Abstract

Prompt identification of clinical signs and early treatment of hoof problems are essential to effectively manage and reduce lameness in dairy farms. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of days in milk (DIM), parity, and milk yield (MY) on the mean temperature (MT) of the hind hooves in healthy cows, with the perspective of implementing infrared thermography (IRT) as an automated tool for early lameness detection. Thermal images were collected from 156 milking cows, capturing both cranial and caudal surfaces of each hind foot. Significant differences were found between primiparous and multiparous cows across all analyzed surfaces. Moreover, cows with higher milk production exhibited significantly higher MT in the caudal left hoof and on both cranial surfaces. The variable DIM (group 1 = cows with ≤202 DIM; group 2 = cows with >202 DIM) did not significantly affect MT on caudal surfaces; however, on the cranial view, MT of the right hoof was higher in group 2, while group 1 tended to show higher MT in the left hoof (p = 0.051). In conclusion, hoof MT increases in multiparous and high-producing cows. Additionally, during the first 200 days of lactation, cranial hoof surface temperatures tend to rise. Future studies should include continuous monitoring using automated systems to record variations throughout the day.

1. Introduction

Poor hoof health and lameness are currently prevalent issues on dairy farms, affecting animal welfare, reducing milk production, and raising breeding costs, which collectively lead to significant financial losses [1,2]. Lameness is a painful condition characterized by gait alterations and discomfort, mainly resulting from lesions or inflammation in the hooves or limbs [3]. These conditions not only cause significant suffering but also have profound effects on dairy performance, as affected cows tend to spend more time lying down, show reduced feed intake, and are consequently more prone to metabolic imbalances and secondary diseases such as ketosis or metritis [1]. In addition, chronic pain and inflammation can induce hormonal stress responses that impair reproductive function and modify behavioral patterns, further reducing fertility [4].

Hoof ailments adversely influence cattle longevity, reproduction, and milk output [5,6]. Claw abnormalities are responsible for nearly most of lameness cases (accounting for 90% of incidents), with 76–84% of foot lesions occurring in the hind limbs [7]. Consequently, lameness ranks among the most economically impactful disorders in the dairy industry [8], with each case estimated to cost over USD 200, primarily due to decreased milk production, extended calving intervals, increased culling, veterinary expenses, and the need for additional labor [3,9].

According to García-Muñoz et al. [10], promptly identifying clinical signs and treating hoof issues early are critical steps in managing and reducing lameness on farms. Early detection of infectious conditions like digital dermatitis and providing effective treatments are essential for lessening the pain and discomfort associated with lameness [11]. Leach et al. [12] and Stokes et al. [13] observed that early identification and treatment of infections that cause lameness not only halted the disease’s progression but also decreased infection levels in the herd. Regular inspection of hooves, as part of routine herd management, enables earlier identification and treatment of lesions, which can improve herd productivity and welfare [14]. However, traditional visual assessment methods such as locomotion scoring, though widely used, are labor-intensive, subjective, and time-consuming [15,16]. These systems rely on visual indicators such as asymmetrical gait, weight distribution, or back arching to identify discomfort [17], but consistency among observers often varies considerably [18,19]. Moreover, the increasing size of dairy herds has reduced the time available for individual monitoring [20], leading to frequent underestimation of lameness prevalence [21]. As a result, there is growing interest in developing automated, objective, and continuous diagnostic tools capable of detecting early physiological changes before visible symptoms appear. Besides improving welfare and productivity, early diagnosis could reduce treatment duration and antibiotic use, contributing to the mitigation of antimicrobial resistance [22].

Reliable, practical, and non-invasive methods are needed to quickly and frequently screen for diseases affecting the feet and entire cow in real time. Infrared thermography (IRT), a non-invasive diagnostic technique, visualizes and detects temperature variations on the body’s surface. IRT measures emitted radiation and show surface temperature information in the form of a thermogram, using a colour scheme [23,24]. Previous studies have demonstrated its potential to detect acute stress in broiler chickens which are reared under commercial conditions [25]; mass screening of animals for early detection of febrile diseases [26]; assessing both acute and chronic stress in animals [27]; measuring methane production from ruminants [28]; diagnosing bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) in calves [29]; early detection of mastitis in cows [30,31]; diagnosing bovine respiratory disease in beef cattle [32]; detecting oestrus in dairy cows [33]; oestrous climax determination [34]; assessing fertility index in bulls by measuring scrotal surface temperature and profile [35]; finding autonomic reactions to painful procedures performed on cattle [36]; and assessing transport stress in cattle [27], among others.

