Abstract

This study combines a multidisciplinary approach to Pyrenean and Alpine glacial lakes to characterize the sensitivity of Late Glacial to Holocene subaquatic flood deposits in deltaic environments to slope failures triggered either by earthquakes, rockfalls, or snow avalanches. To clarify the possible interactions between environmental changes and these natural hazards in mountain and piedmont lakes, we analyze the lacustrine sedimentary records of key historical events and discuss the recurrence of similar regional events in the past. High-resolution seismic profiles and sediment cores from large perialpine lakes (Bourget, Geneva, and Constance) and from small mountain lakes in the French Alps and the Pyrenees were used to establish a conceptual model linking environmental changes, tributary flood sedimentary processes, subaquatic deltaic depocenters, and potentially tsunamigenic mass-wasting deposits. These findings illustrate the specific signatures of the largest French earthquakes in 1660 CE (northern Pyrenees) and in 1822 CE (western Alps) and suggest their recurrence during the Holocene. In addition, the regional record in the Aiguilles Rouges massif near Mont Blanc of the tsunamigenic 1584 CE Aigle earthquake in Lake Geneva may be used to better document a similar Celtic event ca. 2300 Cal BP at the border between Switzerland and France.

1. Introduction

Natural hazards are closely linked to climate change, and both are critical drivers of global terrestrial and marine environmental changes, but our forecasting ability is poor, and further research is needed. In order to better understand the impact of natural hazards on society, it is required to study each type of event considering not only the triggering factors but also the interactions between natural hazards based on a multi-hazard approach [1].

Erosion of the Earth’s surface—including soil erosion and the resulting sedimentation—constitutes a major natural hazard that produces significant social and economic losses because it occurs in all climatic conditions and on slopes of all types and uses. Increased human activity during the Anthropocene has impacted soil, sediment, and water quality, as well as landscape erosion rates and river dynamics, thereby affecting sedimentation rates in lakes, reservoirs, and marine deltas. Worldwide, erosion of the Earth’s surface is impacting plant growth, streams, and reservoir sedimentation and is often the cause of many water management problems [2,3,4,5]. Erosion of the Earth’s surface in mountain ranges is particularly influenced by glacier activity in drainage basins, snowmelt, and/or land use [6,7,8,9]. It directly and significantly increases the suspended sediment load in rivers during floods, driving sedimentation processes in subaquatic (natural or artificial) deltaic environments [10], as illustrated in Figure 1.

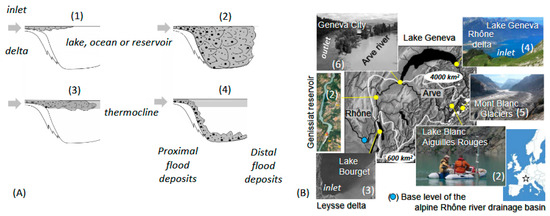

Figure 1.

Drawings (A) and pictures (B) illustrating the types of flows occurring during a flood event, based on the density difference between the tributary and the receiving basin: hypopycnal (1), homopycnal (2), mesopycnal (3), and hyperpycnal (4). Illustrations in (B) from the western Alps (white star) drainage basin of the Alpine Rhone River (Switzerland/France) show how sediments eroded by glaciers (5) can be transported by fine-grained suspended sediment load in fluvioglacial streams (6), resulting in homopycnal flows (2) and turbid waters in mountain lakes and reservoirs, mesopycnal (3) or hyperpycnal flows (4), and associated sediment plumes in the downstream lacustrine deltas. In mountain ranges, snowmelt and heavy rainfall can also cause erosive flash floods and large sediment plumes (2, 3, 4, and 6) in lakes. The alpine base level of the Rhone River in the southern Jura anticline is indicated by a blue circle. The IGN aerial photograph of a sediment plume in Lake Bourget, originating from the Leysse delta and illustrated in (B), is located in the southern part of the lake. The IGN aerial photograph of the Genissiat reservoir is from Geoportal (URL www.geoportail.gouv.fr, accessed on 11 February 2025).

Quaternary glaciations in mountain ranges resulted in the formation of numerous small glacial lakes at variable altitudes [7,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] and large glacial valleys now characterized worldwide by deep lakes, fjords, or thick Quaternary deposits of glacial, lacustrine, or fluvial origin [9,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In western Europe, Holocene climate change in the Jura mountains and the Alps (Figure 2) impacted erosion rates and favored sediment waves in alpine drainage basins, modulating river geomorphology (e.g., progressive downstream development of braided river patterns) and piedmont lake sedimentation (higher lake levels; more frequent and thicker flood deposits) during wetter periods characterized by strong westerlies over the Atlantic Ocean [31,32,33,34,35].

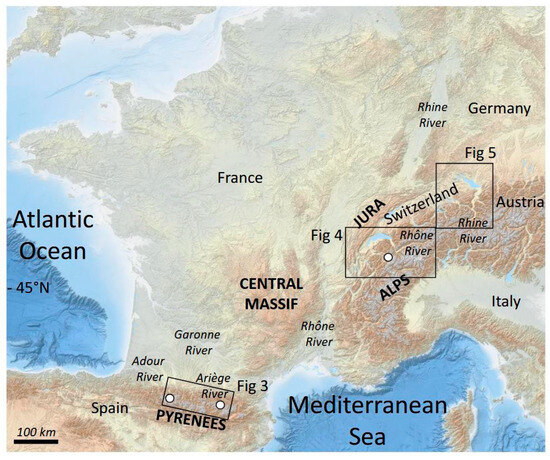

Figure 2.

General location of the study areas in the northern Pyrenees and the western and northern Alps, within the watersheds of the Garonne, Rhone, and Rhine Rivers. The small mountain glacial lakes investigated (white circles) and the large perialpine glacial lakes Bourget, Geneva, and Constance have been exposed to a wide range of natural hazards since the last deglaciation.

The population and infrastructure are also exposed to potentially catastrophic geological events at tectonic plate boundaries, along active faults and within mountain ranges. Short historical records, and even shorter instrumental records of extreme natural hazards worldwide, have shown that strong earthquakes, for example, can be accompanied by regional landslides impacting hydro systems, tsunamis (in both oceans and lakes), outburst floods, and even volcanic eruptions [19,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Considering the high vulnerability of lake shores and glacial valleys due to high population density and associated infrastructure, meticulous studies are needed to assess geological hazards in a changing world.

There are many attractive European glacial lakes in Scandinavia, the Alps, and the Pyrenees because they vary in terms of their altitude, size, depth, tributaries, and drainage basins. Previous studies have shown that these mountain regions have been subjected to a wide range of natural hazards since the last deglaciation: erosive snow avalanches [10,12,14,44,45], large rockfalls [24,29,30,46,47,48,49], strong earthquakes [7,13,16,50,51], lake tsunamis [29,48,52], and standing oscillatory waves (i.e., seiche waves; see [43,53,54]).

In this study, we review and document how sedimentary records in Pyrenean and Alpine lakes are sensitive environmental archives of cascading natural hazards. Based on a similar multidisciplinary approach developed in (small and large) Alpine lakes and hydroelectric Pyrenean reservoirs over the last decades (Supplementary Figure S1), we apply a multi-hazard approach and discuss historical and prehistorical regional event stratigraphy associated with large (and sometime catastrophic) floods, earthquakes, and/or rockfalls in drainage basins and lakes exposed to rapid environmental changes following the last deglaciation, the neoglacial period (including the Little Ice Age (LIA)), and the Anthropocene. The aim of this study is to further illustrate and explain how environmental changes in mid-latitude mountain ranges are conditioning the sensitivity and instability of glacial lakes and their sediments not only to earthquake hazards but also to cascading natural hazards resulting from landslides, flooding, or snow avalanches.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

In the European Alps, pioneering deep geophysical investigations of the largest perialpine lakes in France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, and Italy [55] and several key site studies (such as Lake Bourget, France) with a dense grid of seismic reflection data within the lake basin allowed us to establish the detailed seismic stratigraphy of glacial lakes following the last deglaciation [56]. These acoustic data were calibrated only by long lake drilling in Zurich (Switzerland) and Annecy (France), providing a conceptual model of radiocarbon-dated sedimentological and geomorphological reconstructions resulting from glacial to interglacial environmental changes [57]. In the meantime, sub-bottom profiling using high-resolution seismic sources (3.5 kHz pinger and later modulating chirp sources) was similarly calibrated using gravity or piston cores in either large piedmont lakes [36,53,58] or small mountain lakes across the Alps to document environmental changes and Holocene natural hazards [7,11,13,15,48,50,51].

However, across the Pyrenees, the available reconstructions of paleoclimate conditions and environmental changes from the last climatic cycle are solely based on glacial geomorphology and geochronology, or on multiproxy studies of sediment cores from lakes and paleolakes [59,60]. Until now, the combination of high-resolution seismic mapping and multiproxy analysis of sediment cores has only been carried out in a glacial lake flooded by a hydroelectric dam in the Ariège Massif (Figure 2) to document mid-Holocene sedimentation changes associated with climate variability and human activities [14].

2.1.1. Northern Pyrenees

As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the northern Pyrenees are characterized by several main glacial valleys draining the Ariège, Garonne, and Adour Rivers towards the Atlantic Ocean. Today, only a few cirque glaciers, small glacial lakes, and moraines from the late glacial to the early and late Holocene have been documented and dated at the heads of these drainage basins [17,18,61,62]. At the edge of the piedmont, large and thick paleolake sedimentary infills within these flat fluvio-glacial valleys have also been documented based on gravity data [23,63].

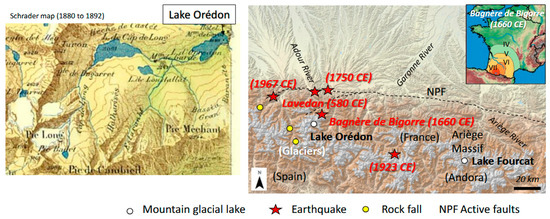

Figure 3.

Location of Pyrenean mountain lakes Orédon and Fourcat within the Garonne and Ariège Rivers’ drainage basins. The North Pyrenean Fault (NPF) and other active faults (dotted lines), together with the years of historical earthquakes and their likely epicenters (red stars) and large rockfalls (yellow circles), are indicated according to [49]. The extension of the 21 June 1660 CE Bagnère-de-Bigorre earthquake intensity is also illustrated in roman numbers (right panel) were red area (intensity VII), orange area (intensity VI), yellow area (intensity V) and green area (intensity IV) are indicated. As shown on the old topographic map (left panel), Lake Orédon drained several glaciers and glacial lakes during the Little Ice Age. These natural lakes were later flooded by hydroelectric dams, as detailed in the text.

