Abstract

In response to the urgent need for full-process mechanization in Xinjiang’s cotton–cumin intercropping system, and to address the prominent bottlenecks of missing equipment for key harvesting steps and reliance on manual operations, we developed a cumin harvester and investigated its operating mechanisms. Guided by the agronomic parameters of the intercropping system, we executed a system-level design centered on the header unit, performed multi-objective optimization using orthogonal experiments and regression modeling, and conducted field validation. Results show: stubble height of 32.6 mm, harvester reel speed of 28 r/min, and forward speed of 3.26 km/h. Under this parameter configuration, the harvest rate was 89.54%, and the average damage rate was 7.33%. Field trials indicated a harvest rate of 88.2% and an average damage rate of 5.6%, with deviations from model predictions of 1.34% and 1.73%. The optimal reel index (λ = 1.69), the longitudinal component of the reel tine motion, prevents repeated impacts on the plants, reducing shattering and threshing damage; the axial component provide reliable support and smooth guidance to the stalks, ensuring continuous, steady cutting; the optimized stubble height is lower than the plant’s center of mass.

1. Introduction

Cumin is a globally important spice and medicinal plant and a drought-tolerant plant that dislikes excessive moisture, Cottonm cumin intercropping is recognized as an efficient agricultural system that maximizes economic returns, optimizes resource utilization, mitigates agricultural risks, and significantly enhances land use efficiency. However, the harvesting of cumin has long relied predominantly on manual labor. This process requires workers to perform long hours of high-intensity work, resulting in remarkably low efficiency and high costs, particularly in areas with relatively low levels of agricultural mechanization [1,2]. Xinjiang possesses distinct geographical and technological advantages in the research, development, and deployment of agricultural machinery [3]. It serves as an excellent practical example of sustainable and circular agriculture. In 2024, cotton in Xinjiang covered 83,000 hectares, accounting for more than 70% of national output [4,5,6]. Against this backdrop, advancing mechanization for cotton–cumin intercropping would not only markedly enhance land use efficiency, reduce labor costs, and strengthen the modernization of agriculture in Xinjiang but also provide robust support for Chinese agricultural machinery and technologies to enter Belt and Road markets, carrying important strategic significance [7,8,9]. However, under current intercropping practices, the cumin-harvesting phase still faces a “no machine available” bottleneck. There is an urgent need to develop dedicated harvesters tailored to the cotton–cumin intercropping model to enable efficient mechanized cumin harvesting.

For non-intercropped cumin, Kumar [10] developed a cumin reaper in which a knife bar drives blades to cut plants laterally, achieving integrated collection and loading. Chen [11] designed a small orchard-type cumin harvester capable of cutting stems at different heights and incorporating straw crushing and storage functions. Both devices are complete in design and can harvest cumin effectively. The cotton–cumin intercropping environment is complex. The primary technical challenge is to harvest cumin efficiently while avoiding damage to adjacent cotton plants and plastic mulch [12]. Cumin belongs to the Apiaceae family, and several close relatives are root–rhizome economic crops; thus, design insights from root–rhizome crop harvesters may be informative [13]. For example, Zhang [14] developed a self-propelled 37 combine harvester that excavates root–soil composites and transfers them via multi-stage conveyors to the collection hopper. The Huanglian (Coptis) harvester developed by Li [15] incorporates a root–stem separation device designed based on the material’s physical properties; it uses flexible flat-belt clamping and conveying and achieves root–stem separation and collection through cutting. Shao [16] proposed a carrot combine harvester that employs digging and crop guiding devices to convey material horizontally to the harvesting mechanism, where the tops are cut and the roots are delivered to the collection box. To conclude, the aforementioned studies, despite targeting different crops, constitute significant contributions to crop harvesting technology. Their findings provide a valuable frame of reference for the design of the cumin harvester in the present study. Nevertheless, for the specific cotton–cumin intercropping system, efficient, dedicated harvesting solutions remain lacking [17,18]. Existing devices are largely designed for single crops and cannot be directly applied to cumin’s agronomic requirements, material properties, and spatial distribution under composite planting [19,20]. Therefore, specialized harvesting equipment tailored to the cotton–cumin intercropping model is urgently needed to achieve efficient, low-damage mechanized harvesting.

Based on current cotton–cumin intercropping practices, we measured the basic physical parameters of cumin plants at harvest and conducted design research with the header as the harvester’s core component. Building on this, we experimentally analyzed how key factors influence cumin-harvesting performance and identified the optimal parameter combination. Field trials were conducted to validate the reliability of the optimal parameter set and to analyze the operating mechanism of the harvesting process. This study was designed to tackle the problem of low harvesting efficiency caused by the lack of specialized mechanization for cumin within cotton cumin intercropping systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Agronomy of Cumin Under Intercropping and Measurement of Plant Parameters

