Pottery as an Indicator of Mountain Landscape Exploitation: An Example from the Northern Pindos Range of Western Macedonia (Greece)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. History of Research

1.2. Archeological Background

1.3. Research Aims

2. Materials and Methods

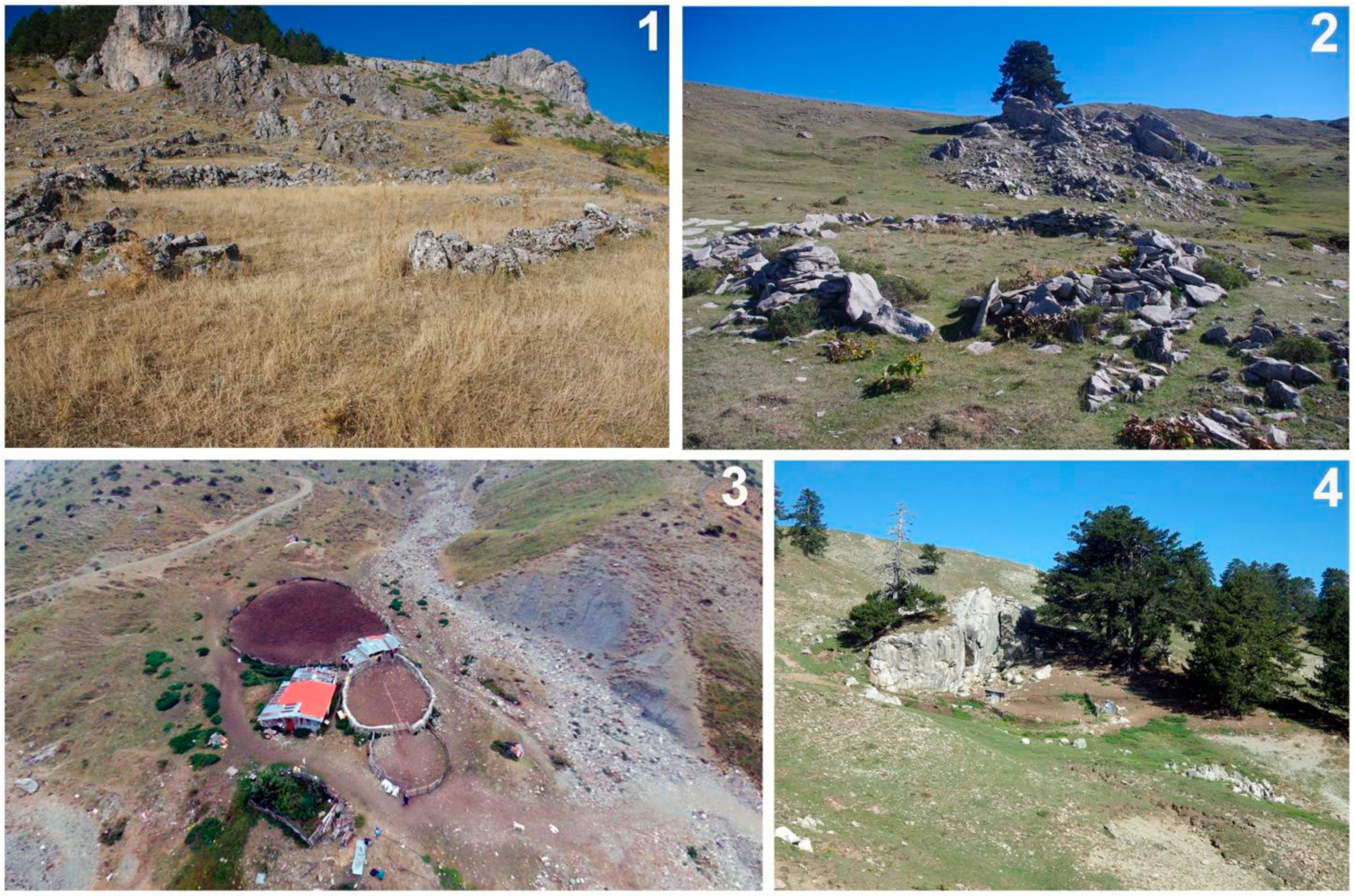

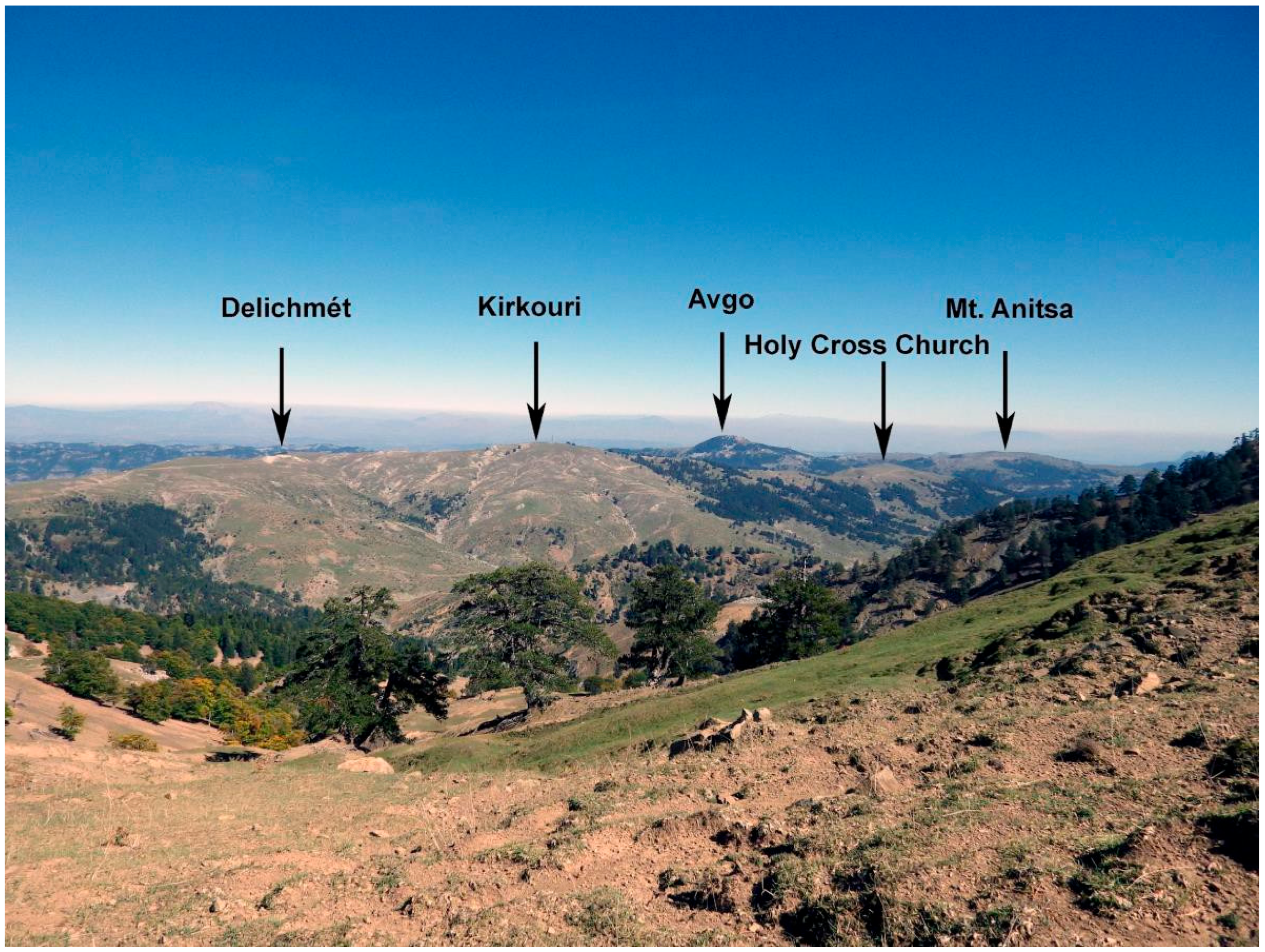

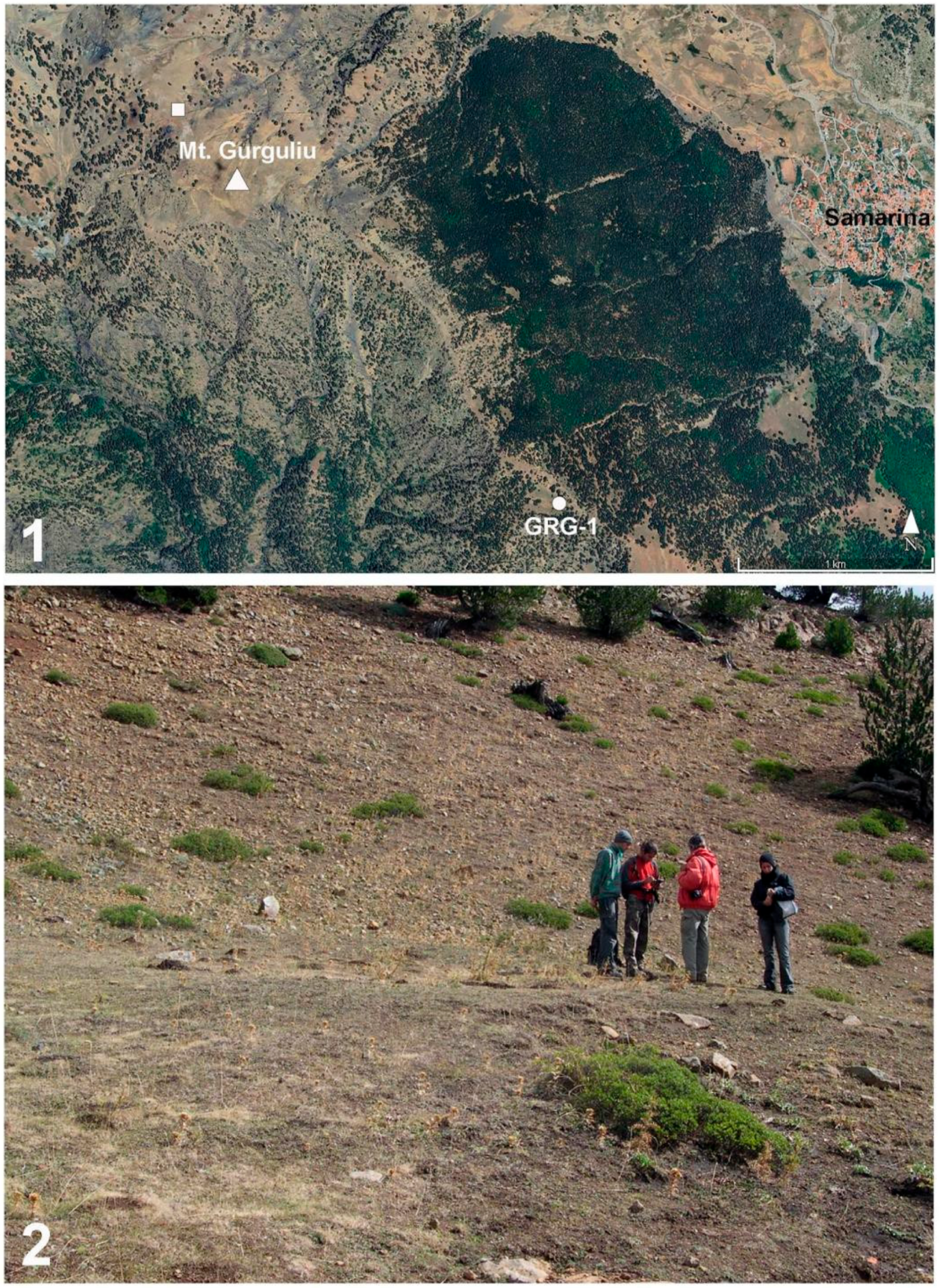

2.1. The Surveys and the Sites

2.2. The Pottery Assemblages

| Site | Sample Name | Tot. n. of Potsherds | Diagnostic Sherds | Represented Groups | Chronology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Camp | HC | 65 | 9 | C2, G4, G5, G6 | 6th c. AD? |

