Abstract

This study explores the potential of hyperspectral imaging combined with machine learning techniques to provide accurate and non-invasive methods for analyzing soil nutrient content in precision agriculture. Data were collected from agricultural regions in Tamil Nadu, India, using conventional soil sampling methods that are labor-intensive and time-consuming. In contrast, hyperspectral imaging preserves soil integrity and enables rapid, remote assessment of soil health. The red fox optimization (FOX) algorithm was employed for spectral band selection, effectively reducing data redundancy while retaining the informative features. The partial least squares regression (PLSR) model achieved high prediction accuracy for organic carbon, with , a mean absolute error (MAE) of 16.4, and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 20.1, whereas for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, the corresponding values all exceeded 0.89. These results confirm the robustness and computational efficiency of the FOX-optimized models and demonstrate that integrating hyperspectral imaging with optimized machine learning can enable accurate, real-time soil nutrient estimation without destructive sampling, thereby supporting sustainable soil monitoring and protection in large-scale precision agriculture.

1. Introduction

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is a powerful tool for precision agriculture that utilizes sensors to capture images across numerous narrow spectral bands. Each organic component of soil interacts differently with specific wavelengths, providing detailed insights into soil composition and health. Under changing climatic conditions, accurately assessing soil nutrient content remains a major challenge, particularly in regions where maintaining food security is critical. Hyperspectral imaging supports the early detection of nutrient deficiencies, pests, and diseases, enabling precise nutrient management and crop classification, thereby enhancing agricultural efficiency and yield. However, conventional soil analysis methods, although accurate, are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and expensive. These methods require physical sampling, transportation, and laboratory testing, which limit their scalability and may degrade sample quality. Traditional reflectance measurements produce datasets representing organic and nutrient compositions; however, extracting meaningful information from these high-dimensional datasets requires advanced analytical models.

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches have increasingly been adopted to identify the spectral bands most relevant for predicting soil organic carbon (SOC) and other nutrients. Optimization techniques such as the genetic algorithm (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and ant colony optimization (ACO) have been applied to band selection. Although effective to some extent, these algorithms often suffer from redundant feature selection, slow convergence, and reduced stability when applied to large hyperspectral datasets. These limitations emphasize the need for more adaptive and computationally efficient optimization strategies. To address these challenges, this study employs the FOX algorithm, a recent nature-inspired metaheuristic designed to balance exploration and exploitation more effectively. FOX enhances feature selection by minimizing redundancy, improving convergence stability, and achieving higher predictive accuracy in complex spectral environments. By integrating FOX with regression models such as partial least squares regression (PLSR), random forest (RF), and gradient boosting (XGBoost), this study aims to improve the reliability and efficiency of soil nutrient estimation. The main objectives of this study are as follows:

- Implement the FOX algorithm to select the most relevant hyperspectral bands for soil nutrient estimation.

- Utilize PRISMA satellite hyperspectral imagery to evaluate the feasibility of large-scale soil nutrient mapping.

- Compare FOX with traditional optimization algorithms (GA, ACO, PSO) to demonstrate its efficiency in feature selection and predictive performance.

2. Related Works

Spectroscopic measurements and imaging of soil color have been used for field-scale estimation of soil organic carbon. The study used a digital camera and Sentinel-2 remote-sensing data to estimate soil organic carbon content through soil color analysis [1]. Random forest and advanced feature selection algorithms were used to optimize prediction models. The advantages of this approach include better extraction of spectral information, improved accuracy, and the potential for quantitative estimation. However, the drawbacks of this method include discrete sampling, point-to-point data collection, and the influence of external factors on the robustness of the model. The study used a combination of efficient signal preprocessing and an optimal band-combination algorithm, based on 233 soil samples and nine spectral preprocessing methods, to predict soil organic matter (SOM) through the visible and near-infrared spectra and improve prediction accuracy [2].

The Savitzky–Golay filter was found to be the most effective. However, this approach has limitations, including challenges in accurately representing complex soil compositions, sensitivity to environmental conditions, and restricted applicability to specific soil types and regions. Hyperspectral imaging, integrated with multivariate analysis and variable selection, has been investigated for its potential in the high-resolution mapping of soil carbon fractions within intact paddy soil profiles. In one such study, HSI was used to map soil carbon fractions in these profiles [3]. The authors compared linear and nonlinear multivariate techniques and applied a spectral variable-selection technique known as competitive adaptive reweighted sampling (CARS) to simplify models by selecting the most relevant variables.

The accuracy and robustness of the CARS-SVMR model may require validation in other regions. The primary objective of this study was to enhance processing speed and efficiency for hyperspectral imaging (HSI) applications. Field and imaging spectroscopy techniques have been evaluated to improve the estimation of soil organic carbon (SOC) and soil nitrogen (SN) under laboratory conditions [4]. One study assessed the performance of two hyperspectral sensors, the SVC HR-1024i field radiometer (FS) and the Specim IQ imaging spectrometer (IS), using 157 soil samples collected from the Taita Hills, Kenya. The results showed better predictive accuracy in the full-wavelength and shortwave-infrared (SWIR) regions, suggesting that the FS was best for SOC and SN estimation when the SWIR region was included. The present study aims to support regenerative agriculture initiatives by developing soil organic content prediction models based on discrete wavelet analysis of hyperspectral satellite data. The thesis introduces a noise-removal method for satellite-based hyperspectral soil data, utilizing the discrete wavelet transform to reconstruct both the original and first-derivative reflectance [5]. See ‘Exploring Appropriate Preprocessing Techniques for Hyperspectral Soil Organic Matter Content Estimation in the Black Soil Area’ [6]. However, potential drawbacks include complexities and sensitivity to specific parameter settings. Another study aimed to improve SOM estimation efficiency [7]. Another study explored the use of hyperspectral data to estimate soil nutrient content in order to monitor soil status and support sustainable agricultural development [8]. Techniques such as PLSR, PCC, LASSO, and GBDT have been used to find the optimal screening algorithm to estimate total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and total potassium content in soil. Linear and nonlinear machine learning techniques have also been employed [9]. Airborne hyperspectral imaging data were used to identify the spatial variability of soil nitrogen content, which is essential for agricultural development. This study focused on two areas in the Czech Republic, using laboratory and handheld spectrometers to assess soil nitrogen while excluding other nutrients such as potassium, phosphorus, and carbon. Incorporating advanced geomorphic features and algorithms significantly improves the accuracy and transferability of regional-scale hyperspectral prediction models of soil organic carbon (SOC). Techniques such as fractional-order derivatives, robust denoising methods, and preprocessed mid-infrared spectroscopy have proven effective in improving the prediction of SOC content [10]. These models use spectral reflectance data, derived features, and pretrained weights to improve accuracy and overcome challenges associated with mapping soil organic carbon (SOC) stock using hyperspectral and time-series multispectral remote sensing images in low-relief agricultural areas. This is crucial for effective land management. Agricultural land contributes significantly to global soil carbon storage, supporting crop growth and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Hyperspectral and multispectral images have been used for digital soil mapping, with PLSR and ELM models used to predict soil organic carbon stock and properties [11].

Recent studies have focused on improving the accuracy of soil organic carbon content prediction based on visible and near-infrared (Vis–NIR) spectroscopy and machine learning. Vis–NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy is a rapid and nondestructive method for estimating soil organic matter distribution and properties. It saves time and reduces the costs of collecting soil sample data. Various calibration methods, including partial least squares regression, support vector machines (SVMs), and artificial neural networks (ANNs), have been used to predict SOC content. A study in southern Hangzhou Bay, Zhejiang Province, China, compared the performance of different calibration methods and preprocessing approaches for SOC estimation. SVM regression combined with the first derivatives of the reflectance provided the best prediction results. Hyperspectral technology, particularly VIS-NIR-IR hyperspectral technology, has emerged as a rapid, accurate, economical, and nondestructive method for soil analyses. Principal component analysis combined with deep learning techniques was used to enhance data quality and model robustness, and these methods were applied to soil samples obtained from the Eastern Junggar coalfield in China. The results showed improved TabNet and CNN regression predictions, demonstrating the effectiveness of NIR hyperspectral imaging for identifying heavy metal pollution. However, the limited sample size may restrict generalizability. Soil organic matter content has been estimated using selected spectral subsets of hyperspectral data. Loss-on-ignition (LOI) is a reliable method for determining soil organic carbon (SOC) content in soil samples. The findings indicate that using informative spectral subsets offers a promising approach to estimating soil organic carbon (SOC) content [12]. Additionally, leveraging hyperspectral reflectance data from soil libraries combined with machine learning techniques demonstrates the potential of airborne and spaceborne optical soil sensing for accurate SOC predictions. The study uses a public soil spectral library and machine learning algorithms to predict soil organic carbon (SOC) concentrations. The prediction models used were: partial least squares regression (PLSR), random forest (RF), and convolutional neural network (CNN). The Fast Line-of-Sight Atmospheric Analysis of Spectral Hypercubes (FLAASH) module was employed for radiometric calibration and atmospheric correction. Another study developed regional models for predicting soil organic carbon (SOC) using multivariate analysis of mid-infrared hyperspectral data collected from the Indo-Gangetic plains of India. Preprocessing techniques were applied to enhance the spectral data and improve the accuracy of SOC predictions. Four multivariate methods were used to develop predictive models, with higher RPD values indicating better performance. MIR spectroscopy is quick, accurate, and consistent across different laboratories [13]. This integrated approach enhances the reliability of SOC predictions by generating more accurate and detailed spatial maps [14]. Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) captures spectral and spatial data to estimate soil properties. Traditional methods such as thermogravimetric analysis and loss-on-ignition are also discussed. However, the requirement for high-quality hyperspectral data may limit the applicability of these methods [15]. Machine learning models were used to predict SOC. SOC predictions were validated against ground-truth samples using metrics such as and RMSE. This method reduces the need for field sampling, shows strong prediction accuracy, and can be applied across different regions and soil types in the future.

