1. Introduction

Producing high-quality seeds with desirable genetic, physical, and physiological traits not only directly impacts crop yield but also determines the economic viability of agricultural systems. Among physiological attributes, seed quality is primarily assessed through germination and vigor tests. Germination is essential for successful crop establishment and plant development in the field [

1]. Seed vigor reflects the ability of seeds to produce normal seedlings rapidly and uniformly, even under suboptimal environmental and storage conditions [

2]. However, conventional seed quality assessments are typically destructive, subjective, and labor-intensive. To address these limitations, remote sensing technologies have been increasingly adopted, offering non-destructive and more objective alternatives.

Vigor tests play a fundamental role in characterizing seed physiological performance, allowing the distinction between high-, medium-, and low-vigor lots. These tests assess the ability of seeds to withstand different types of stress without compromising essential attributes such as germination speed, cell membrane integrity, and the establishment of vigorous seedlings under field conditions [

3]. Therefore, the appropriate selection of vigor tests should consider not only the speed and efficiency of obtaining results, but also their ability to reliably reflect seed behavior under adverse conditions in the field or during storage [

4].

Among the most recent methods used for non-destructive evaluation of the physiological quality of seeds, the following stand out: multispectral image analysis, which has demonstrated accuracy between 90% in vigor classification [

5], Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), applied for chemical composition characterization with correlations typically between 0.60 and 0.80 [

6] and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), used to relate elemental nutrients with germination performance [

7] However, although different studies have already employed reflectance and spectral band data for soybean genotype identification or for distinguishing vigor classes [

8,

9], most focus only on binary classification tasks or restricted models, with a limited number of algorithms evaluated. Thus, a gap persists related to the use of hyperspectral reflectance of leaves and seeds for quantitative prediction of physiological attributes, such as germination, vigor, and electrical conductivity, exploring multiple models and systematic performance comparison, an approach that this study seeks to address.

Hyperspectral sensors are valuable tools for assessing biomass, productivity, and soil degradation, as they provide detailed biophysical and biochemical information about plants [

10]. In plants, spectral changes are closely linked to alterations in the photosynthetic apparatus and its performance [

11]. Techniques such as hyperspectral reflectance allow for the capture of information across the wavelengths detected by the sensor [

12]. A key advantage of this method is its non-destructive nature and its independence from ambient light variability, which minimizes errors caused by diffuse light. Consequently, using reflectance data to predict seed germination is a promising approach for obtaining rapid and accurate information compared to traditional methods.

Optical sensors are designed to record the reflectance of electromagnetic radiation at different wavelengths, covering different regions of the spectrum. The most commonly used wavelengths in agronomic and remote sensing studies correspond to the visible (400 to 700 nm), reflected infrared (700 to 3000 nm), and thermal infrared (3000 to 10,000 nm) regions [

13].

Combining hyperspectral sensing with computational intelligence, such as machine learning (ML) methods, further accelerates result acquisition. These datasets are highly dimensional and often involve complex, non-linear relationships between spectral and agronomic variables, making traditional modeling approaches like regression less effective or even impractical. Computational intelligence thus holds promise for processing such data, but the performance of each algorithm varies depending on the dataset, highlighting the need to test multiple algorithms to identify the most effective classifier [

14]. However, most sensors used in agricultural applications focus on the visible and reflected infrared regions, with emphasis on the near infrared (700 to 1300 nm) and mid-infrared (1300 to 3000 nm) due to their high sensitivity to variations in cellular structure, water content, and chemical composition of plant tissues [

15].

Studies that utilize seed reflectance in relation to seed physiological quality, or that have used hyperspectral information from leaves while the crop is still in the field to predict early physiological seed qualities, are scarce in the literature. The hypothesis is that spectral information obtained from leaves and seeds contains patterns associated with seed physiological attributes, enabling the construction of robust predictive models capable of estimating physiological quality quickly and non-destructively. In this context, the objectives of this research were: (i) to evaluate the potential of leaf and seed reflectance as predictors of soybean seed physiological quality using machine learning (ML) algorithms, and (ii) to identify which algorithm performs best in terms of predictive accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Experiment

The experiment was conducted at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Chapadão do Sul campus (18°41′33″ S, 52°40′45″ W, 810 m altitude), during the 2022/23 growing season. The regional climate is classified as Tropical Savanna (Aw) according to Köppen and Geiger. The soil at the site is characterized as Dystrophic Red Latosol (clay texture), with the following properties in the 0–0.20 m layer: pH (H2O) = 6.2; exchangeable Al (cmolc dm−3) = 0.0; Ca + Mg (cmolc dm−3) = 4.31; P (mg dm−3) = 41.3; K (cmolc dm−3) = 0.2; organic matter (g dm−3) = 19.74; base saturation (V%) = 45; aluminum saturation (m%) = 0.0; sum of bases (cmolc dm−3) = 2.3; cation exchange capacity (CEC, cmolc dm−3) = 5.1.

In this study, 32 soybean genotypes were evaluated. The seeds were sown in October 2022 and arranged in a randomized block design with three replicates. Each plot consisted of four rows, each one meter in length, with a row spacing of 0.45 m and a planting density of 15 seeds per meter.

Prior to sowing, the soil was conventionally prepared using plowing and leveling. Soybean seeds were treated with a fungicide (pyraclostrobin + thiophanate-methyl) and an insecticide (fipronil), applied at a rate of 200 mL of product per 100 kg of seed. Additionally, seeds were inoculated with Bradyrhizobium in the planting furrow to promote biological nitrogen fixation, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. During crop development, standard management practices—including fungicide, insecticide, and herbicide applications—were carried out as needed.