| Kirkouri | KRK | 39 | 3 | A2, G3, G4, G5 | 4th–7th c. AD |

| Mts. Gurguliu/Bogdhani | - | 2 | 2 | “Slavic Ware” | 9th c. AD |

| Mt. Anitsa | NTS | 6 | 2 | F1, G3 | Undefined |

| Holy Cross Church | SMC | 9 | 3 | G2, G4 | Undefined |

| Avgo | VGO | 8 | 3 | A3, A4, G2, G3 | Undefined |

| Aspra Petra | SPR | 1 | 1 | A1 | Undefined |

| Mt. Vasilitsa | VSL | 19 | 3 | G1 | 6th–12th c. AD |

| Mirminda Pass | VLC | 1 | 1 | G3 | Undefined |

| TOTAL | 150 | 27 |

Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Typology

3.1.1. Coarse Ware

Cooking Pots

Cooking Pots with Decoration

3.1.2. Fine Common Ware: Ollae

3.1.3. Globular Vessel

3.1.4. Transport Containers: Amphorae

3.2. Ceramic Fabric Groups

3.2.1. Coarse Ware

3.2.2. Fine Common Ware Fabrics

3.2.3. Fine Tableware Fabrics

3.2.4. Amphorae Fabrics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, C. Pastoral Transhumance in the Southern Balkans as a Social Ideology: Ethnoarcheological Research in Northern Greece. Am. Anthropol. 1993, 95, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandris, J.G. The Stina and the Katun: Foundations of a Research Design in European Highland Zone Ethnoarchaeology. World Archaeol. 1985, 17, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, R. Nomads in Archaeology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fragnoli, P. Pottery production in pastoral communities: Archaeometric analysis on the LC3-EBA1 Handmade Burnished. Ware from Arslantepe (in the Anatolian Upper Euphrates). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, P.; Nandris, J. (Eds.) Highland Zone Exploitation in Southern Europe; Monografie di Natura Bresciana; Museo Civico di Scienze Naturali di Brescia: Brescia, Italy, 1994; Volume 20, pp. 7–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, A.J.; Efstratiou, N.; Adam, E. First evidence for the Palaeolithic in Aegean Thrace. In The Palaeolithic Archaeology of Greece and Adjacent Areas. Proceedings of the ICOPAG Conference, Ioannina; Bailey, G.N., Adam, E., Panagopoulou, E., Perlès, C., Zachos, K., Eds.; British School at Athens Studies 3: London, UK, 1999; pp. 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, N.C.; Savina, M.E. The Earliest Farmers in Macedonia. Antiquity 1997, 71, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, N.C. Some Aspects of the Prehistoric Occupation of Grevena. In Ancient Macedonia VI. Papers Read at the Sixth International Symposium Held in Thessaloniki, October 15–19, 1996; Institute of Balkan Studies: Thessaloniki, Greece, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1345–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolou, G.; Venieri, K.; Mayoral, A.; Dimaki, S.; Garcia-Molsosa, A.; Georgiadis, M.; Orengo, H.A. Integrating Legacy Survey Data into GIS-Based Analysis: The Rediscovery of the Archaeological Landscapes in Grevena (Western Macedonia, Greece). Archaeol. Prospect. 2024, 31, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstratiou, N.; Biagi, P.; Elefanti, P.; Karkanas, P.; Ntinou, M. Prehistoric exploitation in Grevena highland zones: Hunter andherders along the Pindus chain of Western Macedonia (Greece). Word Archaeol. 2006, 38, 415–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, P.; Efstratiou, N.; Starnini, E.; Nisbet, R. Traces of Mesolithic occupation in the Pindos Mountains of western Macedonia (Greece). Mesolith. Misc. 2023, 30, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, P.; Nisbet, R.; Starnini, E.; Efstratiou, N.; Michniak, R. Where mountains and Neanderthals meet: The Middle Palaeolithic settlement of Samarina in the Northern Pindus (Western Macedonia, Greece). Eurasian Prehistory 2016, 13, 3–76. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, P.; Starnini, E.; Efstratiou, N.; Nisbet, R.; Hughes, P.D.; Woodward, J.C. Mountain Landscape and Human Settlement in the Pindus Range: The Samarina Highland Zones of Western Macedonia, Greece. Land 2023, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wace, A.J.B.; Thompson, M.S. The Nomads of the Balkans. In An Account of Life and Customs among the Vlachs of Northern Pindus; Methuen & Co.: London, UK, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Morrisson, C. Popolamento, economia e società dell’Oriente bizantino. In Il Mondo Bizantino. L’Impero Romano d’Oriente (330-641); Morrisson, C., Ed.; Giulio Einaudi Editore: Torino, Italy, 2007; pp. 197–235. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, M. Le Origini Dell’economia Europea: Comunicazioni e Commercio 300-900 d.C; Vita & Pensiero: Milano, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fasolo, M. La Via Egnatia, I. Da Apollonia e Dyrrachium ad Herakleia Lynkestidos; Istituto Grafico Editoriale: Roma, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bavant, B. L’Illirico. In Il Mondo Bizantino. L’Impero Romano d’Oriente (330-641); Morrisson, C., Ed.; Giulio Einaudi Editore: Torino, Italy, 2007; pp. 325–375. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, N.G.L. Epirus. The Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and the Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Nigdelis, P. Roman Macedonia (168 BC–AD 284). In The History of Macedonia; Koliopoulos, I., Ed.; Museum of the Macedonian Struggle Foundation: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2007; pp. 51–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, M.R. Observations on Vlach sheep-milking and milk-processing in south-east Europe. Anthropozoologica 1995, 20, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Winnifrith, T.J. Vlachs. In Minorities in Greece. Aspects of a Plural Society; Clogg, R., Ed.; Hurst & Company: London, UK, 2002; pp. 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Curta, F. Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages 500–1250; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser, J.H. Dark age settlements in Grevena, Greece (southwestern Macedonia). In Les Villages Dans l’Empire Byzantin; Lefort, J., Morrisson, C., Sodini, J.-P., Eds.; IVe–XIVe Siècle; Lethielleux: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Koukoudis, A.I. The Vlachs. Metropolis and Diaspora; Studies on the Vlachs II; Zitros: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Curta, F. Medieval Vlach Transhumance: Re-assessing the Evidence. In Naţiuni, Naţionalism Şi Perspective Interetnice în Transilvania: In honorem Sorin Mitu la 60 de Ani; Bărbulescu, C., Cârja, I., Eppel, M., Fehér, A., Popovici, V., Sima, A.V., Turcu, L., Eds.; MEGA: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2025; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Frachetti, M.D. Variability and Dynamic Landscapes of Mobile Pastoralism in Ethnography and Prehistory. In The Archaeology of Mobility. Old and New World Nomadism; Barnard, H., Wedendrich, W., Eds.; Cotsen Advanced Seminars, Institute of Archaeology, UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 4, pp. 366–396. [Google Scholar]

