Abstract

Natural fibers are increasingly used as sustainable, lightweight, and low-cost alternatives to glass fibers in polymer composites. However, their inherent hydrophilicity and surface polarity limit compatibility with non-polar polymer matrices. Both gas/solid and plasma fluorination modify only the surface of lignocellulosic materials. Mild conditions are mild, with reactivity governed by fluorine concentration, temperature, and material composition. Surface energy is typically assessed through contact-angle measurements and surface analytical techniques that quantify changes in hydrophobicity and chemical functionalities. In wood, fluorination proceeds preferentially in lignin-rich regions, making lignin a key component controlling reactivity and the spatial distribution of fluorinated groups. Natural fibers follow the same logic as for flax, which is a representative example of lignin content. Applications of fluorinated bio-based materials include improved moisture resistance, enhanced compatibility in composites, and functional surfaces with tailored wetting properties. Scalability depends on safety, cost, and process control, especially for direct fluorination. Durability of the treatment varies with depth of modification, and environmental considerations include the potential release of fluorinated species during use or disposal.

1. Introduction

Natural fibers are increasingly replacing glass fibers as polymer reinforcements in eco-composites due to their comparable specific properties and added benefits such as being bio-based, locally available, lightweight, and cost-effective [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. These advantages are driving their adoption in sectors like transportation (aerospace, automotive), but not exclusively, and their use is expected to grow with rising environmental concerns and the development of a bioeconomy focused on sustainable growth [3,4,5,9]. However, the mechanical performance of composites depends heavily on the fiber/matrix interface. Flax fibers, considered among the best natural reinforcements [10] due to their excellent intrinsic mechanical properties [11,12,13], present challenges due to their high polarity and hydrophilicity. Lignocellulosic components (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) contain many hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, leading to strong surface polarity, with typical surface tension components of γsp = 26.0 mN/m and γsd = 34.0 mN/m [14]. This results in moisture sensitivity, causing dimensional changes that can lead to cracking [15], and poor compatibility with common hydrophobic resins, producing interfacial voids that weaken mechanical properties [2,15,16,17,18,19,20].

To improve fiber/matrix adhesion, several physical and chemical surface modification methods have been explored, including thermal treatments [21], electrical discharges [22] or chemical treatments such as acetylation, maleic anhydride grafting, and mercerization [23,24]. While these treatments reduce polarity and improve compatibility, they often rely on solvents or high energy input, which increases the carbon footprint, an issue that contradicts the eco-friendly aims of such composites. Reducing the hydrophilicity of lignocellulosic materials has long been a major challenge for researchers and textile professionals. Over the years, various treatments have been developed. One of the most notable is acetylation, first applied in 1928 for wood modification [25]. It involves esterification between hydroxyl –OH groups and acetic anhydride, replacing hydroxyl groups with acetyl groups, which reduces water absorption and enhances compatibility with hydrophobic polymer matrices [26,27,28]. Acetylation also improves UV resistance and dielectric properties. However, due to the cost and toxicity of acetic anhydride, its industrial use remains limited [26,29]. Alkaline treatment, or mercerization, introduced by J. Mercer in 1844, remains widely used for reinforcing thermoplastic and thermoset matrices [27,30,31]. Sodium hydroxide ionizes –OH groups, forming ionic bonds and increasing mechanical strength by altering fiber microstructure and enhancing surface roughness for better adhesion. Plasma treatments, utilizing ionized gases, modify only the fiber surface without affecting bulk properties [32]. Since the 1960s, they have been used to improve fiber/matrix interfacial bonding in eco-composites [33,34,35,36,37]. Depending on the plasma type and parameters, plasma can either increase hydrophilicity by grafting oxygen-containing groups [38] or increase hydrophobicity by reducing polar surface groups [39]. Plasma also affects surface roughness, which plays a key role in mechanical interlocking [34,36,38,39,40]. Torrefaction, a mild pyrolysis process conducted at 200–300 °C in an inert atmosphere, significantly reduces fiber hydrophilicity by degrading hemicellulose [41,42,43,44]. However, it compromises fiber strength, particularly tensile strength. Despite this, torrefaction is still considered among the most eco-friendly methods currently available. Maleic anhydride grafting (MAPP) was developed to improve adhesion between fibers and polypropylene by forming covalent bonds at the fiber–matrix interface [45,46,47,48,49]. Despite its effectiveness, maleic anhydride is hazardous to health, particularly the respiratory system, limiting its use. Many other surface modification methods exist—silane coupling, benzoylation, peroxide, ozone, isocyanate treatments, etc. [30,33,50]—but most rely on toxic chemicals or energy-intensive processes, contradicting the eco-composite ethos. Emerging green approaches, such as copper film deposition [51] or enzymatic bio-grafting using ferulic acid [52], show promise at lab scale [53,54,55,56,57,58,59], though scaling them up remains complex and costly. Among current options, torrefaction stands out as a sustainable yet imperfect solution, given its energy demand and fiber degradation (up to 60% strength loss). To address these limitations, this paper reviews an original alternative: heterogeneous gas/plasma–solid fluorination, aiming to reduce fiber polarity without compromising mechanical performance or environmental safety.

In this review, we explore the evolving landscape of fluorination processes, focusing on both gas/solid and plasma techniques. We then examine the various methods used to investigate surface energy changes resulting from fluorination. Particular attention is given to the fluorination of wood, where lignin plays a central reactive role, followed by a case study on natural fibers with flax as a representative example. The review also highlights current and potential applications of fluorinated bio-based materials. Finally, we discuss future directions, identifying the most promising materials and the most suitable processes for treating long natural fibers.

2. General Trends for Gas/Solid and Plasma Fluorination

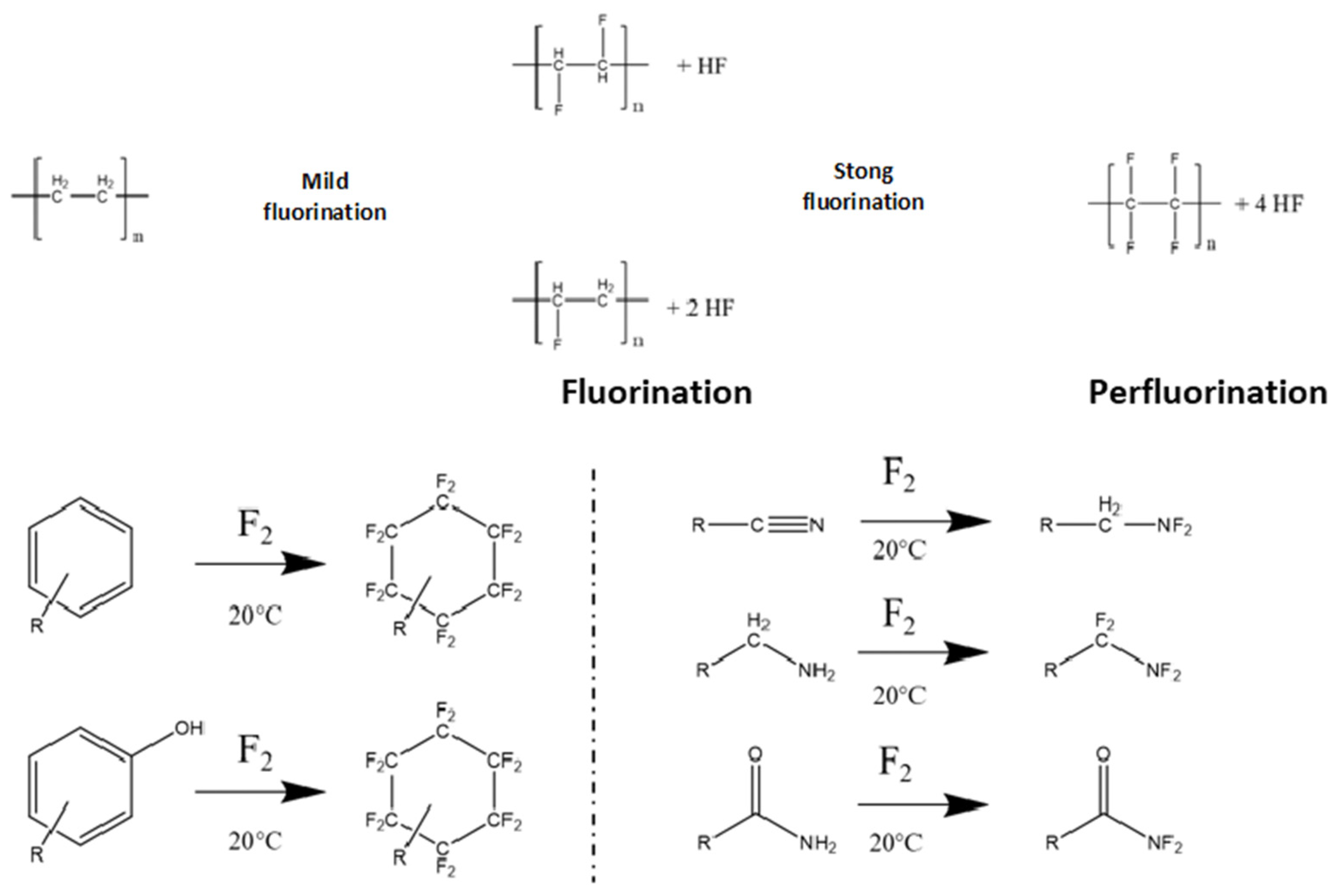

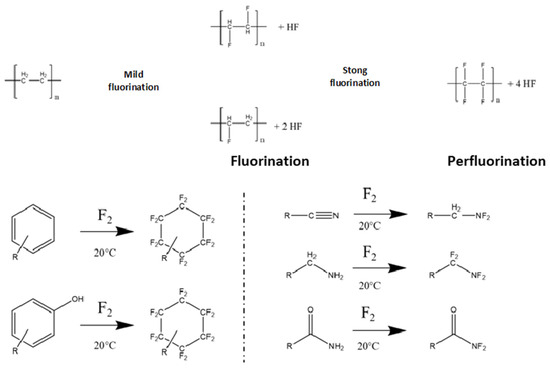

Fluorination is a chemical process that covalently grafts one or more fluorine atoms onto various substrates (e.g., materials, molecules). Fluorine exists under ambient conditions as a diatomic gas (F2), extremely reactive due to its low dissociation energy (155 kJ/mol) [60]. Its high electronegativity of the element (3.98, the highest on Pauling’s scale) [61], small size, and stability allow it to form strong C–F bonds (ΔH = 490 kJ/mol) superior to that of C–C bonds (ΔH = 348 kJ/mol), allowing for the treatment to be stable over time. Nevertheless, if these properties are advantageous for surface modification they also make fluorine highly corrosive and toxic, requiring strict handling precautions. The first reported fluorination of a lignocellulosic material was by Polčín in 1955 [62], using chlorinated lignin (18–20% chlorine content) in ethanol, toluene, and xylene with various fluorides (NaF, KF, AgF, SbF3) at 80–150 °C. However, only 2% fluorine incorporation was achieved. This marked the beginning of fundamental research on fluorination of lignocellulosic substrates. Significant progress came in 1990, when Saphieha et al. [63] treated kraft paper using CF4/O2 plasma, dramatically increasing its hydrophobicity. The paper no longer absorbed water droplets when the CF4 ratio exceeded 50%, due to covalent fluorine grafting. A similar study [64] used radiofrequency CF4 plasma to fluorinate paper, resulting in higher water contact angles, confirming reduced wettability. For years, lignocellulosic fluorination was mainly performed in liquid phase using fluorinated chemicals in organic solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, DMF, DMSO, glymes) with catalysts like KF, NaF, CsF [65]. Although still used today, such methods are environmentally unfriendly and inconsistent with the “eco-composite” concept. Moreover, the use of liquids can damage lignocellulosic materials due to their hygroscopic nature. As a result, dry fluorination methods, such as plasma or direct F2 gas treatment, are more suitable for lignocellulosic surface modification. The “La-Mar direct fluorination process” (1974) [66,67,68], enabled control of this gas–solid reaction, where F2 (often diluted with inert gases like N2 or Ar) reacts with material surfaces. The process is exothermic and can occur at room temperature (or even at liquid nitrogen temperatures), with reactions localized to the surface due to the self-limiting growth of a fluorinated layer. Though highly effective, direct fluorination of (bio)polymers generates byproducts such as HF, CF4, and C2F6. HF forms through the conversion of C–H and C–OH groups to C–F, while CF4 and C2F6 arise from decomposition under F2. Thus, handling and neutralization systems are essential to eliminate these hazardous gases due to HF’s high toxicity [69,70]. Surface fluorination modifies only the outermost material layers, adjusting properties like surface energy or gas barrier behavior. It is commonly used in the automotive and packaging industries. A key example is the fluorination of high-density polyethylene (PE-HD) fuel tanks, reducing fuel permeation by a factor of 80 [69]. While fluoropolymers such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE Teflon®) offer excellent performance, they are expensive and difficult to synthesize. Surface fluorination offers a cost-effective alternative when only the surface requires such properties. Layer thickness depends on the application: nanometers for low surface energy, microns for barrier or tribological applications. Using F2/O2 mixture leads to oxyfluorination, introducing groups like C=O, –COF, or –COOH [71]. Although this approach remained largely theoretical for years, better control emerged through the La Mar process, leading to mechanistic studies. Lagow and Margrave [67] proposed radical fluorination models in 1979 using CF4 and C2F4 as references. Fluorination begins with reactions on C–H, C–OH, and C=C groups, forming C–F, CF2, CF3, and under oxyfluorination conditions, C=O or COOH groups [71]. Extended treatment can lead to perfluoration, saturating carbon atoms with fluorine without structural damage. For example, polyethylene requires weeks of treatment to achieve a surface similar to (–CF2–CF2–)n [72], while other polymers like polystyrene perfluorate faster (Figure 1). Aromatic structures (phenols, amines, amides) in polymers also react with fluorine (Figure 1). Oxygen presence leads to unwanted –COF formation, which hydrolyzes to –COOH upon air exposure, affecting surface energy. This is why ensuring system tightness and gas purity is crucial. Despite precautions, radical formation during fluorination causes post-reactivity upon reactor opening.

