Abstract

This study investigates the synthesis and photochemical behavior of a series of (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadienes with different aromatic substituents. Despite their simple structure and straightforward preparation, detailed studies of their photochemical properties, especially UV light-induced (E) to (Z) isomerization, are scarce. Our results demonstrate that these compounds can efficiently undergo photo-triggered geometric changes, highlighting their potential as functional units in photochemical applications. The findings underline the significance of extended conjugation in managing excited-state processes, providing new insights into the dynamics of photoinduced transformations in conjugated diene systems. Additional computational analyses show how geometric modifications influence conformational energies in the synthesized compounds. Overall, these results improve understanding of structure–reactivity relationships and lay the foundation for designing photoresponsive materials based on (E) and (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene frameworks, with promising applications in photochemistry and materials science.

1. Introduction

Phenylbutanoids represent a structurally diverse and biologically significant class of naturally occurring compounds, characterized by a phenyl ring connected to a four-carbon aliphatic side chain [1]. Closely related to phenylpropanoids, they differ by the addition of a single methylene unit, a seemingly minor change that significantly alters their physicochemical properties, metabolic behavior, and biological activities. This variation often affects polarity, conformational flexibility, and molecular recognition, thereby shaping their pharmacological profiles. Phenylbutanoids are especially abundant in the Zingiberaceae family, plants valued for both culinary and medicinal uses [2]. In this context, phenylbutanoids contribute to the characteristic organoleptic properties such as aroma and flavor of these plants and have been implicated in a wide array of bioactivities, including antioxidant [3], anti-inflammatory [4] and neuroprotective effects [5]. Such activities make them of great interest for drug discovery and nutraceutical development. Beyond their biological relevance, phenylbutanoids offer a synthetically versatile scaffold [6]. Their structural simplicity, combined with functionalizable sites, makes them amenable to various chemical transformations. Consequently, they have found increasing utility as intermediates in the synthesis of more complex bioactive molecules and in the development of functional materials [7]. A particularly intriguing but underexplored subclass of phenylbutanoids, is represented by (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadienes. These compounds feature a phenyl ring at the 1-position of the butadiene backbone, introducing an extended π-conjugated system that imparts distinct electronic and photophysical properties. Such conjugation not only modulates their chemical reactivity but also renders them responsive to light, positioning them as promising candidates for applications in photochemistry, molecular switches, and materials science [8].

The aryl group in (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene plays a critical role in modulating the molecule’s reactivity across a variety of chemical transformations. This influence stems largely from the aromatic ring’s capacity to redistribute electron density throughout the conjugated system [9]. Depending on the electronic nature of its substituents, the phenyl ring can act as either an electron-donating or electron-withdrawing group, impacting both the kinetics and thermodynamics of reaction pathways [10].

In Diels–Alder cycloadditions, for example, the phenyl substituents strongly influence regioselectivity and reactivity of the diene [11]. Similarly, in 1,3-cyclotetramerization reactions involving butadiene and electron-deficient dienophiles under nickel catalysis, the phenyl ring and its substituents significantly affect chemoselectivity [12]. These effects arise from a combination of π-delocalization and steric hindrance, highlighting the strategic utility of substituted aromatics in transition-metal-catalyzed processes [13].

(E)-1-(3,4-dimethoxy phenyl)-1,3-butadiene, a natural product isolated from Zingiber cassumunar, exemplifies the potential of these molecules, having demonstrated a broad spectrum of biological effects, including antioxidant [14] and anti-inflammatory [15] properties. Interestingly, although these compounds are structurally straightforward and synthetically accessible, there remains a scarcity of systematic studies focusing on their photochemical behavior, particularly regarding their capacity for photoinduced (E) to (Z) isomerization, a process well-known in other conjugated systems. The ultraviolet (UV)-induced geometrical isomerization of olefins from the thermodynamically favoured (E) to the less stable (Z) configuration represents one of the most extensively investigated photochemical transformations [16]. Photoisomerization mediated via intramolecular triplet energy transfer is particularly well-documented and mechanistically understood [17].

Among olefins, (E)-ferulic acid, a hydroxycinnamic acid widely distributed in the plant kingdom, exhibits a broad range of pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, and antineoplastic activities [18]. Numerous studies have addressed the photochemical isomerization of (E)-ferulic acid to its corresponding (Z) isomer under UV irradiation [19]. While cinnamic acids are biosynthetically produced predominantly in the (E) form, exposure to UV light can promote (E) to (Z) photoisomerization, generating configurationally distinct (Z)-isomers not typically encountered in nature [20]. Notably, in certain cases, these (Z)-isomers exhibit superior bioactivity relative to their (E) analogues [21].

In previous works, we demonstrated that the natural compounds (E)-dehydrozingerone ((E)-DHZ) and (E)-dehydrozingerone-OMe ((E)-DHZ-OMe), structurally related to curcumin, display significant biological activity across multiple assays including potent inhibition of α-synuclein fibrillogenesis [22], marked antioxidant activity [23], and cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines [24]. Recently, we reported the first study on the synthesis of (Z)-DHZ and (Z)-DHZ-OMe via photoisomerization of their corresponding (E) isomers [25]. Our results demonstrate that both natural compounds efficiently undergo (E) to (Z) isomerization upon UV irradiation at 254 nm in deuterated acetone solution. Comprehensive studies aimed at evaluating and comparing their biological activities with those of the (Z)-configured counterparts are currently underway.

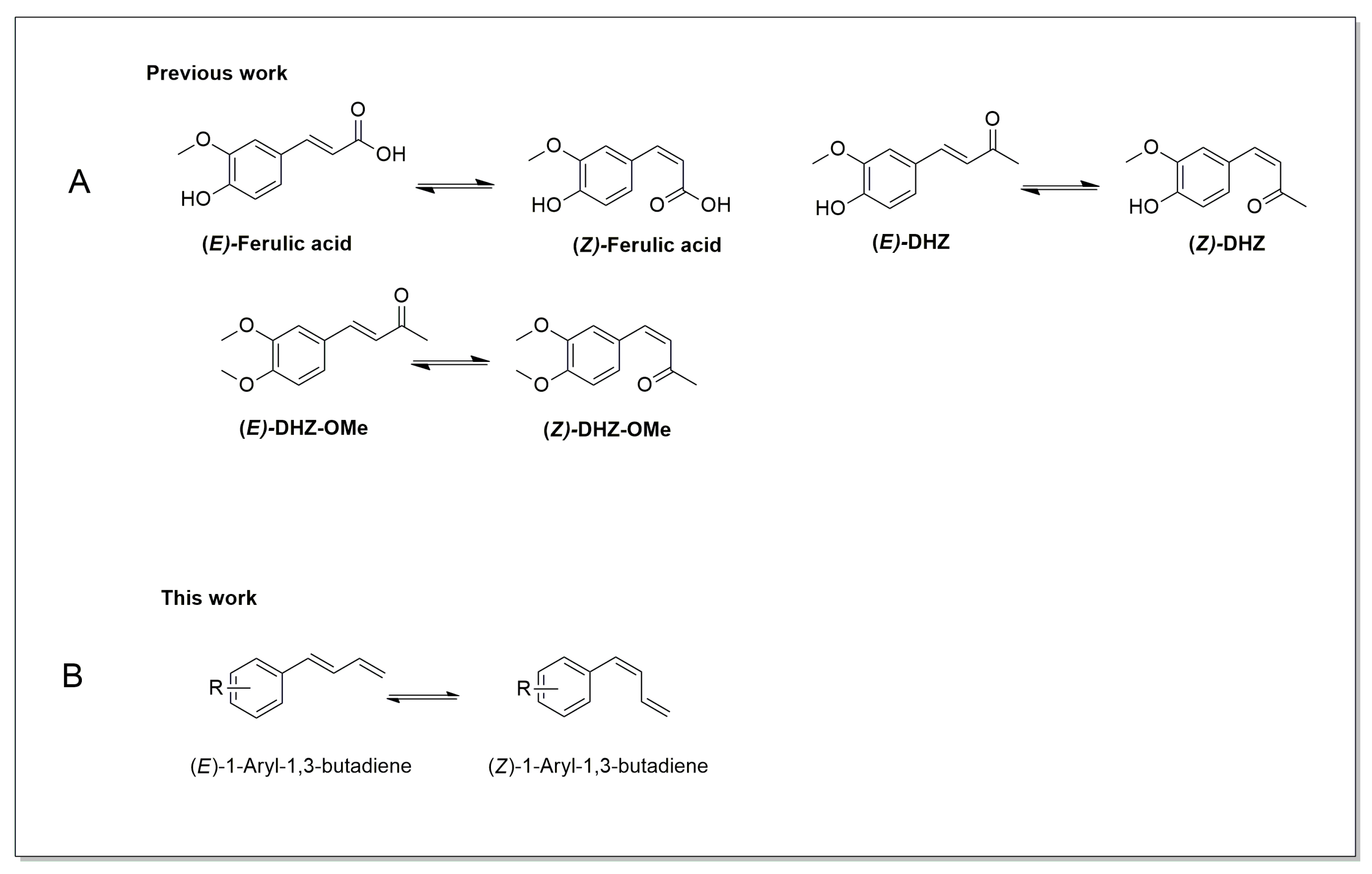

A structural comparison of (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadienes, (E)-ferulic acid, and (E)-DHZ highlights shared features, notably an aromatic ring bearing substituents and a conjugated alkenyl chain (Figure 1). Despite this common scaffold, their functional groups differ substantially: ferulic acid contains a carboxylic acid, DHZ and DHZ-OMe possess a ketone, and 1-aryl-1,3-butadienes terminate in a methylidene group within the conjugated diene system. These variations in functionalization likely modulate electronic distribution, conjugation, and molecular reactivity during photochemical processes, particularly with respect to (E) → (Z) photoisomerization.

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structures of (A) (E)-ferulic acid, (Z)-ferulic acid, (E)-DHZ, (Z)-DHZ, (E)-DHZ-OMe, (Z)-DHZ-OMe. (B) (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene and (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene.

The π-electron system of the conjugated (E) diene is excited by irradiation upon UV light, allowing for rotation around the central double bond and enabling the formation of the (Z) isomer. When carried out under controlled conditions, such as specific wavelengths and appropriate solvents, this method can provide the (Z) isomers in appreciable yields, often with minimal byproducts. This photochemical approach offers several advantages: it is operationally simple, does not require expensive reagents or catalysts, and can be performed at ambient temperature. Moreover, it enables access to (Z)-configured dienes that may be thermodynamically disfavored and therefore inaccessible via thermal or base-catalyzed methods. Enabling the efficient and selective conversion of (E) to (Z) isomers, photoisomerization not only fills a gap in current synthetic methodologies but also opens new avenues for the systematic study of (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadienes, including their reactivity, stability, and potential applications in material science and bioactive molecules development. Building upon these findings, the present study focuses on design, synthesis, characterization and (E) to (Z) photoisomerization of a series of (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene derivatives, bearing electronically and sterically diverse substituents on the aryl ring.

The synthesis of a variety of (Z)-configured 1-aryl-1,3-butadienes has been reported in the literature [26]. However, in most of these cases, the (Z) isomers were not obtained in pure form but reported as components of mixtures with their corresponding (E) isomers, without efforts toward their selective synthesis or full structural isolation. Moreover, the characterization data provided for the (Z) isomers are often incomplete or ambiguous, limiting the reliability of structural assignments and the understanding of their physicochemical properties. Another significant limitation present in the literature lies in the synthetic approaches which frequently indirect, involving multi-step procedures, low overall yields, and the use of costly or non-readily available reagents [27]. Equally important is the comprehensive characterization of these compounds through spectroscopic and analytical techniques, which would not only confirm their structures unambiguously but also provide insight into their electronic and conformational properties. Overall, these limitations highlight the need to develop direct, efficient, and economically viable synthetic strategies for the preparation of pure (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadienes. Such advancements could significantly enhance the utility of (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadienes in various fields, including organic and medicinal chemistry.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Methods

General reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany, and used without further purification. 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded in deuterated CHCl3, DMSO, MeOH, or acetone solutions at 600 and 150 MHz, respectively, using a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III HD NMR spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Full characterization data, including copies of the 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra (see Supporting Information), have been provided for all new compounds. Chemical shifts are expressed in ppm (δ); multiplicities are indicated by s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet), or dd (doublet of doublets). Elemental analysis was performed with a Perkin Elmer 240 C elemental analyzer (Waltham, MA, USA). Microwave reactions were carried out on an MW instrument (CEM-Discover SP MW, Matthews, NC, USA). Flash chromatography was carried out with silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh) (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA), eluting with an appropriate solvent in the specified v:v proportions. Photoisomerizations were conducted using spectroline ENF-240C/FE UV lamps operating at 254 or 365 nm with an intensity of 390 μW/cm2 (Fischer Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). Reactions were monitored by 1H-NMR and analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using 0.25 mm thick silica gel plates (60 F 254) (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany). UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 35 UV/VIS spectrometer (Shelton, CT, USA). Melting points were determined with a 530 apparatus (Büchi, Flawil, Switzerland) and are uncorrected. The purity of new compounds was estimated to be >95% based on 1H-NMR spectral analysis. In silico analysis: model compounds were constructed using standard bond lengths and angles from a fragment database, and subsequently optimized with Gaussian 16 [28]. Representative minimum-energy conformations were obtained using the M06-2X functional with the 6-311+G(2d,p) basis set, employing the SMD solvation model for methanol. All optimizations consistently employed the M06-2X/6-311+G(2d,p) level of theory. Visual inspection and structural analysis were carried out using Gaussian View version 6 and UCSF Chimera 1.18 [29]. Computational modeling was conducted on an EXXACT Tensor Workstation TWS-1686525.

