Abstract

Livestock farming represents one of the primary sources of ammonia (NH3) and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and carbon dioxide (CO2), having a significant environmental impact. Reducing emissions and recovering gas systems from these livestock buildings necessitate measuring gas concentrations to mitigate environmental impacts using an accurate, high-cost portable device. This study aims to evaluate the concentration of NH3 and GHGs in a semi-open dairy farm located in southern Sicily, a region with a hot climate. The measurement campaign was carried out during the spring of 2025. The concentrations of NH3, CH4, CO2, and N2O were measured in different barn areas (i.e., manger, feeding alley, and service alley) using a portable gas detector (GASMET GT5000) based on Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) technology. Statistical analysis revealed that NH3 concentrations were highest in the feeding alley, while CH4 concentrations peaked at the manger. N2O levels stayed low because there was no straw. Future research should investigate gas concentrations across different seasons (e.g., winter, summer) to analyze gas patterns under different climatic conditions. Additionally, the use of an accurate portable device enables further investigations into other barn typologies within the Mediterranean area to assess how farm construction and management practices influence gas production.

1. Introduction

Globally, livestock farming, especially the dairy livestock sector, is one of the sources with the most significant environmental impacts due to the consumption of limited resources, such as land, water, and energy [1]. Emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and other pollutants from livestock activities affect human health, biodiversity, and ecosystems that are essential for global food security [2]. Special attention must be given to manure management, as improper handling can result in groundwater contamination with heavy metals and nitrate leaching, leading to a significant ecological impact [3,4,5,6].

In fact, livestock farming is one of the primary sources of ammonia (NH3) and GHG emissions, including methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and carbon dioxide (CO2), which have a significant ecological impact. GHGs from the livestock sector occur both directly and indirectly. Direct emissions are produced during enteric fermentation and manure management (mainly from storage), with estimated emission factors in 2019 of 130 and 20.8 kg head−1 year−1, respectively [7]. In detail, urine decomposition, manure storage, and animal respiration are the primary sources of CO2 emissions [8]. Enteric fermentation contributes most to CH4 production, and slurry from animals (comprising manure and urine) generates NH3 [8,9] indirectly through activities concerning feed production and deforestation [10].

According to FAO, livestock activities contributed 8.1 Gt CO2eq to global emissions in 2017 and 0.25 Gt CO2eq in Europe, accounting for more than 10% of the total emissions in the EU-28 [2]; these emissions mainly consist of CH4 (50%), N2O (24%), and CO2 (26%) [11]. Among all livestock species, cattle are the main contributors, with beef cattle accounting for 37.0% and dairy cattle accounting for 19.8%. Pigs follow (10.1%) and, finally, poultry (9.8%) [2]. Furthermore, the high concentration of livestock is considered a significant contributor to soil pollution due to nitrogen discharge in wastewater [12].

In the scientific literature, many studies have been carried out to better understand emission processes and identify key variables for developing mitigation techniques tailored to each manure management step. Hassouna et al. [13], in a dataset article, highlight the usefulness of the international project DATAMAN, as it provides relevant information on GHGs and NH3 emissions from manure management, depending on animal species, manure types, livestock building typologies, outdoor storage, and climatic conditions. In this context, accurate monitoring of pollutants at the farm scale allows for emission estimation and the consequent adoption of mitigation strategies, such as modifications to animal diets [14], housing systems (e.g., cooling systems, green walls) [15,16], and manure management (bioacidification, removal frequency) [17].

However, the current literature on concentrations in the Mediterranean region remains limited and is not yet comprehensive. For example, D’Urso et al. [18] analyzed gas concentrations in a semi-open dairy barn located in southern Italy during the summer season. Hempel et al. [19] assessed the risk of heat stress in European dairy cattle husbandry under different climate change scenarios, considering a dairy barn in a Mediterranean climate in Spain. Rodrigues et al. [20] estimated CH4 and NH3 emissions in three naturally ventilated dairy cattle barns during two years in the Northwest (NW) of Portugal. These studies provided emission levels and do not explore horizontal or vertical gradients. Yet understanding intra-barn spatial and temporal dynamics is essential for optimizing ventilation strategies, improving animal welfare, and generating more reliable emission estimates [21,22,23,24]. Ngwabie et al. [25] found that the concentrations of CO2, NH3 and CH4 showed considerable temporal and spatial variability inside the naturally ventilated barn. The authors further highlighted the importance of multi-location sampling during short-term measurements to enhance the measurement representativeness of gas concentrations. However, the spatial distribution of NH3 and GHG has been investigated in a few studies in the Mediterranean area. For example, Guimarães André et al. [21] analyzed the spatial distribution of environmental variables and GHGs in compost barn dairy systems. Other authors investigated the vertical [22] and horizontal [23] distribution from free-stall cubicles in dairy barns in specific areas in the animals’ occupied zone by using both high-cost (i.e., INNOVA photoacoustic analyser) and low-cost devices. Apostolico et al. [26] monitored NH3, CO2 and H2S concentrations and temperature-humidity index in a typical naturally ventilated buffalo barn in Mediterranean climate in Campania region by using advanced multi-sensor nodes. Another study by Sahu et al. [24] carried out in northern Europe analyzed the vertical distribution of CO2, NH3, and CH4 concentrations by using an FTIR spectrometer in a cubicle dairy barn. These studies analyzed the spatial distribution in different barns using both high-cost and low-cost measurement devices.

Each approach, however, presents notable limitations. Fixed FTIR and INNOVA technologies provide accurate and continuous data, but are costly and not easily adaptable to different barn locations. Conversely, low-cost, portable sensors allow for flexible deployment but often lack the accuracy required for robust concentration monitoring. Such methodological constraints have influenced a comprehensive understanding of spatial gas dynamics in livestock housing.

This study aims to fill the identified research gap by examining both the spatial and vertical distribution of NH3 and GHGs within a Mediterranean dairy barn, by using a portable FTIR device with high measurement accuracy. The investigation is organized to describe how gas concentrations vary along horizontal and vertical gradients inside the barn during hot climatic conditions. Addressing this research question, this research study proposed two main objectives: (i) to quantify the concentrations of CO2, CH4, NH3 and N2O during spring in a naturally ventilated dairy cattle building with a liquid manure system and automatic manure removal; (ii) to study gas concentration changes by both time and place inside the building.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Experimental Farm

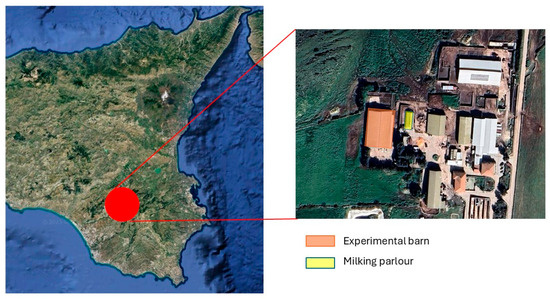

The measurement campaign was carried out at a dairy farm in the province of Ragusa (Italy) with geographic coordinates (Lat. 36.98281388520699, Long. 14.688905533291901). This farm was selected based on specific features, including construction type, ventilation system, flooring, and herd management practices (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of dairy farm.