The advantage of the FOX algorithm over other optimization algorithms, such as the genetic algorithm (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and ant colony optimization (ACO), when applied to hyperspectral band selection, lies in its faster convergence rate. Unlike FOX, the other algorithms are sensitive to parameter tuning and tend to converge to local optima. Although the GA provides good global search capability, it is computationally expensive. In comparison, PSO converges faster but loses diversity in later iterations. ACO is slower and less efficient for high-dimensional data and is best suited for discrete problems. FOX can tackle these issues by providing an optimal balance between exploration and exploitation by randomizing its target, which can be either global or local search. This ability to dynamically adapt the search behavior reduces the risk of being trapped in local minima, thereby improving diversity in the search space. Additionally, FOX requires fewer parameters to tune. The FOX algorithm is relatively new and must be tested in a broader sense across datasets to confirm its consistency. Overall, FOX is a more stable and efficient alternative for hyperspectral band selection.

3. Methodology

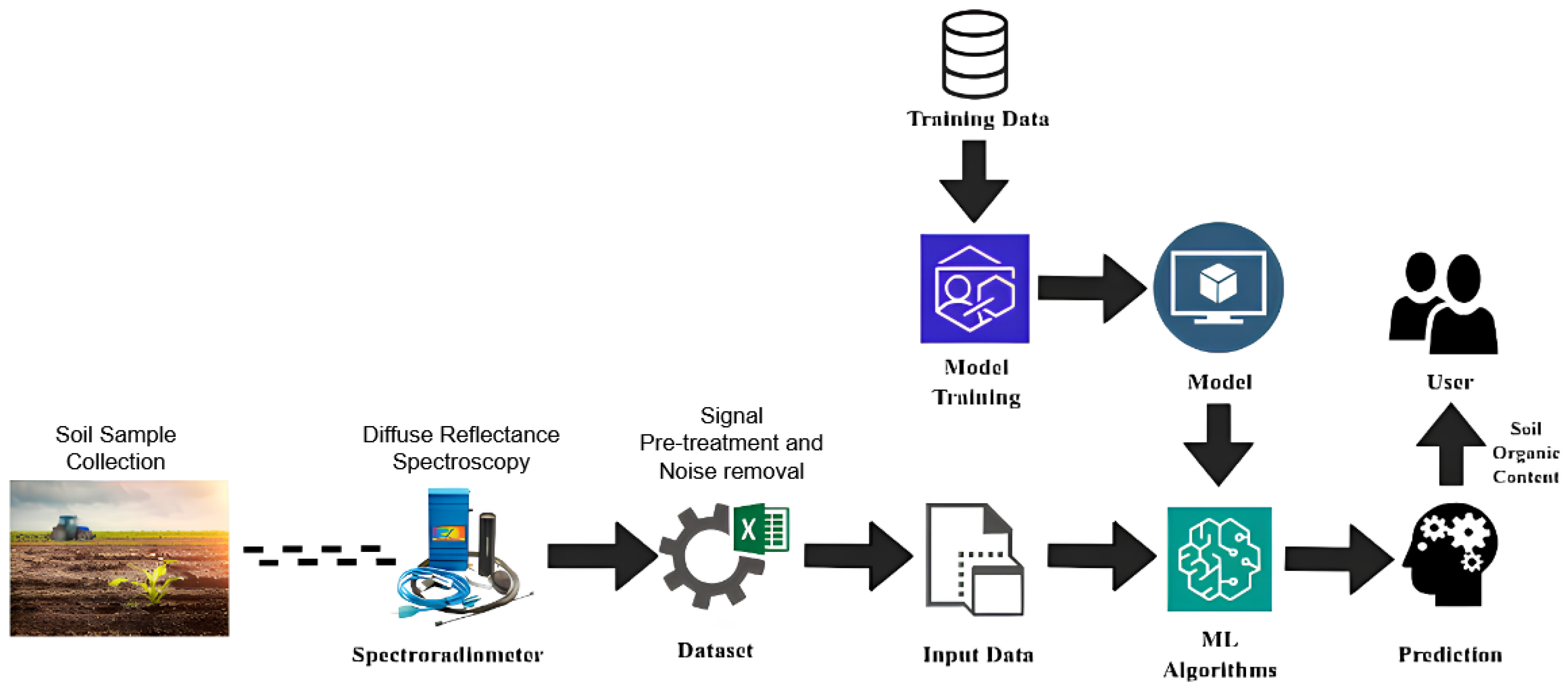

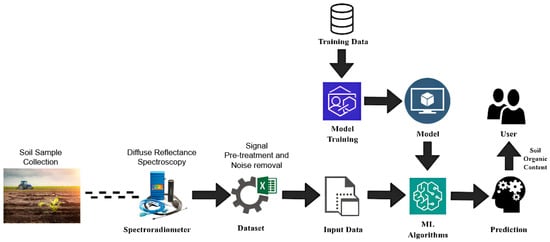

The workflow starts with the preparation of soil-sample data using an in-field hyperspectral spectroradiometer. The ground-truth soil samples used in this study were obtained from agricultural fields in Radhapuram, Tirunelveli District, Tamil Nadu. The spectral reflectance data were recorded over the wavelength range 350–2500 nm, covering the visible, near-infrared (VNIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) regions, as shown in Figure 1. The initial step involved collecting soil samples from agricultural fields. The trained models were then validated and used to predict soil organic content in new samples. The built model provides sufficient information for farmers to plan and improve their agricultural yield. Multiple models were developed to conduct a comparative study and determine the most efficient model. In summary, the proposed framework represents a systematic and data-driven approach for processing and evaluating hyperspectral information to develop reliable soil property prediction models, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed methodology.