2.2. General Procedure for Synthesis of (E)-1a-g

To a solution of compounds 3a-g (Scheme 1) (1 eq), in dioxane (10 mL), anhydrous CuSO4 (6 eq) was added at room temperature. The solution was then stirred under microwave irradiation at 120 °C, at 300 W power, for 10 min. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was washed with water (10 mL), extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL), and the organic phase evaporated. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using a 1:2 mixture of diethyl ether and petroleum ether as the eluent affording the (E)-1a-g derivatives.

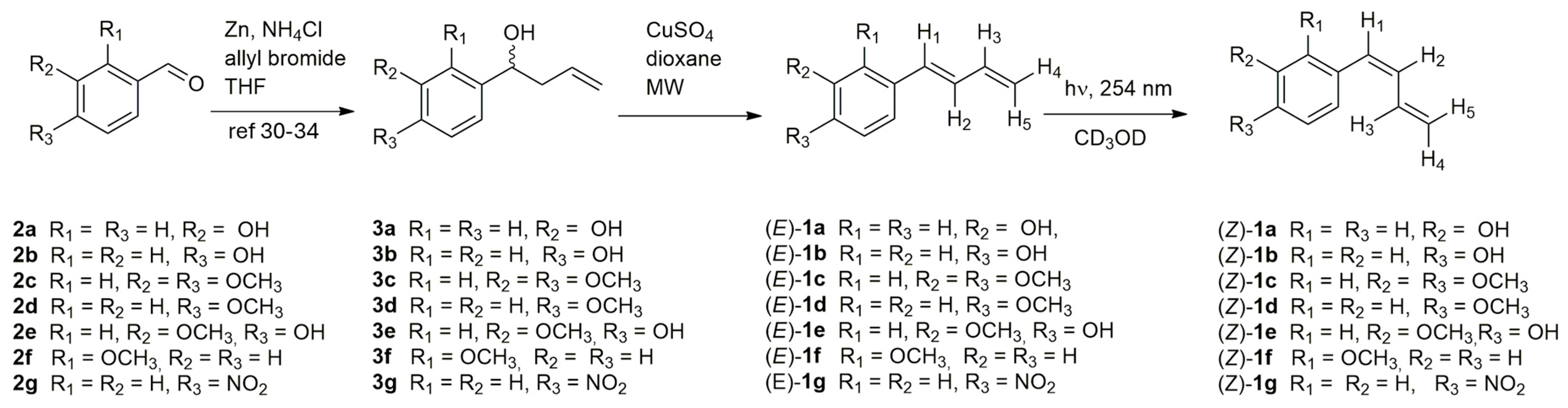

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of: (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene (E)-1a-g, (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene (Z)-1a-g and of their precursors 3a-g [30,31,32,33,34].

(E)-3-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)phenol. (E)-1a: 40%; oil; 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 5.03 (dd, J = 1.5, 10.7 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.21 (dd, J = 1.5 Hz, 17 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.39 (m, H3, 1H), 6.40 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.56 (dd, J = 2.5, 8 Hz, Ar, 1H), 6.67 (dd, J = 10.3, 15.8 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.75 (t, J = 1.7 Hz, Ar, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar, 1H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar, 1H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 112.39, 114.41, 116.29, 117.82, 129.21, 129.25, 132.69, 137.20, 138.56 157.27; Anal. Calcd for C10H10O: C, 82.16; H, 6.89. Found: C, 82.13; H, 6.84

(E)-4-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)phenol. (E)-1b: 66%; mp = 100–101 °C; 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 5.05 (dd, J = 1.4, 10 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.25 (dd, J = 1.4 Hz, 17.6 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.51 (m, H3, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.68 (dd, J = 10.6, 15.4 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.77 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H), 7.28 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 114.65, 115.06, 126.6′, 127.38, 128.82, 132.52, 137.53, 156.99; Anal. Calcd for C10H10O: C, 82.16; H, 6.89. Found: C, 82.12; H, 6.85.

(E)-4-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-1,2-dimethoxybenzene. (E)-1c: 85%; mp = 37–38 °C (Lit. [35] 36.5 °C); 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 3.67 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 3.84 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.11 (dd, J = 1.6, 12.0, H4, 1H), 5.30 (dd, J = 1.6, 16.2, Hz, H5, 1H), 6.51 (m, H3, 1H) 6.53 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.74 (dd, J = 10.8, 15.6 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar3, 1H), 6.98 (dd, J = 2.4, 8.4, HAr2, Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, Ar1, 1H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 55.03, 55.05, 109.11, 111.52, 115.36, 119.70, 127.63, 130.52, 132.41, 137.36, 149.05, 149.10; Anal. Calcd. for C12H14O2: C, 75.76; H, 7.42. Found: C, 75.80; H, 7.41.

(E)-1-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-4-methoxybenzene. (E)-1d: 81.5%; mp = 40–42 °C; 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 3.77 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.07 (dd, J = 2, 10 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.23 (dd, J = 2 Hz, 16.6 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.45 (m, H3, 1H), 6.51 (dt, J = 10.3, 16.2 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.65 (dd, J = 10.3, 16.2 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.87 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H), 7.35 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 58.26, 117.63, 119.04, 131.23, 131.25, 133.84, 136.15, 141.37, 163.41; Anal. Calcd for C11H12O: C, 82.46; H, 7.55. Found: C, 82.50; H, 7.59.

(E)-4-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-2-methoxyphenol. (E)-1e: 65%; mp = 66–67 °C; 1H-NMR: 3.89 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.07 (dd, J = 1.8, 10.8 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.27 (dd, J = 1.8 Hz, 16.9 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.50 (m, H3, 1H), 6.51 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.65 (dd, J = 10.3, 16.1 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 8 Hz, Ar, 1H), 6.88 (dd, J = 2, 8, Hz, Ar, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 2 Hz, Ar, 1H), 13C-NMR: 56.39, 110.42, 116.23, 116.35, 121.22, 128.30, 130.85, 134.20, 138.89, 147.72, 149.17; Anal. Calcd for C11H12O2: C, 74.98; H, 6.86. Found: C, 74.90; H, 6.85.

(E)-1-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-2-methoxybenzene. (E)-1f: 78%; oil; 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 3.84 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.12 (dd, J = 1.8, 9.6 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.30 (dd, J = 1.8, 16.8 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.53 (ddd, J = 10.2, 16.8, 16.8 Hz, H3, 1H) 6.84 (dd, J = 10.8, 16.2 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.91 (dt, J = 1.2, 7.8 Hz, Ar, 1H), 6.96 (dd, J = 1.2, 8.4 Hz Ar, 1H), 7.22 (dt, J = 1.8, 8.4 Hz, Ar, 1H), 7.49 (dd, J = 1.8, 7.8 Hz, Ar, 1H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 54.55, 110.69, 115.66, 120.29, 125.81, 125.97, 127.45, 128.43, 129.61, 137.92, 156.93; Anal. Calcd. for C11H12O: C, 82.46; H, 7.55. Found: C, 82.50; H, 7.51.

(E)-1-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-4-nitrobenzene. (E)-1g: 55%; mp = 77–78 °C (Lit. [36] 77.6–78.2 °C); 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 5.01 (dd, J = 1.8, 10.2 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.20 (dd, J = 1.8, 16.8, Hz, H5, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.48 (m, H3, 1H), 6.62 (dd, J = 10.8, 16.2, 10.8 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.76 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H), 7.21 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 113.89, 114.90, 114.91, 125.38, 127.15, 133.01, 137.74, 147.44; Anal. Calcd. for C10H9NO2: C, 68.56; H, 5.18. Found: C, 68.52; H, 5.21.

2.3. General Procedure for Synthesis of (Z)-1a-g

An NMR tube containing a 50 mM solution of compounds (E)-1a-g in deuterated methanol was exposed to two Spectroline UV lamps operating at 254 nm with an intensity of 390 μW/cm2. After 0.5, 3, 6, 12 and 24 hs of irradiation, 1H-NMR spectra were recorded. The ratios of the (E) and (Z) isomers were determined by integrating the olefinic protons H4 and H5 of compounds (E)-1a-g and (Z)-1a-g. Compounds (Z)-1a-g were purified by flash chromatography using a 1:2 mixture of ethyl acetate/petroleum ether as an eluent.

(Z)-3-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)phenol. (Z)-1a: 30%; oil: 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 5.21 (dd, J = 1.2, 10.0 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.39 (dd, J = 1.2, 17.2 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.24 (t, J = 11.2 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.36 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.69 (dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, Ar, 1H), 6.74 (m, Ar, 2H), 6.88 (m, H3, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar, 1H); 13C-NMR δ ppm: 55.97, 112.11, 117.06, 121.71, 127.38, 128.84, 129.84, 131.12, 139.34, 158.33 Anal. Calcd. for C10H10O: C, 82.16; H, 6.89. Found: C, 82.29; H, 6.79.

(Z)-4-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)phenol. (Z)-1b: 55%; oil: 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 5.18 (dd, J = 1.2, 10.4 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.37 (dd, J = 1.2, 16.8 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.14 (t, J = 11.2 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.36 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.78 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H), 6.90 (m, H3, 1H), 7.16 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H); 13C-NMR δ ppm: 114.67, 117.35, 128.31, 129.90, 129.94, 143.00, 146.78, 149.93; Anal. Calcd. for C10H10O: C, 82.16; H, 6.89. Found: C, 82.23; H, 6.81.

(Z)-4-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-1,2-dimethoxybenzene. (Z)-1c: 52%; oil: 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 3.84 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 3.89 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.21 (dd, J = 1.8, 17.5, H5, 1H), 5.36 (dd, J = 1.8, 10.2 Hz, H4, 1H), 6.21 (t, J = 11.4 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.40 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.89-6.97 (series of m, 4H); 13C-NMR δ ppm: 55.04, 55.07, 111.29, 112.52, 118.19, 121.70, 129.17, 129.78, 130.70, 133.28, 143.45, 143.90; Anal. Calcd. for C12H14O2: C, 75.76; H, 7.42. Found: C, 75.79; H, 7.51.

(Z)-1-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-4-methoxybenzene. (Z)-1d: 51%; oil; 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 3.80 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.19 (dd, J = 1.2, 10.0 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.34 (dd, J = 1.2, 17.2, Hz, H5, 1H), 6.18 (t, J = 11.6 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.39 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.90 (m, H3, 1H), 6.91 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H), 7.26 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H, Ar, 2H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 61.60, 114.65, 119.16, 130.27, 131.02, 131.28, 131.33, 134.61, 173.12; Anal. Calcd. for C11H12O: C, 82.46; H, 7.55. Found: C, 82.39; H, 7.61.

(Z)-4-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-2-methoxyphenol. (Z)-1e: 46%; oil; 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 3.74 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.07 (dd, J = 1.2, 10.4 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.21 (dd, J = 1.2, 16.8 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.24 (t, J = 11.2 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.40 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.64-6.88 (series of m, 4H, H3+Ar1+Ar2+Ar3); 13C-NMR δ ppm: 54.99, 112.27, 114.64, 117.59, 121.89, 128.54, 129.35, 130.10, 133.17, 145.45, 147.66; Anal. Calcd. for C11H12O2: C, 75.76; H, 7.42. Found: C, 75.83; H, 7.31.

(Z)-1-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-2-methoxybenzene. (Z)-1f: 40%; oil; 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 3.83 (s, -OCH3, 3H), 5.18 (dd, J = 2.0, 10.4 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.36 (dd, J = 2.0, 17.2 Hz, H5, 1H), 6.16 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.40 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.76 (m, H3, 1H), 6.90–7.3, series of m, Ar, 4H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 54.49, 110.34, 117.66, 119.62, 125.93, 126.05, 128.46, 129.85, 130.08, 133.45, 157.20; Anal. Calcd. for C11H12O: C, 82.46; H, 7.55. Found: C, 82.49; H, 7.58.

(Z)-1-(buta-1,3-dien-1-yl)-4-nitrobenzene. (Z)-1g: 60%; mp = 75–76 °C (Lit. [31] 74 °C); 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ ppm: 5.14 (dd, J = 1.8, 10.2 Hz, H4, 1H), 5.29 (dd, J = 1.8, 17.4, Hz, H5, 1H), 6.09 (t, J = 11.4 Hz, H2, 1H), 6.32 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, H1, 1H), 6.91 (m, H3, 1H), 6.72 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H), 7.11 (m, AA′BB′, Ar, 2H); 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ ppm: 116.08, 118.15, 128.69, 128.79, 131.15, 131.74, 135.04, 148.19; Anal. Calcd. for C10H9NO2: C, 68.56; H, 5.18. Found: C, 68.59; H, 5.15.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthetic Aspects

The synthesis of 4-aryl-1-buten-4-ol derivatives 3a [30], 3b [31], 3c [32], 3d [33], 3e [33], 3f [31] and 3g [34] from the corresponding commercial aldehydes 2a-g by Barbier coupling reaction has been previously reported in the literature. We carried out the dehydration of intermediates 3a-g under microwave irradiation in the presence of anhydrous CuSO4 and 1,4-dioxane, affording the corresponding dienes (E)-1a-g (Scheme 1). To the best of our knowledge, these are the first reported examples of microwave-assisted dehydration of 4-aryl-1-buten-4-ol, highlighting the potential of this approach for the rapid and selective synthesis of conjugated (E) dienes.

