Abstract

This study presents the preliminary results of the design and implementation of an advanced data management infrastructure developed to enhance the study, interpretation, and preservation of historical and archaeological contexts. Conducted within the framework of the PNRR CHANGES Project, Spoke 6, the initiative promotes the integration of scientific research, digital innovation, and cultural heritage enhancement. One of the principal outcomes of the project is the development and configuration of ARPAS (“Analisi del Rischio nel Paesaggio Stratificato” or “Risk Analysis of Stratified Landscape”), a centralised Geospatial Database capable of ensuring reliable data archiving, real-time analytical processing, and collaborative information sharing among researchers and institutions engaged in cultural heritage management. The paper discusses key methodological challenges related to the heterogeneity of available documentation and the limitations of existing tools currently used for heritage research and protection in the Italian, and particularly Sicilian, context. At the same time, it highlights the potential of the proposed system in terms of data accessibility, verifiability, and query ability, as well as its ability to integrate and interrelate heterogeneous datasets within a multilayered, interdisciplinary framework for cultural landscape research. The pilot deployment focuses on a geographic area in southeastern Sicily, drawing upon documentation of the cultural landscape across four provinces—Agrigento, Catania, Ragusa, and Siracusa—and integrating archaeological, architectural, and environmental data to support risk assessment and heritage conservation strategies. Results appear to demonstrate ARPAS’s potential to improve the completeness of information, manage stratification across temporal layers, and support predictive and preventive analyses for cultural heritage at the landscape level.

1. Introduction

The landscape, conceived as a multilayered and intrinsically complex reality, is the result of processes that have continually redefined the balance between collective needs and limited resources [1] (art. 1). This stratification, far from being static, evolves over time, incorporating new social, economic, and environmental dynamics.

The concept of the landscape as palimpsest, first articulated by André Corboz [2], conceives the territory as a stratified text continuously rewritten through human intervention and cultural transformation. Each layer adds new meanings while preserving traces of the past, producing a dynamic interplay of continuity and change. Later adopted in archaeological theory by Stoddart and Zubrow [3] and further developed by Bradley [4] and Ingold [5], the metaphor transcends the purely physical dimension to encompass the social and symbolic processes through which landscapes are shaped, perceived, and reinterpreted over time. Within this broader theoretical trajectory, Bailey [6] reframes the notion of palimpsest not merely as a condition of material superimposition but as an analytical tool for understanding the cumulative, multi-temporal nature of the archaeological record—where erasure, transformation, and persistence coexist as part of a continuous temporal process. From a methodological standpoint, this conception underpins the analysis of stratified landscapes, encouraging integrated approaches that combine archaeological, environmental, and digital data to trace the diachronic relationships between human activity, spatial transformation, and material persistence. Such an interpretive framework allows for a deeper understanding of the landscape as both a cultural construct and a dynamic system of ongoing interaction between past and present.

Stratified landscape becomes “cultural heritage” when “people identify it, independently of ownership, as a reflection and expression of their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge and traditions [7] (art. 2). The concept of cultural heritage is closely connected to the need for transmission to the future and, consequently, for safeguarding risks of destruction. In a stratified landscape, cultural heritage takes many different forms and is subject to a variety of material threats, including seismic, hydrogeological and climatic risks.

Addressing and managing such complexity requires tools and methodologies that move beyond sectoral approaches, instead privileging an interdisciplinary perspective capable of integrating diverse forms of knowledge and expertise. Documentation, cataloguing, and analysis of the stratified landscape cannot, therefore, be restricted to a single perspective but must be articulated through a plurality of methods and tools able to capture the diversity of contexts and scales involved. From the perspective of risk and vulnerability, a global approach is essential—one that not only describes individual elements but also reorganises them within an overall framework that restores the relationships among natural, cultural, and social factors. Only in this way is it possible to address the challenges posed by managing the contemporary landscape, which demands more sophisticated tools than in the past, particularly those capable of engaging with the set of processes that have shaped and continue to transform it.

Conventional instruments developed to confront problems connected with natural and anthropic hazards, as well as the increasing threats of climate change, are often insufficient or confined within disciplinary domains that communicate only partially with one another. Safeguarding action has frequently been carried out by institutions that operate predominantly within archaeological research or the architectural restoration of monuments. This has resulted in a strong focus on individual architectural assets, sometimes enabling the definition of preventive measures at a detailed level, but often without consideration of the broader network of physical and cultural relationships within which emergencies arise—relationships that constitute both the foundation of their existential values and the potential sources of threat.

The difficulties of integration experienced in the past by the various disciplines involved in landscape conservation can now be overcome thanks to the new horizons opened by digital systems. This is one of the challenges embraced within the framework of the PNRR, CHANGES project [8]. Structured around nine thematic spokes, the CHANGES project was conceived with the aim of developing innovative procedures and tools for the understanding and enhancement of cultural heritage, ranging from digital archaeology to sustainable tourism, from risk management to the creation of creative ecosystems. Spoke 6 focuses on historical understanding, restoration, and the conservation of tangible cultural heritage. Within this spoke, a team of archaeologists and architects, supported by collaboration with “Advice”—a company specialising in the development of strategic software solutions—has worked on designing new digital tools for risk management that move beyond the traditional, monolithic, and undifferentiated approach to the landscape. The ARPAS geodatabase (risk analysis in the stratified landscape; in Italian, this is “Analisi del Rischio nel PAesaggio Stratificato”) was thus developed with the aim of documenting, analysing, and managing risk within a system capable of accounting for the diachronic dimension of the stratified landscape. To best test the potential of this approach, the focus was placed on the earliest phases of cultural heritage—those dating back to antiquity and documented by archaeological evidence.

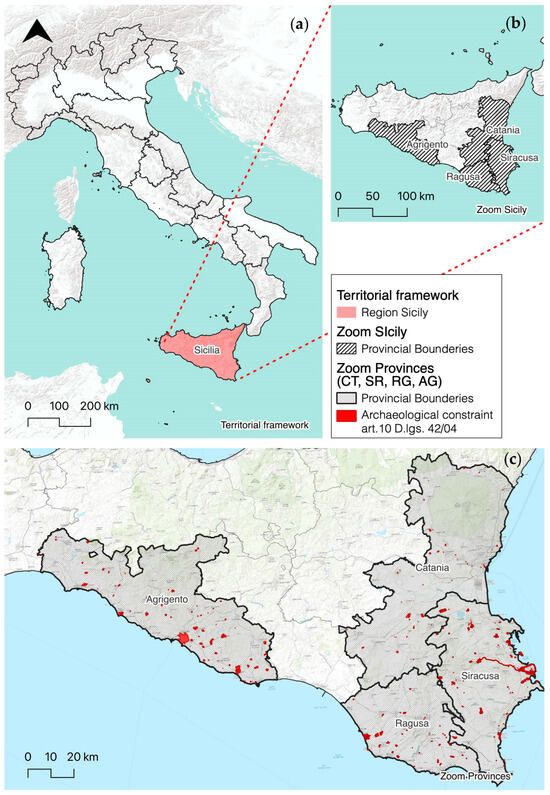

Four provinces in southeastern Sicily (Agrigento, Catania, Ragusa, and Siracusa) were selected for the development of this experimental project as they offered several favourable conditions (Figure 1). First, these areas are characterised by landscapes extraordinarily rich in cultural layers, spanning from prehistory and the fifth millennium BCE to the present day without interruption. Second, they are territories well known to the team’s archaeologists, who have been conducting research there for many years. Finally, the cultural heritage of these areas has been only partially documented and through highly heterogeneous, sector-specific tools. This situation poses significant challenges for data communication and management and exemplifies one of the major limitations of traditional approaches to the stratified landscape.

Figure 1.

(a) Territorial framework at national scale, Sicily in red; (b) Enlarged view of Sicily. Highlighted the four provinces under investigation: Agrigento, Catania, Siracusa, and Ragusa; (c) Four provinces under investigation in grey and Archaeological sites constraints (art. 10 D.lgs. 42/2004) in red.

