Abstract

The growing global population intensifies food demand, challenging the agricultural sector to increase efficiency. Precision agriculture (PA) addresses this challenge by leveraging advanced technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and sensor networks, to collect and analyze field data. However, accessible tools for storing, managing, and analyzing these data are often limited. This study presents AgDataBox-IoT (ADB-IOT), a novel web application designed to fill this gap by providing a user-friendly platform for optimizing agricultural management. ADB-IOT integrates into the existing AgDataBox ecosystem, extending its capabilities with dedicated IoT functionalities. The application enables farmers to plan IoT networks, visualize and analyze field-collected data through thematic maps and graphs, and monitor and control IoT devices. This integrated approach facilitates informed decision-making, improves control over sustainable soil management, and enhances the overall efficiency of agricultural operations. As a freely accessible tool, ADB-IOT lowers the barrier to adopting precision agriculture technologies.

1. Introduction

Estimates indicate that the world’s population will increase from 8 billion to 9.7 billion by 2050, with 68% residing in urban areas [1]. This demographic shift, characterized by a decline in rural populations, presents a significant challenge for the agricultural sector in meeting future food demands. Technology offers the most promising path forward, with continuous advancements in software and hardware. In agriculture, Industry 4.0 leverages technologies such as precision agriculture (PA), sensor networks, the Internet of Things (IoT), and artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance production systems. PA is notable for its versatility, aiming to achieve (1) economic benefits through cost reduction via precise input control, (2) increased productivity by managing field variability, and (3) environmental benefits through the precise application of fertilizers and pesticides [2], thereby rendering agriculture more sustainable and profitable [3,4,5].

PA can harness IoT through interconnected sensor networks to provide data for intelligent solutions in the agricultural sector. IoT provides valuable tools, including sensor-based equipment and communication networks, to address issues in traditional agriculture, such as irrigation control, pest management [5,6,7], fertilizer and corrective management [8], microclimate monitoring [9,10], and process automation [11,12]. Despite its potential, farmers with limited economic resources often lack access to software for enabling IoT applications [3,13]. Therefore, the development of free, open-source software is crucial to ensure broad access to technologies that facilitate data storage, management, and real-time monitoring. Recent reviews highlight that while high-tech solutions exist, cost and technical complexity remain significant barriers for small-scale adoption [14,15].

The AgDataBox (ADB) project was established to provide free computational tools for PA. It currently includes ADB-Mobile, for mobile devices; ADB-API, for data management; ADB-Map [16], for generating thematic maps; and modules for interpolator selection, fertilizer and limestone recommendation, ADB-AplicNutrient; variable selection and management zone definition; data cleansing, ADB-Cleaning; and satellite image and UAV geoprocessing, ADB-RS. However, a dedicated, configurable IoT environment for sensor network planning, data acquisition, and device control was missing from this suite. This study aims to address this gap by developing and integrating the ADB-IOT module into the ADB platform. The primary objectives were to (1) design and implement a web application for IoT network planning, (2) enable real-time data monitoring and visualization, and (3) provide remote control capabilities for IoT devices within a unified, user-friendly interface.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tools and Technology

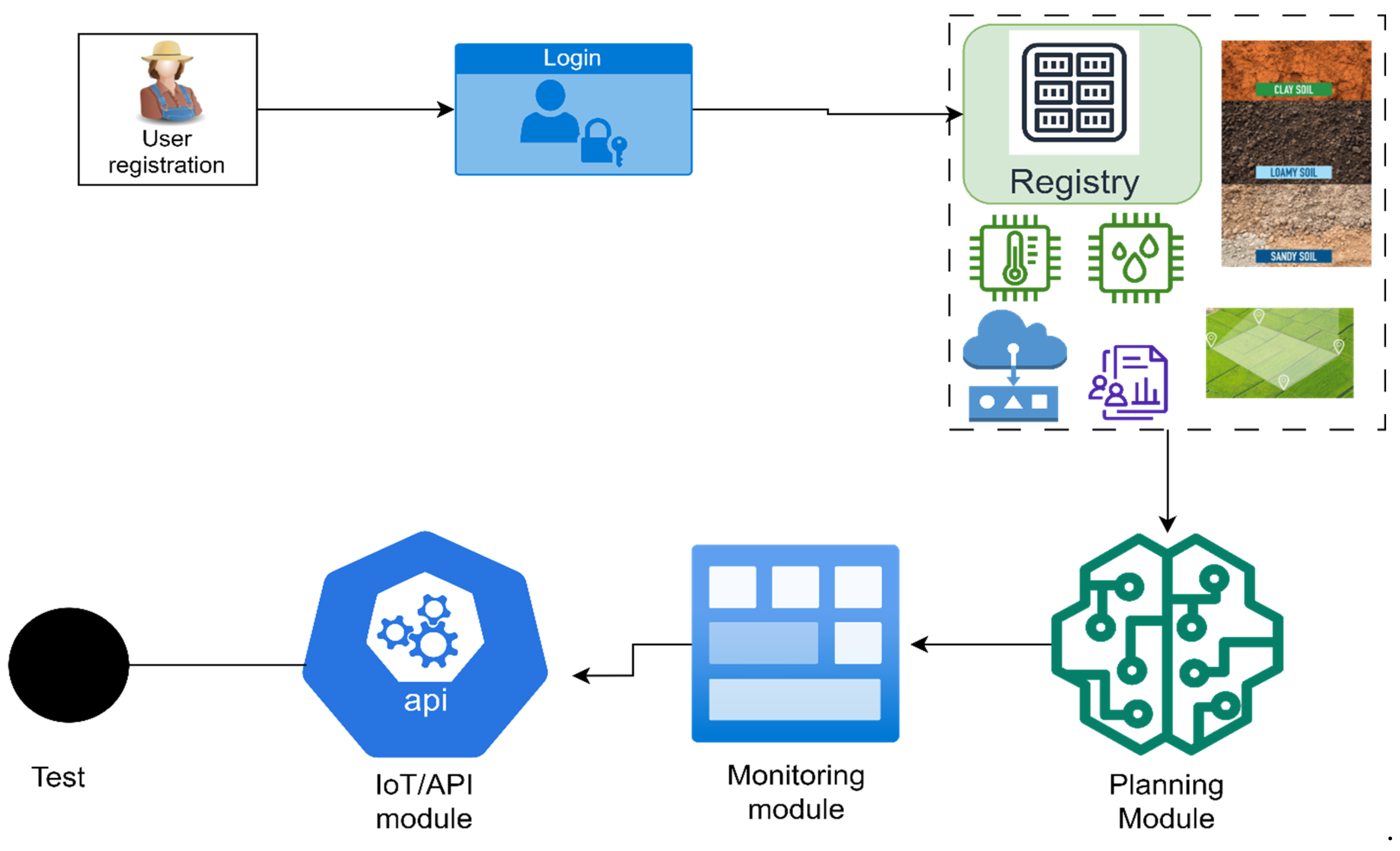

The development of the ADB-IOT web application employed a stack of open-source technologies to ensure cost-effectiveness and facilitate free distribution [17]. The modeling and implementation stages followed the framework depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stages of web application development.

Visual Studio Code 2022 (version 17.14.22) was selected as the source code editor due to its lightweight nature and support for multiple languages [18]. The application’s front-end was structured using HTML [19] and styled with CSS. TypeScript was chosen as the primary programming language for its static typing and object-oriented features, which enhance code maintainability and reduce errors [20]. The Angular framework [21] was utilized to accelerate development through its component-based architecture and integrated tools [22]. System modeling was conducted using UML class and use case diagrams. For geospatial data visualization, the open-source OpenLayers library was integrated, enabling the display and manipulation of interactive maps in web browsers.

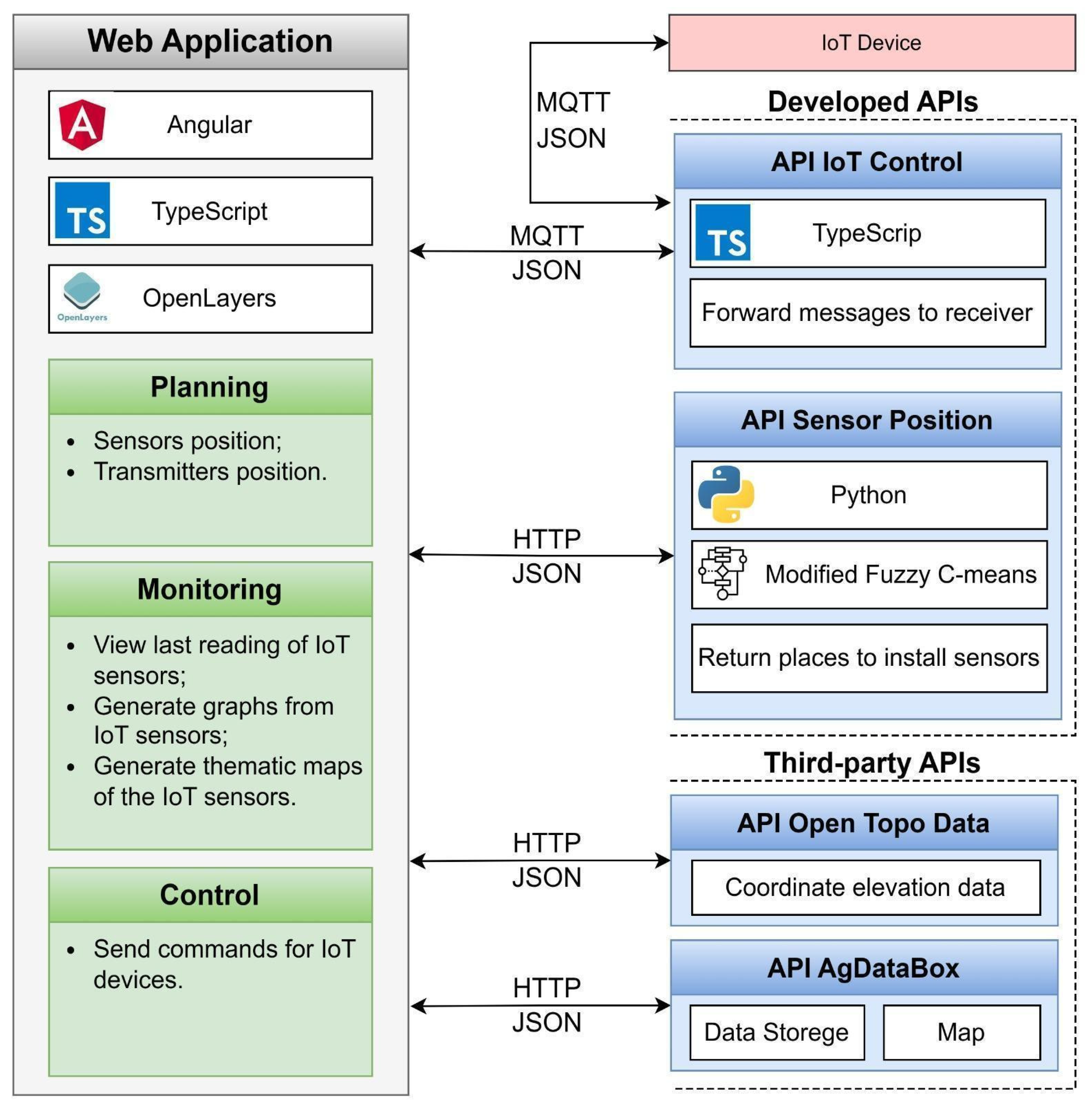

2.2. APIS for Application Development

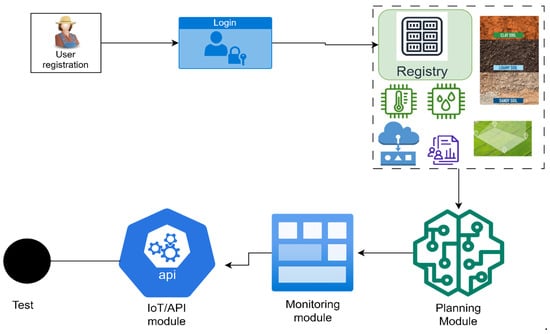

The application’s functionality relies on the integration of four key Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), with their communication structure illustrated in Figure 2. To address the common interoperability challenge among heterogeneous IoT devices [23], the architecture uses standard HTTP and MQTT protocols to ensure seamless data exchange and communication.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the used and developed APIs.

1. ADB-API: This core API provides resources for agricultural data storage and management, handling information related to users, georeferenced data, and IoT devices [24,25]. It also offers functionalities for producing thematic maps via HTTP requests, which are essential for building distributed web information systems [26].

2. Open Topo Data API: This open-source API was used to obtain elevation data for specific geographic coordinates, which is necessary for generating property elevation maps [11].

3. IoT Control API: Developed in TypeScript, this API manages communication between the web application and IoT devices using the MQTT protocol, selected for its lightweight nature and reliability in fragile connections [27]. It incorporates authentication and authorization systems to secure message transmission.

4. API Sensor Position: Developed in Python 3.9, this API implements a modified Fuzzy C-Means algorithm [28] to determine optimal sensor installation locations. The algorithm processes a dataset X = {}, and a feature vector = {} for each k {1,2,… n}, where is the p-dimensional space. In this context, the algorithm seeks to find a set of pseudo-fuzzy partitions corresponding to a family of fuzzy sets of X that best represent the data structure, denoted by P = {}, satisfying = 1 and 0< where k {1,2,… n} and n is the number of elements in X (Equation (1)). Thus, it is characterized by several clusters C. This distance measure defines the maximum allowed distance between points and the centroid (m (1,)) [28]. The process involves calculating a membership matrix and validation indices to identify the best sensor positions. (Equation (2)), Fuzzy Performance Index (FPI, Equation (3)) [29] and Modified Partition Entropy Index (MPE, Equation (4)) [30]. The FPI and MPE values are used to determine the sensor’s installation locations.

where corresponds to the center of the cluster and is the weighted mean of the data in , t = {1, 2 …, n} is the iteration number; is the mth power of its relevance degree to the Fuzzy set ; represents the distance between and ; c is the number of clusters; n is the sample size; and is the element of the Fuzzy matrix.

