Abstract

In an increasingly interconnected world, cybersecurity professionals play a pivotal role in safeguarding organizations from cyber threats. To secure their cyberspace, organizations are forced to adopt a cybersecurity framework such as the NIST National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education Workforce Framework for Cybersecurity (NICE Framework). Although these frameworks are a good starting point for businesses and offer critical information to identify, prevent, and respond to cyber incidents, they can be difficult to navigate and implement, particularly for small-medium businesses (SMBs). To help overcome this issue, this paper identifies the most frequent attack vectors to SMBs (Objective 1) and proposes a practical model of both technical and non-technical tasks, knowledge, skills, abilities (TKSA) from the NICE Framework for those attacks (Objective 2). This research develops a scenario-based curriculum. By immersing learners in realistic cyber threat scenarios, their practical understanding and preparedness in responding to cybersecurity incidents is enhanced (Objective 3). Finally, this work integrates practical experience and real-life skill development into the curriculum (Objective 4). SMBs can use the model as a guide to evaluate, equip their existing workforce, or assist in hiring new employees. In addition, educational institutions can use the model to develop scenario-based learning modules to adequately equip the emerging cybersecurity workforce for SMBs. Trainees will have the opportunity to practice both technical and legal issues in a simulated environment, thereby strengthening their ability to identify, mitigate, and respond to cyber threats effectively. We piloted these learning modules as a semester-long course titled “Hack Lab” for both Computer Science (CS) and Law students at CSU during Spring 2024 and Spring 2025. According to the self-assessment survey by the end of the semester, students demonstrated substantial gains in confidence across four key competencies (identifying vulnerabilities and using tools, applying cybersecurity laws, recognizing steps in incident response, and explaining organizational response preparation) with an average improvement of +2.8 on a 1–5 scale. Separately, overall course evaluations averaged 4.4 for CS students and 4.0 for Law students, respectively, on a 1–5 scale (college average is 4.21 and 4.19, respectively). Law students reported that hands-on labs were difficult, although they were the most impactful experience. They demonstrated a notable improvement in identifying vulnerabilities and understanding response processes.

1. Introduction

Cyberattacks are costly to businesses and are becoming more prevalent each year, with 67% of businesses reporting an increase in the number of cyber attacks experienced in the last 12 months as of 2024 [1]. Due to these cyberattacks, 43% of the companies suffered a loss of customers and 47% found difficulty attracting new ones, up from 21% and 20% in 2023 [1]. These attacks place immense financial pressure on businesses. In 2024, the cost of a data breach averaged $4.88 million, a 10% increase from 2023 [2]. Moreover, in 2024, 40% of businesses identified their cyber resilience maturity as either “basic”or “ad hoc” in a self assessment—i.e., they lack formal processes and have limited cyber training and awareness [1]. Businesses cite employees using their own devices as contributing to increased risk exposure [1], demonstrating the need for a robust and cross-functional cybersecurity skillset. This is especially concerning for small-medium businesses (SMBs) because of their limited resources and their lack of awareness [3,4].

There are over 34 million SMBs in the US [5], and cyberattacks are a serious threat to them. Cybersecurity awareness and education have played a significant role in improving employee awareness. This paper proposes a comprehensive model of knowledge and skillset that will assist SMBs in defending themselves. Our research was steered by three overarching questions.

- 1.

- Where do SMBs stand with respect to cybersecurity? This question allows us to collect and synthesize existing data to identify the gap between the current SMB workforce and best practices.

- 2.

- What are the most frequent and impactful attacks faced by SMBs? This allows us to center the scope of our research on providing the most robust skillset to SMBs. This is carried out to maximize the area of coverage with as small of a workforce as possible due to the limited nature of an SMB. Our research found that the most frequent attacks are phishing/social engineering, malware/ransomware, and web-based attacks (Section 4.1). Our work on identifying the attack vectors most frequently faced by SMBs was previously published in [6].

- 3.

- How can the workforce be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to apply the best practices? This helps us incorporate the NICE Framework [7] as a bridge between the workforce and the best practices by mapping the tasks, knowledge, skills, and abilities (TKSA) to the most frequent attacks. However, the NICE Framework lists a total of 634 knowledges, 377 skills, 1006 tasks, and 177 abilities, making it costly for SMB owners to investigate and implement. Our research yielded a total of 88 technical TKSA and 54 non-technical TKSA that are required to defend against the three previously mentioned attack types (Section 4.2 and Section 4.3). This is 6.47% of the total TKSAs present in the NICE Framework and is designed to be feasible for SMBs to implement, as it extracts the TKSA most relevant to defend against the attack vectors identified. Note that these findings are preliminary. Further validation with SMB practitioners in real operational contexts will be necessary to confirm its practicality and impact.

After answering these questions, we develop a scenario-based training to enhance practical understanding and preparedness, which has been shown to be an effective learning model [8]. The curriculum provides hands-on experience in simulated environments to improve students’ ability to identify, mitigate, and respond to cyber threats as carried out in [9]. Guided by the NICE Framework, this curriculum prepares trainees, regardless of their academic background, to navigate the complex field of cybersecurity effectively.

The contributions of this paper are three-fold:

- First, the ACM cybersecurity curriculum guidelines stress that while cybersecurity is fundamentally computing-based, it inherently includes legal and policy considerations and other non-technical aspects [10]. This paper presents cybersecurity curriculum that bridges cybersecurity practice and law. Multi-disciplinary exposure helps address multifaceted cybersecurity issues and demonstrate its comprehensive view to the students. To the best of our knowledge, no textbook on security is available yet that provides an integrated view of cybersecurity. Lab manuals and the source code for the course labs are publicly available on our https://github.com/csu-techhub/scenario-security-labs (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Second, in order to provide a comprehensive, unfragmented view, cybersecurity education within context is desirable. Scenario-based learning uses interactive classroom sessions to support active learning strategies such as problem-based or case-based learning [9,11,12,13]. It normally involves students working their way through a storyline, usually based around a complex problem, which they are required to solve. Unique to the proposed curriculum is to integrate the scenarios with hands-on experiments.

- Third, a hands-on approach of security training and education are not typically available for students. In our experience, students not only like to have hands-on experience of security issues by hacking a system, but also they learn the issues and corresponding protection much better with practical experience. To this end, it is important to design specially-crafted set of experiments with virtual machine (VM)-based platforms. NICE Challenge Project [14] and Defcon’s Capture the Flag [15] are similar examples but they focus only on technical challenges [16,17,18]. We employ Ohio Cyber Range VM environment [19], where students not only perform technical analyses and mitigations but also examine the legal implications and compliance requirements of the incidents. This integrated approach ensures thorough, hands-on skills development while simultaneously grounding students in the theoretical context of cybersecurity.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides brief preliminary information supplemental to understanding this work. Section 3 discusses related works and touches briefly on the cybersecurity frameworks. Section 4 discusses the proposed methodology behind our research including the identification of the three frequent attack types and determining the best practices to counter them and map them to the TKSA present in the NICE Framework. Section 5 presents the design of the scenario-based learning model, while Section 6 analyzes students’ performance and feedback. Lastly, Section 7 gives the closing remarks.

2. Preliminaries

This section provides supplementary information important for understanding this work.

2.1. A Note on KSA and TKSA

KSA refers to knowledge, skill, and ability, and is the colloquial term used in our research field. However, the NICE Framework introduces tasks, creating the acronym TKSA. In this work, we tend to use KSA when speaking generally about the field of work due to its long-standing prevalence and well-understood meaning in the field. Conversely, when describing the NICE Framework keyword mapping, we tend to use TKSA as not to omit tasks when discussing our work.

2.2. A Note on the NICE Framework

This work is the culmination of several years of planning, research, and execution. As such, the most recent version of the NICE Framework at the onset of this work was NIST SP 800-181 [20]. Since then, NIST SP 800-181 Rev. 1 [21] has been released. This section serves as an acknowledgment of the NICE Framework revision. In the future, we plan to compare the original version with the latest and alter our approach accordingly.

2.3. Ethics Statement

The results of this work use human participation for data analysis. Their names are kept anonymous to protect their personal information.

3. Related Work

There exist several cybersecurity frameworks; one such framework is the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 27001, a well-known standard for information security management systems (ISMS) [22]. The NIST Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity consists of three main components: the “Framework Core”, “Implementation Tiers”, and “Profiles” [23]. Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR) Cyber Risk Framework [24], is a model that helps businesses analyze, measure, and understand the risks posed by cyber incidents mainly in a two-way classification: loss event frequency and loss magnitude. Nonetheless, many businesses are still lacking in their understanding of these standards, particularly SMBs [3,4,25,26]. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a medium-sized enterprise/business consists of an employee count greater than 50 but below 200–500, with the upper limit varying from country to country, while a small-sized enterprise/business consists of an employee count of less than 50 [27].

