Abstract

The tilework of Talavera de la Reina (Toledo, Spain) was declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2019, with one of its landmarks being the tilework preserved in the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado, known as the ‘Sistine Chapel of Talavera tilework’. In the entrance portico to the Basilica, we find the ceramic panel of Virgins and Tercios in front of Christ, which should be reinterpreted as two different compositions: virgins in front of Mary and tercios in front of Christ (milites Christi), on which we will focus our research. The analysis of the location and state of conservation of the pieces that currently make up this panel, as well as the existence of pieces in various areas of the Basilica, which most likely belong to each of the compositions, allow us to propose a recomposition and reintegration of elements that would enable a better view and interpretation of these panels. To this end, a scientific methodology and appropriate intervention criteria are proposed to completely recompose this panel through the restoration of all the necessary pieces. This example can be extrapolated to the rest of the altarpieces and interior panels of the Basilica, which would facilitate their proper conservation, interpretation and dissemination.

1. Introduction

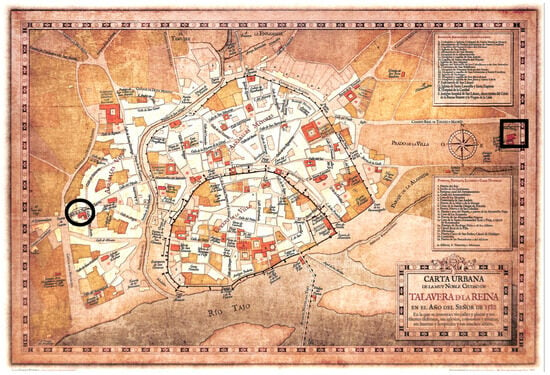

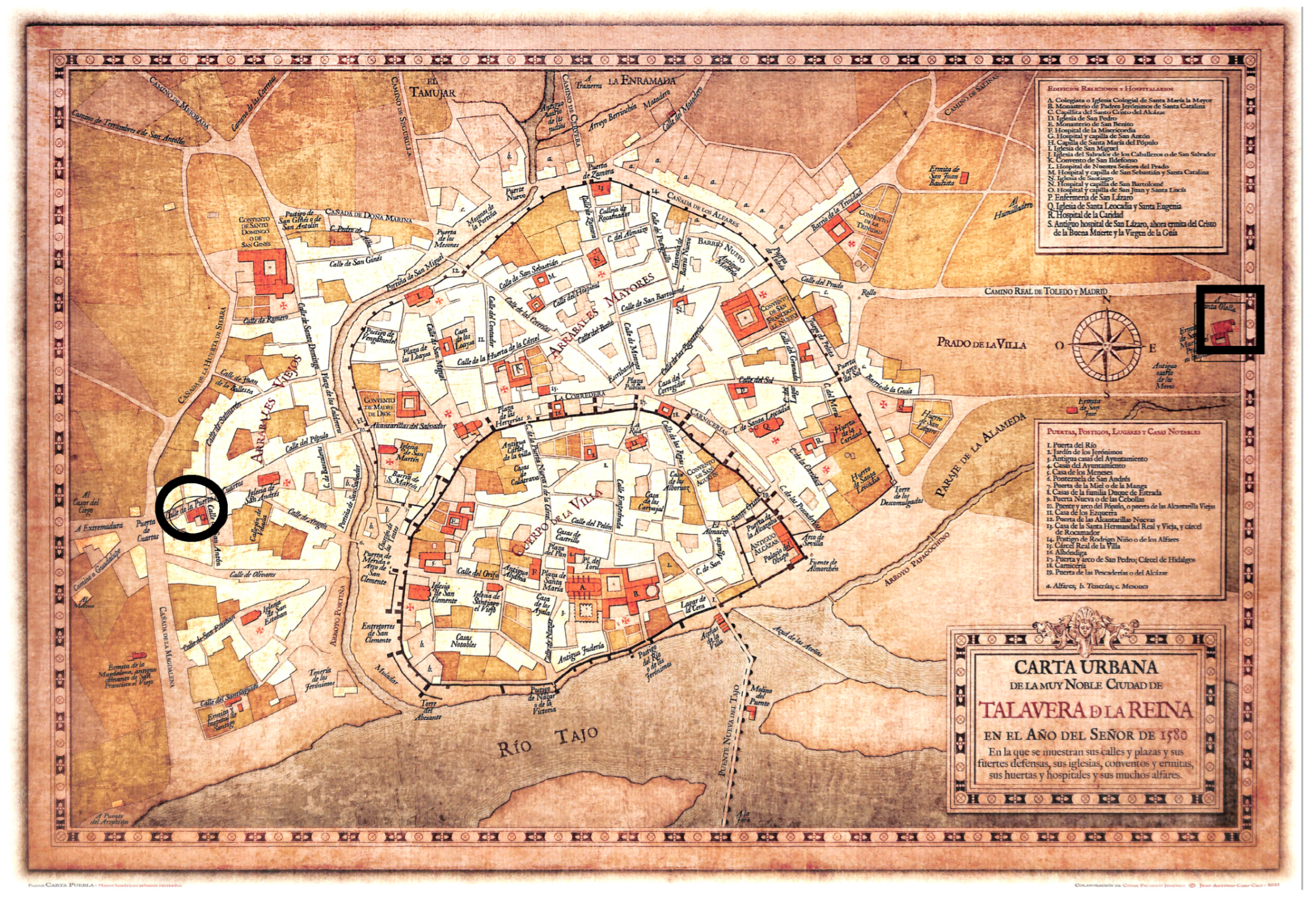

The origin of the current composition of the panel of Virgins and Tercios in front of Christ that we can see in the entrance portico of the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado, in Talavera de la Reina (Toledo, Spain), dates back to the 16th century, around 1570, and comes from the hospitable Church of San Antonio Abad, located outside the city walls (Figure 1). The Municipal Archive of Talavera de la Reina preserves an exceptional document, a description made in 1791, before the sale of its assets, which allows us to know what this church, which has now disappeared, was like:

‘La dicha Iglesia que pertenecía a la Encomienda de Sn. Antonio Abad se compone de una Nave con un Arco Toral que divide la Capilla Mayor, y el Frontispicio de esta se halla todo chapado de Azulejos de los Alfares de esta Villa, lo mismo el friso de ella, y de toda la Iglesia—El Púlpito con un Adorno encima—Otro adorno grande sobre el friso junto a la Tribuna, y en él colocada una Efigie de Sn. Agustín de madera, con unas cortinas viejas y otro más pequeño frente del Púlpito que representa Sn. Cristóbal; todo de dichos Azulejos; con una Pila para el Agua bendita de Piedra Berroqueña labrada inmediata al Púlpito y encima de ella una cruz de madera vieja y a los pies la Tribuna alta de madera con su celosía y Puerta de comunicación a la expresada Casa de la Encomienda; la cual Iglesia solo tiene una Puerta principal a la calle que va a la Puerta de Cuartos, mirando al aire cierzo, a el que hay un corto atrio […]’ [1].