The use of microwave-assisted heating in this context represents a significant advancement, enabling rapid and clean transformation under relatively mild conditions. MW irradiation has demonstrated considerable potential in promoting alcohol dehydration reactions to produce carbon-carbon double bonds, often under gentler conditions and with shorter reaction times compared to traditional thermal methods. These dehydration reactions are significant due to their utility in the synthesis of alkenes and conjugated systems. In particular, the selective formation of (E)-configured double bonds during the reaction is crucial, as this stereocontrol strongly influences the spatial arrangement and overall geometry of the resulting conjugated frameworks. The preference for the (E) isomer is typically attributed to its greater thermodynamic stability and reduced steric hindrance relative to the (Z) isomer. The (E) to (Z) photoisomerizations of compounds (E)-1a-g were carried out directly in NMR tubes using deuterated solvents, allowing for real-time monitoring of the reaction progress without the need for workup procedures. The ratio of geometric isomers was determined at regular time intervals by analyzing the NMR spectra.

3.2. UV Absorption Studies

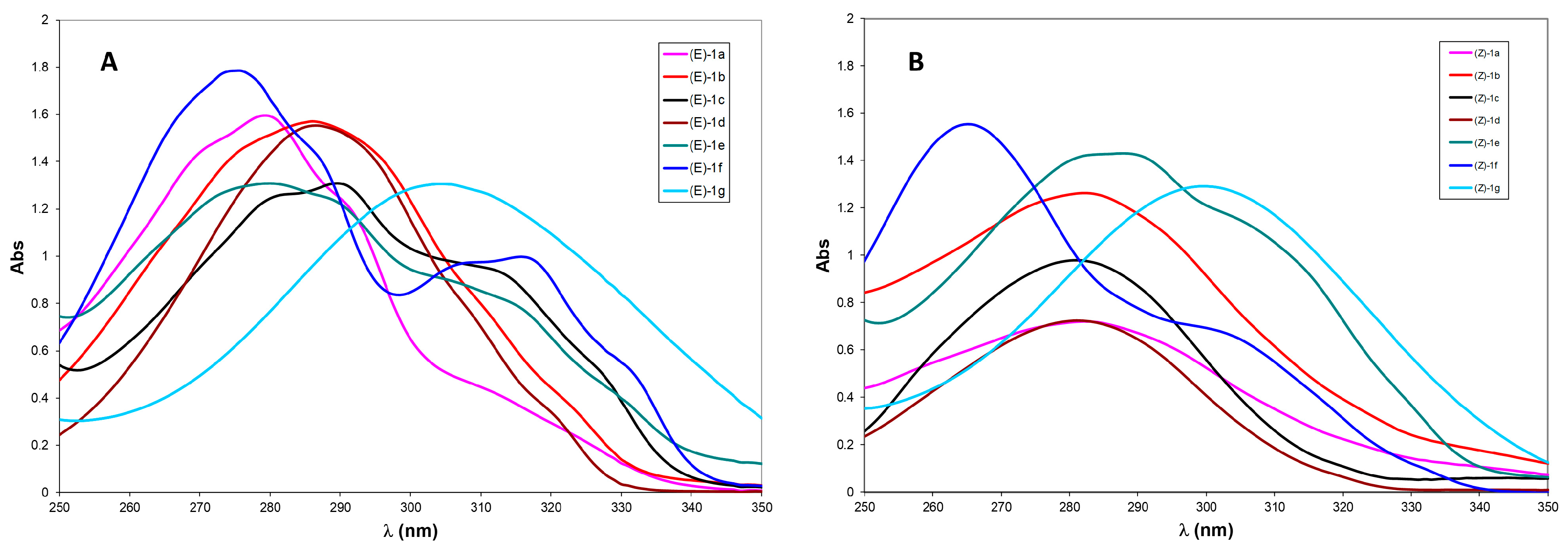

To gain insight into the different reactivities of aryl-substituted dienes 1a-g under visible-light irradiation, the UV–visible absorption spectra of all (E) isomers and their corresponding (Z) photoisomerized products were recorded in CD3OD at 10 μM (Figure 2A,B). The (Z)-configured compounds (Figure 2B) show a largely homogeneous absorption profile for para-substituted derivatives. In particular, (Z)-1b-e, bearing electron-donating groups at the para position, exhibit closely clustered absorption maxima around λ_max ≈ 285 nm, consistent with π → π* transitions of the conjugated aryl–diene system. Compound (Z)-1a, despite a similar absorption range, is formed with lower efficiency (30% yield from the corresponding (E) isomer), highlighting the importance of substituent positioning on the excited-state dynamics.

Figure 2.

UV spectra of: (A) compounds (E)-1a-g. (B) compounds (Z)-1a-g.

Distinct behavior is observed for (Z)-1f and (Z)-1g. The nitro-substituted (Z)-1g displays a bathochromic shift to ~300 nm, attributed to a push–pull effect and enhanced charge-transfer character, whereas the ortho-methoxy derivative (Z)-1f shows a hypsochromic shift (λ_max ≈ 265 nm), likely due to steric distortion and reduced conjugation.

The UV spectra of the (E) isomers closely parallel those of the corresponding (Z) compounds (Figure 2A). Isomers (E)-1a-e display absorption maxima in a narrow range (λ_max = 288–289 nm), approximately 7 nm red-shifted relative to the (Z) series. Similarly, (E)-1f and (E)-1g show red-shifted maxima at 275 nm and 304 nm, respectively, compared to their (Z) counterparts. These results indicate that diene geometry subtly modulates conjugation and electronic transition energies across the series

Taken together, these spectroscopic trends underscore how subtle changes in substituent electronics and substitution patterns can have a profound impact on the absorption properties of aryl-substituted 1,3-dienes. These differences in light absorption behavior are expected to directly influence their photochemical reactivity under visible-light irradiation, providing a rational basis for the experimentally observed variations in reaction efficiency and selectivity across the series.

3.3. Photoisomerization and NMR Spectroscopy Investigations

Standard Class B glass NMR tubes with a thin wall of 0.43 mm were used for the photochemical experiments. While standard glass strongly absorbs at 254 nm, the reaction does not depend solely on this wavelength. The lamp employed in our experimental setup emits a broader spectrum, including wavelengths above 300 nm, which are efficiently transmitted through the glass and are adequate to drive the observed photochemical transformation.

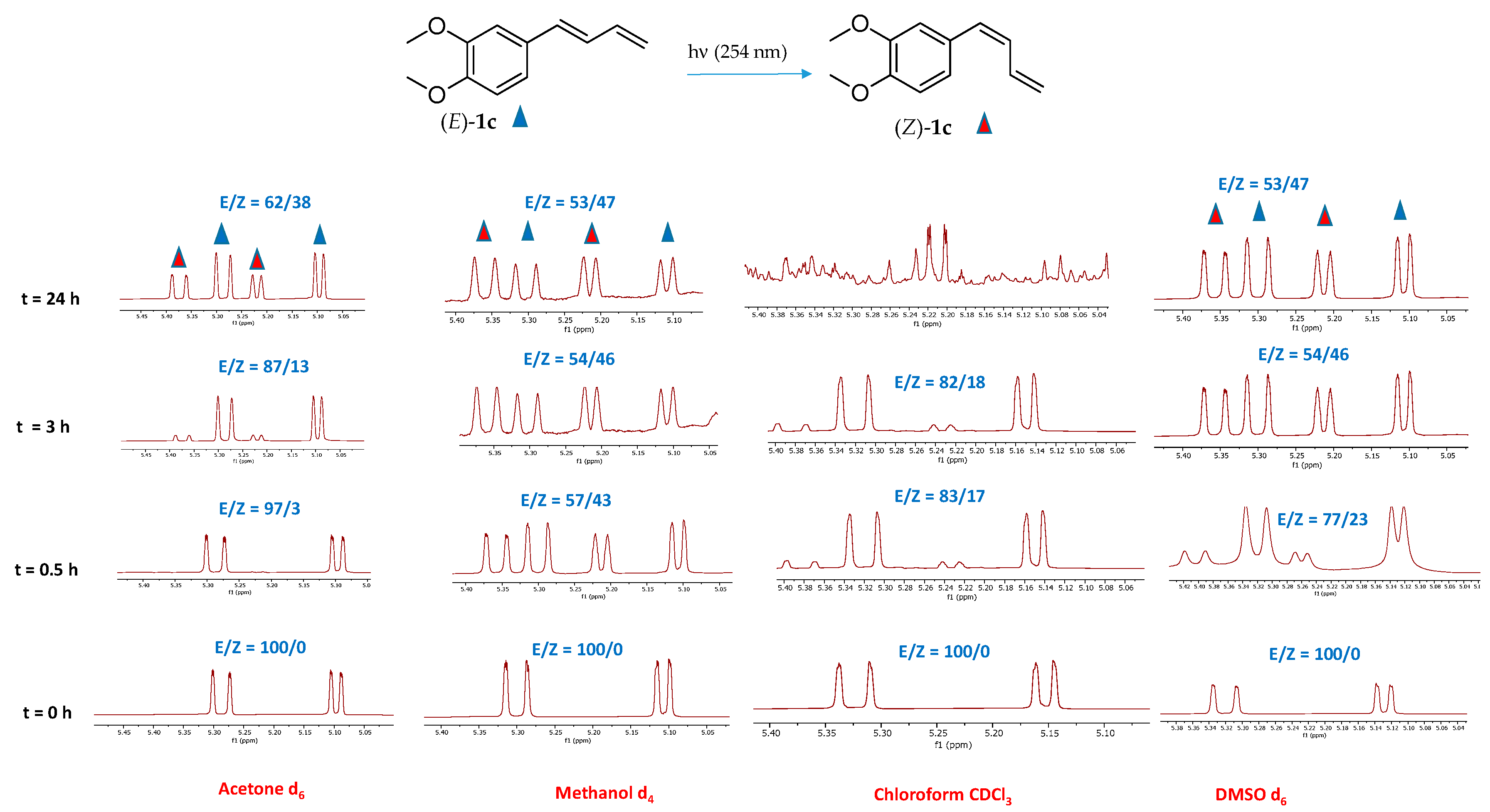

Compound (E)-1c, the major constituent isolated from the rhizomes of Zingiber cassumunar and known for its notable biological activities [1], was selected as a representative substrate to evaluate the influence of the solvent environment on isomerization efficiency. The impact of different deuterated solvents on the efficiency of the (E) to (Z) photoisomerization process was initially explored.

Solvent effects can influence excited-state lifetimes, nonradiative decay processes, and the stabilization of charge-separated or polarized excited states, ultimately impacting photoisomerization efficiency [37]. Among the various deuterated solvents tested, methanol (CD3OD) and dimethyl sulfoxide (CD3S(O)CD3) showed the highest photoisomerization efficiency (Figure 3). After 24 h of UV irradiation at 254 nm, about 47% of the (E)-1c isomer was converted to the corresponding (Z)-1c isomer in both solvents. Notably, stability studies confirmed that the isomeric ratio remained unchanged with prolonged irradiation, indicating good photostability of the mix under the tested conditions. In contrast, a lower conversion rate of approximately 38% was observed when the reaction occurred in deuterated acetone (CD3C(O)CD3). Additionally, 1H-NMR analysis of irradiated (E)-1c in deuterated chloroform revealed the formation of several unidentified side products after 12 h, suggesting reduced stability in this medium. The instability of chlorinated solvents at wavelength < 300 nm is, in fact, well documented in the literature [38]. This finding aligns with the results of Seaho et al. [1], which examined the long-term stability of compound (E)-1c in various deuterated solvents and showed significant degradation in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) after 24 h while it remained completely stable in deuterated methanol (CD3OD) over the same period.

Figure 3.

1H-NMR spectra (terminal olefinic protons region) of compounds (E)-1c and (Z)-1c in deuterated acetone, methanol, chloroform and DMSO recorded after irradiating (E)-1c at 254 nm for t = 0.5, 3 and 24 h. The red triangles indicate the olefinic signals of the (Z)-1c isomer, while the blue triangles represent the olefinic signals of the (E)-1c isomer. Integrations showing the (E)/(Z) ratio at different times are reported.

