Abstract

The European Union’s enhanced greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets for 2030 make the large-scale deployment of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies essential to achieve deep decarbonization goals. Within this context, this study aims to advance CCS research by developing and testing a pilot-scale system that integrates gasification for syngas and power production with CO2 absorption and solvent regeneration. The work focuses on improving and validating the operability of a pilot plant section designed for CO2 capture, capable of processing up to 40 kg CO2 per day through a 6 m absorber and stripper column. Experimental campaigns were carried out using different amine-based absorbents under varied operating conditions and liquid-to-gas (L/G) ratios to evaluate capture efficiency, stability, and regeneration performance. The physical properties of regenerated and CO2-saturated solvents (density, viscosity, pH, and CO2 loading) were analyzed as potential indicators for monitoring solvent absorption capacity. In parallel, a process simulation and optimization study was developed in Aspen Plus, implementing a split-flow configuration to enhance energy efficiency. The combined experimental and modeling results provide insights into the optimization of solvent-based CO2 capture processes at pilot scale, supporting the development of next-generation capture systems for low-carbon energy applications.

1. Introduction

On 11 December 2019, the European Commission proposed the European Green Deal, an ambitious political initiative focused on turning the European Union into a modern, resource-efficient, and competitive economy, with the goal of reaching net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, where CO2 represents approximately three-quarters of total GHGs, while promoting economic growth decoupled from resource use and ensuring that no person or place is left behind. To make the goal of climate neutrality by 2050 legally binding, the Commission introduced the European Climate Law on 14 July 2021, comprising thirteen legislative proposals collectively known as “Fit for 55,” which set an interim target of reducing net GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 [1]. Within this framework, the Net-Zero Industry Act, an integral component of the Green Deal Industrial Plan, aims to foster investment in manufacturing capabilities essential for achieving the European Union (EU)’s climate neutrality objectives. The purpose of this legislation is to reinforce the competitiveness and resilience of the EU’s net-zero technology industry, forming a fundamental pillar in the development of a sustainable, affordable, and secure clean energy system.

Among the technologies recognized under this act are carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies [2], which, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), are indispensable for meeting the Paris Agreement targets of limiting the global temperature rise to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, requiring CCS and Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU) technologies to mitigate nearly 12% of cumulative global CO2 emissions by 2050 [3].

CCS can be applied to various industrial facilities such as cement and steel plants, as well as power generation units, and is particularly vital for hard-to-abate sectors where process emissions cannot be fully addressed through electrification. For instance, in cement production, CO2 is emitted both from fuel combustion and from the calcination of carbonates during clinker formation, accounting for nearly two-thirds of total direct emissions. Therefore, technologies like CCUS are crucial for capturing, storing, and utilizing CO2 that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere. Among capture methods, post-combustion capture is assumed the most mature and readily integrable into existing industrial systems; however, it poses challenges due to the low CO2 concentration and pressure in flue gases [2], leading to high capital and operational costs.

Aqueous amine-based absorbents remain the state-of-the-art solution for post-combustion capture, with monoethanolamine (MEA) being the most widely used solvent owing to its high reactivity and established industrial performance [4,5,6]. Despite its advantages, MEA presents drawbacks including high solvent regeneration energy, corrosion, volatility, and thermal and oxidative degradation [7]. To address these issues, alternative amines such as methyldiethanolamine (MDEA) and 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP) have been explored for their favorable thermodynamic properties and lower regeneration energy requirements [8]. AMP, in particular, exhibits reduced corrosiveness and energy consumption during regeneration compared to MEA, making it attractive for modern gas treatment applications. Another promising strategy involves blending MEA with other amines to create mixed absorbents that combine the fast kinetics of primary amines with the high capacity and lower regeneration energy of tertiary or sterically hindered amines [8].

Conventional amine-based systems, while effective, are limited by the energy-intensive regeneration process, prompting extensive research into novel absorbent types such as catalyst-aided, biphasic, non-aqueous, and blended amine systems.

Catalyst-aided amines incorporate materials like metal oxide derivatives, functionalized molecular sieves, TiO(OH)2 nanocatalysts, ZrO2, ZnO, and Ag2O–Ag2CO3 to enhance carbamate decomposition, potentially reducing regeneration energy by up to 60% [9,10,11].

Biphasic absorbents, capable of separating into CO2-rich and CO2-lean phases upon CO2 absorption or temperature change, minimize regeneration energy to as low as 1.81–2.7 GJ/t(CO2) compared to the 4.0 GJ/t(CO2) of conventional 5 M MEA [12,13,14,15].

Non-aqueous amines, using organic solvents such as N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, ethylene glycol, and glycol ethers, further lower energy consumption by replacing water, though they suffer from higher viscosity [16,17,18,19].

Blended amine systems, combining fast-reacting amines like MEA or DEA with higher-capacity amines like MDEA or AMP, leverage synergistic effects to achieve high absorption rates with reduced regeneration energy [20,21,22]. For example, MEA–MDEA blends are commonly employed in industrial gas treatment, balancing reaction rate, energy efficiency, and stability, while DEA–AMP mixtures optimize absorption performance and reduce solvent degradation.

Beyond solvent innovation, process optimization techniques such as split-amine or split-flow configurations have demonstrated the potential to enhance energy recovery. In these systems, the regenerated amine from the stripper is divided into lean and semi-lean streams, with the latter reintroduced mid-column to provide intercooling, enabling higher CO2 loading (≈0.503 mol CO2/mol MEA) and improved heat recovery, thereby lowering total energy consumption [23]. Collectively, these developments in solvent formulation and process design represent crucial steps toward more energy-efficient and economically viable CO2 capture systems, directly supporting the realization of the European Green Deal’s climate neutrality goals.

Amine Chemistry

The definition of the reaction scheme is fundamental for accurately describing the CO2–MEA–H2O system. Several reaction schemes have been reported in the literature [24,25,26], differing mainly in whether all reactions are treated as equilibria or whether certain reactions are modeled with kinetic limitations.

Since chemical reactions occur exclusively in the liquid phase, the processes of CO2 absorption and desorption involve a sequence of interrelated phenomena, including water division, CO2 hydrolysis, bicarbonate dissociation, carbamate hydrolysis, and MEA dissociation. In aqueous solutions, MEA and carbonate species dissociate into ions, leading to a network of ionic equilibria that collectively define the thermodynamic and kinetic behavior of the electrolyte system. These reactions can be expressed as follows:

As reported in the literature, reactions involving CO2 hydrolysis exhibit kinetic constraints and therefore cannot be rigorously modeled as purely equilibrium processes [27]. For this reason, the reaction scheme adopted in this work incorporates both equilibrium and kinetic reactions to represent the system accurately [28]. Detailed assumptions and implementation procedures for the reaction set in the Aspen Plus model are presented in the following sections.

When amine blends are employed, the reaction mechanism becomes more complex and can be summarized by the following equations:

In Equation (6), the fast-reacting amine (Am1), typically a primary or secondary amine, reacts rapidly with CO2 to form a carbamate. Equation (7) represents the slower pathway characteristic of tertiary or sterically hindered amines (Am2), where bicarbonate formation predominates. Equation (8) illustrates the behavior of an amine blend, in which Am2 acts primarily as a proton acceptor, enhancing the overall absorption process. The advantage of employing blended amines lies in the complementary roles of the two components: Am1 provides rapid CO2 capture through carbamate formation, while Am2 stabilizes the solution by accepting protons and reducing energy demand during solvent regeneration.

Compared with single-amine systems, amine blends offer several advantages [8], including improved thermodynamic efficiency, reduced solvent degradation and corrosion, and drop energy requirements for regeneration. The high regeneration cost of MEA-based solvents, typically ranging between 3.8 and 4.2 GJ/t(CO2) due to the strong stability of carbamate species [15,29], underscores the need for such optimized formulations.

The evaluation of CO2 capture performance in pilot and demonstration-scale facilities is essential to assess operational strategies, such as start-up, steady-state, and shutdown behavior, as well as process flexibility, reliability, and control. These studies provide valuable performance data for scaling up the technology and identifying potential technical bottlenecks. In this context, Italian Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA), in collaboration with Sotacarbo, has undertaken extensive experimental activities at its pilot facilities to test CO2 absorption and regeneration processes. The pilot plant includes both absorption and regeneration units that are integrated into a gasification system with gas cleaning equipment and an internal combustion engine. This setup makes it possible to test different solvents and gas mixtures under realistic operating conditions.

