Abstract

The great megalithic sites reveal an extended use of their monuments. In Late Prehistory, in Protohistory, and even in historical times, dolmens remained visible references on the landscape and were central for navigating it. The megaliths of Menga, Viera, and Romeral provide quality data to confirm their continued relevance. Our aim here is to understand whether menhirs also played that role, using the area of Tierras de Antequera, which is connected to the sea, as a case study. With that goal in mind, a research project has been initiated through intensive archaeological field surveying, combined with the collection of testimonies from oral tradition and other archaeological tools such as GIS, geophysical prospection, photogrammetry and RTI, for the detection of engravings and paintings on some of the located landmarks. We present in this paper the first geological analyses in the megalithic territory of Antequera to determine the raw material of the menhirs that are studied and the geological outcrops from which they come.

Keywords:

megalithism; menhirs; dolmens; geological provenance; late prehistory; oral tradition; land survey 1. Introduction

The Neolithic period in Europe has been characterised by the presence of large stone monuments. The most visible elements are menhirs, which, when arranged in varied ways—in lines (alignments) or in circles (cromlechs)—are inseparable from megalithic territories ([1,2,3] among many others). Their wooden counterparts are classic examples of Northern European Megalithism, likely due to the preservation advantages of organic material in this area. Both in stone and wood, megaliths and menhirs are interpreted as monuments of high social significance, products of a collective effort and visible elements of ancestral memories.

The “buildings” made of menhirs have Stonehenge’s record as a necessary reference about the long chronologies of these sites. Feasting events, as well as burial practices, display long-term dynamics, as evidenced by the updated archaeological information from Corsica, Switzerland, Italy and Iberia. Some archaeological contexts confirm that in more instances than generally assumed, these are still an occurrence in the Iron Age and even feature historical occupations [4,5,6,7,8,9].

Current research leans towards a dynamic reading of the megalithic phenomenon thanks to new quality data from some sites along the Atlantic façade. Updated reports about megalithic decorations have been able to date these coal pigments through C14 [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

The megaliths, understood as places of social aggregation, show transformations that reveal complex biographies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Their functions have been interpreted from various theoretical perspectives: the historicist views that highlight their religious associations, on one hand, and the more processual approaches, on the other hand, that point to an array of meanings, among which social cohesion is one of the most significant.

We are able now to infer how the visibility and physical materiality of large stones acted as a widespread way to recognise megalithic territories from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. Throughout historical times, oral and written sources about the role of large stones inform us of their relevance. However, we have scarce information on the chronologies of these stones that continued to be essential to understand/navigate landscapes. Their prominence must have been linked to cultural structures that preserved a memory of their ideological, visual, and material power [25].

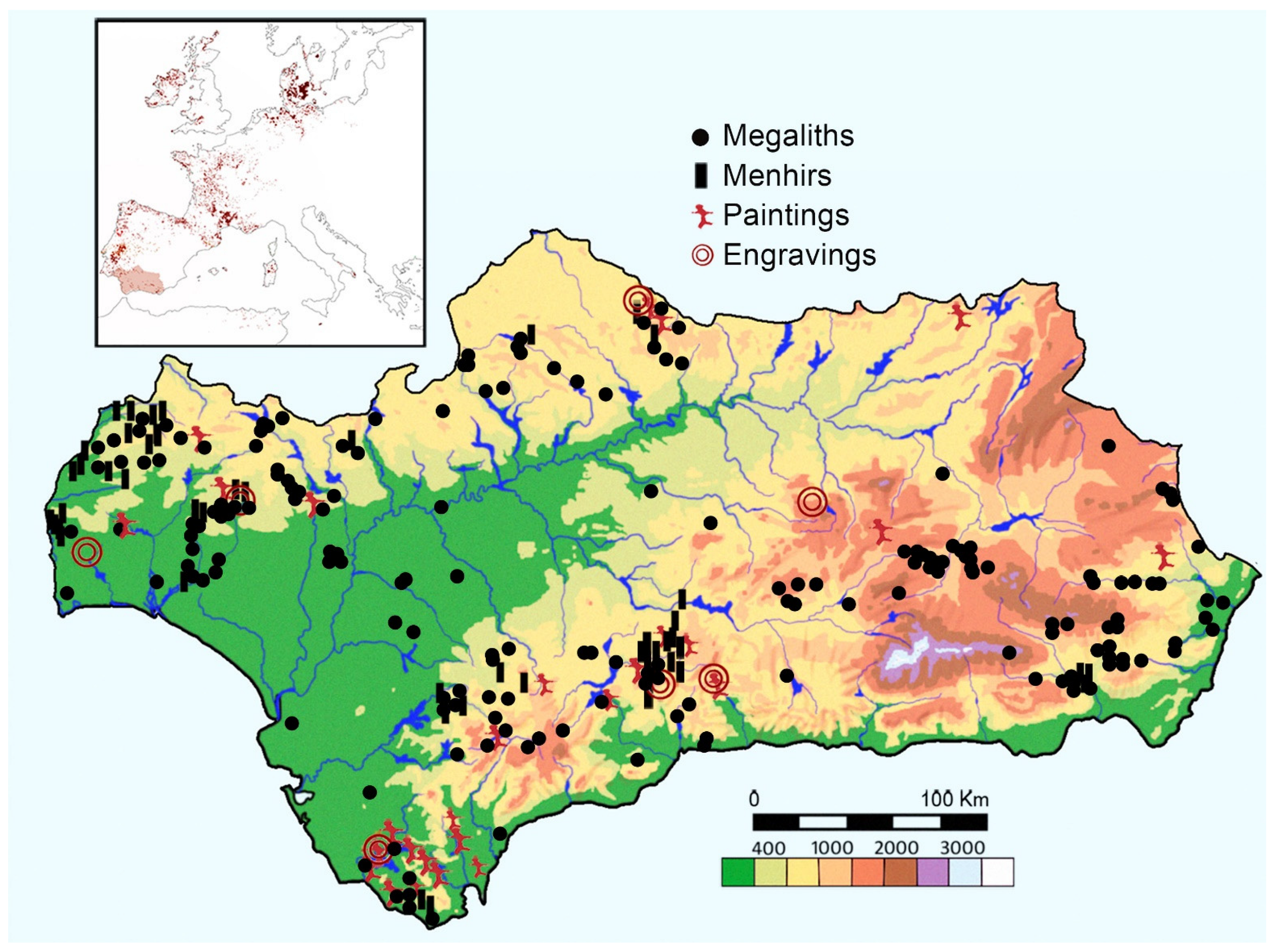

This question is more relevant in those places where emblematic megaliths display prolonged biographies that confirm a constant presence during protohistoric and historic times. This is the case of the dolmens of Antequera, which belong to the intense megalithic occupations of Southern Iberia. Territories marked by paintings and outdoor engravings, settlements, extractive activities, dolmens, and menhirs reveal one of the most outstanding demographic panoramas in Southern Europe [26,27,28,29,30,31,32] (as seen in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Megaliths in Europe, according to Laporte and Bueno [33]. Painted rock shelters, engraved rocks, menhirs, and dolmens in Andalusia, including results of this survey.

Some of the questions posed by our research trial, whose initial results we present in this paper, are investigating if menhirs are part of routes that may have been prehistoric in origin or if they were erected to perpetuate ancient stones; understanding their geological environment; and opening new research possibilities on rock engravings that could be visible messages within these supports. A fundamental base of this work consists of confirming the effectiveness of relying on oral tradition for the knowledge and detection of menhirs, dolmens or ancient structures of any kind. The results of the geological identification of the new documented menhirs and their outcrops are the first scientific data in Tierras of Antequera that confirm sources of supply for this kind of support.

1.1. Menhirs in the Megalithic Landscape: State of the Art

It is generally assumed that, throughout the European Atlantic façade, menhirs represent the first phase of the oldest megaliths, only in Brittany [34]. But the rest of France has seen a notable increase in its inventory, mostly in the centre and south. This has confirmed an unprecedented panorama of well-sized supports, some decorated and recycled to build megaliths [35,36]. On the continent, Swiss and Italian alignments are characterised by their human representations, which were also later repurposed to build megaliths [4,37,38].

There is a certain idea that in Northern Europe menhirs avoid human images, whereas these are central to megalithic sites on the continent, including Iberia and the main Mediterranean islands [39]. Equally, some wooden references, such as the post of Maerdy [20] or the large wooden post holes found in multiple henges from the Neolithic of the British Isles, suggest a rather expanded representation of organic raw materials that have not survived [40]. Reviews of these wooden posts will eventually provide data on their “dressed” decoration, as has recently been suggested for the cromlech of Pömmelte, in Germany [41].

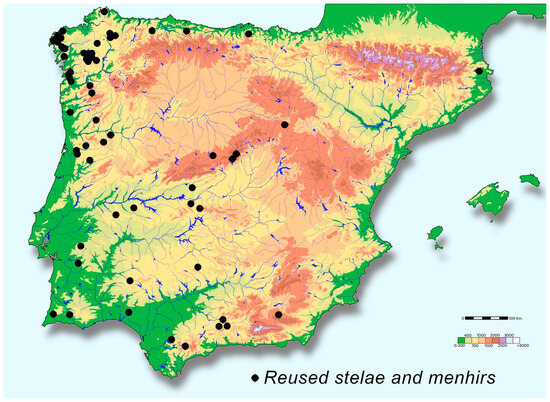

Another idea that has ruled the interpretation of menhirs is their maritime geography. This is inseparable from the assumption that megaliths are evidence of their own dissemination in Atlantic contexts, akin to the hypothesis an Atlantic pioneer group proposed since the early discoveries in the 19th century [42]. Conversely, Iberia, like some areas of France, shows a continuum of hinterland megaliths that spread across the entirety of its territory [43]. In fact, some of its maritime areas are documented to have a smaller number of menhirs. They are scarce in Galicia and northern Portugal, considering their rich megalithic contexts, one of whose components is the demonstrable reuse of previous stelae and menhirs. Other sectors stand out for the quality of their records, especially Catalonia, the Basque Country, La Meseta [44,45,46,47] and some southern territories [48]. Their absence in the southeast has been assumed, but just like in the previous case, we know of their reuse in megaliths and habitation sites [49,50]. This opens a future research field with very likely positive results.

