Abstract

Electronic and spin structures of open-shell molecules and clusters were investigated as possible building blocks for the construction of one- and two-dimensional quantum spin alignment systems which exhibited several characteristic quantum properties of strongly correlated electron systems: high-Tc superconductivity, quantum spin coherence, entanglement, etc. Ab initio calculations were performed to elucidate effective exchange integrals (J) for 3d transition metal oxides, providing the J-model for high-Tc superconductivity. Theoretical investigations such as Monte Carlo simulation, molecular mechanics and quantum mechanical calculations were performed to elucidate effective chemical procedures for through-bond alignments of open-shell transition metal ions by organometallic conjugation and through-space confinements of molecular spins such as molecular oxygen by molecular confinement materials. Theoretical simulations have elucidated the importance of appropriate confinement materials for alignments of molecular spins desired for quantum coherence and quantum sensing. Equivalent transformations among coherent states of superconductors, trapped ion, neutral atom, molecular spin, molecular exciton, etc., are also discussed on theoretical and conceptual grounds such as quantum entanglement and decoherence.

1. Introduction

The first evolution of quantum mechanics emerged approximately 100 years ago. It has permeated many disciplines such as quantum chemistry, quantum electronics, quantum optics, etc. Predictions of quantum mechanics have been verified experimentally to an extremely high degree of accuracy in these fields. Quantum theory has been extended to several fields such as (1) nuclear physics and elementary particle physics, (2) applications to quantum spectroscopies and devices and (3) thought experiments for characterizations of quantum mechanics. However, fundamental concepts such as quantum coherence in mesoscopic systems, Bell inequality relating to the Einstein–Podorsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox, quantum entanglement, etc. in the third direction lack reliable experimental investigations. In the 1960s, light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation (laser) was invented to provide high-intensity light with coherence, directionality and monochromaticity. Therefore, invention of the laser has opened the door for non-linear optics, quantum optics and quantum information science related to future optical quantum devices.

In the 1980s, fifty years after the establishment of quantum mechanics [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], new quantum mechanical phenomena were discovered in the field of quantum science and quantum engineering, opening the door for the second evolution of quantum mechanics. Some of such new findings are, for example, (i) discovery of macroscopic quantum tunneling for electron transport [13], (ii) discovery of quantum effects for Hall conductivity [14,15,16], (iii) proposal of the Haldane conjecture [17] for one-dimensional spin chains and related proposals for 2D systems [18], (iv) discovery of high-Tc superconductivity of copper oxides [19], (v) demonstration [20] of the violation of Bell’s inequalities [21] with photons in relation to the EPR paradox [22], (vi) proposal of quantum computation [23,24], etc. A laser was used to obtain experimental answers to fundamental questions by the EPR [22] and Bell inequality of (v). Quantum computation (vi) is currently implemented on superconducting platforms operating in the mesoscopic regime. This entails current interests in the design and synthesis of molecular quantum materials in chemistry.

Quantum magnetism (iii) and high-Tc superconductivity (iv) were our primary interests among the above discoveries for several reasons. Historically, the discoveries of high-Tc superconductivity [19] (iv) opened the door for extensive investigations of strongly correlated electron systems (SCESs) [25,26] in solid-state physics and chemistry. Neutron diffraction experiments [27] have elucidated the antiferromagnetism of copper oxide solids before hole doping, indicating an SCES instead of metal predicted by the ordinary band model [26]. A new discovery [19] revealed a close relationship between magnetism and high-Tc superconductivity. Therefore, ab initio calculations have been performed to elucidate sign and magnitude of effective exchange integrals (J) for transition metal oxide clusters for the bottom-up bond to band approach to SCESs in quantum chemistry [28,29]. Thus, molecular magnetic materials have attracted great interest in the field of material science and engineering.

The origin of high-Tc superconductivity was ascribed to a specific quantum property of the hole-doped CuO2 plane of the three-dimensional (3D) Ln2CuO4 solid [26] which exhibited antiferromagnetism before hole doping, namely one type of SCES as mentioned above [26,27,28,29]. Equivalent transformation from the CuO2 plane to isolobal–isospin planes was a guiding principle for the design of new materials [30]. After this discovery [19], electronic and magnetic properties of low-dimensional (LD) systems have indeed attracted great interest to elucidate possible mechanisms of high-Tc superconductivity and related exotic phases [26,29,30,31,32]. We have been interested in theoretical investigation of organic and inorganic systems which are isolobal and isospin for LD (2D) CuO2 planes [30]. To this end, Hubbard model involving the electron repulsion term (G) for SCESs was employed for coordination systems between first-row transition metal (Cu, Ni, Co, Fe, etc.) 3d-electron complexes and organic molecules with p-electrons, namely d-p conjugated systems [30,33]. The spin Hamiltonian model was also introduced to calculate effective exchange integrals (J), providing a J-model for superconductivity which enabled us to predict possible superconductivity even for Ni and Fe complexes [28,33]. The superconductivity of Ni oxide proposed by the J-model [28,33] was discovered after thirty years [34,35]. High-Tc superconductivity has been realized in the 3d transition metal oxides and arsenide. However, the detailed mechanisms of the high-Tc superconductivity [19] and related exotic phases are still under debate.

Over the past decades, mesoscopic systems between microscopic and macroscopic materials [13,14,15,16,17,18] have attracted great interest in material science and chemistry. A fundamental theory [36] has been presented for quantum tunneling of mesoscopic systems. In the 1990s, zero- and low-dimensional molecular systems attracted great interest in relation to quantum effects such as quantum coherence for molecular spin systems constructed by organometallic conjugation (OMC) procedures [30,37,38,39]. The quantum spin tunneling of transition metal clusters such as Mn oxide clusters was extensively investigated in relation to quantum coherence and decoherence of molecular spins [40].

We performed the specially promoted project on OMC from 1994–1996 to develop spin systems for future molecular quantum devices [38,39]. In the late 1990s, we performed the DFT and CASSCF computations of the J-values for dimers and linear clusters of Cr atoms as an example of quantum tunneling in linear antiferromagnetic clusters [41]. The J-values for Mn oxide clusters and Fe–sulfur complexes were also obtained to examine the possibility of quantum tunneling of zero-dimensional clusters [42,43]. Through-bond alignments of open-shell transition metal ions by OMC have been performed experimentally to realize coherent states for quantum material science and engineering [44]. On the other hand, the J-values for Prussian blue analogs [45] were calculated to estimate photo-induced magnetic transition temperatures in their three-dimensional (3D) crystals. In the 2000s, many transition metal coordination compounds were synthesized and characterized for implementation of quantum phenomena [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

On the other hand, alignments of organic open-shell systems were hardly realized because of lack of molecular confinement materials (MCMs) for suppression of radical reactions. Through-space alignments of open-shell species have been investigated by several molecular materials such as carbon nanotubes, graphene, DNA, etc. [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. The hexagonal carbon lattices of the nanotubes and graphene were indeed found to be useful for adsorption of molecules. DNA wire and sheets [49] were also examined to obtain one-dimensional (1D) alignment of organic radicals. However, these materials are too flexible for rigid alignments of open-shell molecules. Therefore, we must search for more rigid MCMs for well-organized alignments of open-shell molecules.

The two-dimensional (2D) square-planar lattice of Cu(II) complexes [38,39] was used to confine radicals in our OMC project [59,60]. However, a clear-cut X-ray structure was not obtained for them at that time. In 1995, the Yaghi group synthesized a similar Zn(II)–organic framework (MOF) which exhibited adsorption ability of Ar, Xe, CO2, etc. [61,62] as expected on theoretical grounds [39]. Therefore, we immediately performed theoretical simulations [63] to elucidate possible spin alignments of triplet molecular oxygen (O2, S = 1) in early Zn-MOFs [62], elucidating the quasi-1D alignment relating to the Haldane conjecture [17]. Thus, early theoretical simulations [39,63] elucidated the utility of MOFs for the confinement of open-shell molecules. MOFs [61,62] have been used for molecular confinement materials (MCMs) like nanotubes, graphene, DNA wires, etc. for open-shell systems such as nitroxide radical clusters, etc.

A number of organometallic materials have been developed in recent years [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78], indicating their utility for environmental applications such as CO2 and H2 adsorptions. Medical applications of MOFs such as drug delivery are also investigated extensively. We are interested in the practical utility of organometallic conjugation (OMC) [59,60], MOFs [61,62], porous coordination polymer (PCP) [68,69], sponge materials (SpoM) [66,67], etc., which are regarded as effective molecular confinement materials (MCMs). These materials are indeed useful for through-space confinement and alignment of open-shell molecules for the realization of quantum coherence in quantum information processing such as quantum sensing and quantum computing [78]. On the other hand, electronic, magnetic and optical (laser) fields have been used for physical alignment and confinement of open-shell atoms and ions for the generation of their coherent states [78], providing fundamental information for quantum sciences.

In this review, we have mainly summarized our early theoretical efforts in spin science and chemistry based on the guiding principle of organometallic conjugation (OMC) [37,38,39,43,44,45,46,47,49,78]. Theoretical calculations of the J-values for SCESs are first reviewed in relation to the J-model for superconductivity. Theoretical backgrounds for the J-model are also briefly reviewed. Confinements of open-shell systems by MCMs such as OMC [38,39], MOFs [61,62], PCP [68,69], SpoM [66,67], etc. are also reviewed in relation to Monte Carlo simulation of adsorption. Future prospects using MCMs are discussed from our theoretical point of view: through-bond and through-space alignments of molecular spins for quantum information science [78]. Through-physical (e.g., electronic, magnetic and/or optical field) alignments of neutral and ionic atoms are also reviewed briefly to obtain systematic understanding of quantum coherence and quantum entanglement of mesoscopic systems. A time-dependent master equation is revisited in relation to dynamical decoupling of decoherence in both physical and molecular quantum systems. Implications of these theoretical results are also discussed in relation to quantum biology such as light harvesting [78].

2. Theoretical Backgrounds

2.1. Quantum Chemistry of Open-Shell Molecules

First of all, quantum chemical models for chemical bonds are revisited to understand local spins in molecules. Valence bond (VB) [10,12] and molecular orbital (MO) [79,80,81] methods have been developed for quantum mechanical description of chemical bonds of molecules. Both theoretical models have elucidated the importance of electron correlation effects since correct binding energy of covalent bonds is not obtained without inclusion of electron correlation effects [82,83,84]. Electron correlation plays an essential role in the dissociation process of the covalent bonds of molecules. For example, the stable C–C single bond of an alkane in equilibrium geometry is converted into different orbitals for different spins (DODS) [82] responding to a singlet diradical state at an intermediary stage of the dissociation reaction, providing two free radical species with local electron spin at the dissociation limit. This type of correlation in covalent bond fission is often referred to as non-dynamical or static correlation in quantum chemistry [82,83,84],

where R denotes a substituent introduced for stabilization of local spin for molecular quantum devices.

RC–CR → RC•…•CR → RC• + •CR

The bifurcation of a closed-shell orbital into open-shell DODS orbitals occurs at the threshold of the triplet instability condition [85,86] for the MO-theoretical model, for which the HOMO-LUMO orbital energy gap (ΔEHOMO-LUMO) becomes smaller than the electron–electron repulsion (U), namely ΔEHOMO-LUMO/U < 1 [87]. This in turn means that the orbital bifurcation arising from the instability is essential for MO-theoretical description of the dissociation, indicating an important role of the electron repulsion effect (U). Thus, quantum systems for which the U-term is essential are also referred to as SCESs in chemistry and biology. In this review, MO-theoretical models are employed for the description of open-shell molecules with local spins [87].

In the 1970s, diradical species with two local spins in Equation (1) were extensively studied in relation to the so-called symmetry-forbidden reactions according to the Woodward–Hoffman [80] symmetry-conservation rule. The HOMO-LUMO mixing procedure [87] was developed to obtain the DODS orbitals for diradical species [47], providing the concept of the orbital bifurcation

where θ denotes the orbital mixing parameter determined by Hartree–Fock (HF) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. and denote the DODS orbitals for up (down)–down (up) spins, respectively, indicating the broken symmetry (BS) if HOMO () and LUMO () have different spatial symmetries.

The BS method was successively applied to elucidate structure and bonding of diradical intermediates generated in several oxygenation reactions [29,33,88,89]. Beyond the BS single-determinant approach, methods such as multi-reference (MR) configuration interaction (CI) [90] were also performed for quantitative purposes: namely, complete active space (CAS) self-consistent field (SCF) [91] for the non-dynamical part of correlation and MR CI [90] for inclusion of remaining dynamical electron correlations. The details of these theoretical models [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91] are given in our review article [47]. The recovery of the BS via quantum resonance [26] is revisited in Section 4.

2.2. Molecular Magnetism for Clusters and Crystals of Open-Shell Systems

In the 1980s, both experimental and theoretical efforts were performed to realize molecular magnetic materials consisting of open-shell molecules. Realization of a pure organic ferromagnet was one of the main interests in the field of molecular magnetism. Ab initio computations were feasible for aggregates of molecules because of developments of computational facilities. Molecular aggregates of closed-shell molecules such as water molecules [92] were mainly investigated by the ab initio HF and HF Møller–Plesset (MP) [93] perturbation methods. On the other hand, our group have been interested in ab initio computations of clusters of open-shell molecules such as free radicals to elucidate the spin alignment rules for aggregates of molecular spins [94,95]. Many theoretical and experimental investigations were indeed performed to obtain organic ferro- and antiferromagnetic materials, namely realization of the long-range order even for s- and p-electron systems without strong spin–orbit interaction. Finally, organic ferromagnetism was discovered for a three-dimensional (3D) crystal of para-nitrophenyl nitroxide (p-NPNN) [96] and related nitroxide radicals [97]. The ferromagnetic phase transition temperature was also reproduced by the Langevin–Weiss model using the calculated effective exchange interactions between p-NPNNs [98]. Thus, long-range orders of s- and p-electron systems were indeed realized in the field of molecular magnetism [99,100].

