Abstract

Some European Heavy Duty (HD) vehicle manufacturers have adopted Open Crankcase Ventilation (OCV) systems to improve reliability and performance. The emission compliance of HD vehicles both during certification and In-Service Conformity (ISC) testing need to also account for the crankcase ventilation. Despite that, the contribution of crankcase emissions to the overall emissions profile of modern trucks remains underexplored. This study experimentally characterizes the crankcase emissions of a Euro VI Step E HD truck equipped with an OCV system under controlled conditions on a chassis dynamometer. Emissions were measured over the World Harmonized Vehicle Cycle (WHVC) and an ISC-compliant driving cycle at two test cell temperatures. The results indicate that crankcase emissions account for up to 4% and 8% of the current regulatory limits for nitrogen oxides (NOx) and 23 nm solid particle number (SPN23), respectively. The tightening of NOx limits under Euro 7 regulations would increase these contributions to approximately 11%. SPN10 crankcase emissions were found to be on the order of 1011 (11% of the Euro 7 limit). Real-time SPN10 and SPN23 measurements revealed that the fraction of nanosized particles increases significantly during cold start, suggesting increased oil combustion within the cylinder. These findings highlight the need to refine crankcase emissions measurement procedures within regulatory frameworks. A systematic investigation of measurement setups and ageing effects, taking into account variations in OCV system designs and piston ring wear, is essential to determine whether characterization during certification is sufficient or if ISC testing throughout the vehicle’s useful life will be required.

1. Introduction

The continuous evolution of emissions regulations over the years has successfully curbed automotive exhaust emissions, contributing to cleaner and improved environment [1,2]. As tailpipe emissions have been progressively reduced, attention has shifted to other sources of vehicle-related emissions that are gaining relative importance, such as emissions from brakes and tyres [3]. This has driven regulatory authorities to broaden their scope, addressing these emerging sources to ensure continued progress in emissions control and environmental protection.

The vehicle’s crankcase has been identified as an important source of harmful pollutant, especially Particulate Matter (PM) [4,5]. Combustion gases that bypass by piston rings during the compression and power stroke, known as blow-by gases, generate positive pressure within the engine crankcase. Additional contribution to blow-by gases can come from other components connected to the crankcase, such as turbochargers, air compressors and valve stems. These can account for up to 40% of the total blow-by gases [6]. To prevent pressure buildup in the crankcase (which can lead to efficiency losses) the blow-by gas must be vented. In addition to combustion products, blow-by gases also contain oil mist from the crankcase, which, if left untreated, could significantly impact oil consumption. Early blow-by control systems primarily focused on recovering oil using various types of separators [5,7]. Once filtered, the blow-by gas can either be vented to the atmosphere through Open Crankcase Ventilation (OCV) or routed back to the intake system via Closed Crankcase Ventilation (CCV).

The use of CCV systems is universally adopted in light-duty applications, where their implementation is mandated by regulations. In contrast, heavy-duty applications often utilize OCV systems, as they are permitted and preferred to reduce maintenance demands over the extended operational lifespan of these vehicles. Over time, oil escaping the separator can lead to fouling of critical components such as the turbocharger and intercooler [7]. To address these challenges, European regulations permit OCV systems provided that crankcase emissions are included in the overall vehicle emissions compliance testing [8]. This regulatory flexibility ensures that crankcase emissions are accounted for while giving manufacturers the possibility to address performance and durability concerns linked to CCV systems.

Despite the increasing importance of crankcase emissions, there is limited information available in the literature. Most experimental studies have been conducted on older-generation engines with a primary focus on particulate matter (PM) emissions [8,9,10,11,12,13] due to the significant contribution of escaping lubricating oil in particulate mass. Recent research on Euro VI Step E [14] and China VI [15] technology engines has highlighted that Solid Particle Number (SPN) emissions can range from 1 × 1011 to 3 × 1011 #/kWh for the currently applicable 23 nm cut-off size, and up to 4 × 1011 #/kWh for 10 nm measurements required under Euro 7. However, the cited studies either provided no details on the experimental procedures [14] or lack a systematic approach [15], for instance regarding sampling location (e.g., CVS vs. tailpipe) and/or types of thermal treatment applied (catalytic stripper versus evaporating tube). Nevertheless, these findings suggest that emissions from open crankcase ventilation (OCV) systems could account for as much as 66% of the allowable Euro 7 laboratory SPN emissions limit (4 × 1011/6 × 1011; emission over Euro 7 SPN10 limit). There is even less information available regarding the contribution of blow-by gases to the gaseous pollutant footprint of diesel engines [10,13]. Existing studies have not identified any statistically significant impact of crankcase emissions on tailpipe gaseous emissions. However, the reported experimental uncertainty, while considered negligible at the time, was at levels as high as 25% of the Euro 7 laboratory NOx limits.

The UN Regulation 49 [16] requires that for OCV systems, crankcase emissions must be added to tailpipe emissions, either physically or mathematically, during all emissions testing, including Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS). However, it offers no guidance regarding the handling of blow-by aerosol, despite fundamental studies indicating that core soot particles coated with varying thicknesses of lubricating oil can form micron-sized particles [12,17]. These particles are more prone to inertial losses compared to their exhaust counterparts. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether these particles retain the charge of soot particles originating from the combustion chamber, suggesting that the material of the crankcase vent line could play a critical role. The temperature of the line may impact particles via evaporation or condensation of semi-volatile compounds. Additionally, pressure buildup may influence blow-by gas flow rates, potentially altering the relative contribution of crankcase emissions to overall exhaust emissions. This is particularly relevant for In-Service Conformity (ISC) testing, where on-board installation constraints pose challenges to effectively connecting the crankcase to the tailpipe. Such complexities may necessitate the mathematical inclusion of crankcase emissions during ISC tests. However, the regulatory approach is not explicitly defined. Perhaps more critically, blow-by flow is expected to increase over time due to piston ring wear, meaning that mathematically adding crankcase emissions from dynamometer tests of new engines may fail to accurately represent the real-world contribution of crankcase emissions in aged engines.

This study aims to present a comprehensive analysis of crankcase emissions from a Euro VI Step E truck equipped with an Open Crankcase Ventilation (OCV) system. Additionally, it seeks to evaluate the relative advantages of two approaches currently permitted under the regulations: sequential measurements during engine dynamometer testing combined with mathematical addition to In-Service Conformity (ISC) test results, and the integration of crankcase emissions into the tailpipe before the measurement point. The investigations were implemented on a chassis dynamometer to enable precise quantification of emissions. Parallel measurements were taken at the tailpipe both upstream and downstream of the crankcase vent line. This approach has the advantage of enabling real-time quantification of crankcase emissions, thus avoiding complications and uncertainties arising from potential changes in aftertreatment system performance during sequential tests. At the same time, it circumvents the need for direct characterization of crankcase emissions, which would require handling high concentrations of lube oil that could pose challenges for the instrumentation. The crankcase vent line was constructed from conductive corrugated stainless steel to prevent electrostatic losses of charged particles and heated to 110 °C (as the crankcase vent outlet temperature is typically lower than the engine oil temperature [12]). Specific tests were conducted to examine the effects of crankcase vent line wall temperature and ambient temperature on measured crankcase emissions. Emissions were characterized under a surrogate engine dynamometer type-approval test as well as a pre-defined ISC test cycle, allowing for the evaluation of potential impacts from different operating conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Vehicle

The tested vehicle was a 4 × 2 tractor. It was equipped with a 13 L, Euro VI step E certified diesel engine with a rated power of 500 hp. The engine was equipped with an open crankcase ventilation system. The reference work (Wref) over the World Harmonized Transient Cycle (WHTC) was calculated to be 34 kWh following the methodology described in regulation 595/2009 [18]. The truck had an accumulated mileage of 207.5 thousand kilometers at the beginning of the test campaign. Both, the fuel and urea tanks were filled at the start of the test campaign using commercially available diesel (fulfilling EN590 specifications) and diesel exhaust fluid, with no refueling required throughout the duration of the tests.

The engine operated on 5 W/30 lubricating oil recommended by the OEM, which was exchanged at the designated intervals. At the time of testing, the oil was approximately halfway through its service life before the next scheduled exchange. No dedicated oil exchange took place before the test campaign.

2.2. Test Cell

The measurements were performed at the HD vehicle laboratory of the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission, situated in Ispra (Italy) [19]. The laboratory features a four-wheel drive, two-axle roller chassis dynamometer in a climatically controlled room. Tests were performed at ambient temperatures of 10 °C and 23 °C.

2.3. Measurement Instrumentation

Two Advanced Particle Counters (APC model 489—AVL GmbH, Graz, Austria), each equipped with both a 10 nm (internal) and a 23 nm (external) Condensation Particle Counter (CPC) were used to measure Solid Particle Number (SPN) emissions. The exhaust was initially diluted in a chopper diluter operating at 150 °C directly at the sampling location and then thermally treated in a Catalytic Stripper (CS) maintained at 350 °C. A simple mixer diluter downstream of the CS, cooled the thermally treated aerosol, bringing it within the operating temperature range of the two CPCs. One APC (APC1) employed CPCs manufactured by TSI (TSI Incorporated, Shoreview, MN, USA) while the other (APC2) featured CPCs manufactured by AVL. Both APCs operated at low dilution mode with the same Particle Concentration Reduction Factor (PCRF) set at 500.

A dedicated data logger (UniCAN 3, CSM GmbH, Filderstadt, Germany) recorded engine speed, torque and fuel consumption from the Electronic Control Unit (ECU). The exhaust flow rate was measured with a 4″ Semtech (Saline, MI, USA) Exhaust mass Flow Meter (EFM).

NOx, CO, HC, CH4 and CO2 emissions were measured with two AVL AMA i60 (AVL GmbH, Graz, Austria) analyzers sampling directly raw exhaust, upstream and downstream of the point where crankcase emissions were fed to the tailpipe.

A TSI 4040 (TSI Incorporated, Shoreview, MN, USA) flowmeter was employed in dedicated tests to directly measure the flow exiting the crankcase ventilation.

2.4. Test Setup

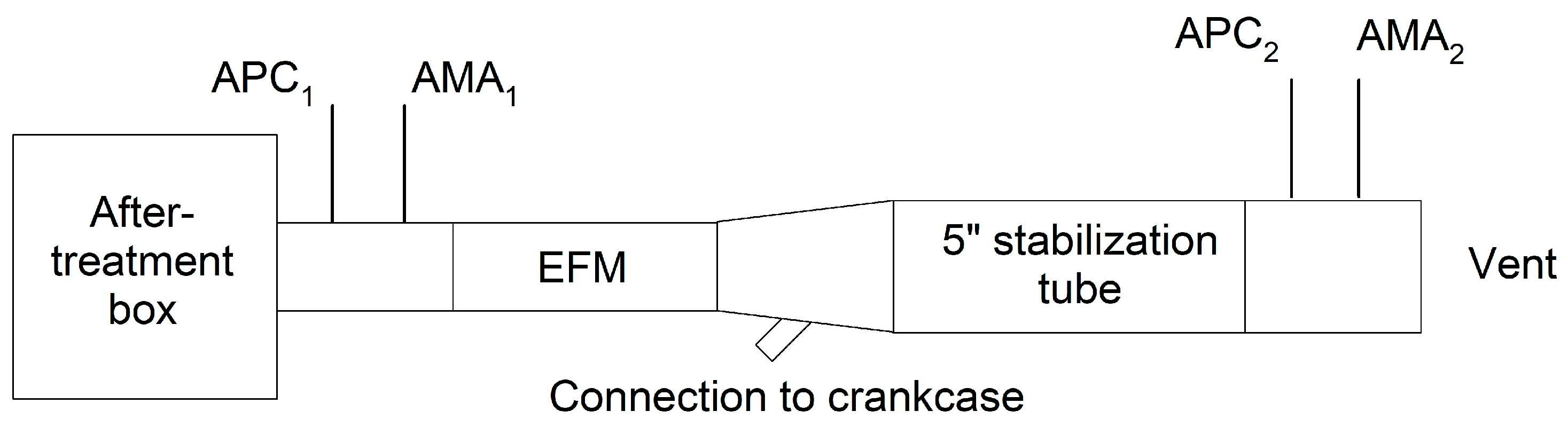

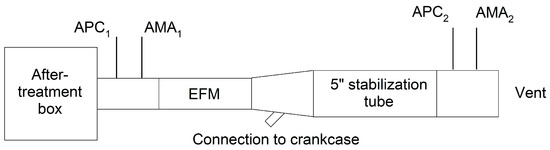

Figure 1 gives an overview of the experimental setup. The outlet of the aftertreatment box was connected to the EFM with a stainless metal tube of the same inner diameter (4″). Two sample probes were installed at the inlet of the EFM to connect APC1 (measuring particles) and the heated line for AMA1 (measuring gases). A 0.5 m long (4 mm inner diameter) stainless steel line, heated to 90 °C, was used to connect APC1 to the sampling probe. A diffuser was installed downstream of the EFM to expand to a 5″ tube. A stainless-steel connector of 40 mm inner diameter was welded on the diffuser for the return of the crankcase ventilation to the exhaust. The crankcase was routed to this connector via a 2 m long heated line made of corrugated stainless steel (40 mm inner diameter), allowing for operation up to wall temperatures of 200 °C. The total volume of this line was ~2.5 L, which at the average measured crankcase flowrate of 85 lpm, would correspond to 1.8 s residence time at ambient temperature. The second set of analyzers, APC2 and AMA2, were sampling downstream of a 1 m long and 5″ tube to allow for sufficient mixing of the exhaust and crankcase gases (~8 duct diameters). APC2 was also connected to the sampling probe via a 0.5-m-long (4 mm inner diameter) stainless steel line heated to 90 °C.

