Abstract

This study examines the conceptualization of sustainability in heritage tourism in Saudi Arabia following the introduction of the Saudi Vision 2030 program and the country’s opening to tourism in 2019, both of which aim to diversify the economy and promote cultural heritage. A scoping review methodology based on the Arksey & O’Malley framework has been adopted; data were charted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) charting method based on the PRISMA-ScR reporting protocol. Publications from 2019 to 2025 were systematically collected from the database and manual research, resulting in 25 fully accessible studies that met the inclusion criteria. Data were analyzed thematically, revealing six main areas of investigation, encompassing both sustainability outcomes and cross-cutting implementation enablers: heritage conservation and tourism development, architecture and urban planning, policy and governance, community engagement, marketing and technology, and geoheritage and environmental sustainability. The findings indicate that Saudi research in this field is primarily qualitative, focusing on ecological aspects. The studies reveal limited integration of social and technological dimensions, with significant gaps identified in standardized sustainability indicators, longitudinal monitoring, policy implementation, and digital heritage tools. The originality of this study lies in its comprehensive mapping of Saudi heritage tourism sustainability research, highlighting emerging gaps and future agendas. The results also provide a roadmap for policymakers, managers, and scholars to enhance governance policies, community participation, and technological integration, which can contribute to sustainable tourism development in line with Saudi Vision 2030 goals, thereby fostering international competitiveness while preserving cultural and natural heritage.

1. Introduction

Sustainability has played a crucial role in tourism, primarily due to its rapid growth and subsequent significant impact on the environment, economies, and society [1,2], in accordance with the 2030 Agenda [3,4] incorporating low-impact practices mainly explored in the hotel sector [5], climate change [6], governance [7], social responsibility and community engagement [8], and impacts in destination management [9].

Most studies on sustainability have primarily focused on the European continent, which, for a long time, has been affected by conservation issues [10] and overtourism, both of which characterize heritage tourism. However, emerging destinations have long been excluded from this debate, despite demonstrating a significantly different approach [11] to the practices widely adopted and presented in the existing literature. Therefore, this research aims to highlight aspects of sustainability conceptualization in heritage tourism that remain overlooked in the literature, particularly in emerging destinations. In particular, in emerging travel destinations, sustainability has been crucial in promoting authentic and responsible tourism experiences, playing a vital role in balancing heritage conservation and tourism development [12,13]. Heritage is approached not only as a set of tourism assets but as a socio-cultural phenomenon involving processes of identification, valuation, interpretation, and governance. In heritage studies, heritage is understood as “made” through institutional practices and community meanings. It is particularly relevant in rapidly transforming destinations, where heritage is simultaneously mobilized for place identity, cultural continuity, and development, and where tourism acts as a mediator that can both support conservation (through resources and visibility) and generate pressures (commodification, authenticity risks, and uneven benefit distribution). In particular, Saudi Arabia is investing in non-oil economies, such as tourism [14], through the Saudi Vision 2030 program [15,16], which is embedded within the national policy framework under which the transformation of the tourism and heritage sectors is taking place. It is worth noting that Vision 2030 is not used as a lens through which the coding of the reviewed literature is taking place. Instead, it constitutes a contextual constraint and a norm under which the implications of the findings are to be understood. Vision 2030 is implemented through a range of Vision Realization Programs, including culture and tourism programs. The most immediate is the Quality of Life Program, which also wholeheartedly supports culture, tourism, and related place–experience industries, along with programs that improve customer service and infrastructure, for instance, the Pilgrim Experience Program. At the same time, the Ministry of Culture’s cultural strategy and governance have been implemented through dedicated institutions, primarily the Heritage Commission, which has a mandate to develop and implement the heritage sector, formulate policies, and implement heritage strategies within the overall national cultural context. Therefore, this review will use Vision 2030 as the policy context that determines the development of heritage tourism, as well as the sustainability instruments the literature seeks to develop and test. However, there is a lack of research on conceptualizing sustainability in tourism [17,18] and in this research, sustainability is treated as both

- A normative development goal for heritage tourism consistent with Saudi Vision 2030.

- An assessment of an analytical framework intended to identify evidence.

The study defines sustainability through the triple bottom line framework, focusing on the environmental, socio-cultural, and economic dimensions of heritage destinations. The proposed framework avoids conceptual duplication by distinguishing between the outcomes of sustainability efforts and the mechanisms used to achieve them.

Therefore, the literature is categorized through the use of two complementary lenses:

- Outcomes in terms of sustainability (affected or influenced in what way): environmental, socio-cultural, and economic.

- Implementation enablers (outcome achievement): governance and policy, participation and engagement, and use of socio-technical instruments such as digital platforms, Building Information Modeling (BIM), Geographic Information Systems (GIS), DT, and IoTs.

This approach is adopted uniformly, treating governance, community, and technology as cross-cutting enablers rather than additional sustainability pillars.

Finally, this paper aims to map and analyze how sustainability has been conceptualized and operationalized in the literature on the tourism industry’s heritage sector in Saudi Arabia. The use of bibliometric profiling as an evidence-mapping technique, discussed below, is intended for this study, which seeks to create a framework for understanding the emerging body of knowledge and pinpointing areas of concentration and underdevelopment within it. According to the scoping review approach, the types of gaps to address in this synthesis include under-specified or irregular reporting of instruments in a dataset such as this.

This research therefore aims to contribute to the international debate on sustainability by, on the one hand, analyzing the existing literature in these contexts, with particular attention to the gaps identified in light of potential research directions in emerging countries, and, on the other hand, shedding light on possible topics of interest investigated in these emerging contexts that may help to fill existing gaps in different areas of the world. Therefore, the research argues that these new contexts may offer insights and innovative solutions for sustainable heritage management.

Research Questions

Based on the fast growth of tourist development in Saudi Arabia under the auspices of the ‘Vision 2030’ initiative, as well as the simultaneous need to maintain the authenticity of cultural heritage resources, this scoping review examines the following four research questions:

- (RQ1) What are the key publication characteristics and trends identified in the literature about sustainability and heritage tourism, focusing on the Saudi context from 2019 forward (for instance, time trends, publication outlets, and themes)?

- (RQ2) What is the conceptualization of sustainability as it is reported in the identified studies, in the context of heritage tourism in Saudi Arabia?

- (RQ3) What mechanisms are cited as being effective (or ineffective) as implementation enablers for sustainability outcomes, including policies, governance, and community engagement?

- (RQ4) Which sustainability-related instruments or methods (e.g., standards/metrics, monitoring systems, benchmarking approaches, or technology-based tools) are not adequately covered in the included studies?

To ensure methodological consistency with a scoping review, the first overall goal of the present study is to map and review the evidence on sustainability in heritage tourism, focusing on the Saudi-based literature, and then to examine the level of detail reported in the operationalization of the topic. Within this overall framework, RQ1 provides contextual information on the nature of the evidence. At the same time, RQ2–RQ4 focus on the evidentiary mapping of the information presented in the studies comprising the reviewed corpus of evidence on the themes.

The research is presented in this paper as follows: the second paragraph outlines the methodology adopted, while the third presents the results. The fourth paragraph analyzes existing arguments, whereas the fifth highlights emerging gaps. In the sixth paragraph, future research directions are outlined, while the seventh section summarizes the conclusions and recommendations.

2. Methodology

The adopted methodology is based on a scoping review, a method for mapping the existing literature to highlight gaps [19]. The system is divided into five distinct phases: (1) formulating the research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting eligible studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. In particular, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) method [20] is employed to chart the sources, and the PRISMA-ScR checklist [21] is used to present the literature review. Although the chosen literature review methodology is suitable for the research objectives, to date, no scoping review protocol on sustainable heritage tourism has been registered on PROSPERO, as scoping reviews are mainly used in the medical field. Therefore, a new protocol has been developed. A summary of the main steps and operational criteria of the developed protocol is presented to enhance transparency and replicability (Table A1).

After defining the research question, the research on the sources commenced. It was conducted from September to October 2025, and the query was formulated as follows (in order):

Tourism AND Heritage AND Saudi Arabia

Then, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined accordingly:

- a.

- Inclusion criteria:

- -

- Empirical, bibliometric, or systematic studies.

- -

- Paper, conference paper, commentary.

- -

- English language.

- -

- Published between 2019 and 2025.

- -

- Database: Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, Google.

- b.

- Exclusion criteria:

- -

- Papers not explicitly dealing with Saudi Arabia.

- -

- Conference abstracts, editorial notes, and duplicates.

