Abstract

Background/Objectives: Stability, retention, and support are removable partial denture (RPD) biomechanical principles. The literature shows contradictory opinions on indirect retention in RPDs, but no solid scientific evidence exists. This in vitro research aims to analyze indirect retainers’ (IRs) influence on forces transmitted to abutment teeth of a Kennedy Class I mandibular RPD. Methods: Bilateral distal-extension mandibular RPDs—differing only in the presence or absence of an IR on tooth 44 (IR model vs. nonIR model, respectively)—were installed on an acrylic master model. Tensile forces were applied perpendicularly to the occlusal plane on the longest free-end saddle’s distal aspect. Electronic speckle pattern interferometry (ESPI) measurements were obtained with and without an IR. The three-dimensional out-of-plane displacements of both models were acquired. Results: Abutment teeth 46 and 47 contralateral to the longest distal extension suffered more deformation under displacement forces when an IR was used. In turn, the IR’s influence on the deformation values of the abutment tooth 34 adjacent to the larger edentulous area depended on the intensity of the tensile force exerted: low-intensity forces resulted in reduced deformation, while higher-intensity forces resulted in higher deformation. Conclusions: This study’s findings indicate that indirect retention promotes better tensile force distribution in the existent teeth. However, they also question the IR’s role in protecting abutment teeth against excessive torque forces. This study’s preliminary results highlight the need for research on indirect retention principles using new methodologies, namely, in silico and ex vivo studies, and their experimental and clinical validation.

1. Introduction

Partial edentulism has been progressively reported in developed countries, probably due to the increased life expectancy and widespread access to oral healthcare highly focused on prevention and more conservative treatments [1,2,3]. Even though fixed dentures are an excellent solution for oral rehabilitation, they are often too expensive for lower socioeconomic classes [2,4,5]. Thus, removable partial dentures (RPDs) are still a valuable solution for conventional oral rehabilitation [6,7].

RPDs are a non-invasive treatment option capable of restoring oral functions and aesthetics, and they are more affordable than other solutions [5]. The patient’s satisfaction and acceptance clearly indicate RPD success [8,9], which, clinically, relies on precise diagnostic evaluation, treatment planning, and technical performance [7,10,11].

Biomechanics has been a cornerstone in the classical RPD design and manufacturing theories, namely regarding force support, stability, distribution, and retention [7,12,13]. Nonetheless, most theories lack scientific evidence [5,6]. Increasing importance has been given to appropriate plaque control, which used to be considered a secondary prophylactic issue [7,14]. Accordingly, numerous studies have focused on simplified and open frameworks, limiting components to essential elements while minimizing denture coverage [7,15]. Despite the specificities of each clinical case, all RPDs are composed of key elements that collectively aim to: (i) provide support through both rest seats on abutment teeth and well-adapted bases over the alveolar ridges of edentulous areas; (ii) ensure direct retention via direct retainers; (iii) maintain stability through bracing components and properly adapted denture bases; and (iv) promote the selective and favorable transmission of forces by incorporating rigid components into the RPD framework. The principal components include the major connector, minor connectors, bases, rest seats, and both direct and indirect retainers (IRs) [12].

Free-end saddle dentures, particularly the mandibular ones, are associated with static and dynamic issues that greatly challenge the RPD framework design. Among the several factors that should be considered are the differing resiliencies of the oral mucosa and teeth, which leads to distinct viscoelastic outcomes under occlusal loading, and the apparent denture rotation under lifting forces (e.g., chewy food, gravity force on the maxillary prosthesis, or functional forces) [16]. Research has proposed indirect retention to help solve some of these issues [12,13,17]. The indirect retention principle can be explained by a Class 2 lever system, where the direct retainer clasp’s retentive arm acts as the resistance, situated between the fulcrum—represented by the IR set on a tooth—and the power, corresponding to any occlusal load [18]. In order to minimize the displacement force and increase the retentive arm’s length, the fulcrum line (or clasp axis) should be near the saddle, while the IR should be positioned as far as possible from the denture base [19].

