Abstract

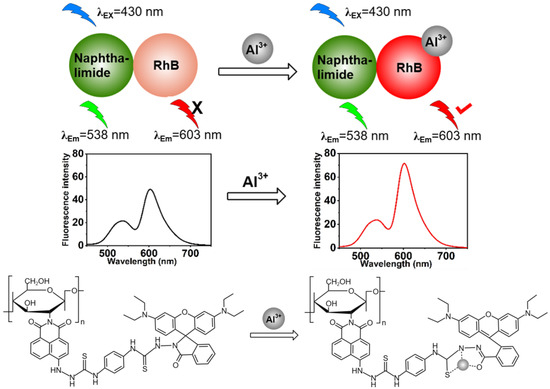

Most reported fluorescent Al3+ probes rely on fluorescence signal enhancement or quenching. Since the change in fluorescence intensity is the sole detection signal, various factors such as instrumental efficiency, environmental conditions, and probe concentration can interfere with the signal output. In contrast, ratiometric probes, which utilize two emission bands for self-calibration, provide significant advantages by minimizing or eliminating these uncertainties. In this study, a naphthalimide-rhodamine based the transition between the cyclic and open-ring forms of rhodamine as an Al3+-selective ratiometric probe, in which chitosan was identified as an ideal bridge and biocompatibility. The design concept was that when the target metal ion was present, the fluorescence intensity of naphthalimide remained largely unchanged, serving as an internal standard. In contrast, rhodamine B was employed to label the target molecules, with its fluorescence intensity varying in accordance with the target concentration. A series of experiments were carried out to investigate the fluorometric properties of the grafted polymer P. The results demonstrated that P exhibited selective interaction with Al3+ among the various metals tested. Using the fluorescence intensity ratio (I603 nm/I538 nm) of P, a good linear relationship was achieved for Al3+ concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 35.0 μM with a detection limit of 0.33 μM was obtained. Meanwhile, we employed the standard addition method for the quantitative analysis and detection of Al3+ in commercially available bottled water and tap water, achieving an ideal recovery rate.

1. Introduction

Aluminum is the most abundant metal in the Earth’s crust and is widely used aerospace and automotive industries [1]. However, its extensive use can harm the environment and living organisms [2]. High levels of Al3+ intake can lead to brain degeneration, memory loss, anemia, and even symptoms of dementia [3,4,5,6]. There are several methods to detect metal ions. Atomic absorption spectroscopy is good for detecting trace elements, offering high accuracy and selectivity, but it is slow and has a fixed detection range [7]. Atomic fluorescence spectroscopy is sensitive and straightforward but can face issues like stray light interference and fluorescence quenching [8]. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) allow for fast multi-element analysis with low detection limits, but they are expensive and can be affected by sample composition [9,10]. Fluorescence probe methods have gained popularity in fields like biology, chemistry, and medicine [11,12,13,14]. These methods are selective, sensitive, quick, and allow for visual detection, making them suitable for on-site testing. Unlike device sensors, they use light signals, which reduces harm to biological systems.

Compared to other transition metals (e.g., Cu2+ and Hg2+), Al3+ exhibits spectroscopic silence and poor coordination ability, which has resulted in slow progress in the development of Al3+ probes. Most Al3+ fluorescence probes utilize a single emission wavelength for fluorescence signals, either in the form of fluorescence enhancement or fluorescence quenching based on different mechanisms such as C=N isomerisation of Schiff Base [15], Intromolecular Charge Transfer (ICT) [16], Aggregation-induced Emission Enhancement (AIE) [17], Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) [18], etc. For example, Jundong successfully designed and synthesized an enhanced fluorescent probe based on phenolphthalein by inhibiting PET, which was capable of selectively detecting trace amounts of Al3+. However, this probe can only detect Al3+ in single media such as dimethyl sulfoxide or ethanol and was susceptible to competitive interference from ions including Ni2+, Hg2+, Fe3+ and Cu2+ [19]. Weitao successfully synthesized a quenching-type fluorescent probe for Al3+ using o-phenylenediamine as the precursor and citric acid or boric acid as the regulator. The fluorescence quenching of o-GQDs by Al3+ may be related to the strong binding and fast chelation kinetics between the N and O functional groups and the ions of o-GQDs. A good linear relationship was observed between the concentration of Al3+ and the fluorescence intensity, but the detection range was relatively narrow (0–1.5 μM) [20]. It is well-documented that the changes in fluorescence signals may be influenced by other factors, such as solvent polarity, temperature variations, and pH, leading to results that are not sufficiently stable and reliable. In contrast, ratio-type fluorescence probes measure the ratio of two emission intensities at the same excitation wavelength [21]. Since both emissions are similarly influenced by external factors, their ratio cancels out some of the interference, making these probes more precise and less prone to errors. Currently, there are relatively a few ratiometric fluorescent probes for Al3+, and there are still significant deficiencies in key performance indicators. Jeya designed and synthesized a ratiometric fluorescent probe for the detection of Al3+/Fe3+ ions and successfully applied it to Hela cell imaging. However, this probe exhibited significant fluorescence interference from Al3+/Fe3+, and its fluorescence excitation wavelength was UV light at 280 nm [22]. Tian reported a ratiometric Al3+ fluorescent probe based on benzothiazole, which exhibited good selectivity, but had a relatively high detection limit of 4.39 µM, with shorter emission wavelengths at 478 nm and 525 nm [23]. In response to emerging application scenarios (such as Alzheimer’s disease research and real-time environmental monitoring), there is an urgent need to develop new ratiometric probes with longer emission wavelengths, higher sensitivity and stronger anti-interference capabilities. To address the aforementioned challenges and expand the practical applications of probes, some researchers have modified fluorescent sensing materials by introducing the natural product chitosan. Chitosan, a natural polysaccharide derived from crustacean shells [24], is an ideal carrier due to its exceptional biocompatibility and biodegradability [25]. These properties make it suitable for safe environmental and biological applications [26]. Additionally, the hydroxyl and amino groups in chitosan’s structure enhance the performance of small-molecule fluorescent probes [27]. Chitosan probes are promising candidates to overcome the limitations of these conventional small molecule-based ones. Specially designed chitosan-based sensing materials are typically constructed by incorporating multiple functional binding sites into their side chains or backbones. Therefore, chitosan-based probes could take advantage of the cooperative effects of multiple recognition sites to bind the low concentration analyte more efficiently, resulting in desirable signal amplification and fast fluorescence response. Additionally, it is also quite easy to incorporate hydrophobic sensing moieties into the water-soluble functional polymers by simple post-modification or copolymerization strategies, thus avoiding the use of toxic and volatile organic solvent in detection experiments. For example, He prepared three types of chitosan-BODIPY water-soluble fluorescent probes, which exhibited excellent sensing ability towards Hg2+/CH3Hg+ and high sensitivity (0.747/0.783 μM) [28]. Alavifar developed two fluorescent probes using chitosan functionalized with rhodamine B and coumarin derivatives, for efficient detection of Fe3+ and Zn2+, respectively [29]. These modified materials have been applied to the identification of metal ions, demonstrating satisfactory selectivity and sensitivity.

