Abstract

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) imposes additional demands and obligations on service providers that handle and process personal data. In this paper, we examine how advanced cryptographic techniques can be employed to develop a privacy-preserving solution for ensuring GDPR compliance in Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems. The primary objective is to ensure that sensitive data from IIoT devices is encrypted and accessible only to authorized entities, in accordance with Article 32 of the GDPR. The proposed system combines Decentralized Attribute-Based Encryption (DABE) with smart contracts on a blockchain to create a decentralized way of managing access to IIoT systems. The proposed system is used in an IIoT use case where industrial sensors collect operational data that is encrypted according to DABE. The encrypted data is stored in the IPFS decentralized storage system. The access policy and IPFS hash are stored in the blockchain’s smart contracts, allowing only authorized and compliant entities to retrieve the data based on matching attributes. This decentralized system ensures that information is stored encrypted and secure until it is retrieved by legitimate entities, whose access rights are automatically enforced by smart contracts. The implementation and evaluation of the proposed system have been analyzed and discussed, showing the promising achievement of the proposed system.

1. Introduction

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) revolutionized industries by empowering machines, sensors, and other equipment to collect and exchange vast amounts of sensitive data [1]. However, with such additional connectivity come numerous security and privacy challenges, especially with the increasing importance of data coming from IIoT devices in supporting the functionality of industrial systems [2]. One of the most significant problems with IIoT systems is that sensitive information must be stored securely and access to it strictly controlled, in accordance with data protection laws, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [3]. Traditional security solutions, which typically rely on centralized models of access control, cannot serve in IIoT contexts due to the volume and nature of the network, which does not support maintaining control at its center. Never before have more robust, yet flexible and decentralized, security requirements been felt. Revolutionary cryptographic techniques, such as Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) and the use of blockchain technology, are significant solutions. ABE is an encryption that allows data to be securely stored and transmitted, with users being granted access based on pre-specified properties [4]. This means that sensitive information can be encrypted until it reaches the intended person or device, making unauthorized access impossible.

Decentralized Attribute-Based Encryption (DABE) [5] replaces the single managing entity with a set of distributed, independent attribute authorities. By integrating DABE with blockchain technology, it becomes possible to decentralize access control operations, ensuring that no single organization has complete control over who should access what data. Decentralization enhances transparency, security, and the robustness of the system. This paper aims to develop a privacy-preserving solution that utilizes DABE and blockchain technology to ensure IIoT systems are GDPR-compliant, specifically Article 32 [3], which requires organizations to implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure the confidentiality of personal data. The primary objective is to enforce security policies within IIoT systems automatically, with minimal human interaction, and to minimize the potential for compliance errors or security breaches. We also fill a significant gap by exploring how advanced cryptographic techniques are applied in IIoT systems, presenting a scalable, secure, and efficient method for protecting sensitive data and meeting regulatory requirements. The ultimate aim is to enhance the security, privacy, and trust of IIoT systems while enabling organizations to meet their legal obligations under GDPR [3].

With the above context in mind, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We design a framework that utilizes DABE and blockchain technology, offering GDPR-compliant data access control for IIoT systems.

- We utilize the blockchain architecture to ensure transparency and traceability of data access events, with automatic enforcement of data access policies by smart contracts. This eliminates the need for a central authority, enhancing system security and privacy.

- We utilize smart contracts to automate the enforcement of GDPR compliance, thereby reducing human error and enhancing the visibility and auditability of regulatory compliance.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 introduces various GDPR management techniques from the literature. Article 32 of the GDPR is briefly described in Section 3. The proposed framework is presented in Section 4. Section 5 presents the experimental procedure and the implementation details. Section 6 presents the observed results and their evaluation. Finally, a summary of this paper is provided in Section 7, along with some future directions.

2. Related Work

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) has transformed industrial operations by enabling interconnected devices to collect and exchange vast amounts of sensitive data [1]. However, this connectivity introduces significant security and privacy challenges [6], particularly in ensuring compliance with data protection regulations such as the GDPR [3]. Traditional centralized access control models struggle to meet the scalability and flexibility demands of IIoT systems. Advanced cryptographic techniques, such as ABE [4], combined with blockchain technology [7], offer decentralized, secure, and transparent solutions for data management. This literature review examines recent studies on access control in IoT networks, focusing on ABE and blockchain-based approaches for securing IIoT systems. It discusses their consideration in ensuring GDPR compliance, scalability, and decentralization. A comparative table is provided to summarize key features of each study.

