Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model outperformed traditional models (Logit, Probit, and Extreme Value), achieving 98% accuracy in predicting financial distress in Taiwan’s electronics industry.

- Second bullet. Two strong financial distress indicators were identified, Return on Assets (below 7.03%) and Total Asset Growth Rate (below −9.05%), showing nonlinear effects on financial distress.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The superior performance of the ANN highlights the effectiveness of advanced machine learning techniques in capturing complex, nonlinear financial patterns for more accurate distress prediction.

- Identifying specific threshold indicators supports early warning systems and data-driven risk management, enabling firms and investors to make more informed financial decisions.

Abstract

This study compares Logit, Probit, Extreme Value, and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models using data from 2012 to 2024 in the Taiwan electronics industry. ANN outperforms traditional models, achieving 98% accuracy in predicting financial distress. Two robust distress signals are identified: Return on Assets (threshold: 7.03%) and Total Asset Growth (threshold: −9.05%). The nonlinear impacts of financial distress on variables are analyzed, with a focus on contextual considerations in decision-making. These findings bring attention to the importance of utilizing advanced techniques like ANN for improved predictive accuracy, offering profound clarification for risk assessment and management.

1. Introduction

Financial distress prediction and risk management are interconnected concepts critical for ensuring the financial stability and sustainability of companies. Predicting financial distress involves identifying and assessing warning signs or early indicators that might signal impending financial difficulties or instability within a business [1]. Conversely, risk management deals with the proactive identification, assessment, and mitigation of risks that could negatively affect a company’s financial health and operational continuity [2]. Together, these practices form integral parts of a larger framework aimed at corporate resilience and sustainability [3]. By actively identifying and mitigating risks, companies can enhance their capacity to endure economic downturns, industry disruptions, and other external shocks [4]. This resilience helps businesses maintain financial stability, safeguard shareholder value, and uphold their long-term competitiveness and viability in an increasingly unpredictable and volatile business landscape [5].

Financial distress prediction is a vital area of research in finance and accounting, with implications for stakeholders such as investors, creditors, regulators, and policymakers [1,6]. Financial distress occurs when a company experiences difficulties in meeting its financial obligations, which could ultimately cause insolvency, reduced profitability, or even bankruptcy [7,8]. Detecting early warning signs of financial distress is essential for stakeholders to reduce risks, make informed decisions, and take appropriate actions to safeguard their interests [9,10]. In recent years, researchers have increasingly turned to advanced analytical techniques, including deep learning and natural language processing, to improve the accuracy and timeliness of financial distress prediction [11,12,13,14,15].

The theoretical foundation of financial distress prediction draws from various disciplines, including finance, accounting, and economics [16]. At its core, financial distress prediction aims to identify signals in financial data that may indicate a company’s vulnerability to financial instability [17]. Accounting theory sets the stage for understanding the relationships between financial variables, earnings components, and cash flow dynamics [18]. Traditional distress prediction models often rely on quantitative financial indicators derived from balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements [19].

As global markets become increasingly volatile, early identification of financial distress enables firms, investors, and policymakers to take measures to lessen financial risks. Traditionally, statistical models such as Altman’s Z-score, Springate, Zmijewski, and Grover models have been widely employed to predict financial distress, offering insight into corporate solvency through financial ratio analysis [20,21]. However, with the rise in big data and technological progress, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) have significantly boosted financial distress prediction accuracy by processing large-scale, heterogeneous, and imbalanced datasets [22,23]. Recent studies highlight the effectiveness of deep learning approaches and multimodal data fusion in capturing complex relationships between financial, textual, and environmental factors [24,25]. Furthermore, the integration of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) performance indicators has introduced a multidimensional perspective on corporate financial stability, making a point of the growing link between sustainability practices and financial resilience [26]. The contemporary financial distress prediction research reflects an evolution from purely financial indicators toward data-driven, intelligent models that improve predictive reliability across industries and regions.

Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning have improved financial distress prediction by capturing complex, nonlinear relationships among financial indicators, textual disclosures, and environmental factors. Yet, existing studies rarely integrate high-resolution, industry-specific datasets, employ custom ANN architectures, or examine threshold effects in key financial ratios such as ROAA and TAG.

This study addresses these gaps by combining quantitative financial analysis with deep learning for early detection of financial distress in Taiwan’s electronics sector using TEJ data. A multi-layered ANN is constructed, benchmarked against traditional methods, and used to identify nonlinear threshold effects in ROAA (7.03%) and TAG (−9.05%). Subsample analysis reveals regime-dependent effects, providing both statistical and economic insights. The ANN achieves superior predictive accuracy (~98%), highlighting the value of contextual, industry-specific modeling and advanced neural architectures.

By integrating threshold analysis with deep learning, this research improves financial distress prediction accuracy and delivers actionable insights for risk management, bridging conventional financial ratios with modern AI-driven approaches. The study contributes methodologically by demonstrating the robustness of ANNs in handling imbalanced and nonlinear financial data and practically by offering early warning indicators to support corporate resilience.

2. Related Literature

Financial distress prediction models have evolved significantly over time, driven by the need for more accurate and generalizable approaches to identify companies at risk of financial instability. Early models, such as Altman’s Z-score model (1968), laid the groundwork by primarily focusing on accrual-based financial ratios. However, the limitations of these models in terms of generalizability across different industries and periods became apparent as researchers sought more robust predictive tools.

The importance of cash flow information in predicting financial distress was first highlighted by seminal studies, which showed that cash flow components could improve prediction accuracy [27]. This advantage over accrual-based models was further confirmed by Aziz and Lawson [28]. Subsequent research emphasized the effectiveness of mixed models combining cash and accrual information [29,30]. Despite these improvements, generalizability remained a concern, as existing models often struggled to predict distress across different samples and periods [31,32].

The advent of machine learning and advanced statistical methods has offered new opportunities to enhance both prediction accuracy and generalizability. Researchers have applied techniques such as Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, and Neural Networks to develop more sophisticated models [33,34]. Moreover, incorporating network analysis and feature selection has further improved model performance, providing more comprehensive approaches to financial risk assessment [35,36].The evolution of financial distress prediction models reflects a transition from traditional accrual-based approaches to more sophisticated cash flow integrated models, driven by the quest for greater accuracy and generalizability. The adoption of machine learning techniques and advanced statistical methodologies has further propelled the development of predictive models, offering promising solutions for identifying companies at risk of financial distress across diverse contexts and periods.

Recent research has shown considerable advancements in predicting financial distress by integrating machine learning, artificial intelligence, and hybrid analytical models. While traditional statistical methods like logistic regression remain dependable benchmarks [20,37], current studies are increasingly focused on enhancing predictive accuracy using nonlinear, data-driven techniques. Machine learning techniques such as Support Vector Machines [38], Random Forests [39], and ensemble methods like AdaBoost and CUSBoost [22,40] have been utilized to boost model robustness and adaptability. Deep learning-based frameworks have become formidable alternatives, utilizing multimodal data [25], textual and sentiment analysis [26], and attention-guided neural networks [24,41] to identify complex, non-financial factors of distress. Furthermore, hybrid models addressing issues like data imbalance and missing information—such as case-based reasoning [23] and Lightspace-SMOTE frameworks [42]—show superior performance in practical applications. These novel approaches signal a shift from exclusively ratio-based models [21,43] to comprehensive, data-rich predictive systems capable of early and accurate detection of financial distress across various industries.

