Reputation-Aware Multi-Agent Cooperative Offloading Mechanism for Vehicular Network Attack Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

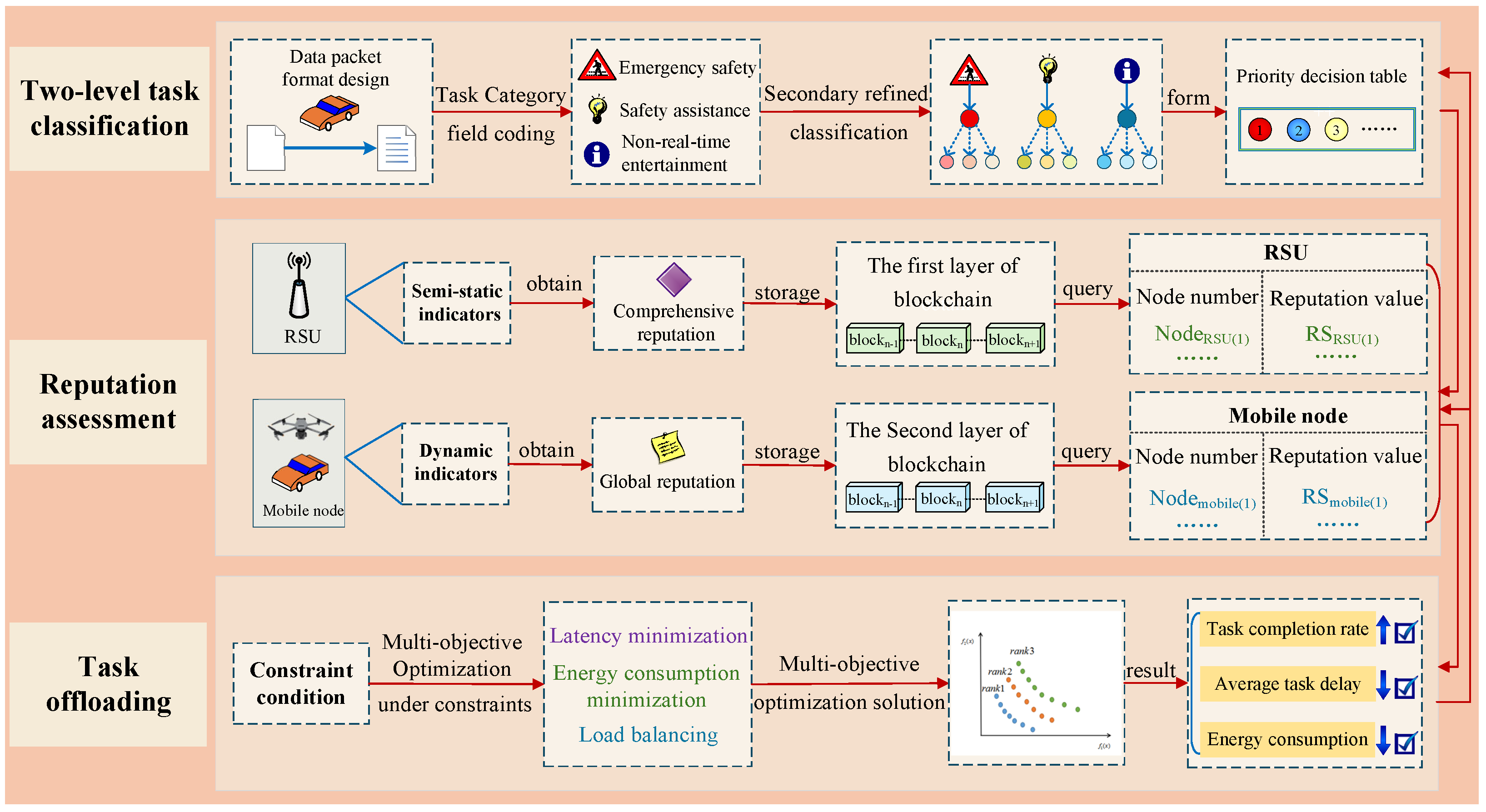

- A two-stage task-classification mechanism is proposed, leveraging multi-dimensional QoS descriptors and combining K-means clustering with a Light-PPO module to refine data packets within the top-level categories of emergency safety, safety assist, and non-real-time entertainment, thereby generating adaptive, service-aware subcategories.