To address the gap in the workforce, we propose a TKSA model from the comprehensive NICE Framework published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [28]. The NICE framework defines a set of building blocks named tasks, knowledge, skills, and abilities. These four blocks form the foundation for building different competencies, work roles, and teams. Businesses and individuals can use the framework to assess or train themselves—it acts as a bridge between educators, employees, and businesses.

The NICE Framework and the TKSA model have been the foundation of several cybersecurity research works. Kim et al. proposed identifying the commonality and differences among three different sectors—the government, academia, and private—with respect to TKSA [29]. Their research was conducted by performing an ontological qualitative analysis using archival data, which is a limitation of their research as their findings might not reflect the current market. Nevertheless, their research provides excellent insight into how TKSA can be related to roles in different sectors. While this research was helpful, it only points out the relationship between the three different sectors and how interconnected they are. A major takeaway from their work is that it highlights the versatility and the unique application of the NICE Framework.

Bada et al. performed a case study on developing a cybersecurity awareness program for SMBs [30]. They first performed a literature review based on certain keywords and studied the best practices in securing a business’ cyberspace. Their final program was heavily based on the existing London Digital Security Center (LDSC) program which consists of five primary areas and changes to the program were performed as per their findings and recommendations. While this is a step in the right direction with spreading awareness about cybersecurity in SMBs and businesses in general, their research did not focus on specific attacks or utilize the NICE Framework, which can prove to be an excellent bridge between the workforce and educational institutes.

Tobey et al. studied how applying competency-based learning can help with creating an industry-ready cybersecurity workforce [31]. Their work discusses the difference between the outcome-based approach, which is the current approach followed by most fields of study, and the competency-based approach. The NICE Framework gives us the ability to create our own competencies based on the different TKSA [32]. A competency statement is made up of a combination of different TKSA; it is flexible and can be changed as per the needs. Tobey et al. go on to suggest that the NICE Framework is a good starting point for educational institutions to start basing their courses.

4. Proposed Work

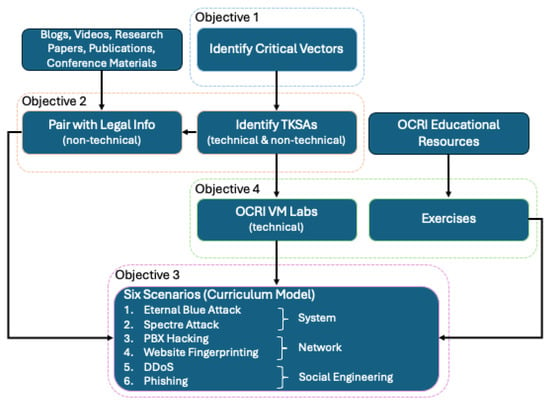

Our goal is to leverage technical and non-technical KSAs identified in the NICE Framework and map them to the most common cybersecurity attacks faced by SMBs. In doing so, we can design a hands-on and scenario-based curriculum to equip the emerging workforce with the legal and cybersecurity skills required to protect SMBs. Figure 1 gives a high-level overview of our approach.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of the Curriculum Development.

This section is broken into four subsections. Section 4.1 discusses the attack identification process including the documents and reports used, and the justification behind selecting the attacks discussed in this paper. Section 4.2 discusses the process of identifying the best practices to combat the attacks identified in Section 4.1. This section also delves into the keyword extraction program used in this paper and explains the de-duplication of similar keywords, specifically the use of Levenshtein similarity. Section 4.3 shows the mapping of keywords to the NICE Framework and Section 4.4 gives the basis of our scenario-based curriculum design.

4.1. Identifying the Most Frequent Attacks

To identify the most common attacks, we referred to reports published by Verizon, Hiscox Group, Ponemon Institute, and government agencies such as the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). They publish the latest trends of various cyberattacks, cost of mitigation, and other valuable information to help organizations prioritize their resources to defend themselves. The data they collect is usually based on surveys that multiple organizations participate in. Table 1 shows the list of the reports.

Table 1.

List of Documents Used to Identify the Attack Vectors.

According to the Verizon report, studying 18,419 cyberattacks, over 70% were web-based attacks, 30% were malware-based, and 20% were social engineering attacks [33]. Note that some of the attack vectors may overlap, resulting in the total percentage being over 100%. The Ponemon report also shows the top three attack vectors faced by SMBs are phishing/social engineering, web-based attacks, and malware [34]. The Hiscox Cyber Readiness Report paints a similar picture on the frequent attack variables, labeling phishing as the most prevalent attack vector, followed by ransomware [36].

CISA labeled ransomware as the most visible cyberattack faced by businesses in the US [25]. A report published by the ENISA states that phishing and malware attacks are the most common attacks faced by SMBs [37], and another report also published by ENISA declares malware, web-based attacks, and phishing to be the top three attacks [39].

Based on the aforementioned reports, we decided to narrow the scope of our research to phishing/social engineering, malware/ransomware, and web-based attacks. First, the three attacks cover a significant percentage of the attacks SMBs face. Second, SMBs do not have a significant workforce or budget to deal with all possible types of cyberattacks.

4.2. Identifying Best Practices and Extracting Keywords

In order to obtain the desired set of TKSA for the defense against the three attack vectors, this paper uses a well-known keyword extractor, Yet Another Keyword Extractor (YAKE!) [40] on the documents published by government agencies and standardization institutions/organizations as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of Documents Categorized by Publisher and Attack Vector.

Keyword extraction has been widely used to derive knowledge maps [50,51,52]. YAKE! allows us to achieve better results compared to other state-of-the-art keyword extraction methods such as Rake and TextRank [40]. The n-gram parameter, which stands for the size of a sequence of terms in a keyword, was suggested to be set at 3 for the best results [40].

To ensure the credibility and quality of the best practices, we restricted our pool of documents to limited but highly credible and well-established ones from organizations such as NIST, CISA, Federal Trade Commission (FTC), ENISA, National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), and the Australian Cybersecurity Centre (ACSC) as shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows a snippet of keywords extracted from a document [41] along with their score (S). S is based on keyword features (term casing, term position, term frequency normalization, term relatedness to context, term different sentence) and is computed by the YAKE! algorithm. The lower the value of S, the more significant the keyword [53].

Table 3.

Snippet of Keywords Extracted from [41].

To eliminate similar keywords, we employed a de-duplication process based on similarity algorithms such as Levenshtein similarity [54], Jaro-Winkler [55], and Hamming Distance [56,57]. We used Levenshtein similarity because it works on the principle of the minimum number of single-character edits required to change one word into the other [57]. For example, take a group of similar keywords like “Secure Gateway Capabilities”, “Gateway Capabilities”, and “Secure Gateway”, all of which are similar and can be considered as just one keyword, “Secure Gateway Capabilities”. Table 3 shows a snippet of keywords after the de-duplication process is applied, the “After De-Duplication” column shows if the keyword was removed after the de-duplication process.

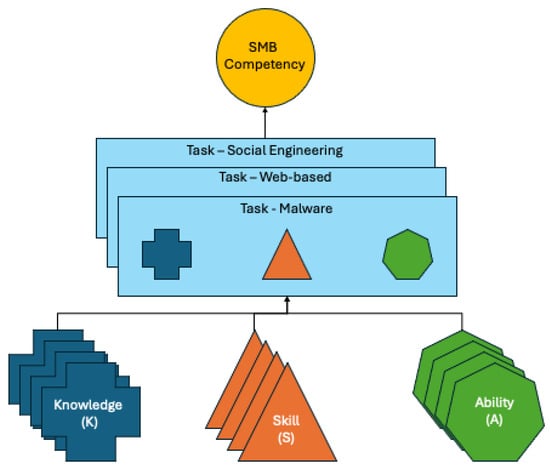

4.3. Mapping Keywords to the NICE Framework

As shown in Figure 2 our goal is to map TKSAs to competencies related to the attack vectors relevant to SMBs identified above. For the mapping of keywords to NICE TKSAs, we used NICCS (National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies) NICE Framework Tools [58], which is the main portal on the CISA website. It offers a variety of ways to explore the framework, where key tools include Work Role Search, Knowledge Search, Skill Search and Task Search. For convenience, we divided the result of the mapping exercise into two models, technical and non-technical. The technical model consists of all the TKSA that involve a certain level of proficiency in the technical aspect of cybersecurity, whereas the non-technical model consists of TKSA that are related to general cyber awareness, legal, and managerial proficiencies. Most of the non-technical TKSA can be applied to all employees of an SMB. Section 4.3.1 and Section 4.3.2 explain the technical and non-technical model respectively.

