Abstract

The excessive use of tetracycline (TC) poses a severe threat to the health of humans and ecosystems. Environmentally friendly photocatalytic technology can be effectively used to degrade TC. In this study, an Fe-modified UIO-66 (Fe/UIO-66) catalyst was prepared via a solvothermal method. The structural and optical properties were investigated to elucidate how the electronic interaction between Fe and UIO-66 influenced the light absorption capacity of Fe/UIO-66. A xenon lamp was used to simulate sunlight, and TC was taken as the target pollutant. The results of photocatalytic experiments showed that the degradation efficiency of Fe/UIO-66 for TC reached 80% within 120 min, superior to that of UIO-66. In addition, the experiment also investigated the influence of inorganic salt ions on the catalytic performance, proving that Fe/UIO-66 could be applied for the efficient removal of TC in complex water bodies.

1. Introduction

Currently, global antibiotic pollution poses a severe threat to ecological security and human health. Tetracycline (TC) is widely used in medicine, animal husbandry, and aquaculture. TC residues containing nitrogen enter soil and water bodies through pathways such as excreta and industrial wastewater, leading to issues including microbial imbalance in ecosystems, toxic effects on aquatic organisms, and the development of antibiotic resistance [1,2,3]. Traditional methods for removing TC include physical adsorption [4], chemical oxidation [5], and biodegradation technologies [6]. However, physical adsorption only achieves the transfer of pollutants, which may cause secondary pollution and makes it difficult to completely eliminate TC. Chemical oxidation suffers from two major drawbacks: significant operational costs from the consumption of large quantities of reagents and the potential formation of hazardous by-products. Biodegradation has a long treatment cycle and low efficiency. Faced with multiple dilemmas of traditional treatment technologies, such as high cost, low efficiency, and high potential risks, there is an urgent need to develop a new type of TC treatment technology that is both efficient and environmentally friendly.

Photocatalytic technology driven by solar energy has stood out prominently. Catalysts absorb light energy to generate highly reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can deeply mineralize TC into carbon dioxide and water. Compared with traditional methods, photocatalytic technology exhibits significant potential in terms of the mildness of reaction conditions, environmental friendliness, sustainability, and pollutant mineralization capacity [7,8,9,10]. However, conventional photocatalysts suffer from drawbacks such as a low specific surface area, narrow light absorption range, and high electron–hole recombination rate, making the development of efficient and novel photocatalytic materials an urgent task.

UIO-66 exhibits unique potential in the field of photocatalysis due to its high specific surface area, tunable pore structure, and excellent chemical stability. Its core structure consists of Zr metal clusters and terephthalic acid ligands, and its photocatalytic performance can be optimized through metal node doping or ligand modification [11]. Iron (Fe) and iron-based materials have become a preferred choice for UIO-66 modification, owing to its low cost, easy availability, and high electron transfer efficiency [12,13,14]. Fe doping can adjust the band structure of the material and expand the visible light absorption range. Zhou et al. [15] loaded Fe onto UIO-66 via an atomic layer deposition (ALD) process, and photocatalytic experiments confirmed that the introduction of Fe enhanced the photocatalytic degradation performance. However, the atomic layer deposition process is associated with high cost and long cycle time.

In this study, the Fe-modified UIO-66 catalyst (Fe/UIO-66) was prepared via a solvothermal method that features simple operation and low cost. The effects of factors such as catalyst concentration, initial TC concentration, and other anions and cations were investigated emphatically. The influence of electronic interaction between Fe and UIO-66 on the enhancement of photocatalytic performance was clarified, providing theoretical and technical support for the treatment of antibiotics.

2. Experiment

2.1. Reagents

Zirconium chloride, potassium sulfate, tetracycline hydrochloride, and iron (III) nitrate nonahydrate came from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Terephthalic acid, anhydrous methanol, and N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Acetic acid was supplied by Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All of the chemicals were used without any further purification.

2.2. Preparation of UIO-66 Photocatalyst

UIO-66 was synthesized according to the method reported in the literature [16]; 1.5 g of zirconium (IV) chloride and 1.1 g of terephthalic acid were added into a 250 mL round-bottomed flask. Then, 100 mL of DMF, 44 mL of acetic acid, and 7.5 mL of pure water were added. Sequentially, the solution was heated to 120 °C for 30 min. The product was collected by centrifugation after the solution cooled to room temperature, then washed repeatedly with DMF and anhydrous methanol and dried at 80 °C for 3 h to obtain the UIO-66 catalyst.

