Abstract

During the vapor phase aluminizing process, protecting the joint regions of turbine blades remains a critical challenge, as the formation of the aluminide coating can significantly increase the brittleness of these areas. To address this issue, a novel double-layer anti-seepage coating was designed for the K4125 nickel-based superalloy. The coating employs a self-sealing mechanism, transforming from a porous structure into a dense NiAl/Al2O3 composite barrier at elevated temperatures, thereby suppressing aluminum penetration. Optimal anti-seepage performance is achieved at 1080 °C, reducing the transition zone width to 42 μm, which is a reduction of more than 70% compared to that of 880 °C. These results are attributed to the synergistic action of multiple mechanisms, including high-temperature densification, the formation of NiAl phase, and the growth of an oxide film on the substrate surface. Additionally, the thermal expansion mismatch enables easy mechanical removal of the coating after aluminizing without substrate damage. The coating system offers an effective and practical solution for high-temperature protection during vapor phase aluminizing in aerospace applications.

1. Introduction

Nickel (Ni)-based superalloys are widely used in high-temperature applications because of their outstanding mechanical strength and thermal stability, particularly in aero-engines [1,2,3]. The continuing drive for higher thrust-to-weight ratios and improved efficiency in the aerospace industry demands elevated combustion temperatures within the turbine [4,5], in which the serving temperature of the Ni-based turbine blades rises from 920 to 1030 °C to an ultra-high temperature range of 1400–1500 °C [6]. However, advances in materials, cooling technologies, and manufacturing processes alone cannot fully meet the demands imposed by these increasingly aggressive service conditions [7]. Aluminide coatings with excellent oxidation and corrosion resistance are commonly applied to protect superalloy substrates from high-temperature degradation [3,8], with common deposition approaches including pack cementation, slurry cementation, and vapor phase aluminizing [9,10,11]. Among these, vapor phase aluminizing is widely adopted in industrial production owing to its non-contact feature [12], which is insensitive to complex component geometries and can form uniform aluminide coatings on turbine blade surfaces, thereby avoiding the clogging issues associated with contact-based aluminizing methods [13].

Vapor phase aluminizing is generally limited to the airfoil region of turbine blades, whereas connection areas such as the dovetail root must maintain structural integrity of the alloy substrate [14]. This demand arises because these regions require high fatigue resistance and sufficient toughness to withstand cyclic service conditions, while the introduction of a brittle aluminide coating may induce mechanical property degradation and risk premature failure. Specifically, the formation of Kirkendall voids, the aggregation of blocky carbides, the coarsening and fracture of the σ-phase, and the development of a continuous γ′ film at the interface may all lead to crack initiation located at the dovetail root and significantly reduce the combined low-cycle and high-cycle fatigue life of blades [15]. Furthermore, thermal stresses from the mismatch in the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) between the coating and the substrate can further promote crack propagation and even lead to coating spallation [16]. Thus, the application of aluminide coatings is explicitly prohibited in critical connection areas, which necessitates the use of high-temperature functional protective coatings during vapor phase aluminizing to precisely block the diffusion of aluminum vapor into the alloy substrate of the protected area.

Currently, several anti-seepage strategies, such as the machining allowance method and the metallic shielding method, are employed, but often face limitations in applicability, reliability, or post-treatment operability [14,17]. In contrast, the coating masking method has emerged as a more adaptable and practical solution for selective aluminizing. The coating masking method typically employs anti-seepage slurries composed of inert ceramic powders (e.g., SiO2, Al2O3) and binders, which can be uniformly applied to components with intricate geometries, enabling precise control over the masked area. However, the traditional composition struggles to balance high-temperature anti-seepage effectiveness and post-treatment removability. Specifically, the decomposition and volatilization of binders during high-temperature aluminizing easily generate interconnected pores or microcracks [18], enabling aluminum vapor to penetrate the coating and react with the substrate. Moreover, sintering aids, as additives used to improve coating density, may cause excessive sintering and the formation of hard and strongly adherent residues [19]. Therefore, developing a novel masking material that provides both outstanding high-temperature anti-seepage capability and easy removal is essential for improving the reliability of selective aluminizing processes.

More importantly, the selected anti-seepage coatings should exhibit efficient protection performance across the entire aluminizing temperature. During the vapor phase aluminizing process, the optimized phases and microstructure of the aluminide coating strongly depend on the treatment temperature [20], which is classified into low-temperature high-activity (LTHA, 700–950 °C) aluminizing and high-temperature low-activity (HTLA, 950–1100 °C) aluminizing [21]. Under LTHA conditions, aluminum-dominated inward diffusion leads to the formation of Al-rich phases (e.g., NiAl3 and Ni2Al3) on the surface of the substrate [22,23]. These unstable phases typically require annealing at 1000–1100 °C to be transformed into β-NiAl [22]. Conversely, the coating primarily grows via the outward diffusion of nickel, directly forming a clean β-NiAl phase free of precipitates and carbides under HTLA conditions [24,25]. However, the thermal stability and adhesion performance of the anti-seepage coatings prepared by the coating masking method also vary significantly with temperature. Specifically, temperature can significantly modify the coating’s chemical composition and phase structure, and aluminizing atmosphere may further promote the emergence of additional phases [26,27]. For instance, once the temperature becomes sufficiently high, the binder decomposes thermally and releases volatile species such as CO2 and water vapor [28], creating substantial porosity that degrades coating-substrate adhesion and impedes further densification. Conversely, particle sintering facilitates the gradual closure of pores and drives microstructural reorganization [29]. Furthermore, high-temperature oxidation modifies surface chemistry and generates oxide films that differ markedly from those formed at lower temperatures, exhibiting distinct structural and chemical reactivity [30]. Collectively, these temperature-driven compositional and phase transformations govern the coating’s physical and chemical barrier performance. Therefore, it is essential to conduct comprehensive research on the structural and phase evolution of the masking coatings at different temperatures using multi-scale characterization techniques.

This study presents a novel double-layer anti-seepage coating system developed for the Ni-based superalloy K4125 during the vapor phase aluminizing, featuring high-temperature resistance, easy removability, and simplified preparation process. Through multi-scale characterization and performance evaluation, this study focuses on the microstructure evolution of the anti-seepage coating system under different temperature conditions and assesses its effectiveness in suppressing Al permeation, thereby revealing its protective mechanisms. The findings are expected to provide theoretical guidance and technical support for optimizing anti-seepage processes in superalloys, ultimately enhancing their reliability in critical fields like aerospace and other demanding industrial applications.

2. Materials and Methods

The substrate material employed in this study was the Ni-based superalloy K4125, and its chemical composition is presented in Table 1. Specimens with dimensions of 15 mm × 10 mm × 3 mm were cut from the alloy ingot using electrical discharge machining. A through-hole with a diameter of 1 mm was drilled into the surface of the specimen to facilitate subsequent suspension during the aluminizing process. The samples were ground and diamond-polished, followed by ultrasonic cleaning in alcohol and drying. The surface roughness (Ra) of the samples before aluminizing was approximately 0.15 μm, as measured using a white light interferometer (AM-7000, Atometrics, Wuhan, China).