2.3. Application Modules

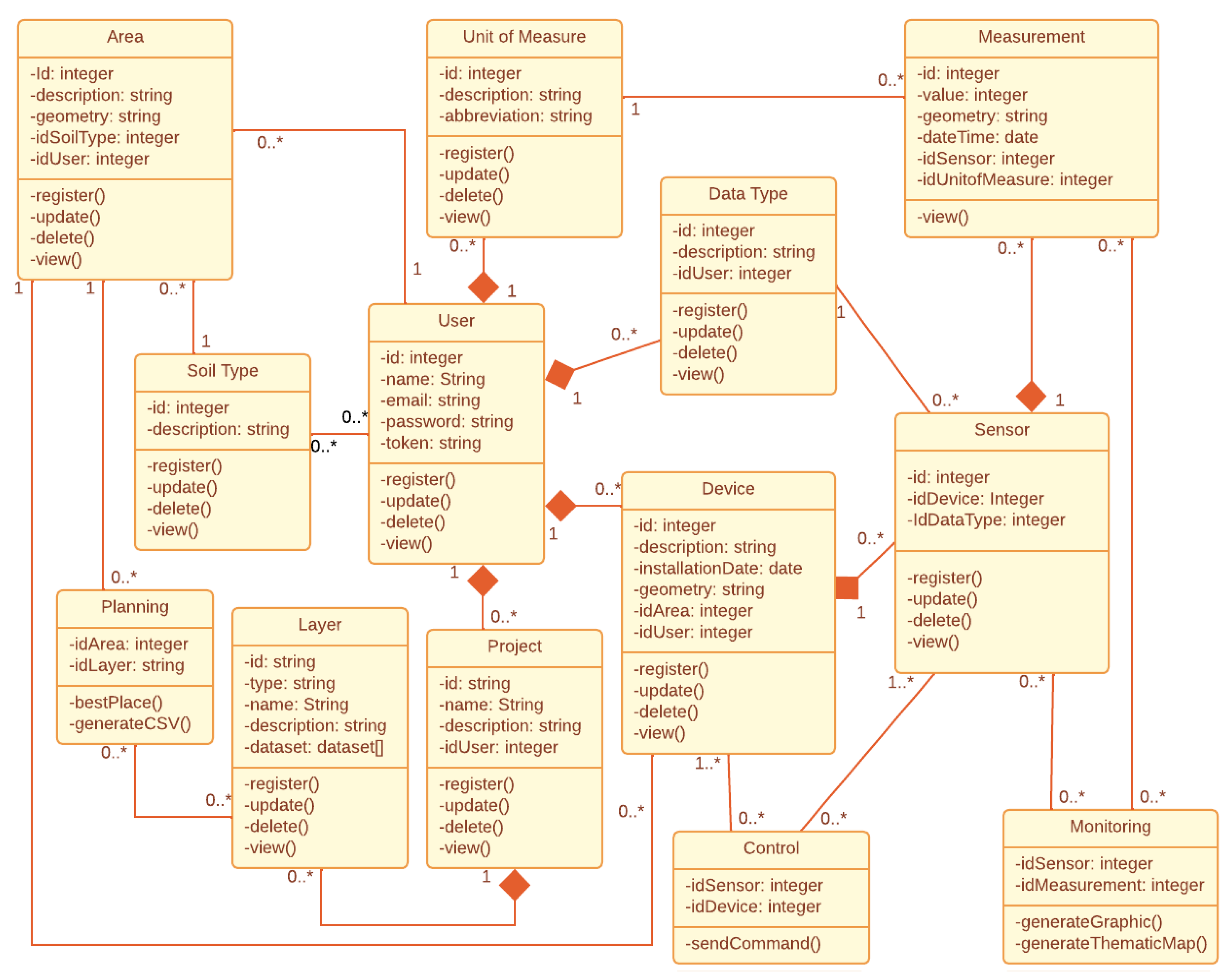

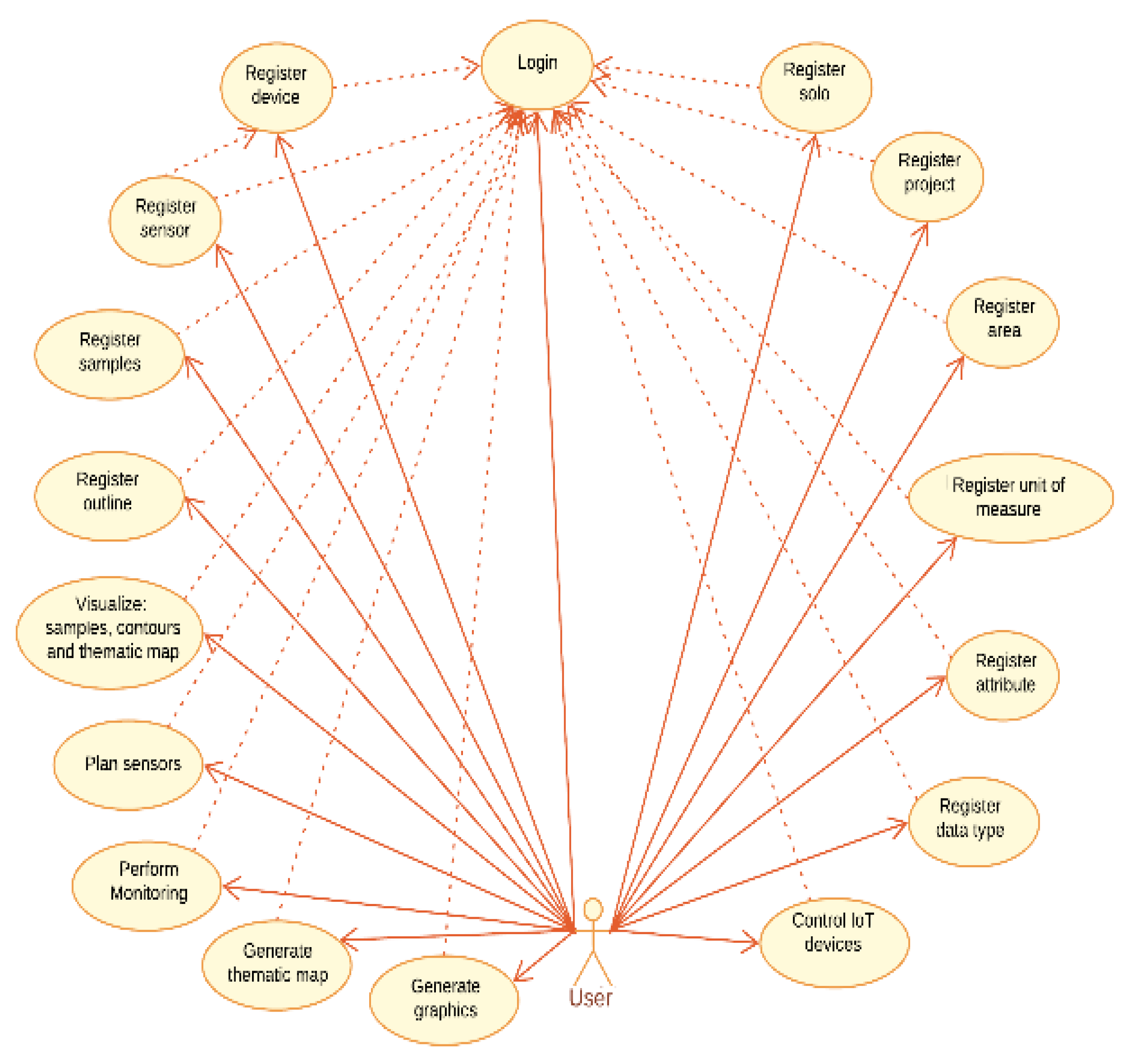

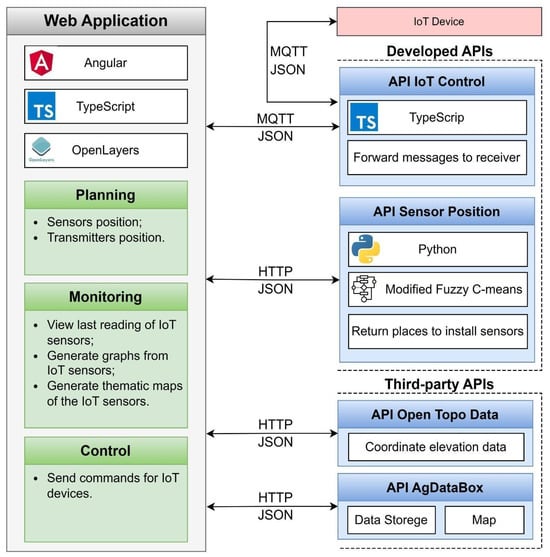

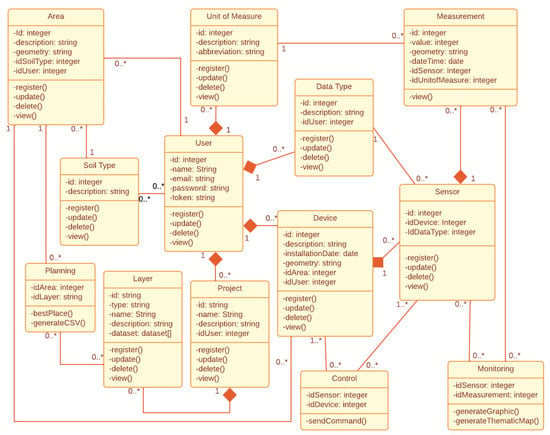

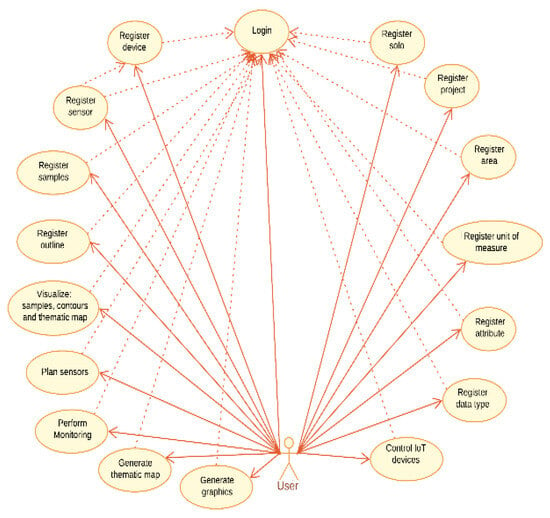

The web application is structured into three modules: Planning, Monitoring, and Control. UML diagrams were created to plan the system’s structure and functionalities. The class diagram (Figure 3) illustrates the application’s structure and the relationships between its entities, with the User class at its center. The use case diagram (Figure 4) illustrates user interactions, including logging in, data entry, and device management.

Figure 3.

Class diagram of the web application. *: relationship many.

Figure 4.

Use a case diagram of the web application.

2.3.1. Planning Module

This module assists users in planning the deployment of sensors and transmission towers. It consists of two phases:

- Sensor Planning: Offers three tools: (1) Manual mode for placing sensors on a map; (2) Point grid for generating a regular grid based on a user-specified distance; and (3) Best installation locations, which uses the Sensor Position API to analyze soil sample data and suggest optimal positions.

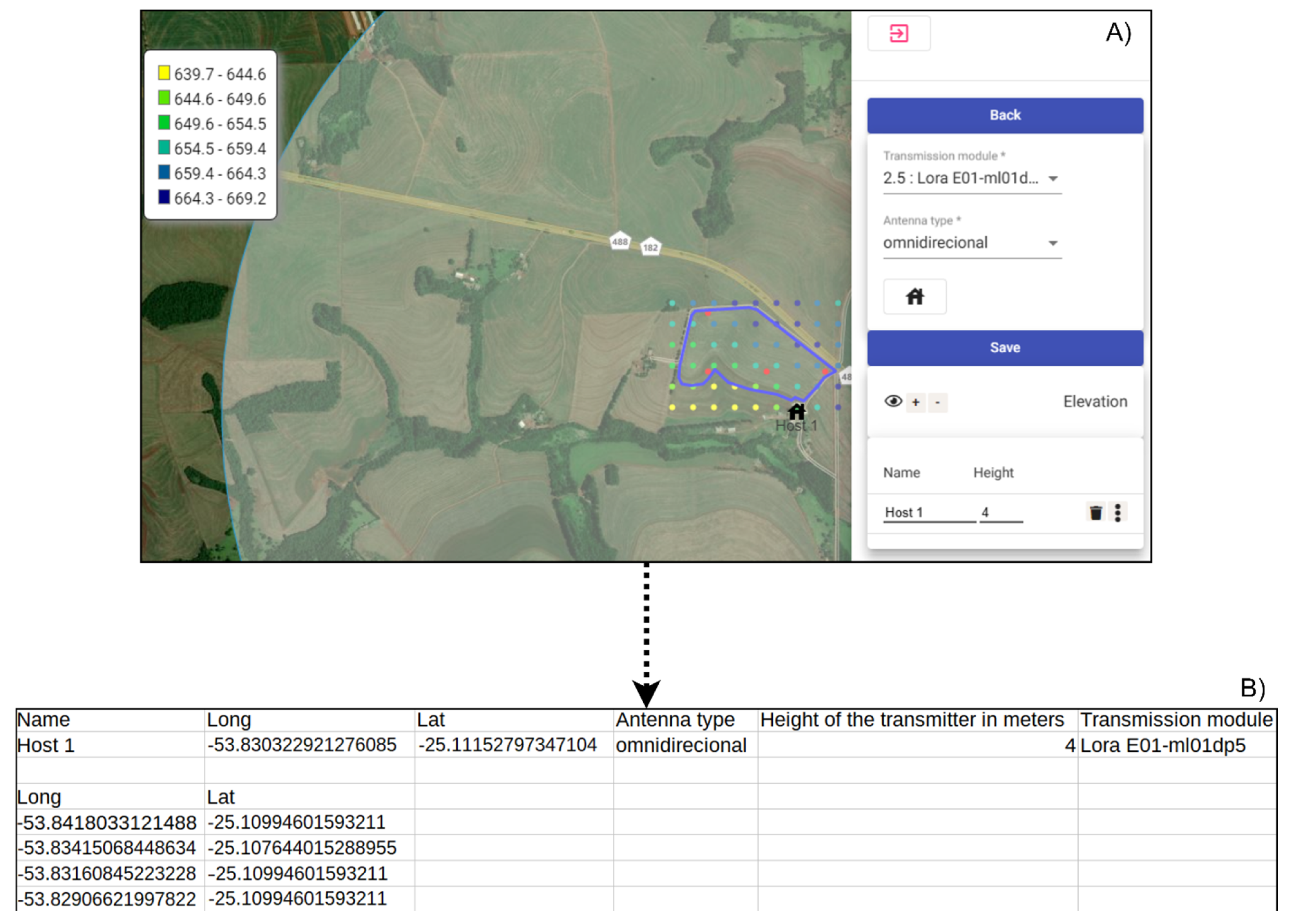

- Signal Transmitter Planning: Displays a thematic elevation map and planned sensor locations. The user selects a transmitter module from a list, and its coverage area is visualized on the map upon placement. A file containing the geographic coordinates of all planned devices is generated for installation.

