Abstract

Over the past few decades, the focus on the geographic origin of cacao has shifted from Mesoamerica to the Upper Amazon region of Ecuador. Recent research clarifies the trajectory of cacao, tracing its circulation from this Amazonian origin area to the Ecuadorian coast and subsequently to Mesoamerica. However, the presence of cacao in the Andean valleys has remained elusive and largely unstudied until now. This paper presents the first evidence of cacao consumption in the Andes region at the beginning of the Integration Period (AD 500–1500) during pre-Hispanic times. Starch granules and theobromine alkaloid were identified in a vessel recovered from a settlement in present-day Quito. The high concentration of theobromine detected allows us to infer that the cacao used most likely originated from Theobroma cacao, although aDNA would be needed to confirm this. Moreover, the vessel contained starch granules from other plants, suggesting the utilization of the vessel for serving various food preparations. This finding allows us to suggest that cacao was not only consumed in the Amazon and coastal regions, but also in areas such as the current territory of Quito where cacao was not locally cultivated. The shape of the vessel in which the residue was found further suggests that the cacao was consumed as a beverage, challenging the previous belief that such practices were primarily confined to Mesoamerica. This study offers new insights into the significance of the cacao bean in pre-Hispanic societies and demonstrates how the application of various chemical methods can enhance our comprehension of historical occurrences.

1. Introduction

Since the findings of cacao (Theobroma cacao) remains at the Santa Ana La Florida Site (SALF), located in the Ecuadorian external slope of the Andes to the Amazon (Zamora Chinchipe province, Ecuador), dated to 3300 BC [1], the geographical origin of cacao and its early distribution switched from Mesoamerica to the Upper Amazon Rainforest [1,2]. This culture, named Mayo-Chinchipe-Marañon based on the relevant hydrological ba-sins, is characterized by early social complexity, ceremonial architecture, a planned spatial layout, and an iconographical repertoire that included cacao pods and other natural elements. Excavations at SALF found archaeobotanical and biochemical remains in two types of contexts (graves and trash pits) and adhered to objects made with two materials (ceramic and stone) artifacts [2,3,4,5,6].

Stirrup-handled bottles, one of the earliest ceramic forms in the Americas, were used to hold various beverages made from different foods, including cacao. Excavations at the SALF site have uncovered one such bottle containing residual evidence in the form of cacao consumption. In contrast, stirrup-handled bottles, which are often associated with the consumption of cacao beverages in Mesoamerica, appeared several centuries later than the earliest bottle forms from South America [7]. This chronological difference indicates that the cultural contexts in which cacao was consumed, and the types of vessels used for that purpose, developed independently in these regions [4]. Archaeological evidence, early radiocarbon dates, and the presence of a high concentration of wild varieties (Herrania and Theobroma families) of the cacao plant allowed Zarrillo and her colleagues [1] to strongly support the hypothesis that the territory where SALF is located was the origin place for Theobroma cacao, as proposed by Valdez (2018) [3], who identified the Amazon Rainforest between Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru as a starting point of its cultural use, domestication, and dissemination.

The widespread dispersion of cacao and its probable area of domestication, as well as the archaeological site with the oldest remains identified until now, have not been thoroughly studied. Valdez (2013) [3] mentioned connections between the Mayo-Chinchipe-Marañón and the Valdivia culture through various symbolic and iconographic elements, along with artifacts that suggest evidence of trade—both direct and indirect—between these two regions. Nevertheless, there remains a significant gap in the literature regarding specific studies on the exchange of cacao. Recent studies have focused on the spread of cacao from the upper Amazon to coastal Ecuador and then to Central America and Mesoamerica using DNA and chemical analysis. These studies that sampled archaeological remains with context and archaeological objects stored in museums (without context) placed the movement of cacao as early as phase III (BC 2950–2600) of Valdivia [2]. This confirms Valdez’s suspicions of early contact between both regions [3].

The aforementioned study of Lanaud et al. (2024) [2] continues with the review of available data and traces the movements of cacao to Colombia (as early as 3000 BC in Puerto Hormiga and San Jacinto contexts), Central America (around 1400–1100 BC at Puerto Escondido, Honduras), and Mesoamerica (as early as 1900 BC in Mokaya and Olmec contexts) [5,8,9,10], with no mention of cacao remains in highland Andean zones, particularly in Ecuador, despite these areas being situated between the proposed center of origin and the coastal region where the earliest evidence of the plant has been documented. Numerous studies have documented the presence of starch granules derived from various plant species across different settlements in the Ecuadorian Andes, including Rumipamba, Tagshima, Llano Chico, Cerro Narrio, Challuabamba, La Chimba, Tajamar, Trapachillo, La Vega, and Cochasquí [11,12,13]. However, none of these studies have reported the presence of cacao starch granules in the analyzed samples. This absence may be attributed to several factors, including the potential exclusive use of cacao in ritual vessels, the limited integration of the plant in trade networks involving Andean settlements, the possibility that the analyzed samples had no historical contact with cacao-based preparations, or the likelihood that starches were not identified due to methodological constraints or the limited focus on cacao in many South American archaeobotanical studies.

As a result, information on the presence of cacao in this region is scarce due to limited research aimed at identifying its starch granules. Furthermore, the cacao plant does not grow above 1300–1400 m a.s.l. Therefore, any cacao remains found in Andean contexts, if identifiable, must have been introduced through interregional circulation routes that were active from the early Formative Period (4000–500 BC) and continued through subsequent chronological periods until the arrival of Europeans [14,15,16,17].

As part of the research for the exhibition, “Taste and Knowledge: A Journey Inside the World of Pre-Columbian Food,” held in the Museo de Arte Precolombino Casa del Alabado, sediment samples were collected and processed at the Research Laboratory of Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural (INPC). The primary objective of this analysis was to identify various morphotypes of starch granules. One of the samples collected from a vessel, identified as part of the Quito culture (AD 500–1500), revealed the presence of starch from numerous plants, including cacao; along with starches from Zea mays (maize) and Canna spp. (achira), as well as a cluster of gelatinized maize starch granules, all of which show evidence of having undergone some form of processing. This work aims to present and discuss the results of the analysis conducted on this particular vessel about the possible presence of Theobroma cacao through starch and chemical analysis of theobromine. The results of this study would demonstrate that cacao and a cacao-derived beverage were not limited to consumption in the Amazon or coastal areas but were also present in Andean settlements and used in food and rituals during the Early Integration Period (AD 500–800).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Archaeobotanical Research in the Collection of Museo de Arte Precolombino Casa del Alabado, Ecuador

As part of the aforementioned temporary exhibition, 23 archaeological vessels from the museum’s collection were selected to gather samples in search of palaeobotanical remains. The exhibit and the research aimed to explore the importance of the food among the pre-Columbian populations of Ecuador, its social significance, the particularities of the production in the Ecuadorian geographic area, and finally, explored six emblematic products of the Ecuadorian traditional food: cacao, manioc, squash, maize, chili and peanut. Among the sampled vessels, an ovoidal anthropomorphic vessel with appliques as eyes and nose was selected for the development of this study. This vessel is identified as part of the grave goods recovered by Porras (1980) [18] during his excavations at Chilibulo and Chillogallo sites and was selected to determine its contents.

This vessel was included in the sampling as the opportunity to connect the findings around the contents with the pot’s contextual and geographical information of provenance. The certainty of the identification was possible thanks to the correlation of the pot, among other archaeological remains, with the information from Echeverría’s thesis and article about the findings made in both sites [19]. This vessel was chosen for analysis as it is the only one associated with the Andean region (specifically from Quito) where cacao starch was identified. In contrast, other vessels contained different types of ancient starch; some contained cacao starch, while others revealed no starch presence. Detailed analyses of each vessel are presented in Table S1 of the Supplementary Material.

