Abstract

This study presents the e[kent-im] model, a map-based crowdsourcing initiative that digitizes and safeguards urban memory and cultural heritage through community participation and digital tools. The model facilitates the collection, archiving, and dissemination of urban memories by fostering intergenerational knowledge transfer and encouraging civic engagement in heritage preservation. Implemented in the historical center of Kütahya/Türkiye, the project gathered 150 memories and stories from 12 senior participants aged 50–85, which were linked to 303 historical visuals sourced from personal archives. These materials were integrated into a custom-designed web and mobile interface (Mapotic Pro) enriched with metadata categories such as type, period, and location, enabling users to filter and navigate content effectively and watch the videos enriched with participant narratives. A digital city archive matrix was also developed to systematically organize the collected data and support the web-based platform. To assess the platform’s effectiveness, a pilot study with 15 young participants aged 18–28 was conducted. During a self-guided city tour, participants engaged with historical content on the platform and provided feedback through pre- and post-test evaluations. Results indicated heightened awareness of and interest in cultural heritage, demonstrating the model’s potential as both an interactive archive and a tool facilitating intergenerational heritage awareness. Overall, this study highlights the model’s adaptability, scalability, and capacity to bridge generational and technological divides.

1. Introduction

In the transmission of urban cultural heritage and memory, crowdsourcing emerges as a critical method for understanding the dynamic and multilayered nature of cities and societal memory. A city is composed of diverse elements—streets, alleys, monumental structures, original textures, and public spaces—that function and evolve like a living organism. Given their constantly changing and complex structures, cities require analysis from a broad perspective and diverse descriptive approaches that reflect their versatility [1]. Every trace within the city, whether inherent or later added, evokes memories of the past, stimulates curiosity about forgotten places, and fosters a desire to learn [2]. Streets and residential architecture that developed over time, together with structures from various historical periods—such as inns, baths, mosques, churches, castles, and cemeteries—constitute integral components of urban memory. The names and symbolic associations of these structures further reinforce collective remembrance.

Individual memories, shaped by personal experiences or past events, are transmitted through oral narratives, cultural processes, or personal research [2]. Yet, physical characteristics alone cannot define urban memory. Rather, collective memory emerges from citizens’ stories and recollections, which imbue the city with symbolic meaning. In this context, urban memory and cultural heritage crowd-mapping applications have been identified as effective tools for strengthening collective memory and safeguarding cultural heritage [3]. Such applications revitalize connections between individuals and their past, making heritage more visible and accessible. They not only facilitate the transfer of cultural knowledge but also enhance communities’ sense of ownership and engagement with heritage assets [4,5]. By enabling intergenerational knowledge exchange, participatory heritage platforms enrich social memory and reinforce the bridge between past and present [6].

The preservation and digitization of cultural heritage have long been emphasized in international conventions and scholarly debates. Venice Charter (1964) [7,8] highlighted the need to safeguard both the tangible and intangible values of heritage. Meanwhile, digital technologies have since become powerful instruments in this process [9]. Recent studies underline the role of digital tools in ensuring the sustainability of heritage and raising societal awareness [10,11].

Urban memory, nourished by both individual and collective memory, encompasses a city’s past, cultural heritage, and shared experiences [12,13]. Its multidimensional nature enables it to serve as a bridge between the past and the future, integrating historical, physical, and cultural elements [1,2]. The physical fabric of cities thereby materializes collective memory, reinforcing the preservation and transmission of cultural heritage [14].

Within this perspective, this study aims to develop a digital urban memory transfer model, called e[kent-im], to investigate its benefits for cultural heritage. The model uses crowdsourcing to collect historical photos, images, and spoken and written knowledge to facilitate the transfer of knowledge from elderly urban residents to younger generations. This research focuses on the historical city center of Kütahya as a case study to support digital memory transfer processes. This research investigates the progressive loss of urban memory and intangible heritage in Kütahya, where oral histories and spatial knowledge are not systematically recorded or archived. The research question guiding this study is as follows: how can a map-based crowdsourcing model support the documentation, transmission, and public accessibility of urban memory across generations? Therefore, two hypotheses are generated: (i) integrating tangible heritage (archival visuals and spatial data) with intangible heritage (oral narratives) through a map-based digital platform will significantly enhance users’ understanding and awareness of urban cultural heritage, and (ii) exposure to intergenerational memory transfer—specifically, narratives provided by elderly residents—will produce a measurable positive shift in young participants’ engagement, curiosity, and learning outcomes related to urban cultural heritage.