Several studies have explored access control to address security and privacy challenges in IIoT systems. Hu et al. [8] proposed a secure aggregation scheme that aggregates the generated IoT data in a privacy-preserving approach, including the industrial data, to a centralized server. Hu et al. [9] proposed a fine-grained IoT data access control scheme that utilizes ABE as a central building block. Their framework uses ABE to enforce attribute-based access control, ensuring that only authorized users with matching attributes can decrypt data. Building on similar principles, Sasikumar et al. [10] developed a hierarchical ABE scheme integrated with blockchain for secure information sharing in IIoT. Their method supports multi-level access control, enabling fine-grained policy enforcement across complex industrial systems. Blockchain ensures decentralized and tamper-proof storage of access logs, enhancing transparency. Unlike our work, this model does not consider GDPR compliance when accessing data. Additionally, while a level of decentralization is achieved by using the hierarchical ABE scheme through the delegation of key generation, the root Private Key Generator (PKG) still has to generate the master key and delegate the key management operation to other PKGs.

Hussain et al. [11] proposed a real-time, lightweight cache algorithm that integrates blockchain for IoT access control. The blockchain stores the access policies, and the actual IoT data is stored in the cloud server. This approach enhances scalability and performance, making it suitable for large IoT networks. However, while it demonstrates efficient access control, the study does not explore GDPR compliance access control. Lee et al. [12] proposed a blockchain-based data access control and key agreement system for IoT environments. Their solution uses CP-ABE to enable fine-grained access control and secure data sharing. The proposed approach is scalable and efficient for resource-constrained devices, incorporating smart contracts for automated access management and leveraging off-chain decentralized storage to enhance system reliability and reduce on-chain data load. A single trusted authority in the proposed model manages the registration and key generation.

Roy and Ghosh [13] presented BloAC, a blockchain-based access control system for IoT environments. Their framework focuses on enhancing scalability and security by proposing an efficient and lightweight mechanism for managing access permissions across a wide range of IoT devices. BloAC leverages smart contracts to automate access control decisions, reducing the need for centralized authorities and improving system resilience against single points of failure. The use of blockchain ensures tamper-proof logging of access events, contributing to greater transparency and auditability. However, while the study significantly advances decentralized management and secure access control, it does not directly address the data protection obligations imposed by GDPR, which are critical in privacy-sensitive IoT applications.

Zaidi et al. [14] focus on an ABE-based access control framework for IoT, leveraging blockchain and smart contracts. Smart contracts automate access policy enforcement, thereby improving efficiency and reducing the need for human intervention. Despite its decentralized design, which utilizes the blockchain, the framework requires the data owner to generate the secret access keys. Morello et al. [15] specified a privacy-aware protocol for verifying compliance with regulations, with a focus on secure and decentralized verification of organizational attributes within clouds. DABE and Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) have been integrated into their framework to propose an Attribute Verification Protocol that guarantees a Prover (e.g., an organization) holds specific compliance-critical attributes without revealing them. The architecture mandates automatically enforced compliance checks by a decentralized ticketing system and is implemented in AWS using cloud-native building blocks. The effort directly responds to GDPR Article 32, and four sets of attributes map to its security requirements (e.g., pseudonymization, availability, periodical assessments). While it is not based on traditional blockchain infrastructure, it achieves decentralization through multiple Issuers and is designed for scalability and privacy. This makes the protocol particularly suitable for IIoT and cloud infrastructure that requires regulation-sensitive, fine-grained access control.

Table 1 provides a comparison of the features of the related works. To better understand the merits and drawbacks of the evaluated strategies, the following paragraphs outline the most significant features considered for comparison.

Table 1.

Key features of ABE and blockchain solutions for IIoT.

In the following, we provide a brief description of the key features that were introduced in Table 1.

- Data encryption: This feature assesses if the system ensures sensitive IIoT data is encrypted to prevent unauthorized access. Encryption systems, whether ABE or symmetric encryption, are crucial for data confidentiality.

- Fine-grained access control: This refers to the ability to enforce policies that provide fine-grained and dynamic access, allowing only a specified user with specific characteristics or credentials to view specific data. Fine-grained control is essential for adhering to privacy laws and minimizing the exposure of sensitive information.