2.3.2. Monitoring Module

This module presents data collected by sensors, grouped by type. Three monitoring methods are available: (1) real-time display of the latest sensor readings; (2) generation of time-series graphs for a user-specified interval; and (3) generation of thematic maps using interpolation methods (IDW or Ordinary Kriging) available from the ADB-API.

2.3.3. IoT Device Control Module

This module allows the web application to send commands to field devices via the IoT Control API. Commands include turning actuators on/off or changing the data transmission interval of sensors.

2.4. Data Security and Authentication

The integrity and confidentiality of data exchanged between the front end and APIs are ensured through JWT-based authentication, a widely used API security mechanism. Furthermore, data is individualized per user and can be shared with other users of the ADB platform.

2.5. Software Evaluation

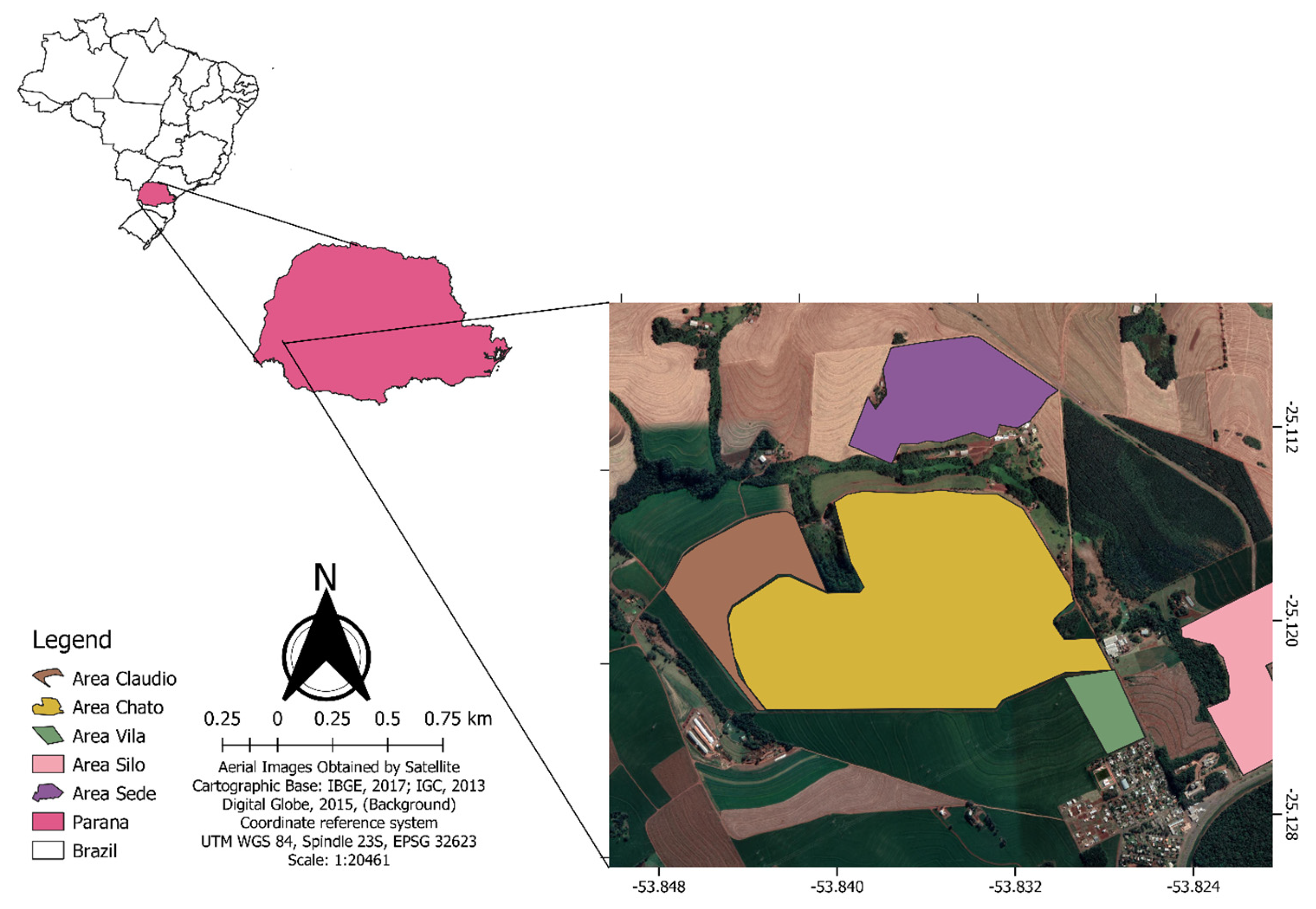

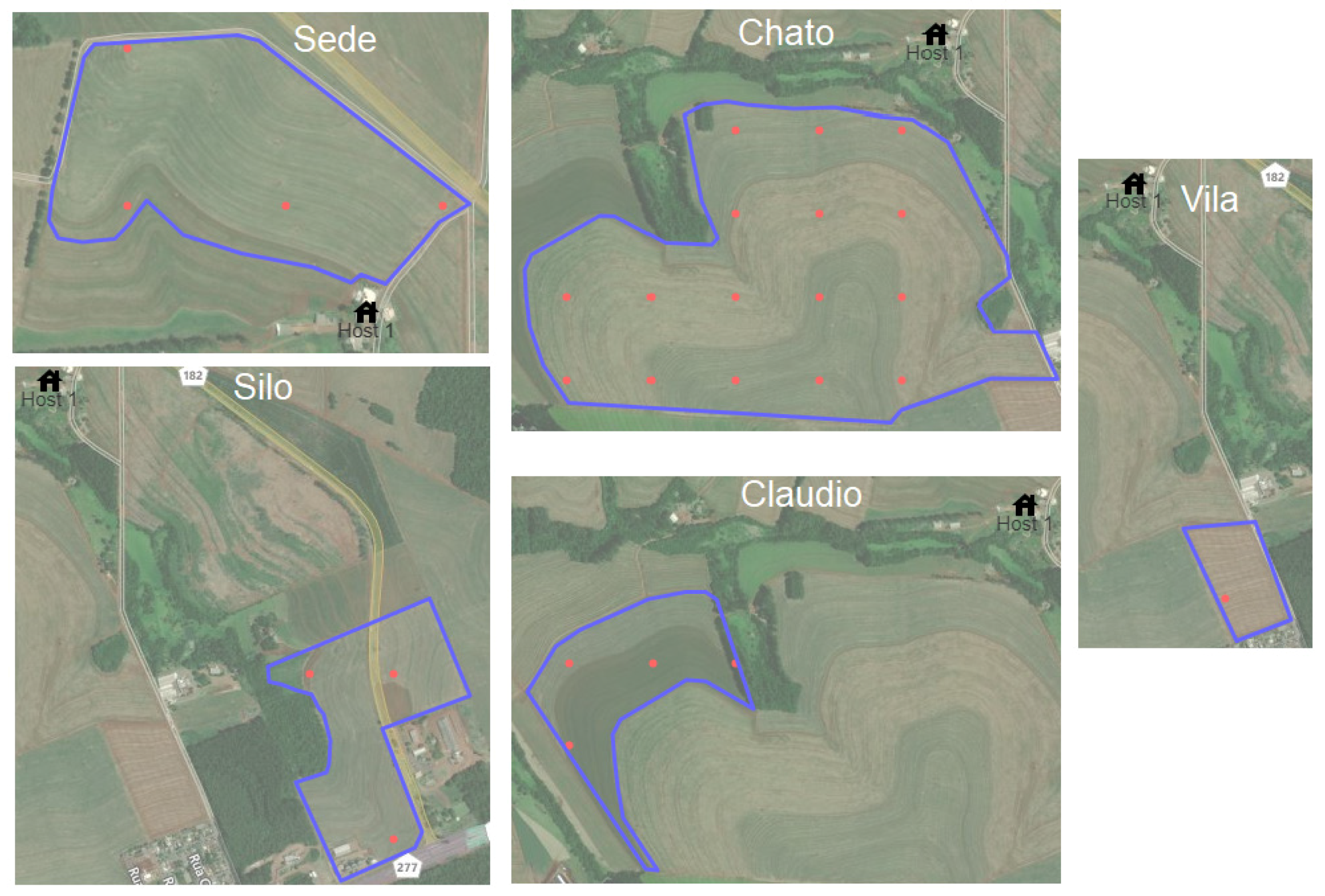

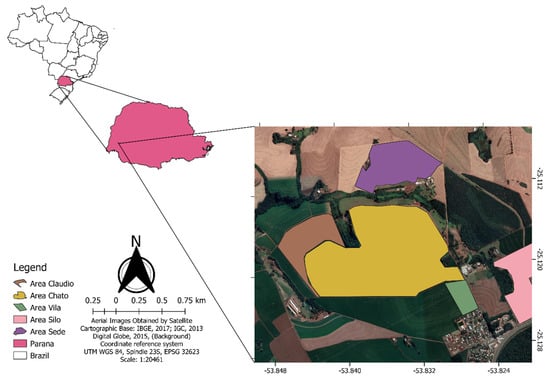

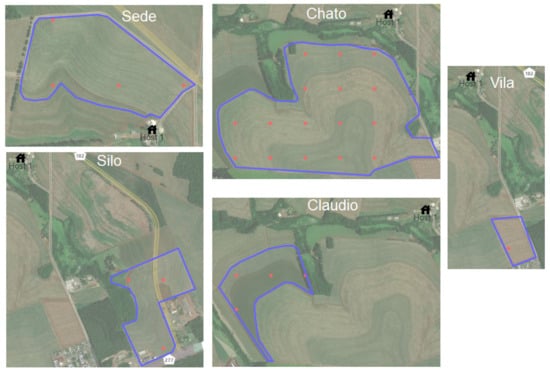

To validate the computational module, an experimental area located in Céu Azul, Paraná, Brazil, at the geographic center, with coordinates (25°06′32″ S and 53°49′55″ W) and an altitude of 460 m, was used. The experimental area consists of five regions (Sede–32.2 ha, Silo–28.9 ha, Chato–121 ha, Vila–7.66 ha, and Claudio–23.8 ha) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Location map of the Courage Farm used for the ADB-IoT assessment.

To verify the control module’s operation, an IoT network was established, comprising a sensor and actuators that collected data from the Kate 3.0 agrometeorological station (Table 1). Commands were sent from the web application to change the sensor’s data transmission interval, and it was verified that the IoT device received the command correctly. (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Technical characterization of stations.

Table 2.

Measured parameters (every minute) and used sensors.

3. Results

3.1. Web Application

The implemented solution is hosted on a server at the Federal Technological University of Paraná—Campus Medianeira and is accessible at http://academicapps.md.utfpr.edu.br/iot/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). Users must have a computer with internet access and a compatible web browser. The application was developed using a component-based Angular architecture (e.g., Figure 6). Integration with the ADB-API is performed through HTTP requests (POST, UPDATE, GET, DELETE). A successful request returns a 200 code, while errors return specific codes as documented in the API (https://adb.md.utfpr.edu.br/api/data/v2/) (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Figure 6.

The component responsible for registering and updating areas.

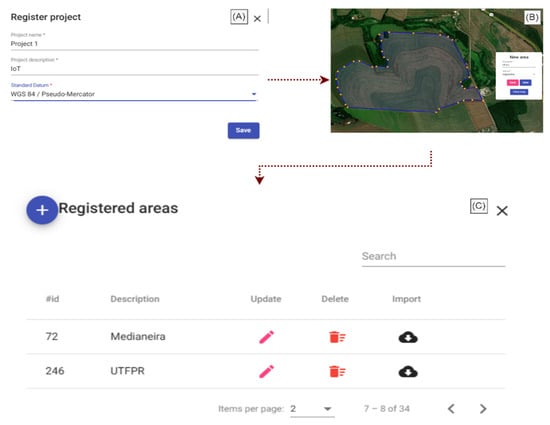

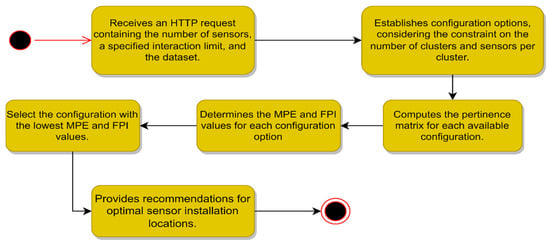

User interaction begins with login and project selection or creation. Within a project, users can register and manage areas, soil samples, and IoT devices (Figure 7). The application requires users to have prior knowledge of registration procedures, as it does not provide predefined lists of soil types or units of measurement. For spatial data, the application automatically converts coordinate DATUMs if necessary, though using a UTM DATUM is recommended for optimal performance.