Figure 2.

Relationship Between Competency and TKSA.

4.3.1. Technical Model

We mapped 49 technical knowledges covering 7.57% of all the knowledges in the NICE Framework, 23 technical skills covering 6.10% of all the skills in the NICE Framework, 6 technical abilities covering 3.38% of all the abilities in the NICE Framework, and 10 technical tasks covering 1.02% of all the tasks in the NICE Framework, totaling 88 technical TKSA. These TKSA all address a different aspect of dealing with the three attack vectors. Table 4 depicts the technical knowledges mapped to the three different attack vectors. K0002 for example, “knowledge of risk management processes (e.g., methods for assessing and mitigating risk)”; is a broad statement that can be used in all three attack cases. Conversely, K0105—“lknowledge of web services (e.g., service-oriented architecture, Simple Object Access Protocol, and web service description language)”—and K0188—“knowledge of malware analysis tools (e.g., Oily Debug, Ida Pro)”—are specific to an attack.

Table 4.

Snippet of technical knowledge mapped to the three attack vectors (7.8% of all the knowledge in the NICE Framework). The asterisks mark Knowledge Units covered in course scenarios. For example, K0038 is addressed in the Malware/Ransomware modules.

A total of 56.26% of the technical knowledges we mapped apply to just one specific attack vector; i.e., they cannot be applied to a different attack than the ones they are mapped to. 16.66% of the technical knowledges are mapped to two attacks; i.e., it can vary based on the description of the knowledge and they can be used in two specific attacks out of the three. For example, K0202 applies to phishing/social engineering attacks and malware/ransomware attacks but does not apply to web-based attacks. The remaining 27.08% of the knowledges apply to all three attack vectors.

The skills and abilities are the least versatile among the technical TKSAs, with 56.53% of the technical skills and 83.33% of the technical abilities applying to only one specific attack vector. The knowledges are to be the most versatile among the technical TKSA with 40% of them applying to all three attack vectors, and 50% applying to at least two specific attack vectors.

4.3.2. Non-Technical Model

The non-technical model consists of 28 non-technical knowledges covering 4.41% of all the knowledges in the NICE Framework, 8 non-technical skills covering 2.12% of all the skills in the NICE Framework, 7 non-technical abilities covering 3.95% of all the abilities in the NICE Framework, and 11 non-technical tasks covering 1.12% of all the tasks in the NICE Framework, adding up to a total of 54 non-technical TKSA. They paint a different picture when compared to the technical model due to most of the general non-technical TKSA being applicable to all the 3 attack vectors. Table 5 depicts how non-technical knowledges are mapped to the three attack vectors.

Table 5.

Snippet of non-technical knowledge mapped to the three attack vectors (4.4% of all the knowledge in the NICE Framework). The asterisks mark Knowledge Units covered in course scenarios. For example, K0126 is addressed in the Malware/Ransomware modules.

In total, 93% of the non-technical knowledges apply to all 3 attack vectors, with only 7% of the non-technical knowledges applying to one specific attack. 85% of the non-technical abilities and 87.5% of the non-technical skills apply to all 3 attack vectors, while 91% of the non-technical tasks apply to all 3 attack vectors.

When both models are compared, we noticed the non-technical model to be more versatile than the technical model. This is in line with our expectations. The technical model proves to be more technically sound and specific to particular attack vectors while the non-technical model applies to cybersecurity in general and is not heavily based on attack vectors.

4.4. Integration of KSAs, Virtual Machine Labs, and NICE Framework

A robust cybersecurity and legal education strategy integrates legal frameworks/regulations and KSAs with hands-on practice in virtual machine labs, guided by the NICE framework. This ensures that learners not only grasp theoretical concepts but also acquire practical skills to tackle real-world cybersecurity and legal challenges. The NICE Framework’s structured roles and competencies guide curriculum development, aligning programs with industry standards. Virtual machine labs provide a practical setting for learners to apply theoretical knowledge, simulate cyberattacks, and build skills in areas such as network security and incident response. Each lab aligns with specific KSAs and is augmented by legal case studies and frameworks, reinforcing learning and building confidence in managing cybersecurity issues. This integrated approach enhances employability, adapts to emerging threats, and ensures that education programs remain relevant and effective.

This research introduces a tailored legal and cybersecurity curriculum designed specifically to meet the needs of SMBs, with a focus on the most relevant threats such as phishing/social engineering, malware/ransomware, and web-based attacks (Objective 1). Through a scenario-based learning model (Objective 3), students participate in realistic threat simulations, enhancing their problem-solving and practical skills in identifying and mitigating these targeted risks [59]. This curriculum, therefore, prepares both law and computer science (CS) students for roles involving cybersecurity risk assessment, regulatory compliance, and legal forensics. Key scenarios include managing malware (e.g., EternalBlue and Spectre/Meltdown), responding to web-based attacks (e.g., PBX Hacking and Website Fingerprinting), and understanding social engineering tactics (e.g., DDoS and Hacking Group Thallium), providing hands-on experience that prepares students for real-world challenges [7].

The curriculum also emphasizes the development of practical skills using virtual machine labs through the Ohio Cyber Range Institute (OCRI) [19] resources (Objective 4), offering immersive training in cybersecurity roles. Aligned with the NICE Framework, it fosters the development of essential KSAs [60], integrating both technical and legal knowledge (Objective 2) to equip students with a comprehensive understanding of cybersecurity [60]. This holistic approach ensures graduates are well-prepared to defend SMBs against evolving cyber threats and comply to legal regulations, bridging the gap between theory and practice in cybersecurity education.

5. Scenario-Based Curriculum

This paper presents cybersecurity curriculum that bridges cybersecurity practice and law. The curriculum follows a distinctive learning approach using a set of recent real-life cybersecurity scenarios so that students are exposed to the fastest-evolving field in a most unique and efficient manner. Students engage in scenarios that simulate actual cyber threats, e.g., phishing attacks, malware infections, or data breaches, to understand and apply cybersecurity principles in practice [9] in Ohio Cyber Range VM environment [19]. In this curriculum, students analyze scenarios, identify relevant cybersecurity concepts and regulations, and develop appropriate responses, some of which may be legally required. This method enhances theoretical understanding by demonstrating practical applications and integrating legal considerations—such as data privacy laws and regulatory compliance—into the scenarios [8].

The curriculum consists of a mix of lectures, direct/indirect lab experiments, and group discussions to ensure course compliance. Concepts can be introduced in lectures, but the learning uptake is best when the students can experience the concepts through practice and interdisciplinary group discussions. The group discussion session is an important element of this course. Cross-disciplinary team learning is to mimic the tabletop conversation to solve a cyber-attack problem in a practical environment. Four learning goals are: (i) self-identify skills, knowledge, and potential project contributions (identification), (ii) recognize the potential contributions of others to the project (recognition), (iii) interact with team members during design discussion to draw out and clarify disciplinary perspectives (interaction), and (iv) synthesize awareness and appreciation of other disciplines and reflect this understanding in design products (integration) [61]. In each of the cybersecurity scenarios, students become aware of the difficulties and yet the criticalness of the four aspects of cross-disciplinary team learning, particularly in order to solve the complex cybersecurity phenomenon.

The curriculum features six key scenarios targeting malware/ransomware, web-based attacks, and phishing/social engineering, each designed to provide practical experience:

- Scenario 1:

- EternalBlue—focuses on a malware attack exploiting the EternalBlue vulnerability, emphasizing patch management.

- Scenario 2:

- Spectre/Meltdown—addresses hardware-level vulnerabilities and the need for robust hardware security.

- Scenario 3:

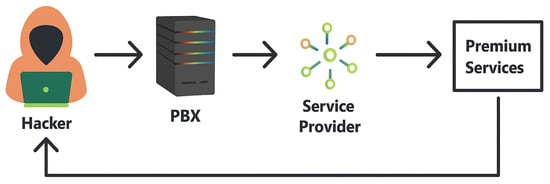

- PBX Hacking—deals with web-based attacks on private branch exchange (PBX) systems, highlighting network security challenges.

- Scenario 4:

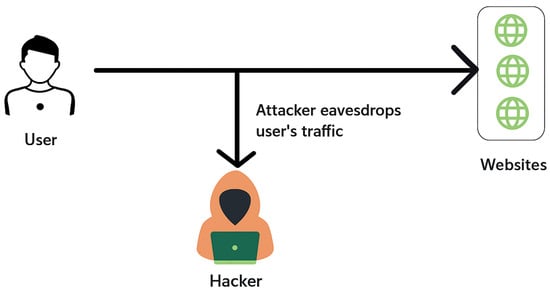

- Website Fingerprinting—explores attacks through website fingerprinting, stressing web traffic protection.