This paper presents an overview of the experimental setup and preliminary results obtained during initial tests using monoethanolamine (MEA) as the solvent. The objectives of the experimental campaign are to evaluate the operational behavior and performance of the CO2 capture pilot plant, verify the functionality of all system components, and enhance understanding of plant dynamics under different operational phases. Given that temperature, pressure, and solvent pH significantly affect amine–CO2 reactions [8], the experimental study includes measurements of key parameters such as temperature, pressure, pH, density, and viscosity. To better understand CO2 absorption in amine blends, this study examines how blend composition affects key physical and chemical properties, such as density, viscosity, absorption rate, and CO2 loading, in concentrated mixtures of MEA combined with tertiary or sterically hindered amines. The novelty of this research lies in the use of a large-scale pilot plant and the validation of experimental data through detailed Aspen Plus simulations. In particular, the study emphasizes the analysis of experimentally derived parameters such as density, viscosity, and pH, which are validated through simulation results, providing a robust framework for understanding the performance of blended amine systems in CO2 capture applications.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental tests were conducted in a pilot unit comprising absorption and regeneration columns, integrated into the Sotacarbo experimental platform but capable of independent operation using gas cylinders to emulate the CO2 feed mixture. The Sotacarbo pilot platform was developed to test various plant configurations under a wide range of operating conditions; consequently, it was designed and constructed with a highly flexible and straightforward layout. The pilot facility uses an updraft, air-blown fixed-bed gasifier with a capacity of 0.84 t/d, suitable for processing both coal and biomass. A gas cleaning section and an internal combustion engine are incorporated into the system.

The pilot plant includes a complete syngas treatment line designed to produce hydrogen for the power generation section. Since 2008, the flexible Sotacarbo platform has undergone more than 6000 h of experimental testing, allowing for the optimization of gasification and syngas treatment processes across different operating conditions and feedstocks. Additional technical details can be found in previously published work [30].

The pilot syngas treatment line and the CO2 feed mixture line feature a flexible configuration, enabling the testing and characterization of a variety of treatment processes and materials. The system allows for testing solvents, sorbents, and catalysts for applications such as syngas desulfurization, water–gas shift reactions, CO2 capture, and hydrogen purification. These characteristics allow Sotacarbo to offer technical support to companies for testing different fuels, materials, and processes.

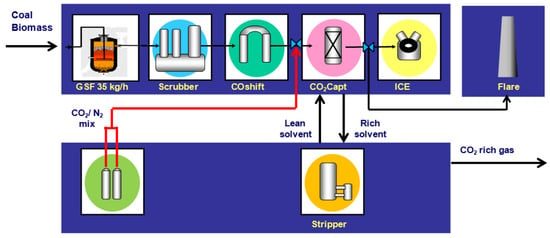

Figure 1 presents an overview of the Sotacarbo pilot plant platform, including the CO2 absorption and regeneration section. The section, capable of separating up to 14 t/year of CO2, is integrated with the other sections of the plant and can be supplied either with syngas from the gasifier or with flue gas from the cylinders, thus emulating different compositions typical of the combustion gas.

Figure 1.

Sotacarbo pilot plant platform layout.

2.1. Absorption and Regeneration Experimental Section

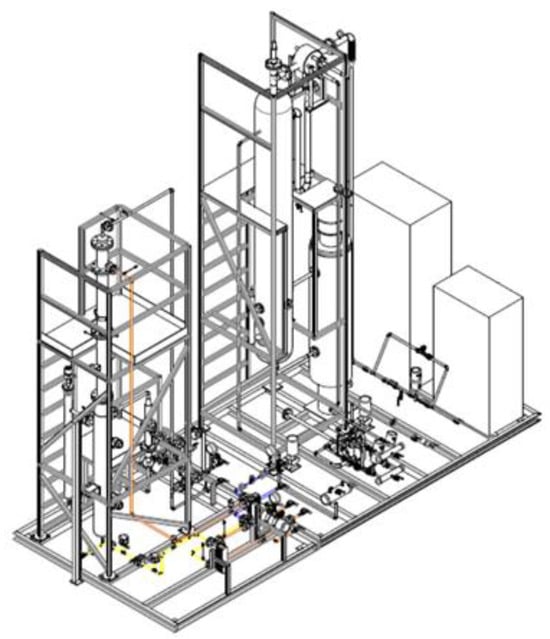

The present work reports the main experimental results regarding tests carried out in the CO2 absorption/regeneration section. The section is composed of a packed column absorber, a packed column stripper, heat exchangers, pumps, and all the auxiliaries. Carbon dioxide absorption takes place into the packed column (Figure 2 and Figure 3), in which flue gas is injected through a diffuser and reacts, at about 30 °C and atmospheric pressure, using amine-based solvents. The absorber consists of a cylindrical column characterized by an overall height of about 6320 mm and an inner diameter of 107 mm.

Figure 2.

CO2 absorption.

Figure 3.

Stripper columns.

The tower packing is divided into five packed beds, for a total height of the inert mass of 3150 mm. This creates a large internal surface area within the column, allowing more extensive interaction between the liquid and the gas and increasing the effective contact time between them.

Before entering the absorption column, the inlet liquid passes through two heat exchangers that regulate process conditions under varying operating parameters, preheating the rich absorbent exiting the column and cooling the lean absorbent before recirculation. The conditioned liquid is then distributed uniformly over the top of the column packing via a distributor, ensuring even wetting of the packing surfaces. The CO2-rich gas enters the distribution space below the packing and flows upward through the packing material, countercurrent to the descending liquid stream.

During the reported experimental runs, the absorption column operated at a pressure of 300 mbar (g). The system, however, is designed to function at pressures up to 10 bar (g), with only minor plant modifications required.

The rich amine solution is subsequently pumped into the stripper column, where absorbed CO2 is released. The stripper, capable of operating in both batch and continuous modes, is equipped with an electric reboiler (14 kWe, working between 110 and 150 °C), a condenser, a mist separator to remove residual water, and solvent vapors from the CO2 gas.

After regeneration, the lean solution is cooled and recycled back to the absorption column, thereby completing the amine loop. Two dedicated heat exchangers are used to preheat the rich solvent and cool the regenerated lean solvent, ensuring stable operation across a range of process conditions. The CO2 absorption performance of the amine solutions is evaluated by continuously monitoring the temperatures of the liquid and gas streams.

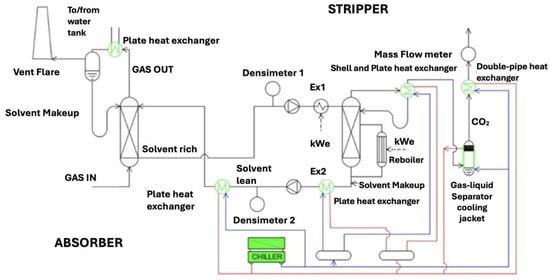

Figure 4 shows the CO2 capture section layout, which is a classical absorption scheme including an additional tank to remove solvent entrained in the gas stream.

Figure 4.

Simplified scheme of the absorption and regeneration section.

2.2. Sampling and Analysis System

The pilot plant is equipped with an integrated control and sampling system that continuously monitors key operating parameters such as pressure, temperature, and flow rates, and supports the evaluation of overall process performance.

Plant operation is managed by an automated control system that regulates and adjusts the main process variables while controlling valves and auxiliary equipment. The pressure drop across each reactor is determined by using pressure sensors installed at the top and bottom of both units. Furthermore, the liquid hold-up in the stripper column is determined using a capacitive level sensor.

A real-time multi-module industrial analyzer, together with a portable gas chromatograph, is dedicated to the continuous monitoring of syngas and flue gas composition. The first analyzer delivers fast online quantification of H2, CO, CO2, CH4, H2S, and O2 concentrations. The micro-GC periodically replicates these measurements, providing higher accuracy and additional information on the concentrations of N2, COS, C2H6, and C3H8.

Given that precise knowledge of absorbent properties is essential for maintaining optimal process control and performance, an initial characterization of the solvent was carried out. Parameters such as density, viscosity, pH, temperature, and CO2 loading were measured to define the main physical and chemical properties of the absorbent. The relationship between density and CO2 loading (moles of CO2 per mole of amine) was also investigated. At fixed amine concentration and temperature, the density of the solution is determined exclusively by the quantity of dissolved CO2 [8]; therefore, CO2 loading can be estimated from changes in solution density. Two online densitometers, positioned before and after the stripper, provide continuous measurement of the liquid density.

Density and viscosity were measured using an Anton Paar DMA-38 (Anton Paar Group AG, Graz, Austria) and AMVn viscometer (Anton Paar Group AG, Graz, Austria), while absorbent samples collected before and after the regeneration column were analyzed in the on-site laboratory. The characterization of the liquid samples is based on the measurements of pH, density, viscosity, and CO2 loading.

