1. Introduction

In recent years, changes in climatic conditions and increasing anthropogenic pressure have contributed significantly to the initiation and intensification of landslide processes [

1,

2]. Accordingly, the rapid, accurate, and efficient assessment of landslide activity remains a critical component of the identification and prevention of geological hazards. The delineation of landslide boundaries and the identification of main morphological elements using traditional field-based methods—particularly under complex conditions in which the area is either anthropogenically altered and/or covered by vegetation—is often costly and, more importantly, time-consuming. For this reason, the use of remote sensing technologies, which enable the rapid and efficient acquisition of high-accuracy digital terrain data within a short time frame, is increasing in contemporary research. One of the most rapidly developing examples of such technology is the use of LiDAR (light detection and ranging) sensors mounted on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) [

3,

4,

5].

LiDAR-based remote sensing technology enables the acquisition of highly accurate information on the micro-topographic features of terrain—even in areas that are densely forested or heavily modified by anthropogenic activity. The data obtained through LiDAR allow for the generation of high-resolution digital elevation models (HRDEMs), which significantly simplify spatial data analysis and facilitate the identification of landslide processes [

6,

7,

8].

Recent research has increasingly emphasized the potential of UAV- and LiDAR-based techniques for landslide mapping and morphology characterization. Pawluszek [

6] explored the potential of using high-resolution digital elevation models (HRDEMs) derived from ALS (airborne laser scanning) LiDAR data for the identification of landslide morphological features. Pawluszek’s report describes a computational method based on HRDEM, the terrain attributes derived from it, and the results from principal component analysis (PCA). The study demonstrated that the terrain attributes derived from HRDEM, when integrated through PCA, significantly enhance the detection of landslide morphological indicators and improve detailed visualization of the surface. Van Den Eeckhaut et al. [

9,

10] further confirmed the effectiveness of LiDAR-derived datasets for identifying old and forested landslides, including the use of object-oriented approaches for automated detection. Similarly, Görüm [

11] demonstrated the capability of airborne LiDAR to recognize and map landslides in densely forested environments, highlighting the importance of vegetation-penetrating laser scanning for detecting subtle geomorphic features. In addition to case-specific studies, broader reviews have emphasized the role of DEM-derived terrain parameters in landslide research. Saleem [

12] summarized how commonly used derivatives such as slope, aspect, curvature, TPI, TRI, and TWI contribute to landslide susceptibility mapping and hazard assessment.

More recently, UAV-based LiDAR surveys have opened new possibilities for capturing high-density point clouds in localized study areas. Han [

13] developed a multi-feature fusion approach using UAV-LiDAR DEMs for landslide trace recognition, demonstrating significant improvements in mapping accuracy. A recent review by Kovanič et al. [

14] provides a comprehensive overview of UAV applications in terrain analysis, environmental monitoring, and natural hazard mapping, confirming their increasing relevance in landslide research. Their study emphasizes the ability of UAVs to acquire high-resolution data in geographically complex and/or difficult-to-access areas, as well as the importance of multi-sensor platforms, which significantly enhance the accuracy and efficiency of spatial analysis. Sun [

15] provided a comprehensive review of UAV applications in landslide investigation and monitoring, confirming the rapid progress of UAV technologies in both hazard detection and risk management. In addition, Zhang [

16] proposed a topographic profile-based method for extracting landslide morphology from UAV-derived DEMs, while Kim and Hong [

17] evaluated UAV-LiDAR performance in terrain morphology analysis, showing its advantages over traditional methods in complex environments. Mercuri [

3] further illustrated the value of UAV photogrammetry and LiDAR integration for first-failure landslide detection and rapid risk assessment. Sestras [

18] demonstrated the advantages of integrating UAV photogrammetry with LiDAR. Their study showed that photogrammetry provides highly detailed surface information, while LiDAR enables accurate representation of the bare-earth terrain, even when it is covered by vegetation. By combining these complementary strengths, a fusion approach improved terrain deformation monitoring and enhanced surveying efficiency.

The objective of this study was to identify the main morphological elements of a landslide in the northwestern part of Surami, an area characterized by extensive anthropogenic impact, based on data obtained from a LiDAR sensor mounted on an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Another goal of this study was to validate the accuracy of the LiDAR-derived data through field verification using GNSS-based measurements. This allowed for an evaluation of the effectiveness of the UAV-LiDAR approach and its applicability for the rapid and accurate identification of landslide processes in complex environments. A DJI Matrice 300 RTK drone equipped with a DJI Zenmuse L1 LiDAR camera was used for data acquisition (DJI, Shenzhen, China). Through processing and analyzing the collected digital data, the landslide boundary was precisely delineated, and its main morphological elements were identified. The accuracy of the results was verified during field surveys using a high-precision GNSS mobile station.