Without a doubt, the most similar menhirs to the Bretons are in Iberia (as seen in Figure 2). They share sizes, volume, and weight, as well as a confirmed antiquity by their reuse in the construction of the oldest megaliths. In their oldest versions, they also share themes (human representations accompanied by hand-held axes and rods), in addition to the bas-relief technique. Their persistence also continued in the construction of megaliths from the 4th and 3rd millennium cal. BC. in the refurbishment of their decorations, in their prolonged funerary uses, or in their later inclusion in monuments from the 3rd and 2nd millennium cal. BC [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. With the available information, menhirs are not mere witnesses of the preceding phase to megaliths, nor did they disappear afterwards [58]. On the contrary, they are part of a diachrony of large stones throughout Late Prehistory, Protohistory, and History.

Figure 2.

As in Breton megaliths, Iberia has stelae and menhirs reused to build ancient dolmens. Megalithic sites with recycled supports actualised from Bueno Ramírez et al. [20].

The most prominent focus in Iberian historiography is that of the menhirs of the Southwest, specifically cromlechs, alignments, and menhirs at the megalithic complex of Évora. In the Algarve, these are abundant, and they are found even at the southwestern tip, where we know decorated stone conglomerates with their oldest specimens dated in the 6th/5th millennium cal. BC [59,60,61]. Recent findings at Janera (the site is still being documented), in Huelva, with over 600 menhirs, make it one of the largest sites in Europe.

Antequera was traditionally included amongst the megalithic territories lacking menhirs. Its proximity to the megalithic area of Granada brought it closer to the classic interpretation of the southeastern territories, where their presence was not acknowledged. Likewise, its distance from the western Andalusian regions relegated it, along with the rest of the Megalithism found in Málaga, to a less concentrated version of Southern European megalithic expressions.

Breuil [62] mentioned the presence of menhirs in the megalithic groups of Cádiz, from which Antequera is very close, sharing their prominence with hypogeal galleries in larger (dolmen of Menga) or smaller sizes (dolmen of la Peña). In addition to these, classic galleries occupy a good part of central Andalusia and the Portuguese Algarve in necropolises where menhirs are confirmed to have a dominant role as research progresses.

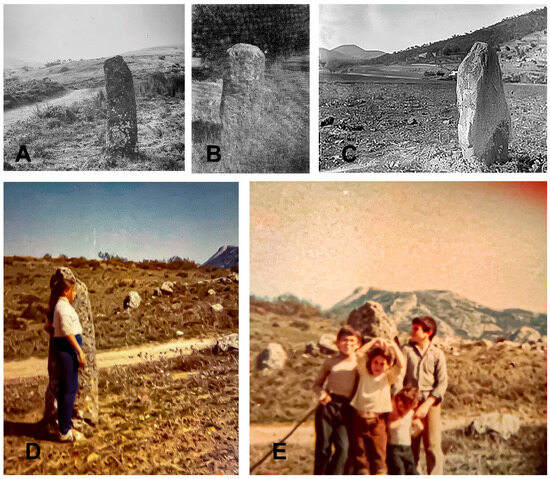

In the 1960s, the first inventory of hypogean burials in Andalusia mentioned a menhir from the necropolis of Alcaide (Antequera, Málaga) [63]. There is photographic evidence of it (as seen in Figure 6B). Next to it, and outdoors as well, an anthropomorphic engraving was mentioned, which has since disappeared. Updated records of hypogean burials and their nearby habitats have not been able to recover information about this particular menhir [64].

Since the inauguration of the Antequera Dolmens Centre in 2004 (CADA), research projects have been promoted aimed at increasing the scientific understanding of the territory that Menga, Viera, and Romeral look over. These megalithic monuments have been declared a World Heritage site.

The largest volume of menhirs is found within the archaeological ensemble itself, starting with those identified as reused supports in the construction of the dolmens of Menga, Viera, and the tholos of El Romeral [65]. On top of that, we must add all the decorated supports, also repurposed for the dolmen of La Peña (still under study). There is also increasing outdoor evidence around La Peña because of ongoing research programme [66]. In that sense, the fragment from Arroyo Saladillo or the stela from Bobadilla [26] ensures the development of these records beyond the dolmens themselves.

Outdoor expressions belonging to megalithic constructions, similar testimonies such as those from Cádiz, or the dolmen of Soto in Huelva, and the dolmens of Pozuelo 3 and 4 (a few examples with C14 dates), confirm the extended use of menhirs and reused steles in megaliths in Andalusia before the beginning of the 4th millennium cal. BC, or very close to that moment [67].

The continued oral referencing of megalithic sites from Antequera and archaeological records about temporality in the dolmens adds a reasonable argument for reading menhirs in more recent chronologies. That is why we consider it necessary to implement projects like the one we are currently presenting.

1.2. Survey Area

The Tierras de Antequera region holds a central position between the provinces of Málaga and Granada, in southern Iberia, with easy access to the mountain ranges of Córdoba. Its territory represents a major crossroads between the north and south of the Iberian Peninsula. Exhaustive knowledge of its ancient Neolithic settlement patterns [68,69] presents a rich inventory of collective burials in artificial subterranean structures and their latter reuse. These include dates from the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, as well as historical uses ([70,71,72], among others).

The high concentration of prolonged chronologies in funerary contexts, both in megaliths and collective burials, provides data on the persistence and transversality of their meaning throughout Prehistory and History. Thus, megaliths can be seen as memorials in the area. The same situation has been observed in the southeast [73,74,75], in cultural contexts where consolidated demographics supported the social strength of their identity narratives.

Archaeological efforts have been focused on the dolmens and the visible site of Peña. In contrast, the most accessible route to the sea, addressed in this paper, has never been subject to study, which explains the significant gap in information that previously existed. Along the Guadalhorce River, there is a concentration of Neolithic cave sites [69], together with more recent occupations. The connection between Antequera’s territory and the Guadalhorce mouth, including some important protohistoric and historic sites, has been mentioned in several works [76].

The study area is located in the north of the province of Málaga, in the town of Antequera, with two main geographical sectors. On one side, Vega de Antequera, with gentle elevations, and, on the other, the Sierra de las Cabras, one of the areas that define the Alta Cadena mountain range. The archaeological prospecting zone covered an area of about five square kilometres, between the Sierra de Cabras and the Guadalhorce River, where there had been no references to menhirs until recently.

The relationship between megaliths of various kinds and prehistoric cattle routes is manifested in the continued maintenance of ancient paths and in their connection with water resources that are easily available and have not been as altered by human activity. This fact, along with references to their use in Roman times as routes connecting inland areas with the coast, argues in favour of archaeological research to select this territory as an object of study. These paths mostly formed the later-called royal roads, which, in our case, are of interest because they connected the lands of Antequera with the sea. The reuse of this path in a recurring way over time is a testament to ancestral routes. In fact, within the study area, remnants of a stretch of the Roman road connecting Antikaria-Malaca [77] are still preserved, through the mountain pass of las Pedrizas and la Venta de la Yedra. This route crossed the water stream of the same name, seeking flatter lands, and its section, known as the “non-royal road”, has maintained its use by connecting, through this natural passage, Antequera and its plains with the coastal area. Carlos Gozalbes Cravioto [78] already argued that the Roman roads reaching the Torcal connected Cástulo and Malaca, putting Antequera at the centre of these movements. In that sense, we need to highlight strategic interests such as its limestone quarries; its exploitation is chronologically linked to the same time period. Access to Seville was channelled through the Vereda Vieja de Fuente de Piedra.

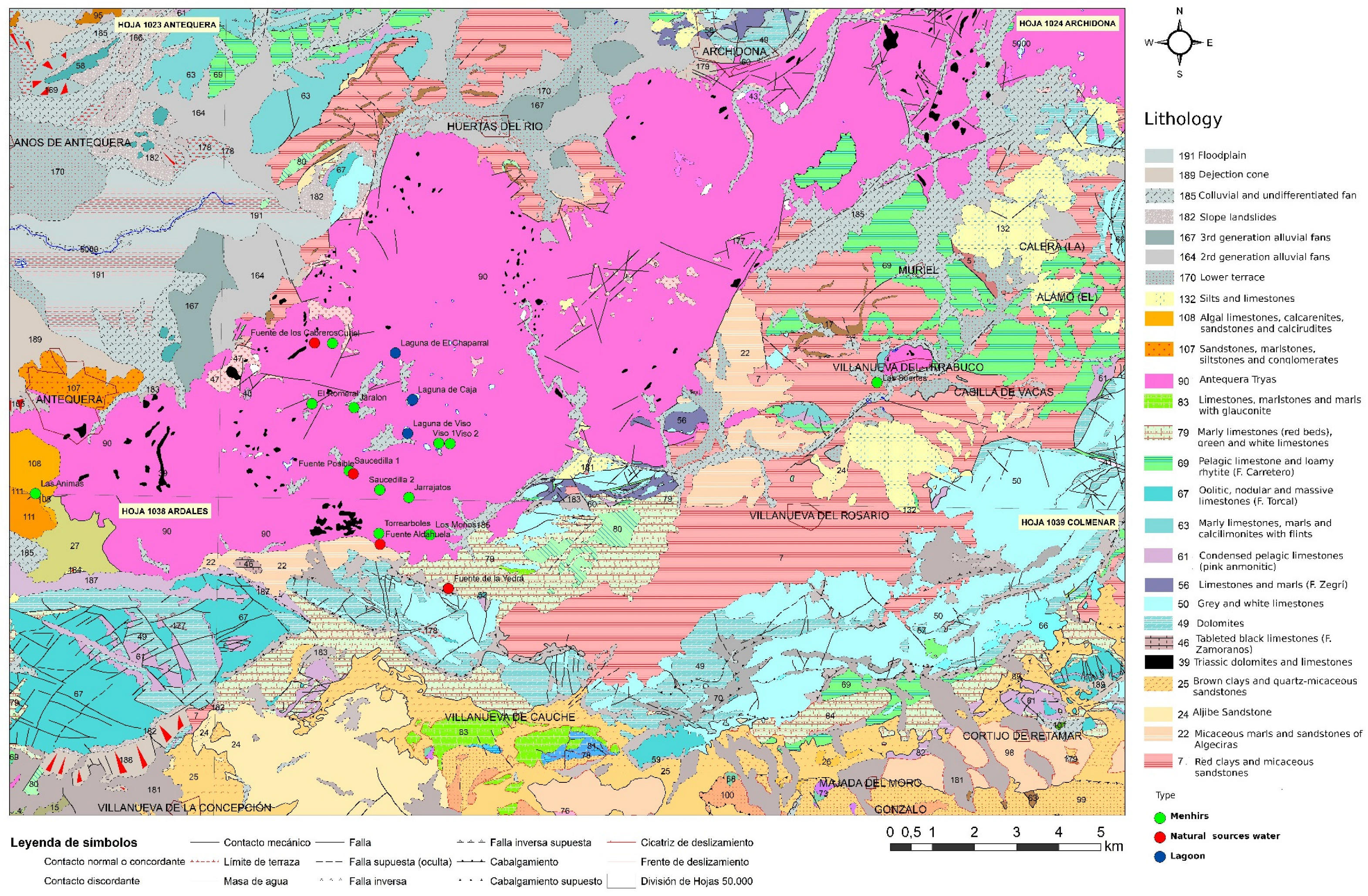

The geological context is characterised by Triassic material, known as “Triassic of Antequera” (Trías de Antequera) or “Sub-Baetican Chaotic Complex (SCC)” (Complejo Caótico Subbético) of the External Zone of the Baetican Mountain Range [79]. It consists of clays and gypsums, which form the matrix over which an olistostromic complex of carbonatic materials is developed. Therefore, these are detritico-evaporitic materials, analogous to those known as Germano-Andalusian lithologies. On this matrix, we find large blocks of limestone and dolostone. These irregular blocks constitute the rocky promontories found in and around the study area. In the topographically higher areas of the Sierra de las Cabras, more modern carbonatic materials, Jurassic limestones and dolostones are present as well. Additionally, there are other neighbouring materials that, despite not being strictly carbonatic rocks, may contain a significant fraction of carbonate materials, such as the calcarenites of the Miocene basin of Antequera.