The design of the new approach developed within ARPAS required a preliminary reflection on the principles, methods, and tools underlying the processes of understanding the stratified landscape, as well as on the traditional systems for managing risk in cultural heritage. This reflection is presented in the first part of the paper. The second part provides a detailed description of the materials and methods employed in the new project, while the third part discusses the procedures that led to the development of ARPAS, along with its potential and limitations. The guiding idea behind the entire work is that risk can be managed more effectively and consciously through operators and infrastructures capable of recognising and addressing the stratified nature of the landscape and the chronological and historical identity of the tangible manifestations of cultural heritage.

2. A History of Useful Concepts and Tools in Landscape Planning and Archaeological Research

This section examines the evolution of key concepts and operational tools that have shaped both landscape planning and archaeological research, highlighting the progressive convergence of their approaches to the notions of risk and stratification. Within the broader field of cultural heritage studies, these two perspectives have developed distinct yet complementary methodologies: landscape planning focuses on the spatial delineation of cultural heritage and the mitigation of associated threats to cultural and environmental values, while archaeology investigates the temporal and material stratification that reveals the historical depth of places.

By retracing the development of these conceptual and methodological frameworks—from the European Landscape Convention to contemporary data-driven tools—this section underscores how the growing integration between planning and archaeological approaches fosters a more comprehensive, relational, and sustainable understanding of cultural landscapes. This convergence forms the conceptual foundation for the development of ARPAS.

2.1. The Perspective of Landscape Planning: Focus on Risk

2.1.1. From the European Landscape Convention to Landscape and Territorial Planning

Article 1 of the European Landscape Convention (Firenze, 20 October 2000) in paragraph 1 declares the cultural framework promoted by the Member States of the Council of Europe, defining landscape as part of the territory, understood in its perceptual value by the population and whose character derives from “the action of natural and/or human factors and their interrelationships”. The scope of the Convention goes beyond the mere identification of landscapes of exceptional quality and uniqueness, also including every-day and degraded landscapes (Article 2), as evoked by Boscolo [9] in his representation of landscapes by “layers”, subsequently taken up in the Cultural Heritage Code [10].

The first “layer” of the codified discipline concerns the state’s protection of elements representing national identity and cultural values, encompassing landscape assets such as natural beauties, geological rarities, sites of historical or traditional value, and other legally or plan-protected areas with distinctive landscape features.

The second “layer” concerns territories with landscape value managed through the landscape plan (Art. 135), rather than specific protected assets.

In order to manage and safeguard the identity values of the first and second “layers”, it is desirable to define strategies that incorporate, together with safeguarding, protection and enhancement, the dimensions of prevention, adaptation and mitigation of the growing risks arising from climate change and anthropogenic pressure on landscape assets. These risks threaten the very “value of existence” [9] of the landscape for future generations to enjoy.

2.1.2. Methods and Tools for Safeguarding Cultural Heritage from Risk: Risk Map and Landscape Planning

The progressive depletion of natural and cultural resources, attributable to anthropogenic processes, soil exploitation, and exposure to multiple hazards, has resulted in significant landscape degradation. Landscape restoration and the enhancement or creation of novel landscapes constitute core functions of landscape planning, as outlined by the European Landscape Convention. Incorporating risk assessment within the analytical and interpretative framework of landscape planning is essential to safeguard resources for future generations, particularly in contexts characterised by territorial marginality, depopulation, and demographic ageing.

In the Italian context, a principal instrument for cultural heritage management is the Risk Map (“Carta del Rischio”), conceived by Giovanni Urbani (1925–1994), which facilitates the cataloguing of cultural assets at risk through a centralised database. The operationalization of this tool was formalised through Law 84/1990, containing the “Comprehensive plan for the inventory, cataloguing and processing of the Risk Map of cultural heritage, …” [11]. The Risk Map responds to the need to develop a centrally managed database of cultural, architectural, archaeological and historical-artistic heritage, with the aim of identifying cultural heritage at risk, based on an integrated approach between heritage and territory, from which the interpretative categories for risk analysis and planning of preventive measures are derived.

For the purposes of protection, understanding what to protect, how many assets there are, their state of conservation and the risk factors involved is the first step in risk prevention operations: cataloguing—carried out by the ‘Ministry with the cooperation of the regions and other local authorities’ [9]—by sorting the assets into homogeneous categories based on their characteristics and the specific protection issues of each, would have enabled conservation planning [12].

Nonetheless, the Risk Map exhibits conceptual and methodological limitations: it remains anchored to a 20th-century paradigm, primarily encompassing legally recognised assets, and often considers individual assets in isolation from their broader territorial and systemic context. Such an approach constrains the implementation of integrated, multi-scalar strategies for heritage conservation and risk mitigation.

The structure of the Risk Map classifies archaeological assets using the designation MA (Archaeological Monument), distinguishing between monuments of declared cultural interest and monuments of unverified interest. Unlike other architectural assets, such as churches located within historic urban areas, archaeological monuments are not surveyed according to area criteria but are represented individually. This approach also differs from the cartographic representation method used for areas subject to restrictions pursuant to Article 10 of Legislative Decree 42/2004 [9].

An innovative system for monitoring, analysing, and safeguarding historical assets has recently been implemented in France. Through the application of artificial intelligence, Heritage Watch AI [13] has been developed as an advanced framework for cultural heritage protection. This innovative tool was designed with the objective of monitoring and preserving historical sites, artworks, and monuments by employing cutting-edge technologies, including machine learning, satellite image analysis, and next-generation sensors. The initiative results from a collaboration between UNESCO, French public institutions, and leading technology companies. Natural deterioration and climate change represent some of the major challenges that the system aims to address through a preventive and automated approach.

Asprogerakas et al. [14] codified protection policies and developed a typology of interventions for major archaeological sites in Greece. Their objective was to define a spatial planning framework capable of addressing the challenges posed by climate change. This includes promoting an integrated design approach to cultural heritage protection—moving beyond traditional conservation practices—and fostering stronger connections between cultural heritage and the natural environment. The concept of cultural heritage is redefined in dynamic and spatial terms, supporting both climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, as well as preparedness for emergency response.

Spiridon et al. [15] explored the use of Geographic Information System (GIS) tools to examine aspects related to at-risk cultural heritage in Iași, Romania. They developed a spatial database of ecclesiastical heritage, integrating additional attributes such as the construction period and the year of the most recent restoration intervention for each vector record. These attributes can be updated in real time, enhancing the accuracy and responsiveness of cultural asset monitoring.

Valagussa et al. [16] developed a methodology that adopts a quantitative and reproducible heuristic approach to risk assessment through the UNESCO Risk Index (URI). This index integrates hazard intensity with a potential damage vector, estimating the expected impact according to the type of heritage site, its spatial configuration (underground or above ground), and the hazard type. Applied to both entire World Heritage Sites and their components, the method identifies areas with differing risk levels.

Some authors [17] focus on the reasons behind the inapplicability of certain conservation and maintenance processes for cultural heritage in local contexts, due to automatic processes of social exclusion that inhibit community participation and support. Insights derived from anthropological research promote a view of cultural heritage as a living and continuously evolving entity, deeply embedded within social practices.

International contributions highlight the need to integrate diverse tools and analytical methods—such as GIS and machine learning—for a comprehensive assessment of cultural heritage at risk. These integrated approaches would allow the development of dynamic, easily updatable databases that can reflect new mappings related to multiple dimensions: the landscape dimension—with the integration of cultural assets within broader or altered landscapes; the archaeological dimension—with new stratigraphic layers; the architectural dimension—in light of new restoration interventions; and, finally, the regulatory dimension, which is subject to change over time.

2.2. The Perspective of Archaeologists: Focus on Stratification

2.2.1. Stratified Landscapes: Documentation, Methods, and Tools

Building on the theoretical premise outlined in the Introduction, the documentation of stratified landscapes relies on integrated methods that connect field archaeology, geomatics, and archival sources to reconstruct long-term territorial dynamics [18,19]. Within this framework, the landscape—understood as a multilayered and diachronic palimpsest—constitutes the analytical space in which landscape and stratigraphic archaeology converge; just as stratigraphic excavation reconstructs superimposed sequences of human activity, landscape analysis considers successive and overlapping transformations that have shaped the territory over time. This perspective requires a global, multiscale approach capable of linking individual archaeological features to broader regional frameworks [20,21].