Financial distress prediction uses quantitative and computational methods like discriminant analysis, logistic regression, and machine learning models (decision trees, neural networks, and support vector machines) to assess a firm’s insolvency risk. By analyzing financial ratios, market indicators, and qualitative factors, these models help organizations, investors, and regulators manage risks and boost financial stability. This research emphasizes early warning signals to bolster resilience and preserve shareholder value, advocates advanced analytical techniques for more accurate predictions, and introduces a novel methodology combining quantitative analysis with deep learning to improve predictions and risk strategies.

3. Data and Methodology

Anticipating financial difficulties due to transformation risks requires a thorough evaluation of numerous factors that may impact an organization’s financial health. A key element is undertaking a detailed cost–benefit analysis to assess the financial feasibility of the transformation by considering expected expenses, projected benefits, and their timing [44]. Additionally, cash flow analysis is vital for evaluating the transformation’s impact on liquidity, including potential disruptions to income streams or the need for increased working capital [45]. It is also crucial to assess the organization’s debt levels, capacity to service debt, and debt maturity profiles in light of planned transformation investments to determine its ability to manage debt obligations amid possible disruptions [46]. Revenue and profit forecasts should be analyzed within the scope of transformation initiatives, taking into account shifts in market demand, competition, and pricing strategies [47]. By incorporating these factors into predictive models and utilizing advanced analytics, organizations can enhance their capability to foresee and mitigate the risk of financial distress resulting from transformation initiatives.

Table 1 presents a detailed summary of the principal financial metrics employed in forecasting the probability of financial distress for businesses. Each variable in the table provides distinct insights into various facets of a company’s financial condition and performance.

Table 1.

Financial Distress Prediction Variables and Explanations.

3.1. Data Collection

The data for this investigation were sourced from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) database, covering the years 2012 to 2024. It includes information on companies in the Taiwanese electronics sector, featuring both financially troubled firms and those without such issues. After removing missing values, the empirical analysis was conducted on 11,787 observations. The dataset represents a wide array of 1014 companies, offering a thorough perspective on the dynamics of the Taiwan electronics industry during the specified period. The careful selection process ensures that the dataset accurately portrays the characteristics and trends of both distressed and non-distressed firms, enabling a robust analysis of the factors affecting financial distress and its impact on companies within this sector.

Financial distress (FD) is identified using event-based indicators from TEJ. A firm year is coded as distressed if the firm is subsequently delisted or removed from the OTC market due to financial or operational failure; all years prior to such exit are also classified as distressed. Distress is thus defined as ex post. The dataset is an unbalanced panel, reflecting differences in listing duration and data availability. After excluding observations with missing key financial variables and firms delisted for non-financial reasons, the final sample includes 561 distressed and 11,226 non-distressed firm-year observations.

Table 2 summarizes financial distress prediction variables, detailing their mean, median, max, min, and standard deviation. These statistics clarify each variable’s central tendency, variability, and distribution, which are key to understanding their impact on prediction models.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics of Variables.

The mean FD value of 0.05 indicates a low average likelihood of financial distress among companies. Variables like return on assets (ROAA), gross profit margin (GP), and operating expense ratio (OE) reflect varying profitability and efficiency levels, shown by their mean and median values. Additionally, examining the maximum and minimum values highlights the range of values covered by each variable, providing insight into potential outliers or extreme observations. The standard deviation values further quantify the dispersion or spread of data points around the mean, indicating the level of variability within each variable.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the study variables. The correlations are low, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a major concern for the subsequent regression analysis.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix of Variables.

Although the pairwise correlation (r = 0.78) between ROAA and TAG looks high, the VIF values (≈2.56 each) show that in the context of the full model—including all other variables—the overlap between ROAA and TAG is not severe.

The absence of strong correlations between variables mitigates the risk of multicollinearity in financial distress prediction models, which suggests that each variable may provide unique information for predicting financial distress independently, without redundancy or collinearity issues.

3.2. Models for Binary Dependent Variables

Within this category of models, the dependent variable is restricted to two outcomes—often represented as a dummy variable indicating a choice between two options, which can take on values of zero or one. Let us consider modeling the probability of observing a value of one as:

where represents a continuous, strictly increasing function mapping real numbers to values between zero and one. The model adheres to the common simplifying assumption that the index specification follows a linear format with parameters, typically denoted as . The selection of function dictates the category of binary model. Consequently:

Two alternative interpretations of this specification are noteworthy, with the binary model frequently justified as a latent variable’s specification. This suggests the presence of an unobserved latent variable, denoted as y, which is presumed to have a linear relationship with the variable x.

The observed dependent variable is influenced by the presence of a random disturbance, denoted as . The determination of the observed dependent variable hinges upon whether the variable surpasses a specific threshold value:

Another interpretation of the binary specification can be viewed as a conditional mean specification. This perspective allows us to express the binary model equivalently as a regression model.

where denotes the residual, which signifies the discrepancy between the binary value and its conditional mean.

Logit, Probit, and Extreme Value are three commonly used models in statistical analysis for binary response data. The Logit model assumes that the latent variable follows a logistic distribution, whereas the Probit model assumes a standard normal distribution for the latent variable. Both Logit and Probit models estimate the probability of an event occurring based on a set of explanatory variables. However, the interpretation of coefficients differs between the two models: Logit coefficients represent changes in log odds, while Probit coefficients represent changes in standard deviations of the latent variable. On the other hand, the Extreme Value model relies on the assumption that the error term follows an extreme value distribution. While Logit and Probit models are parametric and assume specific distributions for the error term, the Extreme Value model is semiparametric, making it more flexible in capturing heterogeneity and unobserved factors affecting the decision-making process. The error terms of the three models are characterized by three distinct distributions:

- [1]

- Logit Model:

The concept derives from the cumulative distribution function associated with the logistic distribution.

- [2]

- Probit Model:

- [3]

- Extreme Value Model:

The methodology relies on the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) for the Type I extreme value distribution, which is characterized by its skewness.

Utilizing three models simultaneously for the same dataset offers several advantages in statistical analysis. Firstly, it provides robustness and sensitivity analysis, enabling the assessment of the consistency of findings across different modeling techniques and potentially identifying areas of uncertainty or model misspecification. Secondly, it facilitates model comparison and selection, allowing to choose the most appropriate model based on performance metrics and goodness-of-fit criteria.

4. Empirical Results Analysis

Employing multiple models concurrently elevates the robustness and credibility of statistical analysis, enabling better-informed decisions and yielding more resilient conclusions from the dataset. This approach ensures a comprehensive examination of the data, alleviating the limitations inherent in individual models and enhancing the validity of the findings.

Table 4 presents the results of a financial distress prediction model, comparing the performance of three different models: Logit, Probit, and Extreme Value. The results indicate that several variables are statistically significant across all three models. The models achieve high accuracies, ranging from 94.29% to 97.05%, suggesting that they perform well in predicting financial distress. The significance of the likelihood ratio statistic and associated p-values, which are all close to zero, indicates that the models significantly outperform a null model. These findings suggest that the chosen set of financial ratios and metrics effectively predict financial distress in the context of the studied dataset, offering profound clarification for risk assessment and management in financial decision-making.