Figure 7.

The project registration screen (A), the new agricultural area registration screen (B), and the registered areas within the project (C). *—required.

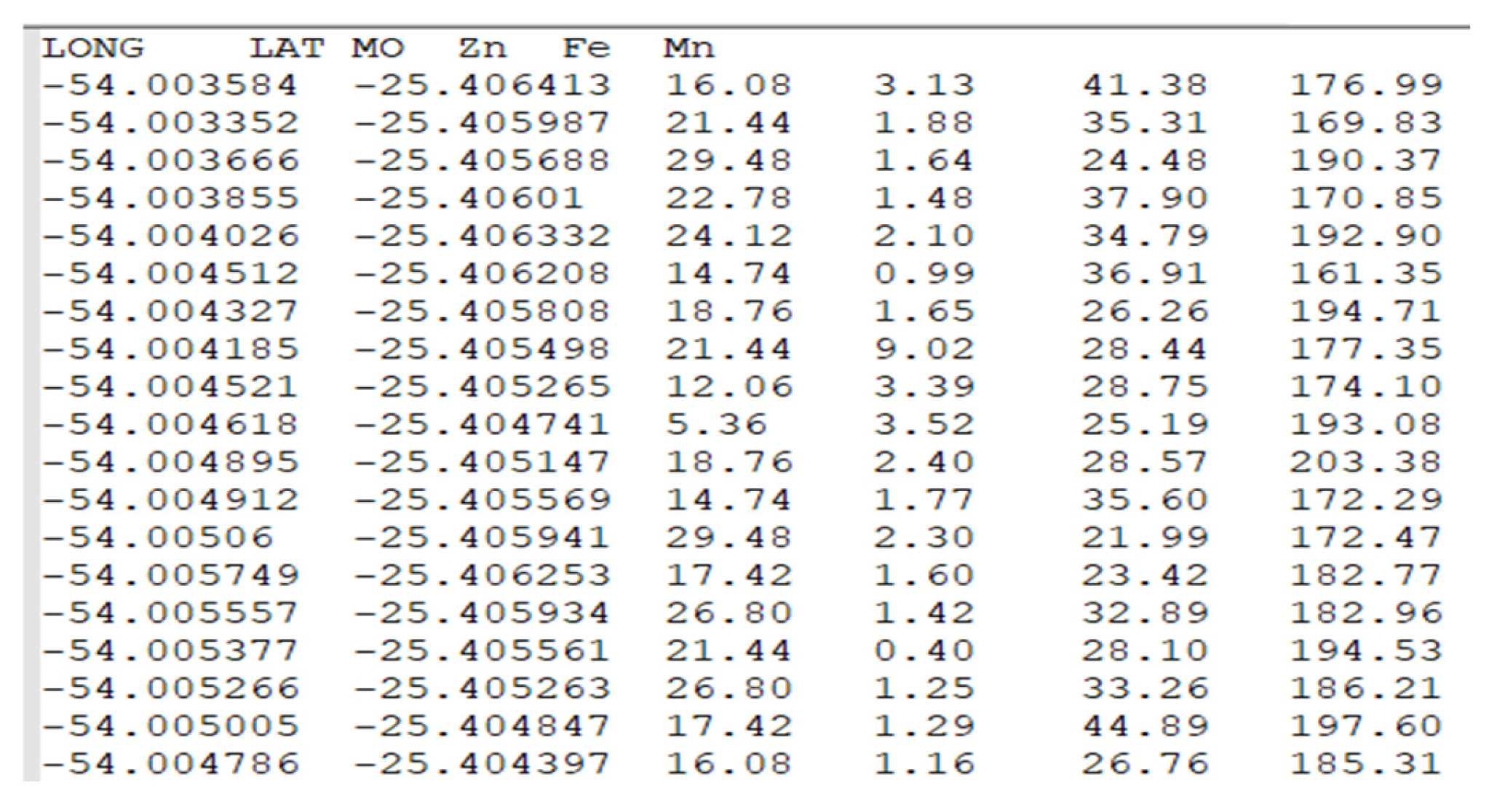

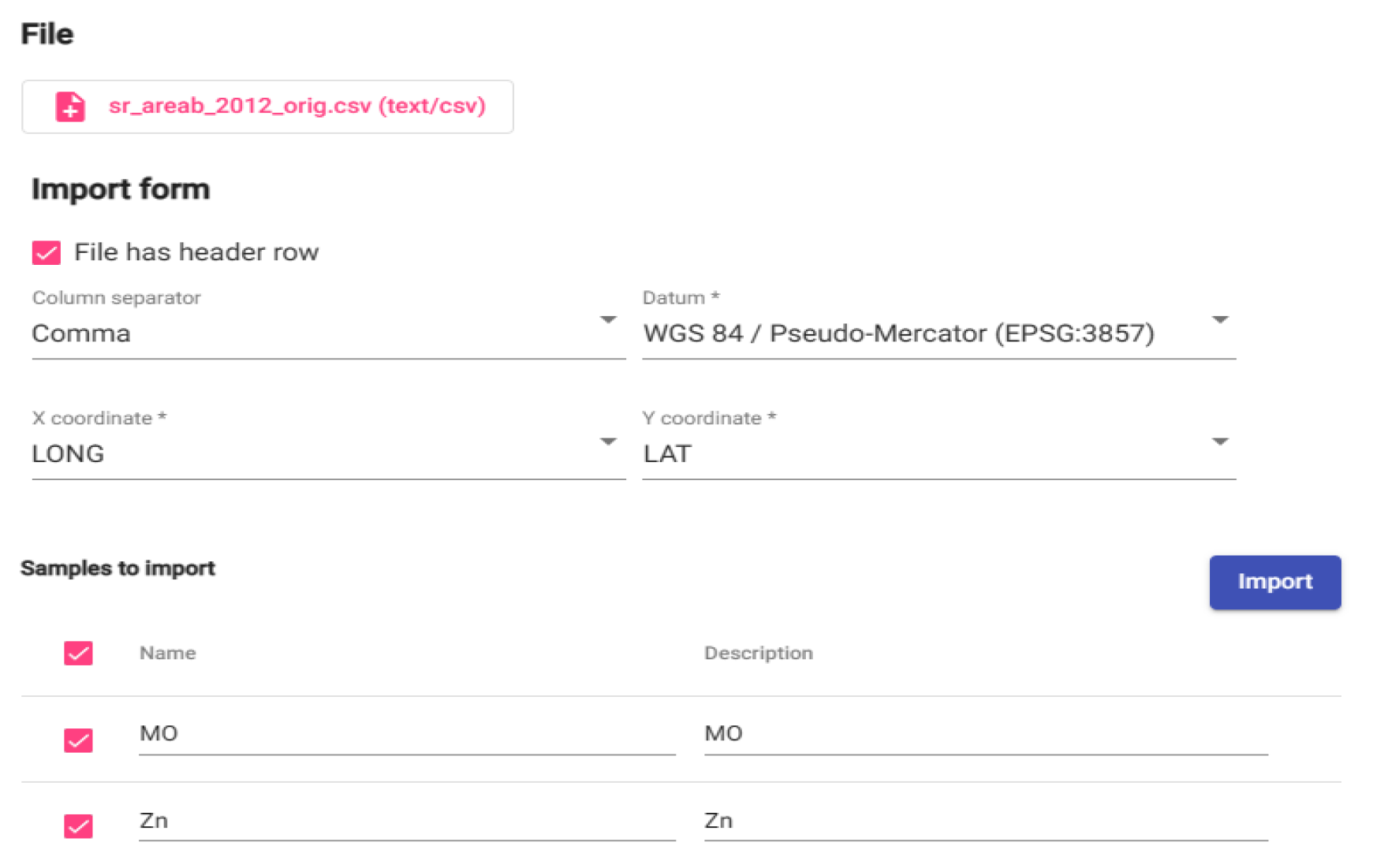

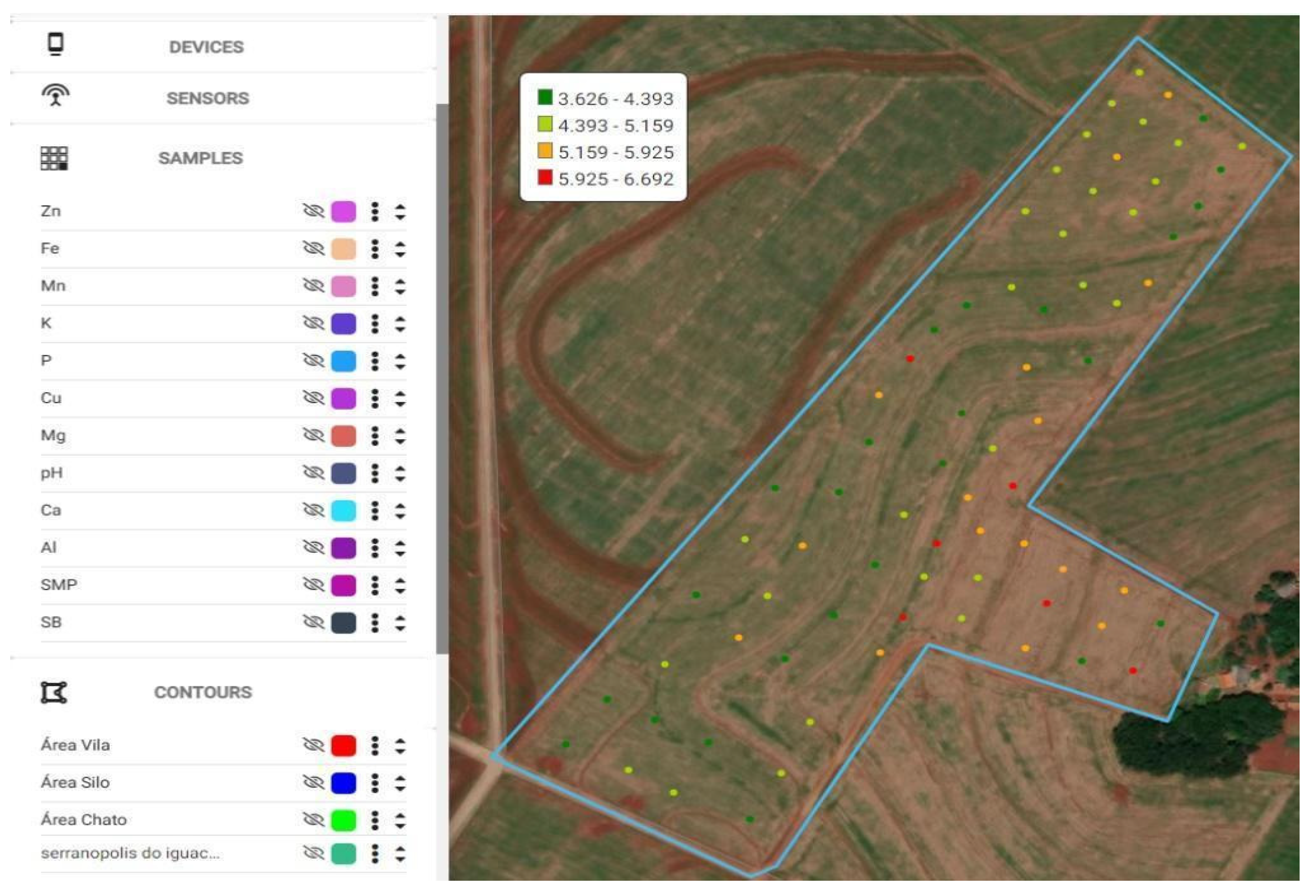

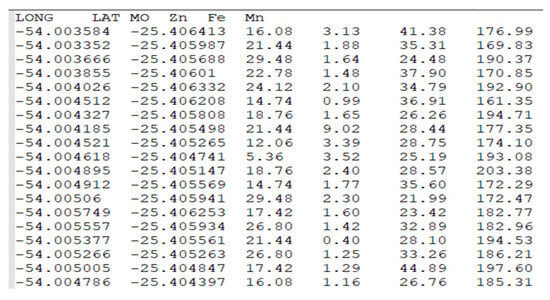

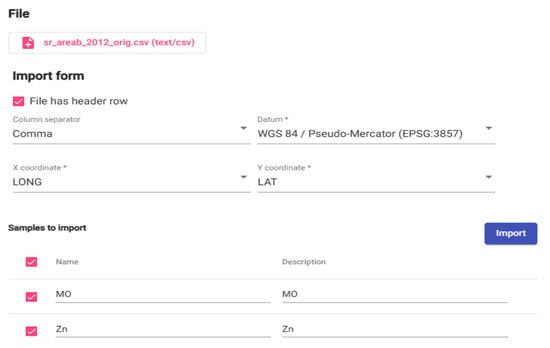

Soil samples can be registered by importing CSV or TXT files (Figure 8), which must contain geographic coordinates and at least one soil attribute (Figure 9). The application supports data visualization on an interactive map (Figure 10), allowing users to overlay fields, samples, thematic maps, and devices. A limitation is that the API does not store the data measurement scale, so it cannot be displayed in the legend.

Figure 8.

TXT file containing soil samples to be imported into the project.

Figure 9.

Sample registration screen. *—required.

Figure 10.

Screenshot of the front end displaying the application’s interface with field survey data.

3.2. IoT Control API

The IoT Control API, developed in TypeScript using MQTT, manages communication between IoT devices and the web application. It implements authentication and authorization to ensure secure data exchange. Authentication differs between devices (email/password) and the web app (token). Authorization checks are performed for messages from the web app to devices. The API supports four JSON message types: gettime, settime, getstatus, and setstatus for querying and controlling device parameters.