- Scenario 5:

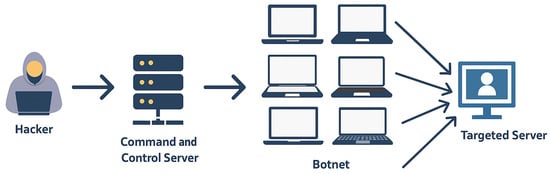

- DDoS Attack—involves a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack, focusing on network resilience.

- Scenario 6:

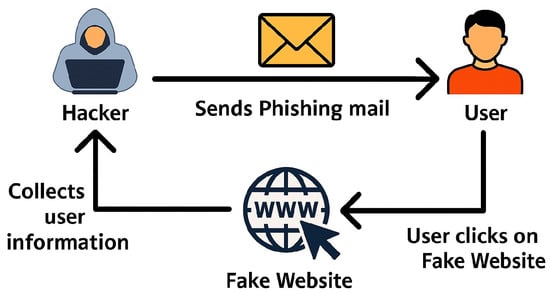

- Hacking Group Thallium—examines a phishing attack by the Thallium group, emphasizing defense against social engineering.

Each scenario is paired with hands-on labs using OCRI-supported virtual machines and legal materials, ensuring a thorough and practical approach to skill development. The scenarios are explained in further detail below in Section 5.2 and the course syllabus is given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Course Syllabus.

5.1. Scenarios and TKSAs

We have identified 49 technical knowledge areas and 28 non-technical knowledge areas which are essential for protecting SMBs. Table 7 and Table 8 below map these TKSAs to the six key scenarios, organized by category. This categorization simplifies the identification of required TKSAs and underscores the specific areas of expertise needed to address each type of threat.

Table 7.

List of Non-Technical TKSAs Mapped to the Three Attack Vectors.

Table 8.

List of Technical TKSAs Mapped to the Three Attack Vectors.

5.1.1. Leveraging Virtual Machine Labs

Virtual machine labs play a crucial role in developing cybersecurity skills by providing an interactive, hands-on learning environment. These labs simulate real-world cyber threats, allowing learners to enhance their skills in a controlled setting.

Our VM lab uses the OCRI platform, which hosts virtual machines such as Kali Linux, Windows 7, and Windows 11, offering a comprehensive environment for cybersecurity training. OCRI supports advanced education through scalable and accessible labs that replicate real-world attack scenarios. Note that some platforms, such as Windows 7, are no longer used in production environments. However, from an educational standpoint, Windows 7 remains valuable because it contains well-documented vulnerabilities that allow students to safely explore real attack mechanisms and mitigation strategies. The Ohio Cyber Range virtual machine platform, which we used to conduct the attacks, includes Windows 7 and Kali Linux images specifically to support controlled cybersecurity training and research environments.

The flexibility of OCRI labs allows learners to access them remotely, catering to diverse schedules and skill levels. This approach ensures practical learning experiences, preparing students to effectively handle cybersecurity challenges.

5.1.2. OCRI Exercises

The OCRI educational resources include 14 modules covering topics like cryptography, digital forensics, network security, and encryption, with exercises designed to enhance practical cybersecurity skills. Our curriculum incorporates selected exercises from these modules to provide hands-on experience with specific threat vectors. Modules such as “Introduction to Digital Forensics” and “Defense in Depth Network Security” are used to teach essential skills in areas such as malware analysis, network and firewall configuration, password security, and encryption. These exercises offer students practical, scenario-based learning opportunities, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world cybersecurity challenges.

5.1.3. Legal Considerations

Understanding the legal landscape is critical in cybersecurity as it helps organizations comply with regulations, handle cyber incidents, and manage data breaches. Each of the scenarios is paired with several key legal readings and resources to augment the lesson and demonstrate the intersection of legal requirements and cybersecurity. These materials cover important topics such as ransomware investigations, data breach notification laws and other regulatory compliance, and international legal issues. By integrating legal insights throughout the curriculum, learners gain a comprehensive understanding of how to navigate the legal complexities that accompany cybersecurity challenges.

5.2. Overview of Scenarios

Below, we give a brief overview of each of the scenarios used in the curriculum, including the hands-on lab and legal resources. Table 9 gives an overview of each scenario including a description and the integrated non-technical skills.

Table 9.

Cybersecurity Scenarios with Attacks and Non-Technical Topics.

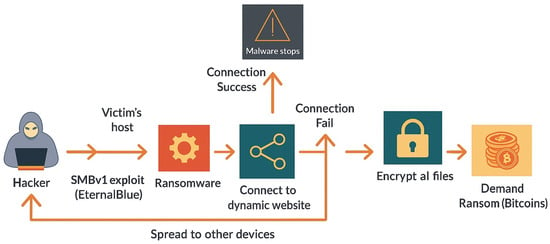

5.2.1. Scenario 1: EternalBlue

In this lab, participants engage in the simulation of the EternalBlue attack [85], a notorious exploit that capitalizes on the vulnerability within the SMBv1 protocol to propagate malware across networks. Figure 3 provides a graphical overview of the scenario. Utilizing Kali Linux as the attacker’s platform and Windows 7 as the target system, the exercise begins with the acquisition and unpacking of ransomware from a specified URL, laying the groundwork for subsequent malicious activities. Leveraging the inherent weaknesses in Microsoft Window’s handling of specially crafted packets, participants exploit the EternalBlue vulnerability to establish a meterpreter session, gaining unauthorized access to the victim’s machine. Subsequently, the exploit is employed to transmit the ransomware to the victim’s system, initiating the encryption process for all accessible files.

Figure 3.

EternalBlue Attack.

This scenario begins students’ introduction to incident response. With the readings assigned for this scenario, students learn critical components of an incident response, including background, planning, and execution [65]. The readings reinforce that a security incident is often considered inevitable and that planning for such an incident is critical and must be cross-functional [65]. Building off a cross-functional incident response, legal obligations, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) [86] and data breach notification laws, are incorporated into this scenario.

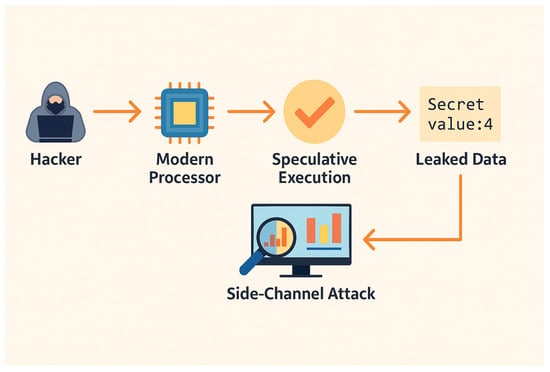

5.2.2. Scenario 2: Spectre/Meltdown

This scenario involves students comprehending a spectre attack [87] on a Kali Linux machine, shown in Figure 4. Additionally, students scrutinize legal issues and risks arising from hardware vulnerabilities in the context of cybersecurity practice, including laws that govern the responsibility for identifying vulnerabilities and potential liability for organizations affected by related cyberattacks. They will also learn to advise clients on vulnerability disclosure [73,88].

Figure 4.

Spectre Attack.

5.2.3. Scenario 3: PBX Hacking

As shown in Figure 5, this lab experiment explores security vulnerabilities in PBX administrative systems by focusing on the risk posed by weak passwords [89,90]. While threats like firewall bypasses and cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities in Free PBX exist, the primary goal is to emphasize the dangers of inadequate password security. The setup involves three machines: a Linux machine as the PBX hub, a Windows machine for PBX configuration, and a Kali Linux machine for probing the system. Using Kali Linux, the attacker intercepts HTTP requests between the PBX and Windows and employs Hydra, a password-cracking tool, to access the admin panel, highlighting the need for strong password protections.

Figure 5.

PBX Attack. Cyber Criminals exploit vulnerabilities to reroute calls to pay-per-minute lines, incurring substantial charges for the user.

The readings assigned for this scenario introduce students to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) [91]. Through case studies where individuals were charged with violating the CFAA [63], students gain a fundamental understanding of what constitutes a cyber crime and the legal implications that follow. Other concepts discussed in this scenario are wire fraud [92] and identity fraud [93].