2.2. Spectral Analysis

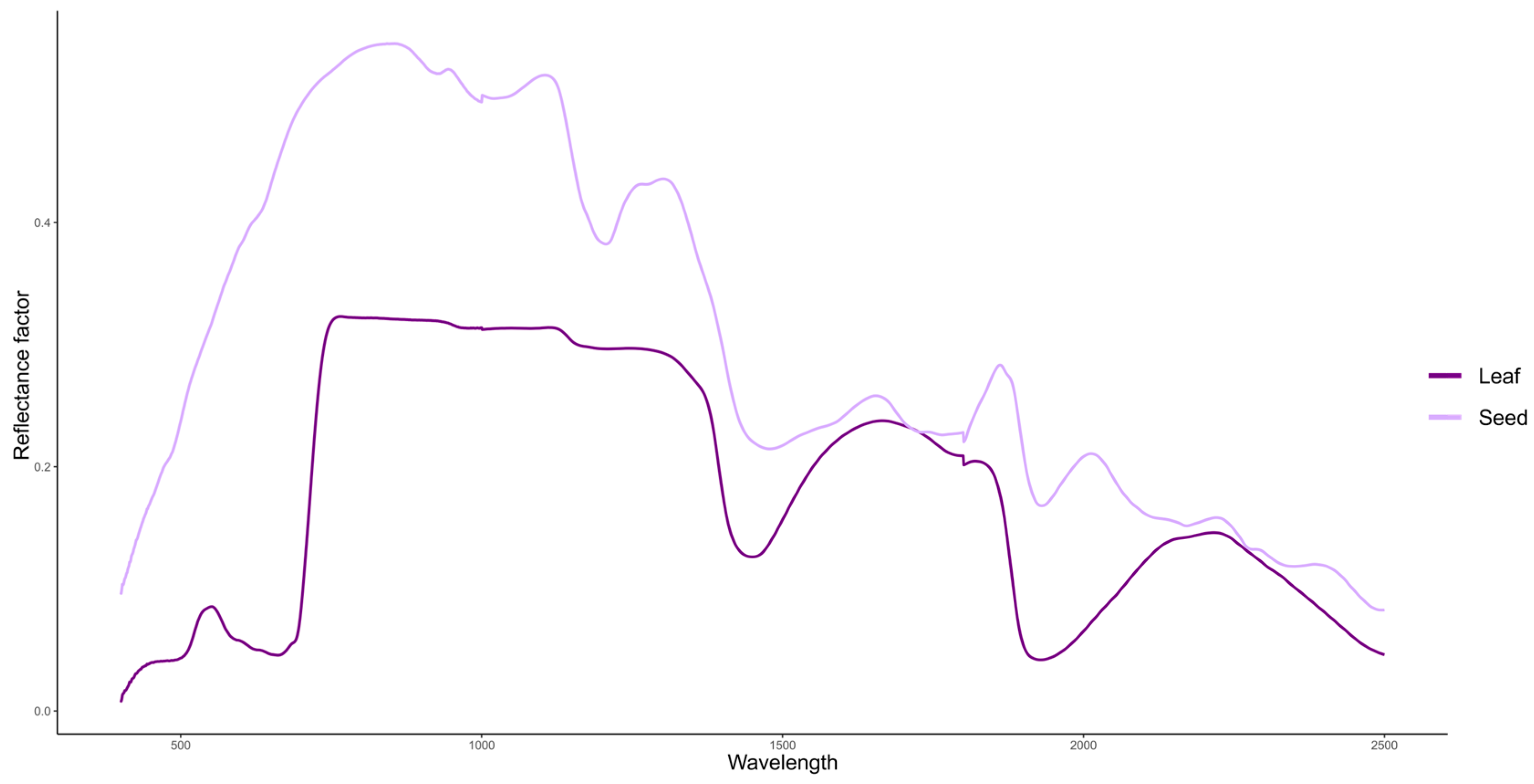

Spectral readings were taken from three leaf samples per plot, collected 60 days after emergence (DAE) and transported to the laboratory. After harvest, seeds were also brought to the laboratory and placed in Petri dishes for spectral measurements. Both leaf and seed evaluations were performed in triplicate within each plot, totaling 288 readings (32 genotypes, 3 replicates, 3 readings). The third fully developed trefoil was collected, placed in plastic bags, and promptly transported to the laboratory. Both leaf and seed analyses were performed using a FIELDSPEC 4 JR. spectroradiometer (Analytical Spectral Devices, Boulder, CO, USA), which measures reflectance across the 350 to 2500 nm range. The average spectral curve of the leaves and seeds is illustrated in

Figure 1. The ASD Plant Probe accessory was used for leaf measurements, as it is specifically designed for spectral assessment of solid materials. Calibration was performed using a white reference panel made of barium sulfate, which reflects 100% of incident light. The instrument was recalibrated after completing the readings for each block, totaling four calibrations.

The sensor remained connected to a computer throughout the measurements, with data acquisition managed by the proprietary RS3 software (version 6.4). After collecting the readings, the spectral files were imported into the ViewSpectroPro software (version 6.4), which comes with the equipment and allows for organizing and exporting the acquired spectra, as well as performing format conversions and basic data adjustments. In this study, the software was used specifically to export the spectra in .txt format, enabling their subsequent statistical analysis and processing in machine learning models.

2.3. Physiological Seed Variables

At genotype maturity, seeds were harvested from the four outer rows of each plot for subsequent seed quality analyses. Seed samples from each test plot were placed in Petri dishes to collect spectral data, and these same seeds were used to perform the physiological tests. The seeds from each experimental plot were initially placed in Petri dishes for spectral data acquisition. Then, the same seeds, already arranged in the dishes, were directly used to conduct the physiological tests, ensuring that the germination assessment was associated with exactly the same individuals analyzed spectrally.