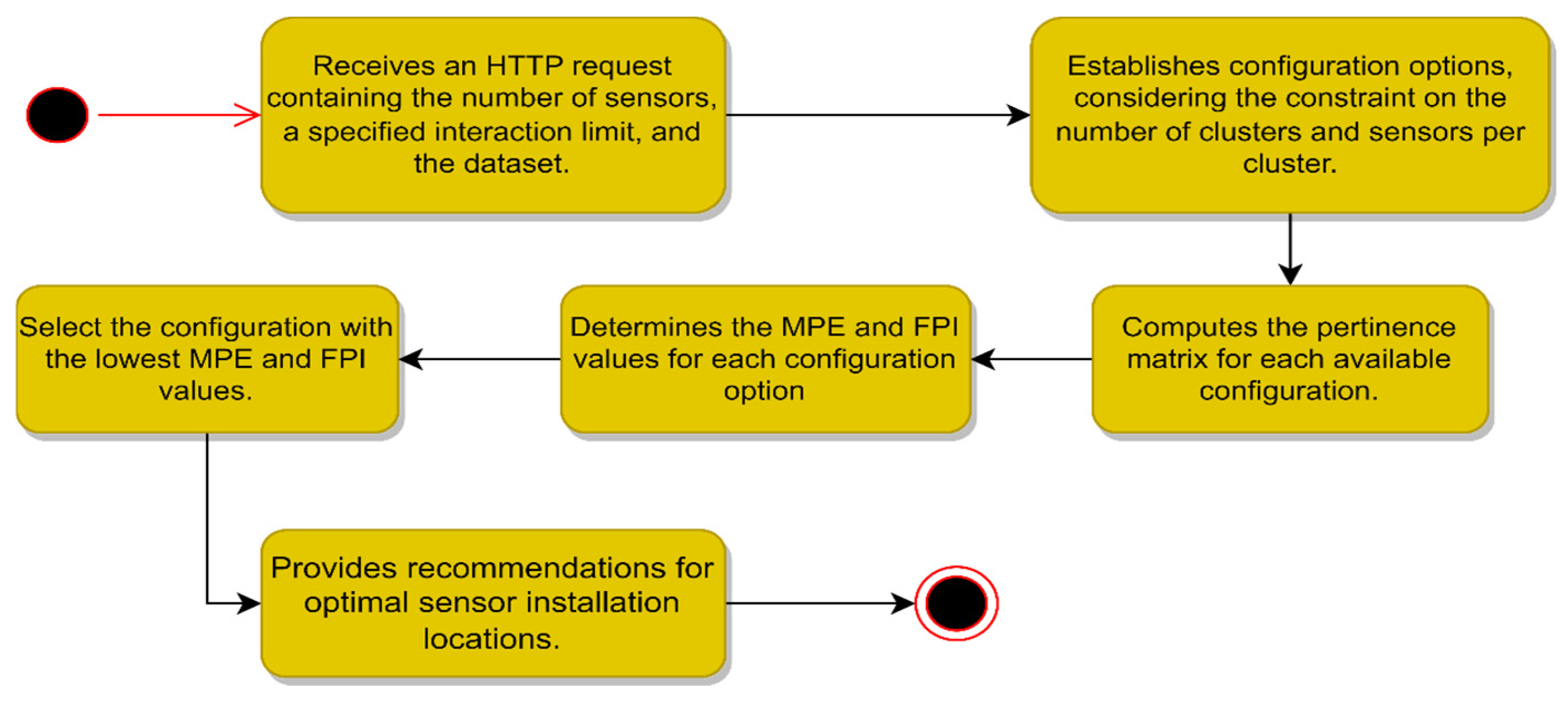

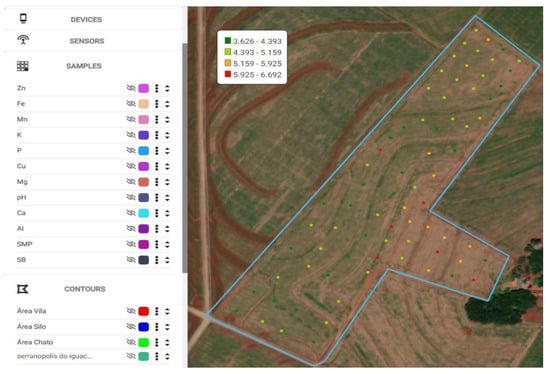

3.3. API Sensor Position

The API Sensor Position implements the modified Fuzzy C-Means method [28]. Its workflow (Figure 11) involves generating a limited number of random point combinations based on the desired number of sensors and an iteration limit. For each combination, it calculates the membership matrix, FPI, and MPE. The combination with the lowest FPI and MPE values is selected, and its points are returned as suggested sensor locations. The execution time depends on the dataset size, number of sensors, and iteration limit.

Figure 11.

Flowchart of the API sensor position for defining sensor installation locations.

3.4. Practical Application of the Module

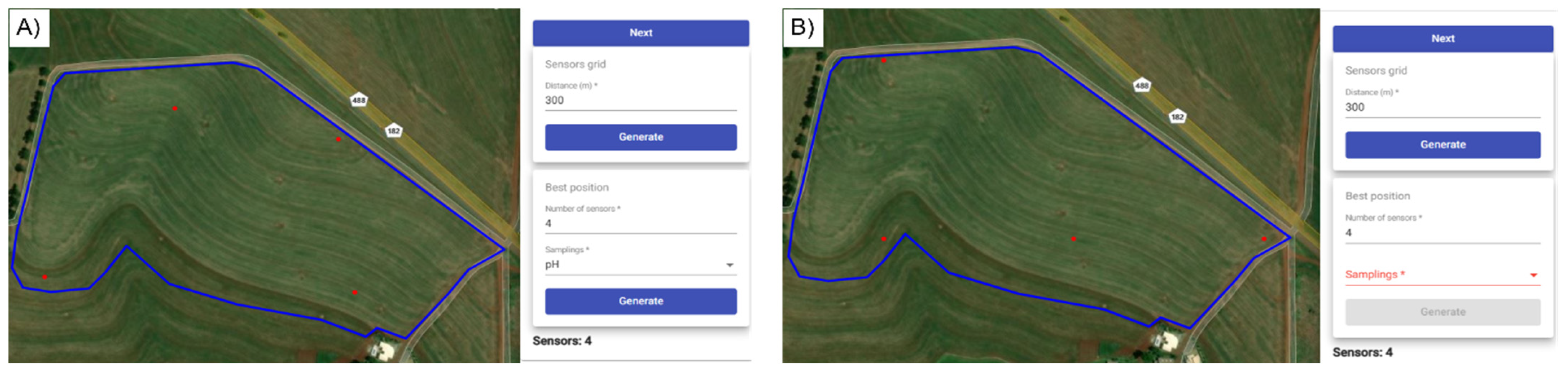

3.4.1. Planning Module

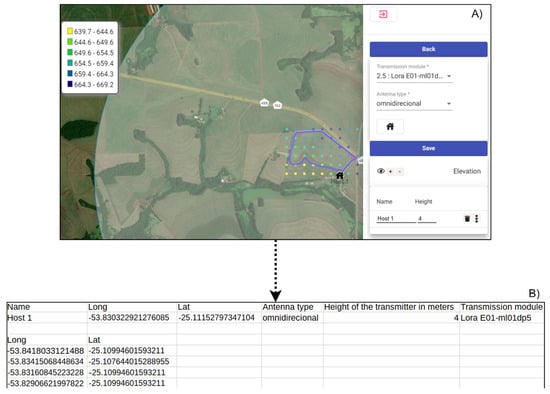

A simulation of IoT network planning was conducted for the commercial farm. Sensor planning used a grid with a 300-m spacing for each area (Figure 12). A single LoRa transmitter with a 2.5 km range was used, effectively covering all areas from a central location with internet access. The final plan, including sensor and transmitter coordinates, was exported as a CSV file (Figure 13). The simulation resulted in 28 sensor locations across the five areas (Figure 14). The planning highlighted that while the grid tool provided a good starting distribution, manual adjustments were necessary in the Sede, Chato, and Silo areas to cover regions initially lacking sensors.

Figure 12.

Sensor planning screen: sensor grid (A) and best position (B). *—required.

Figure 13.

Transmitter Planning Interface (A) and information from the CSV File Containing the IoT Network Planning (B). *—required.

Figure 14.

Result of planning an IoT network in the study area from agrometeorological stations (Kate 3.0) installed in the study area.

It is important to note that the tool allows defining suitable locations for device installation based on data layers, making this step less subjective and less random, and implementing the methodology using Fuzzy Logic.