Agronomic Practices for Cumin in the Intercropping System

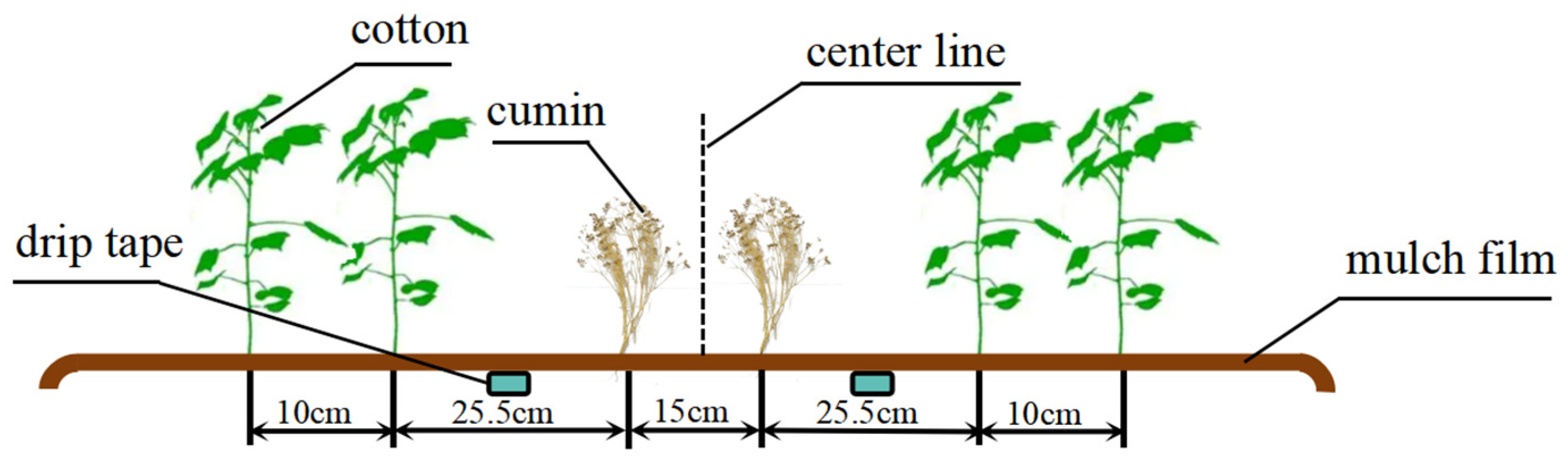

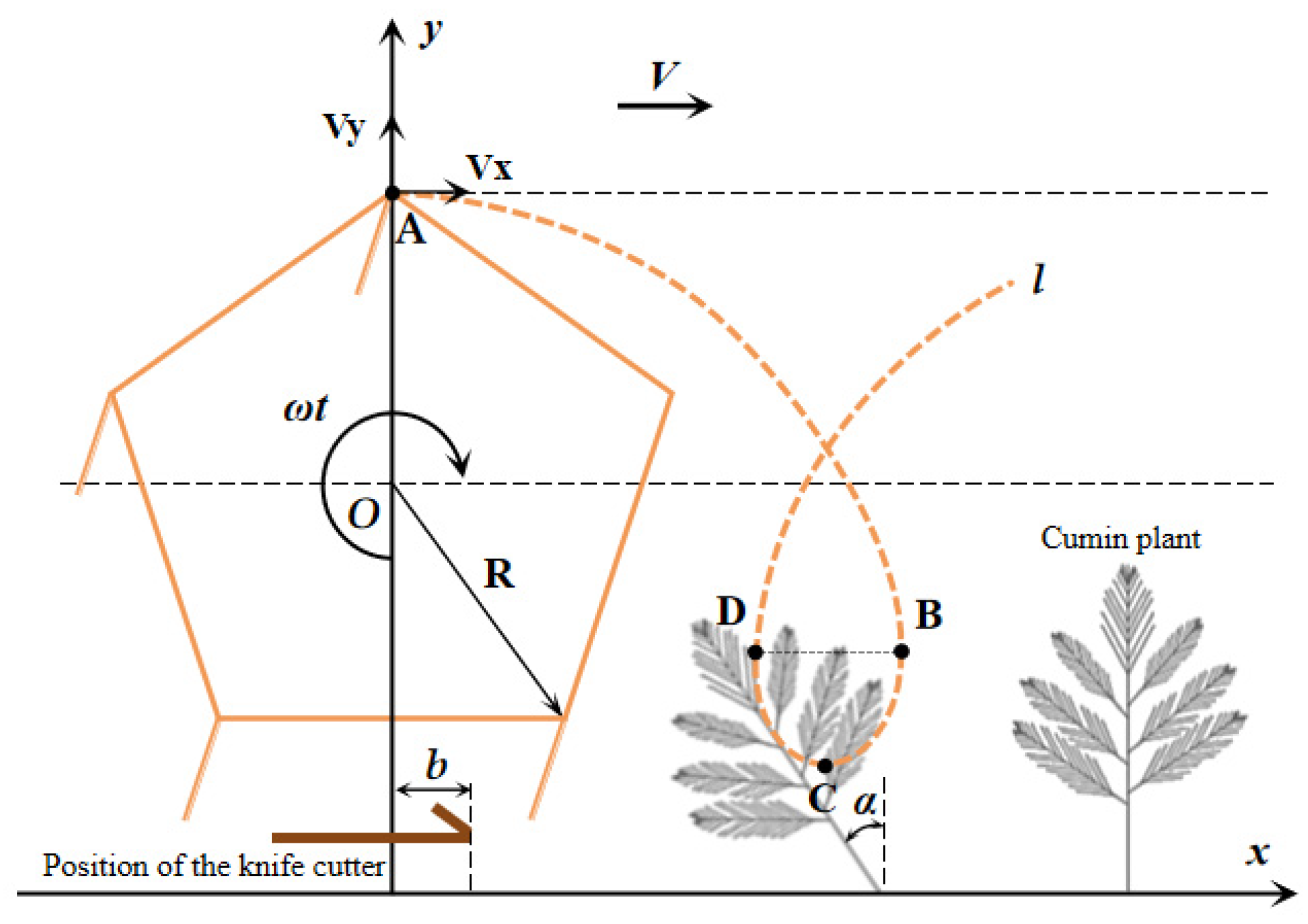

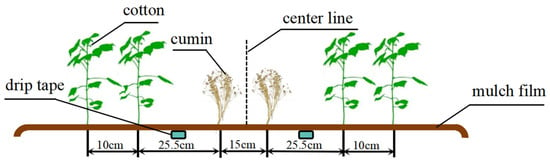

The cultivation cycle of cumin, sown in March and harvested in June, is completed prior to the primary growth and harvesting stages of cotton, which is sown in April and harvested in September. Intercropping sites are characterized by flat terrain, moderate-to-high soil fertility, and soils with good porosity and drainage. Figure 1 illustrates the agronomic layout of cotton–cumin intercropping. The planting parameters were: cotton cultivated on 1.25 m wide plastic mulch; one intercropped row arranged with a 35 + 25 mm offset; a cotton row-spacing configuration of 66 + 10 mm with four rows per bed; and a furrow center-to-center distance of 1.52 m [21].

Figure 1.

Agronomic schematic of cotton–cumin intercropping.

2.2. Measurement of Physical Parameters of Cumin Plants

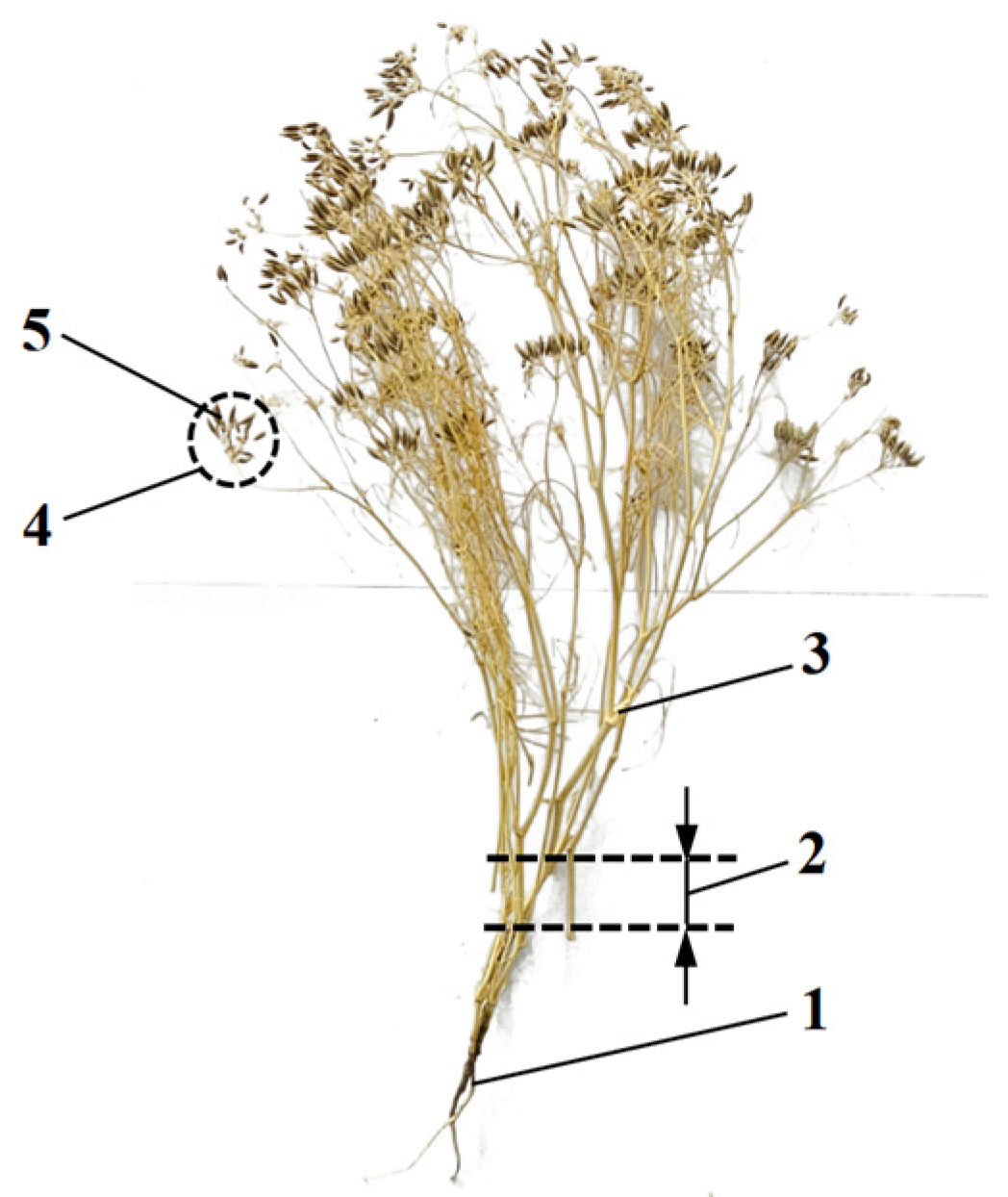

Mature cumin was sampled on 20 May 2025. Ten replicate sample sets were collected; after oven-drying tests, the mean moisture content was 17.5%. Cumin plants comprise roots, stems, inflorescences, and fruits. The fruits are borne in umbel-like inflorescences, and the root crown lies 2–4 cm below the soil surface, as illustrated in Figure 2. To inform the design of the cutting and harvesting assemblies, 100 cumin plants at harvest were selected, and root length, root–stem diameter, root–stem length, and root shear force were measured; the results are shown in Table 1. During cutting, to prevent scraping damage to the plastic mulch, the cutting height was set 7–10 cm above the root crown.

Figure 2.

Schematic of a cumin plant. 1: Root; 2: Cutting zone; 3: Stem; 4: Inflorescence; 5: Cumin fruits.

Table 1.

Structural characteristic parameters of cumin plants.