2.3. Preparation of Fe/UIO-66 Photocatalyst

A total of 400 mg of iron (III) nitrate nonahydrate was added to the aforementioned solution, and the mixture was stirred to ensure complete dissolution. The above steps were repeated to obtain the Fe-modified UIO-66 catalyst, denoted as Fe/UIO-66.

2.4. Characterization of the Photocatalyst

The phase composition of the catalyst was analyzed using a powder X-ray diffractometer (Smartlab 9 KW, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). The types of functional groups in the catalyst were characterized by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR VERTEX 70, Bruker, Bremen, Germany). The morphology and elemental composition of the catalyst were examined via a scanning electron microscope (SEM SU8600, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The light absorption capacity of the catalyst was analyzed using a UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer (JASCO V-770, Hachioji, Japan).

2.5. Performance Evaluation of the Photocatalyst

A total of 30 mg of the catalyst was added into a reactor, followed by the addition of 50 mL of TC solution with a concentration of 40 mg/L. After 30 min of dark adsorption, the reactor was placed under a xenon lamp (λ = 400 nm). Samples were collected at 20 min intervals, and the photocatalytic degradation efficiency was assessed based on the measured absorbance values. The absorbance of TC solutions with different concentrations was measured separately at a wavelength of 360 nm, yielding a standard curve as shown in Figure S1.

3. Results and Discussion

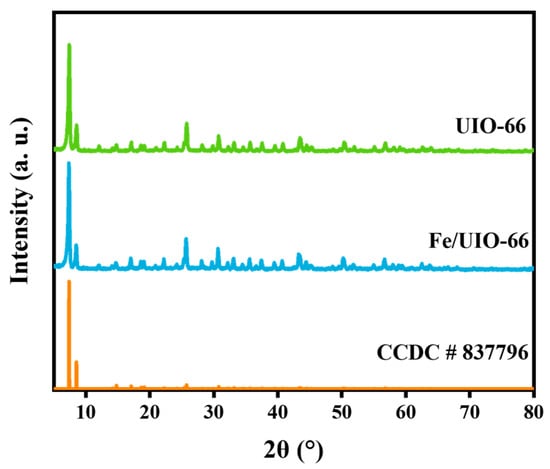

3.1. XRD Analysis

The XRD patterns of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 are shown in Figure 1. Both UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 exhibit sharp characteristic peaks, which confirms that both materials possess good crystallinity. UIO-66 shows characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 7.42°, 8.54°, 17.14°, 25.78°, and 30.74°, which are basically consistent with the previous report [17], indicating the successful preparation of UIO-66. Compared to UIO-66, no obvious change can be observed in Fe/UIO-66, suggesting that the introduction of Fe does not change the crystal structure of UIO-66. However, no obvious Fe characteristic peaks are observed in the XRD pattern of Fe/UIO-66, which may be due to the low content of Fe or the amorphous state of the introduced Fe [18].

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66.

3.2. FTIR Analysis

As shown in Figure S2, the absorption peak at 1666 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum of UIO-66 is attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of the C=O bond. The absorption peaks at 1587 cm−1 and 1396 cm−1 are assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations in the O=C-O bond in terephthalic acid, respectively. The absorption peak at 1506 cm−1 corresponds to the vibration of the C=C bond in the benzene ring skeleton. The absorption peaks at 1156 cm−1, 1017 cm−1, 744 cm−1, and 667 cm−1 are the vibrational absorption peaks of the O-H bond and C-H bond in terephthalic acid, and the absorption peak around 555 cm−1 is attributed to the vibrational absorption of Zr-(OC) [19,20,21]. The absorption peaks of Fe/UIO-66 and UIO-66 are extremely similar, indicating that Fe does not change the intrinsic functional groups of UIO-66.