2.3. Dimensionalities of Lattice, Scale Factor and Spin Variables for Molecular Material

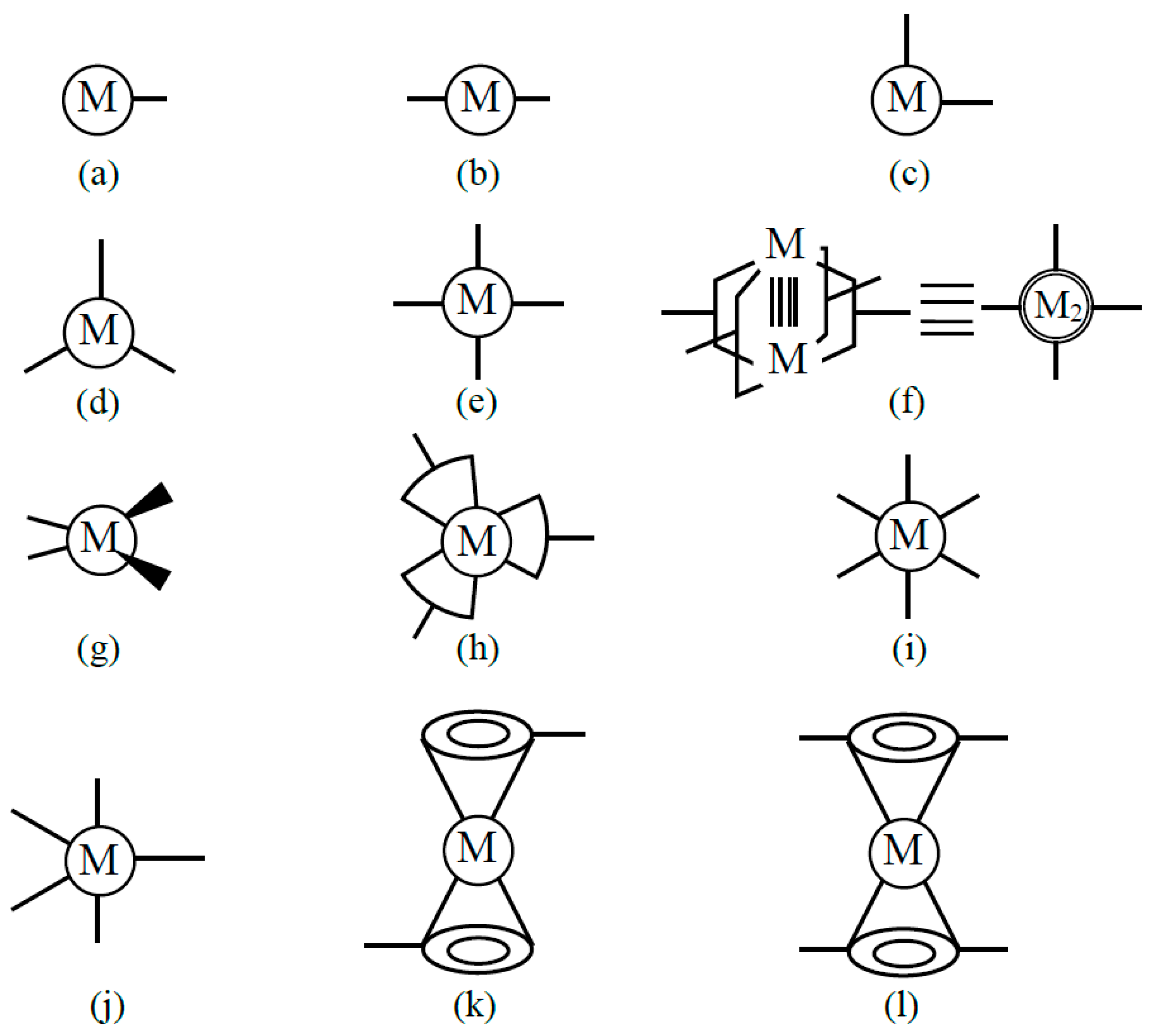

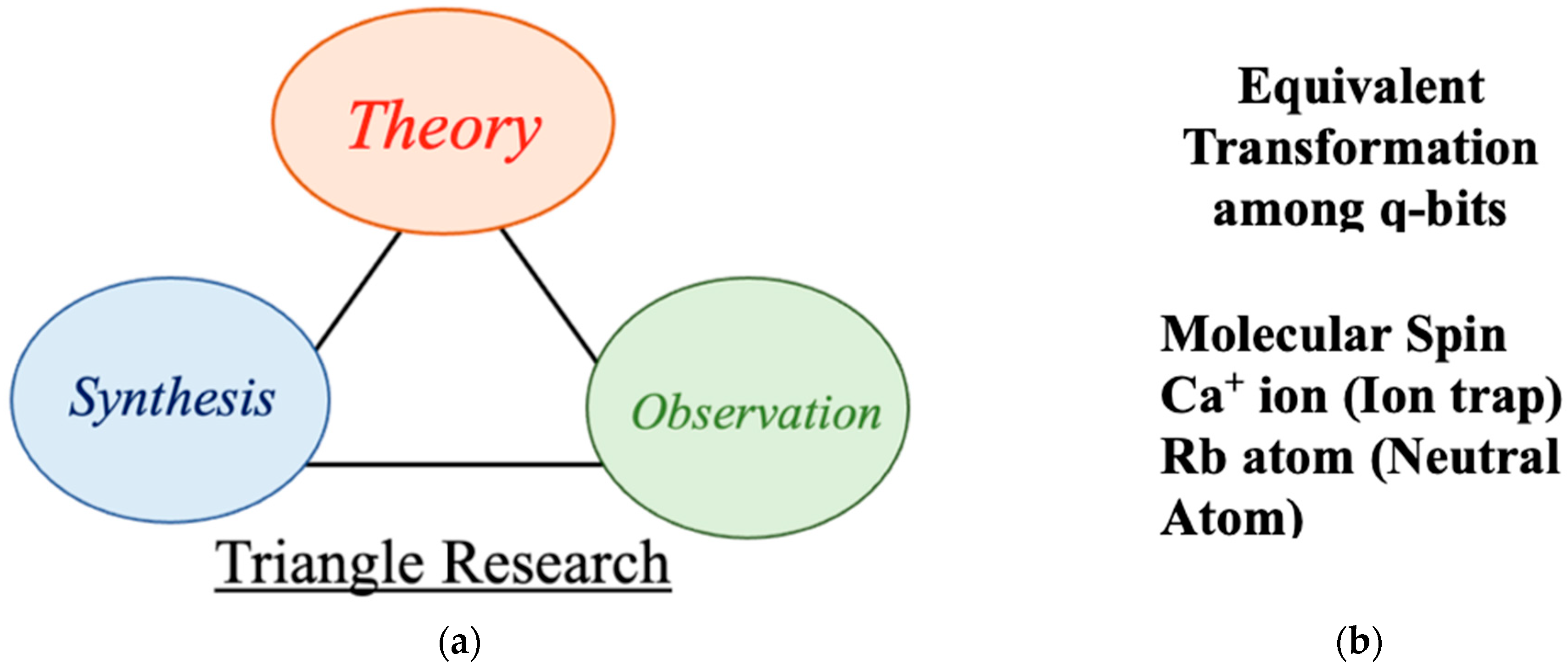

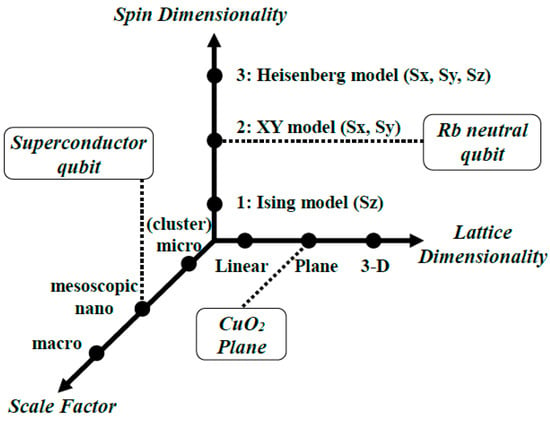

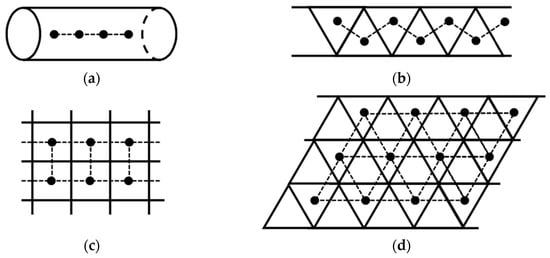

In the 1990s, fundamental concepts and thinkings were required for the designs of new quantum molecular materials [37]. To this end, at the NATO ASI conference in 1994 [37], we proposed Figure 1 covering the theoretical aspect of aggregates of open-shell molecules with spin from the quantum information point of view. As mentioned above, the ferromagnetism of p-NPNN was discovered, indicating the importance of 3D ferromagnetic exchange interactions for realization of the long-range order of molecular spins. After the discovery of the long-range order [96,97,98], quantum effects for molecular spins [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] have been a target for theoretical investigations [37]. Three important variables have been considered for magnetism in general as illustrated in Figure 1: (A) spin dimensionality, which describes the type of interaction between spins, namely the one-dimensional (1D) Ising model [101] expressed by the spin operator Sz, 2D XY model given by two spin operators Sx and Sy [102] and 3D Heisenberg model [103] as follows:

where i and j denote sites of spins, and spin operators are given by the Pauli matrices [104] for quantum spins: Sx = 1/2σx, Sy = 1/2σy and Sz = 1/2σz.

HIsing = −2Jz Σ Szi, •Szj,

HXY = −2 Jx Σ Sxi, •Sxj – 2 Jy Σ Syi, •Syj,

HHeisenberg = −2 Jx Σ Sxi, •Sxj – 2 Jy Σ Syi, •Syj – 2 Jz Σ Szi, •Szj

The second factor (B) in Figure 1 is the lattice dimensionality (1D, 2D, 3D): for example, the 1D lattice of the Haldane system [17], the 2D lattice for the CuO2 plane of La2CuO4 [19,26,31,102] and the 3D lattice of open-shell molecules such as p-NPNN crystals [96,97,98]. Lattice dimensionality plays an important role in classical and quantum behaviors of spin systems in general [37,46]. The third factor in Figure 1 is the scale factor for molecular systems: micro, mesoscopic and macro sizes. The magnetic properties (M) can be regarded as functionals of three variables: M = f(A, B, C) [37] as schematically illustrated in Figure 1.

Spin Hamiltonian models in Figure 1 have been used as pseudo spin models for many other quantum systems [47,78]. Equivalent transformations among quantum spins, excited states of atoms and molecules, etc. indeed indicate similar behaviors to those described by several spin models such as the Ising model for trapped ions [105], the XY model for a two-dimensional (2D) lattice of neutral atoms [106,107], etc., as illustrated in Figure 1. This type of analogy is discussed for the understanding and explanation of trapped-ion and neutral-atom systems in a later section.

Figure 1.

Magnetic properties as a function of three important variables: spin dimensionality, lattice dimensionality and scale factors. This diagram provides guiding principles for design and chemical synthesis of quantum materials via through-bond and through-space alignments of molecular spins. The diagrams are also useful for understanding and explanations of several related materials: the XY spin model is applicable to laser-excited neutral atoms such as Rb [106] aligned by optical tweezers [107]. The superconductor qubit [13,32,36] is regarded as a typical example of the mesoscopic system in the scale factor. The CuO2 plane of La2CuO4 crystal is regarded as a typical two-dimensional (plane) system in the lattice dimensionality.

Figure 1.

Magnetic properties as a function of three important variables: spin dimensionality, lattice dimensionality and scale factors. This diagram provides guiding principles for design and chemical synthesis of quantum materials via through-bond and through-space alignments of molecular spins. The diagrams are also useful for understanding and explanations of several related materials: the XY spin model is applicable to laser-excited neutral atoms such as Rb [106] aligned by optical tweezers [107]. The superconductor qubit [13,32,36] is regarded as a typical example of the mesoscopic system in the scale factor. The CuO2 plane of La2CuO4 crystal is regarded as a typical two-dimensional (plane) system in the lattice dimensionality.