Initially, the oven-drying method was employed to determine seed moisture content. Two subsamples of approximately 4.0 g each were taken from each genotype and placed in a forced-air oven at 105 ± 3 °C for 24 h [

16]. Results were recorded as a percentage on a wet basis. To standardize seed moisture at 12–13%, 40 mL of distilled water was added to Gerbox polystyrene boxes containing a grid to prevent direct contact between the seeds and water. The boxes were held in a germinator at 25 °C for 24 h. This conditioning ensured uniform germination probability among seeds.

The germination test (GERM) was conducted using four subsamples of 50 seeds per genotype, distributed on germitest paper previously moistened with water at 2.5 times the paper’s weight, and then incubated in a B.O.D. chamber (Eletro lab, model EL202/4G, Eletrolab Industry and Trade of Laboratory Equipment Ltda, Sao Paulo, Brazil) at 25 °C [

16]. Germination was assessed on the eighth day, and results were expressed as the percentage of normal seedlings. The first germination count (FGC) was performed concurrently, with normal seedlings counted on the fifth day and results were also expressed as a percentage.

For the electrical conductivity test (EC), 25 seeds were weighed on an analytical balance (0.0001 g precision) and soaked in plastic cups containing 75 mL of distilled water. The cups were kept in a germinator at 25 °C for 24 h [

17]. Conductivity readings were taken using a DIGMED DM-31 conductivity meter, with results expressed in µS cm

−1 g

−1 of seeds.

The tetrazolium test was performed on four subsamples of 25 seeds each, which were first pre-soaked on germitest paper moistened with water at 2.5 times the paper’s weight and kept in a germinator at 25 °C for 16 h. After pre-soaking, seeds were immersed in a 0.075% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride and incubated in the dark at 35 °C for four hours in a B.O.D. chamber. Following staining, seeds were individually evaluated and classified as vigorous (VIG-TZ) or viable (VIAB), according to the methodology described by [

4].

2.4. Machine Learning Analysis

After collecting the spectral and physiological data from the seeds, all results were compiled and subjected to statistical analysis. Machine learning (ML) analyses were performed using two different input configurations: (i) leaf spectral variables and (ii) seed spectral variables. The target variables predicted (outputs) included GERM, EC, FGC, VIG-TZ, and VIAB. Model predictions were evaluated using stratified 10-fold cross-validation with ten repetitions, totaling 100 runs for each algorithm. All model parameters were set to the default values in Weka version 3.8.5. In WEKA, this process occurs as follows: The data is automatically divided into 10 subsets (folds), as mentioned in the methodology of the work. In each round, one subset is used as a test set, while the others are used to train the model. This process is repeated 10 times, so that each subset is used once as a test. Due to the quality of the sensor used, high precision and stability in measurements, providing consistent spectral data with low correction needs due to the low amount of noise, we opted for an approach that could be easily reproduced by other researchers without the need for additional pre-processing routines, which often require specific methodological decisions and can introduce variability between studies. The data were used directly in raw form for model evaluation, which was performed by cross-validation in WEKA, ensuring the reliability of the analysis even without pre-processing.

The machine learning models applied for prediction included multilayer perceptron artificial neural networks (MP) [

18]; REPTree decision trees [

19]; M5P decision trees [

20]; random forest [

21]; support vector machines [

22] and ZeroR, which serves as the default baseline predictor in Weka.

ANNs are models inspired by the functioning of the human brain, formed by layers of connected “neurons” that learn complex patterns from data by adjusting the weights of their connections. The REPTree decision tree creates a tree-like structure that divides data into branches using simple attribute-based rules. The REPTree uses pruning and sampling to reduce overfitting and improve generalization. The M5P decision tree is similar to the REPTree, but it combines the tree structure with regression models on the branches. A random forest is an ensemble of several randomly generated decision trees. Each tree returns a result, and the average or majority of responses defines the final prediction, increasing accuracy and robustness. Support Vector Machine (SVM) searches for a line or surface that best separates data into classes or predicts values, maximizing the margin between groups. It is effective even with small data and high dimensionality. ZeroR: A reference model that makes simple predictions based on the average (for continuous values) or the most frequent class (for classification). It serves to compare the performance of other models.

Model performance was assessed using the correlation coefficient (r), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine the significance of the effects of input type, ML model, and their interaction. When significant effects were detected, boxplots of r, MAE, and RMSE means were generated and grouped at a 5% probability level using the Scott-Knott test [

23]. All boxplots and mean groupings were produced with the ExpDes.pt (version 1.2.2) and ggplot2 (version 3.4.2) packages in R (version 4.2.3).