2.2. The Anthropomorphic Vessel

The vessel is an ovoidal restricted pot with an elongated and articulated body as shown in Figure 1, which presents similarities with the features mentioned in the identification of the P.Q.Ch.143 type on page 94 of the Echeverría (1976) thesis [20]. The container presents an anthropomorphic face made of appliques, with coffee bean-type eyes and an ovoid nose. Its surface has a rustic smoothing and reddish color, and it is eroded in some areas. Carbon traces and soot concentrations are present on the outer surface.

Figure 1.

The Chilibulo–Chillogallo vessel in which starch and theobromine from cacao were identified. Cod. CKitu02626, Museo de Arte Precolombino Casa del Alabado, Quito, Ecuador.

Based on the shape of the vessel, it can be inferred that it is a jar designed for keeping liquids, indicating that it may have served various types of beverages, such as those traditionally made from maize, manioc, or other tubers [11,13,21]. The vessel has reddish/orange concretions, possibly linked to deposition processes in soils rich in ferrous oxides, common around the Quito Area [21]. The original code of the vessel coincides with the nomenclature given by Echeverría (1976) [20] for the assets of the Chillogallo site: “P.Q.Chg.4” (Pichincha. Quito. Chillogallo. Artifact number). The new code assigned at the museum was “CKitu02626,” where C denotes Culture, Kitu refers to Quito, and the number corresponds to the artifact’s cultural affiliation.

2.3. Provenance and Archaeological Context

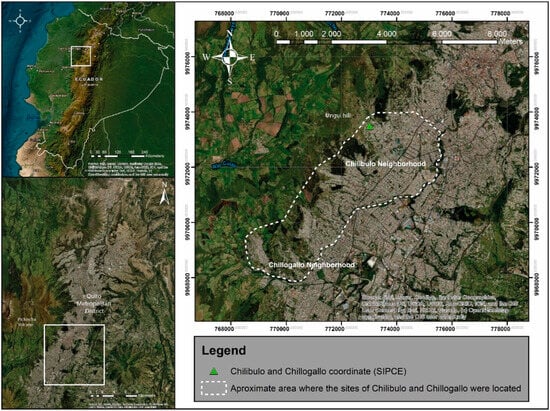

The contextual information situates the findings at a group of sites surrounding the Ungüi hill, in the Chilibulo and Chillogallo neighborhoods on the western flank of the Pichincha volcano, in the southern part of the modern city of Quito, as illustrated in Figure 2. The original catalog code of the artifact, together with its form, surface finish, anthropomorphic decoration, and raw material, are characteristic of the Quito cultural area during the Integration Period. The explorations and excavations were made during the 1970s in areas that were being destroyed by brick, adobe, and tile factories that took advantage of the black clay soils, resulting in the discovery of domestic, agricultural, and funerary contexts [21]. The abovementioned vessel was found at the Chillogallo site, probably as part of grave goods used to contain edible offerings in shaft graves, typical of both sites [19,20].

Figure 2.

Map indicating the possible location of the Chilibulo–Chillogallo sites in the southern region of Quito. Map elaborated using ArcMap.

Chilibulo and Chillogallo are also associated with a system of agrarian terraces covering around one square kilometer between 3000 and 3300 m a.s.l [19]. According to the characteristics of the material culture assemblages and the radiocarbon dates, the occupation is understood to have taken place during the Ecuadorian Integration period (AD 500–1500) and is identified as belonging to the Quito culture [22].

Sadly, the scholars who conducted the fieldwork research did not publish, elaborate, or present detailed maps with the precise locations of the contexts but only reported the names of the neighborhoods where the findings were made as reference [19,20,21,23]. The coordinate 773,026 E/9,973,491 N is available in the platform “Sistema de Información del Patrimonio Cultural del Ecuador, SIPCE” [24], so the inventory sheet of the Chilibulo site can be used as a reference, despite the lack of information about the Chillogallo archaeological site.

For the chronological background, Porras (1980) [19] reported the analysis of charred remains of maize recovered inside a vessel from the intermediate levels of the seriation with the C14 method. The obtained dates are located chronologically between AD 500 and 600. Regarding the dates, the original report with the C14 results was situated at the Porras archive from the Weilbauer-Porras Archaeological Museum of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (File: MW-PP-BD-19-C12-E09) as shown in Table 1. The radiocarbon dating was conducted at the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Rikagaku Kenkyusho, in Wako-Shi, Saitama, Japan, in 1981, using conventional methods; the original report does not provide δ13C values or specify the dated material.

Table 1.

Radiocarbon dating of the Chilibulo–Chillogallo site.

As the results in the report were not calibrated, they were processed using SHCal 20: Southern Hemisphere, OxCal V4.4.4 software based on Hogg et al. (2020) and Ramsey (2009) [26,27], to calibrate them and obtain the plausible ranges of the site’s occupation. Table 1 displays the first two radiocarbon dates, which fall into the Integration period. The style of the published ceramic corpus of the site shows coherence with the characteristics of Quito culture ceramics [19,20,23,28]. The third date, by its range, is attributable to the Period of Regional Development or Early Integration. As mentioned before, the material culture of the site is clearly linked to the ceramics of Integration Period Quito. Ceramics of the Regional Development Period from the Quito area are quite different in style and finish [28,29,30,31], so it is plausible to locate the third date at the Early Integration Period (range extreme date at AD 542).

Finally, the identified ceramic corpus of Chilibulo-Chillogallo presents the same characteristics as the ones excavated at La Florida, located approximately 10 kilome-ters north of the sites, which is 14C dated between AD 520–680 [19,20,32,33].

2.4. Selection of Analytical Methods for Cacao Identification

To identify the optimal analyses for determining the potential presence of cacao in the vessel, we reviewed laboratory analyses performed in previous studies where cacao had been identified in archaeological remains. It is important to note that the research conducted by Zarrillo et al. (2018) [1] in this field is the most comprehensive, as they analyzed starch grains, used liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (UPLC/MS/MS) to identify theobromine, and examined ancient DNA of Theobroma cacao and related species. In their most recent study, the researchers examined multiple variables, including DNA and the alkaloids theobromine, caffeine, and theophylline [2]. The rest of the studies that have identified cacao focused on analyzing a single marker, mainly theobromine or other methylxanthines present in cacao (caffeine and theophylline). Therefore, based on the availability of techniques and samples, we opted to perform two analyses: starch and theobromine.

Table 2 presents a bibliographic overview of main studies focused on cacao detection through archaeobotanical and organic residue analyses.

Table 2.

Main archaeobotanical studies on cacao detection.

2.5. Sample Extraction

The samples were collected from the storage area of the Museo de Arte Precolombino Casa del Alabado; this is a completely isolated location used for handling the museum’s archaeological artifacts. All cleaning and security protocols were implemented to prevent any external contamination. The cleaning and security protocols were developed following the recommendations of Lanaud et al. (2024), Ordoñez-Araque et al. (2024, 2025), and Zarrillo et al. (2018) [1,2,45,46], as well as the laboratory’s regulations. Details of these protocols are provided in the Supplementary Protocol S1 included in the Supplementary Material, which outlines the methodology for treating archaeological samples, guidelines for preventing contamination during starch analysis, and procedures for the chemical analysis of theobromine.