- Kocój, E. Artifacts of the Past as Traces of Memory. The Aromanian Cultural Heritage in the Balkans. Res. Hist. 2016, 41, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimmis, K.P.; Marini, C.; Katsilerou, Z.; Marinou, M.; Kapsali, K.; Perdikopoulou, M.; Soumintoub, V.; Drnić, K.B.; Drnić, I.; Theodoroudi, E.; et al. A study of creative object biographies. Can creative arts be a medium for understanding object-human interaction? Archaeol. Dialogues 2023, 30, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerkens, J.W. Nomadic potters. Relationships between Ceramic Technologies and Mobility Strategies. In The Archaeology of Mobility. Old and New World Nomadism; Barnard, H., Wendrich, W., Eds.; Cotsen Advanced Seminars, Institute of Archaeology, UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 4, pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, P. Present to past in the Pindhos: Diversification and specialisation in mountain economies. In Archeologia della Pastorizia Nell’Europa meridionale I, Atti Della Tavola Rotonda Internazionale Chiavari, 22–24 Settembre 1989; Maggi, R.; Nisbet, R.; Barker, G., Eds. Riv. di Studi Liguri 1991, 56, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ntassiou, K.; Doukas, D. Recording and mapping traditional transhumance routes in the South-Western Macedonia, Greece. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburd, D. Territoriality and Iranian Pastoralism: Looking out from Kerman. In Mobility and Territoriality. Social and Spatial Boundaries among Foragers, Fishers, Pastoralists and Peripatetics; Casimir, M.J., Rao, A., Eds.; Berg: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 1992; pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Cambi, F. Archeologia (Globale) Dei Paesaggi (Antichi). Metodologie, procedure, tecnologie. In Geografie Del Popolamento: Casi di Studio, Metodi e Teorie; Macchi Jánica, G., Ed.; Università Degli Studi di Siena: Siena, Italy, 2009; pp. 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Milanese, M. La lezione dell’archeologia globale. Retrospettive e prospettive di una metodologia della ricerca storica. In Attualità e Sviluppi di Metodi e Idee I; Mannoni, T., Ed.; All’Insegna del Giglio: Firenze, Italy, 2021; pp. 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, J. After Antiquity: Ceramics and Society in the Aegean from the 7th to the 20th Century A.C. A Case Study from Boeotia, Central Greece; Archaeological Studies Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Langhor, R. Types of tree windthrow. Their impact on the environment and their importance for the understanding of archaeological excavation data. Helinium 1993, 33, 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gedeon, D. An Abridged History of the Greek-Italian and Greek-German War, 1940–1941: (Land Operations); Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate: Athens, Greece, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roman Provincial Coinage I online. From the Death of Caesar to the Death of Vitellius (44 BC–AD 69). Available online: https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/coins/1/1428 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Burrer, F. Münzprägung und Geschichte des Thessalischen Bundes in der Römischen Kaiserzeit bis auf Hadrian (31 v. Chr.–138 n.Chr.); Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag: Saarbrücken, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Catalogue of the Very Celebrated Collection of Works of Art, the Property of Samuel Rogers, Esq., Deceased: Comprising Ancient and Modern Pictures, Drawings and Engravings, Egyptian, Greek and Roman Antiquities, Greek Vases, Marbles, Bronzes, and Terra-Cottas, and Coins; also, the Extensive Library; Copies of Rogers’s Poems, Illustrated; the Small Service of Plate and Wine; Christie and Manson’s Offices: London, UK, 1856.

