Abstract

The PHEND (Past Has Ears at Notre-Dame) collaborative research project is being carried out by a team of multidisciplinary researchers interested in the acoustic history of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. The project involved the creation of seven digital models representing the interior of the monument between 1182 and 2018. To support one of the virtual reconstructions, that of 1868, a technical report was drawn up based on the written and iconographic archives of the restorations carried out between 1845 and 1870 by the architects Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) and Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus (1807–1857). The archives come mainly from the “Fonds Viollet-le-Duc”, from the work diary of the “Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie” (MPP), and from the archives of the Notre-Dame chapter. In order to select the most relevant data for the digital reconstruction, the research addresses specific questions regarding the cathedral’s materiality, such as structural modifications, restorations, and the choice of materials and furnishings. To understand how the interior of the cathedral was transformed in the 19th century, a detailed inventory of its condition was compiled at two points in time: at the beginning of the restoration in 1848 and following its completion in 1868. In parallel with this work, to provide a graphic representation of the changes that had occurred in each area, comparative illustrations were produced showing the situation before and after restoration. The modifications were then detailed by area: general restoration (vaults, openings, paving), and redevelopment of the choir and the main body of the building (chapels, transept, nave). This research revealed the building’s profound structural changes and the fact that the renovations spared no space. These included mainly modifications to the high windows, a complete redesign of the decorative layout of the choir and chapels, the restoration of all the vaults and paving at different levels, and a complete restoration of the organ.

1. Introduction

On the 6th of March 1868, the main organ of Notre-Dame de Paris was inaugurated1, marking the end of the official cathedral restoration carried out by two architects, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. After a competition organized in 1842 by the Ministry of Justice and Cults, as part of a growing awareness of the deteriorating state of the building2, they were chosen by the newly created Monuments historiques Commission. For almost 30 years, between 100 and 300 workers from a wide range of specialized trades occupied the cathedral: sculptors, locksmiths, carpenters, masons, upholsterers, painters, glaziers, glass painters, marble workers, organ specialists, bronze workers, and goldsmiths [1]. This restoration involved extensive architectural alterations, major repairs to several elements of the building, finishing work (second oeuvre), and a major overhaul of the furniture, most of which can still be seen today in the edifice.

In 2021, the beginning of the PHEND (Past Has Ears At Notre-Dame) collaborative project involved the creation of seven digital models representing the interior of the monument between 1182 and 2018 [2]. In support of these virtual models, created by Maxime Descamps and Germain Morisseau from the architectural agency Sunmetron, historical studies have been carried out for the earliest periods, from 1182 to 1804, by historian Cristina Dagalita. For the date of 1868, which is of interest here, a large amount of archival material had to be processed. To understand the state of the cathedral and the extent of the internal modifications, the entire restoration was subjected to a detailed technical report to which this article refers. Questions focused mainly on the materiality of the cathedral, i.e., structural modifications, alterations, and the choice of materials used during these restorations. The aim was also to document some of the ephemeral decorations used for specific events, as well as the choice of furniture at the beginning and end of the 19th century. Although attention has been paid in the original report to the general organization of the worksite, these elements are only briefly mentioned here3.

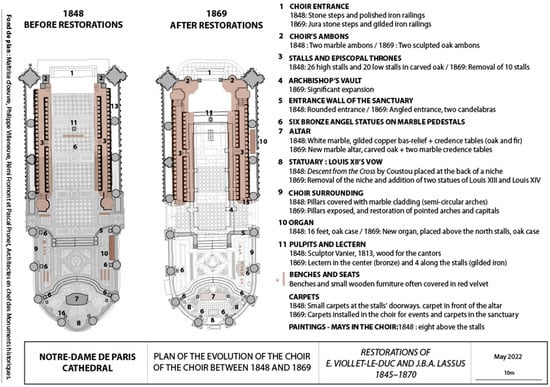

To create a virtual reconstruction of the cathedral as it was in 1868, it was first necessary to study how it had changed as opposed to its previous state, chosen in 1848, i.e., at the very beginning of the restoration. This date was also chosen because of the existence of a furniture inventory in 18484, which allowed a direct comparison to be made. The following three areas have been defined for diachronic comparison: areas where general restoration work has been carried out (vaults, openings, paving, etc.), the choir, restored in 1858, and the body of the building (transept, nave, aisles, and chapels). In conjunction with this work, and to graphically capture the changes, comparative summary illustrations before and after the restoration were used to show the changes in each area in terms of architecture and furnishings in detail.

The original work manuscript was divided into two volumes. The first traced the major stages of interior construction work and included a detailed chronology, information on how the work was organized in the 19th century (including key figures, interior investments, and a summary of materials used), and summary illustrations. The second volume presented a detailed analysis of the work carried out in the aforementioned spaces: vaults, openings, pavements, choir, transept, nave, aisles, and chapels. This article, written after the completion of the modeling, enabled us to present parts of the modeling results following this archival study.

Throughout the study, the need to balance historical issues with the requirements of 3D designers and acoustic researchers was a key consideration. The first important question was how to sort through the large amount of data and which archives should be chosen in order to complete the detailed modeling and meet the acoustician’s needs. The second part of this article presents the results and answers to the following major questions: What did the restoration entail, and which areas of the cathedral were modified? 1. The first complete timeline of the various stages of the interior restoration. We will therefore examine which milestones were chosen for this timeline, the stages of the restoration process, and how the architects organized the work. 2. The reconstitution work will focus on the cladding and covering of the cathedral, as this study is directly linked to the study of materials and their impact on acoustics. 3. Work on the furnishings enabled us to finalize the entire model, including the organ placement, chapel decorations, and choir layout, bringing the cathedral to life in 1868.

2. Materials and Methods: Using the Archives for 3D Reconstitution

As the building is particularly well known, it was envisaged in the early stages of this research project that it would have access to an already well-established bibliography. It was therefore rather unexpected to find that there was no monograph detailing the restoration of the cathedral in the 19th century, and few specialized studies focusing on the interior restorations carried out by the two architects. Several general works provide a good understanding of the architectural evolution of the building since the 11th century, with 3D model support [3], as well as its material composition [4]. However, none of these works has been precise enough to allow a detailed three-dimensional reconstruction of the interior of the cathedral during the period studied here. In existing specialist studies, we observe that the focus of scholarship has been mainly on the exterior work. This is to the detriment of the sometimes-considerable interior interventions, which include not only the restitution of the rose-windows in the triforium [5], the paintings in the chapels, and the rearrangement of the choir [6]. It should be added that the monographs [7], devoted to Viollet-le-Duc, examine his role in 19th-century restorations, as well as his choice of materials and construction techniques [8]. However, they provide little or no technical information on the specifics of the work during the Notre-Dame de Paris restoration. Two recent writings make exceptions: Olivier Poisson’s article, “Notre-Dame de Paris et sa restauration au XIXe siècle: une chronologie [1]”, and a technical report on the cathedral’s vaults, drawn up in 2020 by the RÉA historical research agency, which gives a chronological overview of all the work carried out on them [9].