Table 1.

The chemical composition of K4125 Ni-based superalloy (wt.%).

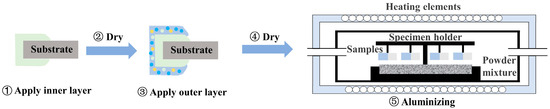

The anti-seepage coating was prepared using a dual-layer composite system consisting primarily of metal and ceramic materials. The outer layer consists of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, C2H4O) binder, Ni powder (30–40 μm), Al powder (1–10 μm), and Al2O3 powder (1–10 μm) in a mass ratio of 2:5:1:2, while the inner layer is composed of a uniform mixture of PVA binder with Al2O3 powder at a mass ratio of 1:4. The coating was fabricated by first brushing the inner layer onto the substrate, then drying it at 85 °C for 15 min. After drying, the outer layer was applied in the same manner and dried under the same conditions, with the thickness ratio of the inner layer to the outer layer controlled at 1:2. The dried specimens were then placed into the aluminizing furnace for the subsequent vapor phase aluminizing. The corresponding experimental flow chart is shown in Figure 1. To evaluate the anti-seepage performance of the coating at different temperatures, a single-sided coating design was adopted to simulate the protective condition. The pack powder for vapor phase aluminizing consisted of 33 wt.% Al powder, 65 wt.% Al2O3 powder, and 2 wt.% NH4Cl. The aluminizing process was conducted in the aluminizing furnace, where the temperature was increased at 5 °C/min to the target temperature and held for 7 h, after which the furnace was cooled to room temperature. After taking out the samples, the anti-seepage coating was mechanically removed. The samples were then ultrasonically cleaned in an alcohol solution to remove surface residues.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of anti-seepage coating preparation and aluminizing.

The phases of the surfaces of the masked area, unmasked area, and anti-seepage coating were identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/MAX 2550, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) over a 2θ range of 20° to 80° with a scanning rate of 5°/min. The surface and cross-sectional microstructures were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Quanta FEG 650, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Thermal and mass-change behaviors of the anti-aluminizing coating were characterized by DSC-TG (HITACHI STA300, Hitachi High-Tech, Tokyo, Japan) under an argon atmosphere from room temperature to 1100 °C.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Microstructure of the Anti-Seepage Coating

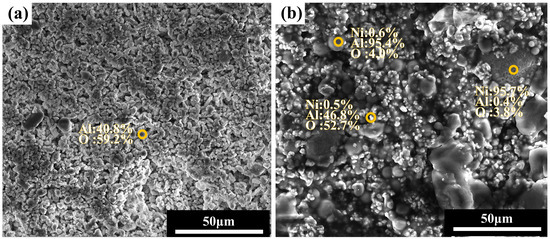

Figure 2 presents the SEM images and the corresponding EDS point analysis results (at. %) of the inner and outer layers after drying. The inner layer exhibits a uniformly distributed Al2O3 particle network, consisting of relatively fine particles that form a compact surface. In contrast, the outer layer consists of a composite structure of Al, Ni, and Al2O3 particles dispersed within the dried binder matrix, exhibiting a lower degree of surface smoothness.

Figure 2.

Initial microstructure of the anti-seepage coating: (a) inner layer; (b) outer layer.

3.2. Masking Performance of the Anti-Seepage Coating

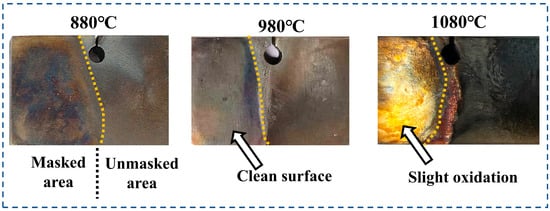

The macro-surface morphologies of the Ni-based alloy specimens after aluminizing at different temperatures are displayed in Figure 3. A distinct contrast was observed between the masked and unmasked areas after removing the coating. The masked area retained its metallic luster with no significant residue, indicating that aluminum diffusion was effectively suppressed. In contrast, the unmasked area exhibited a dark gray color, which is associated with the formation of the aluminide coating. As the aluminizing temperature increased from 880 °C to 1080 °C, a noticeable color change was observed on the alloy surface in the masked area, where a distinct light-yellow tone gradually appeared, associated with light interference caused by reflections from the inner and outer surfaces of the oxide film [31]. Previous studies have shown that higher temperatures generally promote increased oxidation, leading to the formation of thicker and more uniform oxide films [30,32]. The surface chromium content significantly increased after aluminizing, implying the potential formation of a chromium-rich oxide layer on the substrate surface, as discussed in the surface microstructure section. This layer reduces surface reactivity and acts as a barrier to interdiffusion reactions [33]. Moreover, at 1080 °C, the unmasked area exhibited a deeper and more uniform color, corresponding to a thicker aluminide layer driven by higher aluminum vapor activity and accelerated diffusion kinetics.

Figure 3.

Surface morphologies of K4125 after aluminizing at 880 °C, 980 °C, and 1080 °C.

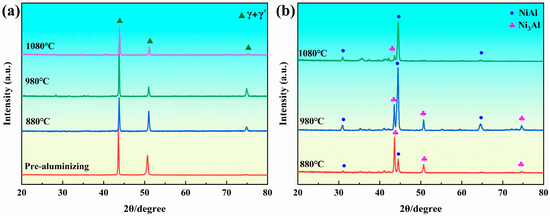

Figure 4a presents the XRD patterns of the K4125 Ni-based superalloy before and after aluminizing at 880–1080 °C. The diffraction pattern of the masked area surface remained unchanged compared to the as-received condition, showing no formation of new phases. Only characteristic diffraction peaks corresponding to the γ and γ′ phases of the substrate were detected. The γ matrix is a face-centered cubic (FCC) Ni-based austenitic phase enriched with solid-solution elements such as Co, Cr, Mo, W, and Re. The γ′ phase, with a nominal composition of Ni3(Al, Ti, Ta, Nb), is the primary strengthening phase in Ni-based superalloys and remains crystallographically coherent with the γ matrix [34]. Distinguishing between the γ and γ′ phases by XRD is challenging due to their highly similar lattice parameters in Ni-based superalloys [35]. The absence of other minor phases, such as carbides, may be attributed to their low volume fraction, which makes them difficult to detect. In contrast, the unmasked area predominantly consists of two intermetallic phases, NiAl3 and NiAl, which are characteristic constituents of aluminized coating. It is important to highlight that, as the aluminizing temperature gradually increases, the intensity of the NiAl diffraction peaks markedly increases, whereas the Ni3Al peaks become relatively weaker, indicating that enhanced Al diffusivity at higher temperatures promotes the formation of the more thermodynamically stable NiAl phase.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the Ni-based K4125 superalloy after aluminizing at different temperatures: (a) masked area; (b) unmasked area.

