Abstract

This paper examines interpretations of depopulation in Norse Greenland between the 14th and 15th centuries CE. Using in-depth interviews with 13 experts working on the environmental, social and economic dimensions of settlement and depopulation in Norse Greenland, we examine the different interpretations of decline by experts using the same data. Our analysis reveals a geographical and disciplinary pattern of interpretation that reflects the institutional and disciplinary cultures, successive paradigms, and placed ideas about human–environment interaction. We examine the interplay between data and interpretation to uncover key developments in knowledge of the past and ideas about both the role of climate, ecology and social, economic and political processes in the end of the Norse settlement in Greenland, as well as their wider persistence in the North Atlantic region. In particular, we emphasise the importance of active reflection on disciplinary training, schools of thought, and national narratives in both the interpretation and perceived relevance of the past.

1. Introduction

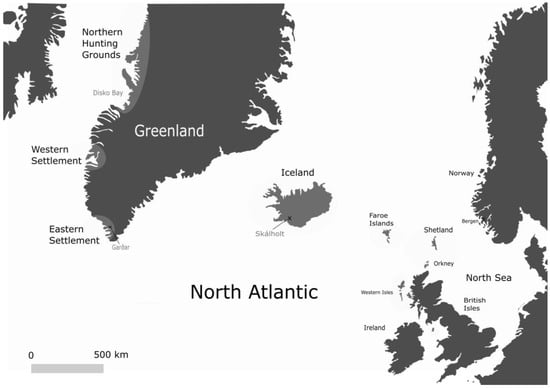

This paper examines narratives of settlement decline in Medieval Norse Greenland during the conjuncture of climatic fluctuations of the Little Ice Age, European political economic changes and cultural contact with the Inuit in the 14th and 15th centuries. Using a comparative analysis of interviews with academic researchers working on the disappearance of the Norse in the 15th century, we assess the different interpretations of decline by experts using the same data. The Norse settled southwest Greenland in the late-10th century CE, following expansion from Scandinavia and occupation of parts of Ireland, the British Isles and the Low Countries, and the establishment of permanent settlements on the Faroe Islands and Iceland (Figure 1). This Norse diaspora spanned the 8th to 15th centuries CE, starting with the outward movement from West Norway in search of new opportunities [] most likely by young enterprising groups in search of land for settlement [], and ended in the 15th century with the unrecorded end of settlement in Greenland [,,].

Figure 1.

North Atlantic islands, showing Norse settlement areas in grey, including church farms in Greenland (Garðar) and Iceland (Skálholt). Map the authors own and produced in Inkscape v1.4.

Climate change, environmental degradation, political economic changes and cultural contact with the Inuit have been argued to play a key role in the ultimate fate of Norse Greenland (e.g., [,,]), although each of these explanations are disputed (e.g., [,,]). It is not our intention to identify the most convincing explanation for the end of Norse Greenland, but rather to examine how researchers with access to the same evidence arrive at different conclusions. To understand the relationship between “evidence” and “reasoning” in these narratives, we build upon recent knowledge production debates in archaeological theory together with a geography of science perspective. In so doing, we focus on how interviewees articulate their narratives—using a combination of data, method and theory—and what influence geographical context (situated knowledge), discipline and research traditions have on interpretation and thus the production of knowledge of the past. Our overall aim is to understand how thought processes operating in the present produce multiple different knowledges of the past, and particularly the articulation of social, environmental and climatic determinants of the disappearance of the Norse.

1.1. Context: The Decline of Norse Greenland

Feature articles in scientific magazines and the wider media often draw attention to different explanations of the “mystery” surrounding the fate of the Norse settlers in Greenland (e.g., [,,]). Various theories are proposed—often depending on their correspondence with academics who study the North Atlantic—including climate variability, environmental degradation, economic and political changes in Europe, or conflict with the Inuit [,]. What was changing in the late medieval period? And what impacts can be connected with the end of settlement in Greenland? These are questions taken up in academic research, focusing primarily on the relationship between impacts, adaptation and vulnerability [,,,,,]. But although it is known that settlement came to an end and there is significant evidence for changes to subsistence, trade, climate variability, how this evidence should be interpreted remains less clear and is largely unresolved in the literature []. Multiple different explanations have been provided between the 18th century and present day, explaining the disappearance of the Norse in the 15th or 16th centuries. Such explanations have ranged from socio-cultural factors, such as conflict with pirates and the Inuit, and political-economic shifts, like declining trade links with Europe causing isolation, to a more recent proposals that environmental factors, including the decline of the subsistence system causing the end of the settlement [,,]. There are two important points to distinguish regarding the interpretation of the late settlement period in Norse Greenland: first, the interpretation of different types of evidence (i.e., historical sources, archaeological materials or ecological and climatic records), and second, the weighting of this evidence—how it is articulated or ‘cabled’ as Chapman and Wylie [] have put it—in reasoning about different causes of depopulation.

In Arneborg’s (2015) review of evidence for Norse “abandonment” of the eastern settlement, she builds her argument on a publication by Dugmore and co-authors []. As Arneborg proposes, “it has been argued (Dugmore et al., 2012) that abandonment should be explained by a combination of external factors (climate changes; changes in European trade systems).” ([]: 257 [emphasis added]). Whilst this publication attributes external factors (i.e., climate change and political-economic change in Europe) to the end of Norse settlement in Greenland, not all the co-authors adhere to a single narrative in previous or subsequent publications. Clearly, ideas evolve and there are circumstances when quite different interpretations can diverge or intersect in terms of both substance and emphasis. To illustrate this point, the co-authors of Dugmore et al. [] can be divided into separate groups based their publication history. In an earlier work by Dugmore, McGovern and Keller [], climate change, trade and hostilities with the Thule [Inuit] culture are reasoned to be responsible for “social collapse” caused by a failure of communal provisioning, followed by subsistence crisis and starvation. Arneborg in 2008 and 2015, and Vésteinsson writing in 2009, argue, conversely, that there is limited evidence that communal provisioning was stressed in the final years of settlement. Their argument rests on the assumption that cultural and economic isolation from the rest of Medieval Europe was responsible for the abandonment of a comparatively “poor” quality of life “irrespective of how much could be put on the tables” ([]: 149). Lynnerup, writing in 2011, provides a similar narrative, arguing that evidence of church-building at the end of settlement should be interpreted as a symbolic attempt to create unity at a time of crisis and decline [] and that there is little evidence to suggest the Norse starved to death [].

While a broad consensus exists about the processes driving the end of settlement—including evidence of social inequality, subsistence adaptation strategies and eventual cultural limits to adaptation—there is no consensus about the fate of the Norse settlers themselves [,,,,]. Notable is the lack of analysis and debate within the literature about the ways the evidence for the end of settlement is interpreted. Within the published literature, there is little evaluation of the reasoning as to why famine or abandonment occurred and little discussion between the proponents of these hypotheses about why ideas may be mutually inconsistent, intersect or change. Some authors appear on papers that apparently contradict their existing hypothesis, and though interpretations may change, differences in hypothesis and interpretation can be lost in multi-authored articles or lack clarity on how and why interpretations have changed—for example, owing to new evidence or applications of different forms of theory and method. Interviews with active scholars working in the field (see Section 3) show this variation in interpretation, with some participants advocated “famine” and “extinction” of settlement, but the same participants contribute to publications suggesting that depopulation was the result of abandonment [,]. Hence, while a broad consensus that the Norse settlements ended because of the impacts of climate variability and economic change in, and isolation from, Europe, how—by way of interpretation of evidence—Greenland came to be depopulated in the late-14th and early-15th centuries CE remains unclear.