The literature states that IRs are used mainly to oppose distal extensions’ rotational displacement on a fulcrum axis [18] and can increase stability against horizontal forces, reduce the anteroposterior lever action on abutment teeth, offer additional guiding surfaces, and contribute to stress distribution [13]. Despite these benefits, the clinical relevance of indirect retention has been questioned in the literature based on different arguments. Firstly, the fulcrum line concept implies that the two other posterior direct retainers are not displaced during function. However, although previous research suggested that “during normal function distal extension dentures do not always rotate around the supporting rests when occlusally loaded” [13], further study is still required. Secondly, IRs’ effectiveness in preventing distal base dislodgements under masticatory forces is still unclear, and distal-extension movements have been observed in the presence of indirect retainers [20,21]. Thirdly, experimental assessment is required to verify the rationale that indirect retention prevents the transmission of torque forces to abutment teeth. According to Berg, periodontium’s physiological tolerance to those stimuli is unpredictable [22]. Fourthly, IRs’ potentially harmful side effects on abutment teeth, namely any dental movements and impact on supporting tissues, must be considered [23]. Fifthly, IRs promote the risk of gingival inflammation and radicular caries by creating more complex and less “hygienic” frameworks [7,15].

The electronic speckle pattern interferometry (ESPI) technique has been widely used to measure in-plane and out-of-plane displacements of objects under loading by analyzing laser speckle interference patterns, from which deformations can also be derived. Its contactless and non-destructive nature allows several measurements on the same sample. These characteristics, along with its high displacement resolution (approximately 0.1 μm), make ESPI a valuable experimental tool for applications in Dentistry [24,25].

The present work aims to investigate the forces transmitted to abutment teeth of direct and indirect retainers in RPDs, with and without indirect retention, by using an ESPI setup and an experimental mandibular model of a Kennedy Class I RPD. The null hypothesis (H0) is as follows: the presence of an indirect retainer does not influence the forces transmitted to abutment teeth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mandibular Model

A plastic master model (Frasaco, Tettnang, Germany) was employed to simulate the mandibular arch. Based on a specific clinical case, teeth 35, 36, 37, 38, and 48 were removed, and a thin layer of putty silicone (Virtual Fast Set, Ivoclar Vivadent, NY, USA) was applied to the corresponding areas (Figure 1A). Occlusal rests were prepared spoon shaped in teeth 34 (mesial), 46 (distal), and 47 (mesial) based on the Principles, Concepts, and Practices in Prosthodontics (1994) guidelines [12]. A rest seat was prepared on the mesial marginal ridge of tooth 44 to support the IR when applicable (Figure 1B,C). All teeth were shaped using a high-speed handpiece with 016 and 018 round diamond burs. An alginate-loaded standard impression tray was used to duplicate the model, and the stone cast was obtained immediately (Figure 2A–C).

Figure 1.

Acrylic mandibular model. (A) Teeth 35–38 and 48 were extracted, followed by application of putty addition silicone (occlusal view). (B,C) Detailed views of the rest seats prepared on the occlusal surfaces of teeth 34 (mesial), 44 (mesial), 46 (distal), and 47 (mesial).

Figure 2.

Cast duplication of models. (A) Mandibular impression with alginate. (B,C) Working model in occlusal and frontal views, respectively).

2.2. Mandibular RPDs

A Kennedy Class I RPD was fabricated using a cobalt-chromium framework combined with acrylic resin. The prosthesis was composed of a lingual bar as major connector, as direct retainers a double Akers clasp on teeth 46 and 47 and a clasp with posterior action on tooth 34, three occlusal rests for direct retainers on abutment teeth 46 (distal), 47 (mesial) and 34 (mesial), an IR on tooth 44, and artificial teeth at positions 35, 36, 37, and 48. This RPD was named ‘IR model’. To minimize potential confusion variables, the indirect retainer on tooth 44 was removed from the framework, and the RPD obtained was named ‘noIR model’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

RPDs positioned on the plastic mandibular model. (A,B) IR model: occlusal views from posterior to anterior and anterior to posterior, respectively, of the RPD with an indirect retainer on tooth 44. (C,D) noIR model: occlusal views, from posterior to anterior and anterior to posterior, respectively, of the RPD without an indirect retainer.