Figure 1.

Layout of the setup and instrumentation. APC = Advanced Particle Counter; AMA = exhaust gas (Abgas) Measurement and Analysis equipment; EFM = Exhaust Flow Meter.

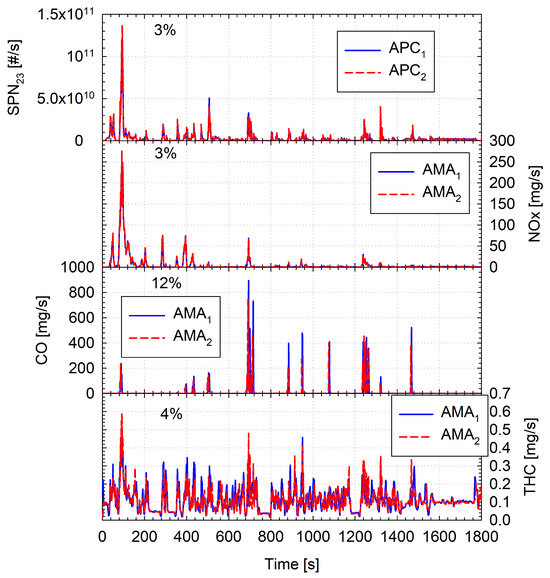

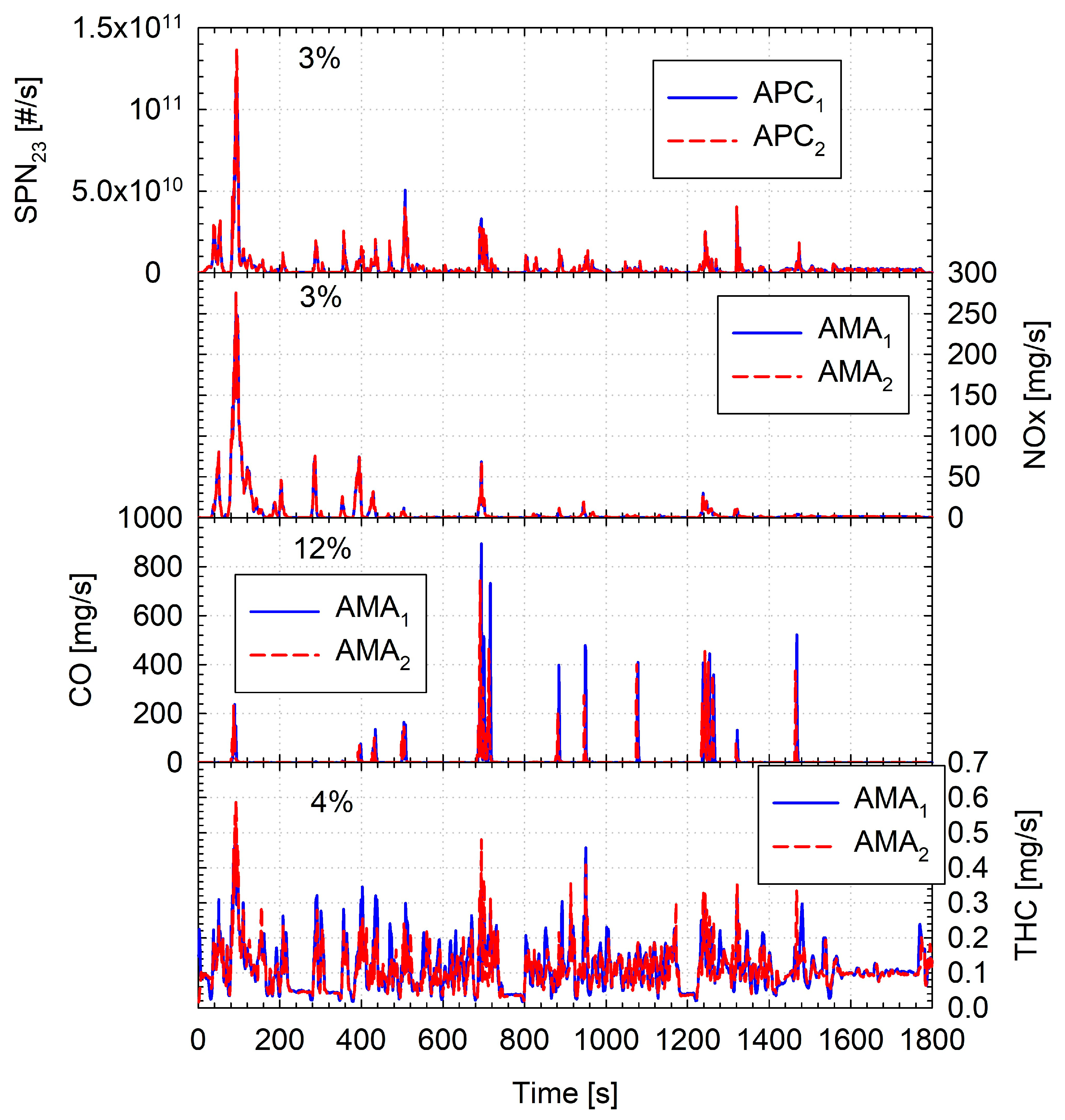

The instrumentation used in this study was calibrated at the required frequency intervals specified by the manufacturer, in accordance with regulatory requirements. To confirm the comparability of the measurement systems, a dedicated test was conducted with two APCs sampling at the same location upstream of the crankcase rerouting to the tailpipe, and two AMA analyzers sampling downstream. The two APCs demonstrated an agreement of 3%, while the gas emission measurements showed better alignment, with differences of 3% for NOx and 4% for THC (Figure A1). CO measurements exhibited cycle-average differences of 12%, with emissions appearing as spikes.

In some dedicated tests, before the start of the test campaign, a thermocouple was installed at the outlet of the crankcase ventilation to monitor the temperature of the vented crankcase gas. During the specific tests, the crankcase was connected to the TSI 4040 flowmeter through a 1.5 m long tygon tube of 30 mm inner diameter. A High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filter was installed at the inlet of the flowmeter to protect its flow measuring element.

2.5. Test Cycles

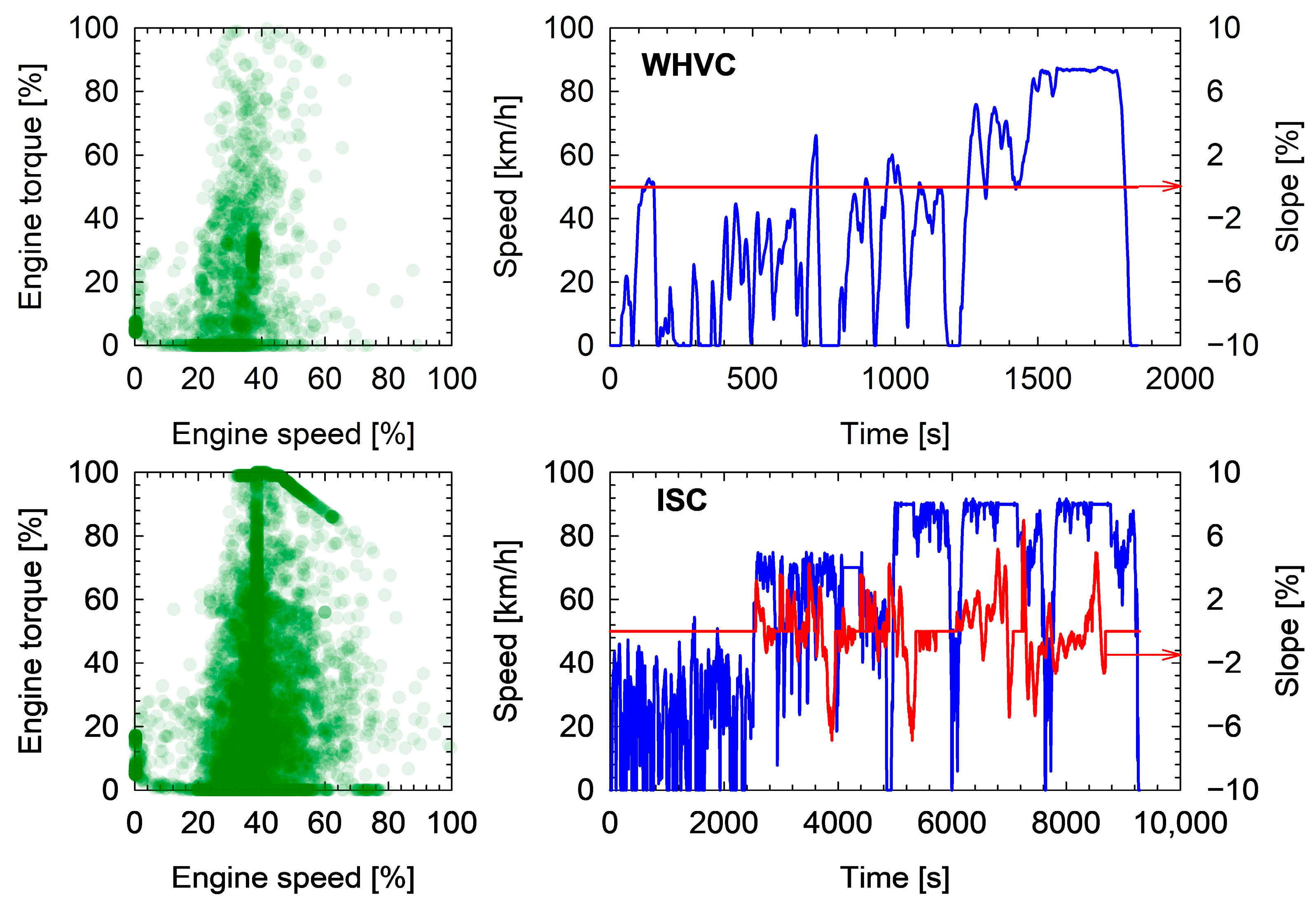

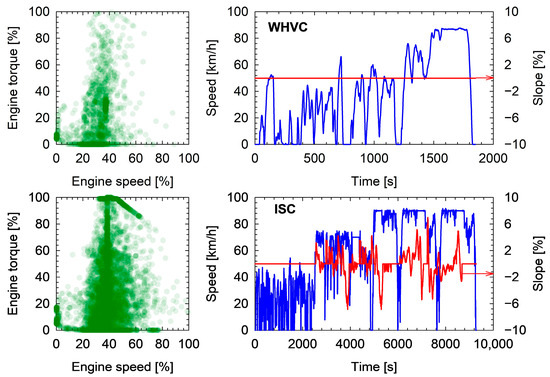

The truck’s crankcase emissions were evaluated using the World Harmonized Vehicle Cycle (WHVC) and using the speed and slope trace of an on-road In-Service Conformity (ISC) cycle for N3 class of vehicles on the chassis-dyno [19]. Despite being performed in the laboratory, the regulatory requirements are consistent with European Euro VI Step E standard [20]. This ISC-like cycle (hereinafter ISC) consists of a sequence of urban, rural and motorway segments with time-based shares of 27.1%, 26.4% and 46.5%, respectively, and average speeds of 22.9, 58.8 and 79.8 km/h. The WHVC is an implementation of the type-approval cycle (WHTC) on the chassis dynamometer. Figure 2 compares the velocity profiles and corresponding engine maps of the two cycles. All ISC tests were performed with the engine cold, in accordance with the regulation (i.e., coolant temperature < 30 °C). Both cold and hot versions of the WHVC cycle were performed. The latter required a brief highway drive before the start of the test to ensure the coolant temperature exceeded 70 °C.