Figure 1.

Fluorination mechanisms of polyethylene and different chemical groups present in polymers (according to [67]).

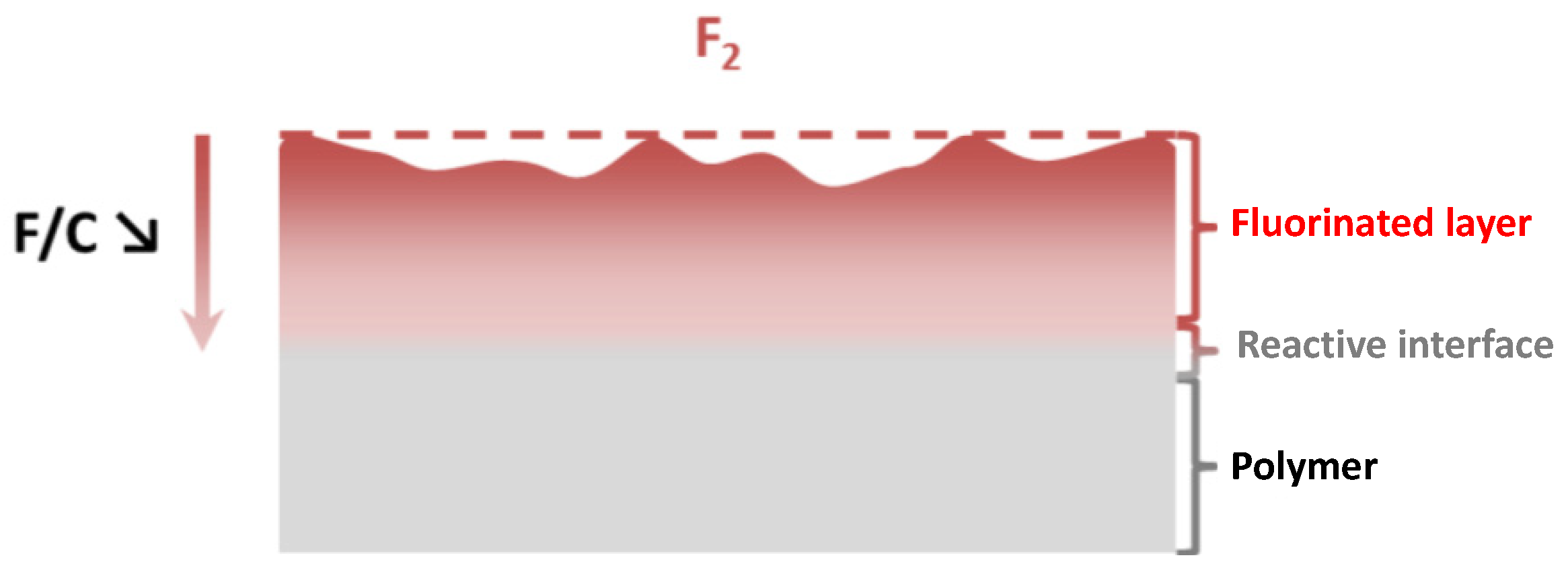

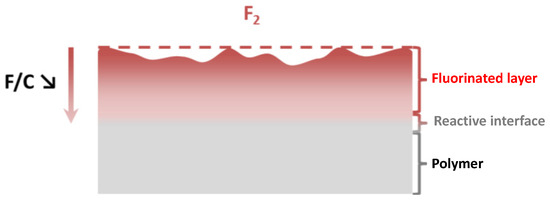

Diluting F2 with inert gases (N2, Ar, He) helps reduce polymer degradation and limits C–C bond cleavage, minimizing radical formation and surface damage. At the macroscopic level, fluorination of polymers and lignocellulosic materials starts at the surface and progresses inward. As diffusion slows the reaction, the surface layer receives the most fluorine exposure, resulting in hyperfluorination and increased surface roughness (Figure 2). Kharitonov et al. [72] showed that the rate of fluorination varies with substrate structure. For instance, backbone C–H bonds are hardest to fluorinate (e.g., PE). Side groups (–CH3, phenyl) enhance hydrogen substitution (e.g., PP, PS). Oxygen-containing groups or heteroatoms (like Cl) increase reactivity. These trends imply that biopolymers, rich in OH, phenyl, and C=O groups, are highly reactive toward fluorine and require careful control. In static fluorination (closed reactor, fixed F2 dose), the fluorinated layer thickness δF follows a square root law: δF = Atn + const. = B(pF)kt0.5 + const, where A depends on partial pressures of O2, F2, N2, and HF, and B and k vary by polymer [72].

Figure 2.

Fluorine concentration gradient during fluorination under F2 of a polymer.

To avoid over-fluorination of lignocellulosic materials, fluorine gas must be strongly diluted in an inert gas such as N2, He, or Ar. Typical operating temperatures are kept as low as possible, generally 20–50 °C to prevent thermal degradation. In dynamic mode, the F2 flow rate is usually limited in the range 6–60 mL/min, while the dilution gas is supplied at much higher flow (often 240–294 mL/min) to maintain a low fluorine relative content (2–20%Vol.). Continuous purge gas flows after treatment to help stabilize the material and remove residual fluorine. Reaction duration must also be restricted; depending on the material, a few minutes to tens of minutes are generally sufficient. These controlled parameters—i.e., low temperature, strong fluorine dilution, low F2 flow rate, high inert-gas flow, and short exposure time—are essential to achieve surface fluorination while preserving the structural integrity of lignocellulosic materials.

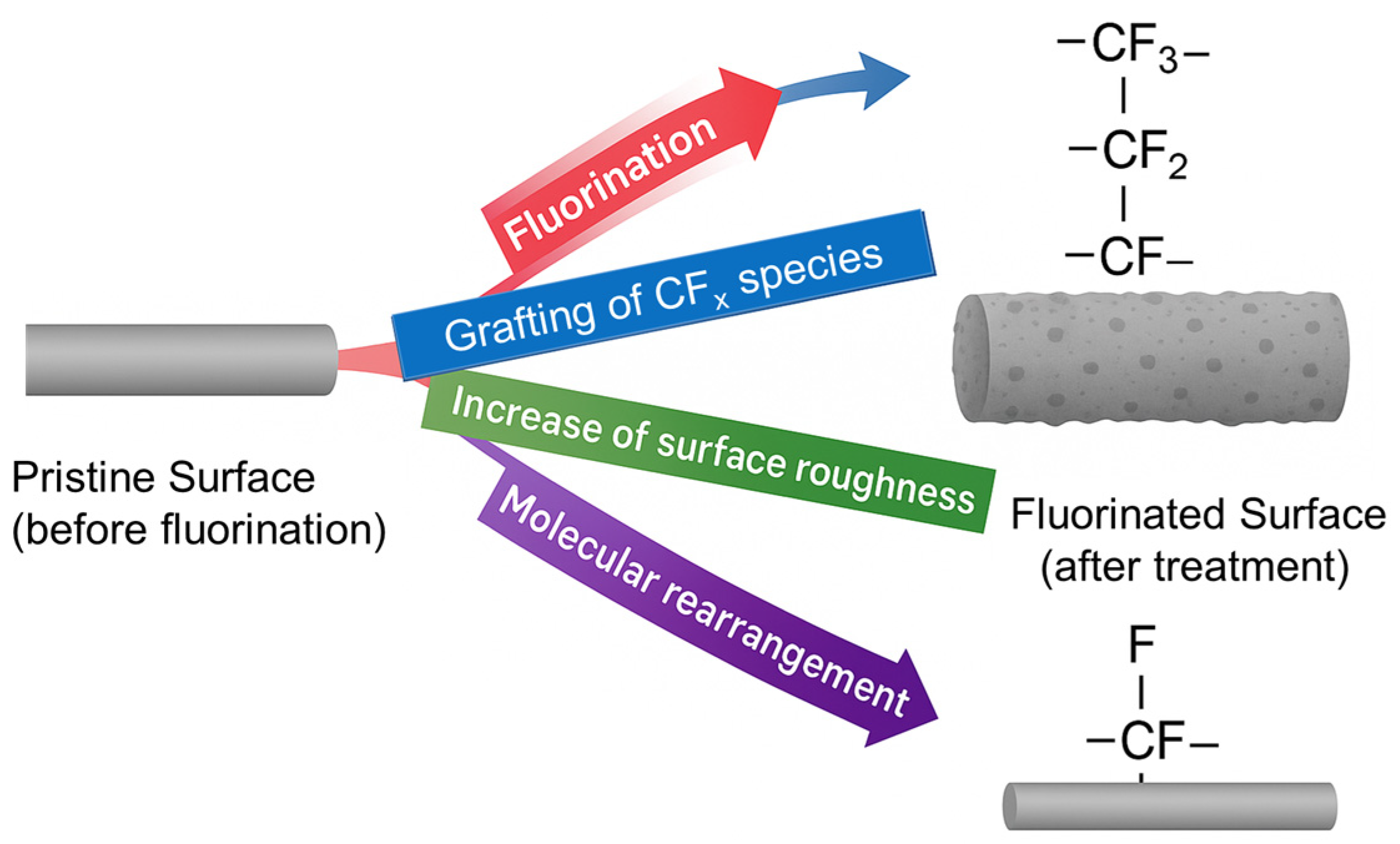

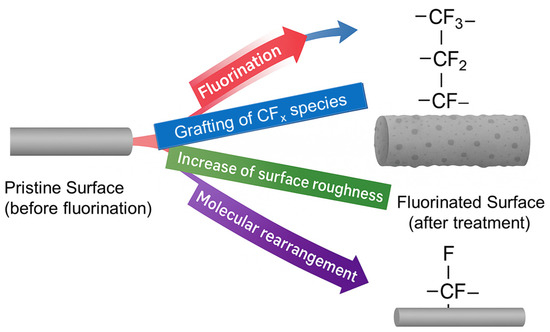

Plasma treatments represent highly effective techniques for modifying the surface properties of various materials, especially natural fibers. Among fluorinated plasmas, those generated from gases such as SF6, CF4, CHF3, C2F6, C3F6, and C4F8 are predominantly used. These plasmas were initially developed for etching processes in microelectronics but have since been applied for surface treatments aimed at altering the reflectance or wettability of different materials [73]. When applied to natural fibers, four main reaction mechanisms typically occur, with their relative importance depending on treatment parameters such as discharge type, reaction time, gas pressure, and applied power [74]. The reactions are schematized in Figure 3. First, there is the functionalization of the surface through the incorporation of fluorine atoms (fluorination), mainly via reactions with hydroxyl groups. Second, the deposition of fluorinated groups such as CFx, CHxFy, or SFx takes place on the material surface. Third, surface roughness is created or modified by controlled or incidental etching. Finally, the surface is stabilized through rearrangement reactions of excited molecules (AB + CD → AC + BD) [75], including those on the fiber surface.

Figure 3.

Reaction mechanisms involved in the use of fluorinated plasma on natural fibers.

For the modification of surface energy of lignocellulosic materials by plasma treatment, the goal is to simultaneously form a fluorocarbon layer on the outermost surface and increase the substrate roughness. These two modifications chemically and physically enhance the hydrophobicity of the samples [73,76,77]. For instance, treatments of cotton fabrics using CF4 or C3F6-based plasmas have achieved water contact angle changes from 30° to angles ranging from 90° to 150°, depending on the experimental conditions [78]. In the pursuit of producing hydrophobic lignocellulosic materials, some researchers have focused on combining oxygen plasma etching with CF4 plasma deposition. This combined treatment allowed Sapieha et al. [63] to obtain cellulose fibers that no longer absorb water droplets when the CF4:O2 ratio in the plasma exceeds 50% CF4. Using the same gas mixture, Xie et al. [79] demonstrated superhydrophobic wood exhibiting water contact angles up to 161°, a phenomenon that highlights a significant hydrophobicity (cf. Section 3. Surface energy investigation techniques). Moreover, other studies on fluorine plasma treatments have also succeeded in increasing the hydrophobic character of lignocellulosic materials, such as wool and cotton fabrics treated with hexafluoroethane [80], wood fibers modified with CF4 and SF6 plasmas [81], and chemithermomechanical pulp (CTMP) sisal paper treated with fluorotrimethylsilane (CH3SiF) [82].