This part of the Pyrenees is characterized by moderate seismic activity, although several strong historical earthquakes have clustered next to the North Pyrenean Fault (NPF), which illustrates that this major thrust fault system and other connected faults are active [49,64,65]. One of the most destructive Pyrenean earthquakes occurred in the Central Pyrenees, on 21 June 1660 CE (Figure 3), with an epicentral intensity of VIII–IX on the MSK scale (1964), near Bagnère-de-Bigorre, and its magnitude is estimated to be equivalent to Mw 6.1. Several large landslides and rockfalls have also been identified in the Central Pyrenees (Figure 3). According to [49], the age of a large and deep-seated landslide points to a single event back in 580 CE (the Lavedan earthquake, poorly documented by the bishop and historian Grégoire de Tours [66]). Undated large rockfalls in the Troumouse cirque suggest geological control combined with ice wastage and the migration of headwall weathering zones [62,67]. Between these two sites, the undated Coumely rockfall, a touristic site on the road towards the UNESCO-listed Gavarnie and Troumouse cirques, could also have resulted from the 580 CE Lavedan earthquake [68].

Lake Orédon (46 hectares (ha) and 1 km long) is one of the largest glacial lakes (together with Lake Cap de Long) in Pyrenees National Park in the Néouvielle massif. It drains into the Neste d’Aure River, a tributary of the Garonne River (Figure 3). Old topographic maps and pioneer studies from this region highlighted the occurrence of several glaciers in the upper catchment area, culminating at an altitude of 3194 m at the end of the Little Ice Age (LIA) [66]. Up to three high mountain streams draining two lakes and contrasted geological formations (granites and sedimentary rocks) build a delta in the SW part of Lake Orédon [69]. This lake was 35 m deep [70] before the construction of a dam in 1880 CE, which increased its depth to 59 m, when the first bathymetric map was produced [71]. Since then, the lake level has fluctuated (+/− 24 m) above a minimum altitude of 1832 m above sea level (asl) to produce hydroelectricity. Since the mid-19th century, the first temporary dams have been used to facilitate wood transport during summers from the lake shore to the town of St Lary located downstream of the Neste d’Aure River at 830 m asl [72]. Successive dams have been built downstream of Lake Cap de Long since 1909. In 1953, the largest hydroelectric reservoir in the northern Pyrenees completely flooded the lakes of Cap de Long and Loustallate, visible in Figure 3. A road was built upstream from Lake Orédon to reach Lake Cap de Long. Galleries were also drilled toward the west (into the Adour River drainage basin; Figure 2) to export water and produce hydroelectricity using a penstock [72]. In 1971, additional galleries were constructed to connect the Aumar and Aubert hydroelectric reservoirs (previously glacial lakes that drained into the NE part of Orédon) to increase the storage capacity of the Cap de Long reservoir [73]. Since this period, the Cap de Long hydroelectric infrastructure has been modulated according to water storage capacities and agriculture needs within the Garonne River watershed. However, globally, it has drastically reduced the water and sediment supply to the Orédon reservoir [74]. The first gravity cores retrieved from Lake Orédon were dated (by radionuclides and radiocarbon) and analyzed to document the evolution of atmospheric pollution since the Late Holocene [73].

Lake Fourcat is a small (24 ha, 500 m long), 63 m deep glacial lake located in the Vicdessos valley in the Ariège massif (Figure 3) at 2412 m asl. Since 1917, when a small dam was built, it has provided water and energy for the aluminum industry at Auzat (740 m asl). It has a small tributary delta draining the Fourcat glacial cirque, culminating at 2859 m asl (forming a natural border between France and Spain), and Lake Oussade (2.9 ha, unknown water depth), located at 2495 m asl. According to the 10Be age of a roche moutonnée damming the upper Picot Lake located at 2424 m asl in the Picot cirque, just next to the Fourcat cirque [17], it is likely that Lake Fourcat was formed around 8.4 +/− 0.2 thousand years ago (kyr).

2.1.2. Western Alps

The western Alpine range (in France, Switzerland, and Italy), together with the Molasse Basin and the Jura Mountains (Figure 4), was covered by ice during the last glaciation. Following deglaciation, thick lacustrine and deltaic sequences were deposited in numerous over-deepened lake basins draining multiple cirque glaciers in the Alpine glacial valleys, where the Rhone, the Arve, and the Isère Rivers now flow, forming fluvio-glacial and alluvial plains [75]. All these flat French and Swiss Alpine valleys reflect the development of very large paleolakes, as documented by drilling and seismic reflection profiles on land [28,76]. This part of the Alps is also characterized by the large perialpine lakes Geneva, Annecy, Bourget, Aiguebelette, and Paladru (Figure 4).

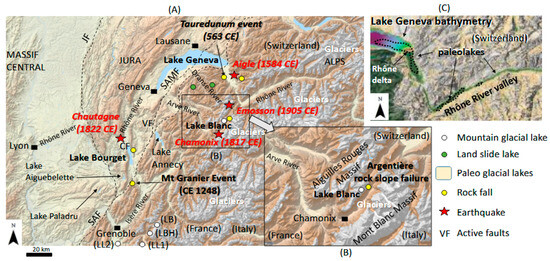

Figure 4.

Geological setting of the western Alpine glacial lakes and main cities (square black boxes) within the Rhone River drainage basin (A). Location of Lake Blanc in the Aiguilles Rouges Massif (B). Quaternary sediment infill in the Rhone valley and multibeam bathymetry of Lake Geneva (URL www.swisstopo.ch, accessed on 19 May 2025) reflect several paleolakes (black arrows) in (C), where the black dotted lines indicate sediment infill more than 700 m thick according to [26] and the purple color in Lake Geneva illustrate its bathymetry below 300 m. Lake Geneva crosses the Sub-Alpine Molasse Front (SAMF) in the Tertiary Molasse basin (between the Jura and the Alpine foreland) and partly the Sub-Alpine (frontal thrust) Fault (SAF). Lake Bourget formed at the contact between the SAF and the first Jura folds, developing a large plateau towards the north between the Jura (frontal thrust) Fault (JF) and the Molasse Basin. The Culoz fault (CF) and Vuache fault (VF) are documented strike-slip active faults. Strong Swiss and French historical earthquakes and rockfalls recorded in these lakes are located and discussed in the text. The location of the mountain lakes Bramant (BRA), Blanc Huez (LBH), Lauvitel (LL1), and Laffrey (LL2) is also discussed in the text.

The well-known Lake Geneva (582 km2, 72.8 km long and 309.7 m deep), the largest European lake, is located at 372 m asl at the French and Swiss border, between the Jura and Subalpine massifs. Its central deepest basin occurs just at the subalpine frontal thrust front and constitutes a sediment sink for the (Swiss) Rhone (ca. 5220 km2) and (French) Dranse (ca. 495 km2) Rivers’ catchment areas. Lake Geneva is a large proglacial lake, draining several large Swiss glaciers including the Aletsch (128 km2) and the Rhone (17 km2) glaciers via the Rhone delta. In the city of Geneva, the outflowing waters of Lake Geneva quickly mix with the confluence of the Arve River (Figure 1), draining up to 2074 km2, including the Aiguilles Rouges and the French part of the partly glaciated Mont Blanc Alpine massifs [33]. Lake Blanc (2 ha) is one of the small glacial lakes in the Aiguilles Rouges Massif (Figure 4). This proglacial lake is 10 m deep and lies at 2352 m asl at the foot of a ca. 1 km2 cirque where the Belvédère Glacier has developed glacial deposits [13]. Lake Bourget (44.5 km2, 19 km long and 145 m deep) is the largest natural lake in France. It is located at 231 m asl in the southern-most syncline of the Jura mountains, between two anticlines, at the foot of the subalpine frontal thrust front (Figure 4). This fjord lake has been draining since ca. 10,000 years into the Rhone River, and it has two permanent tributaries draining the surrounding subalpine massifs slopes: the Leysse (306 km2) and the Sierroz (157 km2) Rivers [34]. However, prior to this period, the Rhone River had not yet filled the northern part of the postglacial lake and was its main tributary [31,75]. Since then, only large Holocene Rhone River floods have overflowed the Chautagne Swamp and entered Lake Bourget, increasing its lake level and its drainage basin up to ca. 4000 km2, as illustrated in Figure 1 and further detailed in [31,33,34]. Lakes Bourget and Annecy are also closely connected to NW-SE active strike-slip faults (the Culoz and Vuache faults, respectively), and the area is characterized by moderate seismicity. One of the strongest regional earthquakes occurred on 18 February 1822 at the Culoz fault below the Chautagne swamp, just north of Lake Bourget, with an epicentral intensity of VII–VIII on the MSK scale (1964), and its magnitude is estimated to be equivalent to Mw 5.5–6.0 [43,54]. This Chautagne event triggered multiple coeval subaquatic landslides and a seiche deposit in the deep central basin of Lake Bourget. The Aigle (1584 CE, Mw 5.9), Chamonix (1817 CE, Mw 4.8), and Emosson (1905 CE, Mw 5.5) earthquakes (Figure 3) were also regional events [13]. In addition, this part of the Alps has been exposed to well-documented historical catastrophic rockfall events and their consequences: the tsunamigenic Tauredunum major event (563 CE) near Lake Geneva [48,77]; the ca. 24 km2 and 5100 m3 Mont Granier event (1248 CE) [78]; the artificial Casquette event across the railway in 1973 at the shore of Lake Bourget [75]; and the ongoing Late Holocene Argentière rock slope failure in the Aiguilles Rouges massif, which constitute a future major risk for the upper Arve valley and Chamonix city [79]. Finally, two rockfalls evolving into landslides in the Dranse River drainage basin formed Lake Montriond ca. 500 years ago and Lake Vallon in March 1943 [80].

2.1.3. Northern Alps

The northern Alpine ranges at the crossroads of Switzerland, Germany, Austria, and Liechtenstein (Figure 5) were also covered by ice during the last glaciation, and large alpine glacial lobes reached the Molasse Basin. Following deglaciation, large perialpine lakes formed in over-deepened basins at the piedmont (Lakes Zurich and Constance) and within glacial valleys (Lakes Lucerne and Walen). Large and thick paleolake deposits developing flat valleys are also documented at the edges of these lakes, especially in the Rhine River valley upstream from Lake Constance [28]. The source of the Rhine is in the Alps at 2341 m asl, and this river is the main tributary of Lake Constance (536 km2, 63 km long and 251 m deep) at 395 m asl. This well-documented proglacial lake is the third largest in Europe and has a drainage basin of 11,500 km2 at the border of Switzerland, Germany, and Austria.