Thanks to this document, we can get an idea of what this church looked like: a single nave with a transverse arch that served as a frontispiece, leading to the main chapel (altar), with a gallery at the foot, where there was also a door leading to the Houses of the Encomienda, another access door to the northeast (the street of Puerta de Cuartos, now the street of Padre Juan de Mariana) and an atrium. The description highlights the abundant and unique presence of tiles, covering the frontispiece of the main chapel and the frieze of the entire church [2], as well as forming an altarpiece dedicated to Saint Christopher [3]. To learn more about the tiles that decorated this church, we can turn to the historian Cosme Gómez de Tejada, who tells us that ‘esta iglesia [está] toda adornada (no es pequeña) de Azulejos así el cuerpo como la Capilla, y formando un retablo en el altar mayor que ocupa toda la frontera hasta lo alto, obra de primor, y que no sé que tenga semejante’ [4,5]; and, similarly, Pedro Antonio Policarpo García de Bores y la Guerra, who, based on Francisco de Soto’s account, points out that ‘junto a la puerta de Cuartos está la curiosa iglesia de S. Antonio Abad, en la cual reside, asistiendo a su servicio un comendador; hay custodia del Smo. Sacramento en este templo, que es muy capaz y todo adornado de azulejos así el cuerpo como la capilla y formado un retablo en el altar mayor que ocupa todo el frontis hasta lo alto; obra de primor y que no se tenga semejante’ [6]. However, of greater interest is the description provided by Ildefonso Fernández (1896) when the church had already been sold and demolished—though not yet the houses of the hospital-convent—and its tiles had been removed and relocated: ‘Tenía esta ermita una preciosíma (sic) colección de azulejos de alfar, que revestían sus paredes interiores, representando asuntos de la vida de San Antonio Abad, y que, como hemos dicho, el Ayuntamiento ha colocado dentro del crucero de Nuestra Señora del Prado. El edificio de la casa-hospitalaria subsiste todavía, y es el que cierra la calleja de San Antón. […] Los famosos azulejos de alfar de la desaparecida ermita de San Antón constaba de 16.000 piezas; se llevaron á la de Nuestra Señora del Prado unos seis ó siete mil; se colocaron próximamente 2.500; quedan en la Sacristía Vieja muy pocos más, sin contar algunos descabalados, y el resto se ha perdido, sin que sepamos cómo’ [7].

Some 16,000 tiles covered this church. Unfortunately, however, when the Order of Saint Anthony the Abbot was abolished by Pius VI with an Apostolic Brief in 1787 (published in Spain four years later), the property was expropriated and put up for sale, and the aforementioned inventory was made in 1791. Awaiting its final fate, the church remained as a chapel maintained by the Talavera Town Council, falling into a continuous process of neglect. For a time, the last commander of the Order of Saint Anthony the Abbot in Talavera, Pedro Sánchez Balberde [sic], acted as steward-custodian of the church, but in 1798, at the age of 70, ill and assisted by his sister, and lacking the income to support himself, he asked the Town Council to leave Talavera de la Reina to go and live with his nephew in his native land [8]. Juan García Peletero was appointed as the new custodian, acting as administrator of the chapel of San Antonio Abad, for which a sacristan was also appointed. In the early decades of the 19th century, this was Manuel del Prado, succeeded by his widow, Javiera Rojo, at least until 1831. The progressive ruin of the building began to affect the conservation of the tiles, as García Peletero attests in his accounts: ‘339 reales y once maravedíes invertidos en sentar cinco cuadros de azulejos, reparar la pared en que se han sentado y la de la espalda del coro, y limpiar los tejados de la Iglesia de S. Antonio Abad’ [9].

Finally, in the mid-19th century, the Church of San Antonio Abad was acquired by Trifón Monje, including its collection of tiles. The new owner saw the substantial business that could be made from selling these ‘biblical tile paintings’ and proceeded to remove them. However, this process was denounced by the historian and academic Luis Jiménez de la Llave, who brought it to the attention of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, the Talavera de la Reina City Council and the Provincial Governor of Toledo. This led to an investigation to clarify the ownership of the tiles and determine their best use. The file, opened ex officio by the Commission for Historical and Artistic Monuments of the Province of Toledo, contains the correspondence between these different institutions to ascertain whether the tiles were legally included in the sale of the church, which turned out to be true [10]. Once this had been ascertained, and in accordance with the legislation in force and the artistic merit of the tiles, it was proposed that one of these institutions should exercise its right of first refusal, reversing the sale that had been made to private individuals. Faced with the Provincial Governor’s refusal to cover the cost, on 28 August 1867, the Talavera de la Reina City Council agreed to acquire the tiles that made up the biblical scenes and were located in the Hermitage of San Antón [11]. From this point onwards, the gradual grubbing up began, using very rudimentary and damaging methods, and the storage of those six or seven thousand tiles, as Ildefonso Fernández told us. The City Council decided that their new destination should be the then Ermita del Prado, as it is a municipal building, and some 2500 tiles were initially installed there, in the transept, with the rest remaining in boxes in the sacristy or other rooms in the same building.

Figure 1.

Urban map of the city of Talavera de la Reina from 1580 (recreation). The black circle marks the location of the Church of San Antonio Abad, for which the tiles were made, and the black rectangle marks the location of the Basilica, where the tiles are currently located [12].

Figure 1.