Search Strategy and Scope

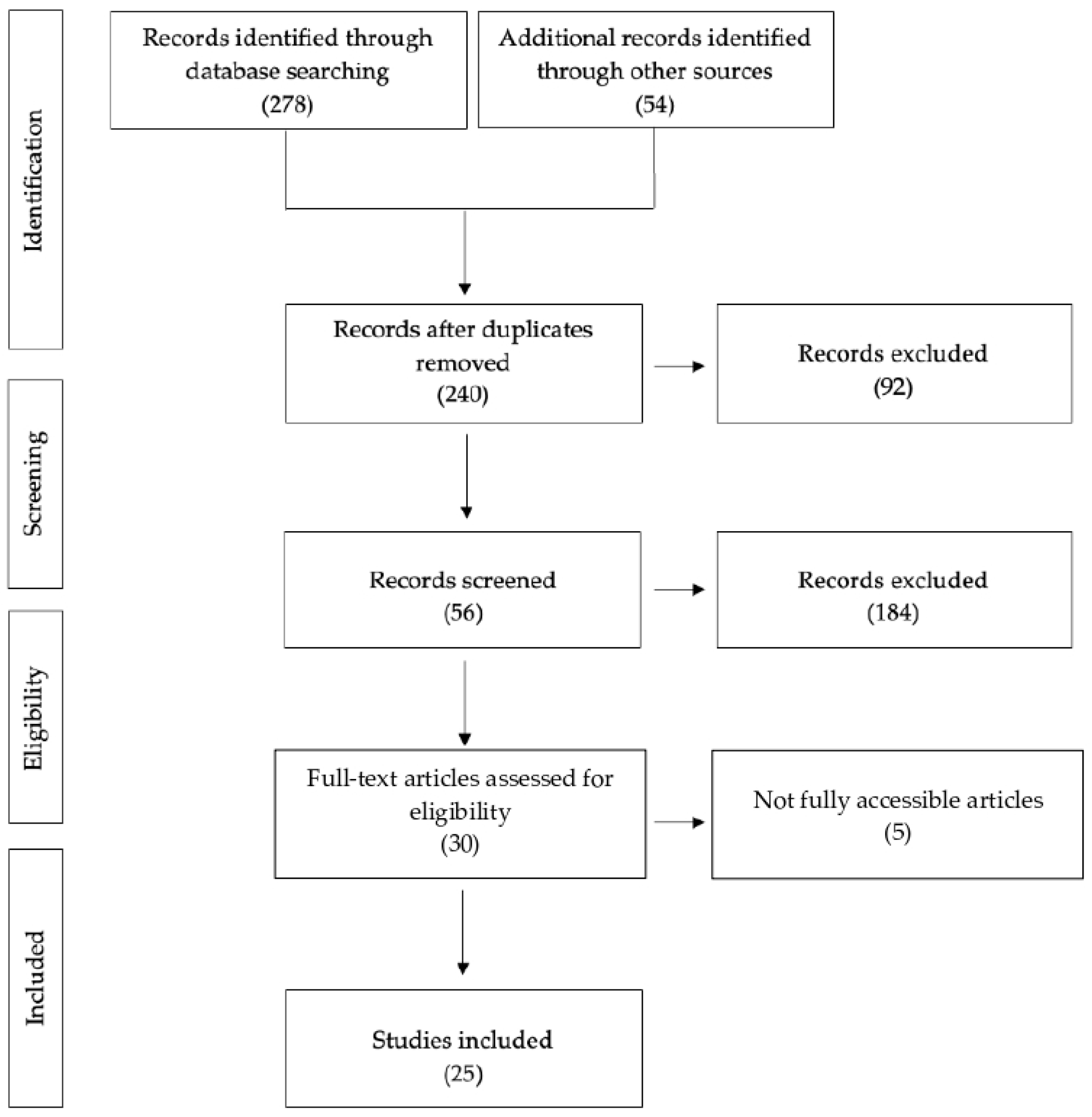

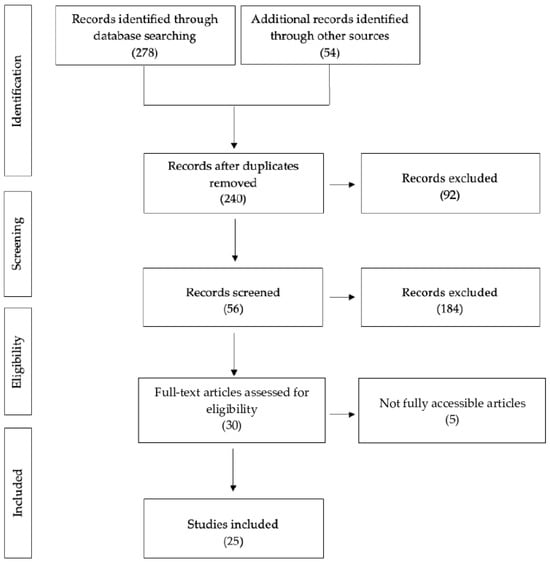

The search and selection of sources were divided into three phases. The first phase involved selecting sources identified through two databases (Scopus and Web of Science). This initial search was then supplemented by a second manual search across the main sites (ResearchGate, Google Scholar, and Google). These international databases collect global academic output, enabling a broad, representative dataset for the study. After this first phase, the duplicates were removed. The second phase involved screening, during which sources were selected by analyzing titles and abstracts to identify the most pertinent. The third phase was eligibility: all the texts assigned in the second phase were read in full, and the most relevant were selected. The different steps have been summarized in the PRISMA Statement [22]. A total of 332 records were initially identified through database research (Scopus and Web of Science) and manual searches (ResearchGate, Google Scholar, Google). After removing 92 duplicates, 240 records were screened by title and abstract, resulting in 56 full-text articles being assessed for eligibility. Then, 30 studies met all inclusion criteria, and 25 were included in the scoping as fully accessible (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma protocol (source: authors).

The review process followed a framework outlined in the Arksey & O’Malley methodological framework [19], as guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute, while the reporting followed a PRISMA-ScR framework. The final corpus comprised empirical, bibliometric, and systematic research identified in English-language publications between 2019 and 2025. For each identified publication, a set of bibliographic and metadata, including year, journal, approach, and theme, was extracted. On this basis, a thematic synthesis was conducted to generate emergent themes, including the balance between conservation and tourism; planning and regeneration; policy and governance; community engagement; marketing, technology, and travel experience; and geoheritage.

To improve transparency on the derivation of the ‘evidence-gap matrix’, the gaps were derived directly from the ‘JBI-based charting, thematic synthesis’ approach as documented under Methodology. Following the extraction of bibliographic details, as well as the metadata (including the ‘year, journal, approach, and theme’) on included studies, the review was able to synthesize the theme of the evidence into six themes: ‘conservation-tourism balance, architecture and planning, policy and governance, community engagement, marketing/technology/experience, geoheritage’.

Within this context, the assessment of the evidence follows the structure of the themes, and the evidence was assessed for fulfilment of RQ4, which focuses on the identified gaps under the themes of standards/metrics, longitudinal monitoring, benchmarking, and the use of technology-enabled approaches. Within this context, the “Missing instrument/metric” indicates the lack of sufficient explicit and standardized measures, within a given theme, within the identified corpus (English-language studies that are fully accessible and have been published during 2019–2025).

It is important to note, however, that in this scoping review, the purpose of the matrix is primarily to provide a descriptive mapping of what has been reported in the identified studies, rather than to assert the unavailability of these tools elsewhere. Thus, one would view the “Suggested next step” column more as a prospective agenda based on the body of evidence synthesized in the matrix.

Based on this synthesis, an evidence gap matrix has been developed to identify research gaps and inform future research on sustainable heritage tourism in Saudi Arabia. During the charting process, citations of Saudi Vision 2030 and the relevant national programs are documented in the form of contextual descriptors (background information/policy context), as the case may be, particularly in the governance policy ‘enabler’ category. However, alignment with the specific Vision 2030 pillars/targets was not used as a criterion of inclusion. The framework of the thematic synthesis follows the outcomes/enablers framework discussed in the Introduction.

To enhance transparency and replicability, an explicit mapping between the research questions, the data charting fields, the analytical steps, and the corresponding outputs has been provided. RQ1 was addressed through descriptive data charting of bibliographic and metadata (year, topic, etc.) to identify publication characteristics and trends. RQ2 and RQ3 were examined through thematic analysis, focusing, respectively, on the conceptualization of sustainability and on the identification of barriers. RQ4 was addressed through a cross-theme synthesis of the charted data to highlight emerging gaps (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mapping RQ, charting fields, and analytic steps in the research (source: authors).

3. Results

From the selection carried out according to the Prisma protocol, 25 documents were included, as charted in the table below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected documents by authors, year, and topic (source: authors).