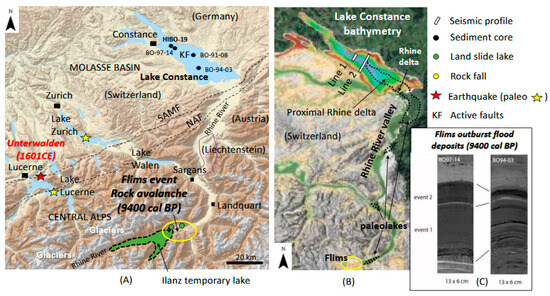

Figure 5.

Geological setting of the northern and central perialpine glacial lakes and main cities (Black square boxes) within the Rhine River drainage basin illustrating the schematic location of the Flims landslide deposit and the induced Ilanz temporary lake (A). Quaternary sediment infill in the Rhine valley and multibeam bathymetry of Lake Constance (URL from www.swisstopo.ch, accessed on 19 May 2025) reflect several paleolakes (black arrows), where the black dotted lines indicate sediment infill exceeding 700 m in thickness, according to [26] (B). The published 3.5 kHz seismic profiles (Lines 1 and 2), and the location of published long sediment cores from the deep central basin (black dots) used in this study, are located on the bathymetric map of Lake Constance, where the 100 m isobath marks the limit between the green- and blue-colored slopes. Pictures of the Flims outburst flood deposits in Lake Constance (C), discussed in the text, are from [10,30]. The well-documented Rhine delta of Lake Constance lies north of the Sub-Alpine Molasse Front (SAMF) and the Northern Alpine Front (NAF).

On 18 September 1601 CE, Central Switzerland was hit by the Unterwalden earthquake, one of the largest historical earthquakes in Central Europe (Mw = 6.2). This event, located at the North Alpine front, triggered multiple subaquatic slides, rockfalls, and tsunami waves, resulting in well-documented seiche waves in Lake Lucerne [36,52,53,81,82]. The Rhine valley was also hit around 9400 Cal BP by the largest rockslide (ca.12 km3) in the Alps and in Europe: the Flims event. This evolved downslope into a rock avalanche deposit that formed a temporary dam across the Rhine valley (the Ilanz lake, Figure 5) and outstanding outburst Rhine River flood deposits in the deep basin of Lake Constance [10,46,83,84,85,86,87].

2.2. Methods

A similar limnogeological approach combining acoustic mapping and multi-proxy studies of sediment cores was developed for the glacial lakes Fourcat, Orédon, Blanc, Bourget, Geneva, and Constance, as detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

The Pyrenean lakes Fourcat and Orédon were mapped, as shown in Figure 6, with the portable Knudsen pinger sub-bottom profiler. This device combines a high-frequency (200 kHz) transducer for mapping the bathymetry and a low-frequency (4 kHz) chirp source with a broadband hydrophone receive array for imaging the basin fill geometry in high resolution. The system is connected to a digital acquisition unit plugged to a laptop computer and a GPS onboard an inflatable boat. These data were calibrated in the field using an IKATEC gravity core. In the laboratory, the cores ORE-15A and FR14-A were stored in a cold room (4 °C) in Toulouse, split in two halves, and carefully described based on visual inspection and measurements of sediment stratigraphy (X-ray radiography) and geochemistry using the X-ray florescence (XRF) core scanner (ITRAX, Cox Analytical Systems: Mölndal, Sweden) in a U-channel at CEREGE (Aix en Provence). This scanning operation used a molybdenum target tube set to 30 kV and 25 mA. Acquisition of continuous XRF was performed at a 2 mm scale with an exposure time of 15 s. This method measures changes in the abundance of elements (K, Zr, Si, Ca, Ti, Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn, Br, Rb, Sr) along the sedimentary sequence. The XRF signal incoherence/coherence (Inc/Coh) is known to be a good proxy for organic matter in lake sediments [12]. In the Fourcat and Orédon cores, the organic matter was also quantified using discrete sediment sampling, and the content was measured and characterized by Rock-Eval pyrolysis at ISTO (Orléans), following the methods described in [6,7,14]. Recent sedimentation rates in these cores were determined based on 210Pb, 137Cs, and 241Am vertical profiles (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3) acquired using low background HPGe gamma spectrometers placed under 85 m of rock at the LAFARA underground laboratory [88]. Three AMS radiocarbon ages from organic macro remains were determined at Beta Analytics Radiocarbon Laboratory (Miami, FL, USA) and were used to establish the chronology of core ORE-15A (Supplementary Table S4).

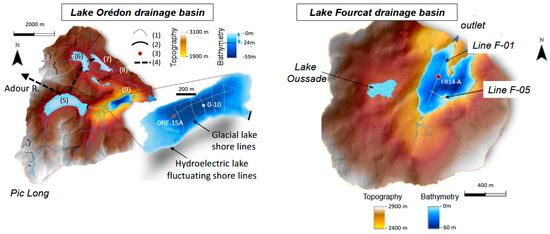

Figure 6.

Geomorphological setting, bathymetry, seismic grid, and coring sites of the Pyrenean lakes Orédon and Fourcat. (1) Little Ice Age moraines, (2) hydroelectric dam, (3) sediment core, (4) penstock, (5) Lake Cap de Long, (6) Lake Aubert, (7) Lake Aumar, (8) Lake Laquette, and (9) Lake Orédon.

Alpine Lake Blanc was similarly mapped with the portable Inomar parametric sub-bottom profiler. The transducer was used with an 8 kHz chirp signal, connected to an acquisition unit, a GPS, and a laptop computer, as shown in Figure 1. These data were interpreted and used to optimize the coordinates of a coring site. An UWITEC gravity corer and a piston corer (both 63 mm diameter) were used from the frozen surface of the lake during the winter of 2009–2010. One gravity core (BAR09P1) and two piston cores (BAR10-I and BAR10-II) were collected. A 250 cm long synthetic log was built for core BAR10-II based on sedimentary facies together with laser grain size, GEOTEK core logger measurements (magnetic susceptibility, gamma density, P waves velocity, video capture, and spectrophotometry), and Avaatech XRF core scanning, as detailed in [13]. Up to nine AMS radiocarbon ages from macro-remains were obtained at the LMC14 laboratory (Saclay, France), together with 137Cs underground measurements at the LGGE (Grenoble, France), in order to establish BAR10-II chronology. In addition, sedimentological and seismic data were used to identify rapidly deposited layers (RDLs) and to establish a composite sediment age–depth model. This chronology allows for correlating four different RDLs with local and regional historical events (see below).

As summarized in Supplementary Table S1, Lake Bourget sedimentary infill was intensively investigated by a wide range of single-channel seismic profiles with variable resolutions between 1977 and 2015 [15,31,33,56,75,76,89,90], a side scan sonar survey in 1992 [54,75,90], and two complementary multibeam bathymetry surveys in 2008 and 2020 [15,43,91]. In 2015, the Knudsen pinger sub-bottom profiler was used with its 4 kHz chirp source to map the deepest central basin in order to compare the performance and seismic facies of different high-resolution devices (see below). Following the pioneer air gun seismic profile of Lake Bourget [55,76] (Supplementary Figure S2), a 7.5 m long piston core was retrieved in 1977 with the ETH Kullenberg corer in the deep central basin. Pictures of core LDB1977 were never published, but are archived at ETH Limnolab and are used in this study based on grayscale profiles of the sedimentary facies extracted from the digitalization of the original argentic pictures (see below). Up to 67 gravity cores were studied (38 retrieved with F.A. Forel Institute Benthos corer in 1997 [75] and 29 with the UWITEC corer from 2001 to 2017 [43,92]) from all the different sedimentary environments identified in Lake Bourget. Two of these gravity cores from the deep central basin (one Benthos core and one UWITEC core) were dated with radionuclides (210Pb and 137Cs) at LGGE, allowing the establishment of key chrono-stratigraphic markers related to the lake eutrophication (1940 CE), the 1822 CE earthquake triggered deposits, and the oldest-known historical flood deposit of the Rhone entering Lake Bourget (1732 CE) [54,75,92]. Long piston cores LDB01-1, LDB01-2, and LDB04 were taken in 2001, 2002, and 2004, respectively, within the depocenters of the Holocene Rhone River flood deposits visible on sub-bottom profiles [10,15,31,33,34,37,92] and dated by AMS radiocarbon [31,33,34] at the Poznan and Saclay laboratories (Supplementary Table S1). They were characterized by sedimentary facies, laser grain size, GEOTEK core logging (at ETH Zurich, Switzerland), and Avaatech XRF core scanning, as detailed in [31,33,34].

Figure 7, Supplementary Figure S2, and Supplementary Table S1 illustrate the compilation of vintage and new seismic data from the central basin of Lake Geneva used in this study: (i) analog air gun profiles L1 to L3 collected in 1969 (Figure 7A, [93]); (ii) analog air gun profiles collected close to profile L3 between the cities of Evian and Lausanne [55]; (iii) digital single-channel 500 J CENTIPEDE sparker (RCMG, Ghent, Belgium) data collected in 1996 and 1998, onboard R/V La Licorne, from Institut F.A. Forel and Geneva University (Figure 7B, [75]); (iv) the isopak map of lacustrine deposits (Figure 7A) from [94] based on EPFL digital multichannel air gun seismic surveys between 2000 and 2004; and (v) new digital sub-bottom profiles (Figure 7A) collected from surveys in June 2023 (Knudsen pinger 4 kHz chirp and EXAIL Echoes 10,000 compact (10 kHz chirp)) onboard transportable EXAIL (La Ciotat) R/V GGXIII and October 2023 (Knudsen pinger 4 kHz chirp) onboard INRAE (Thonon–les–Bains) R/V Daphnie. Six long piston cores were retrieved from this deep basin (Figure 7A) using the ETH Kullenberg corer in 1990 (cores J-34 and J-35, [95]) and in 2010 (cores Ku-I, Ku-II, Ku-IV, and Ku-V, [48,96]). The sedimentary sequence of core Ku-IV has been merged with the nearby UWITEC gravity core KK8 to create a composite record dated by radiocarbon [48,96], radionuclides (137Cs, 210Pb) [97], and paleomagnetism [98]. As shown in Figure 7, sedimentary facies, radionuclide, and radiocarbon data from cores J-34, together with Ku-I, Ku-II, and Ku-V, were used to calibrate the sub-bottom profile collected in 2023. These new sub-bottom data were also collected close to previously available seismic data (Figure 7A) and based on the 3.5 kHz pinger dataset from [41,96].

