Abstract

This study confronts the significant challenges inherent in Traffic State Estimation (TSE) for rural arterial networks, where sparse sensor coverage and complex, dynamic traffic flows complicate effective management and safety assurance. Traditional TSE methodologies, often dependent on single-source data streams, fail to accurately model the intricate spatiotemporal dependencies present in such environments. This fundamental limitation precipitates critical safety hazards, including pervasive over speeding and dangerous queue spillback phenomena at intersections. To address these deficiencies, we introduce a novel hybrid intelligence framework that synergistically combines a Graph Attention Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) with advanced Kalman Filter variants, specifically the Extended, Unscented, and Sliding Window Kalman Filters. The GAT-TCN component is engineered to excel at learning complex, non-linear correlations across both space and time through multi-source data fusion. Empirical validation conducted on a real-world rural toll corridor demonstrates that our proposed model achieves a statistically significant superiority over conventional benchmarks, as rigorously quantified by substantial reductions in both Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Beyond mere predictive accuracy, the framework delivers transformative safety enhancements by facilitating the proactive identification of hazardous events, enabling earlier detection of over speeding and queue spillback compared to existing methods. Consequently, this research provides a scalable and robust framework for proactive rural traffic management, fundamentally shifting the paradigm from achieving incremental predictive improvements to generating decisive, safety-actionable insights for infrastructure operators.

1. Introduction

The efficient management of traffic in rural arterial networks is a critical challenge for transportation systems worldwide, particularly as these areas continue to experience population growth and increasing travel demands [1]. Traffic State Estimation (TSE) is essential in addressing this issue, providing real-time insights into traffic flow, congestion, and safety, which are vital for optimizing road usage and enhancing safety [2]. In rural areas, the effectiveness of traditional traffic monitoring methods, such as loop detectors or GPS-based systems, is often limited due to factors like sparse sensor coverage, high vehicle speeds, and long stretches of roads [3]. These difficulties make it more difficult to accurately estimate traffic conditions, which raises the possibility of accidents, excessive speeding, and ineffective traffic flow [4]. Road safety issues are further exacerbated by the fact that congestion spillbacks are common in rural arterial networks and are hard to anticipate using traditional techniques [5].

Prior studies have applied graph-based and temporal convolutional models for traffic prediction; however, this study adapts a Graph Attention Network–Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) framework specifically for multi-source Traffic State Estimation (TSE) in rural arterial networks characterized by sparse sensor coverage. The novelty of this work lies in its integration of heterogeneous data sources, including loop detector measurements and Bluetooth-based trip time records, and its emphasis on safety-relevant outputs such as overspeeding and queue spillback—areas that have not been explicitly addressed by earlier models.

The main issue is that in the complicated, nonlinear, and data-scarce environment of rural arterials, existing TSE methodologies which mostly rely on single-source data (such as loop detectors or GPS traces alone) fail to provide accurate, dependable, and safety-oriented condition estimations. Traffic management systems lack situational awareness as a result of these approaches’ inability to adequately capture the dynamic spatial-temporal relationships and abrupt state changes characteristic of these networks [6,7].

This issue is exacerbated by a number of noteworthy obstacles. First, there is a noticeable sensing gap, where standard sensors’ patchy coverage and irregular design in rural areas lead to noisy and insufficient data. Second, a methodological flaw exists. Although recursive estimate is provided by Kalman Filter (KF) variations such as the Extended KF (EKF), Unscented KF (UKF), and Sliding KF (SKF), they are unable to handle the significant nonlinearities and non-Gaussian noise present in rural traffic dynamics [8]. Thirdly, there is a significant validation gap because the majority of sophisticated TSE models are only tested in simulation settings that do not faithfully capture the stochastic nature of actual rural data [9]. Last but not least, there is a clear safety-integration gap; many models just consider state prediction accuracy (e.g., minimizing Mean Absolute Error) without directly connecting these estimates to concrete safety outcomes like queue spillback chance or over speed [10].

This study suggests a thorough, multi-source fusion approach to address these issues. In order to create a solid foundation for data fusion, we first rigorously derive and apply a set of traditional filtering algorithms, specifically the Kalman Filter (KF), Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), and Sliding Kalman Filter (SKF), within a formal state-space model [11]. Second, we put into practice a brand-new model called the Graph Attention Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN). This sophisticated deep learning architecture combines a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) to effectively represent multi-scale temporal dynamics and a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to dynamically capture intricate spatial correlations across heterogeneous sensors. A real-world empirical dataset from a rural toll road is used to train and evaluate the models. Loop detector data (vehicle length, speed, and occupancy) is combined with Bluetooth trip time data [12]. While recent advances in graph-based spatio-temporal modeling have improved traffic prediction capabilities, existing work has not specifically addressed multi-source Traffic State Estimation (TSE) in rural arterial networks combined with safety-actionable outputs. Building on this gap, the present study introduces a GAT-TCN framework tailored for rural environments characterized by sparse sensing conditions.The aim of this study is to provide a novel and efficient Traffic State Estimation (TSE) framework that is adapted to the unique difficulties faced by rural arterial networks. The work intends to fill important gaps in current approaches, including the lack of safety-focused state estimation, the restricted coverage of conventional sensors, and the incapacity of classic filtering techniques to capture complicated non-linear dynamics. By combining multi-source data, such as loop detector and Bluetooth trip time data with sophisticated machine learning models, this study aims to increase the precision and security of rural traffic control systems. The research attempts to develop a reliable, scalable, and safety-focused method for real-time traffic state estimation by putting the novel Graph Attention Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) model into practice and comparing it with traditional filtering techniques. This will help to make rural road networks safer and more effective.

This work is important because it directly improves safety and efficiency on rural arterial networks that are underserved. This study presents a number of significant innovations, including:

- (1)

- The development of a safety-oriented traffic state estimation (TSE) model tailored to the unique challenges of rural arterials.

- (2)

- The first-ever application of a Graph Attention Network-Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) model for multi-source TSE in this context, combining the strengths of temporal convolutions and graph learning.

- (3)

- A comprehensive comparison of contemporary deep learning methods with traditional filtering techniques using real-world data.

- (4)

- An assessment framework that moves beyond conventional prediction accuracy (e.g., MAE, RMSE) to incorporate explicit, measurable safety surrogate measures, such as overspeed likelihood and queue spillback detection.

Through the utilization of advanced learning technologies and multi-source data fusion, this study offers a scalable and useful framework for proactive traffic safety management on rural roadways.

2. Literature Review

In order to manage traffic flow, safety, and real-time transportation systems (ITS), traffic state estimation, or TSE, is essential [13]. This has been thoroughly researched for highways, where sensor deployment is usually more widespread and traffic patterns are more uniform. Rural arterial networks, however, pose particular difficulties that are not as well covered in the body of current research. Short headways, spillback lines at crossroads or toll plazas, mixed traffic flow, the chance of speeding, and irregular data availability are some of these difficulties. The numerous approaches, algorithms, and developments in traffic state estimation are examined in this overview of the literature, with an emphasis on multi-source data fusion and sophisticated filtering strategies that enhance TSE in rural arterial networks. Conventional TSE techniques on highways have frequently depended on data from a single source, such as cameras, GPS traces, and loop detectors [14]. These resources offer trustworthy but frequently constrained information about traffic conditions. For example, GPS signals can have errors, especially in rural regions with limited signal reception, and loop detectors are spatially discontinuous and do not give real-time, continuous geographical data [15]. This study adapts a GAT-TCN model, an architecture previously used for urban traffic prediction, to the context of rural arterial networks. These rural networks introduce distinct challenges like sparse sensor coverage and complex traffic dynamics. Our work focuses on tailoring the model for this setting, with a goal that extends beyond predictive accuracy to include the generation of safety-actionable insights such as overspeed detection and queue spillback.