For the analysis, a sterile scalpel was used to scrape the inside of the vessel from the middle to the bottom. Two distinct sections from the interior of the vessel were selected for scraping to avoid sampling from a single location, so a sample was obtained from the right and left sides (a–b) specifically from the interior of the vessel’s body; and in both cases, it was possible to collect residue from the matrix layer rather than solely from the surface. A total of approximately 1.25 g was obtained and subsequently stored in 2 mL Eppendorf tubes for further analysis (starch and chemical analysis for the identification of theobromine). Among the 23 vessels examined in this study, the Quito vessel was selected for research due to its unique association with the Andes region and its positive identification of cacao starch. The results of the analysis for all 23 vessels are presented in Supplementary Table S1 included in the Supplementary Material. The findings indicate that some vessels contained starch from various plant sources, some tested positive for cacao starch, while others exhibited no starch granules.

2.6. Starch Identification

As part of the present study, the research team conducted experiments to identify starch granules using a simulation of pre-Hispanic cooking with corn and potatoes. Archaeological fragments were then analyzed to validate the findings [45]. Based on these experimental simulations, a protocol for identifying starch in archaeological utensils was developed, which established the optimal procedures for extracting and detecting starch from small samples [1,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Different parameters were alternated to establish the most effective approach. The following validated method was employed to analyze a sample of 0.25 g for the presence of starch granules. The sample was placed in an Eppendorf tube and covered with cesium chloride (1.79 g/cm3), which was shaken for 10 min (min) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min (minisSpin—Hamburg, Germany). The resulting floating fraction was transferred to a new tube with distilled water and centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 8 min, and this step was repeated. The supernatant was discarded, and the remaining residue that was believed to contain starch granules was placed on a slide with a drop of glycerol. Identification was performed using an Olympus BX53F optical microscope—Tokyo, Japan. with a built-in Infinity 2 digital camera with polarized capacity. The slide was initially observed with a 10× objective to identify the starches present, then changed to a 40× objective to capture photographs.

Starch obtained from both the seed and mucilage of actual Theobroma cacao was analyzed for comparison. The identification of starch from Theobroma spp. seeds relies on the tear-shaped ovoid granules. These can be classified into three categories: (1) spherical granules with a slightly polygonal shape and a closed hilum, with an average size of 3.8–8 μm; (2) small granules composed of two or three truncated-spherical granules, with either a closed or slightly open hilum, with an average size of 3.8-μm; and (3) ovoid teardrop-shaped starches with an eccentric hilum located at the proximal end of the granule, or a closed or slightly open hilum with one or more fissures. These starches exhibit bending or curving arms when viewed under polarized light, with an average size of 6.3–12.5 μm [1]. An analysis was performed with the actual starch from Theobroma cacao and bicolor to compare with the identified starch. The potential residual starches in the vessel were compared against the laboratory’s collection of starch samples and published archaeological starch studies. Blank samples were analyzed using the same reagents to ensure the validity of the study.

2.7. Chemical Analysis for the Identification of Theobromine

2.7.1. Sample Preparation

Theobromine was measured in samples a and b. Analyses were conducted using a total of 0.5 g of sample for each analysis. The material scraped off the ancient vessel (A–B) was used for the analysis of theobromine through UPLC/MS/MS. In this regard, 0.5 g of this powder was placed into a small volumetric flask of 5 mL and aforated with type I water. Afterward, the volumetric flask was put into a microwave bath (Branson Ultrasonic, Danbury, CT, USA) at 25 °C, and the samples were sonicated for 15 min. Then, the extract of the sample was filtered with a 0.22 µm syringe filter and placed into a chromatographic vial.

2.7.2. Reagents and Materials

Water was a de-ionized Type I from a milli-Q system. Acetonitrile was MS grade from LiChroslv Supelco (Darmstadt, Germany). Theobromine reference standard was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Theobromine stock solution of 0.1 mg/mL was prepared and stored at −20 °C. Also, diluted solutions of theobromine from 5 to 100 µg/L were prepared for quantification.

2.7.3. UPLC/MS/MS System

Analytical separations on the UPLC system were performed using an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 1.7 μm, 100 mm column at a flow rate of 0.45 mL/min. The gradient started with 98% of A (0.1% formic acid in water) and 2% of B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) to 80% A after 2 min, then a linear gradient of 14.5 min to 2% of A with a total separation time of 16.5 min.

A Xevo-TQ-S triple quadruple mass spectrometer (Waters) with an Electro Spray Ionization in positive ion mode (ESI+) was used for the detection, with a capillary voltage of 3.0 kV, extractor cone voltage of 3 V, sample cone voltage of 32 V and detector voltage of 500 V. Cone gas flow was set at 300 L/h and the desolvation gas flow was kept at 1000 L/h. Source and desolvation temperatures were set at 150 °C and 500 °C, respectively. The collision energy varied from 16 to 28 to optimize different daughter ions. As a solution of theobromine standard was used, the spectrometer detected signals of the following transitions: 181 > 138; 181 > 110, and 181 > 67. The elution from the UPLC column were introduced to the mass spectrometer, and the resulting data was analyzed and processed using MassLynx 4.1 software. As described before, two samples (a and b), each weighing 0.5 g, were analyzed. Additionally, a control standard solution of theobromine was measured alongside the blank sample. An external calibration curve was established from the analytical response of theobromine standards across a range of concentrations, and sample responses were quantified by linear regression against this curve.

Previous research has found that methylxanthines may be subject to environmental contamination during the storage of artifacts in museums, human activity associated with the excavation process, and exposure to water and microorganisms [2,43,55]. All necessary protocols were implemented to prevent any external contamination. Consequently, following the recommendation of Lanaud et al. (2024) [2], it has been determined that a sample can be deemed positive for theobromine when the concentration exceeds a threshold of 700 pg/sample (0.5 g), as this amount indicates that the alkaloid is likely to have originated from its millennial use.

3. Results

3.1. Starch

Analysis of the samples revealed a variety of morphotypes of starch granules. A total of 30 starch granules were recovered from the vessel. They were identified and categorized as follows: 15 granules from Theobroma spp., 13 granules from maize (Zea mays), 1 granule from bean (Fabaceae-Phaseolus spp.), 1 granule from achira (Canna spp.), and a cluster that is probably composed of gelatinized maize starch granules.

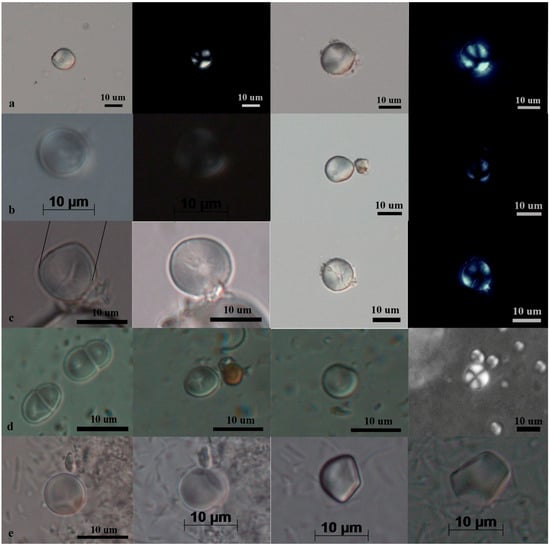

Figure 3a–c illustrates the main starches of Theobroma spp., granules recovered in the vessel. Characterized by an ovoid or teardrop-shape with an open and centric hilum, one or more fissures, and a size ranging between 10–15 microns, these granules exhibit specific features observable under polarized light, including curved arms indicative of this cacao species. Additionally, Figure 3 also illustrates modern reference starch granules of Theobroma cacao (Figure 3d) and Theobroma bicolor (Figure 3e), which were employed for the identification of ancient starches. Although the granules in panels a–d may appear different in shape, they all present the same diagnostic characteristics; the variation is due solely to differences in the magnification at which the photographs were taken.