2.3. ESPI Model System

An ESPI setup was developed to assess the displacement pattern caused by loading on abutment teeth of RPDs with and without indirect retention. ESPI directly measures displacements, from which deformations can be derived by differentiating the displacement fields. In this study, the term “deformation” refers to the geometric changes of the abutment teeth under loading.

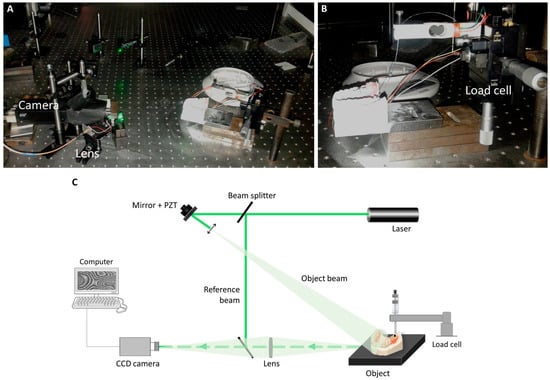

After mandibular model immobilization, tensile forces ranging from 0.15 to 0.70 N were directed perpendicular to the alveolar ridge on the distal side of the longest free-end saddle (third quadrant). A bending beam load cell and a micrometer screw (not shown in the photograph of Figure 4) were used to apply loads with controlled direction and magnitude. Figure 4 illustrates the ESPI setup used for measuring the out-of-plane displacement field. Basically, a Coherent Verdi 532 nm laser beam (2 W) was divided into two equal-intensity beams: reference beam and object beam. The interference between the two wavefronts creates interferometric fringes, forming a holographic record that encodes both the amplitude and the phase of the wavefront originating from the object. Thus, the comparison between the initial state (unloaded) and the final state (under load) creates a pattern of fringes corresponding to the displacement isocurves. The phase maps indicated for data post-processing can be calculated using an appropriate algorithm and a phase shift element [mirror + piezoelectric device (PZT)]. These phase maps allow evaluation of the displacement field based on the setup geometry and the wavelength of the laser.

Figure 4.

Measurement of surface displacements using the experimental ESPI setup (out-of-plane displacement field). (A) Overall experimental setup. (B) Detailed view depicting the point where the tensile force was applied on the RPD. (C) Schematic diagram of experimental setup. PZT—Piezoelectric device. CCD—Charge-coupled device.

Reproducibility of the applied tensile forces was confirmed through three repeated measurements, after which one single measurement was obtained for each experimental condition. The assays were first conducted on the IR model, and upon removal of the indirect retainer from the RPD, experiments were performed for the noIR model.