Geospatial technologies have significantly enhanced our ability to document and analyse archaeological landscapes. While stratigraphic excavation and systematic field survey remain foundational [22] the integration of GPS, drones, photogrammetry, and LiDAR has increased the precision, efficiency, and scale of data acquisition [23,24,25]. UAV-mounted LiDAR has proven especially valuable in vegetated or morphologically complex areas: recent studies have demonstrated how high-density LiDAR surveys enable the identification of micro-morphological archaeological features in Mediterranean hilly environments characterised by dense forest cover and reduced visibility [26].

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) provide the core infrastructure for organising, analysing, and visualising spatial information, allowing multiple thematic layers and data types to be integrated within a single environment [27]. The creation of structured geodatabases has therefore become essential for correlating heterogeneous archaeological, environmental, and documentary sources, enabling spatial queries, diachronic comparisons, and predictive models [28]. Large-scale geospatial infrastructures—such as regional or national geodatabases—play a crucial role in coordinating documentation and ensuring the long-term monitoring of archaeological landscapes [29].

2.2.2. Technical Validation and Limitations

Although advanced digital tools offer significant benefits, it is essential to address their technical parameters and limitations. GPS positioning, under optimal conditions (for instance with RTK acquisition), can achieve centimetric accuracy; however, tree canopy, rugged topography, and satellite signal interference can reduce precision, introducing variations on the order of decimetres or more [30,31]. Similarly, LiDAR performance depends on point-cloud density, sensor configuration, flight altitude, and terrain complexity. Even when high accuracy is achieved, dense vegetation, erosion, and complex morphology can hinder the detection of subtle archaeological micro-reliefs [26].

Automated workflows for processing LiDAR and photogrammetric data—including those based on machine learning for morphological feature extraction—introduce additional methodological considerations. These approaches can enhance interpretative efficiency but may also introduce classification bias or false positives. It is therefore essential to document processing steps transparently, to assess accuracy rigorously, and to conduct field verification wherever appropriate.

2.2.3. Ethical Aspects and Data Protection

The growing diffusion of open-access platforms and digital repositories has transformed archaeological practice, expanding access to data, and fostering collaborative research. However, the publication of high-precision spatial information can expose vulnerable sites to risks of looting, unauthorised visits, or damage. Open dissemination does not automatically equate ethical practice and must be accompanied by appropriate control and responsibility measures [32]. Recent debate in digital archaeology highlights the need to establish solid ethical frameworks for data sharing and management; online archaeology often lacks consistent guidelines, forcing researchers to make ethical decisions on a case-by-case basis [33]. Moreover, even within well-structured open-access contexts, challenges persist concerning the responsible reuse and contextualisation of data [34].

Within this framework, archaeological geodatabases should adopt strategies that balance research transparency with site protection. Good practices include the generalisation of sensitive coordinates, the adoption of tiered access systems, and the accurate documentation of provenance, usage rights, and metadata structures [35].

2.2.4. Risk in Archaeology and Tools for the Safeguard of Stratified Landscapes

The issue of risk in archaeology forms part of the broader theme of cultural heritage protection, long debated in Italy. In the Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code [9], Article 29, paragraphs 1 and 2, specifies that conservation of cultural heritage, of which archaeological assets represent one of the most fragile components, must be ensured through coherent, coordinated, and planned activities of study, prevention, maintenance, and restoration. Prevention is defined as “the set of activities suitable to limit the risk situations related to the cultural asset within its context” [36]. Risk management, whether associated with natural or anthropic activities and whether predictable or not, applies to the same regulatory tools used in the management of cultural heritage, including planning and management instruments and the Risk Map.

In recent years, alongside the development of preventive archaeology, the concept of archaeological risk has acquired a different meaning, leading to regulatory adjustments. In a predictive perspective, archaeological risk represents the probability of encountering archaeological evidence during construction or infrastructural projects. The degree of archaeological risk in each area is quantified based on the likelihood that archaeological stratification is preserved there, and therefore vulnerable to planned interventions [37].

A significant shift can be observed in the definition of risk in archaeology. Whereas earlier policies focused on identified and catalogued archaeological assets formally recognised as cultural heritage, more recent developments target unidentified or uncatalogued stratifications. In this view, attention shifts from visible material evidence to the archaeological potential of an area. Archaeological potential, meaning the possibility that an area preserves structures or stratigraphic layers, is an intrinsic characteristic that does not vary according to the type of project or planned work. The assessment of archaeological potential underpins current protection strategies and preventive approaches.

The assumption is that the most effective strategy for ensuring the transmission of heritage to future generations lies in planning through strategies that predict archaeological potential, thereby quantifying the associated risk and limiting excavation to cases of actual necessity [38].

The crucial for assessing the archaeological potential of an area is the knowledge and evaluation of the complete set of archaeological and topographical documentation. Key elements include the territorial context and the historical-archaeological characteristics of the area, represented by ancient and modern anthropogenic transformations of the landscape and associated artefacts. Investigation of environmental and geomorphological conditions that shaped settlement choices, combined with diverse information from historical-archaeological sources (non-material data inferred from topography, material evidence of ancient nuclei, architectural and testimonial elements, unpublished reports, or surveys and excavations), supports the identification and characterisation of possible ancient occupations or settlements.

From this perspective, preventive assessment of archaeological potential and risk, together with knowledge of the landscape in its historical stratification, are inseparable concepts in developing strategies for archaeological landscape protection.

The predictive approach forms the basis of regulatory instruments currently in use, foremost among them the Verification of Archaeological Interest (VPIA) [39]. This is implemented through the National Archaeology Geoportal (GNA), designed and managed by the Central Institute for Archaeology (ICA) [40]. The GNA is the first national-level tool for documenting and sharing the results of preventive archaeological investigations in open access. The project aims to “make available to the Ministry of Culture (MiC) and other public administrations, territorial authorities, professionals, companies, and citizens, a dynamic archaeological map of Italy” [41].

The GNA represents a significant resource for updating data resulting from new investigations across the country. However, the management of archaeological data from previous research remains the responsibility of regional administrations or individual research institutions.

3. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodological and documentary foundations of the ARPAS project, focusing on the integration of legacy and newly acquired data from southeastern Sicily. It combines information from provincial Landscape Plans and recent archaeological research to construct a coherent, multi-layered vision of the region’s cultural landscape. By merging heterogeneous datasets, ARPAS establishes the basis for an advanced, risk-oriented system of analysis and management of historical and environmental stratifications.

3.1. Materials: Legacy and Newly Acquired Data from the Study Areas

3.1.1. Provincial Landscape Plans (Sicilian Region Geoportal S.I.T.R.—Open Access)

Landscape Plans are the main tool for implementing policies for the protection and enhancement of the landscape, in accordance with the provisions of the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape [9] and Articles 135 et seq.

The Sicilian legal system, as expressed in the Guidelines of the Regional Landscape Plan of Sicily [42], has promoted the adoption of landscape planning organised by homogeneous territorial areas. This approach, consistent with the subsequent provisions contained in the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape, aims to ensure a differentiated and contextualised interpretation of the regional territory, enhancing its environmental, historical and cultural specificities. The subdivision into areas allows for the calibration of protection and management strategies according to the specific characteristics of local contexts, promoting a systemic and integrated vision of the landscape.

The Plans, drawn up by the Superintendence for Cultural and Environmental Heritage in collaboration with local authorities and other institutional bodies, are not limited to an inventory of landscape assets protected ex lege, but introduce a systemic interpretation of the territory, enhancing both tangible and intangible elements of the landscape, even where these lack formal recognition.