5.2.4. Scenario 4: Website Fingerprinting

In this lab, students simulate a website fingerprinting attack using k Nearest Neighbors (kNN) on a Kali Linux machine. The goal is to analyze traffic patterns such as packet lengths, frequency, and timing to identify visits to blacklisted websites [94]. Students conduct 15 browsing sessions for each site, capturing traffic data from seven websites using the Lynx browser. The data is generated by a tcpdump [95] for each website visit and used to train a kNN classifier to determine whether a user is accessing any of the blacklisted websites by analyzing distinct patterns of web traffic. Figure 6 shows the setup for this scenario. A case study from the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCE) reinforces this lesson by giving a real-world example of censorship and discussing the right to secure Internet access and privacy [76].

Figure 6.

Website Fingerprinting Attack. Encrypted web traffic patterns are analyzed to infer user-visited websites and compromise privacy.

5.2.5. Scenario 5: Distributed Denial of Service Attack

In this scenario, a DDoS attack [96], shown in Figure 7, is simulated using Kali Linux and Windows operating systems. Our attackers will be Kali Linux and Windows 7 (functioning as a bot for Kali Linux), targeting a Windows XP machine. The attacker compromises vulnerable hosts, turning them into “bots” via techniques such as simple password guessing or by exploiting vulnerabilities such as EternalBlue. Once compromised, those bots are directed to generate high-volume traffic aimed at the victim, overwhelming its network and services. We exploit the server message block (SMBv1) vulnerability, injecting data packets into the network. The main goal is to simulate and observe the network traffic on Windows XP, achieved through a blend of scripting, Metasploit, and external tools.

Figure 7.

DDoS Attack. A botnet, controlled by a hacker, floods a target server with excessive traffic to cause service disruption.

5.2.6. Scenario 6: Hacking Group Thallium

This scenario, outlined in Figure 8, simulates a phishing attack using the Zphisher [97] tool on a Kali Linux machine, where a deceptive webpage mimicking popular websites—such as Facebook or Instagram—is created. Victims on a Windows machine interact with the phishing link, and any entered credentials are captured and displayed on the attacker’s terminal. The lab also demonstrates how to make the phishing page accessible online using ngrok [98], allowing for real-time capture of the victim’s credentials. As part of the legal reading paired with this scenario, students read the original complaint filed by Microsoft against Thallium [82], giving them the cybersecurity and legal background of a high-profile real-world example.

Figure 8.

Phishing Attack. A user is tricked by a phishing email into providing sensitive information on a fake website.

Note that we use Ohio Cyber Range VM-based cybersecurity sandbox environment to ensure safety and compliance. Although ngrok is demonstrated, it is configured to operate only within the internal, isolated virtual network, not the public internet. The tunnel endpoint is mapped to a private, non-routable address inside the sandbox, and outbound traffic is restricted to prevent any external exposure. As a result, the phishing page and captured credentials never leave the controlled environment, and only dummy test accounts are used. No live systems or real users are involved at any stage. No live systems or real users were targeted.

6. Results and Analysis

A combined law and CS course composed of the scenario-based model outlined above was offered at the university in spring 2024 and spring 2025. We use the students’ performance and feedback—which consists of indirect assessment measures (interviews, surveys, and feedback) and a direct measure (lab and quiz performance)—from the course for analysis. Interviews provided qualitative insights into student experiences, while surveys covered teaching effectiveness, course content relevance, and student proficiency in cybersecurity. Student feedback mechanisms and course evaluations offered further insights to inform curriculum improvements.

6.1. Focus Group Interview

On 27 March 2024, focus group interviews were conducted with students from the combined law and CS cybersecurity course. Two groups, each with two law and two CS students, participated in 20-min sessions to provide feedback on the effectiveness of the course. We present the key takeaways below:

- 1.

- Targeted Threats: Students valued the hands-on scenarios for enhancing their cybersecurity understanding, but CS students found them easy, while law students struggled and requested clearer instructions. Balancing difficulty and guidance would improve the experience.

- 2.

- Holistic Knowledge: The non-technical material offered valuable multidisciplinary perspectives, though CS students desired more technical content, and law students found some readings repetitive. Refining content for both backgrounds could enhance learning.

- 3.

- Scenario-Based Model: While the scenario approach effectively bridged theory and practice, differing difficulty levels for CS and law students indicated a need for adjustments to equally challenge all participants.

- 4.

- Practical Experience: Hands-on labs were well-received by CS students, and although law students faced challenges, they gained valuable exposure. Technical support improvements were suggested to address lab difficulties.

In addition, the students appreciated the interdisciplinary approach, which increased their confidence in cybersecurity and law, and suggested more collaboration opportunities, such as class discussions. While the course was generally successful, refining content and enhancing collaboration would further improve its effectiveness.

6.2. Student Survey

As part of the course, we invited students to complete a survey at the beginning and end of the semester. The survey aimed to gauge students’ initial knowledge, expectations, and confidence levels (before), and to measure the impact of the course on their understanding and skills in cybersecurity (after). These responses provide insight into the effectiveness of the course in enhancing students’ capabilities and confidence in tackling cybersecurity challenges. Students’ confidence level changes are shown followed by a summary of their responses as they relate to the four objectives stated above.

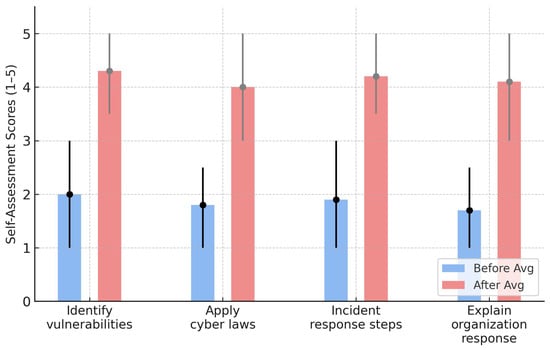

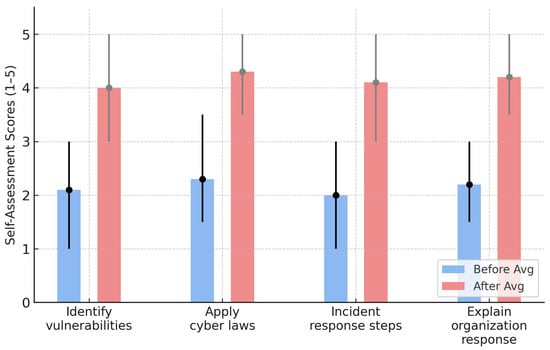

6.2.1. Self Knowledge Assessment

20 Computer Science and 5 Law students (Spring 2025) completed reflective self-assessments at the start and end of the semester for the Hack Lab cybersecurity course. (23 CS and 8 Law students took the course and thus, the response rate is 81%.) Students demonstrated substantial gains in confidence across four key competencies (identifying vulnerabilities and using tools, applying cybersecurity laws, recognizing steps in incident response, and explaining organizational response preparation) with an average improvement of +2.8 on a 1–5 scale as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

CS Students’ Self Knowledge Assessment Before and After Taking the Course. (The numerical before/after values shown in this figure summarize themes extracted from narrative reflections and do not represent quantitative survey responses).

Figure 10.

Law Students’ Self Knowledge Assessment Before and After Taking the Course. (The numerical before/after values shown in this figure summarize themes extracted from narrative reflections and do not represent quantitative survey responses).

It is important to note that the self-assessment activity used in this study elicited open-ended narrative responses rather than numerical Likert-scale ratings. As a result, the before-and-after summaries presented in Figure 9 and Figure 10 reflect qualitative patterns interpreted from student reflections and should not be interpreted as inferential statistical findings. This qualitative approach provides useful insight into students’ self-perceived growth, but it also limits the extent to which statistical generalizations can be made.

The largest gains among CS students were in incident response process understanding and organizational preparation, areas that were least familiar before the course. Their definitions of “hacking” evolved from a narrow focus on “unauthorized access” to a more nuanced understanding involving ethical hacking, system protection, and legal awareness. For Law students, the strongest Improvement were in understanding of technical and organizational response improved the most (+3.0). Students shifted from little to no technical familiarity to being able to describe and interpret exploit patterns, e.g., EternalBlue or Spectre.

Several noted the class gave them a “hands-on appreciation” for how quickly exploits can occur and the importance of coordinated incident response. Overall, both groups achieved meaningful learning gains, but with complementary strengths. This outcome underscores the success of the Hack Lab model in fostering a shared cybersecurity competency that bridges the technical–legal divide.