3. Results

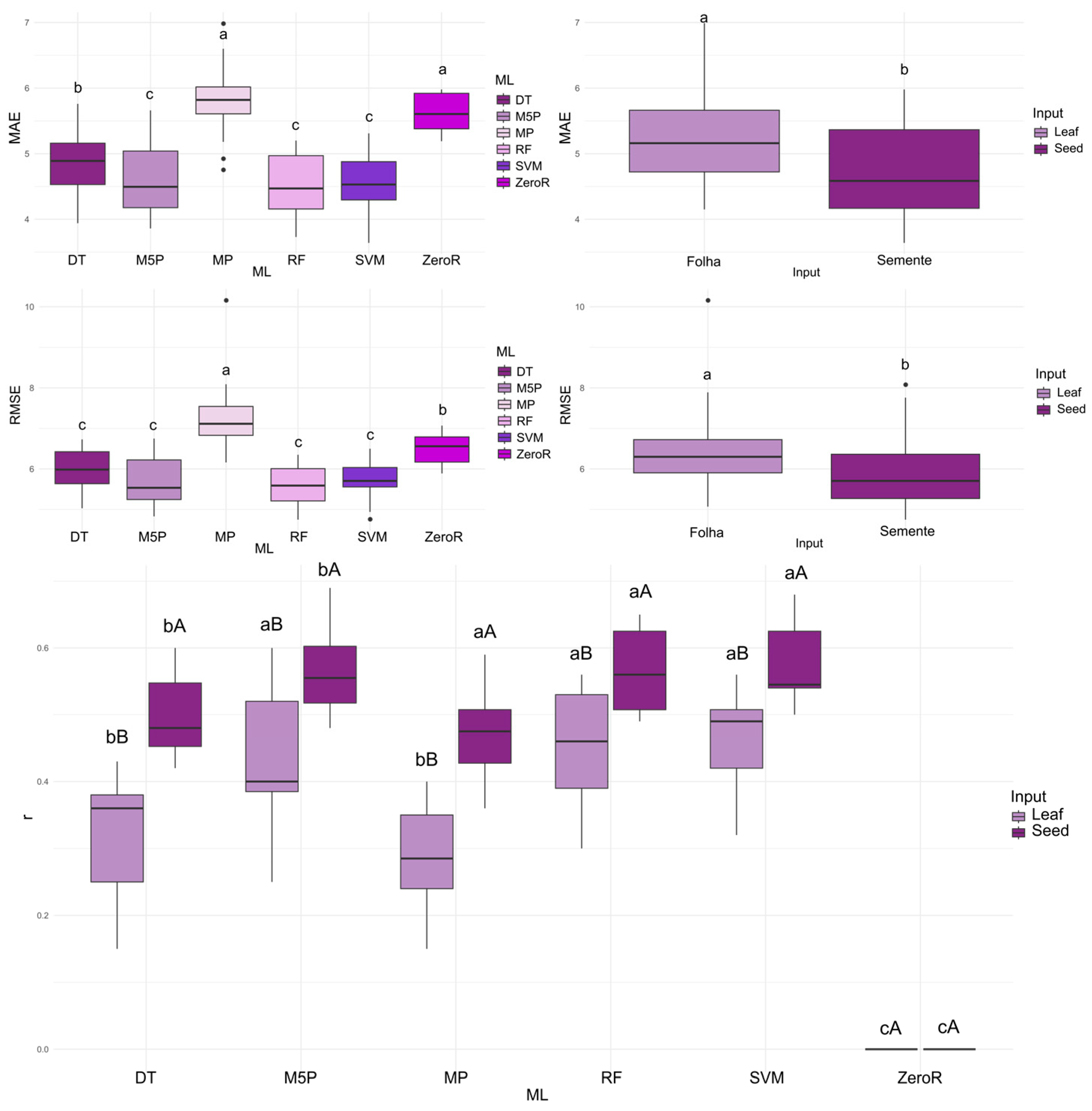

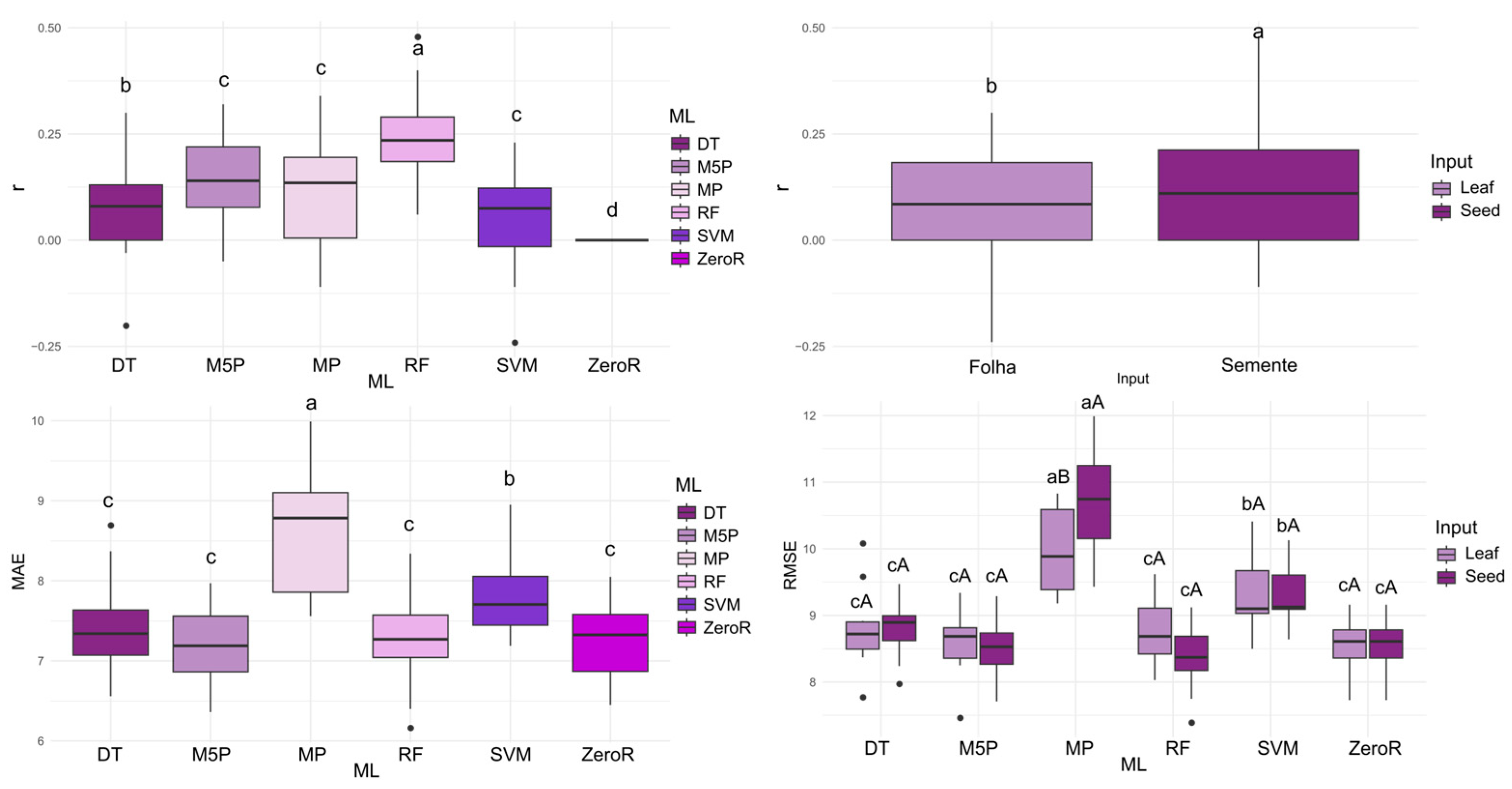

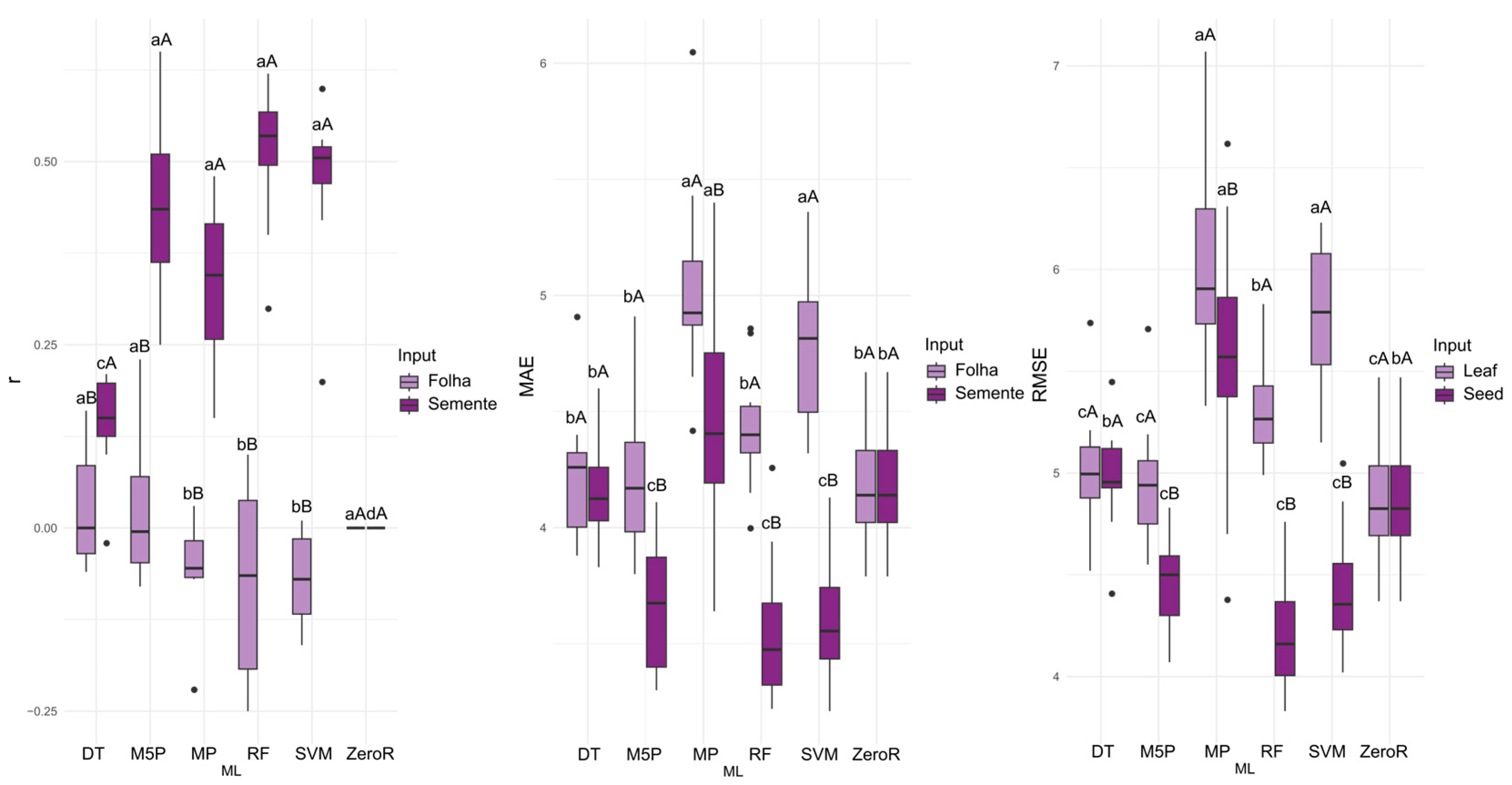

When using leaf spectral data as input, the highest mean correlation coefficients (r) were observed with the M5P (0.426), RF (0.453), and SVM (0.462) algorithms. For the prediction of GERM, the strongest correlations between predicted and observed values were achieved by M5P, RF, and SVM, with mean r values ranging from 0.565 to 0.575 when seed spectral data were used as input. Overall, the seed input consistently resulted in higher predictive accuracy across all algorithms (

Figure 2).

Regarding MAE, the algorithms that achieved the best performance were M5P, RF, and SVM, with the lowest errors observed when seed reflectance was used as input. For RMSE, the algorithms with the lowest errors were DT, M5P, RF, and SVM, again with seed reflectance providing the most accurate results for this metric.