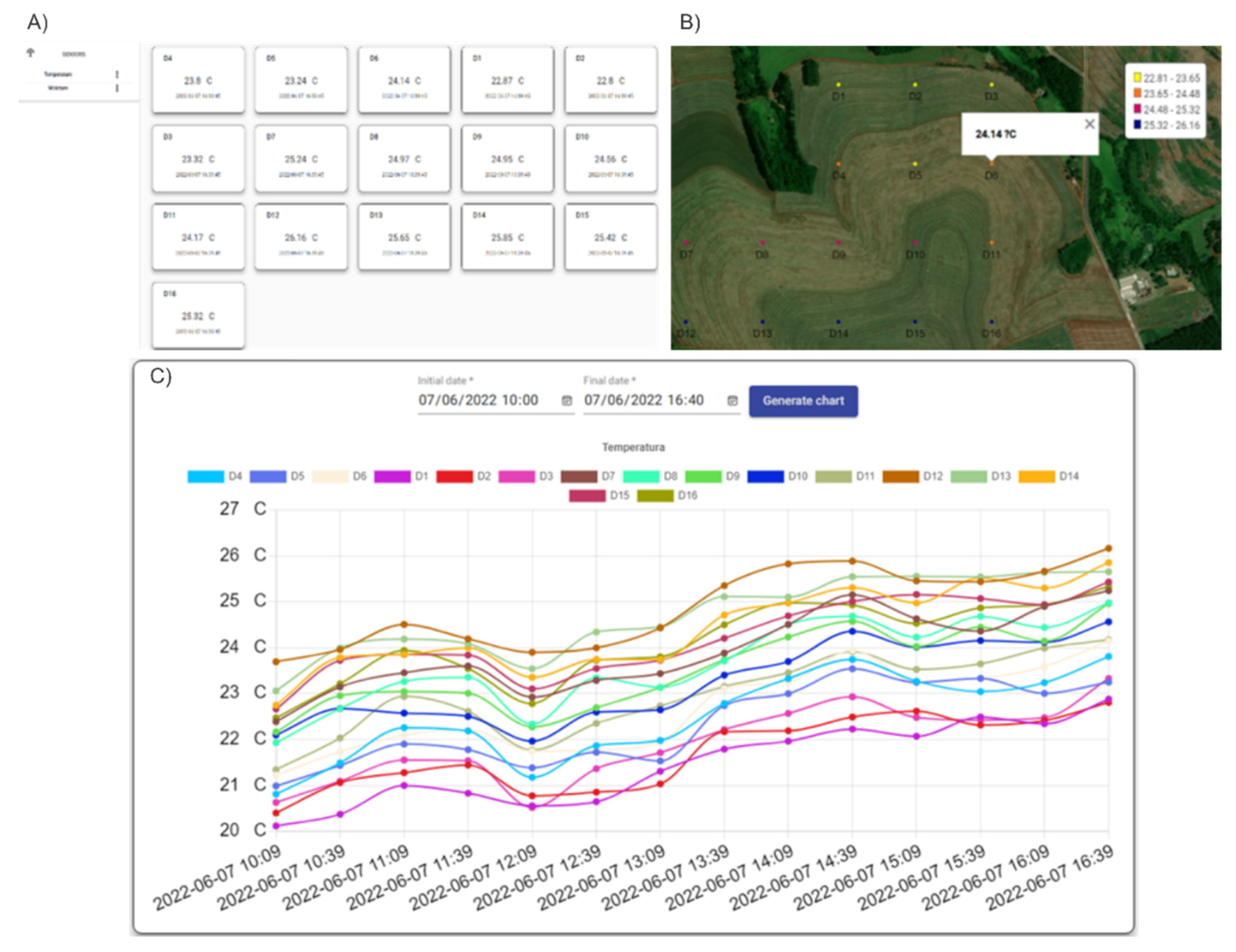

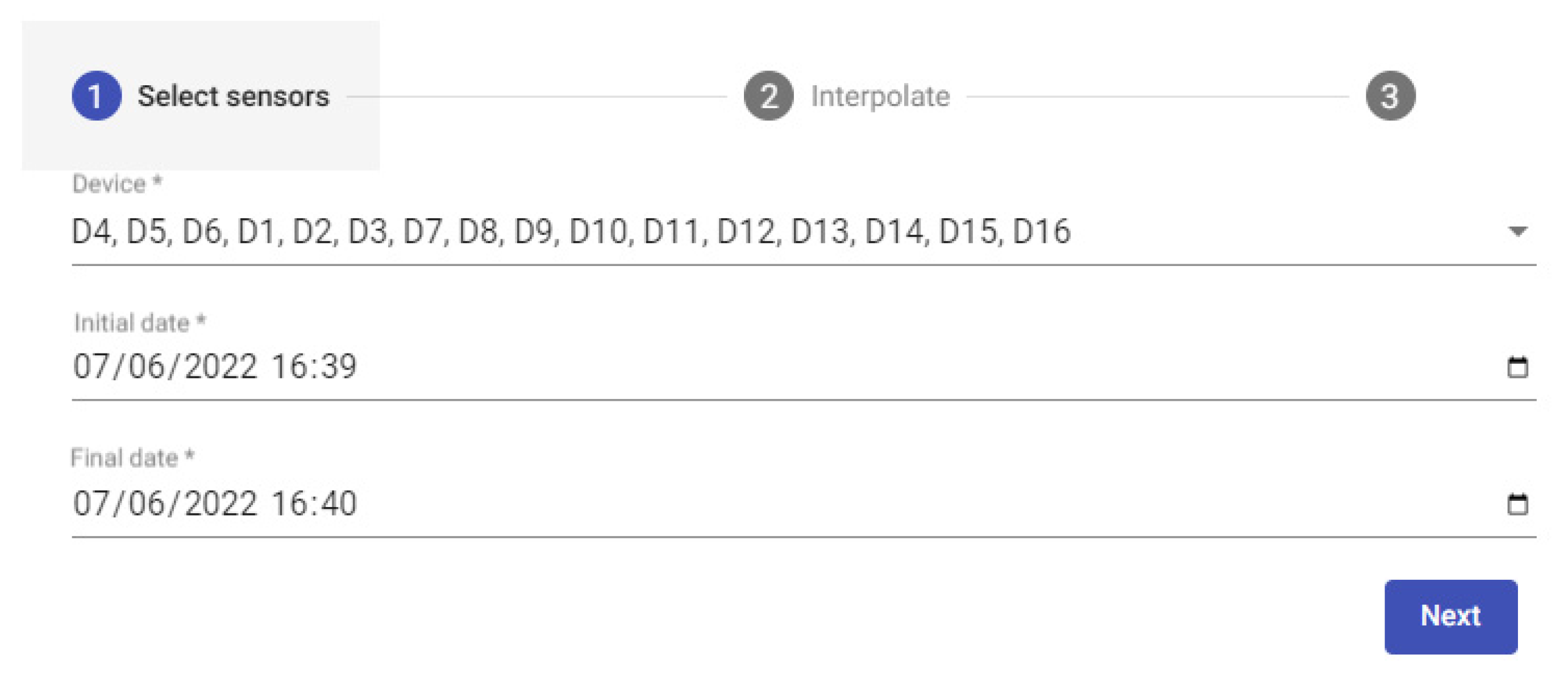

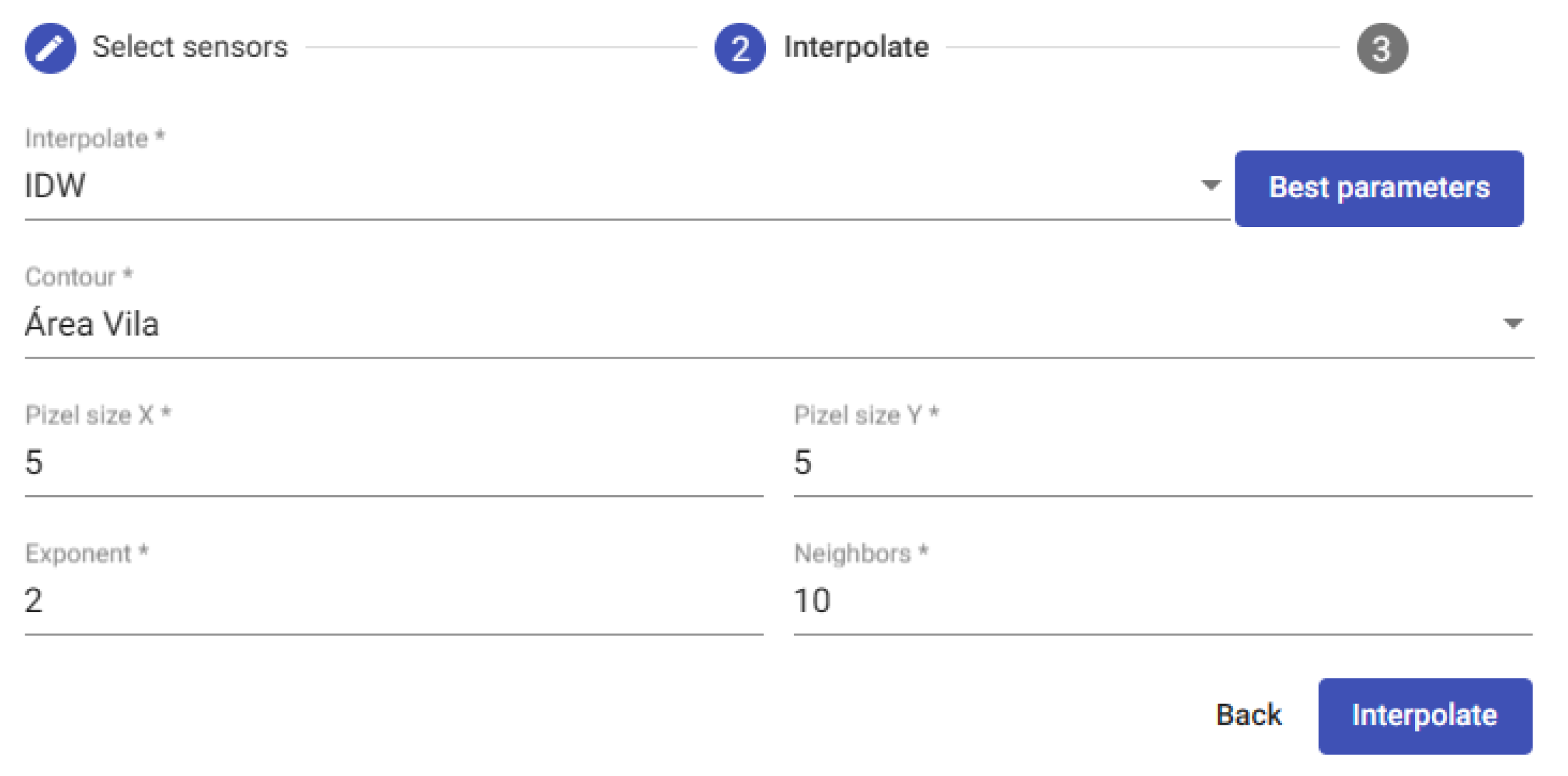

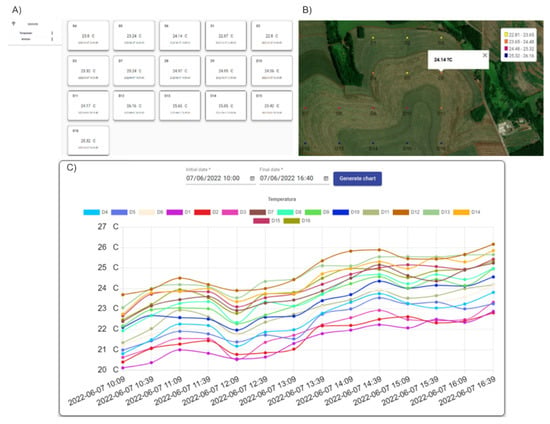

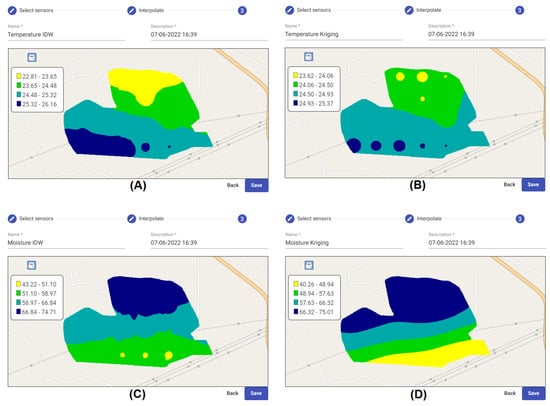

3.4.2. Monitoring Module

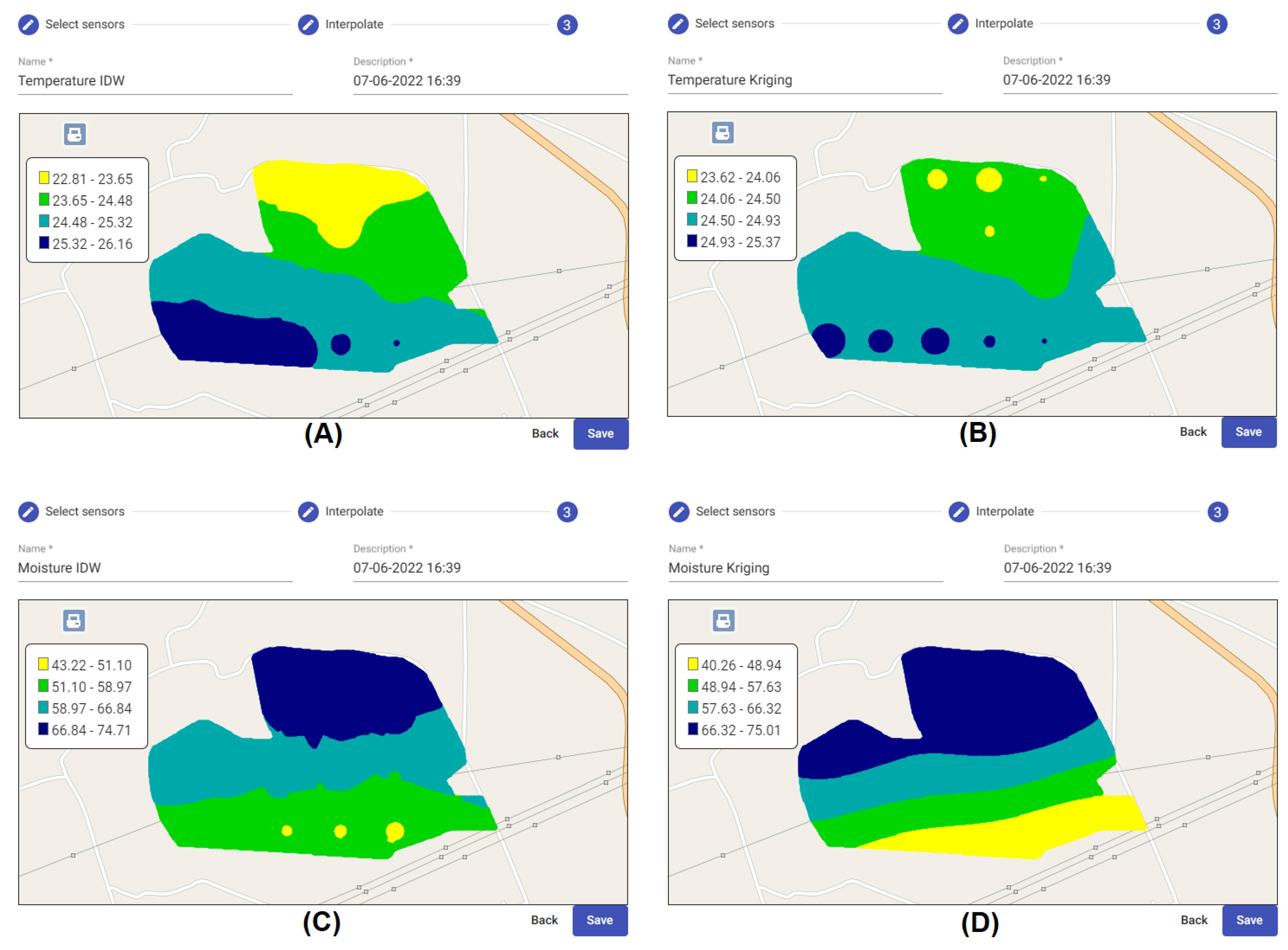

For testing, data from 16 temperature and 16 humidity sensors were manually registered to simulate an IoT network in the Chato area. The module displayed the latest readings in list and map views (Figure 15A,B). Time-series graphs allowed analysis of data variation over time (Figure 15C). After selecting devices (Figure 16 and Figure 17), thematic maps of temperature and humidity were generated using both IDW and Ordinary Kriging interpolators (Figure 18), enabling the identification of spatial patterns, such as low-humidity zones for targeted irrigation.

Figure 15.

Presentation of the latest temperature sensor readings (A), presentation of the latest readings for temperature sensors on a map (B), and data collected (C) from agrometeorological stations (Kate 3.0) installed in the study area. *—required.

Figure 16.

First stage of thematic map generation: Definition of sensors and readings. *—required.

Figure 17.

Second stage of thematic map generation: Definition of interpolator, area outline, and interpolation parameters. *—required.

Figure 18.

This text depicts the third stage of generating a thematic map based on data from the agrometeorological station Kate 3.0: Presentation of the thematic map, (A) temperature map by IDW interpolator, (B) temperature map by Ordinary Kriging interpolator, (C) moisture map by IDW interpolator, and (D) moisture map by Ordinary Kriging interpolator. *—required.