- GDPR compliance: Solutions are assessed on the degree to which they directly provide mechanisms to satisfy GDPR requirements (e.g., as required by Article 32).

- Scalability: This factor considers the scalability of the system so that there is performance and security when there is a growth in devices and users. Scalable architectures are required for realistic deployment in large-scale IIoT applications.

- Resource efficiency: IIoT devices will be restricted in terms of computing and storage. Solutions are evaluated based on how efficiently they integrate into such configurations, with security features that do not consume excessive resources.

- No single managing/storage entity: This feature ensures that no entity in the system represents a single managing or storage entity. While the rest of the protocol may be decentralized, the existence of such an entity can introduce a single point of attack and failure in the system.

- Smart contract integration: This checks whether smart contracts are employed to automate access control or data management processes on the blockchain, reducing manual intervention and improving transparency and reliability.

- Off-chain decentralized storage: This feature evaluates the use of decentralized storage solutions, such as the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), to safely store large data files without congesting the blockchain, enhancing system scalability and efficiency.

3. GDPR Article 32

When an entity (e.g., a company branch) aims to access IIoT-generated private data, Article 32 of the GDPR (https://gdpr-info.eu/art-32-gdpr/ accessed on 27 April 2025) requires that the user has implemented “appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk.” This meant that the user had ensured “the ongoing confidentiality, integrity, availability and resilience of processing systems and services.” In practical terms, this can be achieved through measures such as encryption, access control, authentication, and logging. Article 32 sets out four main requirements, which can be translated into the following attributes:

- Attribute 1: Pseudonymization and encryption of personal data.

- Attribute 2: Ensuring ongoing confidentiality, integrity, availability, and resilience of processing systems and services.

- Attribute 3: The ability to restore availability and access to personal data quickly after a physical or technical incident.

- Attribute 4: A process for regularly testing, assessing, and evaluating the effectiveness of security measures.

Before an entity, such as a company branch, is granted access, the data owner must be assured that the entity can “regularly test, assess and evaluate the effectiveness of technical and organisational measures for ensuring the security of the processing.” Evidence such as security policies, contractual data processing agreements, or recognised certifications would serve to demonstrate compliance. The roles of controller and processor also must be clearly established, as responsibility for maintaining “a level of security appropriate to the risk” rests with both parties. In short, Article 32 requires that access is conditional upon provable safeguards being in place. The primary objective of this paper is to automate and integrate access control with GDPR compliance verification.

4. The Proposed Framework

The proposed framework combines the most advanced cryptographic techniques, such as DABE, blockchain technology, and smart contracts, to enable GDPR-compliant access control on IIoT platforms. DABE is used to facilitate fine-grained encryption of personal data, where the access policies are represented in ciphertext directly and are expressed in terms of attributes extracted from GDPR Article 32 requirements, such as encryption, pseudonymization, access control, and integrity mechanisms for data. By integrating these technologies, the framework guarantees greater confidentiality, integrity, and availability of IIoT data while being strictly compliant with GDPR regulations, particularly ensuring security, accountability, and user data protection.

4.1. Framework Architecture

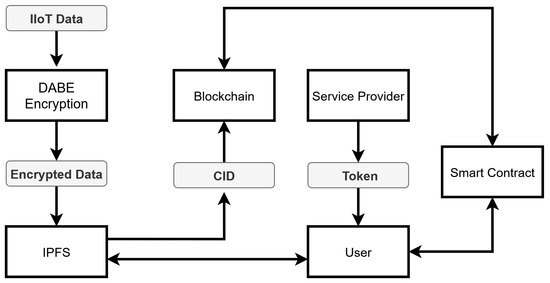

The architecture of the proposed framework integrates several aspects that collaborate to offer secure and GDPR-compliant access control. It starts with IIoT devices, which collect information from the real world and encrypt it to protect confidentiality. The encrypted data is stored securely via decentralized storage, ensuring its safety even in the event of system failure. The data is accessed by regulating it with smart contracts on a blockchain in such a way that only GDPR-compliant entities can access it based on their attributes. All elements of the system are structured to exchange information securely and efficiently, thereby safeguarding the information throughout the process. All these elements together constitute a secure environment that is GDPR-compliant in terms of security, transparency, and data privacy. An overview of the system architecture is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The architecture of the proposed system.