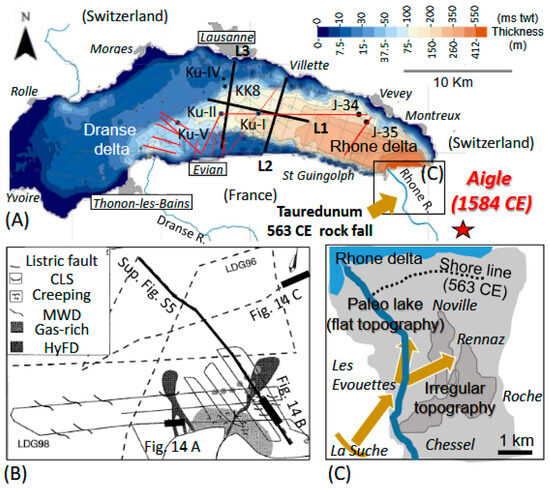

Figure 7.

Compilation of available geophysical and coring data from Lake Geneva’s central basin. (A) Isopack map (in millisecond (ms) two-way travel time (twt) and meters)—modified from [96]—of lacustrine sediments illustrating Dranse and Rhone deltaic depocenters from multichannel air gun seismic surveys (light gray lines), locating Swiss and French littoral towns; former coring sites (J-34, J-35 Ku-I, Ku-II, Ku-IV, Ku-V, and KK8). Single-channel air gun seismic lines from 1969 (black thick lines L1, L2, and L3), together with 4 kHz chirp lines from September 2023 (red lines) and chirp lines (4 kHz and 10 kHz) from June 2023 (red dotted lines), are illustrated in this study. The epicenter of the Aigle earthquake and the impact zone of the Tauredunum rockfall in the Swiss Rhone valley are located. (B) Sparker seismic surveys from 1996 (black dotted lines) and 1998 (black lines) mapping Dranse delta sedimentary environments (from [75]), illustrating gas-rich deposits exposed to gravity and flooding hazards: channel–levee system (CLS); hyperpycnal flood deposit (HyFD); mass wasting deposit (MWD). The location of the sparker profile interpretation illustrated in Supplementary Figure S5 is indicated by a bold black line. (C) Irregular topography of Rhone valley related to Tauredunum rockfall deposits at the edge of the lake shore line, according to [77].

Lake Constance’s main basin was also previously mapped using a wide range of acoustic data. This includes analog air gun [55]; analog 3.5 kHz pinger and side scan sonar [99,100]; and multibeam bathymetry, digital 3.5 kHz pinger, and digital multichannel air gun seismic profiles [85,87] calibrated by radiocarbon-dated Kullenberg and UWITEC piston coring in 1991, 1994, 1997, and 2019 [84,85,87], as illustrated in Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S1.

3. Results

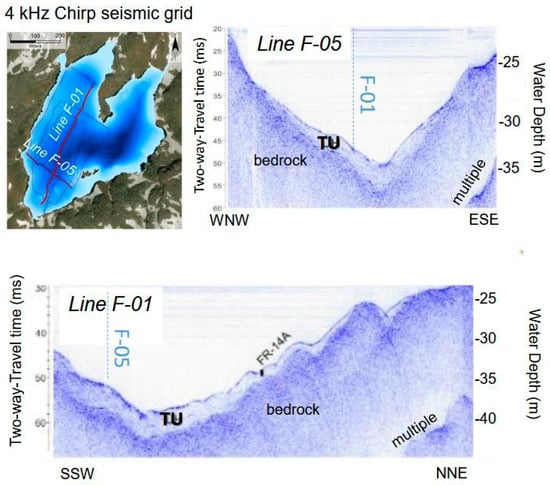

3.1. Lake Fourcat Seismic Stratigraphy

Lake Fourcat bathymetry, based on seismic data, is up to 36 m deep (applying a mean P wave velocity of 1.45 km/s in fresh water) in its western sub-basin (Figure 6 and Figure 8), but 60 m locally in the eastern basin [101]. The western basin is fed by a small tributary delta. On seismic profiles, the bedrock is clearly visible. It outcrops above ca. 21 m water depth (34 ms twt) along the western and eastern basin slopes (and at all the granitic shore lines) and towards the outlet. In front of the delta, a transparent unit (TU, Figure 8) is up to 4 ms twt thick and pinches out laterally along the steep bedrock slopes and toward the outlet. Assuming a mean Pw velocity of 1.5 km/s in lacustrine sediments, the TU is up to 3 m thick. At the FR-14A coring site, the TU is, however, only 2 ms twt thick (i.e., around 1.5 m).

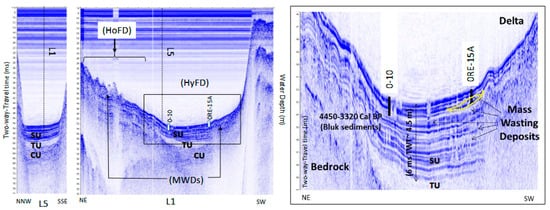

Figure 8.

Lake Fourcat seismic stratigraphy illustrating the acoustic facies of the bedrock below a transparent unit (TU) and the location of gravity core FR-14A.

3.2. Lake Orédon Seismic Stratigraphy

During the seismic survey in June 2015, Lake Orédon was low, and its bathymetry was only up to 38 m deep (Figure 9). Line 1 shows the paleo-delta of the natural glacial lake flooded by the hydroelectric reservoir, which is clearly visible on the SW lake floor. Below 30 m water depth (ca. 40 ms twt), the penetration of the chirp signal improves toward the central basin, and the bedrock is locally visible down to 66 ms twt along the basin axis. The bedrock outcrops along the western and eastern basin slopes above 52 ms twt (ca. 38 m water depth) and along the reservoir shorelines. On the lake floor, the sedimentary infill of Lake Orédon is composed of three seismic units. A chaotic to transparent basal unit (CU) between 66 and 61 ms twt is identified in the deepest part of the central basin. Above it, a transparent unit (TU) is identified in the deepest axial part of the basin (from 61 to 59 ms twt), pinching out at the steep western and eastern slopes and toward the outlet around 58 ms twt. The upper unit (SU) is characterized by stratified acoustic facies consisting of continuous high-amplitude and high-frequency reflections. This unit has a divergent geometry reaching up to 6 ms twt (ca. 4.5 m) toward the SW in the direction of the delta slopes and thinning toward the NE in the direction of the lake outlet. In this sector, the reflections become wavy and are interrupted locally (at depth and at the lake floor) by several lenses with chaotic to transparent facies. Thinner and smaller but similar lenses are also identified between the continuous and high-amplitude reflections of the basin depocenter at the edge of the delta slopes. The upper one was sampled by gravity core ORE-15A, and four others occurred at depth. Core O-10 was comparatively taken in the distal part of the basin, in a flat area where sediments are well stratified.

Figure 9.

Lake Orédon seismic stratigraphy illustrating the acoustic signatures of a chaotic unit (CU), a transparent unit (TU), and a stratified unit (SU) exposed to hyperpycnal flood deposits (HyFDs), homopycnal flood deposits (HoFDs), and mass-wasting deposits (MWDs). The locations of gravity cores O-10 and ORE-15A, discussed in the text, are also indicated. The upper MWD (yellow line) has been sampled in core ORE-15A.

3.3. Composition and Chronology of Lake Fourcat and Lake Orédon Sediments

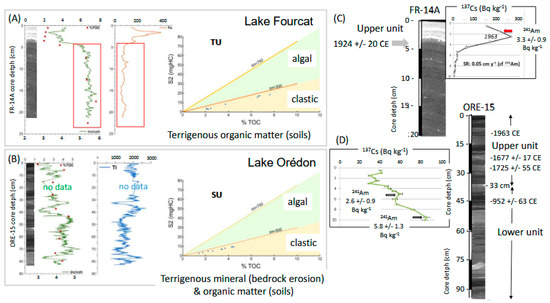

Recent sediments in Lake Fourcat highlight two contrasting sedimentary facies in core FR-14A (Figure 10). The upper facies (0–4.5 cm depth) is characterized by laminated dense sediments in X-ray images and by high values of Fe and a low inc/coh ratio in XRF data. Based on Rock-Eval measurements, this upper unit contains ca. 2% of total organic carbon (TOC). The lower unit (4.5 to 21.5 cm depth) is also laminated in X-ray images, but is less dense, contrasting with frequent small drop stones, locally developing several horizons (ca. 7 cm, 13 cm, and 20 cm core depth). This unit consists of organic-rich sediments (6 to 7% TOC), a higher inc/coh ratio, and a lower XRF intensity of Fe. Rock-Eval pyrolysis results represented by an S2 (mgHC/g, S2 = HI × TOC) versus TOC (%) diagram fall within the same area below the line (IH = 300 mgHC·g−1·TOC). This characterizes the terrigenous organic matter typical of soils [6,7,14]. The maximum content of 137Cs was identified within the upper unit between 2 and 3 cm core depth (Supplementary Table S2), together with traces of 241Am detected between 1 and 2 cm core depth (Figure 10). These radionuclides can be associated with the nuclear weapon tests culminating in 1963 CE in the Northern Hemisphere [6,7,14]. A mean sedimentation rate of 0.05 cm/yr can therefore be estimated for the upper unit and allows dating the transition to the lower unit to 1924 +/− 20 CE (considering that 1 cm of sediment sample corresponds to 20 years of sedimentation). Assuming that Lake Fourcat was formed around 8.4 kyrs and that the P wave velocity of the lower unit is ca. 1.5 km/s, it is likely that the 145 cm thick sedimentary sequence visible in seismic data accumulated with a mean sedimentation rate of 0.017 cm/yr.

Figure 10.

Recent sedimentation in Lakes Fourcat and Orédon. The characterization of lake sediments in the transparent unit (TU) from Lake Fourcat and in a stratified unit (SU) from Lake Orédon is based on X-ray image, XRF, and Rock-Eval data of sediment cores FR-14A (A) and ORE-15 (B). Sediment chronology in Lake Fourcat based on radionuclide (C) and both radionuclide and radiocarbon dating in Lake Orédon (D) detailed in Supplementary Tables S2–S4. Sediment samples with detected content in 241Am are indicated by a red arrow in Lake Fourcat and by black arrows in Lake Orédon as discussed in the text.