6.2.2. Threats Targeting SMBs

Prior to taking the course, students had a vague awareness of different cyber threats, with CS students having more exposure from other classes; however, both disciplines of students lacked fundamentals. By the end of the semester, students could provide concrete examples of the threat categories taught in the course. Furthermore, they reported improvement in their ability to identify vulnerabilities and apply tools to exploit them in simulated labs.

6.2.3. Technical and Legal Understanding

Before taking the course, CS students reported that they had technical confidence but lacked understanding of legal frameworks. By contrast, law students had an understanding of legal basics but were unsure how they translated directly to cybersecurity threats. At the end of the semester, CS students indicated that they could map technical requirements to legal compliance standards. Additionally, law students demonstrated that they now understood how a cybersecurity incident can trigger certain laws into effect and the importance of technical features such as logging for incident response.

6.2.4. Scenario-Based Learning Model

At the start of the course, students admitted that they had little to no experience with a full incident response. Furthermore, CS and law students’ experiences were fragmented on different portions of a full scenario, with CS students having some experience with technical labs and law students conducting case studies. At the end of the semester, students indicated that they had gained a step-by-step fluency in a incident response for different threats. Moreover, students reported that they had a high degree of confidence in applying legal frameworks to the different scenarios.

6.2.5. Practical Experience and Skills

Students initially reported that they had no hands-on experience with incident response and only vague knowledge of the technical tools used in such cases. At the end of the course, students felt that the hands-on labs provided practical insight into cybersecurity tools and concepts. CS students enjoyed the complexity, while law students, although they found the labs challenging, benefited from the practical exposure. Finally, students reported that they felt confident in executing a clear step-by-step workflow for incident response.

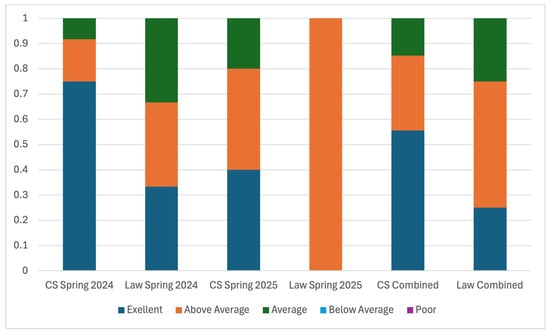

6.3. Students’ Course Evaluation

As a part of the institutional mechanism to improve our teaching, students are given the opportunity to complete anonymous course evaluations. Course evaluation feedback comprises both quantitative ratings and qualitative comments from students; however, in this analysis, we focus on quantitative ratings to provide a clear numerical understanding of student satisfaction and perceived course effectiveness. Students’ course ratings are shown in Figure 11. We summarize the findings below.

Figure 11.

Students’ Course Evaluation. Note that responses of “Below Average” and “Poor” were not received. (Response/Sample size: CS Spring 24-12/15, Law Spring 24-3/6, CS Spring 25-15/22, and Law Spring 25-1/7; instruments: CSU’s official student course evaluation).

6.3.1. Course Evaluation from CS Students

The quantitative course ratings from CS students indicate an overall high satisfaction with the course, with the aggregate ratings from both semesters being 4.41 out of 5. A detailed breakdown yields 55.5% “Excellent” (5), 29.6% “Above Average” (4), and 14.8% “Average” (3) as shown in Figure 11. This is above both the department (4.25 in spring 2024 and 4.1 in spring 2025) and college (4.23 in spring 2024 and 4.18 in spring 2025) average course ratings. However, it must be noted that from spring 2024 to spring 2025, CS students’ rating of the course decreased. This may be explained by changes in course delivery methods to better accommodate law students, indicating that work still needs to be carried out to find a balance between the two disciplines. Nevertheless, when CS students’ course ratings are split by semester, the average is 4.67 for spring 2024 and 4.20 for spring 2025, which is still higher than the department and college average course rating for their respective semesters.

6.3.2. Course Evaluation from Law Students

In contrast to the CS students, law students’ satisfaction with the course remained stagnant from spring 2024 to spring 2025, reinforcing the point from above that a balance must be struck to engage both types of students. The aggregate course rating of law students is 4.0 out of 5 where 25.0% rated the course “Excellent” (5), 50.0% “Above Average” (4), and 25.0% “Average” (3). The average for each semester is also 4.0. This is below the college average in both semesters (4.22 in spring 2024 and 4.16 in spring 2025), indicating more room for improvement (note that there is only one department in the College of Law; so, the department average is the same as the college). We recognize the uneven difficulty across groups; future iterations of the course will include additional support materials, such as pre-labs and tutorials, to improve balance and accessibility for students with diverse backgrounds.

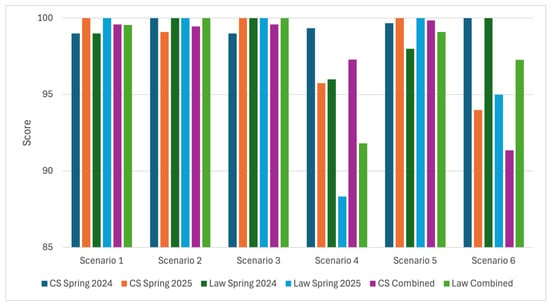

6.4. Students’ Performance

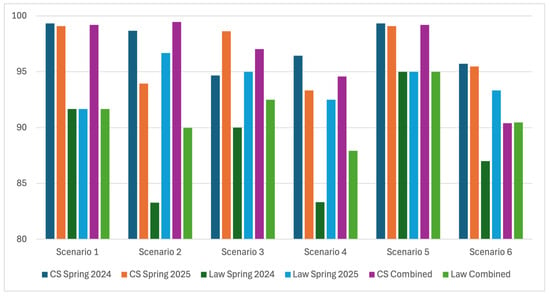

One direct measure of student learning outcomes is their performance in homework assignments (labs) and quizzes. There were six labs and six quizzes corresponding to the six cybersecurity scenarios. A detailed analysis of student performance is illustrated in the following graphs. Figure 12 compares the average scores between law and CS students in each lab by semester. Observe that in general, both CS and law students perform well on the lab assignments with the lowest average score being law students in spring 2025 on Scenario 4 (88.3%). This statistic highlights the ability of the interactive scenario-based learning environment to leverage the different skillsets of law and CS students to reach a common level of understanding. That said, students had more difficulty with Scenario 4 (website fingerprinting) and Scenario 6 (phishing). In particular, for both scenarios and for both CS and law students, the performance in spring 2024 is higher than in spring 2025. It must be noted, however, that even where students experienced difficulty, the average scores for those scenarios are above 85%.

Figure 12.

Average Scores of CS and Law Students on Scenario-Based Labs by Semester. Both CS and law students struggle with Scenarios 4 and 6. Note that the range on the y-axis has been condensed to 50–100 for enhanced visual clarity. (Sample size: CS Spring 24-15, Law Spring 24-6, CS Spring 25-22, and Law Spring 25-7; Response rate: 100%; instruments: Part of the course requirements).

Students’ quiz scores are shown in Figure 13. While students still perform well on quizzes, with average scores of all students being above 80%, the results are more variable than the labs, and law students consistently score lower than CS students. Despite this, it is important to note that law students showed a marked improvement in average quiz scores from spring 2024 to spring 2025, demonstrating an improved comprehension in the second offering of the course. This could be explained by a multitude of factors, e.g., adaptation of teaching style. We can also see that both sets of students find more difficulty with Scenarios 4 and 6, as was the case with lab scores. Such results suggest the need to revisit the content and delivery of these two scenarios, as both types of students scored lower.

Figure 13.

Average Quiz Score of CS and Law Students by Semester. Scores are variable, with CS students scoring more consistently between semesters. Both CS and law students have more difficulty with Scenarios 3 and 4. (Sample size: CS Spring 24-15, Law Spring 24-6, CS Spring 25-22, and Law Spring 25-7; Response rate: 100%; instruments: Part of the course requirements).