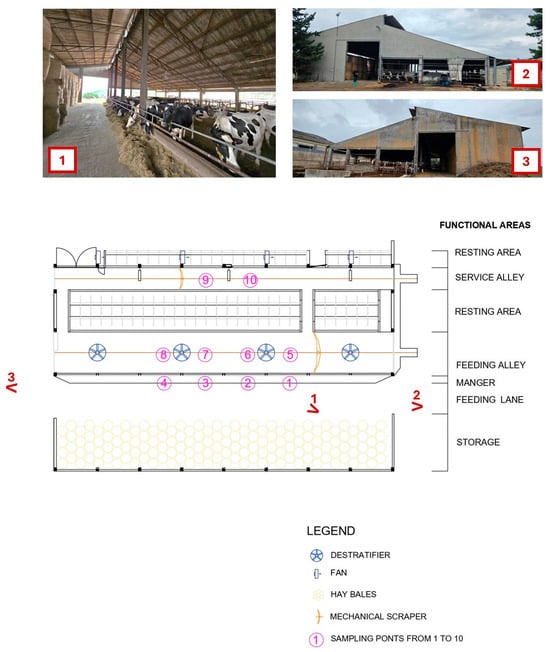

The barn has a structure characterized by an open shelter, which represents a construction typology typical of the area under investigation. The barn is oriented approximately 4° toward the northeast and measures approximately 41 m in length and roughly 27 m in width (total covered area of 1107 m2). A part of this area, covering 550 m2, is exclusively used for the cows’ free stall barn, while the remaining space is allocated for agricultural vehicle passage and hay storage (Figure 2). During the testing period, the barn housed 90 lactating cows characterized by a resting area with a concrete floor and cubicles in the central position. The cubicles were arranged in three rows: two were positioned head-to-head, and one was positioned laterally. The floor of the cubicles was made of olive leaves, which provided a non-slip surface and excellent shock absorption, ensuring the animals’ comfort. On the west side of the barn, there was a free passage leading to the manger where Unifeed was delivered using a feed mixer wagon. The manger had a free-access feeding front. In addition, two self-feeding stations were set up inside the barn to distribute both pellet and liquid feed.

Figure 2.

The principal layout of the barn with functional areas, and photographs illustrating indoor and outdoor barn views. The red numbers indicate the exact locations from which each picture was taken.

The shed of the barn was open on three sides and had a two-pitched roof without enclosing walls. These openings allowed for natural ventilation. In addition, the natural ventilation system was integrated with a mechanical ventilation system, comprising main helical destratifiers supported by auxiliary lateral fans. In detail, the mechanical ventilation system was equipped with four inverter-driven helical destratifiers, each with a diameter of 4 m, installed beneath the roof and aligned with two rows of head-to-head cubicles. Their main mechanical characteristics were as follows: a maximum outlet air velocity of 3.1 m/s (when temperature values exceeded 20 °C); an air flow rate of 141,000 m3 h−1; and a 12 m diameter coverage area. The four auxiliary fans, with a diameter of 0.70 m, were located laterally, aligned with the row of external cubicles. Their maximum outlet air velocity was 6.5 m s−1, and the air flow rate was 27,000 m3 h−1. The stall fans were activated automatically when the temperature inside the barn exceeded 16 °C, and their speed increased proportionally to the temperature.

The manure removal system consisted of two butterfly scrapers, installed in the service alley and the feeding alley, respectively. The scrapers operated roughly twice a day: first in the early morning (7 a.m.) at the end of the morning milking, and then at 5 p.m., during evening milking. Each of the two daily scraping activities had a duration of approximately 45 min. The manure was conveyed to a designated area north of the barn, covering about 260 m2.

Two brushes were installed along the service alley and activate automatically when cows make direct contact with them.

2.2. Animal Management

The 90 dairy cows housed in the barn during the experimental activities were of different animal species. Fifty percent of them were Holstein breed, while the remaining 50% were crossbred (named pro-cross) according to the following three-breed breeding program: Holstein × Monthbeliarde –> G1; G1 × Norwegian Red –> G2; G2 × Holstein –> G3. The herd averaged 189 days in milk. The average body weight was about 650 kg. The herd was characterized by good productivity, based on a mean milk yield of 33 L per day.

During the experimental period (i.e., spring), the average daily intake for a single cow was found to be composed of 4 kg of hay, 12 kg of pasture silage (silage corn), 9 kg of citrus pulp, and 12 kg of complementary feed. To be more precise, 8 kg of pasture feeding and 3 kg of concentrated feed from a self-feeder should be added. Regarding the nutritional characteristics of the daily intake, the dry matter intake was 24 kg (approximately 55% of the daily ration), comprising 32% neutral detergent fiber (NDF), 24% starch, and 17% crude protein. The remaining part was made of sugars, fats, and other minor nutrients.

During the experiment, cows were mainly housed in the barn except from 8:30 to 10:00 a.m. when they were at grazing in the early morning. Milkings occurred twice a day in a milking parlor located in a building close to the experimental barn (Figure 1). At the beginning of each session, the barn was empty; however, as each cow completed milking, each animal progressively returned to the barn. Therefore, at the end of each milking session (i.e., within approximately 3.5 h), all cows were back in the barn. The barn activities included the cleaning of the barn floor in both feeding and service alleys through automatic scrapers in the morning and in the afternoon. The feed was delivered by a feeding tractor every day at 10 a.m., and during the day, the farmer manually pushed up the feeding to the manger twice in the afternoon to ensure feed accessibility for cows. To better understand the sequence of the activities within the farm, Figure 3 shows the daily barn management related to both animals and the farmer’s activities.

Figure 3.

Daily barn management.

Based on this animal management, gas concentrations were detected during feeding in the barn, i.e., when the cows were present.

2.3. Measuring Device and Experimental Protocol

Gas concentrations of NH3 and GHG were measured using a Gasmet GT5000 Terra (Vantaa, Finland), supplied with Calcmet software version 14. This device is a portable, direct-reading device based on Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) technology. The operating principle of the instrument utilizes the spectrum created by the absorption of infrared light at specific wavelengths. The GT5000 Terra device measures absorbance—that is, the amount of light absorbed (which is characteristic of a particular gas)—using an interferometer. The main metrological features of the instrument are as follows:

- Spectral resolution: 8 cm−1;

- Scan Frequency: 10 scans s−1;

- Wavenumber Range: 900–4200 cm−1;

- Linearity Deviation: <2% of the measuring range.

The measuring device simultaneously identified and quantified multiple gases following the recommended standard method NIOSH 3800, as received by NMAM methods and protocols for gas sample collection (https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2003-154/pdfs/3800.pdf, accessed on 4 September 2025). Based on the NIOSH standard [27], nitrogen gas was used as the reagent, and it was extracted at a pressure of 0.5–0.8 bar with a maximum flow rate of 0.5 L min−1 during the experimental campaign.

