Ruthenium, Rhodium, and Iridium α-Diimine Complexes as Precatalysts in Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Decomposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

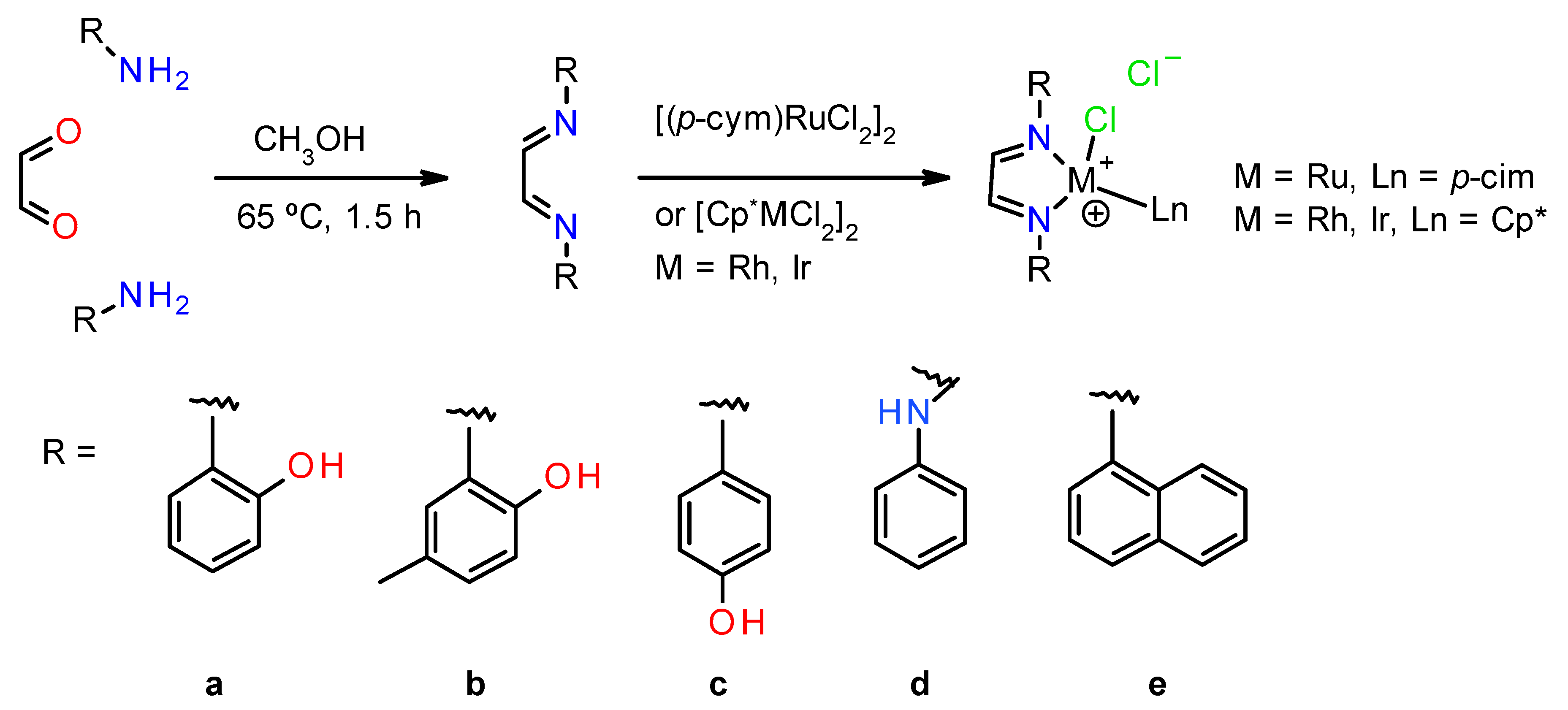

2.1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of the α-Diimine Ligands a–e