Surface and extremity temperatures are primarily influenced by blood circulation and tissue metabolism [37]. Variations in blood flow alter radiated heat, particularly in cases of inflammation in the animal’s body. Accordingly, IRT can identify inflammation or changes in metabolic activity within tissues by detecting the altered heat patterns resulting from changes in blood flow (either increased or decreased) to the extremities [38]. By detecting infrared radiation, IRT produces a visual representation of surface temperatures, offering insights into areas of localized inflammation [24], with research indicating that the surface temperature of an affected hoof’s coronary band is higher compared to that of a healthy hoof [23] supporting the potential of IRT for detecting inflammatory changes linked to lameness [23,24]. Because of that, this technique has been considered as a promising alternative for the diagnosis of lameness in cows. However, some studies showed that although IRT is capable of identify temperature elevations associated with hoof lesions, it cannot differentiate between various types of lesions [39].

To sum up, the analysis of IRT in cattle hooves is a crucial tool for advancing animal welfare and optimizing dairy farm productivity. Given the significant impact of hoof disease on cattle health, milk yield (MY), and farm economics, early detection and precise diagnosis of lameness are paramount. IRT offers a non-invasive, efficient, and reliable means to monitor temperature variations indicative of inflammation, enabling timely intervention for hoof-related disorders. Its proven versatility in detecting diverse physiological and pathological conditions across species underscores its potential as an innovative diagnostic aid in livestock management. However, it is essential to recognize that environmental factors like air temperature, dirt, and humidity can influence the accuracy of IRT. Consequently, the way cows are managed and the production system in which they are housed significantly impacts their body temperature, affecting the precision of IRT measurements [23,40]. For clarity, it should be noted that the authors applied IRT for the detection of hoof lesions, in contrast to the present study, which was conducted on healthy cows. Additionally, factors such as days in milk (DIM), parity, and MY production could influence the hind hoof maximum temperature (MT) [23]. Therefore, these factors must be analyzed to determine their real influence on hind hoof MT. The objective of this study is to evaluate how these factors affect hind hoof MT, addressing the limited information available on this topic. By integrating IRT into routine herd management, dairy producers can mitigate lameness-related losses, enhance herd welfare, and improve overall productivity, emphasizing its value as a progressive diagnostic approach in modern dairy farming.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cows and Image Record

The study was carried out on a commercial dairy farm housing 520 Holstein Friesian dairy cows located in the Northwest of Spain (Prolesa SAT, Goián, Sarria, Lugo). The herd had an average MY of 37.60 kg per cow per day and was managed under intensive free-stall housing conditions. The experiment was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles established by the European Union Legislation (Directive 2010/63/EU) and the Spanish Royal Decree 53/2013 regulating the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. All procedures were approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

Cows were kept in free-stall barns equipped with individual sand-bedded cubicles and concrete floors in the alleys, which were mechanically cleaned several times per day to ensure adequate hygiene and minimize moisture accumulation. Animals were milked three times daily (at approximately 6:00, 14:00, and 22:00 h) in a rotary milking parlour, and MY was automatically recorded at each milking. Feeding was based on a total mixed ration formulated to meet the nutritional requirements of high-yielding Holstein cows, with ad libitum access to feed and water. Hoof trimming was routinely performed twice per year—once before the dry-off period and again around mid-lactation—to maintain hoof balance and prevent overgrowth.

For this study, a total of 368 cows with a range of 27 to 528 DIM were initially examined. Only clinically healthy cows with no visible signs of lameness or hoof lesions were retained in the dataset, resulting in a final sample of 156 individuals. This selection was made to eliminate any influence of subclinical or clinical lameness on hoof surface temperature and to establish normal thermographic reference values.

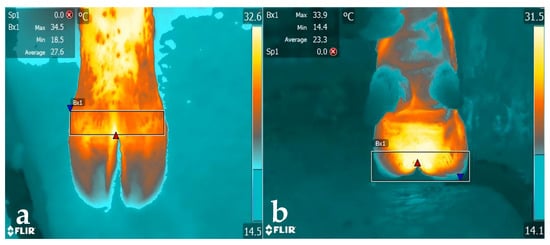

Thermal data were collected between December 2023 and June 2024, ensuring representation of different environmental conditions throughout the winter and spring seasons. Images were obtained from both hind hooves, capturing two anatomical perspectives: the cranial (CR) and caudal (CD) surfaces. The specific rectangular area analyzed in each thermogram is indicated in Figure 1. To minimize disruption to farm operations and animal behavior, data collection was integrated into routine management activities. A total of 69 cows were imaged while standing calmly in the stall-feeding corridor, whereas 87 cows were evaluated while restrained in the hoof-trimming chute. This combination allowed comparison of imaging under different restraint conditions without significantly affecting the thermal readings.

Figure 1.

IRT images of a Holstein cow’s hind hoof, cranial (a) and caudal (b) sights. The rectangular area represents the analysed surface.

Thermal images of the coronary band were taken from a fixed distance of 94 ± 10 cm, which was determined using a laser distance meter to standardize the measurement and minimize variability associated with camera distance. The time of image acquisition was kept constant for all animals to avoid the influence of diurnal temperature variation. For the group of cows examined in the feeding corridor, each individual was subsequently released, and the locomotion score (LS) was assessed according to the criteria described by Sprecher et al. [41]. The LS was determined by a trained observer who was independent from the operator collecting the IRT images to prevent observer bias. For cows examined in the trimming chute, all four feet were lifted and visually inspected by a certified professional hoof trimmer to confirm the absence of lesions or abnormalities.