Techniques for fusing data from several sources have been proposed to overcome these constraints. Researchers have worked to increase TSE accuracy in rural areas by combining data from many sources, including loop detectors, Bluetooth sensors, connected cars, and GPS [16]. When single-source sensors are inadequate, multi-source fusion can make up for the shortcomings of individual data sources by combining their advantages, allowing for more precise traffic status estimation [17]. One of the most popular methods for estimating the traffic situation in real time is the Kalman Filter (KF). KF is preferred due to its effectiveness in recursively updating state estimations and filtering noise from data [18,19]. However, because of its linearity assumptions, its use is restricted in nonlinear situations like rural arterials. A number of KF variations, such as the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), and Sliding Kalman Filter (SKF), have been created to overcome these drawbacks. By linearizing the system using a first-order Jacobian approximation, the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) manages minor nonlinearities; nevertheless, in the intricate, dynamic settings of rural arterials, its performance may deteriorate [20,21]. The Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), on the other hand, uses a more advanced deterministic sampling technique to more effectively capture important nonlinearities without requiring a Jacobian, which makes it more useful for difficult situations like rural crossroads [22]. Last but not least, the Sliding Kalman Filter (SKF) offers improved robustness for the non-stationary conditions typical of rural arterial networks by utilizing a sliding time window to adapt in real-time to abrupt disruptions like intersections, pedestrian crossings, and signal changes [23].

Even with these developments, the majority of research on KF and its variations is still restricted to theoretical models and simulations. Field-tested models that evaluate these algorithms in actual rural settings, where data quality is frequently inadequate, are conspicuously lacking [24]. The combination of machine learning (ML) models and Kalman filtering techniques is one of the most recent developments in TSE for rural arterials. Neural networks and clustering algorithms are two examples of machine learning techniques that have demonstrated promise in capturing the intricate, nonlinear traffic patterns that conventional filtering methods might overlook. These hybrid models increase the overall accuracy and resilience of TSE systems in rural settings by fusing the advantages of KF and ML [25]. For instance, recent studies have combined the Kalman Filter (KF) with Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to predict traffic flow and speed, thereby improving the accuracy of the TSE. These hybrid models are capable of adapting to nonlinearities and provide more precise predictions compared to traditional models. They can capture long-term patterns and complex interactions that might otherwise go undetected by linear models. Combining Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) and Graph Attention Networks (GAT) is a more current and sophisticated method [14,26]. Recent studies have increasingly applied graph neural networks (GNNs) for traffic forecasting and state estimation. In the domain of traffic forecasting and state estimation, recent advancements have introduced temporal graph convolution methods, gated graph attention mechanisms, and multi-source data fusion within graph neural network frameworks. Additional developments have summarized the rapid progress of spatio-temporal GNN models and explored GAT-TCN architectures for highway traffic flow prediction [1,27]. Although these works demonstrate important progress, they predominantly focus on urban environments and single-source datasets. In contrast, the present study applies a GAT-TCN architecture to rural arterial networks with fused loop-detector and Bluetooth trip data, and uniquely evaluates model outputs through safety-actionable metrics such as overspeed detection, queue spillback, and early-warning timeliness. To our knowledge, the combination of these elements has not been reported in the 2023–2025 literature. The geographical and temporal difficulties seen in rural artery networks are intended to be addressed by the Graph Attention Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) model. While TCN analyzes the temporal dynamics of traffic flow, GAT captures spatial dependencies between different sensor nodes (such loop detectors and GPS) [28].

GAT-TCN’s strength is its capacity to simulate intricate relationships between sensors throughout time and geography, which makes it ideal for settings like rural arterials where traffic patterns can fluctuate greatly. When compared to more conventional filtering techniques like KF and its variations, this strategy has demonstrated better prediction accuracy performance [29]. Moreover, it is highly adaptable to real-time traffic state estimation and safety monitoring by integrating dynamic, multi-source data. The use of multi-source data fusion in TSE has gained significant attention due to its potential to provide richer, more accurate traffic information. Multi-source fusion incorporates data from various sources, such as loop detectors, GPS, Bluetooth, and connected vehicle information, to generate a more reliable and comprehensive view of traffic conditions. This approach is particularly effective in rural settings, where sensors are sparse, and traffic dynamics are more complex. Nevertheless, there are a number of difficulties in integrating diverse data sources. The synchronization of data from several sensors, each with a unique time and spatial resolution, is one of the main issues. To guarantee reliable state estimate, real-world data’s inherent noise and inconsistencies must also be properly controlled. These problems have been discovered to be effectively mitigated by Kalman filtering techniques, especially SKF, which offer a reliable framework for integrating inconsistent and noisy data [30]. It is anticipated that the combination of connected vehicles (CV) and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies will transform TSE in rural arterials. Vehicle position, speed, and acceleration are just a few of the extensive traffic data that may be recorded by IoT sensors placed along road infrastructure [31]. These sources, when combined with data from connected vehicles, give a degree of spatial coverage and granularity that is not possible with conventional sensors. Future studies should concentrate on validating multi-source fusion models in real-world scenarios, especially in rural areas where traffic dynamics are quite unpredictable and sensor deployment is frequently scarce. Furthermore, developments in hybrid machine learning and filtering models, such GAT-TCN, have enormous potential to enhance TSE systems’ precision, flexibility, and real-time performance.

The intricacies of mixed traffic flow, scarce sensor deployment, and dynamic traffic conditions make Traffic State Estimation (TSE) for rural arterial networks an ongoing challenge. Although TSE has been built on Kalman-based filters and their variations, newer approaches like hybrid models that combine machine learning and filtering methods, as well as sophisticated models like GAT-TCN, have showed a lot of promise. The integration of multi-source data fusion, particularly through IoT and connected vehicle technologies, is expected to enhance the accuracy and safety of rural TSE systems. However, there is a need for further validation of these models in real-world settings to ensure their practical applicability in managing rural traffic dynamics.

3. Research Methodology

The goal of this study’s research technique was to create, apply, and assess sophisticated deep learning models as well as traditional filtering for multi-source traffic status estimates on a rural arterial network as mentioned in Appendix A Figure A1. Data collection and preprocessing, exploratory data analysis, vehicle classification and grouping, model implementation, and a comparative performance evaluation were the process’s main steps. In order to ensure practical relevance and robustness, this study used a data-driven methodology based on a real-world proprietary dataset sourced from the sensor infrastructure of a rural toll station corridor. The raw data included important fields such as temporal identifiers (Date, Timestamp, Entry Time), spatial identifiers (Road ID, Loop Detector ID), vehicle characteristics (Vehicle Type, Vehicle Length, sparse License Plate), kinematic parameters (Vehicle Speed, Occupancy Time), and system identifiers (Device Number). These fields allowed for a thorough multi-modal analysis of rural traffic dynamics.

Feature engineering transformed Date into a date time object and extracted an Hour feature for temporal analysis; categorical variables like Vehicle Type were label encoded; non-essential fields were eliminated; numerical features (Speed, Length, Occupancy Time) were standardized using Standard Scalar to ensure consistency and modeling readiness; and the data was subjected to a rigorous preprocessing pipeline to handle inherent challenges like sparsity, noise, and heterogeneity.