Figure 3.

Main ancient and modern cacao starch granules under bright-field and polarized light. (a–c) Archaeological Theobroma spp. starch recovered from Chilibulo–Chillogallo vessel; (d) modern comparative starch granules from T. cacao; and (e) T. bicolor (photographs captured using a digital camera attached to an Olympus optical microscope).

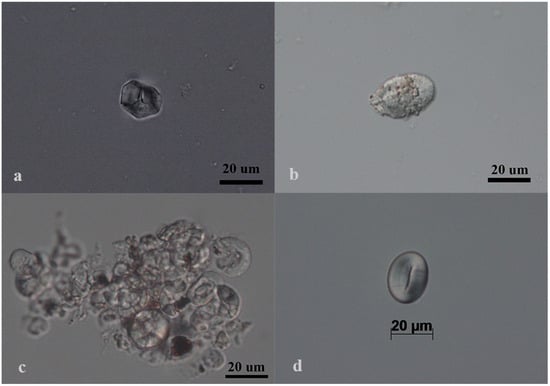

Starch grains from additional specimens recovered from the Chilibulo–Chillogallo vessel were examined under bright-field microscopy. The analysis revealed granules from several plant taxa, including Zea mays (maize) (Figure 4a), Canna spp. (achira) (Figure 4b), a cluster of gelatinized maize starch granules (Figure 4c), and Phaseolus spp. (bean) (Figure 4d). These observations provide further insight into the variety of plant resources processed or stored in the vessel.

Figure 4.

Starch grains from other specimens recovered from the Chilibulo–Chillogallo vessel under bright-field view. (a) Zea mays (maize), (b) Canna spp. (achira), (c) cluster of gelatinized maize starch granules, (d) Phaseolus spp. (bean). Photographs captured using a digital camera attached to an Olympus optical microscope.

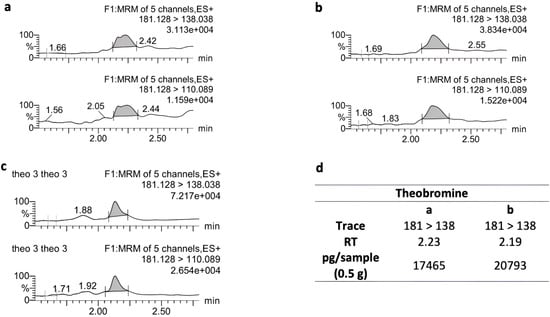

3.2. Theobromine

The UPLC-MS/MS analyses of the samples revealed the presence of a peak at 2.23 and 2.19 min (Figure 5a,b) that matched well with the standard for theobromine (Figure 5c), whereas no peaks were observed in control samples. MS/MS mass spectra of the control standard solution of theobromine, along with the blank sample, are illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1 included in the Supplementary Material. Also, the chromatogram with the transitions m/z Quan Trace 181 > 138; 1st Trace 181 > 110; and 2nd Trace 181 > 67 of the samples and standard are shown in Supplementary Figure S2 and Protocol S1 included in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 5.

UPLC-MS/MS chromatograms of theobromine. (a,b) Samples from the archaeological vessel, corresponding to the Quito Integration period, and (c) theobromine standard solution. (d) Results of theobromine detection in samples (a,b), using UPLC-MS/MS (figures obtained using the UPLC/MS/MS system).

The mass spectra clearly show the presence of the molecular ion of theobromine at 181 and their transition ion fragments as 163 (-H2O), 138 (-HNCO), which confirm that the sample contains theobromine and, therefore, the presence of Theobroma cacao in that ancient food vessel.

4. Discussion

There has been considerable debate regarding the cultivation, domestication, and origins of the cacao beverage, particularly about its preparation and consumption in Mesoamerican and South American civilizations [2,5,56]. Previous assertions suggested that the processing of this beverage, a precursor of modern-day chocolate, was exclusive to Mesoamerican people. Studies have suggested that in South American settlements, only the mucilage from the cacao pod was used as a source of refreshing liquid or to ferment and obtain an alcoholic beverage [35]. However, recent research by Lanaud et al. (2024) and Zarrillo et al. (2018) [1,2] in the Amazon and the coast of Ecuador has contradicted these claims, indicating that cacao plant domestication occurred in South America. According to the findings of the present investigation, it is probable that the Quito vessel contained a non-fermented beverage; however, this cannot be determined with certainty and differs from previous statements.

The identification of cacao methylxanthines in different types of vessels from various sites in South America and Mesoamerica has been linked to alkaloids derived from cacao pod seeds used in the preparation of ritual beverages. The vessels in which the alkaloid theobromine has been predominantly detected show possible similarities to the jug-shaped vessel recovered from the Chilibulo–Chillogallo site. This resemblance is comparable to vessels used for consuming cacao beverages at El Pilar during the Late Classic Maya period [41], as well as the twelve-cylinder jars from Pueblo Bonito where theobromine was also identified [44]. According to Henderson et al. (2007) [35], the wide-necked bottles discovered in Puerto Escondido, which may also resemble the vessel from Quito, are considered the only vessels suitable for producing a foamy chocolate drink according to Mesoamerican tradition. In addition, we can cite LeCount (2001) [57] research, which indicates that cacao was consumed in ancient Maya contexts using wide-mouthed vessels and bowls, while bottles with long, narrow necks are considered unsuitable for preparing the foamy cacao beverage. The author also argues that this practice was exclusive to Mesoamerica. In this regard, the presence of the wide-mouthed vessel analyzed in this study, originating from the Andean region, challenges the hypothesis proposed by LeCount.

To further support the hypothesis that the beverage prepared in Quito was not fermented (i.e., alcoholic), it is important to consider that cacao beans must undergo fermentation and drying before use. Therefore, if the beverage was made from already dried cacao, the sugars necessary for fermentation would have been absent, suggesting that it was likely a non-alcoholic cacao preparation. This interpretation aligns with the research conducted by Crown and Hurst (2009) [44] in Pueblo Bonito, New Mexico. Their research indicates that the exchange of cacao over long distances likely involved the transportation of prepared seeds rather than the entire cacao pod. This preparation process would have entailed fermenting the pulp with the seed, followed by drying and potentially roasting before transport, to enable the recipient to produce the renowned frothy beverage. This approach would have been essential for preserving the cacao beans and ensuring their safe arrival at the intended destination, thus mitigating the risk of damage. It is important to note that if cacao is not fermented, with all or at least part of the mucilage, the beans would be very bitter and unpalatable for consumption [58,59]. Furthermore, a single cacao pod typically contains approximately 30 seeds and has an average weight of 588 g, which is greater than half a kilogram. Conversely, the average weight of the seeds in a cacao pod is noted to be 107 g. Therefore, transporting a cob is four times heavier than transporting the equivalent weight of seeds [50]. Consequently, opting to transport the seeds instead of the cob is more practical.