2.4. J-Model for the High-Tc Superconductivity and Isolobal Isospin Analogue

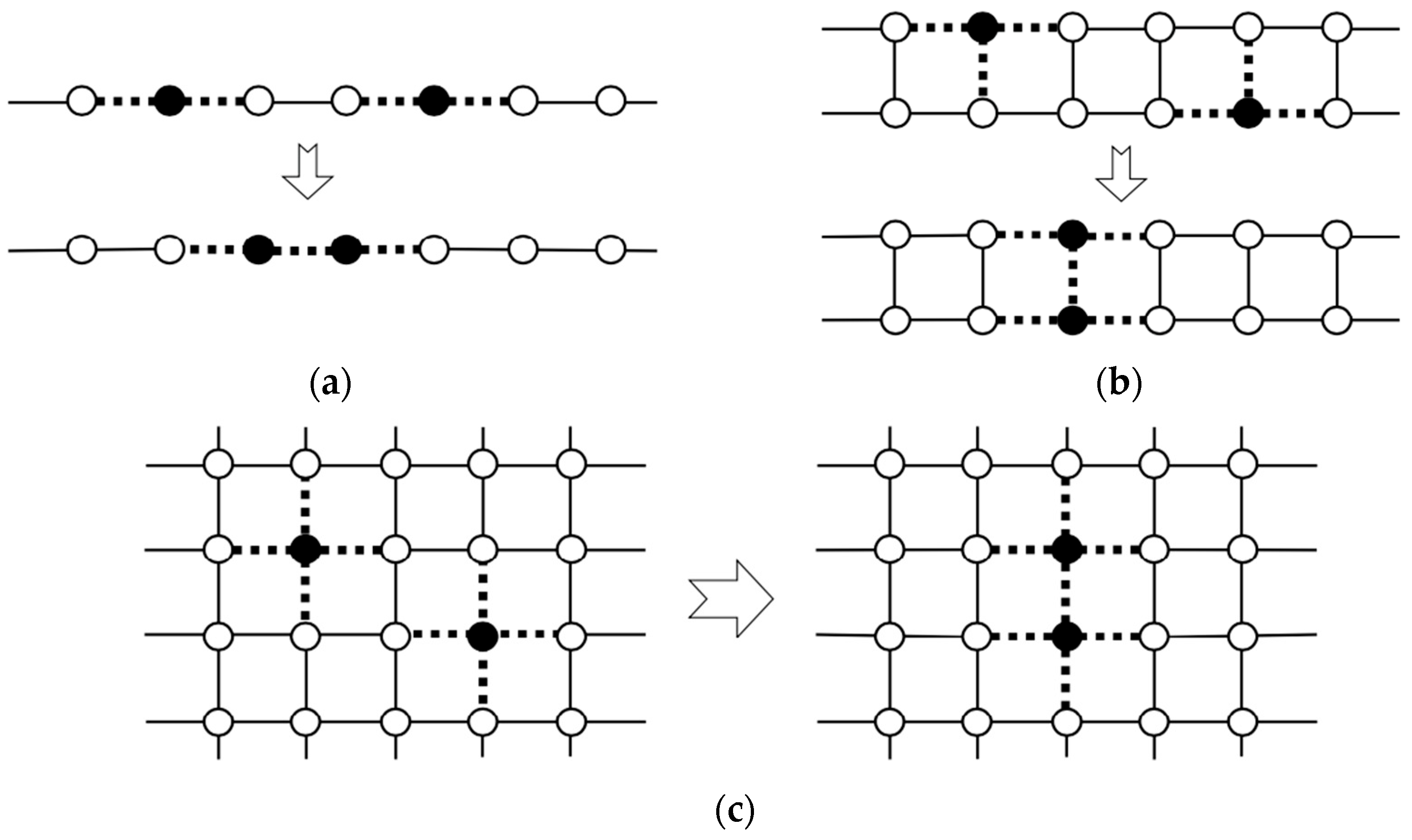

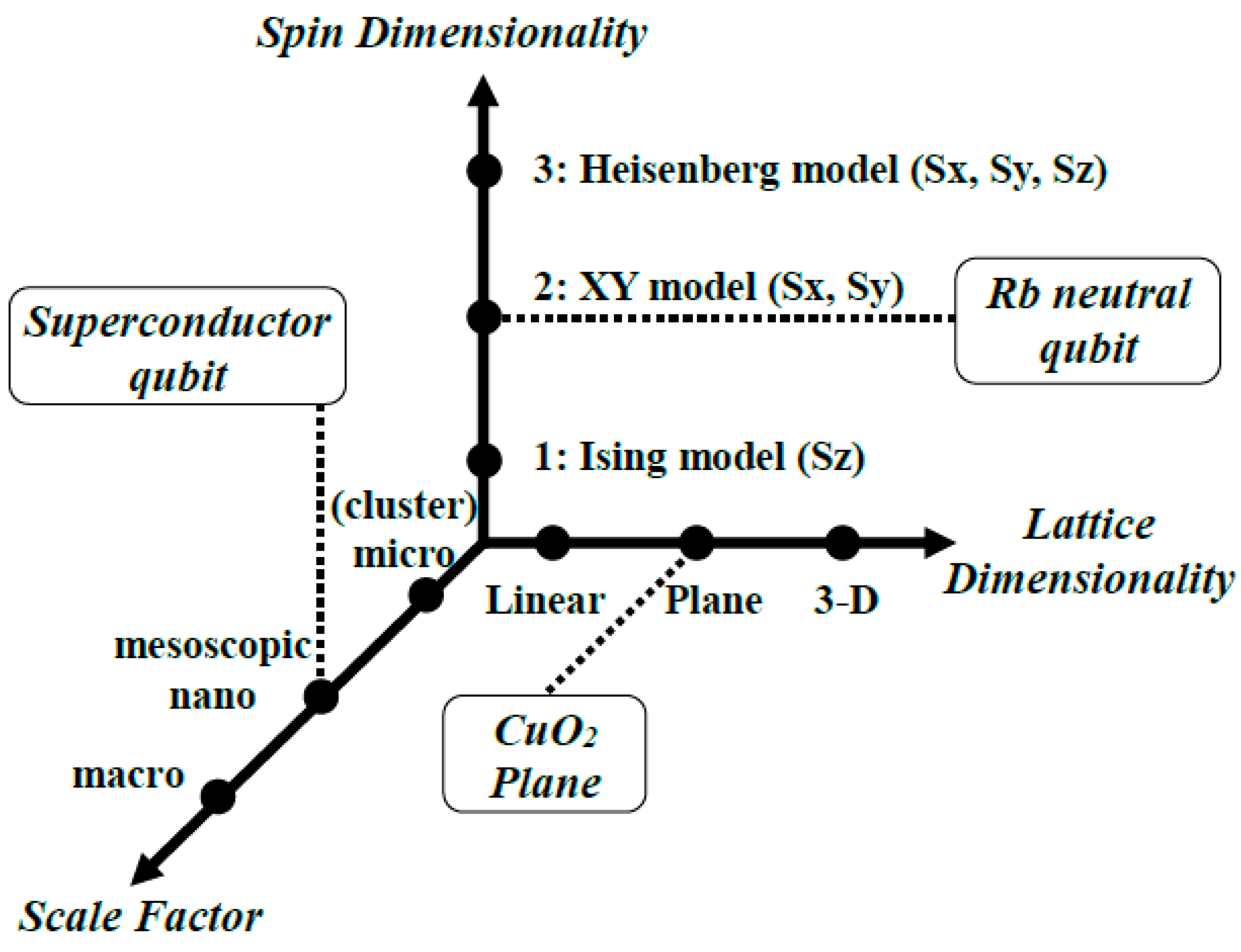

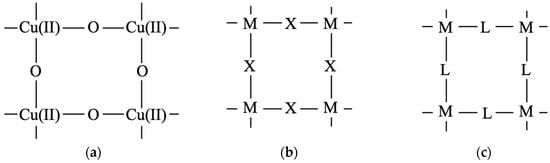

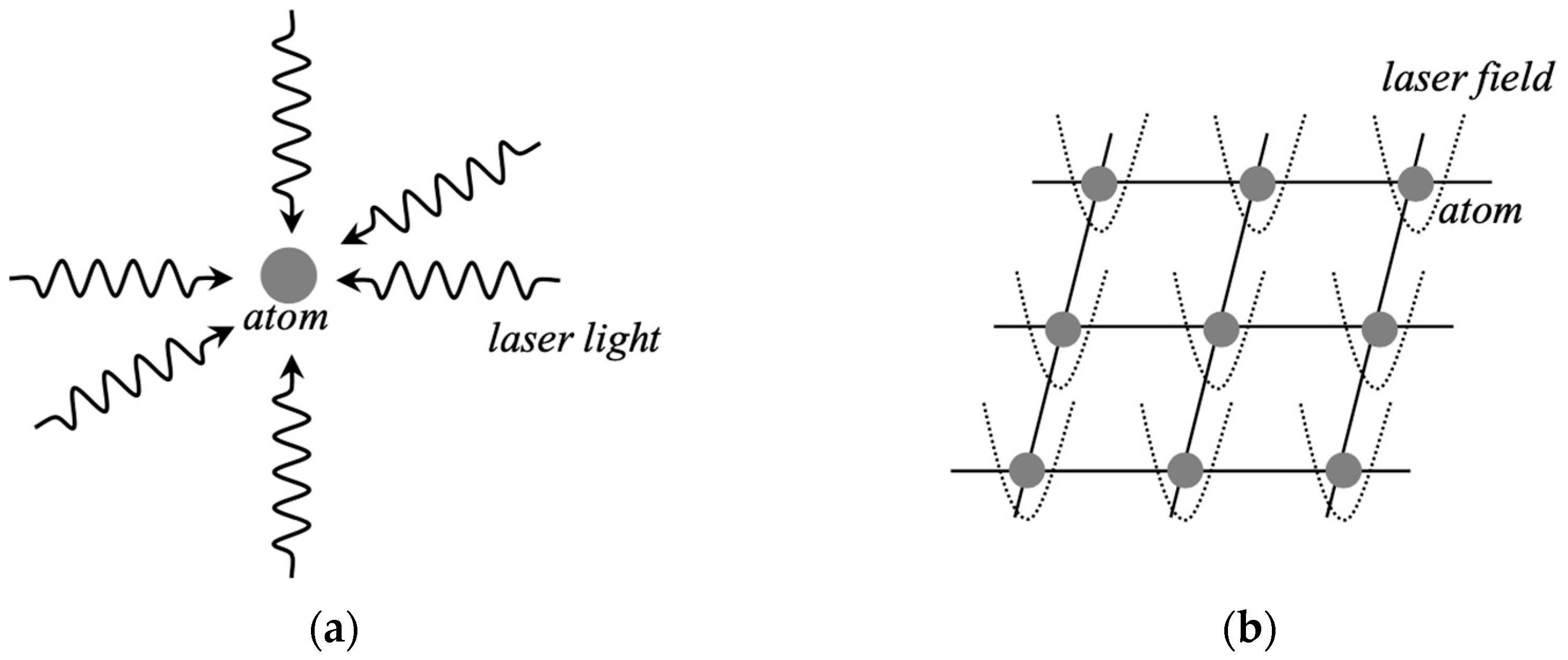

A simple theoretical model was considered to understand the high-Tc superconductivity of copper oxides [19] as illustrated in Figure 2 [28,30,31]. One-hole doping in the square-planar CuO2 plane destroys four superexchange interactions (−4 J). One-more-hole doping at another site also entails the loss of 4 J, indicating a total loss of 8 J. On the other hand, the total loss becomes 7 J under the formation of a Cooper pair in the CuO2 plane as illustrated in Figure 2. This indicates that the energy loss is given by 7 J − 8 J = −J, indicating the binding energy for Cooper pair formation of the superconductivity. Similar situations are obtained for a one-dimensional (1D) lattice (3 J − 4 J = −J) and for a two-dimensional (2D) ladder (5 J − 6 J = −J) as shown in Figure 2. Therefore, we have proposed the |J| model for high-Tc superconductivity in the first transition metal (M) oxide series (M = Cu, Ni, Co, Fe, etc.) [28,30,33].

where c (~0.1) is a parameter for phenomenological and empirical estimation. In this manuscript, the J-values are expressed in wavenumbers (cm−1); 1 cm−1 corresponds to 1.43878 K.

Tc = c J

Figure 2.

Schematic illustrations of the J-model for the high-Tc superconductivity. The black dots denote the hole introduced in the one-dimensional lattice (a), (b) two-leg ladder and (c) two-dimensional square planar lattice [30]. The arrows denote the formation of the Cooper pair formed in these lattices.

3. Design and Synthesis of Molecular Quantum Systems

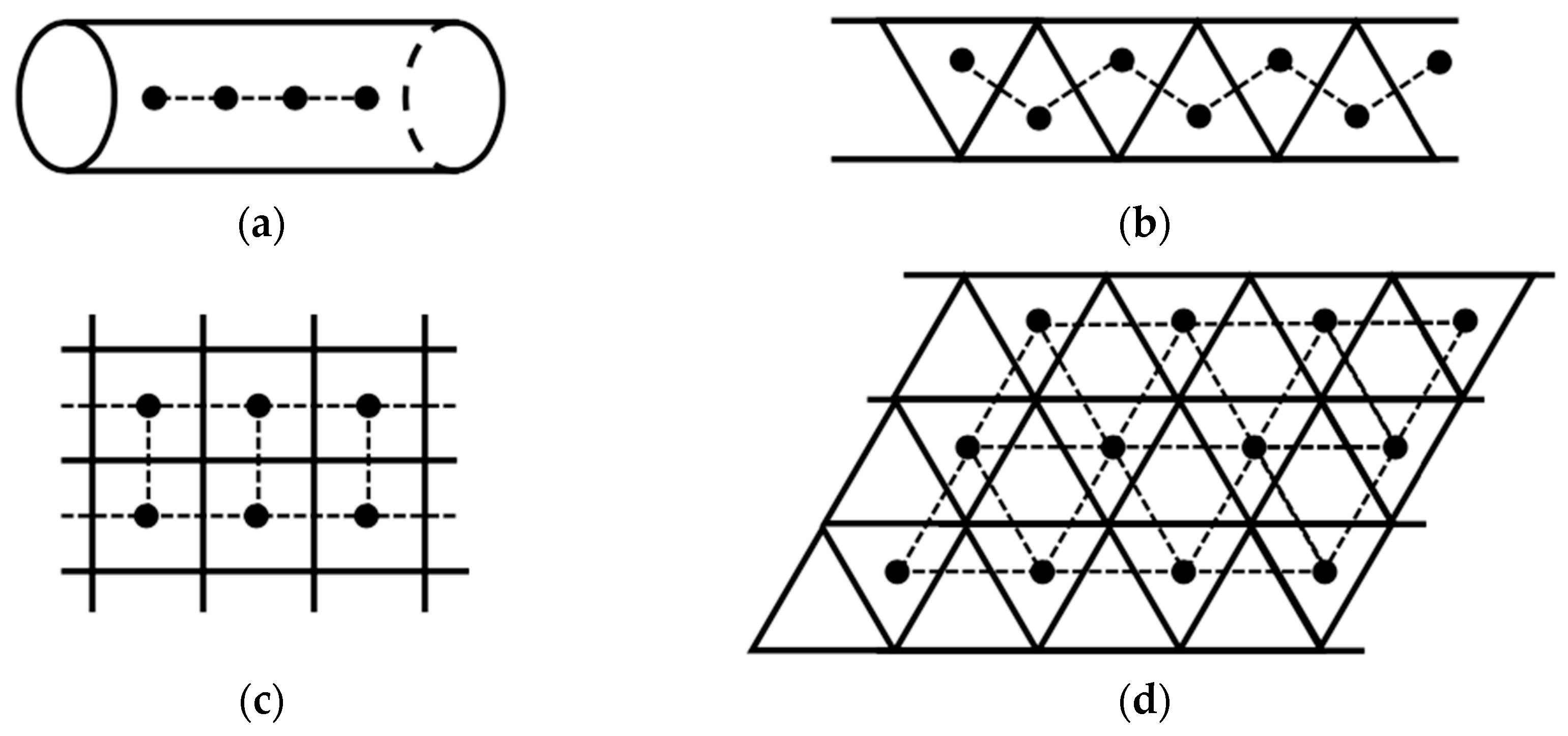

3.1. Through-Bond and Through-Space Alignments of Spins of 1D and 2D Lattice

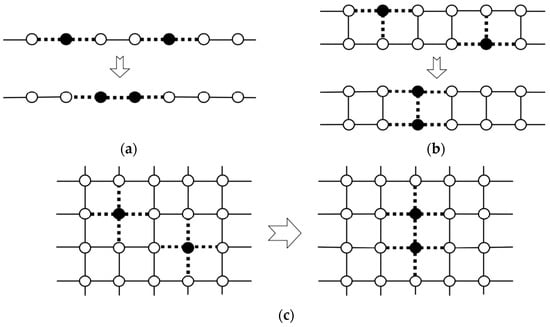

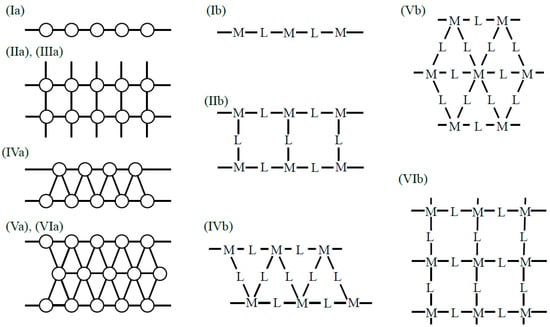

In our project on organometallic conjugation (OMC) [38,39], various systems exhibiting interesting magnetic behaviors have been studied and discussed in the light of three characteristic variables in Figure 1. From Figure 1, quantum effects for spins are expected from low-dimensional systems in general [48,78]. Several typical 1D and 2D systems were considered on theoretical grounds as illustrated in Figure 2 [37]. One-dimensional spin lattices with through-space (Ia) and through-bond (L: linker) (Ib) have been interesting systems as shown in Figure 2. Bulk 1D systems with an integer spin component (S = 1, 2, …) in the Heisenberg chain have been predicted to exhibit the so-called Haldane gap [17] between the ground and excited states, although the gaps are expected to be zero for a 1D chain consisting of half-integer spins (S = 1/2, 3/2, etc.). The Haldane gap was indeed observed for a 1D inorganic Ni(II) complex (Ib) by the magnetic measurements [108], indicating a quantum effect of spins in the 1D system.

Through-space and through-bond (L) square-lattice structures [37,39] have also been important model systems as illustrated in IIa (organic analog) and IIIa and IIb in Figure 2, respectively. A typical IIb-type square lattice by OMC is the aforementioned CuO2 plane (M = Cu(II) and L = O2− dianion) of high-Tc copper oxides [19,26,28,30,31,32,33]. K2NiX4 (X = O, F)-type magnetic solids [109,110,111] have such square-planar lattices in general. Isoelectronic and isospin square lattices have been investigated by both experimental [108,109] and theoretical [110,111] methods to elucidate possible analogs of the high-Tc superconductivity of copper oxides. Cluster models for the lattices have also been investigated to elucidate the sign and magnitude of superexchange integrals (J) between transition metal ions. The calculated J-values have been used for estimation of the transition temperatures (Tc) of superconductivity of analogous systems [28,30].

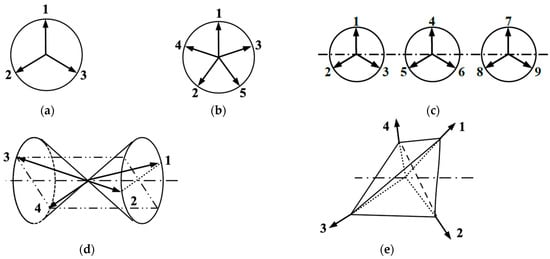

Through-space and through-bond (via L) triangular-ladder structures have been interesting model systems, as illustrated in IVa and IVb in Figure 3, respectively. In 1975, triangular clusters and odd-membered clusters were investigated using classical spin models [112,113], providing the triangular and helical spin alignments, respectively, as shown in Figure 4. In the 1980s, realization of such spin orders was one of the goals in molecular magnetism [37,108,110]. On the other hand, spin frustration in these systems was also investigated theoretically in relation to high-Tc superconductivity [26,30]. The resonating VB (RVB) model [26] was proposed as a guiding theoretical model for spin frustration systems in Figure 4.

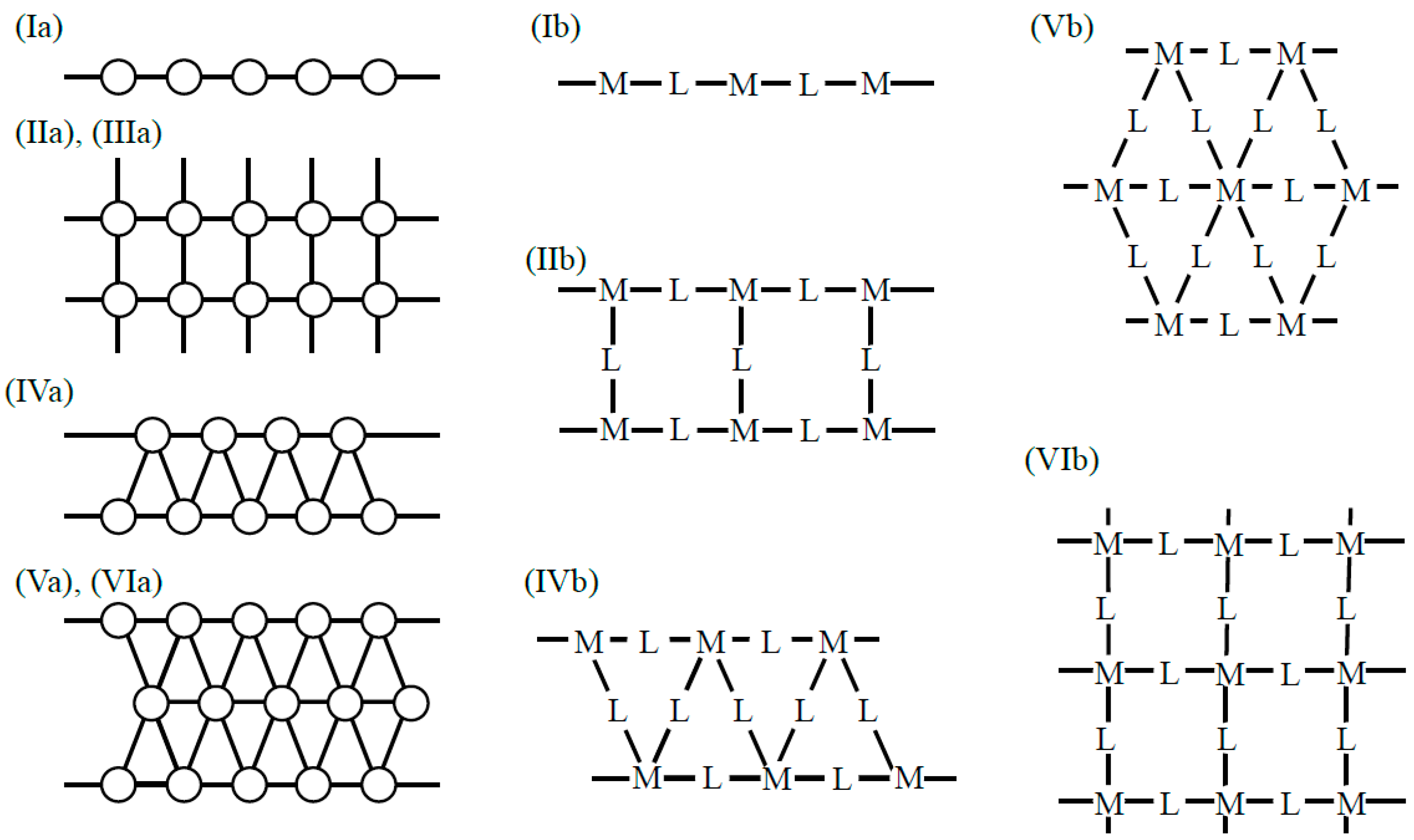

Figure 3.