The measurement protocol was designed to ensure consistent spatial coverage during data collection inside the barn. Because the portable device allowed for only limited monitoring time (i.e., it operated with two batteries, providing a total of approximately three hours of measurement), the sampling strategy was planned to select sampling times that maximized the representativeness of barn conditions. For this reason, measurements were carried out during the day, when cows were present inside the barn and animal activities, as well as housing-related concentrations, were expected to be at their highest. It should be noted that no measurements were taken during milking periods, as the barn was largely empty and milking occurred in a separate parlor adjacent to the main building. Sampling focused on the central area of the barn and excluded the bays near the entrances to minimize the effect of incoming or outgoing air flows. Data collection took place during periods of peak herd activity inside the barn, specifically before the slurry butterfly scrapers were turned on in both feeding and service alleys (Figure 2). In addition, the measurement campaign started when all animals were present in the barn, corresponding to the interval between the two daily milking sessions. To ensure equipment safety, special attention was given to water sources inside the barn, such as cooling showers or any other elements that the Gasmet analyzer could accidentally aspirate. For this reason, the presence of at least two operators was required during the measurements.

The sampling strategy consisted of 30 measurement points, evenly distributed both horizontally and vertically throughout the barn. In detail, the sampling points were vertically located at three different heights: the first 10 sampling points at 0.4 m from the ground, the second 10 sampling points at 1.5 m, and the third 10 sampling points at 3.0 m, respectively. At each height, these 10 sampling points had the following horizontal spatial distribution: four sampling points along the manger, four along the feeding alley, and two along the service alley, as shown in Figure 2.

The measuring device was configured to a sampling rate of six samples per minute over a continuous five-minute acquisition period. Accordingly, 30 measurements per session have been recorded for each sampling point. Given 30 sampling points, 900 measurements per day (30 points × 30 measurements) have been carried out. Therefore, considering the four monitoring days, the dataset included a total of 3600 measurements.

2.4. Testing Period and Data Collection

Data has been acquired in four different days (i.e., 4 April 2025, 8 May 2025, 22 May 2025 and 5 June 2025) in the spring season and characterized by similar climatic conditions in absence of precipitations. During measurements, the outdoor conditions were as follows: air temperature of 17.3 ± 5.3 °C, relative humidity of 58.9 ± 22.9%, and wind speed at 2 m above ground of 1.93 ± 0.21 m s−1. These days are equally distributed along the spring season.

Spring was chosen as the investigation period because, in Mediterranean climatic conditions, the seasonal rise in temperature is known to significantly influence gas dynamics within livestock buildings. Different studies [20,26,28] have shown that higher temperatures increase gas concentrations and worsen heat-stress conditions in dairy cattle.

Data collected have been organized in a datasheet and statistical analyses have been performed. A multivariable analysis based on a general linear model has been carried out to analyze the influence of Alley (i.e., feeding alley, manger, and service alley), Height (i.e., 0.4, 1.5, 3.0 m from the floor), and their interaction, Alley vs. Height, on gas concentrations. Based on this methodology, the analyses examined the simultaneous effect of two spatial dimensions (i.e., alleys for horizontal functional zones and heights for vertical levels) on gas concentrations.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the gas concentrations measured in the dairy barn during the spring season. The mean values of NH3, CH4, and CO2 concentrations were 1.61, 22.62, and 686.38, respectively. These gases showed high variability in the sampling locations during the observation period. Only N2O concentrations showed low variability, and the gas has not been analyzed thereafter.

Table 1.

Gas concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and ammonia (NH3).