The CO2 loading of the amine solutions was determined through a titration method based on the precipitation of BaCO3. This procedure involves reacting the sample with a mixture of BaCl2 and standard NaOH, followed by titration of the excess NaOH with HCl. The method was applied to evaluate the CO2 loading in both the rich solution (from the absorber bottom) and the lean solution (from the stripper bottom).

CO2 loading in this experimental work is defined by the following Equation (9):

3. Experimental Procedures and Results

Multiple tests were carried out, and the key parameters and results of the entire absorption/regeneration process are presented in this paper. Initially, a 5 M monoethanolamine (MEA, 30% w/w) solution was employed as a benchmark to explore all aspects of the process and acquire practical experience.

Subsequently, various tests were carried out using MEA-type amine, AMP-type amine, and blend solutions of MEA and AMP amine.

Below, the interactions occurring in aqueous AMP-CO2 systems are reported in Equations (10) and (11). These interactions are similar to the one reported in Equations (1), (3) and (4) for the MEA-CO2 systems.

A simulated flue gas, consisting of 15% CO2 by volume and the remainder N2, has been fed to the absorption and desorption section.

Table 1 presents the operating conditions for the tests conducted with simulated flue gas. The gas flow rate supplied to the absorption section ranged from 11 to 22 kg/h, while the liquid flow rate from the stripper varied between 85 and 90 kg/h.

Table 1.

Absorber and stripper main operational parameters.

3.1. Results

In the following section, experimental results coming from experimental tests using MEA 5 M and AMP and MEA blending as solvent have been reported.

3.1.1. MEA 5 M

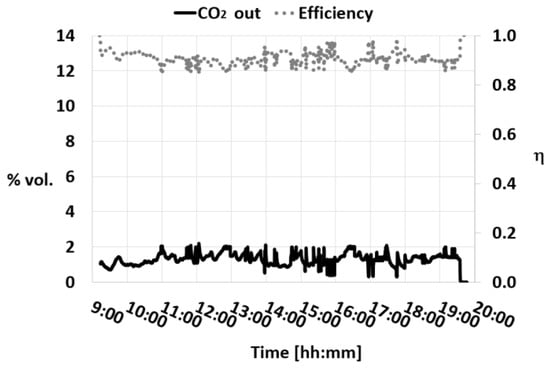

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the CO2 concentration during a test in which the absorption column is fed with a 22 kg/h gas stream (15 vol% CO2 in N2) from cylinders and a solvent consisting of 5 M MEA amine.

Figure 5.

CO2 concentration and efficiency trend during a test with MEA 5 M L/G = 3.9 Pall Rings.

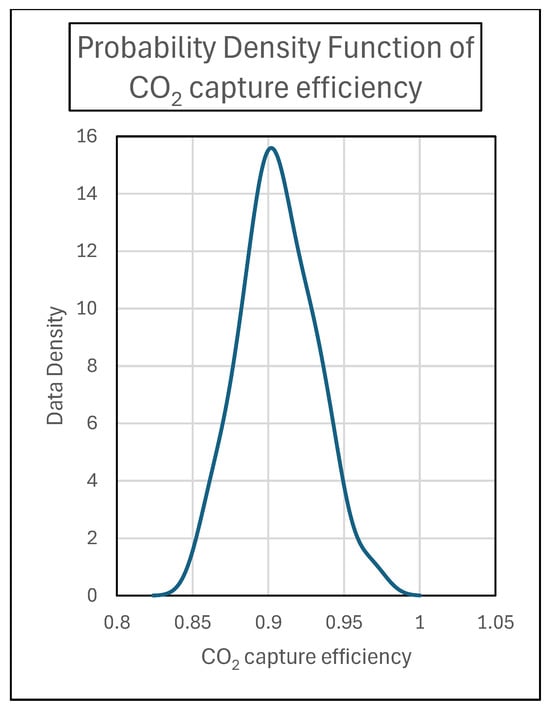

A liquid-to-gas ratio (L/G) of 3.9 was applied, which is the value required to achieve an absorption efficiency of 0.9 with this configuration. Pall Rings as absorber packing materials have been used. The same graph shows the trend of the CO2 capture efficiency (η) over time. In Figure 6, a statistical analysis of the CO2 capture efficiency data collected from the pilot plant is reported.

Figure 6.

CO2 capture efficiency data density.

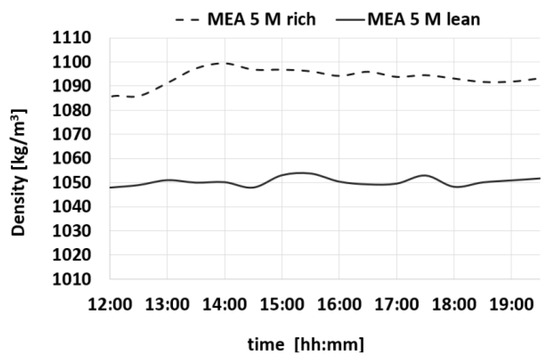

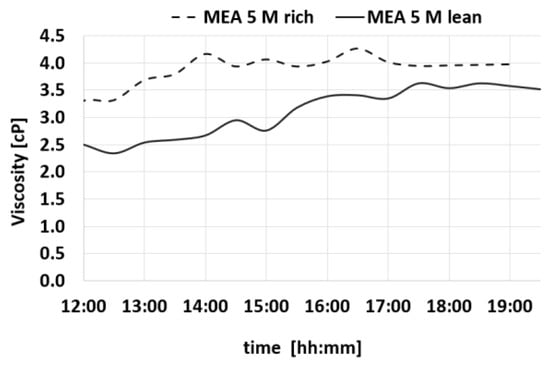

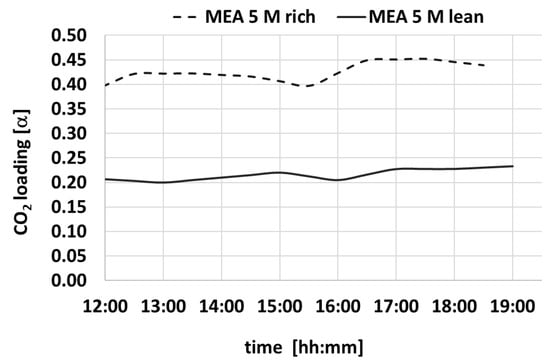

In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the absorption behavior of CO2 in amine mixtures, the data provided in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 offer insights into the temporal evolution of key physical properties, such as density, viscosity, pH, and CO2 loading. Specifically, Figure 6 presents the density trends observed in both the MEA 5 M-rich and MEA 5 M-lean cases over the course of the experimental testing period, revealing a consistent and stable trend towards a steady state. This detailed analysis sheds light on how these physical properties change and influence one another during the absorption of CO2 in amine mixtures providing valuable information.

Figure 7.

Trends of density for MEA-rich and MEA-lean during a test.

Figure 8.

Trends of viscosity for MEA-rich and MEA-lean during a test.

Figure 9.

Variation over time of CO2 loading for MEA-rich and MEA-lean during a test.

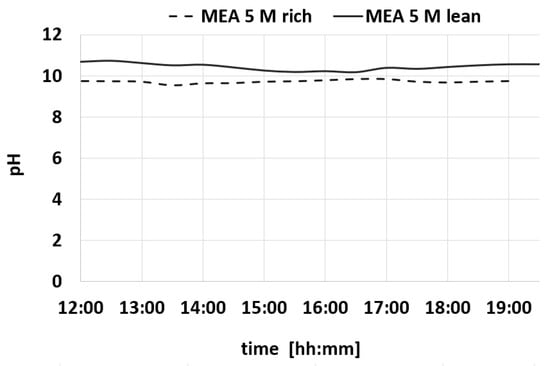

Figure 10.

Variation over time of pH for MEA-rich and MEA-lean during a test.

Also, the Δα values show a constant trend within time. Table 2 summarizes the average values of the measures of density, CO2 loading, viscosity, and pH.

Table 2.

Experimental test results MEA 5 M lean and rich properties.

The characterization study carried out on samples MEA-rich and MEA-lean solutions highlights a significant correlation between pH values and CO2 loading levels.

Specifically, the study shows that increasing CO2 loading is consistently associated with a decrease in solution pH. This finding aligns closely with the existing literature [31], confirming the validity of the results obtained.