Interpretations based on variably detailed, partial and incomplete evidence from a range of environmental and cultural sources are clearly evolving, diverging or converging, with shifting emphasis on overarching drivers of change. Hence, this analysis sheds important light on the role of interpretation and reasoning with data within the process of knowledge production of the past. We argue this has a potentially crucial role in understanding archaeological and environmental records in the final phases of Norse settlement, including interpretation of limits and barriers to adaptation.

1.2. Environment and Archaeology in the North Atlantic

A major research theme in Medieval Greenland and the wider North Atlantic has been to understand human–environment interaction through the theoretical and disciplinary frames of human ecodynamics, historical ecology and environmental archaeology [,,]. The North Atlantic Biocultural Organisation (NABO) was founded in 1992 to improve communication and collaboration between the growing community of scholars studying the archaeology and palaeoecology of the region. Regular research meetings organised between active researchers in the region facilitated an increasing number of interdisciplinary projects spanning the humanities (including archaeology and history) and natural sciences and multiple academic institutes across Europe and North America [,]. Such collaborations came together under the assumption that human activities in the North Atlantic have been inextricably interwoven with their environments []. These studies have focused specifically on human response to environmental changes using a range of analytic tools from the social sciences, humanities and geosciences with significant success in the last 40 years—improving our understanding of the impacts, perceptions and responses to environmental change across the North Atlantic [].

Because the Norse settlement of Greenland occurs at the northern limit of agriculture, and the five centuries of occupation extend from the warm conditions of the Medieval Climate Anomaly (~950–1250 CE) to the profound climate changes of the Little Ice Age (~1250–1860 CE), human interactions with the changing environment has become the dominant research theme []. Since the 1970s and 1980s, archaeological research has moved away from historical sources towards the consilience of archaeology and the environmental sciences [,]. For some, this has created a bias towards environmental drivers for the end of settlement, but at the same time the emphasis on environmental determinism and maladaptation of the 1980s and 1990s has been replaced with an increasing consensus that adaptive flexibility and cultural limits were responsible for the end of settlement [,,]. This accumulation of evidence has coincided with an expansion of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary research of human ecodynamics across the North Atlantic and Greenland especially []. However, the increasing size of the epistemic community, the accumulation of archaeological data and access to new methodologies does not guarantee consensus among researchers. It is necessary, therefore, to examine how different interpretations of this evidence are created and to investigate what processes create this difference.

2. Methodology

A qualitative research design is adopted here to examine the relationship between evidence—what forms of materials, observations, interpretation, analysis and models—and reasoning—argument/dialogue, rhetoric and narrative—were used to articulate stories about the past [,,]. As we are interested in the articulation of evidence in its written form, interview transcripts (texts) formed the basic unit of analysis. Theory from archaeology and sociology of science provided an essential framework for the interpretation of interview texts.

A series of semi-structured interviews were organised with researchers of the Medieval Norse settlements in Greenland. Interviewees were selected using publication frequency analysis to target prominent researchers and snowballing to target other researchers []. The semi-structured format covered six broad questions (Box 1) about the processes driving the end of settlement in Greenland. The flexible interview format allowed a narrative approach to be adopted where interviewees were encouraged to articulate storylines [,]. This extended format was particularly important for encouraging more expansive explanations of evidence and reasoning for a chosen hypothesis. Interviewer reflexivity was also necessary to prevent knowledge bias but also expansion on key themes raised by participants [,,]. This required self-reflection on potential knowledge-bias associated with interview questions and maintaining space for open dialogue with the research participant [].

Box 1. Interview Questions

- Q1.

- What processes do you consider the primary drivers of the end of Norse set-tlement in Greenland?

- Q2.

- What were the causes of population decline in Norse Greenland after the peak in the mid-13th century?

- Q3.

- What happened to the Norse population at the end of settlement in the 15th century?

- Q4.

- What evidence do you use to support your hypothesis?

- Q5.

- With what certainty do you consider your hypothesis to be true?

- Q6.

- What is your appraisal of other existing hypotheses for the end of settlement and how do you repudiate these claims?

Researchers were recruited by email and sent an outline of the discussion format and question in advance of the interview. In total, twelve one-hour in-person, online and phone interviews and one email correspondence were conducted. Interviews were then transcribed for analysis in QSR NVivo 12 data analysis software. This software was used to organise interview data into categorical (descriptive) and analytic (thematic) codes [,]. These qualitative codes allowed an inductive grounded theory method to be utilised to generate themes from the interview transcripts [,]. These categories and themes were then used to structure further analysis of participant discourse.

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) was used to compare texts and examine the underlying semantics of the interview text. CDA is a method of eliciting the meaning, beliefs and the underlying social context of a discourse through analysis of the content and structure of a text [,,,]. CDA focuses on power through work association, emphasis and metaphor within vocabulary, as well as structural organisation of the narrative to build specific storylines []. Identifying how evidence was structured and reasoned within participant interviews was essential to understanding how disciplinary training, geographical and social context, and analogies were used to interpret and reason about the past []. This is an essential step to interpreting the articulation of interview participants’ arguments. Arguments, according to Lucas (2019: 118–124), are constitutive of two elements: premise and conclusion. The premise, which includes evidence and reasoning, is used to justify the conclusions. CDA can be used to examine how such evidence is articulated by examining the semantic language choice used when justifying one’s conclusions (Mayr and Machin 2012). An example in academic research is the use of theory to make sense of data. For example, systems perspective articulates social and ecological data through a framework and keywords that should be consistent with the existing systems literature [].

The choice of theory invites a further step of analysis: the situated context of the research participant. The local and national context of researchers often influences their choice of research tradition and disciplinary orientations []. For example, environmental archaeologists from the United States may emphasise environmental variables but downplay social and cultural mechanisms leading to the end of settlement in Greenland. The situational context of the interviewee would therein be seen as essential to the interpretation of archaeological and environmental data and structure the relationship between evidence and reasoning in the narrative.