3. Surface Energy Investigation Techniques

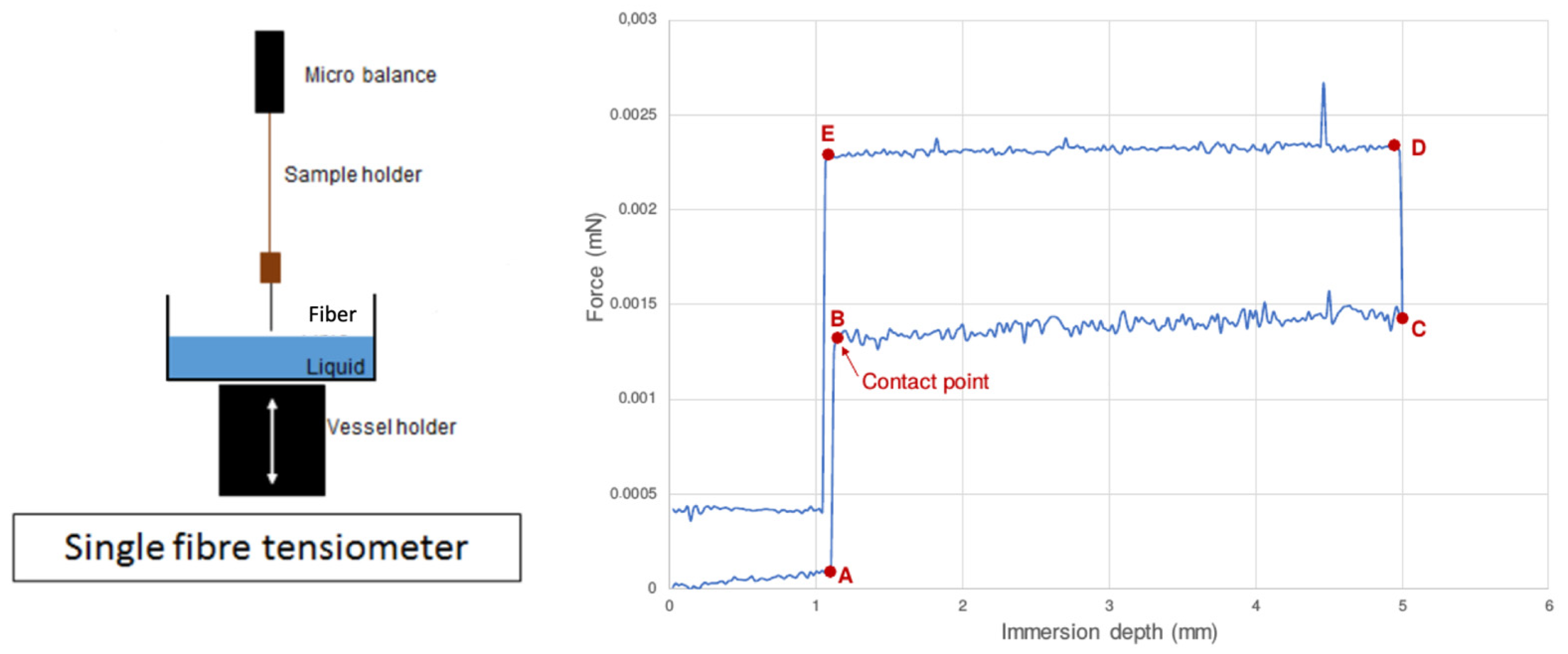

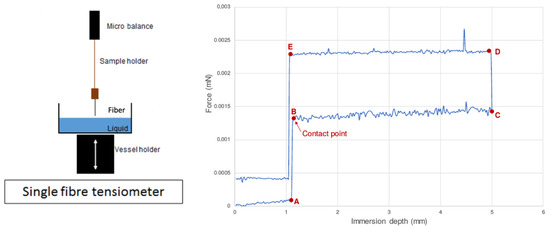

From the physico-chemical point of view, the adhesion of a matrix onto a fiber is driven by their compatibility in terms of respective surface energy. It remains challenging to reliably estimate the surface energy of fibers due to their dimensions and morphology. In any case, contact angle measurements between fibers and different liquids are necessary. Whereas the “sessile drop” technique is classically carried out [83], the cylinder shape of fibers increases the uncertainty and questions the reproducibility of positioning liquid drops on fibers. Thereby, in order to determine contact angles and then the surface energy of the flax fibers, another method must be carried out. Indeed, amongst the different techniques [84,85,86], the tensiometric method appears as the most suitable. Described by Pucci et al. [14,87,88] it is based on the use of a microbalance and the Wilhelmy relationship:

where F is the capillary force (mN), p (m) the wetted length, θ (◦) the contact angle and γliq (mN/m) the surface tension of the liquid. Measurements of capillary force were performed using a Krüss K100SF tensiometer, a single fiber tensiometer. A single fiber is attached to the probe and the capillary force is recorded all along the immersion and removal of the fiber from the test liquid. A pause of 60 s is also observed at the final immersion depth to let the meniscus and thus the contact angle to achieve equilibrium. An important phenomenon could influence the recorded capillary force, especially for natural or lignocellulosic fibers, is the swelling of the fiber in the liquid test. Indeed, especially in water, the diameter and thus the wetted length (p), might change during the test. To track this change, the perimeter can be characterized before and after the test to follow the morphological change in the fibers. The procedure has been described in previous work [14]. The profile of the obtained curves is given in Figure 4 and more precisely described in previous studies [14,87,88].

Figure 4.

Single fiber methodology: schematic description of the setup for a single fiber (left)—example of recorded force by the microbalance (right)—before point A, recording of a drift before contact between fiber and test liquid; between B and C, advancing stage; between D and E, receding stage [87].

Using data recorded at each point it is also possible to estimate contact angles using the Wilhelmy relation (Equation (1)) during the advancing and receding phase to gain information on the interface formation. From there, the Wilhelmy equation allowed the wetted length of the fibers to be determined. Then, knowing the wetted length and the tabulated γliq, the contact angle was determined using (Equation (1)) by measuring the force F exerted by the testing liquid on the fiber.

Thereby, two different liquids (water and diiodomethane from AlfaAesar, 99%, stab. with copper) were considered; the Owens–Wendt equation (Equation (2)) allowed the polar γp fiber and the dispersive component γd fiber of the surface energy of fibers to be identified [89,90].

4. Fluorination of Wood; Lignin as a Key Component

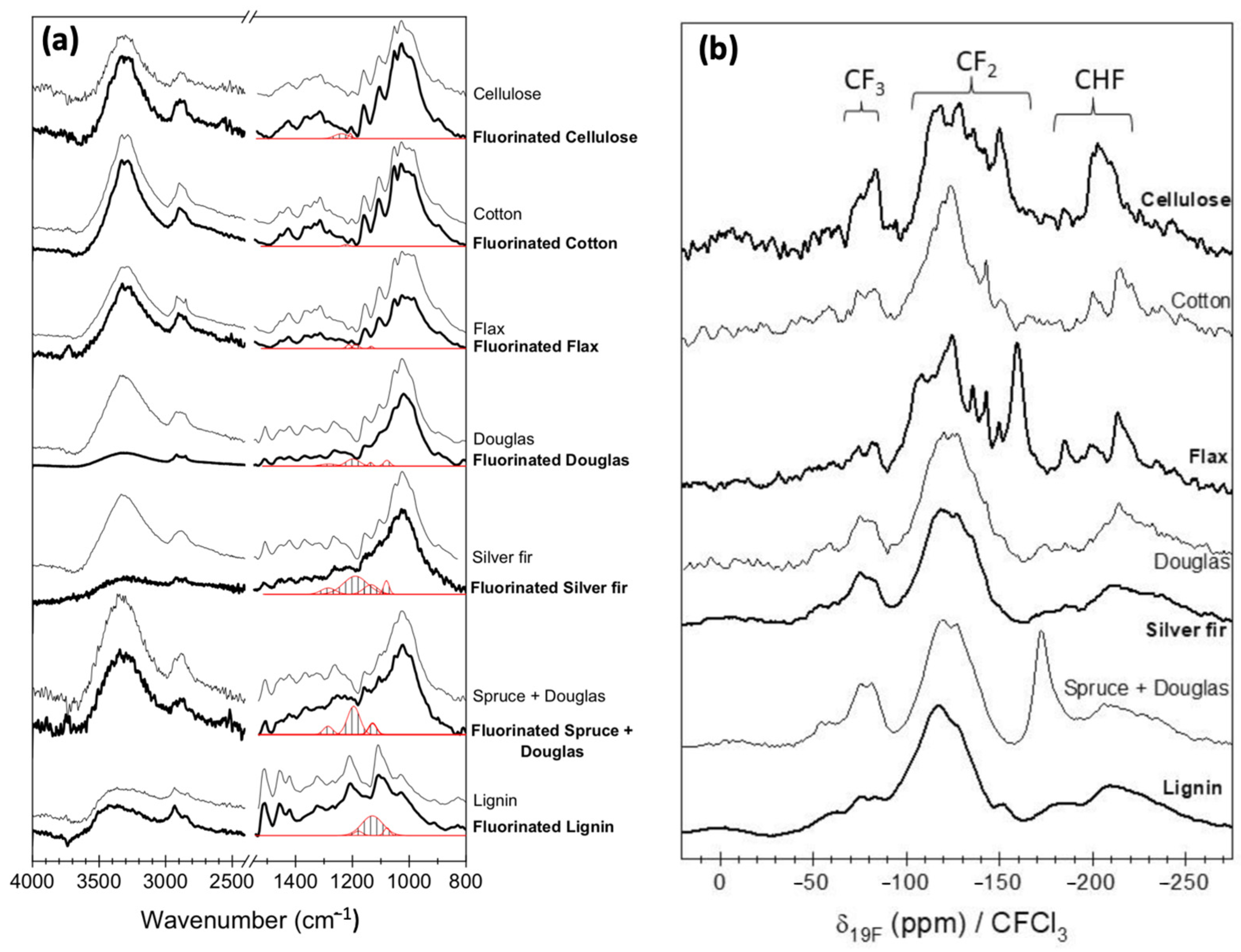

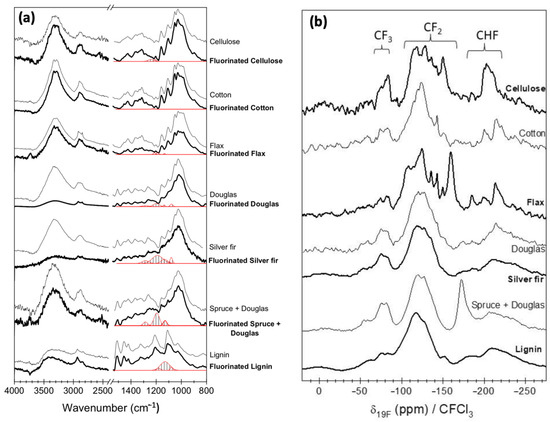

To investigate how the chemical composition of wood affects fluorination, Pouzet et al. [91] selected seven lignocellulosic substrates—cellulose, lignin, cotton, flax fibers, fir (Abies sp.), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and a spruce–Douglas mix. After degassing (1 h at 90 °C under ~10−3 mbar vacuum), these samples were statically exposed to 20 mbar pure F2 in a closed, passivated nickel reactor. FT-IR analysis (Figure 5a) of raw and treated samples showed new peaks at 1080, 1160, 1200, and 1280 cm−1—indicative of covalent C–F bond formation—and a reduction in the hydroxyl (–OH) band at 3000–3500 cm−1, confirming the substitution of C–OH with C–F groups, which reduce water affinity. 19F magic-angle-spinning NMR (Figure 5b) identified three fluorinated species: –CHF (−180 to −220 ppm), –CF2 (−100 to −160 ppm, indicating perfluoration), and –CF3 (−70 to −90 ppm, linked to chain scission via hyperfluoration) [92,93,94,95], thus confirming surface fluorine grafting by both FT-IR and NMR.

Figure 5.

FT-IR (a) and NMR spectra of untreated fibers (gray line) and fluorinated fibers (bold) (b) [92]. Red line display the vibration bands related to fluorinated groups.

As expected, fluorination reduced surface polarity by lowering the polar component of surface tension [96,97]. Contact angle measurements (Table 1) showed a significant increase in hydrophobicity for fluorinated lignocellulosic materials (though not for purely cellulosic ones like cotton or cellulose).

Table 1.

Water contact angle for different lignocellulosic materials.