3.1.2. MEA 1 M and AMP 4 M

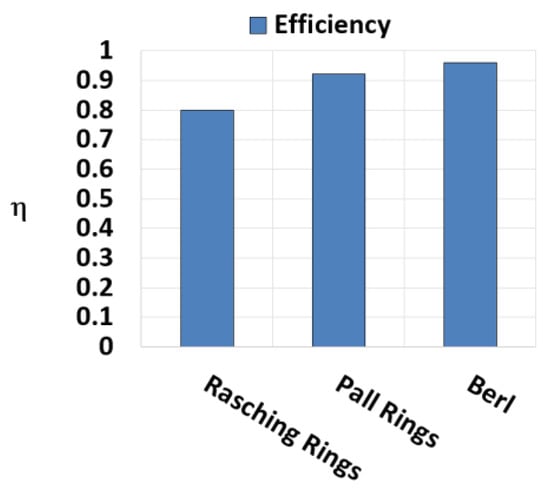

In this section, the results regarding the amine blend with MEA and AMP are reported. Firstly, the comparison between different packings with the same L/G are reported to determine the best option to use for the tests. From Figure 11, it is shown that the best packing option to obtain the highest CO2 capture efficiency is the Berl saddles.

Figure 11.

Efficiency trend in function of packing type during a test with MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M L/G = 3.9.

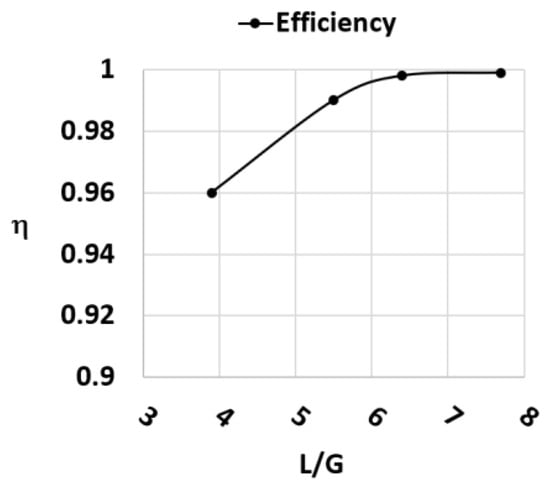

After these tests, other tests regarding the increase in absorption efficiency were conducted on the Berl saddles setup. In this case, the L/G was varied to see the increase in η. These results are reported in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Efficiency trend in function of L/G ratio during a test with MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M L/G = 3.9 Berl saddles.

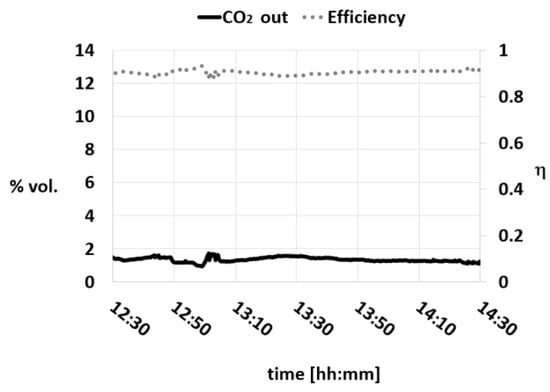

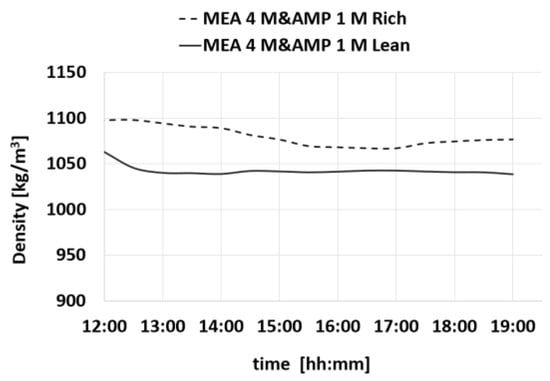

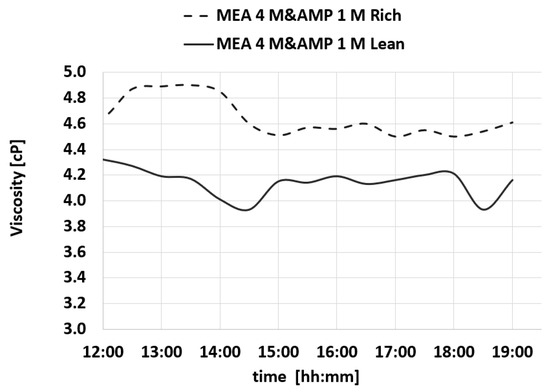

Lastly, an evaluation of the CO2 concentration trend and an analysis of the viscosity and the density of the lean absorbent were conducted using L/G = 3.9 and Berl saddles as the packing; the results obtained are reported in Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Figure 13.

CO2 concentration trend and efficiency during a test with MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M L/G = 3.9 Berl saddles.

Figure 14.

Density trend for MEA 4 M- and AMP 1 M-rich and MEA 4 M- and AMP 1 M-lean during a test.

Figure 15.

Viscosity trend for MEA 4 M- and AMP 1 M-rich and MEA 4 M- and AMP 1 M-lean during a test.

Table 3 summarizes the results obtained in the tests made with the MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M to evaluate the key physical properties such as the density, the viscosity, and the pH.

Table 3.

Experimental test results MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M lean and rich properties.

According to the experimental data, it is evident that examining three key parameters provides important information on amine loading.

These parameters serve as indicators that offer valuable information on the absorption capacity of the amine solution and its cycling performance. Furthermore, by establishing a correlation among these parameters, it becomes possible to estimate the cycling capacity of the absorbent more effectively. This approach not only enhances the understanding of amine solutions behavior during CO2 absorption but also offers a practical tool for optimizing the performance of the absorbent. This critical analysis underscores the importance of considering multiple parameters and their interplay in assessing and improving the efficiency of CO2 capture technologies.

Upon analyzing the results, it becomes clear that the properties of the amine solution exhibit consistent behavior throughout the conducted tests indicating that the amine solution retains its capability to effectively cycle and absorb CO2 over an extended period of time. The preservation of properties without significant fluctuations suggests that the amine solution effectively undergoes absorption and desorption cycles without retaining excessive CO2. In the tests that have been performed, it is notable that there is a lack of noticeable increases in density, viscosity, or other parameters. This can further support the efficient cycling ability of the amine solution, but to be sure of this characteristic, more tests should be performed to assess the stability of this amine solution.

4. Steady-State Simulation Model

A detailed simulation model of the CO2 capture pilot plant, comprising both the absorption and regeneration sections, has been developed using the Aspen Plus simulation environment. The implementation of process simulation serves as a powerful tool for predicting plant performance and assessing operating behavior under various conditions, thereby providing results that would otherwise require extensive laboratory or pilot-scale experimentation. Such simulations not only support the design and optimization of the plant but also facilitate the planning and interpretation of experimental campaigns.

In addition, the developed model offers valuable insights for guiding future process improvements and enhancing operational efficiency. To ensure the model’s reliability and predictive accuracy, both the absorption and stripping sections were validated through a detailed comparison between simulated results and experimental data collected from the pilot plant. This validation confirmed the model’s ability to correctly represent the real process behavior and its suitability for use as a design and optimization tool in subsequent studies.

4.1. Model Assumption

Thermodynamics, kinetics, and mass transfer strongly influence the CO2 absorption process with alkanolamine solutions [32], leading to a removal efficiency lower than that calculated at equilibrium. Therefore, using an equilibrium model for the absorption column and the stripper column would not lead to real results.

To develop a model that accurately represents the CO2 capture and regeneration process using amine-based solvents, a rate-based absorption model (Rate-Sep) within the Aspen Plus process simulation environment was employed for each of the absorption and stripping columns.

The Rate-Sep model accounts for the actual rates of mass and heat transfer together with the kinetic limitations of the chemical reactions involved. It performs calculations under non-equilibrium conditions based on the mass transfer rates occurring within the column packing. To enable accurate simulation, detailed information on packing characteristics, such as geometry and mass transfer properties, along with the preliminary column design, must be specified.

In the Rate-Sep framework, both the absorber and stripper are split into multiple theoretical stages along the column height. For each stage, material, energy, and momentum balances are performed and then integrated throughout the entire column. Furthermore, for each stage, the model evaluates the mass and heat transfer resistances in the gaseous and liquid phases. To enhance numerical accuracy for film reactions, the interfacial region among the liquid and gas phases at each stage is discretized into several segments [33].

The two-film theory, originally proposed by Lewis and Whitman in 1924, is employed to describe CO2 absorption and to quantify mass transfer across the gas–liquid interface. According to this theory, all resistance to mass and heat transfer is assumed to be confined to two thin films adjacent to the interface [34].