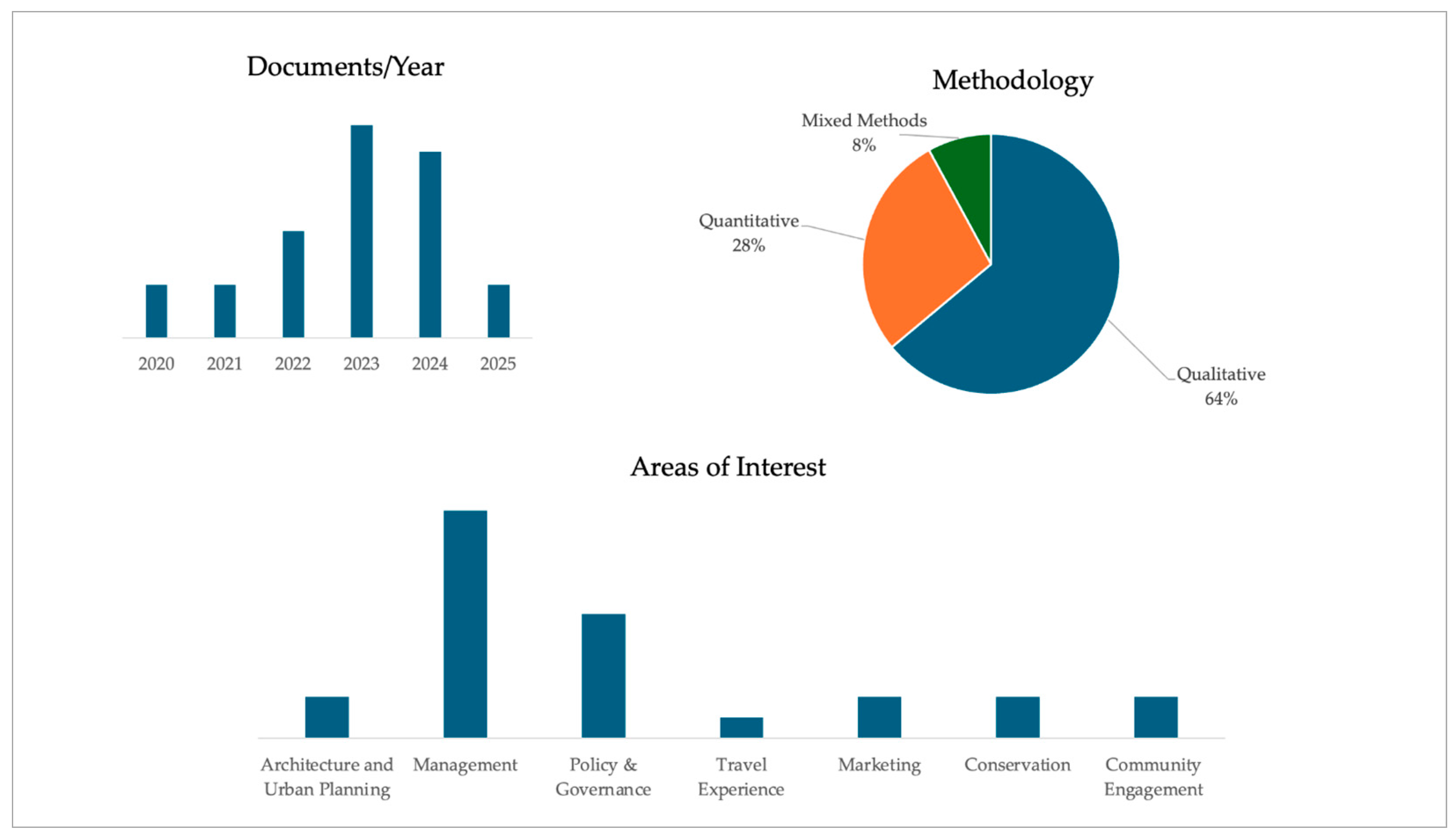

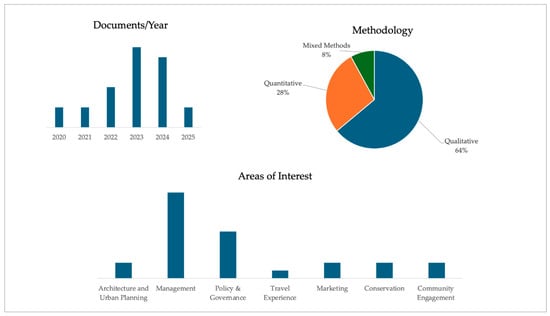

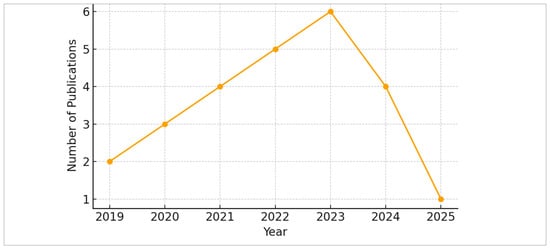

Most of the documents are papers (92%), compared to a limited number of chapters (8%), published in 2023 (8 documents) and 2024 (7 documents). This predominance suggests that sustainability in heritage tourism remains at an early stage of academic consolidation, primarily through journal dissemination rather than edited volumes. Furthermore, the most common methodology is qualitative (64%), followed by quantitative (28%) and mixed methods (8%). The main topics covered include management (40%), policy and governance (20%), architecture and urban planning, marketing, conservation and community engagement (8%), and travel experience (4%). The highlighted themes are those that emerged from a full reading of each selected article, with the central theme identified for articles with multiple cross-cutting themes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Data about the documents, including the number of papers per year, the adopted methodology, and the investigated areas (source: authors).

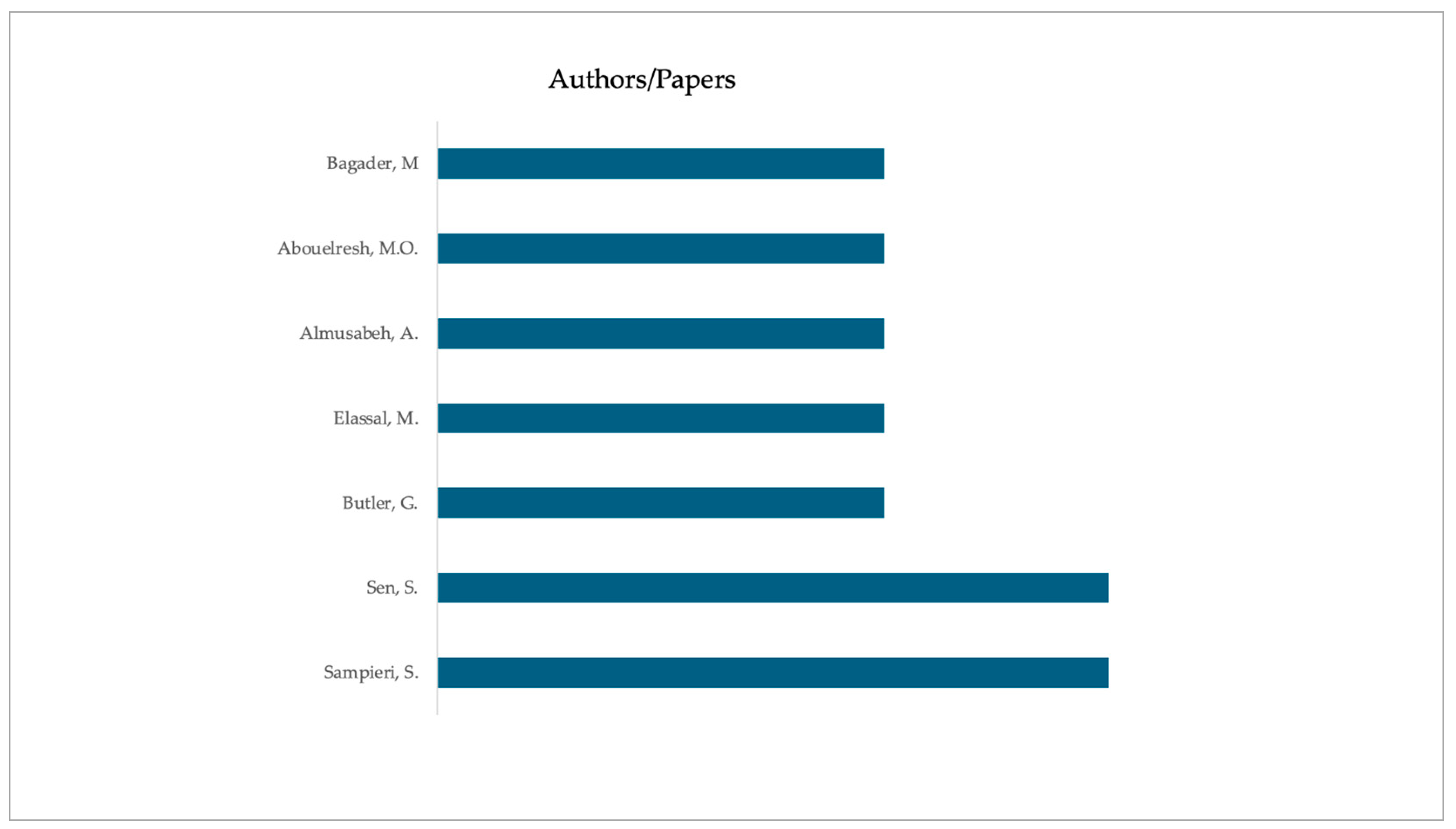

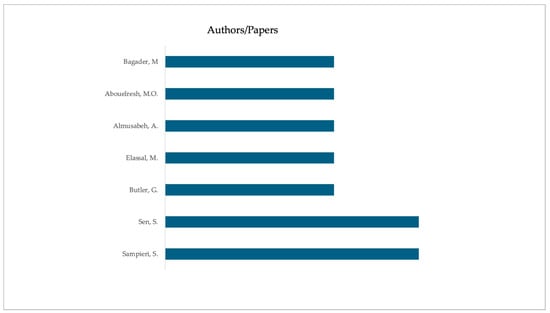

Authors working on sustainable heritage tourism primarily operate in the Arabian Peninsula and have published between one and three papers. Among the most productive researchers in the field are Sampieri and Sen (with three papers) and Butler, Elassal, Almusabeh, Abouelresh, and Bagader (with two papers) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Papers per author—from two to three publications per author (source: authors).