In our work, the design rationale for the Al3+ ratiometric probe was explained as follows: (1) To ensure to incorporate many functional binding sites, a ratiometric fluorescent probe was constructed by using chitosan as a carrier to link two fluorescent dyes. (2) Rhodamine-based dyes offer several advantages, including a high molar extinction coefficient, a high fluorescence quantum yield, and long excitation and emission wavelengths [30]. They also exhibit fluorescence modulation driven by the conversion between open-ring and closed-ring structures-a property we leveraged as the core of the target-responsive unit in our probe design [31]. (3) Naphthalimide-based dyes are versatile and can be modified by changing substituents at the 4th and 5th positions or on the nitrogen atom [32]. This modification creates an electron “push-pull” effect, allowing tuning of spectral properties. By introducing substituents at the 4th position, we can adjust the emission peak to the 510–530 nm range, enabling visible region emission.

In this study, we introduced a novel fluorescent material created by modifying chitosan with naphthalimide and rhodamine dye. We anticipated that this fluorescent material will serve as a ratiometric probe for analyzing Al3+ in environmental samples using fluorimetric methods. This design effectively mitigated interference from various environmental factors, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the analytical results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The chemicals and reagents used in the experiments were of analytical grade and required no additional purification. These reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) or Beijing InnoChem Science &Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Anhydrous ethanol, N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), hexane, ethyl acetate. 4-bromo-1,8-naphthalic anhydride (95%), hydrazine hydrate (85%), phenyl isothiocyanate (98%), rhodamine B (99%). The metal ion salts used included KCl (≥99.5%), MgCl2·6H2O (≥99.0%), CdCl2 (≥99.0%), CrCl2·6H2O (≥99.0%), HgCl2 (≥99.0%), CuCl2·2H2O (≥99.0%), FeCl3·6H2O (≥99.0%), PbCl2 (≥99.0%), ZnCl2 (≥99.0%), BaCl2·2H2O (99.5%), CoCl2·6H2O (99.0%), NiCl2·6H2O (≥99.0%), AgNO3 (≥99.8%) and AlCl3·6H2O (≥97.0%). The anionic species were derived from various salts, including NaI (≥99%), NaNO3 (≥99%), NaBr (≥99%), NaCl (≥99%), NaClO (≥99%), Na2CO3 (≥99.8%), Na2SO4 (≥99%), NaH2PO4 (≥99%) and Na2EDTA·2H2O (≥99%).

2.2. Instruments

Fluorescence spectra were recorded using a Hitachi F-4600 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Tokyo, Japan). UV-visible spectra were recorded with a HitachiU-2910 spectrophotometer (Tokyo, Japan). Nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were obtained with a Bruker AV 400 NMR instrument (Faellanden, Switzerland). Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were measured using a Nicolet Magna-IR 750 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Mass spectrometry analysis was conducted with a Thermo TSQ Quantum Access mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), coupled with an Agilent 1100 system (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Elemental analysis was used to determine the content of each element with a VarioELIII (Langenselbold, Germany) elemental analyzer.

2.3. Synthesis of P

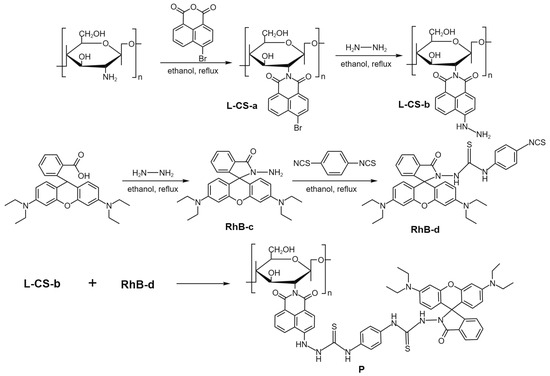

We designed a ratiometric fluorescent probe incorporating naphthalimide and rhodamine B, as illustrated in Scheme 1. Table S1 summarized the preparation formula of these compounds.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route of P.

L-CS-a: In a 250 mL round-bottom flask, 1.0013 g of low-density chitosan was dissolved in 200 mL of anhydrous ethanol along with 3.0185 g of 4-bromo-1,8-naphthalic anhydride (11.1 mmol). Under N2, the reaction was refluxed for 8 h. Upon completion, the mixture was immediately filtered, and the residue was washed several times with hot ethanol to remove any unreacted 4-bromo-1,8-naphthalic anhydride. The resulting product was then dried to yield a gray solid L-CS-a (1.97 g, 76% yield). IR (KBr, cm−1): IR (KBr, cm−1): 3383.10 (OH), 2925.08 (Ar–H), 1781.74, 1732.14 (C=O), 1588.04, 1570.53, 1503.98, 1457.89, 1402.24 (Ar), 1332.72, 1299.32, 1224.32, 1178.73, 1152.07, 1132.71, 1096.44, 1020.98 (C–O–C), 852.19, 774.15, 746.15, 718.99, 705.93 (Ar–H) (Figure S1).