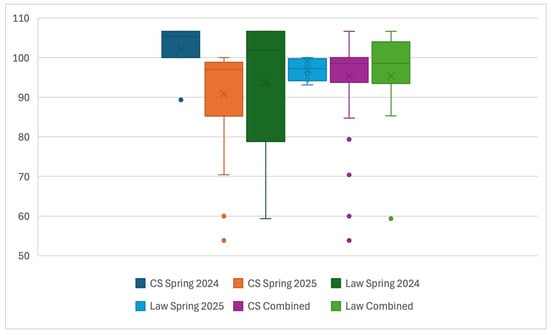

To round out our grade analysis, we investigate the weighted final scores of students, shown below in Figure 14. Note that scores range above 100% due to extra credit. The results by semester are variable, with CS students scoring very consistently in spring 2024 and with more variability in spring 2025. Conversely, law students’ scores are more variable in spring 2024 but more consistent in spring 2025. In both cases, the variability is explained by a few students scoring lower, skewing the mean from the median. In fact, across all semesters, the median final score is above 98%. The overall spread of both CS and law students is similar when examining both semesters; however, the interquartile range (IQR) of CS students is far more condensed, indicating that law students have a higher degree of variability in scores. Despite differences in the IQR, the average and median final scores of law and CS students are close—the median scores are 98.5% for CS students and 98.6% for law students, while the average scores are 95.4% for CS students and 95.3% for law students. Such results further exemplify the successful implementation of an interdisciplinary and hands-on scenario-based learning environment in conveying legal and cybersecurity concepts to students from different backgrounds—more explicitly, CS students learned and applied legal concepts as did law students with cybersecurity concepts. Furthermore, that law students received final grades comparable to those of CS students, which shows that while they may have experienced some difficulty with technical aspects of the course—i.e., labs and quizzes—it did not hinder their overall performance.

Figure 14.

Distribution of Final Grades for CS and Law Students with Outliers Shown. The average and median scores for both student types are comparable. Note that a score above 100% is possible due to extra credit. (Sample size: CS Spring 24-15, Law Spring 24-6, CS Spring 25-22, and Law Spring 25-7).

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, our research enhances cybersecurity education by developing a curriculum tailored for small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) that integrates practical experience and legal knowledge. Feedback from students highlighted a positive reception, emphasizing the hands-on approach and real-world relevance of lab exercises, despite some challenges faced by law students. This curriculum empowers future cybersecurity professionals to safeguard SMBs and improve digital security, while the insights gained will guide future educational enhancements, fostering a more resilient cybersecurity workforce.

Our findings led to a model that serves as a sound reference for SMBs to equip themselves with and defend against the attacks discussed in this paper. With the KSAs acting as a bridge between the implementation of the best practices, SMBs can focus on the model and create evaluation and training activities for their existing workforce. SMBs can further extend the work presented in this paper by building their own competencies, and work-roles based on the TKSAs presented here and NIST guidelines. This opens up a path for SMBs to collaborate with educational institutions to build new course work based on real world scenarios. Educational institutions can design new competencies based on the TKSA presented in this paper and build a fully modular multidisciplinary course with a scenario-based learning module to help equip the upcoming cyber-workforce [9].

With cybersecurity being an ever-growing and ever-changing field, KSAs can be derived for more than just the three attacks discussed in this research. In the future, our goal is to determine a list of TKSAs for cybersecurity best practices related to the Internet of Things (IoT) domain. Businesses and individuals are adopting smart technologies and many are not aware of the threats they expose themselves to. With very little research available in the field, we aim to touch upon these topics and expand our current work to include them in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y., B.E.R., D.K.J. and S.K.; methodology, C.Y., B.E.R., A.V.R. and K.M.M.; software, C.M., A.V.R., K.M.M. and S.K.; validation, C.Y. and S.K.; formal analysis, C.M., A.V.R., K.M.M. and D.K.J.; investigation, C.M., A.V.R. and K.M.M.; resources, C.Y., B.E.R. and S.K.; data curation, C.M., K.M.M. and D.K.J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M., A.V.R., K.M.M. and C.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.M., C.Y. and S.K.; visualization, C.M. and K.M.M.; supervision, C.Y., B.E.R., D.K.J. and S.K.; project administration, C.Y., B.E.R., D.K.J. and S.K.; funding acquisition, C.Y., B.E.R., D.K.J. and S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation grant number 2028397.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Revised Common Rule (enacted 21 January 2019), which aligns with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cleveland State University (IRB-FY2021-200 and date of approval: 2 August 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data contain sensitive information from anonymous student participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Chansu Yu.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Ohio Cyber Range Institute (OCRI) for their resources. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT, GPT 4.0 for the purposes of summarizing the students’ self knowledge assessment at the beginning and end of the course as they relate to the four research objectives of this work. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hiscox Group. Cyber Readiness Report 2024; Technical Report; Hiscox Group: Hamilton, Bermuda, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ponemon Institute; IBM Security. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2024; Technical Report; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dojkovski, S.; Lichtenstein, S.; Warren, M.J. Fostering Information Security Culture in Small and Medium Size Enterprises: An Interpretive Study in Australia. In Proceedings of the 2007 European Conference on Information System (ECIS), St. Gallen, Switzerland, 7–9 June 2007; pp. 1560–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen, C. Cybersecuring Small Businesses. Computer 2016, 49, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy. 2024 Small Business Profile: United States; Technical Report; U.S. Small Business Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Raghavan, A.V.; Yu, C. Task, Knowledge, Skill, and Ability: Equipping the Small-Medium Businesses Cybersecurity Workforce. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, American Society for Engineering Education, Portland, OR, USA, 3 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse, W.D.; Keith, S.; Scribner, B.; Witte, G.A. National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework; Special Publication NIST SP 800-181; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Brilingaitė, A.; Bukauskas, L.; Juozapavičius, A. A framework for competence development and assessment in hybrid cybersecurity exercises. Comput. Secur. 2020, 88, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Francia, G. Assessing Competencies Using Scenario-Based Learning in Cybersecurity. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2021, 1, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Task Force on Cybersecurity Education. Cybersecurity 2017 Version 1.0: Curriculum Guidelines for Post-Secondary Degree Programs in Cybersecurity; Technical Report; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, USA; IEEE Computer Society (IEEE-CS): Piscataway, NJ, USA; Association for Information Systems SIGSEC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shivapurkar, M.; Bhatia, S.; Ahmed, I. Problem-Based Learning for Cybersecurity Education. J. Colloq. Inf. Syst. Secur. Educ. 2020, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R. Accelerating Expertise with Scenario-Based Learning; Learning Blueprint/American Society for Training and Development: Merrifield, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Savery, J.R. Overview of Problem-Based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions. Interdiscip. J.-Probl.-Based Learn. 2006, 9, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Challenge Project. 2014. Available online: https://www.nice-challenge.com/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Cowan, C.; Arnold, S.; Beattie, S.; Wright, C.; Viega, J. Defcon Capture the Flag: Defending Vulnerable Code from Intense Attack. In Proceedings of the DARPA Information Survivability Conference and Exposition (DISCEX III), Washington, DC, USA, 22–24 April 2003; pp. 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.S.; Cohen, J.P.; Lo, H.Z.; Elia, F. Challenge-Based Learning in Cybersecurity Education. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Security & Management (SAM 2011), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 18–21 July 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, P.J.; Wudi, J.M. Designing and Implementing a Cyberwar Laboratory Exercise for a Computer Security Course. In Proceedings of the 35th SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, SIGCSE ’04, Norfolk, VA, USA, 3–7 March 2003; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doupe, A.; Egele, M.; Caillat, B.; Stringhini, G.; Yakin, G.; Zand, A.; Cavedon, L.; Vigna, G. Hit’em Where It Hurts: A Live Security Exercise on Cyber Situational Awareness. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference ACSAC ’11, New York, NY, USA, 5–9 December 2011; pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohio Cyber Range Institute. Available online: https://www.ohiocyberrangeinstitute.org (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- NIST. National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE)—The National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework; NIST: Gaithersburg, MA, USA, 2017.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Workforce Framework for Cybersecurity (NICE Framework); Technical Report NIST SP 800-181r1; Revision 1; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Barrett, M. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity Version 1.1; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Freund, J.; Jones, J. Measuring and Managing Information Risk: A FAIR Approach; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chidukwani, A.; Zander, S.; Koutsakis, P. A Survey on the Cyber Security of Small-to-Medium Businesses: Challenges, Research Focus and Recommendations. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 85701–85719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, E.; Simpson, A. Risk and the Small-Scale Cyber Security Decision Making Dialogue—A UK Case Study. Comput. J. 2017, 61, 472–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms–Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) Definition; OECD: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, R.; Santos, D.; Wetzel, K.A.; Smith, M.C.; Witte, G. Workforce Framework for Cybersecurity (NICE Framework); Technical Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020.

- Kim, K.; Smith, J.; Yang, T.A.; Kim, D.J. An Exploratory Analysis on Cybersecurity Ecosystem Utilizing the NICE Framework. In Proceedings of the 2018 National Cyber Summit (NCS), Huntsville, AL, USA, 5–7 June 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bada, M.; Nurse, J.R.C. Developing cybersecurity education and awareness programmes for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Inf. Comput. Secur. 2019, 27, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobey, D.; Watkins, A.; O’Brien, C. Applying Competency-Based Learning Methodologies to Cybersecurity Education and Training: Creating a Job-Ready Cybersecurity Workforce. Infragard J. 2018, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel, K. NICE Framework Competencies: Assessing Learners for Cybersecurity Work; Technical Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021.