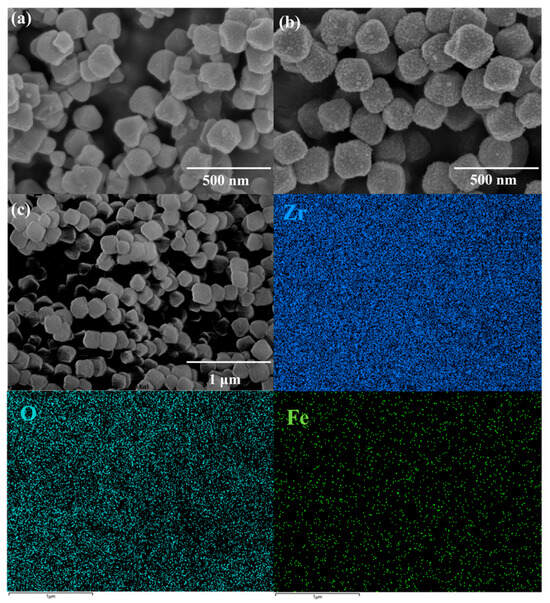

3.3. SEM Analysis

The SEM images of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 are shown in Figure 2. As can be seen from Figure 2a, UIO-66 exhibits a relatively regular octahedral structure with a low degree of roughness. It can be observed from Figure 2b that Fe/UIO-66 also has an octahedral structure, which indicates that the introduction of Fe does not cause obvious morphological changes. However, the surface of Fe/UIO-66 is rougher than that of UIO-66, suggesting that there may be a significant interaction between Fe and UIO-66. Figure 2c contains the elemental mapping images of Fe/UIO-66, which show the uniform distribution of Zr, O, and Fe elements in Fe/UIO-66 and confirm the successful introduction of Fe into UIO-66.

Figure 2.

(a) SEM images of UIO-66; (b) SEM images; and (c) elemental mapping images of Fe/UIO-66.

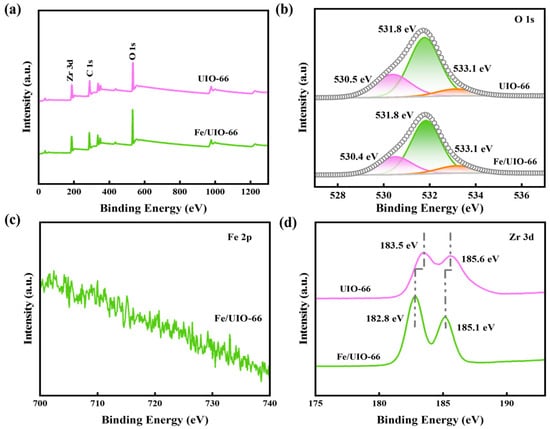

3.4. XPS Analysis

The XPS survey spectra and high-resolution spectra of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 are shown in Figure 3. The survey spectra in Figure 3a confirms the presence of C, O, and Zr elements in both UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66. In the high-resolution O 1s spectra (Figure 3b), the peaks with binding energies of 530.4 eV, 531.8 eV, and 533.1 eV are assigned to Zr-O, -OH, and O-C=O, respectively [22]. Although no obvious signals are observed in the high-resolution Fe 2p spectrum of Fe/UIO-66 (Figure 3c), the binding energy shift in the high-resolution Zr 3d spectra (Figure 3d) confirms the existence of significant electronic interactions between Fe and UIO-66.

Figure 3.

(a) XPS survey spectra, (b) O 1s, (c) Fe 2p, and (d) Zr 3d high-resolution spectra of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66.

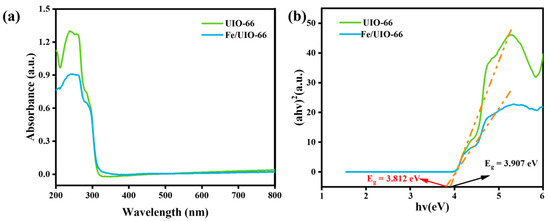

3.5. UV-Vis DRS Analysis

UV-Vis DRS was used to analyze the light absorption capacity and band gap of the UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 photocatalysts. As can be seen from Figure 4a, the maximum absorption band of the Fe/UIO-66 catalyst exhibits a red shift compared to that of the UIO-66 catalyst, indicating that the introduction of Fe broadens the light absorption range and enhances the material’s ability to absorb visible light [23]. This phenomenon may be attributed to the electronic interaction between Fe and UIO-66. It can be observed from Figure 4b that the band gap of UIO-66 is 3.907 eV, while that of Fe/UIO-66 is 3.812 eV. The narrower band gap of Fe/UIO-66 facilitates the electron transition from the valence band to the conduction band, thereby promoting the separation of photogenerated charge carriers. Therefore, the Fe/UIO-66 catalyst may exhibit better performance in the photocatalytic process.

Figure 4.

(a) UV-Vis DRS spectra and (b) band gap plots of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66.