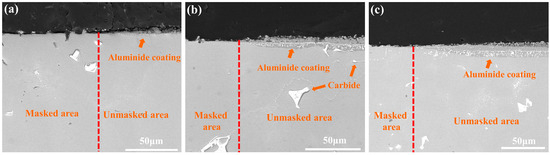

Figure 5 shows the cross-sectional microstructure of the masked and unmasked areas of the nickel-based superalloy K4125 after aluminizing at different temperatures. In the unmasked area, a relatively uniform aluminide coating structure forms at all temperatures, which consists of an outer layer and an underlying interdiffusion zone. The outer layer appears as a gray region containing Kirkendall voids, while the underlying interdiffusion zone exhibited distinct carbide precipitation [36]. Conversely, the masked area surface exhibited a sharp, distinct interface with no observable formation of an aluminide coating, which demonstrates a strong suppression of aluminum penetration during the aluminizing process.

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional morphologies for Ni-based K4125 superalloy after aluminizing at (a) 880 °C, (b) 980 °C, and (c) 1080 °C.

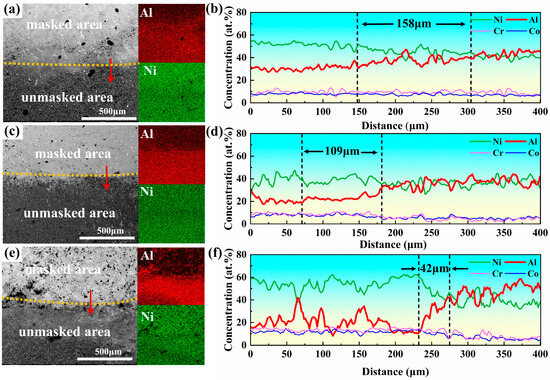

To further investigate the differences in anti-seepage performance at various temperatures, the elemental compositions at the interface between the masked and unmasked area were characterized using EDS mapping and line scanning, as shown in Figure 6. A distinct interface was observed between the masked and unmasked area at all temperatures. The masked area (substrate) appears with bright contrast under backscatter electron (BSE) mode, whereas the unmasked area appears with dark contrast because of Al enrichment. Line-scan profiles illustrate the compositional change in the main elements across the interface, which indicates the existence of a transition zone between the masked and unmasked area. It is worth noting that the abnormally high Al content (black particles) observed within the masked area is primarily attributed to residual masking material. In general, the transition zone formed at 880 °C was approximately 158 μm with a smooth change, suggesting a weak capability to block aluminum vapor. As the aluminizing temperature increased, the transition zone width decreased significantly to 109 μm at 980 °C and 42 μm at 1080 °C, respectively. The anti-seepage effect was most pronounced at 1080 °C, where a sharp decrease in Al content was observed, rapidly dropping from the unmasked area to the substrate level. This variation indicates that the aluminizing temperature of 1080 °C provides the most effective masking performance, efficiently preventing the penetration of aluminum vapor into the masked area.

Figure 6.

SEM images with EDS mapping results and corresponding line-scan profiles of K4125 superalloy after aluminizing at (a,b) 880 °C, (c,d) 980 °C, and (e,f) 1080 °C.

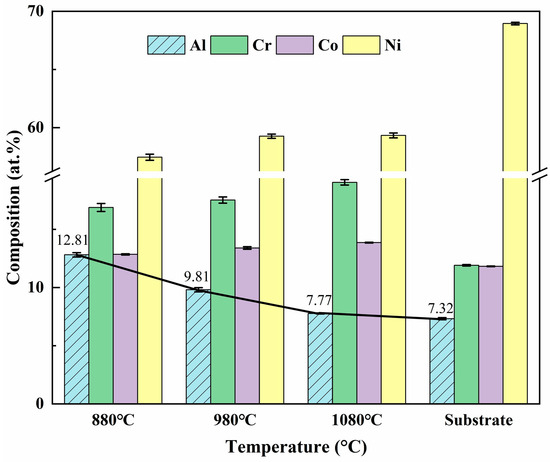

Figure 7 presents the surface elemental content of the masked area after aluminizing at different temperatures, as well as the initial content of the substrate before treatment. It is evident that the Al content in the masked area decreased markedly with increasing temperature, from 12.81 at. % to 7.77 at. %. At 1080 °C, the Al content was almost identical to that of the substrate before aluminizing. Post-aluminizing analysis revealed a consistent increase in chromium content across all masked samples. This result was possibly correlated with the formation of an extremely thin oxide film on the surface [37].

Figure 7.

Chemical composition on the surface of the masked area at different aluminizing temperatures and the substrate.

3.3. Microstructure Evolution of the Anti-Seepage Coating

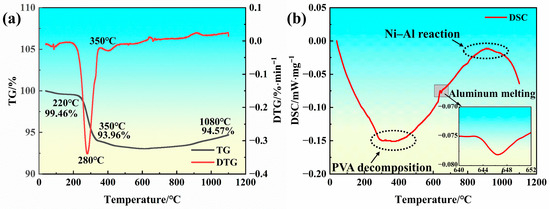

Figure 8 shows the DSC-TG curves of the anti-seepage coating over the temperature range from room temperature to 1100 °C. The TG curve indicates that the coating remains thermally stable up to approximately 220 °C, with only minor volatilization and moisture loss. A significant mass loss occurs between 220 °C and 350 °C, primarily due to thermal decomposition of the polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) binder. The Differential Thermogravimetric (DTG) curve shows the peak PVA decomposition rate of PVA at 280 °C, which is similar to the results reported by Zheng and Li [38]. A broad endothermic peak appears in the Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) curve, indicating dehydration, chain scission, and partial carbonization of PVA during heating [18,39]. Above 350 °C, the mass change stabilizes, indicating the nearly complete decomposition of PVA and the transition of the coating structure to a stable inorganic skeleton. As the temperature further increased to approximately 640 °C, an endothermic peak corresponding to the melting of Al powder appeared in the DSC curve. The melting of Al transitions it to a liquid state, which provides enhanced fluidity and diffusivity, thus promoting the subsequent thorough reaction between nickel and aluminum. As the temperature continued to rise to 900 °C, a distinct exothermic peak was observed in the DSC curve. This stage mainly involves the reaction of Ni from the coating with Al to form intermetallic compounds (IMCs) such as NiAl and Ni3Al. The TG curve remained stable during this period, indicating minor mass change in the system, where the reaction primarily manifests as element diffusion and phase transformation. A slight subsequent weight increase may be attributed to limited oxidation. Overall, the anti-seepage coating exhibited excellent thermal stability at high temperatures, which is crucial for the high-temperature protection required during vapor phase aluminizing.