- Verizon. 2022 Data Breach Investigations Report; Technical Report; Verizon: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ponemon Institute. 2019 Global State of Cybersecurity in Small and Medium-Sized Businesses; Technical Report; Ponemon Institute: Traverse City, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CISA. CISA INSIGHTS; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Hiscox Group. Cyber Readiness Report 2022; Technical Report; Hiscox Group: Pembroke, Bermuda, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ENISA. Cybersecurity for SMEs—Challenges and Recommendations; Technical Report; ENISA: Heraklion, Greece, 2021.

- ENISA. ENISA Threat Landscape 2020—Web-Based Attacks; Technical Report; ENISA: Heraklion, Greece, 2022.

- ENISA. ENISA Threat Landscape 2020—List of Top 15 Threats; Technical Report; European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA): Heraklion, Greece, 2020.

- Campos, R.; Mangaravite, V.; Pasquali, A.; Jorge, A.; Nunes, C.; Jatowt, A. YAKE! Keyword extraction from single documents using multiple local features. Inf. Sci. 2020, 509, 257–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CISA. Capacity Enhancement Guide: Counter-Phishing Recommendations for Non-Federal Organizations; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- CISA. Capacity Enhancement Guide: Counter-Phishing Recommendations for Federal Organizations; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Website Security; CISA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC). Ransomware Prevention Guide; Technical Report; Australian Cyber Security Centre: Canberra, Australia, 2022.

- National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). Mitigating Malware and Ransomware Attacks; National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC): London, UK, 2021.

- Souppaya, M.; Scarfone, K. Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling for Desktops and Laptops; Technical Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2013.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). ENISA Threat Landscape 2020—Web-Based Attacks; Technical Report; European Union Agency for Cybersecurity: Heraklion, Greece, 2020.

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Cybersecurity for Small Business: Phishing; Technical Report; Federal Trade Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Guidance for Managed Service Providers and Small- and Mid-Sized Businesses; Technical Report; Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Chen, C. Science Mapping: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2017, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, S.; Lee, G. Development and application of a keyword-based knowledge map for effective R&D planning. Scientometrics 2010, 85, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhar Manesh, M.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Marzi, G.; Dabic, M. Knowledge Management in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Mapping the Literature and Scoping Future Avenues. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 68, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hu, L.; Li, S.; Li, T.; Li, H.; Chi, L. A Review of Unsupervised Keyphrase Extraction Methods Using Within-Collection Resources. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenshtein, V.I. Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions, and reversals. Sov. Phys.-Dokl. 1965, 10, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, W.E. String Comparator Metrics and Enhanced Decision Rules in the Fellegi-Sunter Model of Record Linkage; Technical Report; Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC): Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hamming, R.W. Error detecting and error correcting codes. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1950, 29, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetya, D.D.; Wibawa, A.P.; Hirashima, T. The performance of text similarity algorithms. Int. J. Adv. Intell. Inform. 2018, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies (NICCS). NICE Framework Keyword Search. Available online: https://niccs.cisa.gov/tools/nice-framework (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Bada, M.; Sasse, A.M.; Nurse, J.R.C. Cyber Security Awareness Campaigns: Why do they fail to change behaviour? arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.02672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaifar, A.; Fricker, S.A.; Gwerder, M. Automating the Communication of Cybersecurity Knowledge: Multi-case Study. In Proceedings of the Information Security Education. Information Security in Action, Maribor, Slovenia, 21–23 September 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 110–124. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, S.; Chen, X. Cross-Disciplinary Team Learning: Assessment Guidelines. In Proceedings of the EPICS Annual Conference on Service-Learning in Engineering and Computing, Austin, TX, USA, 3–4 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Global Investigations Review. The Guide to Cybersecurity Investigations, 2nd ed.; Global Investigations Review: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://globalinvestigationsreview.com/guide/the-guide-cyber-investigations-archived/first-edition/article/the-cyber-threat-landscape (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Chesney, R. Cybersecurity Law, Policy, and Institutions (Version 3.1); Technical Report; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Darknet Diaries. Russia vs. Ukraine: The Biggest Cyber Attack Ever. Darknet Diaries Ep. 54: NotPetya. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N20q-ZMop0w (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- The Sedona Conference. Incident Response Guide. 2020. Available online: https://www.thesedonaconference.org/sites/default/files/publications/IncidentResponseGuide.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- WannaCry: The World’s Largest Ransomware Attack. Video, YouTube. 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PKHH_gvJ_hA (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- WannaCry Ransomware CyberAttack Raises Legal Issues. The National Law Review, 22 May 2017. Available online: https://natlawreview.com/article/wannacry-ransomware-cyberattack-raises-legal-issues (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Schmitt, M.; Fahey, S. WannaCry and the International Law of Cyberspace. Just Security, 22 December 2017. Available online: https://www.justsecurity.org/50038/wannacry-international-law-cyberspace/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Hooked By Phisherman: Quarterbacking Breach Response with Law Enforcement. Presentation at RSA Conference. 2021. Available online: https://www.rsaconference.com/library/Presentation/USA/2021/hooked-by-phisherman-quarterbacking-breach-response-with-law-enforcement (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Global Investigations Review. The Guide to Cybersecurity Investigations, 3rd ed.; Global Investigations Review: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://globalinvestigationsreview.com/guide/the-guide-cyber-investigations/third-edition (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- BakerHostetler. U.S. Data Breach Notification Law Interactive Map. Available online: https://www.bakerlaw.com/us-data-breach-interactive-map/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Kroah-Hartman, G. Keynote: Spectre, Meltdown, & Linux. Video, The Linux Foundation/YouTube. 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lQZzm9z8g_U (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Simpson, A.P.; Solomon, A.H. Complying with Breach Notification Obligations in a Global Setting: A Legal Perspective. In The Guide to Cyber Investigations, 3rd ed.; Global Investigations Review: London, UK, 2019; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Celerium. The Complete Guide to Understanding Cybersecurity Frameworks. Available online: https://www.celerium.com/cybersecurity-frameworks-a-comprehensive-guide (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Thomson Reuters. Performing Data Security Risk Assessments Checklist. Practical Law/Thomson Reuters. 2018. Available online: https://mena.thomsonreuters.com/content/dam/ewp-m/documents/mena/en/pdf/other/data-security-risk-assessments-checklist-thomson-reuters.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Basu, A.; Grover, G. Scenario 24: Internet Blockage; International Cyber Law Toolkit, NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence; NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence: Tallinn, Estonia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- RSA Conference. Cyber and Modern Conflict: The Changing Face of Modern Warfare. Session Presented at RSA Conference. 7 June 2022. Available online: https://www.rsaconference.com (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Kushner, D. The Hacker Who Cared Too Much. Rolling Stone, 29 June 2017. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/the-hacker-who-cared-too-much-196425/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Darknet Diaries. Ep. 14: OpJustina. YouTube Video. 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0qvBYj7F3jo&list=PLtN43kak3fFEEDNo0ks9QVKYfQpT2yUEo&index=14 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). YouTube Video. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPr6hZfoBfQ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Burt, T. Microsoft Takes Court Action Against Fourth Nation-State Cybercrime Group. Microsoft (On the Issues Blog). 30 December 2019. Available online: https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2019/12/30/microsoft-court-action-against-nation-state-cybercrime/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Complaint for Civil Action No. 1:19-cv-01582 (LO/JFA). United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Alexandria Division, 2019. Available online: https://noticeofpleadings.com/thallium/files/FINAL%20COMPLAINT.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- The CyberWire. Taking Down Thallium. YouTube Video. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGC-UwKVkYc (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Lubin, A.; Marinotti, E. Why Current Botnet Takedown Jurisprudence Should Not Be Replicated. Lawfare. 2024. Available online: https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/why-current-botnet-takedown-jurisprudence-should-not-be-replicated (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Microsoft. Microsoft Security Bulletin, (n.d.). Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/security-updates/securitybulletins/2017/ms17-010 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- U.S. Congress. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996; Enacted by the 104th U.S. Congress on August 21, 1996; U.S. Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Meltdown and Spectre, (n.d.). Available online: https://meltdownattack.com/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Powell, B.A.; Mercer, S.T. (Eds.) The Guide to Cyber Investigations, 3rd ed.; Global Investigations Review: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, N.; Wills, G. The VoIP PBX Honeypot Advance Persistent Threat Analysis. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security, Online, 23–25 April 2021; pp. 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]