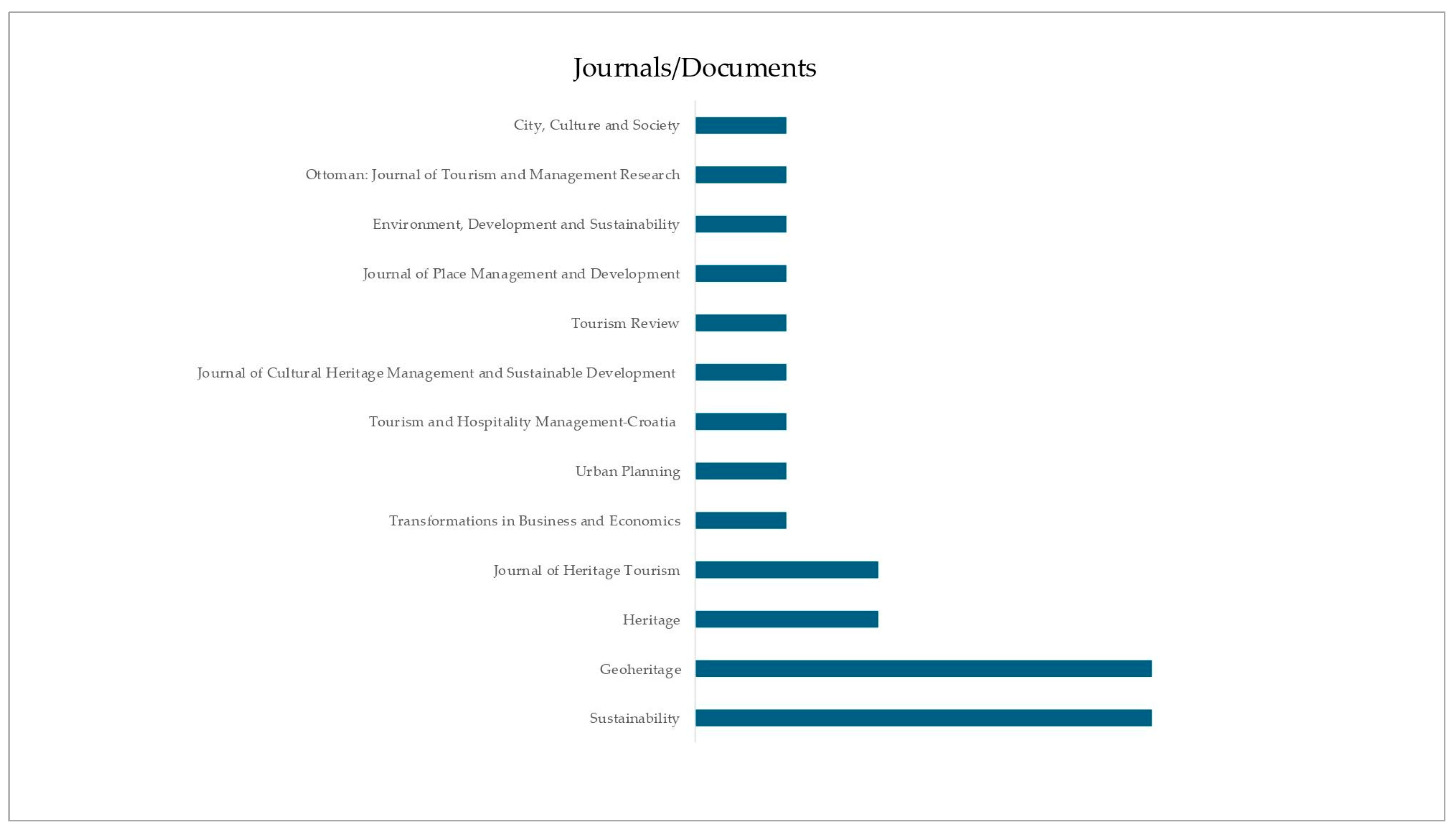

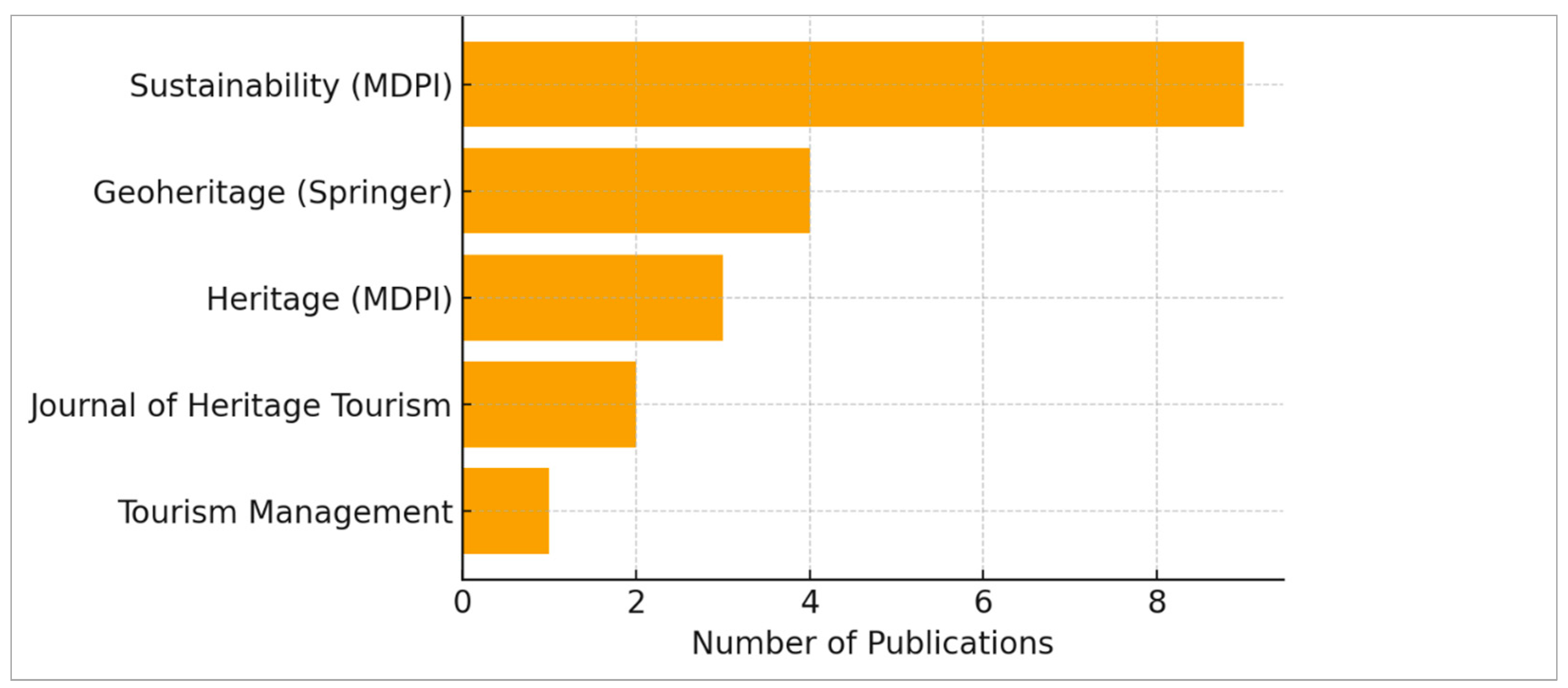

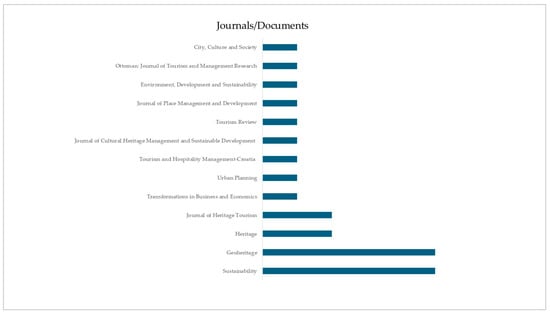

The leading journals chosen for the publications are Sustainability, Geoheritage (5 papers), Heritage and Journal of Heritage Tourism (2 papers), and subsequently City, Culture and Society, Transformations in Business and Economics, Urban Planning, Tourism and Hospitality Management-Croatia, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, Journal of Place Management and Development, Tourism Review, Environment, Development and Sustainability, and Ottoman: Journal of Tourism and Management Research (1 document). In this case, the two selected book chapters are excluded. The prominence of journals such as Sustainability and Geoheritage also highlights the greater emphasis on environmental issues compared to socio-cultural aspects at this early stage of research on sustainability in Saudi heritage (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

List of journals where documents were published (source: authors).

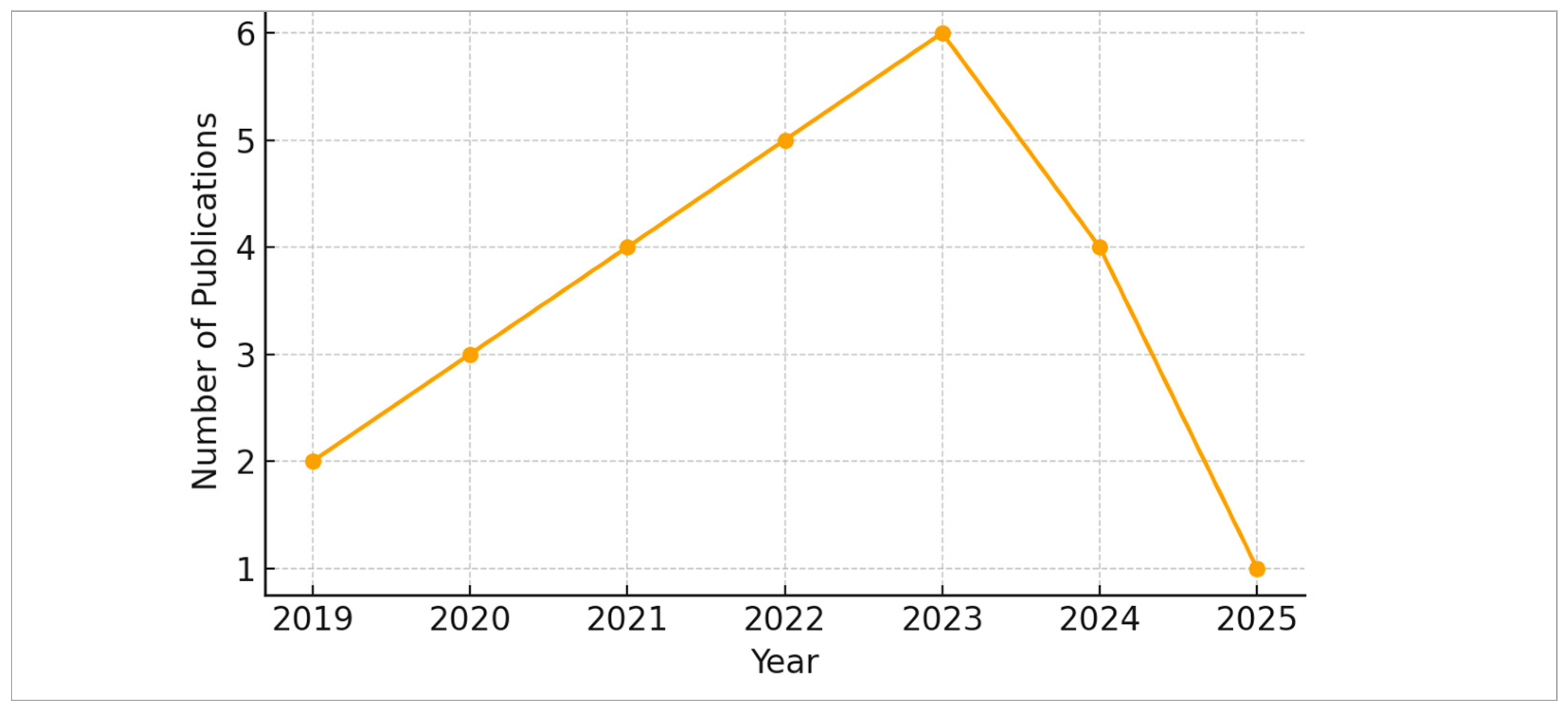

Figure 5 illustrates the increase in research articles published from 2019 to 2025 on the concept of sustainability in Saudi heritage tourism. The increase from 2019 to 2023 indicates a higher level of research interest in the conservation of heritage sites and the development of sustainability within Saudi heritage tourism, aligning with Saudi Vision 2030.