Recent sediments from Lake Orédon’s core ORE-15 are essentially laminated in X-ray images, and two different sedimentary facies can be detected (Figure 10). Between 0 and 33 cm core depth, the sediments are characterized in X-ray images by a succession of horizontal laminae with variable thicknesses and densities. From 33 cm to the base of the core (93 cm core depth), the sediments consist of an alternation of laminated deposits (between 35–43 and 48–55 cm core depth) and massif deposits (at 45–47 and 55–65 cm core depth). There are also layers made of discontinuous, tilted, or folded laminae (at 47–55 and 65–93 cm core depth). Drop stones are also detected in X-ray images around 25 cm and between 65 and 68 cm core depth. Due to the high water content and irregular sediment surface on the U-channel, it has not been possible to measure sediment XRF intensities correctly between 11 and 27 cm core depth (Figure 10). However, it is possible to distinguish the upper 33 cm of the sediment core from the lower part. The upper unit is characterized by Ti XRF intensity oscillating around 2000 and a fluctuating yet decreasing trend in TOC from 3 to 1 % between 33 cm core depth and the top of the core. The lower unit highlights more variable values of both the inc/coh ratio and Ti (between 1000 and 3000). On the S2 (mgHC/g, S2 = HI × TOC) versus TOC (%) diagram, the Rock-Eval pyrolysis measurements of all the sediment samples from Lake Orédon also fall within the same area and below the line (IH = 300 mgHC·g−1·TOC) characterizing organic matter of pedologic origin [6,7,14]. The maximum 137Cs content in the sediment is clearly identified within the upper unit between 9.5 and 10 cm core depth (Supplementary Table S3), together with traces of 241Am (Figure 10). These signatures at a core depth of 9.5 cm can be associated with the nuclear weapon tests culminating in 1963 CE in the Northern Hemisphere [6,7,14]. A mean sedimentation rate of 0.18 cm/yr can be estimated for the upper 9.5 cm of core ORE-15.

Three samples of organic macro-remains from core ORE-15 at 18.5, 25, and 45 cm core depth (Figure 10) were dated by AMS radiocarbon at Beta Analytic Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory (Miami, FL, USA), further constraining the core’s chronology (Supplementary Table S4). However, the two samples from the upper unit are not in chronological order, suggesting that the organic material sampled at 18.5 cm core depth (dated to 1677 +/− 17 Cal CE) was reworked from the Lake Orédon drainage basin. A mean sedimentation rate of ca. 0.06 cm/yr can thus be estimated for the upper unit between the main 137Cs peak at 9.5 cm (1963 CE) and the radiocarbon sample at 25 cm (1725 +/− 55 cal CE). This allows dating the transition to the lower unit at 1592 +/− 55 cal CE (Figure 10).

The association of sedimentary facies of the lower unit and the identification of chaotic acoustic facies near the lake floor at the sub-surface of the ORE-15A coring site are the typical signatures of mass-wasting deposits in lakes [19,33,36,41]. The age of 950 +/− 53 cal CE at 45 cm core depth in ORE-15 suggests that a historical mass-wasting event reworked sediments that had initially accumulated at the delta slope during the last millennium.

The 210Pb and 137Cs data from core O-10 indicate flooding of Lake Orédon in 1892 CE at 20 cm core depth [73]. This indicates a mean sedimentation rate of 0.18 cm/yr, similar to that estimated for ORE-14 from 137Cs data. Core O-10 bulk sediment radiocarbon dating at 105 cm core depth (3890 +/− 560 cal BP, [73], Figure 9) allows for a rough estimate of a mean sedimentation rate of 0.02 cm/yr during the Late Holocene and further documents the low sedimentation rates in northern Pyrenean mountain lakes during the Holocene, compared to alpine lakes [6,14].

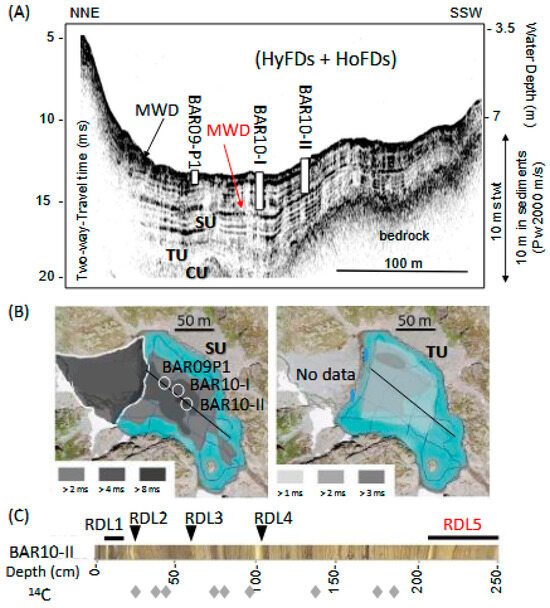

3.4. Lake Blanc Seismic Stratigraphy and Event Stratigraphy

The seismic stratigraphy of proglacial Lake Blanc illustrates three seismic units on most of the Inomar 8 kHz sub-bottom profiles acquired with a dense grid (Figure 11A). A chaotic unit (CU) is identified locally above the acoustic substratum formed by the bedrock outcrops along the southern lake shoreline (gneiss rocks). A transparent unit (TU) is documented above the CU in the deepest part of the glacial basin. The majority of the sedimentary infill of Lake Blanc is associated with a stratified unit (SU), which consists of continuous reflections deposited at a high frequency. The density of seismic profiles in this small lake allows for the production of isopack maps for the TU and SU (Figure 11B). Both seismic units have a divergent geometry: they thicken toward the delta and thin toward the outlet. The TU reaches 3 ms twt in thickness corresponding to ca. 3 m of sediments (using a Pw of 2000 m/s in the sediments as measured on BAR10 sediments [13]), while the SU is slightly more than 8 ms twt (ca. 8 m) thick in the deep central basin near the BAR10 coring site. Two mass-wasting deposits are also identified as transparent to chaotic lens-shaped bodies at the foot of the delta near the lake floor at 15 ms twt (ca. 2 m below the lake floor).

Figure 11.

Synthesis of Lake Blanc event stratigraphy. (A) Seismic stratigraphy illustrating the acoustic signatures of a chaotic unit (CU), a transparent unit (TU), and a stratified unit (SU) together with the location of cores BAR09P1, BAR10-I, and BAR10-II on the seismic line illustrating hyperpycnal flood deposits (HyFDs), homopycnal flood deposits (HoFDs), and mass-wasting deposits (MWDs). (B) Isopack maps of seismic units SU and TU also locating the BAR cores within the lake. (C) BAR10-II sedimentary facies with intercalated rapidly deposited layers (RDLs) and radiocarbon samples (gray diamonds).

The BAR10-I piston core is 280 cm long, and BAR 10-II is no longer than 250 cm, because these sediments were so compacted and dense that further penetration with the UWITEC corer was not possible. Thus, the base of the SU was not reached. The sediment mainly consists of finely laminated silty clay deposits interbedded with drop stones and frequent coarse-grained layers, which are interpreted as large flood-induced turbidites (i.e., hyperpycnal flood events [13]). Up to five rapidly deposited layers (RDLs) are also identified on core BAR10 II (Figure 11C). RDL1 is a mass-wasting deposit (slide) between 6 and 24 cm on the BAR09P1 gravity core. This slide thins laterally toward BAR 10-II and is capped by a thin turbidite layer ending with a light-colored clay cap on top of both piston cores used to build the composite sequence, as shown in [13]. This graded bed is interpreted as a slide-induced turbidite. 137Cs sediment content from BAR09P1 was only detected within RDL1 and above it, but not below it, suggesting that this slide resulted from the destabilization of recent sediments (i.e., post-1950 CE) accumulated on the subaquatic delta slopes [13]. RDL2, RDL3, and RDL4 are similarly slide-inducted turbidites ending with light-colored clay caps (Figure 11C). RDL5 is found near the base of BAR10-II (at 206 cm core depth) and consists of a 44 cm thick mass-wasting deposit made of tilted to folded lamina and massif deposits, which also end in a slide-induced turbidite and a clay cap. This event is visible on sub-bottom profiles (MWD2 in Figure 11A). It originates from the delta slopes and thins toward the BAR10-II coring site. The chronology of these cores, provided by radiocarbon samples, allows for establishing an age–depth model of the composite sedimentary sequence, excluding RDLs, as detailed in [13]. The previous study focused on the upper 190 cm of BAR10 II (i.e., the upper 85 cm of the composite sedimentary record) covering the last 1400 years (718 +/− 55 cal CE). This age–depth model detailed in [13] allows for correlating RDL1, RDL2, RDL3, and RDL4 with historical events (see the Discussion section). Unfortunately, the age of RDL5 is not clearly established, and bulk sediment radiocarbon dating is not suitable for this lake [13]. Extrapolating a mean sedimentation rate of 0.01 cm/yr, calculated between the two lowest radiocarbon dates (718 +/− 55 cal CE and 1020 +/− 120 cal CE) from the composite sedimentary record, suggests that it was possibly triggered 1600 years earlier (i.e., 880 cal BC or ca. 2800 cal BP). Thus, this important mass-wasting deposit in Lake Blanc was probably not contemporaneous with the 563 CE Tauredunum catastrophic rockfall event documented near the Rhone delta in Lake Geneva. However, RDL5 might be contemporaneous with the initiation of the nearby Argentière rock failure (Figure 4) estimated between 1.3 and 2.5 thousand years ago by 10Be dating [79].

3.5. Lake Bourget Event Stratigraphy

The detailed seismic stratigraphy of Lakes Bourget and Annecy (Figure 1 and Figure 4) resulting from the last climatic cycle has been previously established based on sparker data (Supplementary Table S1) and on the CLIMASILAC drill core calibration [56,57,58]. Together with lower-resolution air gun data from a previous study [55], these acoustic data highlight a deep and asymmetric glacial erosion surface (Supplementary Figure S2) and the development of a similar seismic stratigraphy in over-deepened sub-basins along axial profiles [76]. These basin fills are dominated by Late Glacial lacustrine deposits developing thick stratified units with divergent geometries near tributary deltas and migrating channel–levee systems, building deep lacustrine deltaic fans. High-resolution seismic data from Lake Bourget (Figure 12) clearly image the upper part of these Late Glacial lacustrine deposits, together with a catastrophic basin collapse event that occurred ca. 9400 cal BP. This event formed multiple mass-wasting deposits capped by a thick seiche deposit [15,33,56,75]. These basin collapse deposits, up to 20 m thick [75], are visible on vintage air gun data (Supplementary Figure S2). They are covered by a Holocene lacustrine drape up to 15 m thick. This Holocene drape is dominated by authigenic production in the lake water, but high-amplitude reflections in front of tributary deltas were also identified [10] and sampled by either gravity or piston corers.