3.1. Optimization Technique

FOX-Inspired Optimization Technique

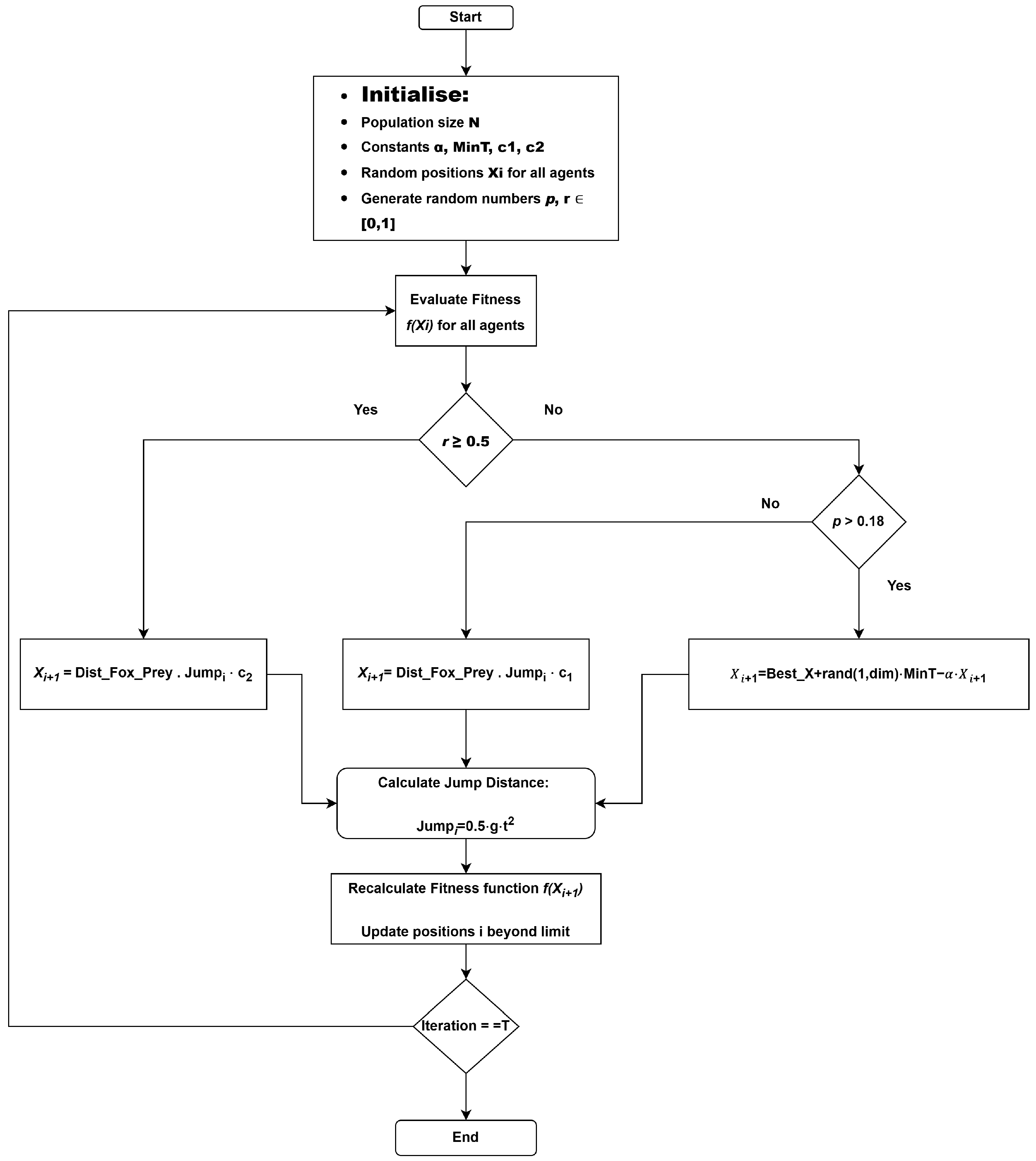

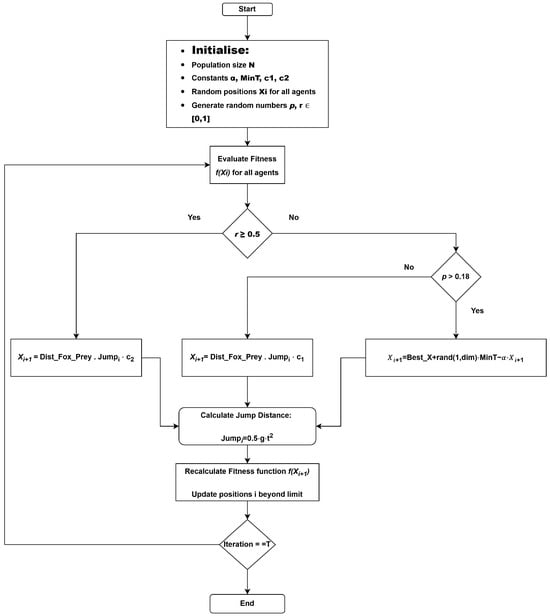

The red fox optimization (RFO) algorithm is a metaheuristic that imitates the hunting behavior of red foxes, which exhibit adaptive search strategies that provide an equal opportunity for both exploration (global search) and exploitation (local search). The flowchart illustrates the operation of the algorithm, in which the initial search population (foxes) is generated. The exploration and exploitation processes are controlled by a random variable r. If r <= 0.5, the algorithm operates in exploration mode, allowing the search agents to explore distant regions of the feature space to avoid being trapped in local minima. The FOX algorithm is inspired by the hunting behavior of red foxes and balances exploration and exploitation to find optimal or near-optimal solutions to complex problems. This algorithm effectively demonstrates the ability of the fox to locate its prey through two modes of operation, thereby finding an optimal or near-optimal solution, as shown in Algorithm 1. The FOX flowchart is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

FOX algorithm flow diagram.

The initialization of the population (here, the foxes) is entirely random, where each particle in the population is a potential solution to the objective function in the search space. They are spread across the search space to encourage diverse exploration. The optimization process continues over a series of iterations, during which the positions of the foxes are updated after each iteration. The process continues for a specified number of iterations or until the solution converges. The search is governed by a random variable r, as previously mentioned. This variable determines the search strategy. When : the algorithm performs exploration—foxes are encouraged to move to distant and unexplored regions of the search space. This prevents the foxes from finding the local minima at a very early stage of the search, as shown in Equation (1). Best_X is the best possible position found by any fox so far; rand(1, dim) is a random vector that controls movement diversity; MinT is the minimum threshold for movement; is the scaling factor that adjusts the magnitude of the movement.

| Algorithm 1 FOX algorithm for soil nutrient estimation. |

|

When : the algorithm performs exploitation. Once the fox has found a promising global solution, it attempts to refine the positions in promising areas of the search space, focusing on the regions around the prey. Exploitation is further divided into two subdivisions governed by the variable p. If (p < 0.18), or as shown below.

Distance between the fox and the prey, often calculated using the Euclidean distance. the fox’s jump represents magnitude, where g = 9.81 m/s2.

High randomness in early iterations causes a wider search and a higher probability for the model to detect the global best positions for the foxes to find their prey. As randomness is reduced in later iterations, the chances of convergence increase as the foxes search the local search space to find their prey, that is, the solution. This algorithm is preferred in this case study for its handling of exploration and exploitation probabilities, its adaptability in terms of its search intensity with respect to the best positions, and its robustness in terms of its performance on the dataset [16].

The FOX-inspired optimization technique employed in this study balances exploration and exploitation through adaptive parameter control, as shown in Table 1. The initial population size () ensures sufficient diversity among candidate solutions, whereas the number of iterations () provides adequate search depth without excessive computation. The exploration coefficient () controls the movement intensity of the fox agents, promoting efficient exploration in the early stages. The minimum temperature (MinT = 0.2) determines the lower limit of the temperature-based adaptation mechanism, helping the algorithm avoid premature convergence.

Table 1.

Parameter settings used for the FOX-inspired optimization technique.

3.2. Machine Learning Model

The selected features were used to train regression models to predict soil nutrient content. Various regression models were chosen for their ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships in the data, with the goal of building optimal predictors of soil nutrient concentrations [17]. PLSR is used to reduce the dimensionality of the dataset and to handle multicollinearity. Linear regression served as a baseline model, whereas LASSO regression reduced the risk of overfitting by adding L1 regularization for feature selection. Random forest (RF) was used to capture nonlinear relationships among the data. Finally, a hybrid PLSR-XGBoost model was developed, where PLSR handled the high dimensionality, thus allowing XGBoost to leverage both the linear structure and nonlinear flexibility. The use of various models allows for a comprehensive comparison to choose the best model for each nutrient.

3.2.1. Partial Least Squares Regression

PLSR is well-suited for hyperspectral data because of its ability to handle multicollinearity and high dimensionality. It reduces the predictors and the response variable to a lower-dimensional latent space that captures the maximum covariance [18]. Given a predictor matrix X and target vector y, the model is decomposed as follows:

Here, T is the latent variable (score), are loadings, and are residuals. The extracted components T are used to predict the value of y. In this context, PLSR maps selected hyperspectral bands to nutrient concentrations by extracting latent relationships from the data. It also serves as a preprocessor for hybrid models.

3.2.2. Linear Regression

Linear regression assumes a direct and additive relationship between spectral characteristics and target nutrient values [19]. This is mathematically represented as

Here, is the selected spectral band and is the regression coefficient. The model parameters were optimized by minimizing the sum of squared errors.

This linear model serves as a baseline for comparison and provides interpretable relationships between wavelengths and nutrient levels.

3.2.3. Lasso Regression

Lasso is a regularized version of linear regression that promotes sparsity in the model, making it ideal for high-dimensional data such as hyperspectral input [20]. It minimizes the following objective:

The regularization parameter controls the trade-off between the fit of the model and the sparsity. Lasso not only improves generalization by reducing overfitting, but also performs implicit feature selection by driving some values to zero.

3.2.4. Random Forest Regression

Random forest is a nonlinear ensemble learning method that builds multiple decision trees on random subsets of data and averages their results [21].

where is the prediction of the t-th decision tree. RF captures complex interactions between spectral bands and nutrient concentrations that linear models may miss.