The entire sector is rich in aquifers and wetlands. In the immediate surroundings, the Lomas de Antequera Lake complex is located, registered in the Wetlands Inventory of Andalusia (WIA). These include Laguna de Caja and Laguna de Viso [80], as well as several water springs such as Fuente de la Yedra, Fuente de la Alhajuela, and Fuente de los Cabreros, which have served as resting and watering places associated with trails and royal paths (as seen in Figure 3).

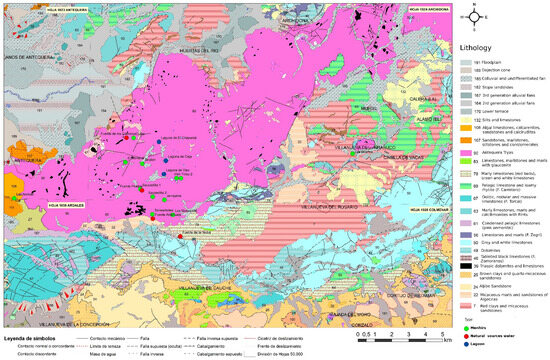

Figure 3.

Geological map of Tierras de Antequera, showing the location of the menhirs at Guadalhorce River, aquifers, and lagoons.

2. Materials and Methods

We understand that the demonstrated relationship between outdoor stones and megaliths since the Neolithic opens the discussion for the presence of long-lasting and long-standing rock milestones throughout the Lands of Antequera. In order to advance the quality of data on this topic, we ought to detect more sites and confirm their chronologies in less documented areas where no evidence has been found yet. That is the way to compute the incidence of erected or reused menhirs throughout Antequera while also consolidating evidence of their geographical continuity and their social role for human occupations in these territories.

This building work is essential for implementing conservation strategies and site management strategies that will better preserve these milestones. These are necessary to dignify and promote traditional ways of moving and connecting people, which are still trackable well into the 20th century [81,82]. To achieve these objectives, we use a combination of ancient pathways’ data, supported by oral surveys, geology, and archaeology.

2.1. Cattle Trails

The study of menhirs and megaliths in relation to prehistoric cattle routes perpetuated in the network of drover’s trails has seen various developments in the Iberian historiography [83,84,85,86]. There are megaliths mentioned in historical sources to establish property boundaries [87,88]. There are material testimonies of historical occupations, including burials [71,89,90,91]. In fact, following drover’s trails for the prospection of menhirs has been a successful strategy in the Basque Country [46] or in northern Palencia and inland Cantabria [47].

These traditional paths [92] (as seen in Figure 4 and Figure 5) are often the protagonists of an important oral heritage. Tradition has preserved the menhirs within the collective memories of livestock movement, embracing their presence and collecting them in abundant tales that have helped to navigate these movements, establish mnemonic rules about various resources, or indicate resting areas or gathering spots with other herding groups. Incorporating this ancestral knowledge into our methodology has yielded significant results.

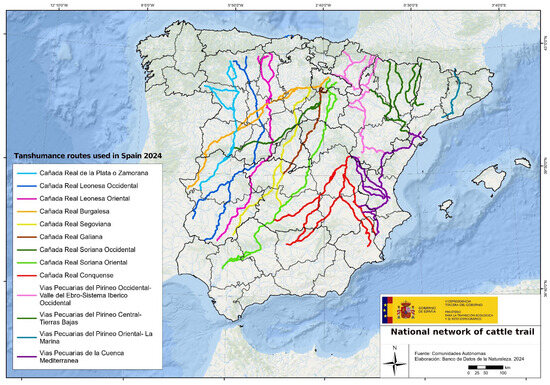

Figure 4.

National livestock route network by the Spanish ministry, according to the General Network of Livestock Routes, within the Spanish Inventory of Natural Heritage and Biodiversity.

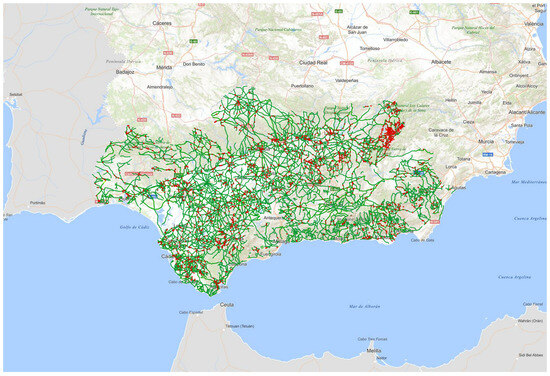

Figure 5.

Livestock routes in Andalusia. Open Acess. Rediam. Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Sostenibilidad y Medio Ambiente. https://portalrediam.cica.es/VisorRediam/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

2.2. Oral Sources

The knowledge that older individuals have of a territory is one of the best tools for archaeological research [93,94]. This fact has allowed us to delve into the discourses and narratives that are not commonly present in official sources, but rather in the collective memory. This has, in our case, been key for the discovery of new monoliths. Oral testimonies about the existing past paths have facilitated finding and tracing communication routes that enabled contact between different hinterland areas, as well as between these and the coast. Interaction with local populations through open conversations becomes a necessary tool for establishing prior working criteria, the results of which will be presented later on.

Data was obtained from a survey of men and women over 65 years old who had direct relationships with cattle-raising lifestyles (as seen in Supplementary Materials Table S1). Their testimonies were collected, emphasising memories of the most common paths, the presence of landmarks or other types of orientation and location references. Equally important was detecting aspects of seasonal dynamics in livestock life, such as their routes, origins of other groups with whom they also moved, songs, and storytelling practices. All the information collected will be preserved at the Dolmens of Antequera Interpretation Centre.

In some cases, oral history links ancient stones with personifications and particular events. We even collected graphic references to these ancient stones in the collective imagination, such as frequented places. This is the case of the stone boy menhir, now disappeared, which was found in Cuevas de San Marcos, or the standing stone of Torreárboles, in Antequera. Originally in Torreárboles (as seen in Figure 6A), there were two stones, according to the collected testimonies: one of them was destroyed approximately in the 1970s, and the documented one was displaced from its original location due to agricultural works. This landmark was referenced by the Málaga researcher Carlos Gozalbes Cravioto [94] in his work on the Roman roads of Málaga. Here he states that, due to its characteristics, it had to be an older landmark than the Roman remains he was studying (as seen in Figure 6D,E).

Figure 6.

Old photographs of disappeared menhirs from the Antequera megalithic site: (A) Torreárboles menhir in the original location; (B) menhir from the necropolis of Alcaide, Antequera, according to Berdichesky [62]; (C) Piedra del Diablo menhir, taken by Manuel Gómez Moreno. Rodríguez Acosta Foundation, Granada; (D,E) Torreárboles landmark, in its original position, recorded by Gonzalbes Cravioto in 1986 [95].

2.3. Written Sources

Given the possibility that some monoliths had historical relevance, documents from the municipal archive of Antequera and Málaga were consulted regarding land distribution and boundaries in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. This allowed for the identification of documents describing the sale of part of a land marker by Martín de Rojas y Padilla with mentions from 1645, the file on the boundary measurements of Cauche from 1590, and the boundary marking for mares and foals’ pastures by livestock breeders from 1748. All of these are related to or near the area of study. According to these documents, land marking was carried out with loose stones and natural elements. That means that descriptions do not correspond with menhir typologies in our project, at least in the consulted documents.

Old documentation and early works developed at the Interpretation Centre of the Dolmens of Antequera and its surroundings, especially from the 19th century, have been key to identifying some elements that had previously gone unnoticed.

An example of this is the work by Aguilar and Cano [96], regarding the antiquities of Campillos. This reference mentions two menhirs, found in the medium part of the Guadalhorce River, which were close to two tumuli that, according to the authors, could be prehistoric. The text states: “following the aforementioned tumuli in importance, a menhir located near the Juagazares”. Of great height, placed on the highest part of the land, its base had worn down significantly, and due to this reason, it was easily toppled. Diego Gómez, the owner of the land, conceived and executed this, breaking it into pieces immediately, without thinking that he wanting some miserable stones meant he was destroying an ancient and irreplaceable monument. Another menhir of smaller dimensions still remains at the foot of the “Juagazar hill”. This last-mentioned menhir has not been located.

Another document is an image preserved in Gómez Moreno’s collection, from the Rodríguez Acosta Foundation archive, Granada. It is a photograph of a menhir from Antequera, known as the devil’s stone (as seen in Figure 6C). This menhir has not been relocated, but it is an excellent example of the presence of these elements. It is also an example of how these artefacts have received little attention, even though they are comparable to those found in the archaeological intervention we describe in this paper.

2.4. Intensive Field Surveying

The objectives and strategies to be followed, as well as the developed methodological applications, were influenced by the orographic and vegetation conditions of the study area, with favourable zones for verifying oral information.

Fieldwork focused on areas with a high likelihood of findings, close to sites mentioned by oral sources obtained through the surveys. Prospection works were carried out along linear and parallel paths with trajectories covering 10 m in width to cover the entire surface of the terrain. Each participant could oversee about 5 m on each side in cases where the terrain’s topography was easy and presented no visibility issues. It is important to mention that the study area does not show anthropogenic alterations due to agricultural activities since most of the prospected area corresponds to a protected Dehesa, with large tree-covered surfaces of holm oaks mainly intended for horses and Lidia bulls.