Urban map of the city of Talavera de la Reina from 1580 (recreation). The black circle marks the location of the Church of San Antonio Abad, for which the tiles were made, and the black rectangle marks the location of the Basilica, where the tiles are currently located [12].

Around 1926, these other remaining tiles were partially installed in the portico of the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado, following years of repeated complaints by Luis Jiménez de la Llave (who died in 1905) to the City Council and controversy in the local and provincial press in the 1920s. The process was awarded to the ceramists Henche and Ruiz de Luna, who were tasked with producing the tiles needed to complete the new wainscoting [13]. Following Viollet-le-Duc’s criteria, the added pieces were completely mimetic, making them difficult to distinguish from the original 16th-century compositions. Unfortunately, those in charge of this process also faced a significant problem: there was no prior documentation for their installation, as this had not been carried out when they were removed from the Church of San Antonio Abad. Furthermore, the removal and cleaning work had been carried out by people who were not experts in the field, resulting in numerous original tiles being broken, fragmented and even lost, and after being stored in boxes for more than 60 years, no one could remember their original layout.

It is at this point when, using some of these tiles, which had been stored and collected in boxes, it was decided to create, among other things, the current tile panel depicting Virgins and Tercios before Christ in the portico of the Basilica. The absence of historical documentation attesting to the original composition of these panels and the lack of technical and scientific rigour in the treatment and placement of the tiles means that the final composition of the panel has compositional deficiencies. Therefore, the research we are discussing focuses on analysing this panel, generating a digital twin and developing a project proposal, with scientific methodology and intervention criteria, that will allow this panel to be completely recomposed, restoring the necessary pieces and differentiating what were surely two different compositions in origin: the procession of virgins with palms before Mary and the procession of the Tercios of Flanders in front of Christ.

Digital models in architectural heritage can be geometric models measured in situ or the representation of a hypothetical previous state through a scientific reconstruction process, as in the case of the Basilica of San Giovani in Conca in Milan [14]. In both cases, the digital model defines a data source that can be explored by both experts and tourists, with different levels of virtual interaction depending on the digital platform. The aim is to achieve not only a geometric model but also an informative or semantic model, enriched with information gathered from historical documentary sources [15].

2. Analysis of the Current Panel and Location of Original Parts: Data Processing

The methodology applied in the acquisition and subsequent processing of the data was structured in two phases: the first was fieldwork, consisting of on-site photogrammetric surveying using photogrammetric techniques, rectification and three-dimensional modelling; and the second, the office phase, in which the data was processed using photogrammetric rectification with the Asrix 2.0 programme and SfM photogrammetry with the Agisoft Metashape 2.0 Professional programme, resulting in an orthoimage of the panel (Figure 2). A Canon EOS 700D camera was used with ISO 100, aperture f/8-f/11 on a tripod with mixed lighting and colour correction performed with ColorChecker classic and processed with Lightroom Classic, with images taken in January 2024.

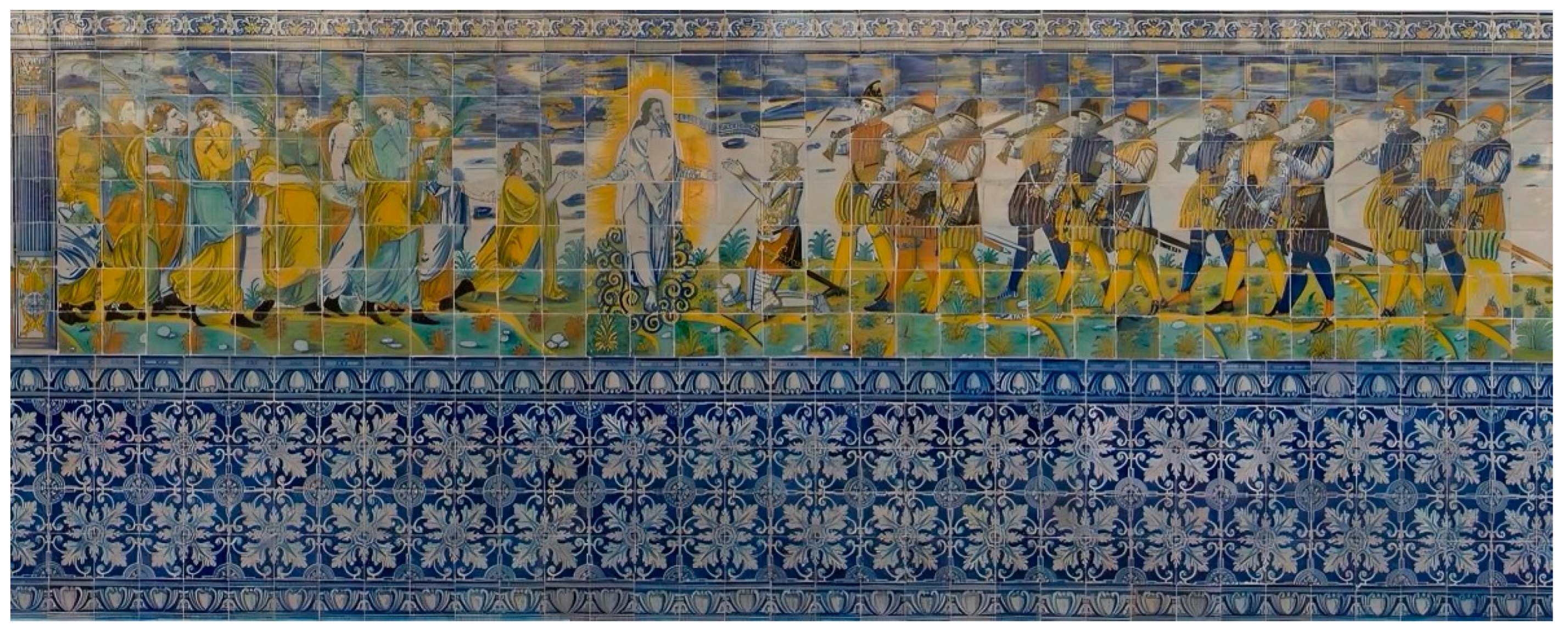

Figure 2.

General and current view of the tile wainscot located in the portico of the Basilica, to the left of the entrance door, rectified using photogrammetry.