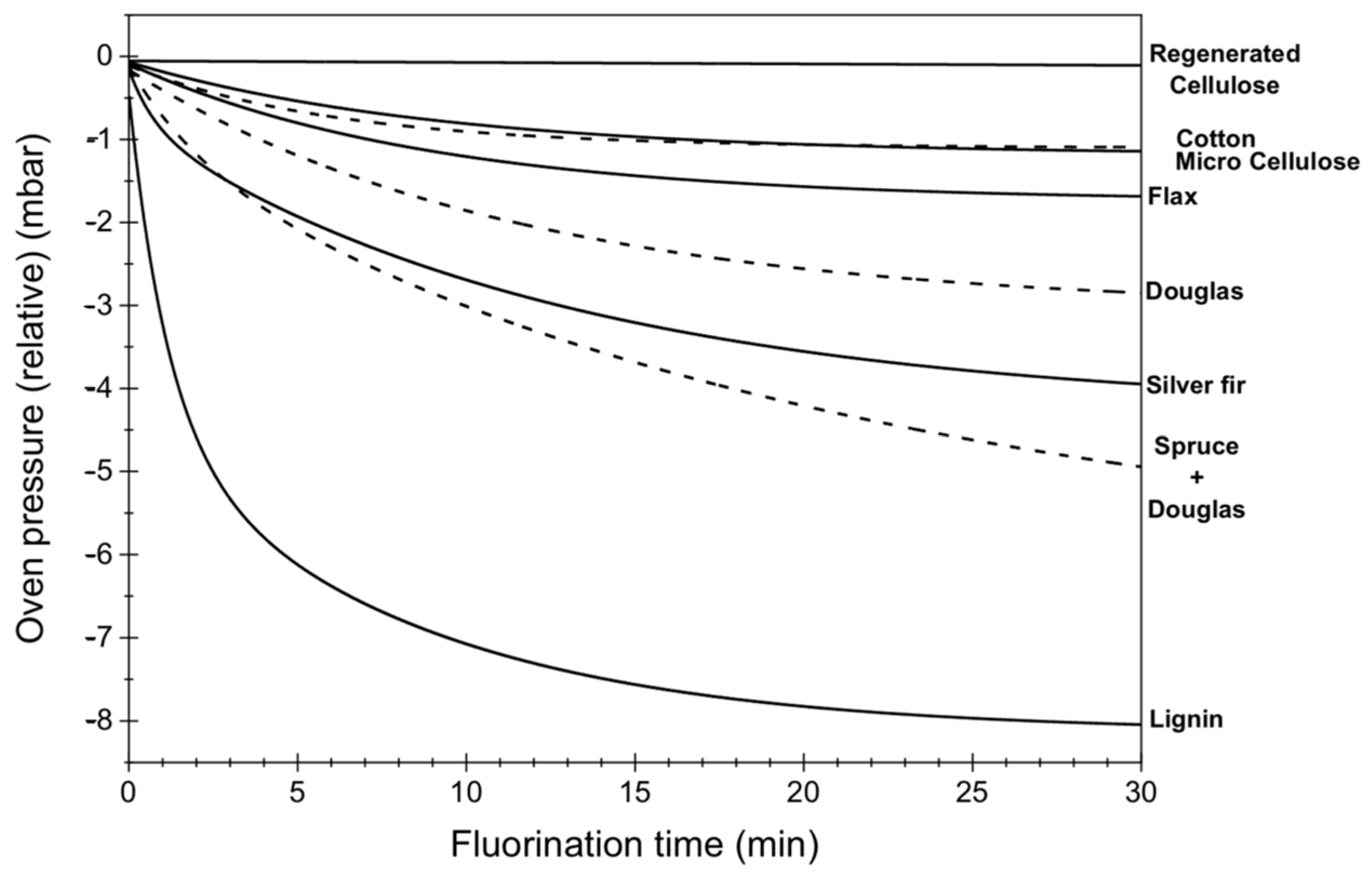

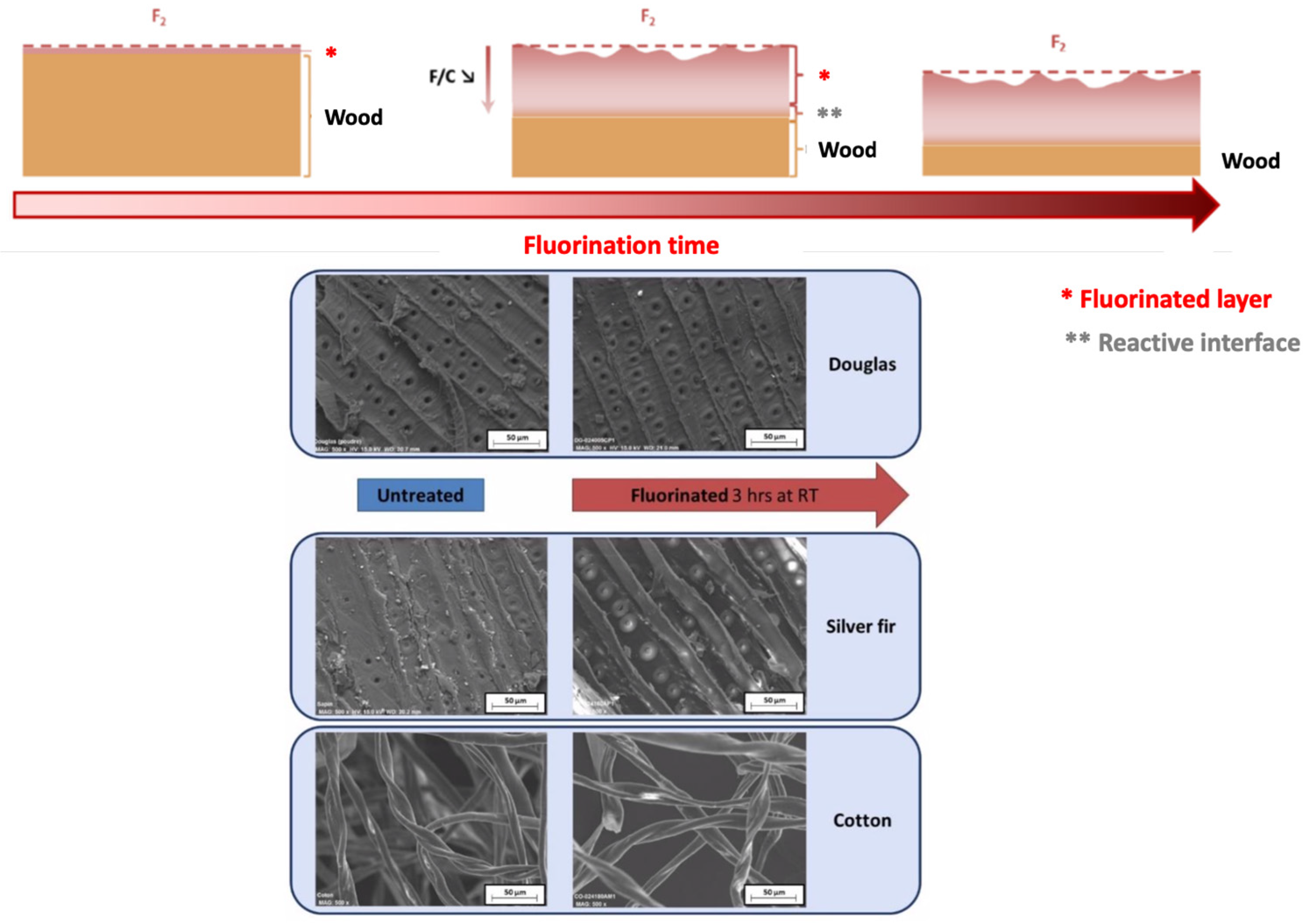

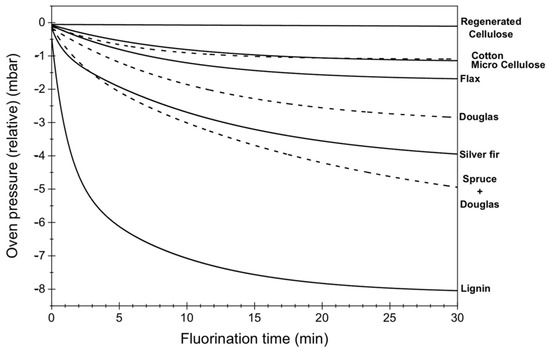

Furthermore, fluorinated wood samples subjected to 800 min at 30% and 60% relative humidity showed markedly lower moisture uptake compared to untreated samples, confirming enhanced water repellency [98]. Cellulosic materials resist fluorination more than lignocellulosic ones due to compositional differences. Wood is mainly composed of three primary components: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Cellulose typically accounts for 40–50% of the dry weight of wood. Hemicellulose represents about 20–30%, depending on the wood species. Lignin makes up approximately 20–30%. These relative proportions can vary depending on factors such as wood species (hardwood vs. softwood), age, and environmental growth conditions. Real-time pressure drops during static fluorination revealed the reactivity order: lignin > wood flour > fir > Douglas fir > flax > cotton > cellulose (Figure 6). This shows that lignin content correlates positively with fluorine reactivity, while cellulose inhibits the reaction [98]. FT-IR data (Figure 5a) support this, as greater –OH reduction is seen in lignin-rich fibers. Belov et al. [99] fluorinated acetyl-cellulose and ethyl-cellulose in perfluordecalin: 13C NMR showed negligible change compared to fluorinated cellulose, while 19F NMR indicated fluorination only on methyl and ethyl groups, not the glycopyranosyl rings—further confirming cellulose’s resistance. Thus, direct surface fluorination can substitute C–OH with C–F bonds—imparting hydrophobicity without altering bulk mechanical integrity. Indeed, lignocellulosic’s mechanical performance is mainly induced by cellulose [100] and therefore its low reactivity towards fluorination will prevent mechanical loss. Structurally, fluorination preferentially modifies outer wall layers (e.g., middle lamella, primary wall) rich in lignin while preserving the cellulose-dense S2 layer responsible for fiber rigidity and consolidates mechanical properties better than torrefaction, which sacrifices strength for hydrophobicity [44]. Extended fluorination can degrade carbon skeletons, indicated by CF3 formation [96,97,101]. However, 19F-NMR and SEM (Figure 7) analyses reported by Pouzet et al. [102] showed no significant CF3 or surface degradation after a 3 h treatment at ambient temperature, suggesting controlled fluorination can avoid damage. Finally, Pouzet [102] identified a saturation point: prolonged dynamic fluorination in open systems results in more –OH being removed than C–F bonds formed (offset by CF4 and C2F6 formation), leading to substrate deterioration and reduced hydrophobic and mechanical performance.

Figure 6.

Pressure evolution within the reactor during the fluorination process [92]. Dotted lines are related to Cotton, Douglas and Sprure+Douglas.

Figure 7.

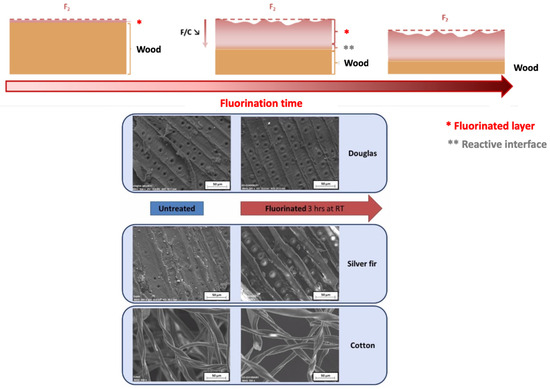

Scheme of the changes over fluorination time and SEM image of raw and fluorinated plant compounds [102].

The efficiency of plasma fluorination as for the gas (F2)/solid process [92] is closely linked to the relative proportions of lignin and cellulose within the fiber. Lignin plays a key role in facilitating the reaction, while cellulose tends to suppress it. A higher lignin content promotes faster and more effective fluorination, whereas an elevated cellulose fraction seems to hinder the process. To clarify how fluorination imparts hydrophobicity without significantly altering structure, it is useful to consider the microstructure for the representative case of wood, which consists of plant cells 10–100 μm in diameter, each surrounded by a multilayered cell wall composed of cellulose microfibrils embedded in hemicellulose and lignin. These layers—middle lamella (M), primary wall (P), and secondary wall layers (S1, S2, S3)—differ in their proportions of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Fluorination reactivity strongly depends on composition: lignin-rich regions react readily, whereas cellulose inhibits fluorination [92]. As a result, the middle lamella and primary wall, which contain the highest lignin content, consume fluorine first and become the main sites of covalent fluorine grafting. Under mild conditions (short exposure times or low F2 quantities), fluorinated groups such as CHF, CF2, and CF3 remain largely confined to the outer cell-wall layers, leaving the inner structure unmodified. SEM observations support this spatially localized reaction. Because fluorination under these mild conditions limits modification to the cell periphery, the mechanical properties of the wood are preserved—unlike thermal treatments commonly used to enhance hydrophobicity, which are known to degrade mechanical performance [103].