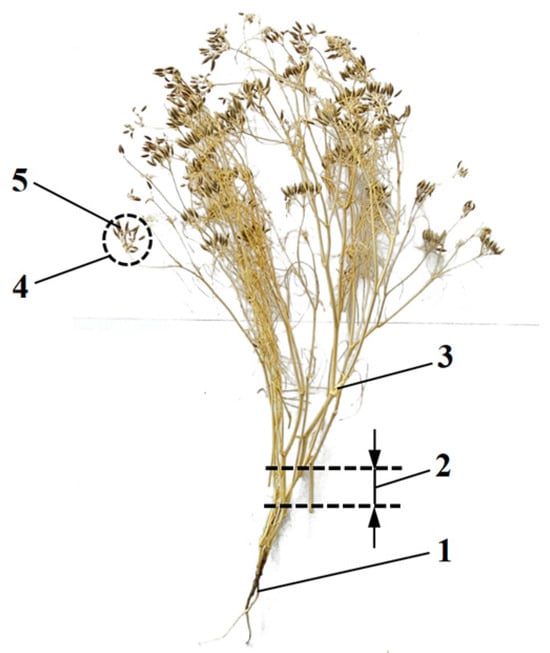

2.3. Overall Architecture and Operating Principles

2.3.1. System Architecture

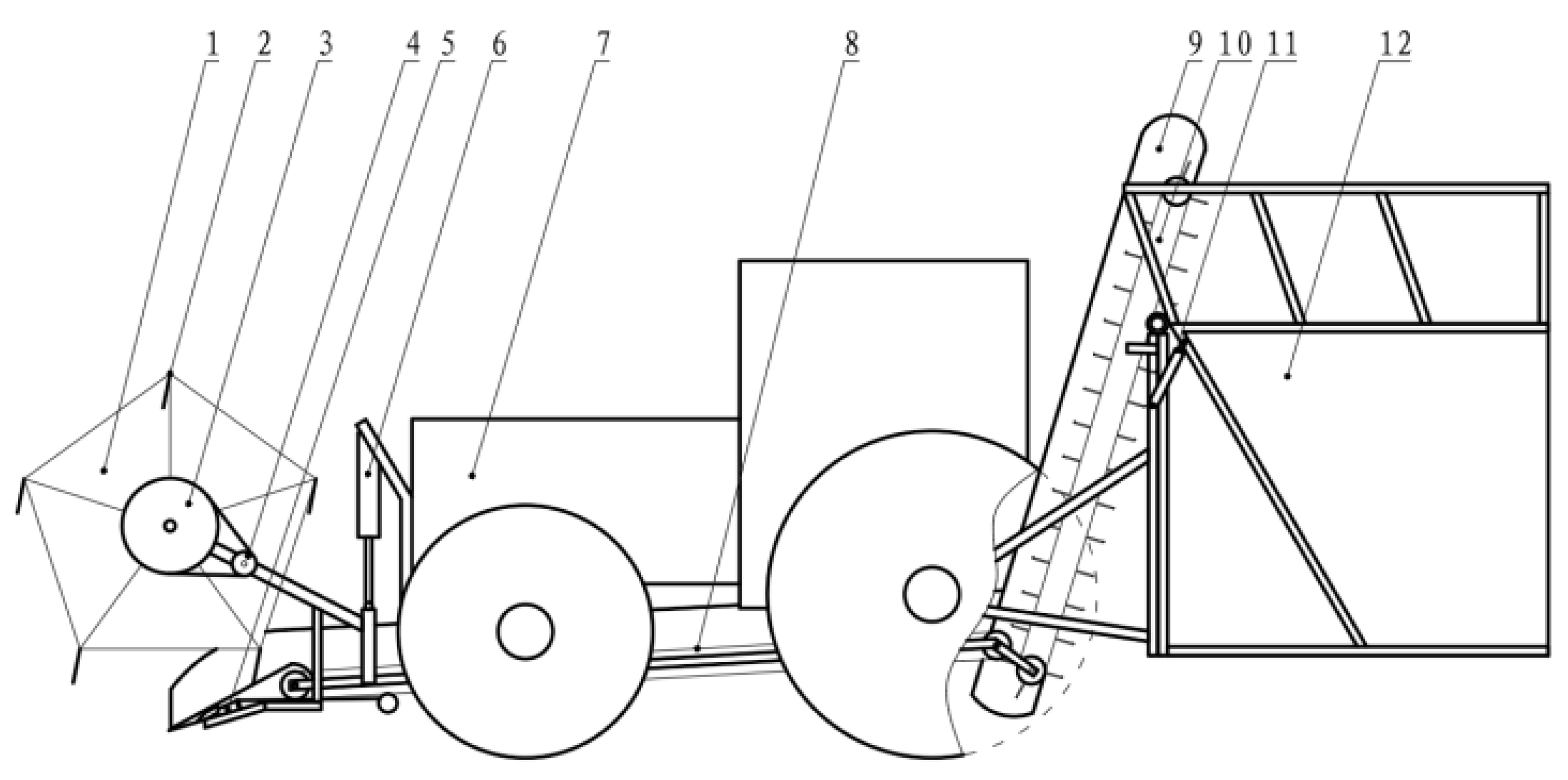

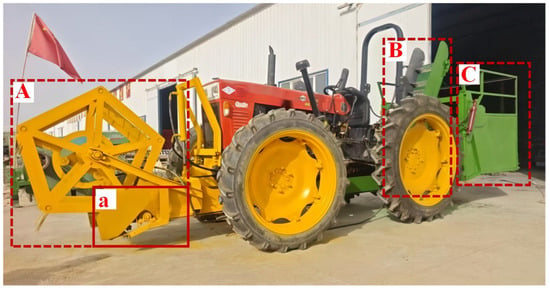

As shown in Figure 3 (structural schematic of the cumin harvester), the intercropping-oriented machine comprises a reel with spring tines, a large sprocket, a hydraulic motor, a cutter assembly, a header-lift hydraulic cylinder, a tractor, a primary conveyor belt, baffle plates for the elevating conveyor, an elevating conveyor, an unloading hydraulic cylinder, and a collection bin. The cutter assembly consists of a crop divider, a reciprocating cutter bar, a linkage mechanism, and a hydraulic motor.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the cumin harvester. 1: Reel; 2: Spring tines; 3: Large sprocket; 4: Hydraulic motor; 5: Cutter assembly; 6: Header-lift hydraulic cylinder; 7: Tractor; 8: Conveyor belt; 9: Elevating conveyor baffle; 10: Elevating conveyor; 11: Unloading hydraulic cylinder; 12: Collection bin.