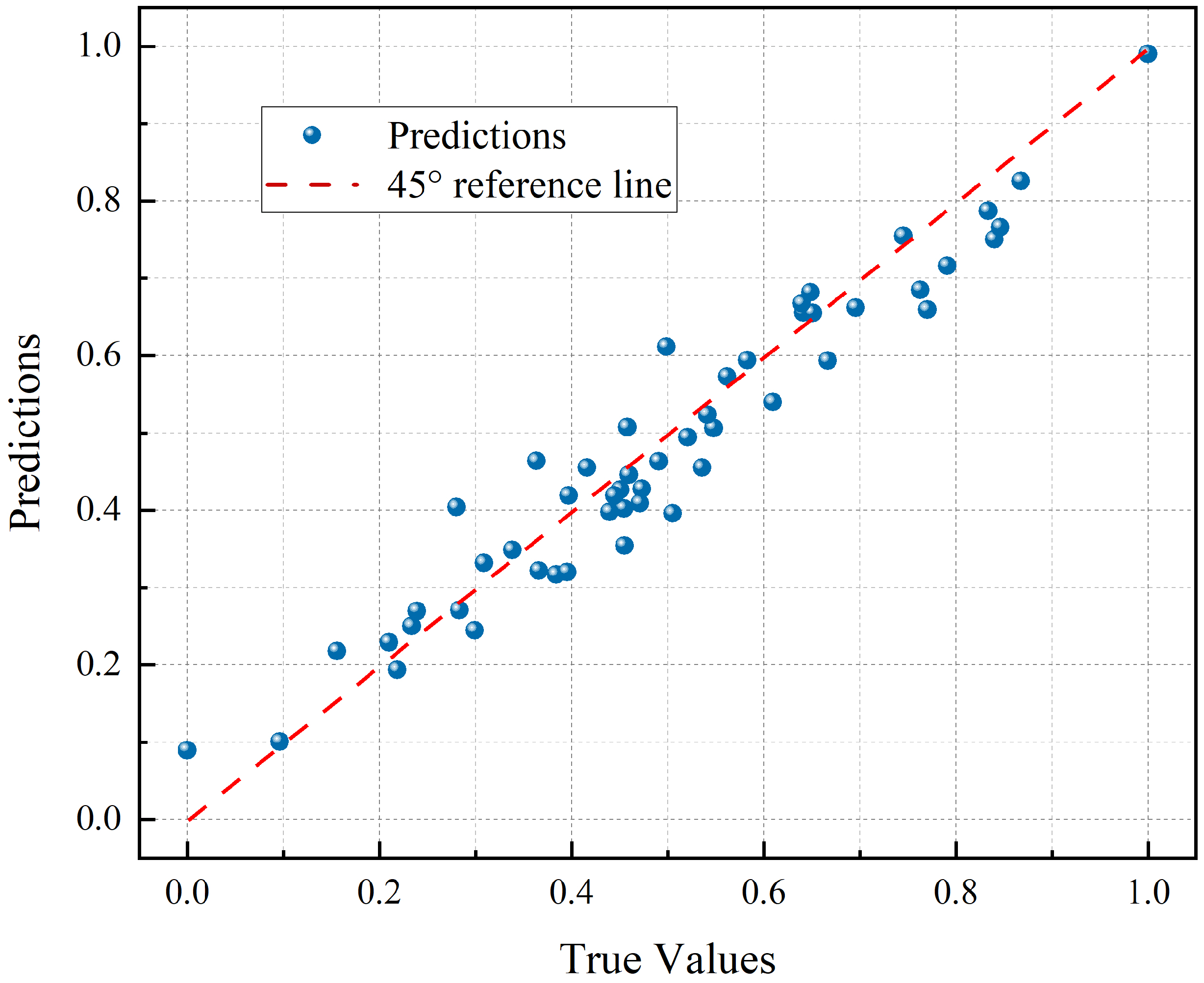

- Differentiated reputation evaluation mechanisms are designed for heterogeneous agents, including RSUs, vehicles, and UAVs. RSU reputations are computed using an LSTM-based model capturing temporal dependencies among service availability, data accuracy, and resource utilization, whereas vehicle and UAV reputations are derived from multi-metric indicators using deep reinforcement learning for adaptive weighting and exponential smoothing, yielding robust local and global trust assessments.

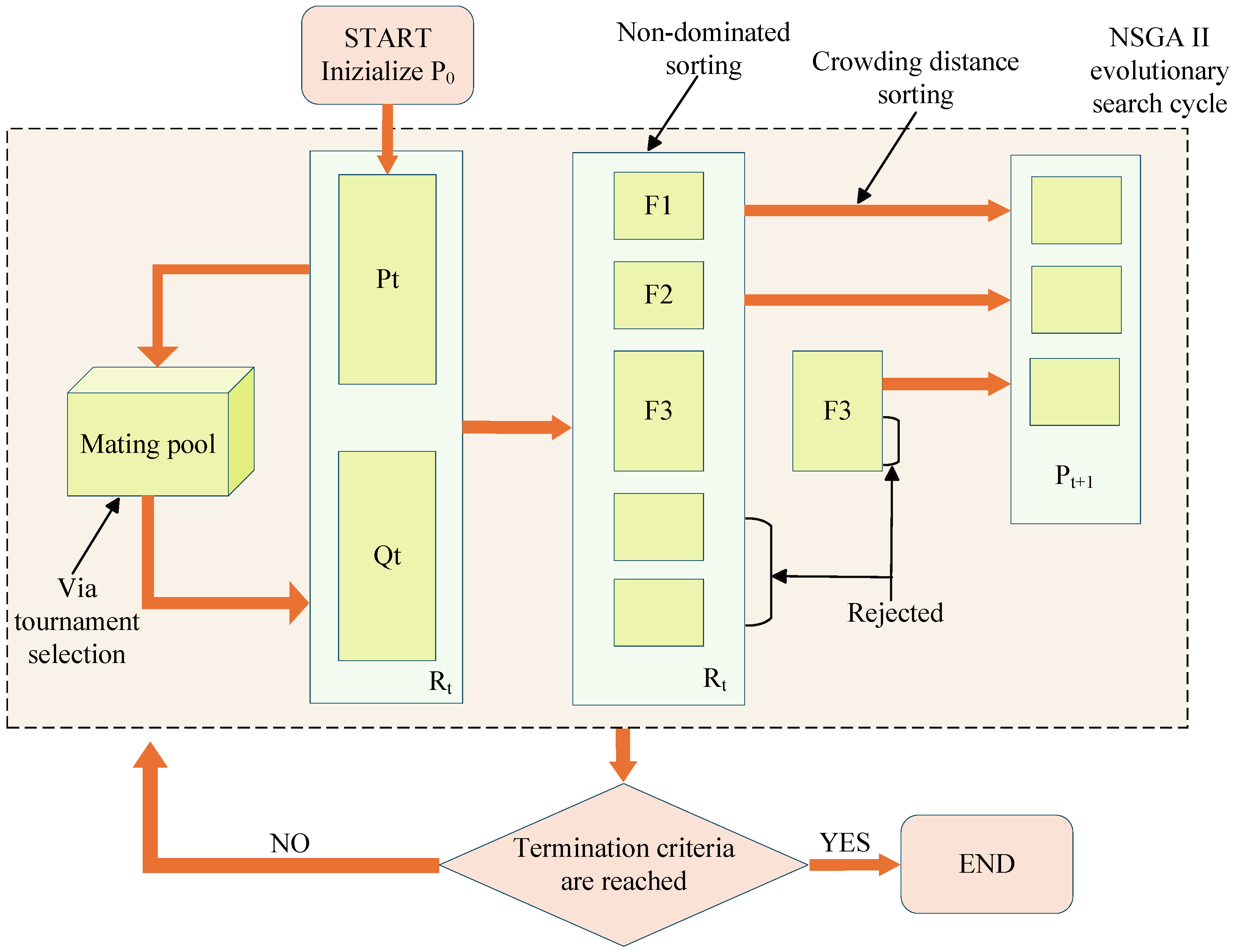

- RSU task offloading is formulated as a multi-objective optimization problem that considers latency, energy consumption, and load balancing. NSGA-II is employed to approximate the Pareto-optimal front, enabling efficient and interpretable task scheduling in heterogeneous IoV environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. Task Offloading Methods Aiming to Minimize Delay and Energy Use