In contrast to the lacunar nature of these secondary sources, the progress of the project is documented by a very large number of archives. The most important of these, which form the basis of this research, are the archives of the architectural office and the “fonds Eugène Viollet-le-Duc5”. It contains estimates, working notes, pictorial annexes, correspondence, accounts, projects, plans, elevations, and drawings, kept at the Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie (MPP). In addition, the “Work protocol6” (Journal des travaux), written by the site supervisor7 throughout the project, details the restoration work, day by day, and provides an insight into daily life at the site between 1844 and 1865. Other documents, from the collections of the National Archives, include exchanges between the archdiocese and the State, as well as numerous memoirs of construction work8. Finally, we can immerse ourselves in the daily life of the Cathedral during its construction: thanks to the registers of the deliberations of the Council of the Fabric between 1847 and 1893 and the notebooks of the chapter between December 1845 and December 1874. They also offer a glimpse of the various ceremonies, some with very detailed descriptions of the settings. Within the same collection, two inventories, one from 1848 and the other from 1869, describe the furniture in the building before and after the restoration9.

Descriptions of the cathedral, written in the publications of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and their contemporaries, were also used in the modelling. When the competition for the restoration of the cathedral was launched in 1842, the two architects presented their first project: an illustrated architectural–historical study, Projet de restauration de Notre-Dame de Paris [10]. Although this first project was largely later adapted to the reality of the site and the historical interpretations of the architects, it has the advantage of representing the state of the cathedral in 1843. Some ten years later, Description de Notre-Dame, cathédrale de Paris [11], co-authored by Viollet-le-Duc and Ferdinand de Guilhermy, and the Histoire, description et annales de la basilique de Notre-Dame de Paris [12], published by M. Dubu, respectively, in 1856 and 1854, completed this overview. Finally, the decoration of the chapels is described in its entirety in the work of Maurice Ouradou and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc: Peintures murales des Chapelles de Notre-Dame de Paris [13]. In addition, articles, sometimes by Viollet-le-Duc himself, on parts of the cathedral undergoing restoration, like choir enclosures, were frequently published in architectural journals of the time, such as the Revue des architectes et du bâtiment and the Revue générale de l’architecture et des Travaux publics [14].

The modeling process relied heavily on visual archives, i.e., engravings, paintings, drawings, plans, sketches, elevations, and the recently invented photography. Some of these photographs, preserved in the archives of the Notre-Dame de Paris chapter, allowed the discovery of the first restoration version of the choir in 1863. The photographer, Médéric Mieusement (1840–1905), also documented the interior of the cathedral after its restoration in the last quarter of the 19th century [15]. Details of the furniture, architectural decorations, or sculptures were also found in the hundreds of drawings by the Viollet-le-Duc architectural agency.

From this extensive range of resources, we selected a comprehensive collection of all the archives relating to the restoration work being carried out inside the building. After this selection, we proceeded with a chronological classification of the data, separating the iconographic archives from those relating to the details of the work. Then, it became mandatory to create three majors synthetic tables of the following:

- -

- All the contractors who have worked on the cathedral, including their names, areas of expertise, dates of work, and known interventions.

- -

- The materials used in each area, including location, structure, architectural elements, materials, and sources.

- -

- The furnishings and decorations of the chapels, including the name of the chapel, the statues, the furnishings, the type of decoration, and the sources.

Added to this work, three graphic representations have been created to clearly show how the furniture moved inside the building between the two chosen extreme dates of 1848 and 1868. This shows the situation before and after the restoration of the nave, transept, chapels, and choir. Finally, to ensure a clear understanding of the process, the steps involved in the modification were detailed chronologically by area: general restoration (vaults, openings, paving); redevelopment of the choir, chapels, transept, and nave.

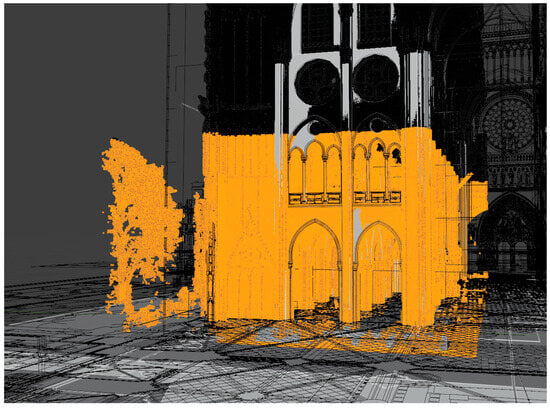

The design work began with the point cloud from Andrew Tallon’s 2012 lasergrammetric survey campaigns [3]. Combined with architectural plans and furniture models supplied by “Art Graphique et Patrimoine”, these documents made it possible to capture every detail of today’s cathedral (Figure 1). The open-source software used for modeling was Blender 2.80, and for textures: Adobe Substance Painter 9.0, and Unreal Engine 5.0 for lighting and rendering.

Figure 1.

Modeling in progress: drawing on point cloud and map ©M. Descamps, G. Morisseau, Sunmetron.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Establishing a Chronology

Once the various archives had been classified, a chronology of the Cathedral’s interior work was drawn up, which made it possible to structure the stages of modeling. However, the work did not stop at modeling alone, and the chronology also includes historical elements that are not visible in the images. The overall timeframe of the restoration has been divided into four phases, taking into account only the elements relating to the interior of the cathedral (Table 1). The first phase, between 1845 and 1850, included the first campaign to restore the vaults, the modification of the upper bays, and the creation of rose windows. This work resumed in 1853. In 1858, workmen began the actual interior work, which included the complete restoration of the choir, the construction of the spire, work on the transept and nave, and the restoration of the chapels. Although work was officially suspended in 1864, it continued until 1869, particularly with the construction of the new main organ and the creation of a decorative scheme for the chapels. This summary is only an overview of all the work that has been performed. It lists only the most important elements.

3.1.1. First Phase—1845–1850

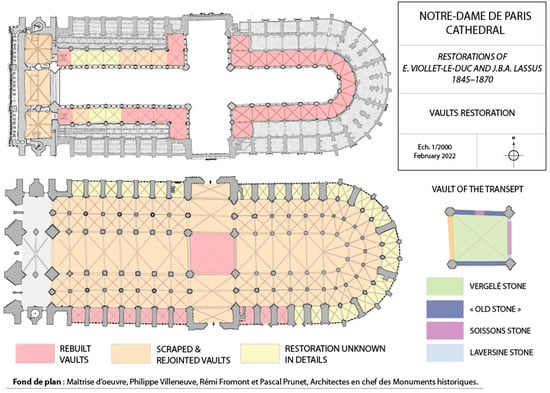

At the beginning, between 1845 and 1850, the work was financed by an initial general credit of 2,650,000 francs10, before further credits of between 100,000 and 500,000 francs were granted each year from 1852 to 1869 on the basis of the work to be carried out in the coming year. This first phase of the restoration work involved very few internal modifications and included the construction of a new sacristy to replace the one built by Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713–1780) in the 18th century. Its construction was accompanied by the renovation of the chapels on the south side of the choir11 (destruction and reconstruction of the walls to create and close the pass through) and the restoration of the vaults on the same side, which are inextricably linked to the work on the flying buttresses. This work on the vaults is the beginning of their large restoration campaign, carried out between 1846 and 1862 [9], from repointing to rebuilding (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Vaults restoration ©H. Borne, Sunmetron.

