Abstract

At present, various carbon materials are available as supports for metal-containing catalytic species. Carbon-based materials find application in many industrial heterogeneous catalytic processes, such as selective hydrogenation, oxidation, cross-coupling, etc. The simplicity of preparation, low cost, high stability, and the possibility of tuning surface composition and porosity cause the widespread use of metal catalysts supported on carbon materials. The surface chemistry of carbon supports plays a crucial role in catalysis, since it allows for control over the sizes of metal particles and their electronic properties. Moreover, metal-free functionalized carbonaceous materials themselves can act as catalysts. In this review, we discuss the recent progress in the field of the application of carbon supports in catalysis by metals, with a focus on the role of carbon surface functionalities and metal-support interactions in catalytic processes used in fine organic synthesis. Among carbon materials, functionalized/doped (O, N, S, P, B) activated carbons, graphenes, carbon nanotubes, graphitic carbon nitride, and carbonizates of polymers are considered supports for mono- and bimetallic nanoparticles.

1. Introduction

Carbon materials are widely used as sorbents and as catalytically active materials and supports for metal-containing species. Different carbon supports are available for catalytic applications; they have a variety of morphologies and chemical compositions, which can be easily tuned for the target reaction. In industry, carbon supports are used in such processes as hydrogenation [1,2,3], oxidation [4], cross-coupling [5,6], and electrocatalytic processes for energy and wastewater purification [7]. The development of carbon-based catalysts is a constantly growing field attracting increasing interest from scientists. In this review, we considered the recent progress in the field of carbon supports for metal-catalyzed processes of fine organic synthesis, with special emphasis on the role of metal support interactions (MSIs).

The advantages of carbon supports as compared to oxidic ones have been described by many authors [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. For example, in the review by Mahene et al. [8], the following advantages were listed:

- (i)

- High stability in acidic or basic medium;

- (ii)

- Possibility to adjust pore sizes for the reaction of interest;

- (iii)

- The presence of different functional groups on the surface, which are responsible for amphoteric properties and interaction with metal species;

- (iv)

- High thermal stability in an oxygen-free medium, which allows for easy reduction of metal-containing precursors;

- (v)

- Relatively low cost;

- (vi)

- Possibility of different shaping (granules, fibers, extrudates, etc.);

- (vii)

- Control over relative hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity by the elimination or addition of O-containing functional groups;

- (viii)

- Simplicity of metal regeneration via the burning of carbon.

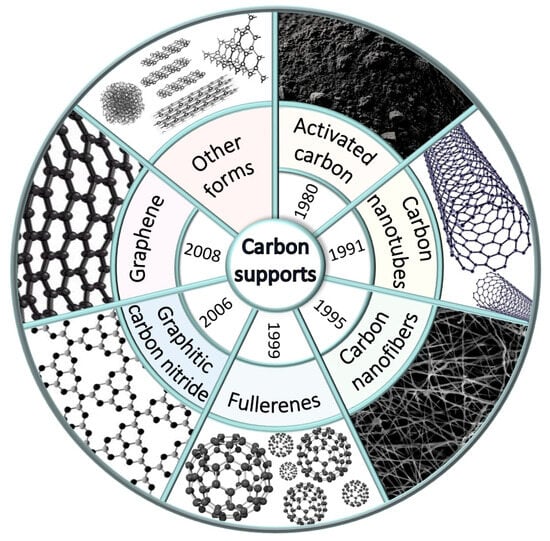

There are different types of carbon supports, i.e., activated carbons (AC), biochars, graphenes, fullerenes, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanofibers, and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) (Figure 1). The structure and properties of main carbon allotropes are described in detail in the review by Awasthi et al. [16].

Figure 1.

Types of carbon supports used in catalysis.

Among the other types of carbon materials, graphene films and foams—which typically find application in adsorption and separation processes [17,18,19], electrochemical reactions [20,21,22,23], and wastewater purification from pollutants [24]—should be mentioned. Although up to date, such materials are not used in fine organic synthesis; we suspect that they can be promising for future application in catalysis.

Thus, carbon materials are considered as favorable supports in catalysis due to their low cost, high thermal conductivity, and variety of functional groups on the surface, which are responsible for the interaction with metal species. However, pure carbon with a uniform sp2-hybridized structure and pristine commercial carbons with a high degree of graphitization have a low number of binding sites for metals and are not suitable for catalysis [9,10,13]. The additional functionalization/doping of carbon supports with O, N, S, B, or P allows for stronger MSI [25] and for the development of metal-free carbon-based catalysts [9,10,11,12].

In the case of carbon-supported metals, several effects can be realized:

- (i)

- Electronic (electron transfer at the metal-support interface);

- (ii)

- Geometric (changes in the shape of metal particles);

- (iii)

- Dispersion (decrease in the sizes of metal particles due to the interaction of metal precursor with functional groups on the carbon surface) [13].

The use of functionalized/doped carbon materials as supports allows not only the reduction of metal particle sizes but also the development of single-atom catalysts (SACs) [26,27,28,29]. SACs have certain advantages over nanoparticulate metal catalysts [26]:

- (i)

- Distinct electronic and physicochemical structure;

- (ii)

- Strong MSI, providing better resistance to aggregation and leaching;

- (iii)

- Low cost due to the 100% utilization of metal atoms.

In addition, carbon supports allow subnanometric metal clusters to be obtained (dimension is between SACs and NPs), which exhibit unique electronic structures and catalytic properties [29].

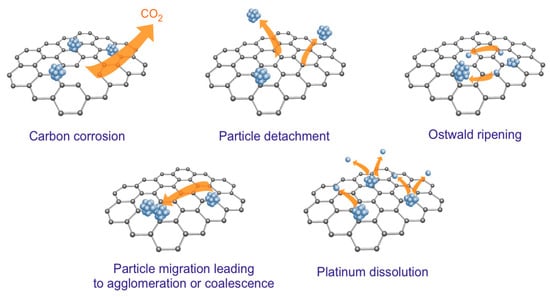

It is noteworthy that carbon-supported metal catalysts are prone to changes in morphology under the influence of reaction conditions that can cause the loss of catalytic activity [30]. Karczmarska et al. [31] highlighted the following potential mechanisms of catalyst deactivation by the example of Pt NPs deposited on carbon support (Figure 2): carbon corrosion, particle detachment, Ostwald ripening, particle migration with following agglomeration or coalescence, and metal dissolution.

Figure 2.

The degradation mechanisms of carbon-supported metal catalysts [31].

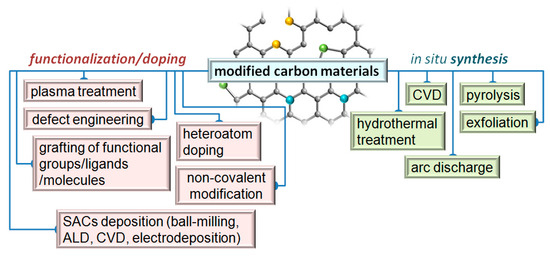

As it was previously mentioned, the functionalization/doping of carbon supports partially resolves the above issues due to the stronger MSI. Heteroatoms or specific functional groups can be introduced into the structure of carbon materials using different methods (Figure 3), which were described in the review by Jabeen et al. [14].

Figure 3.

General representation of the methods of the synthesis and functionalization of carbon-based materials.

In general, all the methods of carbon materials functionalization/doping can be divided into two groups: in situ or ex situ methods [10,32,33,34,35]. The in situ doping is based on the use of heteroatom-containing raw materials (natural carbon sources (biopolymers); metal complexes with heterocyclic ligands; synthetic polymers) for the carbonization process. The ex situ functionalization/doping comprises different types of post-treatment. It should be emphasized that during the introduction of heteroatoms, an increase in the number of defects on the carbon surface takes place that is also favorable for further metal anchoring [10,11,12,13,14]. Campisi et al. [13] noticed that the incorporation of heteroatoms in ordered mesoporous carbons influences the d-spacing and the pore texture differently, i.e., N- and S-doping result in a slight decrease in pore sizes, while B- and P-doping allow for increasing the pore sizes, likely due to the etching of carbon.

A variety of functional groups can be covalently grafted to a carbon surface [10,36,37,38]. Moreover, the –NH2 and –SH groups can be used to create amide or thiol bonds with grafted molecules [39]. However, for electrochemical purposes, it should be taken into account that the process of grafting, which requires oxidation treatment, results in a decrease in carbon conductivity and long-term stability. In contrast, heteroatom doping by annealing allows for the recovery of the graphitic structure and an increase in carbon conductivity [10]. It is noteworthy that the modification of carbon materials with the additional functional groups not only results in a change in their electrochemical properties but also alters surface acidity (introduction of –SO3H, –COOH, and –OH groups) [10,15,16], which allows for the synthesis of acid/base catalysts or co-catalysts. Non-covalent modification of the carbon surface can also be carried out by electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions [10,40,41,42,43]. For example, in the work of Liu et al. [43], the adsorption of a cobalt complex with 1,10-phenanthroline on the surface of carbon black was carried out, which allowed, after calcinations and pyrolysis, Co SAC deposited on carbon nitride to be obtained.

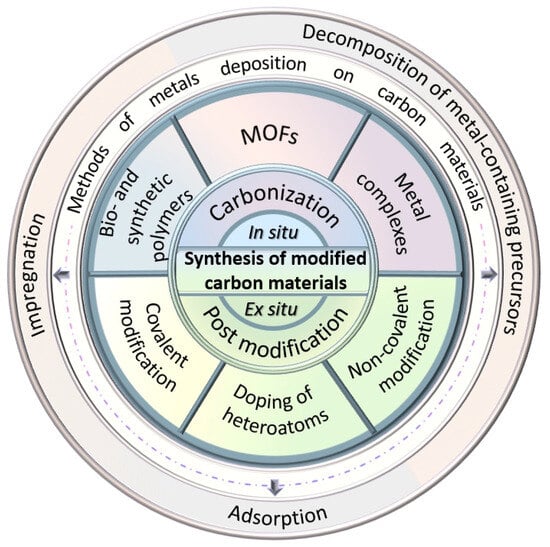

The main approaches to carbon modification (functionalization/doping) are summarized in Figure 4, which also depicts some methods of metal deposition on carbon supports, such as the following:

Figure 4.

Main approaches to carbon functionalization/doping and metal deposition.

- (i)

- Thermal decomposition of metal-containing precursors (metal complexes, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), etc.). In many cases this method is used to simultaneously obtain carbon and confine metal atoms or particles;

- (ii)

- Adsorption of metals from solutions with further formation of metal particles during either in situ or ex situ (after catalyst separation) reduction;

- (iii)

- Incipient wetness impregnation (IWI).