L-CS-b: In a 100 mL round-bottom flask containing 0.5014 g of freshly prepared ethanol solution of L-CS-a, 20 mL of excess hydrazine hydrate (85%, 8 mL) was added under stirring. The mixture was refluxed for 6 h. The solution gradually changed from a turbid brown mixture to a clear reddish-brown liquid, eventually leading to the precipitation of reddish-brown solid. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered, and the solid was washed three times with ethanol. The product was then dried in an oven at 60 °C to yield reddish-brown solid L-CS-b (0.37 g, 83% yield). 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, δppm): 11.516 (s, 1H), 11.097 (s, 1H), 10.204 (s, 1H), 8.957 (s, 1H), 8.834 (d, 1H), 8.786 (s, 1H), 8.490 (d, 1H), 8.381 (d, 2H), 7.806 (t, 2H), 7.746 (t, 2H), 7.645 (d, 2H), 7.439 (t, 2H), 7.220 (t 2H), 6.994 (d, 2H), 6.962 (d, 1H), 6.899 (d, 2H), 6.866 (d,1H), 3.283 (s, 2H). IR (KBr, cm−1): 3359.50 (OH), 3235.0 (N–H), 2923.30 (Ar–H), 1641.80 (C=O), 1583.70, 1538.41, 1440.21, 1394.27 (Ar), 1364.80, 1259.03, 1239.26, 1076.02, 1013.81 (C–O–C), 891.56, 825.16, 769.03, 749.19 (Ar–H) (Figure S2).

RhB-d: In a solution of 200 mg of RhB-c [33] (0.47 mmol) in 1.5 mL of DMF, 125 mg of phenyl isothiocyanate (0.65 mmol) in DMF was added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 h, then the reaction was stopped by adding bottled water. The mixture was extracted with 10 mL of ethyl acetate, and the organic phase was collected and extracted three more times. The combined organic layers were concentrated using rotary evaporation, and the product RhB-d was purified by column chromatography with a solvent system of hexane and ethyl acetate (3:1, v:v) (0.18 g, 0.26 mmol, 57% yield). MS m/z: 704.84 [M + H]+, 702.84 [M − H+]−. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, δppm): 9.595 (s, 1H), 8.895 (s, 2H), 7.869 (d, 2H), 7.585 (t, 2H), 7.187 (s, 2H), 7.082 (d, 2H), 6.288 (d, 2H), 6.134 (d, 2H), 3.285 (m, 8H), 1.191 (s, 2H), 1.006 (t, 12H). IR (KBr, cm−1): 3324.65 (N–H), 2959.87, 2923.88 (Ar–H), 2092.29, 1711.24 (C=O), 1633.19 (C=S), 1613.35 (C=N), 1516.41, 1465.49, 1427.79, 1402.42, 1354.45 (Ar), 1306.97, 1265.65, 1220.27, 1119.57, 1075.64, 1017.13 (C–O–C), 974.19, 929.31, 820.99, 783.08, 756.66, 700.60 (Ar–H) (Figures S3 and S4).

P: Dissolve 20 mg of L-CS-b in 3 mL of dry DMF, and then mix it with 4 mL of anhydrous ethanol containing RhB-d. The mixture was stirred at reflux for 6 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Place the crude product in a Soxhlet extractor and purify it with ethanol as the eluent for 6 h to remove unreacted RhB-d. Finally, filter and dry the product to obtain a purple-black solid P (0.029 g, 51% yield). Elemental Analysis (%): C, 49.08; H, 5.53; N, 10.72; S, 2.24. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, δppm): 10.915 (s, –NH), 8.485 (b, –ArH), 8.087 (s, –ArH), 7.826 (d, –ArH), 7.530 (t, –ArH), 7.244 (d, –ArH), 6.976 (d, –ArH), 6.311 (t, –ArH), 5.733 (b, –CH), 4.411 (t, –CH2), 3.581 (m, –CH2), 3.293 (m, –CH2), 1.250 (d, –CH2), 1.099 (t, –CH3). IR (KBr, cm−1): 3348.66 (O–H), 3086.51 (N–H), 2971.59 (Ar–H), 1684.52 (C=O), 1648.84 (C=S), 1633.41 (C=N), 1615.09, 1589.51, 1512.70, 1413.26, 1337.78 (Ar), 1271.51, 1245.14, 1180.06, 1119.46, 1074.56 (C–O–C), 922.34, 821.80, 779.75, 702.55, 683.88 (Ar–H) (Figure S5).

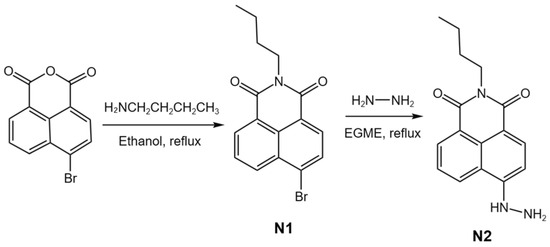

As a model compound, N2 was synthesized according to our reported study as shown in Scheme 2 [34,35].

Scheme 2.

Synthetic route of N2.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fabrication and Characterization of Dye-Modified Chitosan Materials