A second large campaign began in 1849 and ended in 1859. It concerned the creation of rose windows, in the triforium of the nave, and replacing the high windows in the transept and choir12. This is one of the major modifications for the modeling: a total of twenty small rose windows and four different frame models were created in the choir and transept. In the nave, a single model was placed in each of the twelve bays13. These profound modifications, which still shape the cathedral today, were carried out after the hypothesis of an ancient elevation of the cathedral on four levels [5], and the discovery in March 1849 of fragments of three roses in the small walls above the tribune vaults14. The reconstruction process is systematic: demolition, installation of the keystones forming the arches, realization of the rose arcatures, before installation of the frame and fittings for the stained-glass windows. The cathedral remained open for worship for most of the restoration period, and the correspondence between the architects and the archdiocese gives us an insight into the life of the cathedral during this time span. To facilitate this cohabitation, Pierre-Charles Caffin and Octave Samuel Mirgon, joinery contractors, were commissioned to erect half-timbered panels according to the areas occupied, closing off bays, partitioning chapels, and insulating part of the cathedral15.

3.1.2. Second Phase—1853–1858

The second phase of the work took place after an almost total standstill for three years (1850–1853) due to a lack of funds. In 1853, work resumed on the vaults of the triforium of the choir and nave on the north side and the chapels on the south side. At the same time, work continued on the openings on the south side of the choir, the nave, and part of the transept, before the rose windows on the north side of the nave were realized. In 1853, the projecting niche of the chapel of Notre-Dame-des-Sept-Douleurs at the end of the radiating chapel was demolished16. The same year, two temporary sets were installed: in January for the wedding of Napoleon III and Eugénie de Montijo, and in June for the baptism of the Imperial Prince. The vaults of the nave, the transept, and the choir were painted, and bleachers were installed17. As the transept was separated from the nave by a wooden framework, the installation of a temporary choir began in 1857. Finally, in July 1857, the funeral of the architect Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus took place, leaving the architect Viollet-le-Duc in charge.

3.1.3. Third Phase—1858–1864

The most important work on the interior of the building began in 1858 with the complete restoration of the choir18. Its architectural aspect was radically altered: it still retained much of the complete ornamentation created in the 18th century, consisting of a marble pavement and a marble covering hung on the pillars and the lancet arches. The architect undertook the demolition of this marble and the thorough restoration of the 14 pillars, the arches, and the capitals, which were badly damaged. The entire marble paving, including the steps and the marquetry part of the sanctuary, was also removed and then restored with slight modifications to the decoration. The restoration work included the rebuilding of the red sandstone low wall at the sanctuary entrance, the installation of new wrought-iron railings around the choir, and the work on the statuary. The archbishop’s vault under the choir would also be enlarged and rebuilt. All these changes were carried out at the same time, as a new spire19 was raised through the central vault. Restoration work was then carried out in the nave from 1861 (paving, furniture, railings, etc.), where Viollet-le-Duc organized the work one bay at a time to avoid disrupting services20. In fact, during the entire period of restoration, the cathedral was only closed to worship from 1 July to 20 December 1862. Until 1864, the transept and nave were fitted out, and restoration work began on the chapels: restored, painted, and furnished. Regarding the openings, the last small rose windows were built in the choir and transept, and the great rose window of the south transept was removed, and the arch was mounted with a 15° rotation.

3.1.4. Last Phase—1864–1869

The final phase lasted until 1869, after the official suspension of work in May 1864. It consisted mainly of meticulous work in the chapels of the Cathedral, with the final creation of the decorative setting (installation of stained-glass windows, painted decorations, installation of railings and woodwork in certain chapels, creation of furniture, etc.). The final work on the vaults, bays, and paving was also completed at the same time as the reconstruction of the three furnaces (calorifères). This phase also coincided with one of the restoration’s highlights: rebuilding the main organ by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, inaugurated in 1868.

Table 1.

Chronological table of the main interior works and their locations ©H. Borne, Sunmetron.

Table 1.

Chronological table of the main interior works and their locations ©H. Borne, Sunmetron.

| Time Period | Principal Interior Restorations | Location | TR N° (Cathedral Bays/Travées, for Vaults and Windows) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1845 – 1850 | Building site installation | General | |

| Removing old whitewash from the cathedral | General | ||

| Restoration of the vaults | South choir triforium | TR01 to TR22 | |

| South nave chapels | TR36 to TR38 | ||

| Choir chapels | All | ||

| Closure of the passageway to the new sacristy | South choir chapels | TR18 | |

| Creation of the passageways to the new sacristy | South choir chapels | TR16 and TR20 | |

| Removal of paintings from the nave | Nave | ||

| Rose windows creation | South choir triforium | TR10-TR14/TR06-TR08 | |

| Restoration of the openings | South choir triforium South choir chapels South high windows | ||

| Dismantling the west rose and erecting a masonry wall | Nave | ||

| Removal of paintings from the nave | Nave | ||

| 1853 – 1858 | Restoration of the openings | North choir chapels | TR01-TR07/ |

| South choir triforium | T13-TR17 | ||

| South nave high windows | TR26-TR40 | ||

| South choir high windows | TR16, TR12, TR04 | ||

| South nave chapels | TR28-TR34 | ||

| North nave chapels | TR27-TR31 | ||

| Rose windows creation | North choir triforium | TR13-T21 | |

| South nave triforium | TR28-T34 | ||

| South transept (west side) | TR24-T26 | ||

| North nave triforium | TR27-TR29 | ||

| Demolition of the niche “Notre-dame des Sept Douleurs” | Radiating chapel | ||

| Installation of four new bells | South tower | ||

| Installation of the frame and of the stained-glass windows in the large rose window on the main façade | Nave | ||

| Restoration of the vaults | North choir triforium | TR03-TR21 | |

| North nave triforium | T39 | ||

| South nave triforium | TR26-TR40 | ||

| South nave chapels | TR26-TR34 | ||

| 1858 – 1864 | Rose windows creation | North nave triforium North transept (east side) | TR31-TR37 |

| South choir triforium South transept (east side) | TR16 to T20 | ||

| Restoration of the openings | North nave chapels Choir high windows | ||

| Removal and complete restoration of the choir paving | Choir | ||

| Excavation of the former archbishops’ vault and complete reconstruction with extension | Choir | ||

| Demolition of the marble decor of Robert de Cotte | Choir | ||

| Work on the 14 pillars of the choir: inlays, sculptures, and plastering21 | Choir | ||

| Reconstruction of the sanctuary perimeter | Sanctuary | ||

| Removing the Mays | Choir | ||

| Demolition of the choir niche | Sanctuary | ||

| Restoration of the vaults | North nave chapels North choir triforium North transept High vault of the choir Side aisle of the choir Choir chapels High vaults of the nave Side aisle of the nave | ||

| Construction of the spire | Transept | ||

| Work on the stained-glass windows | General | ||

| New belfry | North transept | ||

| Reconstruction of the transverse arches at the entrance to the choir and north transept | Choir North transept | ||

| Removal of the north transept rose and reinforcement of the gallery below with cast-iron columns | Transept | ||

| 1864 – 1869 | Installation of three furnaces | General | |

| Completion of paving work in the chapels, transept, and nave | Chapels Transept Nave | ||

| Work on the large rose window | South transept | ||

| Construction of a stone chimney in the first chapel of the south nave | South nave chapels | ||