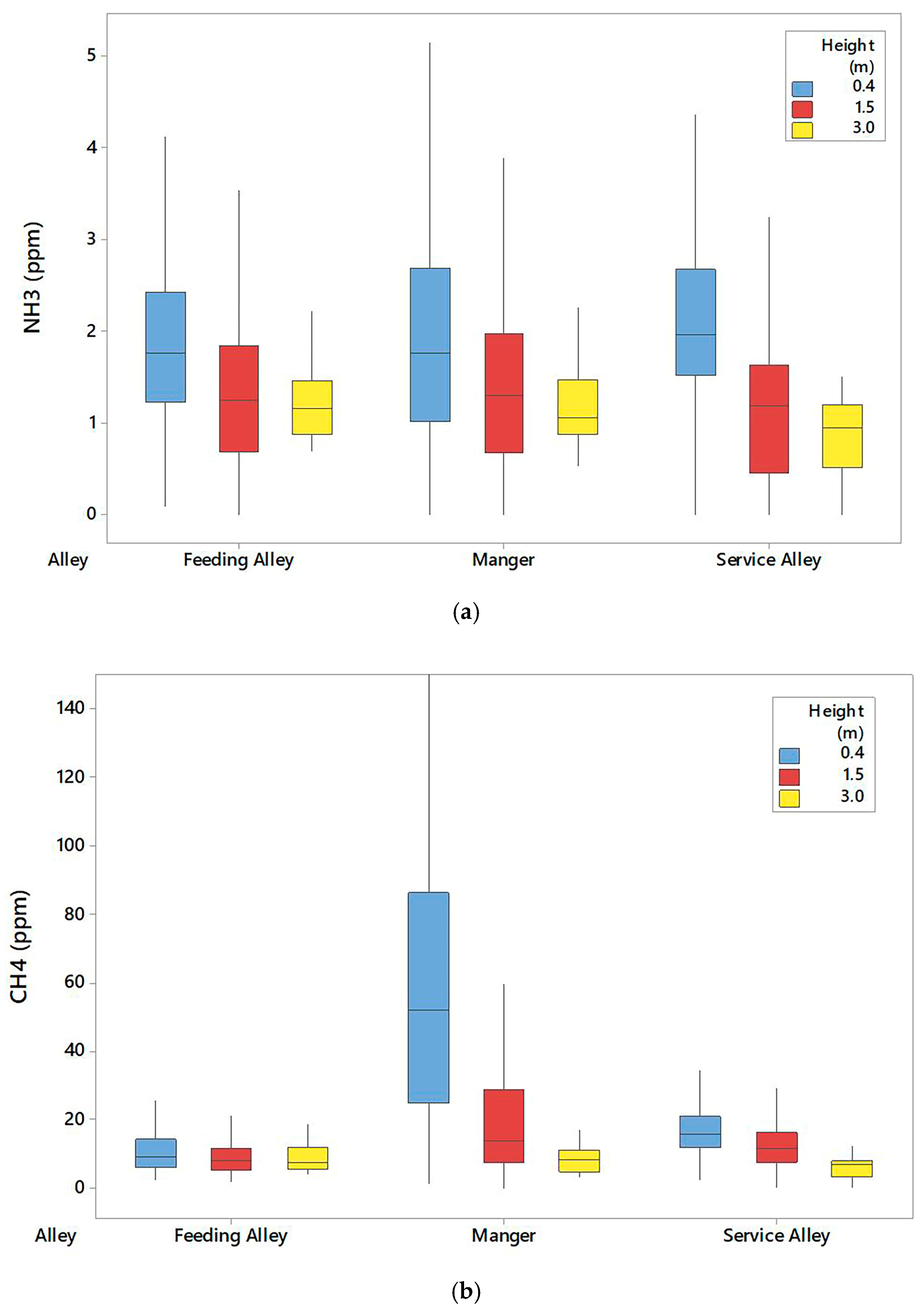

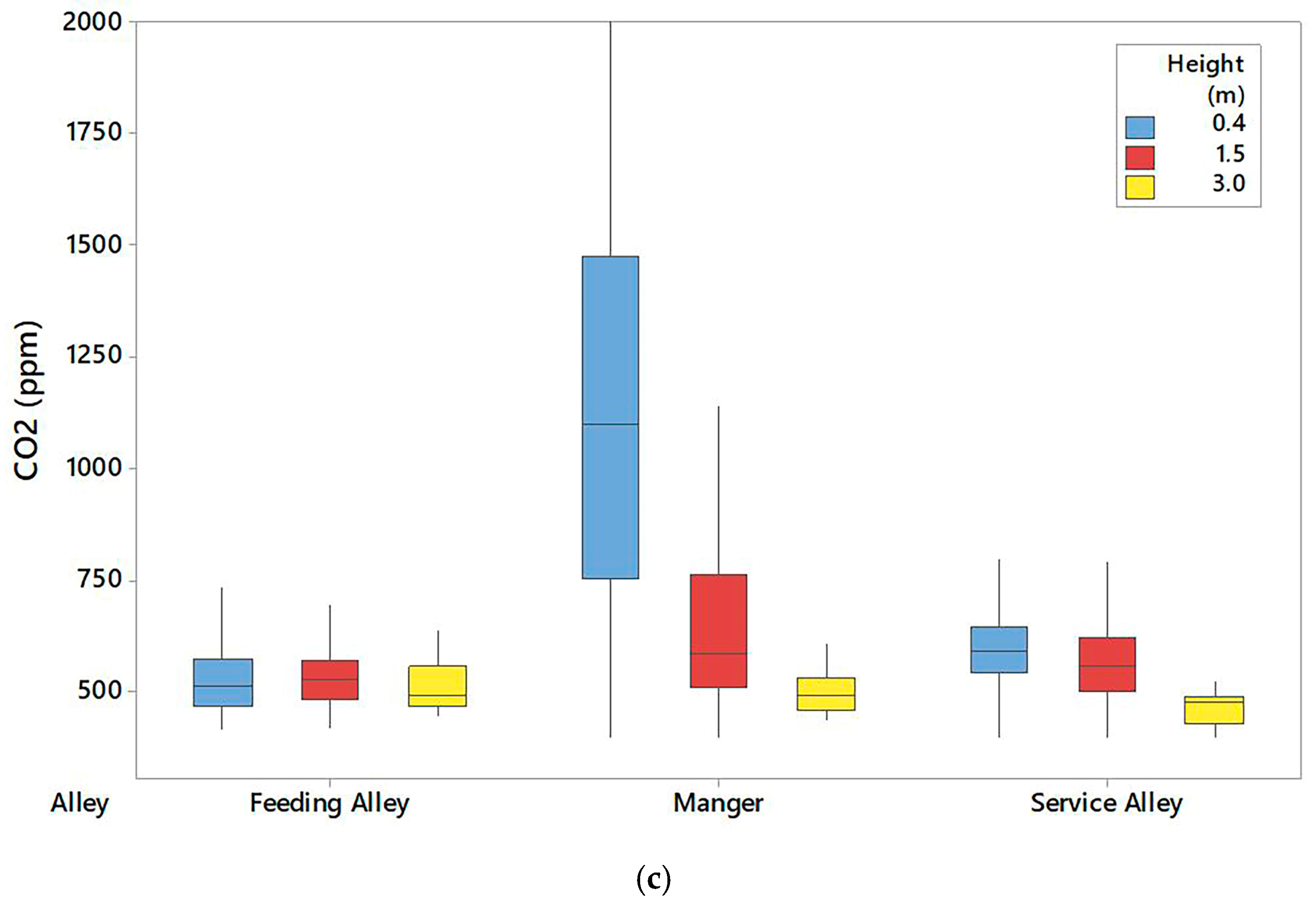

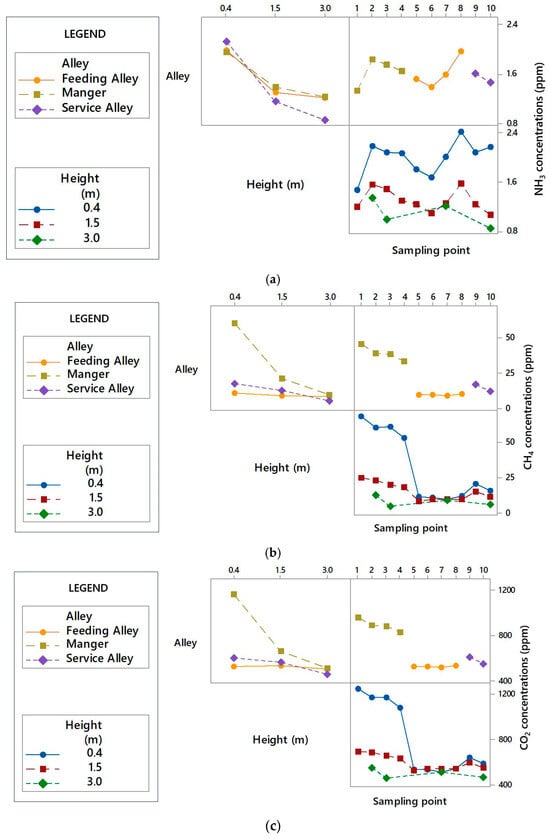

Gas concentrations are affected by the sampling location in the barn, with uneven gas distribution observed at different sampling points for CH4, NH3, and CO2. Figure 4 shows interaction plots for NH3, CH4, and CO2 concentrations, measured at three heights (i.e., 0.4 m, 1.5 m, and 3.0 m) across three barn areas (i.e., feeding alley, manger, and service alley). The results highlighted the variation in gas distribution both horizontally and vertically among the sampling points.

Figure 4.

Effect of sampling location on gas concentrations within the barn. The mean concentrations of (a) NH3, (b) CH4, and (c) CO2 are shown on the y-axis for three alley types (i.e., feeding alley, manger, and service alley), ten sampling points along each alley, and three sampling heights above the floor (i.e., 0.40, 1.50, and 3.00 m).

NH3 showed a strong Height effect (p < 0.001), whereas the main effect of Alley alone was not significant (p = 0.186). The Alley × Height interaction was significant (p < 0.001), due to the different vertical gradients among functional areas in the barn. Figure 4a highlights the steepest NH3 concentration decline between 0.4 and 3.0 m, due to the air dilution away from the source of gas production. For this reason, the mean value of NH3 concentrations decreased with increasing Height from the floor (Table 2). In detail, Figure 4a shows that the lowest NH3 variability has been recorded in all alleys at a height of 3.0 m from the floor.