Table 4.

Financial Distress Prediction Model Comparison.

Alongside the prominent variables previously discussed, some coefficients exhibit differing levels of significance across various models. ROAA (Return on Assets After Tax Before Interest) is statistically significant within the Logit and Probit models, yet not in the Extreme Value model. Similarly, GP (Gross Profit Margin) holds significance in the Logit model but not in the other two models. These discrepancies underscore the importance of selecting a suitable modeling method based on the data characteristics and research goals. Despite these differences, the consistently high accuracy rates across all models demonstrate strong predictive capabilities. Furthermore, incorporating year control variables enhances the model’s temporal applicability.

Given the limitations of traditional statistical models in predicting financial distress, constructing a practical Artificial Neural Network (ANN) presents a promising approach. ANNs are well-suited for handling nonlinear relationships and capturing complex patterns within data, which are often present in financial distress prediction scenarios. By leveraging the flexibility and adaptability of ANNs, it can incorporate a wider range of features and capture intricate interactions between variables, ultimately causing improved predictive performance.

5. Deep Neural Network

Artificial intelligence (AI) is crucial in transforming risk governance and management across multiple sectors. According to Binh (2024) [48], artificial neural networks (ANN) exhibit better predictive power than the logit model when it comes to making decisions on corporate social responsibility. With enhanced abilities in data processing, pattern recognition, and predictive analytics, AI helps organizations improve their risk assessment processes, spot emerging risks, and devise proactive strategies for risk mitigation.

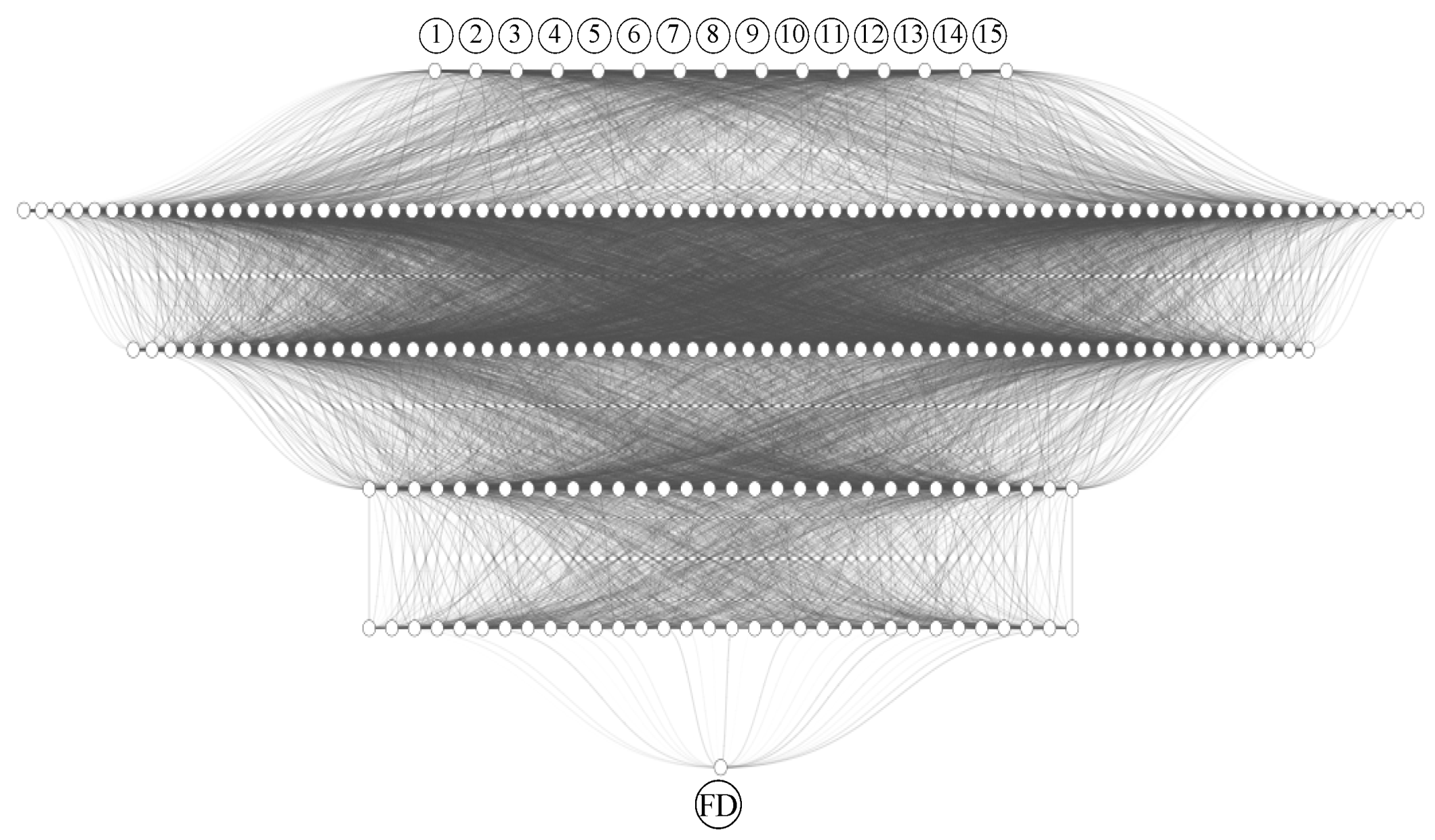

Figure 1 represents a neural network architecture designed for financial distress prediction. The described neural network architecture can be termed a deep feedforward neural network or simply a deep neural network (DNN) designed for a binary classification task. It is specifically tailored for the task of predicting the binary output variable FD based on the input features ROAA, GP, OE, OGP, TAG, IE, ART, IT, CAA, WCD, REA, ORA, DE, and AGP.

Figure 1.

Deep Feedforward Neural Network Architecture for Financial Distress Prediction in Taiwan’s Electronics Industry.

The architecture comprises an input layer with 15 nodes corresponding to the input features, followed by four hidden layers with 80, 64, 32, and 32 neurons, respectively, all utilizing the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function. There is an output layer with a single neuron employing the sigmoid activation function, which is typical for binary classification tasks, as it outputs probabilities ranging from 0 to 1.

The model was trained for 1000 epochs with a batch size of 500, employing a firm-level train/test split (70% of firms for training, 30% for testing) and a 20% validation split within the training set to monitor overfitting. Predicted probabilities were converted to binary distress predictions using a 0.5 threshold, and performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, ROC-AUC, and confusion matrices. This evaluation shows strong performance across all metrics while maintaining minimal misclassifications, indicating that the model generalizes well without overfitting. To further ensure robustness, 5-fold firm-level cross-validation is conducted, which yielded consistent results across folds, confirming that the high accuracy is not an artifact of the train/test split or dataset imbalance.