2.2. Infrared Thermography

Thermal images were acquired using a FLIR E95 infrared camera (Teledyne FLIR, Wilsonville, OR, USA), with a spectral range of 7.5–14 µm and a thermal sensitivity of <0.03 °C at 30 °C. The emissivity value was set at 0.95, consistent with that reported for bovine skin and keratinous tissue. The camera’s calibration and thermal accuracy were verified using a mercury thermometer maintained at a constant temperature of 45 °C before each imaging session.

To preserve the authenticity of the on-farm management routine, the hooves were not washed prior to imaging, following the recommendations of Stokes et al. [10], since washing may temporarily alter surface temperature through cooling or friction. All recordings were made in shaded areas, avoiding both direct and reflected sunlight, which could affect thermal readings. Environmental parameters were carefully monitored: ambient temperature and relative humidity were recorded at the start, middle, and end of each data collection session using a digital thermo-hygrometer. These environmental measurements were subsequently incorporated into the calibration protocol of the thermal camera. Throughout the data collection period, the average ambient temperature was 15 °C (range 11–21 °C), and the mean relative humidity was 85% (range 70–95%).

Thermal data were analyzed using FLIR Tools software, version 5.2.15161.1001 (2015). The MT of each region of interest was extracted automatically by defining rectangular search areas over the coronary band (as shown in Figure 1). These regions were selected to ensure reproducibility and to avoid inclusion of areas affected by mud or debris. Core body and ocular temperatures were not recorded, in order to simplify the protocol and enhance the applicability of IRT as a field-based diagnostic technique for early lameness detection.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.1.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Cows were classified according to LS—Healthy (LS = 1), Subclinical (LS = 2), and Clinical (LS = 3–5)—which was treated as a categorical variable. Similarly, feet were categorized as either healthy or with hoof lesions, although only the data from the 156 healthy cows were retained for final analysis.

The factors considered in the statistical model included parity (1 = primiparous (n = 55) 2 = multiparous (n = 101)), DIM (group 1 = DIM ≤ 202 (n = 88), group 2 = DIM > 202 (n = 68)), and MY (Low = MY ≤ 38.23 kg/day (n = 124), High = MY > 38.23 kg/day (n = 32)). DIM and MY were dichotomized according to their median values to ensure balanced group sizes. The dependent variables were the MT measurements recorded in both the CR and CD views of each hind hoof, which were treated as continuous quantitative variables.

The influence of DIM, MY, and parity on MT was evaluated using a univariate general linear model (GLM). This model allowed the estimation of the main effects of each factor while controlling for potential interactions. Data were tested for homogeneity of variance using the Levene test and for normality through analysis of skewness and kurtosis, considering acceptable values between −0.5 and +0.5. Outliers were examined individually to verify data consistency. Differences were considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Additionally, descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were calculated for all measured variables. The use of the GLM allowed the evaluation of whether parity, milk production, and stage of lactation independently contributed to variations in hoof surface temperature, providing a robust framework for identifying physiological factors affecting thermal patterns in healthy dairy cows.

3. Results

The results obtained from the univariate GLM analysis revealed that parity, DIM, MY, had measurable effects on the MT of the hind hooves in the analyzed regions.

3.1. Effect of Parity on Hoof Surface Temperature

Significant differences were observed between primiparous and multiparous cows across all hoof regions analyzed (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 1, primiparous cows consistently exhibited higher MT values than multiparous cows in both CD and CR views of the left and right hind hooves. On average, the surface temperatures of primiparous cows were approximately 5–7% higher than those of multiparous individuals. This difference was particularly marked on the CR surfaces, where the mean MT values of primiparous cows exceeded those of multiparous cows by about 2 °C. A similar pattern was observed on the CD surfaces, with younger cows again showing higher readings.

Table 1.

Maximum temperatures (°C) in the studied hoof areas related to the parity.

These findings indicate that younger cows tend to maintain higher peripheral surface temperatures, possibly reflecting increased blood flow, metabolic activity, or differences in keratin tissue turnover between parity groups.

3.2. Effect of MY on Hoof Temperature

Milk production also showed a significant effect on hoof temperature in several regions. As summarized in Table 2, high-producing cows showed higher MT values than low-producing ones, particularly in the CD left, CR left, and CR right areas (p ≤ 0.05). The temperature differences ranged from 2–4%, suggesting that cows with greater milk yield maintain slightly higher hoof surface temperatures. The only exception was the CD right hoof, where temperature remained comparable between groups (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Maximum temperatures (°C) in the studied hoof areas related to the MY.

Overall, these results suggest that cows with greater MY tend to exhibit higher hoof surface temperatures, likely reflecting elevated blood perfusion and tissue metabolism associated with increased nutrient mobilization and energy expenditure during high milk production phases.