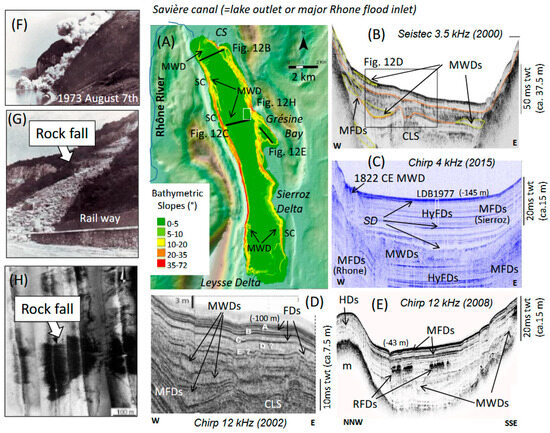

Figure 12.

Geomorphology and stratigraphy of Lake Bourget shore lines and sedimentary infill. (A) Topographic maps and bathymetry slope maps of Lake Bourget locating selected seismic profiles shown in (B–E) (black lines) and side scan sonar mosaic illustrating the 1973 rockfall deposit on the lake floor (white rectangle). (F) Picture of the ongoing Casquette rock fall event. (G) Picture of the Casquette Rock fall deposit on land. (H). Side scan sonar mosaic of the lake floor illustrating the Casquette rock fall deposit underwater. CS: Chautagne swamp. SC: slide scar. MWD: mass-wasting deposit. CLS: channel–levee system. HyFDs: hyperpycnal flood deposits. MFDs: mesopycnal flood deposits. SD: seiche deposit. FDs: flood deposits. HDs: hemipelagic deposits. m: moraine.

Figure 12 illustrates a wide range of morphologies and deposits in Lake Bourget resulting from both gravity and flooding hazards. High-amplitude and continuous reflections are intercalated within Holocene hemipelagic deposits in front of the lake outlet (exposed to Rhone River flooding events, Figure 12D) and in front of the Leysse and Sierroz deltas. Such reflections are also identified locally within the protected and shallower Grésine Bay (Figure 12E). These reflections are interpreted here as resulting from the influence of the Coriolis force, which deviates suspended sediment plumes produced by powerful mesopycnal Sierroz River flood events northward (toward the right). In the deep central basin, distal Sierroz River mesopycnal flood deposits similarly develop high-amplitude reflections only along the eastern slopes of the basin ([10], Figure 12C). Along the central axis of the deep basin, there are several well-developed high-amplitude reflections below and above the basin collapse deposits. These reflections are either Sierroz or Rhone rivers’ distal hyperpycnal flood deposits following the lake floor topography during the Late Glacial and the Holocene ([10] Figure 12C). Toward the northern basin, below the Holocene drape and successive small mass-wasting deposits, a channel–levee system can be clearly identified on seismic profiles. This system is associated with the development of powerful Late Glacial to early Holocene proximal Rhone River hyperpycnal flood events [31,33,34,56,75,89]. The two levees are dissymmetric (Figure 12B,D). The right-hand (western) side levee is higher and results from the exposure of the fine-grained turbulent hyperpycnal sediment plumes to the Coriolis force. Next to this channel–levee system, a well-stratified depocenter is identified along the northwestern slopes of Lake Bourget (Figure 12B,D) and interpreted as frequent Late Glacial to Early Holocene Rhone River mesopycnal flood deposits. This depocenter resulted from the influence of the Coriolis force on frequent fine-grained suspended sediment plumes trapped above the lake thermocline and deflected to the right [31]. The alimentation of these two contrasting depocenters of proximal Rhone River flood deposits ended once the Rhone River bypassed Lake Bourget ca. 10,000 years ago [101]. A similar Rhone River mesopycnal flood depocenter was identified in the deep central basin along the western slopes and below the basin collapse deposits (Figure 12C). These Late Glacial to Early Holocene distal Rhone River mesopycnal flood deposits were strongly impacted and remolded by the basin collapse event at 9400 cal BP [15,34,54,56,75].

Multiple slide scars and mass-wasting deposits (MWDs) along steep slopes (Figure 12A) are identified on multibeam bathymetry, side scan sonar [54], and sub-bottom profiles in proximal (Figure 12B,D) and distal deltaic deposits (Figure 12C). Late Glacial MWDs are also identified in Grésine Bay (Figure 12E). Recent and Holocene subaquatic MWDs produce typical chaotic morphologies on the lake floor and chaotic to transparent lens-shaped bodies on seismic profiles. In the deep central basin (Figure 12C), up to three seiche deposits are also highlighted on 4 kHz chirp profiles. They produce a typical transparent acoustic facies and a high-amplitude basal reflector, both of which are found in the deepest part of the lake basin. The 1822 CE seiche deposit is up to 23 cm thick at the LDB1977 coring site (Supplementary Figure S3) and laterally covers one of the earthquake-induced slides (Figure 12C) along the western slope of the deep central basin [15,41,52]. The 9400 cal BP seiche deposit is up to 2 km wide, covering the basin collapse deposits. It is up to 2 ms twt thick (ca. 150 cm), and this rapidly deposited layer is characterized by a very flat upper limit. Another seiche deposit, up to 1 ms twt thick (ca. 75 cm), is also identified in Figure 12C just below the base of the LDB1977 piston core (see below). Locally, listric faults in the Holocene drape are associated with creeping features in both proximal deltaic environments (Figure 12B,D) and within the protected Grésine Bay (Figure 12E). These features suggest recurrent (during the Late Glacial and the Holocene), recent, incipient, and ongoing gravity reworking processes along Lake Bourget slopes with an inclination > 10° (Figure 12A). Small rockfall deposits are also locally identified within the Grésine Bay sedimentary infill (Figure 12E) and at the foot of the eastern slope of Lake Bourget, just north of this bay (Figure 12H), below the accidental rockfall event triggered on 7 August 1973 (La Casquette event, Figure 12F,G). On that day, the use of too much explosive material to purge a hanging cliff above the railway triggered a rockfall avalanche of ca. 20,000 m3 that ended in the lake [75]. An unusual, light-colored turbidite layer (up to 6 cm thick) is identified near the surface of the gravity and piston cores taken in 1977 and in five gravity cores from the deep central basin collected in 1997, 2009, and 2010 [75,92], as shown in Supplementary Figure S3. This layer of variable thickness in the central basin has a sandy base and fins upward into a carbonate-rich mud layer [75]. This rock avalanche deposit contrasts sharply with the biochemical varves occurring in the lake since its eutrophication in 1942 CE and constitutes a new chrono-stratigraphic marker for Lake Bourget.

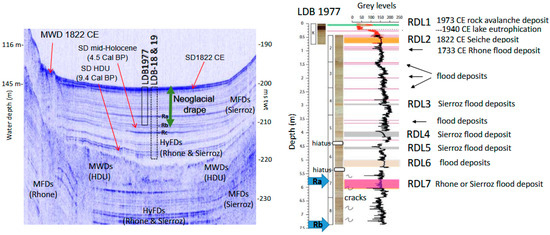

Figure 13 illustrates the correlation between the 4 kHz chirp acoustic facies and the sedimentary facies identified in the LDB1977 composite sequence, combining digitalized optical pictures and measurements in grayscale. The chronology of LDB1977 is provided in the upper meter of the sequence by the identification of the 1973 CE rock avalanche deposit (RDL1), the onset of biochemical varves in 1942 CE, the 1822 CE earthquake-induced seiche deposit (RDL2), and the 1733 CE historical Rhone River flood deposit. At 3 m below the 1977 lake floor, there is a succession of two usual red-colored deposits (1 cm and 5 cm thick) that matches a level where chirp data illustrate a relatively high-amplitude reflection within the Holocene drape. This reflection occurs in the axis of the central basin (i.e., hyperpycnal flood deposits) and extends along the eastern slopes of the basin (i.e., Sierroz River mesopycnal flood deposits). The two layers have a similar red color, suggesting that they are composed of clastic sediments originating from the same source area in the drainage basin of the Sierroz River. The first layer is thinner, with gradual basal and upper boundaries, while the second, thicker layer has a sharp base with a gradual upper boundary. These are, in Lake Bourget, the typical sedimentary signatures of distal mesopycnal and hyperpycnal flood deposits [10,31,75]. These two flood deposits may thus constitute a new chronostratigraphic marker (RDL3) for Lake Bourget. Similarly, both RDL4 (a 20 cm thick sharp-based reddish deposit with a gradual upper boundary occurring between 400 and 420 cm) and RDL5 (identified between 450 and 460 cm core depth) in LDB1977 are likely Sierroz River hyperpycnal flood deposits (Figure 13). RDL6, a similar but grayish hyperpycnal flood deposit, is identified between 500 and 523 cm in LDB1997. Finally, RDL7, occurring between 565 and 600 cm in LDB1977, is the thickest grayish hyperpycnal flood deposit identified. This layer corresponds to a high-amplitude reflection (Ra) in the basin axis and could thus result from either the Rhone or the Sierroz River.

Figure 13.

Lake Bourget deep basin seismic to core LDB 1977 correlation and event stratigraphy. Interpreted seismic profile (left) and LDB1977 sedimentary facies (right) of background sedimentation and intercalated rapidly deposited layers (RDLs). This seismic profile illustrates hyperpycnal flood deposits (HyFDs) and mesopycnal flood deposits (MFDs) originating from the Rhone and Sierroz tributaries. These deposits are exposed to mass-wasting deposits (MWDs), leading to the development of seiche deposits (SDs). The prominent reflections Ra, Rb, and Rc are useful for interpreting the nature and source area of the flood and seiche deposits. They are also used to localize the projected coring sites of cores LDB1977 and LDB 18 and 19 discussed in the text. White rectangles in LDB 1977 are illustrating sedimentary hiatus due to coring disturbances. Blue arrows are locating the corresponding depth of reflection Ra and Rb on core LD 1977. Color bars are illustrating the thicknesses of RDLs in LDB 1977 corresponding to rock avalanche deposit, seiche deposit or flood deposit. When possible the name of the tributary producing the flood deposit is indicated according to the color of the deposit on core LDB 1977 and on the corresponding geometry of high-amplitude reflections resulting from flood deposits on seismic profile, as discussed in the text.