Figure 5.

Publication trend on sustainability in heritage tourism (Saudi Arabia).

From Figure 5, it can be observed that the publication chart shows a steady rise from 2019 to 2023, indicating that research on sustainability in heritage tourism has become a mainstream area of study. The surge can be attributed to the Saudi government’s initiative to make heritage a basis for tourism. The marginal increase from 2024 to 2025 indicates a rise in research interest in specialized subjects, including digital heritage tourism, community development, and mechanisms for heritage tourism development.

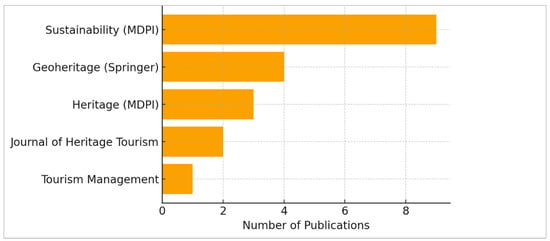

Figure 6 illustrates the top research journals associated with this emerging subject, which are primarily dominated by Sustainability, Geoheritage, Heritage, Journal of Heritage Tourism, and Tourism Management. The five journals combined have contributed to more than two-thirds of the total research articles surveyed, indicating their significant role in the development of research on Saudi heritage tourism.

Figure 6.

Top journals publishing on Saudi heritage tourism sustainability.

The prominence of Sustainability and Geoheritage suggests that the concept of sustainability in heritage tourism has primarily been explored from an environmental-focused perspective, with limited development from a social perspective.

This pattern of dominance in the environment should be interpreted as an expression of the current processes through which knowledge is created in the emergent field of expertise. First of all, the publication ecology of the corpus is strongly influenced by the journals’ scope and the expectations related to peer review, which makes the environmental sustainability aspect more “publishable” and comparable at this stage, rather than the socio-cultural or technology-related aspects.

Secondly, it can be noted that its body is still in a phase of consolidation, and its products were published within a small number of years and found in journals; it continues to maintain a methodological profile that is basically qualitative and often supplies a framing of descriptions on issues of pressure/environmental conservation and protection.

Thirdly, because the tourism industry is relatively newly opened (since 2019), a particular number of works are especially committed to identifying fundamental sustainability issues, wherein environmental effects are more apparent, as opposed to social impacts, which can involve a much longer time scope, for instance, distributive gains. Such is the position of the current literature included.

The high value of Sustainability indicates a lack of specialized research journals focused on heritage tourism, conservation, tourism, and technological development within the context of the Gulf nations.

This pattern likely reflects not only site-specific sustainability concerns but also the current disciplinary and publication structure of the field, in which environmental/geoheritage approaches are more established than social impact measurement and technology evaluation.

4. Existing Topics

The six areas identified in Figure 2 were further analyzed and discussed through thematic interpretation. While Figure 2 groups studies by quantitative frequency (e.g., management, marketing, policy), the following sections synthesize them into broader qualitative themes reflecting emerging patterns in the literature (e.g., technological innovation, geoheritage, and community engagement). In line with the above conceptualization, these areas include the sustainability outcome areas, which are divided into environmental, socio-cultural, and economic, as well as the cross-cutting enablers, which include governance, community engagement, and technology.

- 1.

- Heritage conservation and tourism development

Most studies address the balance between heritage conservation and sustainable tourism development. By analyzing historic sites, authors identify risks, opportunities, and operational strategies. For example, Sampieri & Bagader [13,41] demonstrate that sustainable management of cultural heritage requires a holistic vision that integrates conservation and development. Bay et al. (2022) [32] highlight the need for targeted conservation interventions in the UNESCO site of At-Turaif, while Throsby & Petetskaya (2021) [46] propose methodologies for assessing the impact of heritage-led investments. These three appendix papers, although from different perspectives, focus on governance strategies and guidelines for the sustainable management of tourism heritage. In this case, sustainability emerges significantly as a balance between cultural value and economic profit linked to heritage.

- 2.

- Architecture and urban planning

A second line of investigation addresses how urban planning policies influence heritage conservation. It concerns both impact [39] and valorization [24], addressing current phenomena such as gentrification and the loss of authenticity [38], while balancing the need for development with the demands of protection, regeneration, and reuse (an aspect widely present in the Saudi academic literature). Here, sustainability concerns encompass infrastructure, particularly the selection of materials, design, and utilization.

- 3.

- Policy and governance

A third aspect concerns the development of effective strategies and policies to manage sustainable tourism and coordinate diverse stakeholders, especially in relation to governance. For example, Pavan [47] analyzes how sustainable tourism can strengthen the country’s image, while Altassan et al. [29] argue for coordination among different tourist sites. Finally, Jeribi et al. [37] propose using GIS to manage sustainable access to sites, while Alahmadi et al. [23] explore the perspectives of local SMEs on tourism governance. These studies demonstrate how policy development aligns with the guidelines of Vision 2030. However, while the strategic framework is clearly defined at the national level, the actual implementation of these policies at local and site-specific levels remains uneven. These studies demonstrate how policy development aligns with the guidelines of Vision 2030. The role of policymakers in promoting justice, inclusiveness, and equity is crucial for achieving sustainable governance choices.

- 4.

- Community engagement

A fourth research area concerns the relationship between local communities and heritage conservation. Several studies [26,34] highlight how local participation enhances authenticity and protects cultural assets. Initiatives fostering local stewardship, such as participatory planning, educational programs, and awareness campaigns, are strategic for ensuring that tourism benefits residents and reinforces social sustainability. However, community involvement remains uneven across regions, underscoring the need for inclusive governance models that integrate the social, cultural, and economic dimensions of sustainability. Social sustainability plays a fundamental role in shaping the impact of external factors, the distribution of benefits, and the involvement of actors in the development process.

- 5.

- Marketing, technology, and travel experience

A fifth area of interest concerns marketing strategies, visitor experience, and the role of technology in promoting sustainable heritage tourism. Research on visitors’ emotional responses [25] and cultural revival [31] demonstrates how authenticity and storytelling shape satisfaction and loyalty. At the same time, studies on innovative and digital tourism [35,37] emphasize how technological innovation supports destination management through data collection, AI-based recommendation systems, and mobile applications for heritage sites. However, there remains a lack of analysis of the environmental impact and ethical dimensions of using technology to enhance accessibility, improve interpretation, and strengthen the experiential quality of visits. In this case, the social impact of tourism is observed from the hosts’ perspective, not from the guests.

- 6.

- Geoheritage and environmental sustainability

The last thematic area of investigation focuses on geoheritage and the integration of natural and cultural landscapes as drivers of sustainable development. Authors such as Sen et al. [44,45] and Elassal [33] demonstrate how geosites, including Tuwaiq Mountain and Al-Soudah, contribute to diversifying tourism beyond urban and cultural heritage, aligning with the landscape approach [48]. These studies highlight the relevance of geoethics, geoconservation, and educational value, proposing models that combine environmental protection with tourism planning. In this last point, the research extends, according to the definition of heritage, not only to historical, architectural, and archaeological assets, but also to natural and landscape assets.

4.1. Publication Profile (2019–2025)

The field is young but accelerating and growing, reaching a peak in 2023–2024. It remains concentrated in the areas of Sustainability, Geoheritage, and Heritage, followed by the Journal of Heritage Tourism. The research design remains biased towards qualitative research, which accounts for 64% of the research, while quantitative research accounts for 28% and mixed-method research accounts for 8%. The research remains Saudi Arabia-defined, as it involves collaborations within Saudi Arabia. The research focuses on areas such as geoheritage, including Tuwaiq and Al Soudah, as well as heritage-driven urban regeneration, including Diriyah and Tarout, all of which are encompassed within the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. Vision 2030 is referenced to indicate the national policy context in which the reviewed studies are situated; it does not structure the thematic categories reported in Table 3. The defining criteria set a basis for comparison, much like bibliometric scanning conducted within reviews of adjacent areas of urban technology research, thereby determining gaps within research structures, such as a lack of longitudinal research. The selected research works focus on the issue of sustainability from two overlapping perspectives: (a) triple bottom line outcomes encompassing environment, socio-cultural factors, and economic considerations; and (b) cross-cutting enablers of implementation in the areas of governance/policies, community participation, and socio-technical approaches. The major focus of each theme is described in detail in Table 3 [49].

Table 3.

Primary sustainability focus on each emerging theme (outcome vs. enabler) (source: authors).

The data presented in Table 3 are categorized under six major themes: conservation and tourism, architecture and planning, governance and policy, community, marketing and technology, and geoheritage and environmental sustainability. The themes are further divided into two categories of orientation: themes of orientation to outcomes of sustainability and themes of orientation to the implementation methodology of sustainability.