2.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of the Complexes

2.3. General Procedure for FA Decomposition in Aqueous Media

2.4. General Procedure for the Evolution of H2 and CO2 Gases via FA Decomposition in Aqueous Media

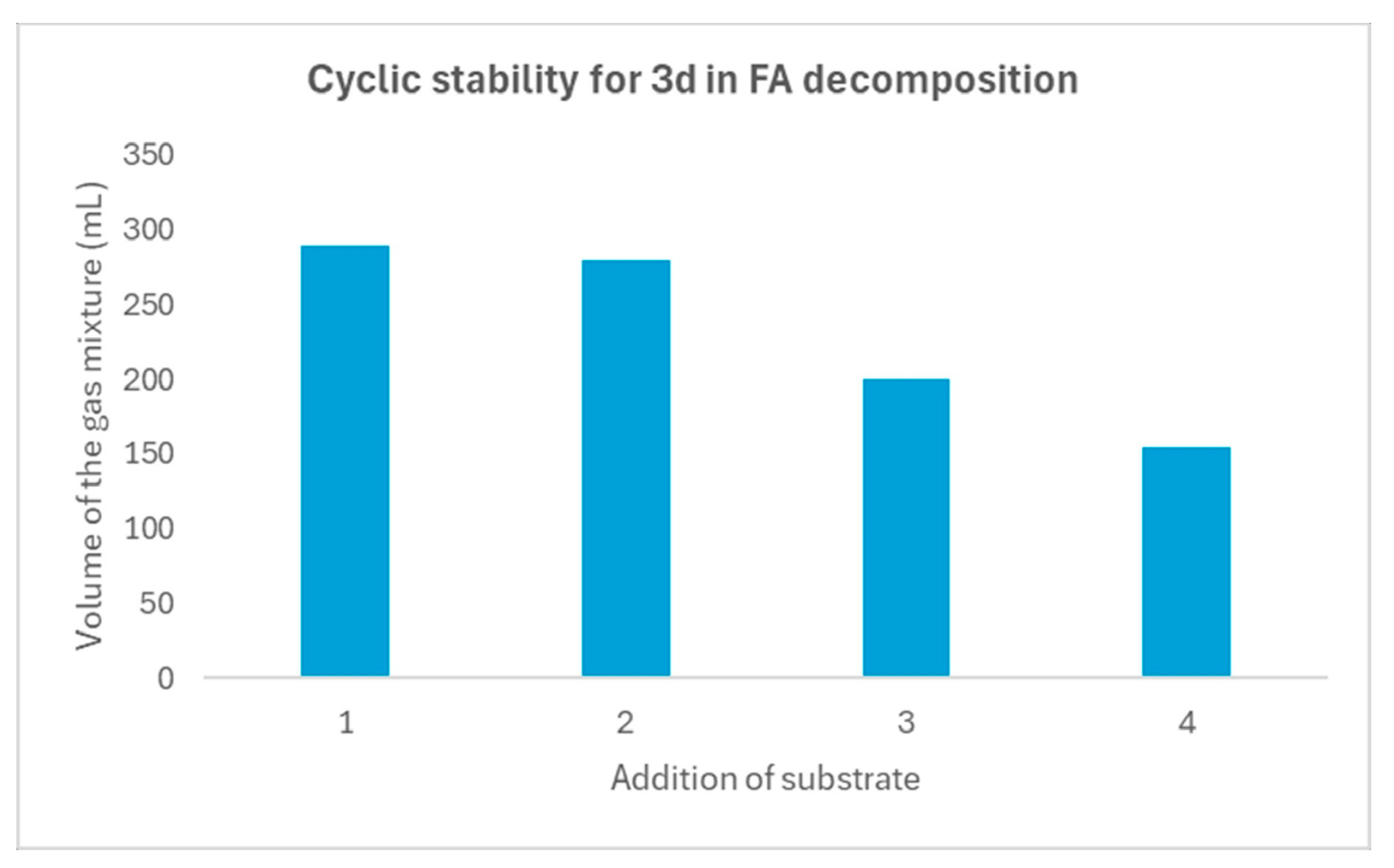

2.5. Catalyst Reusability Test in FA Decomposition

2.6. General Procedure for the Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide

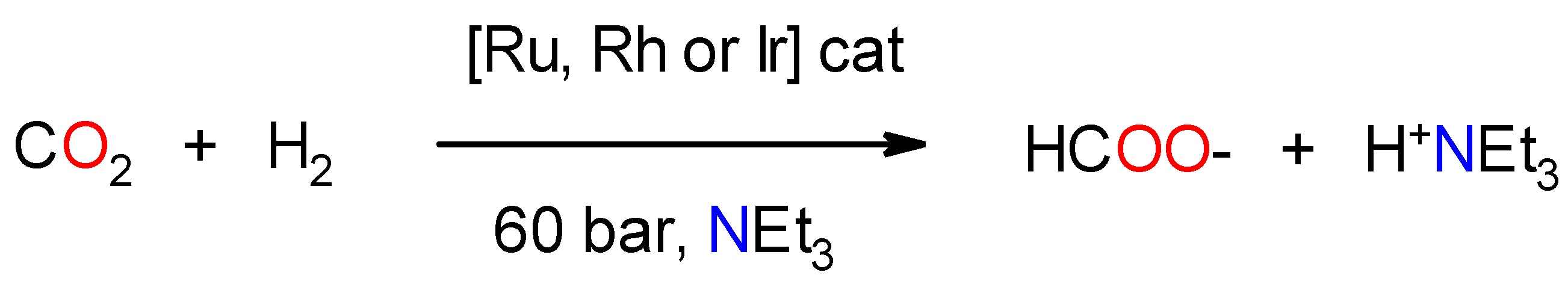

2.7. Catalyst Reusability Test in CO2 Hydrogenation

3. Results and Discussion

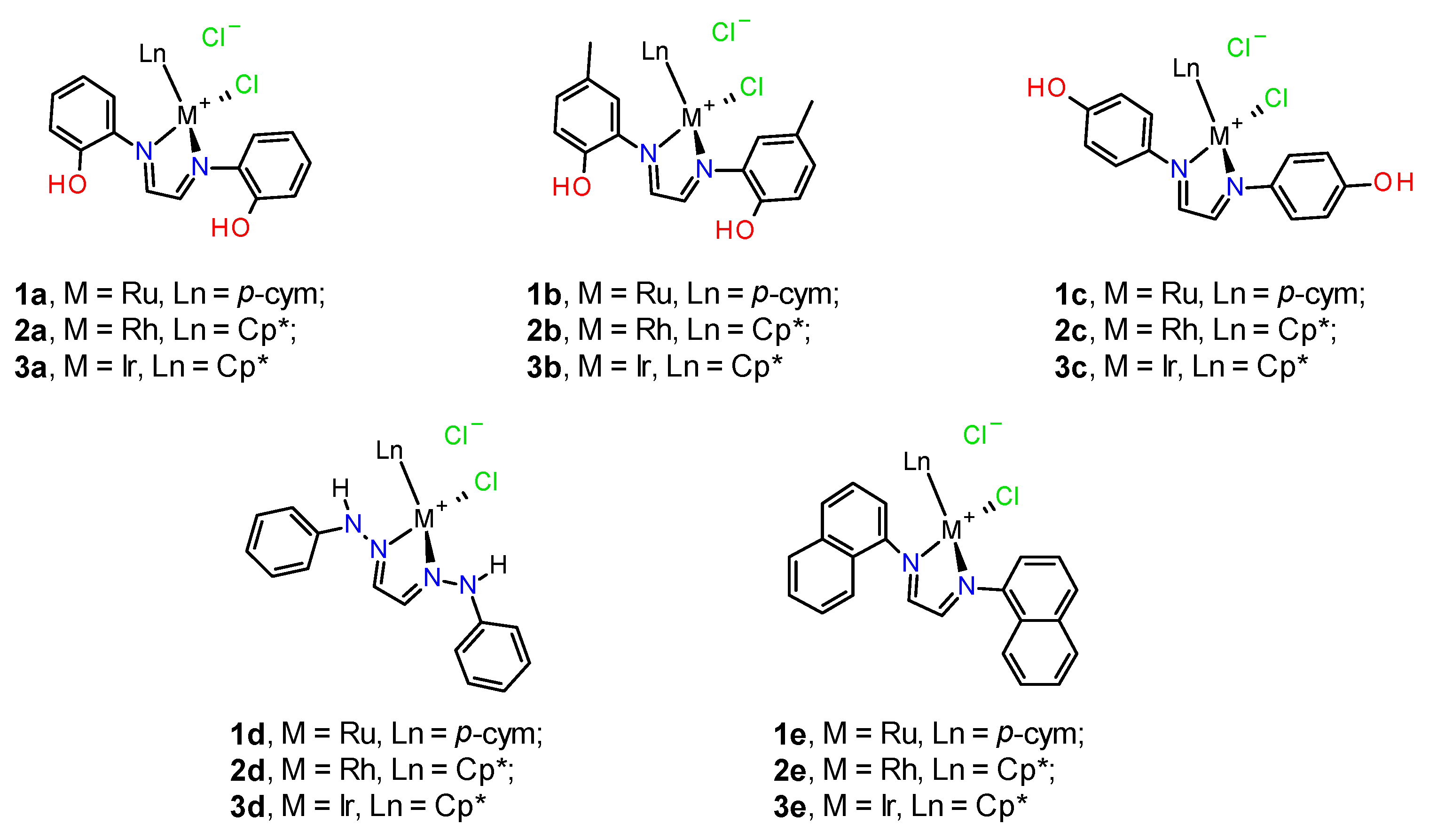

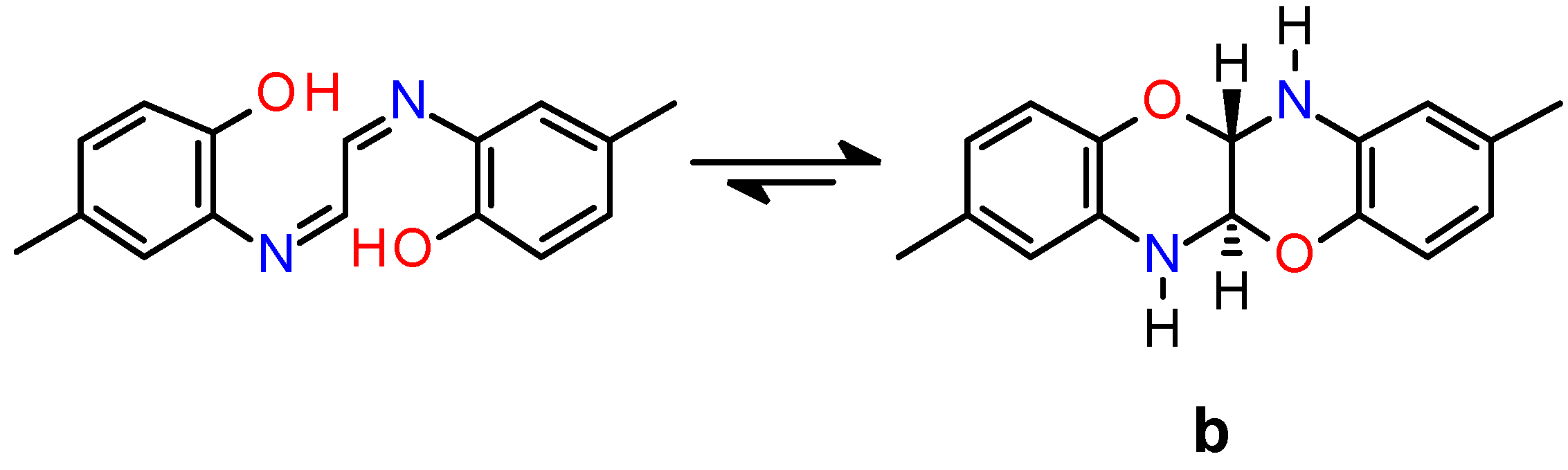

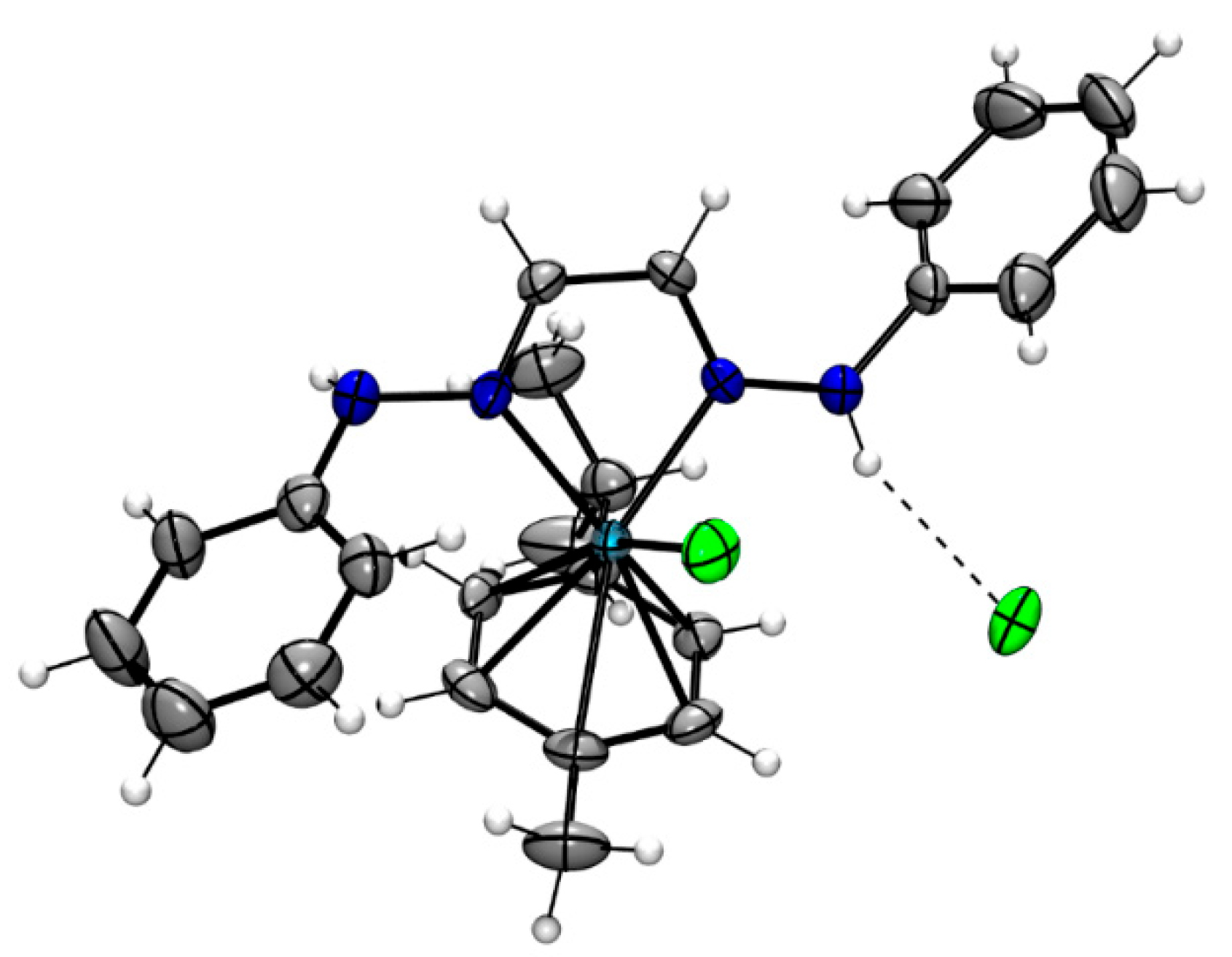

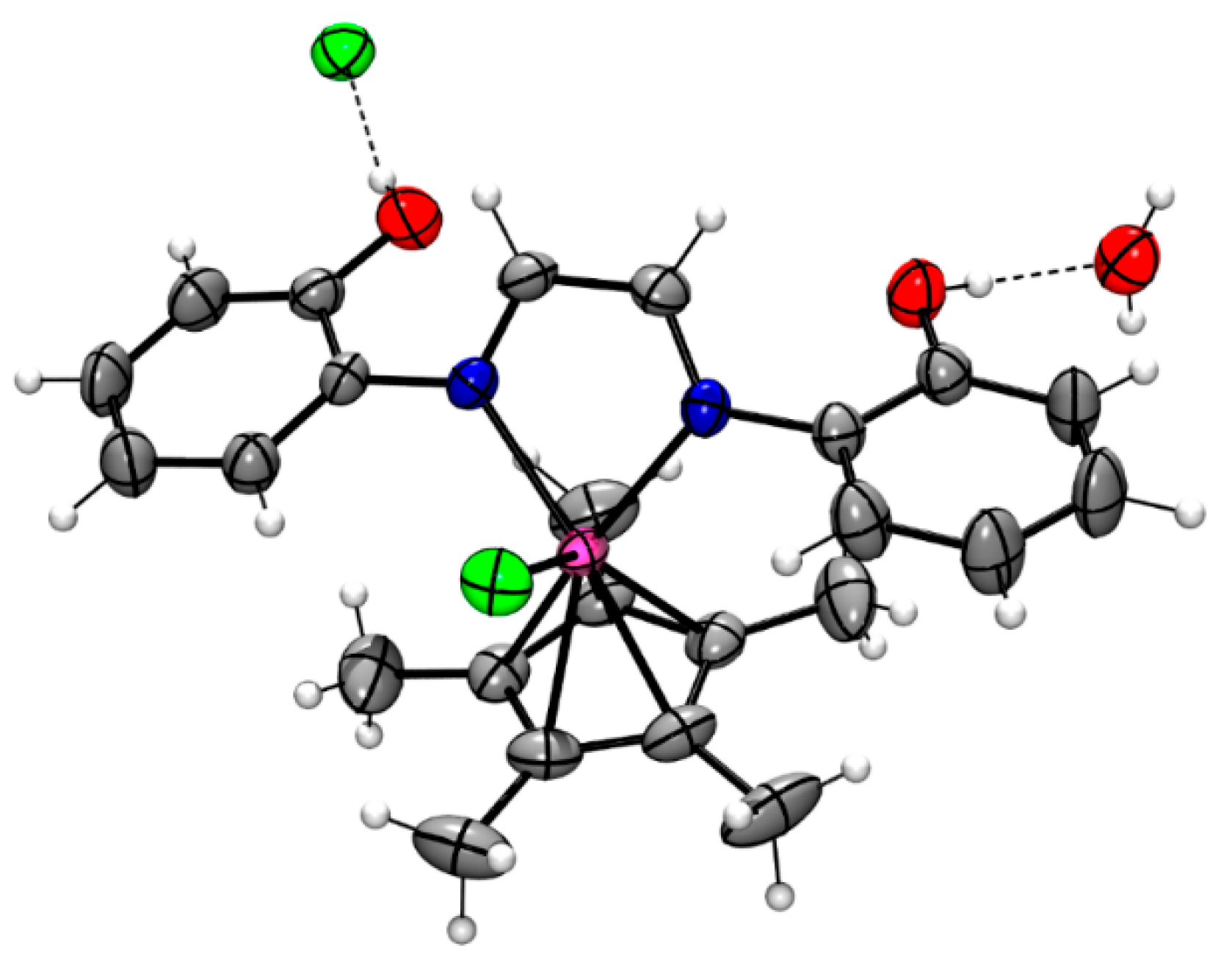

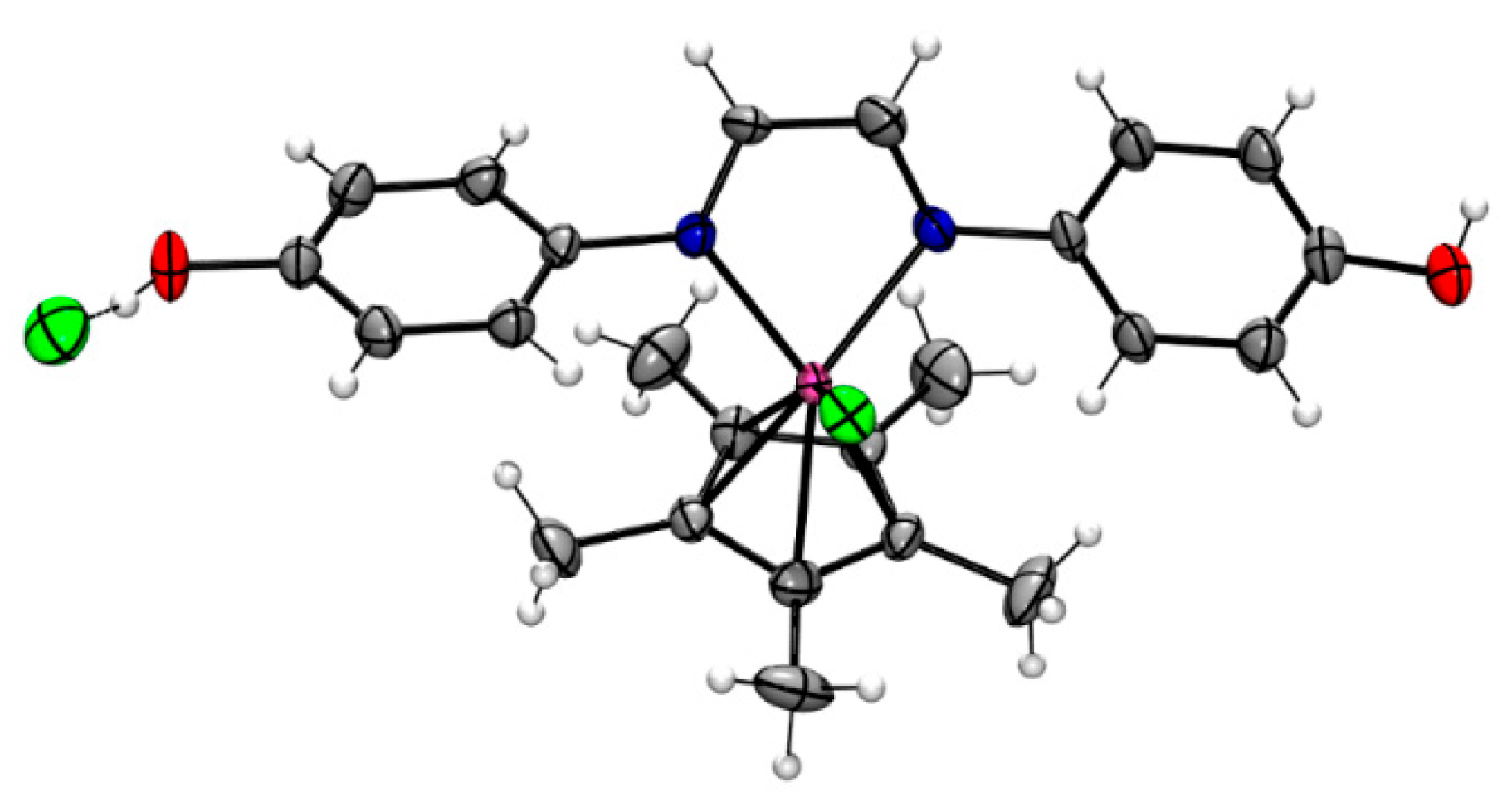

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Ligands and Complexes

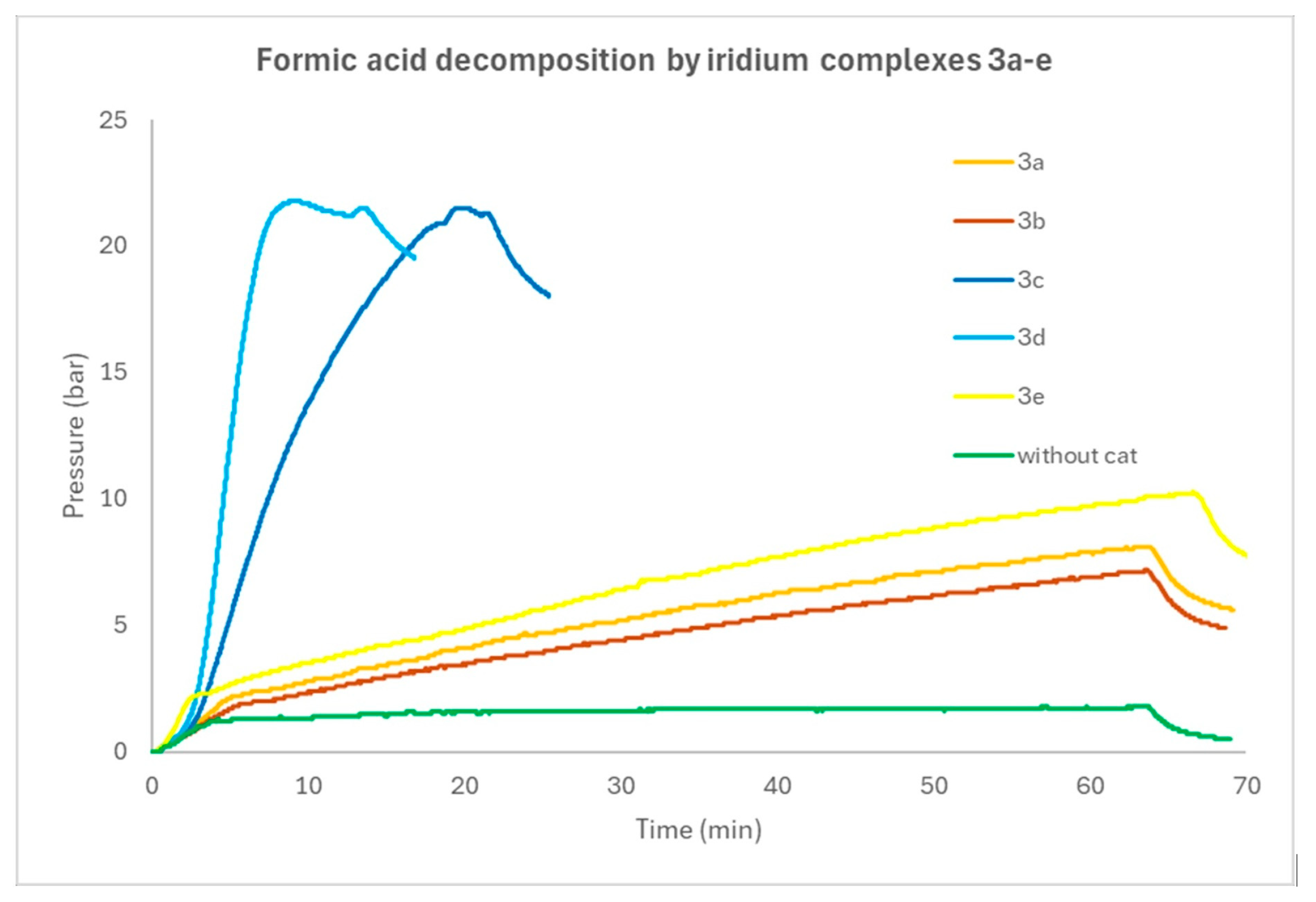

3.2. Catalytic Activity in FA Decomposition Using Complexes as Precatalysts

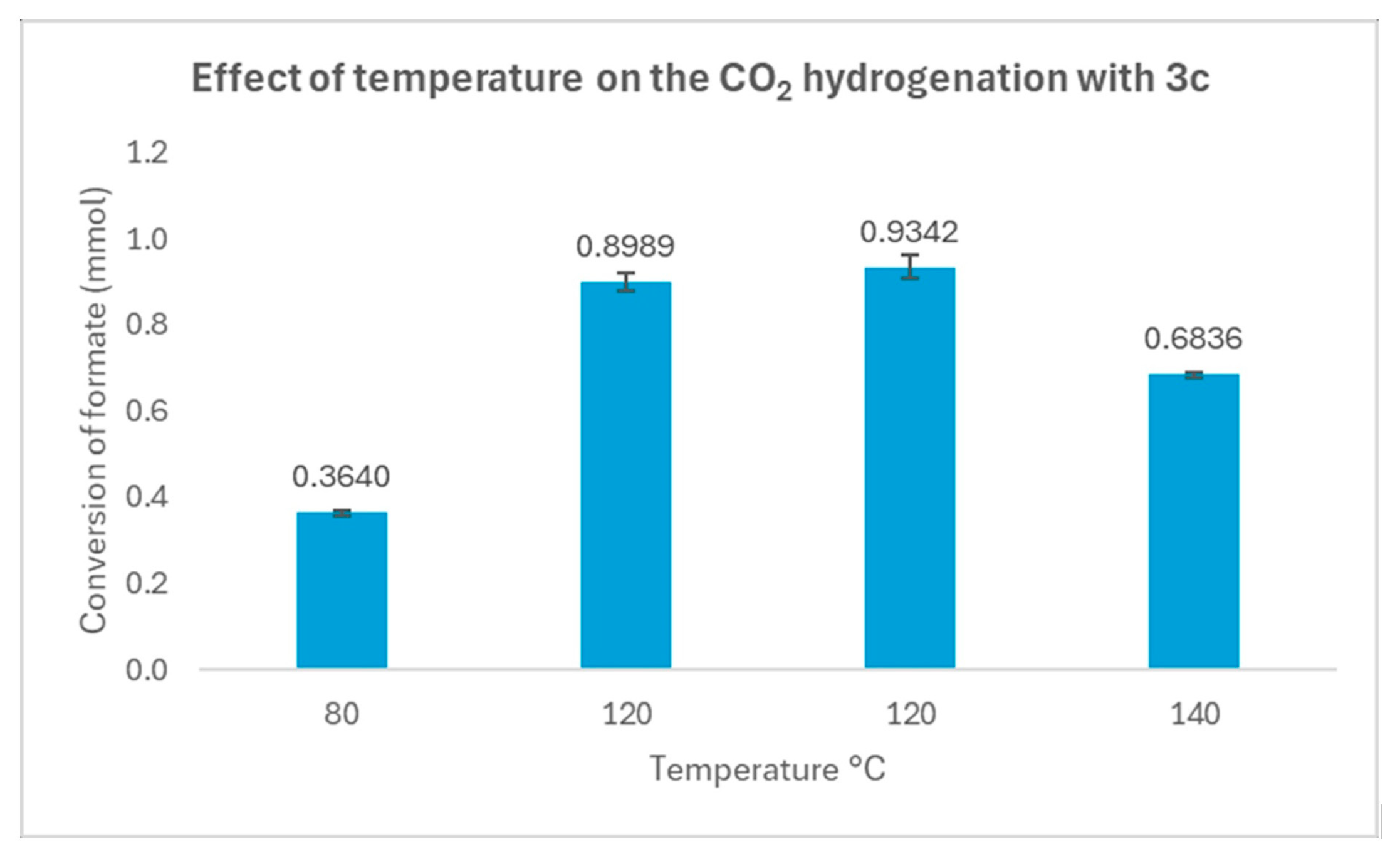

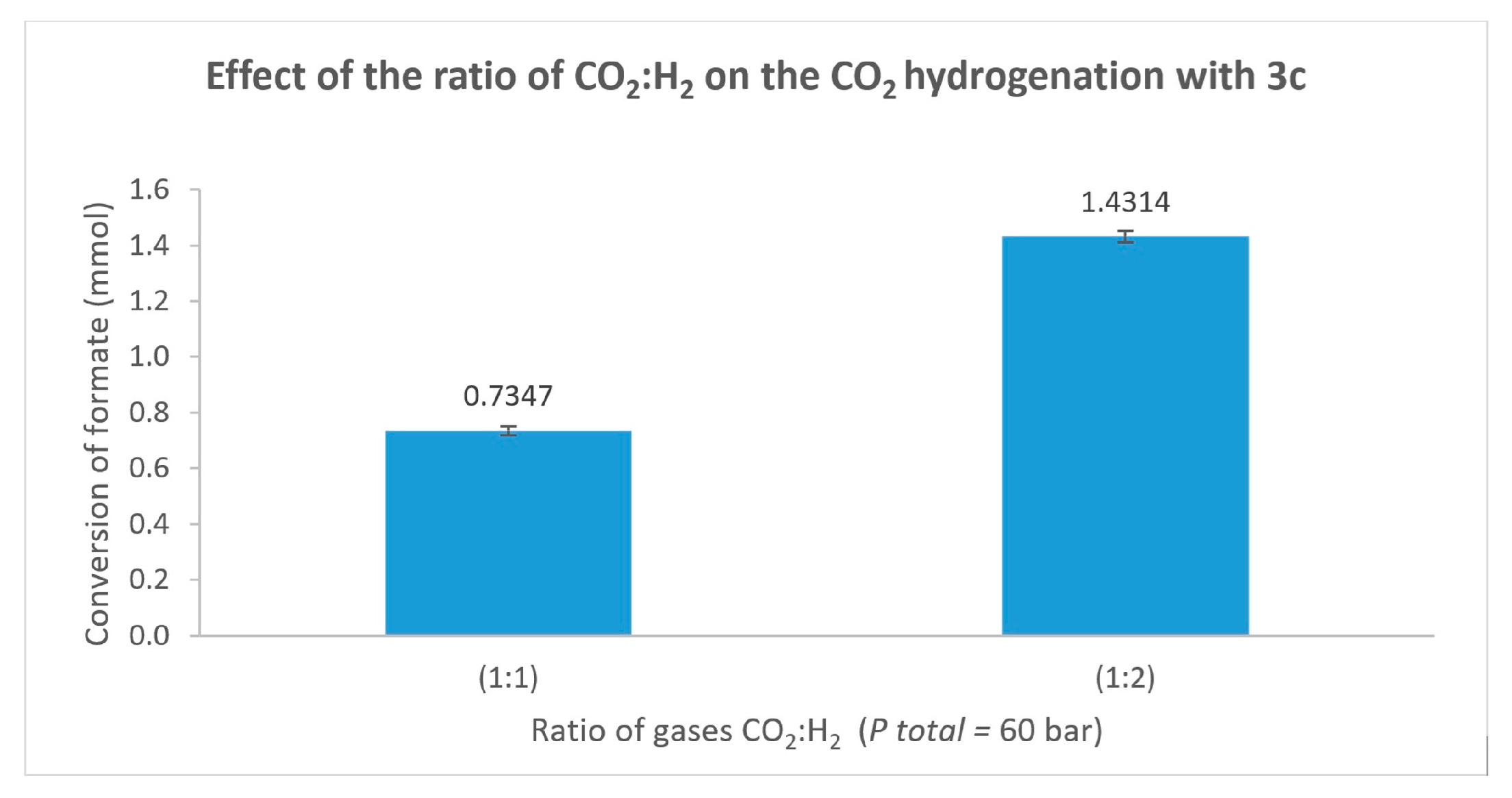

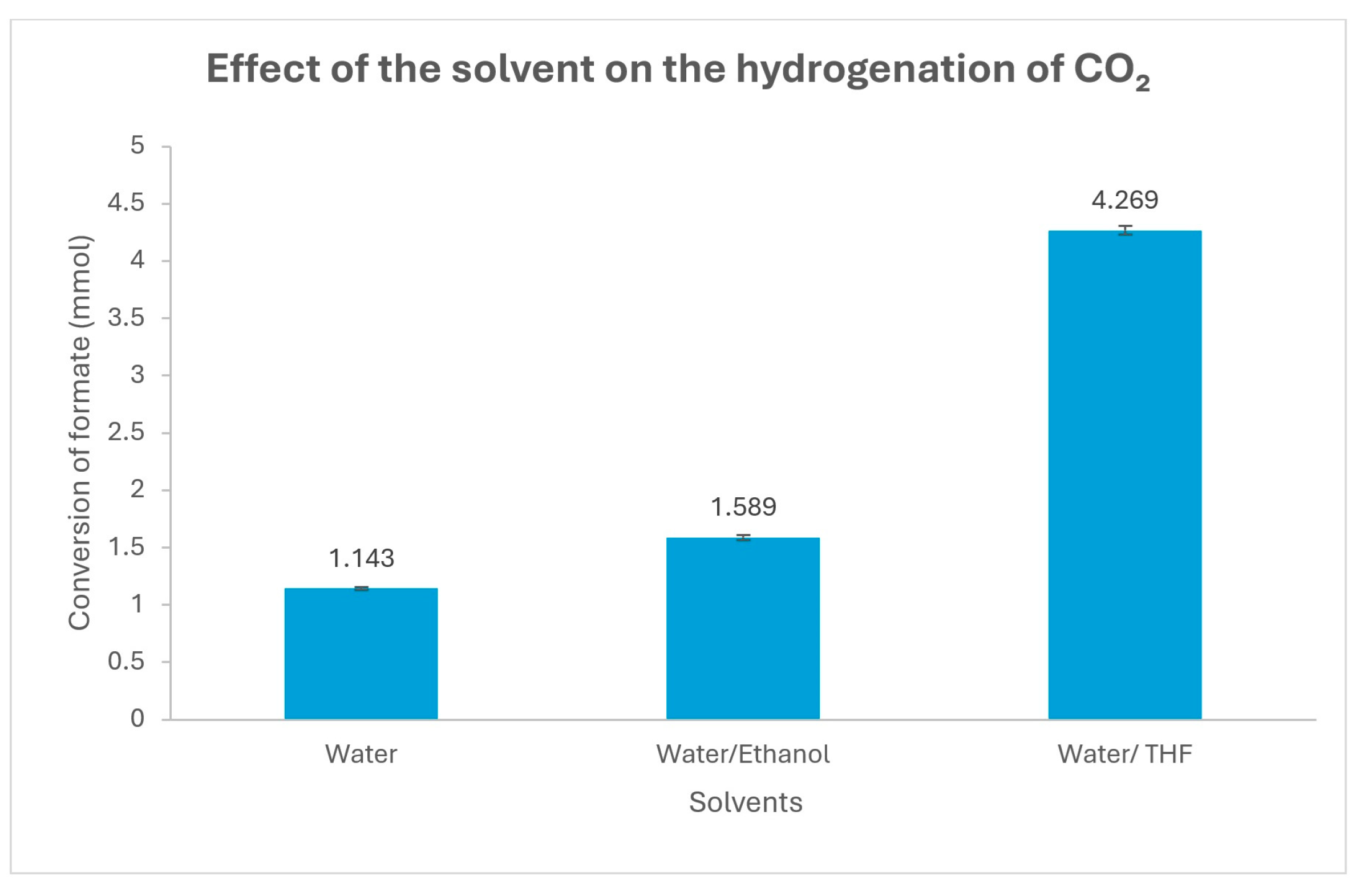

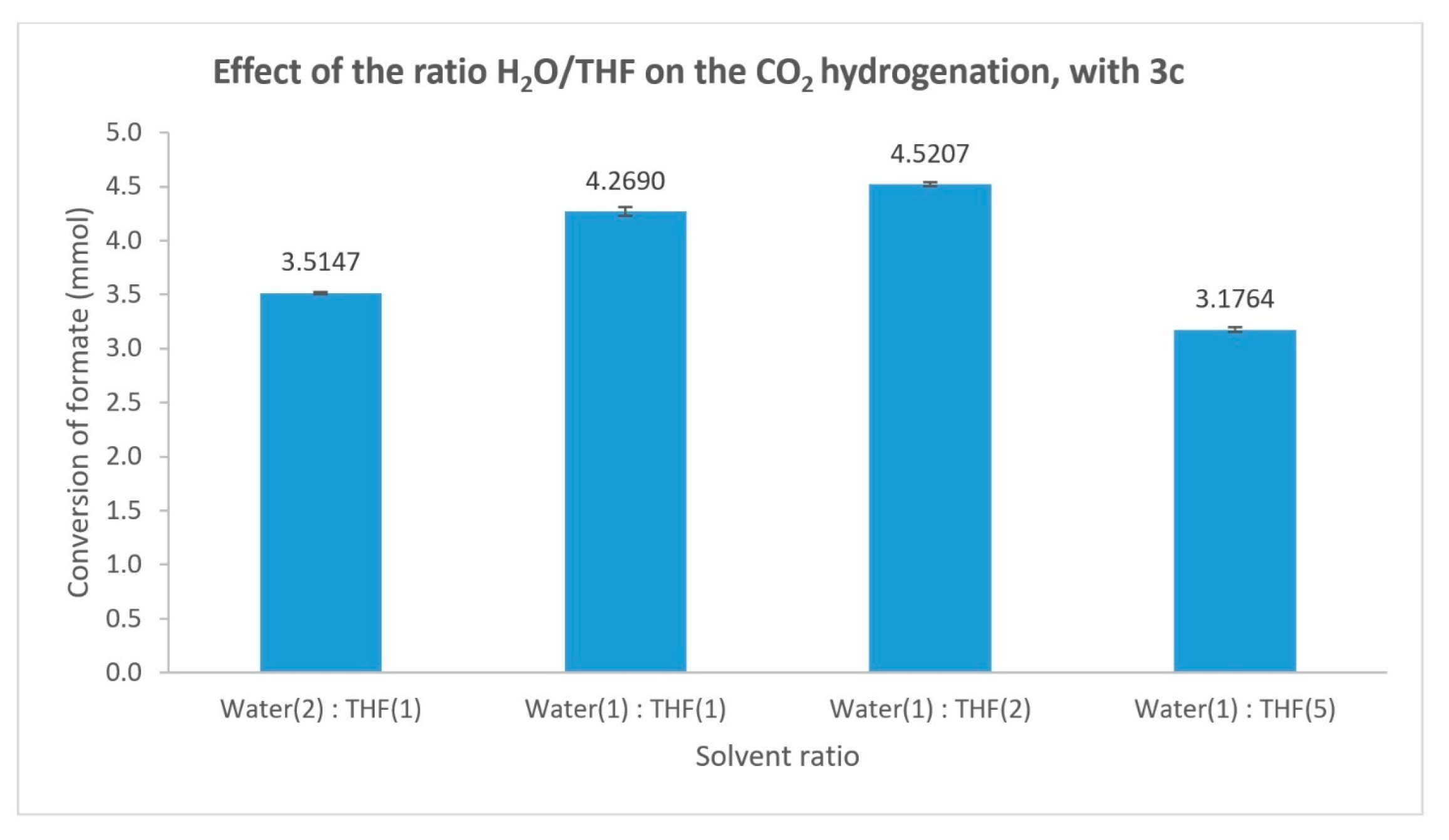

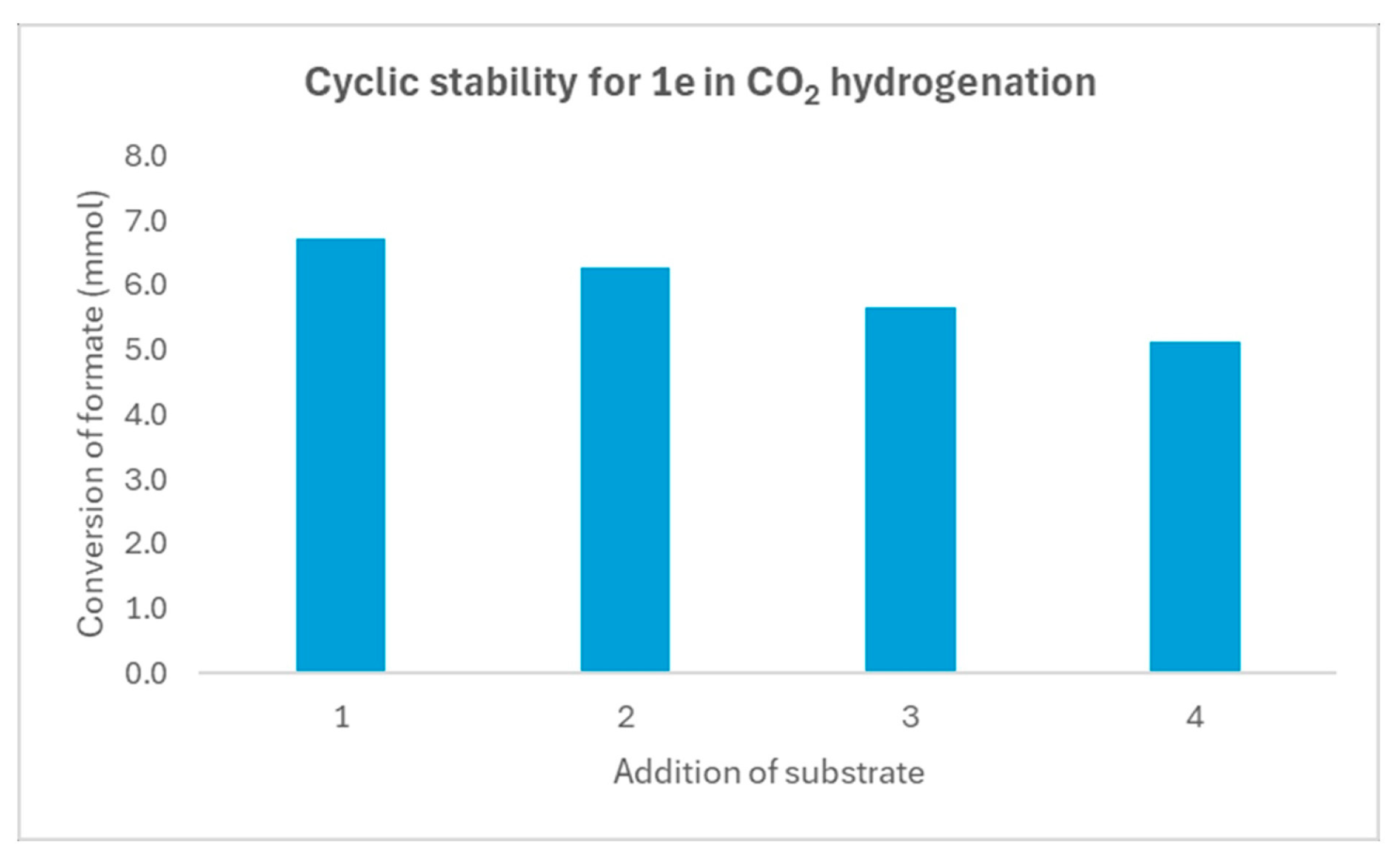

3.3. Catalytic Activity in the Hydrogenation of CO2 Using the Complexes as Precatalysts

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centi, G.; Quadrelli, E.A.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis for CO2 Conversion: A Key Technology for Rapid Introduction of Renewable Energy in the Value Chain of Chemical Industries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, C.; Ha, S.; Masel, R.I.; Waszczuk, P.; Wieckowski, A.; Barnard, T. Direct Formic Acid Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2002, 111, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.C.; Morris, D.J.; Wills, M. Hydrogen Generation from Formic