2. Theoretical Background on Urban Memory, Crowdsourcing and Digital Storytelling

Recent scholarship in cultural heritage and urban studies increasingly emphasizes the need to understand urban memory as a dynamic, participatory, and digitally mediated process shaped by everyday practices, spatial experience, and collective narratives. As historic urban environments face growing pressures from tourism-driven transformation and commercialization, researchers have turned to digital tools, crowdsourcing practices, and storytelling platforms to capture, preserve, and disseminate diverse memories of place. Within this context, urban memory is no longer confined to static representations or expert-driven archives, but is increasingly constructed through community participation, user-generated content, and interactive digital environments. However, despite the expanding body of research on participatory heritage, digital storytelling, and crowdsourcing technologies, existing studies often treat these dimensions in isolation, offering limited insight into how they can be systematically integrated to support long-term preservation of urban memory, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and meaningful spatial engagement. In this context, the related literature is discussed across three interrelated dimensions—urban memory, crowdsourcing, and digital storytelling—to frame the conceptual and methodological foundations of the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Related studies on urban memory, crowdsourcing and digital storytelling.

Urban memory literature emphasizes the close relationship between everyday spatial practices, collective memory, and the lived experience of place. One study [15] demonstrates this relationship in Misi Village by revealing a clear divergence between tourists’ commerce-driven spatial perceptions and residents’ efforts to sustain urban memory through daily life and traditional practices, highlighting how tourism-oriented transformations risk fragmenting urban memory. Complementing this perspective, ref. [16] underlines the growing role of online narrative applications and social media integrations in preserving historic urban landscapes, suggesting that digital environments can act as alternative memory carriers beyond physical space. Similarly, ref. [17] stresses the importance of crowd participation in archeology and heritage projects, arguing that involving broader segments of society enables more diverse and plural narratives of place to emerge. While these studies collectively underscore the significance of participatory and digitally mediated approaches for sustaining urban memory, they largely focus on either narrative diversification or representational practices, offering limited insight into how structured, map-based digital systems can systematically archive, organize, and transmit urban memory across generations.

Crowdsourcing research on cultural heritage has primarily concentrated on platform design, metadata enrichment, and user engagement strategies. One critical study [18] proposes a criteria-based evaluation framework for crowdsourcing applications that integrates digital storytelling and geotagging, revealing strong public interest in participatory heritage storytelling while also exposing gaps between user expectations and actual engagement. Similarly, ref. [19] addresses the challenge of poor metadata quality in digital heritage platforms by introducing a personalized image annotation recommendation system, emphasizing the role of user-centered design in improving both data quality and participation. Map-based crowdsourcing platforms such as Kbhbilleder.dk further illustrate how spatial interfaces enable users to contribute historical photographs and metadata, primarily driven by personal identity, local history, and community belonging, in the context of Copenhagen City Archive [6]. In parallel, ecosystem-based approaches such as Crowd Heritage aim to combine human and automated enrichment processes to enhance metadata quality at scale [20]. Other studies focus on system reliability, usability, and participation, including mobile crowdsourcing for shared memory management [5] and community-driven sound heritage archives [21]. Despite these advances, much of the literature prioritizes technical enrichment and participation metrics, paying comparatively less attention to how crowdsourced content can serve as an intergenerational urban memory archive embedded within everyday spatial experience.