Figure 8.

(a) TG-DTG and (b) DSC curves of the anti-seepage coating from 0 to 1100 °C.

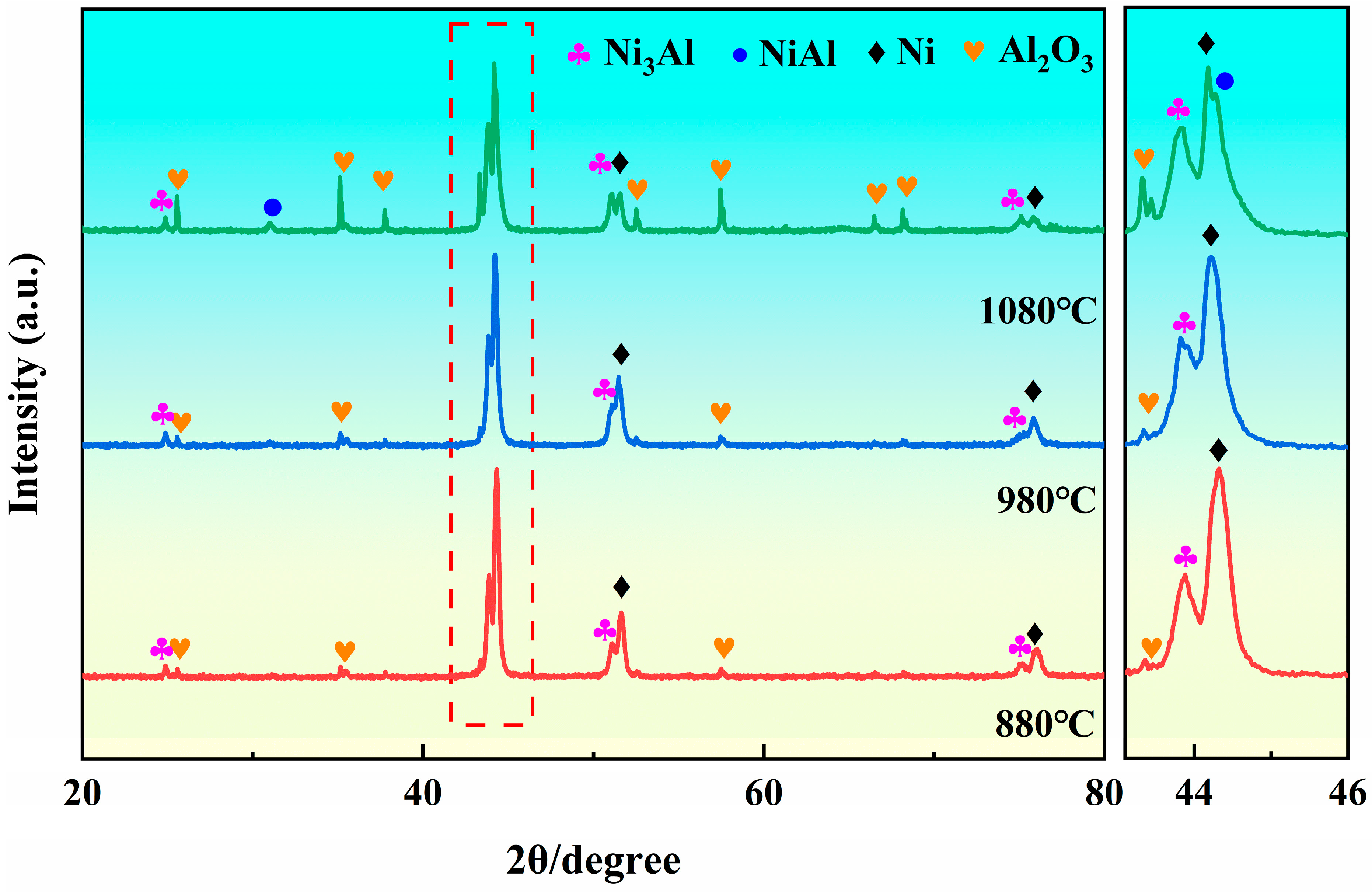

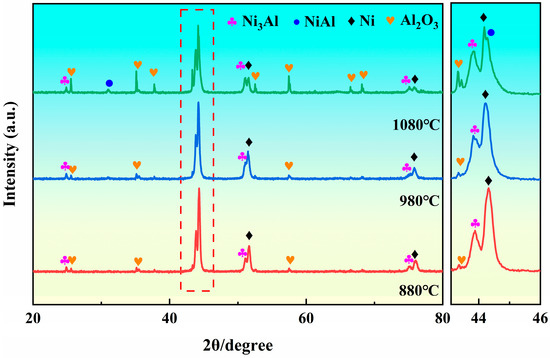

To illustrate the phase evolution of the anti-seepage coating under different aluminizing temperatures, XRD was performed on the solidified coatings, as shown in Figure 9. At aluminizing temperatures of 880 °C and 980 °C, the phase composition of the anti-seepage coating primarily consisted of the Al2O3 phase, the Ni3Al intermetallic compound, and Ni. In contrast, the NiAl phase was additionally detected in the coating alongside three phases for the anti-seepage coating after aluminizing at 1080 °C, indicating that a new reaction had occurred. This suggests that elevated temperatures promote Al-Ni reaction, leading to the formation of stable NiAl and the partial transformation of Ni3Al into NiAl, thereby enhancing structural densification and interfacial integrity of the coating.

Figure 9.

XRD results of the anti-seepage coating after aluminizing at different temperatures.