Acid and Alcohols Using Homogeneous Catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zeng, C.; Tsubaki, N. Recent Advancements and Perspectives of the CO2 Hydrogenation Reaction. Green Carbon 2023, 1, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Maji, B.; Kawanami, H.; Himeda, Y. High-Pressure Hydrogen Generation from Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 1655–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.E.; Pattanayak, S.; Berben, L.A. Reactive Capture of CO2: Opportunities and Challenges. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 766–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Izumida, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Hashimoto, H. Catalytic Fixation of Carbon Dioxide to Formic Acid by Transition-Metal Complexes under Mild Conditions. Chem. Lett. 1976, 5, 863–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Himeda, Y.; Muckerman, J.T.; Manbeck, G.F.; Fujita, E. CO2 Hydrogenation to Formate and Methanol as an Alternative to Photo- and Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12936–12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siek, S.; Burks, D.B.; Gerlach, D.L.; Liang, G.; Tesh, J.M.; Thompson, C.R.; Qu, F.; Shankwitz, J.E.; Vasquez, R.M.; Chambers, N.; et al. Iridium and Ruthenium Complexes of N-Heterocyclic Carbene- and Pyridinol-Derived Chelates as Catalysts for Aqueous Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Dehydrogenation: The Role of the Alkali Metal. Organometallics 2017, 36, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filonenko, G.A.; Van Putten, R.; Schulpen, E.N.