Digital storytelling scholarship has the potential to support community archives, participation, and intangible cultural heritage. The MNEMOSCOPE model exemplifies this by enabling users to digitally create and visualize collective memories, thereby enriching community archives and encouraging sharing [22]. Gamification and motivational design principles have also been shown to play a critical role in sustaining participation in mobile crowdsourced heritage applications [23]. Other studies focus on social and experiential dimensions of storytelling, such as the impact of digital storytelling environments on older adults’ sense of loneliness [24], and the democratic and participatory production of cultural content through platforms like izTRAVELSicilia [25]. While these works confirm the effectiveness of digital storytelling in engagement and social inclusion, they often treat storytelling as an isolated narrative layer rather than as part of a spatially structured, map-based system that integrates memory, place, and intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Taken together, the literature reveals a fragmented landscape in which urban memory, crowdsourcing, and digital storytelling are frequently addressed as parallel or partially overlapping domains. Existing studies demonstrate the value of participation, digital narration, and spatial interfaces, yet they fall short of offering integrated models that systematically combine map-based crowdsourcing, structured digital archiving, and intergenerational knowledge transfer within a single urban memory framework. This gap underscores the significance of our study, which positions urban memory not only as content to be collected or narrated, but as a digitally mediated, spatially organized, and socially sustained process.

3. Materials and Methods

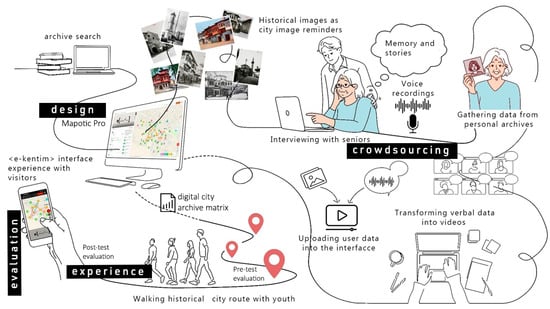

The e[kent-im] digital urban memory transmission model was developed using a multi-layered methodological framework consisting of four main stages: design, crowdsourcing, experience, and evaluation. Each stage was carefully structured to integrate archival research, senior community participation, digital mapping, and user-centered evaluation, ultimately aiming to safeguard and transmit cultural heritage and urban memory in a participatory and sustainable manner (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visualization of the e[kent-im] digital urban memory transfer model workflow.

First, in the design phase, the primary objective was to establish the digital infrastructure and compile the visual and textual materials that comprise the archive’s core. A map-based platform, Mapotic Pro (Czech Republic) was selected to accommodate diverse data types, and enable spatial exploration and user interaction. Archival research played a central role in this stage: historical photographs, drawings, and documents were collected from libraries, institutional and personal archives, and published material. These materials were digitized in high resolution, cataloged, and enriched with contextual descriptions. Each visual item was then categorized by type and geolocated when possible, forming the foundation of the digital city archive matrix that organizes the material in a searchable, structured format.

The second phase, crowdsourcing, focused on gathering oral narratives and lived experiences from senior participants with first-hand knowledge of the city’s cultural and urban past. Participants were presented with visual materials to prompt memory recall, leading to the narration of stories, personal memories, and local traditions. These oral contributions were recorded, transcribed, and coded according to narrative type, theme, and associated visual material. When locations were uncertain, participants provided spatial clues that helped geolocate historical photographs, making them active contributors in reconstructing lost or transformed urban elements. The integration of oral, visual, and written data created a multimodal repository that captured both tangible and intangible heritage.

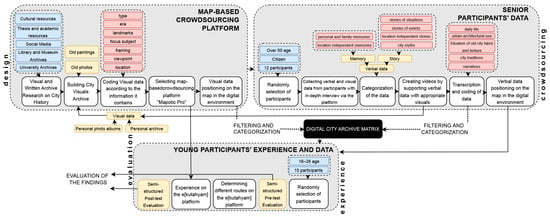

To evaluate this platform, during the experience phase, 15 young participants (aged 18–25) used the digital interface during self-guided walks in the historical center of Kütahya. The platform allowed users to navigate mapped content, explore thematic routes, and engage with photographs and narratives associated with specific locations. This hybrid interaction model, combining in situ exploration with digital storytelling, enabled participants to develop a deeper and more situated understanding of the city’s historical layers. Pre- and post-test evaluations were conducted via a comparative analysis. Overall, the four-phase methodology demonstrated the potential of map-based crowdsourcing to preserve, enrich, and transmit urban memory in a participatory and accessible manner (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

e[kent-im] digital urban memory transfer model workflow diagram.