It should be noted that other methods, such as ball-milling, atomic layer deposition, electrochemical deposition, and chemical vapor deposition, can also be used [28,33,34,44], especially for the synthesis of SACs [28].

2. Functionalization/Doping of Carbon Materials with Heteroatoms

One of the simplest functionalization methods is to oxidize the surface of carbon materials, which can be carried out by treatment with different oxidants (O2, O3, N2O, (NH4)2S2O8, H2O2, H2SO4, HNO3, or their combination) in a liquid or gas phase [8,9,10,45,46,47,48]. In most of the works nitric acid was used as an oxidant due to its higher efficiency. For example, Li et al. [47] found that the treatment of AC with HNO3 allowed for a 4–6-fold increase in the concentration of O-groups as compared to H2O2 and other oxidants, which, in turn, caused the mean diameters of Co NPs to decrease from 8 nm to ca. 5 nm.

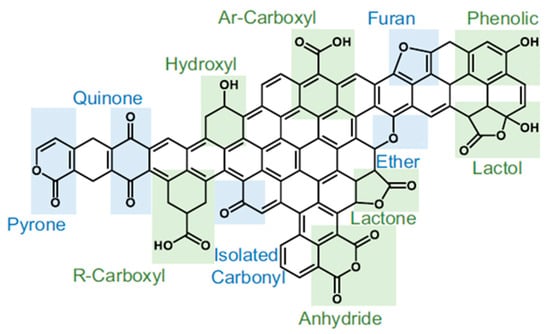

As a result of oxidation, a variety of O-containing groups can form (see Figure 5) [9]; these can be divided into acidic, basic, or neutral categories [8,9].

Figure 5.

Diversity of O-containing functional groups on the carbon surface. Modified from ref. [9].

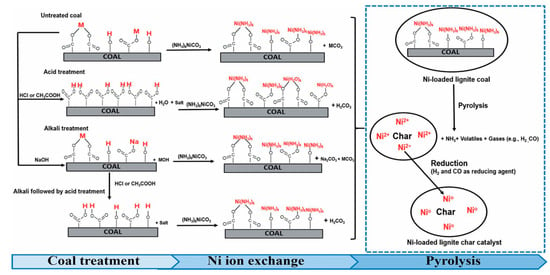

Carboxyl groups, anhydrides, lactols, lactones, and phenolic OH groups can be ascribed to the acidic category. Isolated carbonyl can be neutral, while furan, ether group, pyrone, quinone, and chromene may reveal basic properties [8]. The oxidation of the carbon surface in general increases its acidity [47], which favors the interaction with metal cations [48] (note that basic groups are mainly responsible for the interaction with anionic metal species [8]) during the adsorption or the IWI. As shown by Tipo et al. [49], the treatment of coal with acid or alkali solutions influences the O-groups, i.e., OH groups and carboxyl groups, which serve as cation-exchange sites. In particular, the use of CH3COOH and NaOH resulted in an increase in Ni content in the catalysts from about 16.5 wt.% (for the untreated coal) to 17 wt.% and 20 wt.%, respectively [49]. In addition, the method of coal treatment influenced the mechanism of metal loading (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The pathways for the preparation of Ni-loaded lignite char catalysts [49].

In the case of alkali treatment, hydroxyl and metal-carboxylate groups were the sites for the Ni ion exchange, while in the case of acid treatment, the exchange of Ni ions occurred through the carboxyl groups [49].

Thus, the acidic oxygen groups allow for increasing the uniformity of metal distribution and decreasing the particle sizes [9]. However, O-containing groups are unstable at high temperatures. Moreover, different oxygen groups possess different thermal stabilities; thus, by varying the temperature, one can influence surface acidity/basicity and hydrophilicity [8,47]. It should be emphasized that under the influence of reaction conditions, the O-containing groups can be transformed into one another, which complicates their quantitative estimation and impact on the catalytic process.

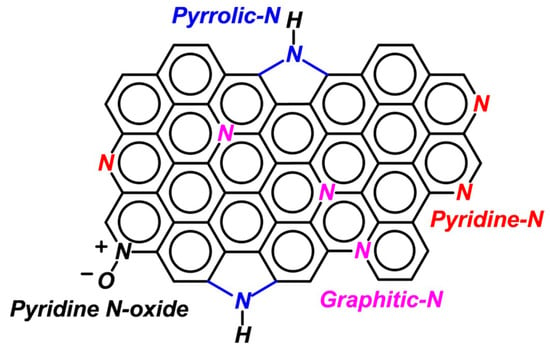

In the case of N-doped carbon, nitrogen can be in the form of graphitic N (or quaternary N), pyridinic N, pyrrolic N (Figure 7), and pyridine N-oxide [8,32,34,44,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58].

Figure 7.

C@N bonding states into N-doped carbon nanomaterials. Reproduced with permission from [34], John Wiley and Sons, 2020.

Among the element dopants (O, N, S, P, B, halogens, some metals), N is the most widespread since it has a number of advantages [34]:

- (i)

- Relative simplicity of doping;

- (ii)

- Tuning of electronic properties while introducing N atoms in the aromatic rings;

- (iii)

- Negligible difference in atomic radii of N and C, which prevents significant lattice mismatches;

- (iv)

- Ability to produce semiconducting materials for electronic application.

In some fields of application, including catalysis, the graphitic N is the preferable form [59,60,61,62,63,64], while in others the pyrrolic N [53,56,64,65] or pyridinic N [33,55,58,66,67] is better. For example, Tian et al. [56] reported on one of the pure pyrrolic carbon materials with pseudocapacitance properties, which were positively dependent on the content of pyrrolic N. Moreover, pyrrolic N has high resistance to carbon corrosion and CO2 formation at elevated temperatures [68]. Interestingly, the introduction of pyrrolic N favors the formation of a specific form of carbon – bamboo-like CNTs, which are used in electrochemical processes [69,70,71,72,73]. Some authors highlight that different forms of nitrogen mutually influence each other, and there are synergistic effects between them [61,74]. Shang et al. [57] revealed that pyridinic N can suppress the activity of neighboring pyrrolic N in the CO2 reduction reaction.

N-doping creates defects and causes a shift in electron density (from C to N) [8,33,50]; the latter favors the interaction of AC atoms with the catalytically active phase. Aside from defect formation and the increase in the number of anchoring sites, N-doping increases surface hydrophilicity and improves the nucleation of metals by changing the p-electron delocalization [75]. Thus, MSI is more often observed in N-doped carbon materials than in other modified supports and pure (undoped) surfaces. It is noteworthy that the MSI effect may also result from the stabilization of key intermediates of the catalytic reaction [76]. The location of nitrogen atoms in graphite layers can result in porphyrin-type structures, which allow for the formation of SACs [8]. The pyridinic N is preferable for metal anchoring due to its better electron-donating properties in comparison with other forms of nitrogen [33,66,67]. The interaction of metal ions with pyridinic N also increases their reducibility, which is important in catalytic hydrogenation, since it not only allows for higher catalytic activity but also prevents the reoxidation of the reduced metal atoms [66].

Obviously, nitrogen doping influences the acid/base properties of the carbon surface. In particular, among the nitrogen forms, pyridinic N, possessing the strongest electron-donating ability, mostly contributes to the Lewis basicity of N-doped materials, while graphitic N reveals the least basic properties [77,78]. The ratio between different forms of nitrogen, and hence the surface basicity, can be tuned to some extent by the following approaches:

- (i)

- The number of defects or edges can be increased by a corresponding increase in the concentration of pyridinic N, since it is known that the pyridinic N prefers to occupy the edges or defects of the carbon materials [55];

- (ii)

- Thermal treatment of N-doped material allows the ratio between different forms of nitrogen to shift [54,63], i.e., a gradual increase in annealing temperature results in a decrease in the concentration of pyridinic N and a corresponding increase in the amount of pyrrolic N and then quaternary N (the most thermally stable nitrogen form).

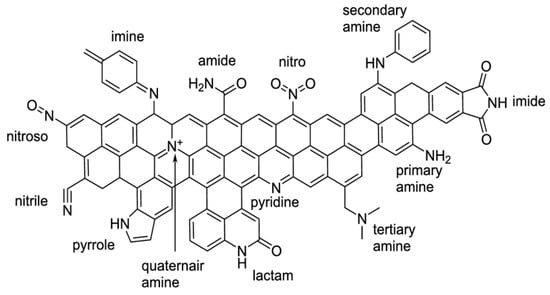

N-doping can be carried out by different methods: chemical vapor deposition [34,44], hydrothermal treatment [33,34,59], pyrolysis [33,34,43,44,55] of carbon supports treated with N-containing organic precursors (typically N-heterocycles), and pyrolysis of nitrogen-containing polymers [34,35]. Pyrolysis methods have certain drawbacks. Thus, Tian et al. [56] underscored that at temperatures above ~600 °C, nitrogen loss and uncontrollable conversion among different types of nitrogen take place, while temperatures below ~600 °C result in a low degree of graphitization and hence in poor electrical conductivity. Besides the N-heterocycles, other sources of nitrogen, such as NH3, ammonium salts, hydrazine, urea, various amides, and amino acids, should be mentioned [32,33,79]. If AC, which contains oxygen on its surface, underwent functionalization with nitrogen in the absence of any additional high-temperature treatment, e.g., pyrolysis, a wide range of N-containing groups would be found on the surface (Figure 8) [57,80].

Figure 8.

Overview of N-containing functional groups on the surface of ACs [80].

P-containing materials can be produced by treating carbon with H3PO4 or KH2PO4 with further thermochemical activation, which results in the formation of a variety of C-O-P groups, such as (CO)3PO, (CO)2PO2, C-PO3, C2-PO2, and C3-PO [81,82,83,84,85,86]. Such groups allow the increased graphite layer spacing and defect content, hence anchoring metal NPs and reducing their aggregation [82]. It is noteworthy that treatment with phosphoric acid, as well as the use of alkalis, is a typical procedure for chemical activation of carbons [87,88,89,90]. Liu et al. mentioned that H3PO4 is more beneficial than HNO3, which is strongly corrosive [84]. Triphenylphosphine (TPP) can be used as another source of phosphorus for carbon modification. After calcinations, the adsorbed TPP can be transformed to (PO3)− and (PO4)3− species [91]. Decomposition of phosphorus-containing precursors, such as phytic acid, also results in the formation of P-doped carbon materials [92].

Phosphorus atoms can be introduced directly into the carbon structure. Recently, Kim et al. [93] proposed the spin-on-dopant method to introduce P atoms in the surface of highly crystalline carbon. They showed [93] that P-doping creates numerous nucleation and anchoring sites for the Pt NP catalysts while preserving the crystallinity of carbon. Thus, the sizes of Pt NPs decreased by almost half, from ca. 5.9 nm (for the undoped material) to about 2.4 nm (for the P-doped carbon).