This study demonstrates that UAV-LiDAR can be effectively applied in a mixed environment characterized by forested land and anthropogenic impact, in which vegetation cover and human activity often make landslide mapping difficult. The high-resolution DEM and field validation demonstrate that this approach is reliable for identifying landslide boundaries and key morphological features. The findings are not only valuable for a scientific understanding of landslide processes but also for practical risk management in areas where slope failure may affect settlements and infrastructure.

2. Study Area

The study area (

Figure 1) is located in the northwestern part of Surami (Georgia), on the right slope of the Bijnisistskali River valley. According to the 2024 Bulletin of the Geological Department of the National Environmental Agency under the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia [

19], a landslide was identified at this location. The area is characterized by extensive anthropogenic impact, including residential settlement, agricultural land parcels, and various infrastructural facilities. Lying at an elevation of 781–905 m above sea level, the site has a dry, subtropical steppe climate with moderately cold winters and hot summers. The average annual temperature is 9.7 °C, and the total annual precipitation amounts to 644 mm. On average, there are 134 rainy days per year, with the maximum daily precipitation reaching up to 66 mm. The average annual relative humidity is 75% [

20]. The stratigraphy of the area includes Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks—primarily marls and limestones—which are mostly overlain by Quaternary-age soils of varying thickness [

21]. The slope inclination generally ranges between 35° and 50°, although sections with steeper gradients are also present. From a tectonic perspective, the geological structure of the area is defined by the so-called Georgian Belt (Dzirula intermountain crystalline massif), which is situated between the southern slope of the Greater Caucasus and the Adjara–Trialeti fold-and-block system. Due to the tectonic complexity of the region, several parallel fold structures have been identified within the study area—particularly in the vicinity of the Suramula River and the village of Chumateliti. A notable structural feature near the area is the Chumateliti thrustault [

22]. According to the current revised seismic zoning scheme of Georgia, the study area falls within an 8-point seismic activity zone, according to the MSK-64 intensity scale. The dimensionless A-seismic coefficient is 0.21 [

23].

3. Data and Methodology

The study consisted of five main stages (

Figure 2):

Data acquisition and processing;

Data analysis;

Identification of the landslide boundary and key morphological elements;

Field validation of the results;

Comparison of information obtained from field surveys and LiDAR data.

Figure 2.

Methodology flow chart.

Figure 2.

Methodology flow chart.

3.1. Data Acquisition and Processing

The study area was scanned using the LiDAR sensor (DJI Zenmuse L1) mounted on the DJI Matrice 300 RTK unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Scanning was carried out along a pre-defined flight path (

Figure 3) at an average altitude of 70–100 m above the terrain surface, with a field of view of 70° and a pulse repetition rate of 240 kHz. Flights were conducted in the morning hours under moderately sunny and stable weather conditions, which minimized possible atmospheric effects such as wind, haze, or variable humidity. The maximum baseline distance between the UAV and the D-RTK 2 base station did not exceed 1 km, and during acquisition, the system maintained stable connectivity with 40–45 satellites. These conditions, together with the integration of RTK corrections and IMU calibration, ensured high positional accuracy and minimized the risk of errors from sensor drift, GPS/INS inaccuracies, or atmospheric influences. As a result, a high-spatial-resolution point cloud was obtained, comprising approximately 27 million points in total. To ensure data accuracy, control points were collected using a GNSS mobile station (

Table 1).

The acquired point cloud was processed in LiDAR360 and DJI Terra. Ground points were extracted using the progressive triangular irregular network (TIN) densification algorithm, which is widely applied for UAV-LiDAR ground classification [

24]. From the classified ground points, a 1 m resolution bare-earth digital terrain model (DTM) was generated. This DTM was used as the digital elevation model (DEM) for subsequent analyses. This approach followed established workflows in LiDAR-based landslide research.