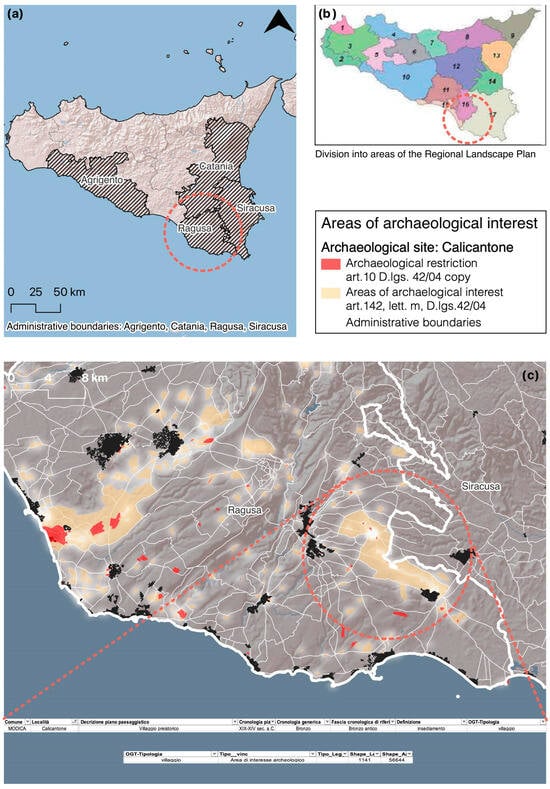

For the purposes of this study, the landscape plans of the provinces of Catania, Syracuse, Ragusa, and Agrigento were examined. In particular, the landscape plan for the province of Catania covers areas 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16 and 17; that of Syracuse covers areas 16 and 17; that of Ragusa covers areas 15, 16 and 17; and finally, that of Agrigento covers areas 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 11 and 15 (see Figure 2b). More than one area straddles several provinces, providing an opportunity to develop synergistic and convergent planning that goes beyond the logic of administrative boundaries, which is often disappointed by the plans adopted (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Administrative boundaries of the four provinces under investigation: Agrigento, Catania, Siracusa, and Ragusa; (b) division into areas of the Regional Landscape Plan of Sicily. The dotted and circular frame is the focus zoom area in c); (c) detail of archaeological site of Calicantone, with Database detail.

Specifically, the study focuses on the historical framework, with reference to archaeology, as highlighted in Article 3 of the settlement subsystem [42] (Title I, D.A. No. 6080/1999). The division of the territory into areas presents some structural criticalities. Since Landscape Plans are drawn up on a provincial basis, it may happen that the same landscape area is divided between two or more provinces. This territorial fragmentation, aggravated by the frequent lack of effective communication and coordination between the provincial administrations involved, can lead to significant difficulties in the coherent and integrated drafting of the planning tool, compromising its effectiveness in terms of landscape protection and enhancement.

3.1.2. Data from Recent Archaeological Research (Unict—CHANGES Spoke 6): Agrigento, Calaforno, Calicantone, and Pantalica

Within the ARPAS framework, data derived from recent archaeological investigations carried out under the CHANGES project have been integrated with the information from regional landscape plans, creating a unified and dynamic foundation for interpreting the cultural landscape of southeastern Sicily. The integration of these datasets allows for a multi-temporal and multi-scalar reading of historical processes, revealing the deep connections between settlement, environment, and social transformation.

3.1.3. Agrigento

In Agrigento, research within the Archaeological and Landscape Park of the Valley of the Temples has focused on the monumental core of ancient Akragas, particularly the area of the theatre [43]. The combined use of excavation, architectural study, and digital documentation has made it possible to reconstruct the urban evolution of the site [44]. The results reveal a complex and multilayered urban landscape, shaped by centuries of transformations—from the Archaic and Classical phases to Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages—when older structures were dismantled, reused, or incorporated into new architectural configurations.

3.1.4. Pantalica

The site of Pantalica (Siracusa) is emblematic of the notion of a “stratified landscape.” It stands on a limestone plateau set between the valleys of the Anapo and Calcinara rivers, characterised by extensive rock-cut necropoleis distributed along its slopes. Occupied between the 13th and 8th centuries BC, the site comprises more than 5000 chamber tombs from the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages. Among its architectural remains, the so-called Anaktoron represents a megalithic structure possibly associated with elite or ceremonial functions. Later phases attest to Byzantine reoccupation, with evidence of rock-cut dwellings and chapels [45]. The collaboration between the Archaeological Park of Siracusa and the University of Catania has enabled a new reading of the site through the combination of archival research, the re-examination of materials from Luigi Bernabò Brea’s 1960s excavations, and extensive field surveys covering nearly 20 hectares around the Anaktoron plateau. This work has documented over 150 previously unknown hypogea, several standing structures, and hundreds of grinding stones belonging to different chronological phases [46]. The emerging picture is that of a dynamic and long-lived settlement, where material evidence of continuity and reuse coexists with signs of profound change.

3.1.5. Calicantone

Located in the Cava d’Ispica valley on the Hyblaean plateau, Calicantone represents another key context for understanding Bronze Age life in southeastern Sicily. Archaeological investigations carried out between 2012 and 2015 revealed a necropolis of about ninety rock-cut tombs and a large hut structure notable for its dimensions and the richness of its finds [47]. Within the CHANGES project, the organisation and digitization of these datasets have allowed new analytical connections to be drawn between settlement, funerary, and environmental data [48,49,50]. The results highlight the valley’s role in seasonal pastoralism and the adaptive use of natural resources, revealing a subtle balance between human presence and the geomorphological characteristics of the territory.

3.1.6. Calaforno and Canicarao

In the western Hyblaean district, the areas of Calaforno and Canicarao illustrate the long-term shaping of the landscape through resource exploitation and ritual activity. Here, survey and excavation have defined the broader environmental framework of two major prehistoric complexes: the Calaforno Hypogeum—a monumental collective burial partly hypogeal and partly megalithic (late 3rd millennium BCE) [51]—and the flint-extraction sites of Monte Tabuto and Contrada Coste (early 2nd millennium BCE) [52]. The integration of these datasets within ARPAS has produced a detailed geospatial representation of the area, documenting a palimpsest of human activity extending from prehistory to the modern era, and underscoring the potential of data-driven approaches to reconstruct and interpret deep-time cultural landscapes.

3.2. Towards a New Tool for Integrated Management

The experiment conducted within the CHANGES project aimed to enhance the existing tool by making it capable of documenting and managing landscape stratifications. To this end, ARPAS, was developed by ADVICE as a centralised and modular geodatabase based on PostgreSQL and Docker technologies, ensuring scalability, portability, and operational autonomy across different cloud environments [53].

The ARPAS Geodatabase overcomes the limitations of traditional flat-file systems by integrating geospatial and contextual data within a coherent and normalised model designed to manage heterogeneous inputs, including sensor-derived datasets. It is capable of handling various categories of sources and is specifically designed to interrelate 3D models and BIM of archaeological sites, fostering a comprehensive understanding of spatial and temporal relationships. This architecture supports the association of descriptive metadata, chronological tracking of interventions, and the linkage of documentation to specific spatial entities, thereby enabling long-term, data-driven cultural heritage research.

Developed to promote interdisciplinary landscape analysis, ARPAS strengthens the integration between risk-related and cultural heritage data—addressing key issues such as data completeness, the management of historical stratification, and advanced threat prediction, which go beyond the capabilities of conventional tools like the Risk Map. Data accessibility and collaborative analysis are facilitated through a WebGIS platform built on open-source technologies (QGIS Server and Lizmap), enabling interactive visualisation and multi-user exploration of spatial information.

The ARPAS Geodatabase was designed to promote an integrated approach to landscape research, enabling data related to different categories of risk to interact more effectively with information concerning cultural heritage than is currently possible in the Risk Map. Its effectiveness can be assessed along three main axes:

- Completeness of information and accuracy of localization,

- Management of stratification,

- Threat prediction.

With respect to the first axis, the Risk Map remains incomplete in relation to cultural heritage already catalogued by competent authorities. For example, regional administrations (or provincial administrations in Sicily) have conducted detailed work to identify cultural landscapes; however, in Southeastern Sicily, data from landscape plans were not effectively integrated into the Risk Map, often resulting in inconsistencies and inaccuracies in geographic localization [54]. Furthermore, the provincial framework prevented data from being communicated beyond administrative boundaries.