4. Results

The case study of the study has been conducted in the historical city center of Kütahya/Türkiye, a city deeply layered with the legacies of multiple civilizations, including Phrygians, Romans, Byzantines, Seljuks, Germiyanids, and Ottomans. Kütahya, a historic city in Mid Anatolia, was chosen as the pilot site due to its wealth of surviving cultural assets, its layered urban morphology, and the availability of diverse historical documents and community memories.

In this respect, the project extends beyond creating a repository; it develops a participatory digital heritage ecosystem, which fosters civic engagement, cultural continuity, and new practices of heritage consumption and co-production. The results of the e[kent-im] model case study are outlined below:

4.1. Design Phase

As it was detailed in the methodology section, in the first design phase, a map-based interface was developed to integrate multiple data types (visual, oral, and textual). Archival research was conducted in libraries, institutional archives, private collections, and even social media platforms. A substantial visual repository was compiled, including more than 1300 paintings by Ahmet Yakupoglu, painter, who meticulously documented the urban fabric of Kütahya throughout the twentieth century. These were supplemented by historical photographs, ranging from black-and-white images from the late 19th century to color photographs from the mid-20th century (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sample coding for the digital archive: (left) paintings of Melek Girmez Çıkmazı by Ahmet Yakupoglu 1970, 1991, R38 [26] (right) photograph around Karagöz Mosque, 1960, F120 (Mustafa Hakkı Yesil personal archive) (bottom) visual data coding sample.

Each visual was carefully indexed with metadata, including title, creator, date, source, and location. Where possible, lost or transformed urban elements (such as demolished mosques, hamams, or commercial buildings) were geolocated on the map, enabling a comparative reading of urban change.

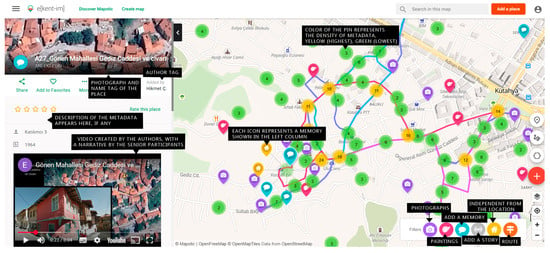

The digital interface of the e[kent-im] model was designed for both web and mobile access, ensuring accessibility for users across groups. The entry page displayed a map marked with the locations of collected content, accompanied by a side panel providing project information, metadata, and the latest updates. Categories—such as photographs, drawings, memories, stories, and routes—were clearly structured and filterable, allowing users to navigate the content effectively (Figure 4). The platform can be reached via [27].

Figure 4.

e[kent-im] interface in Mapotic Pro, black tags show the user interface details.

4.2. Crowdsourcing Phase

As for the senior participant group, in-depth oral history interviews were conducted with 12 people (aged 50–85). Participants were randomly approached within the local community, without the intention of forming a statistically representative sample, as the primary objective was conceptual and spatial mapping of urban memory rather than demographic generalization. Gender balance was intentionally considered, and participants were selected from everyday local roles, including male shopkeepers and female housewives, to reflect lived urban practices. Each interview lasted between 1 and 2 h and was conducted using historical photographs and images integrated into the e[kent-im] platform to stimulate memory recall and narrative production.

Oral narratives were recorded, edited, and categorized into three types: memories, stories, and independent narratives. In total, 150 oral narratives were collected, with women generally contributing more stories than men. These narratives covered a wide spectrum of urban life: architecture; neighborhood relations; religious practices; commercial spaces; everyday rituals; and intangible traditions such as weddings, circumcisions, folk songs, and seasonal festivities (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Senior participants’ interviews and collecting data for the platform.

Narratives were transformed into short videos by embedding audio recordings with relevant visuals. These were then uploaded to YouTube and integrated into the e[kent-im] platform via embedding tools.