3. Results

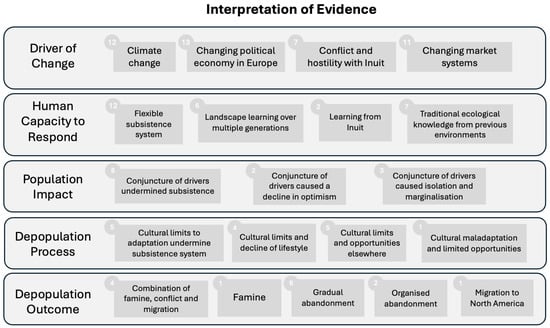

In the first step of analysis, we focus on the relationship between the hypotheses and drivers of decline. Figure 2 shows a summary of narrative themes, starting with the drivers of change and ending with the end-time scenario(s). A detailed table shows the narrative connections between driver, capacities to respond, population impacts, and processes and outcomes of settlement decline by each interview participant (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). This shows a broad consensus between researchers about the exogenous drivers of decline and the evidence of the adaptive strategies adopted by Norse settlers to mitigate such impacts. The subsequent impacts of these processes, at the end of the settlement period, differed between interview discussions. The most common hypothesis, adopted by nine interview participants, was the total abandonment of settlement by the mid-15th century. Eight of these scenarios involved the return to Scandinavian ancestral homelands and the North Atlantic islands and one explored the possibility of extension onto North America. Famine, loss at sea and cultural conflict were also discussed as end-time scenarios, where a remaining population died in situ as a result of climate impacts, economic (and social) isolation and/or hostility with the in-coming Inuit culture.

Figure 2.

Organisation of descriptive themes into drivers of change, human capacity to respond (to change), population impacts, depopulation process and depopulation outcome. A number is provided on each descriptive theme (or code) denoting the number of participants referring to the theme.

It is notable that participants stressed similar drivers of decline and adaptive strategies in response to these drivers but diverge in their hypotheses about what happened at the end of settlement. Evidence of declining returns from farming, political and economic isolation from Europe and to a lesser extent, hostility with the Inuit culture were cited in almost all interviews as drivers of the end of settlement. But why, if there is broad agreement about the processes driving the end of settlement, is there a divergence in the end-time hypotheses? To answer this question, interview narratives were examined for links between the evidence and theory used by participants to interpret, infer and articulate their hypothesis. This was essential to construct an idea of how participants draw multiple lines of evidence together using theory and reasoned judgement of evidence (to justify what is included and excluded) in the articulate a given narrative.

3.1. Evidence and Absence

Interview participants can be divided into two primary categories: those who argue the Norse abandoned the settlement areas for opportunities elsewhere and those who believe the Norse succumbed to a combination of starvation/famine, loss of life in hunting or boating accidents or conflict with the Inuit. We will examine in turn the evidence and reasoning used to articulate these positions. All interviewees qualified their responses with an acknowledgement that the level of certainty is limited by the availability of data and what can be inferred from reliable evidence. Most interviewees focused on the interplay between the chronologies of farm abandonment and modelled demographic changes in Greenland from the 13th and 14th centuries onwards. Participant 1 and Participant 2 cited evidence of reduced vegetation disturbance and household occupation using a combination of pollen and survey data and radiocarbon dates (Box 2). The abandonment of marginal land in the Eastern Settlement in the 14th century and the absence of new farms in core areas would suggest a declining population. However, the abandonment of these sites does not infer depopulation—as acknowledged by both researchers. This is a point raised by Participant 3 and Participant 4, who were sceptical of this interpretation of abandonment (Box 3). As they explained, farm abandonment does not necessarily mean a decline in population, as the population could reorganise or reoccupy different parts of the landscape. Comparative evidence of abandonment and settlement reoccupation in Iceland was cited in support of this scenario. This scenario is also considered by Participant 5, who explains that population movement between farms is a key question still to be resolved, as the interplay of between abandonment and occupation of sites produces multiple different scenarios.

Box 2. Abandonment

What we would do to pollen analytically is, when we start to see the restoration of shrub (willow, birch, etc.) in our records and the amount of grass is going down and the other weeds indicates that the agricultural activity is perhaps on the decline. When all that is happening, you’re getting a threshold crossing event. You can assume, with a severe reduction, that it has been abandoned. But of course, they might have just moved another 500 yards away, but we’re not getting that. We’re getting the vegetation point of view and we have to make inferences that explain that. Its then a step change from the pollen evidence to explain that people are leaving because farming is becoming difficult. […] But we don’t see that, so you have to connect this data with the economic context and associated demographic factors. These factors are raised in the background but obviously the pollen doesn’t say that.(Participant 1)

Is it because there are less people [in a slow decline] or are there more and more people concentrated in the core areas? I don’t think so because all of the farms that we do have in the core areas, they are mostly traced back to Landnam. So, you don’t really see new farms, but you do see a few new churches in the core areas. And that could of course be because you have more people coming in, so you need more churches—two churches, I think, are new and built after 1250 AD. So that might indicate that you have more population coming into the core area, but I think you basically have fewer and fewer people. I think that Lynnerup is right.(Participant 2)

Box 3. Alternative interpretation of abandonment

I suspect there weren’t that many of them left, but one of the things we do know is that people have a remarkable attachment to particular places. […] although the story in Greenland is so enigmatic, it’s what we know about people and also that there are changes and there are times when people will get up and go (leave) but the difference between abandoning the valley, and moving down valley, about abandoning the uplands for the lowlands – that sort of movement.(Participant 4)

One thing to realise is that we can see abandoned settlements, but we don’t really know about the population. We’re assuming that an abandoned farm means one family less, but that is not really the case because we know in Iceland for example that there are lots of abandoned farms, but they are just going somewhere else. Usually what is happening is that they are just becoming ten-ants or landless labourers.(Participant 3)

Resolving uncertainty of where people went following the abandonment of marginal areas required inference or abstraction to explain social processes that are not evident in the archaeological record. Because the evidence is not sufficiently resolved to explain the outcome of farm abandonment (cause and effect), this becomes a matter of inference from inductive or deductive reasoning. Participant 6, for example, deduces an abandonment scenario because of limited evidence for excessive violence or economic decline in the 14th century. They also interpret the evidence of household abandonment in the wider historical context of Europe and the North Atlantic—a decline in optimism in Greenland and opportunities for livelihood elsewhere. For this reason, they argue that the elites in society would organise a departure because of a decline in relative prosperity. For Participant 4 and Participant 3, the inverse of this scenario is true. They argued that there was little incentive for elite groups to move to Iceland because they would become “penniless refugees” by moving to Iceland or Norway. So, this argument goes, if the purpose of occupying Greenland was to claim land and establish a following, a return to Iceland or Norway would have meant submitting to feudal lords.

Because interview participants drew upon multiple lines of evidence, they explained that evidence from the settlement areas required contextualization in light of broader environmental, economic and social context. The challenge of articulating social change from limited evidence is discussed in Participant 1’s interview.

It’s then a step change from the pollen evidence to explain that people are leaving because farming is becoming difficult. You can think of this as either a determination of climate or prolongation of the little ice age. But we don’t see that, so you have to connect this data with the economic context and associated demographic factors. These factors are raised in the background but obviously the pollen doesn’t say that.

The conclusions that are derived from pollen evidence are combined with the economic and demographic context. This articulation of evidence resembles Wylie’s [] “cabling” metaphor; evidence does not speak for itself but is inferred by combining multiple strands of evidence.