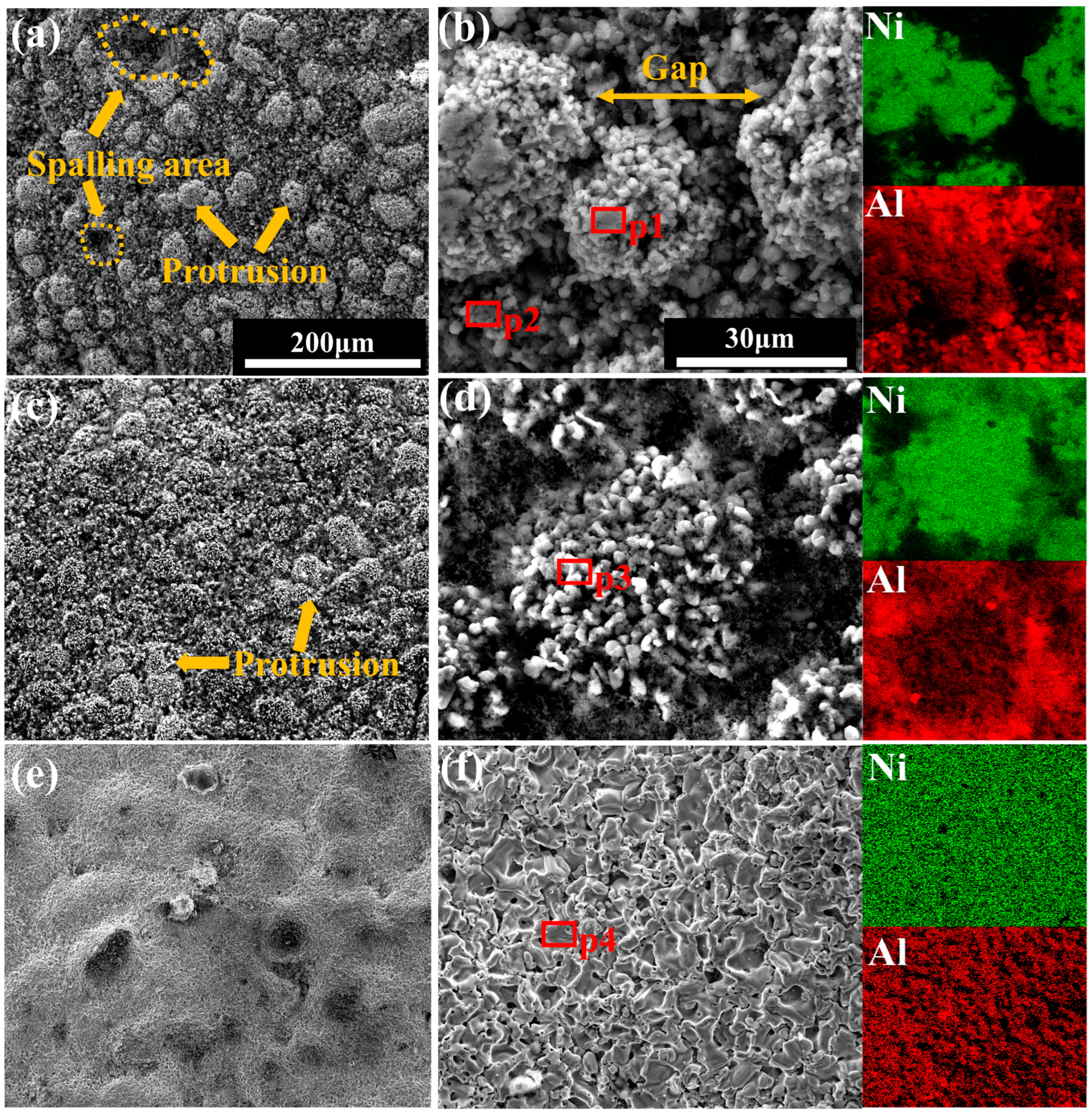

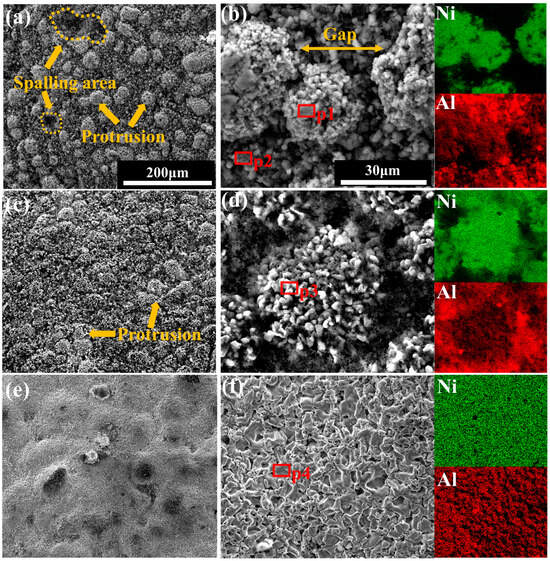

The surface morphology of the anti-seepage coating obtained by SEM is presented in Figure 10. After aluminizing at 880 °C, the coating surface exhibited an irregular morphology, characterized by prominent protrusions and localized spallation. As shown in Table 2, these protrusions (p1) were primarily composed of unreacted Ni powder and Ni-Al IMCs. The magnified images clearly revealed distinct gaps between adjacent protrusions, which were only weakly bridged by the underlying Al2O3 particles (p2). Moreover, localized spallation occurred due to the weak bonding of these protrusions and the coating surface, indicating that the coating remained relatively rough and insufficiently densified at this temperature. The relatively low aluminizing temperature limited the reaction between the Ni particles in the coating and the active Al atoms and molten aluminum, thereby suppressing the formation of sufficient Ni-Al IMCs. In addition, the restricted degree of sintering hindered the closure of pores generated by PVA pyrolysis, ultimately increasing the penetration behavior of Al atoms into the substrate. After aluminizing at 980 °C (Figure 10b,e), no particle spallation but localized protrusions were observed on the coating surface, which exhibited a composition similar to the 880 °C sample, suggesting that full densification has not yet been achieved. When the temperature was increased to 1080 °C, the anti-seepage coating experienced significant sintering and densification, which was predominantly composed of uniformly continuous distributed Ni-Al IMCs. The surface aluminum content increased markedly (p4), and combined with the XRD results, this indicates that a larger amount of NiAl phase was formed. EDS mapping also confirmed the highly homogeneous distribution of Ni and Al on the surface.

Figure 10.

SEM surface morphologies and corresponding enlarged images with EDS results of the anti-seepage coating at (a,b) 880 °C, (c,d) 980 °C, and (e,f) 1080 °C.

Table 2.

EDS point analysis results (at. %) for the sample shown in Figure 10.