The lighting came from two sources: on the one hand, natural light and, on the other, electric lighting, which combined different temperatures and systems in order to reduce glare, which behaves better on pavements that are more nuanced by wear and tear [16] than on baseboards, so the angle to the object had to be selected in order to mitigate surface glare.

The panel that is now the focus of our attention, currently located on the left side of the portico of the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado (Figure 2), consists of 238 tiles arranged in seven rows and thirty-four columns; as Talavera tiles measure 14 × 14 cm1, arranged in a matrix of 7 rows by 34 columns, forming a rectangle measuring 0.98 × 4.76 metres, giving a total surface area of approximately 4.66 m2. Christ is positioned in the centre, in a halo of glory, with virgins processing towards him from the left and soldiers from the tercios (pikemen and arquebusiers) from the right.

The procession of virgins begins with one of them kneeling, followed by two groups of four virgins with palms (Figure 3). As for the soldiers, the first appears kneeling in front of Christ and the rest in four groups of three wearing period clothing and carrying arquebuses or pikes on their shoulders.

Figure 3.

Detail of the tile wainscot, currently located in the portico of the Basilica, rectified using photogrammetry, depicting the Procession of Virgins with palms before Mary.

A basic visual inspection reveals the multiple assembly problems presented by this panel, making it clear that when this wainscot was relocated to this space, the missing or broken tiles were replaced with others of similar design or colour. Thus, we can see ‘collage’ figures in which the logic of their design or the continuity of the drawing is not maintained. For example, we see soldiers wearing shoes of different colours, while the Greguesque breeches (gregüescos) should be the same colour as the stockings, and the arquebuses are strangely fused with pikes (Figure 4). On the other hand, it is clear that this frieze was originally two different compositions following a representative tradition common in art history, according to which there should be a procession of virgins marching towards the Virgin Mary and, on the other hand, a procession of soldiers or milites christi marching towards Christ [17].

Figure 4.

Detail of the tile wainscot, currently located in the portico of the Basilica, rectified using photogrammetry, depicting the Procession of the Tercios of Flanders in front of Christ.

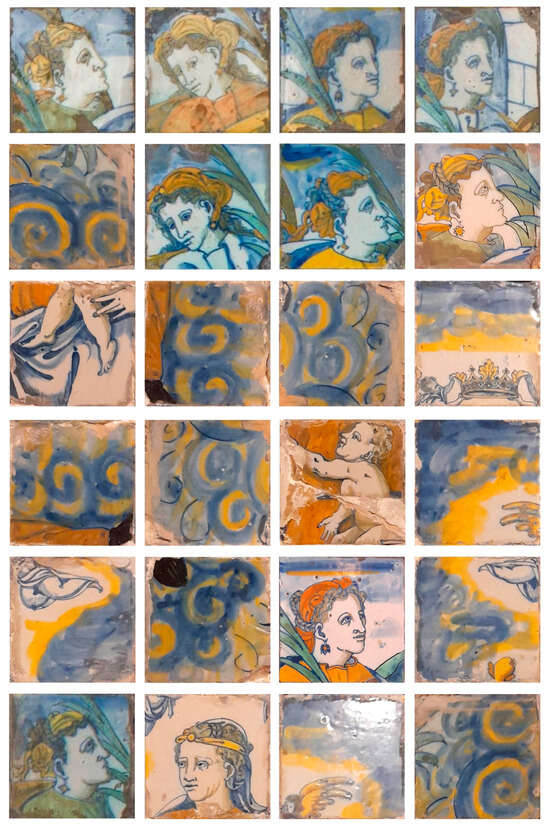

Other tiles currently located in the hallway and office of the rector of the Basilica itself have also been documented using photogrammetry, as well as other altarpiece compositions located in different parts of the Basilica that also feature pieces from these processions (Figure 5). These are ‘leftover’ tiles from the relocation process carried out around 1926 and with no particular order. Among these tiles, there are elements that clearly belonged originally to this wainscot of the Tercios ante Cristo, with parts of soldiers and, as a great novelty, musicians and a standard-bearer, a total of 28 pieces that may belong to this original composition (Figure 6).