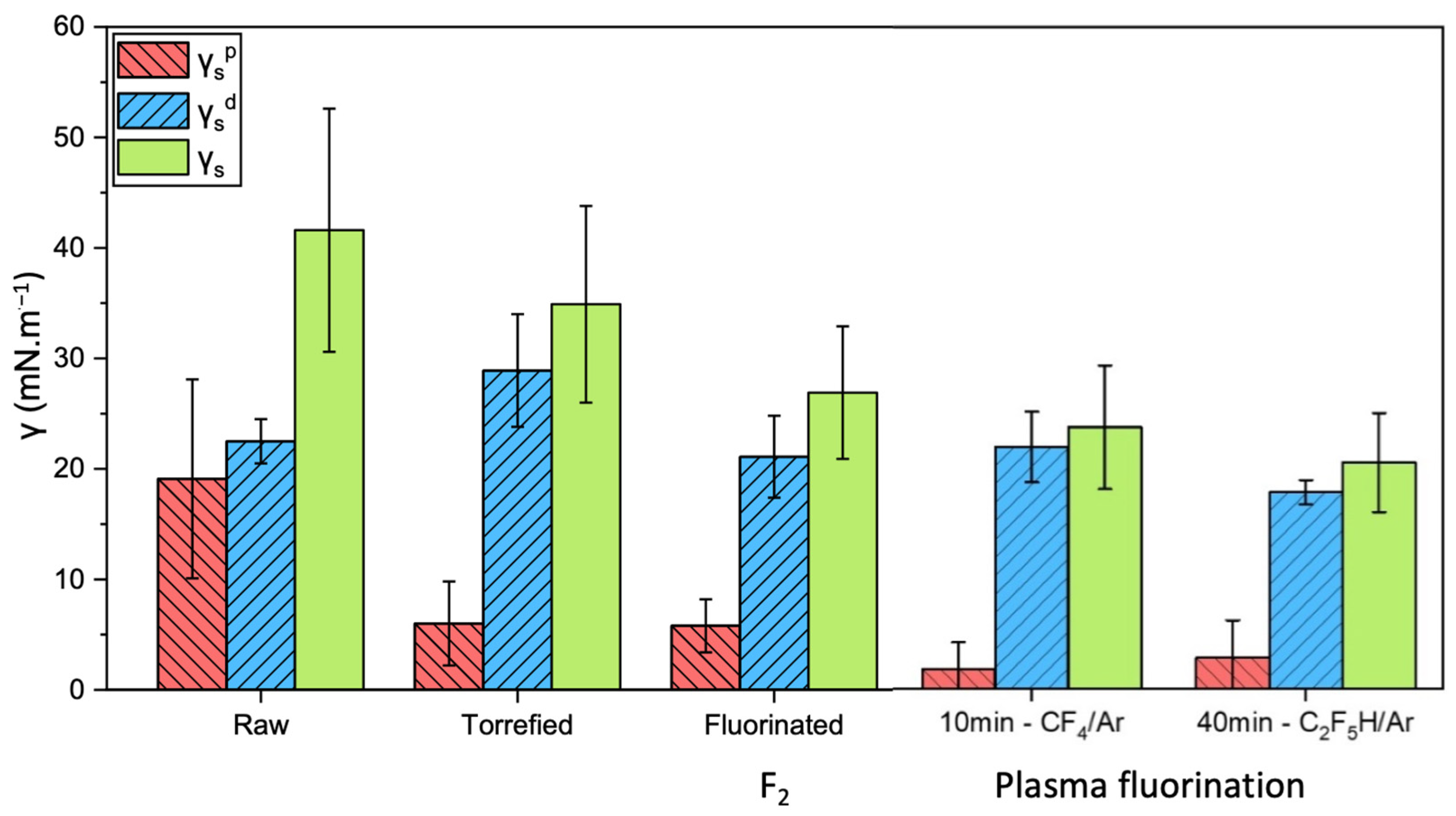

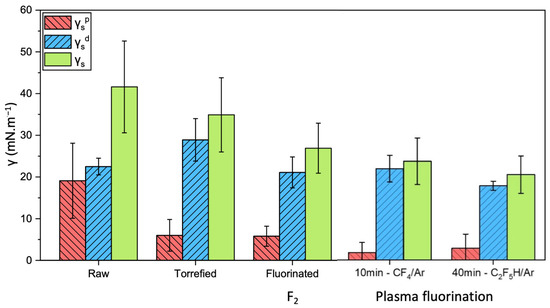

5. Fluorination of Natural Fibers, a Representative Example of Flax

In flax fibers, cellulose is the dominant component, typically ranging from 60 to 80% of the dry weight. Hemicellulose generally accounts for 10–20% whereas lignin is present in lower amounts, usually between 2% and 5% for wood pieces; controlled fluorination of flax fibers reduces their surface polarity (γsp), modifying their surface energy [104]. Similarly, torrefaction also decreases this polar component [14]. To assess these changes, tensiometric measurements were conducted (Figure 8). Untreated flax fibers exhibit high polarity (19.1 ± 9 mN·m−1). After torrefaction and fluorination, this drops significantly to 6.0 ± 3.8 and 5.8 ± 2.4 mN·m−1, respectively. These similar values suggest comparable fiber/matrix compatibility, enabling a direct comparison of their effects on composite mechanical performance without polarity being a biasing factor. Fluorination does not noticeably alter the dispersive component, which is associated with surface texture [105], indicating that the surface roughness is preserved during treatment. Moreover, fluorination reduces the variability (standard deviation) in polarity, highlighting its potential to homogenize the natural surface energy of plant fibers—a benefit also observed at lab scale. When well-controlled, both treatments thus offer industrial interest by improving fiber surface consistency. Comparing the polarities of treated fibers with common composite matrices—epoxy (γsp ≈ 5 mN·m−1) [88], polyethylene and polypropylene (γsp ≈ 0 mN·m−1) [106]—confirms strong compatibility with epoxy. Lower polarity differences improve fiber wetting, justifying epoxy as the matrix used. Additionally, the versatility of fluorination—via tuning parameters such as time, temperature, gas flow, or dilution—allows tailoring fiber polarity to match more hydrophobic matrices.

Figure 8.

Polar, dispersive and total surface energy of raw, torrefied and fluorinated flax fibers using molecular fluorine F2 and plasma. The figure combines data from references [97,106,107]

The susceptibility of natural materials like fibers and wood to external threats such as termites and fungi significantly limits their use and durability, as these biological agents can degrade the structural integrity of the materials. Moreover, recent regulations have banned certain conventional protective treatments because of their harmful effects on health and the environment. The protective effect of fluorination with F2 gas on flax fibers against termite and fungal attacks was demonstrated [108]. While surface fluorination alone provided significant biological resistance, introducing sodium fluoride (NaF) crystals or fluorinated silica nanoparticles into the fiber porosity allows protection to be enhanced.

With the same aim to improve the compatibility between naturally polar flax fibers and mainly dispersive polymers, plasma fluorination was carried out as well. Fluorine-contained plasmas are widely used in microelectronics due to their chemical efficiency. The fluorinated species produced in the plasma exhibit high electronegativity; they capture free electrons, reduce electron density, and can lead to plasma extinction. For this reason, a plasma composed exclusively of fluorinated gases is unstable and cannot be sustained. The literature generally reports a maximum fluorine-contained gas doping level of approximately 2% for an atmospheric plasma torch. Some systems are designed to explore a wider doping range, from 0 to 4%, in order to study the stability limits and the effects on the process. Two categories of parameters can be modulated: (i) torch parameters such as gas flow rates and mixing, excitation frequency, treatment time and (ii) process parameters such as in our roll-to-roll configuration, in which the substrate’s speed allows control of the contact time with the plasma. This flexibility allows for the optimization of the treatment conditions according to the material and the desired effects. Very high global warming potential (GWP) gases like CF4 and C2F5H were used as a fluorine source, particularly CF4, whose atmospheric lifetime exceeds a thousand years. Their use in plasma processes therefore requires particular attention regarding their management, downstream disposal, and the reduction in fugitive emissions. In this approach, the use of CF4 or C2F5H in fluorination plasmas is intended to be beneficial; it consists of valorizing residual gases from other industrial processes by reusing them as a source of fluorine rather than releasing or treating them solely as waste. Their high fluorine density per molecule and their gaseous state at room temperature make them excellent precursors for generating fluorinated plasmas. The plasma allows these very stable molecules to be fragmented in order to extract the reactive fluorinated species necessary for the fluorination of the substrate. However, rigorous optimization of plasma conditions remains essential in order to minimize the presence of undissociated CF4 or C2F5H in effluents and to limit the formation of undesirable byproducts, particularly HF, which must be properly neutralized in abatement systems.

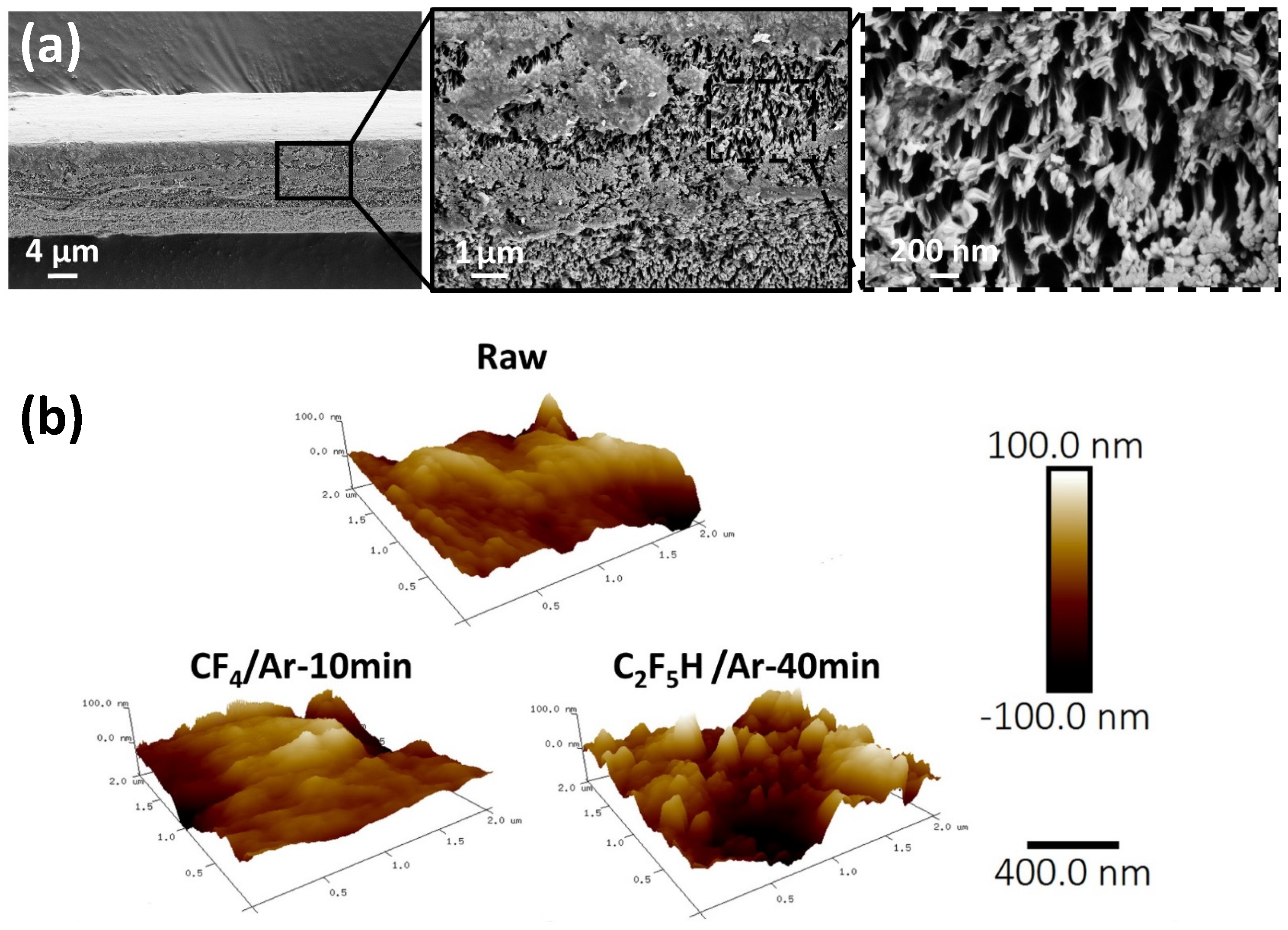

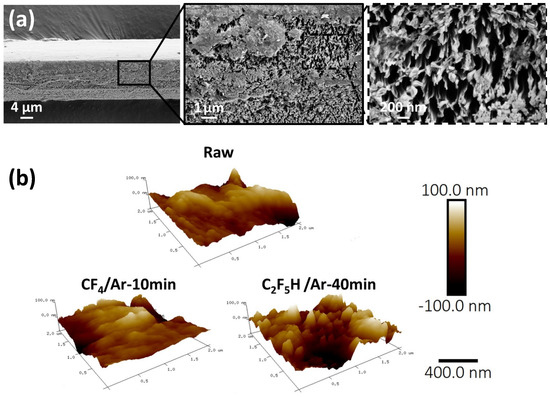

Chemical analyses (FT-IR, 19F NMR, XPS) confirmed covalent fluorine grafting, enabling precise surface chemistry modification [108]. Unlike direct fluorination, plasma fluorination enables precise control over surface chemistry—particularly the relative amount of CF3 groups—by selecting the appropriate precursor gas. Like other surface treatments, plasma processes are known to affect substrate morphology [79,109], potentially inducing degradation, etching, swelling, or delamination. In composite materials, moderate surface roughness is generally beneficial, as it enhances mechanical interlocking between fiber and matrix, improving adhesion. However, excessive roughness may lead to surface damage, reduced wettability, or ineffective anchoring. To assess the impact of fluorination on flax fiber surface morphology, SEM and AFM analyses were conducted (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

(a) SEM pictures of etched fibers by CF4/Ar for 10 min plasma treatment and zoom on etched area and (b) AFM pictures of raw and treated flax fibers [108].

For Ar-only plasma treatments, significant surface roughness was observed, indicating that Ar contributes to surface etching. When Ar are present in addition to CF4 or C2F5H, the plasma likely generates radicals (F• and CF2•, CF3•, CF•). For C2F5H/Ar plasma, CF3•, CHF2• and to a lesser extent F•, CF3CHF• and CHF• are formed. In contrast, C2F5H/Ar-treated fibers show no clear morphological changes in SEM images at 2000× magnification, regardless of treatment duration [108]. For CF4/Ar treatment, despite literature reports of strong etching with CF4 [110], most fibers appear largely intact, with only a few showing localized surface damage [108] (Figure 9). These observations were confirmed by AFM at the nanoscale (Figure 9); raw fibers show Ra = 21.2 nm and Rq = 28.0 nm, while CF4/Ar-treated fibers present similar values (Ra = 19.7 nm; Rq = 26.2 nm). This suggests that although Ar induces etching, it may also smooth the surface via decomposition mechanisms that counteract roughening during CF4/Ar plasma treatment. This smoothing effect may stem from concurrent etching and fluorination, which can lead to the release of CF4 and C2F6 gases [110]. In contrast, fibers treated with C2F5H/Ar exhibit increased surface roughness (Ra = 27.5 nm; Rq = 33.6 nm), suggesting a more pronounced nanometric etching. This may result from the combined action of Ar and C2F5H, or from limited surface decomposition during fluorination. Given this increased roughness, C2F5H/Ar treatment appears particularly promising for enhancing fiber–matrix mechanical interlocking in composites. Similar plasma etching strategies have been successfully applied to other natural fibers, consistently improving mechanical properties such as flexural and tensile strength across various processing methods [65,66,67,68].

The plasma treatment reduced fiber polarity (Figure 8) whatever the gases, whether CF4 or C2F5H. For the CF4/Ar plasma during 10 min and C2F5H/Ar during 40 min fluorinated samples, the polar component dropped significantly from 19.1 ± 9.0 mN/m (raw fibers) to 1.8 ± 2.4 mN/m and 2.8 ± 3.4 mN/m [108], respectively. This reduction enhances compatibility with dispersive polymers and is expected to improve composite mechanical properties, as confirmed by previous studies.

Similar results were obtained by Xie et al. [79] using C2F5H/Ar plasma treatment, allowing the contact angle to increase between wood (Golden chinkapin or Castanopsis chrysophylla) and water to 140.3 ± 2.2°. This demonstrated that a large variety of natural substrate can be treated using this technique.

Additionally, while direct fluorination leaves surface roughness uncontrolled, plasma treatment allows roughness tuning through Ar-induced etching. Mechanically, all plasma-treated samples show a reduction in both stress and strain at break, along with a slight decrease in Young’s modulus.

Finally, mechanical testing and fluorine release during fiber combustion showed no adverse effects. Plasma fluorination thus narrows the surface energy gap between fibers and polymer matrices, improving fiber wettability in an eco-friendly manner and promising enhanced performance for eco-composites reinforced with fluorinated flax fibers.