Figure 2.

Operating engine maps (left-hand) and speed/slope profiles (right-hand) of the WHVC (top panels) and ISC (bottom panels) test cycles. Engine speed is normalized over the range from idle to maximum speed. ISC = In-Service Conformity; WHVC = World Harmonized Vehicle Cycle.

All tests were performed with a simulated payload corresponding to a gross vehicle weight of 29 tons, which corresponds to 66% of the maximum permitted laden mass (44 tons). At this payload, the total work over the ISC was calculated to be 225 kWh, equivalent to 6.6 × Wref. This value falls within the regulated range of 4 to 8 × Wref.

2.6. Test Sequence

Table 1 summarizes the sequence of tests performed along with the testing conditions. No specific conditioning protocol was implemented because the status of the aftertreatment system should not influence the crankcase emissions.

Table 1.

Test sequence.

2.7. Evaluation Methodology

2.7.1. Emissions Calculation

The concentrations of the measured pollutants were determined in accordance to the European regulations [18]. This included a dry-to-wet correction for CO and an ambient humidity correction for NOx. The APCs reported the measured concentrations adjusted with the calibrated PCRF and the calibration factors of the connected CPCs, and normalized the results to 0 °C and 1 atm. Exhaust flows were also normalized to the same conditions. The concentrations and exhaust flow rates were time aligned and subsequently multiplied to calculate the instantaneous emission rates in s−1. Brake power was calculated using the engine speed and torque signals provided by the ECU. No adjustment was made on the exhaust flow downstream of the crankcase return point, as the contribution was less than 1% (Section 3.2).

Aggregate results were reported in accordance with Euro VI Step E [20] and Euro 7 [21] regulations. The WHVC cycles were used as surrogates for the type-approval WHTC cycles. Accordingly, WHVC results are presented as cycle-average brake-specific emissions, calculated by summing the instantaneous emission rates over the entire cycle and dividing by the total brake work. The regulatory weighting factors of 14% for WHVC cold results and 86% for WHVC hot results are applied when comparing the emissions to the applicable limits.

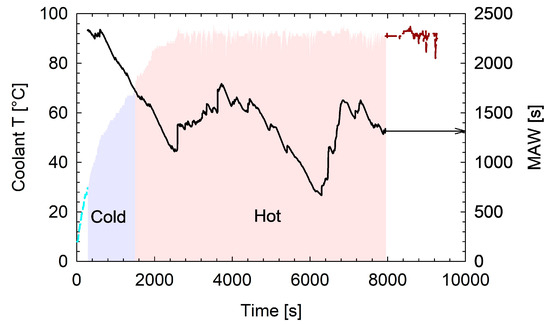

The aggregate ISC results were calculated according to the Moving Average Window (MAW) methodology [20]. Evaluation started once the coolant temperature exceeded 30 °C (Figure A2). The moving average windows (MAWs) were generated by incrementing the window length in 1-s intervals, with each window adjusted to ensure the brake work within the window matched the reference value, Wref. During testing, the time taken for the coolant temperature to rise from 30 °C to 70 °C was consistently less than 10 min. As a result, the cold start phase was defined as the set of MAWs where the coolant temperature ranged between 30 °C and 70 °C. The remaining MAWs were classified as the hot start phase. All MAWs were included in the analysis, as the average power across these windows exceeded 10% of the rated power. In total, approximately 8000 MAWs were calculated, with around 10% assigned to the cold start phase at 23 °C ambient temperature and about 16% at 10 °C ambient temperature. Emissions during the cold start phase were determined based on the 100th percentile of the cold start MAWs, while the hot start phase emissions were calculated using the 90th percentile of the hot start MAWs. To derive the final regulated emission result, a weighting factor of 14% was applied to the cold start emissions and 86% to the hot start emissions. This result was then compared to the emission threshold calculated from the applicable conformity factor for Euro VI Step E (1.63 × 6 × 1011 = 9.78 × 1011 #/kWh) and the Euro 7 emission limit (9 × 1011 #/kWh).

2.7.2. Propagation of Error Calculations

Some error propagation calculations were performed to demonstrate the advantage of conducting paired tests, where crankcase emissions are derived from parallel measurements taken upstream and downstream of the crankcase return. For paired tests, crankcase emissions were simply calculated as the difference between the upstream and downstream emission rates, with measurement uncertainty determined as the standard deviation across repeated tests. The alternative approach involves conducting repeated tests upstream followed by repeated tests downstream. In this case, the measurement uncertainty for the crankcase emissions would be calculated as the square root of the sum of the squares of the standard deviations of the upstream and downstream measurements. In both approaches, the measurement uncertainty for the weighted cycle result was calculated as the square root of the sum of the squares of the standard deviations of the cold and hot results, each multiplied by their respective weighting factors, i.e., s = sqrt((0.14 × scold)2 + (0.86 × shot)2).

3. Results

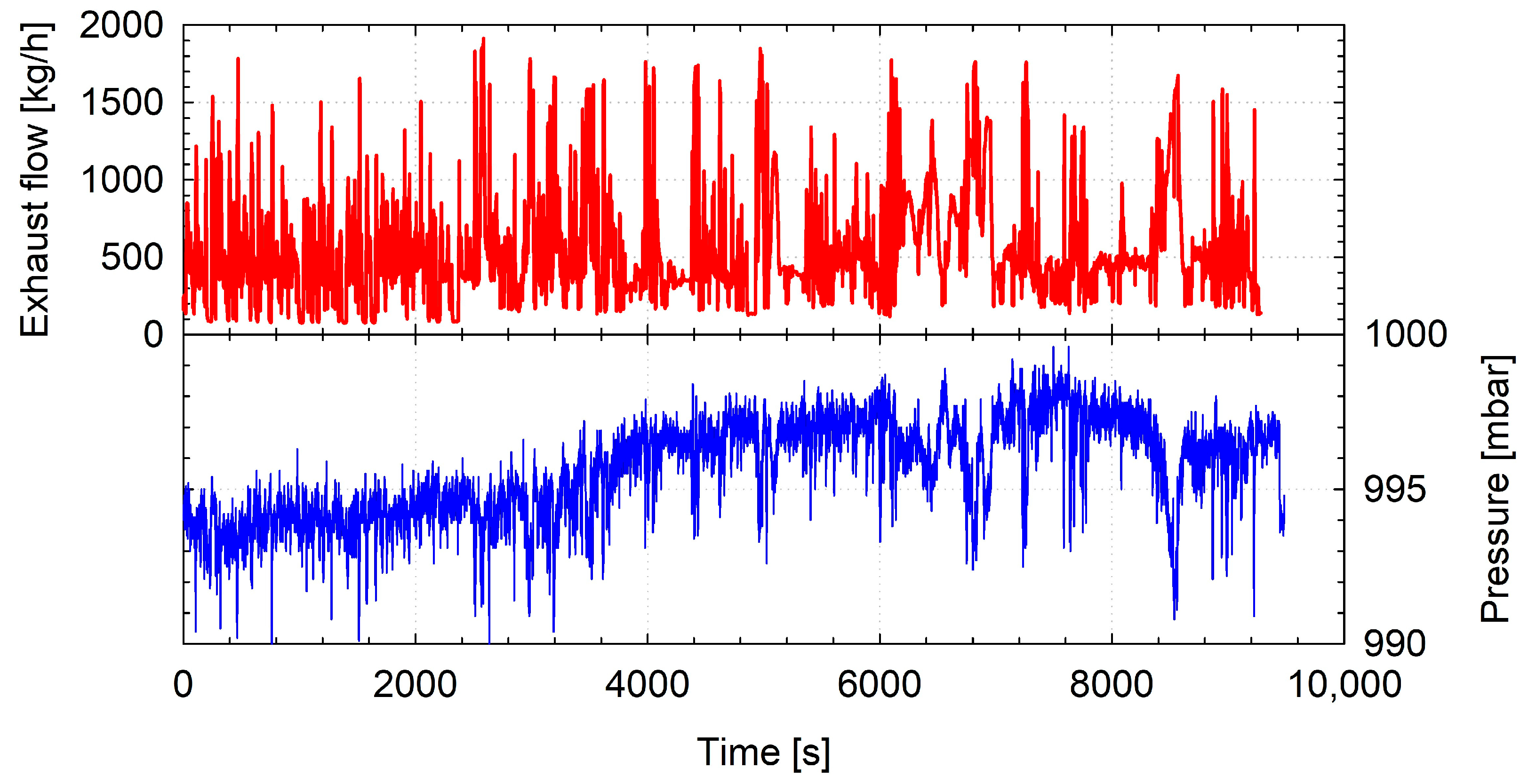

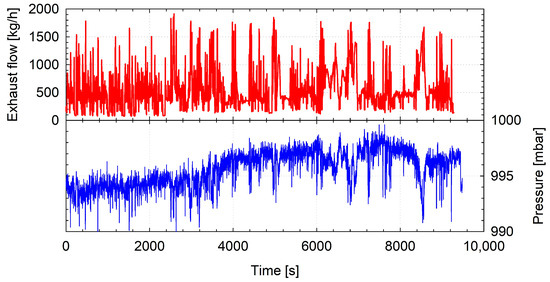

3.1. Verification of the Experimental Setup’s Non-Interference on Crankcase Ventilation

The experimental setup was designed with a focus on minimizing any potential impact on the crankcase ventilation system. Particular attention was paid to limiting backpressure caused by the setup. For instance, Figure 3 shows the measured absolute pressure at the sampling point upstream of the Exhaust Flow Meter (EFM) during an ISC cycle. During the test, the ambient pressure was 994 mbar, and the pressure variations induced by exhaust flow rate fluctuations were minimal, remaining below 6 mbar. As the crankcase ventilation system was positioned downstream of the EFM, the setup’s is expected to have even less influence on the crankcase ventilation.

Figure 3.

Exhaust mass flow (top) and absolute pressure (bottom) at the sampling point upstream of the Exhaust Flow Meter (EFM).