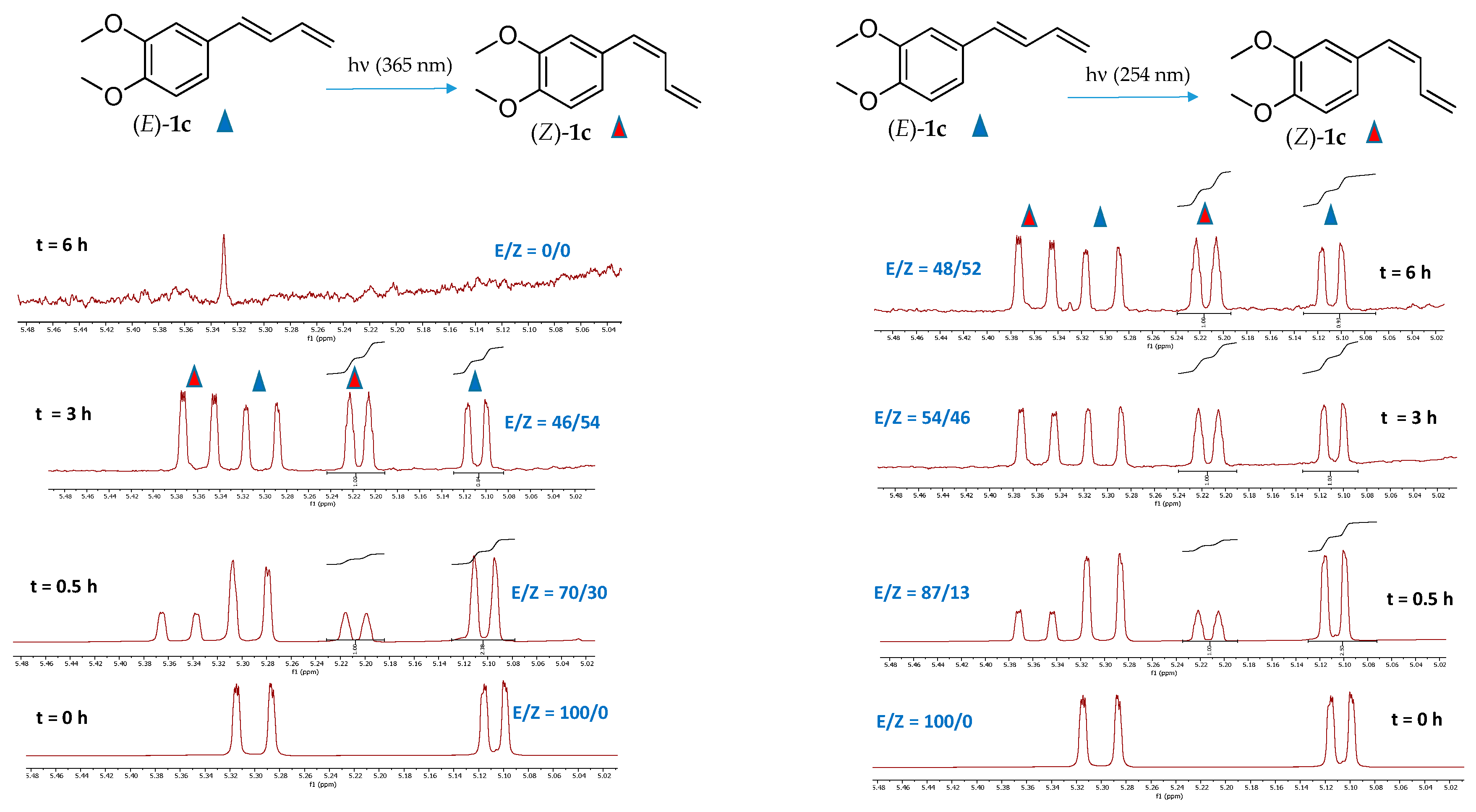

Based on these observations, methanol-d4 (CD3OD) was selected as the solvent for all subsequent photoisomerization experiments, offering an ideal balance between conversion efficiency and chemical stability. The selection of ultraviolet radiation at 254 nm was based on preliminary screening experiments examining the photoisomerization behavior of (E)-1c comparing the effects of two irradiation wavelengths: long-wave UV (365 nm) and short-wave UV (254 nm) (Figure 4). The absorption spectrum from 250 to 350 nm of the compound (E)-1c is shown together with that of the other compounds in Figure 2.

Figure 4.

1H-NMR spectra (terminal olefinic protons region) of compounds (E)-1c and (Z)-1c in deuterated methanol, recorded after irradiating (E)-1c at 254 and 365 nm for t = 0.5, 3 and 6 h. The red triangles indicate the olefinic signals of the isomer (Z)-1c, while the blue triangles represent the olefinic signals of the isomer (E)-1c. Wavy lines show the (E)/(Z) integrations ratio at different time points.

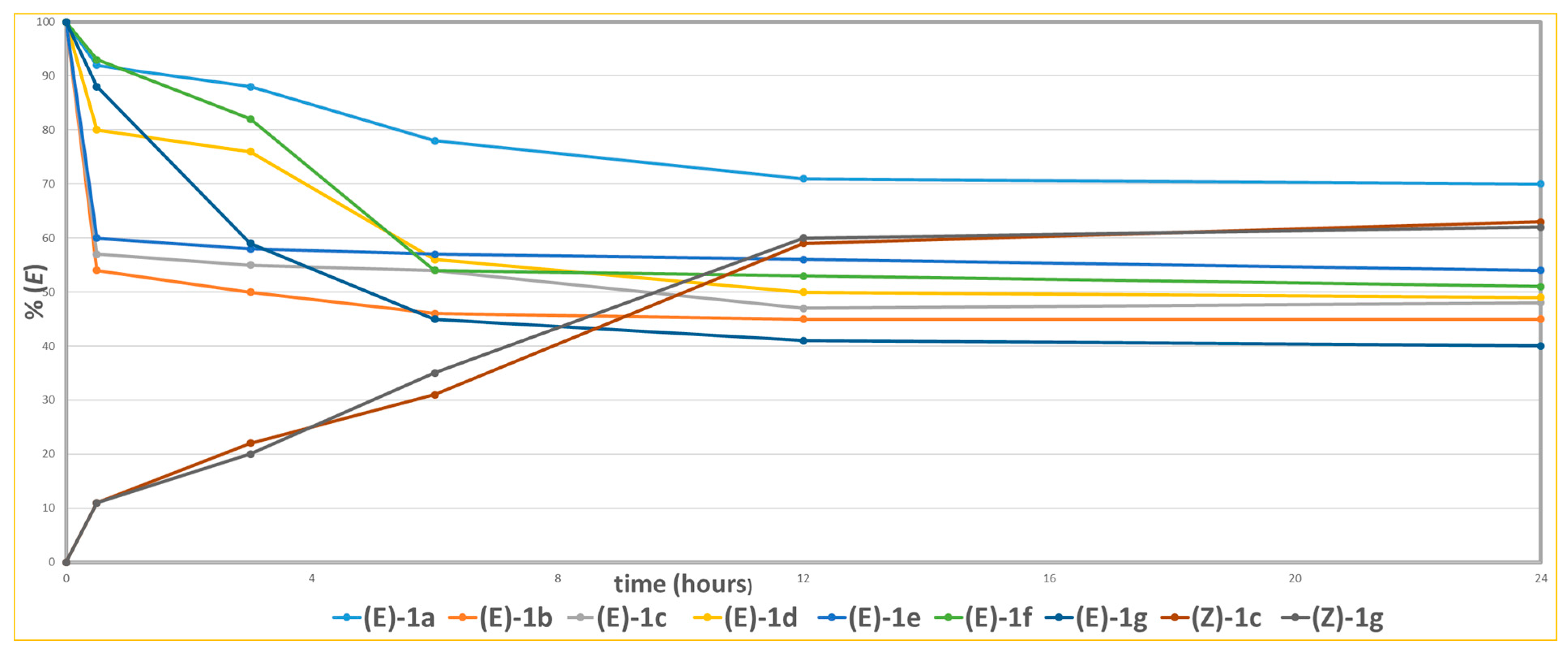

1H-NMR analysis of the terminal diagnostic olefinic region of (E)-1c in deuterated methanol, after irradiation for 0.5, 3 and 6 h, showed similar photoisomerization profiles under both wavelengths. Although long-wave UV (365 nm) caused a slightly faster isomerization rate, it also resulted in complete degradation of the compound after 6 h of exposure (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the (E) to (Z) photoisomerization rates of compounds (E)-1a-g and the reverse (Z) to (E) conversion of two representative compounds (Z)-1c and (Z)-1g after irradiation at 254 nm in deuterated methanol. Analysis of the conversion profiles shows that all compounds reach a photostationary state with about 50% conversion within 12 h of continuous irradiation. Notably, the highest (E) to (Z) isomerization efficiency is observed for compound (E)-1g (60%), which features a strongly electron-withdrawing nitro (NO2) group in the para position of the aryl ring relative to the diene chain. This improved (E) to (Z) conversion likely results from the electron-deficient nature of the aryl ring, which probably stabilizes the excited state and makes geometric rearrangement easier by lowering the energy barrier for isomerization.

Figure 5.

(E) to (Z) conversion rate of compounds (E)-1a-g and (Z) to (E) conversion rate of compounds (Z)-1c and (Z)-1g upon irradiation at 254 nm in deuterated methanol.

The presence of a para-nitro substituent can also help delocalize the π-system, boosting the compound’s absorption efficiency at the irradiation wavelength and thus increasing overall photoreactivity. The conversion of (Z)-1c and (Z)-1g to their (E)-1c and (E)-1g isomers through retro-photoisomerization in the same solvent reached photostationary states after 24 h, with stabilization around 63% and 62%, respectively. This suggests that, under these conditions, the thermodynamically more stable isomer is predominant. To verify the formation of the photostationary equilibrium and confirm the system’s stability, kinetic monitoring was extended to 36 h. No major changes in isomer distribution were observed after 24 h, reinforcing that the system had achieved its photostationary state by then.

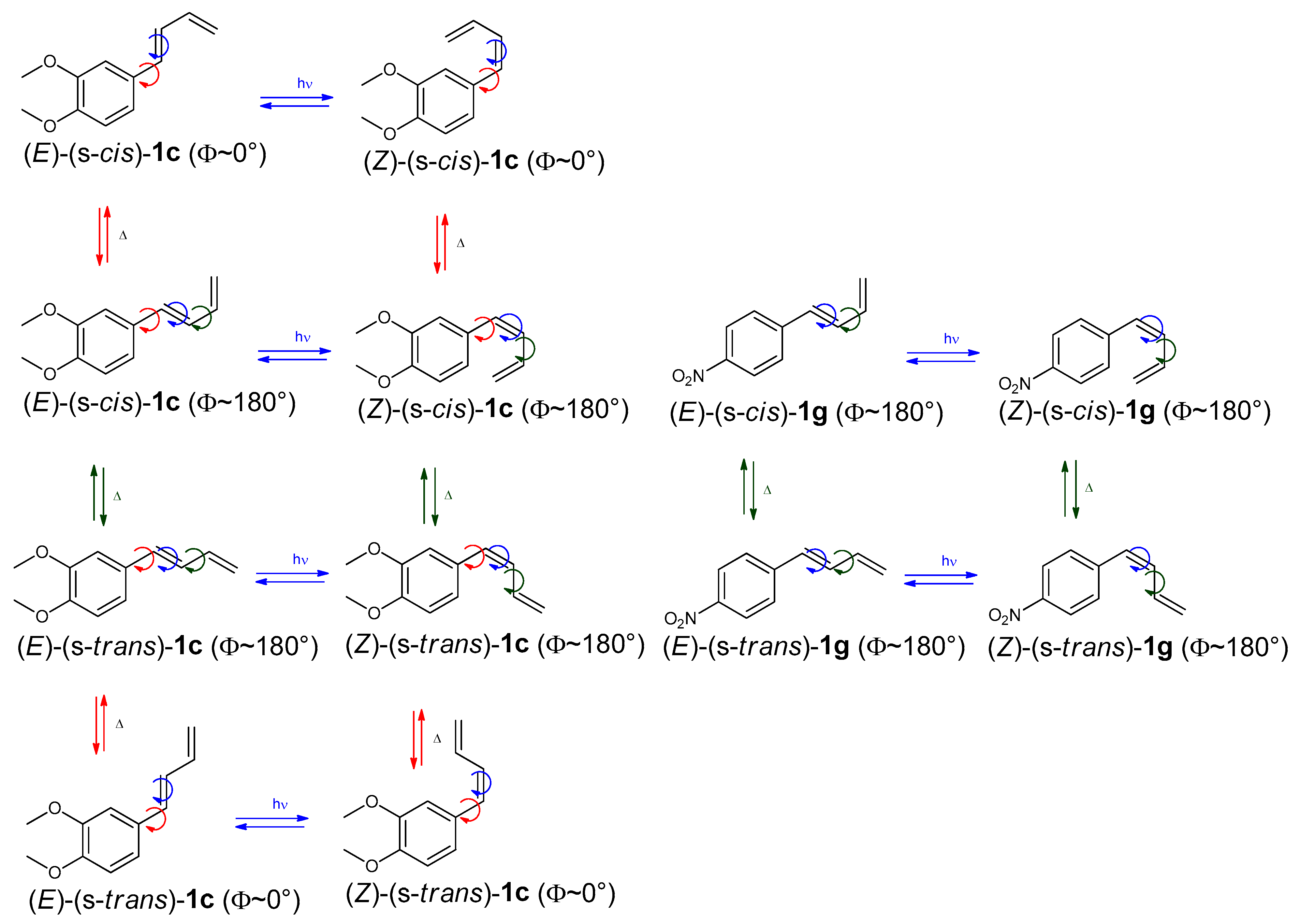

An interesting aspect of the photochemistry of 1-aryl-1,3-butadienes is their ability to undergo transformations that may involve changes in both the geometry of the double bond conjugated to the aryl group and the spatial arrangement of the terminal double bond. (E)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene derivatives can theoretically adopt either an s-cis or s-trans conformation around the central C–C single bond of the diene system, as well as generate various conformational rotamers through rotation about the C–C bond linking the aryl ring to the 1,3-butadiene segment. To explore the stereochemical insights of these compounds in detail, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was employed as a primary analytical method, to elucidate both the geometric isomerism and conformational preferences of the synthesized dienes (E)-1a-g and (Z)-1a-g. Two distinct pathways, photochemical and thermal, can account for the configurational and conformational isomerization of compounds 1a-g.

Compounds (E)-1c and (E)-1g were selected as representative substrates of aryl dienes with electron-donating group (-OCH3) and an electron-withdrawing group (-NO2), respectively. The electronic nature of substituents on the aryl ring plays a crucial role in determining the synthesis, stability, and reactivity of 1-aryl-1,3-butadienes.