Once the supports were detected, we proceeded with an even more intensive prospection in the immediate radius, 100 m around, moving out in concentric circles from the area closest to the menhir. Findings have been geo-referenced and mapped to understand concentrations. Those sites where the concentration of prehistoric artefacts is greater were combed with ground-penetrating radar to detect possible structures. It is the case of the already well-known menhir of El Chorro, where prehistoric materials are visibly concentrated, as well as the structures on the surface. Its proximity to the Tajo de los Cabritos rock shelter, where schematic art was found, suggests a coherent set in itself and with land occupation patterns that fit seamlessly into the Neolithic panorama.

In the field surveys, a precision GPS was used, georeferencing any point of potential archaeological interest through both horizontal (UTM coordinates) and vertical (absolute elevations measured relative to sea level) readings.

2.5. Documentation of the Ground Milestones

The general methodology to approach the study of the menhirs, from the prospection, the inventory of new items, and the geological determination of their origin, is disclosed in this text. A second phase which is in process will be dedicated to studying their surfaces to assess possible representations and to the analysis of their distance relationships, lower-cost roads and visibility between supports and other territorial and cultural references by GIS methodologies.

Each find has been documented through photography and photogrammetry, obtaining 3D models for a detailed study, which confirmed some decorations of interest.

Around the monoliths that showed traces on the surface or possible decorations, we initiated a second phase through test excavations. These yield OSL and C14 samples.

During the archaeological excavations, photographs of all surfaces were taken in various settings, with natural and artificial light. Likewise, details that provide information on types of engravings, applied techniques, and themes were recorded. A camera such as this has been used with various lenses and filters, as well as portable cold lights that can change their shades from white to yellow. Three-dimensional photogrammetry was carried out using a Nikon D750 camera and processed by the Agisoft Metashape professional software. The most accurate shots were edited in Adobe Professional, generating an enhanced image that captures the most comprehensive representation of the piece [13]. The information provided by this “restored” picture was then added to the date provided by photogrammetry, which allowed for zooming in on the image to detect all traces of engraving [36].

2.6. Collection of Geological Samples

Once all menhirs were documented, their geology became a priority. This information allows us to understand routes to the raw material sources and to integrate compatible rock outcrops in our field surveying. Geological information determines which rocks are used and facilitates their comparison with possible sources of origin. This project obtained an inventory of thin-section analyses, sampled from archaeologically relevant supports as well as outcrops, that constitutes an outstanding scientific repertoire in itself. This will be housed in the Interpretation Centre for the Antequera Dolmens to have comparative geological collections from the Tierras de Antequera available for consultation.

The work has been carried out in stages: the field surveying, involving the collection of thin-section samples, and the laboratory stage. In situ geoarchaeological sampling was conducted systematically at the markers and the nearby comparable carbonate rock outcrops. The possibility of comparing samples between artificial supports and their source of rock has been a first-time contribution of this project in the Tierras de Antequera, mostly considering the depth of data that we typically have on this sort of evidence.

A total of 16 thin section samples has been analysed. Eight of them are from markers, and the other eight are from nearby outcrops, all taken in situ. All samples were cut and prepared at the Department of Mineralogy and Petrology at the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Granada. Samples are 5 × 5 cm in dimension to protect their integrity and the donors’. They were collected in relatively low areas or areas with little visibility. Once gathered, stratification was indicated for cutting, and they were subsequently labelled and stored in bags for further treatment. Samples were named after traditional site denominations, distinguishing with an A the ones taken from the corresponding nearby outcrops.

Each of them was prepared with Alizarin red dye, polished and dried with lacquer. Alizarin red dye allows for the visual distinction of calcite [CaCO3] and dolomite [CaMg (CO3)2], the main minerals constituting limestone and dolostone. Analysis was completed with a specialised magnifying loupe and diluted hydrochloric acid (10%) to help differentiate between limestone and dolostone. All thin sections are the same size, 28 mm by 46 mm, 30 microns in thickness, to fit the microscope. The model of the microscope was an OLYMPUS BX51 attached to an OLYMPUS DSLR camera (Olympus Corporation; Tokyo, Japan), the device responsible for all pictures in this paper.

3. Results

3.1. Documented Menhirs

The tested area provides evidence for implementing the use of oral sources to improve results for intensive surveys with this paper’s research objective. Most of the documented monoliths were known by those who are currently part of the cattle rancher community, while they remained opaque in the archaeological record. Some of these landmarks served as boundaries and have been preserved and erected to this day.

The detected monoliths are concentrated along the foothills of Sierra de las Cabras, in the southern part of the study area, where some rocky promontories are locally found, rising above the surrounding terrain. There are also some dolines, or small isolated depressions, coherent with the evolution of karstic relieves around Trias de Antequera [97]. They are mostly spread along the trail of Cuevas Bajas–Colmenar (also known as Realenga Málaga to Loja and Torre del Mar) and the trail Antequera–Villanueva del Rosario.

Each menhir’s visibility is different not only due to their preserved height but also because of their shape and volume. Their image projection suggests a set of consistent profiles, rectangular with gently rounded edges, while more oval shapes with finer sections are scarce. If we contrast these profiles with their position on the landscape, the “smaller” ones are situated at the foot of a slope, very close to ancient paths, and sometimes they retain part of their tumulus. Other and bigger shapes are less common and are positioned farther away from the path.

In general terms, there is a noticeable relationship between where the monoliths are located on the ground at similar topographic elevations. This apparent spatial distribution could be consistent with the layout of some type of route that, with different purposes, may have been part of the ancient landscape. Its relevance could have persisted over time, given the proximity to some historical transhumant paths. Similarly, some of the monoliths are located close to water points, whether there are springs or small lagoons. The latter is rather common in the Triassic due to the abundance of evaporitic facies (gypsum and salts), which lead to sinkholes and small springs, sometimes saline, that are frequently visited by wildlife and livestock (as seen in Supplementary Materials Table S2).

The presence of evaporitic rocks is even greater at depth, generating karst cavities and sinking and raising movements, due to dissolution and halokinesis, respectively. Recent data obtained from the Copernicus satellite shows a widespread uplift of a few millimetres per year, as well as some specific areas (possible sinkholes) with significant subsidence. These movements may have influenced the current inclination of the monoliths on the terrain, which vary between 70 and 80 degrees.

Along the Cuevas Bajas–Colmenar ridge, associated with El Romeral tholos, there is a significant number of grouped menhirs, all unpublished. Ten monoliths to whom another reused menhir should be added, the one indicated in the initial studies of the megalithic site [26], as well as those reused found in Menga and Viera. They are aligned and distributed continuously between the central area of Tierras de Antequera and the exit to the sea, all sheltered at the Sierra de las Cabras foot. Their orientation makes them more visible under certain solar incidents (i.e., zenith and fall), and their visibility also shows noteworthy differences.

With rectangular profiles, some have engravings aimed at highlighting human figures: highlighted heads or outlined shoulders, narrowing of the waist, and even slight reductions in width towards the lower area that draw static legs. Only one of the artefacts is markedly cylindrical, and its use as a Roman milestone may be the reason for removing the upper part of the support, making it impossible to assess the entirety of its profile.

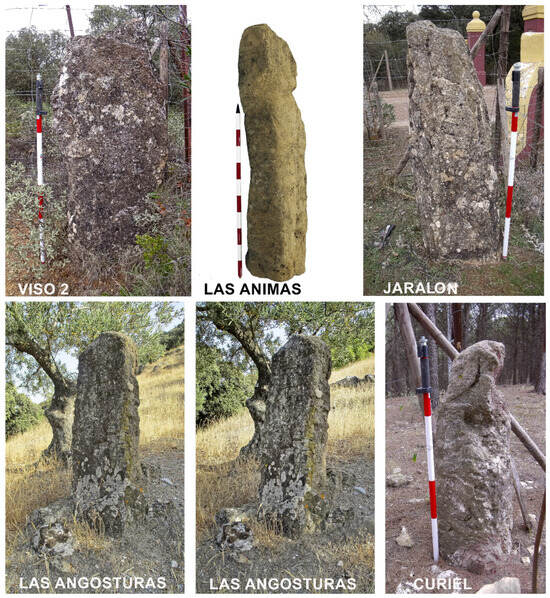

Based on each of the menhir’s characteristics, we can establish that their extraction was carried out manually. In the case of those with a truncated conical typology, such as the El Romeral menhir (as seen in Figure 7), the one from Jarrajatos (as seen in Figure 7), or the one from Curiel (as seen in Figure 8), no smoothing/polishing work is observed, as the natural shapes of the rock remain. In those with a rectangular typology, such as that from Jaralón (as seen in Figure 8), they exhibit slight surface treatments, which may relate to the geological characteristics of the used rock. These are visible in the form of spurs, including fractures that facilitate the breakage of complete and almost flat blocks.

Figure 7.

Romeral (menhir 1), Saucedilla 1 (menhir 2), Saucedilla 2 (menhir 3), Saucedilla 2 reverse (menhir 3), Jarrajatos (menhir 5), Viso 1(menhir 8).

Figure 8.

Viso 2 (menhir 9), Las Animas, Jaralón (menhir 12), Las Angosturas, Las Angosturas, Curiel (menhir 10).

At least two nearby locations add another two pieces: Saucedilla (as seen in Figure 7) and El Viso (as seen in Figure 7 and Figure 8), similar to Tajo de los Cabritos. Las Angosturas (as seen in Figure 8), Las Suertes and Las Ánimas (as seen in Figure 8) add three isolated testimonies that expand the possibilities of identifying monoliths, totalling fifteen supports. We must add to this list the missing one from Alcaide, the destroyed one, along with the one documented and described by Gozalbes Cravioto in Torreárboles and the devil’s stone mentioned by Gomez Moreno (unknown location). That means we would be talking about a total of eighteen monoliths, most of which are unpublished.

The pieces identified on the surface during the survey, mostly small fragments of hand-made ceramics and flint blades, helped locate two more supports (Caballo and Chorro) with possible prehistoric chronologies. The proximity and topographical relationship of the menhirs of El Chorro with Neolithic cave sites [69] (p. 55) suggest new interpretations for this area. Data imply that this is a site that requires an integration of inland enclaves with access to the sea in Late Prehistory, similarly to what has been proposed for other geographies in Andalusia and Algarve. Historically, the most recent peak in social activity in this area is related to Phoenician and protohistoric indigenous occupations, as well as Roman and mediaeval settlements. The Las Ánimas support, or the one from Jarajatos, points to those types of chronologies [98].