3.2. Absence and Inference

With evidence so limited at the end of settlement, a significant sticking point between researchers was the use of absence as evidence. How absence is interpreted and combined with other evidence can produce multiple different scenarios []. In this case, different expectations of what should be found in the archaeological record and historical accounts led to different interpretations of absence. The absence of evidence for subsistence crisis and conflict was cited in several interviews as a case for abandonment. However, absence of evidence was also questioned as a “weak” or “partial” interpretation of human and environmental records in Norse Greenland. Here, we focus on the absence of boats, bodies and elite material culture as evidence for different depopulation scenarios.

One issue raised by several interviewees with the abandonment hypothesis was the absence of ocean-going boats and the absence of local wood and iron resources for construction of sea-worthy vessels.

Leaving Greenland is a problem. To me, the problem is that they can’t build big ocean-going boats in Greenland. They don’t have the wood and there is no evidence that they ever maintained ocean-going vessels.(Participant 4)

Where did they get the boats? […] Even so, if you think about the carrying capacity of the boats, and a bit of back of the envelope calculations you’re talking about at least a hundred round trips between Iceland and Greenland. And that just doesn’t seem to be something happening without someone noticing.(Participant 3)

I don’t think they had any ocean-going boats. They were really dependent on Norwegian boats. So, they depended on what was going on in Norway.(Participant 2)

The absence of evidence for ocean-going boats in historical and archaeological records suggests that the Norse did not have the capacity to leave Greenland. Historical sources do mention that 6-oared boats and toy boats of the same design have been recovered from the Western Settlement [,], but these boats were not ocean-worthy.

But whereas Participant 3 and Participant 4 suggest that this infers a limited capacity for abandonment, Participant 2 does not consider this adequate evidence that the Norse could not leave. As they argued, “many boats were blown off-course and there must have been unacknowledged voyages between Iceland and Greenland.” Participant 6 takes this point further explaining that there would not be historical evidence for the abandonment because it would limit their legal claim to Greenland if they were to return.

“I think there was never an acknowledgement that nobody was there. Either they thought that there were still people there, or they chose to believe that it was easier politically and economically and they wanted to maintain rights to property.”

This raises a significant question about the nature of absence in the archaeological and historical records to which we will return in the discussion: can a complex sociopolitical rationale, such as this, be inferred from the absence of historical evidence? The relative absence of boats was also countered with the argument that an absence of bodies found in homes provides further evidence that the Norse did not stay. However, an absence of bodies is difficult to establish when very few building from the very last

Phase of occupation in the core areas of the main settlement areas have actually been excavated.

The absence of bodies lying in houses and any osteological evidence of starvation is a sticking point for the famine hypothesis. Lynnerup’s [] analysis of Norse skeletal remains revealed no evidence of starvation nor diseases associated with excessive hunger. Furthermore, the absence of bodies in households has often been considered a case in point that the Norse did not succumb to starvation [,]. Table 1 provides a summary of hypotheses explaining the absence of evidence for famine and bodies in houses. Participant 8, Participant 2 and Participant 7 all acknowledge that there would probably have been casualties during the decline, but the absence of “skeletons in the houses” is considered evidence that food shortages were not widespread. Participant 7 explains that abandonment could have, in theory, taken place over multiple centuries with a small, vulnerable population remaining that could not support subsistence.

Table 1.

Reasoning from interviewees to dismiss starvation as a drivers of Norse settlement termination.

However, Participant 3 and Participant 4 argue that the absence of bodies still provides little evidence that they did leave. Three significant points are raised here: the lack of preservation, lack of representative archaeological evidence and the possibility of mass death at sea. Participant 3 and Participant 4 cautioned against the suggestion that absent bodies infers the abandonment of settlement and therefore that the Norse did not succumb to famine. Their argument rests on the point that the absence of bodies from the limited number of sites that have been excavated is not adequate evidence to infer a lack of evidence for the in situ deaths of the last Norse Greenlanders. Participant 4 makes direct reference to Pompeii, arguing that the absence of bodies could suggest a whole array of possible scenarios, including poor preservation or the consumption of human remains by animals. Participant 3 also explains the importance of Christian burial in Norse society, explaining that it was an essential duty for the dead to be inhumed soon after death. Such arguments about the representation of archaeological evidence were also applied to the analysis of material culture.

Excavations in the Eastern and Western Settlement have recovered a limited array of status finds—or elite material culture—even on high-ranking manor farms (Arneborg 2000). The absence of elite material culture was discussed in several interviews as evidence of organised abandonment of the settlement. As Participant 7 explained, the lack of elite material culture at significant sites such as Gardar and other church farms suggests that precious metals and holy objects were removed before the Eastern Settlement was abandoned in the 15th century (Table 2). Participant 4 and Participant 3 queried the extent to which the Norse Greenlanders ever had great quantities of elite material culture. As Participant 3 explains, “sampling error” from archaeological excavations can also overrepresent the relative level of elite objects from each site. A further issue for archaeologists in Greenland would has been the lack of systematic excavation carried out on major farms in the late 19th and early 20th century. This, Participant 3 suggested, could have caused the loss of great quantities of material culture. Furthermore, Participant 3 questions the extent to which the Norse ever had status goods as we would expect from these sites (Table 2).

Table 2.

Interviewees reflecting on the lack of known bodies.

3.3. Models, Comparison and Analogies

Theoretical models, ethnographic analogies and comparative methods were all used, in interviews, to overcome absence in the archaeological record. This section will cover each of these methods in turn. First, comparisons with other Norse archaeological contexts in the North Atlantic where contemporaneous historical records are available. Second, analogies with ethnographic processes used to explain the presence or absence of material culture or likely depopulation scenarios. And third, models and scenarios were used to construct hypotheses and to provide evidence of likely social changes and environmental limits. As we will argue, direct and indirect analogies were used as “paramorphic models” to overcome absence at the end of Norse settlement in Greenland []. However, the use of different analogies to explain social processes in Greenland can produce contrasting models and scenarios depending on how evidence is triangulated.

The common cultural heritage of Norse Greenland and Iceland has provided a strong basis for comparison of the settlements in Greenland—without any direct, contemporary historical record—and the historical records and legal texts in Iceland []. Because there is a clear cultural link between these settlements, it has long been used as a basis for direct ethnographic comparison and particularly to explain social and economic organisation of the Norse settlement areas in Greenland [,,,,]. However, the differences in geographical contexts do limit this comparison because of the relative isolation of the Greenland settlement and the different resource systems that led to different styles of sustenance, trade, clothing and settlement structure [,]. However, the extent to which this can indicate anything about the end of settlement is unclear.

Indirect analogies from different cultural and geographical contexts were used throughout all interviews to explain the absent Norse population at the end of settlement in Greenland. Table 3 provides a list of the analogies and their geographical contexts. Contemporary experiences of intra- and inter-continental migration were highlighted significantly as evidence of “ordinary human behaviour.”

Table 3.

Indirect analogies invoked to explain key characteristics of the ending of Norse Settlement.