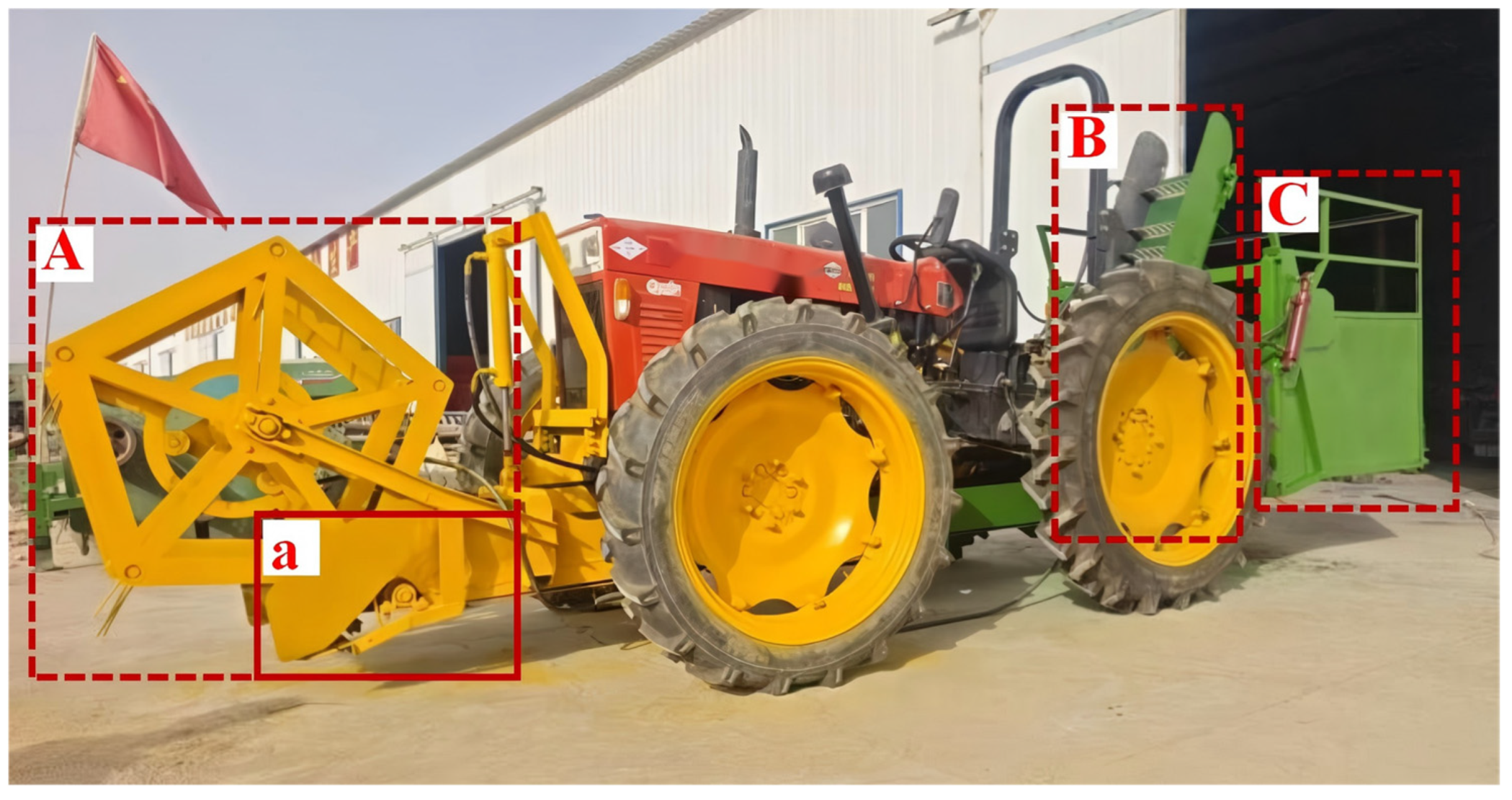

2.3.2. Operating Principles

During operation, the cumin harvester is powered by the tractor’s hydraulic system: rotating components are driven by hydraulic motors, while lifting motions are actuated by hydraulic cylinders. The workflow is shown in Figure 4. Zone A is the header section, where a hydraulic motor drives the reel. The reel both supports the cumin plants and deflects them inward toward the header. The inward-directed stems are cut by the reciprocating cutter bar (label “a” in Figure 4) and then further guided by the reel into the conveying section [22,23]. Zone B comprises a two-stage conveyor system: a horizontal conveyor transfers the cut cumin rearward, and an elevating conveyor carries it upward before discharging it into the collection bin in Zone C. The collection bin features a bottom-opening design; once full, it can be unloaded at a designated location, after which the machine resumes harvesting.

Figure 4.

Photograph of the cumin harvester (prototype). A: Header Unit (a: Cutterbar); B: Conveying System; C: Collection Bin.

2.4. Structural Design and Calculations of the Header

To enable high-quality, high-performance harvesting under the intercropping system, we focused on the header as the core research component and carried out design and parameter calculations for the harvester’s key modules, thereby establishing the theoretical foundation for subsequent studies.

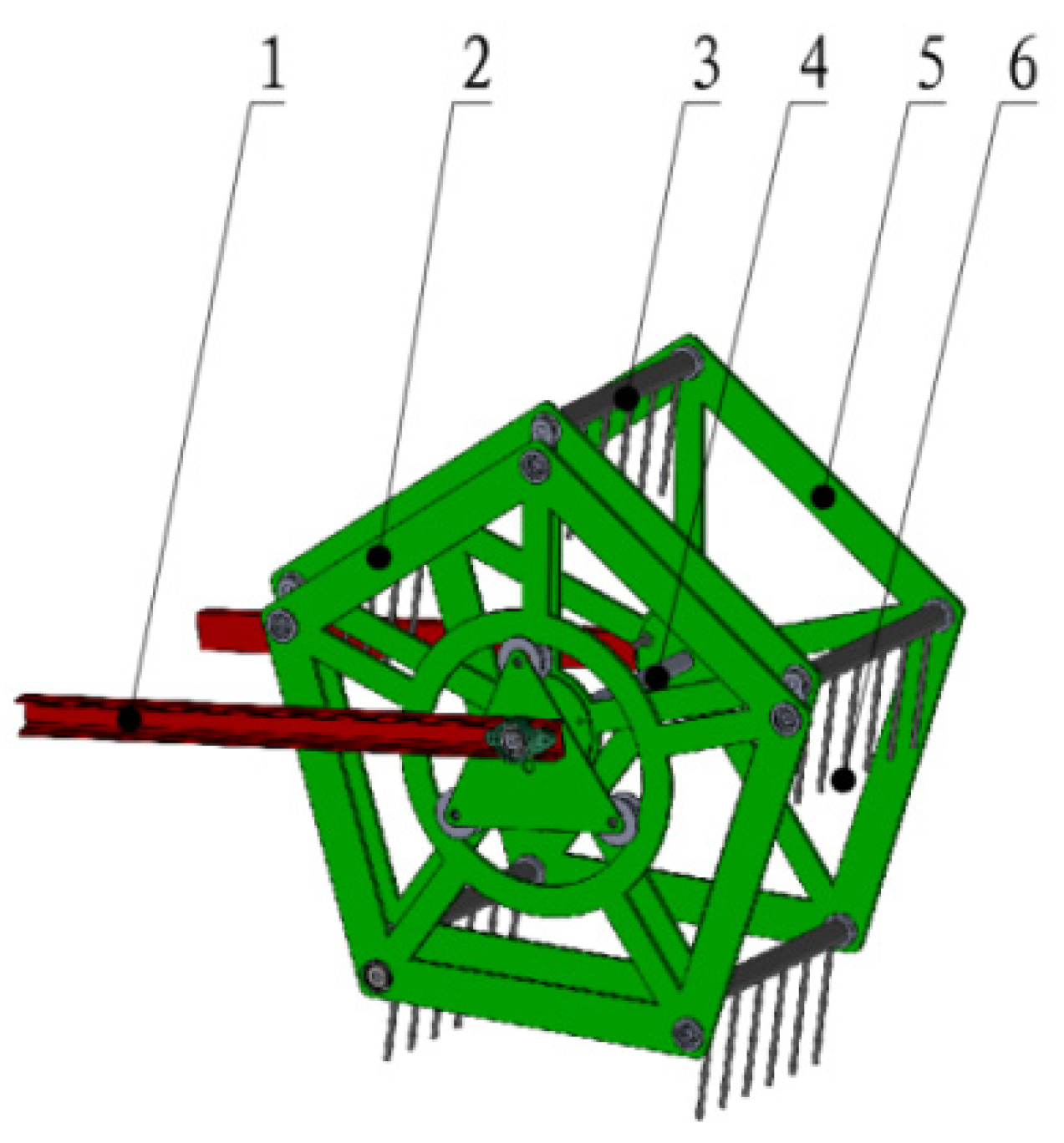

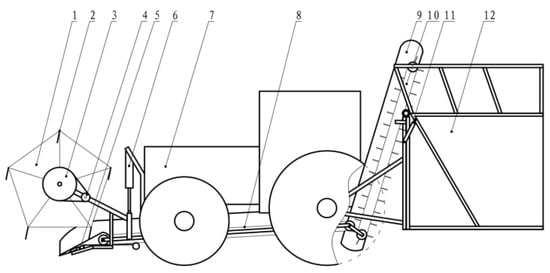

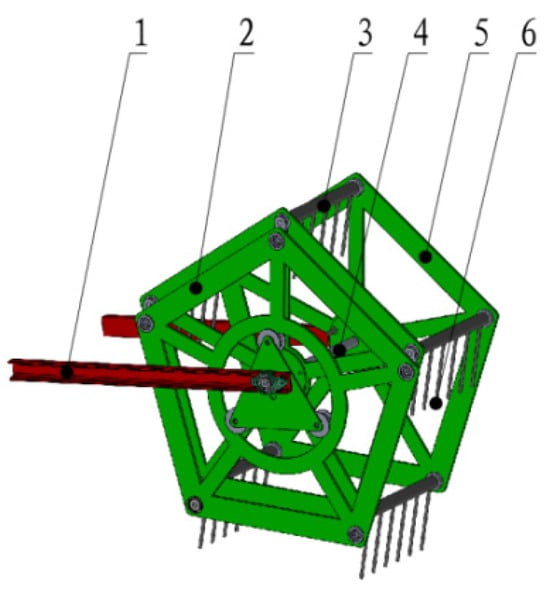

2.4.1. Structural Design and Calculations of the Reel

Based on the physical parameters measured in Section 2.2 and the traits of cumin—namely its relatively large umbel diameter and low seed-shattering propensity at harvest—the reel was designed with a five-bat eccentric configuration. Its principal components are the reel shaft, side plates (spiders), bat arms (spokes), crank, eccentric ring, and spring tines, as shown in Figure 5. Considering the morphological characteristics of cumin and following the structural design approaches of Chen Wentao [24,25,26], the side plates evenly space the reel bats; spring tines are uniformly mounted on each bat, and the tines on adjacent bats are staggered to maximize crop-gathering capacity. The key design parameters of the reel are its diameter, working width, and rotational speed.

Figure 5.

Structural schematic of the harvester reel. 1: Frame; 2: Eccentric side plate (spider); 3: Reel bat; 4: Main shaft; 5: Main side plate (spider); 6: Spring tines.

Drawing on the agronomic specifications for cumin under intercropping described in Section 2.2, the cumin row spacing is 150 mm and the minimum distance between cumin and cotton rows is 255 mm. Because harvesting must be performed within the cotton inter-row, the reel was specified with a working width of 440 mm, a radius of 520 mm, spring tine length of 120 mm, and tine spacing of 50 mm to maintain recovery while minimizing damage to cotton seedlings.