One- and two-dimensional systems consisting of through-bond and through-space alignment procedures for open-shell molecules and transition metal ions and linkers L (or spacers). Details are given in the text and Chapter 2 in the book [38].

Figure 4.

Non-collinear and helical spin structures for triangular cluster (a), odd-membered ring (b), linear chain of the triangular cluster (c), cone of four-spin vector (d) and tetrahedral spin clusters (e) under the early classical spin model [111,113]. These clusters have 2D and 3D spin structures in the spin dimensionality in Figure 1. The spin frustration spin states obtained by resonating VB (RVB) methods have been regarded as the quantum spin states for these systems under current investigations [26,30,36,102,114,115].

Recently, spin frustration systems have received renewed interest as spin quantum systems relating to spin liquid state [114]. A typical IVb-type ladder has been considered as a possible candidate for high-Tc copper oxides [37]. Isoelectronic and isospin triangular lattices have also been investigated by both experimental and theoretical methods because of several reasons such as spin frustration [26,30]. Cluster models for these lattices have been investigated to elucidate the sign and magnitude of superexchange integrals (J) between molecular spins [29]. More complex triangular systems (Va, Va, VIa, VIb) have also been considered as related models for spin frustrations [111]. Very recently, triangular lattices have attracted great interest in relation to spin liquid phenomena for BEDT-TTF derivatives [115] at low temperature.

3.2. Through-Bond Organometallic Conjugation for Construction of Spin Networks

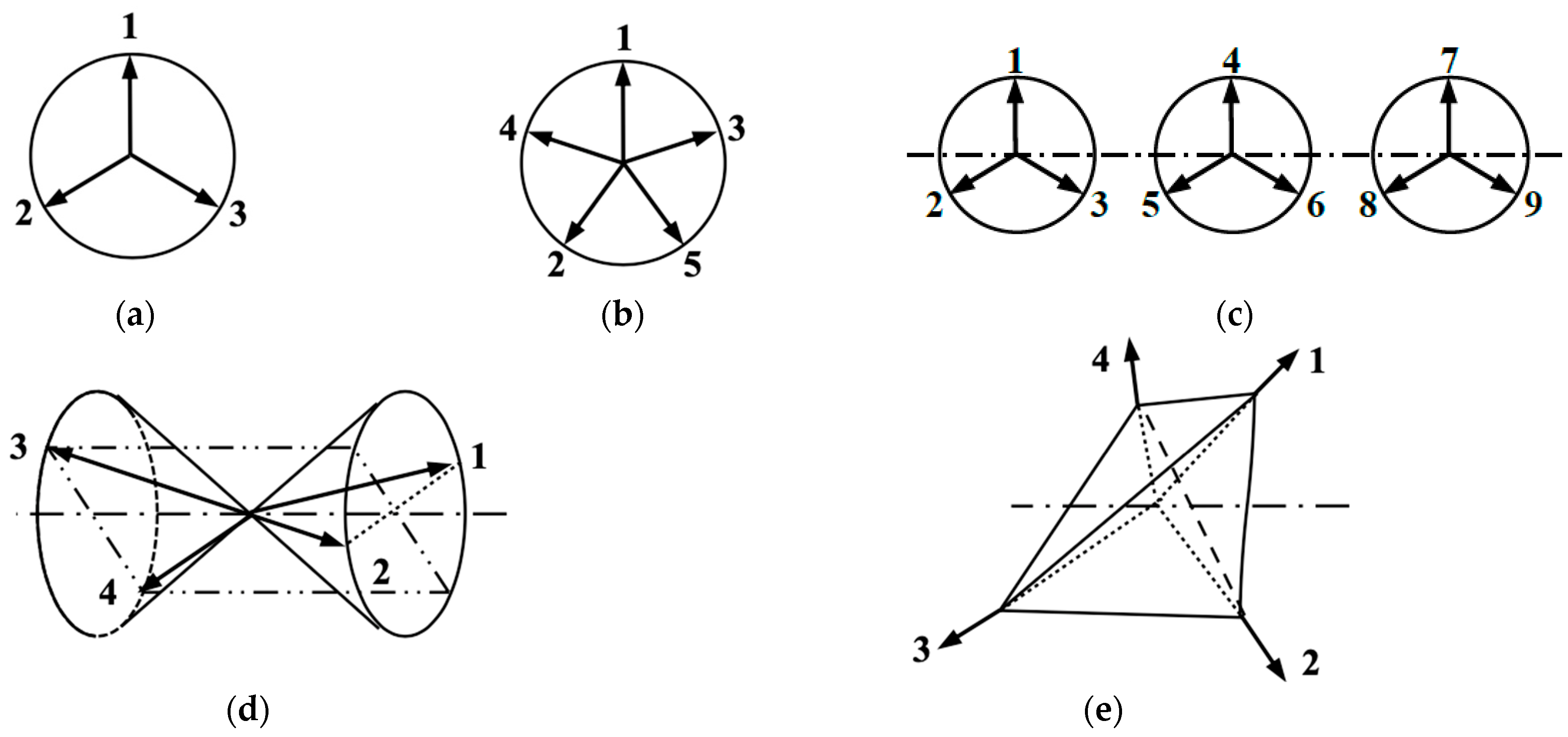

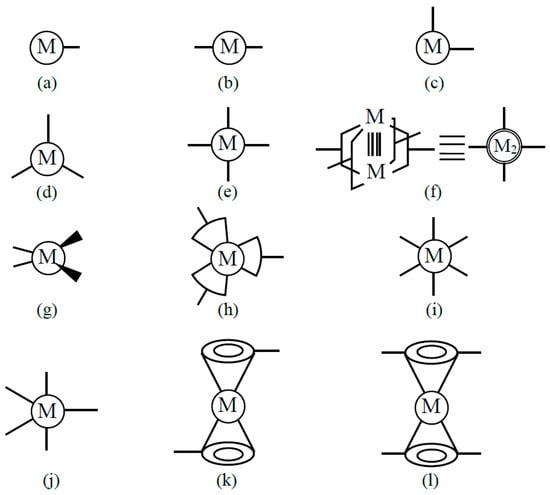

Transition metal complexes with d-electron spins are often used as building blocks for several kinds of spin lattices [39]. Coordination ligand fields of transition metal ions have been examined to elucidate possible bonding models for constructions of organometallic conjugation (OMC) systems in our project on OMC from 1994–1996 [38,39]; some of them are illustrated in Figure 5. The metal ions with one coordination site Figure 5a are used to construct zero-dimensional molecules such as M-halogen and M-OR bonds. The metal ions with two linear perpendicular coordination sites (b) are effective to construct a 1D chain of Ib type in Figure 3. On the other hand, the metal ions with perpendicular coordination sites (c) are used for the construction of square lattices in Figure 3. The metal ions with four planar coordination sites (hands) in (e) and (f) are also used for constructions of square lattices.

Figure 5.

Metal ions with one (a), two (b,c,k), three (d,h), four (e,f,g,l), five (j) and six (i) coordination sites for bond formation are used for the constructions of organometallic conjugation (OMC) systems as explained in the text and in the book [38] which summarize the results obtained by specially promoted project on OMC from 1994–1996 [38,39]. These metal ions are used for constructions of the 1D and 2D systems illustrated in Figure 3 and non-collinear spin systems in Figure 4.

The metal ions with three coordination sites Figure 5d, h are used for the construction of a triangular lattice and a six-membered ring Figure 3VIb. The metal ions with a tetrahedral ligand field (g) are used for linear chains such as linear Fe-S cluster systems [116]. The metal ions with octahedral ligand fields (i) and trigonal bipyramid ligand fields (j) are used for constructions of square planar [111] and triangular [117] x–y-planes linked by axial ligands along the z-direction, namely three-dimensional (3D) porous metalorganic frameworks [39]. Ferrocene-type metal–organic units (j) and (k) are used for construction of complex coordination clusters and coordination polymers (CPs) [38,39]. Metal ions with eight hands (f) are also conceivable for constructions of specific systems. Thus, transition metal ions with protected d-electron spin(s) are effective units for construction of organometallic conjugation (OMC) systems. Chemical syntheses of OMC systems were targets in our special project [38,39].

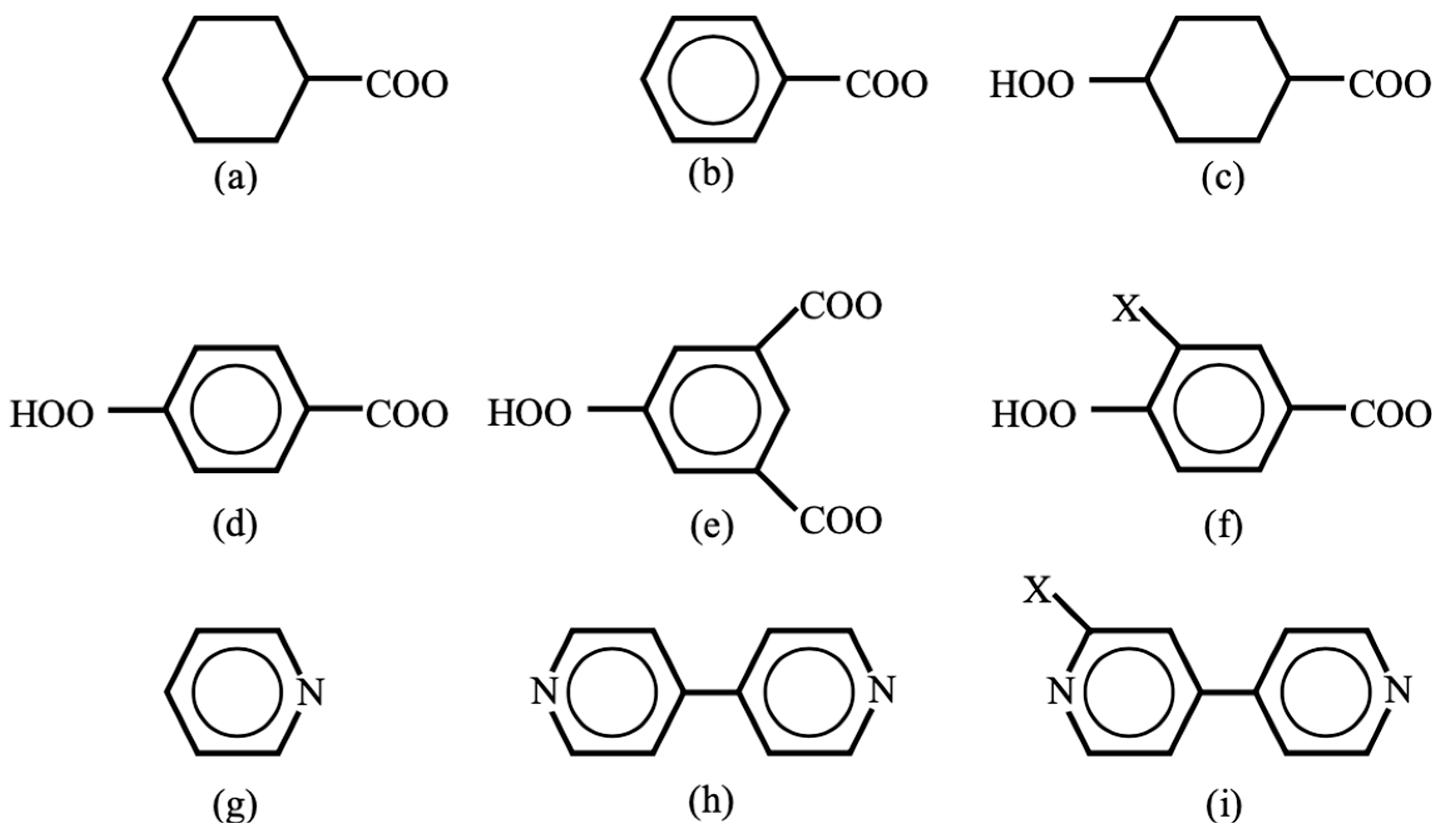

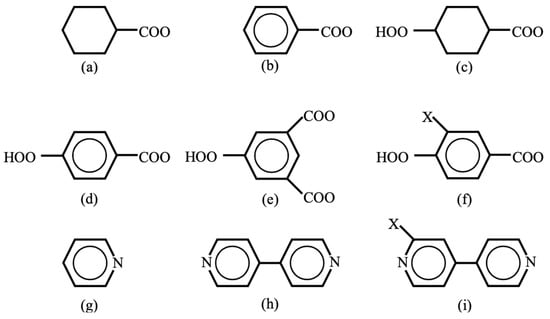

3.3. Organic Ligands with Linker or Spacer Groups for Construction of Confinement Material

Oxygen and sulfur dianions are used as linkers (L) for inorganic transition metal oxo and iron–sulfur complexes [29,116]. According to equivalent transformation on theoretical grounds [47], these dianions were formally replaced with organic dianions in OMC systems. For example, organic carboxylate anion groups [38,39] were used as organic linkers (spacers) L in Figure 3 as illustrated in Figure 6. Cyclohexane and benzene rings are used as mono-carboxylate linkers in (a) and (b) in Figure 6. On the other hand, cyclohexane in (c) [59,60] and benzene in (d) [61,62] with para-bi-carboxylate substituents are linear linkers for constructions of the organometallic conjugation (OMC) system in Figure 3 [38,39]. The benzene ring of the linker in (d) can be replaced with a biphenyl (or triphenyl) spacer to enlarge the size of the porous space of OMC. 1,3,5-trisubstituted benzene rings in (c) in Figure 6 [61] are used as linkers for the constructions of planar triangular lattices in Figure 3. Another substituent X in (f) may be introduced to control rotational angle of phenyl (bi-, tri-phenyl) group.

Trapping and confinement methods of large molecules such as drugs have been developed in the field of molecular recognition. For example, pyrizine-type ligands (g–i) were used in Pd(II) (or Pt(II)) complexes for the construction of square-planar lattices of type IIb in Figure 3 for molecular recognition [66,67]. Therefore, these lattices are also useful for confinement and alignment of large molecular spins as shown below. Thus, many combinations of metal ions in Figure 5 with linker (or spacer) groups are feasible for the constructions of low-dimensional (LD) organometallic conjugation (OMC) systems with desired spin alignments.

3.4. Through-Space Alignments of Open-Shell Molecules by Confinement Materials

Open-shell molecules such as organic radicals are too reactive without confinement. OMC systems can be used as protection materials for open-shell molecules. Nanotubes and graphene have been used as molecular confinement materials [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. One-dimensional and two-dimensional porous OMC lattices were also designed for the confinement and alignment of open-shell molecules as illustrated in Figure 7; see also confined structures in Chapter 6 of ref. [38]. To this end, sizes of open-shell molecules are appropriately selected for special alignments of spins [43,49]. Photochemical procedures for the generations of spins at low temperatures may be necessary for suppression of radical reactions. Linear spin alignments can be formed within 1D hole space generated by appropriate OMC structures as illustrated in Figure 7a. One-dimensional zig-zag spin alignments are also conceivable for a triangular ladder as illustrated in Figure 7b. On the other hand, 2D square-planar spin alignments are designed by confinement of spins within a square-planar space of the 2D OMC lattice. Triangular spin alignments are also conceivable for confinement of spins within a triangular space as illustrated in Figure 7d.