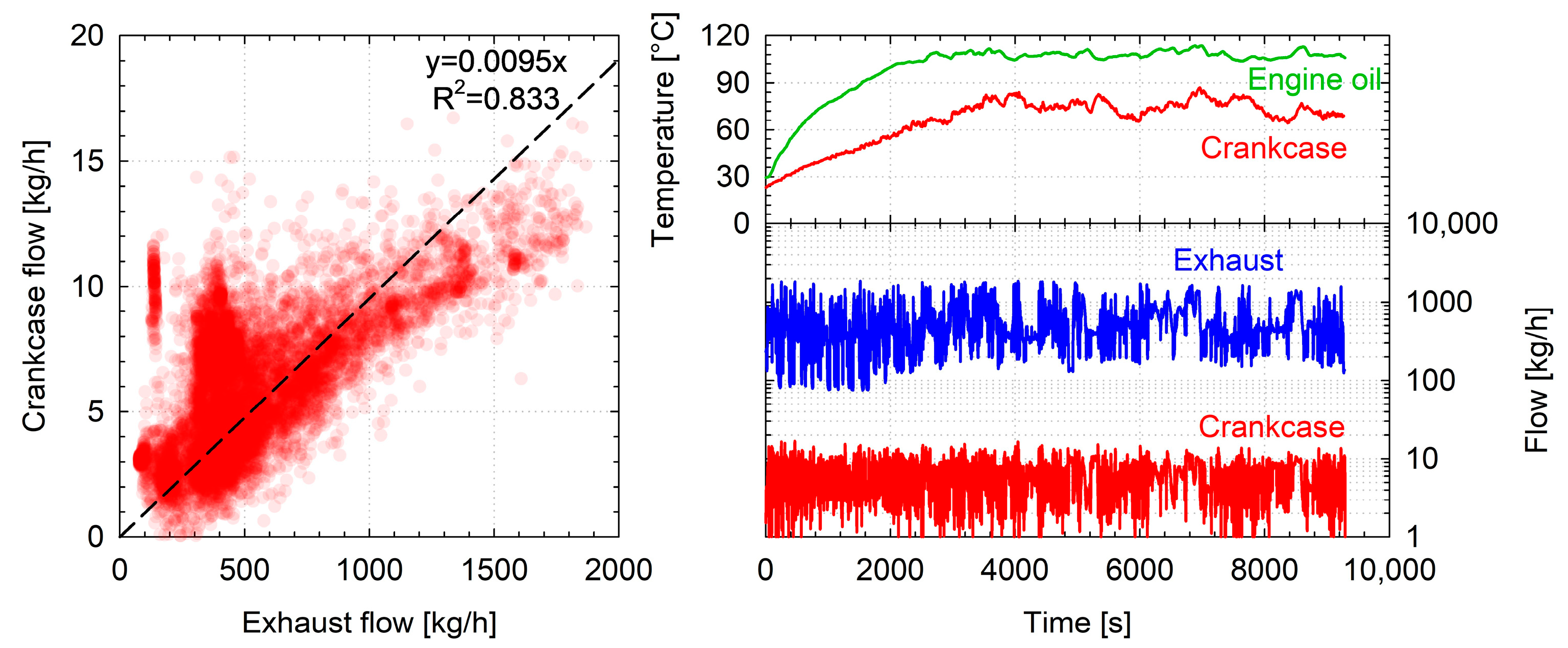

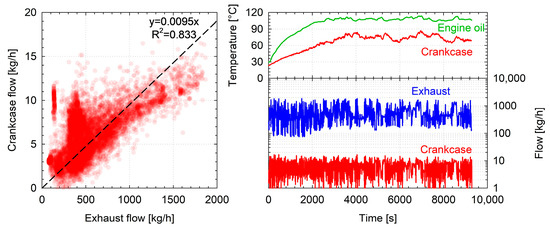

3.2. Crankcase Flowrate and Temperature

Figure 4 compares the measured crankcase and exhaust flowrates over an ISC cycle. The crankcase flow was found to correlate well with the exhaust flow. In absolute terms it was approximately 1% of the exhaust flow, averaging at 6 kg/h. The measured flows were found to be in good agreement with previously published data. Crankcase flows from four US HD trucks tested under various steady-state modes, were reported to range between 1 and 6.5 kg/h, corresponding to 0.2 to 1.5% of the exhaust flow [12]. Similarly, another study reported an average crankcase flowrate of 6.1 kg/h for a 14.6 L diesel truck tested on a chassis dyno over the EPA Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule [10].

Figure 4.

(Left panel): correlation between exhaust and crankcase flow over the ISC cycle. (Right panel): Real time traces of engine oil and crankcase outlet temperatures (top) and real time traces of exhaust and crankcase flows (bottom) over the same test cycle. ISC = In-Service Conformity.

The temperature at the outlet of the crankcase was found to peak at ~90 °C, being approximately 30 °C colder than that of the engine oil. The measured temperature is within the range of previously reported crankcase temperatures (50–90 °C [5]).

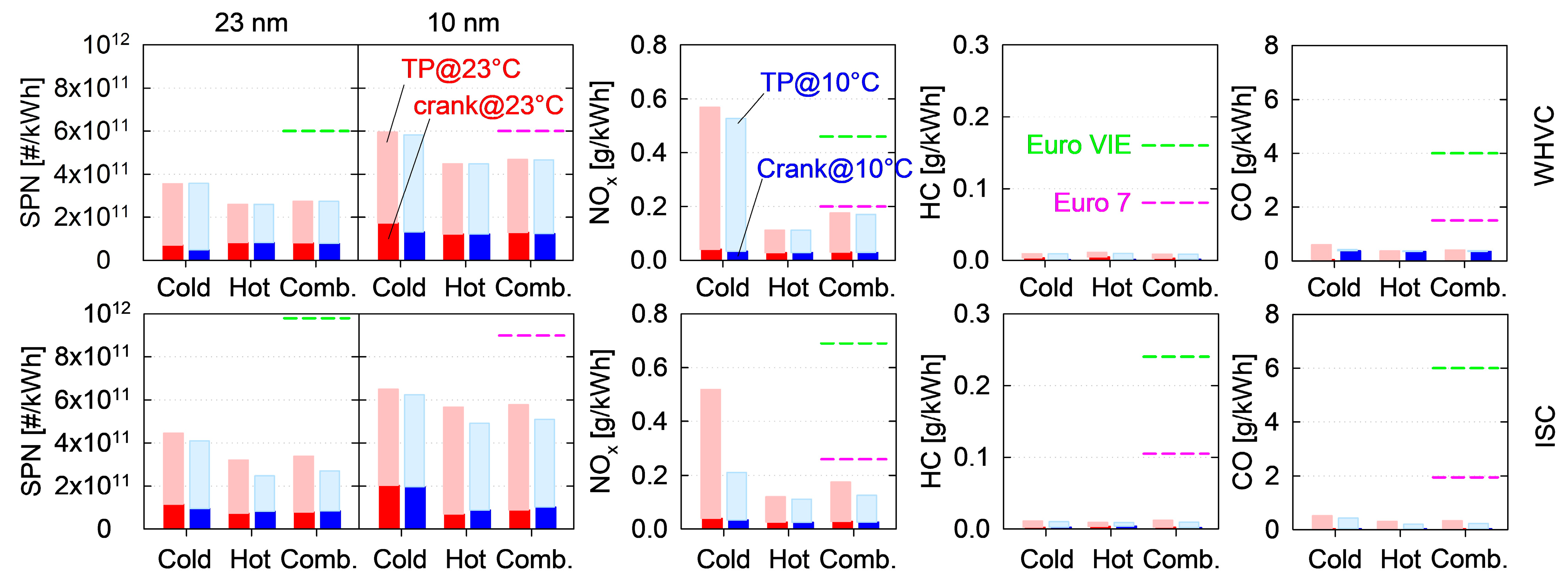

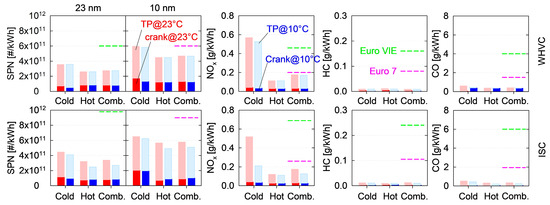

3.3. Emissions Summary

Figure 5 provides an overview of the vehicle emissions, distinguishing between tailpipe emissions (light-colored bars) and crankcase emissions (dark-colored bars). The measurements confirmed that, under the tested conditions, the vehicle is fully compliant with Euro VI Step E regulations, even with crankcase emissions experimentally accounted for. Moreover, the vehicle would meet the Euro 7 limits as well. It should be emphasized, however, that the testing conditions were not designed to challenge the vehicle’s compliance but rather to characterize crankcase emissions. Furthermore, the tested DPF had accumulated approximately 200,000 km of mileage. As a result, the accumulated ash within the filter is likely to have contributed to a significant improvement in filtration efficiency [22,23].

Figure 5.

Summary of the tailpipe emissions (light-colored bars) and the contribution of crankcase (dark-colored bars). Red and blue bars correspond to the average emissions for WHVC (top panel) and ISC (bottom panel) tests conducted at ambient temperature of 23 °C and 10 °C, respectively. The green and pink dashed lines indicate the applicable Euro VI step E and Euro 7 limits, respectively. Crank = Crankcase; ISC = In-Service Conformity; TP = Tailpipe; WHVC = World Harmonized Vehicle Cycle.

No effect of ambient temperature was observed on the overall vehicle emissions when testing either at 10 °C or 23 °C. Thermocouple data indicated that the SCR temperature reached 200 °C (typically the activation point for diesel exhaust fluid dosing) within a similar timeframe (~210 s) for both test cell temperatures. Consequently, NOx emission profiles were comparable across the two ambient temperature conditions investigated. The substantially lower cold start results for the ISC test conducted at 10 °C is due to the regulatory requirement for a minimum coolant temperature of 30 °C. This requirement effectively excluded the first ~280 s of operation (compared to ~45 s at 23 °C), during which most of NOx is emitted because the SCR is not active. If the MAW analysis had started from engine ignition, the 100th percentile results at 10 °C would have been approximately 20% higher for SPN, 30% higher for CO, 10% higher for THC, and 2.7 times higher for NOx.

Crankcase emissions were largely unaffected by the ambient temperature. On average, the crankcase contributed approximately ~0.8 × 1011 #/kWh SPN23, ~1.2 × 1011 #/kWh SPN10, 30 mg/kWh NOx, 30 mg/kWh CO and 2.5 mg/kWh THC. The gaseous emissions associated with the crankcase are expected to originate directly from blow-by gases escaping the combustion chamber and being emitted into the atmosphere, bypassing the aftertreatment system entirely

An increased formation of sub-23 nm particles was observed over cold start WHVC and ISC, with SPN10 reaching as high as 2 × 1011 #/kWh. The cold start and hot start emissions over the WHVC were found to be comparable, whereas 100th tile results exceeded 90th tile results during the ISC cycle. Ultimately, the weighted results for 23 nm particles were similar between the two cycles, while the weighted emissions for 10 nm particles were 30% lower over the ISC cycle compared to the WHVC. In the context of current and upcoming emission standards, SPN and NOx emissions from the crankcase are expected to be of importance.

The brake-specific crankcase SPN emissions would correspond to an average particle concentration in the crankcase vent line of approximately 2 × 106 #/cm3. At such concentrations, the coagulation rates are expected to be negligible within the residence time inside the vent line. Polydisperse coagulation calculations indicate less than a 1% change in particle concentration [24].