Due to the average altitude (2800 m a.s.l) and cold climate of the intermontane basin of Quito (14.6 °C/58.2 °F annual average) [60], cacao crops would not be possible at the sites. However, there are two areas with proven contacts in the Integration period from where cacao could have been mobilized: the northwest of Pichincha province and the eastern foothills at the Amazonian province of Napo. At the northwest of Pichincha, there were Yumbo populations, settled on the passage routes between the Andes and the Ecuadorian North Coast, who were recognized merchants from the Integration period until the beginning of the Republic (19th century) [33,61,62,63]. In 1800, cacao crops were reported in Curupuzun (between the current towns of Los Bancos and Pedro Vicente Maldonado [64]) (p. 64). This crop is currently harvested in Nanegal, Nanegalito, Gualea, Pacto, Mindo, and Puerto Quito, all towns situated in the Yumbo cultural area. In the colonial period, the journey from Quito to Puerto Quito would have taken approximately six days, two of them on horseback and four on foot, along narrow [64] (pp. 63–66), possibly culuncos, of pre-Hispanic tradition. As mentioned above, the oldest reported evidence of cacao comes from southeastern Ecuador [1,2]. It is plausible that this crop would have dispersed in a south–north axis, along the Amazon to the upper provinces. Contacts between Quito and the eastern foothills have been widely supported in historical and archaeological records [65,66,67,68,69,70]. Since the pre-Hispanic period, one of the best-known routes of contact between Quito and the Amazon has been the route that starts in Guápulo and takes the Papallacta-Baeza path towards Archidona. This track, even in 1887, took three days on horseback and one on foot to Baeza (1914 m above sea level-still very high for cacao cultivation) and, between four and six more days, to Archidona, the next town of colonial origin (577 m a.s.l) [71]. Given the time and energy required in either option, it is rational to prioritize the transportation of seeds over cobs.

Given these factors, this study is consistent with the interpretation of Crown and Hurst (2009) [44], suggesting that cacao in Quito was also prepared from the seeds themselves, as they proposed for Pueblo Bonito. Moreover, the beverage prepared in their vessels was probably non-fermented and was a non-alcoholic drink originating from the processed bean, possibly resembling a preparation method observed in Mesoamerica [5]. It is plausible to theorize that the initial transfer of cacao in Mesoamerica, before the existence of crops, likely involved the exchange of seeds. A recipe for producing a beverage from the cacao bean was possibly transmitted in this exchange, as the unidentified seed would have had minimal value otherwise. Subsequently, it is conceivable that each community adapted its preparation techniques based on this initial exchange.

It has been established that environmental contamination of methylxanthines can occur during the storage of artifacts in museums as a result of human activity during excavation, exposure to water, and microbial action [2,43,55]. While contamination can never be completely ruled out, the concentration of theobromine provides a strong indication that the alkaloid is unlikely to originate from post-excavation contamination. Following the recommendation by Lanaud et al. (2024) [2], a sample testing positive for theobromine at a threshold of 700 pg/sample (0.5 g) suggests an origin linked to the historical use of the vessel. Our findings of 17,465 pg for sample a and 20,793 pg for sample b substantially exceed this threshold, suggesting that the presence of theobromine is unlikely to result from contamination and more plausibly reflects past use of the vessel. These values also align with pg/sample (0.5 g) concentrations reported in the Supplementary Material of the Lanaud et al. (2024) [2].

Moreover, the detailed protocols and the methodology used in the laboratories, the presence of cacao starch, diverse plant starches, and evidence of cooking processes in the starches further eliminate the possibility of contamination. In the context of identifying theobromine, the concentration detected in the Chilibulo–Chillogallo vessel indicates that the preparations in the jar were made using Theobroma cacao. Based on research by Lanaud et al. (2024) [2], it has been established that other species of Theobroma or the genus Herrania, which contain similar methylxanthines, exhibit significantly lower levels of theobromine compared to T. cacao. For instance, in T. cacao, the main alkaloid is theobromine, which can account for up to 90% of the total methylxanthine content. In the national variety of Theobroma cacao, this proportion can be as high as 98% [72]. Research conducted by Mihai et al. (2022) [73], indicates that the concentration of caffeine in cacao ranges from 190 to 530 mg per 100 g, while theobromine content varies between 1500 and 2540 mg per 100 g, depending on the region of origin. T. cacao can exhibit theobromine concentrations ranging from 1390 to 2034 mg/100 g, while T. bicolor and T. angustifolium contain significantly lower concentrations at 171 and 36.8 mg/100 g [74]. These findings indicate that the theobromine concentration is distinctive for T. cacao. We can also reference Zarrillo and Blake (2022) [5] who note that the detection of theobromine in archaeological samples facilitates the identification of Theobroma cacao. The researchers point out that this alkaloid is present in high concentrations specifically in the mature seeds of T. cacao, while it is not found in Herrania spp. or other cacao varieties. Guayusa is known to contain significantly higher concentrations of caffeine compared to theobromine. For instance, Wise and Negrin (2020) [75] report a caffeine concentration of 36 mg/mL, while theobromine is present at only 0.3 mg/mL. Similarly, Meneses et al. (2024) [76] indicate a caffeine concentration of 3.2% and a theobromine concentration of 0.12%. These much lower levels of theobromine suggest that it is unlikely to adhere to a vessel and be retained over time. The findings of our research confirm the presence of ancient cacao starch, which indicates that theobromine does not originate from other plants like guayusa, as guayusa does not contain starch [77]. Similarly, the possibility of Herrania spp. contributing to theobromine content can be excluded, as Zarrillo et al. (2018) [1] have demonstrated that this plant also does not contain starch. Thanks to the study of the previous researchers, the high concentration of theobromine in the sample not only confirms the presence of cacao but also allows the identification of Theobroma cacao as the specific variety. However, it is important to note that applying biomarker ratios to archaeological samples remains challenging, as the interactions between the clay matrix, the absorbed compounds, and the effects of taphonomic processes are not yet fully understood. Consequently, the relative proportions of theobromine, caffeine, and theophylline may not necessarily reflect their original ratios, as emphasized by Reber in her work on organic residue analysis.

In the present study, we sought to identify the presence of theobromine and starch as markers for determining Theobroma spp. and T. cacao. It is noted that the identification of only one of these variables may lead to uncertainty in confirming the presence of this plant. Furthermore, a study by Ford et al. (2022) [41] in El Pilar (Belize/Guatemala) suggests a possible error in their analysis. They suggested that only the Theobroma cacao plant in Mesoamerica contains the methylxanthine theophylline. They also indicated that a potential false positive in cacao analysis in that region could result from the holly black drink, made with Ilex vomitoria and cassine, if prepared in vessels by individuals from the Gulf Coast regions of the present-day United States, due to the presence of theobromine and caffeine in these species, but not theophylline. Based on the chemical composition, the presence of theophylline in an archaeological sample from Mesoamerica has been proposed as a potential marker for establishing the existence of cacao [42]. Furthermore, various studies have highlighted the occurrence of the three methylxanthines in plant species such as yerba mate (I. paraguariensis), guarana fruit (P. cupana), and the yoco vine (P. yoco), which the Amazonian population has historically utilized. However, it has been indicated that these plants are unlikely to have been distributed throughout the continent, so they cannot be considered for use in the region [40,41,77]. Nevertheless, the species Ilex guayusa can be found in certain regions of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru [78]. This species contains theobromine, caffeine, and theophylline [77,79,80]. In the study conducted by Ford et al. (2022) [41], the authors overlooked the presence of theophylline, caffeine, and theobromine in Ilex guayusa. It is documented that the use of Ilex guayusa as a medicinal plant can be traced back to 500 CE in the Andes, specifically in the Bautista Saavedra province of Bolivia [81]. Notably, the presence of theophylline in artifacts from El Pilar can be dated to 600 to 900 CE, approximately a century after the discovery of the guayusa plant in Bolivia. These findings prompt the hypothesis that if there was trade of cacao between Mesoamerica and South America, there was also potential for trade of the Ilex guayusa from the Amazon to the rest of the continent. Therefore, it is suggested that using two markers to confirm the presence of cacao in archaeological samples to eliminate any doubts or errors is pivotal. This approach was used in the studies by Lanaud et al. (2024) and Zarrillo et al. (2018) [1,2]. For this reason, it is crucial for new researchers to analyze at least two distinct chemical components to accurately identify the presence of cacao (starch an methylxanthines) and if possible, the presence of aDNA.