The management of stratification constitutes the second axis for improvement. In this regard, the ARPAS Geodatabase, provides chronological information on catalogued assets, allowing queries by occupational phases. This functionality is essential for reconstructing the landscape as it evolved over time and for defining its historical and cultural characteristics.

The third axis is threat prediction, understood in broader terms than in the past. It is not only a matter of identifying specific risks in relation to isolated assets, but also of evaluating the minimal territorial unit in which a cultural asset and its landscape relationships can be interpreted, as well as the impact of large-scale or long-term processes capable of altering the identifying features of a given context.

4. Discussion

This section illustrates the process through which ARPAS transformed heterogeneous archaeological and landscape datasets into a coherent, standardised geodatabase. It outlines the steps taken to reconcile inconsistencies in documentation from Sicilian provinces, integrate data from legacy sources and new research, and adopt ICCD standards for typology and chronology. By organising information according to hierarchical temporal and thematic criteria, ARPAS enables dynamic analysis of landscape stratification and risk across different historical phases.

4.1. From Heterogeneous Sources to Structured Data: Standardisation Process in ARPAS

The development of ARPAS required addressing significant inconsistencies in the documentation and management of archaeological and landscape data across the Sicilian provinces of Agrigento, Catania, Ragusa, and Siracusa. Data were acquired from the Landscape Plans developed and published by the local Superintendents. Although based on general guidelines from the central administration, each provincial plan presents site information differently, resulting in datasets with inconsistencies in field definitions and organisation. When digitised and published in the Sicilian Regional Geoportal (S.I.T.R.), these discrepancies persisted [55].

From the geoportal, the corresponding shapefiles were extracted and reprocessed for integration into the ARPAS geodatabase (Figure 3). Based on the number of fields, the documentation could be grouped into three categories: (i) a minimal set, with a single field containing only the municipality and the catalogue number of the sheet (Agrigento); (ii) an intermediate set, separating the municipality and adding site name and legal references to protection (Siracusa); (iii) a more detailed set, including fields for typology and chronology (Catania and Ragusa). Even the more complete databases presented internal inconsistencies, as fields were compiled at different times and by different authors without standardised criteria.

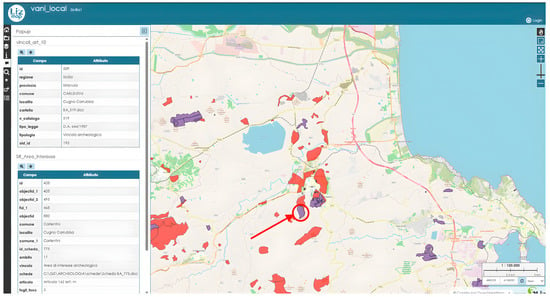

Figure 3.

Example of the visualisation of archaeological constraints (archaeological sites constraints (art. 10 D.lgs. 42/2004; areas of archaeological interest srt. 142, lett. m, D.lgs 42/04) in the Carlentini area (Sicily) using the Lizmap interface. Data from the Arpas Geodatabase, provided by Advice developers.

In short, the initial documentation presented two main problems: incompleteness, since much information remained only in paper sheets and was not fully incorporated into the open-access geoportal, and heterogeneity, due to the variety of cataloguing strategies adopted over time.

During reprocessing for ARPAS, it was first necessary to define standardisation criteria at two levels. The first concerned the fields assigned to each record. Based on the geoportal data, the following fields were defined: Province, Municipality, Locality, Description from the Landscape Plan, Chronology from the Landscape Plan, Type of Protection, and Legislative References. Missing information was supplemented by manually transferring data from the original sheets.

Data from the Landscape Plans were further enriched with information from CHANGES Spoke 6 research in the Iblean area (Pantalica, Calaforno, Canicarao, Calicantone) and in the urban sector of ancient Akragas.

The next step concerned the standardisation of typology and chronology fields. These are essential for uniform and coherent management of heritage information. The most effective national reference for standardisation is provided by ICCD tools [56,57]. These were adopted with minimal adjustments, in order to guarantee both completeness of information and effective management of landscape stratification.

4.2. Completeness of Information

The completeness of information is evaluated with respect to the original datasets from the Landscape Plans and assesses both the correctness of recorded data—including site denomination, chronology, and geographic coordinates—and the presence or absence of missing attributes. The benchmark for this evaluation is provided by the existing bibliographic and scientific documentation, which serves as an external reference for validation.

Building on this process of data validation, particular attention was devoted to the harmonisation of typological and chronological information. Following the ICCD model, a two-level structure for typology and chronology was adopted, comprising a general and a specific level. This hierarchical system facilitates searches at multiple scales and significantly enhances query potential. To prevent information loss, the original content from the Landscape Plan sheets was retained in the fields “Description from the Landscape Plan” and “Chronology from the Landscape Plan.” Each of these was complemented by two additional fields compiled using standardised terminological categories. For typology, sites were described in a general field (OGTD—Definition) and a specific one (OGTT—Typological Specification).

The adoption of standardised terminology for typological classification presented several challenges. The documentation often resists precise categorization due to varying preservation conditions, the absence of targeted investigations, and the intrinsic complexity of cultural evidence. Simplification was therefore necessary, particularly when a classification had to encompass extensive chronological ranges, as in this case.

The ICCD system effectively addresses these challenges through its two-level categorization and extensive controlled vocabulary. For typology, it includes 26 general categories (OGTD) and 226 specific ones (OGTT), with the option of refining broader entries using more detailed terms. For instance, the OGTT category “place of worship” can be specified as chapel, church, iseo, mithraeum, oratory, pieve, sabazeum, serapeum, synagogue, temple, or small temple.

Thanks to this flexibility, the ICCD classification system proved well suited to the structure of the ARPAS geodatabase, ensuring both consistency and adaptability in the management of archaeological information.

4.3. Management of Stratification

The management of stratification in cultural heritage is closely linked to the ability to make selective choices within the documentation, allowing the geodatabase to display evidence of occupation according to different chronological phases. For this purpose, the two-level hierarchical structure proposed by ICCD was adopted, expanding the possibilities of selection within the dataset. Two fields were introduced: a higher-level “Generic Chronology” and a more specific “Reference Chronological Range.”

The use of ICCD terminology for chronology, however, posed challenges. The ICCD system is complex, designed to cover both geological and archaeological contexts, and incorporates both relative chronology (period-based) and absolute chronology (solar years). While this approach is appropriate for managing the highly heterogeneous heritage of the entire Italian peninsula, the ARPAS geodatabase, with its regional focus, required a more streamlined system. For this reason, two categories were adopted: macro-periods and micro-periods, corresponding to recurring features of material culture and their approximate chronological ranges (Table 1).

Table 1.

Macro- and micro-periods with chronological ranges.

Even within these sequences, divisions are not unambiguous but the result of negotiation between the geo-historical context, the available archaeological documentation, and historiographical debate. As with all negotiated classifications, they involve compromises and partial solutions. In ARPAS, there is a relative emphasis on prehistory and protohistory, with more subdivisions than for later antiquity, and similarly a greater articulation for ancient times than for post-ancient periods. The first reflects the research interests of some of the authors, while the second reflects the nature of the available documentation, which is richer for ancient and medieval contexts. Nevertheless, this subdivision across the entire chronological span enhances interpretative opportunities by highlighting long-term occupation trends that influenced landscape formation.

The adopted sequences also reflect the historical particularities of Sicily [29]. For instance, only the Upper Palaeolithic is included, since no secure evidence exists for the Lower or Middle Palaeolithic. The Copper Age is subdivided into four phases, following Bernabò Brea’s model, later debated but confirmed by recent excavations at Calaforno [58]. The initial phase of Greek presence in Sicily, corresponding to the late 8th and 7th centuries BCE, was grouped with the last phase of protohistory (“Iron II”) rather than with the Greek period, both for simplification and because Greek cultural specificity is less evident than indigenous elements in this phase. Similarly, local cultural expressions from the 6th century BCE onwards were aligned with the Archaic and Classical periods of Greek history.