The important parameters used include the number of trees (typically 100), maximum tree depth, and the number of features considered at each split. RF feature importance scores also provide insights into which wavelengths contribute the most to the predictions. It should be noted that out-of-bag (OOB) error estimation was not used in this study.

3.2.5. Hybrid Model: PLSR + XGBoost

To take advantage of both the linear structure and nonlinear flexibility, a hybrid pipeline combining PLSR and XGBoost was used [22]. XGBoost minimizes the regularized objective:

where is the individual tree, T denotes the number of leaves, and is the leaf weight. This formulation balances the prediction accuracy and model complexity.

Table 2 summarizes the hyperparameter settings used for all the machine learning and hybrid models. Linear regression was implemented using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method without any regularization. Lasso regression included an penalty with a regularization strength of and a maximum iteration count of 1000 to ensure convergence. The random forest (RF) model consisted of 100 trees with a maximum depth of 10 and a minimum of two samples per leaf, using the mean squared error criterion to minimize bias and variance [22,23,24,25]. For the partial least squares regression (PLSR) model, ten latent components were retained, and the input data were standardized to improve model stability and convergence with a tolerance of .

Table 2.

Hyperparameter settings for the machine learning and hybrid models.

3.3. Evaluation Parameters

3.3.1. Mean Squared Error

The root mean square error (RMSE) measures the square root of the average squared difference between the actual and predicted values, thereby penalizing larger deviations more heavily, as expressed in Equation (11) [26,27].

3.3.2. Root Mean Squared Error

The square root of MSE provides an error in the same units as the original data, as shown in Equation (12).

3.3.3. R-Squared Score

The coefficient of determination () indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables, with values ranging from 0 to 1, as defined in Equation (13).

3.3.4. Mean Absolute Error

The mean absolute error (MAE) is the average of the absolute differences between predicted and actual values, providing a simple yet effective measure of the model’s predictive accuracy, as indicated in Equation (14).

3.4. PRISMA

The Italian Space Agency’s PRISMA satellite, launched in 2019 by Spectra Vista Corporation, is equipped with a panchromatic camera and a hyperspectral imaging sensor. This setup allows for high-resolution spectral analysis across the 400–2500 nm range, encompassing the visible, near-infrared (VNIR), and short-wave infrared (SWIR) regions [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. It achieves a spectral resolution of 10 nm per band, a spectral width of 1.5 nm, and a ground sampling distance (GSD) of 30 m. The model employed was ‘GER 1500.’

PRISMA offers a large-scale, non-destructive approach to evaluating soil nutrients, which are crucial indicators of soil health and carbon sequestration [32]. Unlike traditional methods that require labor-intensive sampling, PRISMA identifies unique spectral properties of organic matter. By utilizing spectral indices and machine learning, researchers can map nutrient variations for climate studies, sustainable land management, and precision agriculture [33]. The high spectral granularity of PRISMA also aids in vegetation monitoring, mineral exploration, and environmental research, thereby enhancing soil management, productivity, and climate resilience.

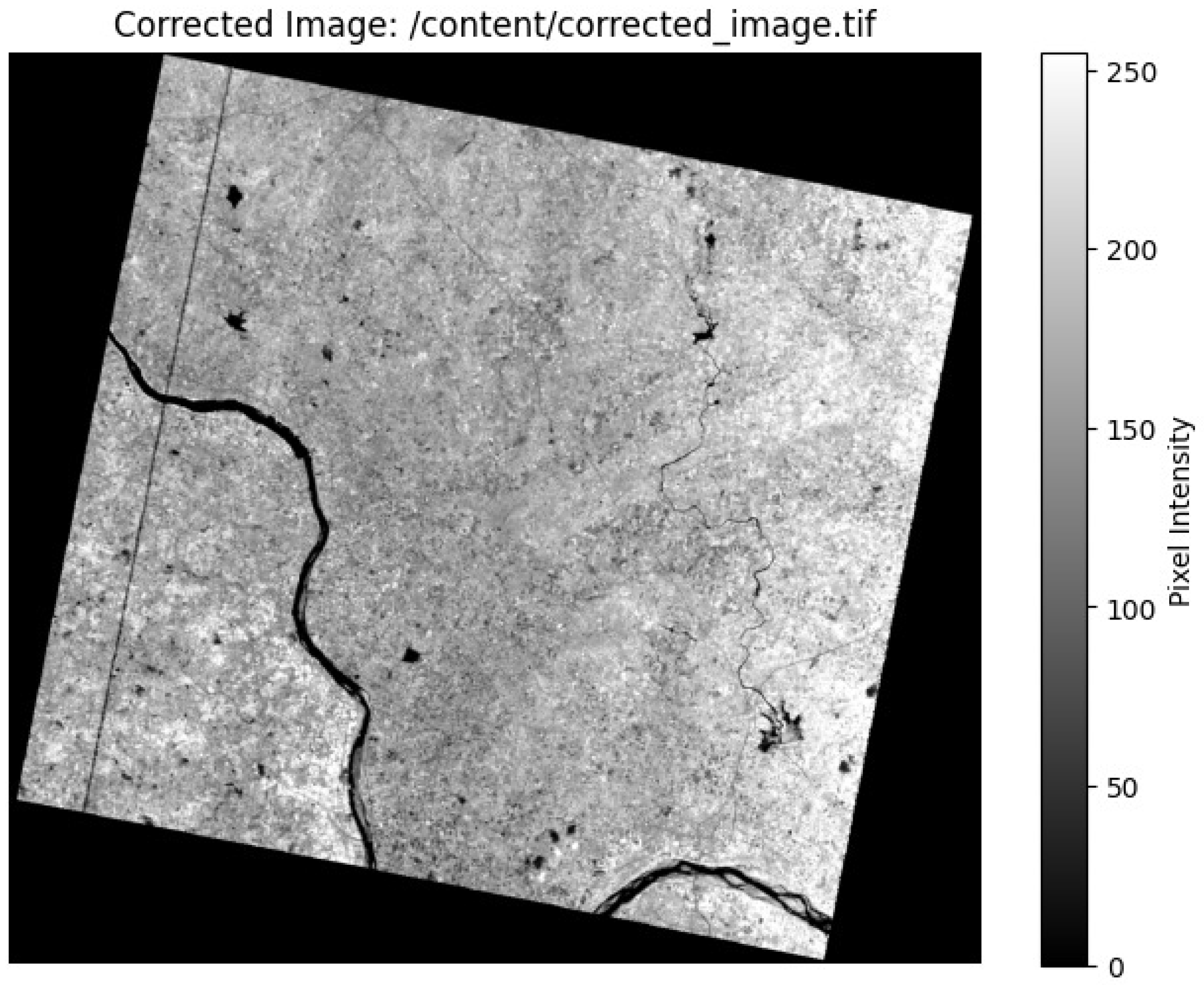

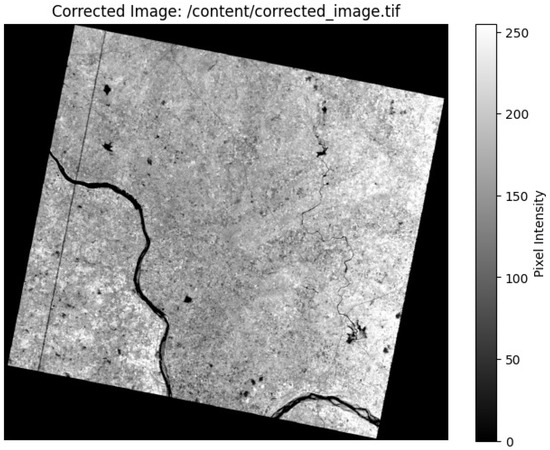

Spatial interpolation techniques were applied to refine the spectral information to further address mixed-pixel issues. The PRISMA-ASI satellite image shown here is displayed using Python 3.7. The pixel intensity values in the grayscale visualization range from 0 to 250. Higher reflectance occurs in brighter areas, whereas lower reflectance is observed in darker areas. Figure 3 depicts the geographical area of Radhapuram in the Tirunelveli District, showing variation in land cover and river characteristics [34].

Figure 3.

PRISMA-ASI satellite image viewed using Python 3.7.

Wavelength Mapping of a Hyperspectral Image in PRISMA

Table 3 shows the spectral range covered by PRISMA.

Table 3.

Wavelength mapping.

PRISMA is superior to DESIS, which lacks SWIR bands crucial for soil nutrient analysis. Unlike Hyperion, PRISMA provides a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and a wider 30 km swath, allowing large-scale soil mapping [35]. Compared to EnMAP, PRISMA has more flexible data access, as EnMAP prioritizes selected research requests [36] Furthermore, the free availability of PRISMA makes it more accessible than DESIS, which is commercial. With a 7-day revisit time, PRISMA is an excellent choice for soil nutrient monitoring, balancing the spectral, spatial, and operational advantages [37].