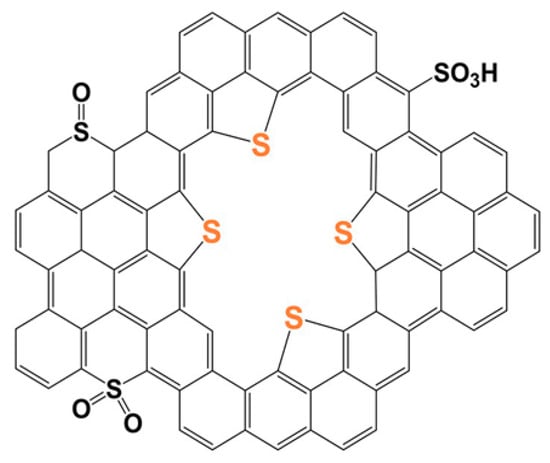

The most widespread methods of synthesizing sulfur-containing carbons are the use of S-heterocycles (e.g., thiophene and its derivatives) or S-containing polymers as precursors [94,95] and the sulfonation procedure [96,97,98,99,100]. The first method allows S-doped material with C–S–C bonds along with oxidized S to be obtained, while the sulfonation procedure results mainly in the formation of surface –SO3H groups (Figure 9), which can serve as metal-free catalysts for hydrolysis and esterification.

Figure 9.

Chemical states of sulfur species in carbon. Reproduced with permission from [86], John Wiley and Sons, 2023.

Similarly to other heteroatoms, S-doping led to different MSI effects, which were described in detail in the review by Yin et al. [95]. Three types of strong MSIs were distinguished [95]: (i) classic strong MSI (encapsulation effect), (ii) electronic MSI, and (iii) reactive MSI. Electronic MSI occurs when there is a charge transfer between metal and S–C, which, in turn, depends on the type of doped S and metal properties. For example, the deprotonated sulfhydryl groups possess electron acceptor properties (due to their electronegativity), while in the case of doped S atoms, the thiophene heterocycles may act both as electron donors and acceptors. Reactive MSI involves the formation of the M–S–C configuration, which causes the extraction of sulfur atoms from the supports and their diffusion into the metal lattice. Thus, metal sulfides can form that may be considered as poisoned, but in some reactions (hydrodesulfurization, different electrocatalytic processes), metal sulfide particles exhibit promising activity [101,102,103,104,105].

In the case of B-doping, boron [106,107], boric acid [108,109,110,111,112,113], triphenylborane [114], or sodium borohydride [115,116,117] can be used as the source of B atoms. Boron atoms create defects on the carbon surface, which can serve as anchoring sites for metal NPs [109], and exhibit weak Lewis acidity [106]. Boron has a lower electronegativity than carbon, which causes the donation of electrons from B to C [75]. Moreover, B-doping can preserve the porosity of carbon material [109]. After doping, different types of bonds can be found: B–C, B–O–H, B–O (in B2O3) [110], B–O–C [111], and B=C [107]. The latter can be found if the duration of annealing is too long and B4C is formed. Recently, Choi et al. [117] synthesized curved B4C sites, which allowed for high activity and selectivity in the 2e− oxygen reduction reaction in neutral electrolytes. Xia et al. [75] distinguished two types of B configuration: (i) in-plane, in which B atoms are sp2-hybridized in the carbon lattice; and (ii) vacant-sites doping, in which BC4 is formed, resulting in torture of the carbon lattice.

The formation energy of B-doped carbon (BC) (~5.6 eV·atom−1) is lower than that of N-doped carbon (NC) (8.0 eV·atom−1); hence, the synthesis of BC can be carried out under milder conditions in comparison with that of NC [75]. In most cases, B is introduced in carbon material by the ex situ methods (post-modification). However, in some cases B-doping can be carried out by the decomposition of a polymer as a carbon source in the presence of a boron source [111]. A combination of both the in situ and ex situ methods can also be used. For example, Byeon et al. [116] reported the synthesis of BC from CO2 and NaBH4, which further underwent treatment with CO2 in order to increase the surface area and expand the edge defect sites and was additionally B-doped by annealing with boric acid.

Finally, the functionalization/doping of carbon materials with several heteroatoms simultaneously is possible [118,119,120,121,122,123,124]. For example, in the work of Cruz-Silva et al. [120], multiwalled PN-doped CNTs were synthesized for the first time by spray pyrolysis using ferrocene, TPP (source of P), and benzylamine (source of C and N). It was found that stable PN defects formed on the CNTs’ surface, and the resulting PN-doped CNTs could be used as fast-response chemical sensors. Using α-cellulose and ammonium phosphate, Xie et al. [121] obtained NP-doped carbon acting as a metal-free catalyst for the reduction of p-nitrophenol. It was proposed that the O-groups of α-cellulose caused, after the annealing, the formation of unstable defects in the carbon skeleton, which then reacted with H3PO4 and NH3 produced by the decomposition of (NH4)2HPO4. The resulting carbon material contained 4.3 at.% of N, 10.6 at.% of P, and about 33.6 at.% of O on the surface and revealed high activity in hydrogenation of p-nitrophenol: the TOF reached values of 2 × 105 mmol/(mg·min), which were comparable to those of noble metal-based catalysts and conventional graphene-based catalysts [121]. Heteroatoms (B, S, and N) doped nanoporous carbon with supercapacitor properties was obtained by Bahadur et al. [123] using casein (carbon source), boric acid, and dithiooxamide (source for S and N). Miao et al. [124] reported the synthesis of Pd NPs supported on NH2-functionalized P-doped glucose-based porous carbon, in which the amino-groups were likely responsible for dehydrogenation of formic acid, while phosphorus atoms served as electronic promoters and anchoring sites for Pd. As a result, the obtained Pd/NH2-P-GC material possessed exceptional catalytic activity, 100% H2 selectivity, and undetectable CO generation in the reaction of formic acid dehydrogenation without the need for any additive.

Thus, functionalized/doped carbon materials are versatile and promising supports for catalytically active metal species. Carbon-based catalysts are widely used in electrochemical processes [125], such as oxygen reduction reaction [54,55,58,62,63,72,111,114,118,126], oxygen evolution reaction [25,104,127], hydrogen evolution reaction [29,82,119,128], COx reduction [27,50,57,129,130], peroxymonosulfate activation [43,131], and dehydrogenation of formic acid [109,124], and in the synthesis of fuel hydrocarbons, e.g., Fischer–Tropsch reaction [45,47,132] and pyrolysis [49,133]. However, there is a limited number of publications devoted to the use of carbon-supported catalysts in fine organic synthesis. Below we will provide the recent and most relevant examples of MSI effects for metal-containing carbon-supported catalysts used in the reactions of oxidation, hydrogenation, hydrochlorination, carbonylation, esterification, etc., with organic compounds.

3. Functionalized Carbons as Supports

AC is one of the most widely used carbon supports in catalysis. Carbon materials typically represent a combination of amorphous and graphitic particles [12]. Amorphous carbon has a significant impact on the mechanical and physicochemical properties of carbon materials [134]. AC is an amorphous carbon with a high specific surface area (SSA) [46,80], varying in a wide range from about 900 m2/g up to 3000 m2/g and even higher [46,135]. High SSA, abundant functional groups, and high thermal and chemical stability make ACs convenient supports in catalysis [15]. ACs can be obtained from different carbon sources (wood, peat, petroleum pitch, plant wastes, etc.) [46,80,136] and have granules of varying shapes and sizes. In addition, depending on the activation procedure (physical or chemical activation), ACs may possess different surface compositions and physicochemical properties [137]; hence, it is possible to manipulate and optimize the nature of active sites and selectivity [8]. Chemical doping of ACs can be performed by loading metals/metal oxides/hydroxides or heteroatoms (O, N, P, etc.) [138].

3.1. O-Functionalized Carbons

Heteroatoms are part of the raw materials and/or the chemicals used in carbon activation [137]. O-groups are the most widespread groups on the AC surface. Oxygen atoms are located at the edges or corners of crystal structures and form a wide range of functional groups (Figure 5). As discussed above, the introduction of O-groups influences AC porosity, surface hydrophilicity, and the process of metal attachment.

Among the carbon-supported metal catalysts, Pd/C is the most widespread. There are many commercially available Pd/C catalytic systems, which differ in terms of metal loading, oxidation state, and carbon support characteristics. Crawford et al. [139] highlighted the following key features of Pd/C catalysts that make them efficient, particularly in hydrogenolysis processes: (i) small Pd/PdO NPs; (ii) homogeneous distribution of Pd/PdO on the carbon support; and (iii) the palladium oxidation state (presence of both Pd0 and Pd2+) [139]. It is obvious that important parameters such as the sizes and distribution of Pd-containing NPs can be regulated by the porous structure and surface chemistry of the supports. The MSI between Pd species and carbon materials is especially important for such reactions as cross-coupling [14,140], in which not only the sizes of Pd particles but also the prevention of metal leaching are tremendous factors.

In the work of Kumar et al. [141], the series of catalysts based on Pd and ZrO2 or MoO3 NPs and deposited on commercial AC or activated biochar obtained from a mixture of biomass and polymeric wastes and oxidized with HNO3 [142] were synthesized. Catalysts were tested in the transfer hydrogenolysis of lignin to monomeric phenols, especially alkyl guaiacols and vanillin/vanillin derivatives. Activated biochar, in comparison with commercial AC, had a lower SSA, degree of graphitization, and oxygen content (ca. 17% vs. about 24% for the AC). Although the NP sizes were not estimated, it seems that smaller Pd NPs were formed in the case of the activated biochar. Nevertheless, higher lignin conversion (~45.8%) was achieved in the presence of AC-supported catalysts compared to the ones supported on the activated biochar (39–41%) [141].

Commercial carbon in the form of graphene nanoplatelets (GNP) was used as a support for Pd NPs by Stucchi et al. [143]. In the series of catalysts, the amount of O-containing species was varied. Surprisingly, the sizes of Pd-containing NPs were close for all the samples (about 3.5–3.9 nm), while the reducibility was different, i.e., the higher oxygen content unexpectedly caused the Pd0/Pd2+ ratio to nearly double. In spite of the higher Pd0/Pd2+ ratio, the activity of Pd NPs deposited on the surface of more oxidized GNP (GNP-functionalized) in the reaction of benzaldehyde hydrodeoxygenation to benzyl alcohol and toluene was lower in comparison with the GNP, which was likely due to the weaker interaction of the carbonyl group of benzaldehyde with the surface of GNP-functionalized [143].