The sensors constantly collect real-time data, for instance, diagnostics data, location, velocity, and other operational parameters, which are required for controlling and monitoring. Due to data sensitivity, encryption is immediately applied once the data is collected to protect it against unauthorized use or interference. The encryption mechanism follows access rules that are customized according to the GDPR Article 32 characteristics; thus, only users possessing the required security set of properties can successfully decrypt and access the data. Such fidelity-based access ensures confidentiality and data integrity throughout their lifespan. Once encrypted, the information is stored in the distributed storage network, providing a decentralized, tamper-proof repository to enhance immunity to single points of failure. The blockchain is also an open and unalterable record containing metadata about every attempt to access the data, including user attributes, request date and time, and the success or failure of the request. This logging process not only enables real-time monitoring and audit capabilities but also enhances traceability and accountability, both of which are required under GDPR compliance regulations.

4.2. Integration with DABE

DABE is used for encrypting IIoT data. The encryption process ensures that only those entities who satisfy a defined set of attributes (aligned with GDPR requirements) can access the encrypted data. The DABE encryption mechanism is defined as follows:

Let M represent the data to be encrypted. In DABE, the encryption of M is performed based on a policy P that specifies the required compliance attributes for decryption. The encryption process is

where is the encryption function, is the public key of the system, and P is the set of compliance attributes that define the decryption policy. A user can decrypt the data only if their attributes match the compliance policy P. Decryption is performed using the user’s secret key , which various service providers generate based on the user’s attributes. The decryption function is

where is the decryption function, and C is the ciphertext.

4.3. Blockchain Integration

Blockchain technology is incorporated into the proposed framework to ensure that access requests are logged in a secure, decentralized, and immutable ledger. Each access request, along with its associated metadata, including timestamp, user attributes, and access status, is recorded on the Blockchain. The ledger provides transparency, ensuring that every access attempt is publicly verifiable and traceable. A typical transaction on the Blockchain can be represented as

where U represents the anonymized identifier of the user making the request, A represents the user’s compliance attributes, represents the timestamp of the request, P represents the compliance policy associated with the requested data and indicates whether the access was approved or denied. IPFS and Ethereum work together by storing encrypted data on IPFS and recording its unique Content Identifier (CID) on the Blockchain.

4.4. Smart Contract

The smart contract is deployed on the blockchain to enforce access control policies automatically. The contract is written in Solidity using the Foundry framework and implements authorization checks against attribute policies, emitting audit events. More specifically, it is an access-control contract that verifies the compliance attribute satisfaction and logs decisions (AccessLogged with user address, timestamp, policy, and result).

The CID on IPFS ensures data integrity, while the smart contract manages access and rules, together creating a secure and decentralized system for handling encrypted information. When a user attempts to access encrypted data, the contract verifies whether the user’s attributes satisfy the conditions specified by the compliance policy. Formally, the smart contract function is defined as

where U is the user, A is the set of compliance attributes associated with the user, and P is the compliance policy defined during encryption. The encrypted CID of IPFS is recorded in the smart contract. When the user U requests access to the data, the contract checks whether the user’s compliance attributes meet the defined policy. If they do, the encrypted CID is returned, allowing the user to retrieve the ciphertext from IPFS; if not, access is denied.

4.5. Cryptographic Protocol Design

This section describes the cryptographic components used in the proposed framework, with a particular focus on DABE encryption, key management, and access control mechanisms.

The core of the encryption process is based on DABE [5], where the data is encrypted based on a set of attributes. Key management in DABE involves an unlimited number of trusted and independent authorities that are authorized to generate compliance tokens for users. Upon joining the framework for the first time, an authority such as a cloud service provider generates its own public and private keys. The public key will later be used to create the ciphertext.

A user U, using its anonymized identity , requests a compliance ticket for each attribute i by contacting the corresponding service provider. The service provider then generates the user’s tickets, that is, the secret keys linked to those attributes. Each ticket associated with a given attribute serves as proof of possession of that attribute. This ticketing mechanism defines the role of the secret key as evidence of compliance with the corresponding regulatory requirement.

The decentralized design of the protocol assigns different service provider nodes the responsibility for generating different sets of tickets. This distribution of authorities across multiple service providers reduces reliance on a single central entity and significantly mitigates the risks typically found in centralized systems. Additionally, the system is fully aligned with the lightweight generation of the ciphertext by utilizing and integrating the sharing of the encryption process [16] or outsourcing the heavy computations [17], making it suitable for the resource-constrained nodes with low computation power.