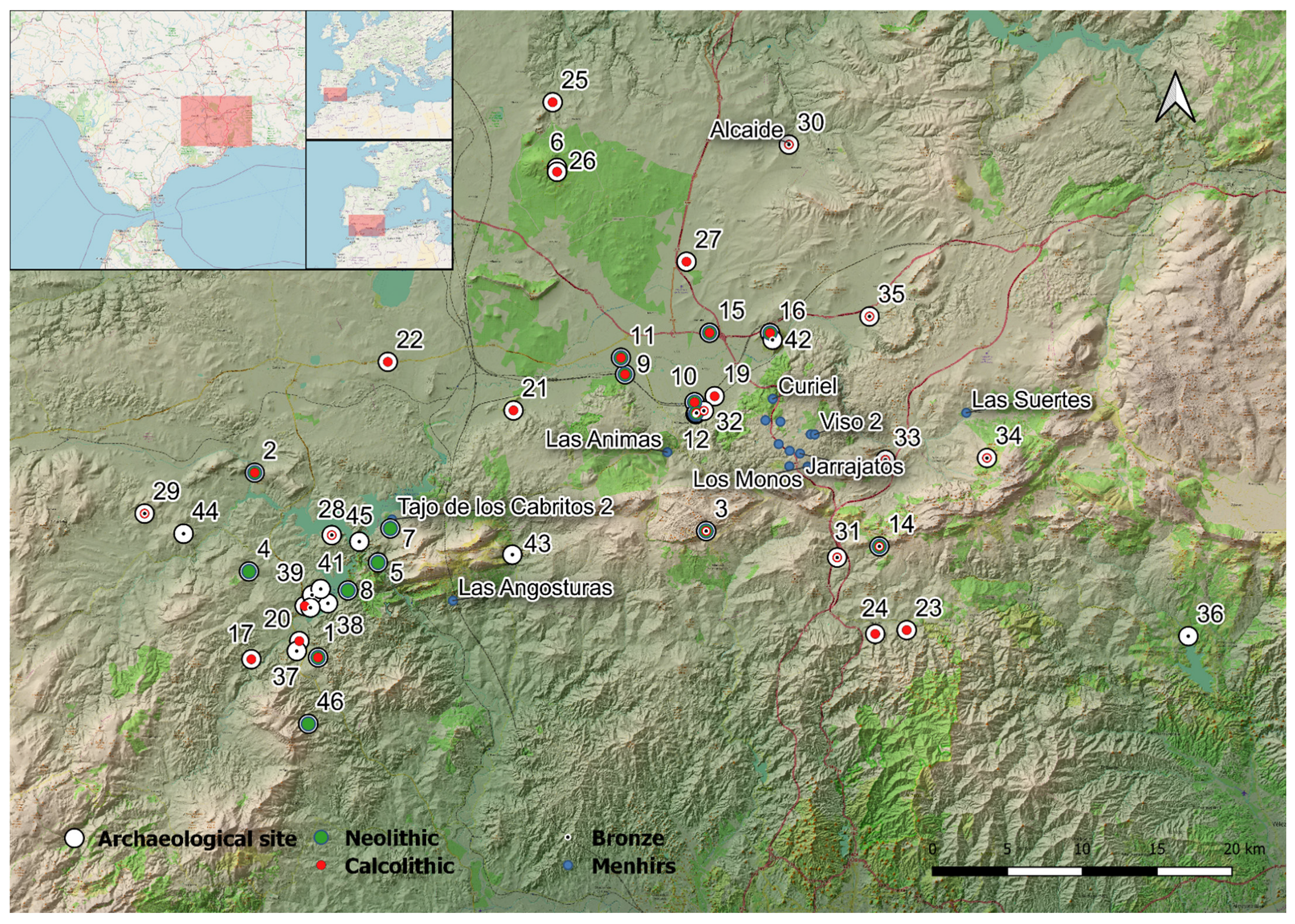

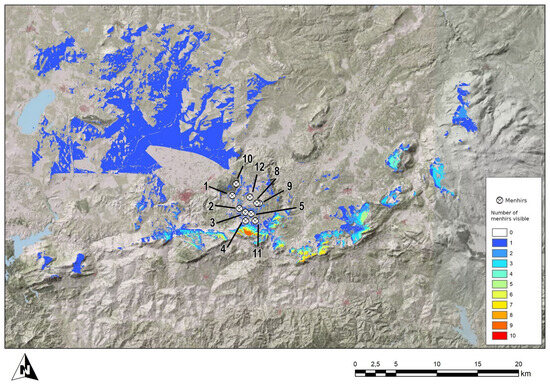

The information obtained on the location of the landmarks has been included in a Geographic Information System (GIS) to configure new cartography in accordance with the needs of research, heritage management and municipal urban planning. Visibility analyses were established for each of the menhirs, merging the data into a single figure. Visibility analyses of the studied landmarks, considering possible vegetation variables and also using the contour lines and the altitude of each of the menhirs located, suggest a clearer view from the south (as seen in Figure 9). This coincides with the passageway through the Las Pedrizas port, which accesses the Vega Antequerana, where the three dolmens of Menga, Viera, and El Romeral are located. Furthermore, landmarks are situated in areas where current royal cattle trails were laid out and the terrain is flatter, with occasional small hills. This is the preferred location for setting menhirs up. Their position reflects a pattern that usually focuses on elevations around 700 m above sea level.

Figure 9.

Visibility areas of the discovered monoliths: 1. El Romeral, 2. Saucedilla 1, 3. Saucedilla 2, 4. Torreárboles, 5. Jarrajatos, 8. Viso 1, 9. Viso 2, 10. Curiel, 11. Los Monos, 12. Jaralón. Compiled by Francisco Marfil.

Although it is complex to understand the population dynamics in this environment, the concentration of monoliths in a relatively small space highlights the possibility of a habitat. Settlements would probably be close to paths used since the Neolithic and documented in Roman times, also associated with abundant water resources and fertile areas for farming and grazing. Research has always focused on the menhirs in the Antequera plain, due to their links to Menga and to Peña de los Enamorados. However, the location of every other menhir possibly allows for the unprecedented extension of our records.

3.2. Menhirs and Quarries: Thin Section Samples Results

As we detected new supports, we searched for their possible quarries. Once located, thin section sampling was carried out on the support, as well as their possible source, to establish a coherent database. Petrographic characteristics allow for the comparison of samples from the monoliths with those from nearby rock outcrops. These generally show a great compatibility between the geological and archaeological samples.

From the set of samples detailed in Table S2, the majority are Triassic dolomites, which are very common in the study area. These dolomites come from disorganised and dispersed outcrops, embedded in the abovementioned “Triassic of Antequera” or “Sub-Baetic Chaotic Complex” of a tectosedimentary and olistostromic nature. We may conclude that most of the monoliths were sourced from proximity raw materials. This trend overlooks other materials of equal or better quality, but whose outcrops are farther away. Additionally, there are better-quality rocks present in the same Triassic outcrops, such as ophites, subvolcanic rocks of high hardness, but they are more difficult to quarry and engrave.

The careful selection of materials, demonstrated by the study results, also reveals a systematic method of rapid and pragmatic sourcing, as if raising these supports were part of a scarcely sophisticated everyday activity. Comparative thin-section analyses confirm total compatibility between artefacts and rock sources. Carbonate classification followed Folk’s work [93] and, in some cases, Dunham’s [99]. Identified characteristics allow us to compare samples, as they appear to maintain the same general lithology (as seen in Supplementary Materials Tables S3 and S4).

El Romeral menhir and its corresponding outcrop sample, named 1A, are very similar. The monolith from La Saucedilla 1 and its outcrop 2A exhibit a very fine and homogeneous grain, which may indicate that they are as well compatible in their origin. The one from Saucedilla 2 and the geological sample 3A show a similar grain size and recrystallisation, compatible with a common origin. The Jarrajatos menhir, along with the samples named Junto 5 and Junto 5-2, show significant textural differences, especially Junto 5, which has a much larger grain size. These differences may be due to variability within the formation itself. They could also be the result of a different source. The El Viso 1 monolith and the geological sample 8A are also texturally different, and it cannot be concluded that they are from the same outcrop. However, the two monoliths, Viso 1 and Viso 2, are similar in both texture and crystallinity. No geological sample was taken from Viso 2, as the nearby outcrops were of the same type as the one collected for Viso 1. Lastly, the menhir of Curiel and sample 10A are similar, with both being highly recrystallised and having a mosaic textural pattern, consistent with a shared provenance. The Jaralón menhir and sample 12A, although they exhibit different textures, could originate from the same outcrop, given that the grain size and crystallinity are comparable.

These geological and petrographic analyses on both rock outcrops and menhirs are of great interest. Furthermore, they are subject to further developments of broader scope, such as geological mapping of certain sectors, detailed inventories of water sources and their hydrochemical characterisation, or detailed topographic and geomorphological analysis in relation to the monoliths’ position.

4. Discussion

In the past, Tierras de Antequera and its network of ravines, paths, and roads were part of “La Extremadura”. This defined a horizontal strip of the Iberian territory, from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, through which people and livestock moved seasonally. Oral surveys have confirmed that these movements, which involved contacts with groups of Portuguese shepherds, continued to exist in a residual way until the present day. They still preserve memories of songs, stories, and customs [100]. Longitudinal transits along the Cañada Soriana Oriental facilitated movement towards the west, passing through Extremadura, while the Cañada Conquense traversed the mountains that flow towards Levante, reaching the Ebro valley.

Regarding ancient societies, oral sources are essential for the recovery and valorisation of cultural heritage. Although these narratives have a heavy social weight, their interpretation allows us to recognise collective memories surrounding archaeological materials. In fact, its building process may manifest a connection to ancestors from a very distant past [25] (p. 3). It certainly constitutes a heritage value in itself [101,102,103,104].

This paper’s research demonstrates the reliability of these testimonies to recover information about itineraries. This relates not only to prehistoric shepherds but also to communication routes and relationships between these and settlement sites through the inclusion of territorial markers (i.e., menhirs, dolmens, and sites with rock art). They could also have a symbolic character that connects the occupied and traversed places for the groups that created and maintained them [105] (p. 93). Stones acquire value due to their biography, which explains their movement since the Neolithic, from older places to be incorporated into a new monument. These events can be tracked, particularly in supports with engravings and paintings that possibly capture oral histories.