4. Discussion

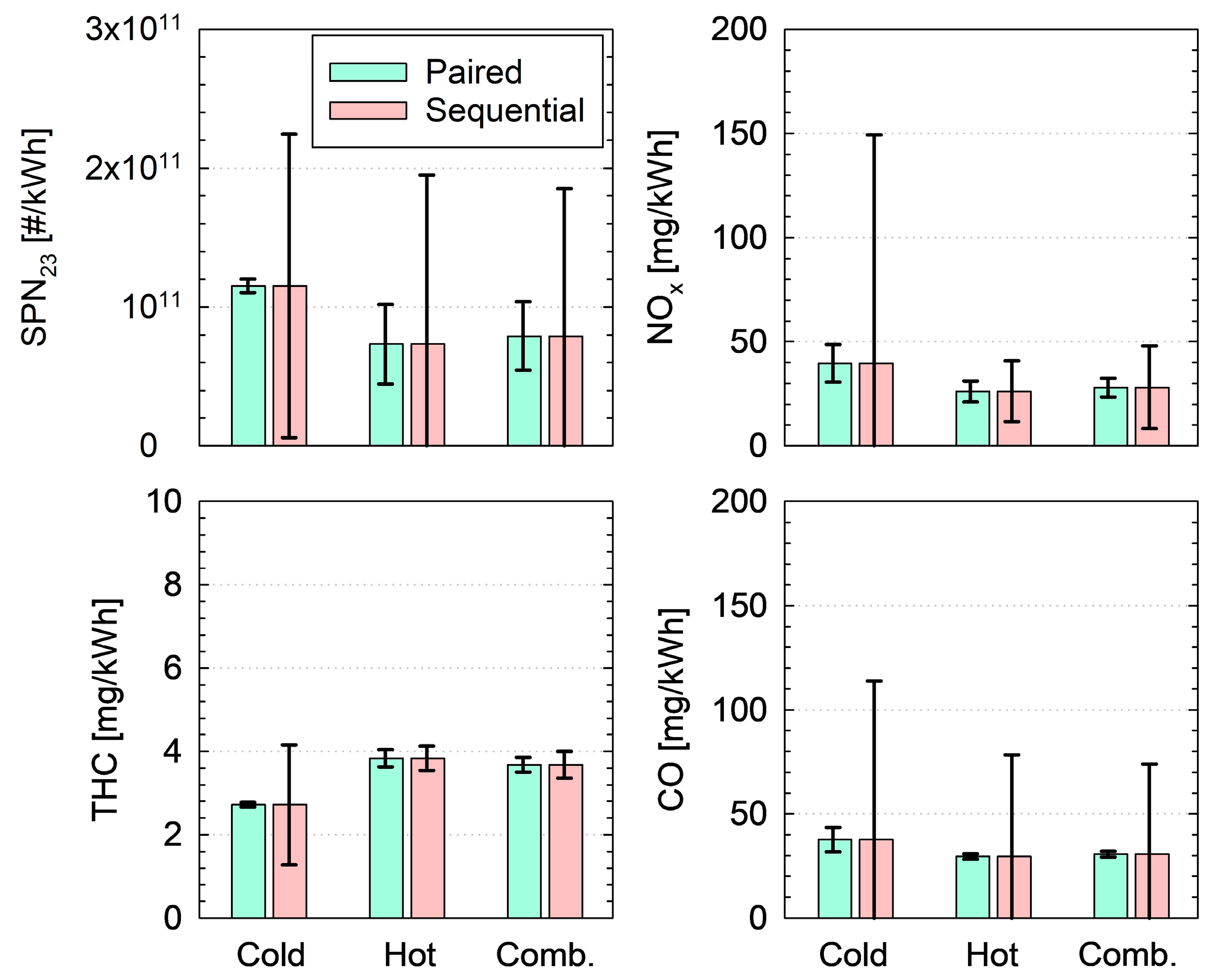

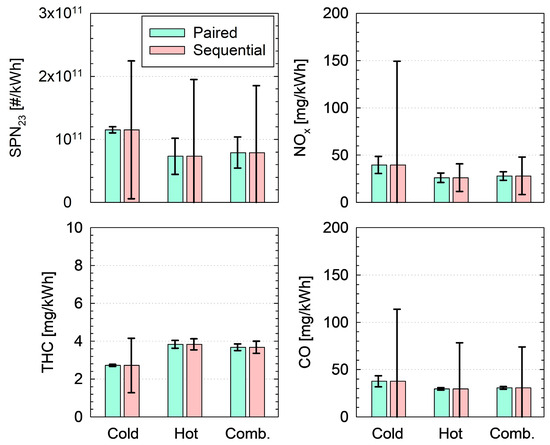

4.1. Accuracy of the Measured Crankcase Emissions

One of the most common methods for quantifying crankcase emissions involves repeated measurements, wherein the crankcase ventilation is alternately connected and disconnected upstream of the sampling point [14]. The main challenge with this approach lies in the test-to-test variability, which can influence the inferred crankcase emissions. This effect was quantified using the crankcase emission results from three repetitions of the ISC cycle at an ambient temperature of 23 °C and a crankcase vent line wall temperature of 110 °C. The analysis assumed that the upstream and downstream measurements were performed sequentially rather than in parallel, as outlined in Section 2.7.2.

Figure 6 compares the results using the two approaches for the pollutants targeted in the current Euro VI Step E regulation. In terms of absolute levels, both approaches produced equivalent results. However, the experimental uncertainty associated with the sequential measurements was significantly higher, making it practically impossible to draw any statistically significant conclusions about the actual level of crankcase emissions. Conversely, the results indicate that parallel upstream and downstream measurements enable the quantification of emission levels as low as 3 × 1010 #/kWh, 9 mg/kWh, 6 mg/kWh for SPN23, NOx and CO, respectively, with the instrumentation employed. Although the alignment of the measuring instruments was carefully considered, the potential effect of ±1 s misalignment between the exhaust and analyzer signals was investigated (Figure A3). This would have resulted in less than ±5% variation in SPN, NOx, and THC results, and ±10% variation in CO results. From this perspective, redirecting crankcase emissions to the tailpipe during ISC testing would not only account for the potential deterioration of crankcase emissions due to aging piston rings but also eliminate the uncertainties associated with sequential measurements required for quantifying the contribution of crankcase emissions.

Figure 6.

Crankcase emissions over the ISC cycle tests performed at a test cell temperature of 23 °C, with the crankcase vent line heated at 110 °C. The bars represent the average of three tests, while the error bars indicate the measurement uncertainty, calculated as described in Section 2.7.1. Results based on the difference between measured emissions downstream and upstream of the crankcase return of each individual test are shown with green bars. Red bars correspond to results obtained by calculating the difference between the average of the three repetitions downstream and the average of the three repetitions upstream of the crankcase return. ISC = In-Service Conformity.

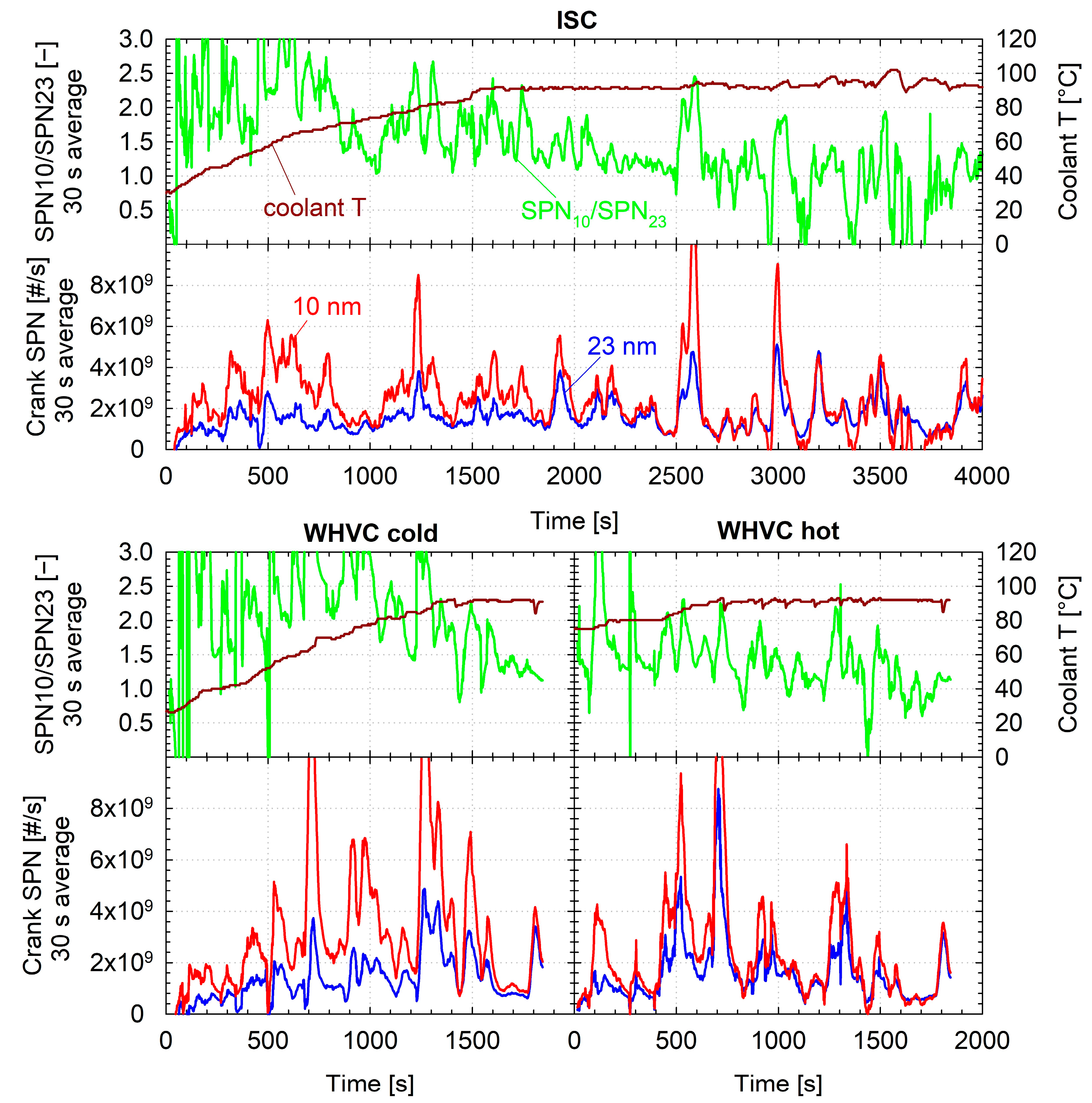

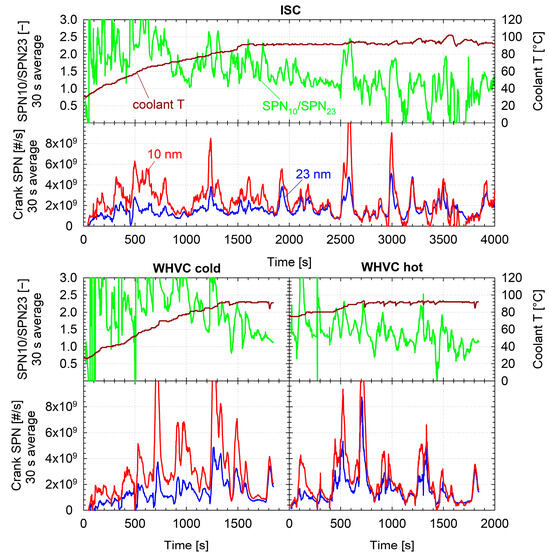

4.2. Increased Emissions of Nanosized Particles During Cold Start Operation

A consistent observation across all cold start tests was an increase in the sub-23 nm fraction of the measured crankcase SPN emissions (as evident from the comparison of SPN10 and SPN23 bars). To provide further insights, Figure 7 compares the real time SPN10 and SPN23 emissions, alongside their ratio, over the ISC, WHVC cold and WHVC hot cycles. The SPN10 to SPN23 ratio gradually decreases as the coolant temperature rises during both the ISC and the WHVC cold cycles. Once the coolant temperature reaches 90 °C, the SPN10 to SPN23 ratio fluctuates to similar levels observed over the WVHC hot cycle (approximately 1.5). Occasional drops below 1 are not physically meaningful, as SPN23 is a subset of SPN10. These fluctuations are due to complexities in calculating the ratio of differences from two signals measured in parallel, and the focus should be on overall trends rather than instantaneous values.

Figure 7.

Comparison of crankcase SPN10 and SPN23 emissions and their ratio across the ISC, WHVC cold and HHVC hot cycles. A 30 s averaging was applied on SPN data to improve the visualization of differences. Tests shown were performed at ambient temperature of 23 °C and crankcase vent line wall temperature of 110 °C. Coolant temperatures reported by the ECU are also plotted for reference. Crank = Crankcase; ISC = In-Service Conformity; WHVC = World Harmonized Vehicle Cycle.

The SPN10 to SPN23 ratio is a reliable indicator of the mean size of emitted particles, with higher ratios corresponding to smaller mean particle sizes. Diesel exhaust soot aerosol typically has a mean particle size of ~60–70 nm, which corresponds to an SPN10 to SPN23 ratio of ~1.1 [25]. In the present study, the observed crankcase SPN10 to SPN23 ratios decreased from approximately 2.5 to 1.5, indicating a shift in the mean particle diameter from ~20 nm to ~35–40 nm [26]. These particle sizes suggest the presence of a distinct nucleation mode, with its relative contribution being higher during cold start engine operation.

The nature of crankcase ventilation aerosol has been the subject of several fundamental research studies [12,17,22]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of particles collected from the crankcase has revealed a soot core coated with varying thicknesses of lubricating oil [17]. These oil-coated particles can reach sizes up to 300 nm, with number concentrations as high as 7 × 107 #/cm3, although the size distribution is highly dependent on engine operating conditions [12,17,22]. This type of aerosol contains a significant amount of lubricating oil (as high as 3 g/m3) which can pose challenges even for state-of-the-art SPN instrumentation [27]. This was the primary reason for opting for an indirect characterization of crankcase emissions in the present study. The crankcase aerosol was diluted approximately 100 times through its mixing with the ~2 orders of magnitude higher exhaust flow (Figure 4). The large crankcase SPN10 to SPN23 ratios observed in this work reflect the efficient removal of lubricating oil by the SPN instrument.