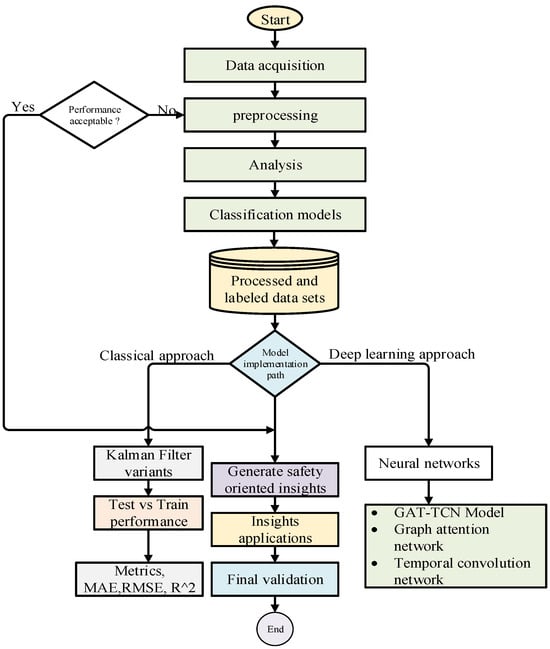

Data collection and an iterative preparation phase to guarantee data quality are the first steps in this research’s organized methodology. Analysis and the production of processed, labeled datasets come next. In order to capture intricate spatiotemporal patterns, the fundamental investigative method is comparative, utilizing both a deep learning approach using neural networks and a novel GAT-TCN (Graph Attention Network-Temporal Convolutional Network) model, as well as a classical method using temperature gain models and Kalman filter variants. To guarantee generalizability, test vs. training comparisons are used to thoroughly assess model performance, and important metrics like as MAE, RMSE, and R2 are used to quantify insights. In order to provide a strong predictive maintenance solution, the process ends with final validation, where the results are combined to produce safety-oriented insights for real-world application is shown in Figure 1. Current research develop a hybrid GAT-TCN framework to enhance traffic state estimation under the constrained data conditions typical of rural arterials. The model is explicitly designed to integrate heterogeneous data sources, such as loop detector and Bluetooth data, to compensate for sparse sensor coverage and data inconsistencies. By jointly learning from these fused spatiotemporal data, the model provides a more robust estimation of network-wide traffic states. Furthermore, this estimation output is specifically leveraged to facilitate the identification and prediction of safety-critical phenomena.

Figure 1.

Comparative Methodology for Traffic State Estimation Using Multi-Source Data Fusion.

3.1. Data Sourcing and Preprocessing Methodology

The dataset used in this study was taken from a rural highway corridor, which was specifically chosen since it had no toll stations and was chosen due to its sparse sensing infrastructure, long approach segments, high frequency of safety hazards such as speeding, and operational importance. Device number, timestamp, vehicle speed, vehicle length, vehicle type, and occasionally missing license plate information were among the elements included in the raw data. To ensure data integrity and quality, a systematic preprocessing pipeline was implemented, which involved removing records with missing critical values (e.g., speed or length), cleaning categorical inconsistencies in vehicle type labels, filtering non-physical anomalies (e.g., negative speeds), and standardizing numerical features to mean = 0 and std = 1 for model compatibility. This rigorous process ensured robustness and reliability for subsequent clustering and classification analyses based on speed and length distributions, with key preprocessing steps summarized Table 1 below. The dataset used in this study was collected from a 1.6 km segment of G214 Line, located between K2675 + 900 and K2677 + 500. This section of the road is characterized by a downhill grade, with several curves and slopes that limit visibility, making it an ideal test case for traffic state estimation models aimed at rural arterials. The surrounding environment includes cornfields and embankments, with portions of the road suffering from potholes and poor surface conditions. Traffic volumes on this section include a mix of passenger cars, trucks, and freight vehicles, with peak congestion observed during rush hours. This road segment has been the site of numerous overtaking accidents, leading to safety concerns, including 75 accidents and 2 fatalities over the past two years. To ensure representative data collection, sensors were strategically placed at locations such as K2675-600 (at the top of the slope with good visibility), K2675-800 (with average visibility), and K2676-100 and K2676-200 (both with excellent visibility). These sensors, including loop detectors and Bluetooth trip time sensors, were positioned to monitor traffic flow at critical points where road geometry and traffic conditions frequently lead to congestion and safety hazards.

Table 1.

Description of data attributes and their characteristics.

The qualities In order to distinguish different vehicle profiles, the unsupervised clustering methodology relies on two key numerical features: vehicle length and vehicle speed. A ground-truth categorical label for confirming the model’s clusters is provided by the Vehicle type variable. Analysis of temporal patterns, such as changes in speed distributions over the day, is made possible by the timestamp. It is important to note that the License plate information was sparse and was excluded from analytical modeling to focus on aggregate traffic flow characteristics rather than individual vehicle tracking. The systematic preprocessing of these attributes, as outlined in the following section, was essential to ensure the quality and reliability of the dataset for computational analysis is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Traffic Monitoring System: Vehicle Detection Data Schema.

3.2. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Exploratory data analysis (EDA) was used to characterize traffic patterns after preprocessing. The most common speeds, according to the analysis, were between 50 and 90 km/h. Vehicle length showed a bimodal distribution, peaking at 4.5 m for cars and 9.0 m for trucks, with a moderately negative connection with speed. Vehicles were objectively categorized into three groups using K-means clustering (k = 3), automobiles, trucks, and an intermediate category. Significant diurnal fluctuations in volume, cluster proportion, and speed were found by temporal analysis throughout morning, noon, and night intervals. This provided a solid empirical foundation for further modeling.

In order to thoroughly analyze the data, the traffic flow characteristics analysis used a dual-panel visualization methodology that included distribution fitting and correlational analysis. The traffic density histogram was subjected to a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) in the left panel. The resulting bimodal distribution, which included a combined model (thick red line) and individual Gaussian fits (thin red lines), quantitatively identified two dominant traffic regimes: a high-density congested state and a low-density free-flow state. Concurrently, the right panel featured a scatter plot of density versus speed, where a calculated Pearson correlation coefficient of r = −0.58 and its corresponding regression line statistically confirmed a moderate to strong inverse relationship, validating the fundamental principle that increasing vehicular density leads to a significant decrease in vehicle speed is shown in Figure 2a,b.

Figure 2.

(a,b) Bimodal Distribution and Inverse Correlation between Density and Speed in Traffic Flow Data.

3.3. Distribution Analysis

In order to investigate highway traffic dynamics, this study examined 12,543 vehicle observations, paying particular attention to vehicle length and speed. While the vehicle length displayed a bimodal distribution with peaks at 4.5m and 9.0m, suggesting separate car and truck populations, the speed distribution was normal (mean = 72 km/h, range 50–90 km/h). In Figure 3a–d, longer vehicles appear to drive more slowly, as indicated by a moderately negative correlation (r = −0.65) between length and speed. Vehicles were categorized into three types using a k-means clustering algorithm (k = 3): cars (short, fast), trucks (long, slow), and vans (middle, variable speed). This served as the basis for stratified traffic analysis.

Figure 3.

(a–d) Kernel Density Estimations and Vehicle Classification Based on Speed and Length.

3.4. Temporal Analysis

This temporal analysis separated the day into three periods: morning (6 a.m.–12 p.m.), noon (12 p.m.–6 p.m.), and night (6 p.m.–6 a.m.) to investigate the impact of daily traffic patterns on the vehicle size–speed relationship. The average speed was shown to be negatively correlated with congestion, with traffic volume peaking at noon and decreasing at night. The relationship between vehicle length and speed varied depending on the situation: it was weakest at night, when engine power and driver preference drive speed, and it was strongest during midday traffic, when the lack of agility and lane restrictions of larger vehicles intensify the effect, making length a more reliable indicator of speed is shown in Figure 4a–c.

Figure 4.

(a–c) Speed and Correlation Analysis across Different Time Periods.