Table 2.

Gas concentrations of ammonia (NH3), methane (CH4), and carbon dioxide (CO2) at different heights in the barn.

CH4 and CO2 exhibited significant main effects of Alley (p < 0.001), Height (p < 0.001), and strong interactions Alley × Height (all p < 0.001). CH4 showed the highest concentrations at 0.4 m in the Manger compared to the Feeding and Service alleys. In detail, CH4 concentrations are declining at 1.5 and 3.0 m in all zones (Figure 4b). The Manger area showed the highest mean value of CH4 concentration, followed by those recorded at the Service alley and Feeding alley (Table 3). The highest variability of CH4 concentrations occurred at 0.4 m from the floor, followed by measurement carried out at the Feeding alley (Figure 4b). These patterns indicate a substantial near-source accumulation, modulated by barn functional layout. CO2 concentrations exhibited a similar pattern to CH4 concentrations (Figure 4c) due to their high correlation (r = 0.94, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Gas concentrations of ammonia (NH3), methane (CH4), and carbon dioxide (CO2) at different alleys in the barn.

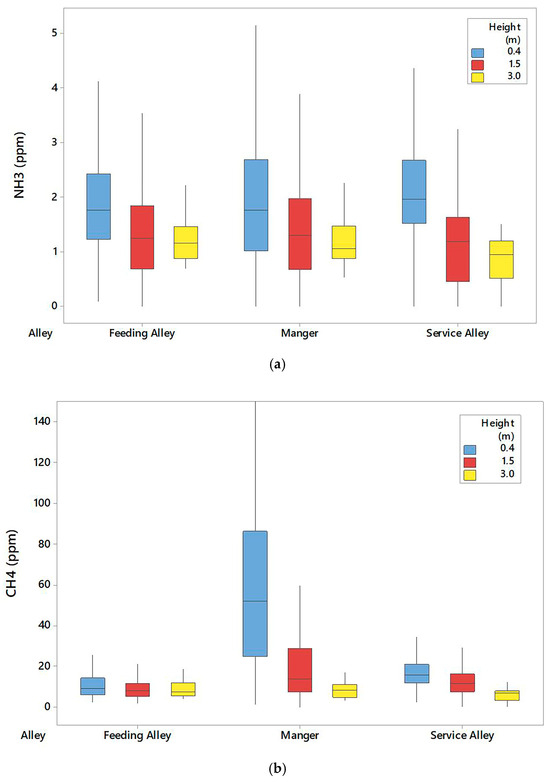

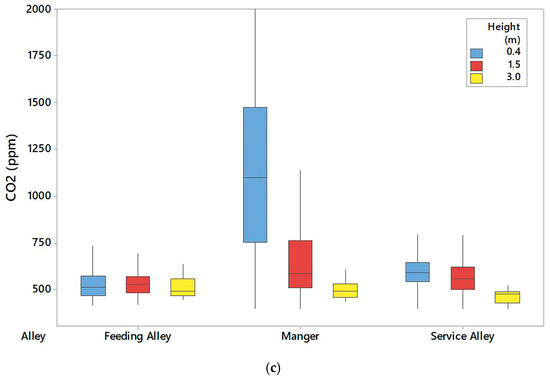

Specifically, NH3 and CH4 concentrations were significantly influenced by height (p < 0.001), with the highest average concentrations at 0.4 m, followed by those at 1.5 m and 3.0 m, which did not differ significantly from each other (Table 2). NH3 and CH4 levels varied significantly (p < 0.05) among different alleys (Table 3). The highest mean NH3 concentration was recorded in the feeding alley, while concentrations in the service alley and the feeding alley showed no significant difference from each other.

Regarding CH4, concentrations varied significantly among the manger, feeding alley, and service alley. The manger area showed the highest average CH4 concentration, followed by the service alley and feeding alley (Figure 5). CO2 concentration also varied significantly with sampling height (p < 0.001). Gas concentrations measured at the three heights differed significantly, with concentrations decreasing as height increased. CO2 concentrations also varied significantly by alley (p < 0.001), where the manger represents the location with the highest average concentrations, followed by the service alley and the feeding alley.

Figure 5.

Boxplot of (a) ammonia (NH3), (b) methane (CH4), and (c) carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations (ppm) measured at three sampling heights above the floor (40, 150, and 300 cm) across different barn locations (feeding alley, manger, and service alley).

4. Discussions

4.1. Gas Distribution in the Barn

The results of this study highlight the uneven distribution of the gases in the barn environment.

NH3 was mainly measured close to the floor (0.4 m), due to the presence of manure, which represents the primary source of surface emissions. The feeding alley consistently showed the highest NH3 levels across sampling points compared to the manger and service alley. This result is related to the higher animal density, and, consequently, more manure and cows walking on it, reducing airflow near the feeding area. Therefore, the highest concentrations were observed due to a greater buildup of NH3 near the floor, resulting from the decomposition of manure and urine, as well as its higher density relative to air.

The service alley exhibited the lowest concentrations, likely due to less manure accumulation and higher air flow in that area. Additionally, raising the sampling height to 1.5 m and 3.0 m led to lower NH3 levels, making differences between alleys less noticeable. This suggests a dilution and vertical dispersion of NH3 within the barn, especially at heights above the animals’ occupied zone. Both CH4 and CO2 showed similar vertical declines, peaking at 0.4 m and declining by 1.5 m and 3.0 m. In the literature, CH4 and CO2 have been found to be highly correlated [18]. In fact, the vertical gradient for CH4 and CO2 showed that these gases are mainly produced at the cow level, with CH4 generated by enteric fermentation and CO2 produced by animal respiration. The decrease in concentration with height was attributed to dilution and dispersion due to natural ventilation, as observed in previous studies [22,23]. In the manger, concentrations of both CH4 and CO2 were highest, which is related to dense animal activity, feeding processes, and proximity to emission sources. The findings from this study align with those of Sahu et al. [24], who observed a concentration gradient of NH3, CH4, and CO2 at varying heights at the outlet of a naturally ventilated dairy barn. In detail, their work confirmed that higher sampling measurement points corresponded to lower pollutant concentrations and simultaneously highlighted the importance of considering vertical dispersion in monitoring and modeling efforts. The spatial variability recorded at different sampling locations was in line with the results of D’Urso et al. [22,23]. In particular, the number and position of sampling points can significantly affect the data in specific barn areas, suggesting that multi-point central sampling improves representativeness and reduces uncertainty, with notable effects on emission estimation. In this context, the use of low-cost sensors could facilitate data collection in dairy barns. As reported by Andrè et al. [21], the application of spatially distributed, low-cost sensors combined with geostatistical mapping can contribute to improved measurement resolution, enabling the identification of areas with high gas concentrations.