4.6. GDPR Article 32 Compliance Mechanisms

The proposed framework ensures adherence to the GDPR in terms of secure data handling and access permissions in IIoT systems. The framework meets the GDPR’s requirements for confidentiality, integrity, and user rights, with a focus on protecting data in smart manufacturing system applications.

To check compliance with Article 32, each attribute must be verified. A user (e.g., a company branch) is considered compliant only if it meets all four attributes. In practice, this means the user requesting the data access must receive four validation tickets (secret keys for each attribute) from the Issuers (e.g., cloud providers). The compliance logic for each attribute can be defined as follows:

- Attribute 1: Pseudonymization and Encryption

- Pseudonymization technique: must be tokenization or masking.

- Encryption algorithm: must be an approved option such as AES, RSA, or ChaCha20.

- Key length: must meet minimum security standards, e.g., at least 128 bits for symmetric encryption or 2048 bits for asymmetric encryption.

- Attribute 2: Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability, and Resilience

- Security measures: must include mandatory items such as a firewall.

- Assessment frequency: at least quarterly.

- Vulnerabilities found: must remain below a set threshold (e.g., fewer than 5).

- Vulnerability severity: must not exceed acceptable levels (e.g., low or medium).

- Attribute 3: Data Restoration Capabilities

- Backup type: must be incremental or full.

- Backup frequency: must be daily or weekly.

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO): no more than 8 h.

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO): no more than 4 h.

- Attribute 4: Regular Testing and Evaluation

- Assessment frequency: must be monthly, quarterly, or yearly.

- Assessment type: must be an accepted method, such as vulnerability scanning, penetration testing, or a security audit.

- Assessment status: must be marked as passed.

- Last assessment date: must be within the last 18 months.

5. Implementation

To implement the proposed framework, and without loss of generality, the FABEO scheme introduced by Riepel and Wee was employed [18]. It provides efficient, pairing-based CP-ABE with optimal adaptive security and support for expressive access control policies. Based on that, we assumed one service provider that issues the four compliance tokens. In future implementations, these ABE implementations can be replaced by a DABE implementation. The deployment was carried out with the open-source code provided by the authors (https://github.com/DoreenRiepel/FABEO accessed on 3 February 2025), which served as a working and effective base to construct and test the encryption facilities within IIoT applications. To further enhance the security and scalability of the system, we augment this ABE solution with a decentralized storage network, utilizing IPFS to store the encrypted data.

Decentralized storage removes risks associated with centralized storage systems by offering enhanced resilience and availability. Additionally, data stored in IPFS remains completely encrypted, ensuring that even if the storage network is compromised, malicious nodes cannot access the confidential information. The data can only be retrieved by limiting the encrypted data, and this can only be carried out by the intended parties whose attributes satisfy the pre-configured requirements, through the use of the DABE scheme.

Currently, the system prototype (https://github.com/elte-cybersec/gdpr-compliant-IIoT accessed on 20 September 2025) encompasses four main components: (1) the ABE scheme that uses attributes to control access to encrypted data based on the GDPR Article 32 compliance, (2) encryption and decryption to secure data and ensure authorized decryption based on user attributes, (3) smart contracts to manage user access based on attributes stored on the blockchain, and (4) IPFS integration to store encrypted data off-chain for secure and decentralized access.

IPFS and Ethereum complement each other by combining decentralized storage with verifiable smart contract logic. Since storing ciphertext data directly on the blockchain is costly and inefficient, compared to storing it on IPFS, the encrypted and serialized ciphertext () is uploaded to IPFS, which returns a unique CID. This CID, a lightweight cryptographic reference, is then encrypted based on the compliance policy and stored in an Ethereum smart contract. The smart contract regulates the access, verification, and usage policies, while IPFS ensures decentralized and tamper-resistant storage. Together, this integration enables scalable, secure, and decentralized management of encrypted data.

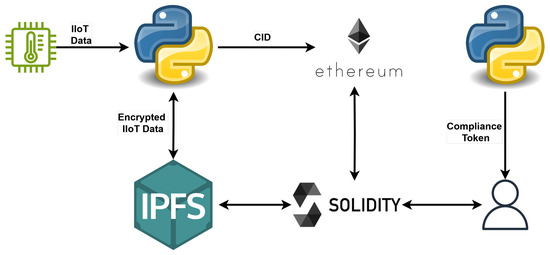

Figure 2 illustrates an overview of the framework architecture and the used technologies. The compliance token is generated by the service provider. To conduct the process of both encryption and decryption, we implemented Algorithms 1 and 2, respectively. We start by outlining some of the notations we use in the rest of the paper, as shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

The main components of the proposed framework.