In Scheme 2 the interconversion pathways between the isomeric forms of diene 1c and diene 1g are illustrated. These systems were chosen as representative aryl-diene frameworks bearing, respectively, a 3,4-disubstitued aromatic ring (1c) and a 4-substitued aromatic ring (1g). The comparison between these model compounds underscores the role of aromatic symmetry in governing interconversion dynamics and in determining the theoretical number of accessible isomeric species. Photochemical transformations (hν) are shown with blue arrows, whereas thermally induced processes (Δ) are represented by red and green arrows. For diene 1c, these mechanisms lead to four possible isomeric forms: (E)-(s-cis)-1c, (Z)-(s-cis)-1c, (Z)-(s-trans)-1c, and (E)-(s-trans)-1c. In each isomer, the dihedral angle (Φ) between the aryl and butadiene planes is approximately 180°. However, they may also adopt conformers with a 0° dihedral angle (Φ), arising from rotation about the single bond linking the aryl group to the butadiene chain. As a result, the total number of theoretically possible isomers for diene 1c increases to eight. For diene 1g, the inherent symmetry of the aromatic ring reduces the number of unique isomers by half compared to the non-symmetric case. Thanks to this symmetry, some geometrical and conformational arrangements become equivalent, leaving only four distinct options: (E)-(s-trans)-1g, (E)-(s-cis)-1g, (Z)-(s-trans)-1g, and (Z)-(s-cis)-1g. This behaves differently from diene 1c, where the lack of ring symmetry leads to twice as many distinct isomeric forms. The isomeric structures are shown in an idealized planar arrangement (Φ: 0° or 180°), which does not correspond to the actual dihedral angles of the optimized geometries. These simplified representations are intended for illustration only and may omit subtle but important torsional deviations that affect conjugation and overall molecular stability. A more accurate description of the conformational landscape can be found in the in silico calculated dihedral angles and structural parameters presented in Section 3.4.

Scheme 2.

Configurational and conformational isomers of compounds 1c and 1g. Red and green arrows indicate thermal (∆) isomerization, while blue arrows denote photochemical (hν) isomerization. Red circles signify rotation around the single bond between the phenyl ring and the butadiene group, blue circles illustrate (E)-(Z) photoisomerization, and the green circle marks rotation around the C2–C3 single bond of the butadiene moiety.

The dehydration of compounds 3a-g proceeded with remarkable stereocontrol, affording the corresponding derivatives 1a-g exclusively as single (E)-(s-trans) isomers. The geometry of these products was confirmed by vicinal coupling constants, J(H1–H2), in the 1,3-butadiene moiety, which showed values characteristic of trans olefinic protons coupling (Table 1), aligning with the assigned (E) configuration. The conformational preferences of 1,3-butadiene systems can be understood through analysis of the vicinal coupling constant J(H2–H3), which is highly sensitive to the dihedral angle between neighboring vinylic protons and thus reflects the molecule’s overall structure. These systems usually adopt one of two main conformations: s-cis or s-trans. In the s-trans conformation, the 1,3-diene system is nearly planar, giving a larger vicinal J(H2–H3) in the range of 10–16 Hz, as described by the Karplus relationship [34]. Conversely, the s-cis conformation introduces a sharp dihedral angle reducing J(H2–H3) to 6–9 Hz. The vicinal coupling constant J(H2–H3) (10.2–10.8 Hz) observed in compounds (E)-1a-g indicate a predominant s-trans conformation with a nearly planar structure. Interestingly, the (Z)-1a-g compounds also showed a J(H2–H3) value around 11.4 Hz, suggesting an s-trans-like arrangement despite their (Z) configuration. However, in this case, the geometry is distorted from planarity, possibly due to steric interactions between substituents or intramolecular electronic effects, which favor the extended s-trans arrangement. Overall, these NMR results emphasize the (E) geometry of the 1,3-butadiene backbone under these substitution patterns and reaction conditions.

Table 1.

Vicinal and geminal coupling constants for compounds (E)-1a-g and (Z)-1a-g determined by 1H-NMR. Coupling constant values are reported in Hertz.

In Table 1 the coupling constants J(H1–H2), J(H2–H3), J(H3–H4), J(H3–H5), and J(H4–H5) measured for the full series of compounds (E) and (Z)-1a-g are summarized. The data show a clear consistency in the coupling values across the series, indicating similar geometrical and conformational features within the (E) and (Z) isomers. This aligns perfectly with the expected coupling constant range (10–16 Hz) for vicinal olefinic protons in a s-trans-like arrangement, implying a structural convergence where both isomeric series minimize torsional strain and enhance conjugation by adopting similar extended geometries.

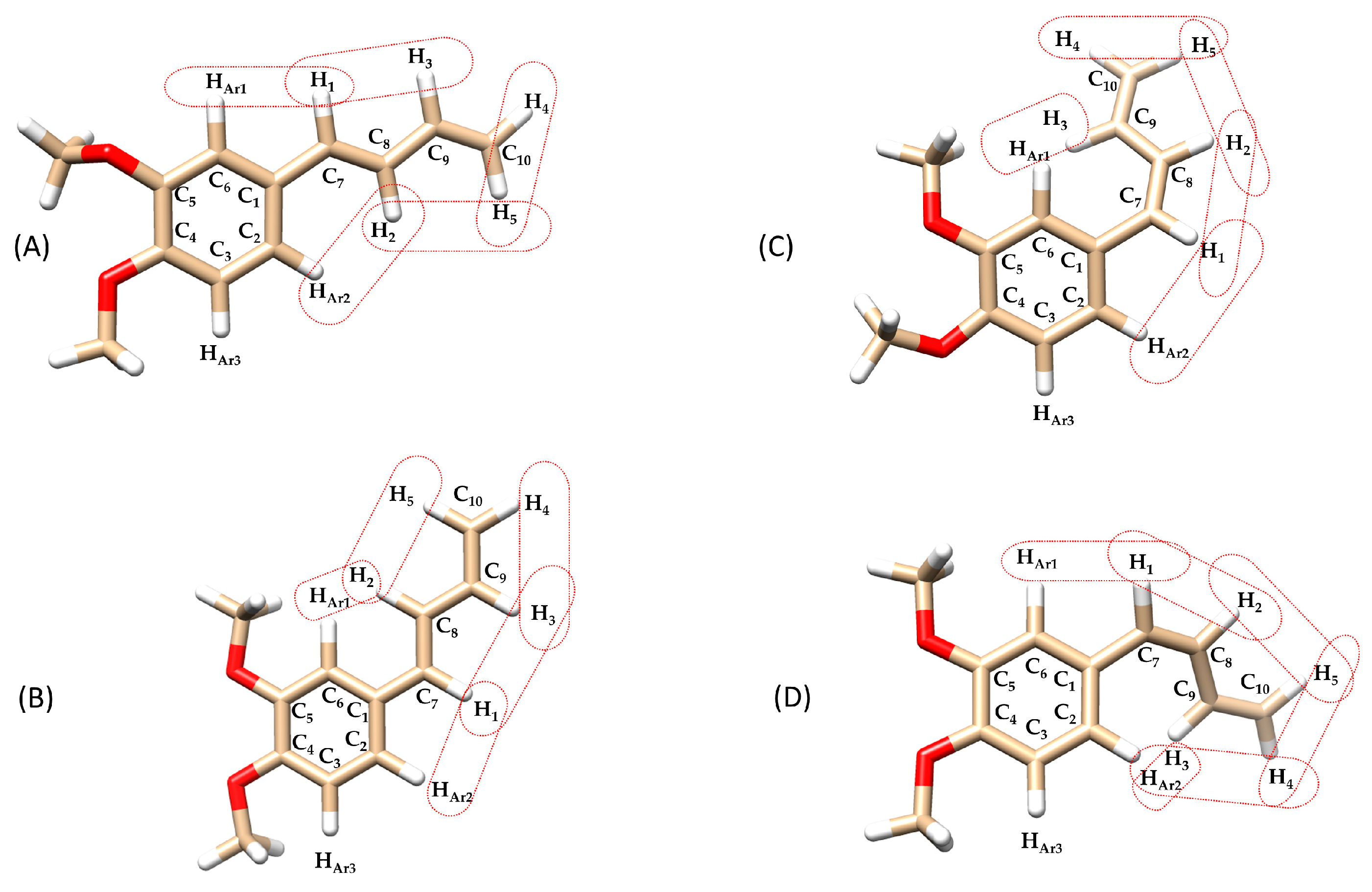

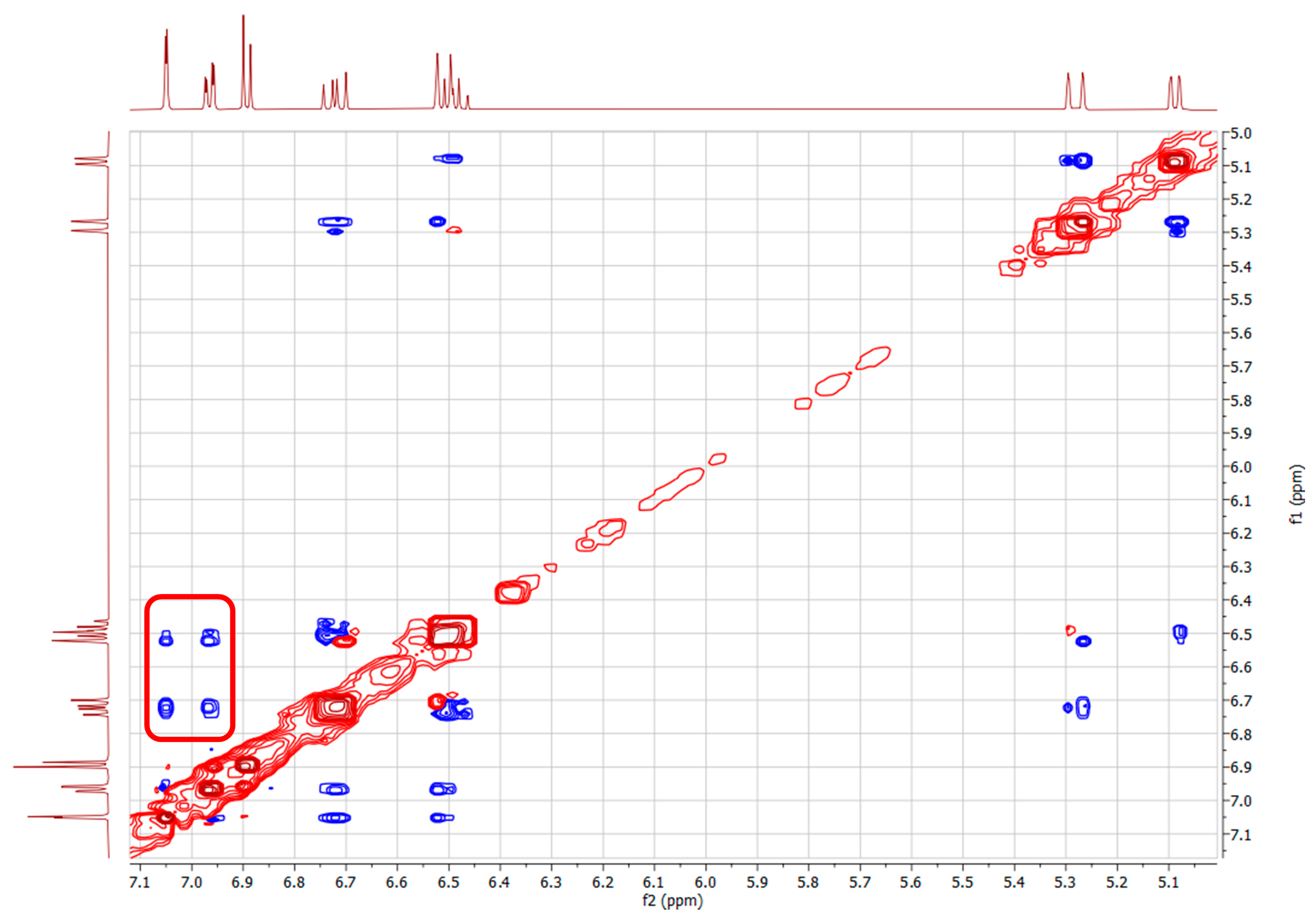

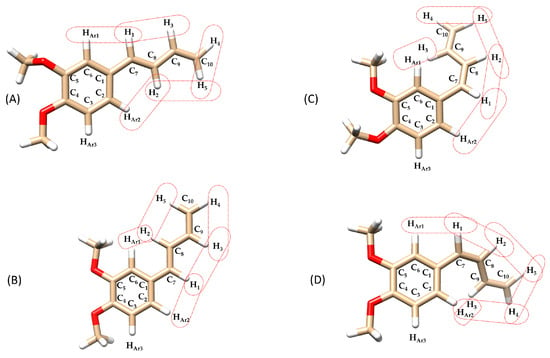

The structures of the isomeric compounds (E)-(s-trans)-1c and (Z)-(s-trans)-1c were further investigated using 2D NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser Effects) 1H-NMR experiments, which provided detailed insights into spatial interactions between neighboring protons. For (E)-(s-trans)-1c, reported in Figure 6 as two possible rotamers A and B with dihedral angles Φ1 = 169° and 4°, respectively, the NOESY spectrum (Figure 7) displayed distinct dipolar correlations between protons H1–H3, H2–H5, H1–HAr1, and H2–HAr2. These interactions confirm that the respective nuclei are in close spatial proximity, in agreement with the (s-trans) conformation of the 1,3-butadiene unit (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of the compounds isomers: (A) (E)-(s-trans)-1c (dihedral angle between aromatic ring and 1,3-butadiene chain (Φ1) = 169°), (B) (E)-(s-trans)-1c (Φ1 = 4°), (C) (Z)-(s-trans)-1c (Φ1 = 36°), (D) (Z)-(s-trans)-1c (Φ1 = 43°), highlighting dipolar interactions between olefinic-olefinic and olefinic-aromatic protons. Structures (A–D) have undergone in silico energy optimization (see Section 3.5. In silico studies).