2.2. Cooperative Optimization Offloading Methods for Balancing Multiple Goals

2.3. Task Offloading Methods Combining Reputation Modeling and Security Guarantee Mechanisms

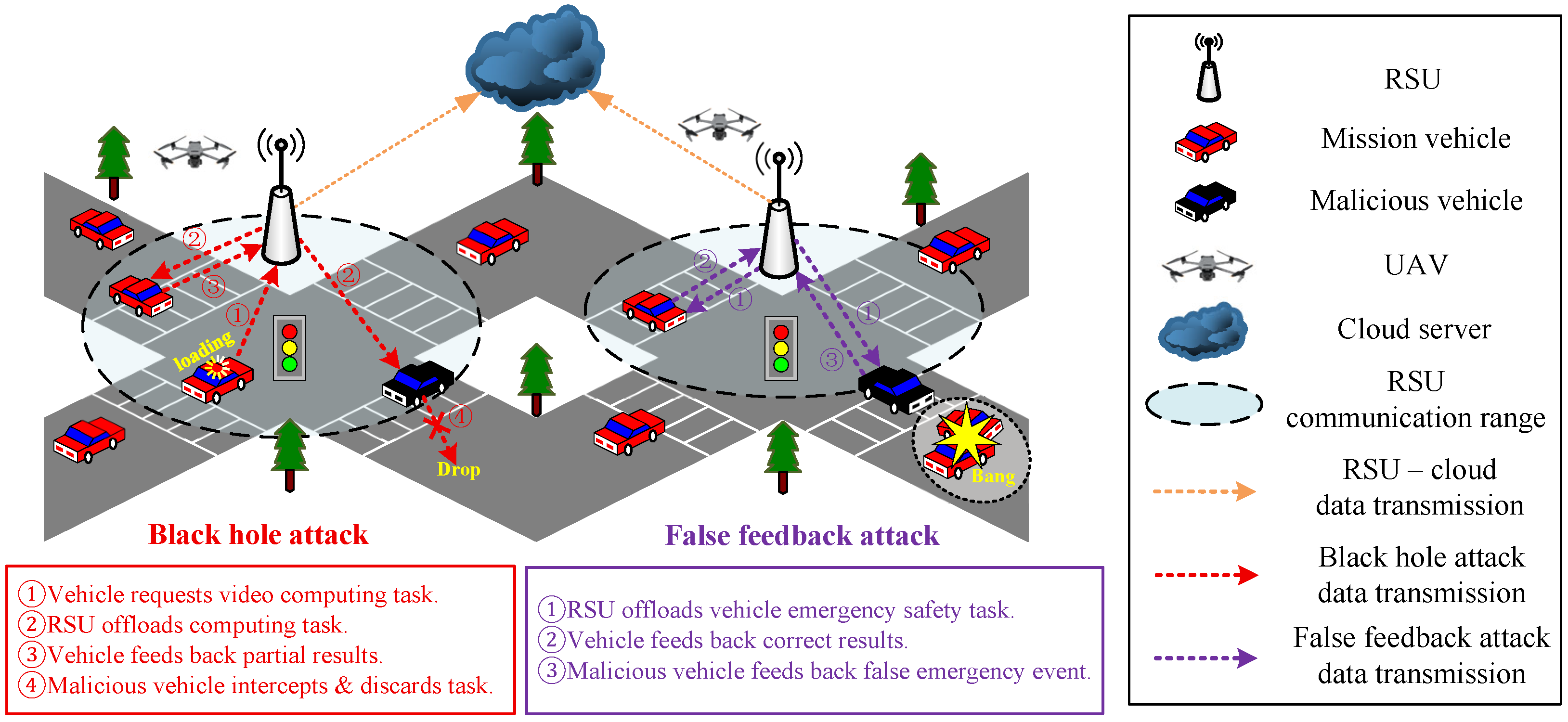

3. Network Attack Scenarios

4. Task Offloading Model for Multi-Objective Optimization Based on Reputation Evaluation

4.1. Task Offloading Classification Model

- Task delay sensitivity (L): The sensitivity score of a task to delay, usually normalized to the range [0, 1]. A larger value indicates that the task has a lower tolerance for delay.

- Computational density (C): Expressed in GOPS/MB, it represents the computing requirement per unit of data volume and measures the computing power consumption for task processing.

- Memory footprint (M): Represents the size of the cache or working set (in MB) required during task execution, measuring the memory usage requirement when the task runs.

- Data entropy value (E): The information compression ratio of the task input data, characterizing the complexity of the data and the processing overhead. A larger value indicates that the data is more difficult to compress and the preprocessing overhead is higher.

4.1.1. Secondary Classification

4.1.2. Light-PPO Lightweight Priority Decision Making

- (1)

- State and Action Spaces

- (2)

- Instantaneous Reward Function

- (3)

- Key Steps

4.1.3. Task Offloading Delay and Energy Consumption

4.2. Multi-Agent Reputation Evaluation Method Based on Two Layer Blockchain

- (1)

- Multi-indicator Based RSU Reputation Evaluation Model

- Service Availability (AV): Defined as the ratio of the number of successfully responded requests to the total number of requests during the most recent time interval , reflecting the RSU’s ability to provide normal service within the specified time. Here, denotes the time decay factor.

- Data Accuracy (DA): Consistency of the traffic sensing data (e.g., vehicle position and speed) provided by the RSU with that from other nearby idle nodes. Multi-source cross-verification is performed on the accuracy of traffic perception data, and the improved Jaccard similarity coefficient is used to check adjacent RSUs: , where is the angle between position data vectors, is the traffic perception data provided by RSU, and is the traffic perception data provided by other neighboring RSUs. The Hampel filter is used to compare and perform anomaly detection on on-board sensors: . Perform dynamic credibility fusion:where is the number of other neighboring RSUs, and is the number of on-board sensors.