3.2. Data Analysis

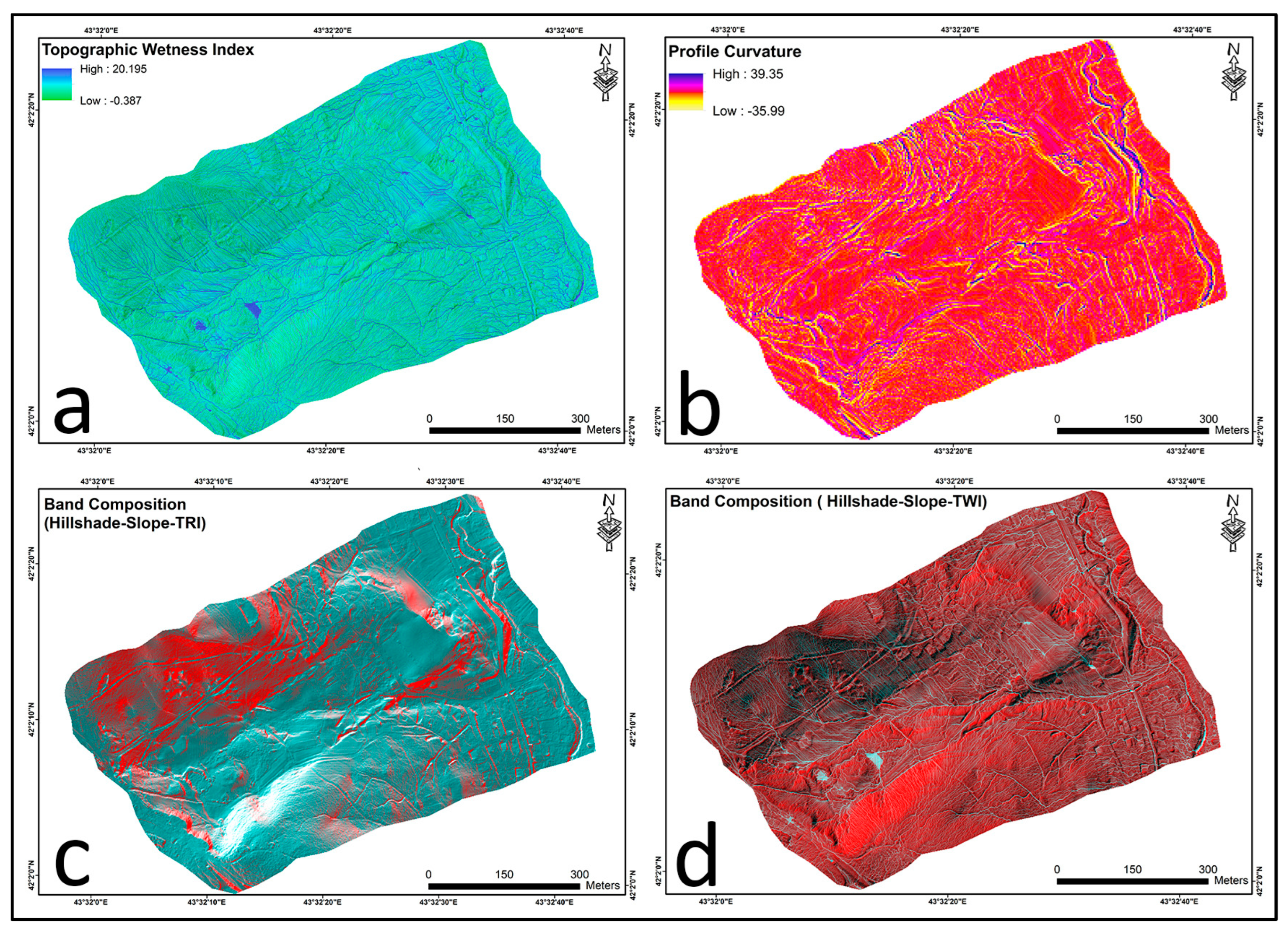

The high-resolution digital elevation model (HRDEM) generated in this study was analyzed using ArcGIS 10.8 software. Based on the DEM, various terrain parameters were calculated and used for the detailed examination of surface characteristics and to enhance visualization quality. Each parameter was selected because it provides useful information on specific geomorphological aspects of the landslide.

Slope maps were derived with the Slope tool to calculate gradient values in degrees. Steep slope zones correspond to scarps, while gentler slopes highlight depositional areas. Aspect was obtained with the Aspect tool, providing information on slope orientation and material displacement trends. Hillshade maps were created with the Hillshade tool (azimuth 315°, altitude 45°) to simulate surface illumination and emphasize small-scale topographic variations.

Surface curvature was calculated using the Curvature tool, yielding both profile curvature (vertical plane) and plan curvature (horizontal plane). These parameters enabled the identification of convex forms, such as the crown and scarps, and concave features related to depositional zones.

The terrain ruggedness index (TRI) and topographic position index (TPI) were calculated using the Focal Statistics tool to quantify surface roughness and distinguish between ridges and depressions.

Hydrological parameters were incorporated to highlight potential instability factors. The topographic wetness index (TWI) was computed by generating flow direction, flow accumulation, and slope layers and then applying the standard formula TWI = ln (Flow Accumulation/tan Slope) in the Raster Calculator. This index identifies zones of water concentration and potential pore-pressure increase. The Stream Power Index (SPI) was used as a proxy for erosive power and runoff intensity.

Contour lines were generated using the Contour tool at 1 m and 5 m intervals to support geomorphological interpretation.

To enhance the visualization of the terrain parameter data and to reduce data redundancy, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied. Several combinations of terrain parameters (e.g., hillshade–slope–TRI; hillshade–TWI–SPI; hillshade–slope–profile curvature–TRI, hillshade–slope–TWI, hillshade–TRI–TPI) were integrated using the Composite Bands tool in ArcGIS 10.8. PCA improved the visibility of the landslide boundary and emphasized subtle morphological elements that are less evident on individual parameter maps.