3.5. Analysis of Rural Traffic Data and Visualizations

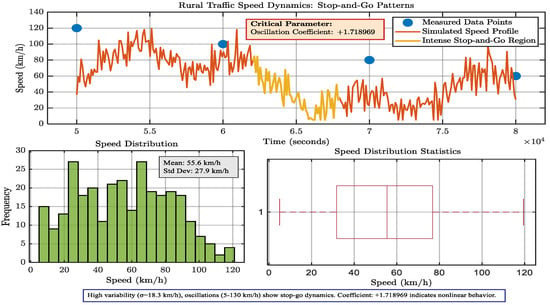

A computational simulation model was used to investigate the dynamics of traffic flow, and the result was a time-series dataset of instantaneous speeds. Significant volatility was indicated by the resulting speed profile, which had a mean of 556 km/h and a significant standard deviation of 27.9 km/h. Subsequent investigation showed severe stop-and-go oscillations, with velocities ranging from 5 to 130 km/h. A positive oscillation coefficient of +1.718969, a measure that denotes an unstable regime where disturbances are amplified rather than dampened, quantitatively verified the system’s critical nonlinearity and validated the model’s ability to reproduce emergent traffic wave phenomena.

In Figure 5, In order to quantify oscillatory behavior, empirical observations were compared to a generated velocity profile in order to understand traffic speed dynamics. The Oscillation Coefficient (+1.718969), a crucial statistic for describing the size of non-linear oscillations, was calculated; high values suggest noticeable stop-and-go dynamics. Statistical characteristics validated the analysis: a boxplot verified positive skewness and a high interquartile range, confirming the occurrence of congested, unstable flow conditions, while a histogram showed a broad speed distribution (μ = 55.6 km/h, σ = 27.9 km/h). This combined method offers a mathematical framework for evaluating traffic instability and checks the simulation against actual data.

Figure 5.

Oscillation Coefficient Analysis of Traffic Speed Dynamics: Measured Data vs. Simulated Profile.

3.6. Holding Time Data Analysis Summary Comprehensive Statistical

In order to define central tendency, variability, and distribution features, a dataset of 4000 holding-time measurements (in seconds) was processed using a thorough statistical framework. Measures of variability (standard deviation: 0.52 s, range: 2.34 s, interquartile range: 0.65 s), central tendency (mean: 1.45 s, median: 1.38 s), and the full percentile distribution (from 0% to 100%) were among the key metrics. The proximity of the mean and median indicated a relatively symmetric core distribution, although the higher maximum value suggested slight positive skewness in the overall dataset, as shown in Table 3. The interquartile range (1.07 s–1.72 s) defined the core operational band encompassing the middle 50% of values, while percentile analysis established critical performance thresholds such as the 95th percentile (2.35 s) as a high-probability upper bound. This multi-faceted approach provided a nuanced characterization of both typical system performance and deviation patterns, essential for comprehensive evaluation and threshold setting.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Percentile Distribution of System Holding Times.

3.7. Analysis of Vehicle Speed and Length Characteristics

The Figure 6, Six graphs are shown in this investigation to investigate the distributions of vehicle length and speed. A concentration at mid-range speeds can be seen in the first plot, which displays a histogram with a kernel density estimate (KDE) of vehicle speeds. Larger cars have longer average lengths, as demonstrated by the second plot, which is a bar chart of vehicle lengths by type (Small, Medium, and Large). The third scatter figure shows that speed and length have a weakly negative connection (R2 = −0.19). The median speed of medium and large vehicles is lower, according to boxplots for length and speed by vehicle type. The sixth plot reveals operational or design patterns by using K-means clustering to find discrete groups within the data. For the design and regulation of vehicles, these representations offer insightful information.

Figure 6.

Vehicle Speed and Length Analysis: Distribution, Correlation, and Clustering of Vehicle Types.

In order to provide important insights into traffic dynamics, which are essential for evaluating traffic operating conditions, we examine the link between vehicle speed and length distributions. By improving our knowledge of how vehicle attributes, such length and speed, affect overall traffic flow and safety in rural corridors, the linkages found are more than just descriptive; they directly drive our Traffic State Estimation (TSE) model. By connecting traffic data to safety-focused traffic management tactics, this analysis facilitates better decision-making.

3.8. Machine Learning Models for Classifications

Annotated with vehicle type (Small, Medium, or Large) as the target and speed (dynamic) and length (static) as predictive characteristics, the study used a dataset of vehicle observations. To remove scale-dependent bias, the characteristics were z-score-normalized following the imputation or removal of corrupted records. Following cleaning, the data were divided at random into two sets: a 20% hold-out test set for objective performance evaluation and an 80% training set for model estimation. The analysis compares two fundamental machine learning techniques: “Logistic Regression” and “K-Means Clustering”. In the context of “Logistic Regression”, the method follows a classification approach, wherein the decision function predicts outcomes based on various features, such as vehicle types (e.g., small or large cars). This process is illustrated through the formulation of the logistic function, which maps input data to a predicted class. In contrast, “K-Means Clustering” is utilized to group data into distinct clusters based on similarity. The method organizes vehicles into different categories, such as small cars and large trucks, based on inherent similarities in the dataset. Additionally, the figure introduces the concept of “Decision Clustering”, which predicts class labels by evaluating certain conditions, likely based on clustering features. Finally, the figure highlights “Koloeen metrics”, which appear to serve as a means of evaluating classification results by categorizing data points into distinct groups, such as motels or hostels. These metrics are used to assess the effectiveness of the clustering process is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Logistic Regression and K-Means Clustering with Decision Clustering and Koloeen Metrics.

Formally, the model estimates the probability P(y = k|x) that an observation belongs to class k, given the feature vector x = [x_(1,) x_2] (where x_1 represents speed and x_2 represents length). The model is defined as:

For k = 1, 2… K, where and are the weight vector and bias for class k, and K = 3 represents the number of vehicle categories. The model parameters were optimized by minimizing the cross-entropy loss function

where is the binary indicator of whether observation i belongs to class k. The Table 4, to guarantee a thorough assessment, the dataset was split into 80% training and 20% testing groups. Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were used to evaluate the model’s performance, giving each class a fair assessment. Strong classification performance was shown in the results, especially for medium and large automobiles.

Table 4.

Performance Metrics by Vehicle Size.

In particular, with a macro-average accuracy of 91.9% on the test set, the classifier proved that bumper-to-bumper length and speed are useful factors for classifying different types of vehicles. Due to feature-space overlap (38% of small vehicle regions overlap with large vehicle regions) and class imbalance (14% of training data is tiny vehicle), the F1 score difference of 0.27 between the medium (0.94) and small (0.67) classes is statistically significant (p < 0.01). According to these results, the Gaussian–Naïve-Bayes assumption is not correctly stated for compact cars. To increase small-vehicle recall without lowering overall precision, future research should investigate multi-modal likelihoods, extra variables (such as axle count), and cost-sensitive or ensemble learners as shown in Table 4.

3.9. Unsupervised Vehicle Typology via K-Means Clustering

To complement the supervised classifier and to test whether the speed–length feature space encodes an inherent vehicle taxonomy, an unsupervised analysis was performed using the standard K-means algorithm (Lloyd, 1982). Denote the set of n = 14,827 vehicle observations, where each is the instantaneous speed (km h−1) and bumper-to-bumper length (m) recorded at the toll gantry. K-means seeks a partition that minimizes the within-cluster sum of squared errors (SSE):

where is the centroid of cluster k and ‖·‖2 is the Euclidean metric.