3.3. Effect of DIM on Hoof Temperature

The analysis of lactation stage showed that DIM did not significantly affect the MT of the CD surfaces in either hoof (p > 0.05). As indicated in Table 3, mean MT values were almost identical between cows in Group 1, ≤202 DIM and Group 2, >202 DIM, differing by less than 1% in both the left and right hooves.

Table 3.

Maximum temperatures (°C) in the studied hoof areas related to DIM.

In contrast, more noticeable trends appeared in the CR regions. The CR right hoof exhibited a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05), with Group 1 showing approximately 2% higher MT values than Group 2. A similar tendency was found in the CR left hoof (p = 0.051), where early-lactation cows also maintained slightly warmer surfaces. Across all the models analyzed, parity consistently emerged as the most influential factor affecting hoof temperature, followed by MY, whereas DIM exhibited a subtler effect, particularly in the CR regions. Despite the moderate variability observed (reflected by standard deviations between 3–5 °C), the statistical associations remained robust. The higher hoof surface temperature observed in primiparous and high-producing cows supports the hypothesis that metabolic and physiological activity strongly modulates thermal responses at the hoof level. These findings also reinforce the importance of considering individual cow characteristics—such as parity, MY, and lactation stage—when interpreting thermographic data for the early detection of hoof pathologies or lameness.

4. Discussion

Previous studies highlighted the relevance of MT measured via IRT compared to other metrics such as minimum or average temperature [13,42]. In our study we used the MT as it has been reported to provide the most consistent results [13]. At the same time, Rainwater-Lovett et al. [42] reported a positive correlation between hoof temperature and other physiological variables, such as body and ocular temperature. However, in our study, body and ocular temperature were not measured, which is a limitation. This will be implemented in future research. Lin et al. [43] further demonstrated that hoof temperature obtained by IRT was strongly associated with lameness scores, with lame cows showing higher values than sound cows, reinforcing the physiological link between local inflammation and increased thermal emission. This relationship, however, was not evaluated here since only healthy animals were included. Nevertheless, the positive association between IRT measurements and clinical or subclinical inflammatory states supports the potential of IRT to identify early physiological variations even within normal ranges of hoof health.

In contrast to a variety of other exterior body surfaces, the IRT of the limbs fluctuates significantly during the day in response to changes in feed intake [44]. This phenomenon is likely due to the extensive blood circulation that the muscular structure of the coronary band of limbs requires [23]. For this reason, future studies should incorporate repeated daily measurements or continuous monitoring systems, since circadian fluctuations, ambient temperature, and animal activity could contribute to the variability observed among individuals. Additionally, the latter study argued that MT is a reliable and feasible measure, even with affordable devices.

Previous studies have explored the relationship between lactation stage and hoof characteristics in dairy cows. Nikkhah et al. [45] analysed 16 cows twice; either in early/mid-lactation (≤200 DIM) or in late lactation (>200 DIM). In their results, they obtained higher hoof temperature and a higher incidence of sole haemorrhage in cows during early lactation, because of the higher incidence of laminitis in this group. However, in our study we only measured MT in healthy cows, in order to avoid lameness influence in the hind hoof MT. Nonetheless, we found higher MT in cows in group 1 (DIM ≤ 202) and higher MY. These results align with previous findings indicating that early-lactation cows typically display higher peripheral temperatures, which may be associated with greater metabolic heat production, higher blood flow, and potential inflammatory responses linked to the physiological stress of peak MY. One possible explanation could be the greater MY during this stage and the consumption of more concentrated diets, which increase nutrient metabolism, reduce rumen pH, and elevates the likelihood of hoof inflammation and laminitis [46]. Moreover, Uddin et al. [47] affirmed that cows with lower DIM consume more feed to meet the demand for higher milk supply and higher blood flow to support it. Cows with higher MY and fewer DIM often experience a Negative Energy Balance, which induces metabolic stress. This stress elevates the production of cortisol, the hormone associated with stress. Elevated cortisol levels, in turn, lead to an increase in body temperature due to enhanced blood flow [48]. On the other hand, compared to cows with more DIM, which would be more likely to be pregnant, cows with lower DIM may also be more likely to be in oestrus [49]. Although, cows only are in oestrus the 10% of the time, it must be considered that cows in oestrus, due to the increased physical activity, vaginal blood flow, LH surge, ovulation, and progesterone release during the luteal phase, are likely to have an increase in body temperature [33].

Our results indicated that cows with a higher number of calvings exhibited significantly lower MT compared to primiparous cows, consistent with the findings of Nikkhah et al. [45] and with subsequent research by Bobić et al. [50]. In the study of Nikkhah et al. [45] they divided the cows in two groups, where group one included cows with one or two calvings (MT = 24.0 ± 1.2 °C) and group two included cows with three or more calvings (MT = 22.4 ± 1.6 °C). These results may be explained by the greater growth of keratinous tissue in younger cows, which requires an increased blood supply, and by the possible influence of stress caused by human presence during imaging, which might be more intense in younger cows, increasing cortisol production [51]. High levels of cortisol lead to an increase in temperature due to an increased blood flow [48]. Alternatively, Renn et al. [52] suggested that adult cows are more prone to rear limb injuries, while heifers are more often affected in the front limbs, potentially due to changes in hoof formation after calving.