The reduced mean particle size observed during cold start conditions could plausibly be indicative of increased oil combustion within the engine cylinder, potentially resulting from suboptimal tribological conditions in the piston-ring-bore assembly. An increased combustion of lubricating oil could lead to a higher production of ash nanoparticles, thereby contributing to an elevated presence of blow-by nano-particles. These observations warrant further research and investigation to assess whether elevated fractions of nanosized particles are consistently expected during cold-start operation. Nonetheless, further research involving direct characterization of the aerosol at the crankcase ventilation [17] is needed to gain a better understanding of the origin of these nanoparticles.

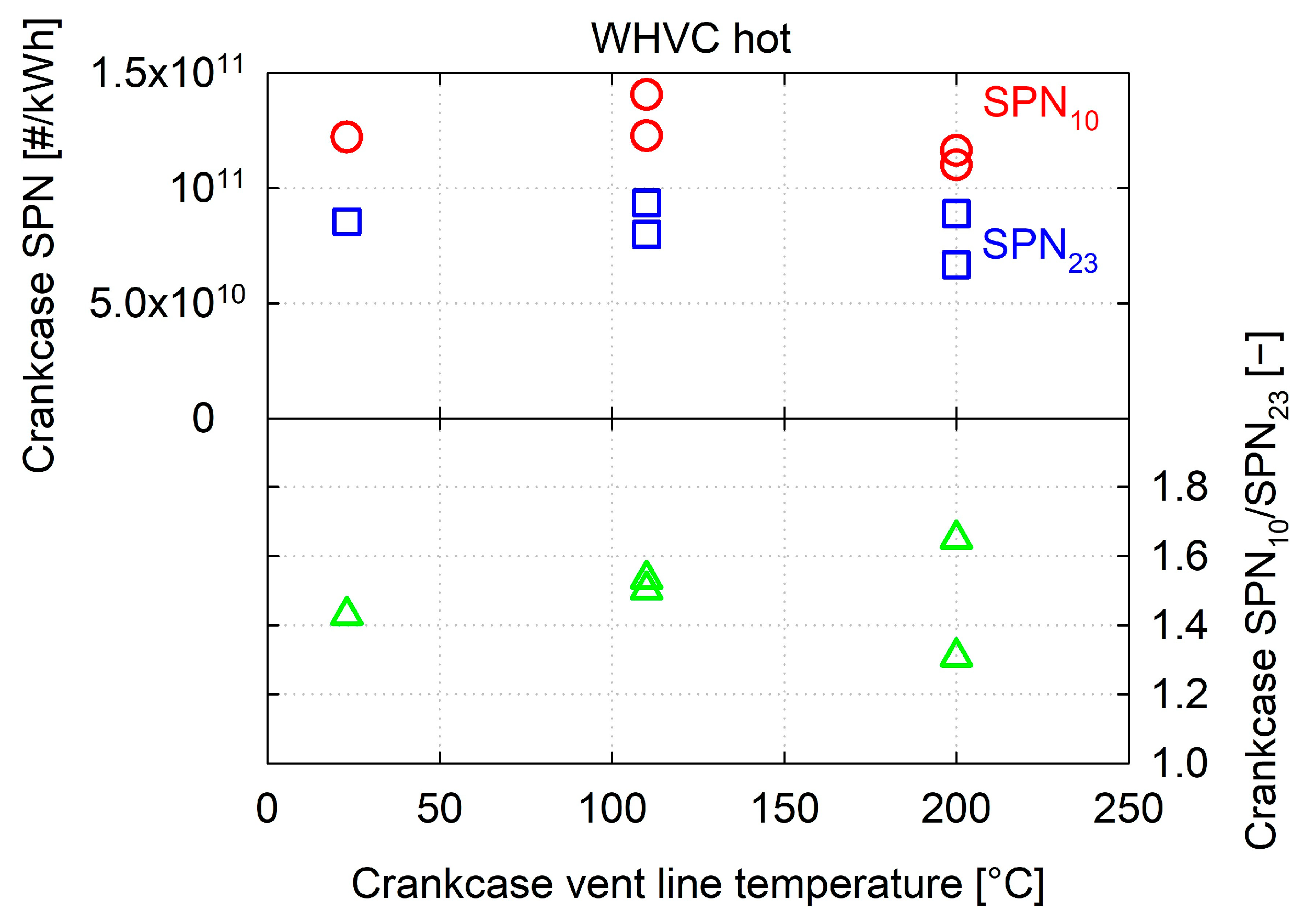

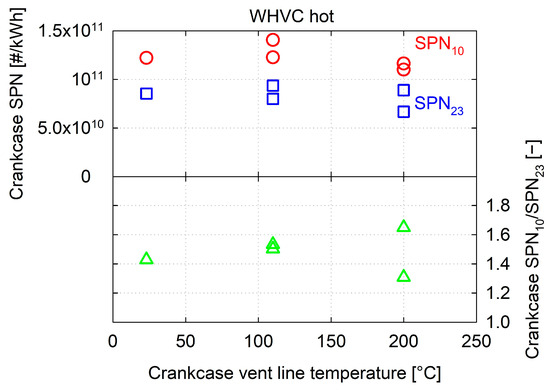

4.3. Effect of Crankcase Vent Line Temperature

Dedicated investigations into the effect of the crankcase vent line wall temperature were performed during this campaign over the WHVC hot cycle. Figure 8 compares the brake specific SPN10 and SPN23 emissions, as well as their ratio, across the three temperatures investigated: ambient, 110 °C and 200 °C. No statistically significant effect was observed in the results. Since the temperature at the crankcase ventilation ranged between 60 and 90 °C, thermophoretic losses associated with using an unheated crankcase vent line are expected to be negligible (4–7%) [28,29]. A potentially relevant loss mechanism related to the crankcase vent line temperature could be inertial losses of large oil particles. However, the experimental results suggest that either no substantial shrinkage of oil particles occurs at a wall temperature of 200 °C and a volume of 2.5 L, or that the inertial losses under the tested conditions are minimal.

Figure 8.

Effect of crankcase vent line temperature on the crankcase SPN emissions (top panel) and ratio of SPN10 to SPN23 emissions (bottom panel) during WHVC hot cycles conducted at a test cell temperature of 23 °C.

A recent study observed unrealistically high SPN concentrations when the crankcase ventilation was routed to the tailpipe, but only in the tests of one of the three in total diesel engines measured [15]. For this specific engine, an unheated silicon tube was used to connect the crankcase to the tailpipe, whereas for the other engines a metallic bellows line heated at 95 °C was employed. The elevated emissions were only observed in the CVS tunnel using an SPN instrument without a CS. A second SPN unit incorporating a CS and sampling directly at the tailpipe downstream of the connection of the crankcase, measured concentrations that were approximately half as high.

The elevated emissions reported in the aforementioned study [15] are likely associated with particle artifact formation in the silicon crankcase vent line. Silicon tubes have been documented to release nanosized particles when exposed to heat, with measurements in dilution tunnels being more susceptible to such artifacts, potentially due to the particles growing in size [30].

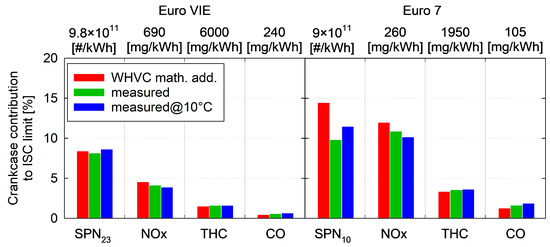

5. Conclusions

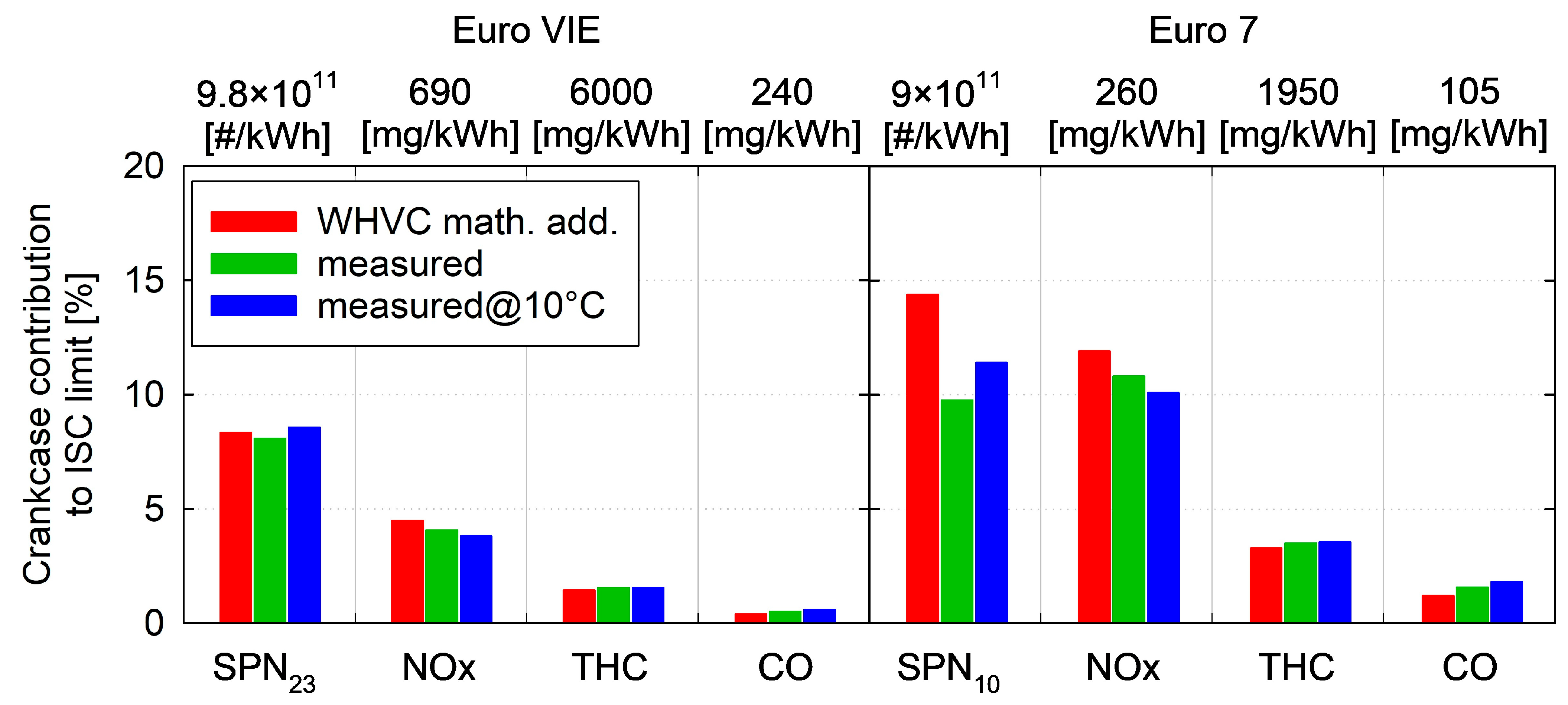

The emissions from the open crankcase of a Euro VI Step E-compliant truck having a total accumulated mileage of 207,500 km were experimentally characterized in this study. Even with the inclusion of crankcase emissions, the truck remained compliant with the upcoming Euro 7 regulations under the tested conditions. Figure 9 provides a summary of the measured crankcase emissions, expressed as a fraction of the applicable Euro VI Step E and Euro 7 emission limits during ISC testing. This effectively allows for a comparison of the two approaches allowed in the UN Regulation Number 49, namely direct measurement or mathematical addition of emissions tested over the type approval cycle (WHTC). For the tested vehicle, the emissions were very similar over WHVC and ISC, suggesting that two approaches would yield equivalent results. Statistical analysis suggested, however, that direct quantification of crankcase emissions by rerouting the crankcase to the tailpipe during ISC testing is more precise, offering the additional advantage of accounting for potential deterioration due to the wearing of piston rings.

Figure 9.