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Pidko, E.A. Highly Efficient Reversible Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Formates Using a Ruthenium PNP-Pincer Catalyst. ChemCatChem 2014, 6, 1526–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, S.; Azua, A.; Peris, E. ‘(H6-Arene)Ru(Bis-NHC)’ Complexes for the Reduction of CO2 to Formate with Hydrogen and by Transfer Hydrogenation with IPrOH. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 6339–6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Yamashita, M.; Nozaki, K. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide Using Ir(III)−Pincer Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14168–14169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azua, A.; Sanz, S.; Peris, E. Water-Soluble IrIII N-Heterocyclic Carbene Based Catalysts for the Reduction of CO2 to Formate by Transfer Hydrogenation and the Deuteration of Aryl Amines in Water. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17, 3963–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponholz, P.; Mellmann, D.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. Towards a Practical Setup for Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid. ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 1172–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-H.; Ertem, M.Z.; Xu, S.; Onishi, N.; Manaka, Y.; Suna, Y.; Kambayashi, H.; Muckerman, J.T.; Fujita, E.; Himeda, Y. Highly Robust Hydrogen Generation by Bioinspired Ir Complexes for Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid in Water: Experimental and Theoretical Mechanistic Investigations at Different PH. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5496–5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, M.; Himeda, Y.; Manaka, Y.; Kawanami, H. Development of an Iridium-Based Catalyst for High-Pressure Evolution of Hydrogen from Formic Acid. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 2749–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccirilli, L.; Rabell, B.; Padilla, R.; Riisager, A.; Das, S.; Nielsen, M. Versatile CO2 Hydrogenation-Dehydrogenation Catalysis with a Ru-PNP/Ionic Liquid System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 5655–5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, N.; Albrecht, M. A Low-Coordinate Iridium Complex with a Donor-Flexible O,N-Ligand for Highly Efficient Formic Acid Dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 12627–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Sang, R.; Sponholz, P.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. Reversible Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Formic Acid Using a Mn-Pincer Complex in the Presence of Lysine. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechenkin, A.; Badmaev, S.; Belyaev, V.; Sobyanin, V. Production of Hydrogen-Rich Gas by Formic Acid Decomposition over CuO-CeO2/γ-Al2O3 Catalyst. Energies 2019, 12, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, A.; Diglio, M.; Impemba, S.; Venditto, V.; Vaiano, V.; Buonerba, A.; Sacco, O. Dual-Function Bare Copper Oxide (Photo)Catalysts for Selective Phenol Production via Benzene Hydroxylation and Low-Temperature Hydrogen Generation from Formic Acid. Catalysts 2025, 15, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diglio, M.; Contento, I.; Impemba, S.; Berretti, E.; Della Sala, P.; Oliva, G.; Naddeo, V.; Caporali, S.; Primo, A.; Talotta, C.; et al. Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid Decomposition Promoted by Gold Nanoparticles Supported on a Porous Polymer Matrix. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 14320–14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, W.; Liu, Q.; Geng, J.