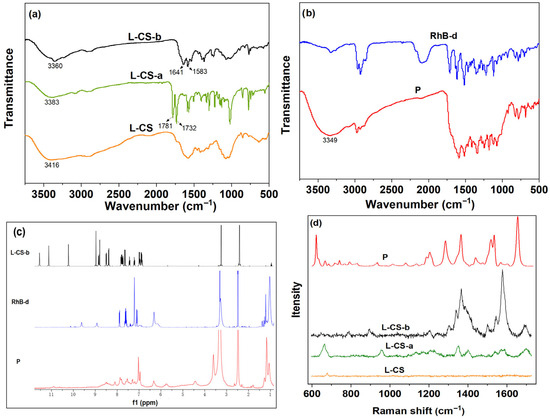

Following the successful grafting of the naphthalimide group onto L-CS, L-CS-a exhibited a characteristic carbonyl absorption peak at 1732 cm−1 and 1781 cm−1, confirming the success of the modification. After the introduction of the hydrazine group, an increase in conjugation was observed, resulting in a blue shift of the carbonyl absorption peak in L-CS-b to 1641 cm−1. Additionally, a characteristic absorption peak for –NH2 emerged at 3416 cm−1 (Figure 1a). These findings collectively indicated the successful synthesis of L-CS-b. Upon the interaction of RhB-d with L-CS-b, a characteristic –OH absorption peak appeared at 3300 cm−1, further confirming the successful synthesis of P (Figure 1b). In the 1H NMR spectrum of P (Figure 1c), the protons at approximately 1 ppm and 3.25 ppm originated from RhB-d, while the protons in the range of 6–8.5 ppm were attributed to the hydrogen atoms of the benzene rings in L-CS-b and RhB-d. Figure 1d showed the Raman spectra of the relevant substances. Compared to L-CS, L-CS-a exhibited clear aromatic ring and imide features around 1580–1600 cm−1, 1700–1660 cm−1 and 1340–1370 cm−1, confirming the successful grafting of naphthalimide. Following the hydrazination reaction, the peak density in the ranges of 1660–1620 cm−1, 1350–1380 cm−1 and 1180–1260 cm−1 was more pronounced than that of L-CS-a, indicating the stable presence of the naphthalimide framework and enhanced electronic conjugation with the system after hydrazination, leading to an increase in Raman signal intensity. In comparison to L-CS-b, there was a significant increase in both overall peak density and intensity, demonstrating the successful incorporation of strong Raman scattering aromatic/conjugated chromophores (rhodamine) and their coexistence with naphthalimide-chitosan. These data indicated the formation of P. Figure S6 presented the UV-Vis spectra of L-CS-b, RhB-d and P. A broad absorbance band associated with the naphthalimide group was observed around 450 nm, indicating effective functionalization of the naphthalimide derivative with the chitosan polymer (L-CS-b). Similarly, a broad absorbance band corresponding to the rhodamine group was detected around 550–600 nm, demonstrating the successful grafting of rhodamine fluorogens to the chitosan polymer (P). Elemental analysis further validated the successful conjugation of L-CS-b and RhB-d for P synthesis: structurally, L-CS-b contains no sulfur-containing functional groups, while elemental analysis of P clearly detected a sulfur signal (S% = 2.24%)—a direct indication that RhB-d (the only sulfur-containing component in the reaction system) was successfully coupled to L-CS-b. According to the UV-Vis absorbance data obtained using the reported method (Figure S7) [36], compound N2 was used as a model compound to calculate the hydrazino-naphthalimide content of L-CS-b, which was found to be 31.5 wt %. Consequently, the grafting rate of bromo groups by hydrazine groups in L-CS-b was calculated to be 26.4%. Overall, the synthesis and characterization of dye-modified chitosan materials not only demonstrated the successful incorporation of the dye but also highlighted the potential applications of these materials in various fields, including biomedical, environmental samples.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of (a) LCS, LCS-a, LCS-b; (b) RhB-d, P; (c) 1H NMR spectra of LCS-b, RhB-d, P; (d) Raman spectra of LCS, LCS-a, LCS-b and P.

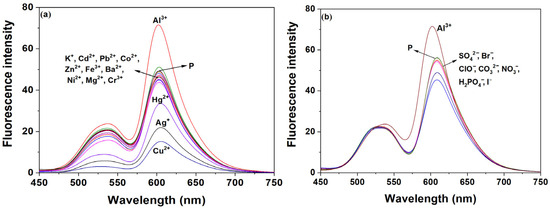

3.2. Characterization of Fluorescent Response of P

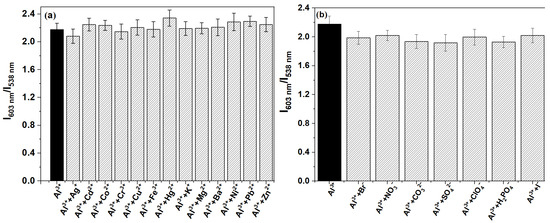

We first examined how acidity affected the fluorescence of probe P (Figure S8). The results showed that as the pH decreased, the fluorescence ratio (I603 nm/I538 nm) of the probe increased. After adding Al3+, the I603 nm/I538 nm ratio increased further and remained stable in the range of pH 4–6. However, when the pH exceeded 6, the fluorescence ratio decreased significantly. Therefore, EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES) was selected as the detection medium for P. Under the optimal condition, we examined the fluorescence spectral effects of probe P in the presence of 14 metal ions and 7 anions. As illustrated in Figure 2, the addition of Al3+ resulted in minimal change in the characteristic fluorescence peak of naphthalimide at 538 nm compared to other ions. However, the characteristic fluorescence peak of rhodamine B at 603 nm showed a remarked increase relative to the probe alone and the other ions. As shown in Table S2, the blank P exhibits a baseline ratio I603 nm/I538 nm of 2.28. Among all tested metal ions, only Al3+ induces a significant increase in the ratio (up to 3.32). This indicated that probe P selectively recognized Al3+, with the presence of Al3+ triggering the opening of the rhodamine B structure within probe P.

Figure 2.

Effects of different metal ions (20 μM) and anions (20 μM) on the fluorescence spectrum of probe P (30 ppm) in EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES). (a) metal ions, (b) anions.

3.3. The Influence of Al3+ Concentration on the Fluorescence Spectrum of P

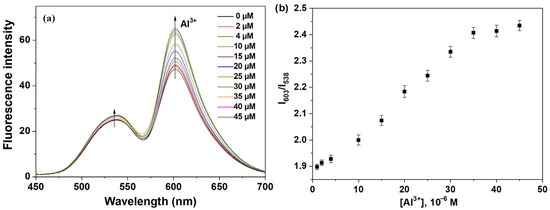

To further investigate the influence of Al3+ concentration on the fluorescence spectrum of probe P, we examined various concentrations of Al3+ (ranging from 0 to 45 μM) and their effects on the fluorescence intensity of the probe. As shown in Figure 3a, under single-wavelength excitation at λex = 430 nm, probe P exhibited dual fluorescence peaks at 538 nm and 603 nm, with the two peaks being relatively independent. The fluorescence intensity at 538 nm (I538 nm), associated with naphthalimide, remained largely unaffected by changes in Al3+ concentration, indicating that naphthalimide served as a stable internal standard, providing a reliable baseline. In contrast, the fluorescence intensity at 603 nm (I603 nm), corresponding to rhodamine B, progressively increased with higher Al3+ concentrations. This enhancement trend suggested a significant interaction between Al3+ and rhodamine B, leading to an increase in fluorescence signal. The ratio of I603 nm to I538 nm demonstrated a strong linear correlation with Al3+ concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 35.0 μM, fitting the equation: I603 nm/I538 nm = 0.0149c + 1.876 (R2 = 0.997). The limit of detection was determined to be 0.33 μM (calculated using 3s/k, where s is the standard deviation of the blank solution’s measured intensity and k is the slope of the plot shown in the inset of Figure 3b). The World Health Organization (WHO) specifies that the concentration of aluminum ions in drinking water should be limited to 200 µg/L (7.41 µM) [37]. This indicated that probe P can be effectively utilized for both qualitative and quantitative sensing of Al3+. The association constant (k) was calculated from the slope to be 5.01 × 104 M−1 (Figure S9), consistent with the Benesi-Hildebrand equation [38]. Overall, based on this, an internal standard ratiometric fluorescence probe was constructed, using naphthalimide as the reference signal and rhodamine B as the response signal for the quantitative detection of Al3+.