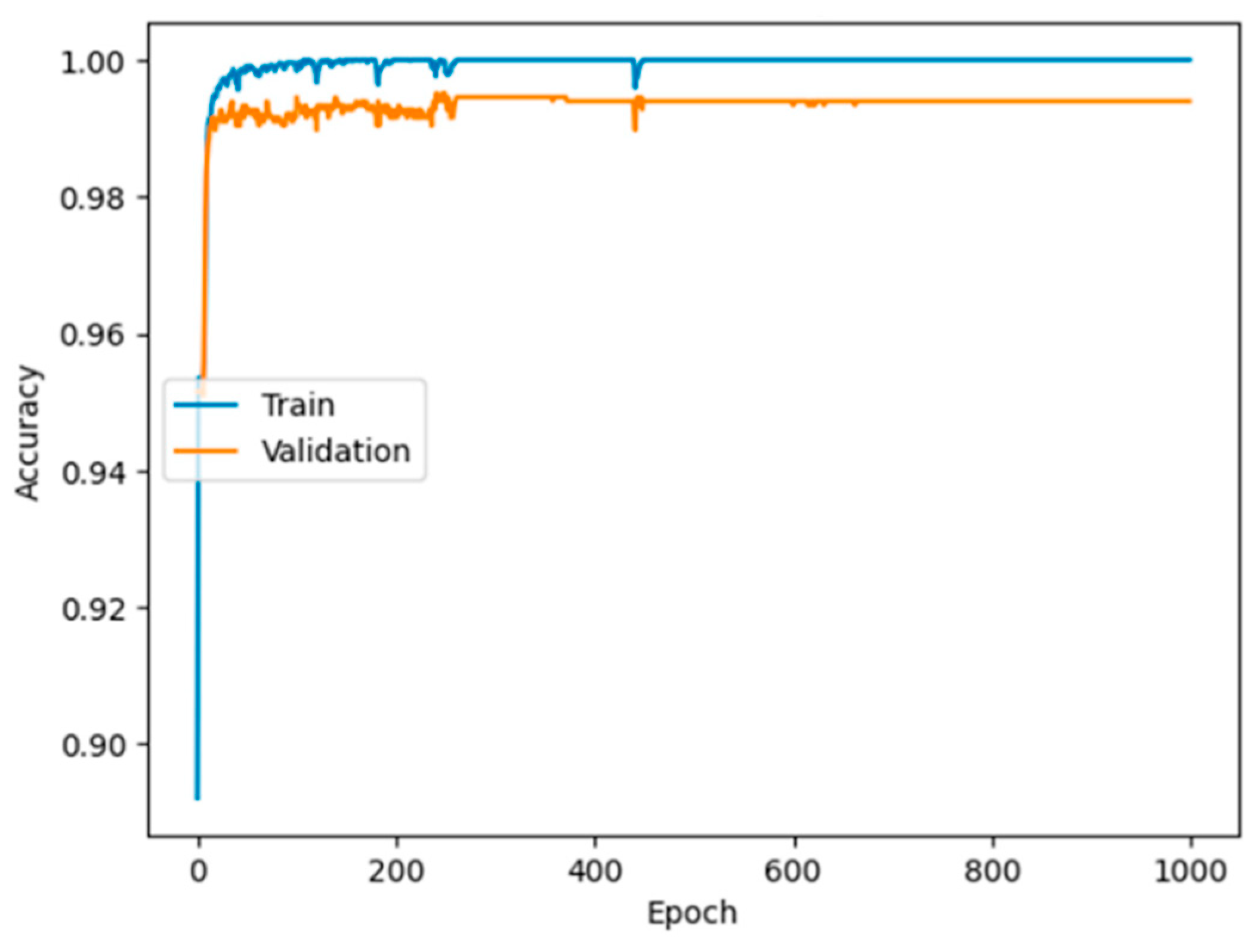

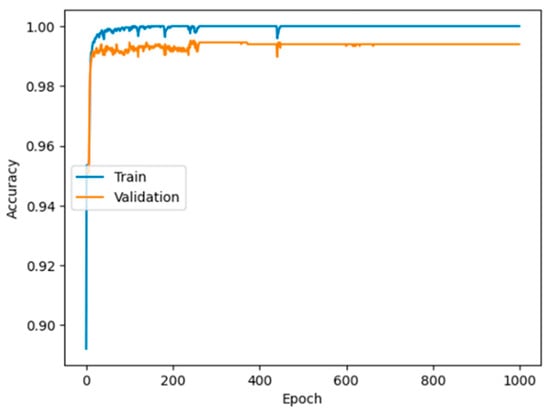

Figure 2 depicts the training progression of an ANN model, showing Accuracy plotted against Epoch number for both training and validation datasets. The model exhibits very fast learning and high performance from the outset, with both training and validation accuracies exceeding 98% within the first 100 epochs. The training accuracy (blue line) quickly approaches 1.00 (or 100% accuracy), whereas the validation accuracy (orange line) stabilizes slightly lower, leveling off near 0.99 (or 99% accuracy). Notably, the training accuracy consistently remains a bit higher and more variable than the validation accuracy after the initial convergence. Despite a minimal generalization gap, where training accuracy slightly surpasses unseen validation performance (the difference being minor), the validation accuracy remains exceptionally high and stable throughout the 1000 epochs. As the validation accuracy does not exhibit a significant decline nor excessive fluctuations over the entire 1000 epochs, the plot affirms that the trained model is highly robust and capable of sustaining its high prediction accuracy on new financial data, indicating it has achieved an optimal learning state for this specific task.

Figure 2.

Accuracy Trends of the Deep Neural Network Throughout Training.