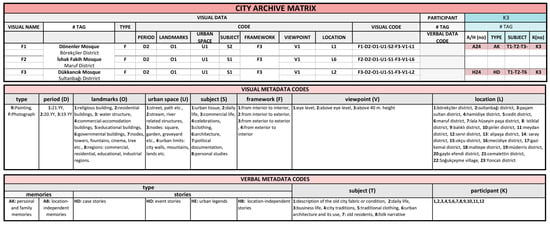

The collected visual and narrative data were integrated into a custom-designed web-based interface and systematically organized using a Digital City Archive Matrix (Table S1), in which both tangible and intangible heritage layers were categorized, tagged, and structured using metadata parameters. This phase prioritized depth, richness, and narrative diversity over participant quantity, in line with qualitative heritage research practices. The sample coding of this archive is shown in Figure 6, visual and verbal metadata code are used to create visual and verbal codes for each item.

Figure 6.

Sample view of the e[kent-im] digital city archive matrix (top), visual metadata (middle) and verbal metadata (bottom) codes.

4.3. Experience and Evaluation Phases

The experience phase focused on enabling young participants (15 person, aged 18–28) to explore the digital archive through interactive and situated engagement with the urban environment. Participant selection did not aim for statistical randomness or representativeness, as the study follows a qualitative, exploratory research design. Instead, a maximum variation approach was adopted to capture diverse lived experiences of urban memory. Among older participants, diversity was ensured through everyday social roles (e.g., local shopkeepers and homemakers), gender balance, and long-term residency in the historical center, rather than formal educational or socioeconomic classification. For the younger group, participants included both locals and non-local visitors, enabling the exploration of different levels of familiarity with the city. This approach was intentionally chosen to minimize selective bias at the experiential level and to support context-sensitive and analytically generalizable findings.

Within the scope of the study, several walking routes were defined in the historic city center of Kütahya (Figure 7). These routes were designed to include key locations that best represent the city’s historical narrative and intersect with points where archival data were available within the e[kent-im] interface. The selected routes were subsequently integrated into the digital map of the platform. They were instructed to focus on observing, learning about, and experiencing the urban environment during the walk. No navigational directions were provided along the route.

Figure 7.

Young participants walking on the routes of the platform.

Following the completion of the walk, participants were asked to sit in an indoor setting and respond to the first set of survey questions based solely on the knowledge and impressions they had acquired during the physical exploration of the city. After completing the pre-test evaluation, participants were then invited to explore the same routes digitally through the interface. At this stage, they examined historical visual materials and oral narratives provided by senior participants, allowing them to access layers of urban memory not immediately visible during the walk. Based on this additional digital engagement, participants completed post-test evaluations and in-depth interviews were recorded for open-ended questions.

Throughout the walking phase, participants were observed unobtrusively. Each session lasted approximately 1.5–2 h. They were allowed to stop, examine locations of interest, and enter spaces freely, without any form of intervention by the researchers. At the end of the route, participants used their mobile devices in an appropriate indoor environment to further explore the interface and complete the survey process.

For the evaluation phase, data were collected using semi-structured pre- and post-test questions (Table S2) designed to explore changes in participants’ awareness, perceptions, and engagement with urban memory after interacting with the platform. Although the initial research plan aimed to include a larger group, practical constraints related to time, budget, and site conditions necessitated a smaller sample, which remains methodologically appropriate for a qualitative pilot study.

The comparison conducted after the pilot walks confirmed that digital heritage tools can foster intergenerational dialog and increase the accessibility of urban history. Furthermore, the integration of crowdsourced oral narratives enriched the archival materials, bridging the gap between formal history and lived experiences (Table 2) (also see Table S3).

Table 2.

Comparing selected questions from Pre- and Post-Test, showing the relevant results of interest and evaluation of the proposed research (PT1 (pre-test), PT2 (post-test) Q (question no), SA (strongly agree), A (agree), N (neutral), D (disagree), SD (strongly disagree), R (overall mean value).

5. Discussion

The discussion of findings highlights the critical role of digitally mediated storytelling in enhancing young users’ engagement with urban and cultural heritage. One of the most prominent outcomes of the study was the heightened appreciation for intergenerational knowledge transfer. Following the interaction with the e[kent-im] interface, 14 out of 15 young participants explicitly acknowledged the importance of oral narratives in transmitting cultural memory across generations. This finding underscores the value of integrating lived experiences and personal memories of senior residents into digital heritage platforms, particularly for audiences who may otherwise remain detached from intangible cultural dimensions.