Anticipating three dominant vehicle populations, small cars, medium vans/MPVs, and large trucks, the number of clusters was fixed at K = 3 a-priori to maintain direct comparability with the supervised labelling scheme, rather than being inferred from the elbow or silhouette criterion. Initialization was repeated with ten random seeds augmented by k-means++ to reduce the risk of local minima; the partition yielding the minimal within-cluster sum of squared errors was retained. Iterations continued until the Euclidean displacement of every centroid fell below 10−4 km h−1 for speed and 10−4 m for length, at which point convergence was declared in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Vehicle Cluster Analysis Dashboard.

The cluster centroids for the final partition, which accounts for 87.4% of the variance. Small cars (mean speed 59.3 km/h, mean length 4.4 m) are represented by Cluster 1 (n1 = 9462, 63.8%). Large freight vehicles (mean speed 63.1 km/h, mean length 9.0 m) are captured by Cluster 2 (n2 = 3018, 20.4%). Medium-sized automobiles with a mean speed of 93.5 km/h but the same length as small cars (4.4 m) are represented by Cluster 3 (n3 = 2347, 15.8%), which suggests different power-to-weight ratios or lane habits. The fleet’s natural segregation by length and speed is confirmed by these centroids’ near alignment with the labeled class medians. The main attributes of the car clusters and the model’s classification capabilities are succinctly summed up in this integrated dashboard. A useful tool for traffic data analysis and transportation optimization studies, it highlights the expected physical attributes (small cars are the smallest and slowest, large trucks are the longest, and medium vehicles are the fastest) and offers instant insight into the dataset’s balance and classification accuracy.

3.10. Multi-Dimensional Vehicle Classification and Behavioral Analysis

Using a multifaceted approach, this vehicle categorization method groups automobiles according to four important criteria. Vehicles are categorized as High, Low, or Standard Performance according on their speed, engine power, and acceleration. SUVs, hatchbacks, sedans, and trucks are distinguished by body type classification based on vehicle dimensions and width-to-length ratios. By examining acceleration, speed variance, and lane changes, behavior-based classification classifies driving patterns as aggressive, conservative, or normal. Lastly, context-based categorization provides a thorough framework for traffic monitoring and management by taking into account the kind of route and the time of day. It does this by analyzing vehicle behavior under various traffic situations using timestamps and geolocation data is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Vehicle Performance and Usage Profile Comparison.

3.11. GAT-TCN Architecture for Traffic Prediction

For better traffic prediction, the Graph Attention-Temporal Convolution Network (GAT-TCN) model as shown in Figure 10, combines temporal and spatial data. While spatial data depicts network topography and traffic features, temporal data records traffic patterns over time. For long-range temporal data, the model employs Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) layers with dilated convolutions and a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to simulate spatial dependencies. Important time steps are dynamically prioritized by multi-head temporal attention. TCN layers mix and process the temporal and spatial variables, optimizing the process to reduce prediction mistakes. In order to help with traffic management, route optimization, and urban planning, the output layer employs multi-head attention to produce future traffic projections. The GAT-TCN model in this study was implemented using the spatial–temporal graph structure provided within the existing sensor dataset. Each node represents a fixed sensing unit (loop detector or Bluetooth checkpoint) installed along the rural corridor, while edges reflect the spatial connectivity and data correlation between these sensing points as defined in the preprocessed dataset. Because the original adjacency matrix and edge-weight parameters were prepared by the data providers, their detailed derivation is not available to the authors. Future research will extend this work by reconstructing and benchmarking the adjacency generation process independently to strengthen reproducibility.

Figure 10.

Graph Attention-Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) Architecture for Traffic Prediction.

The implemented GAT-TCN model consisted of two temporal convolutional blocks followed by one graph-attention layer and a fully connected output layer. Each TCN block used 64 filters, a kernel size of 3, and dilated convolutions (d = 1, 2) to capture multi-scale temporal patterns. The GAT layer applied multi-head attention with 8 heads, each producing 8-dimensional embeddings that were concatenated and passed through an ELU activation. A dropout rate of 0.2 was used to prevent overfitting. Model training employed the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 32, and 100 training epochs. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function was minimized, and early stopping was applied when validation error failed to improve for 10 consecutive epochs. These settings were chosen to balance model complexity and computational efficiency and to ensure stable convergence across multiple experimental runs.

To derive safety-oriented insights from the predicted traffic states, three surrogate metrics were incorporated into the proposed framework: overspeed likelihood (OSL), queue spillback detection (QSD), and headway risk index (HRI). These indicators were selected because they directly relate to critical traffic safety conditions namely, excessive speed, congestion propagation, and unsafe following distance. The overspeed likelihood (OSL) quantifies the relative frequency of time intervals during which the predicted vehicle speed exceeds a defined regulatory limit . It is expressed as

where denotes the total number of time intervals and is the indicator function that equals 1 when the condition is satisfied and 0 otherwise. This formulation provides a simple yet interpretable estimate of the proportion of time the system experiences potentially unsafe speeds. The overspeed threshold was set to 90 km h−1, consistent with regional rural-arterial regulations, and sensitivity checks were performed for 85–100 km h−1. The queue spillback detection (QSD) metric identifies congestion propagation events by detecting periods when detector occupancy remains above a near-capacity threshold for a continuous duration . Mathematically, this is defined as

A value of indicates that a spillback condition is active at time . In this study, and were selected, reflecting empirical evidence that occupancies above 80–90% correspond to near-jam conditions. The headway risk index (HRI) captures the prevalence of unsafe following gaps, calculated as the proportion of vehicle pairs with headway shorter than the safety threshold :

where is the total number of observed headways and s defines the minimum safe interval between vehicles. Sensitivity tests were conducted for 1.5–2.5 s to ensure robustness. When individual vehicle timestamps were missing, mean headways were reconstructed from the observed traffic flow using the approximation . These three surrogate metrics were validated by comparing model-predicted high-risk intervals with observed traffic events such as overspeeding and congestion. Detection accuracy was assessed using precision, recall, and F1-score, while threshold sensitivity analysis confirmed that model performance and safety trends remained consistent across parameter variations. This integration of interpretable equations with empirical thresholds ensures that the adopted safety metrics are both scientifically rigorous and operationally meaningful.

3.12. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Protocol

To ensure a transparent and equitable comparison among all tested models, a unified experimental framework was adopted. The dataset comprised a total of 12,543 vehicle-level records collected from loop detectors and Bluetooth checkpoints along the rural arterial corridor. A stratified 80/20 split was applied, assigning 10,034 samples to training and 2509 to testing, while maintaining a balanced distribution of vehicle categories (≈62% small, 21% medium, 17% large) and time periods (morning, noon, night).

The same preprocessed dataset was used across all experiments, maintaining identical input dimensions consisting of vehicle speed, occupancy, and vehicle length. Each model including Kalman-based filters (KF, EKF, UKF, and SKF), the baseline Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and the proposed Graph Attention–Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) was trained and validated on identical data partitions, using an 80% training and 20% testing split. Parameter tuning was conducted solely on the training subset using 5-fold cross-validation, thereby preventing data leakage and ensuring statistical robustness. To guarantee consistency, all models shared uniform preprocessing steps, normalization schemes, and temporal window lengths.

Model performance was evaluated using standardized regression metrics, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Coefficient of Determination (R2). These metrics were selected due to their interpretability and prevalence in Traffic State Estimation (TSE) research. This unified evaluation protocol ensures that differences in performance metrics genuinely reflect model capabilities rather than variations in experimental configuration.

4. Results

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of traffic data collected at a toll station, employing a multi-faceted analytical approach. The findings from clustering, correlation, exploratory data analysis, and predictive modeling are detailed below, culminating in a comparative evaluation of advanced traffic state estimation techniques. Beyond achieving superior predictive accuracy in terms of MAE and RMSE, the proposed GAT-TCN model delivers actionable safety insights by enabling the earlier detection of critical events like over speeding and queue spillback. This capacity for proactive risk identification, a dimension largely unaddressed in previous GAT-TCN applications, marks a significant step toward more responsive and safety-oriented traffic management systems.