The choice of terrain derivatives followed established practice in DEM-based landslide studies. Slope, aspect, curvature, hillshade, TRI, TPI, and other indices are among the most widely applied parameters in landslide mapping and hazard assessment, and their combined use provides a robust basis for delineating landslide morphology.

3.3. Identification of Landslide Boundaries and Key Morphological Features

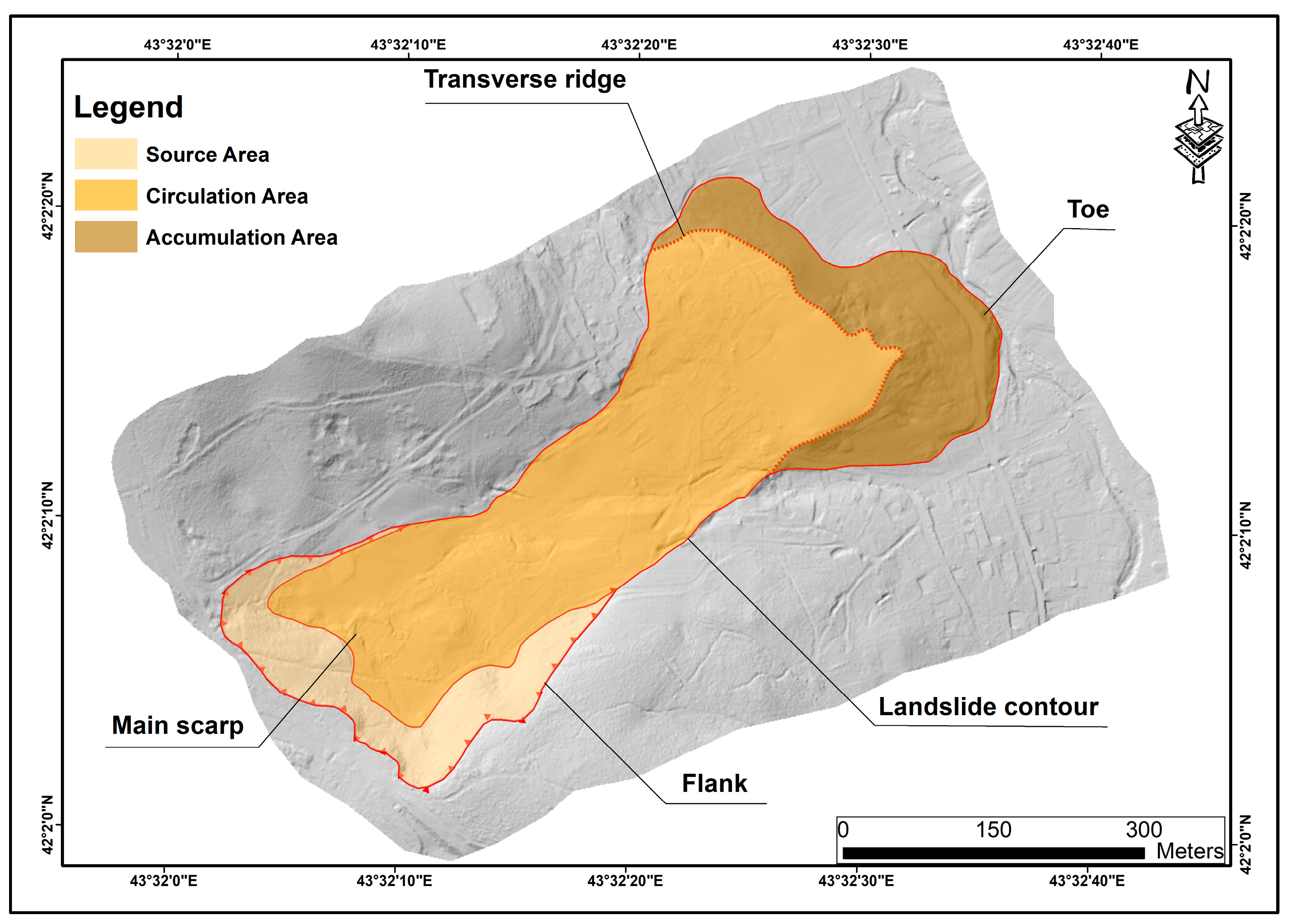

A rotational landslide is characterized by typical surface morphological elements [

14], such as the main scarp, crown, body, toe, transverse ridges, and cracks (

Figure 4). In this study, the boundaries and morphological elements of the landslide were identified based on the analysis of both individual terrain parameters and composite band images. The landslide boundary was delineated through visual interpretation supported by expert knowledge. To calculate the displaced landslide volume, the landslide body was divided into segments, and cross-sections were prepared using contour lines derived from the DTM. The distance between successive cross-sections was determined, the cross-sectional area of the landslide body was calculated for each profile, and the average area between adjacent cross-sections was obtained.