Prior to our research, the reduced presence of menhirs in the Guadalhorce was notable, despite the remains located in this area and the large volume of studies conducted at Tierras de Antequera. These are areas that have not received much attention, even though their situation as crossing enclaves between mountainous zones makes them prime locations.

Our results have added ten unpublished menhirs. Alongside these, it is necessary to mention other detected monoliths during our study, thanks to the testimonies collected. We refer to the menhirs of Las Ánimas (Antequera), Las Angosturas (Valle de Abdalajís), documented thanks to the chronicler Fernando Bravo from Cártama, and finally Las Suertes (Villanueva del Trabuco). Our contribution is also the menhir of El Chorro, currently housed in the Dolmens of Antequera Interpretation Centre, beside which we documented a semi-buried piece that is considered a probable menhir. There is another one that has disappeared from Alcaide and was documented by Goméz Moreno, and there is, as well, the one that, according to oral tradition, was next to the Torreárboles menhir.

Similarities in size and geology between the vanished menhir from the necropolis of Alcaide and the one from Romeral, unpublished until this publication, allow us to approach pieces that were considered lost or disqualified due to their insufficient context. The number of documented menhirs is surprising, as a systematic study in this sector had never been conducted. If we add our contributions to the general Tierras de Antequera menhir record, previous hypotheses that distanced Andalusia’s hinterland from the presence of menhirs stands debunked. Thus, Antequera presents itself as a very suggestive environment to understand the relationship between large and small dolmens and previously used as menhirs stones. This landscape is also outstanding for inferring the biography of menhirs and their role in marking routes and paths that channelled interactions with other territories, from Prehistory to almost the present day.

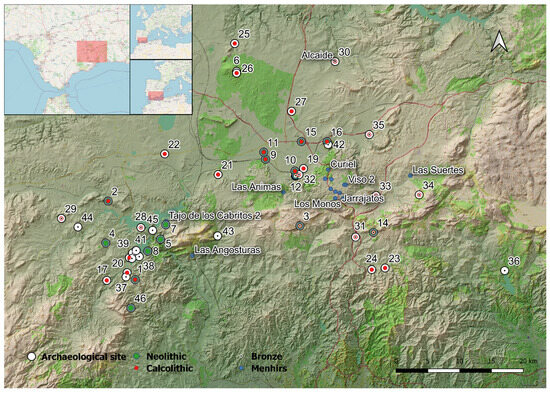

All unpublished menhirs included in this text, positioned on access roads to the sea, add another unexpected argument of enormous significance for drawing the broad range of connections in the Antequera region (as seen in Figure 10). Late Prehistory ports or shelters in the southern estuaries of Iberia have been relevant in recent years’ discoveries [106]. Research in Alcalar, Valencina, Janera, and now Antequera [18] (p. 33) [7,107] opens possibilities to follow movement not only across the Atlantic but also in the Mediterranean and African contexts. Furthermore, it integrates Antequera within the sites with confirmed extensive interactions during the southern European Late Prehistory.

Figure 10.

Map of menhirs and Late Prehistoric sites in the interior territory of Málaga. Created with QGIS 3.2. Cartography from OpenStreetMap (OSM Foundation—Open Data Commons Open Database Licence), Digital Terrain Model 2016 (hypsometric colours), Shaded Relief 2016 (Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalucía—Junta de Andalucía). 1. Cueva de Ardales; 2. Sima de las Palomas; 3. Cueva del Toro; 4. Cerro La Higuera; 5. Abrigo Gaitanejo; 6. Cueva de la Higuera; 7. Tajo de los Cabritos; 8. Puerto de las Atalayas; 9. Arroyo Saladillo; 10. Huerta del Ciprés; 11. Cortijo Quemado; 12. Dolmen de Viera; 13. Dolmen de Menga; 14. Cueva de la Pulsera; 15. Colina de los Olivos; 16. Piedras blancas; 17. Castillo Turón; 18. Cortijo San Miguel; 19. Tholos El Romeral; 20. La Galeota; 21. Cerro del Cuchillo; 22. Cerro del Comandante; 23. Peñas de Cabrera; 24. Cerro García; 25. Recinto foso Alameda; 26. Abrigo de los Porqueros; 27. El Silillo; 28. Necropolis Aguilillas; 29. Necropolis de la Lentejuela; 30. Necrópolis de Alcaide; 31. Aratispi; 32. Cerro Marimacho; 33. Dolmen de El Tardón; 34. Peñon del Oso; 35. Peñas Prietas; 36. Cerro Capellanía; 37. Peña de Ardales; 38. Morenito; 39. Raja del Boquerón; 40. Las Grajeras; 41. Lomas del Infierno; 42. Peña de los Enamorados; 43. Cementerio Alto; 44. Los Castillejos Teba; 45. El Castillón de Gobantes; 46. Sima de Curra.

Transit of animals and carriages along these roads was common in the twentieth century, preserving ancient itineraries. Roman roads were transformed into droves, pathways, or trails, allowing communications through these mountain passes. This is the case of the so-called Roman road IV from Malaka to Antikaria, a route that, according to the Anonymous Ravennatis, turned Antequera into a well-connected hub during Roman times [108]. This road, which was still in use in the 20th century, and herds of cattle were moved through it from Málaga to Antequera for its livestock fair. It is noteworthy, as mentioned earlier, that the documented monoliths are located precisely in the vicinity or even on the margins of these ancient ways. Right on the trail from Cuevas de San Marcos to Colmenar, passing through Antequera, five of the monoliths stand, and three more are located on the trail from Antequera to Villanueva del Rosario. There are two others that are not directly related to a known path or trail. Different denominations for the livestock routes network in Andalucía depend on their width. Trails did not exceed 37.5 m, unlike the Cañada Real, whose width does not exceed 75 m (Law 3/1995, March 23, on Livestock Routes).

Homogeneity and a lithology related to their specific location can be inferred from the thin section analyses of both the monoliths and the neighbouring rock outcrops. In fact, in most cases, their morphology shows similarities in the stratification planes, fracturing, and layering of the sampled rock outcrops. The type of manufacture, which repeats volumes and heights, seems to reflect a relatively common systematic approach to marking lines and information along paths on this landscape.

Although there are increasingly more Iberian megaliths being analysed to determine the origin of their supports, just a few sets of menhirs have been linked to their sources in Iberia [109,110]. Conversely, our chosen methodology, combining geological and archaeological information, has been successfully applied in emblematic sites with menhirs, such as Stonehenge, and in the study of menhir and stele sets in the Mediterranean islands and the Alps [111,112,113,114]. Differences in effort and social management between moving stones from distant locations and utilising nearby resources provide a rich argument for assessing connections. They also allow us to reflect on the ways and means by which identity is being managed in megalithic territories, based on the provenance and history of the stones [115,116].

In the development of the processes of management of raw materials by prehistoric human groups, the different actions carried out in the environment in which they are articulated reflect a series of strategies whose reconstruction allows us to characterise, among other activities, the supply of rocks for the construction of megaliths in their different typologies. Studies using optical microscopy to determine the origin of raw materials in various heritage elements are common. The excellent results obtained from this type of study demonstrate the reliability and importance of this method [117,118,119,120].

The relationship between quarry areas and these unpublished supports from Tierras de Antequera reveals close ties between nature and culture, as part of an integration of megaliths into their landscapes. The duality between megaliths and the observed natural rock exploitation around their area [121,122] is, therefore, confirmed by the relationship maintained between menhirs and their nearby quarries.

Evidently, the anthropogenic transformation experienced over millennia, compounded by agricultural works or large infrastructures, has caused the alteration or even the destruction not only of menhirs or dolmens but also of rocky outcrops that could have been used as raw material sources. However, much of the study area has hardly suffered any alterations. The relevance of these elements’ locations, understood as a form of human appropriation of the environment, is that they have persisted over time as artificial transit markers. That continuity is manifested even in historical times, conditioning new communication forms that perpetuated prehistoric patterns as cognitive and social references to the biography of routes and paths [88,123,124,125].

Antequera and its megalithic past presents themselves as an ideal site to enrich the methodologies used in defining applicable models for direct surveys, such as the one we present here. This work argues for a richer consideration of Megalithism in the central area of Andalusia, whose data began to be valued scientifically practically at the end of the twentieth century, as part of an extended systematic approach to recognising sites, their uses, and their ancient heritage. Our results have been so fruitful that we will continue to develop this methodology for prospecting and recovering oral sources, adding archaeological information and expanding to the less explored sectors of the territory of Antequera.

A second phase of the Archaeological Intervention Project, authorised by the Culture Department of the Regional Government of Andalusia, is currently underway. We hope to obtain references on chronology and on the work of preparation and decoration of the supports, as well as on their archaeological contexts. Furthermore, the location of these menhirs will establish criteria for their protection and conservation as a Site of Cultural Interest within the protection limits established by UNESCO for the Dolmens of Antequera.

The future objective of this work is to deepen our understanding of prehistoric human occupation in Antequera through the study of the menhirs/steles presented in this paper as territorial markers. Their archaeology study we are currently conducting will provide the necessary keys to understanding settlement dynamics, the mobility of raw materials, construction techniques, their connection to transit, funerary, and residential sites, and even their relationship to sites with rock art through possible connecting routes between the coast and the interior and vice versa.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage8080291/s1, Table S1: Data from people interviewed about menhirs; Table S2: Characteristics of the studied menhirs; Tables S3 and S4: Geologic analysis of menhirs and quarries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B.-R. and L.C.-L.; methodology, L.C.-L., P.B.-R., R.d.B.-B., J.J.D.V. and S.R.D.-L.; software, J.L.C.H.; formal analysis, L.C.-L., M.J.A.-L. and P.B.-R.; investigation L.C.-L., M.J.A.-L., J.S.P., J.L.C.H., P.B.-R., R.d.B.-B., R.B.-B., A.V.M., J.J.D.V., S.R.D.-L., R.J.B. and R.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B.-R. and L.C.-L.; writing—review and editing P.B.-R., L.C.-L. and M.J.A.-L.; image authorship, R.B.-B., M.Á.V.S.-G., A.V.M., S.R.D.-L., R.M.G. and L.C.-L.; figure authorship, R.B.-B., R.d.B.-B. and L.C.-L.; validation, P.B.-R., L.C.-L., R.d.B.-B., J.J.D.V., S.R.D.-L., M.J.A.-L., J.S.P., J.L.C.H., R.B.-B., A.V.M., R.J.B., R.M.G. and M.Á.V.S.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funds for this research were granted by the research project PID2022-141188NB-I00 of the Ministry of Science and Innovation, Government of Spain. L. Cabello’s research is co-funded by the State Research Agency (Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain) and the European Social Fund Plus. Reference: PTA2022-022209-I/MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. For more statistical reports, see Supplementary Materials. For any other data not specifically indicated in the article, data might be available on request.