4. Discussion

4.1. Protection Mechanism of the Composite Coating

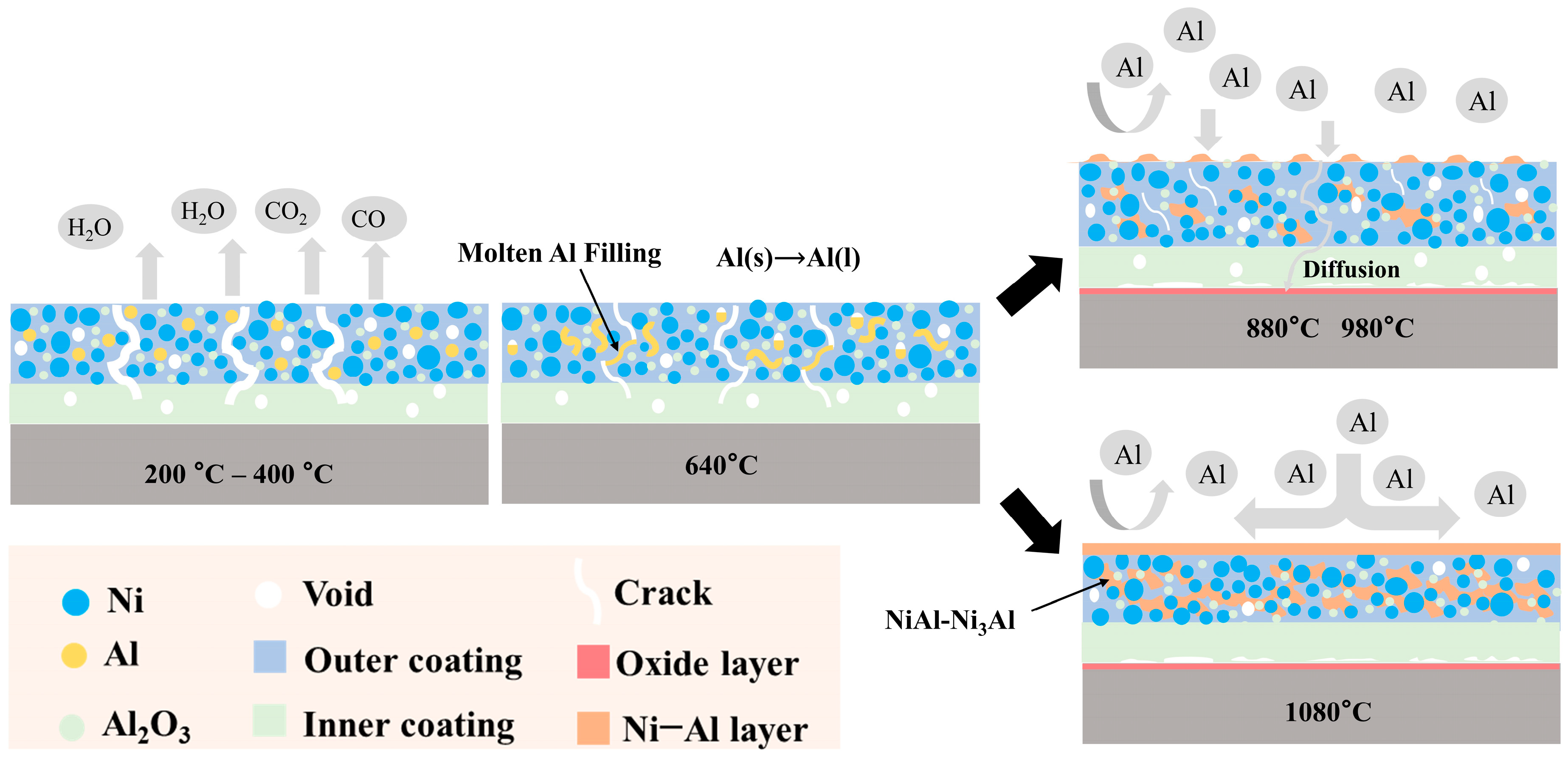

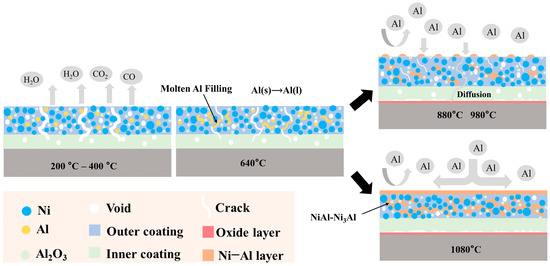

The double-layer anti-seepage coating designed in this study exhibits distinct microstructure evolution, where each layer plays a unique and complementary role in preventing aluminum penetration during the vapor phase aluminizing process. The inner layer serves as a chemically inert and thermally stable physical barrier, effectively isolating the substrate from the reactive outer coating. The outer composite layer is in direct contact with the external reaction environment and provides the primary anti-seepage performance. The anti-seepage behavior originates from the synergy of two fundamental mechanisms: (i) physical barrier formed via sintering densification [40]; and (ii) diffusion inhibition via the formation of NiAl [41].

As shown in Figure 11, during the initial heating stage (<400 °C), TG-DSC (Figure 8) analysis confirms that PVA undergoes complete decomposition, forming a porous framework composed of Al2O3, metallic Ni, and Al powders. This process mainly involves the following reactions [42]:

Figure 11.

Schematic illustration of the anti-seepage mechanism of the coating.

Previous studies have shown that PVA exhibits favorable physicochemical properties and serves effectively as a water-based binder, thereby avoiding the use of toxic organic solvents during coating and drying [28]. Moreover, the residual pores generated from PVA decomposition act as critical sites for triggering stress-relaxation mechanisms [43]. Through these pores, the coating is able to alleviate internal stresses caused by the thermal expansion mismatch between the substrate and the ceramic components, thereby mitigating the risk of spallation or crack formation [44]. Oh and Kim et al. [45] reported that incorporating PVA significantly enhances the coating toughness and critical cracking thickness (CCT). The CCT of PVA-containing coatings was approximately 77.8% higher than that of coatings prepared with carboxymethyl cellulose, effectively suppressing crack initiation.

As the temperature increases, the Al powder begins to melt. The resulting liquid Al flows into and fills the pores created during PVA decomposition, breaking the interconnected pore network into isolated and closed pores:

In this process, Al transitions from a static filler to a dynamic sealing phase, markedly increasing coating density while also serving as a reservoir for subsequent Al-Ni reactions. At the aluminizing temperature, both external active Al atoms and internal liquid Al react with Ni particles in the coating to form IMCs such as Ni3Al and NiAl. High temperature further promotes the transformation of Ni3Al into the more thermodynamically stable NiAl phase. The possible phase transformations of the coating during the vapor phase aluminizing are as follows:

These newly formed phases create sealing structures that decrease open pores and enhance the coating density. These newly formed phases exhibit low vacancy concentrations, which effectively suppress the aluminum vapor diffusion [46,47]. Furthermore, the Al2O3 phase, uniformly dispersed throughout the double-layer coating, functions as a highly inert diffusion barrier and effectively lowers the overall diffusion coefficient.

In addition to providing an effective barrier against aluminum penetration during aluminizing, the designed composite coating also offers a practical advantage in the subsequent removal process. The significant difference in the CTE between the aluminum oxide ceramic layer and the Ni-based metallic substrate naturally facilitates the formation of porosity at the interface [48,49]. Studies have shown that CTE mismatch causes energy storage in the ceramic layer upon cooling, which is a primary driving force for spallation [50,51]. This characteristic ensures that the entire coating can be readily removed mechanically after aluminizing, without damaging the substrate or leaving behind contaminants. The fact that the protected area’s surface maintained a metallic luster and smooth topography suggests that coating stripping occurred within the coating itself rather than at the coating/substrate interface.

4.2. Effect of Aluminizing Temperature on Anti-Seepage Performance

Temperature is the key parameter in the vapor phase aluminizing process, which governs the sintering behavior, phase evolution, and the anti-seepage effectiveness of the double-layer coating. Comparative experiments at 880 °C, 980 °C, and 1080 °C on K4125 alloy show pronounced temperature-dependent changes in microstructure and anti-seepage performance. As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, the coating exhibits markedly superior anti-seepage performance at 1080 °C compared to 980 °C and 880 °C. Moreover, the thickness of the transition zone decreases sharply from 158 μm at 880 °C to only 42 μm at 1080 °C. The Al content in the protected region remains nearly unchanged, confirming the effectiveness of the barrier in suppressing Al penetration.