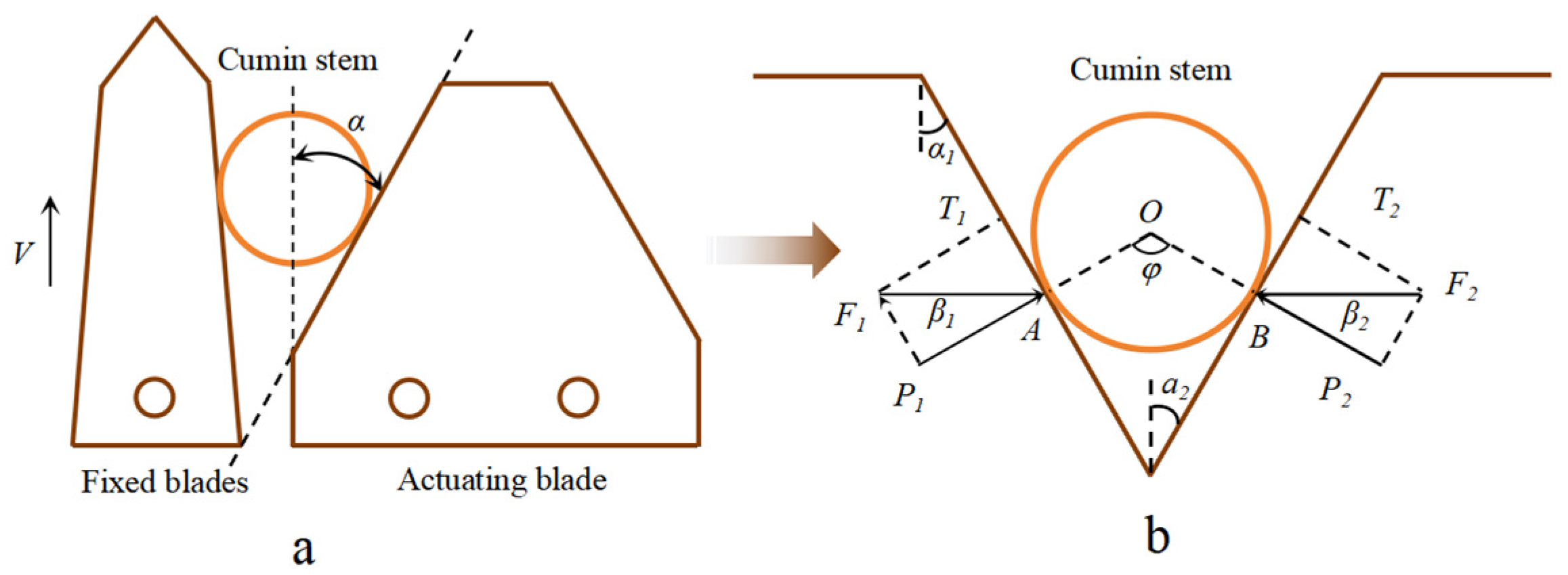

2.4.2. Cutter-Bar Design and Parameter Determination

According to [27], for reliable cutting, the moving and fixed blades must clamp the stem effectively to prevent sliding or damage, thereby ensuring that shearing occurs and that it is stable and continuous. The angle α between the moving blade and its symmetry line is defined as the entry (cutting) angle. When the moving blade translates horizontally, the angle between the blade edge and its trajectory is the cutting angle, which governs the resistance encountered during stem cutting. As α increases, cutting resistance decreases; however, if α becomes too large, the stem may slip off the blade edge. Therefore, α should be maintained within an appropriate range to ensure stable clamping.

As shown in the force diagram for a stably clamped cumin stem (Figure 6), only points A and B carry load during operation. If the blade is idealized, the stem is subjected solely to normal forces P1 and P2, under which it would slide out of the cutting edge. In practice, however, the resultant force F1 is deflected inward by an angle α1. Consequently, at force equilibrium, F1 and F2 act as a pair of opposing, colinear forces that maintain stable clamping.

Figure 6.

Force analysis of cumin stem–cutter interaction. (a): schematic of a cutter severing a cumin stem; (b): force diagram for a stem under stable clamping. o is the center of mass of the fennel plant; F1 and F2 are the normal reaction forces; θ is the angle between the lines of action of the two normal reaction forces, F1 and F2; γ is the angle between the resultant force R and a specified direction; φ is the semi-angle of the cutter blade; P1 and P2 are the tangential friction forces; R1 and R2 are the resultant forces at the contact points; T1 and T2 are the clamping forces applied by the cutter blades; β1 and β2 are the angles of friction.

As α1 and α2 increase, the friction angles β1 and β2 also increase, and the contact points shift inward. From a statics perspective, the deflection angles of the resultant forces F1 and F2 cannot exceed the friction angles β1 and β2.

According to Equation (1), the condition for stable clamping of the stem is obtained. The results indicate that, when α1 = 29° and α2 = 6–15°, the reciprocating cutter bar achieves the best cutting performance.

2.5. Field Testing of the Complete Cumin Harvester

2.5.1. Materials and Equipment

The field experiments were conducted on 25 May 2025 at the experimental field in Yuli County, Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The experimental field was characterized through the following measurements: total area, topographic features (uniformity), and cultivation attributes. The cultivation attributes, including crop variety and planting pattern, were recorded. Plant spacing and row spacing were measured using the five-point sampling method and averaged. Crop characteristics were assessed by sequentially sampling ten plants to determine the natural height and the lowest pod-bearing height (distance from the base of the lowest seed-bearing branch to the mulch film surface) for each plant. The cumin yield per square meter was determined by randomly selecting five 1 m2 quadrats and calculating the average. The selected field was representative, with flat terrain and no obstructions. The designated test zone was 30 m in length, with a minimum 5 m preparation area at each end. The width was sufficient to meet the operational requirements of the harvester. After harvesting, the lost cumin seeds within the two (forward and return) test zones were collected separately, cleaned of impurities, and weighed. Prior to harvesting, five random sampling points were selected within the test zone, each comprising a 1 m2 quadrat. Within each quadrat, the total number of undamaged cotton seedlings was counted. Immediately following the harvesting operation, the number of damaged cotton seedlings within the same quadrats was recorded. Damage was defined as plants with a broken main stem, being severely lodged and irrecoverable, or having exposed root systems. The test materials were cumin cultivar No. 3 and cotton cultivar Xinmian 12. Harvester reel speed (header), forward speed, and stubble height were selected as experimental factors, with cumin recovery rate and cotton stand damage rate as performance metrics. The experimental equipment included the self-developed cumin harvester, an electronic scale (50 kg capacity, 0.01 kg resolution), an anemometer (0–40 m/s), a stopwatch, and a tape measure.

2.5.2. Methods and Performance Indices

Relevant literature indicates that in the mechanized harvesting of small-stature crops, stubble height, harvester reel speed, and forward speed of the machinery are key influencing factors [28,29]. These parameters are central to improving harvesting efficiency and reducing damage rates. Therefore, in this study, these three factors were used to conduct single-factor tests to analyze their impact on cumin-harvesting efficiency and the damage rate of cotton crops. During the field test, the cumin cutting wheel of the machinery was kept aligned with the cumin planting area, and the cutter position was adjusted to control stubble height (10, 30, 50, 70, 90, 110 mm), forward speed (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 km/h), and harvester reel speed (13, 18, 23, 28, 33 r/min). After the test, the cumin-harvesting rate and the average damage rate of cotton plants were used as test indicators.

Cumin harvest rate: after harvesting the designated plot, impurities were removed and the cumin collected in the bin was weighed; damaged plants within the plot were also gathered, cleaned, and weighed.

Average damage rate of cotton plants: five sampling points were randomly selected within the measurement area. Each quadrat measured 1 m2; within each selected quadrat, the total number of intact cotton seedlings was counted. Immediately after the target crop was harvested, the number of cotton seedlings damaged by the operation—defined as main-stem breakage, severe lodging with no recovery, or exposed roots—was recorded within the same quadrats. To reduce error, three field replicates were conducted and averaged. The harvest rate was calculated using Equation (2), the damage rate for each quadrat using Equation (3), and the average damage rate using Equation (4).

where Z is the harvest rate, %; F1 is the mass of missed (uncut) cumin, kg; F2 is the mass of cumin not collected, kg; and F3 is the mass of cumin collected, kg.

where P is the damage rate for each quadrat, %; Nd is the number of damaged cotton seedlings in the quadrat, plants; Nt is the total number of cotton seedlings in the quadrat, plants; and Pa is the average damage rate, %.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single-Factor Experiments and Results Analysis

Each single-factor experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the results are presented as the mean value.