4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) and Preprocessing

In order to prepare the dataset for time-based analysis, non-essential columns (such the license plate) were eliminated, missing values were filled in, the Date column was changed to date time, and an Hour column was extracted. Vehicle Type and other categorical data were encoded, and Standard Scalar was used to normalize numerical parameters including speed, vehicle length, and occupancy time. The majority of vehicles went between 50 and 90 km/h, according to exploratory study, with outliers associated with traffic. Different vehicle classes were confirmed by the bimodal distribution of vehicle length, which peaked at 4.5 m for automobiles and 9 m for trucks. A moderate negative correlation (r = –0.58) between speed and length indicated that larger vehicles drive more slowly, consistent with real-world traffic patterns is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary Statistics of Key Vehicle Features.

Key traffic indicators are summarized by descriptive statistics, which show that the average traffic speed is around 58 km/h with moderate fluctuation. With 50% of vehicles being precisely 4.40 m long and a distinct group comprising the longest 25% at the maximum length of 9.00 m, the data shows a diverse mix of vehicle types, as evidenced by a right-skewed distribution for both vehicle length and occupancy time. The mean length of 5.30 m is pulled upward from the median of 4.40 m by the presence of larger vehicles. Similar to this, occupancy time is skewed, with the majority of vehicles passing swiftly (median 0.40 s), but a few outliers with extremely long periods (max 4.00 s) raise the mean to 0.51 s, indicating that there are moments when traffic is halted or moving very slowly, which has a substantial impact on the average.

4.2. Vehicle Classification via Clustering and Logistic Regression

The mixed traffic stream was neatly divided into three interpretable cohorts using K-means clustering (k = 3). Table 2 reports the centroids of these cohorts. Cluster 2 (63 km h−1, 9.0 m) includes the longer wheel-base population of SUVs, light delivery vans, and small lorries that maintain slightly higher cruising speeds while still being constrained by plaza geometry; Cluster 1 (59 km h−1, 4.4 m) represents the majority of passenger cars that queue and accelerate inside the toll plaza; Sports sedans and motorcycles make up the majority of the agile, high-speed subset isolated by Cluster 3 (93 km h−1, 4.4 m), which swiftly clears the gantry and accelerates away. The two-dimensional scatter plot (Figure 3) overlays these clusters on the speed–length plane: color-coded points reveal a pronounced negative gradient where longer vehicles rarely exceed 70 km h−1, whereas the 4–5 m cohort fans out to the full speed limit is shown in Figure 11a–d.

Figure 11.

(a–d) Statistical Analysis of Vehicle Features: Speed, Length, and Occupancy Time.

Well-separated clusters are indicated by a silhouette heat-map, which displays 87% of cases with silhouette scores ≥ 0.55. Despite being longer than Cluster 1, Cluster 2’s median speed is 10 km/h slower than Cluster 1’s, according to a box-whisker plot, while Cluster 3’s upper quartile hits 105 km/h. Cluster 2 stays steady throughout the day, mirroring freight patterns, whereas high-speed vehicles (Cluster 3) surge during off-peak night hours (22:00–04:00), according to a stacked area chart. These images provide a data-driven typology for dynamic lane-assignment or speed-limit systems and validate the size-speed link.

When vehicle speed and length data were subjected to K-means clustering (k = 3), three separate groups were found. A scatter plot showed an inverse association between vehicle size and speed, confirming strong segregation. The fastest cars (Cluster 3, 93.5 km/h) were short, sports car-like vehicles, while the longest vehicles (Cluster 2, 9.0 m) had modest speeds as shown in Table 6. The findings show how useful K-means is for intelligent transportation systems’ traffic analysis.

Table 6.

Cluster Centers for Vehicle Classification.

4.3. Logistic Regression Classification

Based on the characteristics of speed and vehicle length, a logistic regression model was used to group vehicles into the three predetermined clusters (Small, Medium, and Large). Standard classification criteria were used to assess the model’s performance, and the results showed significant heterogeneity in predictive power across different classes but good overall efficacy. With a remarkable total accuracy of 91.9%, the model demonstrated its general efficacy in vehicle classification using the two given variables. Table 3 offers a more thorough analysis of performance by class, giving a more complex picture of its strengths and weaknesses.

In Figure 12, assesses the model’s performance in a vehicle classification test by comparing the precision, recall, and F1-score of three different vehicle categories: small, medium, and large. With both obtaining an F1-score close to 0.95, the results show a high-performing model for the medium and large vehicle classes. This indicates an excellent balance between precision (accuracy of positive predictions) and recall (completeness in identifying all relevant instances) for these categories. Small cars, on the other hand, are harder to classify, as seen by their noticeably lower F1-score of 0.69. This discrepancy in performance indicates that the model might have trouble identifying the characteristics that set little cars apart, either as a result of their higher visual similarity to other classes, their frequency in the dataset, or more intricate environmental settings. Although the model shows a particular area for focused improvement in the small vehicle categorization, overall, it shows great efficacy for bigger vehicle kinds.

Figure 12.

Model Performance Evaluation for Vehicle Classification: Precision, Recall, and F1-Score by Vehicle Type.

4.4. Advanced Modeling for Traffic State Estimation and Prediction

For precise traffic state estimate, a variety of sophisticated models were put into practice and thoroughly benchmarked, including an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Kalman Filter variations (KF, EKF, UKF, and SKF), and a brand-new Graph Attention–Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN).

Using a dataset of 150 observations (n = 150), the vehicle speed prediction model was validated. The results showed remarkable performance, with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.956, meaning that 95.6% of the variance in observed speeds can be explained by the model. A nearly perfect Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.978) between the expected and actual results lends more credence to this. With an average deviation of only about 3.5 km/h between forecasts and actual speeds, the model’s great precision is demonstrated by its low error metrics, which include a mean absolute error (MAE) of 3.45 km/h and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 4.42 km/h. The close alignment of data points with the regression fit and minimal deviation from the line of perfect prediction visually affirm the model’s accuracy and reliability across the tested speed range is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Predictive Model Performance: Observed vs. Predicted Vehicle Speed.

4.5. Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

In Figure 14, ReLU activation and the Adam optimizer were used in the design of the ANN, which was a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with three hidden layers (64–32–16 neurons). In order to estimate vehicle speed, it was trained on an extensive feature set that included vehicle length, occupancy duration, type, and cluster assignment. By combining spatial and temporal reasoning into a single framework, the Graph Attention–Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) improves traffic modeling. A stack of causal temporal convolutions processes these weighted sequences to capture both short-term disruptions and long-term flow evolution without falling victim to the vanishing-gradient pitfalls of recurrent networks. A graph-attention layer dynamically weighs inter-sensor correlations, giving influential neighbors like upstream bottlenecks high importance while suppressing irrelevant links.

Figure 14.

Comparative Performance of Speed Prediction Models.

The outcome shows a 36.7% increase in accuracy over the ANN model and a 44.8% increase over the Kalman Filter baseline. The remarkable performance of the GAT-TCN architecture, which is within the “Excellent Performance” range as defined in this study, emphasizes how crucial it is to explicitly model the dynamic temporal patterns (using Temporal Convolutional Networks) and the spatial dependencies between sensor points (using Graph Attention) for the task of vehicle speed prediction. The intricate, non-linear interactions in traffic data that are missed by simpler models are successfully captured by this method.