3. Results

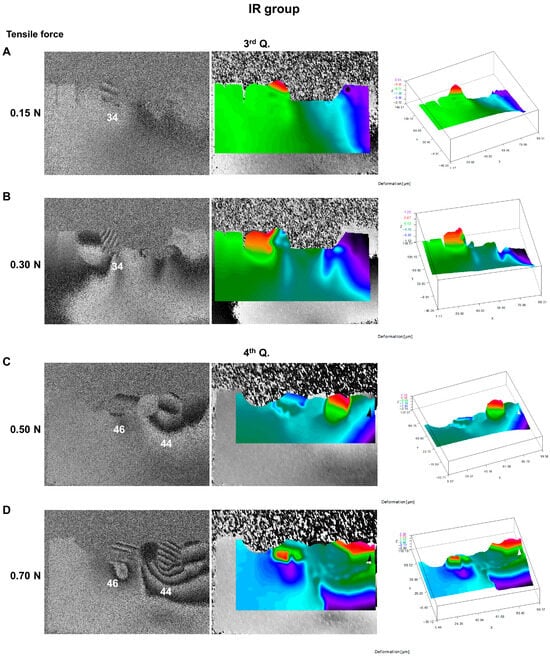

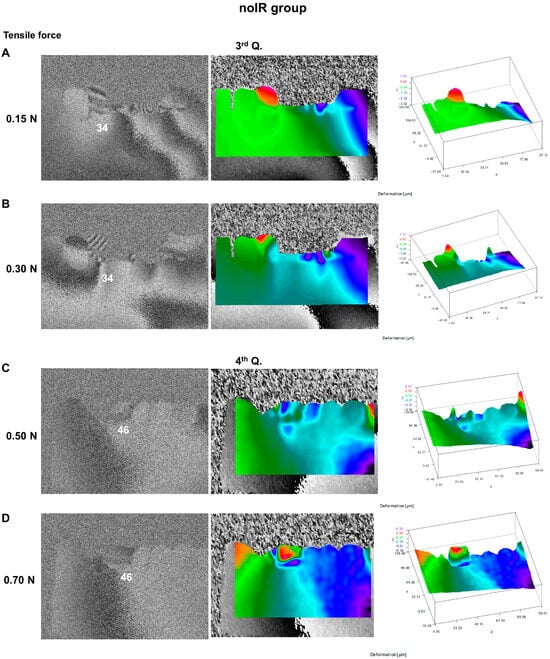

The third and fourth quadrants were recorded independently because interferometric measurements require illuminating the test object’s surface with laser light. Figure 5 and Figure 6 summarize the out-of-plane displacements observed for each experimental model and condition. The areas highlighted in red, along with increased black and gray fringes, indicate high-magnitude deformations. The maximum tensile force on the longest free-end saddle was 0.70 N, as measurements above this value could not be obtained. This limitation likely results from the high sensitivity of the ESPI method, which makes the fringe pattern unresolvable when displacements are too large.

Figure 5.

ESPI assessment of the IR model following tensile loading on the distal extension saddle (out-of-plane displacement field). Left panel: raw fringe pattern (interferograms) with the tooth identification; middle panel: color-coded filtered map, with red denoting maximum displacement and blue denoting minimum; right panel: 3D displacement chart. (A,B) Third quadrant recordings (3rd Q.). (C,D) Fourth quadrant recordings (4th Q.).

Figure 6.

ESPI assessment of the noIR model following tensile loading on the distal extension saddle (out-of-plane displacement field). Left panel: raw fringe pattern (interferograms) with the tooth identification; middle panel: color-coded filtered map, with red denoting maximum displacement and blue denoting minimum; right panel: 3D displacement chart. (A,B) Third quadrant recordings (3rd Q.). (C,D) Fourth quadrant recordings (4th Q.).

Regarding the third quadrant, high-quality speckle interferograms of tooth 34 were achievable only at lower tensile forces of 0.15 and 0.30 N. Above these values, the ESPI measurement interval was surpassed. The 0.15 and 0.30 N tested forces generated dark and bright fringes around tooth 34 with different direction patterns (Figure 5A compared with 5B and Figure 6A compared with 6B). Abutment tooth 34 exhibited greater resistance to deformation under low-magnitude tensile forces (0.15 N) in the IR model (Figure 5A compared with Figure 6A). In turn, under higher-intensity forces, greater deformation was observed near teeth 34 and 33 in the IR model (Figure 5B compared with Figure 6B).

In the fourth quadrant, displacements associated with tooth 46 (contralateral abutment tooth supporting a direct retainer of the longest free-end saddle) and its surrounding area increased with higher tensile loading in both the IR (Figure 5C,D) and the noIR (Figure 6C,D) models. However, that tooth suffered considerably less displacement in the noIR model compared to the IR model (Figure 6C compared with Figure 5C and Figure 6D compared with Figure 5D). As expected, in the IR model, tooth 44, supporting the indirect retainer, suffered the most deformation events in the tensile tests.

4. Discussion

The scientific literature argues that fixed dentures, whether tooth- or implant-supported, provide superior oral comfort [5,26,27]; however, their invasiveness and higher costs often limit their use [6,28]. Conventional removable dentures remain a commonly employed alternative to restore edentulous areas [7,29,30]. Despite this, limited contemporary research has focused on RPD over the past decades, and much of the knowledge has relied primarily on empiric and subjective clinical experience instead of standardized methodologies. Therefore, many classical RPD design and manufacturing concepts lack scientific evidence [6,15].