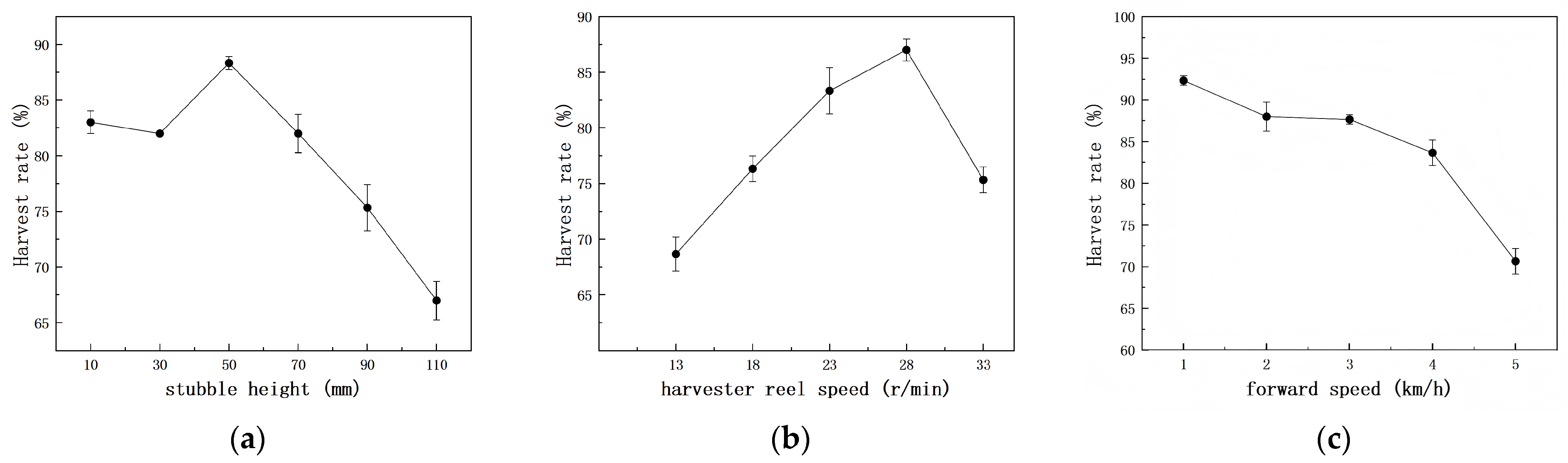

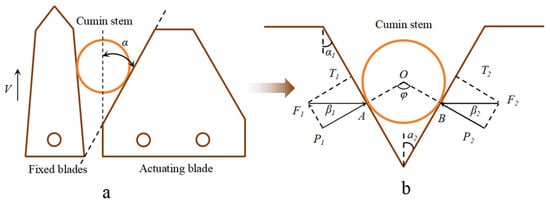

Figure 7 shows effects of stubble height, harvester reel speed, and forward speed on cumin harvest rate. Figure 7a shows the effect of stubble height on cumin harvest rate: as stubble height increases, the harvest rate rises first and then falls, reaching a peak at 50 mm. Figure 7b shows the effect of harvester reel speed on cumin harvest rate: with increasing harvester reel speed, the harvest rate increases gradually, achieves the best performance at 28 r/min, and then drops sharply. Figure 7c shows the effect of tractor forward speed on cumin harvest rate: as forward speed increases, the harvest rate declines slowly; once speed exceeds 4 km/h, it decreases rapidly.

Figure 7.

Analysis of factor effects on cumin harvest rate. (a) Effect of stubble height on cumin harvest rate. (b) Effect of harvester reel speed on cumin harvest rate. (c) Effect of forward speed on cumin harvest rate.

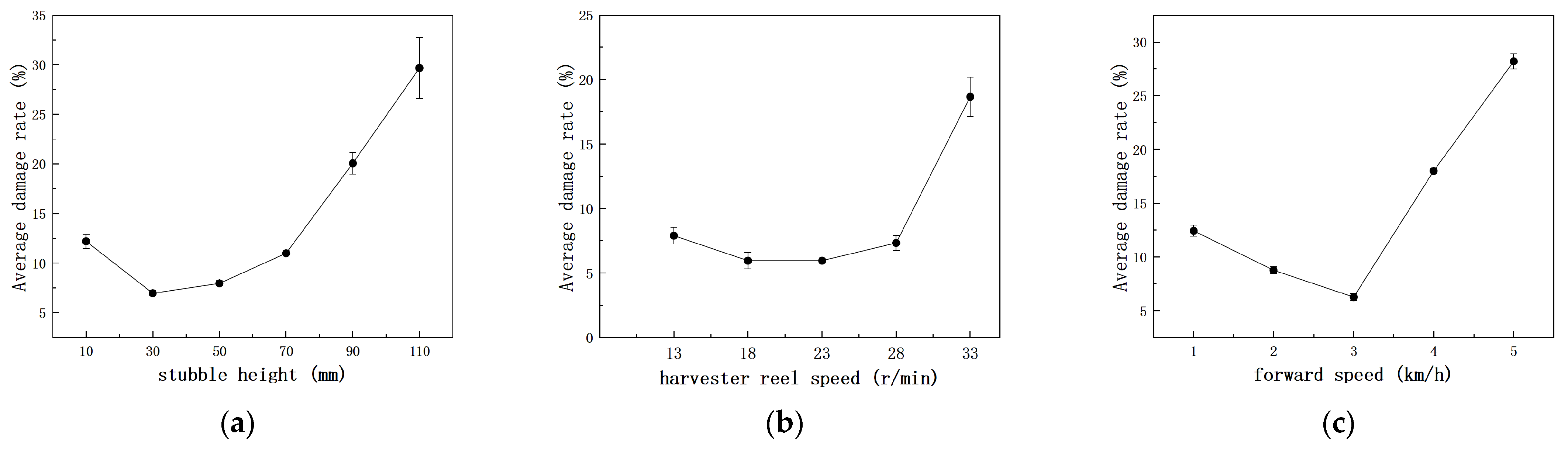

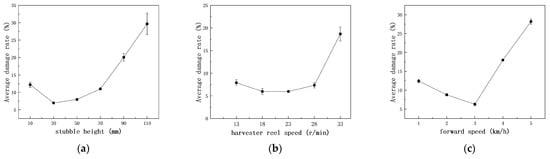

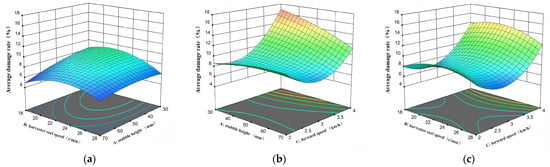

Figure 8 shows effects of stubble height, harvester reel speed, and forward speed on the average damage rate of cotton plants. Figure 8a shows the effect of stubble height on the average damage rate: the average damage rate decreases initially and then increases; it remains relatively low at stubble heights of 30–50 mm. Figure 8b shows the effect of harvester reel speed on the average damage rate: within 18–28 r/min, the average damage rate is low and stable. Figure 8c shows the effect of forward speed on the average damage rate: the cotton damage rate decreases at first and then increases, reaching its minimum at 3 km/h. When forward speed exceeds 3 km/h, the average damage rate rises sharply.

Figure 8.

Analysis of factor effects on the average damage rate. (a) Effect of stubble height on the average damage rate. (b) Effect of harvester reel speed on the average damage rate. (c) Effect of forward speed on the average damage rate.

3.2. Multi-Factor Experiments and Results Analysis

3.2.1. Experimental Methods

Based on the single-factor results above, harvester reel speeds of 18, 23, and 28 r/min and stubble heights of 30, 50, and 70 mm were selected. Although the highest harvest rate occurred at a forward speed of 1 km/h, forward speeds of 2, 3, and 4 km/h were chosen to balance recovery with field capacity. Under these settings, a factorial combination experiment was conducted to evaluate cumin-harvesting efficiency and the average cotton damage rate. The coded factor levels are shown in Table 2. The experimental results are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Coding of experimental factors.

Table 3.

Experimental design and results.

3.2.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

According to the ANOVA of the quadratic models for harvest rate and average damage rate (Table 4), all three factors have highly significant effects on cumin harvesting. For harvest rate, a comparison of the p-values in the ANOVA table reveals the order of significance as B > A > C. The relative importance is: forward speed > stubble height > harvester reel speed. For average damage rate, forward speed and stubble height have significant effects, whereas harvester reel speed has a relatively small effect; a comparison of the p-values in the ANOVA table reveals the order of significance as B > A > C. The importance ranking is likewise: forward speed > stubble height > harvester reel speed.

Table 4.

ANOVA of the quadratic model for harvest rate and average damage rate.