Hoof cleanliness also plays an important role in thermography accuracy. Dirt can alter the emissivity and thermal conductivity of the surface [11,13]. Although Alsaaod et al. [11] emphasized that IRT is effective only on clean hooves, Stokes et al. [13] found higher diagnostic accuracy in unclean hooves, arguing that cleaning could alter the thermal profile due to cooling or friction. In this study, hooves were not cleaned following Stokes et al. [13] directions, and to automatize its use by not interfering in the farm daily routine.

Another factor affecting thermography is the distance between the object and the infrared camera, as greater distances reduce detected temperatures [28]. Because of that, in our study all the data was recorded at 94 ± 10 cm. Moreover, animal characteristics, such as coat colour, also influence readings: dark coats absorb more solar radiation, which increases body surface temperature [53]. Similarly, recent sun exposure or physical activity can elevate body temperature due to increased metabolism [54]. Due to the characteristics of the farm used, the animals did not have direct exposure to the sun at any moment. Furthermore, long waiting time before milking allows cows to release more heat from their limbs or to be cooled by sprinklers, thus reducing limb’s IRT [47]. Environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity were also relatively constant across sessions, likely contributing to the stability of our data, in line with observations from Casas-Alvarado et al. [55] and Wood et al. [39], who highlighted the need to control environmental variability when using IRT.

The present findings can confirm the reliability of MT as an indicator of hoof surface thermal state. Similarly to the conclusions of Stokes et al. [13] and Rainwater-Lovett et al. [42], the use of maximum temperature rather than mean or minimum temperature provides a clearer and more consistent reflection of physiological changes. This advantage, combined with the non-invasive nature and ease of automation of IRT, reinforces its value as a practical and cost-effective diagnostic tool. In the context of precision livestock farming, the integration of IRT with automated lameness detection systems could enhance early identification of hoof disorders, as suggested by Werema et al. [40], who emphasized that thermography provides a more objective and less labor-intensive approach than traditional locomotion scoring. Furthermore, combining IRT with other digital technologies such as accelerometers or pressure sensors may improve diagnostic accuracy and enable real-time detection of subclinical lameness, as proposed by Renn et al. [52].

In summary, our study supports the use of IRT for assessing physiological variations in hoof temperature associated with parity, MY, and lactation stage, providing valuable baseline information for future implementation of automated health-monitoring systems. Although our research was limited to healthy animals, the integration of these findings with data from clinically lame cows would allow the establishment of more precise thresholds for early lameness detection. Future research should aim to include continuous thermal recording across different times of day and physiological states, ideally complemented by behavioral or hormonal data, to refine the understanding of how metabolic and environmental factors shape hoof thermal patterns.

5. Conclusions

We concluded that MT is increased in multiparous cows compared to primiparous cows. At the same time, hoof MT is increased in high milk-producing cows compared to low milk-producing cows. Finally, we discovered that during the first 200 days of lactation, the MT on the CR surface of the hind hooves is increased compared with cows at more than 200 DIM. These findings demonstrate that parity, milk yield, and lactation stage influence hoof surface temperature in healthy animals, likely reflecting underlying physiological and metabolic changes.

Future research should focus on implementing automated, continuous IRT monitoring to establish individual thermal baselines, incorporate daily temperature fluctuations, and evaluate cows at different health stages. Studies integrating hoof MT with other physiological indicators and assessing environmental and management factors would help refine thermal thresholds for early detection of hoof disorders. Integrating IRT into milking parlors, robotic systems, or barn passageways could enhance real-time hoof health monitoring, reduce the need for manual inspections, and improve welfare and productivity. Combining IRT with sensor-based systems and machine learning may further advance precision dairy management.