I like to ask ‘what adds up as ordinary human behaviour?’ and that’s why I keep putting in what we know today because today there are young people moving from North Africa because they want to earn money and get a new life, so it is young people moving in search of opportunity, and I think that is a very, very old story. And I think that’s what makes it fit because the pieces of the puzzle come together. There is a push and pull factor over two-hundred years, and people could easily go back into the bigger Norse society.(Participant 7)

Well, look around and see who is moving away from North Africa and Afghanistan. It’s all the people from 16–18 years of age, all of the young people are leaving. They have the strength to leave and to build up a new life somewhere else.(Participant 2)

“In the news, we see cases of people migrating away from the Middle East and Iraq because they cannot sustain themselves.”(Participant 8)

The analogies used here reflect no common cultural or environmental driver to leave, but instead what Participant 6 has described as the “evaporation of [relative] optimism” among young demographic groups. As Participant 7 explains, this analogy fits the puzzle and what would be considered key motivations to leave—pushing and pulling young groups away from Greenland and back to Iceland and Scandinavia. Their argument is that this fits what normal human behavioural traits, as an adaptation strategy to survive and as an opportunity afforded by social networks across the North Atlantic.

Analogies were used in both theoretical and mathematic models of end-time scenarios. The demographic analogues of migration in Europe, North African and the Middle East provided a basis for Participant 7’s demographic model scenarios.

I did some research on demographics, and we can actually model a small number of people leaving on average each year. And this will draw the population below sustainable levels. […] We’re seeing it in the Mediterranean everyday now. Its young people who feel that they can make a better living elsewhere. So, I think that being the number two or number three son in a reasonable farm, in the 13th century, in Greenland—well, who is going to inherit? Even though Greenland is huge, the arable land available for getting fodder is after all only of a certain size. So, what can you do if you are son number three? And you need to get some cattle going to get married. And again, to get married with the population of only 2–3000 the selection might not be that huge.

The scenarios explored in Participant 7 demographic model, as he explained, were developed from his experience of Danish migration patterns, with young groups moving from rural towns into urban areas. In this model, Participant 7 explored the impact of population decline on population size and reproductive rates. Key variables in this model were developed from a combination of input data from Norse Greenland church burials, ethnographic data from contemporary Iceland and assumptions based on historical texts and assumptions of stable population size.

3.4. Geography, Discipline and Nationality

Two major themes arising from all interviews was the influence of local and national research traditions and field experience on the interpretation of evidence. Because interview participants spanned four different disciplines (archaeology, anthropology, history and geography) and several research traditions (environmental, social, medieval (pre-historic) and historical archaeology, biological anthropology, palynology, soil science, environmental geography, and history), this also had a significant bearing on the articulation of evidence. Table 4 provides a summary of the nationality and discipline of each interview participant.

Table 4.

Disciplinary and national backgrounds of the participants.

Geographical and disciplinary differences were expressed in multiple interviews. Participant 8 explained that the way archaeologists, in particular, interpret evidence is influenced by research traditions associated with different regions. For example, North American archaeology is intimately coupled with anthropology, drawing a great deal of theory especially from ethnology and the observations of cultural material practices [,]. In Box 4 they refer directly to the use of ethnographic analogy in North American archaeology. Participant 8 also discussed the influence of contemporary concerns, such as climate change, on research in Greenland. In particular, the influence of national research agendas is highlighted as a vehicle for funding but also understanding the relationship between human adaptation in the past and what it can tell us in the present. Participant 2 was more cautious about the influence of national research traditions on interpretations of human–environment interaction (Box 4). For Participant 2, Anglo-American researchers studying Medieval Greenland have been influenced by trends in academic discourse and paradigms in archaeology and geography, including environmental determinism in the 1980s and 1990s and climate change research from the 2000s. Anglo-American research in Greenland has been heavily influenced by environmental archaeology since the 1970s, whereas Scandinavian archaeology, by contrast remains within continental German research traditions that use historical sources to contextualise archaeological evidence.

Nationality and the “baggage” associated with research training in and experience of “temperate” environments was also discussed in multiple interviews. This theme was most evident in Participant 10’s discussions of American and Danish archaeology and history.

“[Participant 3] is not an historian, he doesn’t know any of the histories from Norway, and he has never understood the basic Norse economy that was brought along to Iceland and Greenland. So much has been influenced by the Danes, who have nice fertile soil, and who find it very difficult to imagine a rural place without villages. Well, you can’t have villages in a place where there are lots and lots of rocks…”(Participant 10)

For Participant 10, the lack of experience in hostile environments such as Arctic Norway have skewed the Danish (and Anglo-American) interpretations of Norse economies in Iceland and Greenland. But this failed to acknowledge the closer cultural and geographical connection between Iceland and Medieval Greenland. As Participant 2 argued, Icelandic cultural history has been an important ethno-historical analogy for understanding the organisation of Norse society in Greenland. Participant 2 went on to explain the historical context for national disputes over the North Atlantic islands:

Because of the way they [the North Atlantic islands] were split up after the Napoleonic wars, the Norwegians never really forgave the Danes for that… Helge Ingstad wanted to say that the Danes don’t really know their stuff because it isn’t Danish culture… the Norwegians never really trusted the Danes to do a proper job because it was not their culture.(Participant 2)

This reflection on research history in Scandinavia provides an important insight into the disputed terrain of historical interpretation. The contested geopolitical and cultural history of the North Atlantic itself is a basis for contested knowledge claims, especially in the context of ethnographic analogy.

Box 4. Geography and Research Tradition

Have you spoken to many North American archaeologists? Because North Americans are taught anthropology and you might find more of that in the North American audience. […] I think [Participant 3] would be inclined to use ethnographic analogies. […] a lot of the rea-son why there is the availability of money to do research in the Arctic is because climate change is (and was) a big research agenda. We wanted to understand how people in the past adapted to climate change and what sort of impacts this will have today.(Participant 8)

I think that subjects such as climate studies, at least in the past and not so much now, had a bigger appeal to Anglo-American research. For instance, [Participant 3] and An-glo-Americans were more routed in what is happening in the time you’re living in, so you try to bring that in. In the beginning it was over-utilisation, you were simply destroying the resources, which was of the time in the 1980s and 1990s. [Participant 3] was very much into that. And now comes the climate change phase and (their) very much into that. Whereas Scandinavians have more of a continental German research tradition where we go into the sources and we see what they can say and what we can deduce from them. […] But when you have this very Anglo-American approach you go ‘oh god!’ because you can put it into a model and say this and this, but they forget that we have a source saying this…(Participant 2)

Demonstrable knowledge of “the field” was one-way researchers sought to overcome bias. Fieldwork and field experience were raised as important contexts for interpretation and contextualisation. In Participant 4’s discussion of fieldwork and interpretation, he reflected on the specific importance of experience in the field together with an understanding of the broader regional dynamics.

An understanding of the geographical differences between the North Atlantic islands and the broad political, economic and social context of the Middle Ages is essential if you are to contextualise archaeological finds in Greenland. It is sometimes possible to overread the importance of outliers from a single context. Contextualisation can suffer if materials are not understood in relation to the broader spatial, temporal and cultural dynamics.(Participant 4)

This quote reflects the importance of the contextualization of finds within the broader social and environmental dynamics of the North Atlantic. Knowledge not only of the field (local and regional environments), but also the cultural-historical context (historical texts and multiple archaeological contexts), were highlighted throughout interviews as essential grounding to interpretation. In this case, knowledge is not only placed in the field as location and expertise but results also from experience and accumulation of knowledge in one’s field and through collaboration with other researchers.