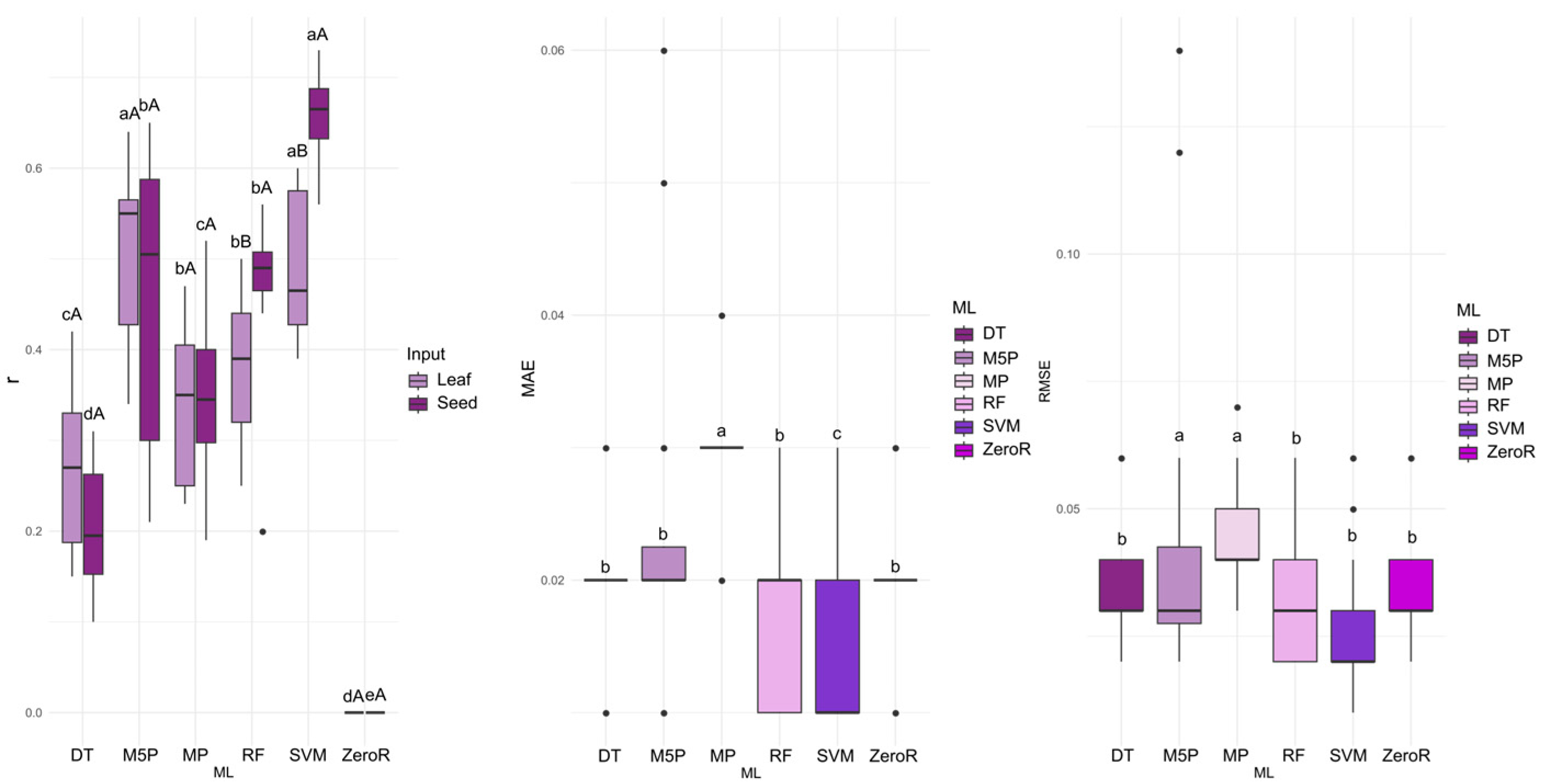

For the prediction of electrical conductivity (EC), the M5P algorithm achieved the highest accuracy (mean r = 0.506), closely followed by SVM (r = 0.492) when leaf data were used as input. When seed data served as input, SVM yielded the highest mean correlation (r = 0.658). For the MP, RF, SVM, and ZeroR algorithms, seed reflectance consistently resulted in superior performance (

Figure 3). SVM also produced the lowest MAE (0.0145) and RMSE (0.0255) values, making it the most accurate algorithm for EC prediction.

For the prediction of first germination count (FGC), the M5P algorithm yielded the highest accuracy with a mean correlation coefficient of 0.720 when leaf spectral data were used as input. When seed spectral data served as input, the best results were achieved by the M5P, random forest (RF), and support vector machine (SVM) algorithms, with mean correlation coefficients ranging from approximately 0.735 to 0.777. Overall, seed spectral data consistently produced the most accurate predictions across all tested algorithms (

Figure 4).

For leaf spectral input, the M5P algorithm yielded the lowest MAE values. When seed spectral data were used as input, the lowest MAE values were achieved by the M5P, DT, RF, and SVM algorithms. For the ZeroR algorithm, the mean errors across input types were statistically similar, unlike other tested algorithms where seed input resulted in the lowest error. Using leaf reflectance as input, M5P produced the lowest RMSE values. When seed reflectance was used as input, the DT, M5P, RF, and SVM algorithms achieved the lowest RMSE values.