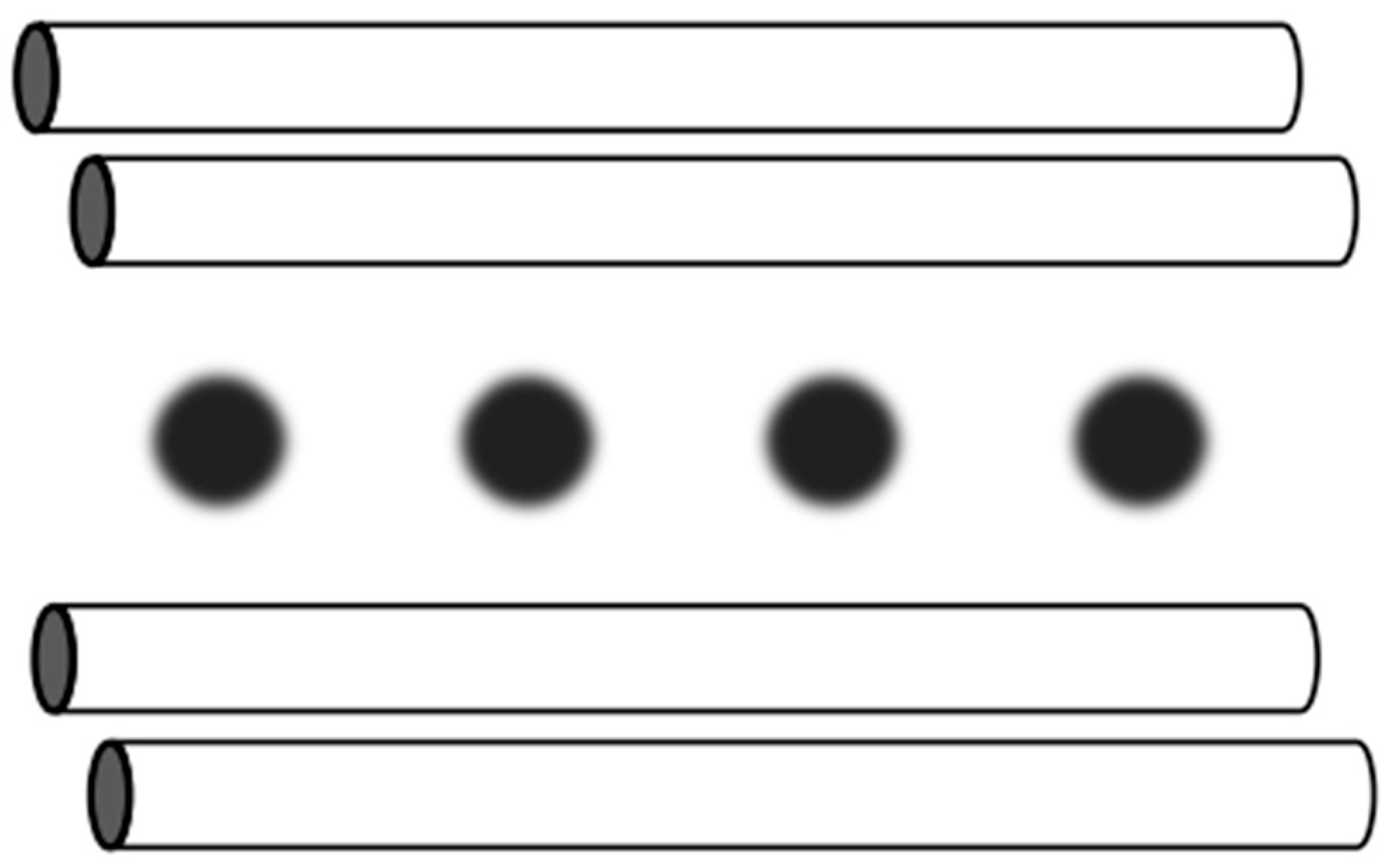

Figure 7.

Through-space alignments of open-shell molecules represented by black dots within 1D linear (a), zig-zag (b), 2D square-planar (c) and 2D triangular (d) lattices confined by molecular materials. On the other hand, the confined open-shell (or closed-shell) molecules are used for active controls of the spin states in the case of the magnetic lattices obtained by the OMC procedures. These two cases were examined in chapter 2 [39] of ref. [38]. The molecular confinement tube material in the 1D (a) system is replaced for electromagnetic devices in the case of trapped-ion systems in Figure 14. On the other hand, the molecular confinement material in 2D (c or d) systems is replaced with the optical lattice for neutral-atom systems in Figure 15.

A different approach for construction of spin devices such as sensors is also conceivable. Confined open-shell molecules in OMC systems can be regarded as control materials for spin properties of triangular, square-planar and kagome-type spin lattices considered in Figure 3 [118,119]. In these cases, the confined open-shell (or closed-shell) molecules are designed to control magnetic behaviors of the low-dimensional spin lattices. These systems may be used as sensing materials. Many other low-dimensional spin sheets are conceivable, depending on crystal structures controlled by interplane interactions. To this end, synthetic efforts will be necessary for the realization of new molecular confinement materials.

4. Through-Bond Spin Alignments for Magnetism and Superconductivity

4.1. Theory of Effective Exchange Interactions for Organic Diradicals

In this section, computational methods for J-values are briefly revisited. As mentioned in Section 2, in 1975, the HOMO-LUMO mixing procedure in Equation (2) was proposed to obtain the DODS orbitals for diradicals. Here, electronic structures of open-shell species are examined briefly in relation to magnetic properties [87]. The HOMO-LUMO energy gaps are zero for mono-centric diradicals such as atomic oxygen (O) and nitrene (NH), and they are nearly zero for methylene (CH2) and related carbenes, indicating the ground triplet state because of Hund’s rule [79,87]. Therefore, these triplet molecules and related open-shell compounds are often used as sources of molecular spins [38,39]. However, the exchange coupling of these triplet species leads to covalent bond formation, providing singlet pair bonds such as the C=C double bond without local spins through a singlet diradical state as follows.

where a dot (•) expresses a local spin in chemistry. This in turn indicates that confinement of open-shell molecules is crucial for suppression of dimerization as illustrated in Figure 6a.

H2C: + :CH2 → •H2C---CH2• → H2C=CH2

The through-bond method is one of the chemical approaches for generation of open-shell systems [120]. The exchange coupling of three (S = 3) and four (S = 4) triplet species with six and eight unpaired spins in total formally provides triplet and singlet diradicals with two local spins, for example [87].

H2C: + H2C: + :CH2 → •H2C–H2C–CH2•

H2C: + H2C: + H2C: + :CH2 → •H2C–H2C–H2C–CH2•

Broken symmetry (BS) methods [87] can describe these exchange coupling processes because there are no spin-coupling restrictions in sharp contrast with the perfect pairing assumption for VB-like models. Spin states of these 1,3-and 1,4-diradicals in Equation (7) are triplet and singlet diradicals which are often described by the isotropic Heisenberg model in Equation (3c) for which J = Jx = Jy = Jz. Therefore, the effective exchange integral (J) for the model is often defined as the energy gap between the singlet and triplet states as in [29,87,120,121].

JDiradical = 1ESinglet − 3ETriplet

The J-values are positive and negative in sign for triplet and singlet ground states of the diradical in the case of the notation in quantum chemistry [120,121].

In Equation (6), the H2C linker can be replaced by isoelectronic O and NH linkers to enable through-bond exchange couplings, yielding 1,3-diradicals such as •H2C–O–CH2•, •H2C–NH–O•, •O–O–O•, etc. [88]. Organic ligands such as -Ph- and -biPh- in Figure 6 also serve as linkers, generating organic diradicals with tunable J-values under quantum controls of spins by external fields [38,39,120,121]. Various quantum mechanical methods including BS MO and MR CI have been employed to calculate J-values for these species; further computational details are provided in refs. [88,120].

4.2. Theory of Effective Exchange Interactions for Inorganic Systems

Effective exchange interactions (J) between transition metal ions with local d-electron spins can also be expressed by the isotropic Heisenberg model. For example, the terminal CH2 radical site in Equation (7a) can be formally replaced with metal ions with carrying local spins, resulting in an M-O-M system as follows [29,120,121]:

where n denotes the oxidation number of transition metal ions. The central oxygen atom in Equation (9) is formally expressed as an oxygen dianion. Transition metal ions are also formally one-electron oxidized through a one-electron transfer during complex formation. The oxygen dianion site can be substituted with other anion groups, such as a sulfur dianion [114] or R-bi-carboxylates dianion (R = benzene, etc.) [38,39,72,73] in Figure 6.

M(n): + •O• + :M(n) → M (n + 1)•–O2−–•M (n + 1)

The average effective exchange integrals (J) between transition metal ions M (n + 1) are given by the energy gap between total low-spin (LS) and total highest-spin (HS) states of the exchange-coupled systems in Equation (8) as follows [29,41,94,121]:

where E(X) denotes the total energy of the Y spin state obtained by computational method X, and <S2(X)> denotes the total spin quantum number of the Y spin state obtained by X. This equation is applicable to both broken-symmetry (BS) and symmetry-adapted methods, including several expressions under approximations. Equation (9) was applied to calculate the J-values for several exchange-coupled M-X-M systems as shown in Table 1 [120,121].

Table 1.

The effective exchange integrals (J) for binuclear transition metal complexes calculated by the broken symmetry methods (a).

From Table 1, the magnitude of the J-values for the naked Cu(II)–O2−–Cu(II) was extremely large [28,29,121], indicating strong superexchange antiferromagnetic interactions via oxygen dianions. This discovery was surprising for us in the early 1980s, raising the serious question of whether there was an error in our computations [29]. However, no mistake was found in our computational scheme in Equation (9) for this specific naked dimer. Therefore, the calculated charge density for Cu(II)–O2−–Cu(II) [29] was considered to suggest the reactivity of the oxygen site with a partial hole for oxygen transfer reactions by copper oxide. The J-values for Cu(II)–(OH)2–Cu(II) were ferromagnetic under the condition of a relatively small Cu-O-Cu angle (θ < 110°) [121]. The magnitude of the J-values for the Ni(II)–O2−–Ni(II) system was also large as compared with other metal oxide systems [28,29]. Spin crossover from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic interactions was observed for M-O-M (M = Mn(II), Fe(III)) systems. The Cu(II)–(OH)2–Cu(II) pair with small Cu–O–Cu angle exhibited ferromagnetic exchange because of the d-orbital orthogonality. The calculated J-values were consistent with available experimental tendencies for transition metal oxides. The calculated J-values for M–O–M axial ligands were also consistent with available experimental results [28,29,121].

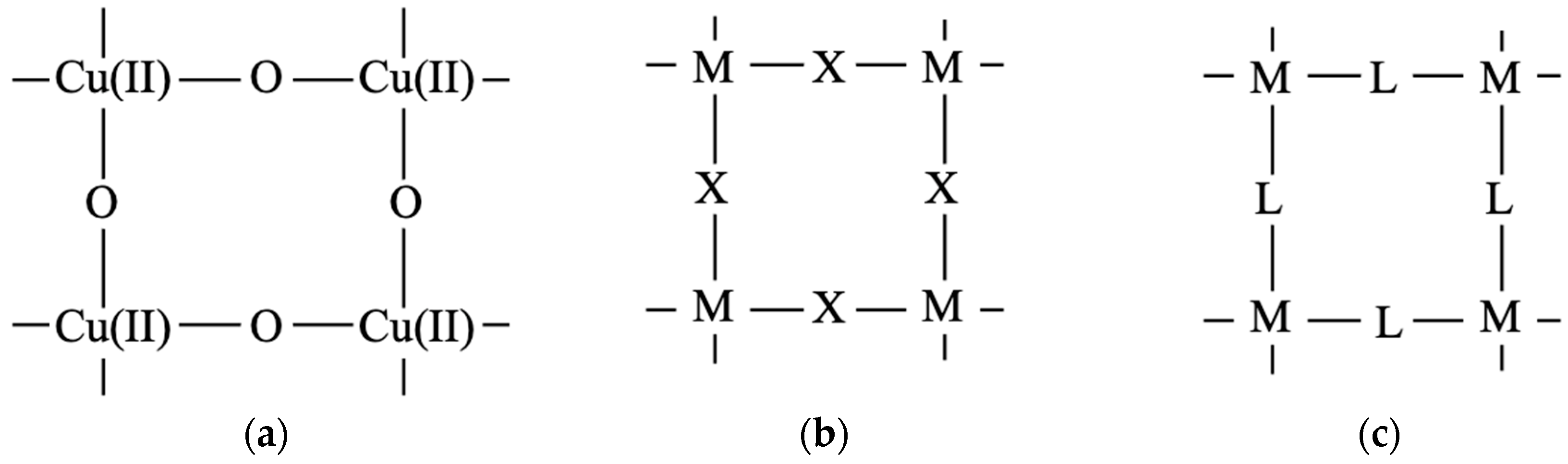

4.3. J-Model for the High-Tc Superconductivity of the First Period Metal Oxide

As mentioned above, in 1986, high-Tc superconductivity was discovered for hole-doped copper oxide of Ln2Cu(II)O4 crystal [19]. This was a great surprise in material science. However, our intuition [28] was that the high-Tc phenomenon is related to the large negative J-value of the Cu(II)-O2−-Cu(II) unit as shown in Table 1. Indeed, Ln2Cu(II)O4 belongs to the family of the K2NiF4 magnetic crystal [109] which has a square-planar lattice, as illustrated in Figure 7 [111]. The square-planar plane in Figure 8 can be composed of CuO2 units [30] as shown in Figure 8a. Neutron diffraction experiments have revealed that Ln2Cu(II)O4 exhibits antiferromagnetism before hole doping [27], although a simple band model predicted it to be metallic. This discovery [27] opened the door for investigations into SCESs to elucidate the possible mechanisms behind high-Tc superconductivity [19].

Figure 8.

Square-planar structure unit model for (a) Cu(II) oxide [111]. (b) Isolobal and isospin transition metal (M) structure using inorganic ion linker (X) and (c) Isolobal and isospin transition metal (M) structure using organic linker (L) in Figure 6 [30,38,39].

We have chemical interest in constructing isolobal and isospin systems based on the CuO2 plane [30]. According to the equivalent transformation [30,47], the CuO2 unit is formally replaced by the NiO2 unit to form the square-planar structure in Figure 8b where M = Ni and X = O2− or M = Ni, X = F−1 [28,30,111]. According to the guiding principle in Figure 3, isolobal and isospin planes, as shown in Figure 8c, can also be constructed by replacing the L site with an organic linker from Figure 6 [61,62]. Ab initio unrestricted Hartree–Fock (UHF) and hybrid DFT methods, with variable UHF exchange terms, were used to elucidate the J-values for the linear M–O–M–O–M and square-planar clusters M4X4 as shown in Table 2 [120].

Table 2.

Ab initio computations of effective exchange interactions (J) for the linear chains M–O–M–O and square-planar M4O4 cluster by UHF and hybrid DFT methods (a).

From Table 2, the J-values for the transition metal oxides with realistic M-O distances were found to be fairly consistent with experimental results. The magnitude of the J-value for the linear Cu–O–Cu–O–Cu unit was larger than that of the square-planar Cu4O4 cluster, although the latter |J| value remained very large compared to the |J| values of other M–O–M systems (M = Mn, Ni) [120,121]. According to this estimation formula, Tc was the highest for hole-doped copper oxides, and the Ni oxides were estimated to have a relatively high Tc as well [28]. Interestingly, high Tc was indeed observed for Ni oxide, 30 years after the theoretical proposal [34,35], demonstrating the practical utility of Equation (10) for qualitative estimation.