A succession of similar reddish RDLs (up to five layers) is also documented between 470 and 550 cm core depth in the recently published piston core LDB18&19 sequence [102]. This 13.5 m long sequence was sampled with a UWITEC device in 2018 and 2019, in the deep central basin (Figure 13) close to LDB1977 (Supplementary Figure S3). These successive reddish flood layers occurred between 2800 and 2000 cal BP, according to the radiocarbon age-depth model developed for core LDB18&19 [102]. The occurrence of two hiatuses (probably due to coring disturbances) is detected in the core images around 450 cm and 550 cm core depth in LDB1977, limiting the correlations between the LDB1977 and LDB18 & 19 sequences. Further analysis is needed to confirm the nature, age, and sediment sources of RDL 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

The Holocene lacustrine drape in Lake Bourget can be subdivided into two acoustic facies. The first is a transparent basal facies matching the Early Holocene lacustrine marls in piston cores LDB01 and LDB04 [31,34]. The second is an upper stratified facies characterized by multiple high-amplitude and continuous reflections resulting from more frequent tributary flood events since the onset of the Neoglacial period (ca. 4.5 to 5 thousand years ago (kyrs), [7]). In the northern basin of Lake Bourget, for example, seismic reflections labeled a, b, and c in Figure 12D correspond to periods of enhanced large Rhone River flood deposits matching “LIA” like cold periods associated with Mont Blanc Glacier fluctuations [31,32,33,34]. Thus, the base of the so-called “Neoglacial drape” is another chronostratigraphic marker horizon on seismic profiles [16]. Below the projected base of LDB1977 on the chirp profile, a seiche deposit is clearly identified (Figure 13). This event occurred at the base of the Neoglacial drape in Lake Bourget and can be correlated with at least two mass-wasting deposits. A thin slump deposit was sampled in LDB04 (in the northern part of the basin) and dated between 4500 and 4600 cal BP [33]. A larger transparent lens-shaped body has not been sampled, but it lies just below the Neoglacial drape at the eastern edge of the eastern central basin [15]. This seiche deposit probably corresponds to one of the RDLs documented in core LDB18&19 between 810 and 850 cm core depth and dated to ca. 4.5 kyrs. The three main seiche deposits in Lake Bourget (1822 CE, 4.5 kyrs and 9.4 kyrs) are thus contemporaneous with multiple coeval mass-wasting deposits remolding either Rhone or Sierroz River flood deposit depocenters along the central basin slopes.

3.6. Lake Geneva Seismic Stratigraphy and Event Stratigraphy

Seismic profiling in the deep basin of Lake Geneva illustrates the asymmetric morphology of the last glacial erosion surface, the variability of its sedimentary infill, and some geological structures of the bedrock (Supplementary Figure S2). Quaternary sediment infill of up to 750 m is documented below the Rhone River and its delta in Lake Geneva near the Sub-Alpine frontal thrust fault (SAF in Figure 4) [28]. Below 300 m water depth, up to ca. 200 m of Late Glacial sediments are imaged at the foot of the southern (French) slopes on profile L2 from 1969, above the complex topography of the Molasse bedrock. However, at the foot of the northern (Swiss) slopes, sparker data reveal only 30 ms twt (ca. 30 m) of postglacial sedimentary infill above the glacial erosion surface below 200 m water depth (Supplementary Figure S4). In this area south of the city of Lausanne, a thrust fault in the bedrock is clearly imaged by sparker data [75] and further illustrates the structural control of the Sub-Alpine Molasse frontal thrust fault (SAMF in Figure 4) on Quaternary glaciation erosion patterns.

The isopack map of lacustrine deposits in the deep basin of Lake Geneva was created by [94] based on a dense grid of multichannel air gun profiles (Figure 7A). It further documents thickness up to 200 ms twt (ca. 150 m) in the central area of profile L2 from [93], and less than 30 ms twt (ca. 15 m) along most of the slopes and in the northern and eastern parts of the basin. According to this map, the bedrock outcrops offshore from the cities of Morges, Rolle, and Yvoire. Lacustrine deposits essentially thicken toward the two main tributary deltas. They are more than 300 ms twt thick (ca. 225 m) and up to 550 ms twt thick (ca. 412 m) in the south western basin where the Rhone delta developed multiple and migrating channel–levee systems feeding distal fan lobes in addition to a large prodelta [96]. Lacustrine deposits offshore of the steep Dranse prodelta are above 100 ms twt (ca.75 m) in the southern part of the basin. Sparker data collected in the central basin are in agreement with this isopack map. These higher-resolution single-channel profiles from 1996 and 1998 illustrate the specific geometry of the central basin fill of Lake Geneva (Supplementary Figure S5). Five main seismic units are here identified above the acoustic substratum (bedrock): glacial deposits (chaotic Unit 1), glacio-lacustrine deposits (chaotic to transparent Unit 2), and lacustrine deposits (stratified Units 3, 4, and 5). Unit 4 is only identified on the valley axis, while Units 3 and 5 are present in most of the central basin, leading to divergent and continuous high-amplitude reflections that thicken toward the Dranse delta. Two main depocenters up to 75 ms twt thick (ca. 56 m) are identified with contrasting geometries: the first depocenter is characterized by migrating channel–levee systems in the deep basin axis in Units 3, 4, and 5, and two channels are also identified on the multibeam bathymetry in front of the Dranse River inlet (Figure 14). The second depocenter is identified along the southeastern slopes of the basin (north of the French towns of Publier and Evian). This depocenter is characterized by localized creeping and the development of listric faults affecting both Units 3 and 5 (Supplementary Figure S5, Figure 14B).

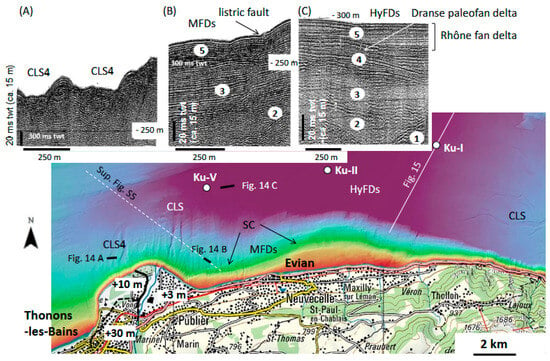

Figure 14.

Dranse delta multibeam bathymetry (from Swiss topo) and selected sparker sections illustrating Lake Geneva seismic stratigraphy (after [77]) and acoustic facies examples of channel–levee systems (CLSs) in the Dranse and the Rhone deltas, Dranse River mesopycnal flood deposits (MFDs), and hyperpycnal flood deposits (HyFDs) developing the Rhone and the Dranse fan deltas. (A) Seismic profile illustrating a paleol Channel Levee System. (B) Seismic profile illustrating acoustic facies of seismic units 2, 3 and 5 discussed in the text. (C) Seismic profile illustrating acoustic facies of seismic units 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 discussed in the text. The Dranse delta is exposed to a gravity hazard, as shown by slide scars (SC) and listric faults within MFDs. The location of the sparker profile shown in Supplementary Figure S5 (white dotted line), the chirp profiles shown in Figure 15 (white line), and the Ku-I, Ku-II, and Ku-V coring sites (white circles) from [96] are also indicated. The location of the Late Glacial +30 m (black dotted line) and +10 m (black line) to Holocene +3 m terraces are discussed in the text.

Two channel–levee systems are visible along the northern slopes of the Dranse delta in bathymetric data and sparker data (Figure 14A). However, these systems are no longer connected to any tributaries from the Dranse Delta and are likely inactive today (paleochannels). They were likely active during the formation of Unit 4 on the basin axis (see the Discussion section). Downstream from the active channels facing the Dranse River inlets, distal fan lobes are also identified in Units 4 and 5 (Figure 14 C). While Unit 4 fan lobes thin eastward, Unit 5 fan lobes thicken eastward. This suggests that Unit 4 was only linked to the Dranse delta sediment supply, while Unit 5 accumulated both Dranse and Rhone River distal flood deposits (i.e., interfingering fan lobes). This interpretation is strongly supported by the identification of Dranse River flood turbidites since 563 CE in core Ku-V and a combination of both Dranse and Rhone River flood turbidites in core Ku-II, as well as only Rhone River flood turbidites in core Ku-I [96].

Slide scars are also identified in the bathymetric data (around 200 m water depth) offshore from the city of Evian (Figure 14). In addition, late Holocene mass-wasting deposits at the foot of the southern slopes, originating from this part of the basin, were documented in the 3.5 kHz pinger data [103]. These mass-wasting deposits originating from the Dranse River mesopycnal flood deposits were coeval with a major mass-wasting event off the coast of Lausanne. This event was dated at the base of core Ku-IV (Figure 7) and possibly explained by an earthquake–mass movement–tsunami event during the Early Bronze Age [103]. The base of this catastrophic Bronze Age event is identified in the pinger data at 460 ms twt in the deep central basin of Lake Geneva.