Traditionally, the three main biomechanical principles guiding RPD design are support, retention, and stability. Besides these mechanical features, hygienic principles are also fundamental [15]. Jacobson [31] argued that RPDs should have open, simple frameworks that minimally cover soft and hard oral tissues, since redundant structural components may hinder plaque control and increase the impact on the periodontium [15]. Covering the gingival margin is particularly detrimental, as it promotes increased crevicular temperature, plaque accumulation, gingival inflammation, higher probing depth [32,33,34], and root caries [5,35,36]. Therefore, the scientifically supported incorporation of components such as IRs into RPD frameworks is crucial, along with a critical reassessment of classical concepts in RPD design.

Indirect retention’s use in RPDs is still controversial, and its benefits and disadvantages must be considered in each case. Davenport et al. [19] surveyed prosthodontists on whether IRs were required in distal-extension RPDs and obtained the same percentage of agreement and disagreement. Previously, Frank and Nicholls [37], using a bilateral distal-extension mandibular RPD as a model, found that the IR had little influence on displacement forces.

Usually, an IR is composed of a rest connected to the major connector via a minor connector [18]. This design covers a large surface area and extends across the cervical gingiva, thus contributing to the mentioned drawbacks [5,15,31,32,33].

IRs are indicated to limit the displacement of free-end saddles, but they also must reduce the anteroposterior leverage and the torque forces on the main abutment teeth [13]. In 1985, Berg’s review [22] questioned the traditional assumptions regarding periodontal tissues’ reactions to RPDs. It argued that more research was required on the hypothesis that torque stresses surpass the periodontium’s physiological limits [22]. In turn, Bergman et al. [20] indicated that the periodontal degeneration and loosening of abutment teeth commonly observed in RPD users are more likely related to suboptimal oral hygiene and plaque accumulation than to the direct forces transmitted by the RPD framework. Other authors supported these groundbreaking rationales [20,32,34,38].

There is no scientific data demonstrating that torque forces applied to abutment teeth of distal-extension RPDs can be the direct cause of periodontal status impairment or greater tooth mobility, provided that the three following criteria are satisfied: well-adjusted denture saddle, strict plaque control, and favorable bone support [22,34,38]. However, the coexistence of these three criteria is rare. Thus, it is still unclear whether using IRs to neutralize torque forces is reasonable. The present study analyzed this issue from a biomechanical perspective using a holographic approach. The RPD framework analyzed followed a non-standard design (not ending in the second molar bilaterally) based on a specific clinical case in which tooth 48 was included to maintain right-side occlusal contacts and support mastication, while tooth 38 was omitted due to the absence of a corresponding antagonist. This relatively common clinical scenario was chosen to assess the impact of such asymmetric designs on prosthesis performance, specifically regarding indirect retention.

The forces applied in this study, ranging from 0.15 to 0.70 N, were chosen to optimize the performance of ESPI measurements rather than to replicate functional forces observed in vivo. Because ESPI is a high-resolution technique, the effects of higher forces cannot be assessed in a single measurement. Preliminary assays were therefore conducted to determine the maximum tensile force that could be applied in incremental load steps without compromising measurement accuracy. These tests indicated that forces above 0.70 N generated displacements of such magnitude that reliable ESPI recordings could no longer be obtained.

The results of the current work show that the intensity of the tensile force applied influenced the magnitude of deformation in the abutment tooth adjacent to the longest edentulous ridge in both RPDs with and without an IR. When low-intensity displacement forces capable of triggering the direct retainer clasp’s retentive function are exerted, the IR serves as an additional fulcrum, alleviating the forces transmitted to the main abutment. Conversely, higher tensile forces likely surpass the clasp’s resistance to deformation. When no indirect retention exists, the only RPD rotation points are the direct retainers’ retentive portions. Thus, as the tooth undergoes occlusal rotation, retainers may become displaced, causing less deformation of the associated abutment.

The higher deformation observed on the contralateral abutment tooth of the longest free-end saddle in the IR model supports the idea that indirect retainers aid in distributing stress [13]. It should also be considered that the different behavior of the abutment teeth (34 and 46) under low-intensity tensile forces may have been influenced, at least in part, by the distinct clasp designs employed in the distal abutments. Moreover, our study’s results emphasize the influence of displacement forces on the tooth that supports the IR. Accordingly, as suggested by previous studies, the associated long-term advantages and disadvantages must be thoroughly investigated [15].