Figure 3.

(a) Fluorescence titration spectrum of P (30 ppm) in EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES) with varying concentrations of Al3+ (0–45 μM); (b) Fluorescence response of different concentrations of Al3+ (1–45 μM) to probe P (30 ppm).

3.4. Comparison of Performance in Recognizing Al3+

To assess the interference resistance of the ratio fluorescence probe P for detecting Al3+, we selected commonly found metal ions and anions to study their effects on the fluorescence spectrum of probe P in the presence of Al3+. As shown in Figure 4a, the presence of different metal ions (e.g., Fe3+, Cr3+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Cd2+, Ba2+, Co2+, Hg2+, Ni2+, K+, Ag+) at a concentration of 10 μM was shown to have minimal interference with the detection of Al3+. The fluorescence intensity ratio (I603 nm/I538 nm) remained stable, indicating that these metal ions did not significantly affect the recognition of Al3+ by P. Anions such as I−, Br−, ClO4−, NO3−, CO32−, H2PO4−, SO42− were also evaluated at a concentration of 10 μM (Figure 4b). Similar to the metal ions, these anions did not produce significant interference, as reflected in the consistent fluorescence intensity ratio (I603 nm/I538 nm) for the detection of Al3+. This indicated that these coexisting ions did not produce significant interference in the detection of Al3+, suggesting that the ratio fluorescence probe exhibited good interference resistance in the detection of Al3+.

Figure 4.

Interference of other ions (10 μM) coexisting in EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES) on the recognition of Al3+ (10 μM) by probe P (30 ppm): (a) metal ions, (b) anions.

In addition, under the aforementioned optimal experimental conditions, we utilized the standard addition method for the quantitative analysis and detection of Al3+ in commercially available bottled water and tap water. The results of the analysis were detailed in Table 1 and Figure S10. The recovery rates of spiked Al3+ in bottled water ranged from 96.36% to 104.99%, with a relative standard deviation (RSD) between 1.42% and 2.40%. In tap water, the recovery rates of spiked Al3+ were between 88.21% and 109.48%, with an RSD ranging from 0.18% to 2.67%. These results indicated that the established method possessed good recovery rates and high reliability. Therefore, it was reasonable to infer that fluorescence probe P had significant practical applications for the analysis and detection of Al3+ in real-world samples. A comparison of Al3+ specific probes was presented in Table 2. Various types of probes, utilizing polymer materials [39,40,41,42], rhodamine [43,44,45], and naphthalimide [43,46] as raw materials, exhibited distinct characteristics and can be classified into ratiometric and single fluorescent probes. Some of these probes demonstrated good selectivity and sensitivity for detecting Al3+ [41,42] and were applied in various detection media [40,41]. However, most probes based on polymer materials tended to be single-type probes [40,41,42]. On the other hand, relatively stable ratiometric probes faced limitations in terms of sensitivity [39]. Probes constructed from small molecules encountered similar challenges, including being predominantly single-type probes [46], exhibiting low sensitivity [43,44,45,46], and having a restricted application scope [43,44,46]. In contrast, the functional fluorescent material P, derived from chitosan, was categorized as a ratiometric probe and demonstrates exceptional selectivity, high sensitivity, and a wide linear detection range.

Table 1.

Determination of Al3+ in sample water with P (n = 3).

Table 2.

Performances comparison of reported fluorescent probes for Al3+.

3.5. Recognition Mechanism of P with Al3+

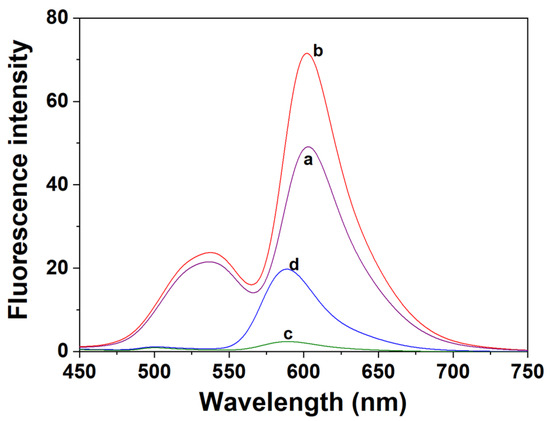

The binding reversibility of probe P with Al3+ was investigated. As shown in Figure 5, the addition of EDTA, a strong chelator, caused Al3+ to dissociate from P and resulted in decreased fluorescence intensity at 603 nm. When Al3+ was reintroduced, the intensity at 603 nm was restored or even enhanced, confirming the reversible binding of P to Al3+. This reversible “enhancement-quenching-recovery” cycle confirms that the interaction between P and Al3+ is a dynamic coordination process, ruling out irreversible covalent reactions and providing a basis for subsequent mechanistic dissection. To pinpoint the functional unit responsible for Al3+ recognition and the origin of fluorescence enhancement, fluorescence spectra of RhB-d, P, and their respective Al3+ complexes were measured under P’s optimal detection conditions (EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES), λₑₓ = 430 nm), with results presented in Figure 6. For free RhB-d (c in Figure 6), extremely weak fluorescence was observed—a typical feature of spirocyclic rhodamine derivatives, indicating that its spirolactam ring is predominantly closed, and no continuous π-conjugation system is formed in the xanthene moiety to support fluorescence emission [43]. Upon adding Al3+, a distinct characteristic emission peak of rhodamine B appeared at 589 nm (d in Figure 6), this peak’s intensity showed a concentration-dependent increase with Al3+, confirming that Al3+ directly triggers the opening of RhB-d’s spirolactam ring (Figure S11). This ring-opening process forms a highly delocalized π-conjugated structure, which is the core reason for the fluorescence “turn-on” response [44]. Moreover, the absence of fluorescence quenching or peak splitting during this process implies that the interaction between RhB-d and Al3+ is intramolecular. For probe P, weak dual emission peaks were observed in its free state: a peak at 538 nm attributed to the naphthalimide moiety (from L-CS-b) and a peak at 603 nm (red-shifted by 14 nm compared to RhB-d’s Al3+-responsive peak at 589 nm) originating from the rhodamine B moiety (a in Figure 6). This red shift is caused by the electron-donating effect of the chitosan backbone and the steric constraints of the grafted structure, which jointly modulate the π-conjugation degree of the rhodamine unit [29]. After adding Al3+, the fluorescence intensity at 603 nm increased significantly (b in Figure 6), while the 538 nm peak remained nearly unchanged—directly reflecting that the rhodamine moiety is the responsive unit for Al3+, and the naphthalimide moiety is not involved in Al3+ binding.