3.6. Photocatalytic Performances

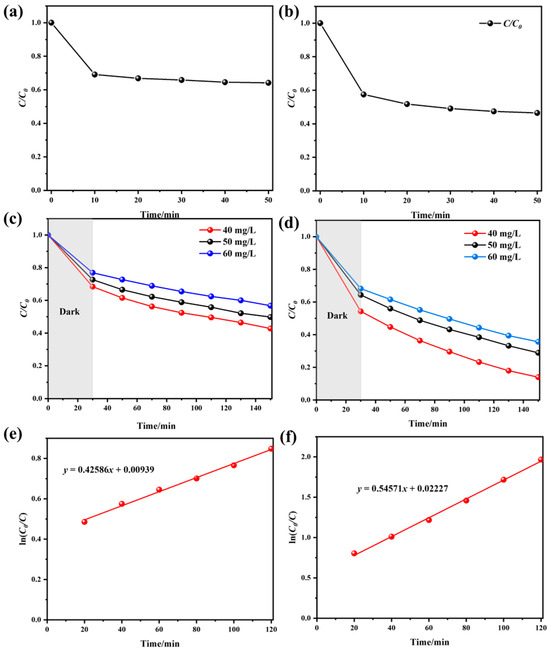

The dark adsorption curves of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 are shown in Figure 5a,b. It can be observed that the adsorption process of TC by both catalysts mainly occurs in the first 10 min, and the concentration remains basically unchanged after 30 min. Therefore, performing dark adsorption for 30 min before light irradiation can rule out the decrease in TC concentration caused by the adsorption of TC by the catalyst.

Figure 5.

(a) Dark adsorption curves of UIO-66. (b) Dark adsorption curves of Fe/UIO-66. (c) TC degradation efficiencies of UIO-66 at different concentrations. (d) TC degradation efficiencies of Fe/UIO-66 at different TC concentrations. Kinetic fittings of (e) UIO-66 and (f) Fe/UIO-66 for 40 mg/L TC degradation.

As shown in Figure 5c,d, with the increase in TC solution concentration, the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of TC by UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 shows a gradual downward trend. The decline in efficiency may be attributed to a reduced density of photocatalytic active sites relative to the pollutant load. In addition, the intermediate products generated during the photocatalytic degradation process also compete with TC for the limited photocatalytic active sites, which also results in a decrease in photocatalytic performance [24]. By comparing the photocatalytic degradation efficiencies of the two catalysts, it can be found that the photocatalytic degradation rate of Fe/UIO-66 is higher than that of UIO-66, indicating that the introduction of Fe improves the photocatalytic performance of UIO-66. It can be observed from Figure 5e,f that ln(C0/C) has a linear relationship with the photocatalytic reaction time, which demonstrates that the degradation of the TC solution by both UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 catalysts follows pseudo-first-order reaction kinetics. The reaction rates of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66 are 0.42856 min−1 and 0.54571 min−1, respectively. It is evident that the degradation rate of TC by Fe/UIO-66 is higher than that of UIO-66.

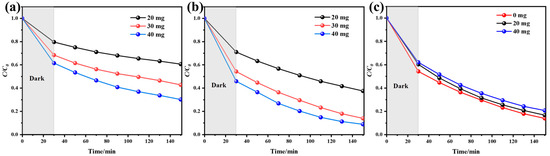

As shown in Figure 6a,b, with the increase in the mass of the two catalysts, the overall photocatalytic efficiency shows an upward trend. At a constant TC concentration, increasing the catalyst dosage provides more photocatalytic active sites, thus leading to a superior overall photocatalytic degradation efficiency [25]. Among them, the degradation efficiency of Fe/UIO-66 when its mass is 20 mg differs significantly from that when the mass is 30 mg or 40 mg. This may be due to the insufficient number of active sites in the catalyst with low dosage, thereby compromising the degradation efficiency of TC.

Figure 6.

(a) Effect of UIO-66 dosage on TC degradation efficiency. (b) Effect of Fe/UIO-66 dosage on TC degradation efficiency. (c) Effect of K2SO4 on TC degradation by Fe/UIO-66 catalyst.