Regarding the use of museum-stored objects, with and without the context of provenance, as part of broader research projects is leading to promising and important results. In the case of Ecuadorian archaeology, recent work shows new relevant information related to different types of archaeological objects, plant domestication, and pigments [2,82]. Provenance studies and association with similar objects with archaeologically known context in the future, such as the vessel discussed in this study, can, in some cases, contribute to increasing archaeological knowledge.

Finally, it is essential to highlight the significance of the studies by Crown et al. (2015); Crown and Hurst (2009); Ford et al. (2022); Hall et al. (1990); Henderson et al. (2007); Hurst et al. (1989, 2002); Lanaud et al. (2024); Owens et al. (2017); Powis et al. (2002, 2007, 2008, 20011); Washburn et al. (2014); and Zarrillo et al. (2018) [1,2,8,9,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], as they were pioneers in identifying cacao in the pre-Hispanic world primarily through the chemical analysis of theobromine. Their pioneering research has facilitated the advancement of subsequent investigations aimed at uncovering the historical traces of cacao.

5. Conclusions

As presented in this paper, archaeobotanical remains—specifically starches—of Theobroma spp. and biochemical traces of theobromine in the sampled Quito vessel confirm the possible presence of Theobroma cacao in this archaeological object. Even if it is not particularly ancient compared to the cacao traces identified in the Coastal and Amazon regions, these remains are the first identified for the intermontane valleys and allow us to observe the circulation and consumption of cacao in these areas where cacao did not grow. This study also opens a broad perspective on the circulation of cacao in older contexts in the northern Andean highlands. It enriches the discussion about this product’s movement, preparation, and consumption, considering that the presented evidence points to the use of the seeds, probably in preparing beverages, instead of the pulp in fermented drinks.

From the methodological point of view, the combination of two of the three main methods to identify cacao (starch identification, chemical traces analysis (theobromine, caffeine and theophylline), and DNA identification) with positive results will allow effective identification of the plant, as this, and Zarrillo, Lanaud and colleagues’ studies, suggest [1,2]. Also, it is important to state the approximation and study of the museum collection objects as this can present new data and information, other than iconographic, about different research topics as presented in this document. In conclusion, the new data presented in this paper makes it necessary to extend the sample collection to archaeological objects that allow us to track the presence of cacao in the connection points between the Andean valleys, Pacific Coast, and Amazon areas, as well as central and southern valleys of the Ecuadorian Andes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage8120537/s1, Protocol S1: Protocol: contamination prevention in archaeological sample analysis; Table S1: General results from the analysis of starch granules in plants and Theobroma spp.; Figure S1: UPLC-MS/MS chromatograms of theobromine determination in (a) blank sample, (b) mobile phase, and (c) control standard of 2.5 ppb. Figure S2: UPLC-MS/MS chromatograms of theobromine. a and b: samples from archaeological vessel, and c: theobromine standard solution containing the m/z Quan Trace 181 > 138; 1st Trace 181 > 110; and 2nd Trace 181 > 67.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.-P., R.O.-A. and M.R.-B.; methodology, R.O.-A., M.R.-B., J.R.-B., L.R.-G. and E.L.-V.; software, C.M.-P., A.M. (Alexander Medina) and A.M. (Alex Mina); validation, L.R.-G., K.T. and P.V.-J.; formal analysis, P.V.-J.; investigation, M.R.-B.; resources, L.R.-G.; data curation, J.R.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.O.-A.; writing—review and editing, C.M.-P., M.R.-B., L.R.-G., K.T., A.M. (Alexander Medina), A.M. (Alex Mina) and P.V.-J.; visualization, J.R.-B.; supervision, P.V.-J.; project administration, L.R.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data other than those reported in the text are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Board of Directors of the Tolita Foundation and the Museo de Arte Precolombino Casa del Alabado for their essential support in the development of the exhibition and research. We are particularly grateful to Lucía Durán, director of the Museum, for her motivation and guidance throughout the project. We also thank the Museum staff for their assistance during all phases of the research. Our appreciation extends to Ricardo Gutierrez and the Weilbauer-Porras Archaeological Museum of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador for providing access to the archive of radiocarbon dates. We are especially grateful to Eric Dyrdahl for his valuable contributions to the analysis of the chronological context of Quito. Finally, we thank the reviewers for their thoughtful reading of the article and anticipate that their comments will further enhance this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zarrillo, S.; Gaikwad, N.; Lanaud, C.; Powis, T.; Viot, C.; Lesur, I.; Fouet, O.; Argout, X.; Guichoux, E.; Salin, F.; et al. The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaud, C.; Vignes, H.; Utge, J.; Valette, G.; Rhoné, B.; Caputi, M.G.; Nieto, N.S.A.; Fouet, O.; Gaikwad, N.; Zarrillo, S.; et al. A revisited history of cacao domestication in pre-Columbian times revealed by archaeogenomic approaches. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, F. Primeras Sociedades de la Alta Amazonia: La Cultura Mayo Chinchipe-Marañón; IRD Edition: Marseille, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrillo, S.; Valdez, F. Evidencias del cultivo de maíz. Arqueol. Amaz 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrillo, S.; Blake, M. Tracing the movement of ancient cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) in the Americas: New approaches. In Waves of Influence: Revisiting Coastal Connections Between Pre-Columbian Northwest South America and Mesoamerica; Beekman, C., McEwan, C., Eds.; Sheridan Books, Inc: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2022; pp. 121–144. Available online: https://www.csusb.edu/sites/default/files/upload/file/Hepp%202022_Capacha%20problem_small.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Valdez, F. Primeras Sociedades de la Alta Amazonía: La Cultura Mayo Chinchipe—Marañon. In Arqueol. Amaz; IRD Edition: Quito, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers17-07/010070442.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Powis, T.G.; Hurst, W.J.; del Carmen Rodríguez, M.; Ortíz, C.P.; Blake, M.; Cheetham, D.; Coe, M.D. Oldest chocolate in the New World. Antiquity 2007, 81. Available online: https://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/powis314 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Powis, T.; Cyphers, A.; Gaikwad, N.; Grivetti, L.; Cheong, K. Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8595–8600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyphers, A.; Powis, T.G.; Gaikwad, N.G.; Grivetti, L.; Cheong, K.; Guevara, E.H. La detección de teobromina en vasijas de cerámica olmeca: Nuevas evidencias sobre el uso del cacao en San Lorenzo, Veracruz. Arqueología 2013, 46, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Pagán-Jimenez, J. Residuos vegetales antiguos identificados en varios utensilios de preparación de alimentos (sitio arqueológico Cochasquí, Ecuador). In Cochasquí Revisitado: Historiografía, Investigaciones Recientes Y Perspectivas; Ugalde, M., Ed.; Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado de Pichincha: Quito, Ecuador, 2015; pp. 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrillo, S. Human Adaptation. Food Production. and Cultural Interaction during the Formative Period in Highland Ecuador. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Romero-Bastidas, M.; Dyrdahl, E.; Criollo-Feijoo, J.; Mosquera, A.; Ramos-Guerrero, L.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P.; Montalvo-Puente, C.; Ruales, J. Discovering the dietary practices of pre-Hispanic Quito-Ecuador: Consumption of ancient starchy foods during distinct chronological periods (3500–750 cal BP). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 64, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrdahl, E. Obsidian acquisition networks in northern Ecuador from 1600 to 750 cal BCE. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2022, 44, 103530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, F. Inter-zonal Relationships in Ecuador. In The Handbook of South American Archaeology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 865–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugalde, M.; Dyrdahl, E. Sedentism, Production, and Early Interregional Interaction in the Northern Sierra of Ecuador. In South American Contributions to World Archaeology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switerland, 2021; pp. 337–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, F. Los Señores Étnicos de Quito en la Época de Los Incas; Instituto Otavaleño de Antropología: Otavalo, Ecuador, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, F. Los Señores Ètnicos de Quito en la Època de Los Incas: La Economía Polí;tica de los Señoríos Norandinos; Instituto Metropolitano de Patrimonio, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar: Quito, Ecuador, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Porras, P. Arqueología del Ecuador; Gallocapitán: Otavalo, Ecuador, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría, J. Contribución al conocimiento arqueológico de la provincia de Pichincha: Sitios Chilibulo y Chillogallo. Rev. Univ. Católica 1977, 17, 181–218. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría, J. Contribución al Conocimiento Arqueológico de la Provincia de Pichincha: Sitios Chilibulo y Chillogallo; Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, K. Informe de Avance, Resultados de Los Análisis Proyecto: Investigación Arqueológica Mediante Análisis y Estudios de Laboratorio 2023-IMP; Informe Inédito Presentado al; Instituto Metropolitano de Patrimonio: Quito, Ecuador, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Ruales, J.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P.; Ramos-Guerrero, L.; Romero-Bastidas, M.; Montalvo-Puente, C.; Serrano-Ayala, S. Pre-Hispanic Periods and Diet Analysis of the Inhabitants of the Quito Plateau (Ecuador): A Review. Heritage 2022, 5, 3446–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, P. Arqueología de Quito: I. Fase Cotocollao; Centro de Investigaciones Arqueológicas, PUCE: Quito, Ecuador, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- SIPCE. Sistema de Información del Patrimonio Cultural del Ecuador. 2023. Available online: http://sipce.patrimoniocultural.gob.ec:8080/IBPWeb/paginas/inicio.jsf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Mielke, J.E.; Long, A. Smithsonian Institution Radiocarbon Measurements V. Radiocarbon 1969, 11, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, A.; Heaton, T.J.; Hua, Q.; Palmer, J.G.; Turney, C.S.; Southon, J.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Boswijk, G.; Ramsey, C.B.; et al. SHCal20 Southern Hemisphere Calibration, 0–55,000 Years cal BP. Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 759–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, B. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, K. Quito Antes de la Urbe: Dinámicas de Constitución del Espacio Quiteño, Entre el Período de Integración y la Colonia Temprana; FLACSO: Quito, Ecuador, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buys, J.; Domínguez, V. Hace Dos Mil Años En Cumbayá Proyecto Arqueológico ‘Jardín Del Este’; Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural e Instituto General de Cooperación al Desarrollo de Bélgica: Quito, Ecuador, 1988.