- Resource Utilization Rate (RHI): The weighted geometric mean of the current RSU’s CPU usage, memory usage, and bandwidth utilization. A piecewise function is used to normalize the sub-indicators to distinguish the non-linear impact of normal/overload states:where is the normal threshold of each indicator, and controls the overload penalty rate. Weights are dynamically allocated through the entropy weight method: , , where is the information entropy of the i-th indicator, and is the mutual data distribution probability, reflecting the difference in resource importance in different scenarios. The resource utilization rate is calculated as a weighted geometric mean to enhance the sensitivity of low-score indicators, where is a smoothing factor to prevent zero values, and denotes the weight of the i-th indicator:

- Step 1: Calculate the multi-dimensional indicator values of the current RSU

- Step 2: Obtain Weights through LSTM Modeling

- (2)

- Vehicle and UAV Reputation Evaluation Model

- Task Completion Rate (TCR):The ratio of the number of successfully completed tasks to the total number of tasks represents the proportion of successfully completed tasks, measuring the reliability of nodes when executing tasks.

- Processing Delay (PD): The average processing time of tasks. The lower the delay, the higher the reputation of the node.where is the processing delay of the i-th task and n is the total number of tasks.

- Error Rate (ER): The ratio of the number of tasks that failed or had errors to the total number of tasks represents the frequency of task failures or errors. Nodes with a higher error rate have a lower reputation.

- Feedback Score (FS): The evaluation of its task performance by other nodes, usually a score between −1 and 1.where is the feedback score of the j-th node for the task, and m is the number of scores.

4.3. Transformation and Modeling of Multi-Objective Optimization Task Offloading Problem

- Delay Constraint: The total delay in task execution is , which mainly includes the communication delay task (that is, the time to transmit from the offloading node j to the idle node of the edge or the cloud) and the computing delay (that is, the processing time of the task on the target node), where , is the task computing complexity (CPU cycles) and is the computing capability (GHz) of the target node.The constraint condition is as follows:where is the delay threshold.

- Reputation Constraint: The reputation constraint condition is as follows:where is the reputation threshold.

- Computing Resource Constraint: The computing resource constraint of node j:where is the task computing requirement and is the currently available computing resource of node j.

- Minimization of Delay: For task i, the total delay objective function can be expressed aswhere represents the task priority, is the local computing delay, is the offloading delay, and is the delay penalty term.

- Minimization of Energy Consumption: The total energy consumption objective function can be expressed aswhere represents the task priority, is the local energy consumption, is the offloading energy consumption, and is the energy consumption penalty term.

- Load Balance: For each available node j, is the set of tasks to be offloaded, indicates whether task i is allocated to node j, is the computing load of task i, and is the maximum computing capability of node j. Then, the absolute load allocated to node j is , and its relative load rate can be expressed as . The objective of the load balance is to minimize the variance of the loads of each node, where :