The findings from this study support the need for monitoring protocols to include multiple vertical levels and horizontal distribution of sampling points. In particular, in this open construction typology, measurement points could be strategically located in the central areas of the barn to improve data quality and representativeness. Because gas concentrations vary in space, multiple measurement points are required. In this context, this research utilized a portable FTIR device to measure gases at various spatially distributed measurement points within livestock housing. In the literature, many portable, low-cost devices are used to reduce device and experimental costs, though these devices often require specific calibration or correction models to improve measurement quality [29]. The use of a portable FTIR instrument enabled high-resolution spatial mapping, thereby avoiding the logistical issues associated with a large fixed sensor network. Following the measurement protocol for the portable FTIR device described in the Section 2.3, this study provided insight into the spatial distribution of gas concentrations at a dairy farm under a Mediterranean climate. Given the instrument’s accuracy and portability, along with the standardized protocol, the methodology could be replicated in other barns and under different climate conditions.

More specifically, the study highlights an innovative aspect of the use of the Gasmet GT5000 Terra, a portable FTIR analyzer that has not been used in livestock or agricultural research before, except for earlier versions. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, only two previous studies [30,31] have employed analyzers from the DX4000 series (in both cases the DX4030 model).

First, it is important to highlight the key differences between the GT5000 Terra and the previous models of the DX4000 series. These differences include not only ergonomics, such as lighter weight and smaller size, but also technical and construction features that enhance performance. Regarding connectivity, the GT5000 Terra provides more wireless and plug-in options than its predecessors, making measurements inside the barn easier. Thanks to its redesigned internal layout, the optics in the GT5000 Terra are fully integrated. Fewer moving parts make the gas analyzer more stable and less vulnerable to vibration. Additionally, the optical path length in the GT5000 Terra has been reduced from 9.8 m for the DX4040 to 5 m. This reduction allows the instrument’s response time to decrease while maintaining the same sensitivity (in the sub-ppm range). Finally, the GT5000 Terra has an IP54 rating, making it resistant to dust and splashes and better suited for operation in harsh environments like barns. This premise helps better understand the differences between this study and the previous studies conducted with earlier DX4000 models.

It should be noted that the sampling design of our study was based on a dataset of 3600 measurements collected from a single barn. These 3600 measurements were taken at 30 different measuring points within the barn, arranged at 3 different heights from the ground (i.e., 30 points × 30 measurements × 4 sessions). While the previous study conducted by Witkowska et al. [30] used a Gasmet DX4030 analyzer to gather 200 measurements across 4 different dairy barns (i.e., 50 measurements per month per barn). The 50 measurements in that study were organized into 10 samples at 5 points (at cow head level) within the barn- one point in the center and two points on each diagonal line. The test period (one day per barn) was conducted across autumn and winter. Compared to the study by Witkowska et al. [30], our study’s sampling strategy included more days during the same season (4 instead of 2), more points within the barn (30 instead of 5), more samples per point (30 instead of 10) and more measurements (3600 instead of 100 during one season). Furthermore, the sampling size for each point was more rigorous: 30 measurements per point represent a statistically representative and significant dataset. The lower number of acquisitions in Witkowska et al. [30] was probably caused partly by the Gasmet model used (i.e., less effective and ergonomic) and partly by the different purpose of the work (i.e., evaluation of the influence of housing systems and technological solutions on greenhouse gas and odorous gas emissions from various dairy farms).

Regarding the work by Haque et al. [31], although based on measurements performed with the previous Gasmet DX-4030 model, it aims to investigate individual methane production within an automatic milking system. By conducting continuous measurements for 7 consecutive days (with a sampling frequency of 15 s) and placing the measuring instrument in a single location (single measurement point), the measurement strategy is not comparable to that adopted in our research.

The topics of our study appear to align more closely with the recent study by Andrè et al. [21], which focused on analyzing the spatial distribution of environmental variables and GHGs within compost barn dairy systems. However, Andrè et al. [21] used a prototype equipped with fixed low-cost gas sensors to continuously monitor the spatial distribution of CH4 and CO2 at two different heights (0.25 m and 1.5 m) relative to the animals’ bedding. This approach is directly comparable to studies by D’Urso et al. [22,23], where a similar continuous monitoring technique was used to assess the horizontal and vertical distribution of GHGs with both high-cost (i.e., spectroscope photoacoustic analyser, PAS) and low-cost portable devices. Additionally, the use of low-cost devices introduces several limitations that affect measurement reliability, such as low selectivity and responses to interfering gases.

4.2. Implication of Study

Accurate assessment of gas concentrations is important for controlling air quality in the barn environment to ensure both animal and operator safety. The measurement of gas concentrations is used to estimate emissions, which are computed by integrating concentration measurements with ventilation rate data [32]. Although the present study focuses on the characterization of concentration dynamics in a typical Mediterranean dairy barn, the gas monitoring is a relevant preliminary step for emission modeling and mitigation studies. In fact, future research should estimate emissions across different seasons (e.g., winter, summer) to analyze gas patterns under different climatic conditions. Additionally, the use of an accurate portable device enables further investigation into other barn typologies in the Mediterranean to assess how farm construction and management practices influence gas production. In this way, more information will be available for the improvement of emission inventories also in the Mediterranean area [13]. As deduced from a comprehensive bibliometric analysis on the assessment of NH3 and GHG emissions in dairy cattle farms conducted by Ferraz et al. [33], dairy cattle housing and manure management are the main sources of NH3, CH4, CO2 and N2O emissions that need to be addressed. High emissions affecting the environment, along with growing attention to the production process, have driven research on decarbonization and circularity in the livestock sector.

Currently, the reference legislation for regulating emissions encompasses a substantial number of directives and guidelines at both national and European levels. Among these regulations, the National Emission reduction Commitments (NEC) Directive (EU) 2016/2284 stands out, which sets national emission reduction targets for five key air pollutants [34]. For Italy, a 16% reduction in ammonia emissions by 2030, compared to 2005 levels, is recommended. Under the NEC Directive, Member States are required to develop and implement a National Air Pollution Control Programme (NAPCP), specifying any measures focused on reducing emissions, particularly within agriculture.

This research contributes to the environmental monitoring of GHG and NH3 concentrations in dairy farms in the Mediterranean area. The evaluation of gas concentrations is a preliminary step toward monitoring gas emissions, which can offer numerous benefits for sustainability and resource efficiency within a circular economy perspective, even through the adoption of voluntary practices. In fact, although most dairy activities are regulated by the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) 2010/75/EU, the voluntary adoption of Best Available Techniques (BAT) could be a first step toward mitigating emissions in smaller-scale systems [35]. BAT serves as guidance for intensive livestock production on reducing emissions from manure storage, barn ventilation, and animal nutrition. Initially developed for pig and poultry farming, most BAT principles apply to dairy farming and are increasingly used to update national guidelines within the Member States.