4.4. Hubbard Model for Transition Metal Oxides and Estimation of Tc for Superconductivity

In the 1980s, ab initio computations of large transition metal clusters were challenging due to the limitations of our computational facilities. As an alternative, the Hubbard model [122] was employed for so-called strongly correlated electron systems (SCESs) such as the first transition metal halides and oxides examined above. The Hubbard model involves two parameters: (A) a transfer integral (t), which corresponds to the resonance integral (−β) in the Hückel model [81] in chemistry, and (B) an on-site repulsion integral (U) for electrons with up- and down-spins at the same site [30,120,121]. The Hubbard Hamiltonian [122] for open-shell systems was written in the second quantization notation including electron spin σ in quantum chemistry.

where denotes the operator which creates an electron with σ = ↑, ↓ at site i, tij is the transfer integral and U denotes the on-site repulsion integral which is neglected in the Hückel model [80,81]. The corresponding annihilation operator is , and is the spin density operator for spin σ on the i-th site. These fermion operators obey the canonical anticommutation relations.

We determined the t and U parameters for transition metals oxides using atomic parameters obtained from spectroscopic methods [33]. The exact diagonalizations of the Hubbard models for M-O-M and other M-O clusters both with and without hole doping were performed by considering all the VB configurations [120]. The calculated J- and Tc values are summarized in Table 3 [120].

Table 3.

The transfer integral (t), p-d orbital energy gap (∆E), calculated and experimental J-values and proposed Tc values.

From Table 3, the calculated J-value for the Cu–O–Cu unit by the perturbation method was about twice that of the exact diagonalization, indicating the breakdown of the weak electron correlation model. The exact diagonalizations [33,120] revealed that the charge-transfer (CT) configuration from the central dianion (p-electron pair) to the open-shell d-orbital plays a significant role in enhancing of the negative J-values for M–X–M systems, indicating the importance of the p-d energy gap for estimation of the J-values. The magnitude of the J-value for Fe–O–Fe was small because of the large p-d energy gap, indicating the necessity of replacement of the O-site with more electron-donating S, P, As, etc. to increase the Tc values. However, at that time, such chemical modifications were not considered. Many Fe-As high-Tc superconductors have already been discovered [123]. More recently, high-Tc nickel oxide superconductors [34,35] were discovered, supporting our estimation in Table 3. This suggests that the isolobal and isospin analogy is effective and practical for predictive considerations of new possibilities in material design [46,120].

The exact diagonalizations [33] of the Hubbard model [122] have elucidated populations of doped holes over the M–X–M and many M–X type clusters [120]. The doped holes were found to be mainly localized on the oxygen site for Cu-O clusters, indicating the important role of charge degree of freedom, namely charge transfer (CT), in high-Tc superconductivity. Therefore, the CT mechanism has been applied as a possible model for the design of high-Tc molecular superconductors [30,120]. Thus, both charge and spin degrees of freedom play crucial roles in the emergence of exotic states in strongly correlated electron systems (SCESs) composed of organometallic conjugation (OMC) [38,39,47,120]. Discussions of other possible phases for extended (M–X)n and (M–M–X)n systems are summarized in the book [120].

5. Through-Space Spin Alignments by Molecular Confinement Materials

5.1. Alignments of Open-Shell Systems by Molecular Confinement Materials

In this section, through-space spin alignment is examined on theoretical grounds. Alignment of open-shell molecules is hardly possible since dimerization of them occurs easily to form closed-shell dimers as in the case of dimerization in Equation (5). Therefore, appropriate molecular confinement materials (MCMs) are crucial for through-space alignments of open-shell molecules as illustrated in Figure 6. In the 1990s, several research groups [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] performed chemical synthesis of such molecular materials instead of zeolites. We performed theoretical design and computational simulations as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 7 [38,39]. Developments of our efforts are given in chapter 10 of the book [120].

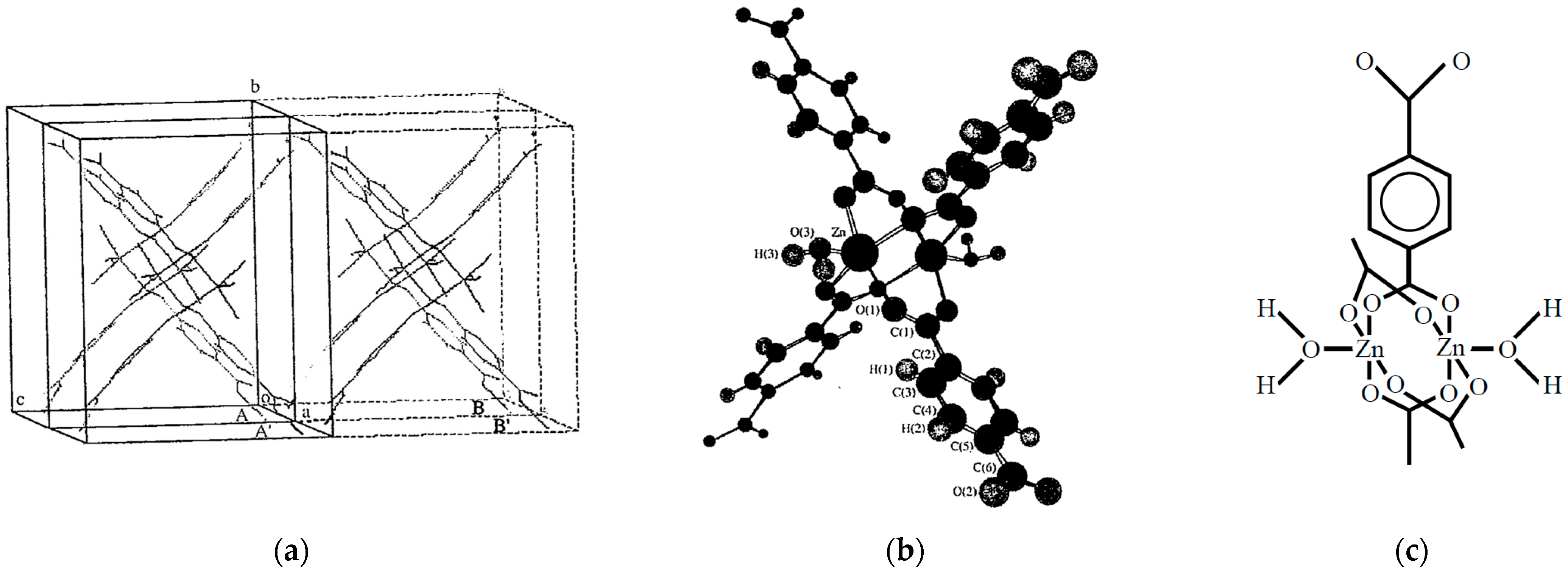

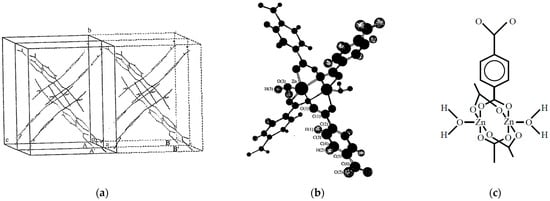

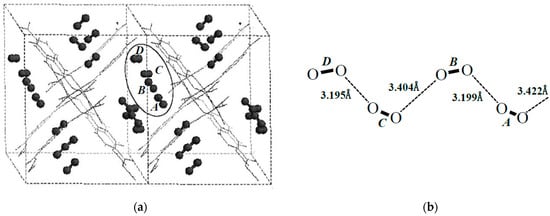

Here, our early theoretical simulation for confinement of open-shell molecules with a metal–organic framework (MOF) is revisited briefly. In the 1990s, the Yaghi group reported the crystal structure of Zn3(BDC)3• CH3OH:BDC = 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate in Figure 5d [61,62]. In this review, this compound is abbreviated as Zn(BDC). The crystal Zn(BDC) (H2O) with DMF molecules has the unit cell classified by a space group of P21/n with cell parameters a = 6.718 A, b = 15.488 A, 12.431 and β = 102.8º [62]. This crystal was stable even after the removal of solvent molecules (DMF). According to the crystal structure of Zn(BDC), a 1D cavity is formed for adsorption of gases such as N2, O2, etc. This means that the Zn(BDC) crystal may be used for one of the most appropriate materials for theoretical investigation of the confinement effect of open-shell molecules.

The Zn(BDC) molecule has a binuclear complex with four hands, namely Figure 5f, as shown in Figure 9a. The unit cell of the Zn(BDC) is also shown in Figure 9b. Here, adsorption of molecular oxygen is examined as an example of the confinement of open-shell molecules. Molecular oxygen is the ground triplet (S = 1) species which is a possible candidate for 1D chains in Figure 7a, which has received great attention due to the Haldane conjecture [17]. Therefore, we have performed theoretical investigations of the adsorption systems [43].

Figure 9.

(a) The packing structure [62] of Zn3(BDC)3 (BDC = 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate in Figure 5f). (b) Schematic illustration of the molecular structure in the Zn2BDC4 in the crystal and (c) the chemical structure of Zn2BDC4 with two coordinated water molecules as building block for the lattice [43]. The Monte Carlo calculations performed assuming the crystal structure [43].

5.2. Monte Carlo Simulations of the Open-Shell Systems

Our theoretical procedures [43,120] are split into four steps: step 1: decision of parameters for Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, step 2: MC simulations for adsorption, step 3: elucidation of configurations of O2 molecules by molecular mechanics (MM) calculations and step 4: computations of effective exchange interaction between O2 molecules by quantum mechanical (QM) methods. As the first step, we performed the grand canonical MC (GCMC) simulations of single-gas adsorption using general force-field (FF) parameters by CERIUS-2 [124]. The necessary charge densities on each atom for GCMC were obtained by UHF and UB3LYP computations [43].

A series of GCMC simulations [43] were first performed for adsorption of N2 and CO2 with Zn(BDC) to elucidate scope and reliability of GCMC in comparisons of available experiments [61,62]. The sampling number for GCMC was 6000.000 and the first 1,000,000 cycles were discarded for reliable sampling. The GCMC simulations reproduced the characteristic behaviors of the adsorptions of N2 and CO2 by Zn(BDC) under pressure, indicating that the adsorbing site to gas is the capillary structure. However, numbers adsorbed by them were 3 and 1.7 times the corresponding experimental values for N2 and CO2, respectively [74]. These inconsistencies were ascribed to the unsaturated adsorption in the crystal and others such as force fields and charges employed, indicating the utility of GCMC for other adsorption systems.

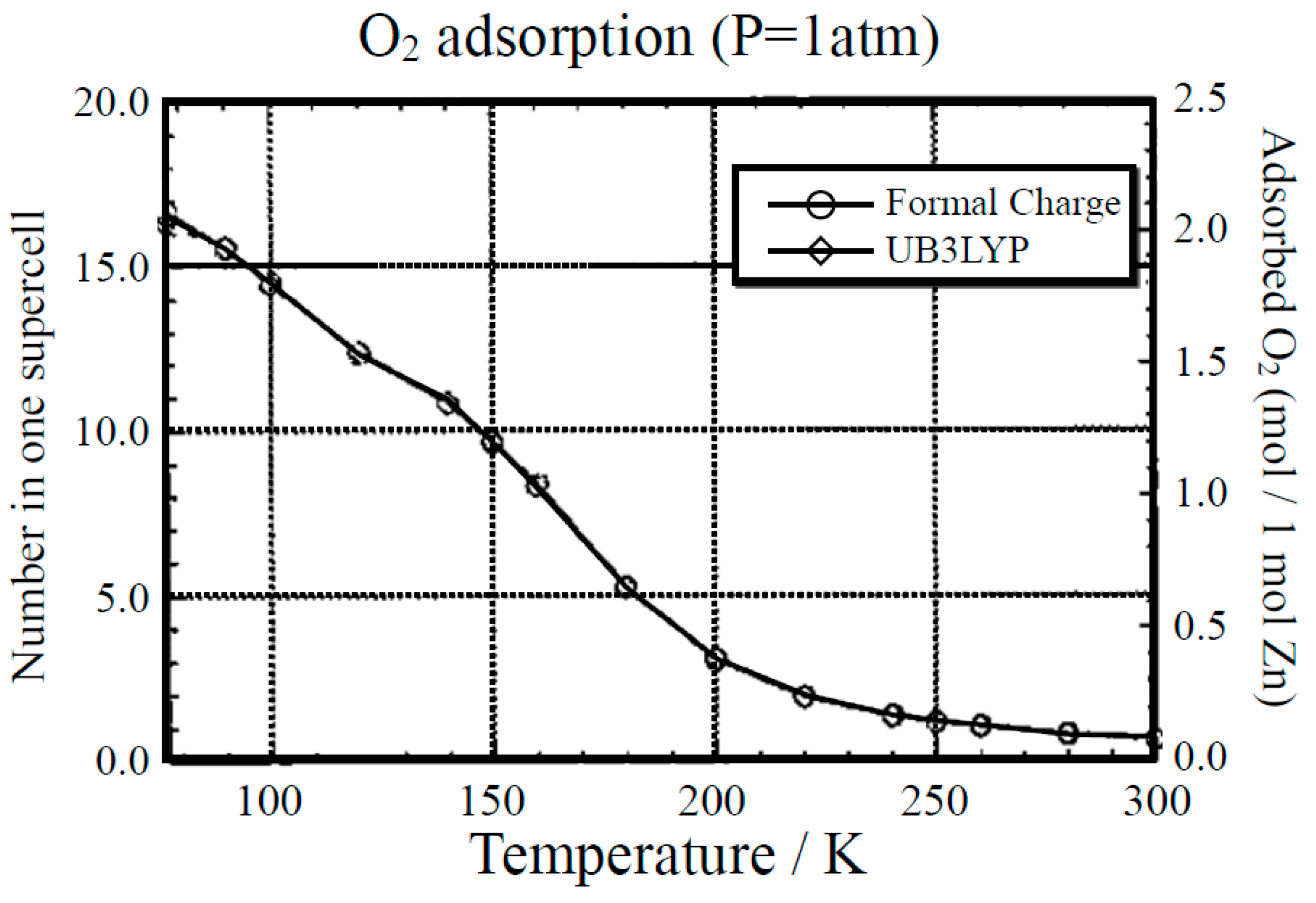

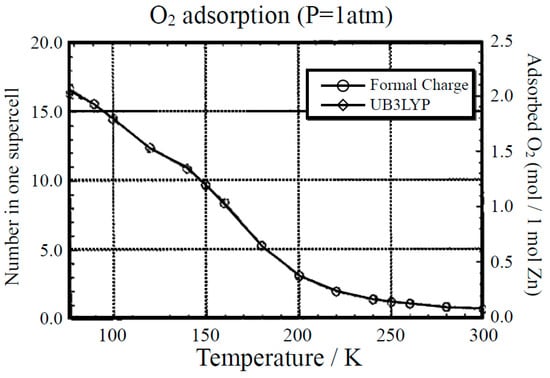

GCMC calculations were also performed for elucidation of the adsorption process of O2. Figure 10 illustrates the variation of adsorption number of O2 in one supercell against the temperature at 1 atom pressure. From Figure 10, the adsorption decreases gradually over 200 K and becomes close to zero above 250 K. The saturated value reaches about 2.0 mol of O2 per 1 mol of Zn at T = 77 K and it is about 1.7 times as large as the experimental value [72,73]. Thus, magnetic molecules such as O2 can be adsorbed within the cavity of Zn(BDC) at a low temperature even at 1 atom [43]. This means that MOFs can be used for confinement materials of open-shell molecules as in the case of closed-shell molecules such as CO2.

Figure 10.

Monte Carlo (MC) computational results for the temperature dependence of the amount of adsorbed O2 molecules by the Zn(BDC) crystal at 1 atom [43]. Two different charge populations were used for the MC computations.