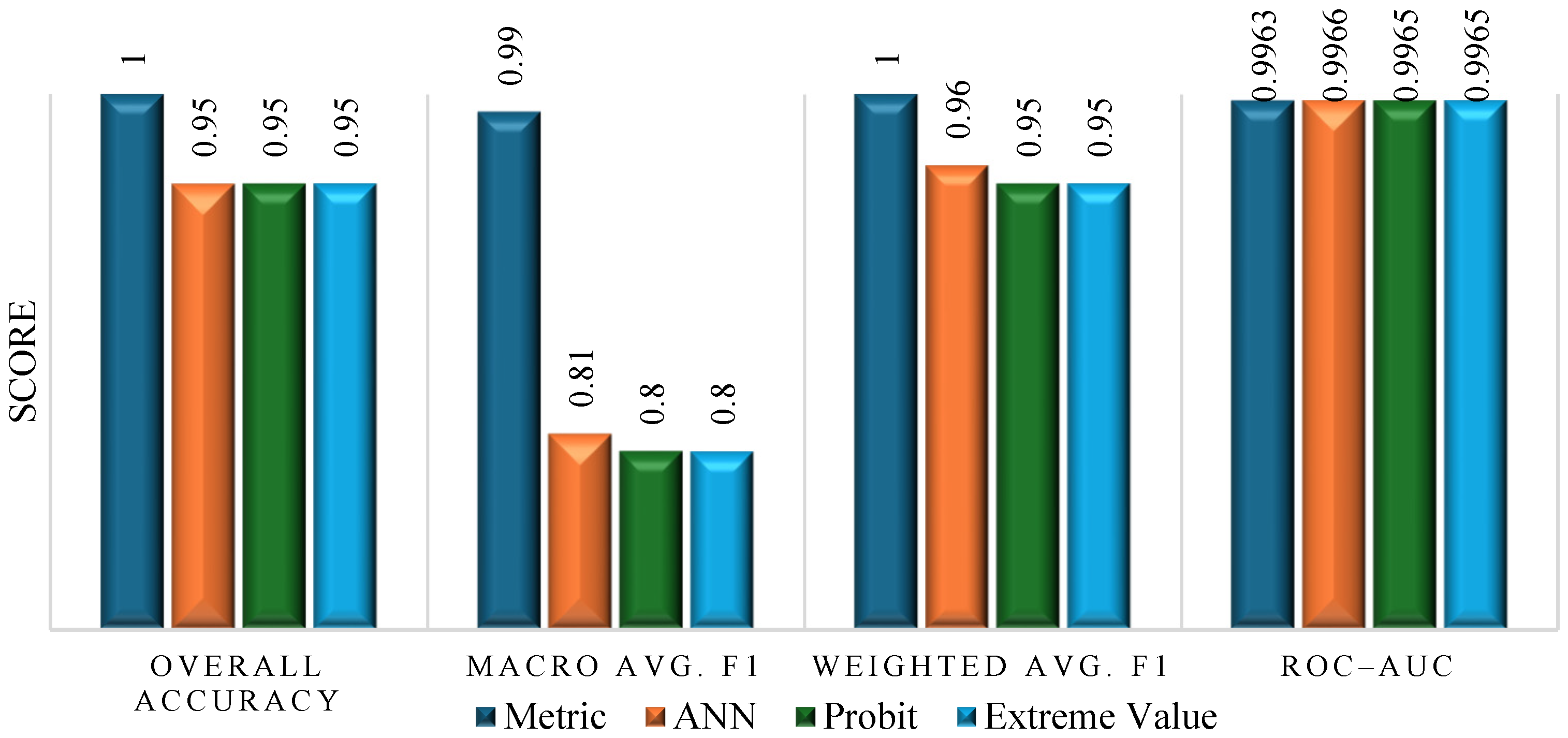

The results presented in Table 5 highlight the superior predictive performance of the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model compared with the traditional Logit, Probit, and Extreme Value models. The performance metrics highlight distinct differences between the ANN and traditional models in handling class imbalance. For the non-distressed class (FD = 0), all models achieve perfect precision (1.00) and high specificity (0.94–0.95 for traditional models, 1.00 for ANN), with F1-scores near 0.97. For the financially distressed class (FD = 1), the ANN exhibits substantially higher precision (0.97) and F1-score (0.96) compared to probit, logit, and extreme value models, which show precision around 0.47–0.49 and F1-scores near 0.64–0.65. Sensitivity for the distressed class is perfect (1.00) for traditional models but slightly lower (0.95) for ANN, reflecting a trade-off favoring precision in ANN’s classification.

Table 5.

Comparison of Prediction Accuracy Across Models.

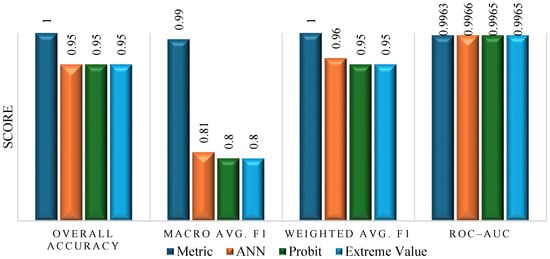

Figure 3 illustrates key differences in classification performance. While all models demonstrate similarly high overall accuracy (ranging from 0.95 to 1), the ANN significantly outperforms traditional models in terms of Macro Average F1-score (0.81 for ANN vs. approximately 0.80 for others), indicating better balanced performance across both classes. The Weighted Average F1-score further confirms this trend, with the ANN achieving 0.96 compared to 0.95 for probit and extreme value models.

Figure 3.

The evaluation metrics across models.

All models show excellent ROC-AUC values above 0.99, signifying strong discrimination ability. Notably, the ANN achieves perfect overall accuracy, Macro F1, and Weighted F1, highlighting its robustness in handling class imbalance while maintaining high predictive power.