Acknowledgments

The work has been carried out with the corresponding archaeological permits granted by the Delegation of Culture of Málaga. We relied on support from the Dolmens of Antequera Interpretation Centre (CADA). We would like to especially thank Bartolomé Ruiz, Carmen Mora, and the site’s staff. Support from the local population, who still know these records, was essential as well. Support from our colleagues from other research teams who collaborated in the understanding of the megalithic territories of Antequera is also noteworthy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| RTI | Reflectance Transformation imaging |

| OSL | Optically Stimulated Luminescence |

References

- Parker-Pearson, M. Archaeology and legend: Investigating Stonehenge. Archaeol. Int. 2021, 24, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, J.A.; Jones, A.M.; Pollard, J.; Allen, M.J.; Gardiner, J. Contextualising Kilmartin: Building a narrative for developments in western Scotland and beyond, from the Early Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age. In Image, Memory and Monumentality: Archaeological Engagements with the Material World; Meirion, A., Pollard, J., Allen, M.J., Gardiner, J., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tramoni, P.; D’Anna, A.; Pasquet, A.; Milanini, J.L.; Chessa, R. Le site de Tivulaghju (Porto-Vecchio, Corse-du-Sud) et les coffres mégalithiques du Sud de la Corse, nouvelles données. Bull. De La Société Préhistorique Française 2007, 104, 245–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousseau, F. Bâtisseurs de Mégalithes: Un Savoir-Faire Néolithique Dévoilé par L’archéologie du Bâti; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2023; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Curdy, P.; Ferroni, A.M.; Pizziolo, G.; Keller, R.P.; Sarti, L.; Baioni, M.; Marongiu, S. St-Martin-de-Corléans (Aosta, Italy) Tomb TII: The Chronological and Cultural Sequence. In The Bell Beaker Culture in All Its Forms, Proceedings of the 22nd Meeting of ‘Archéologie et Gobelets’, Geneva, Switzerland, 21–22 Janurary 2021; Abegg, C., Carloni, D., Cousseau, F., Derenne, E., Ryan, J., Eds.; Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna, A.; Guendon, J.L.; Orsini, J.B.; Pinet, L.; Tramoni, P. Les alignements mégalithiques du plateau de Cauria (Sartene, Corse-du-Sud). In Corse et Sardaigne Préhistoriques: Relations et Échanges dans le Contexte Méditerranéen. Actes du 128e Congrès National des Sociétés Historiques et Scientifiques, Bastia, 2003; Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques: Paris, France, 2007; pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Linares-Catela, J.A.; Mora Molina, C.; López López, A.; Donaire Romero, T.; Vera-Rodríguez, J.C.; Bueno Ramírez, P. El sitio megalítico de La Torre-La Janera (Huelva): Monumentalidades prehistóricas del Bajo Guadiana. Trab. Prehist. 2022, 79, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L. O alinhamento da Têra, Pavia (Mora). Resultados da 1a Campanha (1996). In Muitas Antas, Pouca Gente?-Actas do I Colóquio Internacional sobre Megalitismo; Gonçalves, V., Catarina, A., Marques, A., Eds.; Instituto Português de Arqueologia: Reguengos de Monsaraz, Portugal, 2000; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Skeates, R.; Beckett, J.; Mancini, D.; Cavazzuti, C.; Silvestri, L.; Hamilton, W.D.; Angle, M. Rethinking Collective Burial in Mediterranean Caves: Middle Bronze Age Grotta Regina Margherita, Central Italy. J. Field Archaeol. 2021, 46, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.A.; Bueno-Ramírez, P.; Balbín-Behrmann, R.; Martineau, R.; Carrera-Ramírez, F.; Fairchild, T.; Southon, J. Charcoal painted images from the French Neolithic Villevenard hypogea: An experimental protocol for radiocarbon dating of conserved and in situ carbon with consolidant contamination. Archaeol. Anthr. Sci. 2020, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso Bermejo, R.; Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R. Megaliths Weapons representations: Aview of the birth of the Iberia warrior images. In Weapons Tools in Rock Art Aworld, Perspective; Bettencourt, A.M.S., Santos-Estévez, M., Sampaio, H.A., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbin Behrmann, R.; Barroso Bermejo, R. Chronologie de l’art Mégalithique ibérique: C14 et contextes archéologiques. L’Anthropologie 2007, 111, 590–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbin Behrmann, R.; Laporte, L.; Gouézin, P.; Cousseau, F.; Barroso, R.; Hernanz, A.; Iriarte, M.; Quesnel, L. Natural and artificial colours: The megalithic monuments of Brittany. Antiquity 2015, 89, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; de Balbín Behrmann, R. Megalithic art: Funeral scenarios in western Neolithic Europe. In The Megaliths of the World; Laporte, L., Large, J.M., Nespoulous, L., Scarre, C., Steimer-herbet, T., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; de Balbín Behrmann, R. Pigments for the dead: Megalithic scenarios in southern Europe. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2023, 15, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera Ramírez, F.; Fábregas Valcarce, R. Datación radiocarbónica de pinturas megalíticas del Noroeste peninsular. Trab. Prehist. 2002, 59, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, K.L.; Carrera Ramírez, F.; Fábregas Valcarce, R.; Guilderson, T.; Rowe, M.W. Direct radiocarbon dating of megalithic paints from north-west Iberia. Antiquity 2005, 79, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Soler Diaz, J.A. Construyendo identidades. Figuritas, estelas y menhires en el suroccidente de Iberia. In Ídolos. Miradas Milenarias Desde el Extremo Suroccidental de Europa; Bueno, P., Soler, J.A., Eds.; Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Turismo, Cultura y Deporte: Huelva, Spain, 2024; pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Linares Catela, J.A.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Barroso, R. Símbolos de la muerte en la Prehistoria Reciente del Sur de Europa. El dolmen de Soto, Huelva. España, Reed. 2024; Arqueología Monografías; Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; de Balbín Behrmann, R. Reconstruyendo Memorias megalíticas (REMEM). In Actualidad de la Investigación Arqueológica en España (2021–2022), Conferencias Impartidas en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional; Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Secretaría General Técnica, Subdirección General de Atención al Ciudadano, Documentación y Publicaciones, Ed.; Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Secretaría General Técnica, Subdirección General de Atención al Ciudadano, Documentación y Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, L.; Cousseau, F.; Ramírez, B.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Gouézin, P. Le douzième dolmen de Barnenez: Destructions et reconstructions au sein d’une nécropole mégalithique. Bull. De La Société Préhistorique Française 2017, 114, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madgwick, R.; Lamb, A.L.; Sloane, H.; Nederbragt, A.J.; Albarella, U.; Pearson, M.P.; Evans, J.A. Multi-isotope analysis reveals that feasts in the Stonehenge environs and across Wessex drew people and animals from throughout Britain. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, G. Art and death in late Neolithic Sardinia: The role of carvings and paintings in Domus de Janas rock-cut tombs. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2016, 26, 429–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. Megalithic art on the Great Circle at Newgrange and the implications for chronology. J. Ir. Archaeol. 2023, 32, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, R.M.; Alcock, S.E. Archaeologies of Memory: An Introduction; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Barroso Bermejo, R. Análisis de las grafías megalíticas de los dólmenes de Antequera y su entorno. In Dólmenes de Antequera. Tutela y Valorización Hoy; Ruiz González, B., Ed.; Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2009; pp. 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Gutiérrez López, J.M.; Enriquez Jarén, L. Hitos visibles del megalitismo gaditano. In Homenaje a Francisco Giles Pacheco; Mata, E., Ed.; Diputación Provincial de Cádiz, Servicio de Publicaciones, Asociación Profesional del Patrimonio Histórico-Arqueológico de Cádiz: Cádiz, Spain, 2010; pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; Carrera Ramírez, F.; Ayora Ibáñez, C. Secuencias de arquitecturas y símbolos en el dolmen de Viera (Antequera, Málaga, España). MENGA Rev. De Prehist. De Andal. 2013, 4, 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Barroso Bermejo, R.M.; Carrera Ramírez, F.; Huntz Ortiz, M.A.H. El arte y la plástica en el tholos de Montelirio. In Montelirio: Un Gran Monumento Megalítico de la Edad del Cobre; Fernández Flores, A., García Sanjuán, L., Díaz-Zorita Bonilla, M., Eds.; Consejería de Cultura: Sevilla, Spain, 2016; pp. 365–405. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R. Estelas Decoradas en los Megalitos del País Vasco. Megalitos, Espacios Sagrados y Referentes Territoriales; Museo de Bilbao: Zegama, Spain, 2023; pp. 266–289. [Google Scholar]

- Mora Molina, C. Los Monumentos Megalíticos de Antequera (Málaga): Una Propuesta Biográfica; Consejería de Cultura y Deporte, Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2024.

- Rogerio-Candelera, M.Á.; Bueno Ramírez, P.; De Balbín-Behrmann, R.; Dias, M.I.; García Sanjuán, L.; Coutinho, M.L.; Gaspar, D. Landmark of the past in the Antequera megalithic landscape: A multi-disciplinary approach to the Matacabras rock art shelter. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2018, 95, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, L. Megalithic architectures in Europe—A southern point of view. In Megalithic Architectures; Laporte, L., Scarre, C., Eds.; Oxbow Monographs: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- L’Helgouach, J. Les idols qu’on abat. Bull. De La. Société Polymath. Du. Morbihan 1983, 110, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ard, V.; Mens, E.; Poncet, D.; Cousseau, F.; Dehaix, J.; Mathé, V.; Pillot, L. Life and death of angoumoisin-type dolmens in west-central France: Architecture and evidence of the reuse of megalithic orthostats. Bull. De La Société Préhistorique Française 2016, 113–114, 737–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ard, V.; Mens, E.; Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Gouézin, P.H.; Laurent, A.; Linard, D.; Marquebielle, B.; Philippe-Lelong, A.C.; Polloni, A.; et al. The Roquefort Megalithic Monument at Lugasson (Gironde) and the Question of Gallery Graves in Aquitaine. Gall. Préhistoire 2024, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Heyd, V. The Transformation of Europe in the Third Millennium BC: The example of Le Petit-Chasseur I + III (Sion, Valais, Switzerland). Praehist. Z. 2007, 82, 129–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, J. People of stone: Stelae, personhood, and society in prehistoric Europe. J. Archaeol. Method. Theory 2009, 16, 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migdley, M. Megaliths in north-west Europe. The cosmology of sacred landscapes. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial; Tarlow, S., Nilsson Stutz, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 421–440. [Google Scholar]