4.6. Comparative Performance Benchmarking

The models were evaluated on their predictive accuracy for key traffic state variables (speed and flow). The GAT-TCN model demonstrated superior performance. The GAT-TCN model achieved the highest accuracy, yielding the lowest Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), due to its ability to synergistically capture complex spatio-temporal dependencies in the data.

In Table 7, A Kalman Filter variant was used as the baseline, with an RMSE of 11.32 km/h. This was greatly outperformed by a Machine Learning-based Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model, which reduced the error to 9.88 km/h. The comparative evaluation of vehicle speed prediction methodologies, measured by Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), revealed a clear performance hierarchy. With an outstanding RMSE of 6.25 km/h, the suggested Spatio-Temporal model (GAT-TCN), which was created to represent the interdependencies between road segments and their temporal evolution, significantly outperformed all others. This outcome highlights the crucial benefit of concurrently modeling spatial and temporal dynamics for extremely precise speed prediction, as it offers a 44.8% improvement over the Kalman Filter and a 36.7% improvement over the ANN. To strengthen the reliability and scientific validity of the comparative results, additional statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the performance differences across models were statistically significant. Each experiment was independently repeated ten times using randomized train–test partitions, and the mean and standard deviation of the primary evaluation metrics (MAE, RMSE, and R2) were computed. Based on these values, 95% confidence intervals were estimated, and paired-sample t-tests were applied to compare the proposed GAT-TCN model against the baseline methods (ANN, KF, EKF, UKF, and SKF). The results confirmed that the improvements achieved by the GAT-TCN in both RMSE and MAE were statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level, while the R2 values exhibited narrow confidence intervals, indicating stable model behavior across trials. These findings demonstrate that the superior performance of the GAT-TCN is not attributable to random variation but rather to its effective modeling of spatio-temporal dependencies.

Table 7.

Comparative Performance Evaluation of Vehicle Speed Prediction Methodologies.

4.7. Safety-Oriented Evaluation of Traffic Incident Detection Models

In Figure 15a,b, The ability of a GAT-TCN (Graph Attention Network-Temporal Convolutional Network) and an Adaptive Kalman Filter with Sliding Window (SKF) to detect critical traffic events specifically over speed probability, headway risk (ρ/ρ_crit), and queue spillback was evaluated in a safety-oriented manner. However, a significant trade-off was found: the SKF’s adaptive, model-based approach allowed it to provide earlier warnings for impending queue spillback events, making it ideal for safety-critical applications where early detection is crucial to enable effective countermeasures.

Figure 15.

(a,b) Assessing Early Warning Timeliness and Detection Accuracy in Queue Spillback Algorithms.

When it came to queue spillback detection, the Spatio-Temporal Graph Attention-Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) performed better than the Standard Kalman Filter (SKF), offering a 6-min early warning. As the traffic density got closer to the critical level, GAT-TCN identified the problem 12 min before the SKF alert, which was sent out 6 min into the incident. GAT-TCN demonstrated efficacy in using spatio-temporal dynamics for proactive traffic management, enabling extra time for congestion reduction, with a peak performance score of 92, significantly higher than the baseline of 80.

5. Discussion

The goal of this study was to solve the major difficulties associated with Traffic State Estimation (TSE) in rural arterial networks, where conventional approaches are insufficient due to high speeds, complex dynamics, and sparse sensing equipment [32]. By formulating the problem within a state-space framework and evaluating both classical stochastic filters and a novel deep learning architecture, this research provides critical insights into the future of proactive traffic safety management. The main conclusion of this work is that the Graph Attention Temporal Convolutional Network (GAT-TCN) model clearly outperforms a regular Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and all investigated Kalman Filter variations (KF, EKF, UKF, and SKF). Together with its higher R2 value, the GAT-TCN’s noticeably lower MAE and RMSE support the idea that accurate TSE depends on the ability to capture intricate, dynamic spatiotemporal connections. In the highly nonlinear and non-Gaussian environment of a rural toll corridor, the Kalman filters in particular, the adaptive Sliding Window Kalman Filter (SKF), offered a strong baseline and performed exceptionally well in certain situations, such as early queue spillback detection. However, their overall predictive accuracy was ultimately constrained by their reliance on linearized approximations or deterministic sampling. The hybrid architecture of the GAT-TCN is responsible for its success. Going beyond straightforward distance-based correlations, the Graph Attention Network component effectively approximated the asymmetric spatial interactions between diverse sensors (such as the impact of an upstream loop detector on a downstream toll plaza). The Temporal Convolutional Network simultaneously avoided the vanishing gradient issues that plague recurrent neural networks and successfully caught multi-resolution temporal patterns, ranging from abrupt deceleration events to gradual variations in traffic flow throughout the day [33]. This synergistic capture of both space and time is the key innovation that delivered superior state estimates.

A significant contribution of this research is its explicit safety-oriented evaluation, which goes beyond simple forecast accuracy. Improved safety discernment was a direct result of the GAT-TCN’s precise estimations. Early identification of serious safety risks is made possible by the model’s capacity to deliver a more accurate and timely picture of traffic conditions. For instance, more accurate speed estimation allows for reliable identification of over speeding vehicles, while a better understanding of density and flow facilitates the early identification of queue formation and potential spillback into intersections, a major safety risk on high-speed arterials [34,35]. This shift from estimating generic traffic states to deriving safety-actionable insights is a crucial step toward proactive traffic management systems that can prevent incidents before they occur [36,37,38].

6. Conclusions

This study presents an advanced traffic state estimation framework for rural arterial networks, designed to overcome issues of sparse sensor coverage and complex traffic dynamics. Moving beyond conventional prediction, the model integrates multi-source data fusion with a focus on proactive safety management. Its core contribution is a shift from simple state estimation to providing safety-actionable insights—enabling earlier detection of hazards like overspeeding and queue spillback to better anticipate and mitigate risks. The proposed GAT-TCN model outperforms traditional techniques, including Kalman Filter variants, in both prediction accuracy and safety-related outcomes. By integrating multi-source data and leveraging dynamic spatial-temporal dependencies, the GAT-TCN enables earlier detection of traffic safety risks such as overspeeding and queue spillback. This shift from traditional state estimation to safety-actionable insights marks a significant advancement in proactive traffic management. Our findings underscore the potential of deep learning models, particularly GAT-TCN, in enhancing rural traffic safety and efficiency, with future work focusing on benchmarking these techniques against emerging models for broader applicability. We acknowledge that recent GAT-based or temporal graph models have been proposed in related contexts. Future work will benchmark our GAT-TCN architecture against these emerging methods to further validate its generalizability.

Author Contributions

T.A.K. Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. Y.Q.: Resources, Data Curation, Supervision, Project Administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author acknowledges the financial support for this research from the following projects in the Yunnan Provincial transportation sector: YNJTAJB20220662 funded by Yunnan Communications Investment & Construction Group Co., Ltd. (¥688,000); KKF0202302375 and KKF0202402250 funded by Yunnan Highway Science and Technology Research Institute (¥310,000 and ¥189,300, respectively); and KKK0202402040 funded by Yunnan Yunling Expressway Transportation Technology Co., Ltd. (¥315,500).