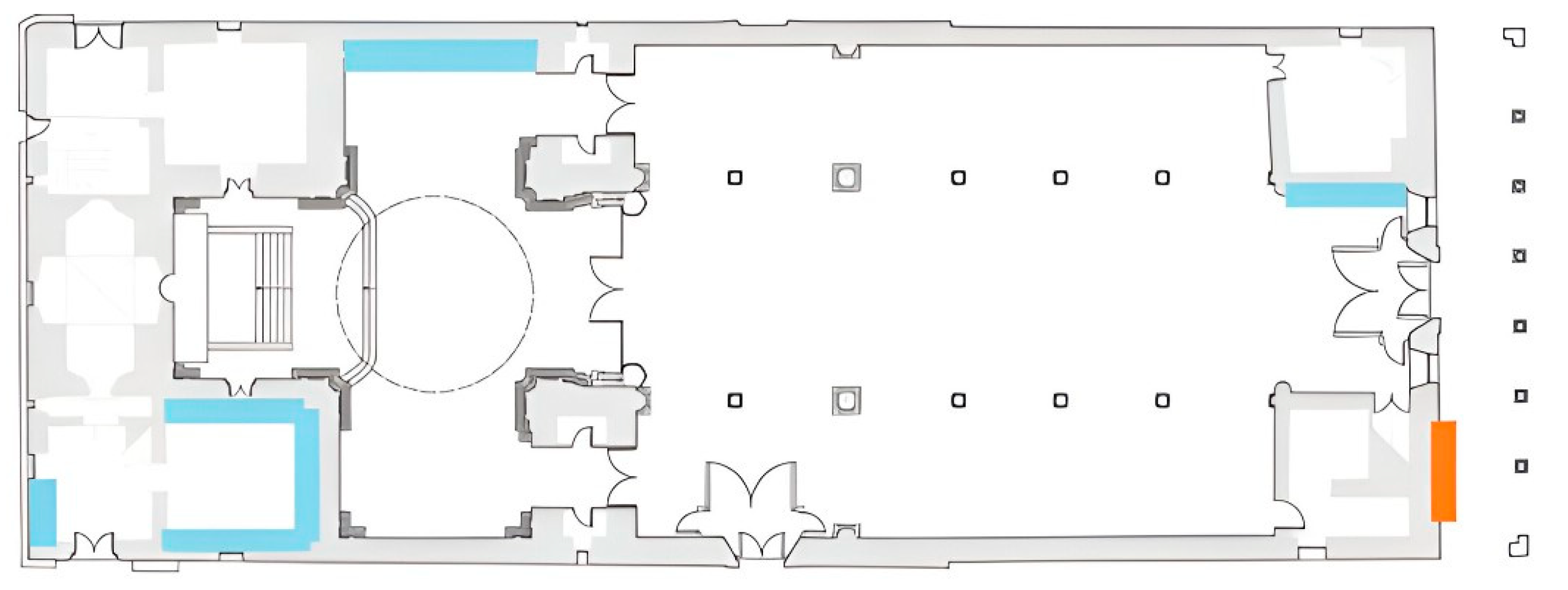

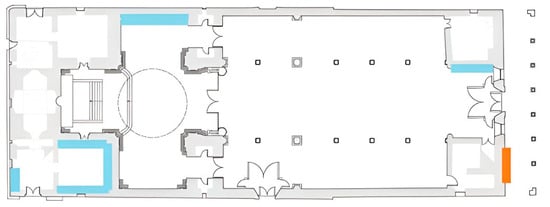

Figure 5.

Floor plan of the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado, showing in red the position of the current wainscot and in blue the locations from which pieces such as the Virgin and other soldiers and virgins from both processions have been used.

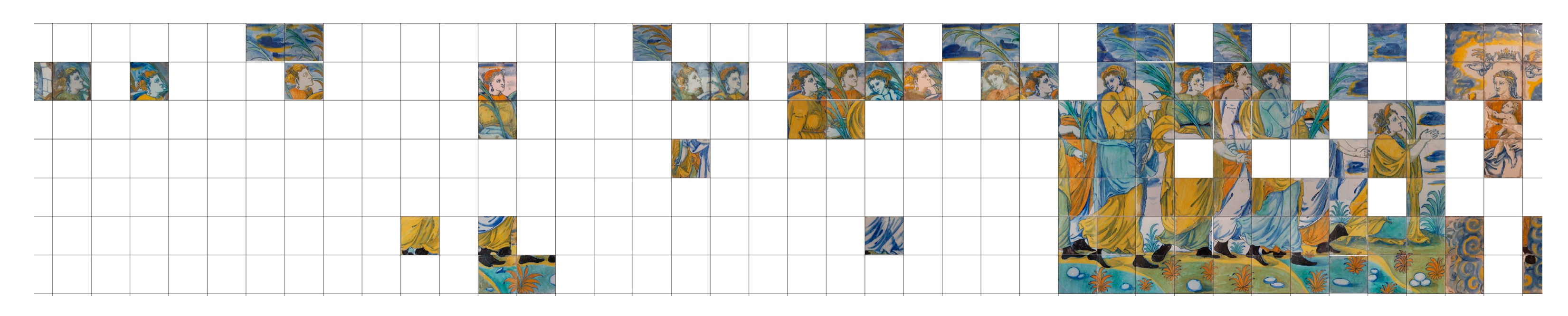

Figure 6.

Several pieces have been found relocated in different rooms of the Basilica that could belong to the panel of the Tercios of Flanders before Christ.

Similarly, other pieces have been found that could belong to the Procession of the Virgins, including those that would form the Virgin Mary herself, to whom the procession is directed, surrounded by a cloud, with her son in her arms and crowned by angels (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Various tiles found in the interior rooms of the Basilica, which may have been part of the panel depicting the Procession of Virgins with Palms in front of Mary.

3. Proposal for Tile Reintegration: Methodology and Criteria for Intervention to Restore the Expressive Value of the Artwork

Once the current layout of the panel depicting the Procession of Virgins and Tercios in front of Christ has been analysed, its compositional deficiencies identified, and original tiles located in various rooms of the Basilica that most likely belong to each of the two different compositions that were removed from the former church of San Antonio Abad and eventually ended up in this portico, a methodology and criteria for intervention can be proposed for the recomposition and reintegration of elements that will allow for a correct interpretation and vision of these compositions, thus recovering the expressive and artistic value of this panel.

In any case, we must bear in mind that the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado is protected as a Site of Cultural Interest [18] and Talavera-style ceramics have been declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (2019) [19]. Therefore, the starting point for the proposal to reintegrate the original tiles and possibly create new tiles that allow for the recomposition and correct historical and sociocultural interpretation of this panel, as well as the reintegration and conservation of its artistic value, must be in compliance with the Cultural Heritage Law of Castilla-La Mancha [20] and international recommendations on the protection of cultural property. Therefore, among the criteria for intervention, priority should be given to the replacement of original pieces, the principle of differentiation and subtle identification of the reintegration of missing parts in the original tiles (formally and/or chromatically) or the creation of new pieces that are discernible from the originals (perceptible but discreet, non-invasive differentiation), as well as the recovery of formal, aesthetic and stylistic unity for the sake of correct interpretation, appreciation and enjoyment of this panel by the public.

Furthermore, the damage and deterioration commonly found in historic tiles in architectural heritage sites are directly related to problems/pathologies associated with moisture and salt deterioration in the building itself. For this reason, the 1987 Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Art and Cultural Objects, in its Annex D. General warnings for the return of restored works to their original location, states that ‘if the intervention has been motivated by the thermo-hygrometric conditions of the place in general, or of the walls in particular […] as an absolute rule of conduct, the restored work should never be returned to its original location if it has not been properly cleaned up’. Therefore, when we have a church, as in our case, with tile-covered baseboards and the presence of capillary rising damp, it is advisable to dismantle the baseboard, clean and restore the damaged pieces and replace them, but not directly on the walls, rather on Eurolan (or polycarbonate) panels anchored to the wall with stainless steel frames and separated a few centimetres from the wall and the floor to allow ventilation and prevent condensation, thus protecting the pieces from capillary rising damp. In cases where there is a high level of moisture, this intervention technique should be complemented by the installation of a non-invasive system such as wireless electro-osmosis [21].