Table 2.

List of notations.

On the one hand, Algorithm 1 illustrates the operation of the storage, where the essential inputs are the original IIoT data, , and the . The resulting is structured with various cryptographic components such as C0, which enforce the access control policy. The function encrypts the original IIoT data (msg) under the provided policy. The encryption ensures that only GDPR-compliant users with the right attributes can decrypt the data. After serialization, the is uploaded to IPFS for decentralized storage. Each element of the is serialized using the group.serialize function to enable it to be stored on IPFS.

| Algorithm 1 Encryption Process |

|

On the other hand, Algorithm 2 illustrates the operation of data access, where the essential inputs are the encrypted data , , and the secret key . The decrypt function checks if the set of attributes of a user matches the policy that is embedded in the . If the attributes meet the conditions, the is first decrypted to the CID of the stored , which is then decrypted. As a result, the original IIoT data will be recovered. To validate, we compare the decrypted message and the original message to verify successful decryption.

| Algorithm 2 Decryption Process |

|

The access control in the system is governed by the user’s attributes. These attributes determine whether a user can decrypt a message. Each user has a set of attributes, and the system checks if these attributes match the policy embedded in the ciphertext. A list of attributes is associated with each user. These attributes are used to generate a secret key for the user and are the basis for access control. Here is an example of a list of attributes: [‘DATACONTROLLER’, ‘ENCRYPTIONENABLED’, ‘ACCESSCONTROLENFORCED’, ‘PSEUDONYMIZATIONAPPLIED’, ‘TESTEDSECURITY’, ‘GDPRCOMPLIANT’]. The user’s secret key is generated based on their specific attributes, ensuring that only users with the right attributes can decrypt messages. In terms of the access control policy, a logical policy defines the required attributes for accessing a message. For example, a policy could specify that a user must have GDPRCOMPLIANT and ENCRYPTIONENABLED attributes to access the data.

To manage and enforce the access control policies on the blockchain, smart contracts are used. These contracts validate if a user has the required attributes and log access requests.

6. Evaluation

The system’s functionality and security are verified by testing the key generation, encryption, decryption, and compliant-based access control processes. Unit tests ensure that the system correctly handles various scenarios, including valid and invalid attributes, as well as correct logging of access attempts. The smart contract’s authorization functionality is tested using unit tests written in Solidity, utilizing the Foundry testing framework. These tests are essential to ensure that the access control logic correctly authorizes or denies entities based on their compliance tokens. The testing process validates the following key scenarios:

- Positive Authorization Test: ensures that users such as company branches possessing all required compliance tokens, such as GDPRCOMPLIANT, ENCRYPTIONENABLED, and ACCESSCONTROLENFORCED, are successfully authorized by the smart contract.

- Negative Authorization Test: validates that users missing critical attributes (e.g., only having ENCRYPTIONENABLED and ACCESSCONTROLENFORCED but lacking GDPRCOMPLIANT) are denied access, thus verifying the strict enforcement of attribute-based policies.

- Attribute Validation Logic: tests the validateUserAttributes function to confirm that string matching using the keccak256 hash function is accurate and prevents bypassing the policy through minor string variations.

- Access Event Logging: verifies that the AccessLogged event is emitted correctly with the user address, timestamp, policy description, and authorization result.

6.1. System Performance

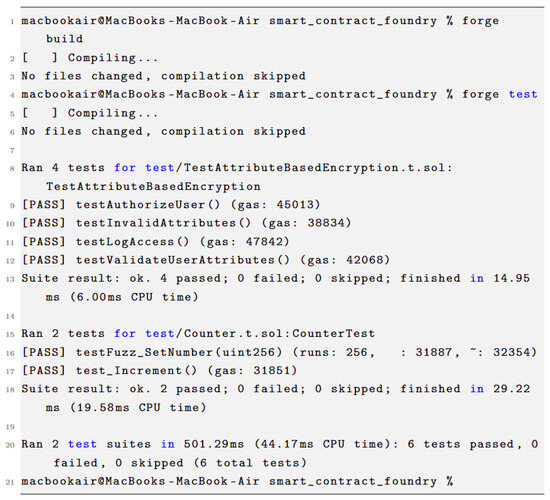

To measure the performance of the proposed system, we implemented the system components in a Linux Ubuntu v24.04 with Intel Core i7 CPU and 16 GB RAM. On the one hand, Figure 3 provides an example result from running the unit tests on the smart contract, demonstrating correct behavior for both successful and failed authorization attempts. These unit tests not only confirm the correctness of the authorization logic but also increase the overall trustworthiness of the decentralized access control model applied in the IIoT environment.