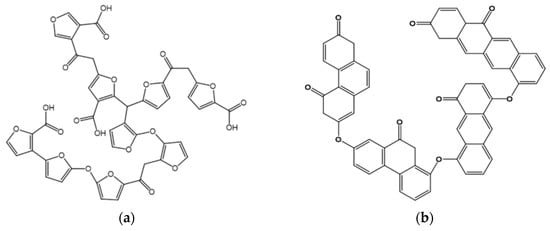

Oxygen-enriched carbon materials were synthesized by Bateni et al. [144] using the bottom-up approach based on the hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) of D-glucose or soft-templated evaporation-induced self-assembly of resorcinol and formaldehyde in the presence of Pluronic F-127 (soft template) followed by carbonization. The HTC material presumably consisted of furan cycles, while the mesoporous carbon (MC) synthesized by the developed self-assembly method contained condensed aromatic rings with carbonyl groups (Figure 10). The samples obtained by the HTC method were annealed (200–800 °C), which resulted in the gradual decrease of oxygen content from 32 wt.% (for the as-synthesized carbon material) to 2 wt.%. In the case of MC, the highly annealed (1000 °C) sample was prepared and then reoxidized with concentrated HNO3 at 80 °C for 24 h. Oxidized MC samples were also annealed at 200–800 °C, which also caused a decrease in oxygen content from 26.4 wt.% to 4.7 wt.%.

Figure 10.

Proposed structures for (a) as-synthesized HTC material and (b) MC obtained from carbonized phenolic resin [144].

The series of Pd-containing catalysts with a metal loading of about 4.5–4.8 wt.% was synthesized by the IWI method using the MC materials [144]. For the initial as-carbonized (at 400 °C) MC, the aggregates of Pd NPs with diameters of about 10–15 nm were formed, while in the case of the oxidized MC samples, irrespective of the annealing temperature (200–800 °C), small (ca. 4.3–4.6 nm) uniformly distributed NPs were found. Although the authors [144] did not estimate the catalytic properties of the synthesized carbon-supported Pd NPs, we propose such materials to be promising.

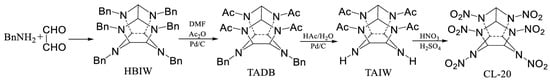

Chen et al. [145,146] reported the synthesis of Pd NPs supported on flowerlike carbon nanosheets (NSC), which were prepared by hydrothermal treatment of glucose in the presence of zinc acetate and silica. To study the role of surface chemistry, the samples of NSC were treated with 10–30 wt.% solutions of nitric acid at 50 °C for 2 h. In addition, the initial NSC material was calcinated at 600 °C for 2 h. The concentration of carboxylic groups was found to increase in the following order: Pd/NSC-600 < Pd/NSC < Pd/NSCox-2 (treated with 20 wt.% solution of HNO3). The sizes of Pd NPs in the as-synthesized (unreduced) catalysts containing 5 wt.% of Pd were found to decrease from about 5 nm to 2 nm in the same order, indicating that there is a direct relationship between the concentration of –COOH groups and the Pd dispersion. Synthesized catalysts were tested in the reaction of hydrogenolytic debenzylation of tetraacetyldibenzylhexaazaisowurtzitane (TADB)—a representative of high-energy-density materials—at ambient H2 pressure and 45 °C for 10 h (Figure 11). The catalytic activity was found to increase with a corresponding decrease in the mean diameters of Pd NPs, highlighting the role of O-containing surface species in the development of effective catalytic systems.

Figure 11.

Route to synthesis of hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20) [146].

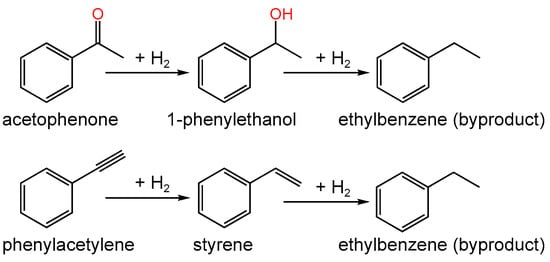

You et al. [147] demonstrated that, after the reduction of commercial Pd/C (5 wt.% of Pd in the form of PdO) with H2 at different temperatures (60, 500, and 800 °C), the content of C=O species on the catalyst surface decreased from 44% to 22% (XPS data) with a corresponding increase in temperature, while the sizes of Pd NPs increased from 3.2 nm (after the reduction at 60 °C) to 7 nm (500 °C) and 22 nm (800 °C). It was found that the decrease in oxygen content caused a decrease in hydrogenation activity for acetophenone but an increase for phenylacetylene (Figure 12). This fact was likely due to the obvious difference in the polarities of the chosen compounds (note that H2 treatment also resulted in the reduction in Pd/oxide sites) and also to the necessity of the Pd(0) surface rather than edge or corner atoms, in the case of phenylacetylene [147].

Figure 12.

Simplified schemes of hydrogenation of acetophenone and phenylacetylene (in [147] the final reaction mixture contained 1-phenylethanol, styrene, and ethylbenzene).

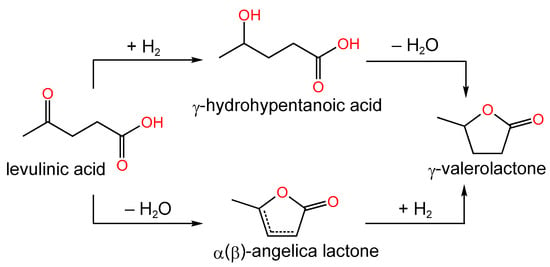

The importance of the MSI, determined by the existence of heteroatom dopants and functional groups on the carbon surface, for ensuring high dispersion of Ru-containing particles was described in detail in the review by Zhao et al. [148]. The group of scientists under the guidance of Román-Martínez M.C. [149,150,151] developed carbon-supported Ru- and Ni-containing catalysts for the reaction of levulinic acid hydrogenation to gamma-valerolactone (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Simplified scheme of levulinic acid hydrogenation.

For the series of Ru/C catalysts synthesized while using different carbons, it was found [151] that an increase in surface acidity results in a corresponding increase in ruthenium reducibility during treatment in a hydrogen flow at 250 °C. The only exception was when Ru was deposited on SA-30 carbon in the form of fine powder, in contrast to other granular samples. In the case of preliminarily reduced catalysts, the increase in surface acidity also resulted in a slight decrease in the mean diameter of Ru-containing NPs from about 3.2 nm to 2.2 nm and a corresponding increase in levulinic acid conversion from 81% to 94% for 1 h at 70 °C and 15 bar H2. In contrast, the samples with high surface acidity, which were reduced in situ under the reaction conditions, revealed noticeably lower activity in comparison with the preliminarily reduced ones. This was likely due to the formation of too-small NPs, about 1 nm in diameter and smaller, during the first run [151].

Regarding Ba-promoted Ru/AC, Ni et al. [152] found that the gas-phase oxidation of AC with HNO3 allowed for a decrease in the mean diameters of Ru NPs, from 3.4 nm to 2.3 nm. It was also proposed that O-groups can facilitate the migration of hydrogen from Ru NPs to carbon support and hence enhance hydrogen uptake. Then, H atoms can be stored on the carbon surface in the form of OH groups.

Surface O-groups can also participate in catalysis through the activation of deposited metal. Thus, Huang et al. [153] found that ball-milling of powdered activated carbon results in the generation of carbon radicals, which undergo a cascade of O2-dependent reactions producing hydroxyl groups. Hydroxyl groups, in turn, favor the adsorption of Mn(VII), which forms metastable complexes with elevated redox potential and enhanced catalytic activity in the oxidation of organic pollutants, such as phenols.

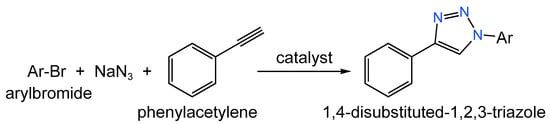

Carbon supports can be used not only for the deposition of metal-containing NPs, but also for metal complexes. For example, Librando et al. [154] used AC and CNTs oxidized with HNO3 to immobilize iodo-Cu(I)-DAPTA (3,7-diacetyl-1,3,7-triaza- 5-phosphabicyclo-[3.3.1]nonane) complexes—catalysts for the one-pot synthesis of 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazoles (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Scheme of the synthesis of 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazoles.

The reaction was carried out under the following conditions: 0.30 mmol of benzyl bromide, 0.33 mmol of phenylacetylene, 0.33 mmol of NaN3, solvent—H2O: MeCN (1:1 v/v), 80 °C, and catalyst loading 0.5 mol.%. Oxidized supports possessed higher efficiency compared to the initial ones due to the increase in the number of surface O-groups, which might act as coordination sites for the copper complexes. Thus, at the relatively low copper loading of 1.5–1.6% (w/w), quantitative conversions were obtained for 15 min. Moreover, the immobilized complexes were separated by simple filtration and reused for up to four consecutive runs [154].

A number of publications are devoted to hydrochlorination processes. Hydrochlorination of acetylene [155] is used in the industrial manufacture of polyvinyl chloride and traditionally is a mercury-catalyzed reaction. However, there are a variety of mercury-free catalysts, including those supported on carbons. Fu et al. [156] reported a series of Cu-containing catalysts (5 wt.% of Cu) prepared by the dry mixing method in which CuCl was dry mixed with AC treated with nitric acid. Copper, in the form of two-dimensional small clusters and single atoms, was uniformly distributed on a carbon support that provided high activity and stability of the developed catalysts in acetylene hydrochlorination. Among the carbon-supported noble metal catalysts for hydrochlorination, Pt, Au, and Ru are mentioned [157,158]. Kaiser et al. [157] synthesized Pt SACs (1 wt.% of Pt) by the IWI method using ACs with different oxygen contents as the supports. Pt was stabilized on the O-sites on the ACs surface. It is noteworthy that during IWI, a partial reduction in Pt(IV) to Pt(II) occurred, but, in our opinion, the reduction degree is difficult to correlate with the oxygen content since all the catalysts were air-dried at 473 K. Moreover, catalytic activity was found to be virtually independent of oxygen content, while porosity was the main influencing factor. Thus, the stability of Pt SACs depended on the concentration of acidic groups, which favored catalyst inactivation due to the side reactions of polymerization and coke formation, resulting in the pore blockage [157]. These dependencies were also established for Ru- and Au-containing carbon-supported catalysts: oxygen groups serve as anchoring sites for metals, hence, providing the desirable dispersion; at the same time, the excessive amount of O-containing acidic groups causes catalyst inactivation.