In this work, the Rad-Frac model utilizes a flow representation based on the VPlug/VPlugP/LPlug flow scheme to evaluate the bulk phase conditions. Within this model, each segment assumes that the bulk properties represent the mean conditions for one phase and the outlet conditions for the other [35].

The thermodynamic and transport properties of the MEA–H2O–CO2 system were modeled using the Electrolyte Non-Random Two-Liquid (NRTL) framework, as developed in [17,36]. This activity coefficient model accounts for non-ideal molecular and ionic interactions in the liquid phase [37]. The Redlich–Kwong equation of state was used to calculate vapor-phase fugacity coefficients, and a γ/Φ approach was adopted to represent vapor–liquid equilibrium.

Finally, the available packing surface area per unit volume of packing was expressed as a function of both the liquid properties and the geometric characteristics of the packing. Several empirical correlations have been developed to evaluate the wetted surface area, depending on the specific packing type employed. In this work a random packing approach is used to estimate the wetted surface area, and the correlations for metallic Pall Rings is taken from Onda et al. [38].

Moreover, when it comes to the usage of random packing, Zang et al. [34] showed that the correlation proposed by Onda et al. undervalued the wetted surface area. Therefore, the Interfacial Area Factor in the simulator was adjusted to 1.2 to correct this parameter’s evaluation.

The column model has been integrated into the Aspen Plus Rad-Frac column model using the rate-based calculation method. The study uses the framework and absorber parameters to model the MEA system given by AspenTech.

Table 4 summarizes the input data (packing type and dimension, column diameter, and total packed height) and the correlation parameters applied to model the absorption and desorption columns.

Table 4.

Model assumption and input data.

In this work, the reaction scheme implemented in the model is composed of a set of equilibrium reactions and reversible kinetic reactions. Considering the set of reactions describing the MEA-CO2-H2O chemistry shown previously, all Reactions (1)–(3) are assumed to be in chemical equilibrium and are instantaneous.

Conversely, the formation of bicarbonate ion Reaction (4) and the formation of carbamate Reaction (5) have kinetic limitations and are assumed to be reversible reactions.

The equilibrium expressions and the chemical equilibrium constant are taken from the literature.

For reactions with kinetic limitation, the reaction rates are expressed using a power law formula, and the relative kinetic values are derived from data published in the literature [41]. Reaction kinetics for carbamate formation are taken from Hikita et al. [27], while those for bicarbonate formation are from Pinsent et al. [42]. Reactions (12) and (13) represent the forward and reverse reactions for carbamate formation, whereas Reactions (14) and (15) correspond to the forward and reverse reactions for bicarbonate formation.

A reaction set was created to describe the reactions of the binary mixture of amine MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M. In this set, all reactions are considered to be in chemical equilibrium, except those of CO2 with OH− (14) and (15) and CO2 with MEA (12) and AMP (16).

The reaction kinetic constants for Reactions (12)–(15) are the same as those implemented in the MEA 5 M model.

For the AMP-CO2 system, a second order expression for the reaction rate of Reactions (16) and (17) is used, which is a simplification of the expression in Jamal et al. [43].

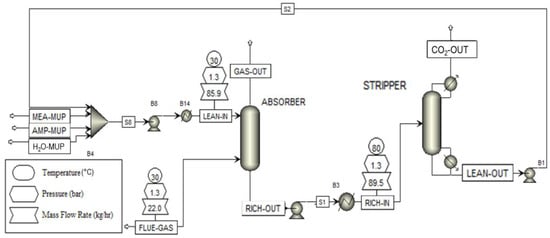

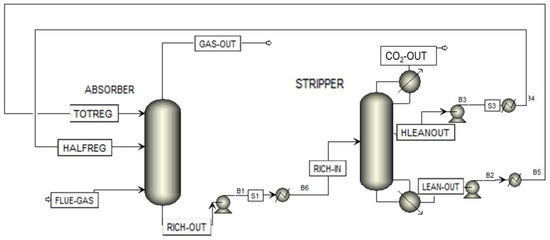

The schematic presented in Figure 16 illustrates the modeled plant configuration, which consists of an absorption column for CO2 removal. The exhaust gas (FLUEGAS) enters the bottom of the absorption column and flows upward in countercurrent contact with the aqueous lean MEA solution (LEAN-IN). The purified gas stream (GASOUT) exits from the top of the column and is directed to the vent, while the CO2-rich solvent is withdrawn from the bottom.

Figure 16.

Aspen plant model.

The CO2-rich solution is subsequently heated and introduced into the regeneration (stripping) column, where the absorbed CO2 is released. The regenerated lean solvent (LEAN-OUT), leaving the stripper, is cooled before being recirculated to the top of the absorber column to complete the loop. The purified CO2 gas stream exits from the top of the stripper after being cooled in a heat exchanger to approximately 101 °C.

4.2. Model Result Validation

The model proposed in this paper was validated using experimental data. Table 5 summarizes the main assumptions, operating parameters, performance, and model results for MEA 5 M and for the MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M blend.

Table 5.

Pilot plant model validation MEA 5 M and MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M.

The absorber and stripper model showed the ability to effectively simulate the pilot plant. The delta CO2 loading gives an indication of the absorption capacity of the solvent, as shown in the table, where the delta value between MEA-lean and MEA-rich in both model and experimental results gives similar values. The reboiler duty obtained for the MEA 5 M simulation was a duty of 2.49 , whereas for the MEA 4 M + AMP 1 M, the duty obtained by the simulation was 1.92 , so the addition of the AMP had a good impact in terms of the regeneration duty.

Table 6 shows the comparison between the physical properties of the liquid streams MEA-lean and MEA-rich, showing a good agreement between the values obtained from model and experimental results.

Table 6.

Comparison of solvent physical properties between pilot plant and model results for MEA 5 M and for the MEA 4 M and AMP 1 M blend.

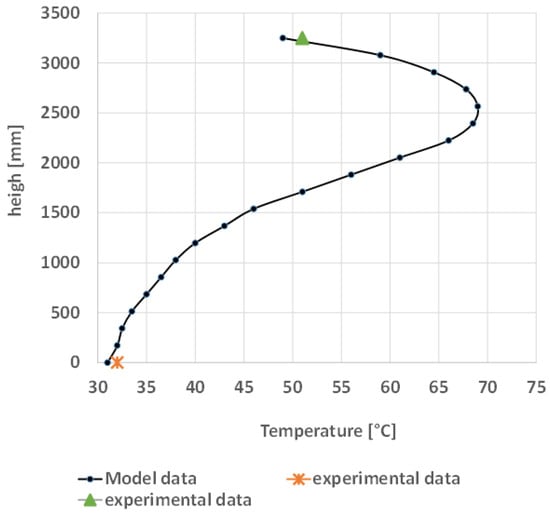

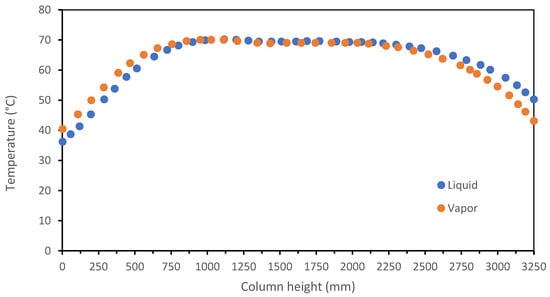

Figure 17 shows the liquid temperature profiles of the absorption columns in the case of CO2 absorption with MEA 5 M, with the bulge located near the bottom of the column. The trend shows good agreement with literature. In fact, as broadly discussed in the work of Kvamsdal & Rochelle [41], the typical bulge in the temperature profiles occurs in the column bottom.

Figure 17.

Absorber liquid temperature profile.

This profile occurs because the CO2-rich gas is fed to the bottom in countercurrent with the solvents. The CO2 rising through the packed bed is absorbed in the solvent; being an exothermic process, the temperature of the descending solvent increases and the water vaporizes. Going on to the top of the column, the cooler solvent descending causes the rising gas to cool as the water condenses.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

In this section, a sensitivity analysis is carried out to investigate how key operational parameters influence the overall efficiency of the CO2 capture process, with particular attention to their effect on the regeneration duty. These analyses serve a dual purpose: they validate the reliability of the developed model and provide useful insights for optimizing process performance.