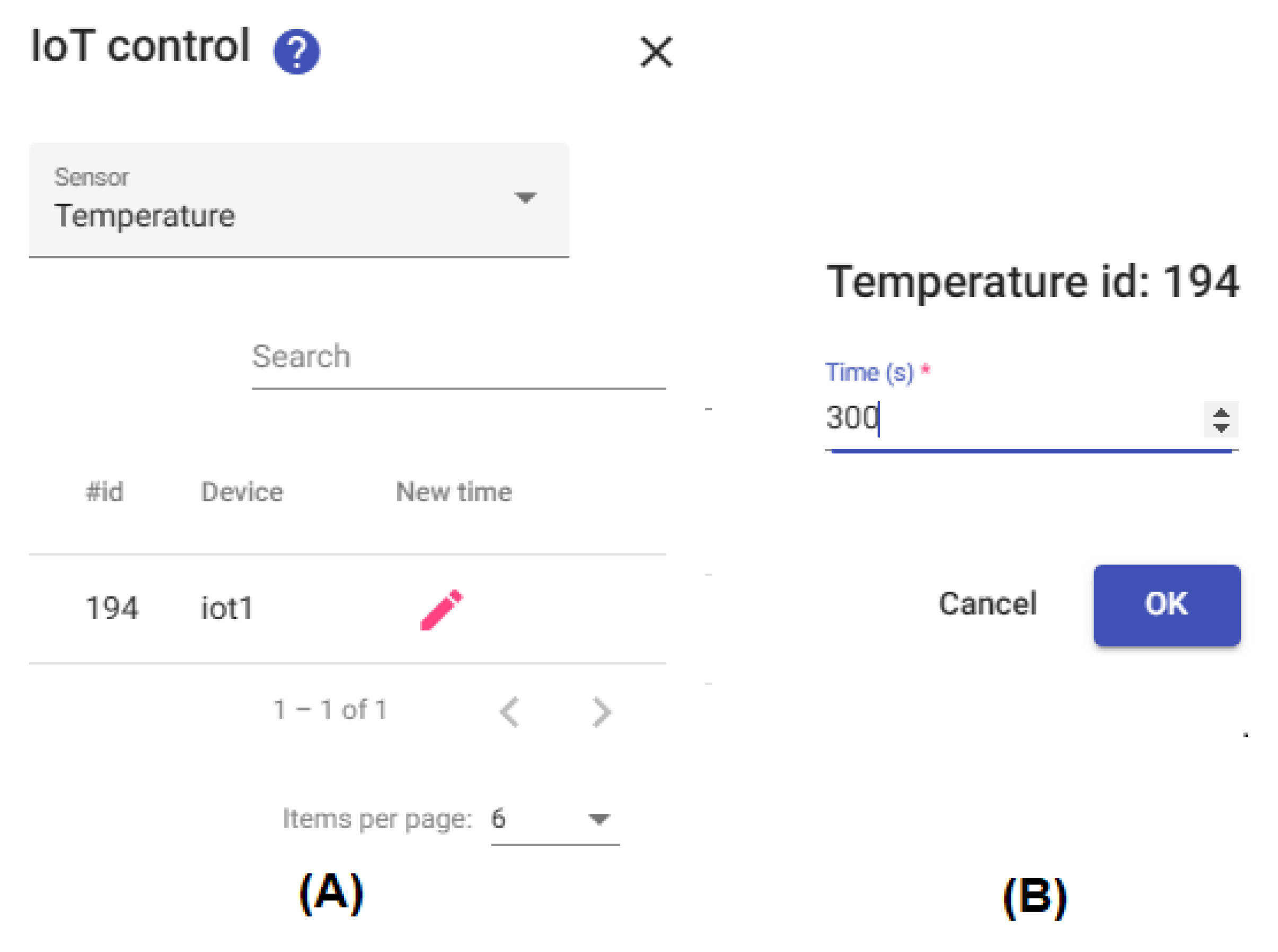

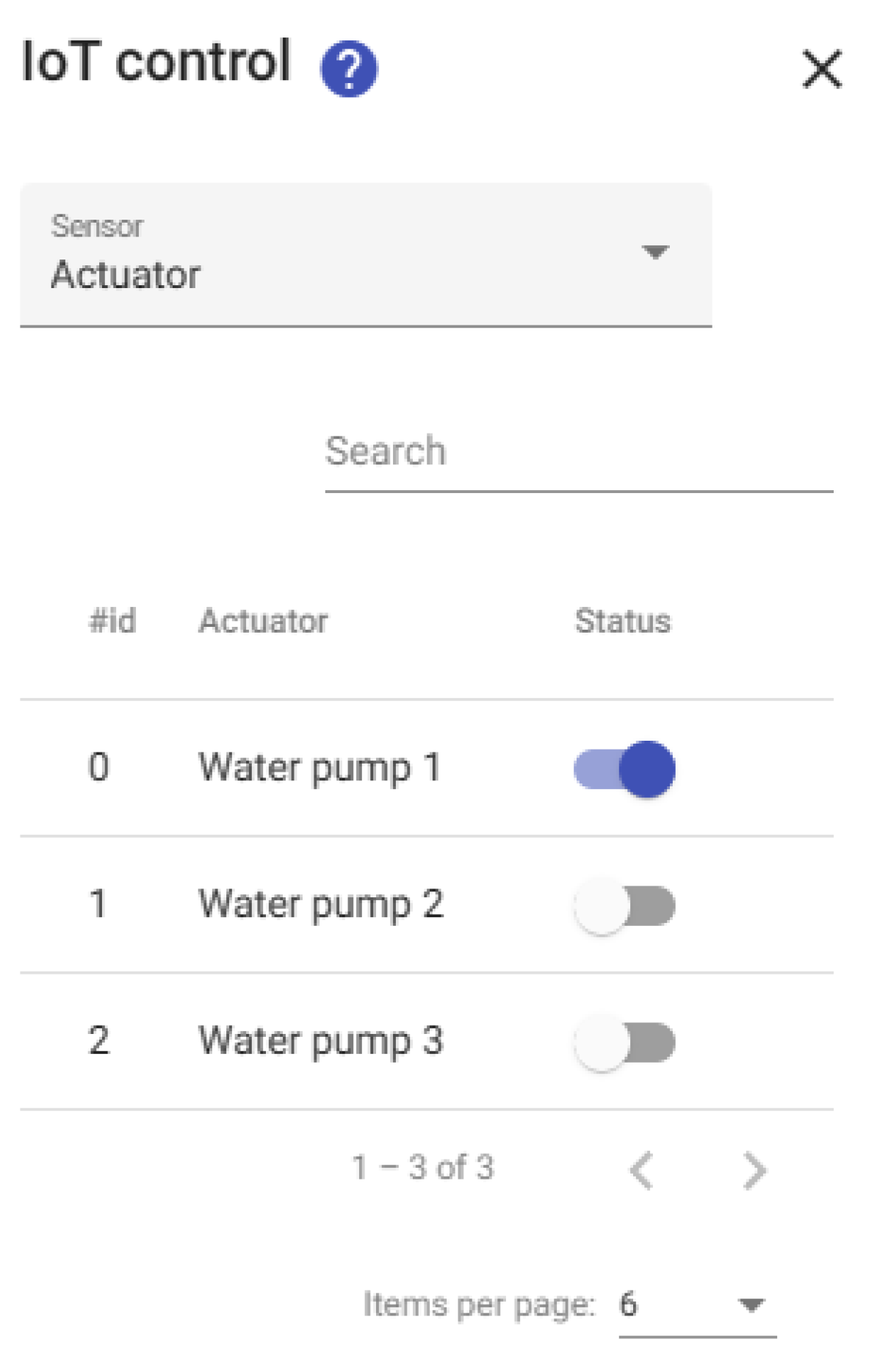

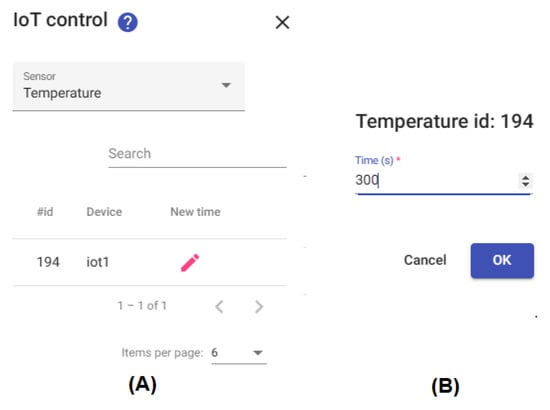

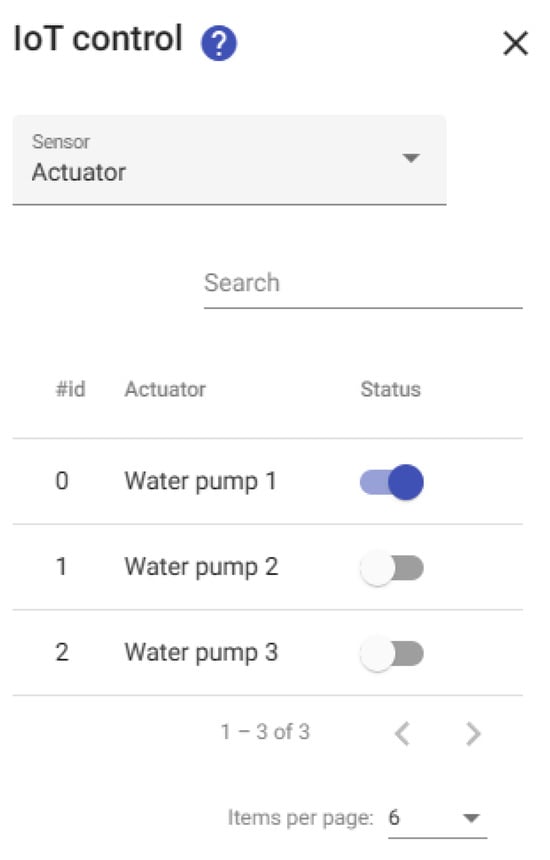

3.4.3. Control Module

The control module enables users to adjust the sensor data transmission interval (Figure 19) and modify the status of actuators (Figure 20). During testing, a command to change its transmission interval from five minutes to one minute (see Section 3.5) was successfully sent to the temperature sensors. The interface provides visual feedback (“OK” for success, “Error” for failure).

Figure 19.

Control module screen for sensors (A) and the screen to set the new data transmission interval for a sensor (B). *—required.

Figure 20.

Control module screen for actuators.

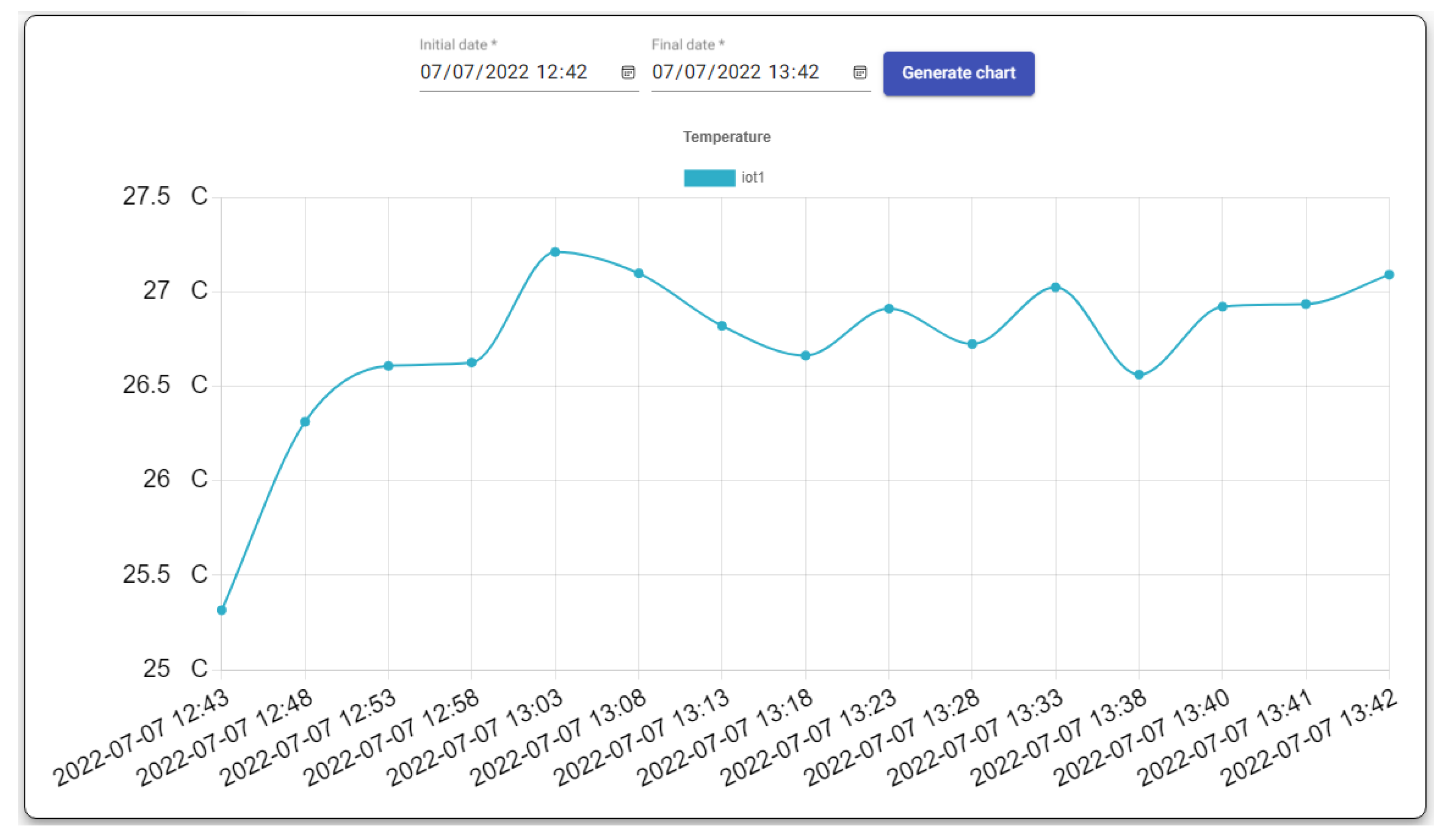

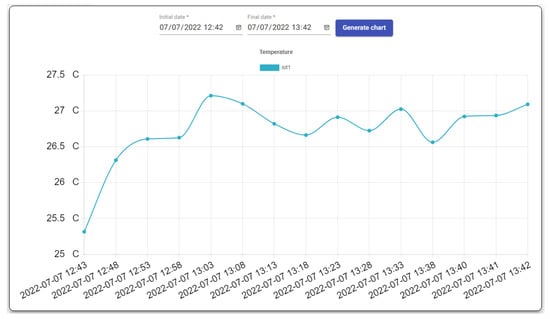

3.5. System Validation

The system’s functionality was empirically validated using data from agrometeorological stations (Kate 3.0) installed on the farm. A command was sent from the web application to change the temperature sensor’s transmission interval from 5 min to 1 min. The “OK” message confirmed receipt of the command. A graph of the sensor data (Figure 21) quantitatively verified the change, showing data points initially every five minutes and subsequently every minute, confirming the successful execution of the command.

Figure 21.

Graph of the temperature sensor for the IoT device installed in the study area at the agrometeorological station, Kate 3.0. *—required.

4. Discussion

The ADB-IoT application was successfully implemented and validated as a practical tool for precision agriculture. Its free and open-source nature promotes widespread access to technology, a significant advantage for resource-limited farmers [3,13]. The user-friendly interface enables intuitive operation, allowing users to generate thematic maps and analyze data in near real-time, which aligns with findings from similar agricultural web applications [18,30].