Various anions and cations usually exist in actual wastewater, and these ions may have a certain impact on the photocatalytic degradation process. To investigate their influence on the photocatalytic degradation of TC by Fe/UIO-66, experiments were conducted by adding K2SO4 (0 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg) to simulate wastewater. As can be seen from Figure 6c, the K+ and SO42− ions have a relatively small impact on the photocatalytic degradation of TC by Fe/UIO-66. This indicates that Fe/UIO-66 can effectively resist the interference of anions and cations present in actual wastewater, thus showing good application prospects in the treatment of practical industrial and domestic wastewater [26].

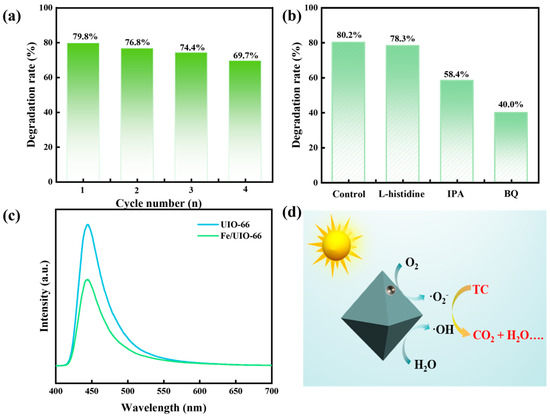

After four consecutive cyclic stability tests, the degradation efficiency of Fe/UIO-66 for TC only decreased by approximately 10%, indicating excellent stability of the catalyst (Figure 7a). The quenching experiment was conducted to evaluate the influence of different reactive species on the photocatalytic degradation efficiency, and the results were presented in Figure 7b. To achieve this, targeted scavengers like isopropyl alcohol (IPA), p-benzoquinone (BQ), and L-histidine were added to the reaction solution to trap key reactive species, including hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide radicals (•O2−), and photogenerated holes (h+). The results indicated that •O2− played a dominant role in the process, followed by •OH. Furthermore, the reduced photoluminescence (PL) emission intensity of Fe/UIO-66 was indicative of a higher separation efficiency of photoinduced charge carriers in Figure 7c. Based on the above mechanistic investigations, a plausible photocatalytic degradation mechanism was illustrated in Figure 7d. Upon exposure to simulated sunlight, Fe/UIO-66 generated •O2− and •OH through reactions with O2 and H2O, respectively, which subsequently decompose TC into small-molecule compounds.

Figure 7.

(a) Cyclic stability of Fe/UIO-66 dosage on TC degradation efficiency. (b) Quenching experiment. (c) PL spectra of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66. (d) Possible photocatalytic degradation mechanism.