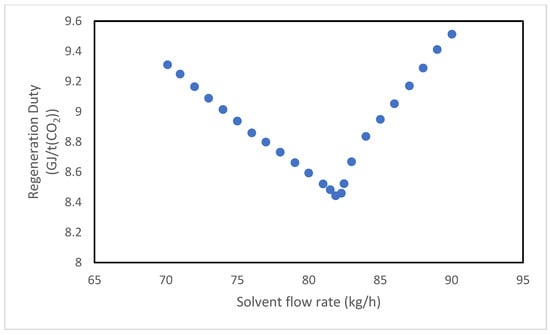

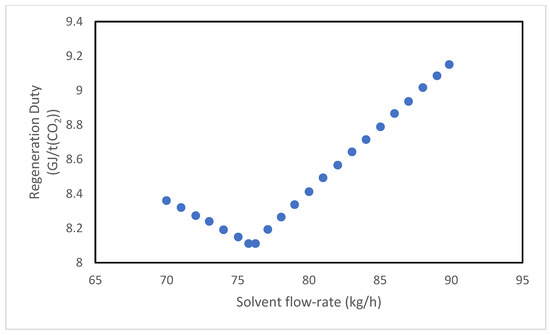

The study is conducted for both solvents, monoethanolamine (MEA) and the MEA + AMP blend, by varying one parameter at a time while maintaining all other variables at the pilot plant’s standard operating conditions. Specifically, the analysis examines the effect of three main parameters: the absorbent mass flow rate, the amine mass fraction, and the pressure at the top of the stripping column. Figure 18 and Figure 19 illustrate the system’s response to variations in the absorbent flow rate. In both cases, the regeneration duty displays an upward-facing concavity, indicating the existence of a minimum point. This suggests that within a certain range of solvent flow rates, an increase in regeneration duty, associated with a greater volume of liquid processed in the system is counterbalanced by a proportionally higher CO2 absorption, resulting in an overall decrease in specific energy consumption. It is significant to note that the reboiler duty depends not only on the treated flow rate but also on the boiling temperature of the solution, which rises with CO2 loading.

Figure 18.

Effect of solvent flow rate on the regeneration duty of the MEA solvent.

Figure 19.

Effect of solvent flow rate on the regeneration duty of the MEA + AMP solvent.

Conversely, when the solvent flow rate increases within a specific range, the CO2 loading decreases because the moles of amine increase more rapidly than those of absorbed CO2, thereby reducing the regeneration duty and mitigating the effect of the increased liquid throughput.

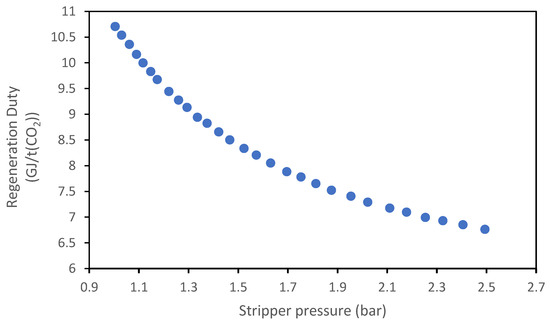

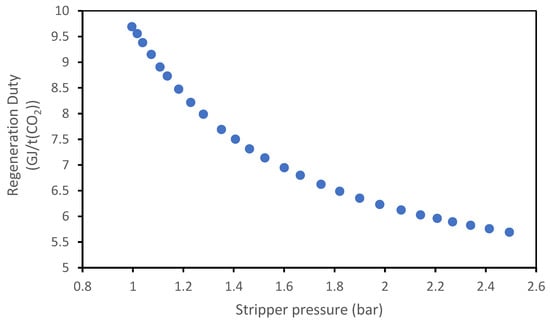

Figure 20 and Figure 21 show the variation in reboiler duty as a function of the pressure at the top of the stripper; for both absorbents, an increase in the stripper pressure results in a decrease in the regeneration duty; this effect is due to the strong dependence of the CO2 partial pressure to the variation in the boiling temperature: an increase in the total pressure will increase the boiling temperature, which will cause a greater increase in the CO2 partial pressure compared to the total pressure. Therefore, CO2 desorption will be easier.

Figure 20.

Effect of the stripper pressure on the regeneration duty of the MEA solvent.

Figure 21.

Effect of the stripper pressure on the regeneration duty of the MEA + AMP solvent.

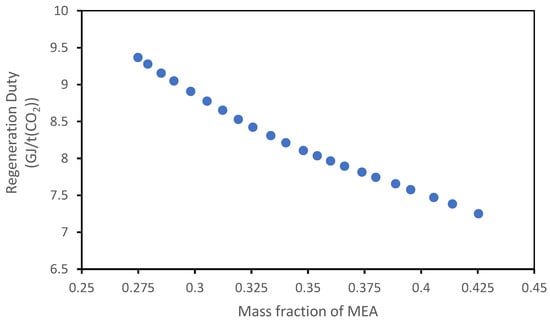

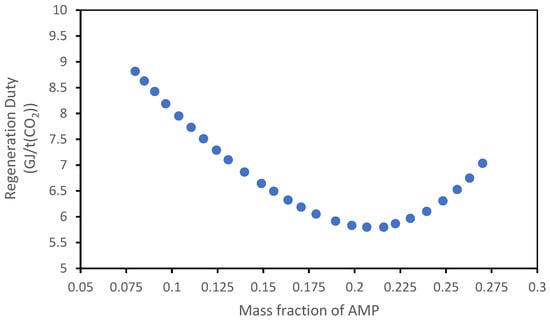

Figure 22 and Figure 23 show the results of the analysis regarding the variation in the concentration of the solvents.

Figure 22.

Influence of mass fraction of MEA on the regeneration duty of the MEA solvent.

Figure 23.

Influence of mass fraction of AMP on the regeneration duty of the MEA + AMP solvent.

For the MEA solvent, the quantity of amine was varied around the value of 30% mass fraction; from the graph, it can be deduced that an increase in the amine’s concentration leads to a decrease in the regeneration duty; this trend is predictable because an absorbent more concentrated can absorb the same quantity of CO2 with a lower flow rate.

It is important to specify that these two analyses, which seem to suggest a straight increase in the stripper pressure and the MEA concentration to optimize the process, do not consider other phenomena like the absorbent degradation at higher temperature (related to the high stripper pressure), the pump cost caused by the higher stripper pressure, and the higher corrosivity caused by the more concentrated absorbent; for these reasons, the maximum MEA concentration used is around 30%, and the stripper pressure is generally higher than 2.5 barg.

In the MEA + AMP solvent case, the total mass fraction of the amine is fixed at 30%, but the fraction of AMP is gradually increased relative to MEA, starting from the value of the pilot plant (22% of MEA/8% of AMP). From Figure 22, an optimum of concentration of AMP can be observed, and this is around 21% of AMP/9% of MEA.

This tendency is in agreement with the theory behind the mixing of a primary amine (with a rapid kinetic) such as MEA with a sterically hindered amine such as AMP: the mix of these two amines has the aim to maintain the absorption kinetic really fast because of the presence of MEA and, in the meantime, to increase the maximum loading obtained in the absorption phase (promoting the thermodynamic equilibrium) thanks to AMP; however, an excessive increase in the AMP concentration, while promoting the equilibrium conditions, results in too slow kinetics compared to the residence times that occur with the designed solvent flow rate and the column size.

4.4. New Plant Evaluation for Energy Efficiency Improvement

A new plant configuration is implemented with the aim of improving the process energy efficiency in terms of reboiler duty decrease. Therefore, some technical improvements that require additional equipment may be included in the basic configuration.

The first process improvement is the lean vapor compression (LVC), which consists of the partial compression of the regenerated solvent coming from the stripper, to partially electrify the process, reducing the heat duty of the reboiler at the bottom of the stripper; the regenerated solvent undergoes an adiabatic flash in the low-pressure evaporator and is then compressed and inserted into the stripper as a stripping vapor to reduce the reboiler duty (it is possible to add water before the compression to regulate the temperature of the compressed vapor).

A second improvement consists of the use of a pump around the absorption column with inter-refrigeration. A liquid stream is extracted and cooled before flowing back to the same stage; in this way, the medium absorption temperature decreases and the efficiency improves, since CO2 absorption in the MEA solution is an exothermic reaction.

Finally, the last process improvement consists of a “split-flow” configuration. Part of the solvent flow rate partially regenerated is drawn from an intermediate stage of the stripping column (reducing the reboiler loading) and introduced into an intermediate stage of the absorption column. This configuration enhances overall absorption in two ways. In the lower section of the absorber, the partially regenerated solvent encounters a gas stream with a higher CO2 partial pressure, promoting strong absorption. In the upper half, absorption remains efficient because, although the CO2 partial pressure is lower, the gas encounters solvent that has been fully regenerated. Moreover, it is possible to reduce the medium absorption temperature by cooling down the partially regenerated solvent [44].

As an example, a split-flow configuration of CO2 absorption, shown in Figure 24, was simulated with an aqueous solution of MEA 5 M in the same operative condition of the pilot plant.