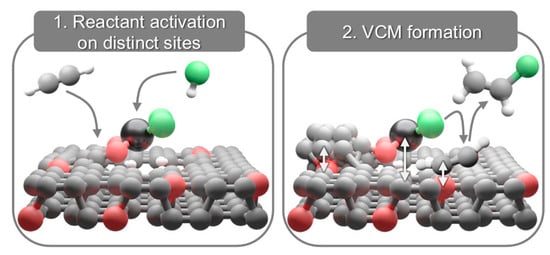

Later, Giulimondi et al. [158] provided evidence that carbon supports are active participants in the hydrochlorination reaction. It was proven that metal atoms are responsible for HCl activation, while surrounding carbon (near the SACs) provides the acetylene activation, irrespective of the carbon functionalization (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Metal and carbon sites activate hydrogen chloride and acetylene, respectively (left). Metal atoms mediate chloride supply to acetylene for vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) formation, while carbon surface functionalities regulate acetylene adsorption and coke formation (right) [158].

In addition, the functionalization of ACs influences the stability and dynamic behavior of SACs under the reaction environment. For example, it was found that NC, as compared to the non-functionalized AC, allows for lower aggregation of Pt SACs as well as for the absence of structural changes (loss of chlorine ligands) in the presence of acetylene [158]. Similarly, in the case of Au-containing hydrochlorination catalysts, the O-groups on the surface of oxidized AC were shown to provide high dispersion (single-atom state) and the formation of active AuClx species under the reaction conditions [159]. An interesting work was published by Wang et al. [160], who modified the surface of carbon-supported Au catalyst with an ionic liquid, which served as a medium for HCl storage and allowed for further intensification of acetylene hydrochlorination. Deposition of ionic liquid, along with the support modification and the addition of ligands, can also be used for intensification of the hydrodechlorination (HDC) reaction in the presence of Ru-containing catalysts [161], which are less effective compared to Pt and Au catalysts.

3.2. N-Functionalized Carbons

Nitrogen-doped carbon materials are widely used for water purification from organic pollutants [43,162] and for electrochemical processes [128,163]. Functionalization of carbon with N-groups can be carried out by either in situ or ex situ methods. The most popular method of carbon modification is the deposition of N-heterocycles, e.g., 1,10-phenanthroline, or other N-containing compounds (amines) with further calcination. 1,10-phenanthroline is known for its ability for complexation with different metals, which allows the adsorption of preliminarily prepared metal complexes on the carbon surface with subsequent formation of SACs.

Among the carbon-supported metal catalysts, Pd is most often mentioned. One of the early works devoted to N-modified carbons for the reactions of fine organic synthesis was reported by Li et al. [164], who prepared Pd@CN catalysts by the direct carbonization of Pd-NHC complexes ([TPBAIm][NTf2]3 with functional nitrile arms used) at a variety of carbonization conditions (400 °C or 800 °C). The sample Pd@CN800, containing as high as 24 wt.% of Pd in the form of NPs (12.3 ± 1.1 nm), revealed high activity and selectivity toward the domino carbonylative synthesis of pyrazole derivatives (isolated yields of up to 93% were achieved at 110 °C for 6 h) from aryl iodides, arylacetylenes, and phenyhydrazine and 1 atm pressure of CO gas.

N-modified carbons are also used in hydrochlorination processes [38,165,166]. The ex situ modification of AC by the nitration method was proposed by Xu et al. [38]. Thus, a sample of AC-NO2 was obtained, which was further reduced with sodium borohydride to AC-NH2 and then modified with pyridine (the sample AC-NHN). The modified carbons were used for the synthesis of Ru-based catalysts (1 wt.% of Ru) by the IWI method. The introduction of N-groups was found to result in a decrease in Ru dispersion in the following order: Ru/AC (80.58%) > Ru/AC-NO2 (68.04%) > Ru/AC-NH2 (51.17%) > Ru/AC-NHC (45.53%). At the same time, coke deposition in the reaction of acetylene hydrochlorination increased in the following order: Ru/AC-NHN (1.9%) < Ru/AC-NH2 (3.2%) < Ru/AC-NO2 (6.8%) < Ru/AC (13.2%). Moreover, the modification of carbon supports with N-groups enhances the adsorption of HCl and weakens the adsorption of vinyl chloride, which allows for higher catalytic activity.

Zhao et al. [165] obtained the Co-N-AC catalyst by the adsorption of 1,10-phenanthroline complexes with CoCl2 on the AC surface followed by calcination at 700 °C. Thus, the homogeneous atomic distribution of Co was achieved with cobalt atoms coordinated by nitrogen (Co-Nx). It was found that Co-N-AC possessed higher catalytic activity in acetylene hydrochlorination (180 °C, gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) = 36 h−1, V(HCl)/V(C2H2) = 1.15) in comparison with the Co-AC due to the improved ability for the adsorption of hydrogen chloride.

The N-doped AC was prepared by Qui et al. [166] using melamine as a nitrogen source by the adsorption of melamine on the AC surface (mass ratio of melamine to AC was 1:1) with further calcination (700 °C). Then, HgCl2 was deposited on the synthesized N-AC by the IWI method. HgCl2/N-AC (4 wt.% of HgCl2) was tested in acetylene hydrochlorination and demonstrated an initial acetylene conversion of 97.8% at 140 °C and GHSV = 30 h−1 (V(HCl)/V(C2H2) = 1:1.1), which was 2.3 times higher than that of commercial 6%-HgCl2/AC catalyst. It was proposed that HgCl2 molecules exhibit stronger adsorption on the surface vacancies, which causes an increase in catalyst stability. N-doping also facilitates the adsorption of HCl via hydrogen bonding. Thus, an HCl-rich microenvironment is formed around the HgCl2, providing the proximity of the adsorption sites for the two reactants and accelerating the reaction [166].

The hydrogenation of alkynes, e.g., phenylacetylene, is another industrially important reaction in which carbon-supported catalysts can be applied. This kind of reaction is typically catalyzed by palladium using molecular hydrogen. In the case of transfer hydrogenation of alkynes, palladium can be replaced with non-noble metals. In the work of Zhang et al. [167], Cu SAC was obtained using NC and synthesized by pyrolysis of melamine-formaldehyde resin. It is noteworthy that in the case of the Cu1/NC catalyst, common Cu–N3 and Cu–N4 structures were found, which disabled the transfer hydrogenation reaction. In contrast, the deposition of NC on the Al2O3 surface caused the decrease in coordinated N atoms (Cu–N2 structure), which, in turn, led to effective abstraction of hydrogen from ammonia–borane and adsorption of the alkyne substrate. Thus, in the presence of Cu1/NC/Al2O3, the hydrogenation of phenylacetylene proceeded with a 94% yield and 99% selectivity for 8 h in EtOH medium at 70 °C.

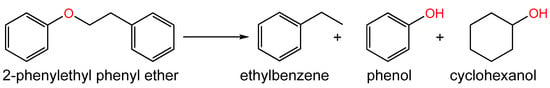

Wang et al. [168] proposed a two-step procedure of Ni catalyst synthesis, according to which an aqueous solution of melamine (N source), glucose (C source), and nickel acetate was dried and pyrolyzed at 600 °C (first step). Then, in the second step, the pyrolysis temperature was increased to 800 °C, 900 °C or 1000 °C. The obtained catalysts were tested in the hydrogenolysis of 2-phenylethyl phenyl ether (Figure 16), which is a common lignin β-O-4 dimeric model compound, in isopropanol medium at 200 °C and 1 MPa of H2. The sample of Ni@NC-800 (21.3 wt.% of Ni), with mean diameters of Ni-containing NPs of about 13.3 nm, possessed the highest catalytic activity (conversion of 2-phenylethyl phenyl ether reached 99.9% for 2 h), giving 93.9% yield of ethylbenzene and 86.0% yield of phenol. The Ni@NC-800 was also tested in lignin depolymerization at 240 °C and 1 MPa of H2 and resulted in the yield of the aromatic monomers of 21.3 wt.%, which was nearly double compared to Ni@C-800 (9.1 wt.%) [168].

Figure 16.

Scheme of hydrogenolysis of 2-phenylethyl phenyl ether.

3.3. S-Functionalized Carbons

Sulfur-doped carbons can be used for the development of metal sulfide catalysts for a wide range of catalytic applications, including oxidation [94,105,169] and hydrogenation [95,170,171] processes. The main field of application of sulfonated carbons is hydrolysis and esterification [97,98,99,100] as metal-free solid acid catalysts.

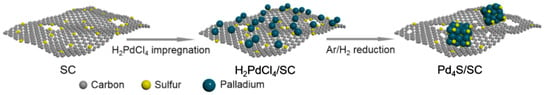

Among the S-doped carbon-supported catalysts, we would like to highlight the Pd- and Pt-containing catalysts for hydrogenation of nitroarenes [170,171]. Wu et al. [170] were the first to report the reactive MSI for carbon-supported catalysts. The S-doped carbon (SC) material was synthesized using 2,2′-bithiophene as a precursor. Then, palladium was deposited in the form of H2PdCl4 by adsorption from an aqueous solution with the following solvent evaporation and metal reduction at 300–700 °C (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

General scheme of the synthesis of Pd4S/SC catalyst based on reactive [170].

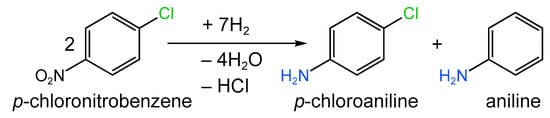

Depending on the reduction conditions, Pd-containing NPs were formed with sizes varying from 0.90 ± 0.24 nm for 5%-PdxS/SC-300 to 14.1 ± 6.2 nm for 5%-PdxS/SC-700. In the case of PdxS/SC-500 the average diameter of Pd NPs was about 6 nm irrespective of the metal loading (2–10 wt.%). The sample 5%-PdxS/SC-500, containing well-defined crystalline Pd4S NPs, exhibited the highest selectivity to p-chloroaniline (>99.9%) at complete conversion of p-chloronitrobenzene achieved for 1 h at 80 °C and 0.6 MPa of H2 (Figure 18). The catalyst 5%-PdxS/SC-500 was also tested in the hydrogenation of more than 20 different nitroarenes and revealed >98% selectivity at complete conversion [170].

Figure 18.

Scheme of p-chloronitrobenzene hydrogenation.

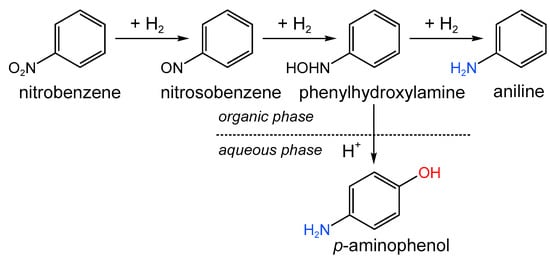

Luo et al. [171] used a simple procedure based on the adsorption of the source of sulfur (benzene sulfide) on the AC surface with the following thermal treatment. Platinum was deposited from an aqueous solution of H2PtCl6 by the IWI method. After reduction with sodium borohydride, small Pt NPs with sizes of about 2–3 nm were formed. Synthesized Pt/SC catalysts were tested in the reaction of hydrogenative rearrangement of nitrobenzene for the synthesis of p-aminophenol at 80 °C and 1 MPa of H2 (Figure 19). The increase in sulfur content was found to result in a decrease in catalytic activity and a corresponding increase in selectivity to p-aminophenol from about 60% to 65%, which was explained by the electronic effects (electron transfer from Pt to the S-doped AC).