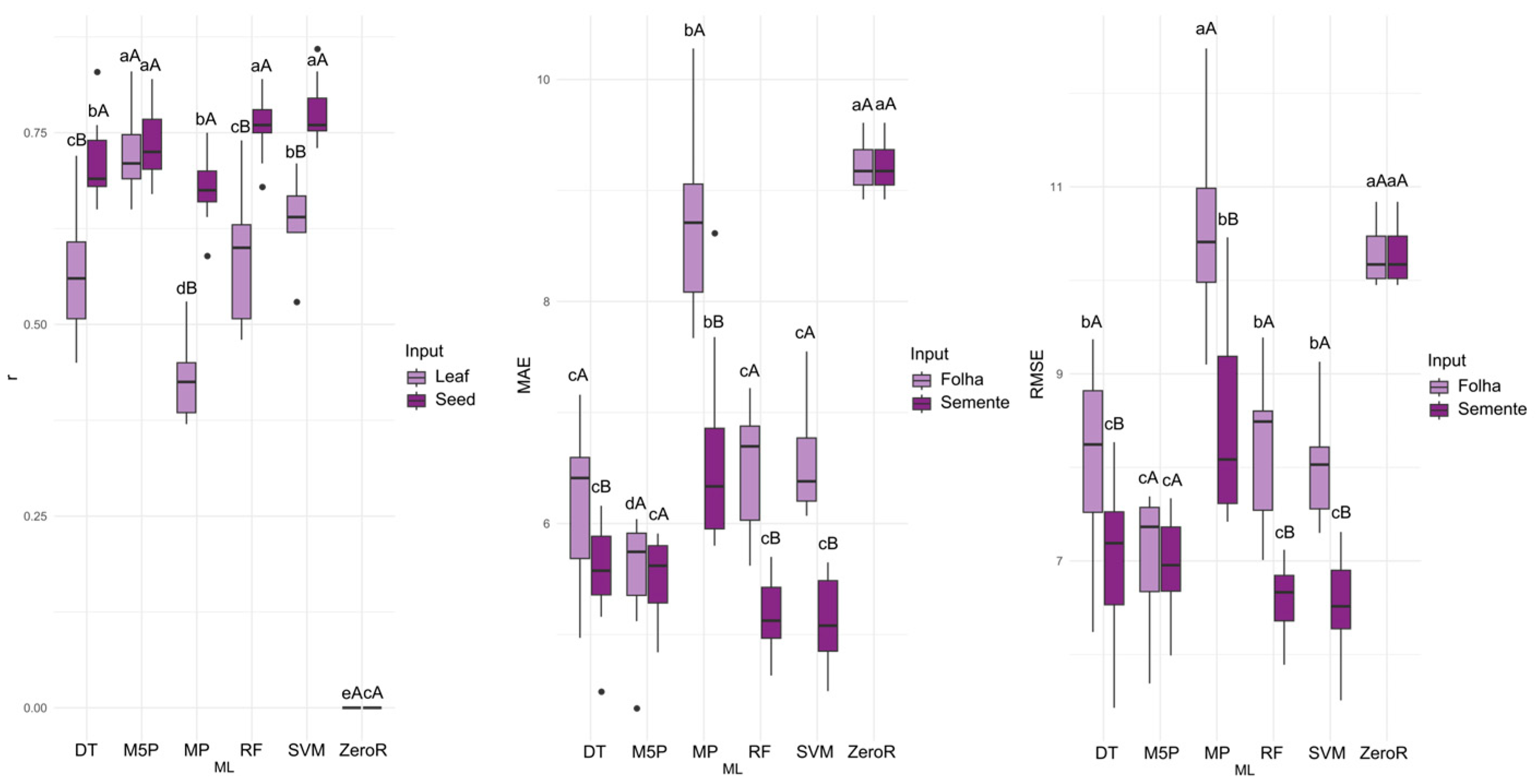

In predicting tetrazolium vigor (TZVG), the random forest (RF) algorithm performed best, with an approximate MAE of 0.25. Among the variables, seed reflectance provided the highest accuracy (

Figure 5). The M5P algorithm showed the lowest MAE values. For leaf reflectance input, the ZeroR algorithm yielded the lowest RMSE values. When seed reflectance was used as input, the RF algorithm achieved the lowest RMSE (8.355). For the ZeroR, RF, and SVM algorithms, seed input resulted in lower errors, whereas for the MP algorithm, leaf input produced lower errors.

The highest correlations between predicted and observed values (r) for viability (VIAB) were achieved by the SVM, MP, RF, and M5P algorithms. Considering seed spectral input, the best performances were obtained by the M5P, RF, and SVM algorithms, with mean r values exceeding 0.5. Seed input yielded the highest accuracy across all algorithms analyzed, except for ZeroR, which showed statistically similar performance for both input types (

Figure 6).

Considering MAE, the algorithms with the best performance were M5P, RF, and SVM, with seed reflectance input yielding the lowest error. For the RMSE accuracy metric, when using leaf reflectance as input, the DT, M5P, and ZeroR algorithms exhibited the lowest values. When seed reflectance was used as input, M5P, RF, and SVM achieved the lowest RMSE values. Consistent with other metrics, the lowest average errors were observed when using seed input.

Among the algorithms analyzed, the M5P decision tree demonstrated the highest accuracy, also standing out by presenting the lowest values in the MAE and RMSE accuracy metrics. The input that resulted in the lowest errors and consequently the highest accuracy was seed reflectance.

4. Discussion

The primary goal of seed production is to establish fields with an optimal plant population, ensuring that individuals possess the genetic, physiological (such as germination) and sanitary qualities necessary to maximize yield and prevent the spread of pests, pathogens, and weeds. The ability to predict germination is critical for supporting sustainable agricultural practices [

24]. Accurate germination forecasts enable growers to better plan sowing, optimize resource use (such as water and nutrients), minimize the need for replanting, and reduce seed deterioration, thereby ensuring a healthy and resilient crop stand. Large-scale germination experiments are often labor-intensive and prone to human error, highlighting the importance of automated approaches such as machine learning [

25].

Remote sensing technologies, particularly hyperspectral sensors, allow for the acquisition of hundreds of spectral bands, capturing reflectance profiles that facilitate the identification of biological materials [

26]. Each plant organ exhibits a unique spectral signature, as chlorophyll content and other organic compounds may vary across different tissues [

27]. This technology has proven to be a non-destructive and efficient method for germination testing, reducing the risk of human error.

The use of hyperspectral spectroscopy in seeds emerges as a promising alternative to conventional evaluation methods, as it enables rapid, non-destructive, and highly reproducible analyses. By eliminating the need for destructive or time-consuming tests, such as traditional germination, this technology reduces the time to obtain results and minimizes the influence of human error associated with visual manipulation and interpretation. Furthermore, the combination of spectral data with machine learning algorithms has significantly expanded the ability to identify subtle patterns related to physiological quality, enabling the prediction of variables such as germination, vigor, and viability with a high degree of accuracy. Thus, the integration of hyperspectral remote sensing and computational modeling represents an important advance in the field of seed physiology, offering a robust and sustainable tool for monitoring the quality of seed lots in breeding, certification, and agricultural production programs.