5. Simulation Experiments and Performance Analysis

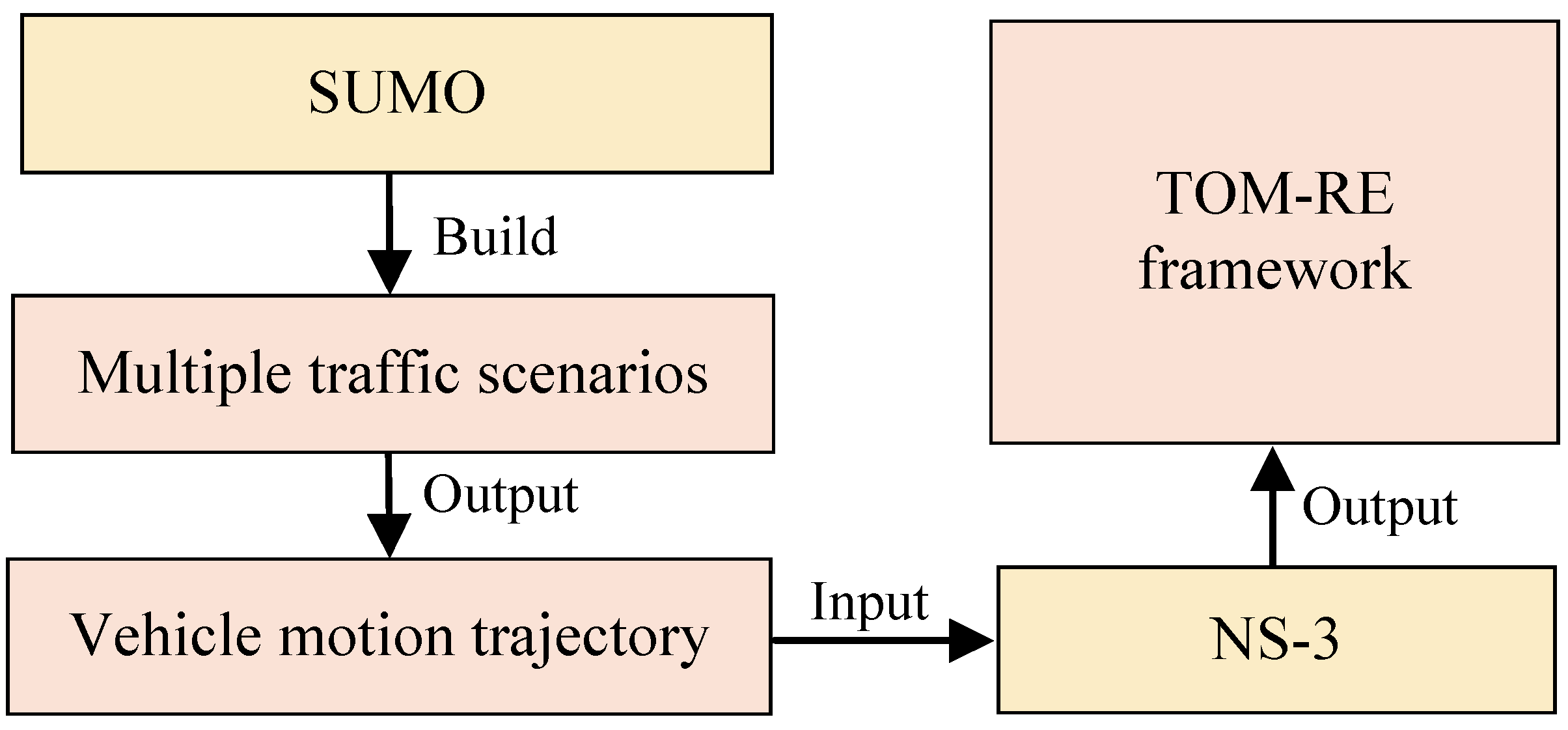

5.1. Simulation Experiment Setup

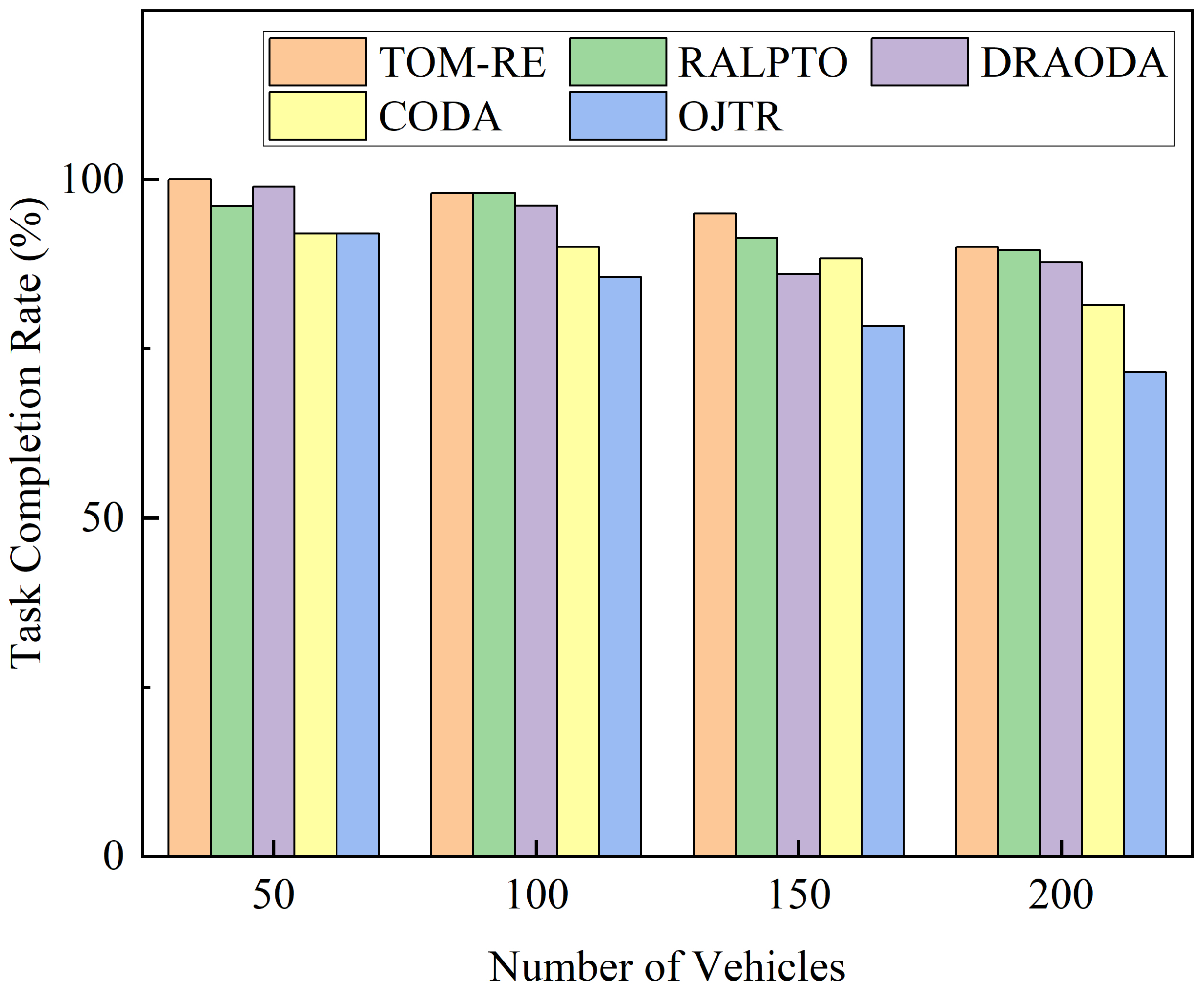

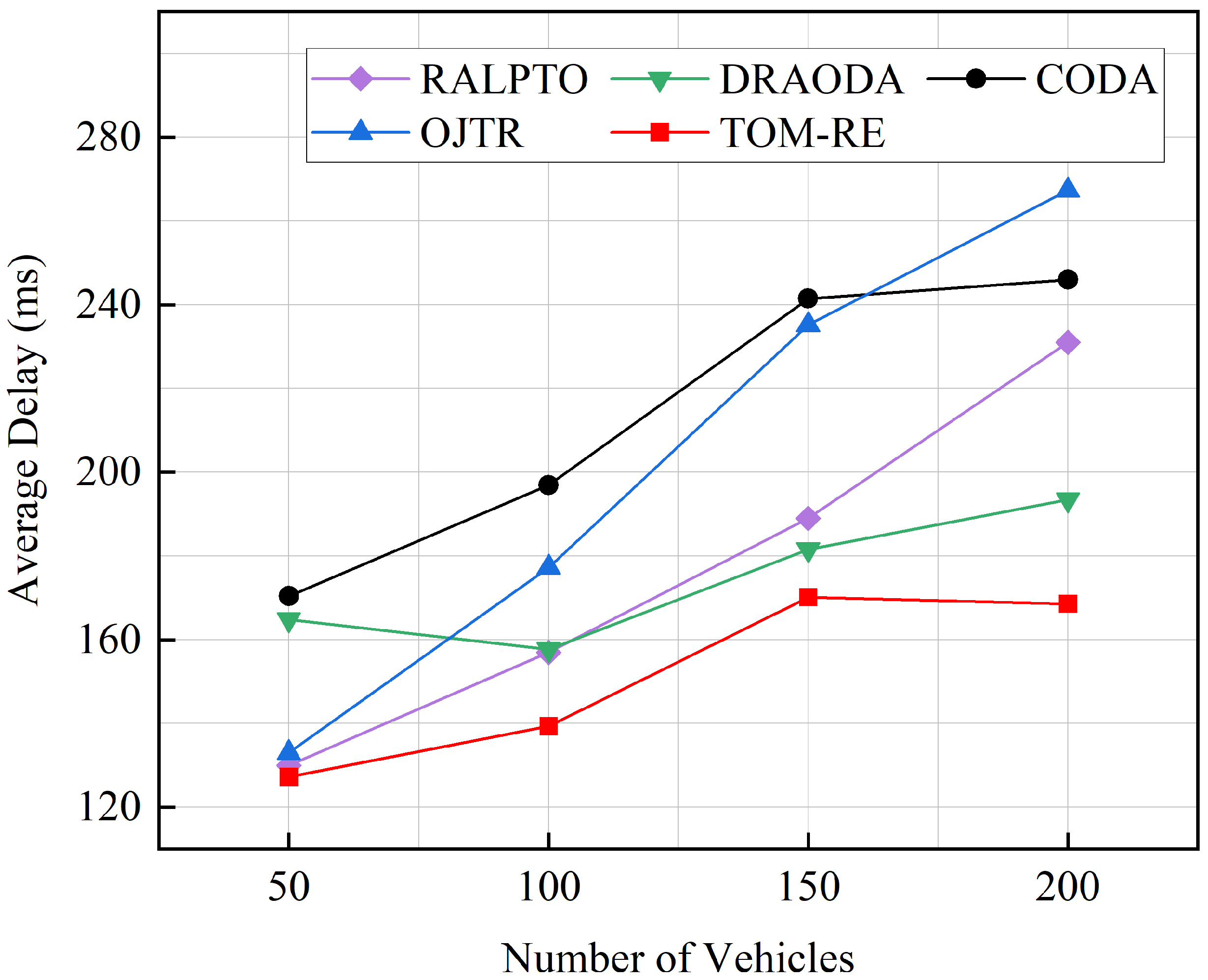

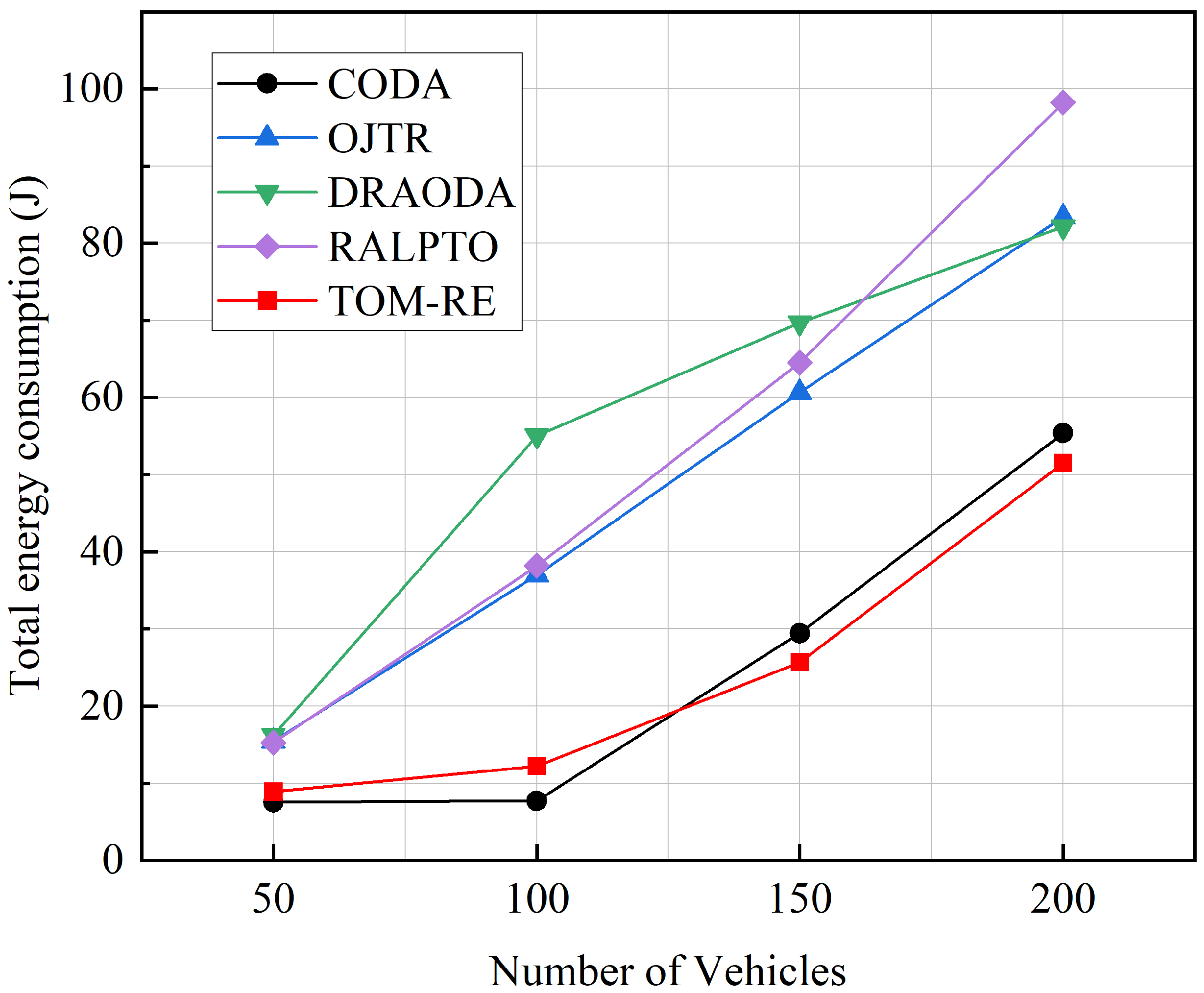

5.2. Experimental Results and Performance Analysis

- RALPTO [18]: A partially offloading algorithm executed in a distributed fashion that leverages RSU-assisted learning and is built on multi-armed bandit theory.

- OJTR [19]: A heuristic task offloading optimization method combining reinforcement learning and a greedy-based decomposition approach.