6. Recommendations

This study also supports the development of practical, actionable recommendations for dairy herd management. Implementing routine IRT-based monitoring in milking parlors, robotic milking units, or barn passageways could provide caretakers with continuous, real-time information on hoof thermal patterns, facilitating the early identification of deviations from expected values. Establishing farm-specific temperature reference ranges and integrating thermographic checks into existing management protocols would help farmers prioritize animals requiring closer inspection, thereby reducing labor demands and minimizing unnecessary handling. Furthermore, incorporating IRT within broader herd-monitoring systems, alongside behavior, activity, or production data, could assist in management strategies to different lactation stages, ultimately supporting proactive hoof-care programs. Looking ahead, combining IRT with automated tools such as a neck-mounted accelerometer sensor system may enable farms to shift toward preventive health management models that improve welfare, optimize resource use, and enhance long-term sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., J.Á., U.Y. and L.Á.Q.; methodology, A.A., L.Á.Q. and U.Y.; formal analysis, A.A., U.Y. and L.Á.Q.; investigation, R.H., R.B., L.V., R.G., A.A., J.Á., L.Á.Q. and U.Y.; resources, L.Á.Q., J.J.B., A.I.P. and P.G.H.; data curation, A.A. and J.Á.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A. and J.Á.; writing—review and editing, A.A., U.Y. and L.Á.Q.; visualization, A.A., R.B., R.H., R.G. and L.V.; supervision, J.J.B., P.G.H., A.I.P., L.Á.Q. and U.Y.; project administration, R.H., R.G. and L.Á.Q.; funding acquisition, U.Y. and L.Á.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.A. holds a predoctoral contract funded by the Fundacion Caixa Rural Tomas Notario Vacas (2024 call). U.Y. holds a postdoctoral contract funded by the Xunta de Galicia (Ref. ED481_033/2024). A.A. holds a predoctoral contract funded by the Xunta de Galicia (Ref. ED481A-2025-031).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC) considers that this type of project does not fall under the legislation for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, national decree-law RD53/2013 (2010/63/EU Directive). The USC Ethics Committee considers that this type of project has no impact on animal welfare; this practice falls into the exceptions referred to in Article 2 (5.f) of the mentioned legislation. Consequently, this project can be exempted from ethics review and does not require the approval of the USC Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be provided by the correspondence author under reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Seragro’s hoof trimmers for the facilities, and assistance provided for the development of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Román González works for the Prolesa SAT dairy farm. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in any aspect of this publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DIM | Days In Milk. |