- Grose, S. Catalogue of the McClean Collection of Greek Coins, Fitzwilliam Museum; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1926; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, P.; Nisbet, R. Archeologia della pastorizia dei Vlah di Samarina (Macedonia Occidentale, Grecia). In Un Accademico Impaziente. Studi in Onore di Glauco Sanga; Ligi, G., Pedrini, G., Tamisari, F., Eds.; Edizioni dell’Orso: Alessandria, Italy, 2018; pp. 581–593. [Google Scholar]

- Drougou, S.; Kallini, C. Kastri Near Polyneri. Grevena prefecture, 2001. Arxaiologiko Ergo Sti Makedonia Kai Thrak. 2001, 15, 587–593. [Google Scholar]

- Tomka, S.A.; Stevenson, M.G. Understanding abandonment processes: Summary and remaining concerns. In Abandonment of Settlements and Regions. Ethnoarchaeological and Archaeological Approaches; Cameron, M.C., Tomka, S.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Milanese, M. Le classi ceramiche nell’archeologia medievale, tra terminologie, archeometria e tecnologia. In Le Classi Ceramiche. Situazione Degli Studi. Atti Della 10 Giornata di Archeometria Della Ceramica (Roma, 5–7 Aprile 2006); Fabbri, B., Bandini, G., Gualtieri, S., Eds.; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2009; pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Orton, C.; Hughes, M. Pottery in Archaeology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo di Caprio, N. Ceramica in Archeologia 2: Antiche Tecniche di Lavorazione e Moderni Metodi di Indagine; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Winnifrith, T.J. The Vlachs: The History of a Balkan People; Duckworth: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.; Tourtellotte, A. The ethnological survey of pastoral transhumant sites in the Grevena region, Greece. J. Field Archeol. 1993, 20, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curta, F. Medieval Europe from Another Angle. Volume I: The People; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Curta, F. The Making of the Slavs. History and Archeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Curta, F. The early Slavs in the northern and eastern Adriatic region. A critical approach. Archeol. Mediev. 2010, 37, 307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Charanis, P. Ethnic Changes in the Byzantine Empire in the Seventh Century. Dumbart. Oaks Pap. 1959, 13, 23–44. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1291127 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vryonis, S., Jr. The Slavic Pottery (jars) from Olympia, Greece. In Byzantine Studies. Essays on the Slavic World and the Eleventh Century; Vryonis, S., Jr., Ed.; Aristide, D. Caratzas: New Rochelle, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vida, T.; Völling, T. Das slawische Brandgräberfeld von Olympia; Archäologie in Eurasien 9, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Berlin / Eurasien-Abteilung; Rahden/Westf: Leidorf, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou, T.K.; Vionis, A.K. A petrographic contribution to the study of handmade vessels from Early medieval Greece: A case-study from Boeotia and Achaea. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 65, 105226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupert, P. Céramique slave à Argos (585 ap. J.-C.). Bull. De Corresp. Hellénique. Supplément 1980, 6, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, T.E. An early Byzantine (Dark Age) settlement at Isthmia: A preliminary report. J. Rom. Archaeol. Suppl. Ser. 1993, 8, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, G.D.R. Excavations at Sparta: The Roman Stoa, 1988–1991 Preliminary Report, Part 1: (C) Medieval Pottery. Annu. Br. Sch. Athens 1993, 88, 251–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratto, S. Il vasellame ceramico da mensa e da cucina: Vita quotidiana e indicatori commerciali. In Augusta Bagiennorum. Storia e Archeologia di una Città Augustea; Preacco, M.C., Ed.; Celid: Torino, Italy, 2014; pp. 157–200. [Google Scholar]

- Nandris, J. The Balkan dimension of Highland zone in pastoralism. In Archeologia della Pastorizia Nell’Europa meridionale I, Atti Della Tavola Rotonda Internazionale Chiavari, 22–24 Settembre 1989; Maggi, R.; Nisbet, R.; Barker, G., Eds. Riv. di Studi Liguri 1991, 56, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Voytek, B. Resource use and the inference of a pastoral economy. In Archeologia della Pastorizia Nell’Europa meridionale I, Atti Della Tavola Rotonda Internazionale Chiavari, 22–24 Settembre 1989; Maggi, R.; Nisbet, R.; Barker, G., Eds. Riv. di Studi Liguri 1991, 56, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hersberger, S.; Ganz, K.; Kiener, L.; Gobet, E.; van Vugt, L.; Giagkoulis, T.; Breu, S.; Heiri, O.; Vogel, H.; Zahajská, P.; et al. 6000 years of vegetation and fire history at the timberline ecotone site Drakolimni Smolikas in the Pindos Mountains, northwestern Greece. Arct. Antart. Alp. Res. 2025, 57, 2545038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curta, F. Were there any Slavs in the seventh-century Macedonia? Istorija 2012, XLVII, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Curta, F. Pastoralism and Nomadism: An Archaeological Bifurcation. Mediev. Archaeol. 2025, 69, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Vingo, P.; Merlini, V.; Biagi, P.; Starnini, E.; Efstratiou, N. Pottery as an Indicator of Mountain Landscape Exploitation: An Example from the Northern Pindos Range of Western Macedonia (Greece). Heritage 2025, 8, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120500

de Vingo P, Merlini V, Biagi P, Starnini E, Efstratiou N. Pottery as an Indicator of Mountain Landscape Exploitation: An Example from the Northern Pindos Range of Western Macedonia (Greece). Heritage. 2025; 8(12):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120500

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Vingo, Paolo, Vittoria Merlini, Paolo Biagi, Elisabetta Starnini, and Nikos Efstratiou. 2025. "Pottery as an Indicator of Mountain Landscape Exploitation: An Example from the Northern Pindos Range of Western Macedonia (Greece)" Heritage 8, no. 12: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120500

APA Stylede Vingo, P., Merlini, V., Biagi, P., Starnini, E., & Efstratiou, N. (2025). Pottery as an Indicator of Mountain Landscape Exploitation: An Example from the Northern Pindos Range of Western Macedonia (Greece). Heritage, 8(12), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120500