4. Results and Discussions

Based on the observations, the fox-inspired optimization (FOX) algorithm consistently achieved higher coefficients of determination () and lower error metrics than the other baseline optimization algorithms. The unique capability of the FOX algorithm to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation enables it to avoid premature convergence to local minima, thereby providing a more efficient and stable search process. Consequently, FOX is particularly well-suited for identifying relevant spectral bands within fewer iterations [38]. Although particle swarm optimization (PSO) and the genetic algorithm (GA) occasionally achieved comparable or slightly higher values, their convergence stability and sensitivity to parameter tuning were less reliable than those of FOX. In summary, the FOX algorithm provides the most effective trade-off among accuracy, computational efficiency, and stability, making it the most appropriate technique for spectral band selection before regression modeling [39].

After identifying the relevant bands using the FOX technique, it was observed that each regression model demonstrated distinct performance trends for different soil nutrients. The random forest (RF) model achieved the highest value of up to 0.74 for organic carbon under bat optimization (BO), while its corresponding performance under the FOX algorithm was approximately 0.40. The partial least squares regression (PLSR) model performed consistently poorly across all nutrient types and optimization methods, with values generally ranging between 0.3 and 0.4. However, the hybrid PLSR + XGBoost model achieved the best overall predictive accuracy, with values of 0.97 for organic carbon and 0.95 for phosphorus based on the PRISMA-derived data, outperforming all single-model approaches. These findings confirm that combining FOX-based band selection with ensemble or hybrid regression models significantly enhances the accuracy and robustness of soil nutrient prediction.

The soil nutrient levels, using the set criteria to classify their levels, are shown in Table 4. The four important nutrients (organic carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorus, potassium) are classified into three concentration levels (low, medium, and high), which are essential indicators of soil health and fertility and strongly affect crop growth and agricultural yield. For hyperspectral data analysis, this table serves as a reference for correlating spectral reflectance measurements with nutrient content. By identifying the spectral bands that are most sensitive to variations in nutrient levels in the samples, researchers can use hyperspectral imaging techniques to estimate and map soil nutrient content over large areas. Optimized and regressed spectral data can be used to predict whether a soil sample has low, medium, or high levels of each nutrient.

Table 4.

Soil nutrient levels for radiometer data.

In practice, these classifications support precision-agriculture methods, including site-specific fertilizer application and improved soil-management practices. The use of hyperspectral data for remotely sensing nutrient levels reduces the need for extensive soil samples and laboratory analyses, making farming operations more efficient, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly.

4.1. Datasets Description

The workflow of this study involves the use of hyperspectral imaging of the organic content of the soil with the help of the machine learning-based regression analysis shown in Figure 1. The initial step involves collecting soil samples from agricultural fields. In this study, soil samples were obtained from Radhapuram, located in the Tirunelveli district. These samples were used to acquire spectral data using a spectroradiometer. A total of 65 soil samples were collected from representative agricultural plots, ensuring variations in soil texture, moisture, and nutrient composition. The spectral signature of each sample was recorded over 1849 wavelengths ranging from 350 to 2500 nm, forming a 1849 × 65 dataset. The spectral data were compiled into a data set. To improve the accuracy of the prediction, feature selection was performed by choosing the relevant bands that contributed the most to the prediction of soil nutrient content. This step determined the most informative wavelength or range of wavelengths and the significance of using the wavelengths to predict the properties of the soil in question. The processed data were used to train machine learning regression models. Regression was used to determine the relationship between the chosen spectral bands and the soil properties under investigation. This included the formulation of prediction models based on the significant bands obtained above. These were supposed to predict soil properties through hyperspectral data. The trained models were then validated and used to predict the soil organic content of new samples. The built model helped provide sufficient information for farmers to plan and improve agricultural yield. Multiple models were developed to conduct a comparative study and determine the most efficient.

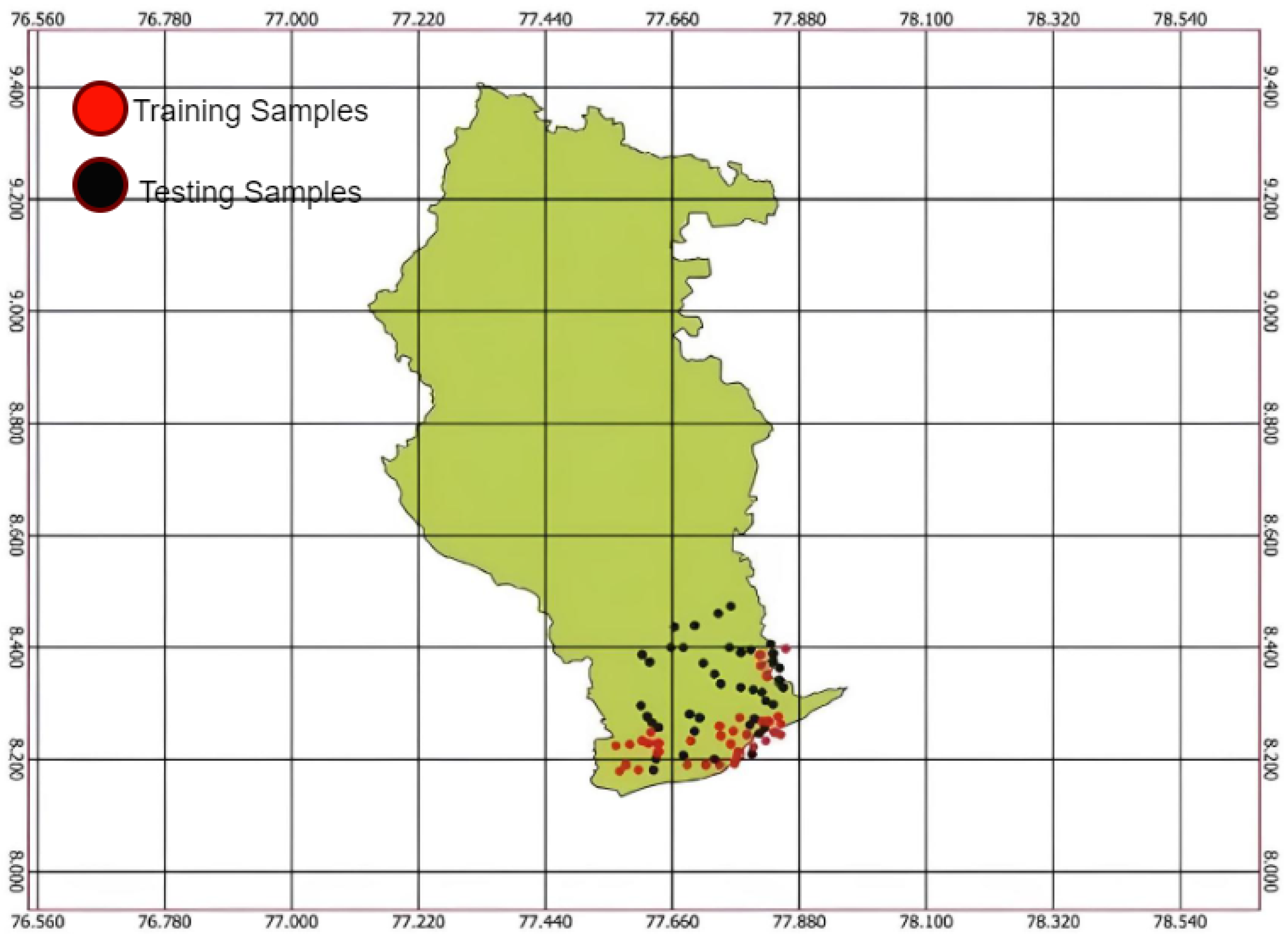

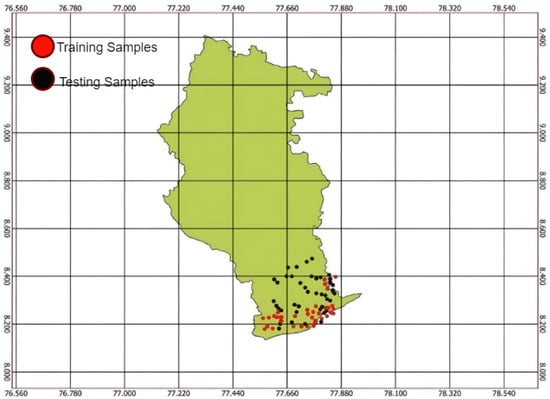

Figure 4 shows the hyperspectral radiometer data collected from Radhapuram in the Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu. Many small dots on the map mark specific locations where data were gathered. The dots were likely sampling points where the spectral properties of the soil were measured [16]. The x-axis of the graph is labeled as “wavelength,” ranging from 350 to 2500 nanometers, and the y-axis is labeled as “Spectral Reflectance,” ranging from 0 to 0.4, collected from the Figspec FS23 hyperspectral spectroradiometer data. The graph shows how different levels of soil nutrients, such as phosphorus, affect reflectance measured by the radiometer. Here, the red points are the training samples, and the black points are the testing samples.