Moreover, gas monitoring is necessary to assess the effectiveness of manure management practices that have been implemented, such as manure storage and treatment systems. High concentrations may be related to inefficient decomposition processes or leaks, allowing for timely interventions to optimize management, reduce pollutant emissions, and maximize the potential for recovering nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus) for use as organic fertilizers. Since CH4 and N2O are important greenhouse gases, their accurate monitoring allows for the identification of their respective emission sources. This enables the implementation of mitigation strategies, such as modifying animal diets (i.e., reducing crude protein content and using feed additives) as well as biogas production (in the case of CH4) through anaerobic waste management. Thus, manure, traditionally considered waste, can be transformed into biogas, which can be used as a renewable energy source on the farm or sold to third parties, replacing fossil fuels and contributing to a low-carbon economy. Manure could be transformed into digestate fertilizers and, through advanced treatment processes, even recovered water. So, livestock waste could be considered a key resource for bioenergy production and biofertilizers [36]. These considerations take on even greater relevance when considering the exponential growth in global production of agricultural residues (waste from both livestock farming and agriculture itself), driven by the increasing demand for food and raw materials [37,38].

Regarding CH4, it is worth noting that a recent authoritative regulatory document, the EU Methane Strategy (COM/2020/663), has been published. This is part of the European Green Deal and aims to encourage significant efforts to estimate and reduce CH4 emissions in agricultural activities. It supports Measurement, Reporting and Verification (MRV) systems, promoting any technology based on anaerobic digestion technologies and any low-emission innovation within farming systems [39]. Therefore, this document aligns with the Circular Economy Action Plan (COM/2020/98), focusing on resource efficiency and the valorization of waste and byproducts through the application of sustainability in agriculture [40].

Even the impact on the livestock environment should not be overlooked. Excessive concentrations of gases such as NH3 can compromise the respiratory health of animals, reducing their well-being and, consequently, productivity (decreased growth, lower milk yield). Continuous monitoring helps maintain a healthy environment, reducing the need for veterinary interventions and the use of drugs or pharmaceuticals, contributing to a more efficient livestock farming system with lower environmental impacts.

In detail, the barn analyzed has suitable ventilation systems and manure storage equipment. The concentrations of the main gases harmful to animals (NH3 and CO2) measured during the campaign were consistently below the limits set by Classyfarm (Italian Protocol on the assessment of animals’ well-being following European Food Safety Authority guidelines) for dairy cows inside the stalls: NH3 = 20 ppm; CO2 = 3000 ppm [41].

However, even a healthy farming environment can improve the economic efficiency of the farm, both through reduced operating costs (such as veterinary costs and lost earnings due to illnesses or premature deaths of cows) and through an improved corporate image (greater access to potential financing).

5. Conclusions

This study provides information on gas concentration levels in a typical dairy barn, located in southern Italy, in the densest areas of dairy farms. This research focused on measuring NH3 and GHG concentrations in different functional areas at horizontally and vertically distributed sampling points.

The influence of Alley (i.e., feeding alley, manger, and service alley), Height (i.e., 0.4, 1.5, 3.0 m from the ground), and their interaction on gas concentrations was analyzed through a multivariable analysis. The results fund show a significant variation in gas distribution both horizontally and vertically. In the feeding alley, the highest NH3 levels were due to manure buildup, animal presence, and limited airflow. The manger area had the highest CH4 and CO2 levels, driven by dense feeding activity and prolonged animal presence. The service alley had the lowest and most stable gas levels, resulting from minimal excreta load and better cross-ventilation.

Regarding Height effects, NH3 was found to have a strong Height effect (p < 0.001).

CH4 and CO2 exhibited significant main effects of both Alley (p < 0.001) and Height (p < 0.001), and strong interactions were found for Alley × Height (all p < 0.001).

Monitoring gas concentrations in livestock farming environments is a fundamental tool for promoting the principles of the circular economy. It enables the transformation of waste into resources, thereby reducing the environmental impact of livestock farming, enhancing animal health and productivity, and providing economic benefits for livestock farms.