Figure 3.

Solidity test results using Foundry.

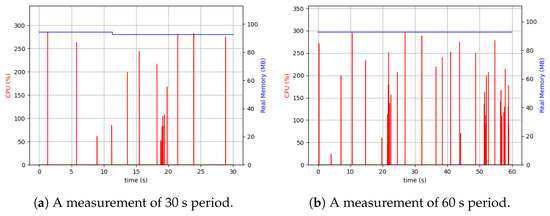

On the other hand, we collected a real-time performance measurement for the system at 30 and 60 s, respectively. Psrecord 1.4, which is a small Python utility library, was used to monitor both the CPU and memory activities of the system application and poll statistics from the Linux/proc file system. Figure 4 shows the obtained results, which reveal the trade-off between the speed and the memory consumption. Additionally, we measured the time required for processing Algorithms 1 and 2. The result shows a promising achievement since ∼ s (on average) is what the system requires to conduct both the encryption and the decryption operations.

Figure 4.

Total memory and processing load of the real-time deployment of the proposed system.

6.2. Security Analysis

In this section, we discuss the security of the proposed system and evaluate its resilience against common attacks, including Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks, impersonation attacks, and collision attacks. These types of attacks are particularly relevant in IIoT environments, where ensuring the integrity, confidentiality, and compliant processing of sensitive data is essential. The goal is to verify that the system can resist these threats while remaining compliant with the GDPR.

6.2.1. Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attack

An MITM attack involves an adversary intercepting communication between two legitimate parties. The attacker might attempt to read or manipulate the data in transit. In the proposed system, sensitive messages are encrypted using DABE, where the encryption function is defined as

Here, msg is the plaintext data, is the public key, and policy defines the access structure. The ciphertext can only be decrypted by a user who possesses a key such that their attribute set S satisfies

Without a valid , it is computationally infeasible for an attacker to derive the original message. Even if an attacker intercepts via network sniffing or packet injection, the semantic security of the underlying DABE scheme ensures

Additionally, storing encrypted data on IPFS and logging access through blockchain smart contracts adds tamper evidence and prevents data manipulation. The decentralized nature of IPFS also reduces the single point of failure that typically enables successful MITM attacks.

6.2.2. Impersonation Attack

Impersonation attacks occur when a malicious party impersonates a legitimate user to gain unauthorized access to protected data. In the proposed system, a user’s decryption capability is based on their attribute set S, not their identity alone. The key generation algorithm works as follows:

The attacker must obtain a secret key matching the attribute set required by the policy. This is only possible through access to the trusted authority that holds the private key, or by stealing the key. Both these cases are assumed to be infeasible in the model. The probability of successful impersonation, assuming secure key storage and distribution, is

Furthermore, incorporating external countermeasures such as multi-factor authentication (MFA) and access logging on the blockchain increases resistance to impersonation by adding a second layer of identity verification.

6.2.3. Collision Attack

A collision attack occurs when two users attempt to combine their attributes to decrypt a ciphertext that neither can decrypt individually. Let user A have the attribute set and user B have the attribute set . They merge their attributes into and use

However, in DABE, secret keys are generated with bound identities and cannot be arbitrarily combined. The encryption enforces policy evaluation at the key level:

Even if satisfies the policy, attacker cannot construct of two different entities:

Moreover, unauthorized key generation or data access attempts are logged via smart contracts on the blockchain, ensuring traceability and accountability. These logs act as audit trails to identify malicious behaviors, providing GDPR-aligned transparency.

Table 3 illustrates the system’s resistance to common security threats and attacks, including MITM, impersonation, and token collision attacks. Each attack is assessed on how well the system can detect, mitigate, and resist such threats.

Table 3.