Figure 19.

Scheme of hydrogenative rearrangement of nitrobenzene.

3.4. P-Functionalized Carbons

Similar to the above examples of O-, N-, and S-doped carbons, the catalysts supported on P-doped materials find application mainly in the hydrogenation of nitro-compounds and hydrochlorination of acetylene. The recent works describing HDC and dehydration reactions in the presence of metal-containing P-doped catalysts are also worth mentioning.

Thus, Lu et al. [172] developed the Pd/C-P-EG catalyst (containing 2 wt.% of palladium in the form of NPs with an average diameter of 8.7 nm) based on AC covered with a P-doped carbon layer, which was obtained by the calcination of sodium hypophosphite and ethanediol. The synthesized catalyst was tested in the reaction of p-chloronitrobenzene hydrogenation (Figure 18) under solvent-free conditions at 363 K and 1 MPa of hydrogen pressure and possessed >99.9% selectivity to p-chloroaniline at 100% of the substrate conversion along with high stability (for five consecutive runs). The superior catalytic properties of Pd/C-P-EG were attributed to its electronic effects, i.e., the electron donation from C to Pd via P atoms. As a result, Pd NPs supported on C-P-EG revealed nucleophilic properties and allowed the formation of electron-rich hydrogen (H-), which preferably attacked the nitro group rather than the C–Cl bond.

In the work of Wang et al. [91], P-doped carbon material was obtained by the adsorption of TPP on spherical AC and then calcined for 1 h at a temperature ranging from 600 °C to 800 °C. The Au-containing catalysts were prepared by the IWI method and tested in a reaction of acetylene hydrochlorination. Au-containing NPs deposited on the P-doped spherical AC (Au content was 20 wt.%) allowed for high acetylene conversion (99.9% for 23 h on stream at 170 °C and GHSV of 360 h−1) and 100% selectivity with respect to vinyl chloride. It was shown that P-groups, i.e., (PO4)3− and (PO3)−, can interact with the catalytically active ions Au3+ and Au1+, providing better dispersion and preventing their reduction to Au0. P-doping was also found to decrease coke formation, ensuring high stability of the developed catalysts [91].

Liu et al. [173] used P-doped cotton stalk carbon materials (PCBC) with hierarchical porosity as supports for Pd catalysts of acetylene hydrochlorination. Catalysts containing 0.5 wt.% of Pd were synthesized by the ultrasonic-assisted impregnation method from the solution of PdCl2. The catalyst Pd/CBC possessed low activity in the hydrochlorination reaction (acetylene conversion was about 27.5%) at 160 °C, GHSV = 120 h−1, V(HCl)/V(C2H2) = 1.25. In the case of the Pd/PCBC samples, the increase in the concentration of H3PO4 during the support preparation from 1.07 mol/L to 5.35 mol/L resulted in a corresponding increase in catalytic activity. Thus, Pd/P5CBC (H3PO4 5.35 mol/L) allowed for an acetylene conversion of 99.9%, 99.3% selectivity to vinyl chloride, and high stability for about 5 h due to lower carbon deposition.

The reaction of chlorodifluoromethane HDC was carried out by Zheng et al. [92] at a temperature of 450 °C and ambient pressure in the presence of 5%Ni/P-C catalyst. The P-doped carbon was obtained by the direct combustion of phytic acid under microwave irradiation and used as the support for Ni-containing NPs (mainly NiO, and also Ni(OH)2). NiO NPs were highly adhesive to the P-C surface, which allowed the sizes of NiO NPs to decrease 2–3 times compared with 5%Ni/C.

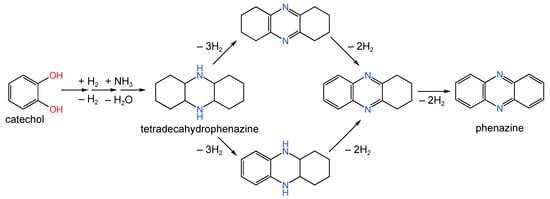

P-doped carbon materials with high SSA (∼2300 m2/g) were developed by Konovalova et al. [174] using pine nut shell (PNS) as the raw material. The series of catalysts was synthesized by the adsorption precipitation technique described by Shivtsov et al. [175]. The sample Pd/PNS was also treated in a hydrogen flow at 700 °C (designated as Pd/PNS-700). Both the Pd/PNS and Pd/PNS-700 samples contained about 10.4 wt.% of Pd in the form of Pd NPs with mean diameters of 4.5–5.5 nm. It was shown that the residual phosphorus in the PNS had a significant effect on the catalytic activity of supported Pd in the reaction of hydrogenation/dehydrogenation of heterocyclic compounds (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Simplified scheme of the synthesis of tetradecahydrophenazine and phenazine, involving the stages of hydrogenation/dehydrogenation and amination-cyclization.

Phosphorus in low oxidation states is able to interact with Pd up to the formation of palladium phosphides. In contrast, the highest oxidation state of phosphorus caused slight modification of Pd NPs. Thus, in order to provide the highest catalytic activity, only partial modification of Pd by phosphorus is necessary, which was achieved in the case of the Pd/PNS-700 sample, while the complete absence of phosphorus led to a decrease in catalytic activity [174].

3.5. B-Functionalized Carbons

B-doped carbon materials can serve as metal-free catalysts. For example, Lin et al. [176] reported the application of B-doped onion-like carbon and CNTs as metal-free catalysts, exhibiting high catalytic activity and stability in the reduction of nitroarenes under stoichiometric amounts of N2H4. However, there are several examples describing the use of B-doped carbons as the supports for metal species.

Liu et al. [109] synthesized Pd-containing catalysts supported on B-doped porous carbon (Pd/BPC) for the dehydrogenation of formic acid. BPC was obtained by a two-step procedure involving the preparation of porous carbon (PC) by a template-assisted method (using γ-Fe2O3 NPs as a template soluble in acid medium) and subsequently treated with boric acid. Palladium was deposited by adsorption of Pd(OAc)2 from a MeOH solution and further reduction.

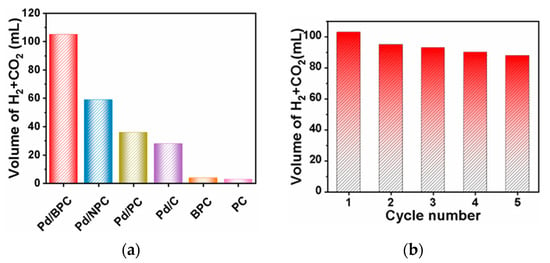

It is noteworthy that, as compared to AC, PC, and N-doped PC (NPC), BPC offers unique advantages for supporting Pd NPs due to its highly ordered mesoporous structure, providing efficient reactant diffusion [177]. B-doping also influences the electronic properties of Pd NPs, which leads to improved adsorption and activation of reactant molecules [178]. As a result of the study [109], it was found that Pd/BPC allowed for noticeably higher activity in the dehydrogenation of formic acid compared with other catalytic materials (Figure 21a) at 50 °C for 90 min. In addition, Pd/BPC revealed good stability for five consecutive runs (Figure 21b) [109].

Figure 21.

Comparison of the catalytic performance in formic acid dehydrogenation over Pd/BPC, Pd/NPC, Pd/PC, Pd/C, BPC, and PC (a) and the recyclability of Pd/BPC (b) [109].

In the work of Zhu et al. [179], an acetylene acetoxylation reaction (220 °C, V(C2H2)/V[CH3COOH(g)] = 3) was carried out using Zn-containing B-doped AC catalysts (7.3 wt.% of Zn) synthesized by the IWI method. Boric acid was the source of boron atoms. It was demonstrated that B-AC, as a support, resulted in an increase in the conversion rate of CH3COOH from 50% to 65%, which was likely due to the enhancement of the adsorption ability of CH3COOH along with the reduction in the adsorption of C2H2. In addition, the electronic effects took place, namely the strengthening of the Zn–O (from CH3COOH) bond. The distribution of zinc acetate on the support surface was also improved by the B-doping. Nevertheless, the activity of the optimal catalyst Zn/0.02 B-AC-900 (0.02 refers to the weight ratio of boric acid to the AC; 900 corresponds to the annealing temperature) decreased over time, i.e., after 320 h of reaction, the conversion of acetic acid dropped by 15% due to coke deposition.

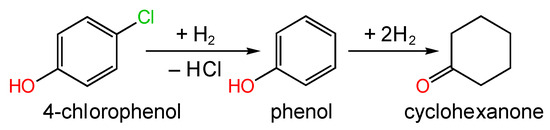

Pd NPs immobilized on the B-doped ordered MC (BOMC) for the HDC of 4-chlorophenol using formic acid as the hydrogen source were synthesized by Li et al. [180]. BOMC was obtained via the one-step HTC method using boric acid (boron source) and resorcinol/hexamethylenetetramine (carbon source) by self-assembly with Pluronic F127 in aqueous solutions. Thus, the BOMC material was doped not only with boron but also with nitrogen atoms. The series of Pd-containing catalysts (1 wt.% of Pd) was prepared by the impregnation of AC, OMC, or BOMC with an aqueous solution of H2PdCl4 with the followed by reduction with NaBH4. Pd@AC and Pd@OMC allowed for 100% conversion of 4-chlorophenol for 0.5 h at 306 K and complete selectivity to phenol (Figure 22), while Pd@BOMC favored the formation of cyclohexanone (12%).

Figure 22.

Scheme of HDC reaction of 4-chlorophenol.

The higher activity of Pd@BOMC compared with the other samples was attributed to the better dispersion of Pd NPs (about 3 nm in diameter). Importantly, Pd@BOMC revealed exceptional stability (100% conversion of 4-chlorophenol was achieved for seven repeated runs) in comparison with Pd@AC and Pd@OMC, which showed a rapid drop in conversion from 100% to about 40% and 70%, respectively, at the second run. This is likely due to the synergistic effect between the stabilized Pd NPs and the mesoporous structure of the B-doped support [180].