As a future target is to define sustainable manure management practices, once the most critical areas within a typical cattle barn have been identified, greenhouse gas and pollutant concentrations can be measured in several barns located in a hot climate area. Research should consider how animal density changes throughout the day and the possible effects of seasonality on dairy farm management and emissions dynamics. Therefore, appropriate collection and reuse of manure and its byproducts could be a future option.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., P.R.D. and G.M.; methodology, M.B., S.L., P.R.D. and G.M.; software, M.B., S.L., P.R.D. and G.M.; validation, M.B., P.R.D. and G.M.; formal analysis, M.B. and P.R.D.; investigation, M.B., S.L., B.T., M.G. and G.M.; resources, G.M.; data curation, M.B., S.L., P.R.D. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and P.R.D.; writing—review and editing, M.B., P.R.D. and G.M.; visualization, B.T., M.G., M.B., P.R.D. and G.M.; supervision, G.M.; project administration, G.M.; funding acquisition, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research project MITIgA (Monitoraggio ed Innovazione Tecnologica per la riduzione dell’Impatto Ambientale degli allevamenti zootecnici—Monitoring and Technological Innovation for Reducing the Environmental Impact of Livestock Farming), “National Research Centre for Agricultural Technologies (Agritech)”, project code MUR CN00000022 CUP: J83C22000830005. Furthermore, the work of P.R. D’Urso has been funded by the European Union (NextGeneration EU), through the MUR-PNRR project SAMOTHRACE (CUP: E63C22000900006; CODE_ECS00000022). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions; neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the APC central fund of the University of Messina. They are also grateful to the ENFRA dairy farm for their continuous support and assistance with this research, which was made possible through the assistance provided during all the surveys carried out.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ferrari, G.; Ioverno, F.; Sozzi, M.; Marinello, F.; Pezzuolo, A. Land-use change and bioenergy production: Soil consumption and characterization of anaerobic digestion plants. Energies 2021, 14, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyraud, J.L.; MacLeod, M. Future of EU Livestock—How to Contribute to a Sustainable Agricultural Sector. In Final Report, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sheer, A.; Sardar, M.F.; Younas, F.; Zhu, P.; Noreen, S.; Mehmood, T.; Farooqi, Z.U.R.; Fatima, S.; Guo, W. Trends and social aspects in the management and conversion of agricultural residues into valuable resources: A comprehensive approach to counter environmental degradation, food security, and climate change. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forge, T.; Kenney, E.; Hashimoto, N.; Neilsen, D.; Zebarth, B. Compost and poultry manure as preplant soil amendments for red raspberry: Comparative effects on root lesion nematodes, soil quality and risk of nitrate leaching. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 223, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. Hydrothermal liquefaction of typical livestock manures in China: Biocrude oil production and migration of heavy metals. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2018, 135, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, H.H.; Mollenhorst, H.; Oonincx, D.G.; Bikker, P.; Meerburg, B.G.; De Boer, I.J. From environmental nuisance to environmental opportunity: Housefly larvae convert waste to livestock feed. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Annual European Union Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2019 and Inventory Report 2021; Submission to the UNFCCC Secretariat; European Environment Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Katwal, S.; Singh, Y.; Gupta, R.; Grewal, R.S. Seasonal dynamics and climatic influences of greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4) and ammonia (NH3) concentrations on loose housing cattle shed. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 94, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samer, M. Abatement Techniques for Reducing Emissions from Livestock Buildings; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, G.; Provolo, G.; Pindozzi, S.; Marinello, F.; Pezzuolo, A. Biorefinery development in livestock production systems: Applications, challenges, and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.D.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; Rosales, M.M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s long shadow. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; Ai, P.; Alengebawy, A.; Marinello, F.; Pezzuolo, A. An assessment of nitrogen loading and biogas production from Italian livestock: A multilevel and spatial analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassouna, M.; Simon, P. DATAMAN: A global database of methane, nitrous oxide, and ammonia emission factors for livestock housing and outdoor storage of manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2022, 52, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenis, N.P.; Jongbloed, A.W. New Technologies in Low Pollution Swine Diets: Diet Manipulation and Use of Synthetic Amino Acids, Phytase and Phase Feeding for Reduction of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Excretion and Ammonia Emission—Review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 12, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaliano, S.; Cascone, G.; D’Urso, P.R. Mitigating Built Environment Air Pollution by Green Systems: An In-Depth Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchiaro, A.; Vitaliano, S.; Cinardi, G.; D’Urso, P.R.; Cascone, S.; Arcidiacono, C. Green Wall System to Reduce Particulate Matter in Livestock Housing: Case Study of a Dairy Barn. Buildings 2025, 15, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinardi, G.; Vitaliano, S.; Fasciana, A.; Fragalà, F.; La Bella, E.; Santoro, L.M.; D’Urso, P.R.; Baglieri, A.; Cascone, G.; Arcidiacono, C. Preliminary Analysis on Bio-Acidification Using Coffee Torrefaction Waste and Acetic Acid on Animal Manure from a Dairy Farm. Agriculture 2025, 15, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Valenti, F.; Cascone, G. Assessing Influence Factors on Daily Ammonia and Greenhouse Gas Concentrations from an Open-Sided Cubicle Barn in Hot Mediterranean Climate. Animals 2021, 11, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempel, S.; Menz, C.; Pinto, S.; Galán, E.; Janke, D.; Estellés, F.; Müschner-Siemens, T.; Wang, X.; Heinicke, J.; Zhang, G.; et al. Heat stress risk in European dairy cattle husbandry under different climate change scenarios-uncertainties and potential impacts. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2019, 10, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.R.F.; Silva, M.E.; Silva, V.F.; Maia, M.B.; Cabrita, A.R.J.; Trindade, H.; Fonseca, A.J.M.; Pereira, J.L.S. Implications of seasonal and daily variation on methane and ammonia emissions from naturally ventilated dairy cattle barns in a Mediterranean climate: A two year study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 173734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, A.L.G.; Ferraz, P.F.P.; Ferraz, G.A.e.S.; Ferreira, J.C.; de Oliveira, F.M.; Reis, E.M.B.; Barbari, M.; Rossi, G. Spatial Distribution of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Environmental Variables in Compost Barn Dairy Systems. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Assessment of a Low-Cost Portable Device for Gas Concentration Monitoring in Livestock Housing. Agronomy 2023, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Analysis of the Horizontal Distribution of Sampling Points for Gas Concentrations Monitoring in an Open-Sided Dairy Barn. Animals 2022, 12, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, H.; Hempel, S.; Amon, T.; Zentek, J.; Römer, A.; Janke, D. Concentration Gradients of Ammonia, Methane, and Carbon Dioxide at the Outlet of a Naturally Ventilated Dairy Building. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwabie, N.M.; Schade, G.W.; Custer, T.G.; Linke, S.; Hinz, T. Multi-location measurements of greenhouse gases and emission rates of methane and ammonia from a naturally ventilated barn for dairy cows. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 103, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolico, A.; Di Perta, E.S.; Grieco, R.; Cervelli, E.; Pindozzi, S. Gas concentrations and THI monitoring in a naturally ventilated buffalo farm: First results with advanced multi-sensor node. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry MetroAgriFor, Padova, Italy, 29–31 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, K. Harmonization of NIOSH Sampling and Analytical Methods with Related International Voluntary Consensus Standards. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2015, 12, D107–D115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Ammonia and greenhouse gas distribution in a dairy barn during warm periods. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.R.; Finocchiaro, A.; Cinardi, G.; Arcidiacono, C. In-Field Performance Evaluation of an IoT Monitoring System for Fine Particulate Matter in Livestock Buildings. Sensors 2025, 25, 4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D.; Korczyński, M.; Koziel, J.A.; Sowińska, J.; Chojnowski, B. The effect of dairy cattle housing systems on the concentrations and emissions of gaseous mixtures in barns determined by Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2020, 20, 1487–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.N.; Cornou, C.; Madsen, J. Individual variation and repeatability of methane production from dairy cows estimated by the CO2 method in automatic milking system. Animal 2015, 20, 1487–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogink, N.W.M.; Mosquera Losada, J.; Calvet, S.; Zhang, G. Methods for measuring gas emissions from naturally ventilated livestock buildings: Developments over the last decade and perspectives for improvement. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 116, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, P.; Ferraz, G.; Ferreira, J.; Aguiar, J.; Santana, L.; Norton, T. Assessment of Ammonia Emissions and Greenhouse Gases in Dairy Cattle Facilities: A Bibliometric Analysis. Animals 2024, 14, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2016/2284 of The European Parliament and of The Council of 14 December 2016 on the Reduction of National Emissions of Certain Atmospheric Pollutants, Amending Directive 2003/35/EC and Repealing Directive 2001/81/EC (Text with EEA Relevance); Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on Industrial Emissions (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control); Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; Volume 334, pp. 17–119. [Google Scholar]

- Diacono, M.; Persiani, A.; Testani, E.; Montemurro, F.; Ciaccia, C. Recycling agricultural wastes and by-products in organic farming: Biofertilizer production, yield performance and carbon footprint analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlato, M.C.M.; Valenti, F.; Midolo, G.; Porto, S.M.C. Livestock Wastes Sustainable Use and Management: Assessment of Raw Sheep Wool Reuse and Valorization. Energies 2022, 15, 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekleitis, G.; Haralambous, K.J.; Loizidou, M.; Aravossis, K. Utilization of Agricultural and Livestock Waste in Anaerobic Digestion (A.D): Applying the Biorefinery Concept in a Circular Economy. Energies 2022, 13, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions (on an EU Strategy to Reduce Methane Emissions); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0663 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Energy, Climate Change, Environment. A New Circular Economy Action Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://www.astrid-online.it/static/upload/new_/new_circular_economy_action_plan_annex.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Aagaard, A.; Berny, P.; Chaton, P.F.; Antia, A.L.; McVey, E.; Brock, T. Risk Assessment for Birds and Mammals. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e07790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).