| Fitting out chapels: wood paneling, furnishings, construction or restoration of sculptures on special monuments, fencing, decorative paintings, etc. | General | ||

| Restoration of the main organ and its case | Nave | ||

| Restoration of the sculpted choir enclosure | Choir | ||

| Installation of the iron gallery balconies | South triforium | ||

| Installing new stained-glass windows | General | ||

| Drums installation | Nave | ||

| Furnishing | Nave, transept, and chapels | ||

| Installation of light arms on columns, pillars, and chandeliers | Nave Choir |

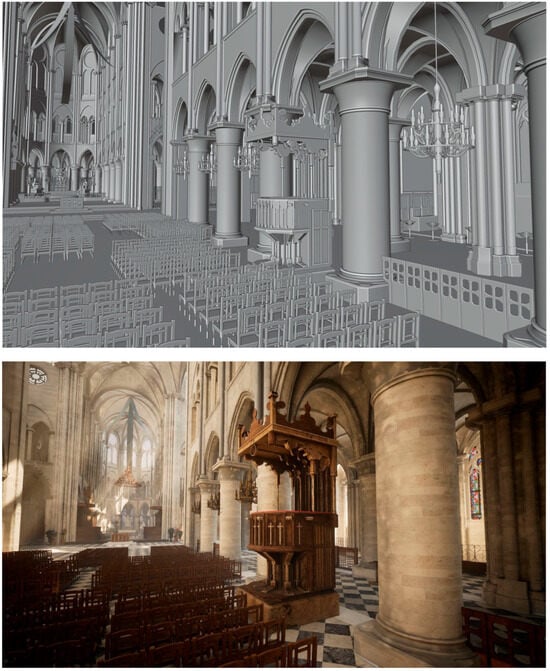

3.2. Cladding the Cathedral: Materials

To enable the modelers to get as close as possible to the materiality of the cathedral, an inventory was made of the types of materials used during the restoration: for the paving, walls, pillars, windows, and vaults. The overall study of the materials present in the cathedral has already been partially studied in “La grâce d’une cathédrale” [4] (pp. 47–65). Here, only the materials mentioned in the restoration archives are listed. Based on the synthesis of this information, the modelers created and reworked the textures to add realistic detail, simulate the wear and tear of time, and the natural variations of stone, wood, or metal (Figure 3). To illustrate the research process, we have chosen to focus this section first on the restoration of the cathedral’s little-known paving and then to present an extract from the general table produced to summarize the wealth of information.

Figure 3.

View of the 19th-century model, before and after texturing ©M. Descamps, G. Morisseau, Sunmetron.

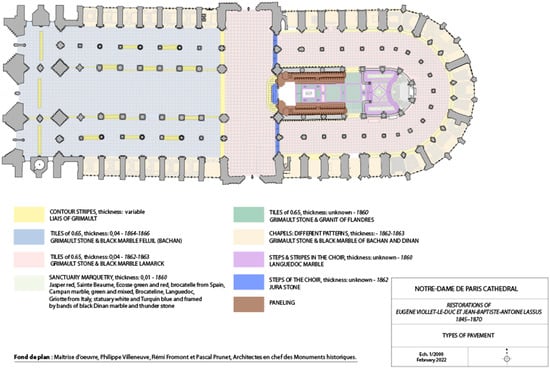

3.2.1. Case Study: Cathedral Paving

For the study of floor covering, most documents are from the archives of Louis François Bernard, a marble mason in Paris22, unless otherwise specified. Between 1858 and 1867, he wrote a series of appendices on the paving work in the cathedral23. This source has been supplemented by a careful reading of the Journal des travaux, the architects’ estimates, and various survey and project plans24. This analysis is accompanied by a summary plan of the type of paving on the ground floor of the cathedral (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Paving layout ©H. Borne, Sunmetron.

The study of the changes made to the existing pavement when Viollet-le-Duc began work on the choir was carried out by comparing the plan of the sanctuary drawn by Robert Bénard in the 18th century with the current plan. The comparison shows a change in some patterns, such as those behind the choir, at the north and south entrances, and at the bottom of the steps at the entrance to the sanctuary, and for the extension of the archbishops’ vault25. In a serious state of deterioration, the marble paving was completely removed in 185826. On the sanctuary side, the marquetry has been restored using different types of polychromic marble, while a simpler tiled floor of liais (limestone) and Flanders granite was laid at the entrance to the choir27. All the steps were also redone in Languedoc marble for the entrance to the sanctuary, and Jura stone28 for the steps leading to the aisles and the entrance to the choir. A strip of liais is laid to receive the communion grille in front of the entrance steps to the choir29. Estimates show that half of the existing marble is reused, as are the staircases in Languedoc.

In the transept and nave, the pavement has been restored in its entirety, matching the existing pavement. It is made up of tiles alternating between liais Grimault stone (white stone) and black marble (Féluil and Lamarck, apparently indistinguishable), with Grimault stone in between. The work lasted from 1861 to 1866 and involved replacing most of the existing paving and reusing a few materials. Restoration of the nave began with the central part, between the columns from the transept to the columns of the main organ. The architects proceeded from bay to bay, starting with the left side and then moving to the right, before completing the south and north aisles.

In the chapels, refurbishment began in 1859 and was completed in 1866, with the same type of marble paving as in the nave and transept: tiles of liais and black marble (from Dinan or Bachan30). It is also worth noting that six chapels in the south aisle have been completely retiled, due to a lowering of the floor following a change in step height. In some chapels, such as that of Belloy, the floor was not completely renewed, but only some of the black marble and liais tiles were replaced. The materials are similar for all the chapels, and only the thicknesses and the widths differ.

3.2.2. Table of Materials Identified in the Archives

The original table also included materials for furniture, statuary, and decorations, but we have chosen to present here a simplified version (Table 2), along with an example of a study of the archives concerning the paving of the entire building. Liais and Vergelé correspond to a type of limestone from the Oise region (France), such as Saint-Maximin or Saint-Leu.

Table 2.

Identifying the materials in the cathedral © H. Borne, Sunmetron.

3.3. Decor and Furnishings

In the final modeling phase, set elements and furniture were added. Most of the furniture in the cathedral in 1868 dates from the restoration by Viollet-le-Duc, who set in motion a true creative process illustrated by precise drawings of numerous pieces. Inspired by his research on the medieval cathedral, these 19th-century elements were the result of the coordinated work of the architect and many artists from various disciplines: goldsmiths, cabinetmakers, bronze workers, sculptors, painters. Some of the furniture (stalls, for example) and existing statuary have been preserved, and in the choir, the 18th-century statuary resulting from Louis XIII’s vow has been reinstated. To achieve the most accurate reproduction possible, several seemingly minor details were also considered, such as the nave barriers and the arrangement of the benches, which shed light on the building’s circulation. Many sources were consulted, including the inventories of 1848 and 1869, which provide detailed information on the elements present but not on the exact positions of furniture or decorative elements. It was therefore necessary to supplement this information with documents related to the fieldwork: estimates, correspondence with the clergymen, attachments, project drawings, etc. These sources have been combined into a series of synthetic visuals to recreate a state as close as possible to the layout and furnishings of the cathedral.