Figure 7.

NOESY NMR (deuterated methanol) of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1c. The red box marks the observed spatial correlation between H1-HAr1, H2-HAr2, H1-HAr2 and H2-HAr1, indicating their proximity in space. Red and blue cross-peaks correspond to positive and negative NOE signals, respectively, reflecting through-space proton–proton interactions.

Furthermore, the NOESY spectrum of (E)-(s-trans)-1c (Figure 6) shows additional important dipolar interactions between protons H1–H3, H2–H5, H2–HAr1, and H1–HAr2 supporting a molecular shape consistent with the (E)-(s-trans)-1c isomer, where the aryl group and the butadienyl fragment can exist in two different rotamers with two planes rotated roughly 180° apart. Seeing NOE cross-peaks between distant proton pairs indicates a dynamic balance involving quick rotation around the single bond linking the aryl and butadienyl parts. This conformational change switches between two nearly flat rotamers with dihedral angles of 0° and 180°, showing a low energy barrier for rotation around this bond. The strength of the dipolar cross-relaxation suggests that interconversion of these conformers occurs on a timescale suitable for NOE averaging, supporting the idea of rapid conformational changes at the NMR timescale. These results indicate that the molecule does not maintain a fixed shape in solution but rather fluctuates between two preferred structures due to thermal motion, which is crucial for understanding its stereoelectronic properties and potential reactivity.

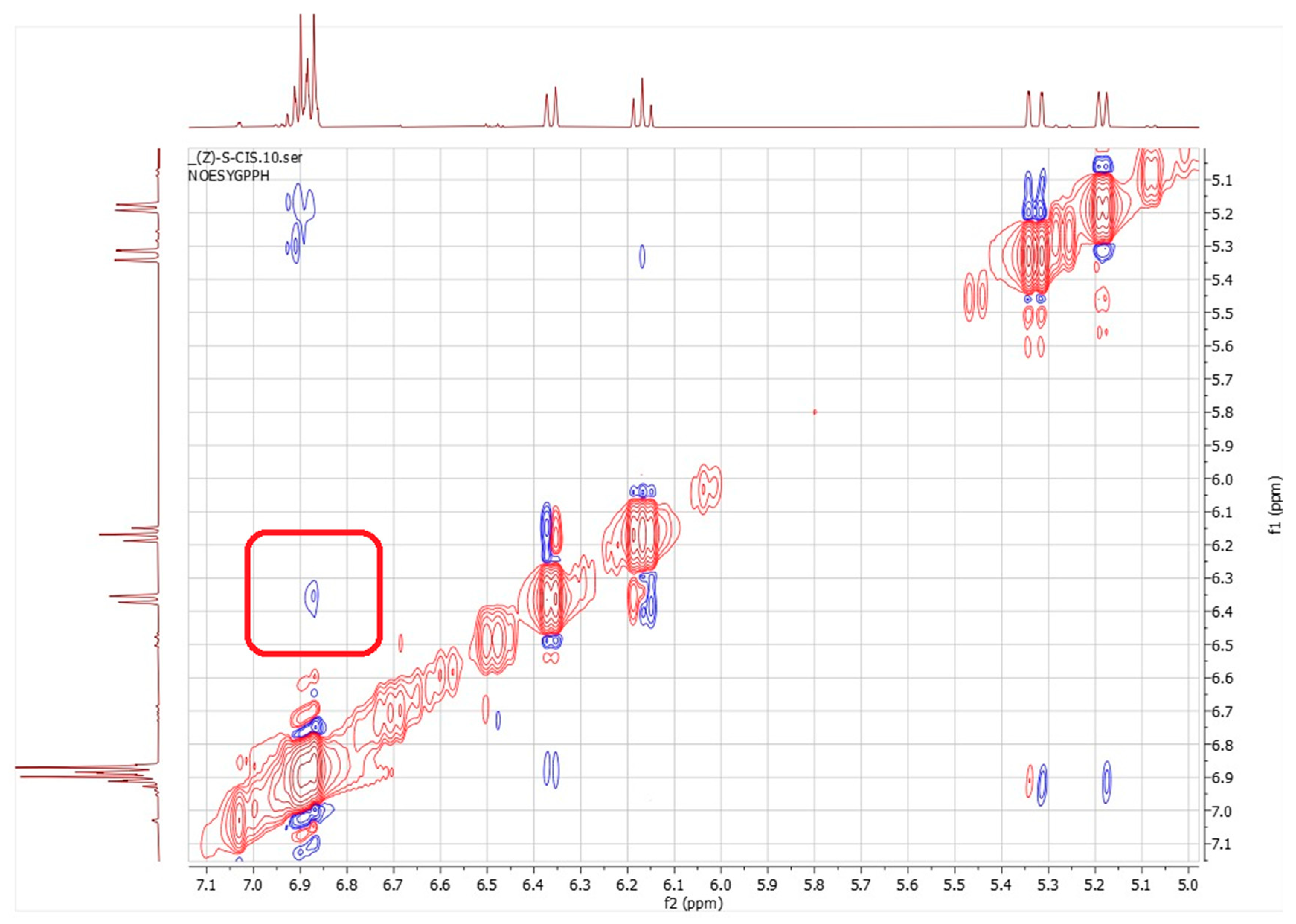

Regarding the rotamers of the (Z)-(s-trans)-1c isomer (Figure 6C,D) interpreting the NOESY spectrum was challenging due to significant signal overlap (Figure 8). Specifically, the resonances for the H3 proton overlapped with those of the aromatic protons HAr1 and HAr2, making it difficult to identify spatial interactions unambiguously. This spectral congestion limited the ability to confidently assign NOE correlations and hindered a detailed conformational analysis of the rotameric species under these conditions. The downfield shift in the H3 proton may result from a deviation from planarity in both rotamers of the (Z)-(s-trans)-1c structure. This distortion likely positions the H3 proton of the butadienic system partially within the aromatic ring’s anisotropic cone, causing a shielding effect and a chemical shift difference of about 0.4 ppm compared to the H3 proton in the (E)-(s-trans)-1c isomer. This behavior is consistently observed in the 1H-NMR spectra of all synthesized (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene derivatives 1a-g. In each case, the H3 proton shows a characteristic downfield shift relative to its (E)-isomer counterpart, likely due to similar distortions from planarity. However, the NOESY analysis revealed a spatial interaction between H1 and only one of the aromatic protons (either HAr1 or HAr2). This indicates a slightly distorted s-trans conformation, in which the molecular folding caused by the (Z) configuration brings these nuclei closer together. As a result, unlike its (E)-(s-trans) counterpart, this isomer does not seem to exhibit dynamic behavior.

Figure 8.

NOESY in deuterated methanol of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1c. The red box marks the observed spatial correlation between H1 and a single aromatic proton, either HAr1 or HAr2, indicating their close spatial proximity. Red and blue cross-peaks correspond to positive and negative NOE signals, respectively, reflecting through-space proton–proton interactions.

3.4. Thermal Stability of (Z) Isomers

To assess the configurational thermal stability of the pure compounds (Z)-(s-trans)-1a-g experiments were performed in the dark. Each compound was dissolved in deuterated methanol and heated at 25 °C and 65 °C for 100 h, respectively. The (Z)/(E) ratio was monitored using 1H-NMR spectroscopy. All compounds showed high thermal stability at 25 °C, maintaining 100% of their (Z) isomeric form after 100 h. At 65 °C, compounds (Z)-(s-trans) experienced only partial mono-retro isomerization to the (E) isomer (detected in trace amounts).

3.5. In Silico Studies

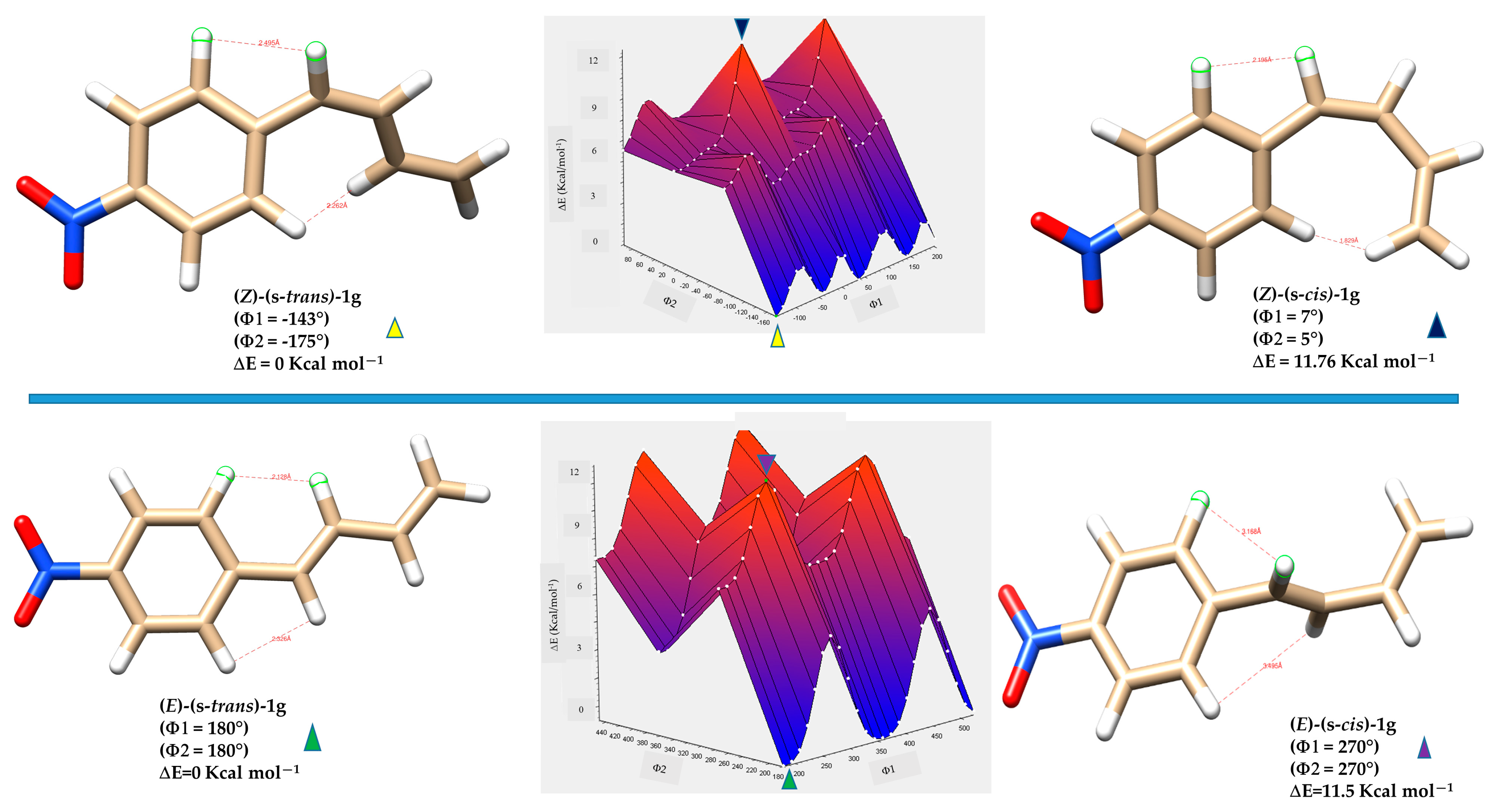

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provide a powerful computational approach for exploring the conformational behavior of molecules. By estimating the energy barriers (ΔE) associated with internal rotations and isomerization processes, DFT allows for the prediction of how readily different conformers interconvert. These energy barriers are critical in determining whether distinct conformers can be observed separately or appear as a time-averaged structure in spectroscopic techniques such as NMR. It is generally accepted that, in solution, conformational exchange processes can only be resolved by NMR spectroscopy at room temperature when the rotational barrier is sufficiently high; in practice, barriers of approximately 15 kcal·mol−1 or greater are typically required for two rotamers to appear as distinct species rather than as averaged signals [39]. By calculating the relative energies of (s-cis), (s-trans) and other rotameric forms, DFT helps identify the dominant isomer in solution, which generally corresponds to the most thermodynamically favoured structure and matches well with the observed NMR data [40]. To elucidate the conformational energy profile in greater detail of the (E)-1a-g and (Z)-1a-g series, DFT calculations were performed to evaluate the relative stabilities and optimized geometries of the s-trans and s-cis conformers, as well as the relevant rotamers associated with each geometric isomer. Representative compounds 1c and 1g were selected as model systems for this analysis. To analyze energy variations, a relaxed scan was performed in Gaussian 16, involving the simultaneous rotation of two key dihedral angles: Φ1, between the aryl group and the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2, and Φ2, defined by the torsion between the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2 and H3-C9-C10-H5. (see Figure 5). The dihedral angle Φ1 was varied in 15° increments, while the alkyl chain dihedral angle Φ2 was varied in 90° increments, each covering a full 360° rotation. This protocol yielded 96 distinct geometry optimizations for each compound (E)-1c, (Z)-1c, (E)-1g and (Z)-1g (Tables S1–S4). This computational approach allowed the creation of a detailed three-dimensional energy surface, providing useful theoretical insights into the conformational behavior of the studied dienes. Specifically, the 3D energy landscape maps out the energetic preferences associated with different torsional arrangements, enabling the identification of both stable and unstable conformers. This analysis is crucial for understanding the conformational isomerism of (E)-1a-g and (Z)-1a-g dienes, which can adopt multiple spatial arrangements due to the flexibility of their π-conjugated systems. The outcomes of the computational analysis provide strong support for the isomeric assignments based on NMR spectroscopy.