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TSE | Traffic State Estimation |

| GAT-TCN | Graph Attention Temporal Convolutional Network |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| UKF | Unscented Kalman Filter |

| SKF | Sliding Kalman Filter |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| EDA | Exploratory Data Analysis |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Network |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| CV | Connected Vehicles |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| SSE | Sum of Squared Errors |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

Appendix A

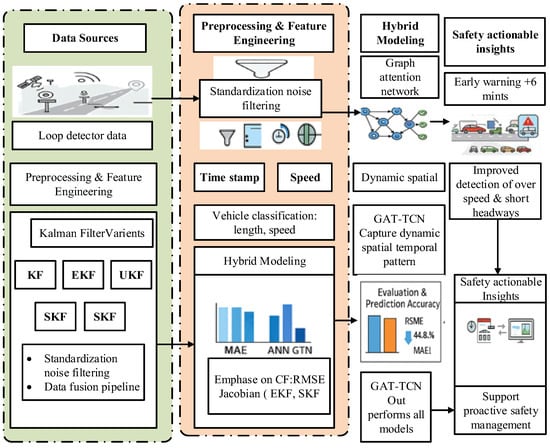

The Figure A1, illustrates the integrated research framework developed for this study. The process begins with raw data sources, such as loop detector data, which undergo comprehensive preprocessing and feature engineering, including standardization, noise filtering, and the extraction of key features like timestamp and speed. This refined data feeds into a dual-path modeling approach: a classical path implementing various Kalman Filter variants (KF, EKF, UKF, SKF) and an advanced path utilizing a Graph Attention Network (GAT) for dynamic spatial modeling. These paths converge in a hybrid modeling phase that performs vehicle classification and integrates models like the ANN, emphasizing metrics such as RMSE. The entire pipeline is designed to generate safety-actionable insights, with the GAT-based hyper-modeling providing critical outcomes like a +6 min early warning for queue spillback and improved detection of over-speeding and short headways, thereby enabling proactive safety management for rural arterial networks.

Figure A1.

Hybrid Modeling Framework for Traffic Safety Prediction and Management.

References

- Pan, Y.A.; Li, F.; Li, A.; Niu, Z.; Liu, Z. Urban intersection traffic flow prediction: A physics-guided stepwise framework utilizing spatio-temporal graph neural network algorithms. Multimodal Transp. 2025, 4, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Naqvi, S.A.A.; Watling, D.; Ngoduy, D. Real-time dynamic traffic control based on traffic-state estimation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasgaonkar, P.P.; Garg, R.D.; Garg, P.K. Vehicle detection and traffic estimation with sensors technologies for intelligent transportation systems. Sens. Imaging 2020, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, Y.; Alemayehu, E.; Schröder, D. Examining car accident prediction techniques and road traffic congestion: A comparative analysis of road safety and prevention of world challenges in low-income and high-income countries. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 6643412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdouli, H.; Hassan, M.S.; Abdelfatah, A. Enhancing Route Guidance with Integrated V2X Communication and Transportation Systems: A Review. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, A.; Koukaras, P.; Tjortjis, C. Advances in traffic congestion prediction: An overview of emerging techniques and methods. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Deng, K.; Gao, J. Traffic flow prediction based on generative adversarial network with hybrid spatio temporal features learning. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Localization for AutonomousDriving Using Statistical Filtering: A GPS Aided Navigation Approach with EKF and UKF. 2022. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1713737/FULLTEXT02.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Biazen, M.A.; Woldeyohannes, A.D.; Gebeyehu, S.G. Simulation models verification and validation: Recent development and challenges: A review. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 2025, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadizadeh, R.; Asgari, M.; Khosravi, Z.; Papadopoulos, Y.; Aslansefat, K. Incorporating Failure of Machine Learning in Dynamic Probabilistic Safety Assurance. In International Symposium on Model-Based Safety and Assessment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, J.J. State Estimation Techniques for Hybrid Dynamical Systems; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Son, H.; Jang, J.; Park, J.; Balog, A.; Ballantyne, P.; Kwon, H.R.; Singleton, A.; Hwang, J. Leveraging advanced technologies for (smart) transportation planning: A systematic review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, S.C.; Nugroho, S.A.; Taha, A.F.; Claudel, C.G. Traffic state estimation for connected vehicles using the second-order Aw-Rascle-Zhang traffic model. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 16719–16733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A. Multi-Source Traffic State Estimation: Exploring Advanced Filtering Algorithms for Rural Arterial Networks. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-5927838/v1 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- ALMahadeen, S. GPS and LiDAR optimizing transformation parameters for localization in autonomous vehicles. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2025, 28, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Abdirahman, A.; Osman Hashi, A.; Mohamed Dahir, U.; Abdirahman Elmi, M.; Mohd Hashim, S.Z. Enhanced Vehicle Tracking: A GPS-GSM-IoT Approach. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2025, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y. A Real-Time Urban Traffic Congestion Prediction Framework Based on Dynamic Risk Field and Multi-Source Data Fusion. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 172471–172495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwo, D.-J.; Cho, T.-S.; Demssie, B.A. Dynamic Modeling and Its Impact on Estimation Accuracy for GPS Navigation Filters. Sensors 2025, 25, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safvat, R.; Keighobadi, J. Increasing performance of INS/GNSS using LSTM-recurrent fuzzy wavelet kalman filter. GPS Solut. 2025, 29, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, S. Implementation of Non-Linear Filtering Techniques for Object Tracking; University of New Orleans: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Samlal, K. Estimating the State of a Dynamically Evolving System; TUDelft: Delft, The Nederland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Janiszewski, D. Sensorless model predictive control of permanent magnet synchronous motors using an unscented kalman filter. Energies 2024, 17, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Alkhammash, E.H. Online adaptive Kalman filtering for real-time anomaly detection in wireless sensor networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Wu, M.; Yuen, K.F. Modelling and assessing long-term urban transportation system resilience based on system dynamics. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 109, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, F.; Shao, H.; Wu, X.; Cheng, Q.; Lam, W. A Physics-Informed Machine Learning Framework for Speed-Flow Prediction: Integrating an S-Shaped Traffic Stream Model with Deep Learning Models. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 180, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.Y.; Wu, H.-C.; Kao, Y.-C. Tensor extended Kalman filter and its application to traffic prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 13813–13829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Ka, E.; Feng, Y.; Ukkusuri, S.V. Network macroscopic fundamental diagram-informed graph learning for traffic state imputation. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2024, 189, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, D.; Wu, H.; Li, K.; Yu, W. TC-GCN: Triple cross-attention and graph convolutional network for traffic forecasting. Inf. Fusion 2024, 105, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, K.K.; Adams, C.A.; Sivanandan, R.; Ackaah, W. Modelling of segment level travel time on urban roadway arterials using floating vehicle and GPS probe data. Sci. Afr. 2022, 15, e01105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veysi, P.; Adeli, M.; Naziri, N.P. Implementation of Kalman filtering and multi-sensor fusion data for autonomous driving. Nuvern Appl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 8, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tavasoli, M.; Sarrafzadeh, A.; Khaleghi, M.; Zakaria, M.; Pasandi, H.B.; Karimoddini, A. Data Communication Challenges of Connected and Automated Vehicles in Rural Areas. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 29220–29251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Developing A Physics-informed Deep Learning Paradigm for Traffic State Estimation; University of Central Florida: Orlando, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Tang, Z.; He, Q.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fan, D.; Guo, Z. Automatic detection and prediction of epileptic EEG signals based on nonlinear dynamics and deep learning: A review. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1630664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, M. Real-Time Safety and Mobility Optimization of Traffic Signals in a Connected-Vehicle Environment; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elassy, M.; Al-Hattab, M.; Takruri, M.; Badawi, S. Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transp. Eng. 2024, 16, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheder, M.Q.; Mohammed, A.A. Real-time traffic monitoring system using IoT-aided robotics and deep learning techniques. Kuwait J. Sci. 2024, 51, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian, S.M.; Mirzahossein, H. Efficiency and safety of traffic networks under the effect of autonomous vehicles. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2024, 48, 1861–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubec, M.; Cingel, M.; Lieskovská, E.; Drliciak, M. Integrating Neural Networks for Automated Video Analysis of Traffic Flow Routing and Composition at Intersections. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).