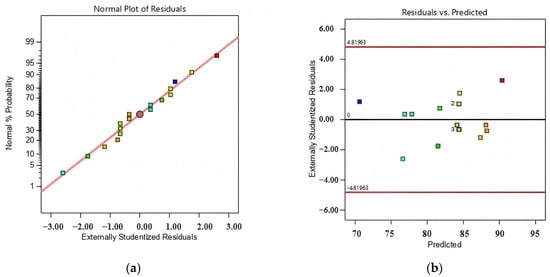

Figure 9a,b show the residual diagnostic plots for the harvesting rate in the test indicators. The residuals of the model conform to the assumptions of normal distribution, homogeneity of variance, and independence. Figure 9b showing the residuals vs. predicted values plot reveals an exceptionally large studentized residual for the 12th test. This anomaly was caused by a malfunction in the material lifting system during the experiment and is considered a special variation, so it was retained. Comprehensive analysis indicates that the model fits well, thereby proving the reliability of the ANOVA results.

Figure 9.

(a): Normal Probability Plot; (b) Residuals vs. Predicted Plot (Harvest rate).

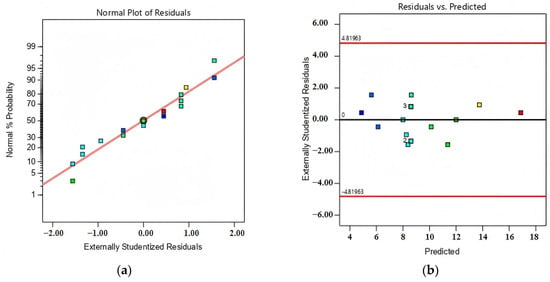

Figure 10a,b show the residual diagnostic plots for the average damage rate in the test indicators. The residual diagnostics indicate that the residuals of the model conform to a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, demonstrating that the established model is appropriate and effective.

Figure 10.

(a): Normal Probability Plot; (b) Residuals vs. Predicted Plot (Average damage rate).

In the formula: A represents the stubble height; B represents the harvester reel speed; C represents the forward speed.

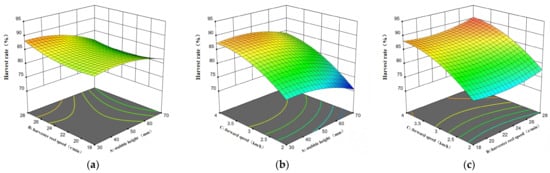

As shown in Figure 11a, when stubble height is fixed at 30 mm, reducing harvester reel speed causes the harvest rate to decrease and then increase, with the overall variation remaining modest. As stubble height increases, the harvest rate is initially stable and then shows a slight decline. As shown in Figure 11b, at low stubble heights, increasing forward speed improves the harvest rate; at higher stubble heights, increasing forward speed likewise raises the harvest rate. Overall performance is best at stubble heights of 30–40 mm. Under their interaction, lower stubble height combined with higher forward speed improves harvest rate. Figure 11 c. Across harvester reel speeds, increasing the tractor’s forward speed leads to a continuous rise in harvest rate, with the best performance occurring at a harvester reel speed of 28 r/min.

Figure 11.

Three-factor interaction effects on harvest rate. (a) Effects of harvester reel speed and stubble height on the harvest rate. (b) Effects of forward speed and stubble height on the harvest rate. (c) Effects of forward speed and harvester reel speed on the harvest rate.

As shown in Figure 12a, at a harvester reel speed of 18 r/min and a stubble height of 70 mm, cotton plant damage is minimal; as stubble height decreases, the average damage rate increases progressively. At a harvester reel speed of 28 r/min, changes in stubble height have little effect on the average damage rate. This indicates that stubble height is the primary determinant of cotton damage, whereas harvester reel speed plays a minor role. Figure 12b (stubble height × forward speed) shows that, at 2 km/h, increasing stubble height produces no clear trend in the average damage rate. When forward speed rises to 2.5–3 km/h, the trend is similar, but the overall average damage rate decreases. As speed increases further to 3.5–4 km/h, higher stubble height leads to a gradual increase in the average damage rate. This suggests that both factors affect cotton damage during operation: higher stubble height draws more cotton plants into the cutting zone, while higher forward speed intensifies impacts and rolling by the header, thereby increasing damage. Figure 12c showing harvester reel speed × forward speed indicates that, at a fixed forward speed, decreasing the harvester reel speed causes the average damage rate to rise and then fall. Forward speed exerts a stronger influence: at a constant harvester reel speed, increasing speed first slightly reduces the average damage rate and then increases it sharply.

Figure 12.

Three-factor interaction effects on the average damage rate. (a) Effects of harvester reel speed and stubble height on the average damage rate. (b) Effects of forward speed and stubble height on the average damage rate. (c) Effects of forward speed and harvester reel speed on the average damage rate.

To obtain the optimal operating parameters, we formulated a constrained optimization with the goals of maximizing harvest rate and minimizing average damage rate, as defined by Equations (7) and (8), and solved it in Design-Expert over the specified factor ranges.

Objective functions:

Constraints:

The optimized settings were: stubble height 32.6 mm, harvester reel speed 28 r/min, and forward speed 3.25 km/h. Under these conditions, the expected harvest rate is 89.54% and the mean cotton damage rate is 7.33%.

3.2.3. Field Validation of Harvesting Performance

To verify the feasibility of the optimal parameter combination, a field test for cumin harvesting was conducted, as shown in Figure 13. The field test results in Table 5 indicate that the average harvesting rate for the five repeated tests was 88.2% and the average damage rate was 5.6%. The response surface methodology predicted the optimal working parameter values to be a harvesting rate of 89.54% and an average damage rate of 7.33%. The relative errors between the test values and the predicted values were 1.34% and 1.73%, respectively, both at low levels.

Figure 13.

Field trial. (a) depicts the preliminary/preparatory phase; (b) illustrates the formal experiment.

Table 5.

Field harvest test results.

Currently, although there are no specific national industry standards for the harvesting rate and average damage rate of fennel harvesting machinery, from the perspective of practical economic benefits, and in consideration of the requirements of farmers and project units, a harvesting rate > 82% and an average damage rate < 8% are set as the acceptable performance indicators. The results of this test were better than these indicators, and the errors between the predicted values and the test values were within the allowable engineering range, indicating that the optimized parameter combination has good feasibility and practicality.

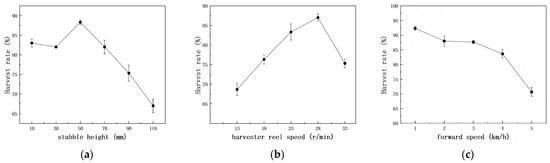

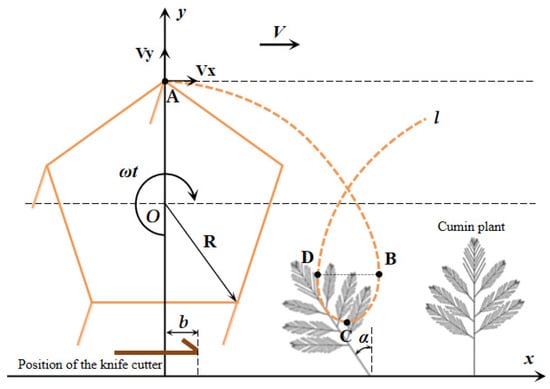

3.3. Kinematic Analysis of the Harvesting Process

Elucidating the kinematics of the cumin harvester is fundamental to achieving efficient harvesting. Analysis of the operational process revealed that the reel’s kinematic state directly governs harvest performance on cumin plants. Following Yiren Qing and Kuizhou Ji [30,31], we introduced the reel index (λ) as a metric for theoretical analysis; its definition is given in Equation (9). Substituting the optimal parameter set into Equation (9) yields λ = 1.69, which is consistent with findings reported for harvesting devices in short-stem crops [32].

In Formulas (9)–(11), (λ) is the harvester reel speed ratio; R is the reel radius; ω is the angular velocity; Vm is the tractor forward speed; Vx is the absolute horizontal velocity component; dxA is the horizontal displacement of point A; dt is the corresponding time interval; ωR is the linear velocity at point A; ωt is the angular displacement per unit time; Vy is the absolute vertical velocity component; dYA is the vertical displacement of point A.

On the one hand, with a forward speed of 3.25 km/h and a harvester reel speed of 28 r/min (Figure 14 reel–tine trajectories), the longitudinal component of tine–plant interaction is optimized, avoiding repeated impacts or entanglement and thereby reducing shattering damage. The axial component ensures that the tines effectively hook and support the cumin stems, guiding them smoothly to the cutter for severing. On the other hand, multi-plot measurements showed that cumin plant height ranged from 172.5 to 257.2 mm, with the center of mass located at roughly one quarter of the total plant height above the root. After the reel supports the plants, the remaining stem length corresponds to the safe stubble height. The optimized stubble height of 32.6 mm lies below the center of mass, ensuring safe clearance between the cutter and the plastic mulch while meeting agronomic requirements for mechanized harvesting. In summary, the optimal parameter set for the cumin harvester not only satisfies the theoretical requirements associated with the reel index but also demonstrates strong adaptability and reliability in field operation, providing both a theoretical basis and a practical reference for designing and optimizing harvesters for other small-seeded crops.