Figure 4.

Hyperspectral radiometer dataset locations.

4.2. Accurate Calculation and Assessment of Soil Nutrient Concentrations at Soil Reflectance Sites

The independent variables in this study were the selected spectral parameters. The dependent variables were the soil nutrient parameters SOC, N, P, and K. PLSR was used to predict the SOC, N, P, and K contents of the soil. The coefficient of determination (), mean absolute error, and root mean square error were calculated between the predicted and actual concentrations. HSI measures the reflectance intensity across various wavelengths of light, and each nutrient interacts differently with specific wavelengths owing to its chemical bonds and functional groups. Naturally occurring organic carbon is present as functional groups such as and its variants, and the key bands of light that interact with these compounds are in the range of 1700 to 2200 nm. Nitrogen occurs in bonds in the soil, and the effectiveness of specific bands for its detection is due to the stretching and vibrations associated with proteins, amides, and amino compounds in the soil. Nitrogen does not have a strong direct absorption characteristic, but is correlated with soil organic carbon, and its absorption features often overlap with those of the SOC bands.

Similarly, phosphorus is bound to iron and aluminum oxides and to clay minerals and other organic matter, where potassium may also occur. Materials such as illite, mica, and feldspar contain potassium, and their reflectance features are primarily caused by bending vibrations of bonds in the compounds formed between potassium and other elements. In conclusion, the reflectance of hyperspectral light by soil nutrients arises from their presence in compounds rather than as isolated species. The bond angles and vibrational modes resulting from the transfer of energy at different wavelengths give a unique spectral characteristic to each nutrient.

The regression equations summarized in Table 5 represent the optimal spectral band combinations derived using the fox-inspired optimization (FOX) algorithm for predicting soil nutrients. Each equation corresponds to a specific nutrient concentration class (low, medium, or high) and combines the most informative wavelengths identified during the band selection process.

Table 5.

Regression equations for soil nutrient prediction using selected spectral bands.

4.3. Regression Results After Optimization

Five optimization techniques were used to find the best bands, and four regression types were used to evaluate the score, mean absolute error, and root mean square error.

Table 6 shows the results of organic carbon (OC) prediction using different optimization techniques. Evidently, the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm provides the best overall performance across all OC levels. For the OC Low group, the PSO–Linear model achieved the highest value of 0.7838 and the lowest RMSE of 0.096, indicating strong predictive accuracy. Similarly, for OC Medium and OC High, PSO maintained superior results, with values of 0.8091 and 0.7403, respectively. In comparison, FOX and ant colony optimization (ACO) showed lower values (below 0.31) and higher MAE, whereas bat optimization (BO) produced competitive but slightly less accurate predictions. The genetic algorithm (GA) performed the weakest, showing lower values and higher RMSE across all OC ranges.

Table 6.

Organic carbon results using different optimization techniques.

Table 7 presents the results for phosphorus (P) prediction. As shown in the table, bat optimization with the random forest model achieved the best results, particularly for medium and high P levels, where values of 0.5718 and 0.6549 were obtained, with low RMSE values of 6.5105 and 5.845, respectively. FOX and ACO achieved moderate accuracy, whereas PSO and GA demonstrated higher error values. This indicates that BO–RF is the most effective combination for estimating phosphorus.

Table 7.

Phosphorus results using different optimization techniques.

Table 8 presents the potassium (K) prediction results. As shown in the table, FOX provided the most reliable outcomes, particularly when combined with random forest. For K Medium, FOX–RF achieved = 0.6534 with the lowest RMSE (5.8576) and an MAE (34.31), outperforming all other optimization approaches. For K High, FOX–Linear also performed well, with = 0.4715, whereas PSO and BO showed high RMSE values, indicating poor prediction stability.

Table 8.

Potassium results using different optimization techniques.

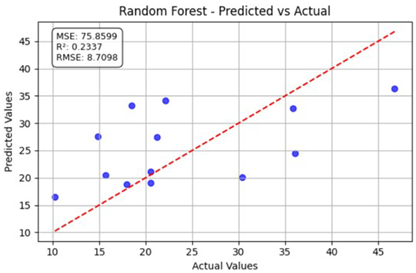

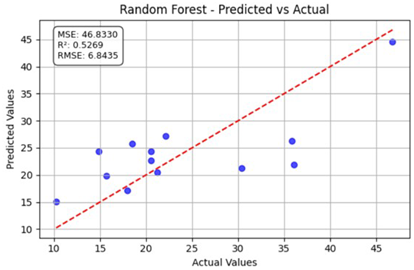

Table 9 shows the nitrogen (N) prediction performance using different optimization methods. The results indicate that ACO–RF yielded the best explained variance for low nitrogen levels ( = 0.5269, RMSE = 6.8435). Although the GA and BO combinations yielded lower MAE values (approximately 24–31), their values remained low, suggesting less consistency. For the second nitrogen dataset (N Low1), ACO again provided moderate accuracy, whereas the other algorithms showed high variability.

Table 9.

Nitrogen results using different optimization techniques.

Overall, the results presented in Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 demonstrate that PSO performs best for organic carbon estimation, BO excels for phosphorus, FOX shows greater stability for potassium, and ACO performs well for nitrogen. The genetic algorithm generally produces lower accuracy and higher error rates across all nutrient types.