Feedback from senior participants further reinforces this observation. Their expressed sense of pride in contributing to the preservation of urban memory suggests that the platform functioned not only as a tool for knowledge dissemination but also as a medium for social recognition and inclusion. This reciprocal dynamic—where younger participants gain cultural awareness while older residents actively participate in heritage narration—points to the potential of digital platforms to bridge generational gaps within urban memory practices.

The pre- and post-test evaluations conducted with young participants revealed statistically meaningful developments across four primary categories: (i) knowledge of urban and cultural heritage, (ii) topic-specific knowledge, (iii) need for a city guide, and (iv) touristic walk experience based on verbal data. In terms of general knowledge of urban and cultural heritage, all participants reported an increased understanding of Kütahya’s architectural past and historical structures after engaging with the platform. This indicates that the integration of spatially anchored digital content effectively supports learning processes that go beyond conventional, text-based heritage communication.

Improvements in topic-specific knowledge further demonstrate the impact of multimodal storytelling. Participants emphasized that listening to the oral histories of senior participants significantly contributed to their understanding of Kütahya’s architectural history, traditions, customs, and urban development. The combination of historical photographs, visual materials, and personal narratives enabled users to contextualize urban change over time. As one participant noted, encountering unfamiliar historical states of streets and buildings during the walk, supported by visual and narrative layers, facilitated immediate comprehension and deeper engagement. These findings suggest that visual–verbal juxtaposition strengthens cognitive connections between place, memory, and historical interpretation.

Another notable outcome concerns the perceived need for a city guide. Participants increasingly regarded the e[kent-im] interface as a functional and informative guide during touristic walks. The location-based presentation of data allowed users to progress freely along routes while receiving contextual information at relevant points. This reinforces the idea that digital heritage interfaces can substitute or complement traditional guided tours by offering autonomy without sacrificing informational depth. Suggestions emphasizing greater flexibility within routes and improved location-based triggering further support this interpretation.

The category of touristic walk experience, evaluated through verbal data, revealed a strong preference for oral narratives over written content during in situ exploration. While elderly residents’ spoken stories were reported to have a high impact on learning and engagement, written materials were considered less practical during walking activities. This distinction highlights the importance of designing heritage interfaces that align with embodied and mobile user experiences, favoring auditory and visual content over extensive textual information in outdoor contexts.

Participants’ suggestions for future development further illuminate the platform’s broader potential. Proposed enhancements included transforming walking routes into narrated video experiences for users unable to physically visit the city, as well as strengthening visual comparison through the systematic use of past–present photographic pairs. These recommendations indicate that digital urban memory platforms can extend beyond on-site experiences and reach wider audiences, including tourists, students, and remote users.

From an educational perspective, the findings point to significant applicability within formal learning environments. One participant noted that video-based content already attracts student attention in secondary education and suggested that the e[kent-im] videos could be integrated into school curricula to introduce Kütahya’s urban history. This observation aligns with broader discussions on experiential and media-based learning, suggesting that digital heritage platforms may serve as effective pedagogical tools.

Overall, the discussion demonstrates that digitally supported urban memory platforms such as e[kent-im] possess strong potential across tourism, education, and cultural sectors. By combining spatial exploration, oral histories, and visual storytelling, the platform supports meaningful engagement with heritage while fostering intergenerational dialogue. These findings suggest that future studies should further explore mobile application development, automated location-based content delivery, and expanded audiovisual narratives to enhance accessibility and user experience.

6. Conclusions

This study set out to investigate how a map-based crowdsourcing model can support the documentation, transmission, and public accessibility of urban memory across generations. In response to this problem statement, two hypotheses were proposed: first, that integrating tangible heritage elements—such as archival visuals and spatial data—with intangible heritage in the form of oral narratives within a digital, map-based platform would significantly enhance users’ understanding and awareness of urban cultural heritage; and second, that exposure to intergenerational memory transfer, particularly through narratives provided by elderly residents, would generate a measurable positive shift in young participants’ engagement, curiosity, and learning outcomes related to urban heritage.