3.3.1. Choir: Between Creation and Restoration

Over the centuries, this space has been redesigned several times according to the architectural tastes of different periods and the relationships between the celebrants and the worshippers, as shown by the previous modeling work performed for the project. These transformations also greatly impacted the acoustics of the celebrations [16]. Thus, at the end of the 12th century, the choir was first delimited by a low enclosure, marking the space reserved for clerics, before a high enclosure, the jube, was erected from the 13th century onwards, linking the eastern pillars of the transept crossing. In the 14th century, a carved stone fence was added to this jube, parts of which are still preserved on the north and south sides [17] (p. 245). During the reign of Louis XIV, major new developments began under the direction of Jules Hardouin-Mansart (1646–1708) [18] (p. 30), superintendent of the king’s buildings, and then the architect Robert de Cotte (1656–1735), who was responsible for an extensive decorative program known as the “Vœu de Louis XIII” (Vow of Louis XIII). In the 19th century, when Viollet-le-Duc began work on the interior, the choir still had the marble covering on the pillars, inherited from the 18th century. However, much of this decoration was mutilated, particularly during the French Revolution, and some of the bronze ornaments have disappeared. Later, the statues of Kings Louis XIII and Louis XIV were moved to the Louvre in 183131.

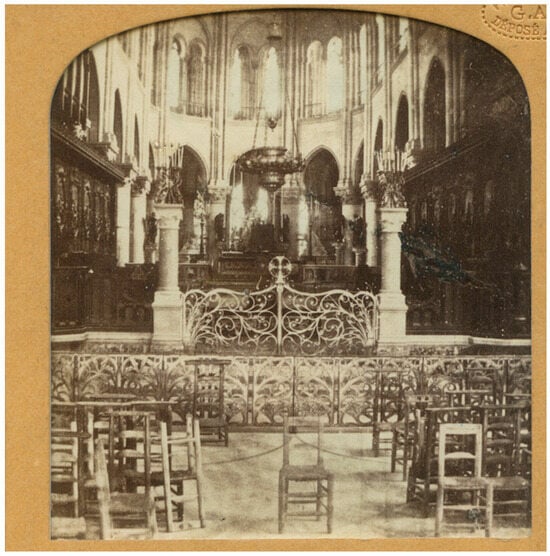

Before the restoration in 184832, the choir was entered through an ornamented gilded iron grid, installed at the beginning of the 19th century33, and bordered by two marble ambos. On each side were 26 high and 20 low stalls in carved oak, ending in two episcopal thrones. The tribunes were decorated with eight paintings, the Mays, hung in the nave and choir34 [19]. At the entrance to the sanctuary, a low circular balustrade was surmounted at either end by two candelabras [20]. This was followed by the statuary dating back to the 18th century: Nicolas Coustou’s “Descent from the Cross”, Girardon’s gilded bronze “Entombment”, and six bronze angels holding the instruments of the Passion, designed by Pierre Puvis de Chavanne. In the middle stood a high altar in white marble and gilded bronze. Finally, there was a range of shared furniture: armchairs, gondola chairs, credenzas, and stools.

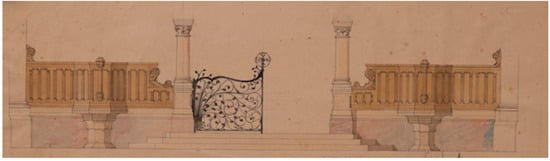

To obtain a clear post-restoration schema, it was possible to rely on several layout plans drawn by Viollet-le-Duc35, as well as on photographs from the period36 (Figure 5 and Figure 6). There have been major architectural reconstructions (low walls, railings, steps, tiles…), as well as the introduction of a whole new range of decorations and furniture (Figure 7). The architect had already set out his program in 1845 and reaffirmed it in his notes around 1850. He wanted to “reconcile the requirements of the construction, the unity of style that was necessary for such a building, and the respect that had to be paid to the wishes of Louis XIII”. All the existing statuary has been preserved, and the marble statues of Louis XIV and Louis XIII by Nicolas Coustou and Antoine Coysevox, dating from 1715 and kept at the Louvre since 1831, have been repatriated37. The marble decoration, which was incomplete and mutilated38, was removed, as well as the Mays in 1856 for the christening of the imperial prince39. At the center of the sanctuary, the main altar, an important part of the new furnishings, was placed in the same place as the old one40. To the left, the celebrant’s seat was placed on a small platform with three steps, accompanied by three armchairs and two folding chairs. From September 1859, the balustrade wall at the entrance of the sanctuary, above the steps separating it from the choir, was built, surmounted at either end by two candelabras. The 18th-century oak choir stalls have been reinstalled exactly as they were when they were removed, except for the removal of ten stalls at the top and bottom. The bishop’s thrones, of similar construction, were moved and placed at the entrance to the choir. The carpentry work was carried out by Pierre-Charles Caffin and Octave Samuel François Mirgon41, who also worked on the woodwork sideboard for the new choir organ. Located above the stalls, in the second choir bay on the north side, for the instrumental part, the work has been carried out by the J. Merklin-Schütze et cie company42.

Figure 5.

View of the choir’s ambones (extract) ©LP-ArchNDP372.

Figure 6.

January 1861. Layout plan and elevation of the choir entrance (extract) ©Ministère de la Culture (France), MPP, diffusion GrandPalaisRmn Photo, F/1996/83/395-37794.

Figure 7.

Comparative diagram of the layout of the choir between 1848 and 1869. The same type of drawing has been performed for the transept, the nave, and the chapels ©H. Borne, Sunmetron.

Other elements that could have an impact on acoustics were studied in the report, such as all the carpets and rugs on the stalls and installed in the sanctuary [13] (p. 333)43. The large tapestry from the Royal Tapestry Manufactory, used for the christening of the Count of Paris and, on certain occasions, placed in the choir to cover the marble floor, is particularly noteworthy for attenuating sound reflections and reducing reverberation.

For the design of the choir, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc also collaborated with Placide Poussielgue-Rusand, a renowned 19th-century liturgical silversmith, for much of the furniture and small liturgical items. The choir’s archives contain numerous projects and drawings from the 1860s: chandeliers, monstrances, candlesticks, reliquaries, candelabra, lecterns, torches, etc., which are not described here because they have no bearing on the acoustics or the architectural reconstruction.

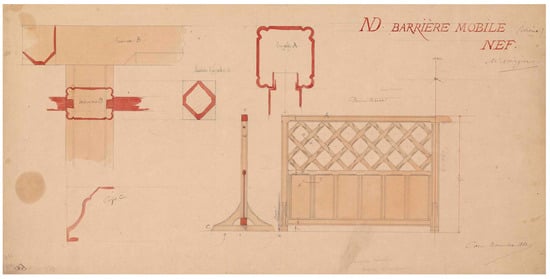

3.3.2. Nave and Transept

The information on the furnishings of the nave and transept is incomplete and less detailed. Some of the layout plans drawn by the architect, such as the one of July 186244, give an idea of the plans for the layout, as well as elevations and plans for unique pieces: movable altars, gates, and fences (Figure 8). These elements were supplemented by photographs [15]. One of the most important pieces, the pulpit45, built around 1869 by Mirgon and Anthine Corbon to designs by Viollet-le-Duc46, was placed on the south side under a lancet arches47 (T32) in place of the old one. As early as October 1865, a number of polished oak barriers, mobile or otherwise, were installed in the nave and aisles, to be moved around as events unfolded48. A space in the center was reserved for chairs.