At the aluminizing temperatures of 880 °C and 980 °C, the coating did not achieve complete densification, which is a core reason for its insufficient anti-seepage capability. As illustrated in Figure 11, although both the inner and outer layers began to sinter, numerous pores and microcracks were also retained. Local Ni particles also spalled from the surface, indicating that the surface barrier layer was not tightly bonded. XRD results reveal that the coating is dominated by Ni3Al with no β-NiAl, indicating that Al-Ni reactions remain at an early stage. From a kinetic perspective, the processes within this temperature regime are marked by limited solid-state neck growth and insufficient atomic mobility [52], which prevents the formation of a dense, protective layer, thereby leaving residual pore pathways that allow the penetration of aluminum vapor. In contrast, the coating structure and phase evolution underwent a fundamental transformation at 1080 °C. The high temperature significantly promoted the sintering action between the powder particles, effectively eliminating porosity and accelerating the densification of the coating. Under this condition, both vapor phase Al and locally formed liquid Al reacted with Ni, producing denser and more stable β-NiAl [20,53]. Additionally, a thin oxide film formed on the substrate surface due to the minor oxidation of Cr, providing a supplementary chemical barrier [33].

Overall, the high-temperature-induced dense microstructure, the formation of β-NiAl, and the development of the oxide film collectively established a sealing barrier system, which accounts for the superior anti-aluminizing performance. Compared with anti-seepage coating by other methods, the anti-seepage system proposed in this study provides effective protection for Ni-based superalloy K4125 during vapor phase aluminizing [14,17]. The system employed a design concept based on functional compartmentalization and self-sealing, enabling the coating to adapt to the unavoidable temperature selection requirements of the vapor phase aluminizing.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully developed and fabricated a novel double-layer anti-seepage coating system designed to provide localized protection for the connection areas of Ni-based superalloy K4125 during the vapor phase aluminizing process. Through multi-scale characterization and performance evaluation, we investigated the microstructure evolution of the coating system under different aluminizing temperatures and elucidated its protective mechanisms against Al permeation. The following conclusions can be drawn:

- The anti-seepage coating provides effective protection through dual mechanisms that combine physical sealing induced by high-temperature densification with diffusion inhibition from the formation of the NiAl/Al2O3 composite structure.

- The anti-seepage capability is highly dependent on temperature. The coating exhibited superior protection at 1080 °C, where the thickness of the transition zone is reduced to 42 μm, compared with 158 μm at 880 °C. Elevated temperature significantly enhances particle sintering and accelerates the formation of a denser and more continuous NiAl phase, thereby establishing a more efficient and stable protective system.

- The coating also offers a practical advantage in post-aluminizing removal. The inherent mismatch of the coefficient of thermal expansion between the coating and the substrate enables the solidified coating to be mechanically removed without damaging the substrate.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.Z., C.X. and Y.L. (Yidi Li); investigation, X.Z., C.X. and Y.L. (Yidi Li); writing—original draft, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. (Yidi Li) and Y.L. (Yunping Li); supervision, Y.L. (Yunping Li); funding acquisition, Y.L. (Yunping Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This investigation is supported by the grant from the Hunan Province’s ‘Leading the Charge with Open Competition’ Project.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Cheng Xie was employed by the company AECC South Industry Company Limited, Zhuzhou, China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abkenar, A.K.; Malekan, A.; Bozorg, M.; Nematipour, K. Hot corrosion and oxidation behavior of Pt–aluminide and Pt–Rh–aluminide coatings applied on nickle-base and cobalt-base substrates. Met. Mater.-Int. 2024, 30, 2466–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjesteh, M.M.; Zangeneh-Madar, K.; Abbasi, S.M.; Shirvani, K. The effect of platinum-aluminide coating features on high-temperature fatigue life of nickel-based superalloy rene®80. J. Min. Metall. Sect. B-Metall. 2019, 55, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, B.; Rastegari, S.; Eyvazjamadi, H. Formation mechanism of Pt-modified aluminide coating structure by out-of-the-pack aluminizing. Surf. Eng. 2021, 37, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; He, W.; Chen, W.; Xue, Z.; He, J.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Progress on high-temperature protective coatings for aero-engines. Surf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateusz, K.; Dominik, K.; Xin, Y.; Wojciech, R.; Kowalewski, Z.L.; Cezary, S. Aluminide thermal barrier coating for high temperature performance of MAR 247 nickel based superalloy. Coatings 2021, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pytel, M.; Tokarski, T.; Goral; Fillip, R. Structure of Pd-Zr and Pt-Zr modified aluminide coatings deposited by a CVD method on nickel superalloys. Kov. Mater.-Met. Mater. 2019, 57, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, A.; Shirvani, K. Internal surface protection of gas turbine blade by Si-aluminide coating. Mater. Corros. 2011, 62, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Dai, J.; Niu, J.; He, L.; Mu, R.; Wang, Z. Isothermal oxidation and hot corrosion behaviors of diffusion aluminide coatings deposited by chemical vapor deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 637, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, H.; Nogorani, F.S.; Safari, M. Microstructure analysis of the pack cementation aluminide coatings modified by CeO2 addition. Met. Mater.-Int. 2021, 27, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopec, M. Recent advances in the deposition of aluminide coatings on nickel-based superalloys: A synthetic review. Coatings 2024, 14, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Sayre, G. Factors affecting the microstructure of platinum-modified aluminide coatings during a vapor phase aluminizing process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 203, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Nakagawa, K.; Tuda, Y.; Taniguchi, S. Growth behavior of coatings formed by vapor phase aluminizing using Fe-Al pellets of varying composition. Mater. Trans. 2006, 47, 2341–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, M.; Eslami, A.; Bahrami, A. High temperature oxidation behavior of aluminide coatings applied on HP-MA heat resistant steel using a gas-phase aluminizing process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 434, 128181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zou, J.; Ning, X.; Wei, H.; Zhan, W.; Li, F. Effect of the anti-seepage masking layer on the microstructure evolution of Ni-based superalloy during co-deposition of the Al-Si coating. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zheng, S.; Tao, M.; Fei, C.; Hu, Y.; Huang, B.; Yuan, L. Service damage mechanism and interface cracking behavior of Ni-based superalloy turbine blades with aluminized coating. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 153, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texier, D.; Monceau, D.; Hervier, Z.; Andrieu, E. Effect of interdiffusion on mechanical and thermal expansion properties at high temperature of a MCrAlY coated Ni-based superalloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zou, J.; Shi, Q.; Li, X.; Wei, H. The evolution mechanism of ethylene-based and glass-ceramic as composited anti-seepage masking layer for Ni-based superalloy during aluminizing. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 705, 135732. [Google Scholar]