The findings of the study strongly support both hypotheses. Results from the experience phase and the pre- and post-test evaluations demonstrate that the e[kent-im] platform effectively enhanced young users’ knowledge of Kütahya’s urban and cultural heritage, deepened topic-specific understanding, and transformed their perception of digital tools as functional alternatives to traditional city guides. Most notably, the integration of oral histories significantly increased participants’ awareness of the value of intergenerational knowledge transfer, confirming that intangible heritage—when spatially anchored and digitally mediated—plays a critical role in shaping meaningful urban memory experiences.

When positioned within the existing literature, the contribution of this study becomes clearer. Urban memory research emphasizes the relationship between everyday spatial practices and collective memory, while also highlighting the risk of fragmentation caused by tourism-driven transformations [15]. Parallel studies point to the growing role of digital narratives and participatory platforms in preserving urban memory beyond physical space [16,17]. Map-based crowdsourcing initiatives such as Kbhbilleder.dk demonstrate the potential of spatial interfaces to support the contribution of local historical knowledge [26], and digital storytelling models like MNEMOSCOPE confirm the value of narrative-based approaches in enriching collective memory [22]. Nevertheless, existing studies largely address these themes separately, offering limited insight into integrated, map-based systems that systematically combine tangible and intangible heritage with intergenerational knowledge transfer embedded in everyday spatial experience. This study addresses this gap by proposing a spatially structured, participatory model for sustaining urban memory across generations.

By contrast, this study demonstrates how a spatially organized, map-based digital platform can function simultaneously as an urban memory archive, an experiential learning environment, and a participatory storytelling system. The e[kent-im] model moves beyond treating memory as static content to be collected or displayed; instead, it conceptualizes urban memory as a dynamic, socially sustained process embedded within everyday spatial experience. The inclusion of elderly residents as active contributors further extends the scope of digital heritage research by foregrounding intergenerational dialogue as a core component of cultural sustainability.

Despite these contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. The study was conducted with a relatively small participant group and focused on a single historic urban context. While this allowed for in-depth qualitative and experiential analysis, future research would benefit from expanding the platform to larger and more diverse user groups, as well as applying the model to different cities with varying cultural and spatial characteristics. Additionally, the development of a fully mobile application with automated location-based content delivery, enriched audiovisual narratives, and remote-access features—such as narrated video routes—could significantly enhance accessibility and user engagement.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates that map-based crowdsourcing platforms integrating tangible and intangible heritage hold substantial potential for sustaining urban memory across generations. By combining spatial exploration, digital storytelling, and participatory knowledge production, e[kent-im] offers a scalable and adaptable framework applicable to tourism, education, and cultural institutions. The study contributes to ongoing discussions in digital heritage and urban memory by proposing an integrated model that not only preserves the past but actively reactivates it through contemporary, socially inclusive digital practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage8120545/s1, Table S1: The digital city archive matrix, created for this study within Kütahya; Table S2: Interview questions for senior participants, pre- and post-test evaluations for young participants; Table S3: A longer version of Table 2, presenting the comparative table of pre- and post-test evaluations’.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization H.K.S.Y. and D.G.Ö.; methodology, H.K.S.Y. and D.G.Ö.; software, H.K.S.Y.; investigation, H.K.S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K.S.Y. and D.G.Ö.; writing—review and editing, D.G.Ö.; visualization, H.K.S.Y. and D.G.Ö.; supervision, D.G.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available and can be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