Average crankcase emissions expressed as a fraction of the applicable ISC limits under the Euro VI Step E (left panel) and Euro 7 (right panel) regulations. The use of the WHVC results equivalent to a mathematical addition approach. The Euro VI SPN10 ISC limits were adjusted to also account for the Conformity factor of 1.63 and 1.5 for the gaseous pollutants. SPN = Solid Particle Number.

With respect to the absolute levels, crankcase emissions were found to be relevant for SPN and NOx, accounting for up to 8% of the SPN23 budget and 4% of the NOx budget under current limits, 9.8 × 1011 #/kWh and 690 mg/kWh, respectively. With the further tightening of the limits under Euro 7, crankcase emissions are expected to become even more critical, consuming up to 10–11% of the NOx budget (260 mg/kWh) and 10–14% of the SPN10 (9 × 1011 #/kWh) would have been this still regulated.

No impact of the vent line wall temperature on the crankcase emissions was observed for the setup used. The ratio of 10 nm to 23 nm particles decreased as the engine warmed up, indicating the presence of nucleation mode particles. At cold start the mean particle size was estimated at 20 nm and with warm engine this increased to 40 nm. These nanoparticles are most likely attributed to incomplete oil combustion, which is expected to be more pronounced during engine warm-up.

Our results indicate that crankcase SPN and NOx are not negligible and should be considered during ISC testing. However, it is important to recognize the limitations of our dataset. The tested vehicle is a widely used platform in Europe. At the time of testing, its mileage was approximately 207,500 km—about 180,000 km more than the minimum required for ISC testing. Nevertheless, this single vehicle may not fully represent the emissions footprint of the broader European heavy-duty fleet equipped with OCV systems. In addition, this study does not reflect worst-case scenarios, such as elevated oil consumption and increased blow-by from piston ring wear, nor does it account for hardware differences in OCV system designs, such as variations in oil separators and the possibility of their degradation over time. This is particularly relevant given the regulatory useful life of 700,000 km for these vehicles. Therefore, further research is needed to comprehensively characterize crankcase emissions across different platforms and operating conditions. This study primarily provides insights into the relative merits of two regulatory approaches and establishes a methodology for the precise characterization of crankcase ventilation emissions, which could help refine regulatory frameworks to better address these emissions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. (Athanasios Mamakos), R.S.-B. and B.G.; methodology, A.M. (Athanasios Mamakos) and A.M. (Anastasios Melas); formal analysis, A.M. (Athanasios Mamakos); writing—original draft preparation, A.M. (Athanasios Mamakos); writing—review and editing, D.R., R.G., R.S.-B. and B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the JRC VELA technical staff (M. Cadario, D. Zanardini, P. Macri) and AVL’s resident engineer, A. Bonamin, for their support in the experimental activities.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Athanasios Mamakos and Dominik Rose were employed by Corning GmbH. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and should not in any way be considered to represent an official opinion of the European Commission. The mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by the authors or the European Commission.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APC | Advanced Particle Counter |

| CPC | Condensation Particle Counter |

| CS | Catalytic Stripper |

| DPF | Diesel Particulate Filter |

| ECU | Electronic Control Unit |

| EFM | Exhaust Flow Meter |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| HD | Heavy Duty |

| HEPA | High Efficiency Particulate Air |

| ISC | In-Service Conformity |

| MAW | Moving Average Window |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| OCV | Open Crankcase Ventilation |

| PCRF | Particle Concentration Reduction Factor |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| SCR | Selective Catalytic Reaction |

| SPN | Solid Particle Number |

| SPN10 | Solid Particle Number above 10 nm |

| SPN23 | Solid Particle Number above 23 nm |

| WHTC | World Harmonized Transient Cycle |

| WHVC | World Harmonized Vehicle Cycle |

| Wref | Reference Engine Work over the WHTC cycle |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of tailpipe (and crankcase in parenthesis) emissions in accordance with the Euro VI Step E methodology (see Figure 5).

Table A1.

Summary of tailpipe (and crankcase in parenthesis) emissions in accordance with the Euro VI Step E methodology (see Figure 5).

| Emissions | WHVC 23 °C | WHVC 10 °C | ISC 23 °C | ISC 10 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPN23 cold ×1011 [#/kWh] | 2.8 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.2 (0.9) |

| SPN23 hot ×1011 [#/kWh] | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.8) |

| SPN23 weighted ×1011 [#/kWh] | 1.9 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.8) |

| SPN10 cold ×1011 [#/kWh] | 4.2 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.5 (2.0) | 4.3 (2.0) |

| SPN10 hot ×1011 [#/kWh] | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.2) | 5.0 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.9) |

| SPN10 weighted ×1011 [#/kWh] | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.2) | 4.9 (0.9) | 4.1 (1.1) |

| NOx cold [mg/kWh] | 528 (42) | 492 (34) | 480 (40) | 176 (34) |

| NOx hot [mg/kWh] | 83 (29) | 83 (29) | 93 (26) | 86 (25) |

| NOx weighted [mg/kWh] | 145 (31) | 140 (30) | 147 (28) | 99 (26) |

| HC cold [mg/kWh] | 6 (4) | 8 (1) | 8 (3) | 7 (3) |

| HC hot [mg/kWh] | 6 (5) | 8 (1) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) |

| HC weighted [mg/kWh] | 6 (5) | 8 (1) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) |

| CO cold [mg/kWh] | 555 (46) | 379 (39) | 478 (38) | 390 (38) |

| CO hot [mg/kWh] | 355 (20) | 355 (21) | 274 (38) | 164 (35) |

| CO weighted [mg/kWh] | 383 (24) | 358 (23) | 303 (31) | 196 (35) |

Figure A1.

Comparison of SPN23 traces from APC1 and APC2, as well as gas emission traces of AMA1 and AMA2 over a hot WHVC cycle, with instruments sampling at the same position (APCs upstream and AMAs downstream of the crankcase rerouting to the tailpipe). Percentage numbers correspond to the cycle-average differences.

Figure A1.

Comparison of SPN23 traces from APC1 and APC2, as well as gas emission traces of AMA1 and AMA2 over a hot WHVC cycle, with instruments sampling at the same position (APCs upstream and AMAs downstream of the crankcase rerouting to the tailpipe). Percentage numbers correspond to the cycle-average differences.

Figure A2.

An example application of the MAW methodology for the ISC test conducted at an ambient temperature of 10 °C. The shaded areas below the coolant temperature curve represent the cold and hot sections of the test cycle, as defined by the regulated procedure. The cyan dashed line indicates the seconds excluded from the analysis due to the minimum coolant temperature requirement of 30 °C. The black curve represents the duration, in seconds, of each MAW window used in the calculations, with the duration of the final window corresponding to the remaining section of the coolant temperature curve (dark red section) over which the work equals the reference work.

Figure A2.

An example application of the MAW methodology for the ISC test conducted at an ambient temperature of 10 °C. The shaded areas below the coolant temperature curve represent the cold and hot sections of the test cycle, as defined by the regulated procedure. The cyan dashed line indicates the seconds excluded from the analysis due to the minimum coolant temperature requirement of 30 °C. The black curve represents the duration, in seconds, of each MAW window used in the calculations, with the duration of the final window corresponding to the remaining section of the coolant temperature curve (dark red section) over which the work equals the reference work.