Outcome-oriented themes (sustainability outcomes):

1. Heritage conservation and tourism development (economic outcomes);

2. Architecture and planning (environmental/physical results);

3. Geoheritage and environmental sustainability (environmental outcomes).

Themes for enabler-oriented perspectives (implementation):

1. Policy and governance (coordinating multiple actors, management of sites, destination strategies);

2. Community involvement: attachment, stewardship, equity;

3. Marketing, technology, and experience (storytelling, services, and monitoring tools).

Combined, these issues reflect the technology/policy/society framework that has long been considered integral to digital transformation on an urban scale, suggesting a straightforward means of adopting mature sustainability and governance instruments in a heritage tourism setting.

An assessment has been conducted, revealing that although each theme encompasses a unique research avenue, gaps in methodologies and ideas can be identified. Table 4 consolidates the six primary areas of research on Saudi heritage tourism, identifies the missing instruments, explains their relevance, and outlines a detailed action plan. This form of research structuring is often utilized within a smart city assessment.

Table 4.

Evidence gap matrix for Saudi heritage tourism sustainability.

In Table 4, the “missing instrument/metric” column is used in a corpus-contained manner. Here, each themed grouping of studies in the corpus does not provide sufficient explicit, standardized instrumentation—think of these as collective ‘indicators/metrics,’ monitoring and evaluation structures, or comparable benchmarks—to allow easy tracking of sustainable performance across sites or over time. When technology-influenced methods appear in the corpus of studies considered in this research, the matrix indicates that performance criteria and monitoring procedures remain inadequately defined to monitor performance against sustainable criteria effectively. Thus, the “Suggested next step” column of the table can be viewed as an anticipatory research agenda based on the evidence mapped out in Research Question 4 (RQ4).

To frame the “gaps” identified through the mapping of “evidence gaps” within a wider national frame, it is helpful to differentiate between (a) the policy–practice momentum and (b) the academic evaluation and reporting paradigms.

Vision 2030 explicitly prioritizes cultural heritage on the national agenda. Priorities for the restoration of cultural sites and the improvement in cultural offerings are now encapsulated in the Saudi Vision Realization Programs, which include targets and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for culture and tourism streams. On the other hand, institutions and guidance within the cultural heritage community encourage a focus on documenting and digitizing cultural heritage resources. A focus on the country’s guidance on cultural heritage, as well as on digitization and archiving, is encouraged through national platforms and tools available to the community. However, the scope of the existing peer-reviewed set of Saudi-related publications identified by the scoping review reveals that the existing policy–practice momentum has failed to map standardized measurement frameworks related to social impacts (equity and beneficiaries and benefits sharing and social co-production) and technological performance (benchmarks and interoperability and continual monitoring strategies) on a repeatable basis and pace related to social impacts and technological performance factors and requirements related to the Saudi setting and community.

To locate the mapped “evidence gaps” against the broader national context, it is helpful to distinguish between

(a) Policy–practice momentum;

(b) Academic evaluation and reporting.

Vision 2030 explicitly positions cultural heritage as a national priority, including objectives to restore cultural sites and enhance cultural offerings, and it is implemented through Vision Realization Programs that include culture- and tourism-related targets and KPIs. In parallel, heritage sector institutions and guidance documents indicate an active push towards documentation and digitization (such as national guidance on cultural heritage documentation and digital archiving, as well as dedicated heritage platforms and resources). However, the scoping review shows that the peer-reviewed Saudi-focused corpus has not yet consistently translated this policy–practice activity into standardized, repeatable measurement frameworks, particularly for social impacts (equity, distribution of benefits, participation) and for technology performance (benchmarks, interoperability, longitudinal monitoring protocols). The “gaps” reported in this study, therefore, primarily reflect a limited published evaluation using comparable indicators.

Table 4 illustrates the consolidation of the six topic areas identified within heritage tourism studies in Saudi Arabia, highlighting the missing elements within existing instruments or metrics, justifying their relevance, and suggesting potential actions. This approach to analysis reflects a model standard for assessing smart cities and Digital Twins, facilitating comparison across both areas and thereby prioritizing future research. The following summary, as outlined in Table 4, indicates a lack of industry-wide standardization regarding indicators and metrics to facilitate progress towards sustainability. The closure of these knowledge gaps will necessarily involve collaboration, integrating digital documentation systems, and conformity to UNESCO’s approach to the Historic Urban Landscape.

Data highlight an imbalance in the treatment of data related to the three pillars of sustainability, the implementation of governance mechanisms, and, in particular, the adoption of technologies. These aspects, which are extremely broad and well covered in the international literature, are in fact not widely represented in the Saudi Arabian literature. However, there is a significant gap between what is proposed in the literature and what is actually implemented in practice.

For example, among the three pillars of sustainability, there is a particular lack of information and sources on environmental sustainability. Yet, looking at the Al Ula sustainability report, it is evident that this topic is not only widely addressed but also addressed through significant sustainable practices. The same can be said for technology, which is not extensively discussed in the context of heritage tourism but is widely embedded in everyday life, including digital content management and data digitization.

Thus, while the literature sheds light on certain significant aspects not covered by the international literature, it remains distant from the empirical data observable in the field. It can therefore be hypothesized that, in the future, a rich body of literature will emerge to describe these implemented but as yet under-theorized phenomena.

Moreover, there is a very different approach to applying sustainable governance models, which, in a country like Saudi Arabia, is top-down and therefore closely linked to the previously mentioned Saudi Vision 2030. This results in an implementation and thus an alignment of governance models that are poorly described because they are highly standardized in form, with strategies that closely adhere to a predefined program. It would be interesting to observe what potential scenarios might emerge if the model were to become slightly more bottom-up, and how the literature would then orient itself in relation to the existing data.

One significant element that emerges, however, is precisely the discrepancy between the literature and reality, although the literature from these emerging countries, including Saudi Arabia, already differs from the international literature due to the rapid growth of emerging travel destinations.

4.2. From Principles to Instruments in Alignment with Saudi Vision 2030

The current state of heritage tourism research in Saudi Arabia has increasingly shifted from exploring the rationale for sustainability implementation to analyzing ways to implement it successfully. Nonetheless, these subjects lack standard tools for analyzing and managing sustainability implementation. The development in this context, from rationale to results, can be achieved by creating a comprehensive system that integrates sustainability indicators in accordance with Saudi Arabia’s sustainability vision outlined in Vision 2030. There are three elements that must be integrated to achieve this transformation:

- The development of common standards and interoperable indicators to measure sustainability performance.

- The development of a reliable database and monitoring system to record the pressures on, status of, and benefits derived from tourism.

- The encouragement of transparent mechanisms of governance, which include local participation, accountability, and management within the operations of heritage sites.

Building on the mapped evidence, four priorities emerge as a future research-and-practice agenda for Saudi heritage sites:

Firstly, a standard set of indicators on sustainability could be incorporated on a national level, including dimensions such as environmental carrying capacity, social equity benefits, contributions from local enterprises, as well as authenticity/interpretation quality.

Secondly, site management plans should feature adaptive thresholds, where simple systems of environmental and visitor flow monitoring can support triggers for crowd management, route rotation, and seasonality.

Thirdly, a set of data-sharing best practices must be established to facilitate interoperability between heritage, local, and research organizations, as well as the responsible use of data.

Finally, public participation mechanisms should be institutionalized within community councils or forums, where annual sustainability reports can be shared.

5. Emerging Gaps

Future research perspectives encompass both the research areas and methodologies, as well as their potential impact on these areas.

In a broader view of sustainable tourism, this imbalance can also be attributed to a focus on the more standardized domains of sustainability, usually those of the environment. The social, on the other hand, presents a certain degree of complexity in methodologies. It can also be observed in the Saudi-based body of texts being analyzed that the social environment is less developed than the environment. On the other hand, social or socio-technical monitoring or sustainability measures, for that matter, have not been implemented in a standardized or easily replicable manner. This is also evident in the review’s highlighting of the use of murky language in benchmarking instruments. It can also be said that, rather than being a non-existent theme, it highlights a trend in research development: the early stages set the standards for the environment, while subsequent stages require a particular interdisciplinary approach to monitor the spread of benefits, communities, and the effectiveness of governance.

As summarized in the evidence gap matrix (Figure 7), research remains fragmented, with limited empirical attention to the following:

- Experiential tourism: research should examine experiential tourism and how visitor behavior impacts sustainable practices and responsible heritage valorization [50].

- Integration of natural and historical environments: studies on the environment could be integrated, as they are currently treated mainly separately, while the international literature tends to synthesize common aspects.

- Alignment with Vision 2030: future research could align with the objectives of Vision 2030, particularly regarding economic diversification and national cultural identity, to develop recommendations and pathways for regional development and management by tourism developers [51].

Figure 7.

Future agenda according to topic, methodology, and impact (source: authors).

Figure 7.

Future agenda according to topic, methodology, and impact (source: authors).

As highlighted in the same evidence gap matrix, the spatial–temporal dimension and methodological approach, such as longitudinal policy tracking, should be implemented. In the former case, both comparative studies with other cases in the Middle East and globally (spatial) and longitudinal (temporal) studies should be introduced. In this context, cross-country benchmarking is not employed as a causal or explanatory device for differences in heritage tourism management outcomes. Instead, it is used as an exploratory and methodological tool to identify governance instruments, monitoring frameworks, and evaluation practices that are currently underrepresented in the Saudi-focused literature. Differences in management approaches across countries are shaped by distinct institutional arrangements, historical trajectories, and socio-political contexts, which cannot be captured solely by benchmarking exercises. This approach would highlight long-term trends and allow for the generation of replicable guidelines (scaling) on a comparative and evaluative basis.

Furthermore, quantitative methods should be used more widely to collect numerical data, especially on environmental, economic, and social impacts. This would facilitate assessments of sustainability levels, aiding future investments and policy decisions. For example, researchers in Angkor (Cambodia) investigated the sustainable management of the site through a longitudinal methodology, developing a framework later adopted by UNESCO to highlight the challenges and solutions in the sustainable management of heritage sites [48]. In the same way, sites such as Al Ula can become a model of sustainability in the Middle East.