Figure 8.

November 1862. Mirgon. Mobile barriers for the nave bays, plan, elevation @Ministère de la Culture (France), MPP, diffusion GrandPalaisRmn Photo, F/1996/83/173-1751.

In the transept, the furnishings are mirrored: on either side of the north and south doors, there is an oak altar surmounted by a decorated and gilded tabernacle, as well as a confessional. To the south, the altar is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, whose effigy is surmounted by a canopy sculpted and gilded by Corbon to designs by Viollet-le-Duc49. To the north, it is Saint-Etienne. In the center, in front of the two pillars at the entrance to the choir, the 14th-century statue of the Virgin Mary, known as Notre-Dame de Paris, is leaning against the south-east pillar of the transept, following a request from the Chapter in 186150. On the other side, a marble statue of Saint-Denis by Nicolas Coustou is leaning against the north-east pillar [15]. The two statues are surrounded by a circular gilded iron grid. In the aisles of the nave and choir ambulatory, a decorative program is also installed and realized: old and new statuary, light fittings, railings, etc., detailed in the 1869 inventory.

Another important element in the final rendering of the model was the study of the various lighting fixtures in the building. Integrated into the creation process, they were designed by Viollet-le-Duc and the goldsmiths Edmond-François Lethimonnier and Placide Poussielgue-Rusand. They consist of gilded bronze chandeliers hung from the arches in 186551, light arms hung from the nave columns52 at the entrance to the nave, the choir, and at organ level53, and two light holders placed in 1862 on the choir entrance small columns54. Finally, in the middle of the transept, a large crown of light in varnished and gilded copper (Figure 9) replaced a solid silver lamp depicting the twelve apostles [12] (p. 37).

Figure 9.

Modelisation of the nave in the 19th century ©M. Descamps, G. Morisseau, Sunmetron, associated with 1982, Médéric Mieusement. View of the nave @Ministère de la Culture (France), MPP, diffusion GrandPalaisRmn Photo, MMF016360.

At the entrance to the nave, the cathedral’s new organ, restored by the famous organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-coll, was inaugurated in 1868, after five years’ work55. From June 1864, he set up his restoration workshop inside the cathedral, in the grand gallery of the southern nave56. Warehouses were provided by the administration and located in the attic of the aisles adjoining one of the church’s side galleries57, for the storage of deposited organ parts58. Work on the organ case, completed by Mirgon59, took place between 1864 and 1865, with reconstruction of the case seating system: truss, stone seating, and joists. The woodwork and balustrades on the inside of the gallery were later carved [21].

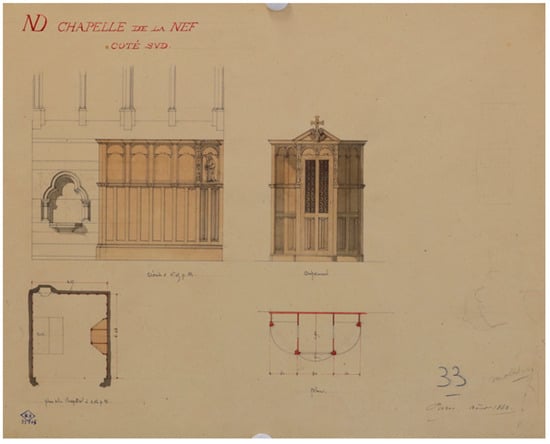

3.3.3. Chapels

The chapels were fitted out at the very end of the architect’s restoration work. As most of the chapel restorations took place after the official completion date, the archives are less complete. However, it is possible to establish a general chronology, thanks to the Journal des travaux (which stops in 1865), and contractor files (carpentry, painting, marble work…). We can also rely on the numerous project drawings (Figure 10), correspondence, and Fabrique Council registers, as well as the monograph by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Maurice Ouradou, which details the choice of paintings for each chapel, created from 1864 to 1869 [13].

Figure 10.

August 1862. Chapel on the south side of the nave, plan of the chapel, elevations of the paneling and confessional @Ministère de la Culture (France), MPP, diffusion GrandPalaisRmn Photo, F/1996/83/173-1751.

The various archives describe the chapels as almost abandoned, and this was one of the cathedral’s most eagerly awaited restorations60. When the workers move into the chapels, they are first completely emptied before large temporary wooden panels are installed. These are then reused in subsequent chapels as work progresses61. As the decoration of the chapels was not subject to government funding, the architect appealed to donors62. The 1848 and 1869 inventories provide details on the furnishings, but it is difficult to determine their exact locations. Although elements varied from nave chapel to nave chapel, they all follow the same pattern: an altar and a carved wooden confessional. Some of them, like the Saint-Pierre chapel, were also adorned with wood paneling. In the choir, each chapel had its own altar, except for rooms used for passageways or storage, the office, and the chapel of Saint-Guillaume. Depending on the chapel, we also found a variety of furnishings: tabernacles, vases, prayer stools, furniture, candlesticks, shower racks, desks, credenzas, and crosses.

As with the choice of furnishings for the nave and choir, Viollet-le-Duc produced many drawings, ranging from small objects to larger pieces such as funerary monuments: for the Marshall Guébriant and his wife63, Christophe de Beaumont, ancient archbishop of Paris64, Antoine Léonor Le Clerc de Juigné, Hyacinthe Louis de Quélen, and Cardinal Louis Antoine de Noailles. Several of which have been created by the sculptor Geoffroy de Chaume. Similarly, in the baptismal fonts chapel, the baptistery was created by the goldsmith Louis Bachelet in 1860, based on designs by Viollet-le-Duc.

All the chapels have been painted, and regarding the decor, Viollet-le-Duc collaborated with numerous artists. For the Saint-Georges chapel, for example, Louis Steinheil was entrusted with the decoration. In April 1867, painter Théodore Maillot was commissioned by the Minister of the Emperor’s Household and Fine Arts to execute the paintings required to decorate the Chapelle Saint-Marcel65. Between 1864 and 1867, restoration work was also carried out on sculptures in several chapels, described very briefly in the attachments of the contractor Marchant: capitals, rosettes, and altarpieces66.

For modeling purposes, summary tables of all the furniture and paintings in the chapels have been created. However, for reasons of time and interest, these have been largely simplified. It is also important to mention that, in the 19th-century numeric model, the chapels were studied less than other parts of the cathedral for modeling purposes, as the final result focused mainly on the nave, transept, and choir.

4. Discussion/Conclusions

The interior work studied here was just one part of a large-scale restoration project involving the organization of a monumental 19th-century worksite, which took almost 30 years to complete. First of all, the 1868 virtual model in its final form revealed the most significant interior differences between the ‘before restoration’ and ‘after restoration’ versions, as designed by the architects Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus. However, the model could not visually capture the series of subtle modifications and reconstructions that could only be identified through archival analysis. The numerous written and iconographic archives left by the two architects revealed an interior restoration that spared no space inside the cathedral. While the choir is the most visible example, having undergone a complete transformation in terms of both architectural structure and furnishings, including the creation and selection of statuary, it is important to note that the same work was carried out in the nave, the transept, and the chapels. In addition, elements that were completely invisible without consulting the archives were uncovered, such as all the restoration work on the vaults: some of these had been completely destroyed and rebuilt. The paving of the choir was also removed and rebuilt almost identically, as were those of the nave, transept, and chapels. Not only has it been interesting to document the changes, but also the administrative organization behind this restoration work. This has allowed us to record the methods used and the reasons behind the choice of materials and furnishings in the 19th century. Another important aspect was establishing a first clear chronology of the work carried out inside the cathedral during this period by selecting relevant milestones.