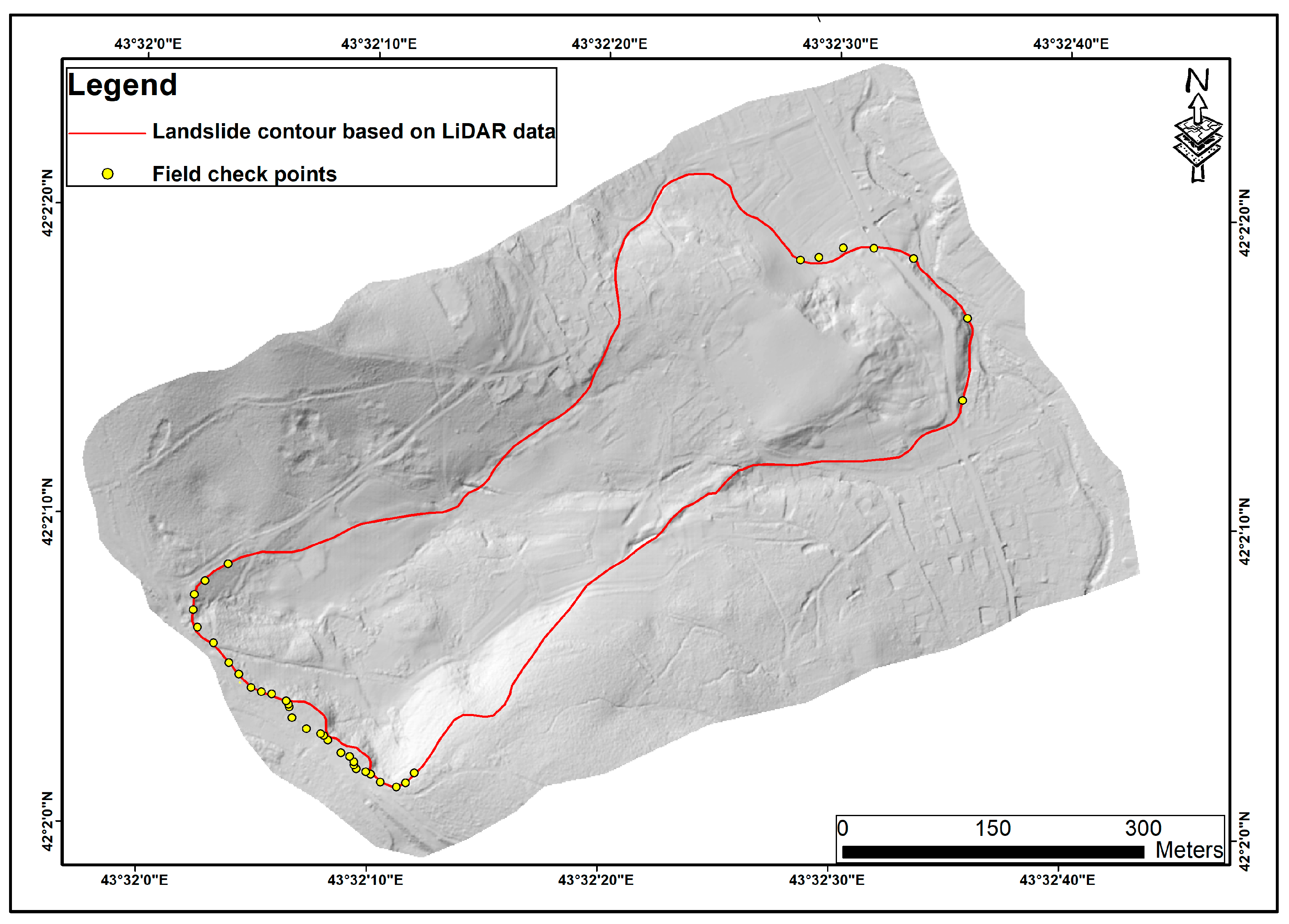

3.4. Field Validation of the Landslide Boundaries and Data Comparison

To assess the accuracy of the landslide boundary delineated from the UAV-LiDAR data, field validation was conducted using traditional methods, which included visual reconnaissance and the collection of control points using a high-precision GNSS RTK mobile station. Given the intense anthropogenic impact in the area, the control points were primarily collected from sections of the landslide at which the boundary was visually well defined in the terrain. The field-verified data were compared with the LiDAR-derived boundary, and deviations were summarized by calculating the mean, median, and percentile errors (P90, P95). This confirmed that the LiDAR-based delineation provided a largely accurate representation of the landslide boundaries, with discrepancies mainly occurring in the crown area, where slope morphology and anthropogenic modifications complicate boundary recognition.