6. Applications

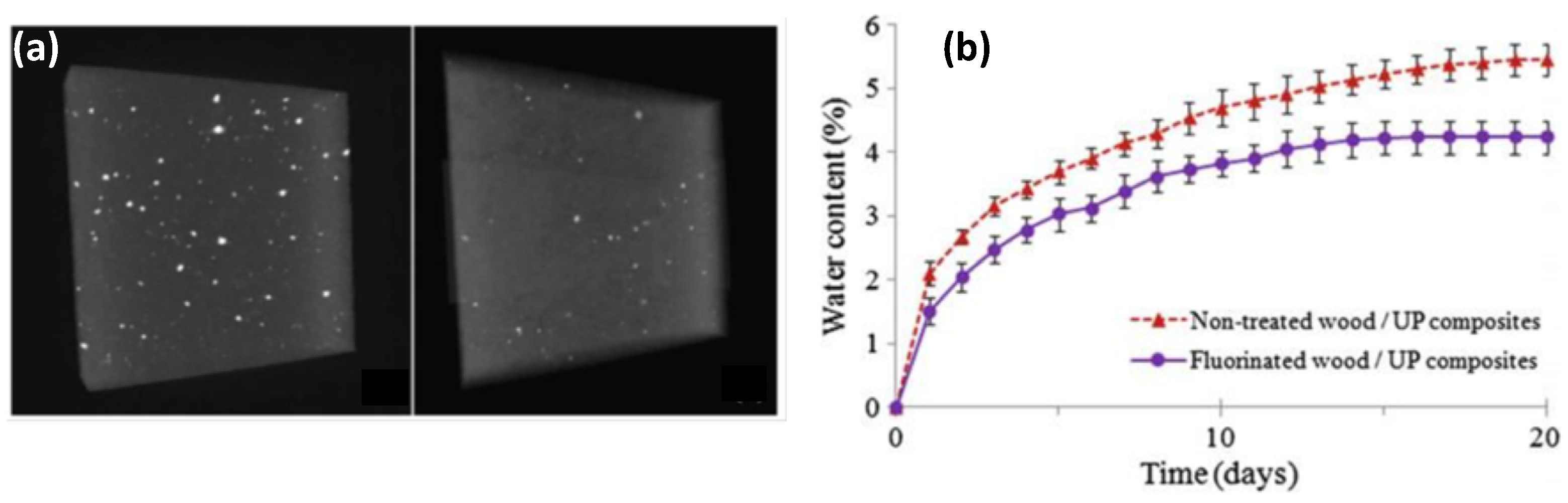

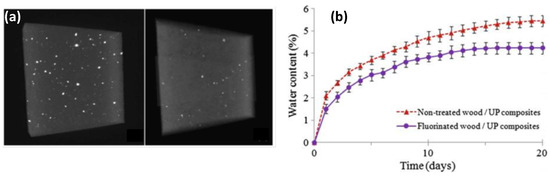

To evaluate the impact of fluorination on lignocellulosic materials for reinforcing dispersive polymers, Saulnier et al. [111] fluorinated wood flour (a spruce and Douglas fir blend) from sawmill byproducts in Auvergne, France, with particle sizes under 250 μm. Composites were prepared by mixing the fluorinated wood flour with polyester resin (Norsodyne G703) at 45 wt% filler, molded at 80 °C under 60 kN for 2 h. Covalent grafting of fluorine was confirmed by 19F NMR and FT-IR, showing similar spectral features as previous lignocellulosic materials. X-ray tomography revealed that composites reinforced with untreated wood flour exhibited higher porosity than those with fluorinated fillers (Figure 10a). Given the same processing conditions, reduced porosity is attributed to improved filler wettability due to fluorine surface groups, enhancing polyester–filler compatibility, consistent with observations from torrefaction treatments on flax fibers [14]. Porosity is a known crack initiation site, so reduced porosity suggests improved mechanical performance. Mechanical tests [112] showed increased composite stiffness (Young’s modulus) and tensile strength after fluorination, while elongation at break remained unchanged. This indicates better filler–matrix interface quality and more efficient load transfer. The magnitude of improvements is comparable to those reported by Garcia et al. [113] for maleic anhydride treatment and Nachtigall et al. [114] for silane treatment, highlighting the effectiveness of direct fluorination as a dry, solvent-free alternative for eco-composites. After 20 days at 20 °C and 80% relative humidity, fluorinated composites absorbed less moisture than untreated ones (Figure 10b). Flexural tests post-aging showed that fluorinated samples retained superior Young’s modulus (5.8 ± 0.5 and 7.8 ± 0.4 MPa, for raw and fluorinated samples, respectively) and tensile strength compared to untreated samples (50.6 ± 0.4 and 59.2 ± 3.4 MPa), possibly due to continued polyester matrix curing facilitated by humidity [115,116]. The fluorine layer may also provide some water protection, though the initially better mechanical properties of fluorinated composites complicate definitive conclusion.

Figure 10.

(a) Three-dimensional reconstruction of untreated polyester–wood composite samples (left) and fluorinated polyester–wood composite samples (right) after X-ray tomography scanning [117]; (b) evolution of water absorption in composites made from fluorinated or non-fluorinated wood flour [112].

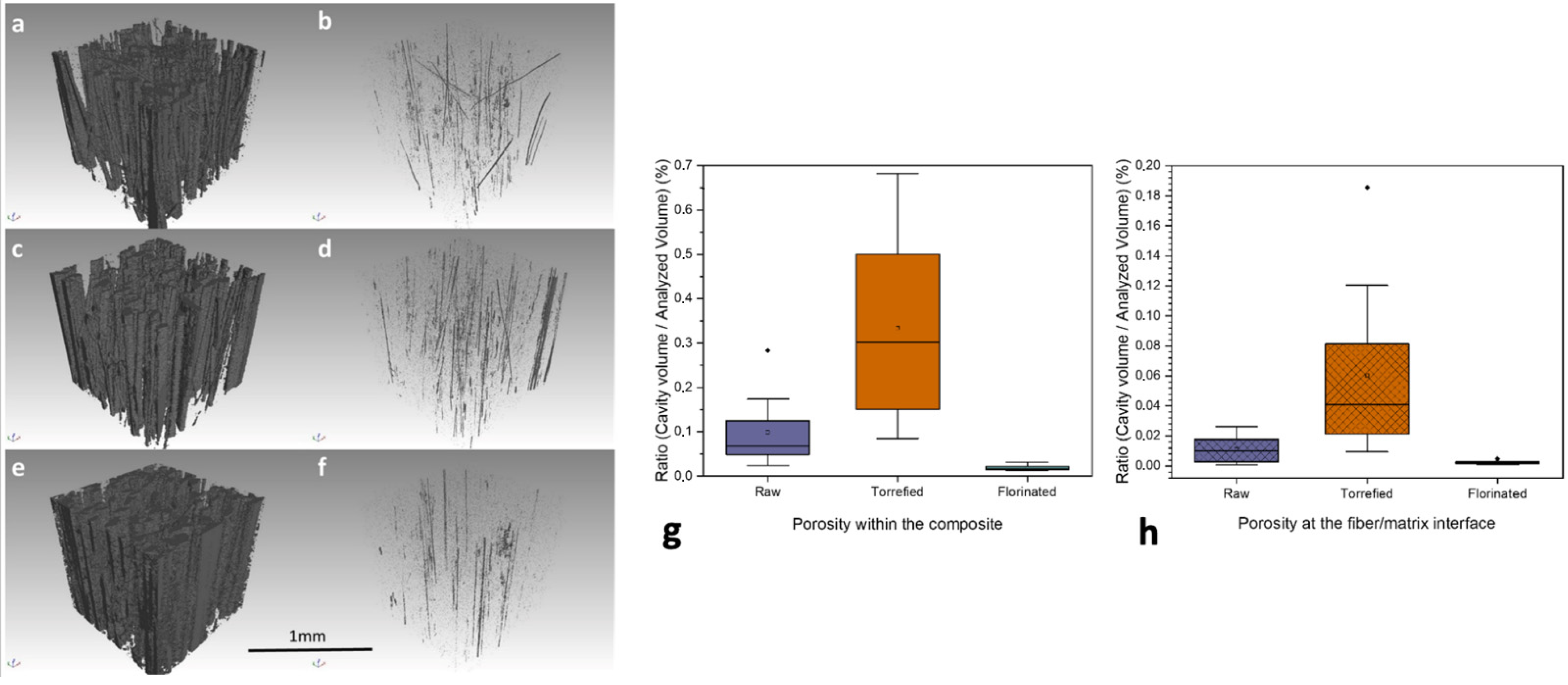

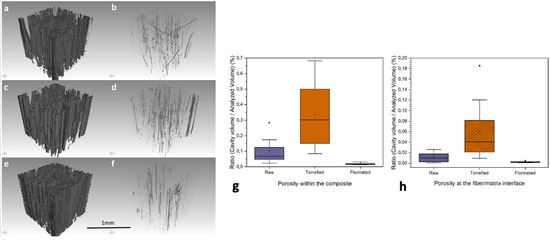

Tensile tests on composites reinforced with raw and treated flax fibers showed that the Young’s modulus remained stable regardless of the treatment. In contrast, both the ultimate tensile strength (σm) and elongation at break (A%) declined—moderately with fluorinated fibers and more markedly with torrefied ones. Three-point bending tests revealed a 30% increase in flexural modulus for composites with fluorinated flax fibers. Composites with torrefied fibers also showed improvement, but only by 10%, likely due to fiber [104]. The fluorinated flax fiber composite shows significantly lower overall and interfacial porosity than the raw fiber one, indicating improved compatibility with the epoxy (Resoltech 1050) matrix. Using Ilastik software based on the work of Berg et al. [118], X-Ray tomography observation post-treated using machine learning specifically trained to identify porosity in this kind of specimen confirmed reduced interface porosity (Figure 11). Conversely, torrefied fiber composites exhibit increased porosity (Figure 11g,h), possibly due to non-representative sampling or decompatibilization effects, despite the literature suggesting otherwise [14]. Mechanical tests should clarify this. Fiber content measured by AI varies between 20 and 30%, with minor differences attributed to sampling. The fiber volume fraction is about 25% (V/V).

Figure 11.

Three-dimensional reconstruction and visualization of fibers and micrometric pores for raw ((a) and (b), respectively), torrefied ((c) and (d), respectively) and fluorinated ((e) and (f), respectively) flax fibers reinforcing the epoxy resin; porosity rate (g) within the composite and (h) at the fiber/matrix interface; composite with epoxy resin [104].

The direct and quantitative comparison of fluorination efficiency with the other modification methods (acetylation, alkaline treatment, torrefaction) is very difficult. To be credible, this comparison should be made on the same fibers or wood, with the same fiber preparation before treatment. Such comparison was carried out between fluorination and torrefaction for the same flax fibers [90]. Under the torrefaction conditions selected based on the optimized treatment proposed by Berthet et al. [119] to enhance fiber–matrix adhesion in a biocomposite, fluorination reduces the fiber polarity far more effectively than torrefaction. The respective values are 6.4 ± 0.1 mN/m for fluorination and 19.8 ± 8.2 mN/m for torrefaction. In addition, it also has been proved that the resulting mechanical properties can depend on the manufacturing process. While a reliable comparison of the mechanical properties of similar reinforcements with similar morphologies (fabrics with same weaving, particles with similar shapes) with different sizing and comparable (or not to see the differences) manufacturing conditions would be of first interest, it does not yet exist. It would be hazardous to compile results from several studies without discussing the manufacturing parameters.

7. Scalability, Durability of the Fluorination Treatment and Possible Release of Fluorinated Species in the Environment

Both direct fluorination and plasma fluorination can be used on an industrial scale. Direct fluorination with gaseous F2 is already in play in the industry, particularly in the polymer sector, where it enhances barrier properties and makes surfaces more hydrophobic. Several companies have set up continuous or batch fluorination reactors, proving that this process can be scaled effectively when the material’s shape and reactivity are carefully managed. However, rolling out direct fluorination in an industrial setting comes with significant safety challenges, as fluorine gas is extremely reactive, corrosive, and can release heat. To scale up, specialized equipment, materials that can resist corrosion, and precise control over fluorine concentration, pressure, and exposure time are needed. These requirements can drive up costs and complicate treatment for highly porous or thermally sensitive materials like wood or carbon materials with a large surface area. In these situations, uncontrolled reactions might cause degradation, over-fluorination, or even structural collapse. On the other hand, plasma fluorination is also a viable option for industrial use and is already being utilized for modifying the surfaces of polymers, membranes, and powders. Plasma processes can operate at low or atmospheric pressure and generally provide better control over how deep and intense the fluorination is. They tend to be safer than direct fluorination since they use diluted fluorine-containing gases and create reactive fluorine species on-site. However, plasma treatments usually only affect the very top layer of a surface, which can be a limitation when deeper fluorination or uniform modification of porous materials is needed. For materials with intricate shapes or internal porosity, achieving consistent fluorination is still a challenge.

During prolonged contact with water, fluorine may be released from the fluorinated lignocellulosic materials into the liquid if it is labile or if HF molecules are present. While the first hypothesis is unlikely due to the covalent nature of the C–F bonds created, HF may be trapped in the porosity and then released through an opening in the porosity (swelling). It was therefore necessary to verify this important point by means of a measurement using a specific fluoride ion electrode. Two pieces of 1050 resin-based composite reinforced with fluorinated flax, weighing 1.246 g and 1.030 g, respectively, were first dried in an oven for 24 h before being immersed in a 25 mL Teflon beaker filled with deionized water. In order to maximize the release of fluoride into the water and toughen the test conditions, the composites were cut into two lengths and two widths to maximize contact between the fibers and the water. Using a fluoride ion-selective membrane electrode (with lanthanum fluoride crystal), the F- ion concentration was measured in accordance with standard NF T90-004 (Water quality—Determination of fluoride ion—Potentiometric method. NF T90-004, August 2002). The F- ion release rate after 24 h immersion of the composites in sample 2 (0.32 mg/L) is almost twice that of sample 1 (0.57 mg/L), highlighting a very high degree of variability. Worldwide, the maximum F-ion concentration recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) is 1.5 mg/L in drinking water [120]. While fluoride ions are beneficial to dental health in particular, an excess can cause dental fluorosis (attack on the enamel by F-ions, resulting in yellow to brown spots depending on the severity). While many countries, such as Australia, Canada, and India [121], follow this recommendation, others, such as the US [122] and Tanzania [121], have set slightly higher limits of 4 mg/L and 8 mg/L, respectively. In France, the limit is set at 1.5 mg/L by the decree of 11 January 2007, relating to the limits and quality references for raw water and water intended for human consumption mentioned in Articles R. 1321-2, R. 1321-3, R. 1321-7, and R. 1321-38 of the Public Health Code. In any case, our composites release F- ions at a concentration three times lower than that recommended by the World Health Organization and imposed by the French government for drinking water. One can reasonably assume that the release of F- ions from our composites remains limited and poses no danger to the population. This fluoride ion dosage validates a posteriori the elimination of HF molecules included in our fluoridation protocol. This is equally important information, given the legitimate reluctance of the population towards hydrofluoric acid.