In our case, we have original tiles to be removed from the panel itself (as they do not correspond to either of the two processions depicted), and from rooms in the Basilica (the entrance hall and the rector’s office) that do correspond to the ‘Procession of the Tercios of Flanders before Christ’ or the ‘Procession of Virgins with Palms before Mary’. Therefore, once the pieces to be removed have been located and identified, they will be protected with a coating and carefully extracted so as not to cause further damage. Once in the workshop, they will be cleaned manually with soft brushes, soluble salts (if any) will be removed, and formal and chromatic reintegration of gaps or missing parts will be carried out. In this case, for the reintegration of gaps in historic glazed tiles, there are several intervention criteria that we could summarise as follows: the technique of ne rian faire (do nothing, the piece remains with the gap), recomposition with neutral ink (filling with mortar of a single colour, which is usually white but could be a softer shade than the original), reintegration by linear or formal approximation (completed with a schematic drawing on a light-coloured filling that helps to ‘understand’ the original piece in its entirety), systems of reintegration of form and colour (selection of colour and ‘tratteggio’ or reintegration with uniform coloured scratching), ‘reglatino’ (very fine, continuous and dense hatching, similar to tapestry weaving, in the same colour or slightly lighter than the original drawing), stippling (a dense accumulation of small dots in the same colour as the original drawing), non-discernible reintegration (very difficult to identify, so this technique should be ruled out), ex novos (new pieces, with slightly softer colours than the original pieces for identification purposes), or the low level technique (the filling surface is at a slightly lower level than the original for identification purposes) [22].

Taking into account the formal and chromatic characteristics, the size of the current panel and the digital twin that is to be created, as well as the need to ensure that the two processions currently represented on the portico of the Basilica can be correctly read and appreciated, the proposed intervention criterion is formal and chromatic reintegration by stippling, especially in the case of small gaps in the material, and/or reintegration by reglatino, as this is the most accepted method and, therefore, the one most used by specialists. The reglatino technique has prevailed over other techniques for the selective reintegration of gaps in historic tiles, especially when we have large surfaces where the missing part must be formally and chromatically recomposed for a correct overall view, and, in particular, when it is a devotional tile composition, such as the panel on the portico of the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado. In the case of creating new pieces to help ‘complete and show’ the artistry of the two compositions, which were originally independent but now form the panel of Virgins and Tercios de Cristo on the portico of the Basilica, these new tiles should be based on accurate graphic documentation and knowledge of the original work. In the case of the ‘Procession of the Tercios of Flanders in front of Christ’, for a virtual (digital twin) or even real reconstruction, the group of musicians and standard bearers found in the vestry of the Church of Santa María in Piedraescrita (Robledo del Mazo, Toledo) could be taken as a reference, as will be discussed in the following section.

4. Results

The working hypothesis is that this altarpiece was originally two different, larger processions. We base this on the existence of similar compositions from the same period, such as the tile wainscots in the Church of Santa María in Piedraescrita (Robledo del Mazo, Toledo). The entire collection of tiles in this church, made in the potteries of Talavera de la Reina at the beginning of the 17th century, and therefore slightly later than the one we are studying, has been recently restored (it was unveiled in 2021), which has allowed for the replacement of some 680 tiles that were still stored in boxes at the top of the church itself. Of this entire collection, we are interested in the procession of the Virgins (unfortunately, the image of the Virgin is badly damaged) and the procession of the Tercios of Flanders, which appear as separate friezes. Taking these panels into account, it has been hypothesised that the wainscoting of the portico of the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado would be two different and independent processions that could run parallel when they were in the Church of San Antonio Abad. On the Epistle side, to the South, there would be the ‘Procession of the Tercios of Flanders in front of Christ’, and on the Gospel side, on the North wall, the ‘Procession of Virgins with Palms in front of Mary’. Both compositions would thus be oriented towards the altar of the same church. This hypothesis has been supported by the discovery of the aforementioned ‘leftover’ tiles, which has led us to virtually incorporate these original pieces that may belong to these two panels. This allows us to develop a more complete hypothesis that is closer to the original.

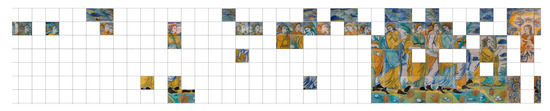

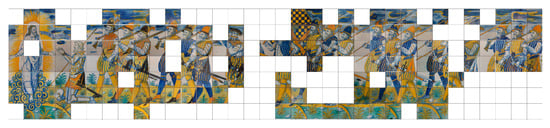

On the one hand, regarding the procession of the virgins, we must bear in mind that just among the tiles rearranged in the office-sacristy of the Basilica, above the chest of drawers, we have been able to locate up to eight heads that clearly correspond to these, as well as other misplaced on a panel depicting the life of Saint Anthony the Abbot at the foot of the Basilica. In total, there are at least nine more figures, one of which also indicates that this procession left from a kind of chapel or architectural structure. However, although we have only located nine heads, the groups of virgins comprise four figures, so we must assume that there were at least twelve others (three groups of four). Establishing the correct location of the new tiles that we have located is quite complex, as they are so scarce and we cannot be guided by the continuity of the design. We can barely identify the continuity between one figure and another, as there are too many ‘gaps’. For the proposed hypothesis, the first step was to remove the misplaced pieces from the current wainscoting. From there, we were able to study the logic behind the design of these virgins, whose variety and diversity is apparent. In reality, there are only three types of ‘virgin’ and, in each group of four, one of the types is repeated (at the ends). We have established a model: A) Virgin looking forward and extending her arm; B) Virgin with her head turned back and pointing with one hand towards the front; and C) Virgin in profile with her head slightly raised. The first group follows the sequence A-B-C-A and the second, B-A-C-B. Each group is limited to four columns of tiles, and between each of them there is a column of tiles with a landscape. In addition, to break up the monotony of the figures, their position varies between the foreground and background. In the first group, the first Virgin is in the background, the second in the foreground, the third in the background and the fourth in the foreground; in the second group, the order is reversed, and so on. All this has allowed us to establish a design logic on which to base our minimum hypothesis, although, as already mentioned, it still raises some conflicting details. Taking this ‘logic’ into account, we have distributed the heads found, three from model A, two from B and four from C. The result is shown in Figure 8, in which the twelve tiles located have also been repositioned. Nine of a total of twenty-one are missing from the image of the Virgin and Child. The continuity between the kneeling virgin and the Virgin Mary is absolutely certain due to the continuity of the drawing. We can therefore assume that the original panel had a minimum of twenty-eight virgins in seven groups of four, plus the kneeling one, plus the Virgin and Child (Figure 8), which would form 40 columns with a length of 5.60 metres. We would be talking about a panel of 280 tiles, of which seventy-three are now in the portico (eleven have been removed because their location is difficult to determine) and twenty-two are inside the Basilica; we have therefore been able to replace only ninety-five tiles, and 185 are lost.