4. Results

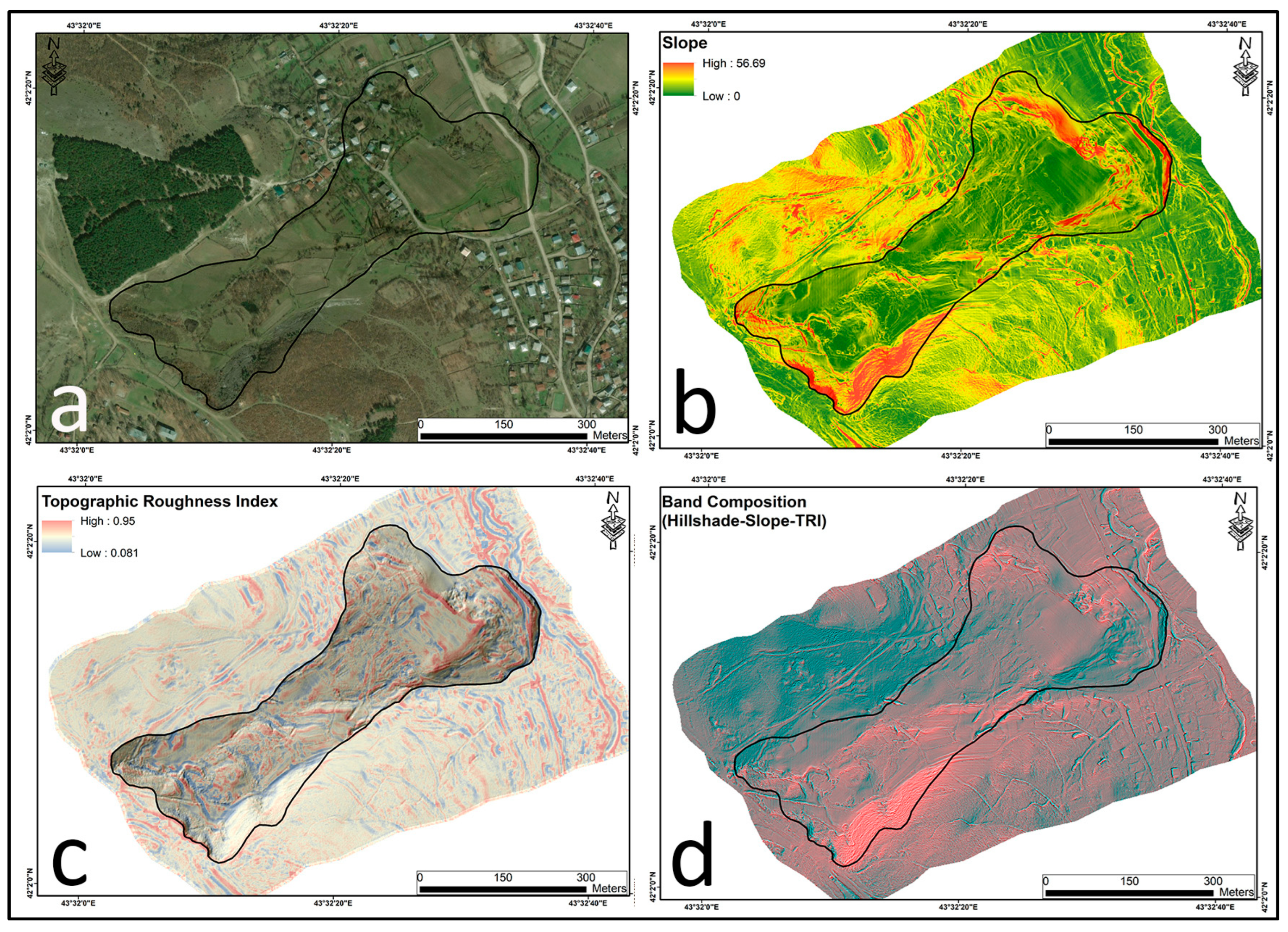

The point cloud data acquired using the LiDAR sensor mounted on the UAV platform enabled a highly accurate reconstruction of the terrain in the study area. The UAV-LiDAR survey produced a dense point cloud of approximately 27 million points, from which a 1 m resolution bare-earth digital terrain model (DTM) was generated, which served as the basis for detailed GIS analysis. Using the DEM, several key terrain parameters were derived and analyzed, including slope, aspect, hillshade, contour lines, plan and profile curvature, the terrain ruggedness index (TRI), and the topographic position index (TPI) (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The slope map provided information on terrain steepness, which facilitated the identification of high-slope zones. Gradients exceeding 35° mostly corresponded to the source area with a maximum slope of 56°. In contrast, gentler slopes characterized the circulation and accumulation areas. The aspect map supplied data on slope orientation, which influences the area’s microclimatic conditions (e.g., soil moisture, vegetation cover) and plays a role in landslide formation. Aspect analysis showed that the slope predominantly faces north–northeast, and the landslide movement follows this aspect direction. These results highlight the importance of slope and aspect.