Figure 14.

Reel–tine trajectory of the cumin harvester. A represents the reel finger; l is the motion trajectory of reel finger; B, C, and D represent the three phases of contact between point A and the cumin plant; R is the radius of the reel; O is the rotational center (axis) of the reel; ωt is the angular displacement per unit time; V is the (machine’s) forward velocity; Vx is the absolute horizontal velocity component; Vy is the absolute vertical velocity component; b is the displacement distance of the cutter bar; α is the leaning angle induced by the reel finger.

In field operation, the developed cumin harvester exhibited excellent harvesting performance, markedly improving harvest quality and overall productivity. However, mechanized cumin harvesting is susceptible to dynamic soil behavior [33] and terrain effects, which can induce vibration and speed fluctuations, thereby degrading the accuracy of header positioning. Although these factors introduce some discrepancy between the predicted and measured average damage rates, the deviations remain within permissible experimental error. To further enhance the harvester’s efficiency, we recommend two avenues of improvement [34,35]: “mechanical stability optimization” and “enhanced plant monitoring capabilities”. On the one hand, refining the damping/suspension and speed-control systems could suppress machine vibration; on the other, incorporating real-time monitoring and feedback control—such as using inertial measurement units (IMUs) [36] to compensate for terrain undulations—would provide technical and theoretical support for agricultural operations in complex field conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study developed a cumin harvester tailored to the prevailing cotton–cumin intercropping system. focusing on the header as the core module. A reciprocating cutter severs the plants at the crown to separate roots and stems, after which the reel guides the plants to the conveying system; a two-stage conveyor then transfers the material to the collection hopper.

Based on the header’s operating process, one-factor trials established the practical ranges: stubble height 30–70 mm, harvester reel speed 18–28 r/min, and forward speed 2–4 km/h. An orthogonal-regression combination design coupled with response surface analysis identified the optimal settings: stubble height 32.6 mm, harvester reel speed 28 r/min, and forward speed 3.25 km/h. Field validation yielded mean values of 88.2% for harvest rate and 5.6% for the average damage rate, with relative errors versus model predictions of 1.34% and 1.73%.

The harvesting process of the reel was subjected to a kinematic analysis, and this configuration prevents repeated impacts in the longitudinal direction, reducing shattering damage, while in the axial direction it provides secure support and smooth guidance of the stems to the cutter. Meanwhile, the optimized stubble height lies below the plant center of mass. This study can provide both theoretical and practical references for the design and optimization of harvesters for similar small-stature crops in intercropping systems.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.L.; validation, X.Y. and K.L.; investigation, Z.C. and N.Z.; resources, H.L.; data curation, X.Y. and Y.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, H.L.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, R.J.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Autonomous Region Financial Support Project for Agricultural Mechanization Development, Research and Development, Manufacturing, Promotion, and Application of Harvesting Equipment for Cumin Intercropping Systems and Development and Demonstration of Key Equipment for Cotton–Cumin Co-sowing (Grants CF2025-07 and 2024ZB03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Zhi Chen is from Xinjiang ZhiChuang Environmental Technology Co., Ltd., where he serves as General Manager. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tian, X.J. The Study and Evaluation on Ecological Adaptability of CuminGermplasm Resources in Southern Xinjiang. Master’s Thesis, Tarim University, Tumuqike, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saranya, M.; Sangeetha, S.; Shanmugam, P.; Dhananchezhiyan, P.; Vanitha, K.; Thirukumuran, K. Assessment of mechanized sown cotton-based intercropping systems: Impact on yield, efficiency and profitability. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Kumar, S. Cumin (Cuminum cuminum L.): Present breeding status and future prospective. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 230, 121117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Ge, J.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Niu, K.; et al. Summary report on cotton bumper harvest in Xinjiang oasis in 2024. China Cotton 2025, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, R.; Zuo, Q.; Shi, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z. Water use efficiency and benefit for typical planting modes of drip-irrigated cotton under film in Xinjiang. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2013, 29, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, K.; Liu, G. Green and Efficient Cultivation Techniques of Cumin Intercropping Peanut. China Seed Ind. 2024, 10, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Li, S. Cultivation Technique of Cotton Intercropping with Fennel. China Agric. Mach. Equip. 2024, 2, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Tan, C. Influencing Mechanism of High Quality Development of Agricultural Mechanization—Based on Empirical Data from 14 Prefectures (Cities) in Xinjiang. Anhui Nongye Kexue 2024, 52, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, S.; Bai, K.; Zhang, J.; Guo, G. Review and Development Trend of Mechanized Cotton Stalk Harvesting Technology in Xinjiang Cotton Region. Agric. Mech. Res. 2025, 47, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sahoo, P.K.; Kushwaha, D.K.; Mani, I.; Pradhan, N.C.; Patel, A.; Tariq, A.; Ulah, S.; Soufan, W. Force and power requirement for development of cumin harvester: A dynamic approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowojola, C.O.; Faleye, T.; Agbetoye, L. Development and performance evaluation of a leafy vegetable harvester. Int. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Soil Sci. 2011, 1, 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Ma, L.; Zhang, S. A Cotton Field Fennel Harvester for Intercropping Fennel in Cotton. China CN119769292A, 4 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C. Research and Design of Green Leafy Vegetable Harvesting Equipment. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Wang, F.; Cao, Q.; Xie, K. Trafficability Analysis and Scaling Model Experiment of Self—Propelled Panax notoginseng Combine Harvester Chassis. Nongye Jixie Xuebao 2023, 54, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Zhao, S.; Yao, L.; Zeng, B. Design and test of root and stem separating device for Coptis chinensis harvesting machine. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2025, 46, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y. Analysis of Motiom and Mechanical Properties of Digging Parts of Carrot Combine Harvester. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2024, 46, 49–54+59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.L. Study on the Matching Between Technical Parameters of Harvester and Geographical Plot Characteristics. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Effects of different planting densities on growth and yield of fennel seed-ling. Zhongguo Gua-Cai 2024, 37, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M. Regulatory Effects of Intercropping Cotton and Cumin on Root Characteristics and Yield Formation in Non-Film Cotton. Master’s Thesis, Shihezi University, Shihezi, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. Research on Innovative Design of Leek Harvester Based on Situation. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Luo, Q.; Sun, L. The cultivation technique of cumin by intercropping with water drip irrigation under cotton film in spring. Xinjiang Nongken Keji 2024, 47, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Jin, M.; Jiang, T. Design and Parameter Optimization of Variable Speed Reel for Oilseed Rape Combine Harvester. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Fang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Ye, D. Design and Simulation Analysis of Single-Disc Type Fungus Grass Stem Cutter. Mech. Electr. Technol. 2018, 06, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, A.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, D.; Wu, M. Design and Simulation Experiments of Reciprocating Cutting Tuber Removal Device for Ophiopogon japonicus. Nongye Jixie Xuebao 2023, 54, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Tang, Z.; Li, B.; Guo, X. Design of soybean header suitable for single-film harvesting in Xinjiang and analysis of grain-sweeping process. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2024, 42, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Research on the Feeding Rate Detection Technology of Combine Harvester Based on the Force Exerted by the Reel on Wheat Plant. Master’s Thesis, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Z.; Rui, Z.; Liu, X. Design and Test of Clamping Belt Cotton Straw Harvester. Nongye Jixie Xuebao 2020, 51, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, D. Modeling and Dynamic Characteristics Analysis of Synchronous Belt Transmission Mechanism in PVC Clamping and Stepping Device for Packaging Machine. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2024, 10, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, T.; Hu, L.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, W. Design and Experiment with a Double-Roller Sweet Potato Vine Harvester. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Ma, Z. Development and experiments on reel with improved tine trajectory for harvesting oilseed rape. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 206, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, R.; Xia, S.; Zheng, G. Device and Method Suitable for Matching and Adjusting Reel Speed and Forward Speed of Multi-Crop Harvesting. Agriculture 2022, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, O.A.; Dahab, M.H.; Musa, M.M.; Babikir, E.S.N. Influence of Combine Harvester Forward and Reel Speeds on Wheat Harvesting Losses in Gezira Scheme (Sudan). Int. J. Sci. Adv. 2021, 2, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, K.; Yang, S.; Han, X.; Wei, X.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, L. Design and Experiment of an Unmanned Variable-Rate Fertilization Control System with Self-Calibration of Fertilizer Discharging Shaft Speed. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Niu, X. Evaluating the navigation performance of multi-information integration based on low-end inertial sensors for precision agriculture. Precis. Agric. 2020, 22, 627–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Research on Field Information Real Time Monitoring System for Rice and Wheat Combine Harvester Based on Machine Vision. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Lu, Y.; Gao, C.; Liu, H. A fertilizer discharge detection system based on point cloud data and an efficient volume conversion algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 185, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).