Figure 8.

Hypothesis for the reconstruction of the lower part of the Procession of the Virgins with Palms before Mary. To obtain an overview of the panel and restore its ‘expressive value’, the missing areas would be reintegrated according to the methodology and criteria set out in this text.

On the other hand, if it was similar in size to the panel depicting the soldiers, it would have been a wall panel with eight groups of women and the kneeling figure in front of the Virgin Mary crowned by angels; thirty-three members in total in the procession, which would have been made up of 45 columns measuring 6.30 metres in length. However, this maximum cannot be justified in the absence of the tiles that would support this hypothesis. Furthermore, it should be borne in mind that we lack certain information regarding the original space in which this panel was placed. We know that there was an entrance door to the church on the north wall, where this wall panel would have been located, and therefore it is reasonable to assume that it had a smaller space than its counterpart on the south wall. However, for the moment we can only speculate.

On the other hand, in the other panel, we can currently see four groups of three soldiers each: the first group carries arquebuses, the second and third carry arquebuses strangely mixed with pikes, and the fourth carries pikes (Figure 4). The painter followed a similar model of soldier, establishing slight variations in drawing and colour to give variety to the whole composition. Thanks to this, it is easy to detect the current continuity errors, as there is a basic sequence of three soldiers (each in a column of tiles) and an intermediate space between each group (a column of tiles); the arquebuses or pikes give an idea of the connection between the figures.

Taking these ‘logics’ into account, we can arrive at different hypotheses for relocation; once again, one of minimums and one of maximums. The minimal hypothesis is based on the tiles that have been preserved, both those in their current position on the wainscoting and those that have been relocated to the rector’s office in the Basilica. In total, we have been able to locate thirty tiles, among which the appearance of two musicians (with a fife and a drum) and a standard-bearer stands out [23]. In addition, other original tiles from this procession have been reintegrated into other panels in the Basilica; for example, in the panel of the virgins. If we strictly adhere to the continuity of the design and colour and the logic of the composition, we could obtain a wainscot that would go from 22 columns to 34 columns (204 tiles). However, of those 204 tiles, we can only reliably replace 122, leaving us with 82 missing. This would leave a sequence consisting of Christ, the kneeling soldier with a pike, two groups of three arquebusiers each, the two musicians and the standard-bearer, three groups of three pikemen each, and a final group of three arquebusiers (22 soldiers in total) (Figure 9), with a length of 4.76 metres. It is possible that this parade was larger, as there are still tiles left over that tell us about more figures, which leads us to propose another maximum hypothesis.

Figure 9.

Hypothesis for the reconstruction of the lower part of the Tercios of Flanders in front of Christ. In order to obtain an overview of the panel and restore its ‘expressive value’, the missing areas would be reintegrated according to the methodology and criteria set out in this text.

The second hypothesis leads us to propose a composition with two initial groups carrying arquebuses, followed by the fife player, the drummer and the standard bearer of the Tercios of Flanders, and behind them another six groups of soldiers, the first three carrying pikes and the last three carrying firearms. The length of this second hypothesis would be 45 columns, reaching a length of 6.30 metres, with a total of 315 tiles, as there are 7 rows. We emphasise the hypothetical nature of this second option, as we have not yet located enough tiles or clarified the space they originally occupied in the Church of San Antonio Abad.

5. Discussion

The construction of a geometric model is a four-step process: data acquisition, pre-processing, parameter estimation, and modelling.

In parameter estimation, in the case at hand, the data are not easily accessible, as they cannot be seen and therefore would have to be simulated. We create a hypothetical model, adjust it to the incomplete input data, and then use the model to simulate the missing data [24]. However, in our case, it is not a matter of interpolating and completing the model with an interpolated parametric surface that fits all the known points. In our case, the restrictions or constraints come from the image or figurative scene it represents, which would have to be completed by creating the missing elements to reconstruct the original model if those elements are not found. This recomposition can be done digitally and can also be carried out in reality, requesting a potter to make these unique and complex pieces, recommending the technique of formal and chromatic reintegration of gaps or missing parts by stippling.

Following the photogrammetric analysis, historical-constructive research into the two processions, together with the minimum and maximum hypotheses proposed, it is necessary to incorporate alphanumeric information in order to obtain the informative or semantic model, which will allow us to trace the path each piece has followed over time. To do this, it is necessary to incorporate the location of each piece for each selected date. The temporal selection would be at least three key moments: the 16th century, when they were in the church for which they were designed; the 19th century, when they were moved and stored in boxes; and the 20th century, when they were placed where they are now. Two additional locations would also be included, corresponding to the two hypotheses that have been proposed. More historical information could also be included for each piece, such as its state of conservation, the pottery where it was made, its colours, or any peculiarities it may have, making this information available and accessible.

All of this will generate a digital twin, with the possibility of tracking the position of each piece throughout five centuries of history. In addition to these two processions, the processions of the Virgin and the Tercios would be used as interior textures in the virtual 3D reconstruction of the church that originally housed them, thus becoming a tool for dissemination and increasing visits to the current temple [25]. The historical-archaeological evidence scale should be applied to ensure the rigour of interdisciplinary research [26].

Likewise, using scientific methodology and appropriate intervention criteria, we have detailed how to completely restore this panel by replacing all the necessary pieces, recommending the technique of formal and chromatic reintegration of gaps or missing parts by stippling, especially in the case of small gaps, and/or reglatino. As Cesare Brandi argued, we believe that the fundamental objective of monumental restoration is to ‘reintegrate and preserve the expressive value of the work of art’, so that not only must the historical document, the panel of historical tiles, be secured/preserved, but the work of art, its entity and artistic nature, its artistry, must also be recovered. Furthermore, this example should serve as a basis for proposing an intervention on the rest of the panels and altarpieces in the Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Prado that present the same problem of damage and incorrect arrangement of pieces. All this with a view to their correct conservation, historical and sociocultural interpretation, and dissemination to the public.