Regarding its impact, it has become apparent that a crucial issue is balancing heritage conservation and tourism development, particularly in relation to local communities.

However, from the Saudi-focused body of literature canvassed here via the scoping method (2019–2025), the empirical research available that puts the ideas of sustainable heritage into practice, developing sets of indicators and core governance tools, is relatively sparse on the ground. However, as will become important below, that does *not* say that the topic of sustainable heritage has not had extensive treatment by the international community of scholars since the 1970s, for example, under the aegis of community-based and community-driven concepts of heritage management via so-called “ecomuseums and community museums,” or more generally since the mid-2000s via ISCS and UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape Recommendation and related Sustainable Development work on heritage and development.

The problem posed and attempted to be resolved here is therefore somewhat narrowly defined, related to the operationally standardized and comparable treatment of the subject matter in the Saudi-focused literature on heritage-based tourism [52,53,54].

For example, the site of Xijiang (China) has been studied in the light of community participation, highlighting the existing gaps and suggesting actionable tools [55]. The same goals can be achieved in Saudi heritage sites through embedded research, similar to what is undertaken in China. This example is not intended as a normative model for direct transfer. Still, as an illustration of how embedded, context-sensitive research can generate operational tools that may inform, rather than be replicated within, the Saudi heritage management context.

A second aspect of the research impact concerns international collaborations. While the professional sector operates in a global context, academic research in Arabia still primarily comes from Saudi-affiliated researchers; international collaborations could offer new and diverse perspectives, thereby avoiding epistemic isolation. A successful case is Petra (Jordan), where a global team of researchers from Jordan, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, and UNESCO developed a methodology to evaluate the risks associated with conserving the archaeological site, promoting international and interdisciplinary dialogue [56]. The global collaboration that the Kingdom is establishing, even at the scholarly level, can significantly enrich the quality and perspective of research, highlighting Saudi heritage sites on the global stage. These international experiences provide concrete lessons that can inform the sustainable management of Saudi heritage sites, offering transferable methodologies and frameworks adapted to the local context (Figure 7).

Building on the gaps identified in Figure 7, future studies should prioritize topics that have been partially addressed, in particular, the tourist experience, given that the country is only beginning to approach tourism and the role of Saudi Vision 2030 as a program to enhance tourism. It involves evaluating both positive aspects and existing challenges. However, the study should also aim to adopt a broader methodology, primarily through longitudinal approaches, because there is currently no temporal mapping of the observed phenomena; they are mostly confined to the immediate context. It is also because these emerging countries have a short history that there is no established historical data series, which needs to be constructed and will form the future research database. Comparative studies can enhance certain aspects, particularly by relating them to contexts with a long-standing tourism history, to facilitate the transfer of knowledge that underpins research aimed at sustainability goals. Collaboration becomes essential both within the country’s social fabric through community involvement and international cooperation, precisely because Saudi Arabia, like many emerging countries, lacks a long history of tourism research. Therefore, communication and knowledge sharing have added value.

5.1. Social Impact

In a context of emerging travel destinations with just 10 years of experience in modern tourism, this research offers an interesting perspective on the conceptualization of sustainability in heritage tourism. In particular, the results of this research have a significant impact on academics, policymakers, and society.

In terms of academic contribution, the results provide a roadmap for future research that expands the discipline’s knowledge.

Furthermore, the proposed implementation of new methodologies helps generate practical frameworks for policymakers at both national and international levels. The findings can directly inform local tourism policies and capacity-building programs, particularly in heritage-sensitive areas such as Al Ula and Diriyah.

Ultimately, the findings of sustainable tourism research can have a profound social impact, contributing to regional economic development and community well-being, in line with the objectives of the Saudi 2030 agenda [39].

5.2. The Contribution of Emerging Destinations to the Global Discourse

While many established tourist destinations, such as those in Europe, have long considered heritage sustainability as an exclusive form of conservation, emerging destinations like Saudi Arabia, Rwanda [57], and Costa Rica [58] approach sustainability from a broader perspective, encompassing historical–architectural heritage, as well as natural and landscape heritage. They adopt a systemic view of sustainability, integrating multiple perspectives that make heritage inherently a site of contrast [59], but precisely for this reason, reveal complexities that cannot be reduced solely to the aspect of conservation. However, conservation remains essential to the definition of cultural heritage.

It is clearly visible, for example, in the case of Jeddah, where in the early UNESCO reports, sustainability was primarily associated with restoration and conservation, particularly architectural restoration [13]. Over time, especially with the onset of tourism in 2019 [60] the approach has become increasingly holistic and structured within a framework encompassing various aspects, making sustainability a central principle of the development process [61].

The new approach also allows for the inclusion of dynamics that were previously excluded from mere conservation, which had remained confined within the boundaries of the heritage site [62]. The development principle proposed by these new destinations, in contrast, transcends the site’s spatial dimension, encompassing stakeholders and phenomena that are not only directly related to the site but also indirectly involve third parties, such as the local community, businesses, and the broader context in which the site is located. These elements thus become central, rather than marginal, to the management process [63].

Therefore, the contribution of these destinations, including Saudi Arabia and others, is to shift the focus from a conservation-centered dimension to one of development, and from a localized and reductive approach focused solely on conservation and restoration to a much more holistic and complex vision [53,55]. This approach requires more adequate tools and a more articulated understanding of the phenomenon, but it is also more realistic and, consequently, more sustainable.

5.3. Limitations

This research presents two limitations. Firstly, unlike systematic reviews in the related field, this scoping review could not rely on a registered protocol in PROSPERO. This is because a specific protocol in the Saudi context has not yet been registered. Consequently, PRISMA was explicitly used as a pioneering study for this purpose, ensuring monitoring and transparency in the selection process through the creation of a protocol with a specific purpose.

A second aspect of this research concerns its geographical context. In fact, Saudi Arabia, unlike other tourist destinations with a more extended history of tourism, has only recently opened its doors to tourism. This places it in a unique position but also exposes it to significant limitations. Firstly, the researchers primarily focus on Saudi Arabia and specific well-known sites, which limits comparisons across sites within and outside the country. Furthermore, the lack of quantitative data reduces the likelihood of applying frameworks; however, emerging results provide a realistic picture of the current state of the art in the sector’s knowledge base and strategies for tourism sustainability. These aspects contribute to the usefulness of this research, which is both unique in form and valuable in substance, thereby facilitating further progress in the years to come.

Additionally, it demonstrates how a country can rapidly scale the necessary steps to become internationally competitive. Despite these limitations, this review represents the first systematic attempt to map sustainable heritage tourism research within the Saudi context.

A further limitation concerns the interpretative scope of cross-country comparisons. While international cases are referenced to inform methodological development, differences in heritage tourism governance between Saudi Arabia and other emerging destinations, such as China, are rooted in divergent institutional capacities, governance structures, and timelines of tourism development. As such, benchmarking alone cannot explain variations in management performance, but it can contextualize potential adaptation pathways within the Saudi setting.

Finally, the evidence gap matrix should be read as a mapping of what was observable from the included corpus, including the English-language literature published from 2019 to 2025 and fully accessible throughout the eligibility phase. Thus, it does not intend to show that instruments and such tools for monitoring do not exist outside of those works considered in this review; instead, it shows what is available and synthesized from these works included in these studies as provided in the review protocol and as mentioned, works that were selected yet non-accessible were considered at this point and hence relevant instruments and operational tools may also be found outside those completely accessible works considered in this study.

A subsequent area of analysis would be to triangulate the identified evidence in the existing academic literature with the policy manuals, program key performance indicators, site-level management plans, and monitoring reports under Vision 2030.

6. Future Research Direction

Future research on the sustainability of Saudi heritage tourism can focus on formulating a set of national standards that include indicators, criteria for data quality, and ethical considerations, enabling comparisons across different tourist sites. The use of comprehensive assessment frameworks can also facilitate informed decision-making, especially within the context of Saudi Vision 2030. In addition, research studies can adopt a comprehensive approach that integrates all three dimensions: the environment, society, and economics. It can make it easier to consider trade-offs between the cost of conservation and its impact on both residents and tourists. Another research topic can be explored through a comparative approach, analyzing tourist sites within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and regional counterparts to gain insight into the effectiveness of management measures, policies, and investment frameworks.

Based on research findings, a matrix can be established for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The matrix can prioritize challenges concerning heritage tourism sustainability, such as impact assessment, authenticity, and equity, as well as other challenges, based on their level of significance and potential impact. In this regard, research can shift attention towards recognizing the importance of socio-technical factors, as well as their roles in facilitating the adoption of advanced technology. This research can encompass aspects such as the readiness of institutional stakeholders, employee competencies, and building trust, as well as addressing ethical issues related to data collection and use.

In this topic, research can be conducted on the use of Heritage Buildings Information Modeling, as well as other advanced systems, such as Geographic Information Systems and sensors, within the context of creating comprehensive systems at famous heritage tourist sites, including Diriyah and Al Ula.

7. Conclusions

There has been a substantial increase in research on sustainability within heritage tourism in Saudi Arabia, particularly in the context of the Kingdom’s push for cultural sustainability and diversification of the tourism sector, in line with the ambitious agenda outlined in Vision 2030. Even so, the research within this theme has been distinguished by a lack of cohesion within research methodologies, indicators, and government frameworks, making it difficult to measure progress within the theme. The next step in developing research on this theme would be the implementation of sustainability treaties, rather than continuing abstract discussions on the topic. The presentation of comprehensive frameworks within social, environmental, and economic elements would undoubtedly contribute to more effective heritage resource management, while also creating a future in which tourism development has a positive impact on the well-being of local populations. The adoption of collaborative research, as well as digital heritage documentation, within these streams would contribute to making Saudi Arabia a leader in heritage sustainability as it pursues the agenda outlined in the concept of Saudi Vision 2030.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S.; software, S.S.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S. and S.M.; investigation, S.S. and S.M.; resources, S.S.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and S.M.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, S.S. and S.M.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. Prisma Protocol: S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge Prince Sultan University and its Research and Initiatives Center (RIC) for covering the article processing charges (APC) and providing financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Prince Sultan University for fostering a research-driven and collaborative academic environment that encourages innovation and scholarly excellence.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of the selection phases followed during the review process.