Security analysis of the proposed system.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes a framework that ensures secure, GDPR-compliant data access in IIoT environments. By utilizing smart contracts for access control and IPFS for decentralized storage, the framework provides a robust solution for securing sensitive data while enabling flexible, policy-based access. The encryption and decryption processes, along with rigorous attribute validation, ensure that only GDPR-compliant entities (such as company branches) can access protected data, thereby meeting privacy and security requirements. Future work can include deep analysis of various blockchain implementations, consensus protocols, and other distributed parameters. Additionally, further formal studies can be performed on the attacks pertinent specifically to blockchain-enabled IIoT, such as request replay, front-running, attribute escalation or tampering with on-chain metadata.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.A.; methodology, M.B.A.; software, A.I.; validation, A.I., A.M. and M.B.A.; formal analysis, A.M. and M.B.A.; resources, A.I., A.M. and M.B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I. and M.B.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and M.B.A.; visualization, A.I. and M.B.A.; funding acquisition, M.B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by the EKÖP-24 University Excellence Scholarship Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the national research, development and innovation fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sisinni, E.; Saifullah, A.; Han, S.; Jennehag, U.; Gidlund, M. Industrial internet of things: Challenges, opportunities, and directions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 4724–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, T.; Ledwaba, L.P.I.; Eldefrawy, M.H.; Hancke, G.P.; Pereira, N.; Gidlund, M.; Akerberg, J. Security and Privacy in the Industrial Internet of Things: Current Standards and Future Challenges. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 152351–152366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Goyal, V.; Pandey, O.; Sahai, A.; Waters, B. Attribute-Based Encryption for Fine-Grained Access Control of Encrypted Data. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Alexandria, VA, USA, 30 October–3 November 2006; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewko, A.; Waters, B. Decentralizing attribute-based encryption. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Tallinn, Estonia, 15–19 May 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 568–588. [Google Scholar]

- Jhanjhi, N.; Humayun, M.; Almuayqil, S.N. Cyber security and privacy issues in industrial internet of things. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2021, 37, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadares, D.C.G.; Perkusich, A.; Martins, A.F.; Alshawki, M.B.; Seline, C. Privacy-preserving blockchain technologies. Sensors 2023, 23, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Luo, J.; Pu, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhao, R.; Huang, H.; Xiang, T. An efficient privacy-preserving data aggregation scheme for IoT. In Proceedings of the Wireless Algorithms, Systems, and Applications: 13th International Conference, WASA 2018, Tianjin, China, 20–22 June 2018; Proceedings 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huo, Y.; Ma, L.; Liu, H.; Deng, S.; Feng, L. An attribute-based secure and scalable scheme for data communications in smart grids. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wireless Algorithms, Systems, and Applications, Guilin, China, 19–21 June 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, A.; Ravi, L.; Devarajan, M.; Selvalakshmi, A.; Almaktoom, A.T.; Almazyad, A.S.; Xiong, G.; Mohamed, A.W. Blockchain-assisted hierarchical attribute-based encryption scheme for secure information sharing in industrial internet of things. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 12586–12601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.; Mansor, Z.; Shukur, Z.; Jafar, U. Ether-IoT: A Realtime Lightweight and Scalable Blockchain-Enabled Cache Algorithm for IoT Access Control. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 75, 3797–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Park, K.; Noh, S.; Bisht, A.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y. Blockchain-Based Data Access Control and Key Agreement System in IoT Environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Ghosh, S. BloAC: A Blockchain-Based Secure Access Control Management System for IoT. TechRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.Y.A.; Shah, M.A.; Khattak, H.A.; Maple, C.; Rauf, H.T.; El-Sherbeeny, A.M.; El-Meligy, M.A. An attribute-based access control for IoT using blockchain and smart contracts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, M.; Sainio, P.; Alshawki, M. Regulatory Compliance Verification: A Privacy Preserving Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th Cyber Security in Networking Conference (CSNet), Paris, France, 4–6 December 2024; pp. 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshawki, M.B.; Ligeti, P.; Reich, C. Sdabe: Efficient encryption in decentralized cp-abe using secret sharing. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET), Prague, Czech Republic, 20–22 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshawki, M.B.; Ligeti, P.; Reich, C. Poster: ODABE: Outsourced Decentralized CP-ABE in Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security, Rome, Italy, 20–23 June 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepel, D.; Wee, H. FABEO: Fast Attribute-Based Encryption with Optimal Security. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’22), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 7–11 November 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).