Thirdly, it highlights the importance of considering not only the current physical state of a building to understand its history, but also all the stages of construction and restoration that have shaped its appearance, thanks to archives. This is also directly linked to understanding how the cathedral was used in past periods and what it sounded like during everyday life, masses, or ceremonies. The study of architectural changes and furniture rearrangements enabled acoustic researchers to collect data through measurement, simulation, and analysis of materials and surfaces. These scientific measurements and digital archeological acoustic reconstructions have also been carried out on other major historical buildings, such as the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the Cathedral of Saint-Paul [22]. It adds a new dimension to the conservation of buildings: preserving their acoustic heritage.

Finally, this 19th-century virtual model and the other six are powerful tools for visually representing and conveying cutting-edge acoustic research to the public. They allow the audience to experience the cathedral’s history through virtual reality, based on its audio history, and demonstrate how alterations to the architecture, furniture, and décor can significantly affect the acoustics. These virtual models were also used to create the visual basis for the animated film “Vaulted Harmonies”, a 60-min virtual concert. Featuring models from all periods, the film transports viewers through the history of Notre-Dame Cathedral using sound and visuals [23,24].

Author Contributions

Investigation, resources, writing—original draft preparation, H.B.; validation, supervision, project administration, E.R. and G.M.; 3D modeling, M.D. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding has been provided by the European Union’s Joint Programming Initiative on Cultural Heritage project PHE (The Past Has Ears, phe.pasthasears.eu), the French project PHEND (The Past Has Ears at Notre-Dame, Grant No. ANR-20-CE38-0014, phend.pasthasears.eu), and the Chantier scientifique CNRS/Ministère de la Culture/Notre-Dame.

Data Availability Statement

The two full reports Les restaurations intérieures de la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris entre 1845 et 1869: rapport historique pour une reconstruction architecturale et acoustique (vol1,vol2), that this article is based on, can be found at: 10.5281/zenodo.17229038.

Acknowledgments

First of all, we would like to thank Brian Katz for giving us the opportunity to work on this fascinating subject. We would also like to thank the members of his team, especially Cristina Dagalita, whose iconographic research enabled us to create models for all the years prior to the 19th century. We would also like to thank the historian Marjorie Bourgoin, for her invaluable assistance with going through the numerous archives. Finally, I would like to thank Alexandre Houdas, Dominique Caron, and Don Means for their careful French and English proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | 6th of March 1868, Chapter notebook, VII, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 2 | 16th of May 1845, Session of the deputies’ chamber, Diocesan archives, 2D-3D, File n°4, and 16th of October 1849, Letters from Lassus and Viollet-le-Duc to the Minister of Public Instruction and Cults, MPP, E/81/7523/7-13. |

| 3 | The complete study summarized in this article was divided into two volumes: the first traces the main stages of the interior work, with a chronology, details of the organization of the site (actors, used materials, etc.), and synthetic illustrations. The second volume presents a detailed analysis of the work carried out in the above-mentioned areas. |

| 4 | A. Hauser, Interior view of Paris Cathedral, 1847; 1848, Inventory of the cathedral’s furnishings, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 5 | MPP, F/1996/83 and F/1998/35. |

| 6 | Journal des travaux MPP, E/80/14/10. |

| 7 | Emile Boeswillwald from 1845 to 1852, Pierre Emile Queyron from 1853 to 1858, and Maurice Ouradou from 1858. |

| 8 | French National Archives, F19/7800-7812 and F21/1451. |

| 9 | Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 10 | 23rd of March 1853, Report from the Ministry of Public Instruction and Cults, MPP, F/1998/35/16-70. |

| 11 | 27th of June 1846, Letter from the architects to the Prefet, MPP, F/1998/35/23-106. |

| 12 | 1849, Authorization from the Arts and Religious Buildings Commission, MPP, E/81/7523/7-13. |

| 13 | 1858, Restoration of rose windows between the 1st and the 2nd flying buttress, MPP, F/1996/83-89-27. |

| 14 | 19th of March 1849, Letter from Viollet-le-Duc, MPP, F/1998/35/23-106. |

| 15 | September 1847, Journal des travaux. |

| 16 | 15th of September 1853, Journal des travaux, p. 228. |

| 17 | 14th of June 1856, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 18 | 19th of November 1857, Report by Viollet-le-Duc to the Ministry of Public Instruction and Cults, French National Archives, F/19/7805, File no40. |

| 19 | 12th of January 1858, Note from the Ministry of Public Instruction and Cults, French National Archives, F/19/7805, File n°40. |

| 20 | 8th of February 1860, Letter of Viollet-le-Duc to the Ministry of Public Instruction and Cults, MPP, F/1998/35/24-107. |

| 21 | 1859, Statements of the daily expenses of the masonry contractors, Sauvage and Milon, MPP, F/1998/35/2-12. |

| 22 | 12th of February 1858, Submission by marble contractor Bernard, MPP, F/1998/35/13-53. |

| 23 | 1858-1867, Statements of the daily expenses of the contractor Bernard, MPP, 1998/35/2-13. |

| 24 | Undated, Two plans of the choir and the transept with indications of the pavements, MPP, F/1996/83. |

| 25 | 16th of May 1860-1st of September 1860, Journal des travaux, pp. 334–337. |

| 26 | 1858, Journal des travaux, p. 298. |

| 27 | May 1871, Estimate for damage made by the Commune, MPP, F/1998/35/19-84. |

| 28 | 10th of July 1861, Journal des travaux, p. 346. |

| 29 | Ibid. |

| 30 | 2nd of November 1859, Estimate no 5 for marble work, MPP, F/1998/35/7-29. |

| 31 | 19th of May 1856, Note from Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Diocesan archives, 2D-3D. |

| 32 | op.cit., 1847, Inventory of the cathedral’s furnishings, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 33 | 19th century, C. Percier, Grille separating the choir from the nave, BNF, FOL-VE-53. |

| 34 | 16th of July 1850, Letter from the Director of the Cults Administration to the architects, MPP, F/1998/35/23-106. |

| 35 | 27th of July 1859, Plan of the choir with an indication of the planned furniture, MPP, F/1996/83. |

| 36 | Undated, View of the sanctuary after restoration by Viollet-le-Duc, MPP, Amis, XXI. |

| 37 | ca.1857, Estimate no 9, MPP, F/1998/35/8-32. |

| 38 | 19th of May 1856, Note by Viollet-le-Duc concerning the restorations, Diocesan archives, 2D-3D. |

| 39 | See note 29 above. |

| 40 | 1869, Inventory of the cathedral’s furnishings, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 41 | February 1858, Submission by joinery contractor, Caffin et Mirgon, MPP, F/1998/35/13-53. |