The present study has some limitations. Even though the holographic assessments provided valuable qualitative information, they do not allow for a direct correlation between in vivo and in vitro results, representing a constraint. The use of a standardized plastic model does not realistically replicate clinical conditions, as it does not resemble the typical anatomy of an edentulous alveolar ridge, which is characterized by bone resorption and remodeling following tooth extraction. In addition, this model fails to simulate the resilience provided both by the alveolar mucosa and the periodontal ligament of the abutment teeth. Alternatively, this study could have employed dried human jaws instead of an acrylic-based mandibular arch, which might have yielded more accurate ESPI results [39]. However, the intrinsic anatomical diversity of natural specimens could introduce certain confounding variables susceptible to compromising result interpretation, as different loading responses would not be directly attributable to indirect retention. Despite these limitations, the standardized acrylic-based model ensured experimental consistency and reproducibility, allowing for qualitative meaningful comparisons within the scope of this research. The ESPI setup used in the present study assessed only the effects of tensile forces perpendicular to the alveolar ridge, which are most directly related to the potential need for IRs. Using the same approach, it would also be valuable to examine the responses to left/right forces, simulating the lateral and oblique loads typically applied to RPDs during mastication and other functional movements. Given the high sensitivity of the method, the applied loads should be of reduced magnitude, necessitating the construction of a dedicated loading apparatus to ensure precise control of the loading directions. This aspect should be explored in future research. The post-processing of ESPI results also created some inconsistency (i.e., gray and black images vs. color images). Furthermore, the information about the tooth surface under the RPD clasps could not be precisely integrated into the algorithm because clasps showed considerable mobility. Nonetheless, the raw data analysis provided a reasonably satisfactory qualitative assessment of the results. Future research could adopt a non-contact optical approach based on digital image correlation to overcome the practical restrictions posed by great displacements in ESPI experiments [40].

In vivo corroboration of the ESPI findings could help surpass some of the mentioned limitations and contribute notably to the researched issue. Maxfield et al. [41] designed an intraoral strain-gauge device to investigate the impact of occlusal rest positioning and the saddle of a bilateral free-end RPD on the loads transferred to abutment teeth. Subsequently, Kawata et al. [42] used a 3D-force measuring system with a piezoelectric transducer for the same purpose. This methodology could also be applied to evaluate the role and efficiency of indirect retention during mastication with different food textures (namely, hard vs. chewy).

Complementing ESPI fringe data with finite element analysis could provide valuable insights [43,44] concerning: (i) the direction and intensity of loads transmitted to abutment teeth supporting direct and indirect retainers, (ii) the extent of distal-extension movements related to tensile force application on different points, and (iii) the effectiveness of IRs in limiting occlusal displacement of free-end saddles.

The inclusion of each RPD framework component must be carefully considered, as each represents a potential area for biofilm accumulation and may interfere with the natural self-cleaning function of the tongue and oral mucosa. Therefore, RPD’s gold standard should include tailored framework designs that consider oral hygiene, periodontal conditions, and the patient’s expectations. If the inclusion of an IR poses more risks than assumed advantages, alternative strategies must be considered for occlusal force resistance, namely, maximizing base extension, adequate adaption to the residual alveolar ridge, altered-cast impression technique, occlusion optimization, and reducing the occlusal table area [19].

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study highlight the importance of assessing the forces exerted on the abutment tooth for the IR and incorporating this consideration into design and fabrication of a RPD framework. The results reject our null hypothesis (H0), as they indicate that the intensity of the displacement force influences the IR’s ability to minimize torque forces in abutment teeth. In turn, they support the evidence-based view that IRs enhance stress distribution across the arch. The results also suggest that, beyond certain limits, indirect retainers might not serve the purpose of protecting the abutment tooth against undesired deformation, and their need should be assessed on a case-specific basis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.O. and M.H.F.; methodology, M.A.P.V. and M.S.-F. (Manuel Sampaio-Fernandes); formal analysis, M.A.P.V.; investigation, S.J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.O.; writing—review and editing, M.S.-F. (Margarida Sampaio-Fernandes) and M.H.F.; supervision, J.C.R.-C. and M.H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jaime Monteiro for his help with the ESPI experiments and Américo Ribeiro for providing the removable partial denture used in the experimental work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RPD | Removable partial denture |