In order to test whether fluorinated compounds could be emitted during combustion of the treated fibers, thermogravimetric analyses were conducted in air. The differences in the TGA curves between raw and fluorinated fibers are very small, and very little fluorine species were emitted [90]. TGA coupled with mass spectrometer evidenced the absence of large fragments; only the H2O (m/z = 18), CO (m/z = 28), and CO2 (m/z = 44) peaks (along with their isotopic counterparts) were detected. This indicates that C–F bonds are being cleaved rather than large fluorinated gas fragments (CF4, C2F6, etc.) being released. Accordingly, the analysis of the m/z = 19 (F) and 69 (CF3) fragments underlined that CF3 was emitted in only trace amounts, and solely around 350 °C—its quantity is so small that it is almost negligible.

The high durability of this treatment was determined by aging tests under ambient atmosphere [39]. For Douglas and silver fir wood species, the contact angle between water and treated wood was still unchanged between 110 and 120° even 2 years after treatment.

When exposed to air atmosphere, COF groups transform into carboxylic acid (COOH) groups within the first few hours following fluorination. Despite the presence of fluorine, the polar component of the surface energy increases. As demonstrated considering the fluorination of polypropylene, applying a post-fluorination esterification treatment of the COF groups with an alcohol in the gas phase, the surface chemistry can be stabilized, thereby preventing hydrolysis [123]. Surfaces subjected to this additional step are less hydrophilic than those treated solely by direct fluorination. The post-esterification is very promising for the fluorination of lignocellulosic materials.

8. Conclusions and Prospects

The strategy of fluorination applied to wood and natural fibers involves either treatment with elemental fluorine (F2) or plasma fluorination, processes widely used at the industrial scale to enhance the surface properties of polymeric materials [69]. When performed under controlled conditions, this chemical modification affects only the outermost surface of the substrate (typically ~0.01–10 µm deep for direct fluorination and several nanometers for plasma fluorination), leaving the bulk properties (e.g., Young’s modulus, biodegradability) unchanged [67,69,105,124]. Among the various benefits of this fluorinated layer—such as reduced permeability to hydrocarbons and other compounds, improved friction and chemical resistance [69,71,101]—the most relevant in the context of eco-composites is the reduction in material polarity [72,96,97,105,125]. Additionally, this gas/plasma–solid heterogeneous reaction can be performed without toxic solvents, in a closed reactor system, with no toxic emissions and no heating required, thus minimizing energy consumption and environmental impact. The method is also rapid, solvent-free, contactless, and reproducible, making it highly suitable for an eco-friendly industrial approach to reducing the polarity of plant-based fibers.

The lignin content in natural fibers plays a key role in determining their mechanical, thermal, and interfacial properties when used in bio-based composites [110,126,127,128,129]. The higher the lignin content, the higher the reactivity towards fluorine gas [91]. Among the most widely used natural fibers, flax contains a relatively low amount of lignin, typically ranging from 2 to 5 wt% [130]. Other fibers with higher lignin content than flax would be considered for hydrophobic surface, such as hemp (3.7 to 10 wt%, depending on the variety and processing conditions [130]), jute fibers (generally 11.8–13 wt% lignin), sisal (around 8–14 wt% [130]), coconut coir fibers (between 40 and 45 wt% [130]), bamboo fibers (between 21 and 31 wt%), and sugarcane bagasse (approximately 25 wt%) [130]. Their reactivities towards fluorine gas and plasma are expected to be high. On the other hand, cotton fibers, which are primarily cellulose-based, contain a negligible amount of lignin—typically less than 0.5 wt% [131]. These criteria are essential when selecting suitable fibers for specific applications, particularly when interfacial adhesion and biodegradability are key considerations. Fluorination can be used to adjust this adhesion. Lignin fibers, potential low-cost sources of carbon fibers [132,133], are currently produced either by melt spinning (an energy-intensive method) or by wet spinning (using toxic organic solvents). Innovative dry-, wet- and electro- spinning approaches may be used, in which only water as a solvent and lignin modified through enzymatic engineering are involved. As demonstrated by Mano et al. [134], lignin treated with the enzyme BOD exhibits high solubility in water, facilitating its fiber spinning. However, considering the intended applications, the surface energy of the fibers must be modified to make them hydrophobic. Fluorination can be a promising route.

For composites based on natural fibers or fluorinated lignin, long fibers must be processed continuously. This allows for an interesting treated volume for industrial applications. The plasma methods presented above, such as PVD, are not suitable for treating large volumes and large objects due to the size of the enclosures and vacuum management. DBD can treat large quantities, but the energies involved are lower than for the plasma torch, which does not allow for deep and homogeneous treatment of the fiber surface. This is why the plasma torch is a good candidate for the treatment of lignin fibers for industrial applications and is easy to implement. It is a flow of partially or totally ionized gas, generated by the application of electrical energy to a gas, thus creating a highly reactive plasma. Non-thermal plasma jet (cold plasma), operating at low temperatures (from room temperature to about 2000 K), is ideal for surface modification of lignin fibers or powder. Commonly used gases are helium (He), argon (Ar), oxygen (O2), nitrogen (N2), air, and fluorinated gases such as CF4, SF6, or NF3, which could be added to graft fluorine. A liquid of fluorinated molecules can be used as a fluorine source (fluorinated solvents like fluorinated alcohols or acids, and organofluorine compounds as fluorinated silanes (e.g., tridecafluoroctyltrimethoxysilane, FAS-17). Only non-PFA (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) precursors will be used; e.g., acid hexafluoroisopropanol and trifluoroacetic acid are not retained. PFAS are defined by the presence of CF2 groups with the chain and terminal CF3 group in their molecular structure. While traditional perfluoropolyether PFPEs (like Krytox™, Fomblin™, and Demnum™) are technically PFAs (since they contain perfluorinated carbon chains), some newer PFPE-based alternatives are being developed to comply with PFA-free regulations by modifying their structure to be more degradable or lacking bioaccumulative PFAs. This type of precursor must be avoided because of its cost.

This review highlights the potential of fluorination applied to lignocellulosic materials, in particular for eco-composites. This surface treatment is still underutilized up to now.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D., O.T., T.F., A.B., E.T., M.F.P., P.-J.L., Y.A., K.C. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., O.T., T.F., A.B., E.T., M.F.P., P.-J.L., Y.A., K.C. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, A.D., O.T., T.F., A.B., E.T., M.F.P., P.-J.L., Y.A., K.C. and M.D.; supervision, M.D. and K.C.; project administration, K.C. and M.D.; funding acquisition, K.C. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project called FLIGHT is funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR for the funding (PROJET N° ANR-25-CE43-0830). This work was also financially supported by the Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes through the FLUONAT Project, and encouraged by Solvay Group.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The company Solvay Group had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Charlet, K. Contribution à l’étude de Composites Unidirectionnels renforcés par des fi-bres de lin: Relation entre la Microstructure de la fibre et ses propriétés mécaniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Caen, Caen, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Oqla, F.M.; Salit, M.S. Natural Fiber Composites. In Materials Selection for Natural Fiber Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal, J.S. Natural Fibers: Applications. In Generation, Development and Modifications of Natural Fibers; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbery, J.; Houston, D. Natural-fiber-reinforced polymer composites in automotive applications. JOM 2006, 58, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambua, P.; Ivens, J.; Verpoest, I. Natural fibres: Can they replace glass in fibre reinforced plastics? Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudood, A.; Rahman, A.; Öchsner, A.; Islam, M.; Francucci, G. Flax fiber and its composites: An overview of water and moisture absorption impact on their performance. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2019, 38, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-M.; Lai, W.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y. Effects of Surface Modification on the Mechanical Properties of Flax/β-Polypropylene Composites. Materials 2016, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, M.; Abdan, K.; Jawaid, M.; Nasir, M.; Dashtizadeh, Z.; Ishak, M.R.; Hoque, M.E. A Review on Pineapple Leaves Fibre and Its Composites. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 2015, 950567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Jeon, H.-Y. (Eds.) Generation, Development and Modifications of Natural Fibers; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Chouw, N.; Jayaraman, K. Flax fibre and its composites—A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 56, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlet, K.; Baley, C.; Morvan, C.; Jernot, J.P.; Gomina, M.; Bréard, J. Characteristics of Hermès flax fibres as a function of their location in the stem and properties of the derived unidirectional composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2007, 38, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlet, K.; Jernot, J.-P.; Gomina, M.; Bizet, L.; Bréard, J. Mechanical Properties of Flax Fibers and of the Derived Unidirectional Composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2010, 44, 2887–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baley, C.; Bourmaud, A. Average tensile properties of French elementary flax fibers. Mater. Lett. 2014, 122, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, M.F.; Liotier, P.-J.; Seveno, D.; Fuentes, C.; Van Vuure, A.; Drapier, S. Wetting and swelling property modifications of elementary flax fibres and their effects on the Liquid Composite Molding process. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 97, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, H.N.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Richardson, M.O.W. Effect of water absorption on the mechanical properties of hemp fibre reinforced unsaturated polyester composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotirat, L.; Chaochanchaikul, K.; Sombatsompop, N. On adhesion mechanisms and interfacial strength in acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene/wood sawdust composites. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2007, 27, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazayawoko, M.; Balatinecz, J.J.; Matuana, L.M. Surface modification and adhesion mechanisms in woodfiber-polypropylene composites. J. Mater. Sci. 1999, 34, 6189–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klason, C.; Kubát, J.; Strömvall, H.E. The Efficiency of Cellulosic Fillers in Common Thermoplastics. Part 1. Filling without Processing Aids or Coupling Agents. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 1984, 10, 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Célino, A.; Freour, S.; Jacquemin, F.; Casari, P. The hygroscopic behavior of plant fibers: A review. Front. Chem. 2014, 1, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Biomass-Based Formaldehyde-Free Bio-Resin for Wood Panel Process. In Handbook of Composites from Renewable Materials; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ratna, D. Handbook of Thermoset Resins; iSmithers: Shawbury, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, J.E. Polymer Data Handbook, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.-J. Recent Uses of Carbon Fibers. In Carbon Fibers; Park, S.-J., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 241–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kesarwani, S. Polymer Composites in Aviation Sector. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skita, A.; Keil, F. Basenbildung aus Carbonylverbindungen. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1928, 61, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Piao, C. From hydrophilicity to hydrophobicity: A critical review-part II: Hydrophobic conversion. Wood Fiber Sci. 2011, 43, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.; Joseph, K.; Thomas, S. Effect of surface treatments on the electrical properties of low-density polyethylene composites reinforced with short sisal fibers. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1997, 57, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.P.S.A.; Rozman, H.D.; Ahmad, M.N.; Ismail, H. Acetylated plant-fiber-reinforced polyester composites: A study of mechanical, hygrothermal, and aging characteristics. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2000, 39, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, R.M.; Dickerson, J.P. Acetylation of Wood. In Deterioration and Protection of Sustainable Biomaterials; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume 1158, pp. 301–327. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tabil, L.G.; Panigrahi, S. Chemical Treatments of Natural Fiber for Use in Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2007, 15, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peças, P.; Carvalho, H.; Salman, H.; Leite, M. Natural Fibre Composites and Their Applications: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2018, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, A. Plasma Chemistry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Shaker, K.; Nawab, Y.; Jabbar, M.; Hussain, T.; Militky, J.; Baheti, V. Hydrophobic treatment of natural fibers and their composites—A review. J. Ind. Text. 2018, 47, 2153–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Choi, S.-S.; Park, W.H.; Cho, D. Characterization of surface modified flax fibers and their biocomposites with PHB. Macromol. Symp. 2003, 197, 089–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Manolache, S.; Denes, F.S.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Functionalization of sisal fibers and high-density polyethylene by cold plasma treatment. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 85, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakida, T. Surface modification of fibre and polymeric materials by discharge treatment and its application to textile processing. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 1996, 21, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.K.; Tao, X.M.; Yuen, C.W.M.; Yeung, K.W. Topographical Study of Low Temperature Plasma Treated Flax Fibers. Text. Res. J. 2000, 70, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D. Surface Modification of Natural Fibers Using Plasma Treatment. In Biodegradable Green Composites; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, E.; Panigrahi, S. Effect of Plasma Treatment on Structure, Wettability of Jute Fiber and Flexural Strength of its Composite. J. Compos. Mater. 2009, 43, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Stylios, G. Investigating the Plasma Modification of Natural Fiber Fabrics-The Effect on Fabric Surface and Mechanical Properties. Text. Res. J. 2005, 75, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Sokhansanj, S.; Hess, J.; Wright, C.; Boardman, R. A Review on Biomass Torrefaction Process and Product Properties for Energy Applications. Ind. Biotechnol. 2011, 7, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, P.; Boersma, A.; Kiel, J.; Prins, M.; Ptasinski, K.; Janssen, F. Torrefaction for Entrained Flow Gasification of Biomass. ECN-C-05-067; Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN): Petten, The Netherlands, 2005; 51p.