Compared to other open-source IoT platforms such as FIWARE or Node-RED, ADB-IoT’s novelty lies in its deep integration with a specialized agricultural data management suite (AgDataBox). While architectures based on OGC SensorThings focus heavily on standardization across diverse sensor manufacturers [23], ADB-IoT prioritizes the seamless workflow from data collection to agronomic analysis (e.g., spatial management zones). This provides a seamless workflow from data collection and IoT device management to advanced spatial analysis and decision support, a feature not commonly found in generic IoT platforms. However, unlike some commercial platforms, the current version of ADB-IoT does not include native AI-based analytics modules, representing a potential area for future development. Recent literature emphasizes that integrating AI with IoT is transformative for precision agriculture, enabling predictive analytics for disease detection and yield forecasting [14,15].

Open-source components (Angular, OpenLayers, and MQTT) were chosen to ensure full integration with the AgDataBox platform, which also uses them. This facilitates cost-effectiveness and improves maintainability and scalability. The component-based architecture facilitates the future integration of new modules, such as cloud-based analytics or AI-driven recommendation systems. The main limitations observed include the dependence on stable internet connectivity for real-time functionality, a challenge frequently cited in the deployment of innovative agricultural solutions in remote regions [15,31].

The validation in a single experimental area, while demonstrating functionality, limits the generalizability of the results. Qualitative validation of command transmission was successful, with varying results depending on the distance between the installed devices and the gateway. In the most promising scenario, with distances up to 200 m and sending one data point per minute, the transmission rate was approximately 92%, and for distances of 3 km or more, 83%. Regarding packet loss, we need to evaluate not only the farm’s terrain, but also the areas that include planting areas, forest reserves, and areas for tree planting for harvesting. This occurs irregularly in areas prone to it. Despite this, the number of losses did not affect our analysis, as a significant amount of data was still collected to monitor and communicate with the devices. Due to the modular application architecture, which is based on containerized APIs, components can be independently replicated and the main services horizontally scaled as demand increases, particularly the IoT Control API, the Open Topo Data API, and the Sensor Position API. This approach allows the application to accommodate increases in both the number of IoT devices and the volume of requests. Interaction with IoT devices is handled by the IoT Control API, which uses the MQTT protocol, enabling efficient communication with a large number of devices simultaneously due to its low overhead and publish/subscribe model.

In scenarios with limited connectivity, the MQTT protocol is an appropriate solution for message exchange, as it enables decoupling between publishers and subscribers, allowing devices to operate without simultaneous connectivity and supporting asynchronous message transmission and reception without blocking between parties. The system adopts a store-and-forward strategy, in which sensor readings are temporarily stored during network interruptions and automatically transmitted once connectivity is restored, ensuring continuous operation without loss of generated data.

Comparison with Existing IoT Platforms

AgDataBox-IoT (ADB-IoT) was compared with three widely used IoT platforms in agriculture, FIWARE, Microsoft FarmBeats, and ThingSpeak, to position its contributions within the current technological landscape. Table 3 summarizes the key differences.

Table 3.

Comparison of AgDataBox-IoT with prominent IoT platforms.

FIWARE is an open-source middleware framework offering standardized NGSI APIs for intelligent systems. Although highly scalable, it operates as an enabling infrastructure rather than a ready-to-use application [32]. Deploying FIWARE for agricultural purposes typically requires custom development, user-built interfaces, and integration of domain-specific agronomic models. In contrast, ADB-IoT provides an immediate, domain-oriented web interface for field planning, monitoring, and sensor deployment.

Microsoft FarmBeats is a proprietary, cloud-dependent platform focused on data-driven agriculture. Its main innovations include TV White Space (TVWS) connectivity and AI-powered analytics through Azure services [33]. However, its reliance on the Microsoft ecosystem introduces licensing costs, subscription dependence, and potential data sovereignty constraints. ADB-IoT avoids these barriers by being fully open-source and locally deployable.

ThingSpeak is a lightweight IoT analytics service commonly used for prototyping and development [34]. It provides live dashboards and integrates well with MATLAB, but lacks agricultural semantics and decision-making tools. Features such as management zone delineation, optimized sensor placement, or thematic map generation must be implemented manually by the user [35]. ADB-IoT overcomes these limitations through native support for soil sampling workflows, interpolation maps, MQTT device control, and fuzzy clustering for sensor network planning.

Overall, ADB-IoT occupies a distinct niche: a free, open-source, agriculture-specific platform that integrates the entire workflow from network planning to real-time monitoring without requiring proprietary infrastructure or extensive programming expertise.

5. Conclusions

This study presented ADB-IOT, a web application for precision agriculture that integrates IoT device management, data visualization, and spatial analysis into the existing AgDataBox platform. The application provides functionalities for continuous project recording, agricultural zone management, IoT network planning, real-time data monitoring, and device control. Key outcomes from the development and testing include the successful implementation of a fuzzy-logic-based sensor positioning tool, the creation of a secure MQTT-based control API, and the demonstration of the system’s ability to generate informative thematic maps and graphs.

The practical implications for farmers and agricultural engineers are significant. ADB-IoT facilitates more objective decision-making processes by providing easy access to visualized field data, thereby supporting the adoption of sustainable practices, such as targeted irrigation and precise input application. The planning module helps optimize equipment procurement and manage the costs of establishing an IoT infrastructure.

However, the study has limitations, including its validation on a single farm and the current lack of integrated actuator control. Future work will focus on (1) conducting large-scale validation across multiple farms and crop types, (2) integrating actuator control fully, (3) incorporating AI models for predictive analytics, and (4) performing rigorous performance benchmarking against other platforms.

6. Patents

- Patent Title: AgDataBox-IoT

- Patent Number: BR512024003330-0 (published on 17 September 2024)

- Assignee: Federal University of Technology—Paraná (UTFPR)

- Inventors: Bazzi, C. L.; Paula Filho, P. L.; Moreira, W. K. O.; Schenatto, K.; Franz, F. H.; Sobjak, R.

- Source: National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI), Brazil.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, F.H.F.; methodology, resources, investigation, visualization, Writing—review & editing, C.L.B.; investigation, software, formal analysis, W.K.M.O.; investigation, R.S.; resources, investigation, Writing—review & editing, K.S.; resources, software, Writing—review & editing, E.G.d.S.; resources, Investigation, Writing—review & editing, A.M.M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by CNPq (310680/2023-9), CAPES, and FPTI, as well as UTFPR and UNIOESTE, through studentships, analysis payments, and equipment purchases.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Federal University of Technology—Paraná (UTFPR), the Western Paraná State University (UNIOESTE), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPQ), the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), the Itaipu Technological Park Foundation (FPTI), and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA) and owners for the concession of the experimental fields.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/assets/Files/WPP2024_Summary-of-Results.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kendall, H.; Clark, B.; Li, W.; Jin, S.; Jones, G.D.; Chen, J.; Taylor, J.; Li, Z.; Frewer, L.J. Precision agriculture technology adoption: A qualitative study of small-scale commercial “family farms” located in the North China Plain. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, J.A.; Martínez, J.A.; Skarmeta, A.F. Digital Transformation of Agriculture through the Use of an Interoperable Platform. Sensors 2020, 20, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, B.B.; Dhanalakshmi, R. Recent Advancements and Challenges of Internet of Things in Smart Agriculture: A Survey. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 126, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Riaz, S.; Abid, A.; Abid, K.; Naeem, M.A. A Survey on the Role of IoT in Agriculture for the Implementation of Smart Farming. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156237–156271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Ammad-Uddin, M.; Sharif, Z.; Mansour, A.; Aggoune, E.H.M. Internet-of-Things (IoT)-Based Smart Agriculture: Toward Making the Fields Talk. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 129551–129583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullo, S.L.; Sinha, G.R. Advances in IoT and Smart Sensors for Remote Sensing and Agriculture Applications. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, R.K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tanaka, T.S.T.; Panda, S.K.; Koyama, H. Smart Fertilizer Management: The Progress of Imaging Technologies and Possible Implementation of Plant Biomarkers in Agriculture. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 67, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, A.; Habib, S.E.D.; Ismail, H.; Zayan, S.; Fahmy, Y.; Khairy, M.M. An IoT-Based Cognitive Monitoring System for Early Plant Disease Forecast. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 166, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachisuca, A.M.M.; Abdala, M.C.; de Souza, E.G.; Rodrigues, M.; Ganascini, D.; Bazzi, C.L. Growing Degree-Hours and Degree-Days in Two Management Zones for Each Phenological Stage of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.N.; Kumar, S.; Patel, N.R. Survey on Internet of Things and Its Application in Agriculture. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1714, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Abdollahi, A.; Al-Turjman, F.; Treiblmaier, H. The Interplay between the Internet of Things and Agriculture: A Bibliometric Analysis and Research Agenda. Internet Things 2022, 19, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibirov, A.; Dibirova, K. Prospects and Problems of Digitalization of the Agricultural Economy. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agriculture Digitalization and Organic Production, Singapore, 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, E.E.K.; Anggraini, L.; Kumi, J.A.; Karolina, L.B.; Akansah, E.; Sulyman, H.A.; Mendonça, I.; Aritsugi, M. IoT Solutions with Artificial Intelligence Technologies for Precision Agriculture: Definitions, Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Electronics 2024, 13, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Shivandu, S.K. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things (IoT) for Enhanced Crop Monitoring and Management in Precision Agriculture. Sens. Int. 2024, 5, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.K.; Bazzi, C.L.; Upadhyaya, S.; de Souza, E.G.; Magalhães, P.S.G.; Borges, L.F.; Schenatto, K.; Sobjak, R.; Gavioli, A.; Betzek, N.M. Software AgDataBox-Map to Precision Agriculture Management. SoftwareX 2019, 10, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.G.; Coutinho, C.; Costa, C.J. Factors Influencing Free and Open-Source Software Adoption in Developing Countries—An Empirical Study. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visual Studio Code. Documentation for Visual Studio Code. 2022. Available online: https://code.visualstudio.com/Docs (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Paiano, R.; Roggerone, A. MyE-Wall: Design of a Web Portal Fully Customizable and Ontology Based. BRAIN. Broad Res. Artif. Intell. Neurosci. 2010, 1, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, L. (Ed.) TypeScript-o JavaScript Moderno Para Criação de Aplicações, 1st ed.; Editora de Informática, Lda: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duldulao, D.B.; Villafranca, S.R. (Eds.) Spring Boot and Angular: Hands-on Full Stack Web Development with Java, Spring, and Angular, 1st ed.; Packt Publishing: Brimingham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nass, A.; Mühlbauer, M.; Heinen, T.; Böck, M.; Munteanu, R.; D’amore, M.; Riedlinger, T.; Roatsch, T.; Strunz, G.; Helbert, J. Approach towards a Holistic Management of Research Data in Planetary Science—Use Case Study Based on Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccatello, E.; Pagano, A.; Levorato, N.; Rumor, M. State of the Art in Internet of Things Standards and Protocols for Precision Agriculture with an Approach to Semantic Interoperability. Network 2025, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, C.L.; Jasse, E.P.; Graziano Magalhães, P.S.; Michelon, G.K.; de Souza, E.G.; Schenatto, K.; Sobjak, R. AgDataBox API—Integration of Data and Software in Precision Agriculture. SoftwareX 2019, 10, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasse, E.P.; Bazzi, C.L.; Souza, E.G.; Agnoll, R.D. Plataforma para Gerenciamento de Dados Agrícolas. In Proceedings of the XLVI Congresso Brasileiro de Engenharia Agrícola (CONBEA 2017), Maceió, Brazil, 31 July–3 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, T.H.M.; Painho, M.; Santos, V.; Sian, O.; Barriguinha, A. Development of an Agricultural Management Information System Based on Open-Source Solutions. Procedia Technol. 2014, 16, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillar, G.C. MQTT Essentials—A Lightweight IoT Protocol: The Preferred IoT Publish-Subscribe Lightweight Messaging Protocol, 1st ed.; Packt Publishing: Birmingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi, C.L.; Schenatto, K.; Upadhyaya, S.; Rojo, F.; Kizer, E.; Ko-Madden, C. Optimal Placement of Proximal Sensors for Precision Irrigation in Tree Crops. Precis. Agric. 2019, 20, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridgen, J.J.; Kitchen, N.R.; Sudduth, K.A.; Drummond, S.T.; Wiebold, W.J.; Fraisse, C.W. Management Zone Analyst (MZA): Software for Subfield Management Zone Delineation. Agron. J. 2004, 96, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydell, B.; Mcbratney, A.B. Identifying Potential Within-Field Management Zones from Cotton-Yield Estimates. Precis. Agric. 2002, 3, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, S.; Iqbal, S.; Popescu, S.M.; Kim, S.L.; Chung, Y.S.; Baek, J.H. Integration of Smart Sensors and IOT in Precision Agriculture: Trends, Challenges and Future Prospectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1587869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.A.; Cuenca, L.; Ortiz, A. FIWARE Open Source Standard Platform in Smart Farming—A Review. In Proceedings of the 19th Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises (PRO-VE), Cardiff, UK, September 2018; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasisht, D.; Chandra, R.; Kapoor, A.; Sinha, S.N.; Sudarshan, M.; Stratman, S.; Kapetanovic, Z.; Won, J.; Jin, X. Farmbeats: An IoT platform for data-driven agriculture. In NSDI’17 Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI’ 17), Renton, WA, USA, 9–11 April 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 515–529. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmad, P. Thingspeak Based Sensing and Monitoring System for IoT with Matlab Analysis. Int. J. New Technol. Res. 2016, 2, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran, G.; Kumar, N.S.; Chokkalingam, A.; Gowrishankar, V.; Priyadarshi, N.; Khan, B. IoT Enabled Smart Solar Water Heater System Using Real Time ThingSpeak IoT Platform. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.