The Hellenistic period in Sicily ended earlier than in the rest of the Mediterranean, following the First Punic War and the establishment of Roman control. Other adjustments concern the transition from antiquity to the Middle Ages. The Justinian conquest of 535, which brought Sicily into the Byzantine sphere, represents a major chronological marker. Another significant but less archaeologically visible event in southeastern Sicily is the Arab presence, conventionally dated between their arrival in 827 and the Norman reconquest beginning in 1061. The Norman period was taken at the start of the Late Middle Ages, since it introduced dynamics comparable to those in Europe at the turn of the first millennium.

These chronological frameworks function as interpretative tools rather than rigid periodization. To mitigate their limitations, chronological ranges were assigned even when occupational phases only partially overlapped them. More detailed information is preserved in the “Description from the Landscape Plan” and “Chronology from the Landscape Plan” fields, retrievable when a record is selected. In ARPAS, each record’s occupational phases also include notes on temporal discontinuities, which are particularly significant for smaller sites—by far many entries—often characterised by alternating phases of abandonment and reuse. Such discontinuities provide valuable insights into community strategies and the human contribution to landscape transformation, sometimes more clearly than in large urban contexts where continuous occupation tends to obscure these dynamics.

The definition of macro- and micro-periods within ARPAS is not merely descriptive but responds to analytical needs related to risk assessment. Each chronological range corresponds to distinct patterns of land use, settlement density, and resource exploitation, which directly influence the vulnerability of cultural assets. By structuring the dataset according to fine-grained temporal segments, it becomes possible to model diachronic variations in exposure and susceptibility—for instance, by correlating phases of intense anthropic activity with environmental instability or by identifying long-term trends in site reuse and abandonment. This temporal articulation enhances the interpretative potential of ARPAS, allowing risk evaluation to consider not only spatial but also historical dimensions of landscape transformation.

5. Results

This section presents a comparative evaluation of the ARPAS geodatabase against existing national heritage datasets, focusing on accessibility, completeness, and interoperability. By addressing the inconsistencies of sources such as the Landscape Plans, GNA, ICCD, and the Risk Map, ARPAS demonstrates how standardised data structures can enhance research, planning, and risk assessment. The discussion highlights ARPAS’s broader spatial coverage, methodological rigour, and potential as a model for integrated cultural heritage management.

5.1. Assessing Data Accessibility and Completeness: A Comparative Analysis of ARPAS and Existing Heritage Databases

The normalisation and implementation of a unified data platform offer significant advantages in terms of data accessibility and reusability. Although the source data for our database—namely, the Provincial Landscape Plans—are publicly available online in shapefile format and can be used within GIS environments [55], the heterogeneity of attribute fields and the lack of normalisation prevent cross-provincial queries, allowing searches only within individual provincial datasets. This limitation represents a major obstacle not only for research but also, and above all, for effective territorial planning.

To address these challenges, the ARPAS geodatabase adopts a structured approach to the management of archaeological information. Archaeological data within ARPAS are organised according to the subdivision established in the Regional Landscape Plans (“Piani Paesaggistici Regionali”), distinguishing between areas subject to archaeological protection under Article 10 and those under Article 142, letter m, of the Italian Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code [9] (D.Lgs. 42/2004) (Table 2). This structure allows for a more nuanced spatial representation of protected zones and enhances the integration of archaeological and landscape information within the same analytical framework.

Table 2.

Comparative overview of archaeological data coverage across ARPAS, GNA, ICCD, and the Risk Map.

The pilot version of ARPAS currently manages a total of 2480 records, comprising 815 areas under formal archaeological protection and 1665 areas of archaeological interest. This organisation supports multi-scalar analyses and facilitates cross-provincial comparisons within a standardised and interoperable system. Such structuring represents a substantial step toward the normalisation of datasets and the development of shared data standards for cultural heritage planning.

The normalisation of datasets through the definition of standardised and univocal fields thus constitutes a major step forward for strategic and integrated territorial planning. However, a review of freely accessible online databases, such as GNA and ICCD, reveals considerable shortcomings in this regard. Focusing on the provinces included in the ARPAS pilot project (Agrigento, Catania, Ragusa, and Siracusa), it becomes evident that these datasets are affected by substantial gaps in both completeness and accessibility (see Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Assessment of Data Completeness Across Heritage Databases: ARPAS, ICCD, and Risk Map (Provincial Comparison).

The National Archaeological Geoportal (GNA) [41] presents several positive aspects, particularly its articulation of archaeological entities into points, lines, and polygons, which allows for differentiated spatial representation based on the geometry and scale of archaeological evidence. In practical terms, points are used when an archaeological site or feature has a precise location and does not require the representation of areal extension; lines are employed when the entity is linear in nature (e.g., ancient routes, walls, or canals); and polygons or multipolygons are applied when the entity occupies a surface area or includes multiple spatially aggregated components (e.g., excavation areas, settlements, or stratified landscapes).

However, the system primarily focuses on data derived from recent research activities and does not systematically include legacy data, which represent a significant portion of the archaeological record collected over the past decades. As discussed in Section 2.2.2, this limitation affects the overall completeness and diachronic depth of the dataset, reducing its potential for comprehensive territorial and historical analysis. Moreover, the GNA still presents significant internal gaps, particularly the absence of archaeological data for the provinces of Ragusa and Siracusa, which further limits its representativeness and usability in regional-scale comparative analyses.

The ICCD database concerning archaeological assets is accessible through the GNA portal via an interactive map [41,46], allowing for the rapid visualisation of sites catalogued by the Central Institute for Cataloguing and Documentation (ICCD), which oversees the management and standardisation of Italy’s national cultural heritage documentation system. However, several critical issues have been identified. At present, it has not been possible to obtain a precise and verified figure for the total number of archaeological assets in the provinces of Ragusa and Siracusa from the publicly indexed datasets of the ICCD or the GNA. For the provinces of Catania and Agrigento, however, indicative figures were retrieved: 94 sites were recorded for Catania and 102 for Agrigento. When compared with the data currently included in the ARPAS system—which records 552 sites for Catania and 644 for Agrigento—this corresponds to an approximate coverage of 17% and 16%, respectively. These figures highlight the considerable disparity between the datasets and underline the need for greater integration and normalisation of existing archaeological information sources.

A comparative analysis of the Risk Map dataset and ARPAS data further reveals significant discrepancies in the number of recorded archaeological assets across the study areas. Specifically, the Risk Map documents only 21.6% of the sites included in ARPAS for Agrigento, 13.8% for Ragusa, 17.8% for Catania, and 26.3% for Siracusa. These figures clearly indicate the greater completeness and spatial coverage achieved by the ARPAS geodatabase, particularly in areas where the Risk Map remains partial or outdated.

The comparative analysis of the Risk Map dataset [59] also revealed a series of structural and methodological weaknesses that significantly limit its potential for research and planning purposes. Although the Risk Map represents one of the most important national initiatives for mapping and assessing risks to cultural heritage, its current configuration presents several inconsistencies that reduce its overall effectiveness. In many cases, the geolocation of archaeological sites proved inaccurate, with positional discrepancies that compromise the correspondence between mapped points and their actual locations. Furthermore, the database shows incomplete coverage, as numerous archaeological sites documented in the provincial Landscape Plans are not represented within the Risk Map. The descriptive records associated with mapped points also display significant gaps—particularly in key fields such as chronology, context, and state of conservation—which are essential for interpretation, comparison, and predictive analysis.

In addition to these issues of completeness and accuracy, the dataset presents structural limitations that hinder interoperability with other heritage databases. Although both the Risk Map and the Landscape Plans are available in vector format, they differ in their geometric representation and in the organisation of attribute tables: the Risk Map primarily uses point geometries to represent individual assets, while the Landscape Plans rely on polygonal features to define broader areas of archaeological interest or cultural significance. This heterogeneity, combined with the absence of standardised fields and harmonised classification criteria, prevents seamless integration of data from different provinces. As a result, cross-provincial analyses and multi-scalar interpretations remain challenging, limiting the potential of these datasets to support comprehensive cultural heritage management and territorial planning.