5.3. Molecular Mechanics and Quantum Chemistry Calculations for Open-Shell Systems

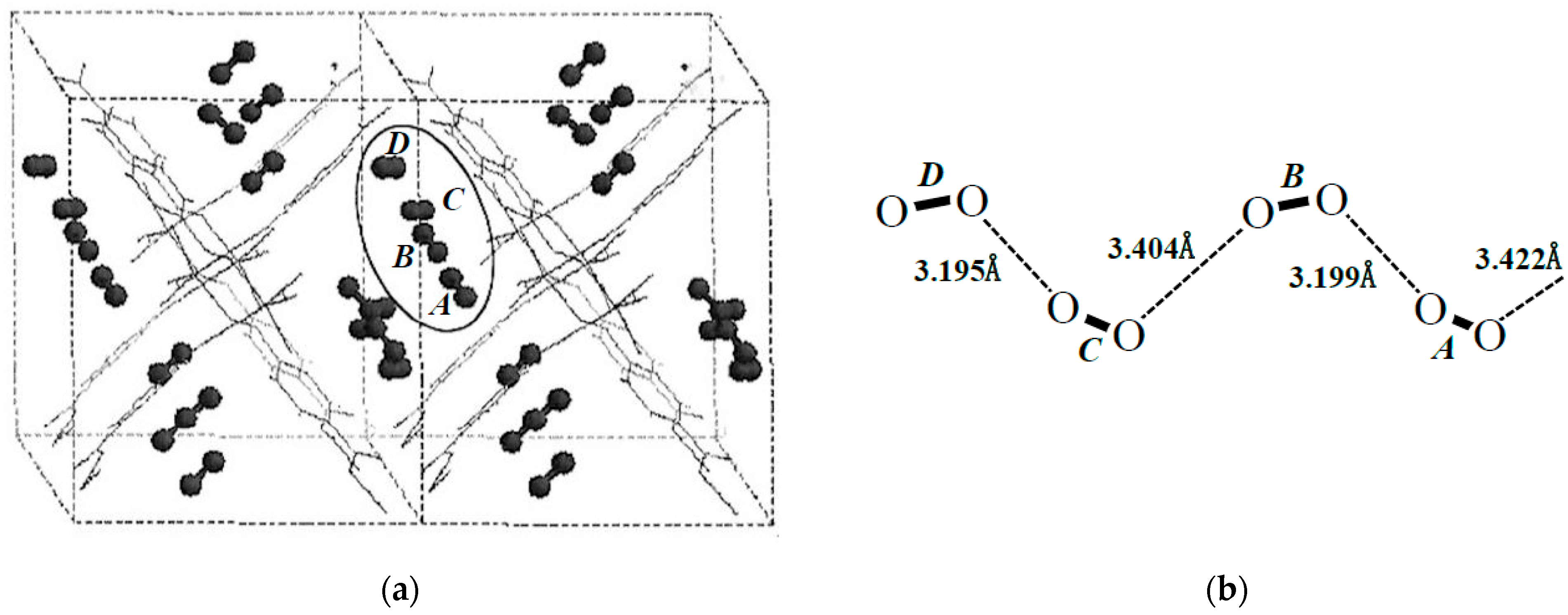

There are many O2 molecules within the cavity of Zn(BDC) [43], depending on the temperature. However, 1D alignment of open-shell molecules may be feasible if sizes of the adsorbents are selected so as to fit the size of porous holes. To elucidate such a possibility, molecular mechanics (MM) calculations were performed to search for a possible one-dimensional (1D) alignment of O2 molecules as shown in Figure 11 [43]. One of the O2 alignments optimized by the MM method is illustrated in A of Figure 11 like Figure 7b. The non-uniform zig-zag chain of O2 molecules is shown in (b) of Figure 11. Geometrical fluctuations of O2 molecules in the chain were also examined on the basis of potential curves obtained by BS DFT calculations [43]. The effective exchange interactions by BS DFT and UCCSD(T) were negative in sign in the stable conformations [43], indicating the antiferromagnetic character. However, the uniform alignment of O2 molecules was impossible to obtain due to the Haldane spin system [17] in the cavity of Zn(BDC).

Figure 11.

Structures of adsorbed oxygen molecules. (a) The chain configuration of oxygen molecules estimated by the molecular mechanics (MM) computations. (b) Intermolecular distances of 1D zig-zag line of oxygen molecules by the MM computation [43].

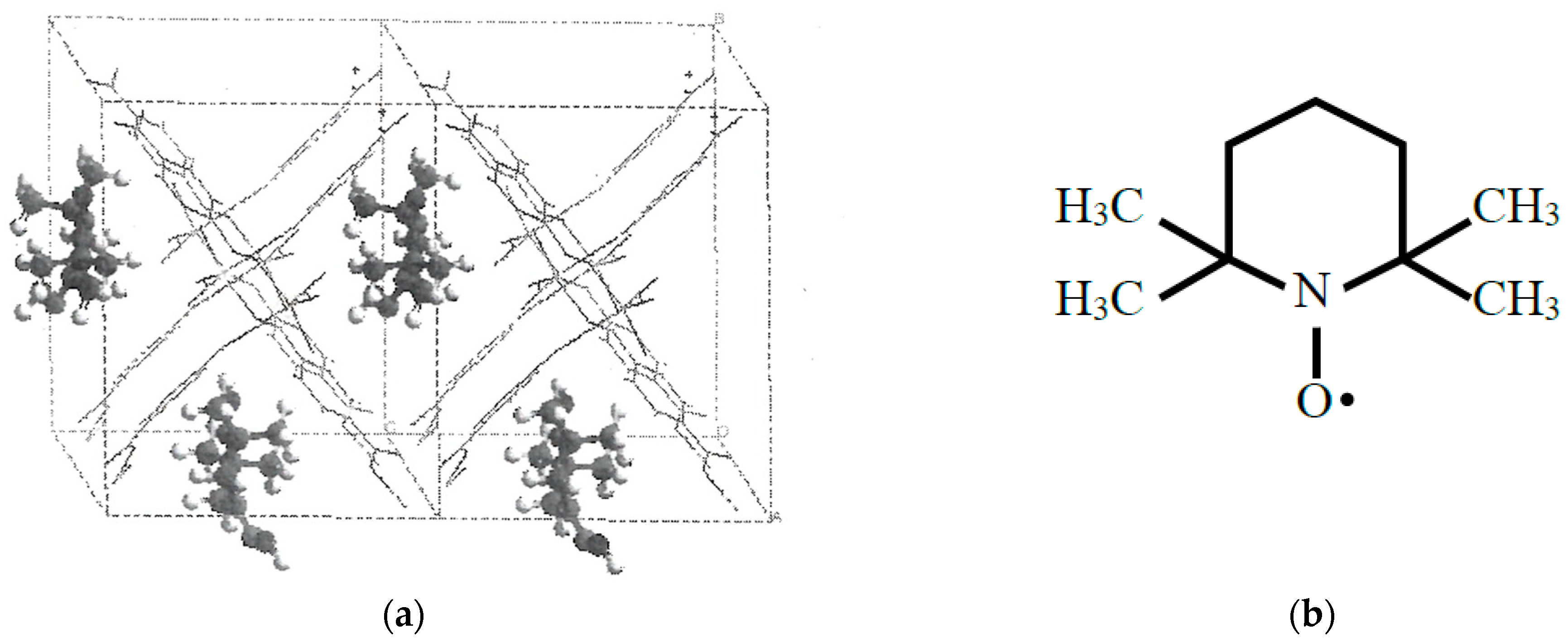

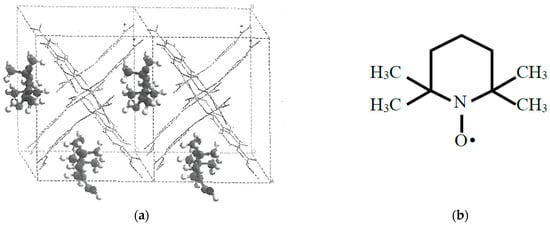

The above results have indicated that nanoporous organometallic conjugated (OMC) and MOF systems are useful for confinement and alignment of open-shell molecules with local spins. To this end, dimeters of these radical adsorbents are adjusted so as to fit the size of porous holes in porous OMC materials. For example, a 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPO) radical may be aligned in a line of the cavity as illustrated in Figure 12 [43]; see also Figure 2. 46 in ref. [38] and chapter 10 of the book [120]. Thus, through-space alignments of open-shell molecules with appropriate porous compounds such as MOFs are regarded as a possible chemical approach for realization of molecular quantum coherence states of open-shell molecules at a low temperature [78,120].

Figure 12.

(a) Possible alignment and confinement of TEMPO radical on the basis of the UB3LYP theoretical calculations [43] and (b) Molecular structure of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine 1-oxyl (TEMPO) radical.

6. Devices Constructed by Superconductor, Trapped Ion and Neutral Atom

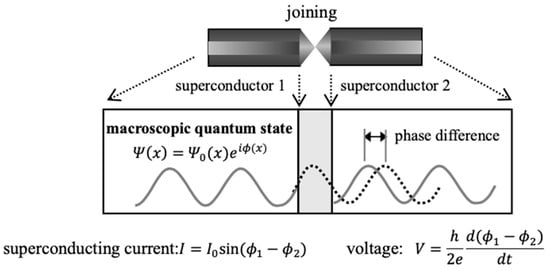

6.1. Quantum Tunneling of Mesoscopic Superconductor and Quantum Devices

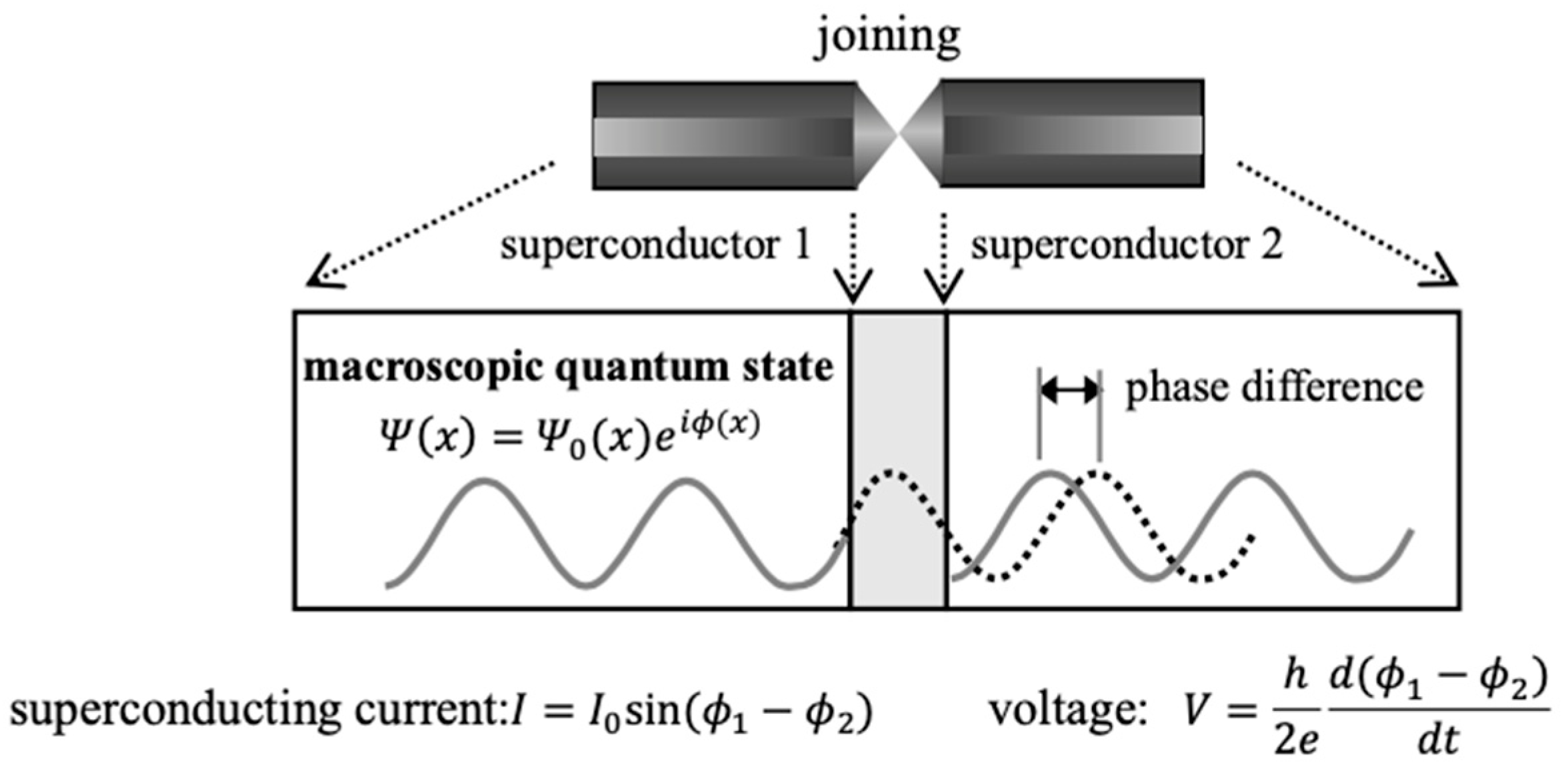

In this review, we have examined generation of coherent states of open-shell molecular aggregates by organometallic conjugation and organometallic confinement in chemistry [38,39]. Historically, macroscopic quantum coherence (MQC) and macroscopic tunneling (MQT) [36,40,44] in quantum mechanics have been observed for the Josephson coupling [125] between mesoscopic superconductors I and II consisting of a number of electrons as illustrated in Figure 13 [125,126,127,128]. Here, the term “mesoscopic” is used for an intermediate size between quantum and classical mechanics regimes although definition of the threshold between them is poorly defined as discussed in the well-known Schrödinger Cat problem [36,44,78,129]. The coherent states of mesoscopic superconductors are expressed by a single wavefunction of quantum mechanics as follows [125,126,127,128]:

where Ψ0(x) and Y denote the amplitude and quantum phase of a superconductor Y (Y = I, II) with a wave nature. The important role of the quantum phase has been examined in our previous reviews [78]. The relative phase is directly related to electron current (I) and voltage (V) of the Josephson coupling system [125,126] as follows:

where h is the Plank constant. The Josephson coupling [125] has often been constructed with aluminum superconductors for quantum computing [130,131,132,133]. Many other qubits have also been investigated recently [78].

Figure 13.

Josephson coupling system for mesoscopic superconductors 1 and 2 where denotes quantum phase [125,126,127,128]. The superconducting current and phase shift through the Josephson junction are schematically illustrated. Sizes of the superconductors 1 and 2 are in the following range: few mm–100 mm as a scale factor in Figure 1. Many experiments have been performed for elongation of the coherence time in Section 7 since gate operations for quantum computations are performed within the coherent time [130,131,132,133].

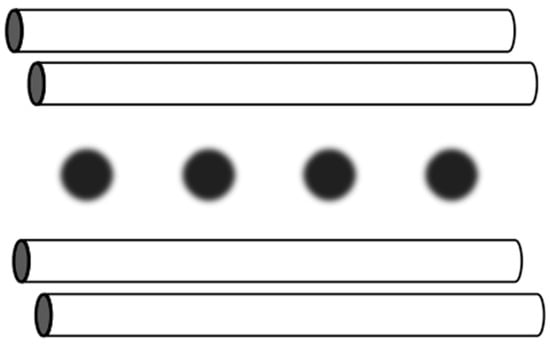

6.2. Trapped Ions by Electromagnetic Fields and Quantum Devices

Recently, as an alternative approach to superconducting qubits, through-physical alignments of open-shell atoms and molecules have been performed extensively. Over past decades, several physical methods [105,106,107] have indeed been developed for generation of coherent states of open-shell ions and atoms. Radio frequency (F) and static electronic fields [132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139] have been used for confinement and alignment of atomic ions such as Ca+ ion as illustrated in Figure 14. For example, a MOF for confinement of a linear chain in Figure 7a is formally replaced with four electrodes in the ion-trap system [134,135,136,137,138,139,140], indicating equivalent transformation between the trapping systems. Similarly, 2D chemical lattices for 2D spin alignments in Figure 7c are replaced with 2D surface-electrode traps in the ion-trap system [139]. Laser irradiations have been used for formation of excited states of the Ca+ ion for generation of qubits, usually 2S1/2-2D5/2 excitation, and its coherent state over a relatively long time is generated in the trapped-ion approach for quantum information processing [140]. Ion-trap methods have been developed for an effective approach to quantum computing [140].

Figure 14.

Schematic illustration of four linearly aligned ions such as Ca+ ions confined by the linear Paul trap in the trapped-ion system for information processing [140]. The endcaps are not shown in this figure. Chemical trapping in Figure 7a is equivalently transformed to trapping by electric fields.

Figure 14.

Schematic illustration of four linearly aligned ions such as Ca+ ions confined by the linear Paul trap in the trapped-ion system for information processing [140]. The endcaps are not shown in this figure. Chemical trapping in Figure 7a is equivalently transformed to trapping by electric fields.