Figure 5.

Reversibility of P-Al3+ system was investigated in EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES). a. P (30 ppm); b. P (30 ppm) + Al3+ (10 μM); c. P (30 ppm) + Al3+ (10 μM) + EDTA (10 μM); d. P (30 ppm) +Al3+ (10 μM) + EDTA (10 μM) + Al3+ (20 μM).

Figure 6.

Fluorescence spectra of P and RhB-d (both under EtOH-H2O Solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES) with λₑₓ = 430 nm) before and after interaction with Al3⁺. a. P (30 ppm); b. P (30 ppm) + Al3⁺ (20 μM); c. RhB-d (10 μM); d. RhB-d (10 μM) + Al3⁺ (20 μM).

To further clarify the role of each component in Al3+ recognition, the selectivity of L-CS-b (the naphthalimide-grafted chitosan precursor), N2 (the small-molecule naphthalimide model compound), and RhB-d toward common metal ions was compared (Figure S12). As shown in the spectrum of L-CS-b (Figure S12a), it exhibits a similar fluorescence enhancement toward Hg2+, Ag+, and Al3+ at the characteristic emission wavelength of naphthalimide. Consistently, N2 (Figure S12b) also shows non-selective fluorescence responses to multiple metal ions (including Hg2+ and Ag+) when tested alone, confirming that the naphthalimide moiety itself lacks specific Al3+ recognition ability. This non-selectivity indicates that the naphthalimide moiety alone (whether as N2 or grafted to chitosan as L-CS-b) is incapable of distinguishing Al3+ from other heavy metal ions and thus cannot serve as an effective recognition unit for Al3+. Instead, in probe P, it functions as a passive internal standard—while it responds to multiple metal ions individually, its fluorescence (at 538 nm) remains relatively stable in P because Al3+ preferentially binds to the rhodamine moiety, and the chitosan backbone shields the naphthalimide from non-specific interactions. The selectivity spectrum of RhB-d (Figure S12c) shows that within its rhodamine-derived emission wavelength range (580–600 nm), this species exhibits fluorescence responses to Ag+, Hg2+, Al3+, and Fe3+ to varying degrees. Like N2 or L-CS-b, RhB-d alone fails to selectively recognize Al3+. It is only when L-CS-b and RhB-d are covalently linked to chitosan that P gains specific Al3+ selectivity—a modulation enabled by the polymeric environment of chitosan. The chitosan backbone grafts L-CS-b and RhB-d at distinct sites, enabling Al3+ to preferentially interact with RhB-d. The rigid structure of chitosan also limits the accessibility of other interfering ions to RhB-d, further enhancing the selectivity. Meanwhile, the naphthalimide moiety in P (derived from L-CS-b) emits stable fluorescence at 538 nm, serving as an internal standard to calibrate the rhodamine-derived response signal (603 nm). This ratiometric design (I603 nm/I538 nm) eliminates false signals arising from non-specific interactions of L-CS-b or RhB-d with other ions, ensuring that only the Al3+-induced changes in the rhodamine signal are quantified.

The method of continuous variation (Job’s plot, Figure S13) was employed to determine the stoichiometry of the RhB-d+Al3+ complex, with results indicating a 1:1 binding ratio. This finding further supports a 1:1 stoichiometry between a single polymer unit of P and Al3+. Additionally, after continuous illumination for 0.5 h, the fluorescence intensity of L-CS-b in ethanol exhibited no significant changes (Figure S14a). Furthermore, the effect of temperature on the performance of L-CS-b was investigated (Figure S14b) at three different temperatures: 25 °C, 35 °C and 45 °C. The results demonstrated that L-CS-b maintained relatively stable fluorescence intensity across these temperature variations. This robust photostability indicates that L-CS-b was well-suited to serve as an internal standard.

Collectively, the binding mechanism of P with Al3+ is proposed as follows (Scheme 3): In the free state of P, the rhodamine moiety exists predominantly in the spirolactam closed form (weak 603 nm fluorescence), and the naphthalimide moiety emits stable 538 nm fluorescence. When Al3+ is present, it specifically coordinates with the thiourea N and spirolactam O of rhodamine moiety, triggering spirolactam ring-opening to form a delocalized π-conjugated xanthene structure—this causes a enhancement of 603 nm fluorescence. Meanwhile, the chitosan backbone enhances P’s selectivity via steric shielding (blocking interfering ions from accessing the naphthalimide moiety) and improves water solubility via its hydroxyl/amino groups. The naphthalimide moiety, unaffected by Al3+, provides a stable internal standard signal, enabling ratiometric detection (I603 ₙₘ/I538 ₙₘ) to enhance the reliability of quantitative analysis.

Scheme 3.

Proposed binding mode between P and Al3+.