5.2. Study Limitations and Future Challenges

Although the results achieved by the ARPAS project demonstrate the effectiveness of an integrated and interdisciplinary approach to cultural landscape management, several limitations and challenges must be acknowledged. First, the current implementation of ARPAS is limited to a pilot area encompassing four Sicilian provinces. While this provides a solid methodological and technical foundation, extending the model to the entire regional or national territory will require substantial efforts in data harmonisation, institutional coordination, and enhancement of digital infrastructure. Importantly, data normalisation is not an automatic process but rather a complex and interpretative task that must be conducted by qualified personnel with expertise in the field, capable of ensuring consistency, reliability, and scientific accuracy across heterogeneous datasets. The variability of data produced by different regional administrations thus remains one of the main obstacles to achieving full interoperability.

From a technical perspective, further developments will be needed to ensure the scalability and long-term sustainability of the ARPAS infrastructure. The integration of additional information layers—such as environmental, climatic, and geological hazard data—will be essential to move toward a more comprehensive risk assessment framework. Likewise, the adoption of AI-based predictive tools could significantly enhance the system’s analytical capacity, supporting the early identification of threats and optimisation of preventive strategies.

One of the most promising future developments involves establishing a workflow to integrate data from the National Archaeological Geoportal (GNA) into ARPAS. This would enable the system to manage not only existing and officially recognised data, but also new datasets generated by ongoing archaeological investigations, thus ensuring that dynamic, up-to-date information contributes to continuous monitoring and heritage management.

Finally, an important goal closely linked to data sharing concerns the improvement of accessibility and openness of archaeological information. Making ARPAS accessible as a shared, web-based platform would provide the scientific community and institutions with a collaborative and transparent tool, promoting interoperability, public engagement, and interdisciplinary cooperation. In this perspective, the system could evolve into a digital ecosystem for cultural heritage, bridging research, policy, and society, and supporting the sustainable protection and enhancement of stratified landscapes.

6. Conclusions

Within the framework of the CHANGES project, an interdisciplinary methodology was adopted, integrating the diachronic archaeological and historical knowledge of the territory contributed by archaeologists with the expertise of architects in spatial planning and risk management. This approach promoted a comprehensive understanding of the landscape, viewed as a dynamic system shaped by historical processes and contemporary territorial transformations.

The collaboration enabled the landscape to be studied holistically, from complementary perspectives ranging from environmental and archaeological risk assessment to issues of scientific research and cultural heritage management. One of the most significant outcomes of the research was the establishment of an active partnership with the company Advice, which fostered constructive dialogue and effective cooperation between public institutions and private actors, combining scientific expertise with technological and IT competences in the development of the ARPAS geodatabase.

The creation and processing of the geodatabase also raised new methodological questions, for which several solutions were identified. First, data standardisation proved essential to overcome the heterogeneity of provincial and legacy documentation. Second, particular attention was paid to preserving the scientific dimension of the data, ensuring that the complex stratification of the landscape remained readable, queryable, and visible. Finally, the system was designed as a preventive and predictive tool, extending analysis beyond isolated monuments to encompass entire portions of the landscape.

Within this framework, it became evident that previously adopted tools present clear limitations. The Risk Map remains focused on individual assets, while preventive archaeology often emphasises potentiality, neglecting systemic landscape dimensions. ARPAS, by contrast, proposes an innovative model capable of integrating these approaches and providing a unified, multi-scalar vision of the cultural landscape, in which complexity is both documented and operationalized for conservation, management, and research purposes.

Another important achievement of the project has been the integration and standardisation of data from four provinces, which can now be queried jointly. This advancement makes the system useful not only for protection, conservation, and territorial enhancement, but also as a research tool in historical, archaeological, and architectural studies.