Table A1.

Description of the selection phases followed during the review process.

| Phase | Action | Tools and Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of the query | “Tourism” AND “Heritage” AND “Saudi Arabia” |

| Database + manual research | Scopus, WoS, Google Scholar, ResearchGate |

| Removing duplicate | Removing duplicate |

| Screening based on the abstract and title | Double-blind selection based on pertinence to the RQ. Papers selected by at least one of the researchers are included |

| Screening based on full text | Double-blind selection based on pertinence to the RQ. Papers selected by both of the researchers are included—selected but not accessible documents were removed |

| Inclusion of documents | Qualitative/quantitative coding, thematic mapping |

References

- Filippi, L.D.; Mazzetto, S. Comparing AlUla and The Red Sea Saudi Arabia’s Giga Projects on Tourism towards a Sustainable Change in Destination Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Planning for Tourism: The Case of Dubai. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2008, 5, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing Sustainable Tourism Development: The 2030 Agenda and the Managerial Ecology of Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. UN Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/UNWTO_UNDP_Tourism%20and%20the%20SDGs.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Martín-Samper, R.C.; Köseoglu, M.A.; Okumus, F. Hotels’ Corporate Social Responsibility Practices, Organizational Culture, Firm Reputation, and Performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S. Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability: Principles and Practices. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable Tourism: An Evolving Global Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.; Jamal, T. An Integrated Approach to “Sustainable Community-Based Tourism”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budeanu, A. Impacts and Responsibilities for Sustainable Tourism: A Tour Operator’s Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severini, G. L’immateriale Economico Nei Beni Culturali. In Immateriale Economico Nei Beni Culturali; Morbidelli, G., Bartolini, A., Eds.; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2018; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Back, A.; Lundmark, L.; Zachrisson, A. Bridging (over)Tourism Geographies: Proposing a Systems Approach in Overtourism Research. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, M. Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case Study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampieri, S.; Bagader, M. Heritage Conservation and Tourism Development in Saudi Arabia: The Case of Historic Jeddah. In The Innovative Pathway on Sustainable Culture Tourism; Pivac, T., Castanho, R.A.M.D., Martinelli, E., Gonçalves, E.C.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.I. Saudi Vision 2030: New Avenue of Tourism in Saudi Arabia. Stud. Indian Place Names 2020, 4, 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- GOV.SA. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision. 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Sirror, H. Lessons Learned from the Past: Tracing Sustainable Strategies in the Architecture of Al-Ula Heritage Village. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwidar, S.; Metwally, W.; Abbas Abdelsattar, A. Analytical Study of Heritage Residential Buildings in the Central Region of Saudi Arabia. JES. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 48, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Sustainable Heritage Conservation in the Gulf Regions; Vimonsatit, S., Singh, A., Yazdani, S., Eds.; ISEC press: Fargo, ND, USA, 2022; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Heal. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, A.; Butler, G.; Szili, G. Tourism Development at the Al-Hijr Archaeological Site, Saudi Arabia: SME Sentiments and Emerging Concerns. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossary, M.J.; Alqahtany, A.M.; Alshammari, M.S. Cultural Heritage as a Catalyst for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: The Case of Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algassim, A.A.; Saufi, A.; Scott, N. Residents’ Emotional Responses to Tourism Development in Saudi Arabia. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhefnawi, M.A.M.; Lawal Dano, U.; Istanbouli, M.J. Perception of Students and Their Households Regarding the Community Role in Urban Heritage Conservation in Saudi Arabia. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 13, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mohammad, S.; Butler, G. Tourism SME Stakeholder Perspectives on the Inaugural “Saudi Season”: An Exploratory Study of Emerging Opportunities and Challenges. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mohaya, J.; Elassal, M. Assessment of Geosites and Geotouristic Sites for Mapping Geotourism: A Case Study of Al-Soudah, Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altassan, A. Sustainability of Heritage Villages through Eco-Tourism Investment (Case Study: Al-Khabra Village, Saudi Arabia). Sustainability 2023, 15, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tokhais, A.; Thapa, B. Management Issues and Challenges of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, M. Exploring Heritage Tourism in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study of Cultural Revival. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2024, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, M.A.; Alnaim, M.M.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Noaime, E. The Heritage Jewel of Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Analysis of the Heritage Management and Development Activities in the At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS). Sustainability 2022, 14, 10718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elassal, M. Geomorphological Heritage Attractions Proposed for Geotourism in Asir Mountains, Saudi Arabia. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S. Community Attachment to AlUla Heritage Site and Tourists’ Green Consumption: The Role of Support for Green Tourism Development. Heritage 2024, 7, 2651–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sofany, H.F.; Abou El-Seoud, S. The Effectiveness of Tourism in KSA Using Mobile App During COVID-19 Pandemic; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 559–570. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi, R.; Touati, M.S.E.; Alsharif, B.N. Determinants of Tourism in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Its Impact on Sustainable Development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 32217–32228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeribi, F.; Perumal, U.; Alhameed, M.H. Recommendation System for Sustainable Day and Night-Time Cultural Tourism Using the Mean Signed Error-Centric Recurrent Neural Network for Riyadh Historical Sites. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingmann, A. Re-Scripting Riyadh’s Historical Downtown as a Global Destination: A Sustainable Model? J. Place. Manag. Dev. 2022, 15, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Sustainable Heritage Preservation to Improve the Tourism Offer in Saudi Arabia. Urban. Plan. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, A. A Conceptual Investigation of the Transformation of AlUla into a Global Tourism Destination: Saudi Arabia Rediscovers Its Pre-Islamic Heritage and Bets on Cultural Diplomacy. Ottoman J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2023, 8, 1152–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Sampieri, S.; Bagader, M. Sustainable Tourism Development in Jeddah: Protecting Cultural Heritage While Promoting Travel Destination. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampieri, S.; Saoualih, A.; Safaa, L.; de Carnero Calzada, F.M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Martínez-Peláez, A. Tourism Development through the Sense of UNESCO World Heritage: The Case of Hegra, Saudi Arabia. Heritage 2024, 7, 2195–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Migoń, P.; Almusabeh, A.; Abouelresh, M.O. Jabal Al-Qarah, Saudi Arabia—from a Local Tourist Spot and Cultural World Heritage to a Geoheritage Site of Possible Global Relevance. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Almusabeh, A.; Abouelresh, M.O. Geoheritage and Geotourism Potential of Tuwaiq Mountain, Saudi Arabia. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Abouelresh, M.O.; Santra, A.; Al-Musabeh, A.H.; Al-Ismail, F.S. Geoheritage Assessment of the Geosites in Tuwaiq Mountain, Saudi Arabia: In the Perspective of Geoethics, Geotourism, and Geoconservation. Geoheritage 2024, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D.; Petetskaya, K. Heritage-Led Urban Rehabilitation: Evaluation Methods and an Application in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 26, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, A. The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques’ Overseas Scholarship Program: Targeting Quality and Employment. World J. Educ. 2017, 7, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNESCO. WHC Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Kutch, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN Tourism. Statistical Framework for Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (SF-MST); UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dwidar, S.; Abowardah, E. Internal Courtyards One of the Vocabularies of Residential Heritage Architecture and Its Importance in Building Contemporary National Identity. In Proceedings of the International Architecture and Urban Studies Conference “House & Home”, Istanbul, Turkey, 2 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzetto, S. Fostering National Identity Through Sustainable Heritage Conservation: Ushaiger Village as a Model for Saudi Arabia. Heritage 2024, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, A.; Ciesielska, M. Ecomuseums as Cross-Sector Partnerships: Governance, Strategy and Leadership. Public Money Manag. 2016, 36, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavese, G.; Gianotti, F.; de Varine, H. Ecomuseums and Geosites Community and Project Building. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2018, 6, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, G. Community-Based Processes for Revitalizing Heritage: Questioning Justice in the Experimental Practice of Ecomuseums. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Man, T.; He, L.; He, Y.; Qian, Y. Delineating Landscape Features Perception in Tourism-Based Traditional Villages: A Case Study of Xijiang Thousand Households Miao Village, Guizhou. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Risk Management at Heritage Sites: A Case Study of the Petra World Heritage Site; UNESCO: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Okumu, P. Exploring Green Practices, Opportunities and Challenges Facing Tourism and Hospitality Industry for Sustainable Future in Rwanda. J. Glob. Hosp. Tour. 2025, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Propositiva. Turismo Sostenible en Costa Rica, 2025. Available online: https://www.propositiva.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Morbidelli, G. Introduzione. In I Musei. Disciplina, Gestione, Prospettive; Morbidelli, G., Cerrina-Feroni, G., Eds.; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2010; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Saudi Arabia to Open up to Foreign Tourists with New Visas; BBC News: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S.; Saviano, M. Dalla Gestione Del Patrimonio Di Beni Culturali al Governo Del Sistema Dei Beni Culturali (From the Management of Cultural Heritage to the Governance of Cultural Heritage System). In Patrimonio Culturale E Creazione Di Valore, Verso Nuovi Percorsi; Golinelli, G.M., Ed.; Cedam: Padova, Italy, 2012; pp. 97–148. [Google Scholar]

- Montella, M. Valore e Valorizzazione Del Patrimonio Culturale Storico; Electa: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Paniccia, P.M.A.; Baiocco, S. Interpreting Sustainable Agritourism through Co-Evolution of Social Organizations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.