| MY | Milk Yield. |

| IRT | Infrared Thermography. |

| CR | Cranial. |

| CD | Caudal. |

| LS | Locomotion Score. |

| GLM | General Linear Model. |

References

- Ózsvári, L. Economic Cost of Lameness in Dairy Cattle Herds. J. Dairy Vet. Anim. Res. 2017, 6, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.C.; Green, M.J.; Huxley, J.N. Association between Milk Yield and Serial Locomotion Score Assessments in UK Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 4045–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foditsch, C.; Oikonomou, G.; Machado, V.S.; Bicalho, M.L.; Ganda, E.K.; Lima, S.F.; Rossi, R.; Ribeiro, B.L.; Kussler, A.; Bicalho, R.C. Lameness Prevalence and Risk Factors in Large Dairy Farms in Upstate New York. Model Development for the Prediction of Claw Horn Disruption Lesions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsousis, G.; Boscos, C.; Praxitelous, A. The Negative Impact of Lameness on Dairy Cow Reproduction. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2022, 57, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, L.; Barkema, H.W.; Pajor, E.A.; Mason, S.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Zaffino Heyerhoff, J.C.; Nash, C.G.R.; Haley, D.B.; Vasseur, E.; Pellerin, D.; et al. Prevalence of Lameness and Associated Risk Factors in Canadian Holstein-Friesian Cows Housed in Freestall Barns. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6978–6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Temmerman, P.-J.; Davy, W.; Maryns, D.; Van Nuffel, A.; Opsomer, G.; Maselyne, J.; Cool, S.; Van Weyenberg, S. Thermal Imaging for Foot Health Classification of Dairy Cattle. Precis. Livest. Farming 2024, 11, 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- LokeshBabu, D.S.; Jeyakumar, S.; Vasant, P.J.; Sathiyabarathi, M.; Manimaran, A.; Kumaresan, A.; Pushpadass, H.A.; Sivaram, M.; Ramesha, K.; Kataktalware, M.A.; et al. Monitoring Foot Surface Temperature Using Infrared Thermal Imaging for Assessment of Hoof Health Status in Cattle: A Review. J. Therm. Biol. 2018, 78, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, J.F.; Østergaard, S. Economic Decision Making on Prevention and Control of Clinical Lameness in Danish Dairy Herds. Livest. Sci. 2006, 102, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, K.A.; Whay, H.R.; Maggs, C.M.; Barker, Z.E.; Paul, E.S.; Bell, A.K.; Main, D.C.J. Working towards a Reduction in Cattle Lameness: 1. Understanding Barriers to Lameness Control on Dairy Farms. Res. Vet. Sci. 2010, 89, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Muñoz, A.; Singh, N.; Leonardi, C.; Silva-del-Río, N. Effect of Hoof Trimmer Intervention in Moderately Lame Cows on Lameness Progression and Milk Yield. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 9205–9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaaod, M.; Syring, C.; Dietrich, J.; Doherr, M.G.; Gujan, T.; Steiner, A. A Field Trial of Infrared Thermography as a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tool for Early Detection of Digital Dermatitis in Dairy Cows. Vet. J. 2014, 199, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, K.A.; Tisdall, D.A.; Bell, N.J.; Main, D.C.J.; Green, L.E. The Effects of Early Treatment for Hindlimb Lameness in Dairy Cows on Four Commercial UK Farms. Vet. J. 2012, 193, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, J.E.; Leach, K.A.; Main, D.C.J.; Whay, H.R. An Investigation into the Use of Infrared Thermography (IRT) as a Rapid Diagnostic Tool for Foot Lesions in Dairy Cattle. Vet. J. 2012, 193, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapinal, N.; de Passillé, A.M.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Rushen, J. Using Gait Score, Walking Speed, and Lying Behavior to Detect Hoof Lesions in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 4365–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whay, H. Locomotion Scoring and Lameness Detection in Diary Cattle. In Pract. 2002, 24, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlageter-Tello, A.; Bokkers, E.A.M.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G.; Van Hertem, T.; Viazzi, S.; Romanini, C.E.B.; Halachmi, I.; Bahr, C.; Berckmans, D.; Lokhorst, K. Effect of Merging Levels of Locomotion Scores for Dairy Cows on Intra- and Interrater Reliability and Agreement. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 5533–5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offinger, J.; Herdtweck, S.; Rizk, A.; Starke, A.; Heppelmann, M.; Meyer, H.; Janßen, S.; Beyerbach, M.; Rehage, J. Postoperative Analgesic Efficacy of Meloxicam in Lame Dairy Cows Undergoing Resection of the Distal Interphalangeal Joint. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaaod, M.; Fadul, M.; Steiner, A. Automatic Lameness Detection in Cattle. Vet. J. 2019, 246, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.R.; Olivares, F.J.; Descouvieres, P.T.; Werner, M.P.; Tadich, N.A.; Bustamante, H.A. Thermographic Assessment of Hoof Temperature in Dairy Cows with Different Mobility Scores. Livest. Sci. 2016, 184, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, H.W.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Kastelic, J.P.; Lam, T.J.G.M.; Luby, C.; Roy, J.P.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Keefe, G.P.; Kelton, D.F. Invited Review: Changes in the Dairy Industry Affecting Dairy Cattle Health and Welfare. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 7426–7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espejo, L.A.; Endres, M.I.; Salfer, J.A. Prevalence of Lameness in High-Producing Holstein Cows Housed in Freestall Barns in Minnesota. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3052–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opheim, T.S.; Sarturi, J.O.; Rodrigues, B.M.; Nightingale, K.K.; Brashears, M.; Reis, B.Q.; Ballou, M.A.; Miller, M.; Casas, D.E. Effects of a Novel Direct-Fed Microbial on Growth Performance, Carcass Characteristics, Nutrient Digestibility, and Ruminal Morphology of Beef Feedlot Steers. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaaod, M.; Büscher, W. Detection of Hoof Lesions Using Digital Infrared Thermography in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Bridge, G.; Young, L.; Handel, I.; Farish, M.; Mason, C.; Mitchell, M.A.; Haskell, M.J. The Use of Infrared Thermography for Detecting Digital Dermatitis in Dairy Cattle: What Is the Best Measure of Temperature and Foot Location to Use? Vet. J. 2018, 237, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giloh, M.; Shinder, D.; Yahav, S. Skin Surface Temperature of Broiler Chickens Is Correlated to Body Core Temperature and Is Indicative of Their Thermoregulatory Status. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Wang, D.; Titto, C.G.; Gómez-Prado, J.; Carvajal-De la Fuente, V.; Ghezzi, M.; Boscato-Funes, L.; Barrios-García, H.; Torres-Bernal, F.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; et al. Pathophysiology of Fever and Application of Infrared Thermography (Irt) in the Detection of Sick Domestic Animals: Recent Advances. Animals 2021, 11, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; Webster, J.R.; Schaefer, A.L.; Cook, N.J.; Scott, S.L. Infrared Thermography as a Non-Invasive Tool to Study Animal Welfare. Anim. Welf. 2005, 14, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanholi, Y.R.; Lim, M.; Macdonald, A.; Smith, B.A.; Goldhawk, C.; Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K.; Miller, S.P. Technological, Environmental and Biological Factors: Referent Variance Values for Infrared Imaging of the Bovine. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, A.L.; Cook, N.; Tessaro, S.V.; Deregt, D.; Desroches, G.; Dubeski, P.L.; Tong, A.K.W.; Godson, D.L. Early Detection and Prediction of Infection Using Infrared Thermography. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 84, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, S.L.; Bhakat, M.; Mohanty, T.K.; Chaturvedi, K.K.; Kumar, R.R.; Gupta, A.; Kumar, S. Udder Thermogram-Based Deep Learning Approach for Mastitis Detection in Murrah Buffaloes. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korelidou, V.; Simitzis, P.; Massouras, T.; Gelasakis, A.I. Infrared Thermography as a Diagnostic Tool for the Assessment of Mastitis in Dairy Ruminants. Animals 2024, 14, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, A.L.; Cook, N.J.; Church, J.S.; Basarab, J.; Perry, B.; Miller, C.; Tong, A.K.W. The Use of Infrared Thermography as an Early Indicator of Bovine Respiratory Disease Complex in Calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 2007, 83, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolari, S.C. Investigation of Skin Temperature Differentials in Relation to Estrus and Ovulation in Sows Using a Therman Infrared Scanning Technique. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vicentini, R.R.; Montanholi, Y.R.; Veroneze, R.; Oliveira, A.P.; Lima, M.L.P.; Ujita, A.; El Faro, L. Infrared Thermography Reveals Surface Body Temperature Changes during Proestrus and Estrus Reproductive Phases in Gyr Heifers (Bos taurus Indicus). J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 92, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwar, M.K.; Kataktalware, M.A.; Ramesha, K.P.; Pushpadass, H.A.; Jeyakumar, S.; Revanasiddu, D.; Kour, R.J.; Nath, S.; Nagaleekar, A.K.; Nazar, S. Influence of Season, Age and Management on Scrotal Thermal Profile in Murrah Bulls Using Scrotal Infrared Digital Thermography. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 2119–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Verkerk, G.A.; Stafford, K.J.; Schaefer, A.L.; Webster, J.R. Noninvasive Assessment of Autonomic Activity for Evaluation of Pain in Calves, Using Surgical Castration as a Model. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 3602–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.J.; Kennedy, A.D.; Scott, S.L.; Kyle, B.L.; Schaefer, A.L. Daily Variation in the Udder Surface Temperature of Dairy Cows Measured by Infrared Thermography: Potential for Mastitis Detection. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 83, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, M.J.; Dyson, S. Talking the Temperature of Equine Thermography. Vet. J. 2001, 162, 166–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; Lin, Y.; Knowles, T.G.; Main, D.C.J. Infrared Thermometry for Lesion Monitoring in Cattle Lameness. Vet. Rec. 2015, 176, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werema, C.W.; Laven, L.J.; Mueller, K.R.; Laven, R.A. Assessing Alternatives to Locomotion Scoring for Detecting Lameness in Dairy Cattle in Tanzania: Infrared Thermography. Animals 2023, 13, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, D.J.; Hostetler’, D.E.; Kaneene, J.B. A lameness scoring system that uses posture and gait to predict dairy cattle reproductive performance. Theriogenology 1997, 6, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainwater-Lovett, K.; Pacheco, J.M.; Packer, C.; Rodriguez, L.L. Detection of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus Infected Cattle Using Infrared Thermography. Vet. J. 2009, 180, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.C.; Mullan, S.; Main, D.C.J. Optimising Lameness Detection in Dairy Cattle by Using Handheld Infrared Thermometers. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018, 4, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanholi, Y.R.; Odongo, N.E.; Swanson, K.C.; Schenkel, F.S.; McBride, B.W.; Miller, S.P. Application of Infrared Thermography as an Indicator of Heat and Methane Production and Its Use in the Study of Skin Temperature in Response to Physiological Events in Dairy Cattle (Bos taurus). J. Therm. Biol. 2008, 33, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, A.; Plaizier, J.C.; Einarson, M.S.; Berry, R.J.; Scott, S.L.; Kennedy, A.D. Short Communication: Infrared Thermography and Visual Examination of Hooves of Dairy Cows in Two Stages of Lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2749–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, W.C. Nutritional Approaches to Minimize Subacute Ruminal Acidosis and Laminitis in Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, E13–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, J.; McNeill, D.M.; Phillips, C.J.C. Measuring Emotions in Dairy Cows: Relationships between Infrared Temperature of Key Body Parts, Lateralised Behaviour and Milk Production. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 269, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, A.L.; Muns, R.; Wang, D.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. Assessment of Pain and Inflammation in Domestic Animals Using Infrared Thermography: A Narrative Review. Animals 2023, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, S.; Thomson, P.C.; Kerrisk, K.L.; Clark, C.E.F.; Celi, P. Evaluation of Infrared Thermography Body Temperature and Collar-Mounted Accelerometer and Acoustic Technology for Predicting Time of Ovulation of Cows in a Pasture-Based System. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobić, T.; Mijić, P.; Gantner, V.; Glavaš, H.; Gregić, M. The Effects of Parity and Stage of Lactation on Hoof Temperature of Dairy Cows Using a Thermovision Camera. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2018, 19, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchli, C.; Raselli, A.; Bruckmaier, R.; Hillmann, E. Contact with Cows during the Young Age Increases Social Competence and Lowers the Cardiac Stress Reaction in Dairy Calves. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 187, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, N.; Onyango, J.; Mccormick, W. Digital Infrared Thermal Imaging and Manual Lameness Scoring as a Means for Lameness Detection in Cattle. Vet. Clin. Sci. 2014, 2, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, S.K.; Fuller, A.; Mitchell, D. Climate Change: Is the Dark Soay Sheep Endangered? Biol. Lett. 2009, 5, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughing, C.A.; Marino, D.J. Evaluation of Thermographic imaging of the Limbs of Healthy Dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 68, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Alvarado, A.; Ogi, A.; Villanueva-García, D.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Hernández-Avalos, I.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Mora-Medina, P.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. Application of Infrared Thermography in the Rehabilitation of Patients in Veterinary Medicine. Animals 2024, 14, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.