Hillshade analysis aided in the visual interpretation of landforms by simulating lighting and shadowing. This method contributed to a clearer identification of the landslide boundary and micro-relief features. Curvature parameters provided complementary insights; profile curvature highlighted convex landforms and concave zones. This information supported the assessment of landslide displacement.

Morphometric indices further distinguished the landslide from adjacent terrain. The terrain ruggedness index (TRI) and topographic position index (TPI) enabled evaluation of micro-relief roughness and topographic position, which facilitated the delineation of specific landslide morphological elements.

Hydrological indices provided additional context on potential instability. The TWI revealed potential zones of water accumulation and areas where surface runoff is likely to concentrate. Contour lines provided topographic information, allowing for the delineation of the landslide boundary and the identification of various morphological components.

To improve the interpretation of terrain characteristics and boundary recognition, terrain derivatives were integrated using principal component analysis (PCA). Composite band images such as hillshade–slope–TRI, hillshade–slope–profile curvature–TRI, hillshade–slope–TWI, hillshade–TWI–SPI, and hillshade–TRI–TPI images revealed morphological contrasts more clearly than single-parameter maps. This approach significantly increased the visibility of landslide features and improved the delineation of the landslide boundary and its morphological elements (

Figure 7).

The results of the GIS-based analysis allowed for clear delineation of the landslide boundary and its key morphological features, including the crown, main scarp, transverse ridge, and toe (

Figure 8). These elements were identified through the combined use of slope, curvature, TRI/TPI, and hydrological indices integrated with PCA composites.

To validate the obtained results, field investigations were carried out using traditional methods. During this process, control points were collected along selected sections of the landslide boundary using a high-precision GNSS mobile station.

A comparison between the GNSS checkpoints and the landslide boundary delineated from the LiDAR data showed high positional accuracy. The mean deviation was calculated to be 3.9 m, the median was 0.3 m, and the standard deviation was 5.6 m. The 90th percentile error was 10.3 m, and the 95th percentile error was 15.8 m. The minimum offset was close to zero, and the maximum discrepancy of 21.4 m occurred in the crown area. Detailed analysis revealed that the observed deviation was caused by anthropogenic factors—specifically, the natural terrain configuration had been altered due to the deposition of technogenic fill material. In this case, “technogenic fill material” refers to soil and construction debris deposited at the crown area after the landslide event. This difference underscores one of the limitations of LiDAR technology: its inability to distinguish between natural and artificial (technogenic) ground.

Overall, the results indicate that the landslide boundary based on UAV-LiDAR analysis is largely accurate and adequately reflects the spatial extent and configuration of the landslide body (see

Figure 9).

According to the results, the landslide originated near the crest of the slope, encompassed the entire hillside, and terminated at the foot of the slope in the floodplain of the Bijnisistskali River. The following features were determined based on the data analysis:

Total area of the landslide: 16.6 hectares;

Source area: 2.5 hectares;

Transport (circulation) area: 10.6 hectares;

Accumulation area: 3.5 hectares;

Approximate displaced volume: 1,821,200 m3;

Vertical elevation difference across the terrain: 76 m;

Maximum slope angle: 56°;

Direction of movement: toward the northeast;

Landslide length: 756 m;

Landslide width varies between 160 and 360 m.

The results of this study have direct implications for hazard assessment and risk management. The landslide impacts the natural and constructed environment, causing damage to residential buildings, various structures, agricultural land parcels, and infrastructure, including central and local access roads, along with electrical transmission lines. The crown of the landslide lies only about 10 m upslope from an unpaved road, along which several transmission towers are also located, indicating a potential risk to critical infrastructure. The toe intersects the central road that connects nearby villages, highlighting the threat of transportation disruption. Within the landslide body itself, approximately 20 residential houses are directly affected, while an additional 15 houses are located within 50 m of the landslide margin. These conditions emphasize the significant hazard posed to local infrastructure and communities. Periodical UAV-LiDAR surveys are recommended to monitor slope changes, detect early signs of reactivation, and support timely risk mitigation.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of UAV-LiDAR technology for mapping landslide boundaries and morphological elements in complex environments, including areas modified by human activity. A bare-earth digital terrain model (DTM) derived from LiDAR ground points provided a basis for calculating several morphometric parameters, each offering complementary information about the landslide. By integrating these parameters through principal component analysis (PCA), the interpretation of terrain features was improved, allowing for a more accurate delineation of the landslide boundary and the identification of its key morphological components.