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X. Reaction and Separation System for CO2 Hydrogenation to Formic Acid Catalyzed by Iridium Immobilized on Solid Phosphines under Base-Free Condition. iScience 2023, 26, 106672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ittel, S.D.; Johnson, L.K.; Brookhart, M. Late-Metal Catalysts for Ethylene Homo- and Copolymerization. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1169–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuve, N.; Mehlana, G.; Tia, R.; Darkwa, J.; Makhubela, B.C.E. Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Formate by α-Diimine RuII, RhIII, IrIII Complexes as Catalyst Precursors. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 899, 120892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancalana, L.; Batchelor, L.K.; Funaioli, T.; Zacchini, S.; Bortoluzzi, M.; Pampaloni, G.; Dyson, P.J.; Marchetti, F. α-Diimines as Versatile, Derivatizable Ligands in Ruthenium(II) p-Cymene Anticancer Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 6669–6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, E.; Simpson, S.J. Synthesis and Characterisation of [(η6-Cymene)Ru(L)X2] Compounds: Single Crystal X-Ray Structure of [(η6-Cymene)Ru(P{OPh}3)Cl2] at 203 K. Polyhedron 2004, 23, 2695–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.; Yates, A.; Maitlis, P.M. [(C5Me5)MCl2]2-Rh-Ir.Pdf. Inorg. Synth. 1992, 29, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, D.; Fu, Z.; Zhong, S.; Jiang, X.; Yin, D. Novel Homogeneous Salen Mn(III) Catalysts Synthesized from Dialdehyde or Diketone with o-Aminophenol for Catalyzing Epoxidation of Alkenes. Catal. Lett. 2007, 113, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.S.; Tuononen, H.M.; Rath, S.P.; Ghosh, P. First Ruthenium Complex of Glyoxalbis(N-Phenyl)Osazone (LNHPhH2): Synthesis, X-Ray Structure, Spectra, and Density Functional Theory Calculations of (LNHPhH2)Ru(PPh3)2Cl2. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 5942–5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawama, Y.; Miki, Y.; Sajiki, H. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Deuteration of Aldehydes in D2O. Synlett 2020, 31, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, J.E.; Hunter, K.M.; Gorden, A.E.V. Bonding Interactions in Uranyl α-Diimine Complexes: A Spectroscopic and Electrochemical Study of the Impacts of Ligand Electronics and Extended Conjugation. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 15088–15100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez Rodriguez, G.; Domestici, C.; Bucci, A.; Valentini, M.; Zuccaccia, C.; Macchioni, A. Hydrogen Liberation from Formic Acid Mediated by Efficient Iridium(III) Catalysts Bearing Pyridine-Carboxamide Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 2247–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Tamura, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Onoda, M.; Yamaguchi, R. Dehydrogenative Oxidation of Alcohols in Aqueous Media Catalyzed by a Water-Soluble Dicationic Iridium Complex Bearing a Functional N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligand without Using Base. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 7226–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordakis, K.; Tang, C.; Vogt, L.K.; Junge, H.; Dyson, P.J.; Beller, M.; Laurenczy, G. Homogeneous Catalysis for Sustainable Hydrogen Storage in Formic Acid and Alcohols. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 372–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Entry | [3c] (mmol) | [HCOOH]residual (mmol) | Conversion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.82 × 10−3 | 0.0821 | 96.9 |