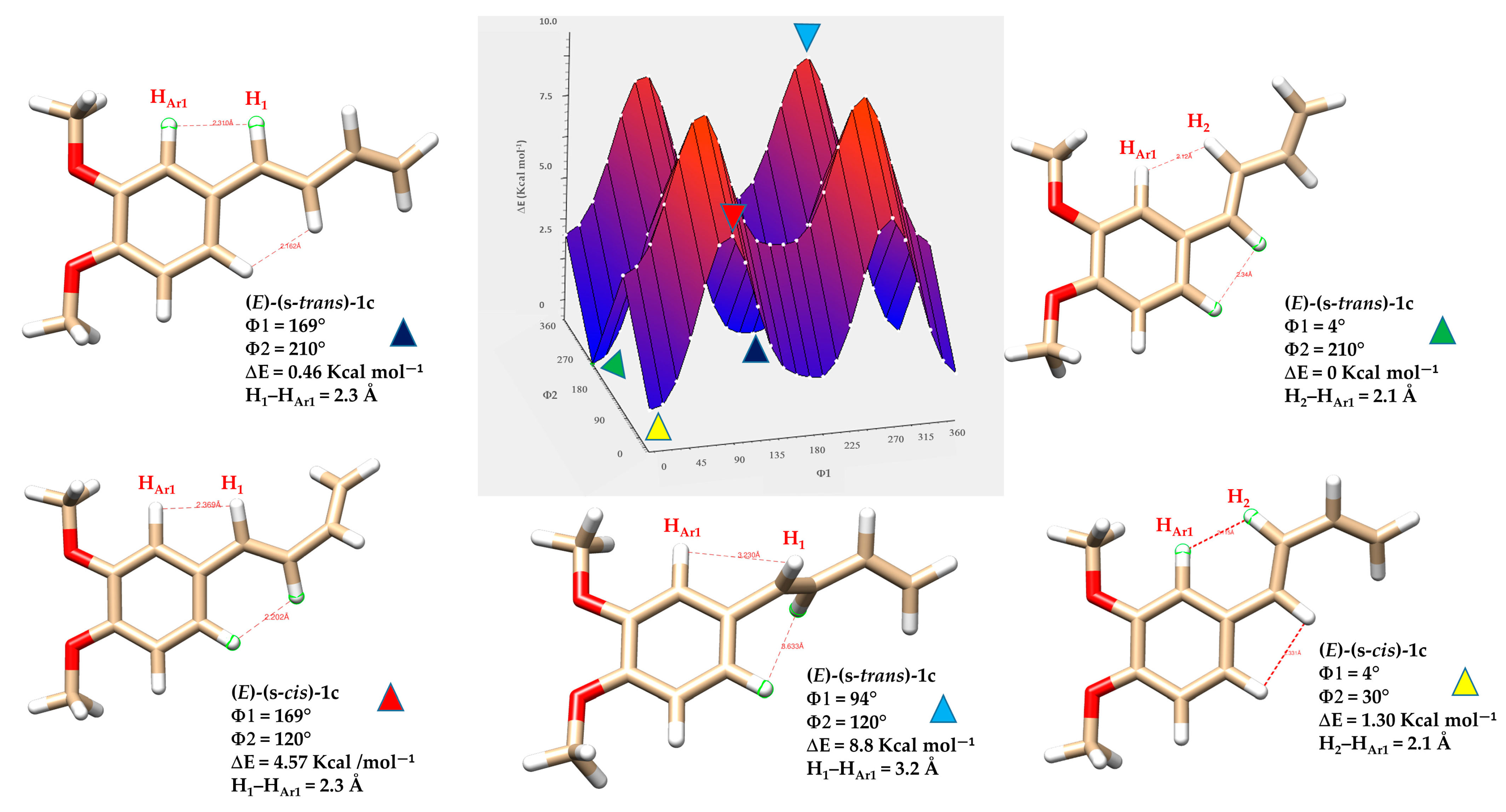

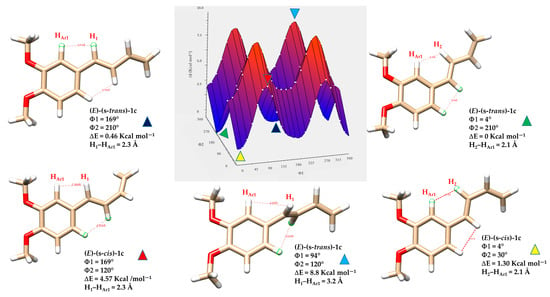

As expected, the (E)-(s-trans)-1c conformers showed a clear link between molecular planarity and stability (Figure 9). The conformer marked by the light blue triangle, with dihedral angles Φ1 = 94° and Φ2 = 120°, demonstrated significant torsion and was the least stable (ΔE = 8.8 kcal·mol−1). This deviation from planarity breaks the conjugation between the butadiene chain and the nearby aromatic ring, significantly reducing π-electron delocalization. In contrast, the most stable conformer, indicated by the green triangle, was almost planar (Φ1 = 4° and Φ2 = 210°), resulting in the lowest relative energy in the series. This nearly coplanar structure allows for optimal orbital overlap between the π-systems of the butadiene and aromatic ring, strengthening conjugation and resonance stabilization. Three other conformers, marked by red, yellow, and blue triangles with intermediate energies, are also shown in Figure 9. The energy differences among these conformers highlight the importance of geometric alignment in stabilizing conjugated systems. Planar conformations promote extensive electron delocalization, which stabilizes the molecule by lowering its energy. Conversely, twisted conformations hinder conjugation, localize electrons, increase electronic repulsion, and raise overall energy. The interplay of steric hindrance, torsional strain, and electronic delocalization is essential in determining the preferred conformations and reactivity of conjugated organic molecules.

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional energy surface and minimized structures of (E)-(s-trans)-1c and (E)-(s-cis)-1c isomers. Selected non-bonded H-H distances, dihedral angles Φ1 (degrees) between the aryl group and the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2, and Φ2 (degrees) defined by the torsion between the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2 and H3-C9-C10-H5, are indicated. Relative energies (ΔE) of each conformer are also provided, highlighting differences in planarity and conjugation.

Similarly to the (E) geometry isomers, the (Z)-(s-trans) and (Z)-(s-cis) conformers of diene 1c show a clear relationship between molecular planarity and relative stability (Figure 9). In these isomers, steric interactions are more significant because of the close spatial proximity between the protons on the butadiene chain and those on the nearby aromatic ring HAr1 and HAr2. In both s-cis conformers, the H5 proton of the butadiene system lies in proximity to the aromatic protons. For the conformer with dihedral angles Φ1 = 143° and Φ2 = 46° (ΔE = 4.9 kcal·mol−1), highlighted by the green triangle, the H5–HAr2 distance is 1.89 Å, suggesting strong through-space interactions, such as intramolecular H-H contacts or weak non-covalent interactions. Similarly, in the conformer with Φ1 = 36° and Φ2 = 46° (ΔE = 4.7 kcal·mol−1), denoted by the red triangle, the H5–HAr1 distance is as short as 1.86 Å. The measured distance, which is well below the typical van der Waals sum for two hydrogens (~2.4 Å), indicates that these protons are unusually close due to specific conformational constraints from the molecular geometry. These non-bonded interactions cause steric hindrance that prevents the molecule from adopting a fully planar shape.

Among all the (Z) conformers, the (Z)-(s-cis) forms encounter more severe steric clashes compared to the (Z)-(s-trans), resulting in a greater loss of planarity and conjugation. Therefore, the (Z)-(s-trans) conformers highlighted by the blue and yellow triangles in Figure 10 are predicted to be more stable than the (Z)-(s-cis) forms due to their relatively less distorted geometry.

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional energy surface and minimized structures of (Z)-(s-trans)-1c and (Z)-(s-cis)-1c isomers of compound 1c. Selected non-bonded H-H distances, dihedral angles Φ1 (degrees) between the aryl group and the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2, and Φ2 (degrees) defined by the torsion between the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2 and H3-C9-C10-H5, are indicated. Relative energies (ΔE) of each conformer are also provided.

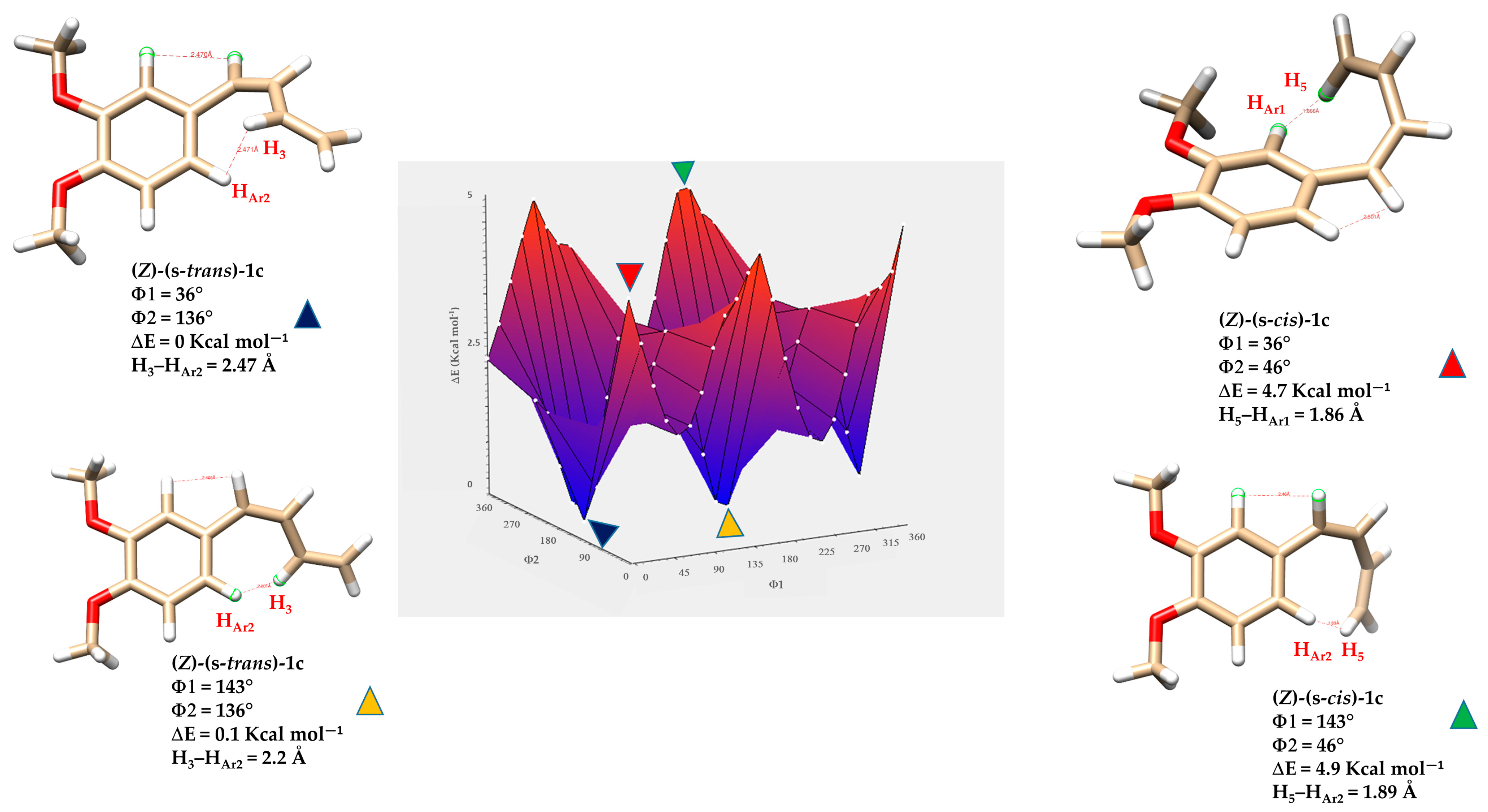

Analysis of the energy-minimized structures of compound 1g, a representative electron-deficient aryl-butadiene system, reveals that the number of possible isomers is reduced by half due to the symmetry of the aromatic ring. Consequently, only four distinct geometrical and conformational isomers are accessible: (E)-(s-trans)-1g, (E)-(s-cis)-1g, (Z)-(s-trans)-1g, and (Z)-(s-cis)-1g.

The incorporation of a strongly electron-withdrawing group, such as a nitro substituent, has a pronounced effect on the relative stabilities of the conformers.

Figure 11 highlights the distinct factors governing the relative stabilities of these conformers. For the (Z)-(s-cis)-1g rotamer (blue triangle), the elevated energy originates from pronounced steric repulsion between the aromatic proton HAr2 and the chain proton H5, a clash not present in the more favorable (Z)-(s-trans)-1g conformer (yellow triangle). By contrast, in the (E)-(s-cis)-1g conformer (purple triangle), destabilization is driven not by sterics but by geometric strain: torsional angles Φ1 and Φ2 approach 270°, effectively interrupting π-conjugation. Taken together, the DFT calculations for diene 1g reveal a pronounced conformational bias, which can be attributed to the electron-deficient character of the aromatic ring and its sensitivity to both steric and electronic perturbations.

Figure 11.

Three-dimensional energy surface and optimized structures of (Z)-(s-trans)-1g, (Z)-(s-cis)-1g, (E)-(s-trans)-1g and (E)-(s-cis)-1g isomers of compound 1g. Selected non-bonded H-H distances, dihedral angles Φ1 (degrees) between the aryl group and the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2, and Φ2 (degrees) defined by the torsion between the planes formed by atoms H1-C7-C8-H2 and H3-C9-C10-H5, are shown. Relative energies (ΔE) of each conformer are also provided.