This paper is an outcome of a Master’s Thesis, successfully completed in ITU Architectural Computing Programme in 2024, named “Digital urban memory transmission model using map-based crowdsourcing method e[kent-im]: The case of Kütahya City Center”. All photographs and visual materials are created by authors if not stated otherwise.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rivero Moreno, L.D. Sustainable city storytelling: Cultural heritage as a resource for a greener and fairer urban development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraoğlu Yumni, H.K.; Ozer, D.G. Map-Based Crowdsourcing in Cultural Heritage and Urban Memory Transmission: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism (ICCAUA), Alanya, Turkey, 23–24 May 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, C.L.; Goulding, A.; Nichol, M. From shoeboxes to shared spaces: Participatory cultural heritage via digital platforms. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2022, 25, 1293–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukoulis, K.; Koukopoulos, D.; Koubaroulis, G. Towards a Mobile Crowdsourcing System for Collective Memory Management. In Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection; Ioannides, M., Fink, E., Brumana, R., Patias, P., Doulamis, A., Martins, J., Wallace, M., Eds.; EuroMed 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, K.; Dahlgren, A.N. Crowdsourcing historical photographs: Autonomy and control at the Copenhagen City Archives. Comput. Support. Coop. Work (CSCW) 2022, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments. 1931. Available online: http://www.icomos.org.tr/Dosyalar/ICOMOSTR_en0660984001536681682.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- ICOMOS. The Venice Charter—International Council on Monuments and Sites. 1964. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/157-thevenice-charter (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Bentkowska-Kafel, A.; Denard, H.; Baker, D. The London Charter for The Computer-Based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage Version 2.1, February 2009)1. In Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage; Bentkowska-Kafel, A., Denard, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, M.; Magnenat-Thalmann, N.; Papagiannakis, G. (Eds.) Mixed Reality and Gamification for Cultural Heritage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu, D.; Stefan, L. Immersing into the Past: An Augmented Reality Method to Link Tangible and Intangible Heritage. Plur. Hist. Cult. Soc. 2020, 8, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; Coser, L.A., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992; ISBN 0-226-11596-8. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, J. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino, I. Invisible Cities; Harvest: Dresher, PA, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-15-645380-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cankurt Semiz, S.N.; Özsoy, F.A. Transmission of Spatial Experience in the Context of Sustainability of Urban Memory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoeven, A. Valuing Urban Heritage Through Participatory Heritage Websites: Citizen Perceptions of Historic Urban Landscapes. Space Cult. 2020, 23, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insole, P. Crowdsourcing the Story of Bristol. In Urban Archaeology, Municipal Government and Local Planning; Baugher, S., Appler, D.R., Moss, W., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ziku, M.; Kotis, K.; Pavlogeorgatos, G.; Kavakli, E.; Zeeri, C.; Caridakis, G. Evaluating Crowdsourcing Applications with Map-Based Storytelling Capabilities in Cultural Heritage. Heritage 2024, 7, 3429–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.M.; Gil-Solla, A.; Guerrero-Vásquez, L.F.; Blanco-Fernández, Y.; Pazos-Arias, J.J.; López-Nores, M. A Crowdsourcing Recommendation Model for Image Annotations in Cultural Heritage Platforms. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldeli, E.; Menis-Mastromichalaki, O.; Bekiaris, S.; Ralli, M.; Tzouvaras, V.; Stamou, G. CrowdHeritage: Crowdsourcing for Improving the Quality of Cultural Heritage Metadata. Information 2021, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelmi, P.; Kuşcu, H.; Yantaç, A.E. Towards a sustainable crowdsourced sound heritage archive by public participation: The soundsslike project. In Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Gothenburg, Sweden, 23–27 October 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velhinho, A.; Almeida, P. MNEMOSCOPE—A Model for Digital Cocreation and Visualization of Collective Memories. In Applications and Usability of Interactive TV (JAUTI 2022); Abásolo, M.J., de Castro Lozano, C., Cifuentes, G.F.O., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1820, pp. 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannewijk, B.; Vinella, F.L.; Khan, V.-J.; Lykourentzou, I.; Papangelis, K.; Masthoff, J. Capturing the City’s Heritage On-the-Go: Design Requirements for Mobile Crowdsourced Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrakis, D.; Chorianopoulos, K.; Tselios, N. Digital Storytelling Experiences and Outcomes with Different Recording Media: An Exploratory Case Study with Older Adults. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2020, 38, 352–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccone, S.C.; Bonacini, E. New Technologies in Smart Tourism Development: The #iziTRAVELSicilia Experience. Tour. Anal. 2019, 24, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şerifoğlu, O.F. Ahmet Yakupoğlu: Anadolu; İstanbul, T.C., Başbakanlık Toplu Konut İdaresi Baskanlığı Kültür Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- e[kentim]. Mapotic Map-Based Platform for Kütahya; Saraoğlu Yumni, H.K., Ozer, D.G., Eds.; e[kentim]: Istanbul, Turkey, 2024; Available online: https://www.mapotic.com/eskiden-kutahyam/2986084-center (accessed on 13 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).