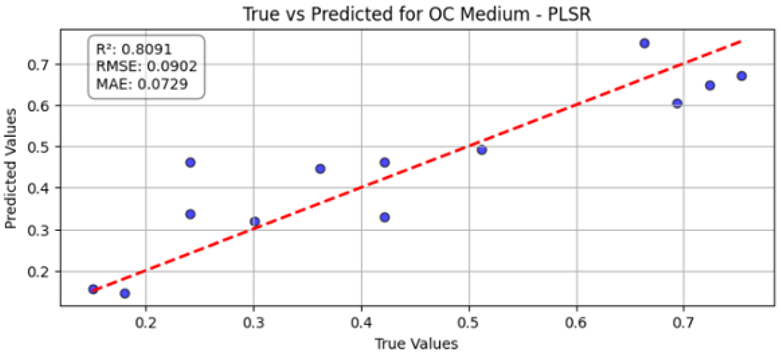

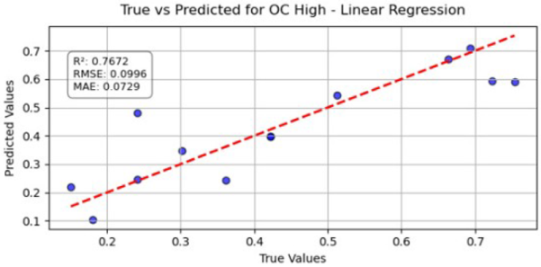

4.4. Regression Result Curves

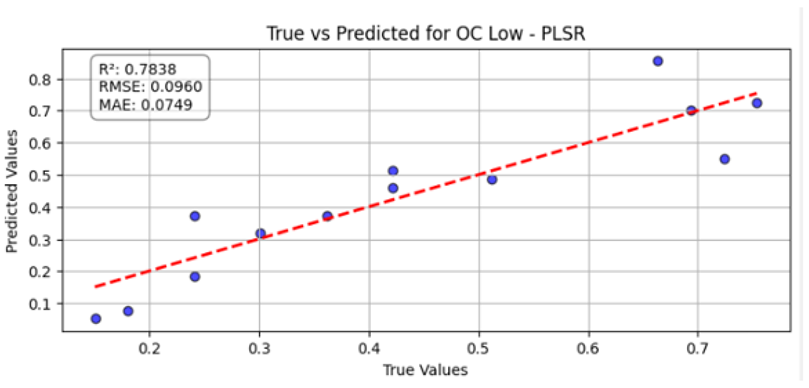

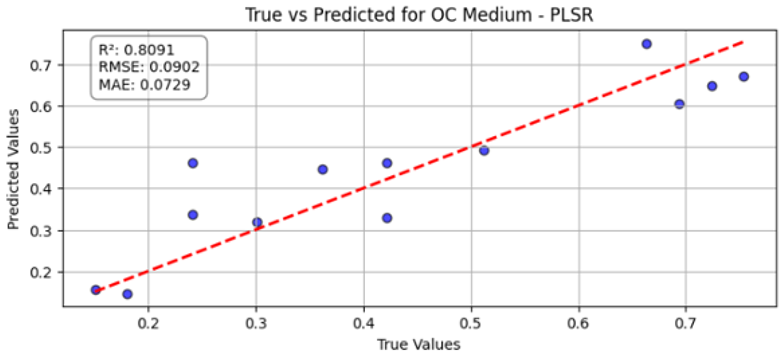

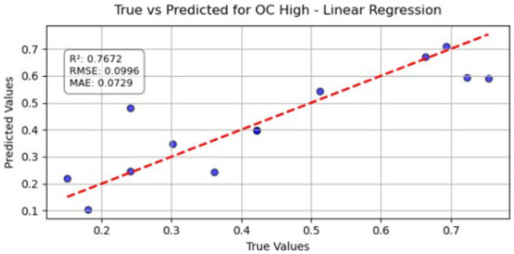

Table 10 illustrates the true versus predicted values for organic carbon (OC) at low, medium, and high concentration levels using different regression models for test samples as blue color. For the OC Low dataset, the partial least squares regression (PLSR) model attained an value of 0.7838, an RMSE of 0.0960, and an MAE of 0.0749, indicating a strong correlation between the predicted and true values. In the case of the OC Medium, the PLSR model achieved slightly better accuracy, with the highest value of 0.8091 and the lowest RMSE of 0.0902, confirming improved predictive performance at this concentration level. For OC High, the linear regression model recorded an of 0.7672, an RMSE of 0.0996, and an MAE of 0.0729, showing consistent and reliable predictions, although with slightly lower accuracy than the OC Medium dataset. Across all three datasets, the predicted values closely followed the red dashed 1:1 line, confirming that both PLSR and linear models provide robust prediction capabilities for organic carbon estimation. Overall, PLSR performed slightly better than linear regression, with the best predictive fit observed for the OC Medium dataset.

Table 10.

Organic carbon.

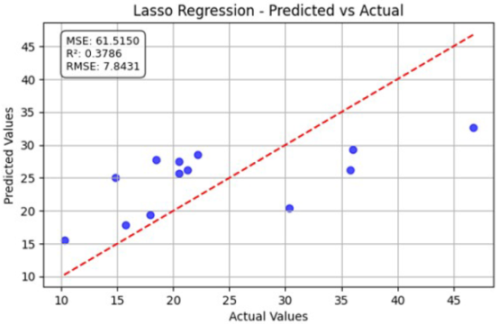

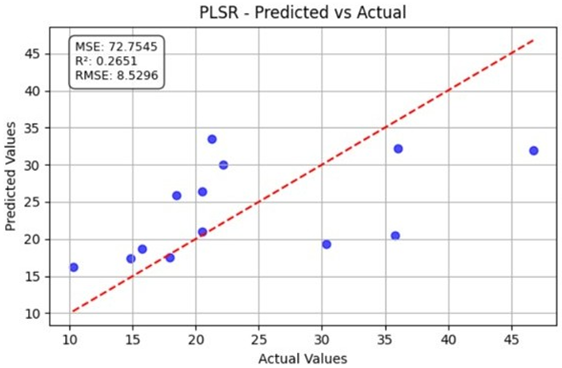

Table 11 shows the predicted versus actual phosphorus (P) values for low, medium, and high concentrations using different regression models. Here, the blue dots show the actual data points (true vs. predicted values), while the red line represents the model’s ideal linear fit showing the expected prediction trend. For the P Low dataset, the partial least squares regression (PLSR) model achieved an value of 0.3686, with an RMSE of 7.9057 and an MSE of 62.4998, indicating a moderate correlation between the predicted and actual phosphorus levels. For the medium datasets, the Laplace regression model applied to the P Medium dataset slightly improved the coefficient of determination to , with a lower RMSE of 7.8431, demonstrating slightly better prediction consistency. For the P High dataset, the PLSR model achieved the best performance among the three, with the highest value of 0.4185, an RMSE of 7.5869, and an MSE of 57.5612.

Table 11.

Phosphorus.

Table 12 shows the predicted versus actual values for the Nitrogen Low and Low1 datasets using the random forest model. Here, the blue dots show the actual data points (true vs. predicted values), while the red line represents the model’s ideal linear fit showing the expected prediction trend. The model achieved a coefficient of determination () of 0.2337, indicating that approximately 23% of the variance in the true nitrogen values was explained by the model. The root mean square error (RMSE) of 8.7098 and the mean squared error (MSE) of 75.8599 indicate a moderate prediction error. Although some data points align near the red dashed 1:1 line, a noticeable spread exists, implying that the model underestimates and overestimates specific values. Overall, the random forest model provided only limited predictive accuracy for the N Low dataset. For the Low1 dataset, the model achieved a higher value of 0.5269, indicating that approximately 52.7% of the variance in the observed data was captured by the model.

Table 12.

Nitrogen.

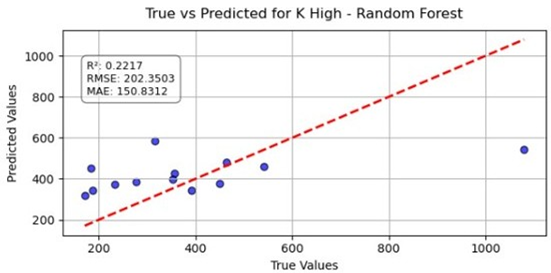

Table 13 shows the relationship between the true and predicted values for the potassium (K) high dataset using the random forest model. Here, the blue dots show the actual data points (true vs. predicted values), while the red line represents the model’s ideal linear fit showing the expected prediction trend. The coefficient of determination () was 0.2217, indicating that approximately 22% of the variance in the observed potassium values was explained by the model. The root mean square error (RMSE) value of 202.35 and the mean absolute error (MAE) of 150.83 suggest a high level of prediction error and bias in the model’s output.

Table 13.

Potassium.

4.5. Regression Results for PRISMA Data

For the PRISMA dataset, a hybrid regression model was used, combining PLSR and XGBoost, as shown in Table 14. The regression results from the PRISMA data indicate that the genetic algorithm (GA) delivered the highest prediction accuracy, with higher values and the lowest MSE across all soil nutrients. ACO and BO showed moderate performance, with BO performing particularly well for phosphorus. PSO showed similar trends but with slightly higher errors, especially for nitrogen and potassium. In contrast, FOA recorded the lowest accuracy, as reflected in its reduced values and higher MSE. Overall, GA emerged as the most effective optimization method for soil nutrient estimation using PRISMA hyperspectral imagery. A comparison of the PRISMA regression results shows that the genetic algorithm (GA) consistently outperformed all other methods, achieving the highest values (up to 0.9970) and the lowest MSE (as low as 0.0001). BO and ACO provided moderate accuracy, with BO reaching an of 0.9595 for phosphorus, whereas PSO performed similarly but with comparatively higher MSE values. FOA recorded the weakest performance, with lower values, such as 0.6531 for organic carbon and 0.5886 for nitrogen. These trends clearly indicate that GA offers the most reliable and precise soil nutrient estimation from PRISMA data.

Table 14.

Regression results for PRISMA data.

5. Conclusions

This study was motivated by the need to develop sustainable agricultural practices, particularly in the tropical agricultural regions of Tamil Nadu, India. Traditional soil analysis methods are accurate but often laborious and time-consuming, making them expensive. Soil sampling, transportation, and laboratory testing can degrade soil quality and prolong the collection period. Hyperspectral imagery solves this problem because remote sensing is achievable, thus maintaining soil quality while providing preliminary information on soil health. Hyperspectral imagery was taken and interpreted in a study to find nutrients in the soil, including organic carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. The hyperspectral imaging technique, as seen in the article above, has proven to be an effective method for precision agriculture in soil and crop analysis, and has applications in horticulture and food analysis. Its potential extends to the livestock sector, where animal health, welfare, and feed quality can also be analyzed with great accuracy. Additionally, natural resource management is a sector that benefits from HSI-based monitoring of wildlife in both terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Future Scope

Among the limitations of HSI, the acquisition of hypercubes is a major one. The capture of multiple images with different bands of light is time-consuming, delaying field deployment. To tackle this problem, future work must focus on developing multispectral imaging systems that only consider relevant bands for specific applications. By using only the most informative wavelength data, faster scanning can be achieved while maintaining analytical accuracy, making it a practical tool for real-time analysis.