- Montalvo-Puente, C.; Juape-Paneluisa, G.; Mosquera, A.; Merino, A.; Dyrdahl, E. Investigación Sobre Arquitectura Monumental En Tierra en el Distrito Metropolitano de Quito; Informe Inédito; IMP: Quito, Ecuador, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, A. Modificación del paisaje y subsistencia durante el Periodo de Integración en la subcuenca del río Pachijal, Pacto, Ecuador. Arqueol. Iberoam. 2022, 49, 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Erazo, R. Yacimiento de La Florida, Quito, Ecuador; Unpublished report from the National Institute of Cultural Heritage of Ecuador, not publicly released; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Molestina, M. El pensamiento simbólico de los habitantes de La Florida (Quito-Ecuador). Bull. L’institut Français D’études Andin. 2006, 35, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powis, T.G.; Hurst, W.J.; del Carmen Rodríguez, M.; Ponciano, O.C.; Blake, M.; Cheetham, D.; Coe, M.D.; Hodgson, J.G. The Origins of Cacao Use in Mesoamerica. Mexicon 2008, 30, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.; Joyce, R.; Hall, G.; Hurst, W.; McGovern, P. Chemical and archaeological evidence for the earliest cacao beverages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 18937–18940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, W.J.; Tarka, S.; Powis, T.; Valdez, F.; Hester, T. Cacao usage by the earliest Maya civilization. Nature 2002, 418, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powis, T.; Valdez, F.; Hester, T.; Hurst, W.; Tarka, S. Spouted Vessels and Cacao Use among the Preclassic Maya. Lat. Am. Antiq. 2002, 13, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.; Tarka, S.; Hurst, W.J.; Stuart, D.; Adams, R. Cacao Residues in Ancient Maya Vessels from Rio Azul, Guatemala. Am. Antiq. 1990, 55, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, W.; Martin, R.; Tarka, S.; Hall, G. Authentication of cocoa in maya vessels using high-performance liquid chromatographic techniques. J. Chromatogr. A 1989, 466, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, S.; Berenbeim, J.A.; Ligare, M.R.; Gulian, L.E.; Siouri, F.M.; Boldissar, S.; Tyson-Smith, S.; Wilson, G.; Ford, A.; de Vries, M.S. Direct Analysis of Xanthine Stimulants in Archaeological Vessels by Laser Desorption Resonance Enhanced Multiphoton Ionization. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2838–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, A.; Williams, A.; de Vries, M. New light on the use of Theobroma cacao by Late Classic Maya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2121821119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crown, P.; Gu, J.; Hurst, W.J.; Ward, T.J.; Bravenec, A.D.; Ali, S.; Kebert, L.; Berch, M.; Redman, E.; Lyons, P.D.; et al. Ritual drinks in the pre-Hispanic US Southwest and Mexican Northwest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11436–11442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, D.; Washburn, W.; Shipkova, P.; Pelleymounter, M. Chemical analysis of cacao residues in archaeological ceramics from North America: Considerations of contamination, sample size and systematic controls. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 50, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crown, P.; Hurst, W. Evidence of cacao use in the Prehispanic American Southwest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2110–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Ramos-Guerrero, L.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P.; Romero-Bastidas, M.; Rodríguez-Herrera, N.; Vallejo-Holguín, R.; Fuentes-Gualotuña, C.; Ruales, J. Fatty Acids and Starch Identification within Minute Archaeological Fragments: Qualitative Investigation for Assessing Feasibility. Foods 2024, 13, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Mosquera, A.; Román-Carrión, J.L.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P.; Ramos-Guerrero, L.; Rivera-Parra, J.L.; Romero-Bastidas, M.; Montalvo-Puente, C.; Ruales, J. Evidence of eared doves consumption and the potential toxic exposure during the Regional Development period in Quito-Ecuador. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofalo, A.; Keegan, W.; Pateman, M.; Pagán-Jiménez, J.; Hofman, C. Determining precolonial botanical foodways: Starch recovery and analysis, Long Island, The Bahamas. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 21, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán-Jiménez, J.; Guachamín-Tello, A.; Romero-Bastidas, M.; Constantine-Castro, A. Late ninth millennium B.P. use of Zea mays L. at Cubilán area, highland Ecuador, revealed by ancient starches. Quat. Int. 2016, 404, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, B.; Herrera-Parra, E.; Pérez, M. Análisis e identificación de almidones arqueológicos en instrumentos líticos y cerámica del conjunto residencial Limón de Palenque, Chiapas, México. Comechingonia Rev. Arqueol. 2021, 25, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán-Jiménez, J.; Rostain, S. Uso de plantas económicas y rituales (médicinales o energizantes) en dos comunidades precolombinas de la Alta Amazonía ecuatoriana: Sangay (Huapula) y Colina Moravia (400 a.C.–1200 d.C.). In Antes de Orellana. Actas del 3er Encuentro Internacional de Arqueología Amazónica; IFEA: Quito, Ecuador, 2013; pp. 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Pagán-Jiménez, J.; Rodríguez-Ramos, R.; Reid, B.A.; van den Bel, M.; Hofman, C. Early dispersals of maize and other food plants into the Southern Caribbean and Northeastern South America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2015, 123, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofalo, A.; Sinelli, P.; Hofman, C. Late Precolonial Culinary Practices: Starch Analysis on Griddles from the Northern Caribbean. J. Archaeol. Method. Theory 2019, 26, 1632–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louderback, L.; Pavlik, B. Starch granule evidence for the earliest potato use in North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7606–7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, J.; Fullagar, R. Starch residues on pounding implements from Jinmium rock-shelter. In A Closer Look: Recent Australian Studies of Stone Tools; Archaeological Computing Laboratory, School of Archaeology: Sidney, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- King, A.; Powis, T.; Cheong, K.; Gaikwad, N. Cautionary tales on the identification of caffeinated beverages in North America. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 85, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCount, L. Like Water for Chocolate: Feasting and Political Ritual among the Late Classic Maya at Xunantunich, Belize. Am. Anthropol. 