The findings of this study are consistent with earlier works demonstrating the importance of DEM-derived parameters for landslide mapping. Pawluszek [

6] demonstrated that combining DEM derivatives with PCA improves the detection of morphological features, which was also evident in this study, where composite images enhanced the visibility of landslide features. Van Den Eeckhaut et al. [

10] and Görüm [

11] highlighted the value of LiDAR for identifying subtle forms beneath forest cover, and similar patterns were observed in the Surami area. Saleem et al. [

12] further emphasized the usefulness of parameters such as slope, curvature, ruggedness, and hydrological indices, many of which were applied in this study.

The novelty of our research lies in its focus on an environment shaped not only by forest cover but also by intense anthropogenic activity. While most previous UAV-LiDAR studies concentrated on natural or forested slopes, our work shows that the method can also be successfully applied where human activity has altered the terrain, obscured natural forms, and complicated boundary recognition. By demonstrating reliable performance in this mixed but predominantly anthropogenic setting, this study contributes new knowledge to landslide research and expands the applicability of UAV-LiDAR methods beyond the most commonly studied contexts.

Despite the strong performance of the UAV-LiDAR approach, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, this study describes a single case from the Surami area, which restricts the generalization of the findings. Second, UAV-LiDAR data are not free from uncertainty; possible sources of error include GPS/INS drift, IMU misalignment, and atmospheric effects. In this research, such errors were minimized through RTK corrections, careful boresight calibration, and validation with GNSS checkpoints. Nevertheless, the maximum deviation of 21.4 m highlights LiDAR’s inability to differentiate between natural terrain and technogenic fill. These limitations suggest that UAV-LiDAR data should be complemented by traditional field surveys for maximum reliability.

This study demonstrates both scientific and practical value. From a scientific perspective, it shows that UAV-LiDAR methods remain reliable in anthropogenically modified environments, thereby expanding the applicability of LiDAR-based geomorphological analysis. From an engineering perspective, the results provide critical information for hazard assessment, slope stabilization, and infrastructure protection. The close proximity of the crown to an unpaved road and transmission towers, along with the intersection of the toe with a central road, highlights the urgent need for monitoring and mitigation measures. This makes UAV-LiDAR surveys a powerful tool for local authorities and engineers involved in risk management and land-use planning.

Beyond its scientific contribution, this study also demonstrates clear practical relevance. The UAV-LiDAR approach provided detailed information on landslide morphology that would be limited through traditional field surveys. Such high-resolution data are directly applicable in geotechnical practice, supporting hazard evaluation, slope stabilization planning, and the protection of settlements and infrastructure. In the Surami case, the location of the crown near a rural road and transmission towers, together with the toe intersecting a central access road, emphasizes the need for targeted monitoring and mitigation measures. This makes UAV-LiDAR surveys a powerful tool for local authorities and engineers involved in risk management and land-use planning.

6. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of UAV-LiDAR technology for identifying landslide boundaries and key morphological features in Surami, Georgia, where the terrain has been strongly altered by human activity. Unlike many previous investigations that focused mainly on natural or forested slopes, this research examined an environment in which anthropogenic modification plays a dominant role in shaping surface conditions, complicating landslide mapping.

The results confirm that UAV-LiDAR provides reliable and detailed information under such conditions. The 1 m DTM generated from LiDAR ground points enabled the derivation of multiple morphometric parameters, whose integration through PCA improved the visibility of critical features such as the crown, scarp, body, and toe. Field validation with GNSS checkpoints confirmed the accuracy of the delineation, with most errors being small, though larger deviations occurred in the crown area due to the presence of technogenic fill. The landslide was found to cover 16.6 ha in total, extending 756 m downslope with an average width of about 260 m, a vertical elevation difference of 76 m, and an estimated 1,821,200 m3 of material displaced. Movement is directed toward the north–northeast.

From a scientific perspective, this study provides new evidence that UAV-LiDAR methods are effective not only in natural terrains but also in heavily anthropogenically modified settings, where traditional mapping is limited.

From a practical perspective, these findings are directly relevant to hazard management. The landslide poses a direct threat to local infrastructure and communities, as it affects roads, residential areas, and transmission lines within and near its boundaries. These impacts highlight the urgent need for continuous monitoring and risk mitigation. UAV-LiDAR surveys provide timely and accurate information that can support land-use planning and hazard management.

It is important to note that this study was limited to a single slope and that UAV-LiDAR data remain subject to potential sources of error, such as GPS/INS drift or atmospheric effects, although these were minimized through RTK corrections and field validation.

Future research should extend the application of this workflow to other anthropogenically influenced landslide sites and consider integrating machine learning approaches to improve the differentiation of natural and artificial surfaces.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that UAV-LiDAR is a powerful and reliable method for landslide investigation in environments where human activity has significantly modified the terrain. By proving its applicability in such challenging contexts, this research advances both scientific knowledge and practical strategies for protecting communities and infrastructure in landslide-prone regions.