The next step should be to consolidate and expand this approach to include the remaining provinces of Sicily, thereby creating an innovative regional model for documentation and analysis. Such a model would overcome provincial limitations and contribute to building a unified and systemic vision of the Sicilian cultural landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing: all authors. Software and Figure 3: Advice. Sections: All authors: Section 1 and Section 6; E.F.: Section 2.1 and Section 3.1.1; G.M.G.: Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2, Section 2.2.3 and Section 3.1.3; E.P.: Section 2.2.4, Section 3.1.4, Section 3.1.5, Section 5, Section 5.1 and Section 5.2; D.P.: Section 3.1.6, Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3; E.P. and D.P.: Section 3.2. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)—Mission 4 Education and research—Component 2 From research to business—Investment 1.3, Notice D.D. 341 of 15/03/2022, entitled: Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society proposal code PE0000020—CUP E63C22001960006, duration until 28 February 2026.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Convenzione Europea del Paesaggio. Firenze. 20 October 2000. Available online: www.coe.int (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Corboz, A. Le territoire comme palimpseste. Diogène 1983, 121, 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, S.; Zubrow, E. Changing Places: The Archaeology of Regions and Spatial Change. Antiquity 1999, 73, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R. The Significance of Monuments: On the Shaping of Human Experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, G. Time Perspectives, Palimpsests and the Archaeology of Time. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2007, 26, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio d’Europa. Convenzione Quadro del Consiglio d’Europa sul Valore dell’Eredità Culturale per la Società. CETS No. 199. FARO. 27 October 2005. Available online: https://www.coe.int/it/web/venice/faro-convention (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- CHANGES—Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society—Funded by Ministerial Decree No. 1560 of 11 October 2022—CUP E63C22001960006, Under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Mission 4 “Education and Research,” Component 2 “From Research to Enterprise,” Financed by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. Available online: https://www.fondazionechanges.org/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Boscolo, G. La nozione giuridica di paesaggio identitario ed il paesaggio ‘a strati’. Riv. Giur. Urb. 2009, 379, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio (D.lgs. 22 Gennaio 2004, n. 42, ai Sensi dell’Art. 10 della l. 6 Luglio 2002, n. 137). Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 45, 24 Febbraio 2004, Suppl. ord. n. 28. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2004-02-24&atto.codiceRedazionale=004G0066 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Magnaghi, A. Documento Programmatico del Piano Paesaggistico Territoriale Regionale Puglia; Regione Puglia, Assessorato Assetto del Territorio: Bari, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Piano Organico di Inventariazione, Catalogazione ed Elaborazione della Carta del Rischio dei Beni Culturali, anche in Relazione all’Entrata in Vigore dell’Atto Unico Europeo: Primi Interventi (GU Serie Generale n.96 del 26-04-1990). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1990-04-26&atto.codiceRedazionale=090G0127&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Cavalieri, E. La tutela dei beni culturali. Una proposta di Giovanni Urbani. Riv. Trimest. Dirit. Pubblico 2011, 2, 473–494. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage Watch. AI. Available online: https://heritagewatch.ai/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Asprogerakas, E.; Gourgiotis, A.; Pantazis, P.; Samarina, A.; Konsoula, P.; Stavridou, K. The gap of cultural heritage protection with climate change adaptation in the context of spatial planning. The case of Greece. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Environmental Design, Virtual, 23–24 October 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 899, p. 012072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon, P.; Ursun, A.; Sandu, I. Heritage Management Using GIS. In Proceedings of the 6th International Multidisciplinary Geoconference, SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 28 June–7 July 2016; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Valagussa, A.; Frattini, P.; Crosta, G.; Spizzichino, D.; Leoni, G.; Margotitni, C. Multi-risk analysis on European cultural and natural UNESCO heritage sites. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 2659–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; DeSilvey, C.; Holtorf, C.; Macdonald, S.; Bartolini, N.; Breithoff, E.; Fredheim, H.; Lyons, A.; May, S.; Morgan, J.; et al. Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, M.; Fabiani, U. Appendice. Metodologie geomatiche per la referenziazione delle informazioni archeologiche. In Atlante di Roma Antica. Biografia e Ritratti della Città; Carandini, A., Carafa, P., Eds.; Electa: Milano, Italy, 2012; pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mastroianni, D. Prefazione. Gli elementi del Paesaggio e gli strumenti per raccontarlo. In Storytelling dei Paesaggi. Metodologie e Tecniche per la Loro Narrazione; Mastroianni, D., Oriolo, R., Vivona, A., Eds.; Il Sileno: Lago, Italy, 2021; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cambi, F. Archeologia dei Paesaggi Antichi: Fonti e Diagnostica, 1st ed.; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2003; pp. 19–60. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe, G. Storia, archeologia e globalità. In Storia e Archeologia Globale; Biasco, R., Volpe, G., Eds.; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2015; Volume I, pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Attema, P.; Bintliff, J.; van Leusen, M.; Bes, F.; De Haas, T.; Donev, D.; Jongman, W.; Kaptijn, E.; Mayoral, V.; Menchelli, S.; et al. A guide to good practice in Mediterranean surface survey project. J. Greek Archaeol. 2020, 5, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S. Drones in Archaeology. State-of-the-art and future perspectives. Archaeol. Prospect. 2017, 24, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, A. Digital Survey from Drone in Archaeology: Potentiality, Limits, Territorial Archaeological Context and Variables. In Proceedings of the International Conference Florence Heri-Tech: The Future of Heritage Science and Technologies, Online, 14–16 October 2020; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/949/1/012075 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Pecci, A. Introduzione all’Utilizzo dei Droni in Archeologia; Arbor Sapientiae: Roma, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Masini, N.; Abate, N.; Gizzi, F.T.; Vitale, V.; Minervino Amodio, A.; Sileo, M.; Biscione, M.; Lasaponara, R.; Bentivenga, M.; Cavalcante, F. UAV LiDAR Based Approach for the Detection and Interpretation of Archaeological Micro Topography Under Canopy—The Rediscovery of Perticara (Basilicata, Italy). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdani, J. GIS in archeologia. Groma 2009, 2, 421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Vanni, E.; Saccoccio, F.; Cambi, F. Il Paesaggio come strumento interpretativo. Nuove proposte per vecchi paesaggi. In Storytelling dei Paesaggi. Metodologie e Tecniche per la Loro Narrazione; Mastroianni, D., Oriolo, R., Vivona, A., Eds.; Il Sileno: Lago, Italy, 2021; pp. 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brancato, R. Topografia della Piana di Catania. Archeologia, Viabilità e Sistemi Insediativi; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2020; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri, L.; Baiocchi, V.; Monti, F.; Cusimano, L.; Fiorillo, A.; Gianni, V.; Rossi, C.; Attema, P.; Rolfo, M.F. Low-cost GPS/GNSS Real Time Kinematic receiver to build a cartographic grid on the ground for an archaeological survey at Piscina Torta (Italy). Acta IMEKO 2023, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, M.; Kurtulgu, Z.; Pırtı, A. Evaluation of the Repeatability and Accuracy of RTK GNSS under Tree Canopy. J. Sylva Lestari 2025, 13, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.-J. Ethical Challenges in Digital Public Archaeology. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 2018, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, L.M. Digital Archaeological Ethics: Successes and Failures in Disciplinary Attention. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 2020, 3, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K.A.; Mazzilli, F. Challenges in Open Data: A TRAJ Perspective. Theor. Rom. Archaeol. J. 2022, 5, 9899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Fradley, M. Ethical Considerations for Remote Sensing and Open Data in relation to the endangered archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa project. Archaeol. Prospect. 2021, 28, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Articolo 29, D.lgs. 42/2004, Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio. Available online: https://www.bosettiegatti.eu/info/norme/statali/2004_0042.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Istituto Centrale per l’Archeologia (ICA), Linee Guida per la Procedura di Verifica dell’Interesse Archeologico, DPCM 14 Febbraio 2022, G.U. n. 88, 14 Aprile 2022, 5. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/04/14/22A02344/SG (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Güll, P. Archeologia Preventiva: Il Codice Appalti e la Gestione del Rischio Archeologico; Dario Flaccovio Editore: Palermo, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto Legislativo 31 Marzo 2023, n. 36—Codice dei Contratti Pubblici [Allegato I.8 “Verifica Preventiva dell’Interesse Archeologico”, Richiamato all’Art. 41, Comma 4]; Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, Serie Generale n. 88 del 14 April 2022 (DPCM 14 February 2022). 2023. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2023-03-31&atto.codiceRedazionale=23G00044&elenco30giorni=true (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Available online: https://gna.cultura.gov.it (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Available online: https://ica.cultura.gov.it/geoportale-nazionale-per-larcheologia/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Approvazione delle Linee Guida del Piano Territoriale Paesistico Regionale. Assessorato dei Beni Culturali ed Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione, D.A. No. 6080/1999. Available online: https://www2.regione.sicilia.it/beniculturali/dirbenicult/normativa/decretiecircolaribca/D21maggio1999.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Caliò, L.M.; Fino, A.; Gerogiannis, G.M.; Rizzo, M.S. Theatrum Ibidem Erat Eminentissimum. La Riscoperta del Teatro di Agrigento. In Akragas/Agrigento: Una Capitale, 25 Secoli; Kalos: Palermo, Italy, 2025; Volume 3, pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Caliò, L.M.; Fino, A.; Gerogiannis, G.M. MLS con sensore LiDAR Apple per lo scavo archeologico: Applicazioni pratiche. In Me.Te. Digitali. Mediterraneo in Rete tra Testi e Contesti, Proceedings of the Del XIII Convegno Annuale AIUCD, Catania, Italy, 28–30 May 2024; Di Silvestro, A., Spampinato, D., Eds.; pp. 547–551. [CrossRef]

- Blancato, M.; Militello, P.; Palermo, D.; Panvini, R. (Eds.) Pantalica e la Sicilia nelle Età di Pantalica, Atti del Convegno di Sortino (Siracusa) 15–16 Dicembre 2017; Creta Antica; ALDO AUSILIO EDITORE: Padova, Italy, 2017; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Militello, P.; Storaci, E.; Figuera, M.P. Nuovi dati dalla revisione dei materiali dai vecchi scavi. In L’Isola dei Tesori. Ricerca Archeologica e Nuove Acquisizioni. Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Agrigento, Museo Archeologico Regionale “P. Griffo”, 14–17 Dicembre 2023); Parello, M.C., Ed.; Ante Quem: Bologna, Italy, 2024; pp. 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Militello, P.; Sammito, A.M.; Buscemi, F.; Figuera, M.; Messina, T.; Platania, E.; Sferrazza, P.; Sirugo, S. La Capanna 1 di Calicantone: Relazione preliminare sulla campagna di scavo 2012–2015. RSP 2018, 68, 255–304. [Google Scholar]

- Platania, E. Paesaggi culturali pastorali: Calicantone (RG) un esempio dalla Sicilia dell’Età del Bronzo. In Archeologia e Paesaggi Culturali. Casi Studio del Mediterraneo Antico; Messina, T., Platania, E., Eds.; Catania-Varsavia: Catania, Italy, 2022; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, T.; Platania, E. Strutture da combustione e resti animali nel bronzo antico siciliano: Per un approccio integrato alla definizione degli spazi domestici e dei sistemi di cottura alimentari. In Spazi Domestici Nell’Età del Bronzo: Memorie del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona; Sezione Scienze Dell’Uomo; 2023; Volume 16, Available online: https://www.academia.edu/123940337/STRUTTURE_DA_COMBUSTIONE_E_RESTI_ANIMALI_NEL_BRONZO_ANTICO_SICILIANO_PER_UN_APPROCCIO_INTEGRATO_ALLA_DEFINIZIONE_DEGLI_SPAZI_DOMESTICI_E_DEI_SISTEMI_DI_COTTURA_ALIMENTARI (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Buscemi, F.; Figuera, M. The Contribution of Digital Data to the Understanding of Ritual Landscapes. The Case of Calicantone (Sicily). Open Archaeol. 2019, 5, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militello, P. Calaforno 1: L’Ipogeo e il Territorio: Scavi dell’Università di Catania 2013–2017; Archeopress: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]