A more direct reflection on the importance of the field as a space with which interpretation and knowledge production take place is reflected in Participant 5 and Participant 9’s reflections on experience, deliberation and notetaking.

… I didn’t anticipate what an impact extended time in the field would have on my understanding and interpretation of life in Norse Greenland.(Participant 5)

I’ll have to get my notes to remember what we recorded and discussed in the field […] a lot of this information on ruin groups and homefield management comes from discussions with Christian and Konrad in the field.(Participant 9)

In Participant 9’s interview, he described the field as not only a site for observation but also discussion and deliberation between researchers with different forms of disciplinary expertise. He reflected on the scaling from soil profiles and samples that inform him of land-use and management practices, up to landscape and settlement scales of interaction between sites. Discussion allowed his notes to be collected and contextualised in situ. For Participant 5, the extended experience of the field is essential to guiding the interpretation of such results and understanding the capacities and limitations on human activities in the Greenland environment. Historical and ethnographic information was important for the triangulation and contextualization of archaeological data (site location, use) about human–environment interaction, including historical hunting and stocking records and observations/experience of seasonal hunting and animal herding.

4. Discussion

It is clear from the interviews in this study that no granular consensus for the end of settlement exists within the active research community studying the end of the Medieval Norse settlements in Greenland. However, interviews and existing data show a broad consensus as to the drivers leading into the final stages of settlement in Greenland (see Table S1). All interviewees acknowledged the role of the deteriorating climate and increasing economic isolation from Europe, but the impact this had on the Norse population themselves remains contested. Interpretations of the same evidence produced different narrative of depopulation. This raises the question of how interpretation of the same evidence produces divergent conclusions. In the first instance, this question can be answered quite simply, as summarised in Participant 6’s interview: “there is no longer any single-track hypothesis about why this place came to an end. We know enough to know there cannot be just one explanation.” This is because there is a significant level of uncertainty raised by multiple lines of evidence and the simultaneous absence of clear archaeological evidence of famine or abandonment. In the section that follows, we will synthesise the key themes and theory discussed in this paper so far to explain the role of interpretation and how they are situated within distinct geographical and disciplinary networks.

4.1. Absence, Representation and Uncertainty

For participants in this study, absence was a significant point of departure. Disagreement about what can be inferred from the absence of ocean-going boats, skeletal remains in households and elite material culture revolved around questions of representation, preservation and significance. What can be inferred from the absence of elite material culture rests on expectations of what should be found in the archaeological context. The foundation of these arguments’ rests on the interplay between evidence, absence and the use of theory and other resources to articulate the human activities.

Archaeologists and historians are always faced with absence. There are the absent subjects (or people), with which to animate the past, and the archaeological record is always partial, recoverable as traces of the full material assemblages of the past [,]. As Lucas [] explains, archaeologists interpret and construct the past through the interplay between absent things and absent people. This leads to multiple different articulations of the past, using the fragments, or traces, of the past, to construct models or draw analogies with similar social phenomena from other spatial and temporal contexts.

4.2. Analogy and Models

Analogies and models have been used widely in research of Norse Greenland. Theoretical and quantitative models have been used to test the sensitivity of the Norse subsistence system and to consider different scenarios leading to subsistence crisis [,,,]. These models draw upon assumptions from analogies with Icelandic farming and ethnohistorical information from other societies in the North Atlantic. However, what such analogies can reveal about the past has been a persistent question in archaeology [,].

One criticism of ethnographic analogies is that they merely operate as a heuristic to ask “what if” questions [,]. For example, Participant 7’s model of population decline uses population data from churchyard burials in Greenland but combines this with ethnographic assumptions from pre-modern Iceland and tests a constrained depopulation scenario that assumes the Norse emigrated from Greenland [,]. This model does, however, provide an essential building block in the debate about interpretation. By providing a scenario for decline it raises significant questions to be asked of the archaeological record: how do we corroborate evidence that the Norse emigrated using material remains in Norway or Iceland?

Another example of these “what-if” questions was raised in Participant 3 and Participant 4 interviews and two research publications featuring decline scenarios. Dugmore and colleagues [] examined a range of scenario inputs and outcomes in their conceptual model of collapse, focusing on the interplay between resource availability and population size over time. The conclusion of this model and study was that the Norse succumbed to subsistence crisis and famine as “population decline forces a contraction in resource utilisation” []. This resulted in feedback loop forcing a continuing decline in both population and available resources []. However, population decline could also represent the same economic determinants that Lynnerup uses to explain the gradual depopulation [,].

In another model by Dugmore and colleagues [] different population and subsistence scenarios are considered, using a comparison with the Inuit. Using an adaptive cycle diagram to frame different scenarios [], they reason that different mixes of farming and hunting or a larger population may have delayed the decline of a mixed farming-hunting economy (possibly until economic contact with Europe was restored), but that hunting without farming represents an alternative social-ecological regime [].

The use of analogical inferences in this study are highly varied and draw upon evidence from multiple different geographical and temporal contexts. Most analogies are based on what Currie [] terms indirect analogies, where a group with no direct continuity with the group in question is used to explain social, economic and cultural dynamics. As Currie [] has argued, such indirect or surrogate evidence can be likened to experimental interventions in scientific experiments—especially in biology. They operate to fill gaps as leverage points within the multiple strands of evidence that are used to assess hypotheses []. By actively discussing different models of decline, it would be possible for researchers to better understand the role of interpretation in different narratives. On these grounds, Currie [] defends the use of indirect analogy to make the past empirically tractable.

4.3. Research Traditions and Geography

The flip side of this is the role that theory plays in articulating narratives. Choice of analogy and the models constructed from this are responsible for retroactively articulating strands of evidence into different configurations. For example, the relative influence of environment on subsistence depends on the way such environmental and social data is combined (e.g., systems theory), inferences used to articulate decision-making (e.g., decline of optimism, analogy with migration). Geography, discipline and research traditions play important roles in the interpretation of data—North American emphasis on environment and climate (environmental archaeology) and Scandinavian focus on continental German approaches to Norse (historical archaeology) [,,].

Narrative plays an essential role in the production of knowledge claims insofar as it privileges certain evidence and articulates it into a clear storyline that “hides the discontinuities, ellipses and contradictory experiences that would undermine the intended meaning of its story.” [], pp.1349–1350. The narratives explored in this paper are produced through the articulation of different combinations of data, theory and social relations. Social and environmental information is articulated through the specific disciplinary and theoretical lenses through which evidence is organised, valued and interpreted in different ways [,].

But there is no single way of triangulating evidence and articulating narratives. The choice of theoretical framing and narrative structure in each of the interviews was based on a combination of discipline, or field of study, normalising standards of practice and prioritisation of certain forms of knowledge [] and the situated context of the researcher and institution: nationality and institutional traditions [,]. The local specific conditions of knowledge production played a significant role in the way each researcher drew analogies between ethnohistorical and contemporary analogies with the past []. The situated context of knowledge production has been discussed widely in archaeological theory, and especially in debates about interpretation of the past []. As Julian Thomas [] summarises, archaeologists must be self-aware when drawing analogies to reconstruct the past. Knowledge production is not a “view from nowhere” [] but situated social practice []).