- Shoulaifar, T. Chemical Changes in Biomass During Torrefaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mburu, F.; Dumarçay, S.; Bocquet, J.F.; Petrissans, M.; Gérardin, P. Effect of chemical modifications caused by heat treatment on mechanical properties of Grevillea robusta wood. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Wang, H.; Lau, K.T.; Cardona, F. Chemical treatments on plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites: An overview. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fan, M.; Chen, L. Interface and bonding mechanisms of plant fibre composites: An overview. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 101, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichazo, M.N.; Albano, C.; González, J.; Perera, R.; Candal, M.V. Polypropylene/wood flour composites: Treatments and properties. Compos. Struct. 2001, 54, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Abd Rahman, N.M.M.; Yahya, R. Extrusion and injection-molding of glass fiber/MAPP/polypropylene: Effect of coupling agent on DSC, DMA, and mechanical properties. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2011, 30, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebby, B.; Fallah-Moghadam, P.; Ghotbifar, A.R.; Kazemi-Najafi, S. Influence of Maleic-Anhydride-Polypropylene (MAPP) on Wettability of Polypropylene/Wood Flour/Glass Fiber Hybrid Composites. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2011, 13, 877–884. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.; Fan, M. Wood fibres as reinforcements in natural fibre composites: Structure, properties, processing and applications. In Natural Fibre Composites; Hodzic, A., Shanks, R., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2014; pp. 3–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Xiao, S.; Shi, S.Q.; Xu, S.; Cai, L. Self-bonded natural fiber product with high hydrophobic and EMI shielding performance via magnetron sputtering Cu film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 475, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.; Kalia, S.; Pathania, D.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, N.; Schauer, C.L. Surface functionalization of lignin constituent of coconut fibers via laccase-catalyzed biografting for development of antibacterial and hydrophobic properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Fan, X.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Cavaco-Paulo, A. Hydrophobic surface functionalization of lignocellulosic jute fabrics by enzymatic grafting of octadecylamine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Yu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Q.; Fan, X. Hydrophobic modification of jute fiber used for composite reinforcement via laccase-mediated grafting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 301, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, V.; Scalici, T.; Nicoletti, F.; Vitale, G.; Prestipino, M.; Valenza, A. A new eco-friendly chemical treatment of natural fibres: Effect of sodium bicarbonate on properties of sisal fibre and its epoxy composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 85, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, D.; Sain, M. Fungal-modification of Natural Fibers: A Novel Method of Treating Natural Fibers for Composite Reinforcement. J. Polym. Environ. 2006, 14, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, A.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Shang, S. Enhancement of Hydrophobic Properties of Cellulose Fibers via Grafting with Polymeric Epoxidized Soybean Oil. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kick, T.; Grethe, T.; Mahltig, B. A Natural Based Method for Hydrophobic Treatment of Natural Fiber Material. Acta Chim. Slov. 2017, 64, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Jur, J.; Kim, D.H.; Parsons, G. Mechanisms for hydrophilic/hydrophobic wetting transitions on cellulose cotton fibers coated using Al2O3 atomic layer deposition. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2012, 30, 01A163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCorpo, J.J.; Steiger, R.P.; Franklin, J.L.; Margrave, J.L. Dissociation Energy of F2. J. Chem. Phys. 1970, 53, 936–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 86th ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brauns, F.E.; Brauns, D.A. The Chemistry of Lignin: Covering the Literature for the Years 1949–1958; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sapieha, S.; Verreault, M.; Klemberg-Sapieha, J.E.; Sacher, E.; Wertheimer, M.R. X-Ray photoelectron study of the plasma fluorination of lignocellulose. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1990, 44, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, H.T.; Manolache, S.; Young, R.A.; Denes, F. Surface fluorination of paper in CF4-RF plasma environments. Cellulose 2002, 9, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, F.; Sakamoto, E. Process for Fluorinating Cellulosic Materials and Fluorinated Cellulosic Materials. European Patent No. EP0890579A1, 10 February 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, A.J.; Lagow, R.J. The direct fluorination of hydrocarbon polymers. J. Fluor. Chem. 1974, 4, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagow, R.J.; Margrave, J.L. Direct Fluorination: A “New” Approach to Fluorine Chemistry. In Progress in Inorganic Chemistry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979; pp. 161–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lippard, S.J. Progress in Inorganic Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonov, A.P. Practical applications of the direct fluorination of polymers. J. Fluor. Chem. 2000, 103, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tressaud, A.; Durand, E.; Labrugère, C.; Kharitonov, A.P.; Kharitonova, L.N. Modification of surface properties of carbon-based and polymeric materials through fluorination routes: From fundamental research to industrial applications. J. Fluor. Chem. 2007, 128, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, A.P.; Taege, R.; Ferrier, G.; Teplyakov, V.V.; Syrtsova, D.A.; Koops, G.H. Direct fluorination—Useful tool to enhance commercial properties of polymer articles. J. Fluor. Chem. 2005, 126, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, A.P.; Kharitonova, L.N. Surface modification of polymers by direct fluorination: A convenient approach to improve commercial properties of polymeric articles. Pure Appl. Chem. 2009, 81, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaud, C. Fluorine-based plasmas: Main features and application in micro-and nanotechnology and in surface treatment. C. R. Chim. 2018, 21, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Manolach, S.O.; Denes, F.; Rowell, R.M. Cold plasma treatment on starch foam reinforced with wood fiber for its surface hydrophobicity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shul, R.; Pearton, S. Handbook of Advanced Plasma Processing Techniques; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vallan, A.; Carullo, A.; Casalicchio, M.L.; Penna, A.; Perrone, G.; Vietro, N.D.; Milella, A.; Fracassi, F. A plasma modified fiber sensor for breath rate monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Lisbon, Portugal, 11–12 June 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vourdas, N.; Tserepi, A.; Gogolides, E. Nanotextured super-hydrophobic transparent poly(methyl methacrylate) surfaces using high-density plasma processing. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 125304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparavigna, A.C. Plasma treatment advantages for textiles. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0801.3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Tang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Breedveld, V.; Hess, D.W. Creation of superhydrophobic wood surfaces by plasma etching and thin-film deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 281, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Rana, S.; Goswami, P. Developing Super-Hydrophobic and Abrasion-Resistant Wool Fabrics Using Low-Pressure Hexafluoroethane Plasma Treatment. Materials 2021, 14, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Stylios, G.K. Fabric surface properties affected by low temperature plasma treatment. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006, 173, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.; Dávalos, F.; Denes, F.; Cruz, L.E.; Young, R.A.; Ramos, J. Highly hydrophobic sisal chemithermomechanical pulp (CTMP) paper by fluorotrimethylsilane plasma treatment. Cellulose 2003, 10, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Y. An essay on the cohesion of fluids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1832, 95, 171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Schellbach, S.L.; Monteiro, S.N.; Drelich, J.W. A novel method for contact angle measurements on natural fibers. Mater. Lett. 2016, 164, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodzic, A.; Stachurski, Z.H. Droplet on a fibre: Surface tension and geometry. Compos. Interfaces 2001, 8, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hazendonk, J.M.; van der Putten, J.C.; Keurentjes, J.T.F.; Prins, A. A simple experimental method for the measurement of the surface tension of cellulosic fibres and its relation with chemical composition. Colloids Surf. A 1993, 81, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garat, W.; Pucci, M.F.; Leger, R.; Govignon, Q.; Berthet, F.; Perrin, D.; Ienny, P.; Liotier, P.-J. Surface energy determination of fibres for Liquid Composite Moulding processes: Method to estimate equilibrium contact angles from static and quasi-static data. Colloids Surf. A 2021, 611, 125787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, M.F.; Liotier, P.-J.; Drapier, S. Tensiometric method to reliably assess wetting properties of single fibers with resins: Validation on cellulosic reinforcements for composites. Colloids Surf. A 2017, 512, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téraube, O.; Agopian, J.-C.; Pucci, M.F.; Liotier, P.-J.; Hajjar-Garreau, S.; Batisse, N.; Charlet, K.; Dubois, M. Fluorination of flax fibers for improving the interfacial compatibility of eco-composites. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 33, e00467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.K.; Wendt, R.C. Estimation of the surface free energy of polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouzet, M.; Dubois, M.; Charlet, K.; Béakou, A. The effect of lignin on the reactivity of natural fibres towards molecular fluorine. Mater. Des. 2017, 120, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Giraudet, J.; Guérin, K.; Hamwi, A.; Fawal, Z.; Pirotte, P.; Masin, F. EPR and Solid-State NMR Studies of Poly(dicarbon monofluoride) (C2F)n. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 11800–11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y.; Disa, E.; Guérin, K.; Dubois, M.; Petit, E.; Hamwi, A.; Thomas, P.; Mansot, J.L. Structure control at the nanoscale in fluorinated graphitized carbon blacks through the fluorination route. J. Fluor. Chem. 2014, 168, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y.; Disa, E.; Dubois, M.; Guérin, K.; Dubois, V.; Zhang, W.; Bonnet, P.; Masin, F.; Vidal, L.; Ivanov, D.A.; et al. The synthesis of multilayer graphene materials by the fluorination of carbon nanodiscs/nanocones. Carbon 2012, 50, 3897–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dubois, M.; Guérin, K.; Hamwi, A.; Giraudet, J.; Masin, F. Solid-state NMR and EPR study of fluorinated carbon nanofibers. J. Solid State Chem. 2008, 181, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teraube, O.; Agopian, J.-C.; Petit, E.; Metz, F.; Batisse, N.; Charlet, K.; Dubois, M. Surface modification of sized vegetal fibers through direct fluorination for eco-composites. J. Fluor. Chem. 2020, 238, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agopian, J.-C.; Teraube, O.; Dubois, M.; Charlet, K. Fluorination of carbon fibre sizing without mechanical or chemical loss of the fibre. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 534, 147647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouzet, M.; Dubois, M.; Charlet, K.; Béakou, A.; Leban, J.M.; Baba, M. Fluorination renders the wood surface hydrophobic without any loss of physical and mechanical properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 133, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, N.A.; Blinov, I.A.; Alentiev, A.Y.; Belokhvostov, V.M.; Mukhortov, D.A.; Chirkov, S.V.; Mazur, A.S.; Kostina, Y.V.; Vozniuk, O.N.; Kurapova, E.S.; et al. Direct fluorination of acetyl and ethyl celluloses in perfluorinated liquid medium. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turku, I.; Rohumaa, A.; Tirri, T.; Pulkkinen, L. Progress in Achieving Fire-Retarding Cellulose-Derived Nano/Micromaterial-Based Thin Films/Coatings and Aerogels: A Review. Fire 2024, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, A.P. Direct Fluorination of Polymers; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pouzet, M. Modification de l’énergie de surface du bois par fluoration. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra, M.J.; Van Acker, J.; Tjeerdsma, B.F.; Kegel, E.V. Strength properties of thermally modified softwoods and its relation to polymeric structural wood constituents. Ann. For. Sci. 2007, 64, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téraube, O.; Agopian, J.-C.; Pucci, M.F.; Liotier, P.-J.; Conchon, P.; Badel, É.; Hajjar-Garreau, S.; Leleu, H.; Baylac, J.-B.; Batisse, N.; et al. Optimization of interfacial adhesion and mechanical performance of flax fiber-based eco-composites through fiber fluorination treatment. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 296, 112228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, A.P.; Simbirtseva, G.V.; Tressaud, A.; Durand, E.; Labrugère, C.; Dubois, M. Comparison of the surface modifications of polymers induced by direct fluorination and rf-plasma using fluorinated gases. J. Fluor. Chem. 2014, 165, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Krevelen, D.W.; te Nijenhuis, K. Properties of Polymers: Their Correlation with Chemical Structure; Their Numerical Estimation and Prediction from Additive Group Contributions; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Téraube, O.; Gratier, L.; Agopian, J.-C.; Pucci, M.F.; Liotier, P.-J.; Hajjar-Garreau, S.; Petit, E.; Batisse, N.; Bousquet, A.; Charlet, K.; et al. Elaboration of hydrophobic flax fibers through fluorine plasma treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 611, 155615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téraube, O.; Choupas, S.; El Feggouri, L.; Agopian, J.-C.; Charlet, K.; Dubois, M. Towards natural fibers resistant to mold and termites thanks to fluorine. Colloids Surf. A 2024, 702, 134926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouicem, M.M.; Tomasella, E.; Bousquet, A.; Batisse, N.; Monier, G.; Robert-Goumet, C.; Dubost, L. An investigation of adhesion mechanisms between plasma-treated PMMA support and aluminum thin films deposited by PVD. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 564, 150322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; De Vietro, N.; Beneduci, A.; Milella, A.; Chidichimo, F.; Fracassi, F.; Chidichimo, G. Low pressure plasma functionalized cellulose fiber for the remediation of petroleum hydrocarbons polluted water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulnier, F.; Dubois, M.; Charlet, K.; Frezet, L.; Beakou, A. Direct fluorination applied to wood flour used as a reinforcement for polymers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlet, K.; Saulnier, F.; Gautier, D.; Pouzet, M.; Dubois, M.; Béakou, A. Fluorination as an Effective Way to Reduce Natural Fibers Hydrophilicity. In Proceedings of the Natural Fibres: Advances in Science and Technology Towards Industrial Applications, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 27–29 April 2016; pp. 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R. Amélioration de la Stabilité Dimensionnelle des Panneaux de Fibre de Bois MDF par Traitements Physico-Chimiques; Université de Laval: Québec, QC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigall, S.M.B.; Cerveira, G.S.; Rosa, S.M.L. New polymeric-coupling agent for polypropylene/wood-flour composites. Polym. Test. 2007, 26, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, G.; Knuutinen, U.; Laitinen, K.; Spyros, A. Analysis and aging of unsaturated polyester resins in contemporary art installations by NMR spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 3203–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegard, G.M.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Physical aging of epoxy polymers and their composites. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2011, 49, 1695–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouzet, M.; Gautier, D.; Charlet, K.; Dubois, M.; Béakou, A. How to decrease the hydrophilicity of wood flour to process efficient composite materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 353, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.; Kutra, D.; Kroeger, T.; Straehle, C.N.; Kausler, B.X.; Haubold, C.; Schiegg, M.; Ales, J.; Beier, T.; Rudy, M.; et al. ilastik: Interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]