Author Contributions

All authors have jointly contributed to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/and by FEDER A Way to Build Europe, Project PID2022-139696NB-I00 ‘Interactive and intelligent digital twin for the documentation, analysis and dissemination of the tiles of the Basilica del Prado in Talavera de la Reina’ and by the EU through the ERDF and by the JCCM through INNOCAM with the project SBPLY/23/180225/000074 ‘The tiles of the Basilica del Prado in Talavera de la Reina: an interactive and intelligent digital twin for their documentation, analysis and dissemination’.

Data Availability Statement

The research data will be shared in an open repository when the project is completed. In the meantime, the dataset is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | The old Sevillian tile and the Valencian tile from Manises have a size of 15 × 15 cm. |

References

- Extinción de la Orden Hospitalaria de Sn. Antonio Abad y Ocupación de sus Bienes y Rentas en los Dominios de España; Archivo Municipal de Talavera de la Reina: Talavera de la Reina, Spain, 1791.

- It is probably the exterior part of what is now known as the altarpiece of Saint Anthony, in the crossing of the Basilica de Nuestra Señora del Prado in Talavera de la Reina.

- Preserved, with assembly errors, at the foot of the Basílica de Ntra. Sra. del Prado.

- Gómez de Tejada, C. Historia de Talavera de la Reina; 1648.

- Vaca, D.; de Luna, J.R. Historia de la Cerámica de Talavera de la Reina y algunos datos sobre el Puente del Arzobispo; Editora Nacional: Madrid, España, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Policarpo García de Bores y la Guerra, P.A.; de Soto, F. Historia de la Antiquíssima Ciudad y Colonia Romana Élbora de la Carpetania hoy Talavera de la Reyna, Dividida en Tres Libros; 1767; pp. 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández y Sánchez, I. Historia de Talavera de la Reina; Talavera de la Reina; Luis Rubalcaba: Talavera de la Reina, Spain, 1896; pp. 284–445. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Servicios Sociales. Escrito de 6 de Agosto de 1798; Archivo Municipal de Talavera de la Reina: Talavera de la Reina, Spain, 1798. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Servicios Sociales. Escrito de 5 de Agosto de 1815; Archivo Municipal de Talavera de la Reina: Talavera de la Reina, Spain, 1815. [Google Scholar]

- Archivo Municipal de Talavera de la Reina. Expediente Sign. 53-1/2 del Archivo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando; Archivo Municipal de Talavera de la Reina: Toledo, Spain, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Archivo Municipal de Talavera de la Reina. Libro de Acuerdos Municipales del Ayuntamiento de Talavera de la Reina; Archivo Municipal de Talavera de la Reina: Toledo, Spain, 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, C.; Caro, J.A. Maps Carta Puebla, 2021.

- “Vida Municipal”, El Castellano; XXII; 23 December 1926.

- Guidi, G.; Russo, M. Reality-Based and Reconstructive models: Digital Media for Cultural Heritage Valorization. SCIRES-IT-Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2011, 1, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallavollita, F.; Foschi, R.; Apollonio, F.I.; Cazzaro, I. Terminological Study for Scientific Hypothetical 3D Reconstruction. Heritage 2024, 7, 4755–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Piqueras, T.; Ruggieri, A.; Rodriguez-Navarro, P. Advanced surveying techniques for the rehabilitation and enhancement of historic residential architecture: The case of Villa Amparo. Graphic thinking. In Proceedings of the XVII International Conference on Graphic Expression Applied to Building—Apega Cartagena 2025, Cartagena, Spain, 2–4 October 2025; pp. 1000–1010. [Google Scholar]

- A la procesión de vírgenes corresponden las doce primeras columnas de azulejos (84), mientras que a la de soldados las 22 siguientes (154 azulejos).

- Consejería de Educación y Cultura. Decreto 61/1993, de 11 de Mayo, Por el Que se Declara Bien de Interés Cultural, Con la Categoría de Monumento el Inmueble Correspondiente a la Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Prado en Talavera de la Reina (Toledo); Consejería de Educación y Cultura: Toledo, Spain, 2 June 1993; pp. 2963–2965. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Secretariat. Artisanal production of Talavera-style ceramics from Talavera de la Reina and Puente del Arzobispo (Spain) to be Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In Proceedings of the 14th Intergovernmental Committee of UNESCO, Bogotá, Colombia, 11 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ley 4/2013, de 16 de mayo, de Patrimonio Cultural de Castilla-La Mancha. (DOCM n.º 100, de 24 mayo de 2013. BOE n.º 240, de 7 octubre 2013).

- Como ejemplo de esta propuesta de intervención en zócalos con azulejería vidriada histórica recomendamos la visita a la iglesia de San Juan de la Cruz, en la ciudad de Valencia.

- Gironés Sarrió, I.; Guerola Blay, V. La pintura cerámica valenciana y sus sistemas de reintegración a través de la metodología documental, gráfica y escrita. Ge-Conservación 2021, 20, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The standard, reminiscent of that of Spínola's tercios, displays a blue and yellow checkered background with the Cross of Saint Andrew (rather than the Cross of Burgundy). If it is indeed a reference to that standard, the chronology of these banners would have to be reconsidered, as their use dates back to around 1620. This group of musicians and standard-bearer can also be found at the altar of the Church of Santa María in Piedraescrita, a hamlet in the municipality of Robledo del Mazo (Toledo).

- Barceló, J.A. Virtual Reality and Scientific Visualization: Working with Models and Hypotheses. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2001, 12, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Alcaide, M.; Román Punzón, J.M.; Valdivia García, M. Application of digital technologies for virtual reconstruction of the roman villa of Salar (Granada, Spain): Sn example of archaeological heritage transfer. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2025, 16, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Resco, P.; García Álvarez-Busto, A.; Muñiz-López, I.; Fernández-Calderón, N. Reconstrucción virtual en 3D del castillo de Gauzón (Castrillón, Principado de Asturias). Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2021, 12, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.