- CODA [23]: A distance-driven computation resource allocation scheme designed to achieve load balancing.

- DRAODA [46]: A resource allocation and offloading decision algorithm based on the deep deterministic policy gradient, developed to improve the handling of dynamic and complex problems by DRL methods.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bréhon–Grataloup, L.; Kacimi, R.; Beylot, A.L. Mobile edge computing for V2X architectures and applications: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2022, 206, 108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, X.; Xu, H.; Song, T.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Y. Joint offloading decision and resource allocation in vehicular edge computing networks. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, P.; Hudson, N.; Chantem, T.; Khamfroush, H. Deadline-aware task offloading for vehicular edge computing networks using traffic light data. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2024, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wu, Q.; Fan, P.; Cheng, N.; Chen, W.; Letaief, K. DRL-based federated self-supervised learning for task offloading and resource allocation in isac-enabled vehicle edge computing. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 11, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cen, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, C. Optimal Task Offloading Strategy for Vehicular Networks in Mixed Coverage Scenarios. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Hu, G.; Hou, F. Reinforcement learning enabled dynamic resource allocation in the internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 4957–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Zheng, F.; Hong, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, L. A dynamic resource allocation model based on SMDP and DRL algorithm for truck platoon in vehicle network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 10295–10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A., Jr.; da Costa, J.B.D.; Rocha Filho, G.P.; Villas, L.A.; Guidoni, D.L.; Sampaio, S.; Meneguette, R.I. HARMONIC: Shapley values in market games for resource allocation in vehicular clouds. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 149, 103224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Huang, X.; Kang, J.; Ding, J.; Maharjan, S.; Gjessing, S.; Zhang, Y. Cooperative resource management in cloud-enabled vehicular networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 7938–7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, J. Intelligent Resource Allocation Scheme Using Reinforcement Learning for Efficient Data Transmission in VANET. Sensors 2024, 24, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Cai, L.; Feng, J.; Pei, Q.; Shi, W. Resource optimization of MAB-based reputation management for data trading in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 5278–5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Chen, Y.; Ding, M.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.P. Deep reinforcement learning for online resource allocation in IoT networks: Technology, development, and future challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Alam, M.; Hu, W. Blockchain-based secure computation offloading in vehicular networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 4073–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, W.; Liao, Z.; Sherratt, S.R.; Kim, G.J.; Alfarraj, O.; Alzubi, A.; Tolba, A. A probability preferred priori offloading mechanism in mobile edge computing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 39758–39767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgchenani, A.; Mashhadi, F.; Tarchi, D.; Salinas Monroy, S.A. Multi-objective computation sharing in energy and delay constrained mobile edge computing environments. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2020, 20, 2992–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Ren, Z.; Wang, J.; Cheng, W.; Ren, Y.; Chen, K.C.; Zhang, H. Reliable computation offloading for edge-computing-enabled software-defined IoV. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 7097–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabbaz, M. Deadline-Constrained RSU-to-Vehicle Task Offloading Scheme for Vehicular Fog Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 14955–14961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, W.; Ni, Q.; Sun, Y. Road Side Unit-Assisted Learning-Based Partial Task Offloading for Vehicular Edge Computing System. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 5546–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Su, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Huang, W.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y. Joint Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for Vehicular Edge Computing Based on V2I and V2V Modes. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 4277–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Wu, M.; Gu, N.; Sherratt, R.S.; Ghosh, U.; Sharma, P.K. Joint Optimization of Computation Offloading and Resource Allocation Considering Task Prioritization in ISAC-Assisted Vehicular Network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 29523–29532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Task Offloading for Vehicular Edge Computing with Flexible RSU-RSU Cooperation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 7712–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Hua, M.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, B.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y. Game-Based Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for Vehicular Edge Computing with Edge-Edge Cooperation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 7857–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Xu, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, J. Task Migration and Resource Allocation Scheme in IoV with Roadside Unit. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2023, 20, 4528–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Cao, X.; Khosravi, M.R.; Alex, L.T.; Qi, L.; Dou, W. Game Theory for Distributed IoV Task Offloading with Fuzzy Neural Network in Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 4593–4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lv, T.; Lin, Z.; Zeng, J. Energy-Delay Minimization of Task Migration Based on Game Theory in MEC-Assisted Vehicular Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 8175–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Hu, T.; Zhao, W. Reliable task offloading mechanism based on trusted roadside unit service for internet of vehicles. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 139, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, A.; Mohammed, M.A.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; Nedoma, J.; Martinek, R.; Tiwari, P.; Kumar, N. Fully Homomorphic Enabled Secure Task Offloading and Scheduling System for Transport Applications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 12140–12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Wu, G.; Chen, H.; Sun, S. Joint optimization of task offloading and resource allocation based on differential privacy in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2021, 9, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvini, M.; Javan, M.R.; Mokari, N.; Abbasi, B.; Jorswieck, E.A. AoI-Aware Resource Allocation for Platoon-Based C-V2X Networks via Multi-Agent Multi-Task Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 9880–9896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Guo, C.; Hu, R.Q.; Qian, Y. Blockchain-Inspired Secure Computa-tion Offloading in a Vehicular Cloud Network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 14723–14740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Yi, J.; Wang, X.; Xiao, H.; Xu, C. Interaction Trust-Driven Data Distribution for Vehicle Social Networks: A Matching Theory Approach. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 4071–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wu, L.; Cao, S.; Hu, X.; Xue, S.; Wu, D.; Li, Q. Task offloading with task classification and offloading nodes selection for MEC-enabled IoV. Acm Trans. Internet Technol. (TOIT) 2021, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Raza, S.; Mirza, M.A.; Aziz, A.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, W.U.; Li, J.; Han, Z. A survey on vehicular task offloading: Classification, issues, and challenges. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 4135–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Hu, B.J.; Xia, E. Dependency-aware task offloading and service caching in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 13182–13197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Geng, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, H. A Differential Privacy Based Task Offloading Algorithm for Vehicular Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 30921–30932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Du, J.; Zhu, X. Mobility-Aware Task Offloading and Resource Allocation in UAV-Assisted Vehicular Edge Computing Networks. Drones 2024, 8, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, M.; Ota, K.; Liu, A. ActiveTrust: Secure and trustable routing in wireless sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2016, 11, 2013–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Mohammadani, K.; Bashir, A.K.; Omar, M.; Jones, A.; Hassan, F. Secure and reliable routing in the Internet of Vehicles network: AODV-RL with BHA attack defense. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 139, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Gu, Z.; Ban, Z. Restraining false feedbacks in peer-to-peer reputation systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC 2007), Irvine, CA, USA, 17–19 September 2007; pp. 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.; Xiao, F.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Z. A group-vehicles oriented reputation assessment scheme for edge VANETs. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2024, 12, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, P.A.; Behrisch, M.; Bieker-Walz, L.; Erdmann, J.; Flötteröd, Y.P.; Hilbrich, R.; Lücken, L.; Rummel, J.; Wagner, P.; Wiessner, E. Microscopic traffic simulation using SUMO. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanile, L.; Gribaudo, M.; Iacono, M.; Marulli, F.; Mastroianni, M. Computer network simulation with ns-3: A systematic literature review. Electronics 2020, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Liang, X.; Zhao, D.; Huang, J.; Xu, X.; Dai, B.; Miao, Q. Deep reinforcement learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 5064–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, B.; Müller, T.; Vietz, H.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. A survey on long short-term memory networks for time series prediction. Procedia CIRP 2021, 99, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Wong, V.W.S. Deep reinforcement learning for task offloading in mobile edge computing systems. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2020, 21, 1985–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhang, J.; Hu, S.; Luan, T.H.; Fan, P. Joint Task Migration and Resource Allocation in Vehicular Edge Computing: A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 9476–9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coding Scheme | Task Category | Typical Scenarios (Examples) |