As discussed in the opening to this paper, there is much that is agreed upon in the narrative of Norse Greenland. However, subtle differences in interpretation can lead to drastically different hypotheses about decline. As Hodder [] explains, the archaeological record does contain a reality that is independent of our own interpretation—a guarded objectivity. However, interpretation must remain critical and responsive to its own assumptions of objectivity and coherence [].

Interpretations of sites, improved chronologies and increased resolution of environmental change in Norse Greenland make the interpretation of the past an ongoing cyclical and spiralling process of analysis and reanalysis. This hermeneutic circle (or spiral) requires an ongoing reflection on accumulated evidence and how we as researchers are interpreting it []. The North Atlantic is a highly interdisciplinary and interconnected research network where discussions of theory and interpretation are highly varied. Perhaps it is time to facilitate a more open dialogue on how researchers from multiple disciplines and research traditions are interpreting the past, and from there identify new research questions to ask and hypotheses to test in the future.

5. Conclusions

The range of depopulation scenarios for Norse Greenland demonstrates the complex task of interpreting past human–environmental interaction in general and the role of climate change in human affairs in particular. This paper has examined why and how Norse Greenland researchers interpret the same evidence for settlement depopulation in different ways. Two broad scenarios are still debated—mass death and abandonment—but both rely on the same evidence, albeit interpreted in different ways and articulated into particular narratives. Geographical and disciplinary factors play a significant role in the relative emphasis of environmental, climatic and social data, as well as biases in the use of analogy. Researchers tended to utilise familiar analogues to interpret human activities and triangulate archaeological and environmental datasets. Critically, the way narratives are articulated are situated in the place of production, whether such interpretations reflect national, institutional or disciplinary traditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage8080293/s1, Table S1: participants’ contrasting views on why and how Norse Greenland settlement ended. TEK stands for Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.; methodology, R.J. and A.D.; software, R.J.; validation, R.J.; formal analysis, R.J.; investigation, R.J.; resources, R.J.; data curation, R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, R.J. and A.D.; visualization, R.J. and A.D.; supervision, A.D.; project administration, R.J. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a joint doctoral training grant from the University of Edinburgh and Aarhus University.

Data Availability Statement

This article includes original data collected using interviews with academic experts. Research ethics were approved by the School of GeoSciences ethics committee at the University of Edinburgh.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare in this study.