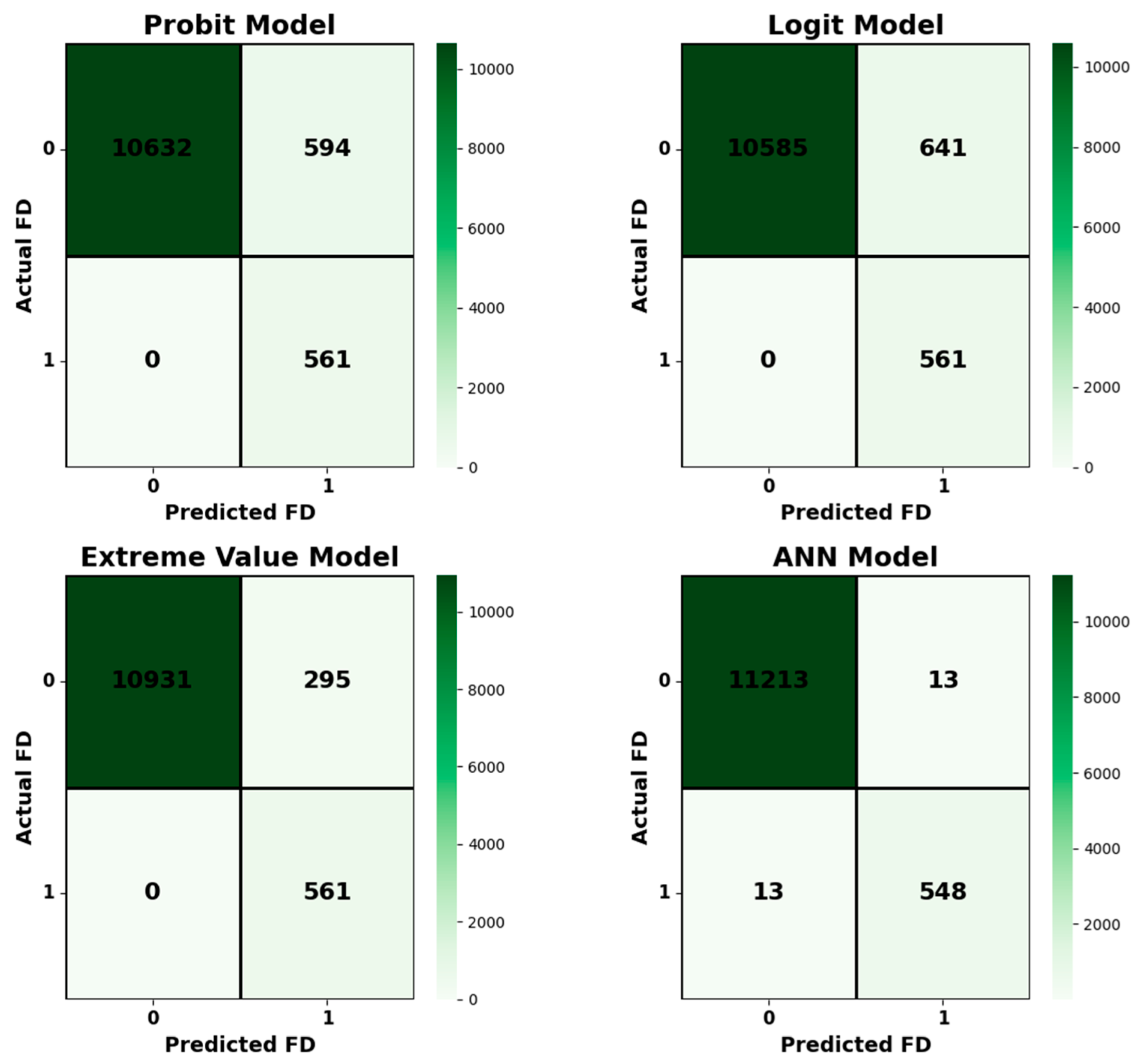

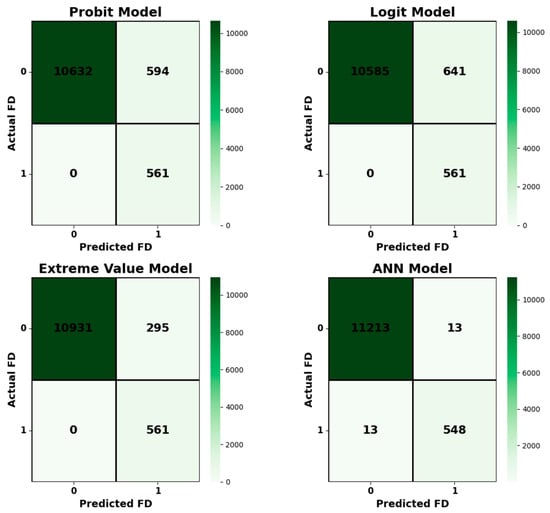

The confusion matrix in Figure 4 illustrates the effectiveness of the binary classification model developed for Financial Distress (FD) Prediction. The comparative analysis of the four models—ANN, Extreme Value, Logit, and Probit—reveals distinct trade-offs in their performance for Financial Distress (FD) prediction, where the total number of actual distressed cases (Actual FD = 1) is 561 across all models. The ANN model demonstrates the best overall balance by achieving the lowest counts for both False Positives (FP = 13) and False Negatives (FN = 13), making it the most accurate model across the entire dataset.

Figure 4.

Financial Distress Prediction Performance across Logit, Probit, Extreme Value, and ANN.

In contrast, Extreme Value, Logit, and Probit Models exhibit a specific strength: they all achieved perfect recall for the positive class (FN = 0), meaning they did not miss a single company that actually went into financial distress. However, this superior recall comes at the cost of increased Type I errors (False Positives), with the Extreme Value Model reporting FP = 295, the Probit Model reporting FP = 594, and the Logit Model reporting the highest FP = 641. Therefore, while the ANN Model is optimal for general accuracy and error minimization, the Extreme Value Model presents the most favorable outcome for risk-averse scenarios by perfectly identifying all distressed entities while incurring the lowest penalty (FP count) among the models with zero False Negatives.

6. Robustness Check of ANN

To assess the robustness of the ANN model to extreme observations, a full sensitivity analysis was conducted by winsorizing all financial ratios at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Prior to winsorization, several predictors exhibited exceptionally large and economically implausible values (ROAA ranged from −127.50 to 12,814.57, GP from −11,777.85 to 100, OGP from −28,098.73 to 99,207.33, and IE from −62,255.74 to 5388.31), clearly reflecting the presence of outliers or highly volatile accounting denominators. After winsorization, these variables were constrained to far narrower and more realistic ranges (ROAA −26.49 to 27.36; OGP −154.80 to 641.78; AC 6.05 to 211.64), resulting in a cleaner and more stable dataset. When the ANN model was re-estimated using the winsorized predictors, overall accuracy remained high at 97%, and the model continued to classify the majority class effectively (precision = 0.98, recall = 0.99). However, sensitivity to Financial Distress (FD = 1) declined, with recall dropping to 0.59 and the F1-score to 0.65, indicating that winsorization removed some extreme-but-informative signals associated with distress cases. The confusion matrix shows that the model correctly identified 103 FD firms but missed 71, while the ROC-AUC of 0.9555 still reflects strong discriminatory capacity. This sensitivity analysis demonstrates that although winsorizing extreme ratios produces well-behaved feature distributions, it modestly reduces the model’s ability to detect distress, highlighting the trade-off between statistical smoothing and the preservation of predictive information.

The neural network model demonstrates strong predictive performance for the binary classification task of identifying Financial Distress (FD) in an imbalanced dataset. By applying class weighting to counteract the scarcity of positive FD cases, the model effectively learns to prioritize detecting the minority class without compromising accuracy on the majority class. The class weighting scheme assigns a weight of 0.525 to FD = 0, the majority class, and a substantially higher weight of 10.5 to FD = 1, the minority class—approximately twenty times greater. This imbalance in weighting ensures that the model strongly penalizes errors on FD = 1 cases, encouraging it to learn patterns associated with the rare but critical distress instances. The results presented in Table 6 show that the model achieves excellent overall performance, reflected in its very high accuracy and strong ROC-AUC score (0.98). Its ability to detect FD = 1 cases is particularly noteworthy: a recall of 0.96 indicates that the model misses very few true distress events, while a precision of 0.82 shows that although some false positives occur, the predictions remain generally reliable.

Table 6.

ANN Predictive Performance with Class-Weighted Training.

The high F1 score of 0.88 for FD = 1 further confirms an effective balance between precision and recall. This balance between sensitivity and specificity ensures the model is well-suited for practical deployment, particularly in scenarios where missing a distress signal carries significant risk. Early stopping and careful scaling contributed to controlling overfitting, as evidenced by stable validation metrics, making the model robust and generalizable to unseen data.

The five-fold cross-validation results in Table 7 demonstrate that the ANN model maintains consistently strong performance across all five folds, confirming its robustness and generalizability. Accuracy remains extremely high, ranging from 0.9915 to 0.9958, indicating that the model reliably classifies both FD and non-FD observations regardless of how the data is split. Precision values fluctuate slightly between folds (0.9079 to 0.9857), reflecting varying levels of false positives across splits, yet the model generally maintains strong reliability when predicting the positive FD class. Recall values also remain high (0.882 to 0.986), showing that the model consistently captures most true Financial Distress cases, with only minor variation depending on sample composition.

Table 7.

Five-fold Cross-validation Metrics.

The F1-scores (0.8955 to 0.9586) demonstrate a stable and well-balanced trade-off between precision and recall across all folds. Importantly, the ROC-AUC scores stay exceptionally high (0.9748 to 0.9997), indicating excellent discriminatory power independent of threshold choice. The cross-validation metrics confirm that the ANN model is not overfitting and performs reliably across different segments of the dataset, strengthening confidence in its predictive robustness for identifying financial distress.

7. The Signal of Financial Distress

In this section, a threshold technique is applied to determine the specific cutoff values that distinguish between financially distressed and non-distressed firms, serving as a crucial step in refining the predictive accuracy of the model. This approach ensures that the model does not rely solely on predicted probabilities but translates them into actionable classifications that can support managerial and financial decision-making. Furthermore, the threshold analysis allows for deeper insight into the model’s discriminative power. In the context of financial distress prediction, selecting an appropriate threshold is particularly critical, as misclassification can have severe consequences, either by causing unnecessary alarm for stable firms or by overlooking early warning signs of potential bankruptcy.

