cements to zirconia. Dent. Mater. J. 2022, 41, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione, E.; Özcan, M. Adhesion of resin cements to contaminated zirconia resin cements on zirconia: Effect saliva-contamination and surface conditioning. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, R.S.T.; Ozkurt-Kayahan, Z.; Kazazoglu, E. In vitro evaluation of shear bond strength of three primer/resin cement systems to monolithic zirconia. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 32, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaiwan, W.; Chaijareenont, P. The effect of cleaning saliva-contaminated zirconia with various sodium hypochlorite concentrations on shear bond strength. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2024, 17, 3038–3043. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-H.; Son, J.-S.; Jeong, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, T.-Y. Efficacy of various cleaning solutions on saliva contaminated zirconia for improved resin bonding. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2015, 7, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Takagaki, T.; Wada, T.; Uo, M.; Nikaido, T.; Tagami, J. The effect of different cleaning agents on saliva contamination for bonding performance of zirconia ceramics. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noronha, M.D.S.; Fronza, B.M.; André, C.B.; de Castro, E.F.; Soto-Montero, J.; Price, R.B.; Giannini, M. Effect of zirconia decontamination protocols on bond strength and surface wettability. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 32, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pornatitanakul, V.; Klaisiri, A.; Sriamporn, T.; Swasdison, S.; Thamrongananskul, N. The Influence of Tooth Primer and Zirconia Cleaners on the Shear Bond Strength of Saliva-Contaminated Zirconia Bonded with Self-Adhesive Resin Cement. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, N.; Genc, O.; Akkese, I.B.; Malkoc, M.A.; Ozcan, M. Bonding effectiveness of saliva-contaminated monolithic zirconia ceramics using different decontamination protocols. Biomed. Res. Int. 2024, 2024, 6670159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukcheep, C.; Thammajaruk, P.; Guazzato, M. Investigating the impact of different cleaning techniques on bond strength between resin cement and zirconia and the resulting physical and chemical surface alterations. J. Prosthodont. Off. J. Am. Coll. Prosthodont. 2024; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Reddy, S.M.; Alva, H.; Shetty, J. Influence of cleaning solutions on shear bond strength of resin cement to saliva contaminated zirconia: An in-vitro study. RGUHS J. Med. Sci. 2022, 12, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, T.A.; Altak, A.; Abdulmajeed, A.; Rodgers, B.; Lawson, N. Cleaning zirconia surface prior to bonding: A comparative study of different methods and solutions. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Kocjan, A.; Lehmann, F.; Kosmac, T.; Kern, M. Influence of contamination on resin bonding to zirconia. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 553–559. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, R.; Tsujimoto, A.; Takamizawa, T.; Tsubota, K.; Suzuki, T.; Shimamura, Y.; Miyazaki, M. Influence of surface treatment of contaminated zirconia on surface free energy and resin cement bonding. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lümkemann, N.; Schönhoff, L.M.; Buser, R.; Stawarczyk, B. Effect of Cleaning Protocol on Bond Strength between Resin Composite Cement and Three Different CAD/CAM Materials. Materials 2020, 13, 4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf Shirazi, A.; Majidinia, S.; Parhizkar, T. Effect of Different Cleaning Methods on Bond Strength of Resin to Saliva-Contaminated Zirconia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of in Vitro Studies. Ann. Stomatol. 2024, 15, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charasseangpaisarn, T.; Wiwatwarrapan, C.; Siriwat, N.; Khochachan, P.; Mangkorn, P.; Yenthuam, P.; Thatphet, P. Different cleansing methods effect to bond strength of contaminated zirconia. J. Dent. Assoc. Thai. 2018, 68, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wahsh, M.; Taha, D.; Shaheen, O. Effect of surface contamination and cleansing methods on resin bond strength and failure modes of partially stabilized zirconia: An in vitro study. Int. J. Appl. Dent. Sci. 2024, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rus, F.; Rodríguez, C.; Salido, M.P.; Pradíes, G. Influence of different cleaning procedures on the shear bond strength of 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate-containing self-adhesive resin cement to saliva contaminated zirconia. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekçe, N.; Tuncer, S.; Demirci, M.; Kara, D. The effect of surface treatments on bond strength of resin cement to contaminated zirconia. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2018, 10, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, C.C.; Cesar, P.F.; Miranda, W.G.; Yoshimura, H.N. Bonding effectiveness of resin cements to contaminated and cleaned zirconia ceramic surfaces. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 687–694. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).