References

- Jesch, J. The Viking Diaspora; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raffield, B.; Price, N.; Collard, M. Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: An evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2017, 38, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugmore, A.J.; McGovern, T.H.; Vésteinsson, O.; Arneborg, J.; Streeter, R.; Keller, C. Cultural adaptation, compounding vulnerabilities and conjunctures in Norse Greenland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3658–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.; Arneborg, J.; Dugmore, A.; Madsen, C.; McGovern, T.; Smiarowski, K.; Streeter, R. Disequilibrium, adaptation, and the Norse settlement of Greenland. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 665–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.; Arneborg, J.; Dugmore, A.; Harrison, R.; Hartman, S.; Madsen, C.; Ogilvie, A.; Simpson, I.; Smiarowski, K.; McGovern, T.H. Success and failure in the Norse North Atlantic: Origins, pathway divergence, extinction and survival. In Perspectives on Public Policy in Societal-Environmental Crises: What the Future Needs From History; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed; Revised Edition; Penguin: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, W.J.; Huang, Y.; Fritz, S.C. Abrupt Holocene climate change as an important factor for human migration in West Greenland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9765–9769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Castañeda, I.S.; Salacup, J.M.; Thomas, E.K.; Daniels, W.C.; Schneider, T.; De Wet, G.A.; Bradley, R.S. Prolonged drying trend coincident with the demise of Norse settlement in southern Greenland. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R. Natural Experimental Approach to Vulnerability, Resilience and Adaptation in Historic Greenland. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Folger, T. Why did Greenland’s Vikings vanish? In Smithsonian Magazine; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan, J. Why Did the Vikings Disappear from Greenland? 2023. Available online: https://www.history.com/news/why-did-the-viking-disappear-from-greenland (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Martin, S. Archaeology News: ‘Perfect Storm’ Including Black Death Wiped out Greenland’s Vikings. 2020. Available online: https://www.express.co.uk/news/science/1231743/archaeology-news-vikings-black-death-history-greenland-climate-change (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Kintish, E. Why did Greenland’s Vikings disappear? Science 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorich, Z. Greenland’s Vanished Vikings. Sci. Am. 2017, 316, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugmore, A.J.; McGovern, T.H.; Streeter, R.; Madsen, C.K.; Smiarowski, K.; Keller, C. Clumsy Solutions’ and ‘Elegant Failures’: Lessons on Climate Change Adaptation from the Settlement of the North Atlantic. In A Changing Environment for Human Security: Transformative Approaches to Research, Policy and Action; Sygna, L., O’Brien, K., Wolf, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M.C.; Ingram, S.E.; Dugmore, A.J.; Streeter, R.; Peeples, M.A.; McGovern, T.H.; Hegmon, M.; Spielmann, K.A.; Simpson, I.A.; Strawhacker, C.; et al. Climate Changes, Vulnerabilities, and Food Security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.C.; Kintigh, K.W.; Arneborg, J.; Streeter, R.; Ingram, S.E. Vulnerability to Food Insecurity: Tradeoffs and Their Consequences. In The Give and Take of Sustainability: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives on Tradeoffs; Hegmon, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vésteinsson, O.; Hegmon, M.; Arneborg, J.; Riche, G.; Russell, W.G. Dimensions of inequality. Comparing the North Atlantic and the US Southwest. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2019, 54, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egede, H. The New Perlustration of Greenland; International Polar Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nedkvitne, A. Norse Greenland: Viking Peasants in the Arctic; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R.; Wylie, A. Evidential Reasoning in Archaeology; Bloomsbury Academic Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arneborg, J. Norse Greenland—Research into abandonment. In Medieval Archaeology in Scandinavia and Beyond: History, Trend and Tomorrow; Roesdahl, E., Graham-Campbell, J., Kristiansen, M.E., Eds.; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dugmore, A.J.; Keller, C.; McGovern, T.H. The Norse Greenland settlement: Reflections on climate change, trade and the contrasting fates of human settlements in the Atlantic islands. Arct. Anthropol. 2007, 44, 12–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vésteinsson, O. Parishes and communities in Norse Greenland. J. North Atl. 2009, 2 (Suppl. 2), 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, J. Did the medieval Norse society in Greenland really fail? In Questioning Collapse: Human Resilience, Ecological Vulnerability, and the Aftermath of Empire; McAnany, P.A., Yoffee, N., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McAnany, P.A.; Yoffee, N. Questioning Collapse: Human Resilience, Ecological Vulnerability, and the Aftermath of Empire; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dugmore, A.J.; Keller, C.; McGovern, T.H.; Casely, A.; Smiarowski, K. Norse Greenland Settlement and Limits to Adaptation. In Adapting to Climate Change; Adger, N.W., Lorenzoni, I., O’Brien, K.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, K.M.; Coutu, A.N.; Smiarowski, K.; Harrison, R.; Madsen, C.K.; Arneborg, J.; Frei, R.; Guðmundsson, G.; Sindbæk, S.M.; Woollett, J.; et al. Was it for walrus? Viking Age settlement and medieval walrus ivory trade in Iceland and Greenland. World Archaeol. 2015, 47, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzhugh, B.; Butler, V.L.; Bovy, K.M.; Etnier, M.A. Human ecodynamics: A perspective for the study of long-term change in socioecological systems. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 23, 1077–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrecht, G.; Anderung, C.; Brewington, S.; Dugmore, A.; Edvardsson, R.; Feeley, F.; Gibbons, K.; Harrison, R.; Hicks, M.; Jackson, R.; et al. Archaeological sites as Distributed Long-term Observing Networks of the Past (DONOP). Quat. Int. 2018, 549, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, T.H. Management for extinction in Norse Greenland. In Historical Ecology: Cultural Knowledge and Changing Landscapes; Crumley, C.L., Ed.; University of Washington Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, S.; Ogilvie, A.E.J.; Ingimundarson, J.H.; Dugmore, A.J.; Hambrecht, G.; McGovern, T.H. Medieval Iceland, Greenland and the New Human Condition: A case study in integrated environmental humanities. Glob. Planet. Change 2017, 156, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, T. The Archaeology of the Norse North Atlantic. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1990, 19, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronon, W. A place for stories: Nature, history, and narrative. J. Am. Hist. 1992, 78, 1347–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, I. Writing archaeology: Site reports in context. Antiquity 1989, 63, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G. Writing the Past: Knowledge Production and Literary Production in Archaeology; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, C. Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roulston, K. Reflective Interviewing: A Guide to Theory and Practice; Sage Publications e-book: New York, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781446248140. Available online: http://digital.casalini.it/9781446248140 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Lynch, M. Against reflexivity as an academic virtue and source of privileged knowledge. Theory Cult. Soc. 2000, 17, 26–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riach, K. Exploring participant-centred reflexivity in the research interview. Sociology 2009, 43, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, M. Coding qualitative research. In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, 3rd ed.; Hay, I., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. Handb. Qual. Res. 2000, 2, 509–535. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted with Description; The Sociology Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 1-884156-15-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Discourse, social theory, and social research: The discourse of welfare reform. J. Socioling. 2000, 4, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.; Oswick, C.; Hardy, C. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Discourse; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, N.; Hardy, C. Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R. The discourse-historical approach. Methods Crit. Discourse Anal. 2001, 1, 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Routledge, B. Scaffolding and concept-metaphors: Building archaeological knowledge in practice. In Explorations in Archaeology and Philosophy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinski, J. Making Natural Knowledge: Constructivism and the History of Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, A. Invented lands, discovered pasts: The westward expansion of myth and history. Hist. Archaeol. 1993, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G. Triangulating absence: Exploring the fault lines between archaeology and anthropology. In Archaeology and Anthropology: Understanding Similarity, Exploring Difference; Garrow, D., Yarrow, T., Eds.; Oxbow Books: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roussell, A. Sandnes and the Neighbouring Farms; Meddelelser om Grønland 88:2; Kommissionen for Ledelsen af de Geologiske og Geografiske Undersøgelser i Grønland: København, Denmark, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Roussell, A. Farms and Churches in the Mediaeval Norse Settlement of Greenland; Meddelelser om Grønland 89, 2; Kommissionen for Ledelsen af de Geologiske og Geografiske Undersøgelser i Grønland: København, Denmark, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Lynnerup, N. The Greenland Norse: A Biological-Anthropological Study; Man & Society: Hong Kong, China, 1998; Volume 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridriksson, A.; Vésteinsson, O. Creating a Past: A Historiography of the Settlement of Iceland. In Contact Continuity and Collapse: The Norse Colonization of the North Atlantic; Barrett, J.H., Ed.; Brebols Books; Brepols Publishers: Turnhout, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Perdikaris, S.; McGovern, T.H. Codfish and Kings, Seals and Subsistence: Norse Marine Resource Use in the North Atlantic. In Viking Voyagers; Rick, T.R., Erlandson, J.M., Eds.; UCLA Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern, T.H.; Harrison, R.; Smiarowski, K. Sorting sheep & goats in medieval Iceland and Greenland: Local subsistence or world system. In Long-Term Human Ecodynamics in the North Atlantic: An Archaeological Study; Harrison, R., Maher, R.A., Eds.; Lexington Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hayeur-Smith, M.; Arneborg, J.; Smith, K.P. The ‘Burgundian’hat from Herjolfsnes, Greenland: New discoveries, new dates. Dan. J. Archaeol. 2015, 4, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegsberg, M. Houses and households in Viking Age Scandinavia: Some case studies. In Dwellings, Identities and Homes: European Housing Culture from the Viking Age to the Renaissance; Kristiansen, M.S., Giles, K., Eds.; Jutland Archaeological Society Publications; Jutland Archaeological Society: Hojbjerg, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, C. The great tradition versus the great divide: Archaeology as anthropology? Am. J. Archaeol. 1980, 84, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, L.R. Archaeology as anthropology. Am. Antiq. 1962, 28, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G. Critical Approaches to Fieldwork: Contemporary and Historical Archaeological Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, L.K.; Sadler, J.P.; Ogilvie, A.E.J.; Buckland, P.C.; Amorosi, T.; Ingimundarson, J.H.; Skidmore, P.; Dugmore, A.J.; McGovern, T.H. Interdisciplinary investigations of the end of the Norse Western Settlement in Greenland. Holocene 1997, 7, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynnerup, N. Paleodemography of the Greenland Norse. Arct. Anthropol. 1996, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Arneborg, J. The Norse Settlements in Greenland. In The Viking World; Brink, S., Price, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, A. The Reaction Against Analogy. Adv. Archaeol. Method Theory 1985, 8, 63–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, A. How archaeological evidence bites back: Strategies for putting old data to work in new ways. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2017, 42, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, A.M. Narratives, mechanisms and progress in historical science. Synthese 2014, 191, 1163–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, A. Ethnographic analogy, the comparative method, and archaeological special pleading. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part A 2016, 55, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, S. On the challenges of cross-national comparative media research. Eur. J. Commun. 2003, 18, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lynnerup, N. Endperiod demographics of the Greenland Norse. J. North Atl. 2014, 7, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. (Eds.) Panarchy: Understanding Transformation in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Strohmayer, U. Historical geographical traditions. In Key Concepts in Historical Geography; Morrissey, J., Nally, D., Strohmayer, U., Whelan, Y., Eds.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Withers, C.W. Place and the” spatial turn” in geography and in history. J. Hist. Ideas 2009, 70, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J. Archaeology and Modernity; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shapin, S. Placing the view from nowhere: Historical and sociological problems in the location of science. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1998, 23, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, I. Archaeological Theory in Europe: The Last Three Decades; Routledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. Theory and Practice in Archaeology; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).