- Kovtun, G.; Cuberes, T. Impact of glycerol and heating rate on the thermal decomposition of PVA films. Polymers 2025, 17, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.; Han, L.; Xiong, G.; Guo, Z.H.; Huang, J.W.; Zhang, Y.J.; Shen, Z.; Ge, C.C. Impact of sintering aid type and content on the mechanical properties of digital light processing 3D-printed Si3N4 ceramics. Materials 2024, 17, 5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Niu, J.; He, L.; Mu, R.; Wang, K. Effects of deposition temperature on the kinetics growth and protective properties of aluminide coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 632, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arda, I.A.; Gökhan, G.; Kaan, D.; Havva, K.Z.; Metin, U. The Effects of Chemical Vapor Aluminizing Process Time and Post-processing for Nickel Aluminide Coating on CMSX-4 Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 31, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goward, G.; Boone, D. Mechanisms of formation of diffusion aluminide coatings on nickel-base superalloys. Oxid. Met. 1971, 3, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossard, J.M.; Panicaud, B.; Balmain, J.; Bonnet, G. Modelling of aluminized coating growth on nickel. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 6586–6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R. Gas turbine coatings–An overview. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2012, 26, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angenete, J.; Stiller, K. Comparison of inward and outward grown Pt modified aluminide diffusion coatings on a Ni based single crystal superalloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 150, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.D.; Wang, Y.Q.; Sun, Q.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. Structure controlling strategy towards the high-temperature oxidation in multilayered coatings: An experience from Cr/CrAlN system. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2025, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, H.; Arabi, H.; Rastegari, S. Effects of temperature and Al-concentration on formation mechanism of an aluminide coating applied on superalloy IN738LC through a single step low activity gas diffusion process. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 505, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas, T.; Dimitrios, F.; Xanthi, N.; Ioannis, T.; Costas, P. Thermal Behavior of Poly(vinyl alcohol) in the Form of Physically Crosslinked Film. Polymers 2023, 15, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendaoudi, S.-E.; Bounazef, M.; Djeffal, A. The effect of sintering temperature on the porosity and compressive strength of corundum. J. Mech. Behav. Mater. 2018, 27, 0018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Gong, P.; Hu, Z.; Li, B. Effect of Cr content on the high temperature oxidation behavior of FeCoNiMnCrx porous high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 3324–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Huang, T.; Lu, Y.; Hong, M. Tunable coloring via post-thermal annealing of laser-processed metal surface. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.; Cao, X.; Jiang, H.; Yan, D.; Rong, L. Effect of oxidation temperature on microstructure and liquid lead-bismuth eutectic corrosion resistance of pre-oxidized film on high-silicon ferritic/martensitic steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2025, 615, 155931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, R.; Saric, I.; Piltaver, I.K.; Badovinac, I.J.; Petravic, M. Oxide formation on chromium metal surfaces by low-energy oxygen implantation at room temperature. Thin Solid Films 2017, 636, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, T.M.; Tin, S. Nickel-based superalloys for advanced turbine engines: Chemistry, microstructure and properties. J. Propul. Power 2006, 22, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumi, O.; Hirosi, H.; Toshihiro, Y.; Michio, Y.; Kazumasa, O. X-ray diffractometric determination of lattice misfit between γ and γ’ phases in Ni-base superalloys. Adv. X-Ray Anal. 1988, 32, 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Jerzy, M.; Maryana, Z.-Y.; Maciej, Z.; Jolanta, R. SEM/TEM Investigation of aluminide coating Co-doped with Pt and Hf deposited on Inconel 625. Materials 2018, 11, 898. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Ding, Q.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Bei, H. The effects of alloying elements Cr, Al, and Si on oxidation behaviors of Ni-based superalloys. Materials 2022, 15, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Li, L.; Jin, S.; Fan, P.; Zhong, M. Effect of tiny amount of DMC on thermal, mechanical, optical, and water resistance properties of poly(vinyl alcohol). J. Polym. Eng. 2022, 42, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkevich, S.I.; Druzhinina, T.V.; Kharchenko, I.M.; Kryazhev, Y.G. Thermal transformations of polyvinyl alcohol as a source for the preparation of carbon materials. Solid Fuel Chem. 2007, 41, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-S.; Song, J.-B.; Dong, H.; Yao, J.-T. Sintering-induced failure mechanism of thermal barrier coatings and sintering-resistant design. Coatings 2022, 12, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Feng, L.J.; Chen, C.; Yan, M.; Wen, Z.C.; Chun, H.X.; Wang, B.Y.; Bin, Z.H. Improved oxidation resistance of Cr-Si coated Zircaloy with an in-situ formed Zr2Si diffusion barrier. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.; Kong, L.X. A thermal degradation mechanism of polyvinyl alcohol/silica nanocomposites. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2007, 92, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugwagwa, L.; Yadroitsev, I.; Matope, S. Effect of process parameters on residual stresses, distortions, and porosity in selective laser melting of maraging steel 300. Metals 2019, 9, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andritschky, M.; Alpuim, P.; Stöver, D.; Funke, C. Study of the mechanics of the delamination of ceramic functional coatings. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1999, 271, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyudeok, O.; Sunhyung, K.; Zhenghui, S.; Hwan, J.M.; Martti, T.; Lae, L.H. Effect of carboxymethyl cellulose and polyvinyl alcohol on the cracking of particulate coating layers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 170, 106951. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, H.-B.; Peng, H.; Peng, L.-Q.; Gong, S.-K. Diffusion barrier behaviors of (Ru,Ni)Al/NiAl coatings on Ni-based superalloy substrate. Intermetallics 2010, 19, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Fukaya, H.; Murata, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Inui, H. Diffusion of Al and Al-substituting elements in Ni3Al at elevated temperatures. Mater. Trans. 2012, 53, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Meng, X.; Shi, K.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Lian, W.; Zhou, C.; Lyu, Y.; Chu, P.K. Hydrogen permeation barriers and preparation techniques: A review. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 060803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Neuschütz, D. Efficiency of α-alumina as diffusion barrier between bond coat and bulk material of gas turbine blades. Vacuum 2003, 71, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Atkinson, A.; Chirivì, L.; Nicholls, J.R. Evolution of stress and morphology in thermal barrier coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 204, 3851–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizarova, Y.A.; Zakharov, A.I. High-Temperature Functional Protective Coatings. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2021, 61, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, S.; He, P.; Duan, X.; Jia, D.; Zhou, Y. Kinetics and properties of porous alumina with a dense surface layer prepared via bimodal powder sintering. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 8446–8453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosh, S.; Pandian, R.V.; Srivatsan, S. An overview on synthesis, processing and applications of nickel aluminides: From fundamentals to current prospects. Crystals 2023, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.