4. Doped Graphenes, CNTs, and g-C3N4 as Supports

Graphenes and CNTs are materials well-known for several decades in the fields of gas separation [181], adsorption [182], and catalysis. The catalytic application of graphenes and CNTs mainly involves electrocatalysis, e.g., CO2 reduction [183,184], oxygen reduction [185,186], hydrogen evolution reaction [187], water-splitting [188], etc. CNTs are known as materials for hydrogen adsorption, and the strong MSI in the case of CNTs may facilitate the spilling over of hydrogen atoms from metal NPs to the defect sites of CNTs, which strongly adsorb hydrogen atoms [189].

Graphenes and CNTs can be doped/functionalized with different heteroatoms and groups, among which the O- and N-groups are the most widely used. Similarly to the catalysts supported on ACs, functionalization with surface oxygen groups allows for the improvement in catalytic activity by suppressing aggregation and enhancing the dispersion of catalytically active particles [190]. In electrocatalytic reactions, carboxyl groups facilitate proton transport [184]. Moreover, carboxyl groups can serve as sites for the grafting of organic ligands, e.g., porphyrins [191], and for the coordination of metal catalysts, thus enhancing catalytic efficiency (activity and stability). N-doping, especially the pyridinic N, also improves metal dispersion due to the electronic MSI. Additionally, pyridinic nitrogen facilitates the reduction of metal cations that can increase catalytic activity [192].

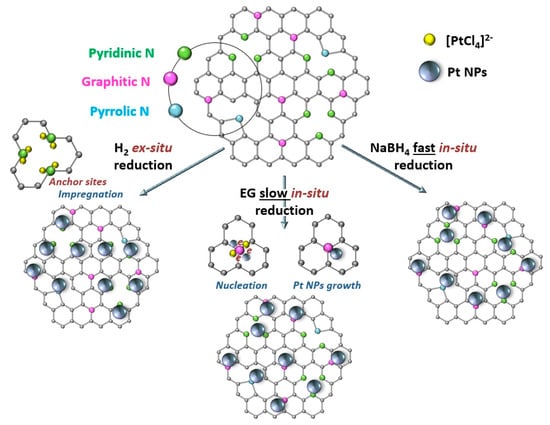

Regarding the formation of metallic NPs, it is noteworthy that, depending on the reduction method, the electronic properties of metal NPs may change [193] due to the different mechanisms of metal NP formation and the different electron donation-acceptance between metal atoms and graphitic/pyridinic nitrogen. For example, during the slow reduction of [PtCl6]2−, deposited on the surface of N-doped graphene by the EG method, the Pt nuclei first form and then gradually grow to NPs. An electron-enriched environment promotes metal reduction; hence, Pt NPs preferably occupy the graphitic N-sites. When NaBH4 is used as a reductant, quick formation and random deposition of Pt NPs occur, with weak and non-selective interaction with both the graphitic and pyridinic N-sites. In the case of two-step treatment involving the impregnation of H2[PtCl6] followed by ex situ reduction with molecular H2, vacancies containing pyridinic nitrogen favor the adsorption of charged metal ions, leading to the strong interaction between Pt NPs and the support (Figure 23).

Figure 23.

Schematic mechanism of interaction between Pt NPs and NCNTs in different synthesis strategies [193].

Thus, for the series of Pt/NCNTs catalysts, the Pt electronic structure was influenced by the reduction method, and the binding energy (BE) of Pt 4f7/2 decreased in the following order: Pt/NCNTs (H2) > Pt/NCNTs (EG) > Pt/NCNTs (NaBH4) [193].

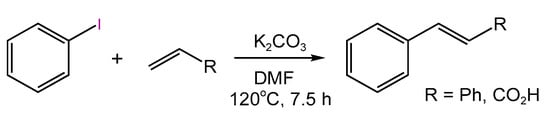

In fine organic synthesis, Pd deposited on CNTs is the most widely used catalytic system [194,195], demonstrating promising activity and selectivity in various Pd-catalyzed reactions and, in particular, in the cross-coupling processes. For such reactions as C–C coupling, the homogeneous mechanism is postulated. Thus, the migration and leaching of Pd species is a tremendous factor defining the stability of catalytic systems. In the work of Ligi et al. [196], grafting of phosphine and phosphine oxide derivatives on CNTs allowed for high stability of anchored Pd NPs in the Heck reaction between 4-iodoanisole and styrene (Figure 24) for at least three consecutive runs [196].

Figure 24.

Scheme of Heck reaction between 4-iodoanisole and sytrene.

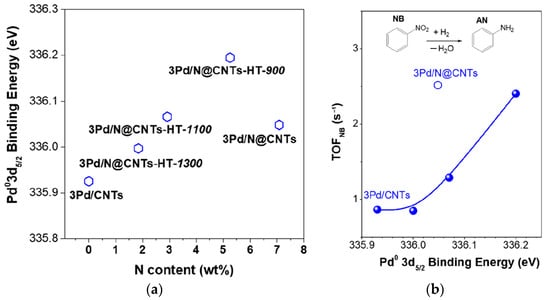

Doped CNTs are promising supports for hydrogenation catalysts. He et al. [197] synthesized N@CNTs materials by the chemical vapor deposition of pyridine on the surface of CNTs. To alter the nitrogen content, postheat treatment was carried out at 900, 1100, or 1300 °C. Pd NPs with diameters of about 2 to 3 nm were formed by the adsorption of H2PdCl4 from aqueous solution on the N@CNTs and then treated with NaBH4. It was observed that the increase in Pd content from 0 to 1.65 wt.% results in a decrease in the ratio of pyridinic nitrogen to the graphitic one from 0.76 to 0.59, which was due to the preferential occupation of pyridinic N sites by Pd. A further increase in Pd loading caused a slight increase in this ratio, since Pd NPs started to occupy the graphitic N also [197]. The electron donation from Pd to N led to an almost linear increase in Pd0 3d5/2 BE (Figure 25a) but notin the case of Pd/N@CNTs sample (without the heat treatment), which was likely due to the more defective structure of N@CNTs in comparison with the annealed samples. The synthesized catalysts containing 1.9–2.5 wt.% of Pd were tested in the reaction of nitrobenzene hydrogenation in EtOH medium at 318 K and 0.5 MPa of H2.

Figure 25.

Effects of the N content of N@CNTs on Pd0 3d5/2 BE (a) and the dependence of the TOF of nitrobenzene hydrogenation on Pd0 3d5/2 BE (b). Reproduced with permission from authors of [197], ACS, 2019.

It was revealed that catalytic activity (TOF) directly depended on the BE of Pd0 3d5/2 (Figure 25b), indicating that the electron deficiency of Pd is beneficial for nitrobenzene hydrogenation due to the strong adsorption of nitro-groups on electron-deficient Pd NPs. Thus, the catalytic activity was shown to be tuned by the electronic MSI [197].

Another interesting work was published by Wang et al. [198], who proposed the use of commercial FCNTs as the starting material, which underwent defluorination and single/dual-elemental doping with controllable contents of N, S, and P. Palladium was deposited on the doped CNTs by the adsorption of Pd(OAc)2 from an aqueous solution of acetic acid and then reduced by NaBH4, allowing small Pd NPs (2–3 nm) anchored on the CNTs’ surface to be obtained. The resulting catalytic systems were tested in the reaction of phenol hydrogenation in a water medium at 80 °C and 1.1 atm of H2 and revealed high activity (100% conversion was reached for 12 h) and 100% selectivity to cyclohexanone. Similar to the work of He et al. [197], the electron-deficient Pd NPs were shown to be beneficial for the selective hydrogenation of phenol regardless of the type of heteroatom (N, P, and S) and doping configuration (single- and dual-doping). It was found that the increase in BE of Pd 3d5/2 from 335.7 eV to 336.1 eV results in a doubling in TOF, from about 70 h−1 to 140 h−1 [198]. Thus, it was proposed that the BE of Pd 3d5/2 can serve as one of the descriptors while estimating catalytic performance and can be used for targeted catalyst design.

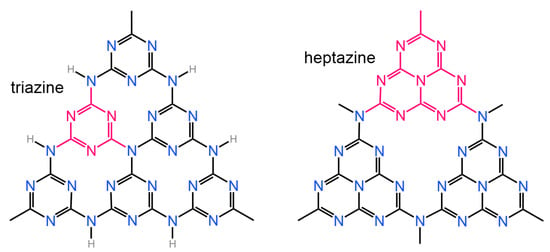

In this review we would like to pay attention to the g-C3N4 material, the application of which in sensing, separation, and catalysis is an emerging field. Graphitic carbon nitride is produced by the thermal decomposition of melamine [199]. As a support for metals, g-C3N4 is used in different electrocatalytic processes [200,201], including CO2 hydrogenation [202,203,204,205], in which it possesses superior properties as compared to CNTs. However, the main application of graphitic carbon nitride is photocatalysis. The high photocatalytic reactivity of g-C3N4 is due to its structure, in which electron pairs of sp2 hybridized carbon and nitrogen atoms form a delocalized π-conjugated network [206]. Two distinct structures (heptazine and triazine) were identified as the building blocks of g-C3N4 (Figure 26), among which the triazine structure is the most stable [206].

Figure 26.

Triazine (left) and heptazine (right) structural units of g-C3N4 [206].

Recently, there have been numerous reviews and research papers have focused on the photocatalytic properties of g-C3N4 [206,207,208,209,210,211,212]; hence, we will not consider photocatalysis in the current review. The only fact we would like to emphasize is that the most exciting results from recent years were achieved in the cross-coupling reactions of C–C and C–N [213,214,215,216,217]. As was already mentioned, the main issue of cross-coupling reactions is metal leaching and continuous change in catalyst morphology in the case of ligand-free catalytic systems. Thus, homogeneous metal complexes are still recognized as industrial catalysts despite the known drawbacks of such systems. The catalysts supported on g-C3N4 were found to surpass the commercial homogeneous cross-coupling catalyst in terms of catalytic activity, even for the challenging chloroarenes, and possess promising recyclability due to the excellent ability of g-C3N4 to retain metal ions and atoms. In addition, the photocatalysts based on g-C3N4 are simple to prepare and can act even under visible light irradiation [213,214,215,216,217].

Graphitic carbon nitride can be an effective catalyst even in the absence of irradiation. Recently, Xing et al. [218] reported that the Pd/g-C3N4 catalyst, exhibiting high activity (TOF = 21,852 h−1) and stability (at least for six cycles) in the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction, which was carried out in the Pickering droplets reactor stabilized by Pd/g-C3N4 at the substrate-water interface. However, outside the field of photocatalysis, the majority of examples of the use of g-C3N4-supported catalysts concern hydrogenation reactions. For example, the catalyst Pd-CNNS/rGO20 (where CNNS is g-C3N4 nanosheets; 20 refers to the weight ratio of CNNS and GO—80:20) containing small Pd NPs of 1.31 nm in diameter was used for the transfer hydrogenation of nitro-compounds by employing formic acid as the hydrogen donor [219]. Various nitro-compounds were transformed into corresponding aromatic amines with good yield under mild conditions (25 °C, solvent—EtOH-water mixture (1:1), formic acid—hydrogen source), i.e., p-nitroanisole reached 87% conversion and 99% selectivity after 30 min. Moreover, synthesized catalysts revealed excellent stability; no significant loss in activity was found after the fifth run, though the sizes of Pd NPs increased up to 2.24 nm. It is noteworthy that Pd0 3d5/2 BE was equal to 336.2 eV [219], indicating the electron donation from Pd to N (electronic MSI).