Table 8 and Table 9 examine the dependent variables ROAA and TAG, respectively, using the Bai and Perron (2003) [49] multiple structural break test to identify nonlinear effects on financial distress (FD). Thresholds are determined where scaled and unscaled F-statistics exceed the 1% critical value, with ROAA = 7.03% and TAG = −9.05% representing the most statistically significant breakpoints. Subsample regressions show large coefficients in these regimes. These results highlight nonlinear patterns, where the relationship between the predictors and FD differs markedly above and below the thresholds, emphasizing the economic significance of regime-dependent effects.

Table 8.

Nonlinear Signal of Financial Distress on ROAA.

Table 9.

Nonlinear Signal of Financial Distress on TAG.

Table 8 presents the nonlinear relationship between financial distress and Return on Assets (ROAA), analyzed across the full sample and two distinct subsamples divided by the threshold value of ROAA = 7.03.

The results reveal significant nonlinear effects, suggesting that the impact of financial distress and related financial indicators on firm profitability varies substantially depending on the firm’s performance level. For the full sample, the regression model exhibits strong explanatory power with an R-squared of 0.611 and a highly significant F-statistic (1154.80, p < 0.01), indicating that the included variables collectively explain a substantial portion of ROAA variation. When the sample is divided, the differences become even more pronounced. For firms with ROAA below 7.03, the model captures a strong negative influence of financial distress (FD = −8.168, p < 0.01), implying that financially distressed firms tend to experience significant declines in profitability when operating with lower asset returns. Several variables—such as Operating Efficiency (OE), Operating Gross Profit (OGP), and Accounts Control (AC)—show significant negative coefficients in this subset, reinforcing the idea that inefficiencies and poor operational control exacerbate financial distress in weaker-performing firms. Conversely, for firms with ROAA equal to or above 7.03, the relationship between financial distress and profitability becomes weaker (FD = 0.569, not significant), and the model’s explanatory power dramatically increases (R-squared = 0.996, F-statistic = 85,794.09, p < 0.01), suggesting near-perfect model fit. In this higher-performing group, variables such as Total Assets Growth (TAG), Interest Expenses (IE), and Revenue Efficiency (REA) positively influence ROAA, implying that well-performing firms can better absorb financial shocks and maintain profitability even under financial pressure. The results confirm the nonlinear nature of financial distress effects on profitability, indicating that the negative impact of distress is more severe for financially weaker firms, while stronger firms demonstrate greater resilience due to better efficiency, asset utilization, and revenue-generating capacity.

Table 9 presents the nonlinear relationship between financial distress (FD) and Total Asset Growth (TAG), further examined across the entire dataset and two subsamples divided by the threshold value of TAG = −9.05. The results provide compelling evidence that the effect of financial distress on asset growth is not uniform but varies significantly depending on a firm’s growth stage and financial position. For the full sample, the regression model demonstrates moderate explanatory power, with an R-squared of 0.610 and a statistically significant F-statistic (1148.58, p < 0.10), suggesting that the explanatory variables collectively contribute meaningfully to variations in TAG. The negative coefficient for financial distress (FD = −16.755, p < 0.10) indicates that financially distressed firms tend to experience slower asset growth, consistent with the expectation that distress restricts investment and expansion capacity.

When the sample is split, the relationship becomes more nuanced. For firms with TAG below −9.05 (those experiencing asset shrinkage), the impact of financial distress intensifies substantially (FD = −223.890, p < 0.10), highlighting that firms already undergoing asset decline are disproportionately affected by distress, likely due to liquidity shortages and capital erosion. Several variables, such as Revenue Efficiency (REA = 6.543, p < 0.10) and Operating Return on Assets (ORA = −66.519, p < 0.10), also exhibit large magnitude coefficients, underscoring the instability and volatility of firm performance in this segment. In contrast, for firms with TAG ≥ −9.05, the effect of financial distress becomes positive but statistically weaker (FD = 5.915, not significant), implying that healthier or growing firms are more resilient to distress pressures and may even sustain modest asset growth despite financial challenges. The model fit also improves slightly in this subset (R-squared = 0.621), indicating a stable relationship between profitability, operational efficiency, and asset growth among better-performing firms.

The results highlight a nonlinear and uneven impact of financial distress on the growth of total assets; distress significantly hinders asset growth in declining firms but is less impactful on companies with stable or increasing asset levels. This trend indicates that financial distress worsens existing vulnerabilities in struggling companies, whereas financially stable firms are better equipped to handle shocks and keep growing. This underscores the significance of maintaining firm health and effective asset management to mitigate the negative effects of financial distress.

The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) method clearly demonstrates superior predictive abilities compared to logistic regression, probit, and extreme value models when it comes to forecasting financial distress, achieving a remarkable accuracy of 98%. Two strong indicators of financial distress are identified: Return on Assets (ROAA) with a threshold of 7.03 and Total Asset Growth (TAG) with a threshold of −9.05. Additionally, the nonlinear effects of financial distress on ROAA and TAG are assessed, uncovering complex relationships that emphasize the significance of contextual factors in financial analysis and decision-making processes.

8. Conclusions

This study has revealed how effective analytical techniques, especially Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), are at predicting financial distress in the Taiwan electronics industry. When comparing traditional statistical models like Logit, Probit, and Extreme Value to the ANN model, ANN demonstrated superior accuracy, achieving an impressive 98% accuracy rate. Additionally, two strong indicators of financial distress, Return on Assets and Total Asset Growth, with their threshold values, have been identified. These findings provide meaningful insights into risk assessment and management in financial decision-making.

This study emphasizes the importance of considering context and nonlinear relations in predicting financial distress. Utilizing ANN techniques allows for capturing the complexities inherent in financial data, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy. This research contributes to the ongoing efforts to anticipate financial distress by providing stakeholders and managers with valuable insights through detailed empirical analysis and validation. It also stresses the importance of implementing sound financial management practices to mitigate the risk of financial distress. By maintaining robust financial health and adopting proactive risk management strategies, companies can bolster their resilience and sustainability in the face of economic uncertainties.

Looking ahead, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, such as ANNs, has significant potential to improve the accuracy and reliability of financial distress prediction models. As AI continues to develop, its role in changing risk management practices will become more essential, enabling organizations to navigate today’s complex business landscape confidently.

Managers and financial institutions can adopt the ANN-based early warning system as part of their financial monitoring frameworks. Regular evaluation of key financial ratios—especially ROAA and TAG—against the identified thresholds can help identify at-risk firms early. The model can be integrated with enterprise resource planning (ERP) or risk management software to provide real-time alerts, allowing timely corrective actions such as liquidity adjustments, cost optimization, or strategic investment decisions. For investors, combining the model’s output with qualitative assessments can enhance portfolio risk management. Training staff on interpreting ANN predictions and validating model output periodically will ensure reliability and promote effective use of AI-driven insights in practical decision-making.