The M5P algorithm combines the structure of a traditional decision tree with the ability to perform linear regression at its terminal nodes, thus estimating the target variable for each instance reaching a leaf node [

28]. Ref. [

29] demonstrated the effectiveness of M5P for modeling reference evapotranspiration, while [

30] recognized its robustness for time series analysis, enabling predictions such as increased inter-row erosion in disturbed pastures based on soil data. A [

31] reported that M5P delivered higher accuracy, faster computation, and lower costs compared to regression models for predicting the dry stigma and saffron flower weights for commercial purposes.

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning method that increases the robustness and accuracy of predictions by constructing a multitude of decision trees, each trained on bootstrap samples from the training dataset [

28]. Its effectiveness in the agricultural sector is remarkable; for example, in a study on soil fertility prediction, RF demonstrated great potential, achieving training and testing accuracies of 93% and 83%, respectively [

32]. Ref. [

33] This result highlights the reliability of RF as a tool for optimizing soil management and, consequently, increasing crop productivity. The same algorithm also proved effective in predicting corn yield using multispectral data [

34]. Thus, the algorithm has established itself in the agricultural field in various contexts with distinct and variable tasks, demonstrating in our work its potential for predicting seed-related attributes.

Seed reflectance analysis consistently proved to be the most effective parameter among the tested configurations, presenting the highest accuracy and the lowest Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values for all prediction algorithms. This high performance is justified by the strong correlation between the seed’s spectral properties and its intrinsic genetic, physical, physiological, and health attributes, which are the cornerstones of ensuring high agronomic performance. Physiological potential is assessed through viability and vigor, which reflect a seed’s ability to germinate rapidly and uniformly [

35]. Germination is evaluated by observing radicle emergence and the development of a healthy seedling with well-formed roots and shoots [

36].

While traditional germination assessment requires time-consuming observation of radicle emergence and the development of a healthy seedling with well-formed roots and shoots, the reflectance technique allows for a non-invasive, real-time assessment of internal biochemical and structural characteristics. This enables the rapid identification and disposal of immature, damaged, or low-vigor seeds, optimizing batch quality control before sowing and ensuring planting uniformity, a crucial factor for final crop productivity. The success of spectral reflectance, especially when combined with machine learning algorithms, solidifies its potential as a high-throughput screening method for seed vigor, overcoming the time and subjectivity limitations of conventional testing.

The superior accuracy observed with seed reflectance can be attributed to the close relationship between seed reserves and germination capacity [

37]. Carotenoids and chlorophylls are strongly linked to seed quality, even when influenced by genetic factors [

38]. Under stress, seeds tend to accumulate carotenoids and chlorophylls as a defense response [

39]. Consequently, seeds exhibiting higher reflectance typically indicate greater stress and lower physiological quality, which correlates with reduced germination. Conversely, seeds with lower reflectance are generally of higher physiological quality, as they contain lower levels of chlorophyll and carotenoids, supporting greater viability and vigor and thus higher germination rates.

Seed viability is defined by the ability to germinate under optimal moisture and temperature conditions, while vigor reflects the capacity to germinate and produce healthy seedlings even under suboptimal environments [

40]. Thus, the predictive superiority observed when using seed spectral data can be explained by the fact that the physiological attributes determining germination, such as tissue integrity, energy reserves, and metabolic activity, are inherent to the seed itself. These factors directly influence its spectral signature, making it more representative of the actual physiological state and, consequently, more effective for machine learning-based prediction models.

Ref. [

41] successfully classified soybean agronomic traits using leaf reflectance at different developmental stages, and [

42] assessed seed physiological quality based on leaf spectral data, reinforcing the use of technologies for soybean seeds. This study presents a significant innovation for seed producers by demonstrating that leaf reflectance can also produce accurate predictions for most physiological variables when using the M5P algorithm, helping seed producers and researchers gain early insights into the quality of their production.

Predicting seed quality through leaf reflectance is particularly valuable, as it enables the assessment of germination and vigor prior to harvest. Future research could leverage hyperspectral sensors mounted on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to collect leaf data before crop maturity. Leaf reflectance proved especially effective with the M5P algorithm, which achieved the highest correlation coefficients and the lowest MAE and RMSE values for the prediction of both germination test and first germination count. Leaves play a crucial role in the synthesis and transport of photoassimilates to developing seeds [

43]. As seeds reach physiological maturity and embryogenesis is complete, the maternal plant ceases the transfer of photoassimilates, and seed viability and vigor peak [

44]. Thus, healthy leaves contribute to the development of high-quality seeds, ensuring successful propagation.

This work demonstrates that reflectance, both from leaves and seeds, can be efficiently used in machine learning models to estimate physiological seed attributes, reducing the time and cost of conventional laboratory analyses. One of the distinguishing features of this research is the use of leaf reflectance as an early indicator, allowing the prediction of physiological performance even before harvest, a characteristic little explored in the literature and which represents an innovative contribution to methods of early seed quality assessment. We recognize, however, that some limitations remain. The dataset is still limited in size and scope, which may restrict the generalization of the models. In this sense, future studies involve multiple crop seasons, expand the database with different genotypes, environmental conditions, and phenological designs, as well as compare traditional approaches with more advanced methods, such as deep learning and automatic selection of spectral variations. Furthermore, the integration of spectral data with other sources of information, such as morphological characteristics or chemical composition, emerges as a promising opportunity to increase the robustness and accuracy of predictive models, deepening the contribution of this field of research.