2001, 103, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Landines-Vera, E.F.; Urresto-Villegas, J.C.; Caicedo-Jaramillo, C.F. Microorganisms during cocoa fermentation: Systematic review. Foods Raw Mater. 2020, 8, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Cañas, G.; Casa-López, F.; Criollo-Feijoó, J.; Landines-Vera, E.F.; Ordoñez-Araque, R. South American fermented legume, pulse, and oil seeds-based products. In Indigenous Fermented Foods for the Tropics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacoto, C.; Barzallo, A.; Asang, S.; Martillo, J. Caracterización morfológica del cacao nacional “Theobroma cacao L.” del cantón Naranjal, Ecuador. Rev. Tecnol.-ESPOL 2022, 34, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEE-MAGAP Generación de Geoinformación Para la Gestión del Territorio a Nivel Nacional Escala 1:25.000. Memoria Técnica, Cantón Quito; Clima e hidrología; Instituto Espacial Ecuatoriano-IEE y Ministerio de Ministerio de Agricultura SIGAGRO-MAGAP: Quito, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: https://www.geoportaligm.gob.ec/proyecto_nacional/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Lippi, R.; Gudiño, A. Palmitopamba: Yumbos e incas en el bosque tropical al noroeste de Quito (Ecuador). Bull. L’institut Français D’études Andin. 2010, 39, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, F. Los Yumbos, Niguas y Tsatchila o ‘Colorados’ Durante La Colonia Española: Etnohistoria Del Noroccidente de Pichincha; Quito Ediciones Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, J. Plan Del Camino de Quito al Río Esmeraldas Según las Observaciones Astronómicas de Jorge Juan y Antonio de Ulloa; Publicaciones del Archivo Municipal: Quito, Ecuador, 1942. Available online: https://biblioteca.culturaypatrimonio.gob.ec/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=63537 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Oberem, U. Los Quijos: Historia de La Transculturación de Un Grupo Indígena En El Oriente Ecuatoriano; Instituto Otavaleño de Antropología: Quito, Ecuador, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. Relaciones Entre Las Sociedades Amazónicas y Andinas Entre Los Siglos XV y XVII. Las Vertientes Orientales de Los Andes Septentrionales: De Los Bracamoros a Los Quijos. In Al Este de los Andes; Institut français d’études andines, Centro Cultural Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 1988; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, E. La Cerámica Cosanga del Valle de Cumbaya, Provincia de Pichincha (Z3B3-O22): Una Aproximación a la Definición de su rol en los Contextos Funerarios del Sitio La Comarca; Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral: Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, A.; Coloma, M.; Sánchez, F. Rumipamba Bajo la Sombra del Pichincha. Estudio de Complementación de Datos Actualísticos Parque Arqueológico—Ecológico Rumipamba; Informe Final Inédito Entregado al FONSAL; Instituto Metropolitano de Patrimonio: Quito, Ecuador, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, A.; Chacon, R.; Ugalde, M.; Mejia, F. Rumipamba Bajo La Sombra Del Pichincha; Informe Final Inédito Entregado al; Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural: Quito, Ecuador, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, S. Etnoarqueología de Intercambio de Bienes y Productos en los Caminos Precolombinos de Pichincha y Napo; Universidad Politécnica del Litoral: Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre, F. Viaje de Exploración al Oriente Ecuatoriano, 1887–1888; Centro Cultural Abya Yala del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Timbie, D.; Sechrist, L.; Keeney, P. Application of high-pressure liquid chromatography to the study of variables affecting theobromine and caffeine concentrations in cocoa beans. J. Food Sci. 1978, 43, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, R.A.; Abarca, P.A.L.; Romero, B.A.T.; Florescu, L.I.; Catană, R.; Kosakyan, A. Abiotic Factors from Different Ecuadorian Regions and Their Contribution to Antioxidant, Metabolomic and Organoleptic Quality of Theobroma cacao L. Beans, Variety “Arriba Nacional”. Plants 2022, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotelo, A.; Alvarez, R. Chemical Composition of Wild Theobroma Species and Their Comparison to the Cacao Bean. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991, 39, 1940–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, G.; Negrin, A. A critical review of the composition and history of safe use of guayusa: A stimulant and antioxidant novel food. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2393–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, M.; Guzmán, J.; Cabrera, J.; Magallanes, J.; Valarezo, E.; Guamán-Balcázar, M.d.C. Green Processing of Ilex guayusa: Antioxidant Concentration and Caffeine Reduction Using Encapsulation by Supercritical Antisolvent Process. Molecules 2024, 29, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, R.; Mendes, O.; Roy, S.; McQuate, R.; Kraska, R. General and Genetic Toxicology of Guayusa Concentrate (Ilex guayusa). Int. J. Toxicol. 2016, 35, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo-Garcia, M.; Guadalupe, J.J.; Rowntree, J.K.; Borja-Serrano, P.; Monteros-Silva, N.E.d.L.; Torres, M.d.L. Assessing the genetic diversity of Ilex guayusa loes., a medicinal plant from the ecuadorian amazon. Diversity 2021, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, B.; Montero, A.; Mollocana, D.; Calderón, D.; Torres, M. Optical aptasensor for in situ detection and quantification of methylxanthines in Ilex guayusa. ACI Av. Cienc. Ing. 2022, 14, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Kelebek, H.; Sasmaz, H.K.; Aksay, O.; Selli, S.; Kahraman, O.; Fields, C. Exploring the Impact of Infusion Parameters and In Vitro Digestion on the Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Guayusa (Ilex guayusa Loes.) Tea Using Liquid Chromatography, Diode Array Detection, and Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Foods 2024, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas, J.; Jarrett, C.; Cummins, I.; Logan–Hines, E. Amazonian Guayusa (Ilex guayusa Loes.): A Historical and Ethnobotanical Overview. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Polo, A.; Briceño, S.; Jamett, A.; Galeas, S.; Campaña, O.; Guerrero, V.; Arroyo, C.R.; Debut, A.; Mowbray, D.J.; Zamora-Ledezma, C.; et al. An Archaeometric Characterization of Ecuadorian Pottery. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-Puente, C.; Lago, G.; Cardarelli, L.; Pérez-Molina, J. Money or ingots? Metrological research on pre-contact Ecuadorian “axe-monies”. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 49, 103976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).