4. Conclusions

This study designed a ratiometric fluorescence probe with internal standards, which not only enhanced the probe’s selectivity and sensitivity but also improved the reliability of quantitative analysis. By incorporating chitosan, the detection sensitivity was increased, and the Stokes shift was further enhanced. P demonstrated selective ratiometric detection of Al3+ in EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES), exhibiting good anti-interference performance. When applied to the detection of Al3+ in real water samples, the spiked recovery rate ranged from 88.21% to 109.48%, with a relative standard deviation of 0.18% to 2.67%, confirming the accuracy and feasibility of the method.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemistry7060193/s1, Figure S1: FT-IR spectra of L-CS-a; Figure S2: FT-IR spectra of L-CS-b; Figure S3: ESI-MS spectra of RhB-d; Figure S4: FT-IR spectra of RhB-d; Figure S5: FT-IR spectra of P; Figure S6: UV-Vis spectra of the L-CS-b, RhB-d and P; Figure S7: (a) UV-Vis spectra of the model compound N2 at different concentrations. (b) The absorbance of N2 solutions at 447 nm versus its concentration. (c) UV-Vis spectra of the L-CS-b at different concentrations; Figure S8: Effect of pH for probe P for Al3+; Figure S9: Benesi-Hildebrand plot of P, assuming 1:1 stoichiometry for association between P and Al3+; Figure S10: The calibration graph for water sample. (a) bottled water; (b) tap water; Figure S11: Fluorescence titration spectrum of RhB-d (10 μM) in EtOH with varying concentrations of Al3+ (0-20 μM); Figure S12: Effects of different metal ions (20 μM) on the fluorescence spectrum of L-CS-b (30 ppm) in EtOH-H2O solution (9:1, v:v, pH 6.0, 20 mM HEPES), N2 and RhB-d in EtOH. (e.g., Fe3+, Cr3+, Al3+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Cd2+, Ba2+, Co2+, Hg2+, Ni2+, K+, Ag+); Figure S13: Job’s test on RhB-d to Al3+. The total concentration of RhB-d and Al3+ was 50 μM; Figure S14: Stability testing of L-CS-b in EtOH. (a) photostability tests of L-CS-b (30 ppm); (b) Effect of temperature (25 °C, 35 °C and 45 °C) for L-CS-b (30 ppm); Table S1: Synthetic formula of four compounds; Table S2: Fluorescence intensity ratio (I638 nm/I538 nm) of P under the presence of different metal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and validation, M.Y.; Resources and writing—original draft, S.W.; Conceptualization and data curation, J.Z.; software and data curation, X.L.; supervision and project administration, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (No. ZDYF2022SHFZ307, No. ZDYF2022SHFZ076), Academic Enhancement Support Program of Hainan Medical University (No. XSTS2025127, XSTS2025192), Colleges and Universities Scientific Research Projects of the Education Department of Hainan Province (NO. Hnky2023-26).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Omiyale, B.O.; Olugbade, T.O.; Abioye, T.E.; Farayibi, P.K. Wire arc additive manufacturing of aluminium alloys for aerospace and automotive applications: A review. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 38, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.T.; Hu, N.J.; Fu, Q.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Ren, Y.M.; Ye, X.; Lai, N.W.; Chen, L.S. Effects of aluminum (Al) stress on nitrogen (N) metabolism of leaves and roots in two Citrus species with different Al tolerance. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334, 113331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meder, D.; Siebner, H.R. Spectral signatures of neurodegenerative diseases: How to decipher them? Brain 2018, 141, 2241–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholy, A.A.; El Kholy, E.A.; Al Abdulathim, M.A.; Abdou, A.H.; Karar, H.A.D.; Bushara, M.A.; Abdelaal, K.; Sayed, R. Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women and the impact of clinical pharmacist counseling on their awareness level: A cross sectional study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Sato, D.; Notomi, M. Damping properties of pre-stressed shape-memory polymer sandwich beam. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Tec. 2022, 64, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, H.N.; Ahmed, K.A. Protective role of functional food in cognitive deficit in young and senile rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 2020, 31, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakayode, S.O.; Walgama, C.; Narcisse, V.E.F.; Grant, C. Electrochemical and colorimetric nanosensors for detection of heavy metal ions: A review. Sensors 2023, 23, 9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulthana, S.F.; Iqbal, U.M.; Suseela, S.B.; Anbazhagan, R.; Chinthaginjala, R.; Chitathuru, D.; Ahmad, I.; Kim, T.H. Electrochemical sensors for heavy metal ion detection in aqueous medium: A systematic review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25493–25512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmizadeh, H.; Soleimani, M.; Faridbod, F.; Bardajee, G.R. A sensitive nano-sensor based on synthetic ligand-coated CdTe quantum dots for rapid detection of Cr (III) ions in water and wastewater samples. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2018, 296, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surucu, O. Trace determination of heavy metals and electrochemical removal of lead from drinking water. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 4227–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collot, M.; Pfister, S.; Klymchenko, A.S. Advanced functional fluorescent probes for cell plasma membranes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 69, 102161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.J.; Qin, W.; Qin, Y.F.; Hu, G.Y.; Xing, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.T. A ratiometric fluorescence probe for visualized detection of heavy metal cadmium and application in water samples and living cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, F.; Mohajeri, N.; Zarghami, N. Targeted design of green carbon dot-CA-125 aptamer conjugate for the fluorescence imaging of ovarian cancer cell. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 80, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, F.M.; Xiong, T.D.; Wang, W.J.; Pan, J.X.; Shi, H.H.; Zhao, Y. A simple Schiff Base as fluorescent probe for detection of Al3+ in Aqueous Media and its application in cells imaging. J. Fluoresc. 2023, 33, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.Y.; Wang, J.L.; Huang, J.H.; Chen, X.F.; Zong, Z.A.; Fan, C.B.; Huang, G.M. A significant fluorescence turn-on probe for the recognition of Al3+ and its application. Molecules 2022, 27, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.C.; Niu, W.J.; Lin, Z.Q.; Cui, Y.H.; Tang, X.; Li, Y.J. A novel “turn-off” fluorescent sensor for Al3+ detection based on quinolinecarboxamide-coumarin. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 121, 108168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalishin, M.N.; Gamov, G.A.; Nikitin, G.A.; Pimenov, O.A.; Aleksandriiskii, V.V.; Isagulieva, A.K.; Shibaeva, A.V. A simple vitamin B6-based ffuorescent chemosensor for selective and sensitive Al3+ recognition in water: A spectral and DFT study. Microchem. J. 2024, 197, 109791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, X.Y.; Yang, W.Q.; Zhang, A.G.; Qu, Z.H.; Fu, H.Y.; Ma, M.L. A fluorescent probe for the detection of Al (III) based on a novel unsymmetrical trisubstituted 1,3,5-triazine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2024, 457, 115923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.D.; Hu, K.; Wang, H.B.; Sun, W.W.; Han, L.; Li, L.H.; Wei, Y. A novel multi-purpose convenient Al3+ ion fluorescent probe based on phenolphthalein. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1271, 134085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.T.; Zhang, L.M.; Jiang, N.J.; Chen, Y.Q.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.H.; Yang, B.S.; Liu, J.L. Fabrication of orange fluorescent boron-doped graphene guantum dots for Al3+ ion detection. Molecules 2022, 27, 6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.X.; Xu, J.W.; Song, Z.; Dai, Z.Y. Advancements in ESIPT probe research over the past three years based on different fluorophores. Dye. Pigment. 2024, 224, 111994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, J.S.; Sepperumal, M.; Balasubramaniem, A.; Ayyanar, S. A novel pyrazole bearing imidazole frame as ratiometric fluorescent chemosensor for Al3+/Fe3+ ions and its application in HeLa cell imaging. Spectrochim. Acta A 2020, 230, 117993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.N.; Wu, D.Q.; Sun, X.J.; Liu, T.T.; Xing, Z.Y. A benzothiazole-based fluorescent probe for ratiometric detection of Al3+ and its application in water samples and cell imaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, S.; Seth, A.; Gupta, P.; Nandi, G.; Dutta, R.; Jana, S.; Jana, S. Chitosan derivatives as carriers for drug delivery and biomedical applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 2181–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deineka, V.; Sulaieva, O.; Pernakov, N.; Radwan-Praglowska, J.; Janus, L.; Korniienko, V.; Husak, Y.; Yanovska, A.; Liubchak, I.; Yusupova, A.; et al. Hemostatic performance and biocompatibility of chitosan-based agents in experimental parenchymal bleeding. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 120, 111740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.C.; Wang, M.Y.; Huang, L.; Qin, D.; Cheng, X.J.; Chen, X.G. Evaluation of structure transformation and biocompatibility of chitosan in alkali/urea dissolution system for its large-scale application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, E.M.; Abusaif, M.S.; Abdel-Baky, Y.M.; Ragab, A.; Omer, A.M.; Ibrahim, I.; Ammar, Y.A. Insight into divergent chemical modifications of chitosan biopolymer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Li, C.W.; Cheng, X.J. Water soluble chitosan-amino acid-BODIPY fluorescent probes for selective and sensitive detection of Hg2+/Hg+ ions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 295, 127081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavifar, S.M.; Golshan, M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Salami-Kalajahi, M. Rhodamine B- and coumarin-modified chitosan as fluorescent probe for detection of Fe3+ using quenching effect. Cellulose 2024, 31, 3015–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.X.; Yan, B.Y.; Meng, J.T.; Ran, M.G.; Zhou, Y.T.; Deng, J.F.; Li, C.J.; Yao, Q.L. Study of rhodamine-based fluorescent probes for organic radical intermediates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 4059–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Yan, F.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Kong, D.P.; Ye, Q.H.; Xu, J.X.; Chen, L. Rhodamine-based ratiometric fluorescent probes based on excitation energy transfer mechanisms: Construction and applications in ratiometric sensing. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 50732–50760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.Y.; Meng, X.; Wang, L.Z.; Zhou, J.H.; Qin, D.W.; Duan, H.D. A naphthalimide-based fluorescent probe for the detection and imaging of mercury ions in living cells. Chem. Open 2021, 10, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Chen, L.X. Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric and off-on fluorescent probe for Cu2+ based on rhodamine derivative. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 5277–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.L.; Gong, R.; Ma, Q.; Sun, Y.M.; Fu, E.Q. A novel colorimetric and fluorescent chemosensor: Synthesis and selective detection for Cu2+ and Hg2+. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 5525–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Tian, H.; Wang, Z.H.; Chen, K.; Hill, J.; Lane, P.A.; Rahn, M.D.; Fox, A.M.; Bradley, D.D.C. Synthesis and luminescence properties of novel ferrocene–naphthalimides dyads. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 645, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Xiao, P.; Liu, Z.; Gu, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, T. Reaction-driven self-assembled micellar nanoprobes for ratiometric fluorescence detection of CS2 with high selectivity and sensitivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 20100–20109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Rodríguez-Cáceres, M.I.; Agbaria, R.A.; Warner, I.M. Fluorescence of metal–ligand complexes of mono-and di-substituted naphthalene derivatives. J. Fluoresc. 2005, 15, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jang, G.; Lee, T.S. Carbon nanodots functionalized with rhodamine and poly (ethylene glycol) for ratiometric sensing of Al ions in aqueous solution. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 249, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Mohiuddin, I.; Kaur, K.; Singh, R.; Kaur, V. Fluorescent Co/Al-layered double hydroxide intercalated Schiff base-chitosan composite for sensing multiple e-waste metals. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 106986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.C.; Zhang, Z.L.; Meng, Z.Y.; Qian, C.; Li, M.X.; Wang, Z.L.; Yang, Y.Q. A highly specific chalcone derivative grafted ethylcellulose fluorescent probe for rapid and sensitive detection of Al3+ in actual environmental and food samples. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 252, 126475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, X.X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, C.W. Construction of water-soluble fluorescent probes supported by carboxymethyl chitosan. Spectrochim. Acta A 2025, 329, 125507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.C.; Fu, Z.H.; Tian, L.M.; Yang, Z.Y. Study on synthesis and fluorescence property of rhodamine-naphthalene conjugate. Spectrochim. Acta A 2020, 229, 117868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, B.; Li, C.; Yang, Z. A novel chromone and rhodamine derivative as fluorescent probe for the detection of Zn (II) and Al (III) based on two different mechanisms. Spectrochim. Acta A 2018, 204, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, A.; Sain, D.; Guchhait, N.; Goswami, S. FRET based selective and ratiometric detection of Al (III) with live-cell imaging. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 14266–14271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahfad, N.; Mohammadnezhad, G.; Meghdadi, S.; Farrokhpour, H. A naphthylamide based fluorescent probe for detection of Al3+, Fe3+, and CN− with high sensitivity and selectivity. Spectrochim. Acta A 2020, 228, 117753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).