6.3. Neutral Atoms Confined by Laser Fields and Quantum Devices

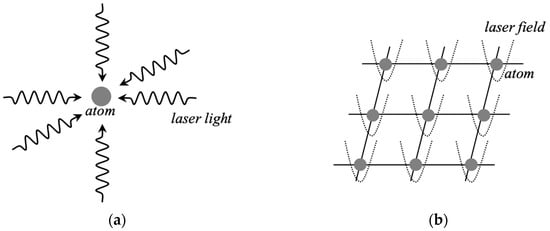

Magneto-optical methods [141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154] have been developed for confinement and alignment of a large number of neutral atoms such as Rb atoms in optical lattices (Figure 15). Optical tweezers [136,145] can generate several types of optical lattices such as square, honeycomb structures, etc. for confinements. Therefore, we can understand the equivalence transformation between MOF confinement materials in Figure 7 and the magneto-optical lattices as illustrated in Figure 14. The 1D and 2D confinement and alignment of neutral atoms are realized by the magneto-optical methods [141,142,143,144,145]. After the alignment, the Rydberg excited state of Rb atoms with a largely expanded electronic orbital [79] is generated by laser irradiation. The quantum bits can be formed with 5p-electrons and 43D Rydberg excited orbitals (43I) in this system. Therefore, the dipole–dipole interaction between these qubits becomes strong in the Rydberg excited state [143,144,145]. The interactions between excited neutral atoms confined in the lattice are used to generate entanglement states for quantum information processing [146,147,148,149]. Recently, error correction methods [149,150,151,152,153] have been developed in practical neutral-atom computing. Thus, physical and optical methods have been developed for generation of coherent states of atomic aggregates for quantum devices in quantum physics.

Figure 15.

(a) Schematic illustration of laser cooling of atom by the Doppler effect of laser fields; (b) two-dimensional (2D) lattice of neutral atoms trapped by the optical potentials of laser fields [141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154]. Chemical confinement in Figure 7c is replaced with the potential well by the optical lattice (b).

Figure 15.

(a) Schematic illustration of laser cooling of atom by the Doppler effect of laser fields; (b) two-dimensional (2D) lattice of neutral atoms trapped by the optical potentials of laser fields [141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154]. Chemical confinement in Figure 7c is replaced with the potential well by the optical lattice (b).

7. Quantum Coherence, Entanglement and Decoherence

7.1. Quantum Entanglements for Equivalent Transformation Among Different Systems

Several different systems have been discussed in this review, providing no apparent interrelationship between them. However, the concept of quantum entanglement is a common base for examinations and understanding of quantum mechanical properties of these quantum materials [78]. Here, we consider two level systems with two basic states |0> and |1> for lucid explanation of the entanglement [78]. They are, for example, the up-and down-spin states in quantum spin systems, two excited states of the Ca+ ion, the 5p and 4d electron pair in the Rb neutral-atom system, etc. The quantum qubit for these systems is generally expressed with the superposed state as

where α and β are complex variables satisfying the relation |α|2 + |β|2 = 1. This superposed state is a fundamental concept in the quantum information science under consideration. The well-known examples are the in- and out- of superposition states as

These states are responsible for the electron spins with x- and -x-directions as discussed in previous review articles [47,78]

Next, we consider the superposition states of two qubits A and B. These states are given by the direct product of A and B as

This state can be expressed with four basic configurations, |00>, |01>, |10> and |11>, as follows:

where α, β, γ and δ are complex mixing parameters, indicating 16 combinations in general. A specific superposed state with the same qubits (|0> or |1>) for A and B is given by

This superposed state |ψ>AB1 is one of the entangled states with the maximum quantum correlation between two qubits [129,141]. From Equation (19a), quantum entanglement means that the quantum state of each particle cannot be described independently of the state of the others, even when the particles such as spins are separated by a large distance; please remember the debates by Einstein with Bohr [22]. The situation is the same for spins with x and -x-directions after spin rotation, namely for |ψ>ABx. Thus, the entanglement is not lost for any spin rotated state in Equation (19b).

The density matrix is further introduced to express the quantum phase of qubits as follows [36,46,47,78,120]:

where pi denotes the probability of finding the pure state |ψi>. For example, the density matrix of the superposed state in Equation (15) is given by

where the diagonal terms denote the possibilities of this system for |0> and |1>, respectively.

Importantly, the off-diagonal terms in Equation (21) are responsible for the quantum coherence [36,46,78]. The coherence is sensitive to environmental conditions, often collapsing into a mixed state with zero off-diagonal terms, namely, a classical state via decoherence. For example, the singlet diradical pair formed in the dissociation process in Equation (1) provides two doublet radicals with no spin correlation because of the decoherence by environments. Thus, the long-time quantum coherence is crucial for quantum information processing as shown in Equations (13) and (14) [36,46,127,128,129,130,131,132,133].

7.2. Decoherence and Dynamical Decoupling in Physical Qubits

As mentioned above, coherence is a central concept for quantum processing [36,47,78]. Three maximum coherent states except for |ψ>AB1 are conceivable for a 2-bit system [21] as

The |ψ>AB4 state just corresponds to the singlet spin state responding to the dissociation process in Equation (1), indicating the recovery of the broken-symmetry (BS) via quantum resonance, namely the resonating BS (RBS) state like the RVB state [26]. However, singlet coherence is often destroyed with interactions with environments as mentioned above [47,78]. This in turn indicates the importance of suppression of decoherence for quantum processing. Thus, entanglement is a primary feature of quantum mechanics not present in classical mechanics. The four maximum entanglement states are denoted as the Bell states which are used for derivation of the Bell inequality for examination of scope and applicability of quantum mechanics [21] (see Appendix A).

Decoherence is a serious problem in a quantum system. Fundamental theories have been developed for emergence of the classical world from the quantum system with interaction of environments, elucidating several types of decoherence [155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164]. Here, such theories are applicable to two-state systems in this review in Equation (21). Over past decades, several methods for suppression of quantum decoherence have been investigated extensively. For example, dynamical decoupling (DD) methods have been proposed for this purpose [165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183] in the field of physical qubit operations. Dynamical decoupling (DD) indicates the necessity of developing effective procedures for suppression of decoherence in molecular qubit systems investigated in this review [160,161,162,163]. As shown in previous reviews [47,78], we can assume that the dynamics of a qubit plus environment is described by the Pauli matrix σz with qubit basis states |0> and |1> in Equation (4) [165,167] as

where the first and second contributions HS and HB describe the evolution of the qubit (S) and the environment (B), respectively, and the third term HSB describes a bilinear interaction between S and B. bk+ and bk are bosonic operators for the k-th field mode, characterized by a coupling parameter gk. The decoherence arises due to this coupling effect between the qubit and the environment. The state of the combined system (S + B) is represented by a total density operator tot(t). The reduced qubit dynamics for S is investigated by a partial trace over the environment degrees of freedom:

To modify the above decoherence process, a suitable time-dependent perturbation can be added to induce spin–flip transition for suppression of the unwanted spin inversion via the decoherent interaction.

where the second term denotes the DD term which is formally expressed by time-dependent variable V(t) ; note that the spin inversion Thus, the basic DD idea is that dephasing from the environment disturbance can be undone by the application of fast pulse control for spin inversion on the system. The DD procedure is indeed one of the effective methods for suppression of decoherence in physical qubit systems [160,161,162].

H(t) = H0 + HDD(t)

7.3. Chemical Decoupling of the Decoherence in Molecular Quantum Systems

The DD procedures indicated the importance of suppression of the decoherence of molecular quantum systems generated by bottom-up chemical technologies. The decoherence is mainly classified into population and quantum phase types expressed by the longitudinal spin relaxation time (T1) and the transverse spin relaxation time (T2), respectively, as shown in Equation (21) [47,78,164]. Previously [164], we have shown that the T2 values for spin dendrimers are variable, depending on their aggregate structures, namely chemical structural decoupling. Recently, several chemical decoupling (CD) methods have been investigated to suppress the decoherence in molecular qubit materials [175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183]. Phonon engineering for active control of the spin–phonon coupling in desired molecular structures has been found to be important for suppression of the decoherence among several methods examined [175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183]. Future developments of suppression procedures of decoherence are indeed crucial for molecular quantum devices.

7.4. Biological Decoupling of the Decoherence in Molecular Quantum Systems

The DD and CD methods are similar to the negative feedback in biological systems. Several kinds of quantum phenomena have indeed been observed for biological systems [184,185,186,187,188] as shown in our previous review [78]. For example, we may suppose that dynamic fluctuations of proteins may act to suppress the decoherence in quantum effects in light-harvesting systems [78]. Biological decoupling (BD) is briefly touched in the next section.

8. Future Prospects

Chemical synthesis of molecular quantum materials has been performed in the field of material chemistry. In the 1980s, extensive efforts were made to realize the long-range orders of open-shell molecules such as pure organic ferromagnets, etc. [96,97]. Discovery of the high-Tc superconductivity of copper oxides [19] opened the door for extensive investigations of strongly correlated electron systems (SCESs) because of the antiferromagnetism observed in copper oxides before doping [27]. The concept of isolobal and isospin analogies [30] has been proposed for design of p-d conjugated M–X (M = Ni, Co, Fe, etc.) systems like CuO2 planes. Superconductivities except for those of copper oxides [34,35,120,123] have been observed as shown in Table 3.

In the 1990s, quantum effects for low-dimensional systems [37] were accepted for developments of quantum memories and quantum computers [45,46,47]. To this end, several candidates for quantum bits (qubits) were proposed as shown in our previous review [47]. At the moment, a Josephson junction [125,126,127,128] of mesoscopic superconductors in Figure 11 has been used for this purpose. Recently, other methods such as ion-trap, neutral-atom methods, etc. have been investigated extensively [133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154].

Quantum effects in biological systems have been interesting targets for quantum biology. The chemical compass model is well known for magnetoreception in birds [184,185]. Quantum coherence of excitons in light-harvesting antenna systems for photosynthesis has attracted interest for rapid energy transfers for effective conversion of photon energy to chemical energy [186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194]. Several biological antenna systems with partial quantum coherence were examined in relation to developments of artificial bio-inspired systems [189,190,191,192,193]. Recently, it is shown that the mega-networks of tryptophan can exhibit a collective optical response in the UV region [195]. This may suggest operation of a kind of dynamical decoupling (DD) for decoherence by dynamical motion of protein in biological systems.

Molecular simulations [186,193,194] by using a quantum master equation have revealed that specific dendrimer structures such as fractal structures have been important for generations of efficient artificial systems for photochemical energy transfers [190,191]. On the other hand, Bose–Einstein condensation (BEC) for excitons [196] in artificial molecular systems has also been investigated for collapse–revival phenomena and generation of coherent states for molecular quantum information science. Thus, design of molecular structures for appropriate alignments is crucial for quantum coherence for molecular excitons [78]. Recently, the collapse–revival phenomena have been observed for mesoscopic quantum systems [197].

The quantum mechanical simulations in Section 5 suggest future chemical approaches for generations of coherent states of aggregates of open-shell molecules with spins and excitons of molecular systems. Organometallic conjugation (OMC) methods [38,39] may be used for through-bond alignments of molecular spins and excitons in 1D and 2D networks as illustrated in Figure 3. On the other hand, some metal–organic framework (MOF) systems [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] may be effective for through-space alignments of spins, excitons, etc. as illustrated in Figure 7. Judging from the DD procedures for physical qubits [148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163], several kinds of molecular DD effects are necessary for elongations of coherent times of molecular quantum materials generated by OMC and MOFs.

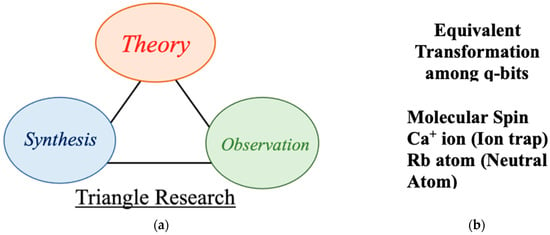

To this end, the triangle of research in our early project [38,39] in Figure 16, theory, synthesis and observation, are still useful as a guiding principle for developments of new molecular quantum materials in future. Equivalent transformations among four qubits: (i) atomic ions in a trapped-ion system, (ii) neutral-atom systems in the neutral-atom approach in solid-state physics and chemical approaches such as (iii) through-bond and (iv) through-space couplings of open-shell molecules in chemistry are necessary for developments of systematic theoretical views to obtain guiding principles as illustrated in Figure 16 [37,38,47,78]. Spin Hamiltonian models [101,102,103,104] have been used for theoretical treatments of these systems in a unified manner [198]. Chemical synthetic efforts are essential for realizations of new bio-inspired [198,199,200,201,202,203,204] molecular quantum systems in future. Various observations are also crucial for discovery and characterization of quantum effects for them.

Figure 16.

(a) Triangle research approach; theory, synthesis and observation for chemical approach to molecular materials in our project of the organometallic conjugation (OMC) from 1994–1996. Nowadays, the triangle of research is common in material science and engineering. (b) Equivalent transformations among qubits such as molecular spin, Ca+ ion, Rb atom (Neutral Rydberg atom), molecular exciton are feasible on theoretical grounds, providing guiding principles and important information for quantum material design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y.; Methodology, T.K., S.Y., M.T. and K.Y.; Investigation, T.K. and K.Y.; Writing – original draft, K.Y.; Writing – review & editing, T.K., S.Y., M.T. and K.Y.; Supervision, K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported with MEXT KAKENHI Grant Number JP22H04916 (K.Y.).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All the authors thank all the members of the specially promoted project of organometallic conjugation from 1994–1996 [37,40]. One (K.Y.) of the authors thanks J.S. Miller for helpful discussions on molecular ferromagnets, D. Gateschi for helpful discussions on low-dimensional quantum systems and J.-K. Shen for helpful discussions on biological decoupling. Numerical calculations were carried out under the support of the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Quantum Superposition and Quantum Entanglement in Quantum Mechanics

We could not include details of the historical developments of the fundamental concepts of the quantum superposition and quantum entanglement in the text. The superposition and entanglement [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12] have been fundamental concepts in quantum mechanics as shown in our previous papers [47,78,198]. The dual nature of particle and wave of quantum matter has been proposed on the theoretical ground [1,3,4] and has been examined by the double slit experiments in the first evolution of quantum mechanics. The modern double slit experiments have been carried out by using phase-coherent lights, electron beams and matter waves developed in the second evolution of quantum mechanics [205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217], demonstrating quantum interferences in Equation (21).

The name of the entanglement has been proposed by Schrodinger [129] in his famous Cat’s proposal, which is now regarded as an entanglement state of radioactive atom, chemical poison and Cat. The origin of the entanglement is also closely related to the EPR paradox [22] of Einsteins’ concept of local realism, which requires the local “hidden” variable of quantum particles such as photon and electron. Einstein [22] argued that the hidden variables should obey the condition of locality; namely the behavior for one particle (1) should not be able to instantly (over light speed) affect the behavior of another particle (2). However, this principle of locality was found to be wrong after several experimental examinations [20,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217]. The EPR paradox [21] has nowadays regarded as an early proposal of concept of the maximum entanglement state between two quantum components [21], namely the quantum correlations between quantum bits as shown in Equation (22). From Equation (22), the observation of the spin state of qubit 1 indeed induces the fixation of the spin state of qubit 2 because of the quantum spin correlations between them. Two spin models are applicable for any other system as discussed previously [47,78,198]. The concept of quantum entanglement is now a guiding principle for developing quantum materials and devices as shown in this paper.

Appendix A.2. Experimental Observations of Quantum Interferences of Quantum Matters

The quantum superposition in Equations (15) and (16) is the fundamental principle in quantum mechanics [198]. Jönsson [205,206] first performed the double slit experiment by using coherent electron beams. Merli et al. [207] also performed a related experiment using single electrons from a coherent electron beam. Tonomura et al. [208] developed the extremely stable, phase-coherent electron beams needed for good holographic imaging, a technique that enables measurements of both the intensity and phase [78] of transmitted electrons. They have successfully recorded the actual buildup process of the interference pattern with a series of incoming single electrons in the form of a movie. In their experiments [208], electrons incident on a wall with two slits pass through the slits and are detected one by one on a screen behind them, providing an interference pattern after successive accumulations of a great number of single electrons. The experimental interference pattern [208] was wholly consistent with that of Born’ probability rule [5].