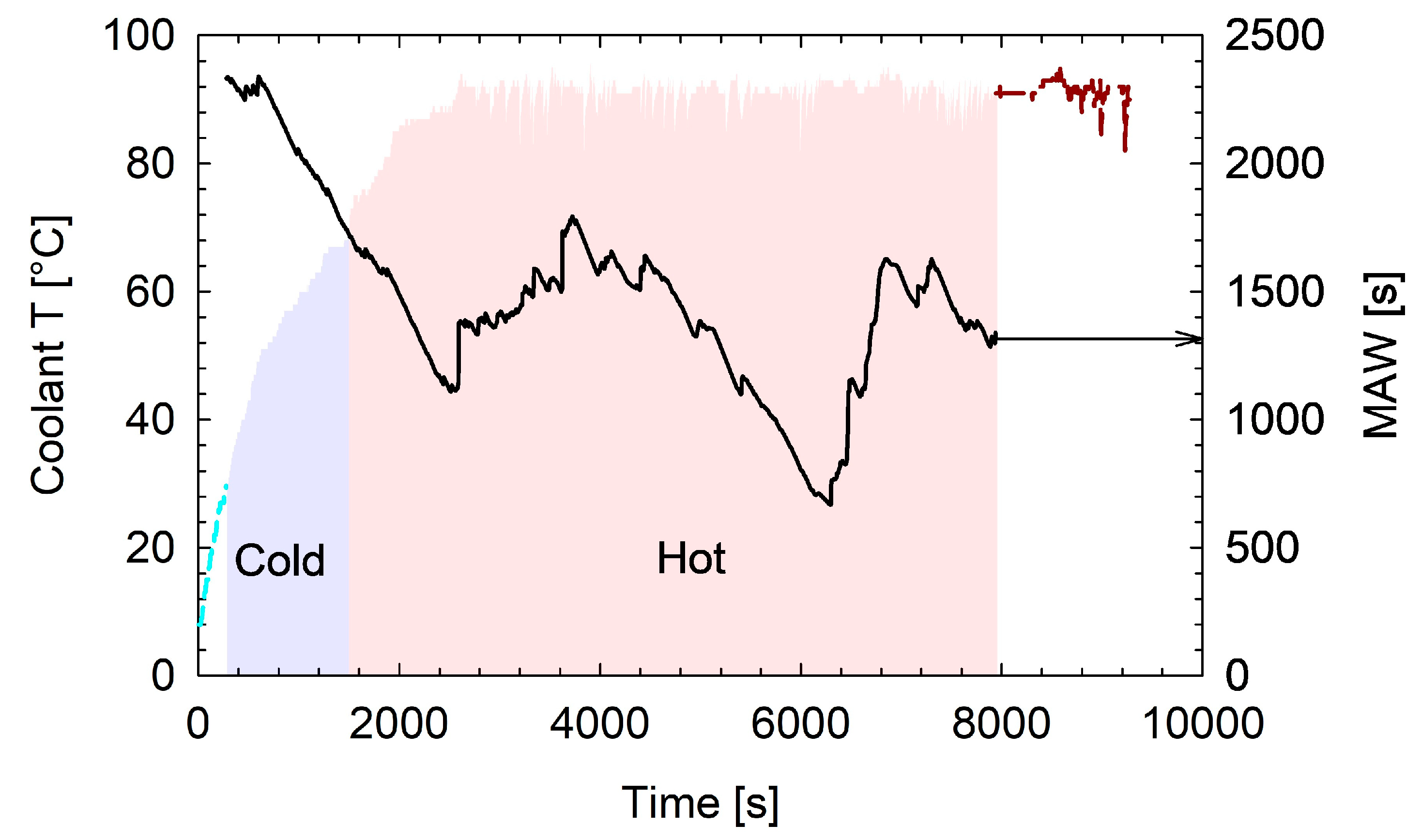

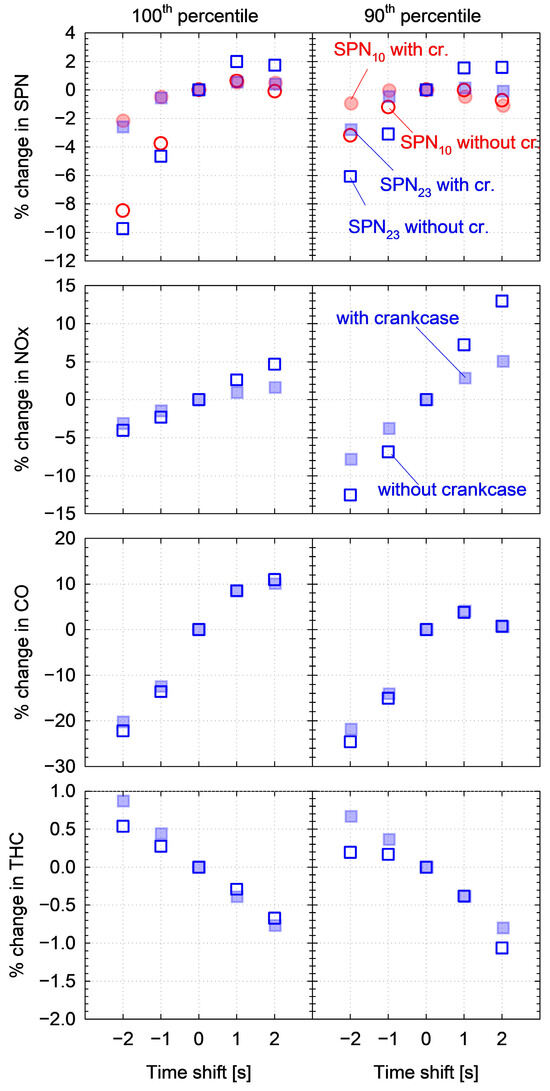

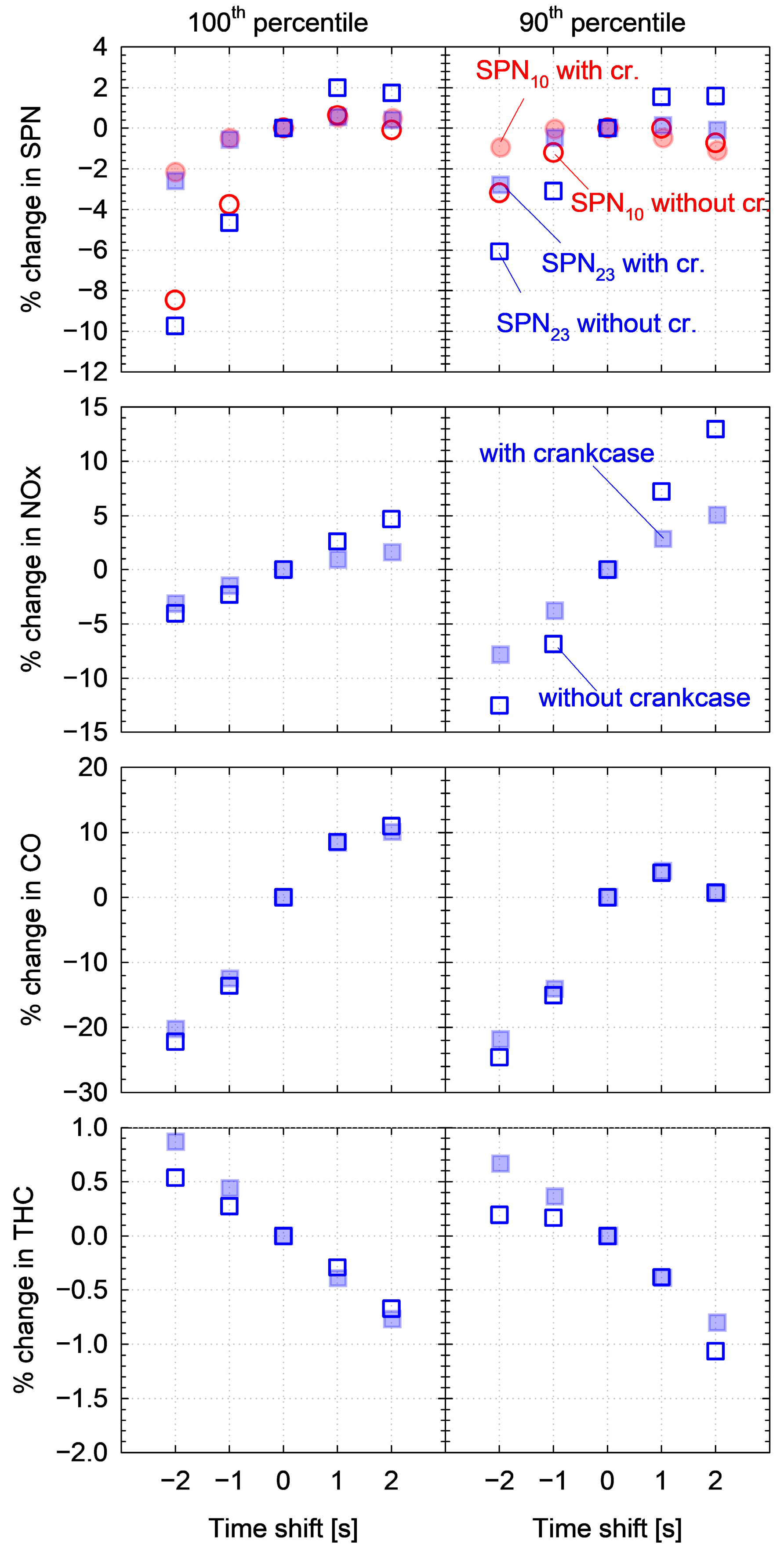

Figure A3.

Average effect of ±2 s misalignment between exhaust flow and analyzer records on the 90th- and 100th-percentile ISC test results.

Figure A3.

Average effect of ±2 s misalignment between exhaust flow and analyzer records on the 90th- and 100th-percentile ISC test results.

References

- European Environment Agency. The European Environment–State and Outlook 2020–Knowledge for Transition to a Sustainable Europe; Publications Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Air Quality Status Report 2025; EEA Report (Online); Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Christou, A.; Giechaskiel, B.; Olofsson, U.; Grigoratos, T. Review of Health Effects of Automotive Brake and Tyre Wear Particles. Toxics 2025, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, L.B.; Force, C.A.T.; Zimmerman, N.J.; Gooch, J. A Multi-City Investigation of the Effectiveness of Retrofit Emissions Controls in Reducing Exposures to Particulate Matter in School Buses; Clean Air Task Force: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jaroszczyk, T.; Holm, C.E.; Fallon, S.L.; Schwandt, B.W.; Gradoń, L.; Steffen, B.P.; Zuroski, M.T.; Koleshwar, A.K.; Moy, J.J. New Developments in Diesel Engine Crankcase Emission Reduction-Equipment, Design and Performance. J. KONES Powertrain Transp. 2006, 13, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Avergård, P.; Lindström, F. Modelling of Crankcase Gas Behaviour in a Heavy-Duty Diesel Engine. Master’s Thesis, Lund Institute of Technology, Lund, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dollmeyer, T.A.; Vittorio, D.A.; Grana, T.A.; Katzenmeyer, J.R.; Charlton, S.J.; Clerc, J.; Morphet, R.G.; Schwandt, B.W. Meeting the US 2007 Heavy-Duty Diesel Emission Standards-Designing for the Customer. In Proceedings of the SAE Technical Paper Series; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, C.T.; Baines, T.M. Characterization of Diesel Crankcase Emissions. In Proceedings of the SAE Technical Paper Series; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Environmental Technology Verification Report. Mobile Source Emission Control Devices. Donaldson Company, Inc. Series 6000 Diesel Oxidation Catalyst Muffler and Spiracle Clossed Crankcase Filtration System; Research Triangle Institute: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, N.; Tatli, E.; Barnett, R.; Wayne, W.S.; McKain, D.L. Characterization and Abatement of Diesel Crankcase Emissions. In Proceedings of the SAE Technical Paper Series; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Environmental Technology Verification Report. Mobile Source Emission Control Devices. 201350N DOC Plus Coalescer Breather CV5061200 and Crankcase Depression Regulator (CDR) Valve 395587500; Research Triangle Institute: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tatli, E.; Clark, N. Crankcase Particulate Emissions from Diesel Engines. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2008, 1, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Environmental Technology Verification Report. New Condensator, Inc. The Condensator Diesel Egnine Retrofit Crankcase Ventilation System; Greenhouse Gas Technology Center, Southern Research Institute: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Schwelberger, M.; Kronlund, L.; Delacroix, C.; Locke, L.A.; Khan, M.Y.; Jakobsson, T.; Otsuki, Y.; Gandi, S.; Keller, S.; et al. Towards Tailpipe Sub-23 Nm Solid Particle Number Measurements for Heavy-Duty Vehicles Regulations. Transp. Eng. 2022, 9, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Lv, T.; Lai, Y.; Mu, J.; Ge, Y.; Giechaskiel, B. Particulate Emissions of Heavy Duty Diesel Engines Measured from the Tailpipe and the Dilution Tunnel. J. Aerosol Sci. 2021, 156, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) No 582/2011 of 25 May 2011 Implementing and Amending Regulation (EC) No 595/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Respect to Emissions from Heavy Duty Vehicles (Euro VI) and Amending Annexes I and III to Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Text with EEA Relevance. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, L 167, 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Uy, D.; Storey, J.; Sluder, C.S.; Barone, T.; Lewis, S.; Jagner, M. Effects of Oil Formulation, Oil Separator, and Engine Speed and Load on the Particle Size, Chemistry, and Morphology of Diesel Crankcase Aerosols. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2016, 9, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 595/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2009 on Type-Approval of Motor Vehicles and Engines with Respect to Emissions from Heavy Duty Vehicles (Euro VI) and on Access to Vehicle Repair and Maintenance Information and Amending Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 and Directive 2007/46/EC and Repealing Directives 80/1269/EEC, 2005/55/EC and 2005/78/EC (Text with EEA Relevance); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Selleri, T.; Gioria, R.; Melas, A.D.; Giechaskiel, B.; Forloni, F.; Mendoza Villafuerte, P.; Demuynck, J.; Bosteels, D.; Wilkes, T.; Simons, O.; et al. Measuring Emissions from a Demonstrator Heavy-Duty Diesel Vehicle under Real-World Conditions—Moving Forward to Euro VII. Catalysts 2022, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/1939 of 7 November 2019 Amending Regulation (EU) No 582/2011 as Regards Auxiliary Emission Strategies (AES), Access to Vehicle OBD Information and Vehicle Repair and Maintenance Information, Measurement of Emissions during Cold Engine Start Periods and Use of Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS) to Measure Particle Numbers, with Respect to Heavy Duty Vehicles (Text with EEA Relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L 303, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1257 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on Type-Approval of Motor Vehicles and Engines and of Systems, Components and Separate Technical Units Intended for Such Vehicles, with Respect to Their Emissions and Battery Durability (Euro 7), Amending Regulation (EU) 2018/858 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 715/2007 and (EC) No 595/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Regulation (EU) No 582/2011, Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1151, Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2400 and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/1362. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, L, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Fang, L.; Lou, D. Particle Filter Performance of Soot-Loaded Diesel Particulate Filter and the Effect of its Regeneration on the Particle Number and Size Distribution. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surenahalli, H.S.; Backhaus, J.; Liu, Q.; Dabhoiwala, R.; Martin, T. Experimental Study of Impact of Ash and Soot on Tail Pipe Particle Number. In Proceedings of the SAE Technical Paper Series; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, P.; Baron, P.A.; Willeke, K. (Eds.) Aerosol Measurement: Principles, Techniques, and Applications, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-38741-2. [Google Scholar]

- Samaras, Z.; Rieker, M.; Papaioannou, E.; Van Dorp, W.F.; Kousoulidou, M.; Ntziachristos, L.; Andersson, J.; Bergmann, A.; Hausberger, S.; Keskinen, J.; et al. Perspectives for Regulating 10 Nm Particle Number Emissions Based on Novel Measurement Methodologies. J. Aerosol Sci. 2022, 162, 105957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamakos, A.; Rose, D.; Besch, M.C.; He, S.; Gioria, R.; Melas, A.; Suarez-Bertoa, R.; Giechaskiel, B. Evaluation of Advanced Diesel Particulate Filter Concepts for Post Euro VI Heavy-Duty Diesel Applications. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission—Joint Research Centre: Institute for Energy and Transport. Feasibility Study on the Extension of the Real Driving Emissions (RDE) Procedure to Particle Number (PN): Chassis Dynamometer Evaluation of Portable Emission Measurement Systems (PEMS) to Measure Particle Number (PN) Concentration: Phase II; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Housiadas, C.; Drossinos, Y. Thermophoretic Deposition in Tube Flow. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Arndt, M.; Schindler, W.; Bergmann, A.; Silvis, W.; Drossinos, Y. Sampling of Non-Volatile Vehicle Exhaust Particles: A Simplified Guide. SAE Int. J. Engines 2012, 5, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Mamakos, A.; Woodburn, J.; Szczotka, A.; Bielaczyc, P. Evaluation of a 10 Nm Particle Number Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS). Sensors 2019, 19, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).