|---|---|---|

| 0x00 | Urgent Safety | Collision Warning, Automatic Braking, Emergency Call |

| 0x01 | Safety Assistance | Lane Keeping, Blind Spot Monitoring, Tire Pressure Monitoring |

| 0x02 | Non-real-time Entertainment | OTA Updates, Streaming Media, Navigation Data Download |

| 0x03-0xFF | Reserved | Legacy Devices or Unclassified Tasks |

| Field Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Packet ID | Unique identifier of each data packet, ensuring traceability in transmission logs (e.g., Packet_000123). |

| Source Node ID | Identifier of the node that generated the task (Vehicle, RSU, or UAV) (e.g., RSU_07). |

| Destination Node ID | Identifier of the node receiving the offloaded task (e.g., UAV_02). |

| Task Type Label | Encoded category of the computational task, supporting classification-based offloading (e.g., 0x00 = emergency-safety, 0x01 = safety-assist, 0x02 = non-real-time entertainment). |

| Transmission Delay | End-to-end communication delay in milliseconds (ms), indicating network latency (e.g., 25.6). |

| Throughput | Data transmission rate during task offloading (Mbps) (e.g., 8.2). |

| Packet Loss Rate | Ratio of lost packets during transmission, reflecting network reliability (e.g., 0.005). |

| Energy Consumption | Energy consumed for task processing or transmission (J) (e.g., 0.82). |

| Node Resource State | Current resource utilization of the node, including CPU and memory usage (e.g., CPU = 0.78, Memory = 0.62). |

| Attack Flag | Indicator of malicious behavior in the current record (e.g., 0 = normal, 1 = blackhole, 2 = false feedback). |

| Vehicle State Information | Real-time motion state of vehicles, including position coordinates and speed (e.g., Position = (128.52, 64.38), Speed = 14.6 m/s). |

| Timestamp | Simulation time of data generation or task completion (ms) (e.g., 152.38). |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Road area/m2 | |

| Number of vehicles | 50/100/150/200 |

| Number of UAVs | 3 |

| WLAN protocol | 802.11a |

| Node mobility model | trace-based mobility |

| Channel type | YansWifiChannel |

| Transmission power/dBm | [15, 20] |

| Transmission rate/Mbps | 54 |

| Simulation duration/min | [10, 30] |

| Proportion of malicious vehicles | 10% |

| Vehicle speed/m·s−1 | [5, 15] |

| RSU coverage radius/m | 500 |

| Reputation update period/min | 10 |

| Message frequency/(counts·) | [10, 30] |

| (a) LSTM | |

| Parameter | Value |

| window_size | 60 |

| hidden_size | 512 |

| dropout | 0.2 |

| batch_size | 256 |

| lr | |

| grad_clip | 1.0 |

| patience | 50 |

| weight_decay | |

| (b) DQN | |

| Parameter | Value |

| epsilon | 1.0 |

| epsilon_min | 0.01 |

| epsilon_decay | 0.995 |

| learning_rate | 0.001 |

| gamma | 0.9 |

| update_target_frequency | 10 |

| batch_size | 64 |

| hidden_layers | [256, 128] |

| RSU_ID | MSE | MAE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.01055 | 0.08199 | 0.91192 |

| 4 | 0.00967 | 0.07901 | 0.92180 |

| 8 | 0.00911 | 0.07541 | 0.92501 |

| 12 | 0.00940 | 0.07619 | 0.92580 |

| 16 | 0.01034 | 0.08124 | 0.91503 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, L.; Fan, N.; Zhang, J.; Shang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Fan, W. Reputation-Aware Multi-Agent Cooperative Offloading Mechanism for Vehicular Network Attack Scenarios. Vehicles 2025, 7, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040150

Ye L, Fan N, Zhang J, Shang Y, Shi Y, Fan W. Reputation-Aware Multi-Agent Cooperative Offloading Mechanism for Vehicular Network Attack Scenarios. Vehicles. 2025; 7(4):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040150

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Liping, Na Fan, Junhui Zhang, Yexiong Shang, Yu Shi, and Wenjun Fan. 2025. "Reputation-Aware Multi-Agent Cooperative Offloading Mechanism for Vehicular Network Attack Scenarios" Vehicles 7, no. 4: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040150

APA StyleYe, L., Fan, N., Zhang, J., Shang, Y., Shi, Y., & Fan, W. (2025). Reputation-Aware Multi-Agent Cooperative Offloading Mechanism for Vehicular Network Attack Scenarios. Vehicles, 7(4), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040150