Overall, the theoretical analysis reveals that the (E)-(s-trans)-1c, (Z)-(s-trans)-1c, (E)-(s-trans)-1g, and (Z)-(s-trans)-1g isomers represent the most stable conformers, as their nearly planar geometries reduce steric hindrance and favour extensive π-conjugation. This arrangement enables efficient orbital overlap between the butadiene chain and the aromatic ring, leading to enhanced electron delocalization and resonance stabilization. By contrast, the (s-cis) conformers, especially those with Z geometry, force hydrogen atoms into proximity, generating unfavorable H-H contacts and significant deviations from planarity that weaken conjugation and increase molecular energy. These combined steric and electronic effects explain the pronounced thermodynamic preference observed for the s-trans conformers across the studied systems.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive investigation of the synthesis, photochemical behavior, and conformational dynamics of a series of (E) and (Z)-1-aryl-1,3-butadiene derivatives. These compounds showed efficient bidirectional (E) ↔ (Z) photoisomerization under UV light, with conversion yields influenced by solvent polarity and aryl substitution. Methanol-d4 emerged as the most effective medium, providing an optimal balance between stability and photoisomerization efficiency. Among the studied derivatives, (E)-1g bearing a para-nitro substituent exhibited the highest photoisomerization efficiency, underscoring the role of electron-withdrawing groups in enhancing excited-state reactivity via π-delocalization and stabilization. NMR analyses, supported by 1H-NMR NOESY correlations, revealed that both isomeric series (E)-1a-g and (Z)-1a-g predominantly adopt s-trans conformations, consistent with an extended, planar-like geometry that facilitates conjugation across the diene framework. Complementary, computational studies further confirmed the energetic preference for s-trans conformers, particularly within the (Z) series, where steric and torsional effects strongly destabilize s-cis arrangements. Detailed conformational energy surfaces for representative compounds 1c and 1g highlighted the influence of aryl substitution on molecular geometry and electronic delocalization. These insights advance the mechanistic understanding of structure–reactivity relationships in photoresponsive butadiene systems and provide a solid framework for the rational molecular design of new photoactive materials, enabling geometric and electronic tuning to optimize key properties such as molecular packing, π-conjugation efficiency, optical absorption, and charge-transport behaviour.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemistry8010004/s1, Figure S1: 1H-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1a. Figure S2: 13C-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1a. Figure S3: 1H-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1b. Figure S4: 13C-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1b. Figure S5: 1H-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1c. Figure S6 13C-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1c. Figure S7: 1H-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1d. Figure S8: 13C-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1d. Figure S9: 1H-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1e. Figure S10: 13C-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1e. Figure S11: 1H-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1f. Figure S12: 13C-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1f. Figure S13: 1H-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1g. Figure S14: 13C-NMR of compound (E)-(s-trans)-1g. Figure S15: 1H-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1a. Figure S16: 13C-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1a. Figure S17: 1H-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1b. Figure S18: 13C-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1b. Figure S19: 1H-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1c. Figure S20: 13C-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1c. Figure S21: 1H-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1d. Figure S22: 13C-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1d. Figure S23: 1H-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1e. Figure S24: 13C-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1e. Figure S25: 1H-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1f. Figure S26: 13C-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1f. Figure S27: 1H-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1g. Figure S28: 13C-NMR of compound (Z)-(s-trans)-1g. Table S1: output energies, dihedral angles Φ1 (with a 15° increment) and Φ2 (with a 90° increment), of compound (E)-1c calculated with Gaussian 16W with the functional M06-2X and 6-311+G-(2d, p) basis set, for a total of 96 points. Table S2: output energies, dihedral angles Φ1 (with a 15° increment) and Φ2 (with a 90° increment), of compound (Z)-1c calculated with Gaussian 16W with the functional M06-2X and 6-311+G-(2d, p) basis set, for a total of 96 points. Table S3: output energies, dihedral angles Φ1 (with a 15° increment) and Φ2 (with a 90° increment), of compound (E)-1g calculated with Gaussian 16W with the functional M06-2X and 6-311+G-(2d, p) basis set, for a total of 96 points. Table S4: output energies, dihedral angles Φ1 (with a 15° increment) and Φ2 (with a 90° increment), of compound (Z)-1g calculated with Gaussian 16W with the functional M06-2X and 6-311+G-(2d, p) basis set, for a total of 96 points.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F. and M.A.D.; methodology, P.C., M.A.D., N.C., M.O. and R.D.; data curation, P.C., N.C., R.D., D.F. and M.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F. and M.A.D.; writing—review and editing, P.C., R.D., N.C. and M.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the CNR project FOE-2022: “Raw Materials of the Future from Non-Critical, Residual, and Renewable Sources” (FutuRaw), through the ordinary fund for research institutions, under Ministerial Decree No. 789 issued on 21 June 2023, subproject DCM.AD005.081.012, CUP B53C23008390005 (Institute of Biomolecular Chemistry, Unit of Sassari, Italy).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seaho, B.; Lekwongphaiboon, C.; Inthakusol, W.; Prateeptongkum, S.; Harnying, W.; Berkessel, A.; Duangdee, N. NMR-based Stability Evaluation of (E)-1-(3′,4′-dimethoxyphenyl)Butadiene (DMPBD) from Zingiber cassumunar Roxb. Rhizome. Phytochem. Anal. 2024, 35, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Iwami, J.; Pongpiriyadacha, Y.; Nakashima, S.; Matsuda, H.; Yoshikawa, M. Chemical Structures of Phenylbutanoids From Rhizomes of Zingiber Cassumunar. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17, 1934578X221077823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, J.R.; Sgariglia, M.A.; Sampietro, D.A.; Quiroga, E.N.; Vattuone, M.A. Free Radical Scavenging Activities and Inhibition of Inflammatory Enzymes of Phenolics Isolated from Tripodanthus Acutifolius. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panichayupakaranant, P.; Kaewchoothong, A. Preparation of Phenylbutanoid-Rich Zingiber Cassumunar Extracts and Simultaneous HPLC Analysis of Phenylbutanoids. Planta Med. 2012, 78, s-0032-1320845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsui, R.; Sriraksa, N.; Thongrong, S. The Neuroprotective Effect of Zingiber Cassumunar Roxb. Extract on LPS-Induced Neuronal Cell Loss and Astroglial Activation within the Hippocampus. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 4259316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Sun, H.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Marcellin, E.; Peng, H. Advancements and Challenges in the Bioproduction of Raspberry Ketone by Precision Fermentation. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keasling, J. Synthetic Biology for Synthetic Chemistry. New Biotechnol. 2014, 31, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, H.; Hifumi, R.; Nishiyama, H.; Inagi, S.; Tomita, I. Synthesis of 1,1,4,4-Tetra-Aryl-1,3-Butadienes Possessing Sulfur Substituents at 2,3-Positions via Dithiol Intermediates and Their Characteristic Electrochromic Behaviors. Chem. Lett. 2024, 53, upad017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.I.; Parker, D.S.N.; Zhang, F.; Landera, A.; Kislov, V.V.; Mebel, A.M. PAH Formation under Single Collision Conditions: Reaction of Phenyl Radical and 1,3-Butadiene to Form 1,4-Dihydronaphthalene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 4248–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S.; Okumura, T. Theoretical Studies on the Substituent Effects for Concerted and Stepwise Mechanisms of the Diels–Alder Reaction between Butadiene and Ethylene. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 2004, 685, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, S.; Fernández, I. Origin of Catalysis and Selectivity in Lewis Acid-Promoted Diels–Alder Reactions Involving Vinylazaarenes as Dienophiles. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 9307–9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Kang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Cui, D. Syndioselective 3,4-Polymerization of 1-Phenyl-1,3-Butadiene by Rare-Earth Metal Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5223–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.E.; Johnson, S.I.; Nielsen, R.J.; Goddard, W.A.; Gunnoe, T.B. Transition-Metal-Mediated Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution with Acids. Organometallics 2016, 35, 2053–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.-L.; Manochai, B.; Pham, T.-T.; Jeong, W.-S. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Zingiber Montanum Oil in HepG2 Cells and Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. J. Med. Food 2021, 24, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeenapongsa, R.; Yoovathaworn, K.; Sriwatanakul, K.M.; Pongprayoon, U.; Sriwatanakul, K. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of (E)-1-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl) Butadiene from Zingiber Cassumunar Roxb. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 87, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neveselý, T.; Wienhold, M.; Molloy, J.J.; Gilmour, R. Advances in the E → Z Isomerization of Alkenes Using Small Molecule Photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2650–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strieth-Kalthoff, F.; Glorius, F. Triplet Energy Transfer Photocatalysis: Unlocking the Next Level. Chem 2020, 6, 1888–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrzynska, K. Ferulic Acid—A Brief Review of Its Extraction, Bioavailability and Biological Activity. Separations 2024, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moni, L.; Banfi, L.; Basso, A.; Mori, A.; Risso, F.; Riva, R.; Lambruschini, C. A Thorough Study on the Photoisomerization of Ferulic Acid Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clampitt, B.H.; Callis, J.W. PHOTOCHEMICAL ISOMERIZATION OF CINNAMIC ACID IN AQUEOUS SOLUTIONS. J. Phys. Chem. 1962, 66, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salum, M.L.; Arroyo Mañez, P.; Luque, F.J.; Erra-Balsells, R. Combined Experimental and Computational Investigation of the Absorption Spectra of E- and Z -Cinnamic Acids in Solution: The Peculiarity of Z -Cinnamics. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 148, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiani, A.; Mammi, S.; Siligardi, G.; Hussain, R.; Tessari, I.; Bubacco, L.; Delogu, G.; Fabbri, D.; Dettori, M.A.; Sanna, D.; et al. Small Molecules Interacting with α-Synuclein: Antiaggregating and Cytoprotective Properties. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profumo, E.; Buttari, B.; D’Arcangelo, D.; Tinaburri, L.; Dettori, M.A.; Fabbri, D.; Delogu, G.; Riganò, R. The Nutraceutical Dehydrozingerone and Its Dimer Counteract Inflammation- and Oxidative Stress-Induced Dysfunction of In Vitro Cultured Human Endothelial Cells: A Novel Perspective for the Prevention and Therapy of Atherosclerosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1246485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, M.A.; Pisano, M.; Rozzo, C.; Delogu, G.; Fabbri, D. Synthesis of Hydroxylated Biphenyl Derivatives Bearing an α,β-Unsaturated Ketone as a Lead Structure for the Development of Drug Candidates against Malignant Melanoma. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, M.A.; Ugone, V.; Fabbri, D.; Carta, P. A Study on the Photoisomerization of (E)-Dehydrozingerone, Its (E)-(E)-C2 Symmetric Dimer, and Their O-Methylated Derivatives. Molecules 2024, 29, 5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.; Banerjee, S.; Malo, S.; Bankura, A.; Ghosh, A.; Das, A.K. Visible Light-Induced Regioselective E to Z Isomerization of Polarized 1,3-Dienes: Experimental and Theoretical Insights. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 15964–15971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; He, S.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, C.; Luo, Y.; Xia, Y. Cobalt-Catalyzed Z to E Geometrical Isomerization of 1,3-Dienes. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 4712–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J. Gaussian 09, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilanova, C.; Sánchez-Péris, M.; Roldán, S.; Dhotare, B.; Carda, M.; Chattopadhyay, A. A Practical Procedure of Low Valent Tin Mediated Barbier Allylation of Aldehydes in Wet Solvent. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 6562–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.A.; Ramakrishna, G.V.; Bethi, V. MnO2 as a Terminal Oxidant in Wacker Oxidation of Homoallyl Alcohols and Terminal Olefins. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 6115–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Figueroa, L.; Tiniakos, A.F.; Prunet, J.; Gamba-Sánchez, D. Water-Compatible Synthesis of 2-Trifluoromethyl-1,3-Dioxanes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 2018, 6929–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, K.; Kazmi, M.Z.H.; Williams, F.J. Structure-Activity Relationship and Bioactivity Studies of Neurotrophic Trans -Banglene. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 2187–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantam, M.L.; Venkanna, G.T.; Kumar, K.B.S.; Balasubrahmanyam, V.; Venkateswarlu, G.; Sreedhar, B. Mild and Efficient Allylation of Aldehydes by Using Copper Fluorapatite as Catalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitoe, A.; Masuda, T.; Nakatani, N. Phenylbutenoid Dimers from the Rhizomes of Zingiber Cassumunar. Phytochemistry 1993, 32, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, T.; Tuzina, P.; Somfai, P. Lewis Acid-Promoted Addition of 1,3-Bis(Silyl)Propenes to Aldehydes: A Route to 1,3-Dienes. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 8070–8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, J.; Ikegami, M.; Mizutani, T.; Wahadoszamen, M.; Momotake, A.; Nishimura, Y.; Arai, T. Solvent Effect on the Photochemical Properties of Symmetrically Substituted Trans-3,3‘,5,5‘-Tetramethoxystilbene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 12566–12571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilorenzo, K.K.; Gilbert, R.M.; Hoggard, P.E. Near-UV Photolysis of μ-Dibromotetrabromo- Dipalladate(II) in Chloroform. J. Coord. Chem. 2010, 63, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, A.Y.S.; Davies, N.L.; Longmire, D.; Packer, M.J.; Chiarparin, E. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Free Ligand Conformations and Atomic Resolution Dynamics. Magn. Reson. 2021, 2, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, P.E. The Synergy between Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Density Functional Theory Calculations. Molecules 2024, 29, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.