However, the study has practical limitations. The analysis is confined to the Taiwan electronics sector, limiting generalizability to other industries or countries. It relies solely on financial ratios, excluding market, macroeconomic, or textual data that may enhance predictive power. The real-world implementation may require integrating the model into existing risk management systems, which can be resource-intensive and require specialized expertise.

Author Contributions

Professional insights and expert guidance, L.-W.Y.; methodology, N.T.T.B.; software, N.T.T.B.; formal analysis, N.T.T.B.; data curation, J.M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.Y.; writing—review and editing, N.T.T.B.; visualization, N.T.T.B.; supervision, N.T.T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study were obtained from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) and are governed by TEJ’s licensing, usage, and privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Altman, E.I. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J. Financ. 1968, 23, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.C. Risk Management and Financial Institutions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Serrasqueiro, S.; Caetano, A. Corporate resilience and sustainability: A multidimensional framework. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13408–13436. [Google Scholar]

- Botosan, A.; Plumlee, M.T. Corporate governance and shareholder value creation: A meta-analysis. Manag. Financ. 2002, 28, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.J.; Shrivastava, P.; Shankar, V. Business resilience: Building capacity to overcome adversity. Bus. Horiz. 2008, 51, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlson, J.A. Financial ratios and the probabilistic prediction of bankruptcy. Financ. Anal. J. 1980, 36, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmijewski, M.E. Methodology of financial failure prediction models. J. Account. Public Policy 1984, 3, 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Taffler, R.J. Application of a financial instability model in the UK industrial sector. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1983, 146, 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Livnat, J.; Zarowin, P.A. Using financial ratios to predict firm failure. In Handbook of Business Analytics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 349–375. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, P.E.; Elgers, P.T. Credit Risk Analysis: Applications and Extensions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Li, H.; Fujita, H.; Fu, B.; Ai, W. Class-imbalanced dynamic financial distress prediction based on Adaboost-SVM ensemble combined with SMOTE and time weighting. Inf. Fusion 2020, 54, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, A.; Khan, A.M.; Baharudin, K.B. Long short-term memory (LSTM) based deep learning model for financial distress prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 122, 256–268. [Google Scholar]

- Matin, R.; Hansen, C.; Hansen, C.; Mølgaard, P. Predicting distresses using deep learning of text segments in annual reports. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 132, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, F.; Tian, S.; Lee, C.; Ma, L. Deep learning models for bankruptcy prediction using textual disclosures. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 274, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, G.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, F.; Yang, S.; Lu, T. Leveraging multisource heterogeneous data for financial risk prediction: A novel hybrid-strategy-based self-adaptive method. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 1949–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.E.; Beaver, W.H.; Thomas, W.B. Economic rationale for the study of accounting and auditing. Account. Horiz. 2001, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, R.G. Modeling cash flows from operations. Account. Horiz. 1996, 10, 219–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, T.B. Going-Concern Accounting and Audit Judgment; American Accounting Association: Lakewood Ranch, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, G.R.; Palepu, K.G.; Srinivasan, R. An empirical analysis of accrual adjustments and conservatism in the cash flow from operations. Account. Rev. 1990, 65, 390–412. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, S.S.; Ilias, M.R.; Nayan, A.; Abdul Rahim, A.H.; Morat, B.N. Logistic regression model for evaluating performance of construction, technology and property-based companies in Malaysia. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 39, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsenne, M.; Ismail, T.; Taqi, M.; Hanifah, I.A. Financial distress predictions with Altman, Springate, Zmijewski, Taffler and Grover models. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2024, 13, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.J.; Zhu, H. Predicting financial distress using machine learning approaches: Evidence from China. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2024, 20, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, M.; Liu, X. A two-stage case-based reasoning driven classification paradigm for financial distress prediction with missing and imbalanced data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Z.; Ding, Y. Predicting financial distress using current reports: A novel deep learning method based on user-response-guided attention. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 179, 114176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, W.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Abedin, M.Z. Predicting financial distress using multimodal data: An attentive and regularized deep learning method. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Sahut, J.-M. ESG performance and financial distress prediction of energy enterprises. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 65, 105546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, J.A.; Newbold, P.; Whitford, D.T. Classifying bankrupt firms with funds flow components. J. Account. Res. 1985, 23, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Lawson, G.H. Cash Flow Reporting and Financial Distress Models: Testing of Hypotheses. Financ. Manag. 1989, 18, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.I.; Narayanan, P. An international survey of business failure classification models. Financ. Mark. Inst. Instrum. 1997, 6, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitou, A.; Neophytou, E.; Charalambous, C. Predicting corporate failure: Empirical evidence for the UK. Eur. Account. Rev. 2004, 13, 465–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, J.; Ming, J.; Watts, S. Bankruptcy classification errors in the 1980s: An empirical analysis of Altman’s and Ohlson’s models. Rev. Account. Stud. 1996, 1, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, J.S.; Ingram, R.W. Tests of the generalizability of Altman’s bankruptcy prediction model. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.P.; Yen, M.F. A new perspective of performance comparison among machine learning algorithms for financial distress prediction. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 83, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Jones, S. Corporate distress prediction in China: A machine learning approach. Account. Financ. 2018, 58, 1063–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, C.; Li, Y. Improving financial distress prediction using financial network-based information and GA-based gradient boosting method. Comput. Econ. 2019, 53, 851–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, I.; Ayadi, R.; Guesmi, K.; Mkaouar, F. A new approach to deal with variable selection in neural networks: An application to bankruptcy prediction. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 313, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, F.; Altman, E. Predicting financial distress in Latin American companies: A comparative analysis of logistic regression and random forest models. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2024, 72, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Guo, J.; Li, L.-F. Machine learning model based on non-convex penalized huberized-SVM. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Impact of an improved random forest-based financial management model on the effectiveness of corporate sustainability decisions. Syst. Soft Comput. 2024, 6, 200102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lu, P.; Cao, Y.; Xu, W. Research on the innovation path of corporate financial management based on improved Adaboost regression algorithm and analysis of management effectiveness. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, C. Diagnosis with incomplete multi-view data: A variational deep financial distress prediction method. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 201, 123269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kuang, X.; Guo, J. LiFoL: An efficient framework for financial distress prediction in high-dimensional unbalanced scenario. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 2784–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febbianti, Y.; Irfan, A.; Liyas, J.N.; Novita, W.; Asis, A.; Rahmi, F. Predicting financial distress of public and non-public construction sub-sector companies. Corp. Gov. Organ. Behav. Rev. 2024, 8, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, T.L.; Kappes, J.C.; Price, C.P. Project and Cost-Benefit Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, E.I. Corporate Financial Distress and Bankruptcy: Predict and Avoid Bankruptcy, Analyze and Invest in Distressed Debt; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, D.; Thabet, M. Debt Maturity Structure and Financial Distress: Evidence from Emerging Markets. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2020, 71, 101583. [Google Scholar]

- Grünewald, M.; Lochmüller, C.; Schalast, C. Transformation of Corporate Finance: Cost of Capital, Market Efficiency, and Agency Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Binh, N.T.T. An application of artificial neural networks in corporate social responsibility decision making. Intell. Syst. Account. Financ. Manag. 2024, 31, e1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Perron, P. Critical values for multiple structural change tests. Econ. J. 2003, 6, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.