| 42 | 10th of February 1863, Letter from the Ministry of Public Instruction and Cults to the Prefect of the Seine, French National Archives, F/19/7802, File no6. |

| 43 | 1905, E. Atget, Stalls, north side, MPP, APMH00038836. |

| 44 | July 1862, Plan of the last three bays of the nave, the transept, and the choir entrance, MPP, F/1996/83. |

| 45 | February 1863, Preacher pulpit, MPP, F/1996/83. |

| 46 | 29th of September 1869, Letter from Viollet-le-Duc to the Ministry of Public Instruction and Cults concerning the liquidation of the works, MPP, F/1998/35/17-73. |

| 47 | 28th of November 1845, Letter from the Archbishop of Paris, MPP, F/1998/35/23-106. |

| 48 | 1869, Inventory of the cathedral’s furnishings, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. 25th of October 1865, Journal des travaux, p. 386. |

| 49 | See note 40 above. |

| 50 | 30th of April 1861, Chapter notebook, VII, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 51 | 20th of August 1865, Journal des travaux, p. 386. |

| 52 | 21st of April 1864, Journal des travaux, p. 378. |

| 53 | 1st of September 1865, Crown of light project, MPP, F/1996/84. |

| 54 | 5th of April 1862, Journal des travaux, p. 355. |

| 55 | 15th of July 1863, Submission by organ builder A. Cavaillé-Coll, French National archives, F/19/7807, File no17. |

| 56 | 27th of June 1864, Chapter notebook, VII, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 57 | 1864, Cavaillé-Coll organ builder’s account, MPP, Fonds des “Amis”, XXXIV. |

| 58 | 17th of July 1863 and 1st of August 1863, Journal des travaux, pp. 370-371. |

| 59 | 15th of January 1864, Letter from Cavaillé-Coll to Mirgon, MPP, Fonds des “Amis”, XXXIV 1. |

| 60 | 15th of December 1850, Viollet-le-Duc and de Lassus report to the Ministry of Cults, French National Archives, F/19/7805, File no33. |

| 61 | 1856, Statement of the daily expenses of the contractors Caffin et Mirgon, no2, MPP, F/1998/35/2-14. |

| 62 | 14th of February 1865, Chapter notebook, VII, Archives of Notre-Dame’s chapter. |

| 63 | 12th of February 1867, Letter of Viollet-le-Duc to the Comte of Guébriant, MPP, 1998/35/1-9. |

| 64 | 20th of October 1863, Letter of Viollet-le-Duc to the Ministry of Public Instruction and Cults, French National Archives, F/19/7800, File no8. |

| 65 | 29th of April 1867, Letter from the Senator, Superintendent of Fine Arts, to Viollet-le-Duc, MPP, F/1998/35/11-48. |

| 66 | 1847–1867, Ornamental sculpture contractor’s files, Marchant, MPP, F/1998/35/5-22. |

References

- Poisson, O. Notre-Dame de Paris et sa Restauration au XIXe Siècle: Une Chronologie. Available online: https://www.scientifiquesnotre-dame.org/articles (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Mullins, S.S.; Katz, B.F.G. The Past Has Ears at Notre-Dame Cathedral: An Interdisciplinary Project in Digital Archaeoacoustics. Acoust. Today 2024, 20, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandron, D.; Tallon, A. Notre-Dame de Paris, Neuf Siècles D’histoire; Parigramme: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fonquernie, B.; Gatouillat, F.; Mouton, B.; Viré, M. Les matériaux mis en œuvre. Pierre, métal, bois, polychromie, verre. In La grâce D’une Cathédrale; La Nuée Bleue: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, C. Les roses dans l’élévation de Notre-Dame de Paris. Bull. Monum. 1991, 149, 153–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, A.; Lanc, L.; Mayer, L.J.; Pillet, E. Les grandes restaurations. XIXe siècle. In La Grâce D’une Cathédrale; La Nuée Bleue: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bercé, F. Viollet-le-Duc, 2nd ed.; Éditions du Patrimoine-CMN: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Timbert, A. (Ed.) Matériaux et techniques de construction chez E. E. Viollet-le-Duc. In Actes du IIe Colloque International de Pierrefonds; Éditions du Patrimoine-CMN: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- RÉA. Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, Voûtes, Étude historique et documentaire. 2020; unpublished, interim report. [Google Scholar]

- Lassus, J.-B.-A.; Viollet-le-Duc, E. Projet de Restauration de Notre-Dame de Paris (1843): Pour Mieux Penser la Rénovation à Venir; Espaces & Signes: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guilhermy, F.; Viollet-le-Duc, E. Description de Notre-Dame, Cathédrale de Paris; Bance: Paris, France, 1856. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6568964k.texteImage (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Dubu, M. Histoire, Description et Annales de la Basilique de Notre-Dame de Paris; Ambroise Bray: Paris, France, 1854. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bd6t541867223 (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Leniaud, J.-M. Monographie de Notre-Dame de Paris Suivi de Peintures Murales des Chapelles de Notre-Dame de Paris par Maurice Ouradou et Eugène Viollet-le-Duc; Éditions Molière: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Viollet-le-Duc, E. Serrurerie, Grilles du chœur de la Cathédrale de Paris. Gazette Architectes Et Du Bâtiment 1863, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, I.; Désiré dit Gosset, G. Notre-Dame, la Cathédrale de Viollet-Le-Duc par Médéric Mieusement; Trans Photographic Press: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield-Dafilou, E.K.; Katz, B.F.G.; Chevallier, B.C. History and Acoustics of Preaching in Notre-Dame de Paris. Heritage 2024, 7, 6614–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefoy, R. La clôture du chœur. In La Grâce D’une Cathédrale; La Nuée Bleue: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Album des Boiseries du Chœur de Notre-Dame de Paris Connues Sous le Nom de Vœu de Louis XIII; Achille Chauvet et Cie: Paris, France, 1855.

- Canfield-Dafilou, E.K.; Mullins, S.S.; Katz, B.F.G. Can you hear the paintings? The effect of votive offerings on the acoustics of Notre-Dame. In Proceedings of the Forum Acusticum 2023, Torino, Italy, 13 September 2023; pp. 2537–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, M. La Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, Notice Historique et Archéologique, 2nd ed.; D.-A. Longuet: Paris, France, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandro, C.; Canfield-Dafilou, E.K.; Mullins, S.S.; Katz, B.F.G. The position of Gothic organs in Notre-Dame de Paris: Architectural evidence, acoustic simulations, and musical consequences. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 231, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.F.G.; Weber, A. An acoustic survey of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris before and after the fire of 2019. Acoustics 2020, 2, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.F.G.; Pardoen, M.; Lyzwa, J.-M.; Peichert, S.; Cros, C.; Poirier-Quinot, D.; De Muynke, J.; Ling, A.; Cacheux, S.; Griner, J.; et al. The Past Has Ears at Notre-Dame: Immersive audio experiences for public engagement. In Proceedings of the 156th Audio Engineering Society Convention, Madrid, Spain, 15–17 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier-Quinot, D.; Lyzwa, J.-M.; Mouscadet, J.; Katz, B.F.G. Vaulted Harmonies: Archaeoacoustic concert in Notre-Dame de Paris. Acoustics 2025, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).