4. Conclusions

In this study, an Fe/UIO-66 photocatalyst was successfully prepared via a solvothermal method. Combined with characterization techniques, it was confirmed that the introduction of Fe did not destroy the framework structure of UIO-66, but there was a significant electronic interaction between Fe and UIO-66, thus improving the optical properties. Photocatalytic experiments showed that the degradation rate of TC by Fe/UIO-66 could reach 80% within 120 min, exhibiting better catalytic activity than UIO-66. Experiments simulating real wastewater environments demonstrated that inorganic ions have little effect on the catalytic performance, verifying the applicability of the catalyst in complex water bodies. This study provides a high-efficiency Fe/UIO-66 catalyst for the photocatalytic removal of antibiotic pollutants. This enhancement is a direct result of Fe modification, which concurrently promotes the separation of photogenerated charge carriers and enables the material to harness a wider spectrum of incident light, offering a new technical strategy for the removal of organic pollutants in environmental governance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemistry7060197/s1, Figure S1: Standard curve of TC; Figure S2: FTIR spectra of UIO-66 and Fe/UIO-66.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X.; validation, B.W. and Y.W.; investigation, B.W. and Y.W.; data curation, J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.X. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.L.; supervision, J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.X., J.Y. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation-Guiding Program Project (No. 2025AFC034), Jingmen Municipal Major Science and Technology Innovation Program Project (No. 2023ZDYF004), Scientific Research Project of Hubei Provincial Department of Education (No. F2023026), and the research start-up fund from Jingchu University of Technology (No. YY202434, YYZ202526).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Long, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wu, L.; Sun, C.; Jiao, F. Controllable one-step production of 2D MgAl-LDH for photocatalytic removal of tetracycline. Desalin. Water Treat. 2023, 313, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Gan, C.; Peng, Y.E.; Gan, Y.; He, J.; Du, Y.; Tong, L.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y. Occurrence and source identification of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in groundwater surrounding urban hospitals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 465, 133368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.C.; Xu, Q.; Keller, V.D.J. Translating antibiotic prescribing into antibiotic resistance in the environment: A hazard characterisation case study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Zhao, X.; Song, K.; Gao, D.; Yang, Z.; Han, L. Valorizing copper-contaminated manure into biochar for tetracycline adsorption: Dynamics and interactions of tetracycline adsorption and copper leaching. Waste Manag. 2025, 203, 114880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Performance of traditional and emerging water-treatment technologies in the removal of tetracycline antibiotics. Catalysts 2024, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariyarath, R.V.; Inagaki, Y.; Sakakibara, Y. Phycoremediation of tetracycline via bio-Fenton process using diatoms. J. Water Process. Eng. 2021, 40, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, D.; Song, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rao, L.; Fu, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Recent progress of cellulose-based hydrogel photocatalysts and their applications. Gels 2022, 5, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xua, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, H.; Tu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Wu, C.; Su, S.; Lv, Y.; et al. Improved bisphenol A degradation under visible-light irradiation through a Bi2Ti2O7/g-C3N4 binary Z-scheme heterojunction. Desalin. Water Treat. 2023, 316, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, P.; Zhang, X. Ag2Se nanoparticles anchored on S-g-C3N4 nanosheets towards efficient photocatalytic tetracycline hydrochloride removal and H2 generation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchene, B.; Schneider, R. Graphitic carbon nitride/SmFeO3 composite Z-scheme photocatalyst with high visible light activity. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 465704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, R.M.; Mahaveer, D.K.; Kigga, M. A comprehensive review on water remediation using UIO-66 MOFs and their derivatives. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Huang, L.; Sun, T.; Gao, Z. Photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline by UiO-66-S-FeS composites for visible light: Mechanistic on compact interfacial and degradation pathways. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2025, 464, 116343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.M.N.; Vo, T.K.; Phuong, N.H.Y.; Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, V.C.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Dang, N.T.T. Fe (III)-incorporated UIO-66 (Zr)-NH2 frameworks: Microwave-assisted scalable production and their enhanced photo-Fenton degradation catalytic activities. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 355, 129723. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Lynch, I.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wu, L.; Ma, J. Construction of urchin-like core-shell Fe/Fe2O3@UIO-66 hybrid for effective tetracycline reduction and photocatalytic oxidation. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, X.; Bao, Z.; Yang, Q.; Ren, Q.; et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of Fe@UiO-66 for aerobic oxidation of N-aryl tetrahydroisoquinolines. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Sun, K.; Gao, M.L.; Metin, Ö.; Jiang, H.L. Optimizing Pt electronic states through formation of a schottky junction on non-reducible metal-organic frameworks for enhanced photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202206108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, M.C.; Wiederrecht, G.P.; Mondloch, J.E.; Hupp, J.T.; Farha, O.K. Metal-organic framework materials for light-harvesting and energy transfer. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3501–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Chen, B.; Cai, W.; Xi, Y.; Ye, T.; Wang, C.; Lin, X. UIO-66-supported Fe catalyst: A vapour deposition preparation method and its superior catalytic performance for removal of organic pollutants in water. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 182047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Song, L.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Enhanced adsorption performance of gaseous toluene on defective UIO-66 metal organic framework: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 365, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Yang, Z.; He, C.; Tong, X.; Li, Y.; Niu, X.; Zhang, H. UIO-66(Zr) coupled with Bi2MoO6 as photocatalyst for visible-light promoted dye degradation. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2017, 497, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Song, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Complete chromium removal via photocatalytic reduction and adsorption using bimetallic UIO-66 (Zr/Al). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, A.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, K.; Wang, H. Preparation of imidazole ligand zirconium-based UIO-66 and its application in the direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from CO2 and methanol. J. CO2 Util. 2025, 98, 103148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Shuai, D.; Shen, Y.; Xiong, W.; Wang, L. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)-based photocatalysts for water disinfection and microbial control: A review. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Feng, Y.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Photocatalytic degradation of fluoroquinolone antibiotics using ordered mesoporous g-C3N4 under simulated sunlight irradiation: Kinetics, mechanism, and antibacterial activity elimination. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2018, 227, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, W.; Liang, Q.; Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Yuan, X.; Wang, D.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of 2D/0D g-C3N4/CdS-nitrogen doped hollow carbon spheres (NHCs) composites with enhanced visible light photodegradation activity for antibiotic. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 374, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Li, Y. The influence of inorganic anions on photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).