| ESPI | Electronic speckle pattern interferometry |

| IR | Indirect retainer |

| PZT | Piezoelectric device |

References

- Fuller, E.; Steele, J.; Watt, R.; Nuttall, N. Oral Health and Function—A Report from the Adult Dental Health Survey 2009; The Health and Social Care Information Centre: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, C.W.; Watson, A.J. Future needs for fixed and removable partial dentures in the United States. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2002, 87, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.; Brito, L.D.M.; Piyasena, P.; Petrauskiene, E.; Congdon, N.; Tsakos, G.; Virgili, G.; Mathur, M.; Woodside, J.V.; Leles, C.; et al. Impact of edentulism on community-dwelling adults in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e085479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, T.A.; Gilbert, G.H.; Duncan, R.P.; Foerster, U. Risk indicators of edentulism, partial tooth loss and prosthetic status among black and white middle-aged and older adults. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2001, 29, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöstmann, B.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Jepson, N.; Mushimoto, E.; Palmqvist, S.; Sofou, A.; Öwal, B. Indications for removable partial dentures: A literature review. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2005, 18, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waliszewski, M.P. Turning points in removable partial denture philosophy. J. Prosthodont. 2010, 19, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, T.; Waia, S. Removable Partial Dentures for Older Adults. Prim. Dent. J. 2020, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozhayat, E.B.; Gotfredsen, K. Effect of treatment with fixed and removable dental prostheses: An oral health-related quality of life study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2012, 39, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kok, I.J.; Cooper, L.F.; Guckes, A.D.; McGraw, K.; Wright, R.F.; Barrero, C.J.; Bak, S.; Stoner, L.O. Factors Influencing Removable Partial Denture Patient-Reported Outcomes of Quality of Life and Satisfaction: A Systematic Review. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakestam, U.; Karlsson, T.; Soderfeldt, B.; Ryden, O.; Glantz, P.O. Does the quality of advanced prosthetic dentistry determine patient satisfaction? Acta Odontol. Scand. 1997, 55, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.P.; Brudvik, J.S.; Leroux, B.; Milgrom, P.; Hawkins, N. Relationship between the standards of removable partial denture construction, clinical acceptability, and patient satisfaction. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 83, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principles, concepts, and practices in prosthodontics—1994. Academy of Prosthodontics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1995, 73, 73–94. [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.B.; Brown, D.T. McCracken’s Removable Partial Prosthodontics, 12th ed.; Elsevier Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2011; pp. 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Marxkors, R. The Partial Denture with Metal Framework; BEGO, Bremer Goldschlägarei Wilhelm Herbst: Bremen, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Owall, B.; Budtz-Jörgensen, E.; Davenport, J.; Mushimoto, E.; Palmqvist, S.; Renner, R.; Sofou, A.; Wöstmann, B. Removable partial denture design: A need to focus on hygienic principles? Int. J. Prosthodont. 2002, 15, 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Maria, M.T.S.; Marito, P.; Salazar, S.; Hori, K.; Ono, T. Effect of mandibular bilateral distal extension denture design on masticatory performance. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2023, 67, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummer, W. Partial denture service. In The American Textbook of Prosthetic Dentistry; Anthony, L.P., Ed.; Lea & Feibiger: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1942; pp. 782–783. [Google Scholar]