| 2 | 2.82 × 10−4 | 1.1530 | 56.5 |

| 3 | 2.82 × 10−5 | 2.65 | 0 |

| 4 a | 2.82 × 10−4 | 0.9059 | 65.8 |

| Entry | Complex | Time (min) | [H2] (mmol) | Conversion (%) | TON | TOF (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3a | 55 | 1.88 ± 0.11 | 70.93 | 1416.1 | 1519.8 |

| 2 | 3b | 57 | 1.68 ± 0.09 | 64.65 | 1350.7 | 1264.4 |

| 3 | 3c | 55 | 2.62 ± 0.01 | 98.94 | 1975.4 | 1835.2 |

| 4 a | 3c | 60 | 2.62 ± 0.01 | 98.82 | 1973.8 | 1973.8 |

| 5 | 3d | 32 | 2.62 ± 0.01 | 99.53 | 1980.5 | 3203.2 |

| 6 b | 3e | 60 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 16.25 | 192.53 | 192.4 |

| 7 | 2a | 51 | 1.60 ± 0.09 | 59.60 | 1186.0 | 1379.9 |

| 8 | 2b | 55 | 1.79 ± 0.08 | 66.12 | 1315.6 | 1383.0 |

| 9 | 2c | 55 | 2.08 ± 0.06 | 75.98 | 1511.9 | 1645.6 |

| 10 | 2e | 60 | 1.43 ± 0.10 | 54.08 | 1076.1 | 1076.8 |

| 11 | 1b | 62 | 0.42 ± 0.24 | 15.90 | 283.80 | 274.7 |

| 12 | 1c | 60 | 0.85 ± 0.17 | 28.64 | 484.6 | 484.6 |

| 13 | 1d | 64 | 0.79 ± 0.32 | 29.73 | 503.0 | 470.4 |

| 14 | 1e | 64 | 0.49 ± 0.12 | 17.82 | 301.5 | 281.4 |

| Entry | Complex | Time (min) | [H2] (mmol) | Conversion (%) | TON | TOF (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3a | 56 | 4.02 ± 0.28 | 75.8 | 1513.9 | 1624.6 |

| 2 | 3b | 68 | 3.67 ± 1.74 | 69.1 | 1445.6 | 1266.9 |

| 3 | 3c | 75 | 5.34 ± 2.18 | 100.0 | 2013.5 | 1611.3 |

| 4 | 3d | 33 | 5.72 ± 0.12 | 100.0 | 2150.2 | 3861.8 |

| 5 a | 3e | 60 | 0.93 ± 1.40 | 17.7 | 209.6 | 211.7 |

| 6 | 2a | 45 | 3.16 ± 0.07 | 59.7 | 1188.2 | 1584.3 |

| 7 | 2b | 57 | 3.67 ± 0.17 | 69.1 | 1376.9 | 1521.5 |

| 8 | 2c | 52 | 3.85 ± 0.08 | 72.5 | 1444.7 | 1713.7 |

| 9 | 2e | 63 | 2.96 ± 0.17 | 55.9 | 1112.8 | 1089.1 |

| 10 | 1b | 66 | 0.95 ± 0.44 | 18.0 | 321.4 | 293.4 |

| 11 | 1c | 60 | 1.40 ± 0.23 | 26.5 | 449.0 | 449.0 |

| 12 | 1d | 69 | 1.55 ± 0.06 | 29.4 | 497.1 | 430.2 |

| 13 | 1e | 68 | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 16.4 | 277.9 | 245.3 |

| Catalyst Precursor | Substrate | Solvent | T (°C) | Time (h) | TON | TOF (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [RuCl2(C6H6)]2/DPPE [14] | HCO2H | DMOA | 25 | 1080 | >1,000,000 | 1000 |

| [(PNP3)Ru(H)Cl(CO)] [10] | HCO2H/NHex3 | DMF | 90 | 3 | 706,500 | 256,000 |

| [Cp*Ir(pyrimidyl imidazoline)H2O]SO4 [15] | HCO2H/NaO2CH | H2O | 100 | 0.17 | 68,000 | 322,000 |

| [Cp*Ir(PHEN-diol)H2O]SO4 [16] | HCO2H | H2O | 60 | 2600 | 5,000,000 | 1900 |

| [Cp*Ir(d)Cl]Cl, 3d (this work) | HCO2H | H2O | 110 | 0.55 | 2150 | 3861 |

| Entry | Complex | [HCOO−] (mmol) | Conversion (%) | TON | TOF (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 a | 3a | 0.94 ± 0.18 | 13.1 | 188.1 | 9.4 |

| 2 | 3b | 4.74 ± 0.17 | 66.1 | 947.5 | 19.7 |

| 3 | 3c | 4.53 ± 0.10 | 63.1 | 905.5 | 45.3 |

| 4 a,b | 3c | 2.53 ± 0.04 | 49.2 | 706.1 | 35.3 |

| 5 | 3d | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 14.0 | 200.6 | 10.0 |

| 6 | 3e | 4.22 ± 0.12 | 58.8 | 843.2 | 42.2 |

| 7 | 2a | 1.37 ± 0.06 | 19.1 | 274.3 | 13.7 |

| 8 | 2b | 2.33 ± 0.12 | 32.5 | 465.8 | 23.3 |

| 9 | 2c | 1.25 ± 0.16 | 17.5 | 250.5 | 12.5 |

| 10 | 2e | 0.89 ± 0.11 | 12.4 | 177.9 | 8.9 |

| 11 | 1b | 5.47 ± 0.05 | 76.3 | 1094.8 | 54.7 |

| 12 c | 1c | 7.37 ± 0.10 | 100.0 | 1474.5 | 30.7 |

| 13 | 1c | 6.19 ± 0.07 | 86.3 | 1237.6 | 61.9 |

| 14 | 1d | 4.41 ± 0.38 | 61.6 | 882.9 | 44.1 |

| 15 | 1e | 6.92 ± 0.05 | 96.6 | 1384.9 | 69.2 |

| Catalyst Precursor | Solvent | Additive | P(CO2/H2) (bar/bar) | T (°C) | Time (h) | TON | TOF (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [(PNP3)Ru(H)Cl(CO)] [10] | DMF | DBU | 10/30 | 120 | 0.1 | 200,000 | 1,100,000 |

| [(η6-p-cym)Ru(bis-NHC1)Cl]PF6 [11] | H2O | KOH | 20/20 | 200 | 75 | 23,000 | 300 |

| [(PNP1)IrH3] [12] | H2O/THF | KOH | 30/30 | 120 | 48 | 3,500,000 | 73,000 |

| [Ir(bis-NHC2)(AcO)I2] [13] | H2O | KOH | 30/30 | 200 | 75 | 190,000 | 2500 |

| [(η6-p-cym)Ru(e)Cl]Cl, 1e (this work) | H2O/THF | NEt3 | 20/40 | 110 | 20 | 1385 | 69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Segura-Silva, J.C.; Cabrera-Briseño, M.A.; González-Cruz, R.; Cortes-Llamas, S.A.; Alvarado-Rodríguez, J.G.; Becerra-Martínez, E.; Peregrina-Lucano, A.A.; Rangel-Salas, I.I. Ruthenium, Rhodium, and Iridium α-Diimine Complexes as Precatalysts in Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Decomposition. Chemistry 2025, 7, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060196

Segura-Silva JC, Cabrera-Briseño MA, González-Cruz R, Cortes-Llamas SA, Alvarado-Rodríguez JG, Becerra-Martínez E, Peregrina-Lucano AA, Rangel-Salas II. Ruthenium, Rhodium, and Iridium α-Diimine Complexes as Precatalysts in Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Decomposition. Chemistry. 2025; 7(6):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060196

Chicago/Turabian StyleSegura-Silva, Juan C., Miguel A. Cabrera-Briseño, Ricardo González-Cruz, Sara A. Cortes-Llamas, José G. Alvarado-Rodríguez, Elvia Becerra-Martínez, A. Aaron Peregrina-Lucano, and I. Idalia Rangel-Salas. 2025. "Ruthenium, Rhodium, and Iridium α-Diimine Complexes as Precatalysts in Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Decomposition" Chemistry 7, no. 6: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060196

APA StyleSegura-Silva, J. C., Cabrera-Briseño, M. A., González-Cruz, R., Cortes-Llamas, S. A., Alvarado-Rodríguez, J. G., Becerra-Martínez, E., Peregrina-Lucano, A. A., & Rangel-Salas, I. I. (2025). Ruthenium, Rhodium, and Iridium α-Diimine Complexes as Precatalysts in Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Decomposition. Chemistry, 7(6), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060196