Figure 24.

Split-flow process scheme implemented on Aspen.

Table 7 compares the major parameters between the basic scheme and the split-flow scheme; the results show that the solvent regeneration duty is reduced by about 10%, although the CO2 removal efficiency remains almost constant.

Table 7.

Performance comparison between basic process scheme and split-flow scheme.

Moreover, as can be seen in the Figure 25, the effect of recirculation of a partially regenerated amine stream in the absorption column upper-half results in greater uniformity of the temperature profile within the column, which indicates a higher absorption efficiency. In fact, in the split-flow case, although a solvent with a significantly higher loading is introduced (0.3 versus 0.22 in the basic scheme), the removal efficiency remains almost unchanged (it is reduced by only 0.7 percent).

Figure 25.

Temperature profile in the split-flow absorber.

In the split-flow configuration, a drastic reduction in MEA consumption in the make-up flow rate and good duty savings may be obtained. The operating costs of the split-flow scheme can be evaluated and compared with the base case (Table 8).

Table 8.

Economic evaluation of operating costs in the split-flow scheme.

Equations (18) and (19) describe the methodology to calculate the feedstock specific cost and the regeneration duty specific cost in the two different schemes.

5. Basic Economic Evaluation

In this section, the results obtained from the tests are compared to determine the most efficient solvent for the process.

Even if the experimental data for the AMP 3 M solvent were not available, the process was simulated also for the case with this solvent to evaluate the performance and confront the results with the MEA and MEA + AMP solvents, and to highlight the improvement caused by the switch from a single solvent to a mixed solvent. Table 9 shows the principal parameter to determine the performance of the absorption process.

Table 9.

Comparison of performance parameters for different solvents used.

From the table, it can be seen that the AMP solvent is slightly more efficient in terms of CO2 removal than the MEA, but it has a higher regeneration duty that does not justify its use.

The MEA + AMP solvent, on the other hand, has a greater removal efficiency than the other two solvents and also greater efficiency in terms of regeneration duty per ton of removed CO2.

To complete the comparison between the three solvents, a comparative economic analysis is reported, aiming to highlight the costs relative deviation between the single amines and the blend.

Since the use of the three absorbents was performed on the same plant, in fact, it is assumed that the fixed costs (CAPEX) are almost identical in the three cases; similarly, it can be assumed for the pumping costs of the different streams circulating in the plant, since, as evidenced by the experimental data and simulation results, the differences in density and viscosity between the various solvents used are marginal, so it is assumed that these costs, in the three cases, are also very similar.

On the other hand, the major differences arise in terms of the flow rate of the make-up streams (hence raw material consumption) and energy required for regeneration, so these cost items will be evaluated in order to make an economic analysis to perform a relative comparison that gives a reasonable indication of the relationship of the operating costs of the same plant operating with the three different solvents.

The following Table 10 shows the data, extrapolated from the tables in the previous paragraphs, on raw material and duty consumption for the three cases studied.

Table 10.

Raw material and energy consumption using MEA, MEA + AMP, AMP.

Regarding the cost of the amines, the prices of MEA and AMP produced by different suppliers (Sigma Aldrich (Guidonia Montecelio, Italy)) [45,46], Thermo Fisher (Monza, Italy) [47,48], Shandong Pulisi Chemical Co. (Zibo City, Shandong Province, China) [49], Fradox Global Co. (Taoyuan City, China) [50]) are, on average, about 1.46 EUR/kg and 3.25 EUR/kg, respectively; although these prices may indeed not reflect the industrial cost of these amines, it is assumed that the ratio of the price of MEA to that of AMP remains almost constant and about 2.2 (the objective of this economic analysis is an estimate in relative, not absolute, terms). The comparison of operating costs of the three solvents MEA, MEA + AMP and AMP are outlined in Table 11

Table 11.

Operating cost comparison of the three solvents MEA, MEA + AMP, and AMP.

Regarding the cost of regeneration energy, since the boiling temperatures of the regenerated solvents are in any case between 111 °C (MEA 5 M) and 120 °C (MEA 4 M + AMP 1 M), medium-pressure steam will be used as a reference, the cost of which can be estimated (in case no electricity cogeneration is operated that creates credit) at 3.97 EUR/GJ [51].

In conclusion, the solvent consisting of MEA + AMP turns out to be the most effective in terms of CO2 removal, but not the most efficient in terms of cost removal, due to the high cost of AMP compared to that of MEA. This consideration, however, is valid for the pilot plant operating conditions (used as the basis for the calculations), which may not be the optimal ones with respect to amine loss in the streams leaving the process.

6. Conclusions

This study presented the experimental testing and modeling validation of a pilot-scale CO2 capture system using amine-based solvents, integrated within a gasification platform. The pilot plant, designed to process up to 40 kg CO2 per day, was tested under various operating conditions to assess the performance of monoethanolamine (MEA), 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP), and MEA + AMP solvent mixtures.

Experimental results demonstrated that the MEA + AMP blend achieved the highest CO2 removal efficiency (≈95%) and the lowest regeneration duty (≈7.2 GJ t−1 CO2), confirming the synergistic behavior of primary and sterically hindered amines in enhancing absorption kinetics and reducing energy demand. The physical characterization of the solvents (density, viscosity, pH, and CO2 loading) showed stable and reproducible trends, indicating reliable solvent cycling and operability.

The Aspen Plus rate-based model accurately reproduced the experimental results, validating its capability to predict CO2 loading, solvent properties, and temperature profiles in both absorber and stripper columns. Simulation-based sensitivity analyses identified optimal operating parameters and demonstrated that process modifications, such as split-flow configurations, could further reduce regeneration energy requirements by about 10% without compromising capture performance.

The knowledge and results obtained will support the design of future experiments and components, enabling testing at scales comparable to industrial practice. Following the initial experimental sessions, several activities are currently underway, with additional developments planned.

Future experiments will focus on evaluating new blended amine solutions, such as MDEA + PZ, as well as novel solvents like ionic liquids. Additional efforts will be devoted to optimizing operating conditions and heat transfer, and to implementing new columns equipped with thermocouples along the bed height, featuring intermediate material recirculation capabilities. Furthermore, the feasibility of retrofitting the system to operate the adsorption section at pressures up to 10 bar will be investigated.

Overall, the integration of experimental data and process modeling provides a robust basis for optimizing solvent-based CO2 capture systems at the pilot scale. These findings support the design of more energy-efficient and scalable post-combustion capture technologies aligned with EU decarbonization objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., P.D., G.C. and G.V.; Methodology, C.B., M.M., P.D. and G.C.; Software, M.M.; Validation, C.B., M.M., P.D., G.C. and G.C.; Formal analysis, L.C.; Investigation, E.M. and L.C.; Resources, M.M. and E.M.; Data curation, C.B., M.M., G.C., L.C. and G.C.; Writing—original draft, C.B., M.M. and G.C.; Writing—review & editing, C.B.; Visualization, C.B., P.D., G.C., E.M., L.C. and G.C.; Supervision, C.B., P.D., G.C. and E.M.; Project administration, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of Sustainable Economic Development Unique Project Code I12F17000070001.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, as the data are part of an ongoing study and further analyses are planned.

Acknowledgments

This work was developed into the RdS Research Program on Electrical Grid coordinated by ENEA 2015–2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations and Nomenclature

The following abbreviations/nomenclature are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviations | |

| AMP | 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol |

| CCS | Carbon Capture Storage |

| ESP | Electrostatic Precipitator |

| FOAK | First Of A Kind |

| GHG | Green House Gases |

| LPG | Liquefied Petroleum Gas |

| MEA | Monoethanolamine |

| PSA | Pressure Swing Adsorption |

| R&I | Research and Innovation |

| Nomenclature | |

| α | CO2 amine loading |

| ν | Viscosity |

| ρ | Density |

References

- The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- The Net-Zero Industry Act: Accelerating the Transition to Climate Neutrality. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/sustainability/net-zero-industry-act_en (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Løge, I.A.; Demir, C.; Vinjarapu, S.H.B.; Neerup, R.; Jensen, E.H.; Jørsboe, J.K.; Dimitriadi, M.; Halilov, H.; Frøstrup, C.F.; Gyorbiro, I.; et al. Pilot-scale CO2 capture in a cement plant with CESAR1: Comparative analysis of specific reboiler duty across advanced process configurations. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, J.; Agon, N.; Louwagie, D.; Gutiérrez-Sanchez, O.; Huizinga, A.; Gravesteijn, P.; Kruijne, M.; Skylogianni, E.; van Os, P.; Garcia Moretz-Sohn Monteiro, J. CESAR1 Carbon Capture Pilot Campaigns at an Industrial Metal Recycling Site and Analysis of Solvent Degradation Behavior. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 5548–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post Combustion Carbon Capture from Coal Fired Plants-Solvent Scrubbing Technical Study. 2007. Available online: http://www.ieagreen.org.uk (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Gautam, A.; Mondal, M.K. Review of recent trends and various techniques for CO2 capture: Special emphasis on biphasic amine solvents. Fuel 2023, 334, 126616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, W.; Bruggink, S.; Beyad, Y.; Luo, W.; Melián-Cabrera, I.; Puxty, G.; Feron, P. CO2 absorption into aqueous amine blended solutions containing monoethanolamine (MEA), N,N-dimethylethanolamine (DMEA), N,N-diethylethanolamine (DEEA) and 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP) for post-combustion capture processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 126, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, U.H.; Kazmi, W.W.; Muhammad, H.A.; Min, G.H.; Nam, S.C.; Baek, I.H. Practical and inexpensive acid-activated montmorillonite catalysts for energy-efficient CO2 capture. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 6328–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, U.H.; Sivanesan, D.; Nam, S.; Park, S.Y.; Baek, I.H. Efficient Ag2O–Ag2CO3 Catalytic Cycle and Its Role in Minimizing the Energy Requirement of Amine Solvent Regeneration for CO2 Capture. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 10234–10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, X.; Yang, J.; Gao, H.; Huang, Y.; Luo, X.; Liang, Z.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Reducing Energy Penalty of CO2 Capture Using Fe Promoted SO42−/ZrO2/MCM-41 Catalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6094–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifzadeh, M.; Triulzi, G.; Magee, C.L. Quantification of technological progress in greenhouse gas (GHG) capture and mitigation using patent data. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2789–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, C.; Ye, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Two-stage interaction performance of CO2 absorption into biphasic solvents: Mechanism analysis, quantum calculation and energy consumption. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, R.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S. Regulating Phase Separation Behavior of a DEEA–TETA Biphasic Solvent Using Sulfolane for Energy-Saving CO2 Capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12873–12881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynal, L.; Bouillon, P.-A.; Gomez, A.; Broutin, P. From MEA to demixing solvents and future steps, a roadmap for lowering the cost of post-combustion carbon capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.W.; Na, J.; Ahn, B.S.; Lee, S.D.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, H.; Lee, U. An experimental based optimization of a novel water lean amine solvent for post combustion CO2 capture process. Appl. Energy 2019, 248, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, C.; Shi, X.; Li, H.; Shen, S. Nonaqueous amine-based absorbents for energy efficient CO2 capture. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, I.I.I.; Pereira, L.M.C.; AlHajaj, A.; Vega, L.F. Performance of non-aqueous amine hybrid solvents mixtures for CO2 capture: A study using a molecular-based model. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 35, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Li, J.; Ren, B.; Lu, X. Development of High-Capacity and Water-Lean CO2 Absorbents by a Concise Molecular Design Strategy through Viscosity Control. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 5164–5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, W.M. Introduction to Carbon Dioxide Capture by Gas–Liquid Absorption in Nature, Industry, and Perspectives for the Energy Sector and Beyond; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, T. Progress of CCUS technology in the iron and steel industry and the suggestion of the integrated application schemes for China. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghel, B.; Janati, S.; Wongwises, S.; Shadloo, M.S. Review on CO2 capture by blended amine solutions. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 119, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Luberti, M.; Liu, Z.; Brandani, S. Process configuration studies of the amine capture process for coal-fired power plants. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 16, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Straelen, J.; Geuzebroek, F. The thermodynamic minimum regeneration energy required for post-combustion CO2 capture. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1500–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhwashu, M.I.; Moropeng, M.L.; Agboola, O.; Kolesnikov, A.; Mavhungu, A. The application of the numeral method of lines on carbon dioxide captures process: Modelling and simulation. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2019, 31, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeddu, C.; Errico, M.; Baratti, R. CO2 Capture by Reactive Absorption-Stripping: Modelling, Analysis and Design; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikita, H.; Asai, S.; Ishikawa, H.; Honda, M. The kinetics of reactions of carbon dioxide with monoethanolamine, diethanolamine and triethanolamine by a rapid mixing method. Chem. Eng. J. 1977, 13, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errico, M.; Madeddu, C.; Pinna, D.; Baratti, R. Model calibration for the carbon dioxide-amine absorption system. Appl. Energy 2016, 183, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, E.; Zhang, Y.D.; Liu, D.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Parametric Process Design and Economic Analysis of Post-Combustion CO2 Capture and Compression for Coal- and Natural Gas-Fired Power Plants. Energies 2020, 13, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiana, P.; Bassano, C.; Calì, G.; Miraglia, P.; Maggio, E. CO2 capture and amine solvent regeneration in Sotacarbo pilot plant. Fuel 2017, 207, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Guo, B.; Zhou, Z.; Jing, G. Mechanisms of CO2 Capture into Monoethanolamine Solution with Different CO2 Loading during the Absorption/Desorption Processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 10728–10735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, J.M.; Van Wagener, D.; Rochelle, G.T. Modeling CO2 capture with aqueous monoethanolamine. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Wardhaugh, L.; Feron, P.; Chen, C. Development of a rate-based model for CO2 absorption using aqueous NH3 in a packed column. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 17, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.-C.; Plaza, J.M.; Dugas, R.; Rochelle, G.T. Rate-Based Process Modeling Study of CO2 Capture with Aqueous Monoethanolamine Solution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 9233–9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimiliano, M.; Madeddu, C.; Baratti, R. 4. Reactive absorption of carbon dioxide: Modeling insights. In Process Intensification; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 79–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, L.; De Weireld, G.; Thomas, D. Dynamic Simulations of an Amine-based Absorption-regeneration CO2 Capture Process Applied to Lime Plant Flue Gases. In Proceedings of the 17th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference (GHGT-17), Calgary, AB, Canada, 20–24 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Kim, J.; Jung, J.; Lee, C.S.; Han, C. Modeling and Simulation of CO2 Capture Process for Coalbased Power Plant Using Amine Solvent in South Korea. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onda, K.; Takeuchi, H.; Okumoto, Y. Mass transfer coefficients between gas and liquid phases in packed columns. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1968, 1, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, T.H.; Colburn, A.P. Mass transfer (absorption) coefficients prediction from data on heat transfer and fluid friction. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1934, 26, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichlmair, J.; Bravo, J.L.; Fair, J.R. General model for prediction of pressure drop and capacity of countercurrent gas/liquid packed columns. Gas Sep. Purif. 1989, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvamsdal, H.M.; Rochelle, G.T. Effects of the Temperature Bulge in CO2 Absorption from Flue Gas by Aqueous Monoethanolamine. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsent, B.R.W.; Pearson, L.; Roughton, F.J.W. The kinetics of combination of carbon dioxide with hydroxide ions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1956, 52, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Meisen, A.; Lim, C.J. Kinetics of carbon dioxide absorption and desorption in aqueous alkanolamine solutions using a novel hemispherical contactor, I. Experimental apparatus and mathematical modeling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2006, 61, 6571–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Lee, B.; Kim, S.Y. The Split Flow Process of CO2 Capture with Aqueous Ammonia Using the eNRTL Model. Processes 2022, 10, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigma Aldrich. Merck, Ethanolamine. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IT/it/product/aldrich/411000 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Sigma Aldrich. Merck, 2-Amino-2-methyl-1-propanol. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IT/it/substance/2amino2methyl1propanol8914124685 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Fisher Scientific. 2-Amino-2-methyl-1-propanol, 99%, Thermo ScientificTM. Available online: https://www.fishersci.ca/shop/products/2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol-99-thermo-scientific/p-3735477 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Fisher Scientific. Ethanolamine, ACS, 99+%, Thermo ScientificTM. Available online: https://www.fishersci.ca/shop/products/ethanolamine-acs-99-thermo-scientific/p-7050237#?keyword= (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Shandong Pulisi Vhemical Co. Available online: https://italian.alibaba.com/p-detail/Top-1600412268570.html?spm=a2700.galleryofferlist.topad_classic.d_title.3d9c7b57uC8isT (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Fradox Global Co. Available online: https://italian.alibaba.com/p-detail/2-Amino-2-Methyl-1-Propanol-10000004418610.html?spm=a2700.galleryofferlist.normal_offer.d_title.2cd7d554MudKKt (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Turton, R.; Bailie, R.C.; Whiting, W.B.; Shaeiwitz, J.A. Analysis; Synthesis, and Design of Chemical Processes, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.