Hu et al. [220] synthesized low metal-loaded Pd1/C3N4 (0.18 wt.% of Pd) SAC by confining the Pd atoms into the six-fold N-coordinating cavities of g-C3N4, which revealed exceptional catalytic activity in the hydrogenation of styrene (98% conversion for 1.5 h) and furfural (99% selectivity at 64% conversion for 4 h) and HDC of 4-chlorophenol (99% selectivity at 99% conversion for 10 min). The catalyst Pd1/C3N4 also exhibited high stability for at least five runs.

Cao et al. [221] proposed the Ru/g-C3N4 obtained by the IWI method and containing Ru NPs with a diameter of about 2.5 nm for the selective hydrogenation of p-phenylenediamine to 1,4-cyclohexanediamine under mild conditions (THF, 130 °C, 5 MPa of H2). Conversion of 100% with >86% selectivity was achieved for 2.5 h. The catalyst 5%Ru/g-C3N4 demonstrated a gradual decrease in activity for five consecutive runs, which was attributed to the aggregation of Ru NPs up to about 3.9 nm. It was proposed that the g-C3N4 possessed abundant basic sites, resulting in suitable basicity for the aromatic ring hydrogenation [221]. The Ru-, Ni-, and Pd-containing catalysts supported on g-C3N4 were obtained by Mishra et al. [222] and tested in the hydrogenation reaction of α-keto amide. High activity (100% conversion) and 98% selectivity with respect to β-aminol were achieved in the presence of Ru-g-C3N4.

Recently, bimetallic AgCu–C3N4 SAC (9 wt.% of Ag and 12 wt.% of Cu) was synthesized by Song et al. [223] for the semi-hydrogenation of alkynes by ammonia–borane complex (NH3 ∙ BH3). In the model reaction of 4-ethynylanisole hydrogenation, high selectivity and conversion (>99%) at room temperature for 20 h were found. Ag SAC was likely responsible for hydrogen activation, while Cu SAC for alkyne activation.

Among other examples of the successful application of g-C3N4-supported catalysts, hydrogenation of benzaldehyde to benzyl alcohol with a yield of about 99% [224] and Wacker oxidation of a wide range of olefins to the corresponding ketone compounds with a maximum yield as high as 94% [225] in the presence of Pd-loaded g-C3N4 are worth mentioning.

5. Carbon Supports Derived from MOFs and Other Polymers

The carbonization of polymers has proven to be an effective method of producing carbon materials with a well-defined morphology and structure. Carbon materials obtained from polymers are widely used in the production of electrodes, batteries, and adsorbents for gases and different pollutants [226,227]. Carbon materials synthesized from microporous organic polymers [228], N-containing polymers [229], biological coordination polymers [230], and hyper-cross-linked polymers [231] are known.

Carbons obtained from polymers find application in catalysis. For example, fine and mesoporous carbon, containing Fe and N species, was synthesized by multi-step pyrolysis of the self-assembled cross-linked polyimide film and used in the oxygen reduction reaction [232]. A bimetallic catalyst for the photothermal dry reforming of methane can be obtained by the carbonization of MOF structure (NixMoy-MOF/Al2O3) [233]. In the field of catalysis for fine organic synthesis, the majority of catalytic systems are MOFs-based carbon materials [234,235,236,237].

In the work of Dong et al. [234], magnetic porous carbon (MPC) was used as a support for Au and Pd NPs. MPC was synthesized by the calcination of Fe-MIL-88A at 700 °C under nitrogen. Au/MPC (3.93 wt.% of Au; Dm (Au NPs)~5–8 nm) was obtained by the adsorption of HAuCl4 from aqueous solution and followed by reduction with NaBH4. Similarly, Pd/MPC (5.11 wt.% of Pd; Dm (Pd NPs)~5 nm) was synthesized using the formaldehyde reduction method [235]. Au/MPC and Pd/MPC were highly active in the reduction of 4-nitrophenol with NaBH4 and in HDC of 4-chloronitrophenol. In the case of the HDC reaction catalyzed by Pd/MPC, the yield of phenol varied from 5% to 99.9%, depending on the base (NaOH, Na2CO3, CH3COONa, NH3.H2O, (C2H5)3N) and solvent (C2H5OH, CH3COOC2H5, DMF, H2O). ICP-AES showed that after the six repeated runs in the reaction of 4-nitrophenol reduction, the metal content in Au/MPC and Pd/MPC decreased to 3.76 wt.% and 4.92 wt.%, respectively [234].

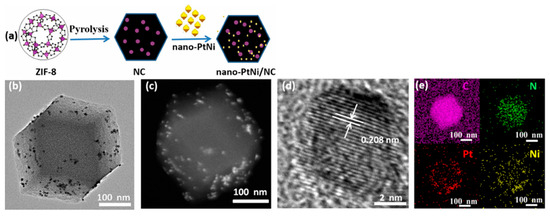

Wen et al. [236] reported the nano-PtNi/NC catalysts for the hydrosilylation of 1-octene. NC support was synthesized by carbonization of ZIF-8 at 600, 800, 900, and 1000 °C. Pt and Ni NPs, having a uniform octahedral shape and a mean diameter of 6.5 nm, were prepared by a solvothermal method and loaded on the NC supports (Figure 27).

Figure 27.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of nano-PtNi/NC (a). TEM (b) and HAADF-STEM (c) images of nano-PtNi/NC. HRTEM image (d) of the lattice fringe of the PtNi particle in nano-PtNi/NC. EDX elemental maps (e) of nano-PtNi/NC, C (pink), N (green), Pt (red), and Ni (yellow). Reproduced with permission from [236], Springer Nature, 2019.

Veerakumar et al. [238] developed Ru NPs with a mean diameter of 5.0 ± 0.2 nm supported on plastic-derived carbons (PDCs) obtained from plastic bottle wastes. Ru@PDC (4.01 wt.% of Ru) was tested in the reduction of potassium hexacyanoferrate(III) and new fuchsin dye by NaBH4 under mild conditions. The catalyst was stable and effective for more than six runs, with a conversion efficiency of ∼98%.

6. Discussion

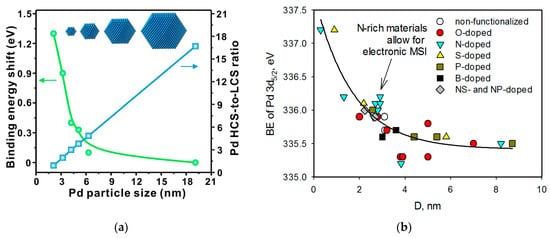

Despite the huge variety of catalytic systems supported on doped carbon materials, we tried to find any correlations across the presented experimental data. We chose palladium for the discussion because it is the most abundant metal catalyst. While discussing the series of samples presented in the above-cited works, we found examples of straight correlations between dopant content and the sizes of Pd NPs. However, we were not able to find a dependency that would fit all the data for the different catalysts. This may be due not only to the variety of carbon supports and heteroatom dopants but also to different methods of catalyst preparation and post-treatments (e.g., reduction conditions). We were also curious to find any general electronic MSI effects for all the Pd-containing catalytic systems. Thus, the data on the sizes of Pd NPs and the BEs of Pd 3d5/2 sublevels (XPS data) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Influence of carbon modification on the sizes and electronic properties of Pd particles.

It is known that the lower the NP sizes, the higher the electron BE values (Figure 28a). The same type of dependence can be found in the data presented in Table 1 (Figure 28b), which shows the absence of electronic MSIs in the majority of cases when Pd NPs with the diameters of about 3 nm were formed. As seen in Figure 28b, only a few data for the N-doped carbon materials provide evidence of electronic MSIs, e.g., the increase in BE of Pd 3d5/2 above its average value. Note that, to prove the electronic MSI, a corresponding negative shift in BE for carbon or heteroatom should be found.

Figure 28.

Dependences of the BE shift (a) [239] and of the values of BE of Pd 3d5/2 (b) on the sizes of palladium particles.

This means that for each individual reaction and catalytic system, the effects of carbon modification/doping can be different; not only should the decrease in the mean diameters of metal NPs and electron transfer be considered, but also changes in surface acidity and hydrophobicity, the reducibility of deposited metals, and the catalyst deactivation rate. In this regard, while working with such diverse data for complex multiparametric systems, machine learning approaches [240,241,242] may be the next step in the search for the most efficient carbon-supported catalyst for the reaction of interest.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Carbon-based materials find application in different metal-catalyzed processes. Modification of carbons with functional groups or heteroatoms (O, N, S, P, B) is an effective tool that provides a number of beneficial metal catalyst properties supported on functionalized/doped carbon materials:

- (i)

- Decrease in the mean diameters of metal NPs and an increase in their dispersion;

- (ii)

- Better uniformity of metal distribution on the support surface;

- (iii)

- Stabilization of single-atom state in the case of SACs;

- (iv)

- Increase in metal reducibility;

- (v)

- Formation of compounds from metals and heteroatoms (reactive MSI), i.e., the formation of metal sulfide NPs in the case of the S-doped carbon supports;

- (vi)

- Formation of reactive acid/base sites on the support surface, which may act in tandem with the metal active species;

- (vii)

- Tuning of the adsorption ability of the reactants on the catalyst surface by the regulation of its polarity and electronic properties, which may enhance catalytic activity and stability;

- (viii)

- Possibility to create separable and reusable homogeneous catalysts by grafting ligands on the surface of carbon supports.

Metal-containing carbon materials are mainly used in various electrochemical processes, including the reduction of gases (O2, COx, NOx), hydrogen production, and the separation of hydrogen from gas mixtures. An important reaction that can benefit from the use of functionalized carbon supports is Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. In this review, we paid attention to the reactions of fine organic synthesis to determine if there was any progress in this field in terms of the use of carbon-supported metal catalysts.

Although there are plenty of publications describing the application of carbon-supported catalysts, there are still limited examples of works discussing the effects of MSI. Among these, hydrogenation reactions can be underscored, e.g., selective hydrogenation of triple C–C bonds, hydrogenation of levulinic acid to gamma-valerolactone, and hydrogenation of nitroarenes and phenols. Other reactions, which were discussed in this review, include hydrogenolysis, oxidation, and cross-coupling.