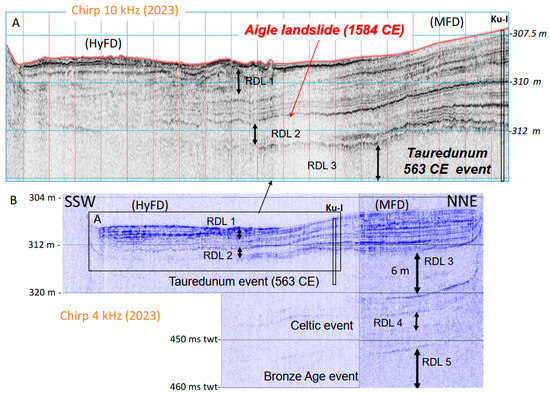

As shown in Figure 15, the Knudsen 4 kHz chirp data penetrated down to 460 ms twt in this part of the lake and imaged up to five RDLs, including the Bronze Age event (RDL5) and the 563 CE Tauredunum event (RDL3), which were discovered, sampled, and dated in [48,82,96,103]. These RDLs are characterized by a transparent acoustic facies, and RDL1, 2 and 3 have an irregular upper limit as clearly imaged by the EXAIL compact Echoes 10,000 chirp data (Figure 15A). These are the typical signatures of a debrite (mudclast conglomerate) catastrophic deposit, according to [48,104]. The Tauredunum event (RDL3) is ca. 6 m thick in this part of the lake, as shown by the 4 kHz chirp data (Figure 15A). As mentioned in [48,82,96,103], the 563 CE debrite is also characterized locally around 435 ms twt on Knudsen chirp data by a low-amplitude and discontinuous reflection matching the transition from the basal conglomerate to the massif upper sedimentary facies, as identified on published 4 kHz data and in cores Ku-I, Ku-II, and Ku-IV (Figure 7). Between the Bronze Age event (RDL5) and the Tauredunum event (RDL3), a similar, thinner, transparent layer (RDL4) was identified at around 445 and 447 ms twt (Figure 15B). This event was possibly sampled at core Ku-IV between the tsunamigenic Tauredunum event and the Bronze Age deposits at 7 to 7.4 m core depth [103]. This thinner event layer is dated to around 2300 cal BP during the Iron Age, a period when different fragmented Celtic tribes inhabited the Western Alps. Thus, this Celtic event (RDL4) likely resulted from the destabilization of deltaic deposits and the deposition of a debrite in the deep central basin. Above the Tauredunum event, two thinner, transparent to chaotic lens-shaped bodies are identified in both the 4 kHz and 10 kHz chirp data in the central basin (Figure 15). RDL2 develops transparent facies (up to 1 m thick) in the southern central part of the basin. It is laterally associated with a high-amplitude and continuous reflection (around 250–300 cm below the lake floor) that was sampled by core Ku-I (Figure 15A). This seismic horizon matches horizon r5 documented by [96], and is correlated with a coarse-grained and graded event layer (turbidite t4) identified in cores Ku-I, Ku-II, Ku-IV, and Ku-V. This event deposit highlights both variable sedimentary facies and thicknesses in these cores and has been dated by radiocarbon to between 1220 and 1420 CE (530 and 730 cal BP; 1400 +/− 100 CE, [96]). However, paleomagnetic secular variations from core Ku-IV, just below this turbidite originating from the Rhone delta, suggest that it occurred shortly after 1540 +/− 70 CE [97]. RDL 1 is a small, chaotic, lens-shaped body that is locally identified between 0.5 and 1 m below the lake floor (Figure 15) and was never sampled by coring.

Figure 15.

Lake Geneva central basin seismic profiles and event stratigraphy based on high-resolution Chirp data collected in 2023 across the Rhone fan delta. (A) Echoes 10,000 compact profile. (B) Knudsen 4 kHz Pinger profile. These two complementary profiles were obtained at identical locations and calibrated using data from the piston core Ku-I, as illustrated in Figure 14. Up to five rapidly deposited layers (RDLs) are identified and correlated with former sediment cores and 3.5 kHz data in the area, according to [80,94,102]. Contrasting acoustic facies characterize Rhone River hyperpycnal flood deposits (HyFDs) and mesopycnal flood deposits (MFDs). The correlation of the upper part of the Bronze Age event (RDL5) and the Tauredunum event (RDL3) allows us to better understand the impact of the Aigle earthquake in 1584 CE (RDL2) and to discuss the triggering of a poorly documented Celtic event (RDL4), as discussed in the text.

Figure 15 illustrates two distinct Rhone River flood deposit depocenters in the 10 km wide, deep and flat central basin of Lake Geneva. In the (deepest) southern part of the basin, several high-amplitude and continuous reflections develop lenses that are locally disturbed in RDL1. This geometry is typical of lacustrine fan delta lobes [56,57,75]. The acoustic signal is quickly absorbed ca. 4 m below the lake floor in both the 10 and 4 kHz chirp data, suggesting that these deltaic deposits are essentially composed of relatively coarse-grained sands. From the Rhone River inlet and its prodelta, a channel–levee system is clearly visible on the lake floor in both the 4 kHz chirp and multibeam bathymetric data down to this part of the deep central basin (Figure 14). Laterally and toward the NNE sector of the deep basin, sediments develop high-amplitude and high-frequency continuous reflections illustrating a draping and slightly divergent geometry (thickening toward the NNE). This acoustic facies was sampled by core Ku-I and interpreted as distal Rhone River flood deposits with a few coarser and thicker turbidites (labeled t2 and t4 by [96].

3.7. Lake Constance

In Lake Constance, it has been clearly documented by [99] that the Rhine River delta sediments limit seismic signal penetration near the lake’s inlet (proximal Rhine delta, Figure 5). The authors also illustrated how the Rhine delta developed a meandering channel–levee system along the basin axis that disappears in the deep, flat, and narrow (ca. 1.5 km wide) distal basin. There, fine-grained sediments develop a laminated acoustic facies with continuous horizontal and high-frequency reflections on 3.5 kHz data. This Rhine River channel–levee system is also clearly visible in Lake Constance multibeam bathymetry [85,100]. As shown in Figure 5 and Figure 16, digital 3.5 kHz pinger lines 1 and 2, published in [85,87], were acquired across the central basin and calibrated by long piston coring (HIBO-19 and B0-91-08).

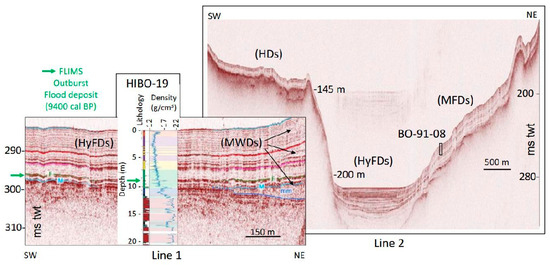

Figure 16.

Distal Rhine delta acoustic facies (3.5 kHz) calibrated by piston core data (B0-91-08 and HIBO-19), illustrating specific depocenters in the deep basin of Lake Constance for mesopycnal flood deposits (MFDs) and hyperpycnal flood deposits (HyFDs), contrasting with hemipelagic sediment deposits (HDs) (modified after [84,85,87]). A few mass-wasting deposits (MWDs) are visible at the foot of the northern slope of Lake Constance. The Flims outburst flood catastrophic deposits (green arrow) produce a specific reflector (F) colored in green. The lower MWD is laterally associated with a turbidite deposit sampled in core HIBO-19 (producing a peak in sediment density) and visible on seismic profile as a specific reflector (M) colored in blue. On core HIBO-19 several contrasting sedimentary facies are illustrated by pink, purple and blue boxes as discussed in the text.

These data illustrate how the Flims outburst flood deposit developed on Line 1, a continuous high-amplitude reflection ca. 9.5 m below the lake floor in the deep and flat central basin. This horizon contrasts with the Early Holocene sediments, which have a transparent acoustic facies, and the Mid to Late Holocene deposits with lower-amplitude continuous and high-frequency reflections sampled by core HIBO-19. Below 11 m core depth, coarser and denser Late Glacial sediments prevent the penetration of the acoustic signal. Locally, three generations of Holocene mass-wasting deposits originating from the NE slopes of the basin produce small lens-shaped bodies with chaotic to transparent acoustic facies thinning toward the basin axis (ca. 10 m; 5 m and 2 m below the lake floor). A sandy turbidite sampled at around a 10 m core depth in HIBO-19 is dated to around 11 kyrs [85] and is associated with a prominent high-amplitude reflection (reflector M in Figure 16) that laterally matches the southwestern edge of the older mass-wasting deposit.

Line 2 illustrates how the deep and flat sedimentary infill of the central basin produces a specific acoustic facies and a depocenter contrasting with the geometry of the basin slope deposits. Toward the SW, a lacustrine drape ca. 10 ms twt (7.5 m) thick with a transparent acoustic facies is visible above the acoustic substratum, developing an irregular subaquatic plateau at around 140 m water depth (Figure 16). The acoustic substratum becomes much steeper toward the basin axis and outcrops along the basin slopes facing the deep and flat central basin. Along the NE basin slope, the acoustic substratum is characterized by gentle and irregular morphology. It is draped by a thick sediment depocenter up to 20 ms twt (ca. 15 m), identified between 90 and 200 m water depths. This depocenter exhibits low-amplitude continuous reflections. These sediments were sampled by piston corer at B0-91-08 and interpreted as distal Rhine River flood deposits [84].

4. Discussion

4.1. Architecture and Chronology of the Perialpine Lakes Deltaic Depocenters

Large glacial lakes formed at the piedmont of both the Northern Pyrenees and the Western and the Northern Alps (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5) following the Last Glacial Maximum [23,28,55,56,57,59,60,63,75,76,84,85]. During the Late Glacial period, climate changes favored glacier melting and their retreat upstream from most large European glacial valleys. A large sediment supply from numerous braided fluvio-glacial streams caused large volumes of clastic sediments to accumulate in European piedmont and perialpine lakes. Large subaquatic deltaic depocenters formed in these lakes during this period through the accumulation of hyperpycnal flood deposits in their deep glacial basins (Figure 1 and Figure 17) [56,57,75].

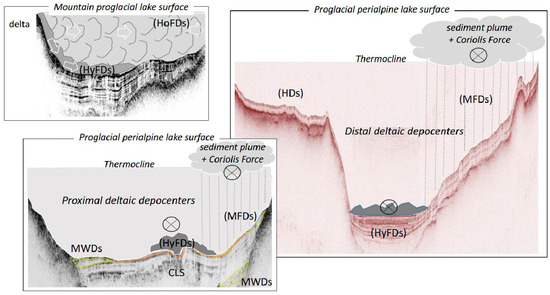

Figure 17.

General conceptual model of tributary flood processes shaping proximal to distal deltaic lacustrine sediment depocenters in mountain and perialpine proglacial lakes. Proximal deltaic deposits in mountain lakes result from homopycnal flood deposits (HoFDs) and hyperpycnal flood deposits (HyFDs) and are exposed to mass-wasting deposits (MWDs) triggered by earthquakes or catastrophic snow avalanches. Both proximal and distal perialpine deltaic deposits resulting from hyperpycnal or mesopycnal flood events (mesopycnal flood deposits, MFDs) can generate tsunamigenic MWDs, which are possibly triggered by earthquakes. The circles with a cross are illustrating flood currents heading toward the bottom of the picture. Catastrophic rockfalls, either near a perialpine inlet or higher up in the drainage basin across the glacial valley streams, can also trigger tsunamigenic MWDs in perialpine lakes or catastrophic outburst flood deposits related to the rupture of a landslide dam and the drainage of the impounded lake temporarily formed upstream of the rock avalanche deposits.