- Scarre, C. Atlantic figurines. In Mobile Images of Ancestral Bodies: A Millenium Long-Perspective from Iberia to Europe; Bueno Ramírez, P., Soler Diaz, J.A., Eds.; Zona Arqueológica: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2021; Volume II, pp. 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Spatzier, A.; Bertemes, F. The ring sanctuary of Pömmelte, Germany: A monumental, multi-layered metaphor of the late third millennium BC. Antiquity 2018, 92, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz Paulsson, B.S. Radiocarbon dates and Bayesian modeling support maritime diffusion model for megaliths in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3460–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laporte, L.; Bueno Ramírez, P. On the Atlantic shores. The origins of megaliths in Europe? In Mégaliths of the World; Laporte, L., Large, J.-M., Nespoulous, L., Scarre, C., Herbet-Steimer, T., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 1173–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; López Quintana, J.C.; Guenaga Lizasu, A. Frontières et art mégalithique. Une perspective depuis le monde pyrenéen. L’Anthropologie 2009, 113, 882–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Ramirez, P.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; Balbin Behrmann, R. Megalithic paintings: Absence or mislead research? Andalucia as a South European case study. In Pierre à Bâtir, Pierre à Penser. Systèmes Techniques et Productions Symboliques des Pré et Protohistoire Méridionales; Archives d’Ecologie Préhistorique: Toulouse, France, 2023; Volume 13, Available online: https://univ-tlse2.hal.science/hal-04259814/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Peñalver, X. Estudio de los menhires de Euskal Herria. Munibe 1983, 35, 355–450. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos García, R.; Moreno Gallo, M.; Basconcillos Arce, J.; Delibes de Castro, G. Menhires prehistóricos en el sector nororiental de la meseta norte española: Análisis espacial concerniente a la hipótesis de una alineación estructurada y sincrónica. In Arqueología y Tecnologías de Información Espacial: Una Perspectiva Ibero-Americana; Maximiano Castillejo, A.M., Cerrillo Cuenca, E., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Barroso Bermejo, R. Custodian stones: Human Images in the Megalithism of the Southern Iberian Peninsula. In Rendering Death: Ideological and Archaeological Narratives from Recent Prehistory (Iberia); Cruz, A., Cerrillo, E., Bueno, P., Caninas, J., Batata, C., Eds.; British Archaeological Reports. International Series 2648; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; Balbin Behrmann, R. Steles, Time and Ancestors in the Megaliths of Antequera, Málaga (Spain). Menga 2017, 8, 193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Cámara Serrano, J.A.; Dorado Alejos, A.; Spanedda, L.; Fernández Ruiz, M.; Martínez García, J.; Haro Navarro, M.; Molina González, F. La demarcación de los espacios de tránsito en Los Millares (Santa Fe de Mondújar, Almería) y su relación con el simbolismo megalítico. Zephyrus 2021, 88, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailiff, I.K.; Andrieux, E.; Díaz-Guardamino, M.; Alves, L.B.; Rey, B.C.; Sanjuán, L.G.; Seijo, M.M. Dating the setting of a late prehistoric statue-menhir at Cruz de Cepos, NE Portugal. Quat. Geochronol. 2024, 83, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; González Cordero, A. El arte megalítico como evidencia de culto a los antepasados: A propósito del dolmen de La Coraja (Cáceres). Quad. De Prehistòria I Arqueol. De Castelló 2001, 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Barroso Bermejo, R.; Balbin Behrmann, R. Stone witnesses: Armed stelae between the international Tagus and the Douro, Iberian Peninsula. SPAL Rev. De Prehist. Y Arqueol. De La Univ. De Sevilla 2019, 28, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo-Cuenca, E.; Bueno-Ramírez, P.; de Balbin-Behrmann, R. 3DMeshTracings: A protocol for the digital recording of prehistoric art. Its application at Almendres cromlech (Évora, Portugal). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 25, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, V.; Godinho, R.; Granja, R.; Valera, A.C. Espacios funerarios de la Edad del Bronce en Outeiro Alto 2 (Brinches, Serpa, Portugal): La necrópolis de hipogeos. Zephyrus 2013, LXXI, 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Gallo, M.Á.; Delibes de Castro, G. Dataciones absolutas para un menhir del valle de Valdelucio (Burgos): Resultados de un sondeo en el túmulo de La Cuesta del Molino. Zephyrvs 2007, 60, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, A.C.; Coelho, M. A necrópole de hipogeus da Sobreira da Cima (Vidigueira, Beja): Enquadramento, arquitecturas e contextos. Era Monográfica 2013, 1, 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cassen, S. Exercice de Stèle: Une Archéologie des Pierres Dressées, Réflexion Autour des Menhirs de Carnac; Errance: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Calado, M. Standing stones and natural outcrops. The role of ritual monuments in the Neolithic transition of the Central Alentejo. In Monuments and Landscape in Atlantic Europe Perception and Society During the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age; Scarre, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, M.V.; Monteirio, J.P.; Serrâo, J.C. A estação pré-histórica da Caramujeira. Trabalhos de 1975–76. In III Jornadas Arqueológicas; AAP: Lisboa, Portugal, 1978; Volume I, pp. 33–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, M.V. Betilos, estelas e menires no Neolítico do Extremo Suroeste peninsular. In Idolos. Miradas Milenarias Desde el Extremo Suroccidental de Europa; Bueno, P., Soler, J.A., Eds.; Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Turismo, Cultura y Deporte: Huelva, Spain, 2024; pp. 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Breuil, H.; Verner, W. Découverte de deux Centres Dolméniques sur les bords de la Laguna de la Janda. (Cadix). Bulletin Hispanique; Annales de la Faculté des Lettres de Bordeaux et des Universités de Midi: Bordeaux, France, 1917; Volume XIX, pp. 157–188. [Google Scholar]

- Berdichewsky, B. Los Enterramientos en Cuevas Artificiales del Bronce I Hispánico; Biblioteca Praehistorica Hispana VI: Madrid, Spain, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Marqués-Merelo, I.; Aguado-Mancha, T.; Márquez-Romero, J.E. (Eds.) Necrópolis Prehistórica de Sepulcros Excavados en roca en el Cortijo de Alcaide (Antequera, Málaga); Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; Balbin Behrmann, R.; de Barroso Bermejo, R. Dioses y antepasados que salen de las piedras. Patrimonio Megalítico: Más allá de los límites de la Prehistoria. PH Boletín Del Inst. Andal. Del Patrim. Histórico 2008, 67, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- García Sanjuán, L.; Wheatley, D.W.; Lozano Rodríguez, J.A.; Evangelista, L.S.; González García, A.C.; Cintas-Peña, M.; Rivera Jiménez, T. In the bosom of the Earth: A new megalithic monument at the Antequera World Heritage Site. Antiquity 2023, 97, 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Ramírez, P.; de Balbín Behrmann, R.; Barroso Bermejo, R. Símbolos para los muertos, símbolos para los vivos. Arte megalítico en Andalucía. In Actas del II Congreso de Arte Rupestre Esquemático en la Península Ibérica; Martínez, J., Hernández, M.S., Eds.; Ayuntamiento de Vélez-Blanco: Almería, Spain, 2013; pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Camalich Massieu, M.D.; Martin Socas, D. Los inicios del neolítico en Andalucía. Entre la tradición y la innovación. Rev. Menga 2013, 4, 103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Cantalejo Duarte, P.; Espejo Herrerías, M. Málaga en el Origen del arte Prehistórico Europeo; Pinsapar, Ed.; Guía de las cuevas prehistóricas malagueñas; Diputación de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda Jiménez, G.; García Sanjuán, L.G.; Lozano Medina, A.; Costa Caramé, M.E. Nuevas dataciones radiométricas del dolmen de Viera (Antequera, Málaga, España). Menga Rev. De Prehist. De Andal. 2013, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Zorita Bonilla, M.; García Sanjuán, L. Las inhumaciones medievales del atrio del dolmen de Menga (Antequera, Málaga): Estudio antropológico y cronología absoluta. Menga Rev. De Prehist. De Andal. 2012, 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar Fernandez, A.; Marques Merelo, I.; Jimenez Brobeil, S.A.; Aguado Mancha, T.; Fernández, A.T. El hipogeo número 14 de la necrópolis de Alcaide (Antequera, Málaga): Un enterramiento colectivo de la Edad del Bronce. Menga Rev. De Prehist. De Andal. 2014, 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda Jiménez, G.; Sanchez Romero, M.; Diaz-Zorita Bonilla, M.; Lozano Medina, A.; Escudero Carrillo, J.; Milesi, L. Cultural resistance to social fragmentation: The continuity and reuse of megalithic monuments during the Argaric Bronze Age in southeastern Iberia. In The Matter of Prehistory: Papers in Honor of Antonio Gilman Guillén; Díaz, P., Lilios, K., Sastre, I., Eds.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lorrio, A.J.; Montero Ruiz, I.M. Reutilización de sepulcros colectivos en el Sureste de la Península Ibérica: La colección Siret. Trab. De Prehist. 2004, 61, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milesi García, L.; Aranda Jiménez, G.; Bonilla, M.D.-Z.; Ruiz Carrasco, S.; Hamilton, D.; Vilches Suárez, M.; Becerra Fuello, P. Funerary practices in megalithic tombs during the argaric Bronze Age in South-Eastern Iberia: The cemetery of los Eriales. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 49, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Padilla, J.; Álvarez Martín-Aguilar, M.; Mora Serrano, B.; Machuca Prieto, F.; Caro Herrero, J.L.; López Chamizo, S.; Schloen, D.; López-Rúiz, C.; Sáenz Romero, A.; Ramírez Cañas, C.; et al. Novedades en la investigación arqueológica en el yacimiento fenicio del Cerro del Villar, Málaga (2021–2022). In Entre Málaga y Tiro una Travesía Mediterránea en Memoria de la Profesora María Eugenia Aubet Semmler; Núñez, F.J., Mederos, A., Suárez, J., Mora, B., Martín, E., Eds.; Anejos de la revista Mainake; CEDMA: Málaga, Spain, 2025; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Atencia Páez, R.; Serrano Ramos, E. Las comunicaciones de Antequera en época romana. Jábega 1980, 31, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gozalbes Cravioto, C.G. El Camino Real de Málaga a Antequera en el siglo XVIII. Jábega 1981, 55–61. [Google Scholar]