- Avant, W.E. Indirect retention in partial denture design. 1996. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 90, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J.C.; Basker, R.M.; Heath, J.R.; Ralph, J.P.; Glantz, P.O.; Hammond, P. Indirect retention. Br. Dent. J. 2001, 190, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, B.; Hugoson, A.; Olsson, C.O. Caries, periodontal and prosthetic findings in patients with removable partial dentures: A ten-year longitudinal study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1982, 48, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegard, B.; Lundberg, M.; Wictorin, L. Denture mobility during chewing; a study method. Swed. Dent. J. 1966, 59, 403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, E. Periodontal problems associated with use of distal extension removable partial dentures-a matter of construction? J. Oral Rehabil. 1985, 12, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marxkors, R. Mastering the removable partial denture—Part one: Basic reflections about construction. J. Dent. Technol. 1997, 14, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, L.M.P.; Parra, D.F.; Vasconcelos, M.R.; Vaz, M.; Monteiro, J. DH and ESPI laser interferometry applied to the restoration shrinkage assessment. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2014, 94, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.C.; Correia, A.; Vaz, M.A.; Branco, F.J. Holographic stress analysis in a distal extension removable partial denture. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2009, 17, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Swelem, A.A.; Abdelnabi, M.H. Attachment-retained removable prostheses: Patient satisfaction and quality of life assessment. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiaky, O.N.; Lokossou, D.L.; Soueidan, A.; Le Bars, P.; Gueye, M.; Mbodj, E.B.; Le Guéhennec, L. Implant-supported removable partial dentures compared to conventional dentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life, patient satisfaction, and biomechanical complications. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, C.; Hobkirk, J.; DDios, P. Dental endosseous implants in the medically compromised patient. J. Oral Rehabil. 2007, 34, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, P.C. Appropriatech: Prosthodontics for the many, not just for the few. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2004, 17, 261–262. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, G.E. Some issues related to evidence-based implantology. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2016, 16, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T.E. Periodontal considerations in removable partial denture design. Compendium 1987, 8, 530–534. [Google Scholar]

- Runov, J.; Kroone, H.; Stoltze, K.; Maeda, T.; El Ghamrawy, E.; Brill, N. Host response to two different designs of minor connector. J. Oral Rehabil. 1980, 7, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlataric, D.K.; Celebic, A.; Valentic-Peruzovic, M. The effect of removable partial dentures on periodontal health of abutment and non-abutment teeth. J. Periodontol. 2002, 73, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonte Porto Carreiro, A.; de Carvalho Dias, K.; Correia Lopes, A.L.; Bastos Machado Resende, C.M.; Luz de Aquino Martins, A.R. Periodontal Conditions of Abutments and Non-Abutments in Removable Partial Dentures over 7 Years of Use. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, N.J.; Moynihan, P.J.; Kelly, P.J.; Watson, G.W.; Thomason, J.M. Caries incidence following restoration of shortened lower dental arches in a randomized controlled trial. Br. Dent. J. 2001, 191, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.R.; Zhang, C.Z.; Gong, M.L.; Cheng, X.Q.; Wu, H.K. Development of a nomogram for root caries risk assessment in a Chinese elderly population. J. Dent. 2025, 156, 105624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.P.; Nicholls, J.I. An investigation of the effectiveness of indirect retainers. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1977, 38, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, B.A.; Barreto, A.O.; Gomes Seabra, E.; Roncalli, A.G.; da Fonte Porto Carreiro, A.; de Almeida, E.O. A clinical follow-up study of the periodontal conditions of RPD abutment and non-abutment teeth. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, T.N.; Adachi, L.K.; Chorres, J.E.; Campos, A.C.; Muramatsu, M.; Gioso, M.A. Holographic interferometry method for assessment of static load stress distribution in dog mandible. Braz. Dent. J. 2006, 17, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasic, I.; Milic-Lemic, A.; Tihacek-Sojic, L.; Stancic, I.; Mitrovic, N. Analysis of the compressive strain below the removable and fixed prosthesis in the posterior mandible using a digital image correlation method. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2012, 11, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxfield, J.B.; Nicholls, J.I.; Smith, D.E. The measurement of forces transmitted to abutment teeth of removable partial dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1979, 41, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, T.; Kawaguchi, T.; Yoda, N.; Ogawa, T.; Kuriyagawa, T.; Sasaki, K. Effects of a removable partial denture and its rest location on the forces exerted on an abutment tooth in vivo. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2008, 21, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, S. Finite element analysis: A boon to dentistry. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2014, 4, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoud, P.; Faghihian, H.; Richert, R.; Jacobs, R.; EzEldeen, M. Finite element models: A road to in-silico modeling in the age of personalized dentistry. J. Dent. 2024, 150, 105348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).