Author Contributions

A.R. contributed to the conceptualization, original draft writing, and supervision. S.B. was responsible for investigation, data curation, and manuscript review and editing. N.K. performed formal analysis and validation and contributed to manuscript review and editing. P.S. handled software development, visualization, and manuscript review. R.S. contributed to data collection, resource management, and manuscript review. Writing–review & editing, S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to cost effectiveness.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Datta, D.; Paul, M.; Murshed, M.; Teng, S.W.; Schmidtke, L. Soil moisture, organic carbon, and nitrogen content prediction with hyperspectral data using regression models. Sensors 2022, 22, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, A.; Saberioon, M.; Rossel, R.A.V.; Boruvka, L.; Klement, A. Spectroscopic measurements and imaging of soil colour for field scale estimation of soil organic carbon. Geoderma 2020, 357, 113972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, M.; Shi, X. Hyperspectral imaging for high-resolution mapping of soil carbon fractions in intact paddy soil profiles with multivariate techniques and variable selection. Geoderma 2020, 370, 114358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bao, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Tang, H.; Kong, F. Regional soil organic carbon prediction model based on a discrete wavelet analysis of hyperspectral satellite data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 89, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.S.; Rodrigues, M.; dos Santos, G.L.A.A.; de Oliveira, K.M.; Furlanetto, R.H.; Crusiol, L.G.T.; Cezar, E.; Nanni, M.R. Detection of soil organic matter using hyperspectral imaging sensor combined with multivariate regression modeling procedures. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 22, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Lin, C.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L. Estimation of soil nutrient content using hyperspectral data. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechanec, V.; Mráz, A.; Rozkošný, L.; Vyvlečka, P. Usage of airborne hyperspectral imaging data for identifying spatial variability of soil nitrogen content. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guan, K.; Zhang, C.; Lee, D.; Margenot, A.J.; Ge, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Y. Using soil library hyperspectral reflectance and machine learning to predict soil organic carbon: Assessing potential of airborne and spaceborne optical soil sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271, 112914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Hati, K.M.; Sinha, N.K.; Mridha, N.; Sahu, B. Regional soil organic carbon prediction models based on a multivariate analysis of the mid-infrared hyperspectral data in the middle indo-gangetic plains of india. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 127, 104372. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, R. Quantum-Enhanced Soil Nutrient Estimation Exploiting Hyperspectral Data with Quantum Fourier Transform. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 5507705. [Google Scholar]

- Chabrillat, S.; Milewski, R.; Ward, K.; Foerster, S.; Guillaso, S.; Loy, C.; Ben-Dor, E.; Tziolas, N.; Schmid, T.; van Wesemael, B.; et al. Monitoring soil properties using enmap spaceborne imaging spectroscopy mission. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023—2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 1130–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, B.; Qin, C.; Ji, W.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Y. High-resolution mapping of soil organic matter at the field scale using uav hyperspectral images with a small calibration dataset. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.; Simon, D. Analyzing the influence of emotional intelligence on investor behavior in developing regions: A prisma systematic review. Int. J. Manag. Humanit. 2022, 8, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshani, D.; Ramazanzadeh, R.; Farhadifar, F.; Ahmadi, A.; Derakhshan, S.; Rouhi, S.; Zarea, S.; Zandvakili, F. A prisma systematic review and meta-analysis on chlamydia trachomatis infections in iranian women (1986–2015). Medicine 2018, 97, e0335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, S.; Geetha, P.; Madhu, D. Flood susceptibility map of Periyar River basin using geo-spatial technology and machine learning approach. Remote Sens. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, A.; Subramoniam, R. Assessing soil nutrient content and mapping in tropical tamil nadu, india, through precursors iperspettrale della mission applicative hyperspectral spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa, R.; Bruno, R.; Falcioni, V.; Marrone, L.; Pascucci, S.; Pignatti, S.; Priori, S.; Rossi, F.; Tricomi, A.; Guarini, R. Topsoil properties estimation for agriculture from prisma: The tehra paper. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023—2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 3209–3212. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.A.; Parimala, N.; Pitchai, R. Crop Selection and Yield Prediction using Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2023 Second International Conference on Augmented Intelligence and Sustainable Systems (ICAISS), Trichy, India, 23–25 August 2023; pp. 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnutheerth, E.P.; Premjith, B.; Sowmya, V. Multimodal Fake News Prediction using a Two-Transformer Architecture approach with Llama. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches in Technology and Management for Social Innovation (IATMSI), Gwalior, India, 6–8 March 2025; Volume 3, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chitale, M.M.; Kundapura, S. High-resolution mapping of soil properties using avirisng hyperspectral remote sensing data—A case study over lateritic soils in Mangalore, India. In Trends in Civil Engineering and Challenges for Sustainability: Select Proceedings of CTCS 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 735–751. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Lee, S.J.; Cho, H. Partial Least Squares Regression Trees for Multivariate Response Data With Multicollinear Predictors. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 36636–36644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, X. Research and Prediction Based on Multiple Linear Regression and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Big Data and Algorithms (EEBDA), Changchun, China, 27–29 February 2024; pp. 1398–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silla, J.; Raj, S.D. Enhancement of Precision in Facial Age Identification using Ensemble Support Vector Machine Algorithm in Comparison with Lasso Regression Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Data Engineering and Communication Systems (ICDECS), Bangalore, India, 22–23 March 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xi, X.; Duan, S.; Ma, Z.; Long, X.; Ji, R. Research on a Hyperspectral Rice Yield Estimation Model Based on Random Forest. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Computer Science, Electronic Information Engineering and Intelligent Control Technology (CEI), Wuhan, China, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushant, R.; Ranjan, N.M.; Suyog, A.; Amey, R.; Asmita, M.; Shraddha, S. A Research Survey on Predicting Crop Yields and Recommending Fertilizers using Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Networking (ICAC2N), Greater Noida, India, 16–17 December 2024; pp. 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, X.; Ma, X. Application of Hyperspectral Technology Combined With Bat Algorithm-AdaBoost Model in Field Soil Nutrient Prediction. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 100286–100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasooli, N.; Mirzaei, S.; Pignatti, S. Electrical Conductivity and Calcium Carbonate Mapping Combining Prisma Imagery and Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024—2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7–12 July 2024; pp. 3678–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traisa, R.; Mishra, K.; Ahmed, Z. Exploring the Role of Hyper Spectral Image Analysis for Estimating Soil Quality. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kamand, India, 18–22 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; A, V.; Garg, R. Generating Accurate Crop Health Information Through Hyper Spectral Image Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications Theme: Healthcare and Internet of Things (AIMLA), Namakkal, India, 15–16 March 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zermas, D.; Nelson, H.J.; Stanitsas, P.; Morellas, V.; Mulla, D.J.; Papanikolopoulos, N. A Methodology for the Detection of Nitrogen Deficiency in Corn Fields Using High-Resolution RGB Imagery. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 1879–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhou, S.; Song, M.; Chang, C.-I. Semisupervised Hyperspectral Band Selection Based on Dual-Constrained Low-Rank Representation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 5503005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, B.; Wijata, A.M.; Tulczyjew, L.; Le Saux, B.; Nalepa, J. Soil Analysis with Very Few Labels Using Semi-Supervised Hyperspectral Image Classification. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024—2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7–12 July 2024; pp. 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duma, Z.-S.; Sihvonen, T.; Susiluoto, J.; Lamminpää, O.; Haario, H.; Reinikainen, S.P. Kernel-Based Retrieval Models for Hyperspectral Image Data Optimized with Kernel Flows. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th Workshop on Hyperspectral Imaging and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing (WHISPERS), Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 December 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, L. Indicator Spectral Bands and Logistic Models for Detecting Diesel and Gasoline Polluted Soils Based on Close-Range Hyperspectral Image Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4501413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, I.; Das, B.S. Large-Scale Mapping of Soil Quality Index in Different Land Uses Using Airborne Hyperspectral Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5507812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Hellwich, O.; Luo, G.; Chen, C.; He, H.; Ochege, F.U.; Van de Voorde, T.; Kurban, A.; De Maeyer, P. A Global Meta-Analysis of Soil Salinity Prediction Integrating Satellite Remote Sensing, Soil Sampling, and Machine Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4505815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Vishwakarma, A.K. Improvement of Complex Background Crop Image Segmentation using Sparse PSO. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 7th Conference on Information and Communication Technology (CICT), Jabalpur, India, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yin, C. Optimization of Image Compression and Decompression Performance Based on Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Interactive Intelligent Systems and Techniques (IIST), Bhubaneswar, India, 4–5 March 2024; pp. 702–707. [Google Scholar]

- David; S, E.V.H.; Febriana. Modified Local Updates of the Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for Image Edge Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th International Conference on Cyber and IT Service Management (CITSM), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 20–21 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).